Abstract

There is a growing need to understand from the patient’s perspective the experience of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and the factors contributing to its severity; this has been endorsed by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Accordingly, we conducted focus groups to address this issue. A total of 32 patients with mostly moderate to severe IBS were recruited through advertising and were allocated into three focus groups based on predominant stool pattern. The focus groups were held using standard methodology to obtain a general assessment of the symptoms experienced with IBS, its impact, and of factors associated with self-perceived severity. Patients described IBS not only as symptoms (predominantly abdominal pain) but mainly as it affects daily function, thoughts, feelings and behaviors. Common responses included uncertainty and unpredictability with loss of freedom, spontaneity and social contacts, as well as feelings of fearfulness, shame, and embarrassment. This could lead to behavioral responses including avoidance of activities and many adaptations in routine in an effort for patients to gain control. A predominant theme was a sense of stigma experienced because of a lack of understanding by family, friends and physicians of the effects of IBS on the individual, or the legitimacy of the individual’s emotions and adaptation behaviors experienced. This was a barrier to normal functioning that could be ameliorated through identifying with others who could understand this situation. Severity was linked to health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and was influenced by the intensity of abdominal pain and other symptoms, interference with and restrictions relating to eating, work, and social activities, and of the unpredictability of the condition. This study confirms the heterogeneous and multi-component nature of IBS. These qualitative data can be used in developing health status and severity instruments for larger-scale studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There is a growing need to understand health status in medical disorders from the patient’s perspective. This has been evident over the last 10–15 years with the development of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) instruments and their application in outcomes in research and clinical trials. However, an understudied area of health status assessment relates to illness severity. When studying structural disorders like inflammatory bowel or acid peptic disease, severity is usually attributed to morphological abnormalities, which is easier to measure [1]. With functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), there are no objective measures of disease, so severity must be based on the patient’s experience.

IBS severity is not well characterized yet has important clinical consequences. It affects patient decisions to take medication, to stay out of work, or to seek health care. For the clinician, IBS severity influences decisions related to ordering diagnostic studies and prescribing treatments. For the clinical investigator, it correlates with psychosocial and behavioral outcomes and needs to be quantified in treatment trials, particularly for medications with potential risk. Yet there exists little knowledge of how to define or understand the factors contributing to severity from the patient’s perspective [2].

For these reasons, the Rome Foundation (www.theromefoundation.org) and the International Foundation for Functional GI Disorders (www.iffgd.org) collaborated on a project to use standardized focus group assessment [3] to understand the patient’s experience of IBS and the factors contributing to its severity.

Methods

Initial Recruitment

Recruitment was done by IFFGD using four methods: (a) randomly identifying 335 contacts in Wisconsin and nearby states from their mailing list and sending them a letter with an invitation to participate, (b) e-mailing five gastroenterologists known to IFFGD in the Milwaukee area an advertisement to post in waiting rooms to (c) placing electronic advertisements on the IFFGD Web sites, and (d) printing an ad in the Milwaukee Journal–Sentinel. A total of 44 potential participants responded to the recruitment and contacted IFFGD.

Screening Assessment

The screening process verified the diagnosis of IBS and obtained clinical features relating to stool type and severity. The 44 potential participants were mailed along with a self-addressed stamped return envelope, a 28-item self-report demographic, a medical information questionnaire, and two standardized severity measures: the functional bowel disorder severity index (FBDSI) [4] and the IBS severity scale (IBS-SS) [5], a brief health status measure, the BEST questionnaire [6], and a few questions about the willingness to take risks in using medications. Thirty-three individuals (75% of those mailed the survey) returned their questionnaires to IFFGD and were forwarded to the UNC Biometry Core for group assignment. Of the 11 not responding, ten were contacted through Web advertising and almost half (n = 5) were from geographical areas outside the Wisconsin/Illinois area, suggesting that distance was a contributing factor to non-response.

Group Assignment

There were 32/33 participants confirmed to have IBS by Rome III criteria, and those with IBS were allocated to one of three groups based on stool subtype severity using the FBDSI.

