Abstract

Helicobacter DNA has been detected in the liver specimens of patients with various hepato-biliary diseases. The aim of this study was to investigate the presence of H. pylori DNA in the liver tissue of Iranian patients with chronic liver diseases (CLD). Genomic DNA was extracted from the paraffin sections of 46 liver biopsies of patients with CLD and 13 from patients with metastatic adenocarcinoma as a control group. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis was carried out using primers for H. pylori 16S rRNA and cagA genes. On analysis, 17 of the 46 patient samples were positive in H. pylori 16S rRNA PCR and 2 of the 13 were positive from the control group. None of the samples were positive for the cagA gene. This study showed the greater presence of H. pylori-like DNA in the liver samples from patients with CLD than in controls.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative and microaerophilic microorganism that can cause chronic gastritis, peptic ulcers, and gastric adenocarcinoma [1, 2]. Besides these gastroduodenal diseases, H. pylori has been implicated in extra-gastric disorders, including ischemic heart disease [3], neurologic diseases, iron deficiency anemia [4], and respiratory diseases [5]. Helicobacter spp. infections have been reported to be associated with certain liver diseases in some animal species, such as H. canis in dogs [6], H. pullorum in poultry [7], and H. hepaticus and H. bilis in mice [8, 9].

Firstly, the possible colonization of the human hepato-biliary system by Helicobacter spp. have been reported by Fox et al. [10], who have shown the presence of H. bilis and H. pullorum in the bile of Chilean patients with chronic cholecystitis. Recently, Helicobacter DNA has been found in the liver of patients with different chronic liver diseases (CLD), such as primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) [11], hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [12], hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related chronic hepatitis, and cirrhosis [13, 14]. CLD is an inflammatory disease and each inflammatory process is characterized by increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukins 1 and 6 (IL-1 and IL-6), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and by the presence of lympho-mono cellular infiltrate and lymphoid follicle formation [12].

A Helicobacter-positive diagnosis based on H. pylori and Helicobacter genus-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays and the sequencing of PCR products showed a high homology to H. pylori [12–15]. The aim of this study was to determine whether genomic H. pylori sequences were detectable in the archival samples of Iranian patients with CLD.

Methods

Tissue Collections

Paraffin blocks of 46 liver biopsies from patients with CLD were evaluated. These included patients with chronic hepatitis (n = 28), non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases (NAFLD, n = 11), cirrhosis (n = 4), and HCC (n = 3). The age range of the patients was from 17 to 85 years, with 19 women and 25 men. Nine patients were positive for anti-hepatitis B virus (HBV) and five patients were anti-HCV positive. Paraffin blocks of 13 liver biopsies from patients with metastatic adenocarcinoma were used as controls. All paraffin blocks were collected from the Pathology Department of the Mehr Hospital and Milad Hospital, in Tehran, Iran.

DNA Extraction

The liver tissue samples were de-embedded by washing in xylene for 2 × 30 min. The specimens were then rehydrated through graded ethanol (99%, 80%, 60%, and 40%) for 5 min, and finally washed for 5 min in double-distilled water. DNA was extracted from sections using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany), according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The DNA was stored frozen at −20°C until its use as the template in the PCR.

PCR Amplification

The oligonucleotide primers used to amplify a segment of the H. pylori genes were selected to produce a small amplicon, since specimens that had been fixed with formalin were the source of the DNA [16, 17]. Two sets of primers (Metabion International AG, Germany) were used in this protocol. Initially, samples were amplified by H. pylori 16S rRNA primer, as described by Weiss et al. [18]. The sequence of the sense primer (JW21) was 5′-GCGACCTGCTGGAACATTAC-3′ (position 691–710) and the antisense primer (JW22) was 5′-CGTTAGCTGCATTACTGGAGA-3′ (position 829–809). The forward and reverse primers amplified a product of approximately 139 bp. The amplification conditions were: 95°C for 5 min; 35 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s; and finally 72°C for 2 min.