Three focus groups were set up for 33 patients with IBS, however, only 16 attended: IBS-C (anticipated five, actual two), IBS-D (anticipated eight, actual five) and IBS-M (anticipated 20, actual nine). The reasons for not attending were related primarily to illness (n = 4), or other reasons (n = 4), and no reason given (n = 4). There were five who did not show up, three of whom were living in other states (PA, CA, NY).

Conduct of the Focus Group

The focus groups were conducted based on standardized methods as previously employed by some of the investigators in developing quality-of-life instruments [7, 8]. Key elements include [3]: (1) small group size to permit sharing of ideas, (2) participant homogeneity with the same diagnosis but with variation in certain clinical features that cover the full spectrum of the condition, (3) use of open-ended questions to facilitate discussion, (4) focused question topics to addresses the specific aims, (5) audiotape and note taking of responses for later review, and (6) debriefing to consolidate key ideas by consensus among the facilitators and the other investigators present and not present during the sessions.

The three focus groups were held at the Intercontinental Hotel in Milwaukee, WI, on October 27, 2007. There were three 90-min sessions with 1-h breaks between each session to allow for debriefing. After the aims of the focus group and the collaborative nature of the project were explained, two of the authors (DAD, LC), facilitated the group discussions, and others either observed the sessions (NN) or observed and independently took notes (CB, SS). The sessions were recorded.

The facilitated discussion was conducted in a specific order (see Appendix): first, the participants were asked to describe themselves, their IBS, and any other medical conditions. They were then asked how IBS affects their lives, and to describe their quality of life in general. Finally, they were asked to self-rate the severity of their IBS (mild, moderate, severe), and finally were asked what it means if their symptoms are severe, and which factors relate to or determine severity. The questions were designed to accomplish three aims: (1) to obtain a general assessment of the symptoms experienced with IBS and its impact in terms of activity limitations and quality of life; (2) to identify the nature and priority of factors associated with self-perceived severity; and (3) to determine if there are any differences based on predominant stool pattern.

For topics where an ordering of responses was required, participants were asked to vote on the most important factors. The voting results were recorded on easel boards. In the IBS-D and IBS-M groups, participants were asked to list items and then vote by hand, but because the IBS-C group was small, just a count of endorsements was obtained from the session notes.

Each subject received a $50 gift certificate and a gift bag of IFFGD publications at the end of the session.

Debriefing and Analysis

After completion of the focus group sessions, the moderators and note-takers convened to debrief and consolidate the responses to the questions. Recordings of each group were independently reviewed and assessed by two other individuals (WN and Audra Baade of IFFGD) who were not present during the focus groups. After their independent reviews, the two met to summarize their observations and consolidate them into a final report. Thus, each investigator made connections of ideas and themes from a variety of data sources (direct observation of the sessions, tape recordings, notes), which were then later corroborated with other investigators and finally compiled into a consensus report. Demographic and clinical information was obtained through questionnaires that were filled out by the participants before the focus group session began.

Results

Group Composition

Table 1 shows the composition of the 16 participants in the three groups. In general, the participants were middle-aged to older Caucasian women with moderate to severe symptoms. They lived in Wisconsin, Illinois, or Minnesota. Eight were currently working, seven were not working (three due to health problems) and one was retired. Most had moderate to severe IBS.

Responses to Group Questions

In general, there were few differences across the bowel subtype groups. Therefore, this report generally reflects a homogenization of the entire sample.

Tell Us About Yourselves

Most of the participants addressed the nature and timing of symptoms, but then went on to express concerns about the effects of having the symptoms: “…people don’t want to talk about it”, “…you can’t live a normal life”, “…the fear of having an attack is worse than the attack”, “I didn’t tell my husband – I don’t tell my friends… it’s embarrassing”. Some also gave their reasons for attending the focus group, frequently expressing that they wanted to hear ideas for managing their symptoms and to know more about research in order to gain some better understanding and in some way to get help.

Tell Us About Your IBS

Pain was universally endorsed, and reports of constipation and diarrhea related to the subgroup classification (Table 2). About half of the participants in the IBS-D and IBS-M groups mentioned experiencing fecal incontinence and two also had urinary incontinence. Other common symptoms included bloating, nausea, and muscle pains, and specifically with IBS-D, gas, mucus in stool, and belching. Other symptoms did not relate to any particular group.

Participants actively discussed the impact or the implications of having IBS according to certain themes:

-

(1)

Uncertainty and unpredictability surrounding symptom occurrence. Patients never knew where, when, or what would trigger a flare of symptoms. They were uncertain as to how much or what to eat, and they adapted to this in several ways: dietary manipulations, reducing participation in daily activities, bathroom awareness (for those when eating leads to diarrhea), and having routines that made them feel safe.

-

(2)

Feelings of perceived loss. This was manifest as a lack of ability to move about freely or have freedom at the workplace, modifications that needed to be made with family or social situations, difficulties in having satisfying sexual interactions, lack of spontaneity, and a perceived loss of potential, which they related to having pain and its uncertainty. Participants also described a loss of social contacts, of living in an ever-shrinking world. Several expressed the effects as a “loss of life” or “loss of living.”

-

(3)

Emotional responses. All participants acknowledged feelings of fear, distress, or frustration due to difficulties managing their IBS. Those with lower levels of distress had developed ways to adapt to their condition.

-

(4)

Feelings of shame. Participants reported that they did not speak to others about their symptoms and hid their condition because they considered it shameful. Related feelings included embarrassment, a sense of degradation, and disgust.

Tell Us About Other Medical Conditions

Participants endorsed a number of concomitant medical conditions, both in groups and on their screening questionnaires. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) was the only other GI symptom reported by three individuals, and fibromyalgia, depression, asthma, seasonal allergies, and osteoporosis was reported by two. A variety of other conditions were reported but with no particular pattern with regard to patient groupings.

How Does Your IBS Affect Your Life?

Almost all participants stated that IBS had a significant impact on their lives: how they thought and felt about it, and how they adapted to it (see Table 3):

Impact of the IBS Experience

IBS led to restrictions in many areas of life, such as: (a) social activities and relationships, (b) meals and going to restaurants, (c) work activities with difficulties controlling the work schedule, problems leaving the house or being near a bathroom—all of which reduced work productivity, and (d) leisure activities, leading to difficulties in planning trips and vacations. These restrictions on activities occurred even when symptoms were not present.

Cognitions and Emotions

Because impact of IBS was considerable, patients reported having frequent, and at times, unwanted thoughts, even when not experiencing symptoms. These thoughts and emotions further impaired their daily functioning and it was difficult to adequately carry on their daily life and self-manage the condition.

The thoughts and emotions included:

-

a.

Anticipatory concerns, which necessitated advanced planning to engage even in normal activities (e.g., knowing the locations of bathrooms out of the home, or getting up early and not eating prior to leaving the house)

-

b.

Loss of control or fear of loss of control over symptoms (including incontinence). This was of great concern when in social/professional environments

-

c.

The physical impact experienced. Feeling fatigued was common. One person stated: “I have nothing left at the end of the day”, and “I put so much energy into maintaining my body, I push my relationships aside.”

-

d.

The emotional impact of having IBS included feelings of fear (most common), embarrassment and shame, uncertainty, frustration, and degradation, particularly when having symptoms

-

e.

Feelings that others did not understand their condition. This was associated with a range of responses from feeling degraded by the social stigma of having bowel problems, to frustration particularly if their spouse did not understand them (even if they were supportive). The feeling that others did not understand was a barrier to having normal social interactions

Adaptations to Illness

Adaptations to illness were often influenced by past incidents (e.g., having an accident, not being near a bathroom, getting “sick”). The impact of these incidents often led to the avoidance of activities, constant monitoring of symptoms, and/or adaptations in routines to allow them to engage in activities in an effort to regain control. Relationship difficulties (both social and intimate) were commonly reported, and were associated with avoidance or emotional withdrawal in interactions with spouse, family, or friends. The reduced drive to engage in social interactions was attributed to feelings of fatigue.

Thus, we observed two levels of response with regard to the effect of IBS: (a) the direct functional, social, and emotional impact imposed by the IBS and (b) the thoughts and behaviors generated that impaired their sense of ability to manage this condition. This led to effects on their sense of themselves, their self-efficacy and their capabilities, even when not currently symptomatic.