Samples generating a positive result from the first step of PCR were subsequently analyzed with cagA primer as described by Pellicano et al. [12]. The cagA-1 (5′-ATAATGCTAAATTAGACAACTTGAGCGA-3′) and cagA-2 (5′-TTAGAATAATCAACAAACATCACGCCAT-3′) amplified a 290-bp product from the cagA gene. The amplification conditions were: 94°C for 5 min; 35 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 61°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min; and finally 72°C for 2 min.

The PCR reaction mixture for the two sets of primers contained: 5 μl PCR buffer 10× (Roche, Germany, 25 mM Mgcl2), 200 μM deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate (Roche, 1 mM), 10 pmol of each primer, 2.5 U Taq DNA polymerase (Roche, Germany, 5 U/μl), and 10 μl of DNA in a total volume of 50 μl. The PCR products were analyzed on 2% (w/vol) agarose gel, which were stained with ethidium bromide and observed under short-wavelength ultraviolet light.

We used two positive controls; the first was DNA extracted from paraffin-embedded gastric biopsy specimens from patients with a known peptic ulcer caused by H. pylori and the second was DNA from pure H. pylori culture that was isolated from gastric biopsy and confirmed by microbiology tests. Each amplification contained positive (H. pylori genomic DNA) and negative (distilled water) controls to exclude cross-over contamination.

Results

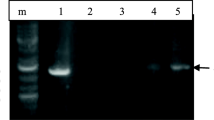

PCR analysis using H. pylori 16S rRNA primer was positive in 17 of 46 (36.9%) samples with CLD and in 2 of 13 (15.3%) controls. The distribution of H. pylori-positive samples among the different patient groups is shown in Table 1. Under ultraviolet illumination, the size of the PCR product corresponded to the expected 139 bp (Fig. 1). H. pylori DNA was detected in 7 of 14 (50%) patients with HBV and HCV infection. None of the 17 H. pylori-positive samples reacted in the PCR assays using primers for the cagA gene.

Discussion

The postulated role of H. pylori in the pathogenesis of extra-gastric manifestations is based on the fact that: (1) local inflammation has systemic effects; (2) H. pylori gastric infection is a chronic process lasting for decades; and (3) persistent infection induces a chronic inflammatory and immune response which are able to induce lesions both locally and remote to the primary site infection [13, 19]. In addition, Helicobacters are strong inducers of inflammatory cascade; infection with them could lead to the accumulation of an extraordinary number of lymphocytes and polymorphonuclear cells in the infected tissue. It has been shown that Helicobacter spp. could also secrete a liver-specific toxin that causes hepatocyte necrosis in cell culture, and might, therefore, also be involved in damaging liver parenchyma in vivo [12].

Recently, several separate research groups have detected Helicobacter spp. in the bile, gallbladder [20, 21], and liver tissue of patients with different hepato-biliary diseases. Nilsson et al. [22] have identified H. pylori in human liver samples patients suffering from primary sclerosing cholangitis and primary biliary cirrhosis. Avenaud et al. [23] have shown the presence of Helicobacter spp. genomic sequences in the liver tissue of eight patients with primary liver carcinoma. Tolia et al. [24] have demonstrated, by PCR, the presence of genomic sequences of Helicobacter spp. in the liver tissue of 40 patients with miscellaneous liver diseases; a further analysis by sequencing revealed that most of these species were H. pylori. Furthermore, a high prevalence of antibodies to H. pylori in the serum of patients with chronic hepatitis and in patients with cirrhosis have also been reported [25, 26]. Iranian investigators have detected H. pylori DNA in 4 of 36 bile samples from patients with biliary diseases [27]. These observations suggested that Helicobacter spp., including H. pylori, might play a role in the development of hepato-biliary diseases.

In the present study, which composed of two groups, we detected H. pylori-like DNA in 17 of 46 (36.9%) liver samples from patients with CLD, whereas only 2 of 13 (15.3%) samples were positive in the controls. Moreover, 7 of 14 (50%) samples from patients with HBV or HCV infection were positive for H. pylori DNA. These data are in agreement with the published studies, which have shown a higher frequency of Helicobacter spp. in the liver samples of patients with HCV or HBV infection [24].