How Would You Describe Your Quality of Life?

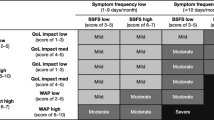

Each group was asked about the nature and severity of their HRQOL with IBS and to identify the factors that affected it. The italicized items in Table 4 received the most frequent endorsement from the members of the group; the most notable were pain, mood disturbance, interference in carrying out usual activities, and worrying about what might happen in the future.

Several themes were noted:

-

1.

Generally, HRQOL was felt to be impaired, with a range of responses from mild to severe. One participant felt she had “zero” quality of life, at least some of the time. One person expressed that her quality of life was “in the toilet” and this statement garnered agreement from others. Several people expressed that their quality of life was variable from day to day. No one stated they had a good quality of life.

-

2.

Many displayed a positive and hopeful outlook, despite commonly experiencing pain, incontinence/urgency, and intrusion of symptoms into their daily lives. They seemed optimistic that the medical field would someday find better answers for them, and perceived that for now, they are mostly on their own. The participants were positive about being in the focus group with people who understand them. This was echoed as a need in daily life: to have people that understand and share their experiences.

-

3.

Quality of life was reported as MORE than just symptoms. The only symptom multiply endorsed as a measure of QOL was the amount of pain or discomfort, but that was further clarified to include how much the pain interfered with other activities, Including thinking and concentration. Otherwise, there was no agreement on what else defines it. Some interpreted HRQOL as impaired functioning (the degree of not being able to engage in normal activities), or as impairment related to the number of restrictions on their activities. For others, it was the psychological effect: how much worry, anticipation and anxiety they felt, even when no symptoms were present. Their condition and the degree of HRQOL impairment was ever present on their minds, resulting in adaptations, restrictions, and loss of freedom. Finally, most all expressed that the feeling of being misunderstood or cut off from others adversely affected their QOL.

Based on these observations, we note that HRQOL covers a wide range of experiences and is understood conceptually as different from symptoms per se. It related to how the symptoms impacted and interfered with their life in terms of daily functioning and emotional effects. This was aggravated when individuals felt misunderstood or apart from others.

How Severe Is Your IBS (Severity Self-Rating)?

Most perceived themselves as having IBS in the moderate to severe range. Those with IBS-C or IBS-M reported more severe symptoms and the IBS-D group rated themselves as mostly moderate: IBS-M group (one mild, five moderate, three severe), IBS-D group (one mild, four moderate), IBS-C (two severe). The two participants who rated themselves as mild clarified that they would have rated themselves as more severe before hearing how IBS affected everyone else in the group.

What Does It Mean if Your Symptoms Are Severe? Factors Affecting Severity

Participants were asked to describe what it meant for their IBS to be severe, i.e., which factors were associated with severity. Participants were prompted to address the following domains: (1) GI symptoms of pain, diarrhea, constipation, bloating, incontinence, etc., (2) non-GI symptoms (fatigue, low energy, sleep disturbance, or other symptoms), (3) activity limitations (eating, work, getting out of the house, socializing, romance/sexual, traveling, etc.), (4) cognitive (e.g., memory, concentration, focus on tasks, etc.), (5) emotional (e.g., angry/frustrated, sad, anxious, etc.), (6) overall quality of life. A variety of items were endorsed spontaneously as shown in Table 5 and only three items required prompting by the facilitators (noted in table by a).

Which Items Are Most Important in Terms of Severity?

The most important factors relating to severity were (endorsed by four or more): pain (n = 12), interference with work or other activities (n = 9), restrictions when there was no control (n = 8), fatigue (n = 7), unpredictability (n = 6), intensity of symptoms (n = 5), memory or concentration difficulties (n = 4), food selection or restriction (n = 4), anxiety (n = 4), bloating (n = 4), and constancy of symptoms (n = 4). Pain and fatigue were endorsed in all three groups.

Thus, severity although understood in part as worsening pain symptoms, was frequently interpreted as relating to many other experiences, e.g., to restrict activity, feeling not in control, feeling the symptoms are unpredictable and when there were psychological affects including impaired memory or concentration or anxiety and fatigue. Participants could not easily separate HRQOL from the concept of severity.

Additional Themes Identified

Societal Stigma

The sense of stigma was due to perceptions of altered societal values as to how IBS affects people. This was elaborated to mean either that others did not accept IBS as an explanation for the participant’s feelings or behaviors (e.g., needing to take time off from work or expressing disinterest in intimacy), or that others expressed lack of understanding by trying to make a “quick-fix” though advice (e.g., “you need to relax” or “try to focus on something else”. The authors interpreted these statements as methods to invalidate the complexity and severity of the disorder. The participants noted that they did not want pity; they wanted hope, and validation from friends, family, and health care providers alike as to the reality of these disorders and their effects.

Many participants were so dissatisfied with the responses from family, friends, and even their spouses that they did not feel able discuss their disorder with them. They experienced difficulties relating to the stigmatizing attitudes and behaviors of others. One male participant with IBS-D shared that when he went to parties, he only drank water, as alcohol would cause a symptom flare-up. He noted that the side benefit was that people would be less stigmatizing when others thought he was avoiding alcohol in general: “I’d rather be thought of as an alcoholic than to be seen as having IBS.” He also avoided activities where he might have to explain that he had IBS. Some participants actively sought individuals who they felt were understanding.

Not feeling understood came not only from friends and family, but also from health care providers. One stated “…some doctors are on top, some are on the bottom,” referring to how much they understand the disorder. On balance, others communicated confidence in their doctors.

Many participants expressed that if the stigma were removed, it “…eased the burden of the illness”. This could occur by being surrounded by other people who understood them and their experiences. The focus group was acknowledged to help in this understanding. One person stated: “I didn’t tell my husband, don’t tell my friends. I feel lots better now that I can talk about it”.

Self-Management

The participants varied as to how they functioned with their IBS. A few claimed that the IBS did not affect their ability to go about their daily activities, because they refused to allow this to occur. They prepared well (e.g., carrying diaper bags or other absorbent products, avoiding food) or removed it from intruding in their thoughts (e.g., “I don’t let it affect me”). Others more actively needed to avoid food-oriented activities, but were still able to participate in food “neutral” activities. A few participants having difficulty managing their symptoms voiced their ability to find surrogate sources of satisfaction, i.e., they were “living through other people” by immersing themselves in the activities of children or family members. They felt a sense of enjoyment and participation that was not available to them personally. Still others were almost entirely disabled from being able to engage in normal daily life at all.

Discussion

There has been increased scientific attention to understanding the nature of medical disorders from the patient’s perspective. With regard to IBS, previous efforts often have relied on physician assessments about the patient, or on clinical surveys where the questions are developed by study investigators. These methods are insufficient when assessing illness experience such as quality of life or severity. Efforts to obtain patient-based data have resulted in the development of HRQOL instruments. HRQOL instruments are standardized to patient reports, and are used in health-status assessment and as secondary outcomes in treatment trials. Furthermore, recent directives by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [9] now require investigators to use patient rated outcomes (PRO) [10] as primary clinical endpoints for treatment trials.

This method of assessing the patient’s perspective is relevant to measuring severity in IBS. With inflammatory bowel disease, esophageal reflux disease, or acid peptic disease, severity is quantified by the degree of inflammation observed [1]. In contrast, IBS and other functional GI disorders have no biomarkers and require a variety of heuristic methods to assess severity. In fact, a recent review of studies about severity in IBS indicates that the prevalence of individuals with severe IBS ranges from 3 to 69%, and the severity questionnaires are based on physician assessments rather than patient assessments as the gold standard [4, 5]. The authors concluded that there currently is no standard to determine severity for this condition and that further work is needed to develop and standardize patient-based severity instruments [2].