The cytotoxin-associated gene (cagA), which encodes an immunodominant antigen and is a marker for the presence of the cag pathogenicity island (cag PAI), is not present in all H. pylori strains [28]. Xuan et al. [29] have detected the cagA gene in only 3 of 17 (17.6%) positive samples from patients with HCC. Stalke et al. [30] have identified Helicobacter species in the liver and stomach tissue of Polish patients with CLD PCR denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis and immunohistochemistry. Their results have shown that H. pylori-like organisms appeared to dominate the gastric mucosa and liver tissue patients. The prevalence of the cagA gene in positive samples was 36% (23 of 62) and 12% (3 of 25) for the stomach and liver, respectively [30]. In our study, none of the positive samples reacted in PCR assays using primers for the cagA gene. This discrepancy may be explained by the selection criteria of the patients. On the other hand, our results confirm that the cagA-negative strain has a role in liver diseases, as previously described [30].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the detection of Helicobacter spp. in patients with CLD in Iran. The main limitation of this study was its retrospective nature, which did not allow us to determine whether H. pylori was present in the stomach of these patients or to gather all of the clinical information and duration of infection, which is needed for a more accurate analysis.

In conclusion, we noticed that patients with various CLD had a greater probability of positive H. pylori-like DNA compared with the control group. To confirm these data, we need to sequence the PCR products and study other genes, such as vacA, ureA, and ureB. Indeed, to make clear the exact clinical role of Helicobacter species, namely, H. pylori in CLD, more studies on a larger population of patients and certain populations (e.g., those with HBV, HCV, and HCC) are needed.

References

Dunn BE, Cohen H, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:720–741.

Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori and gastric diseases. BMJ. 1998;316:1507–1510.

Murray LJ, Bamford KB, O’Reilly DP, McCrum EE, Evans AE. Helicobacter pylori infection: relation with cardiovascular risk factors, ischaemic heart disease and social class. Br Heart J. 1995;74:497–501. doi:10.1136/hrt.74.5.497.

Bohr UR, Annibale B, Franceschi F, Roccarina D, Gasbarrini A. Extragastric manifestations of Helicobacter pylori infection—other Helicobacters. Helicobacter. 2007;12:45–53. doi:10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00533.x.

Roussos A, Philippou N, Gourgoulianis KI. Helicobacter pylori infection and respiratory diseases: a review. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:5–8.

Fox JG, Drolet R, Higgins R, et al. Helicobacter canis isolated from a dog liver with multifocal necrotizing hepatitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2479–2482.

Ceelen L, Decostere A, Verschraegen G, Ducatelle R, Haesebrouck F. Prevalence of Helicobacter pullorum among patients with gastrointestinal disease and clinically healthy persons. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:2984–2986. doi:10.1128/JCM.43.6.2984-2986.2005.

Fox JG, Li X, Yan L, et al. Chronic prolifrative hepatitis in A/JCr mice associated with persistent Helicobacter hepaticus infection: a model of Helicobacter-induced carcinogenesis. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1548–1558.

Schomer NH, Dangler CA, Schrenzel MD, Fox JG. Helicobacter bilis-induced inflammatory bowel disease in scid mice with defined flora. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4858–4864.

Fox JG, Dewhirst FE, Shen Z, et al. Hepatic Helicobacter species identified in bile and gallbladder tissue from Chileans with chronic cholecystitis. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:755–763. doi:10.1016/S0016-5085(98)70589-X.

Krasinskas AM, Yao Y, Randhawa P, Dore MP, Sepulveda AR. Helicobacter pylori may play a contributory role in the pathogenesis of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2265–2270. doi:10.1007/s10620-007-9803-7.

Pellicano R, Mazzaferro V, Grigioni WF, et al. Helicobacter species sequences in liver samples from patients with and without hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:598–601.

Dore MP, Realdi G, Mura D, Graham DY, Sepulveda AR. Helicobacter infection in patients with HCV-related chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:1638–1643. doi:10.1023/A:1015848009444.

Rocha M, Avenaud P, Menard A, et al. Association of Helicobacter species with Hepatitis C cirrhosis with or without hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2005;54:396–410. doi:10.1136/gut.2004.042168.