The use of focus groups is an accepted means to address the patient’s experience of IBS and its severity in research and patient care. This method first began during World War II to gain insights into how soldiers were affected by the war. The process was later adapted for market research to promote consumer products, and by nonprofit groups to improve the design and promotion of public programs and services. In the last decade, focus groups have been applied in IBS to better characterize the patient’s experience of illness [11], to develop educational materials [12], or, as in our research group, as an entry point to develop standardized health-status research instruments [7, 13, 14]. Herein, we used focus group methodology to evaluate from the patient’s perspective of the nature of IBS and the factors contributing to its severity; several findings are noted:

First, the symptom patterns were similar to that found in other studies. Pain was universally endorsed, and constipation and diarrhea or bowel-associated symptoms (e.g., urgency with diarrhea, not feeling finished with constipation) related to the predominant stool pattern (IBS-D, IBS-C, IBS-M). Other symptoms included bloating, nausea, and muscle pains. This is similar to a recent study of 755 patients recruited at a university medical center where the factors predicting patient “overall severity of GI symptoms” included pain, straining, bloating, urgency, and muscle aches [15]. Also, in our study, those with IBS-D specifically reported mucus in the stool, gaseousness, and belching, though due to the small sample size, it is unclear whether this is specific only to this subtype of IBS.

Second, the participants focused a great deal on the implications of IBS on daily functioning relating to: (1) uncertainty and unpredictability of the symptoms, i.e., when they might occur and how severe they would be, (2) the loss of freedom, spontaneity in actions, and even of social contacts, (3) a need to impose restrictions on many areas of their home, work and social life and, importantly, these restrictions “spilled over” and were imposed even when symptoms were not present.

Third, IBS led to several cognitive and emotional responses. Reports of feeling fearful with anticipatory concerns (e.g., of needing to urgently get to a bathroom when out of the home), frustration with the inability to control the symptoms, and feelings of social isolation were common to many. Several reported feelings of shame, embarrassment, and degradation, particularly when experiencing symptoms. A common theme was to perceive social stigma when others did not understand or accept their feelings as reality-based, and that IBS is the explanation for these emotions and subsequent behaviors (e.g., to take time off for work or limit social functioning). Even though family, friends, and some physicians made efforts to be supportive, their lack of understanding as to the complexity and severity of the disorder was evident: some ignoring or minimizing their experiences, telling them to “relax” or “do something else”. Not being understood created a barrier to their normal functioning, but this could be ameliorated when the participants felt understood. This was acknowledged to occur in the focus group.

Fourth, the cognitive and emotional effects led to behavioral responses, including avoidance of activities, constant monitoring of symptoms, and/or changes in routines in an effort to regain control. Relationship difficulties (both social and intimate) led to avoidance or emotional withdrawal with spouse and family or in social relationships, and this produced fatigue.

Fifth, it is noted that despite these difficulties, most participants felt a sense of optimism for the future, and a belief that new treatments would be found. In addition, all endorsed the value of the focus group in validating their thoughts and feelings, and noted that feeling understood by others helps them to function better with their IBS. These observations highlight the value of peer support systems as a therapeutic modality.

Finally, the concept of severity was linked to, but not completely associated with, HRQOL. HRQOL was not just symptoms; it covered a wide range of experiences: the impact of the condition and its behavioral and emotional effects. Similarly, severity was viewed in this multi-component fashion and included: (1) symptoms of pain and its intensity, bloating, and non-GI symptoms of fatigue, anxiety and memory/concentration difficulties, (2) interference with eating and restrictions in the types of food and of daily activities including work, and (3) high degrees of unpredictability. These observations are consistent with a recent Internet survey of 1,966 patients with IBS [15]. When offered a checklist of 14 items thought to contribute to severity, the most common one reported (endorsed by 50% or more) included: pain, bowel difficulties, bloating, limitations on eating/diet, social activities and work, and inability to leave home. Thus severity in IBS would be a composite of most or all of these factors. We believe this information could help to develop patient-based indices of IBS illness severity or to define clinical endpoints for treatment trials.

There are several study limitations to be noted. Only 50% (16/32) of those invited actually attended the focus groups. However, given that some did not attend because of illness as well as the travel distance required, we do not believe there is evidence for an ascertainment bias. In addition, the IBS-C group contained only two patients, which is too small to adequately determine any subtype difference compared to the IBS-D or IBS-M groups. However, in general, we did not identify many differences in health status and illness severity based on stool subtype, as has been shown in other studies as well [16]. Another limitation relates to the self-selection of the patient sample into the study. Notably, these patients were older, primarily female, and with more severe illness than is seen in population studies or primary care practices. The study results are similar to patients seen in referral centers and particularly as we have found, among those who actively use the Internet [16]. Therefore, these data would be best applied to patients with moderate to severe symptoms who actively seek treatment. Finally, one could argue that some of the investigators who actively work in the area of patient advocacy might be biased, and this might affect the nature of the questioning or the interpretation of the responses. We attempted to address this by obtaining and evaluating the data using rigorous methods consistent with standard focus group study design [3].

In conclusion, our study confirms the heterogeneous and multi-component nature of IBS in terms of its symptoms and its impact on patient thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, all of which contribute to health status and illness severity. These factors are not related to specific stool subtype. We provide an entry point to understand this complex condition from the patient’s perspective and believe this information can be used in developing health status and severity instruments for clinical research and the development of endpoints in treatment trials. These qualitative data provide a basis for more quantitative assessments in larger studies.

References

Garrett JW, Drossman DA. Health status in inflammatory bowel disease: biological and behavioral considerations. Gastroenterol. 1990;99:90–96.

Lembo A, Ameen V, Drossman DA. Irritable bowel syndrome: toward an understanding of severity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:717–725. doi:10.1016/S1542-3565(05)00157-6.

Krueger RA. Quality of life and pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials. In: Spilker B, ed. Group dynamics and focus groups, vol. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996:397–402.

Drossman DA, Li Z, Toner BB, et al. Functional bowel disorders: a multicenter comparison of health status, and development of illness severity index. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:986–995. doi:10.1007/BF02064187.

Francis CY, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: a simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:395–402. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.142318000.x.

Spiegel BMR, Naliboff B, Mayer E, Bolus R, Chang L. Development and Initial Validation of a Concise Point-Of-Care Severity Index in IBS: The “B.E.S.T.” Questionnaire. 130 ed. 2006:A513.

Patrick DL, Drossman DA, Frederick IO, DiCesare J, Puder KL. Quality of life in persons with irritable bowel syndrome: development of a new measure. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:400–411. doi:10.1023/A:1018831127942.

Drossman DA, Leserman J, Li Z, Mitchell CM, Zagami EA, Patrick DL. The Rating Form of IBD Patient Concerns: a new measure of health status. Psychosom Med. 1991;53:238.

US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER), Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH). Guidance for industry patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4(79):1–32.

Patrick DL, Burke LB, Powers JH et al. Patient-reported outcomes to support medical product labeling claims. 2009.

Bertram S, Kurland M, Lydick E, Locke GRIII, Yawn BP. The patient’s perspective of irritable bowel syndrome. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:521–525.

Kennedy A, Robinson A, Rogers A. Incorporating patients’ views and experiences of life with IBS in the development of an evidence based self-help guidebook. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;50:303–310. doi:10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00054-5.

Drossman DA, Li Z, Toner BB, Diamant NE, Creed FH, Thompson D, Read NW, Babbs C, Barreiro M, Bank L, Whitehead WE, Schuster MM, Guthrie EA. A multi-national comparison of symptoms and health status of gastroenterology patients with functional bowel disorders. 106 ed. 1994:A489.

Drossman DA, Patrick DL, Whitehead WE, et al. Further validation of the IBS-QOL: a disease specific quality of life questionnaire. Am J Gastoenterology. 2000;95:999–1007. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01941.x.

Spiegel B, Strickland A, Naliboff BD, Mayer EA, Chang L. Predictors of patient-assessed illness severity in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol.. 2008;103:2536–2543. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01997.x.

Drossman DA, Morris C, Schneck S, Hu Y, Norton NJ, Norton WF, Weinland S, Dalton C, Leserman J, Bangdiwala SI. International survey of patients with IBS: symptom features and their severity, health status, treatments, and risk taking to achieve clinical benefit. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009; In press.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an educational grant from the Rome Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Drossman, D.A., Chang, L., Schneck, S. et al. A Focus Group Assessment of Patient Perspectives on Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Illness Severity. Dig Dis Sci 54, 1532–1541 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-009-0792-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-009-0792-6