Verhoef C, Pot RG, de Man RA, et al. Detection of identical Helicobacter DNA in the stomach and in the non-cirrhotic liver of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:1171–1174. doi:10.1097/00042737-200311000-00004.

Ben-Ezra J, Johnson DA, Rossi J, Cook N, Wu A. Effect of fixation on the amplification of nucleic acids from paraffin-embedded material by polymerase chain reaction. J Histochem Cytochem. 1991;39:351–354.

Greer CE, Wheeler CM, Manos MM. Sample preparation and PCR amplification from paraffin-embedded tissues. PCR Methods Appl. 1994;3:S113–S122.

Weiss J, Mecca J, da Silva E, Gassner D. Comparison of PCR and other diagnostic techniques for detection of Helicobacter pylori infection in dyspeptic patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1663–1668.

Realdi G, Dore MP, Fastame L. Extradigestive manifestations of Helicobacter pylori infection: fact and fiction. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:229–236. doi:10.1023/A:1026677728175.

Roe IH, Kim JT, Lee HS, Lee JH. Detection of Helicobacter DNA in bile from bile duct diseases. J Korean Med Sci. 1999;14:182–186.

Silva CP, Pereira-Lima JC, Oliveira AG, et al. Association of presence of Helicobacter in gallbladder tissue with cholelithiasis and cholecystitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5615–5618. doi:10.1128/JCM.41.12.5615-5618.2003.

Nilsson HO, Taneera J, Castedal M, Glatz E, Olsson R, Wadström T. Identification of Helicobacter pylori, other Helicobacter species by PCR, hybridization, and partial DNA sequencing in human liver samples from patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis or primary biliary cirrhosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1072–1076.

Avenaud P, Marais A, Monteiro L, et al. Detection of Helicobacter species in the liver of patients with and without primary liver carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;89:1431–1439. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(20001001)89:7<1431::AID-CNCR4>3.0.CO;2-5.

Tolia V, Nilsson HO, Boyer K, Wuerth A, Al-Soud WA. Detection of Helicobacter ganmani-like 16S rDNA in pediatric liver tissue. Helicobacter. 2004;9:460–468. doi:10.1111/j.1083-4389.2004.00266.x.

Fan XG, Zou YY, Wu AH, Li TG, Hu GL, Zhang Z. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with hepatitis B. Br J Biomed Sci. 1998;55:176–178. doi:10.1159/000028431.

Leone N, Pellicano R, Brunello F, et al. Helicobacter pylori seroprevalence in patients with cirrhosis of the liver and hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Detect Prev. 2003;27:494–497. doi:10.1016/j.cdp.2003.07.004.

Farshad S, Alborzi A, Malekhosseini SA, et al. Detection of Helicobacter DNA in bile samples of patients with biliary diseases living in south of Iran. Ir J Med Sci. 2006;31:186–190.

Camorlinga-Pance M, Romo C, Gonzalez-Valencia G, Muñoz O, Torres J. Topographical localization of cagA positive and cagA negative Helicobacter pylori stains in the gastric mucosa; an in situ hybridization study. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:822–828. doi:10.1136/jcp.2004.017087.

Xuan SY, Li N, Qiang X, Zhou RR, Shi YX, Jiang WJ. Helicobacter infection in hepatocellular carcinoma tissue. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2335–2340.

Stalke P, Al-Soud WA, Bielawski KP, et al. Detection of Helicobacter species in liver and stomach tissues of patients with chronic liver diseases using polymerase chain reaction-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis and immunohistochemistry. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:1032–1041. doi:10.1080/00365520510023251.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from the Iran University of Medical Sciences. Warmest gratitude to the Head and Staff of Keivan Laboratory for excellent technical assistance. Also, we thank staff of the Pathology Department of Mehr Hospital and Milad Hospital for their cooperation in collecting liver specimens.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pirouz, T., Zounubi, L., Keivani, H. et al. Detection of Helicobacter pylori in Paraffin-Embedded Specimens from Patients with Chronic Liver Diseases, Using the Amplification Method. Dig Dis Sci 54, 1456–1459 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-008-0522-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-008-0522-5