Abstract

‘Benifuuki’, a tea (Camellia Sinensis L.) cultivar in Japan, is rich in anti-allergic epigallocatechin-3-O-(3-O-methyl) gallate (EGCG3″Me). ‘Benifuuki’ green tea and simultaneous addition of ginger extract remarkably suppressed cytokine (TNF-α and MIP-1α) secretion from mouse bone marrow-derived mast cells after antigen stimulation and, as expected, suppressed delay-type allergy. After drinking ‘benifuuki’ green tea containing 43.5 mg of EGCG and 8.5 mg of EGCG3″Me, the AUC (area under the drug concentration time curve; min μg/ml) of EGCG was 6.72 ± 2.87 and EGCG3″Me was 8.48 ± 2.54 in healthy human volunteers. Though the dose of EGCG was 5.1 times the dose of EGCG3″Me, the AUC of EGCG3″Me was higher than that of EGCG. A double blind clinical study on subjects with Japanese cedar pollinosis was carried out. At the 11th week after starting the study, in the most severe cedar pollen scattering period, symptoms, i.e., blowing the nose and itching eyes, were significantly relieved in the ‘benifuuki’ intake group compared with the placebo group, and blowing the nose, itching eyes and nasal symptom score, and at the 11th and 13th weeks, stuffy nose, throat pain and the nasal symptom medication score were significantly relieved in the ‘benifuuki’ containing ginger extract group compared with the placebo group. These results suggested that over one consecutive month, drinking ‘benifuuki’ green tea was useful to reduce some of the symptoms from Japanese cedar pollinosis, and did not affect any normal immune response in subjects with seasonal rhinitis, and the ginger extract enhanced the effect of ‘benifuuki’ green tea.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Tea (Camellia sinensis L.) is consumed all over the world, and in large quantities in Japan and China, where it has been used for medicinal purposes for thousands of years. Tea has been found to exhibit various bioregulatory activities, such as anti-carcinogenetic (Kuroda and Hara 1999; Lin et al. 1999; Suganuma et al. 1999; Cao and Cao 1999; Ahmad et al. 2000; Lambert and Yang 2003), anti-metastatic (Isemura et al. 1993; Sazuka et al. 1995, 1997; Maeda-Yamamoto et al. 1999, 2003), anti-oxidative (Okuda et al. 1983; Bors and Saran 1987; Kimura et al. 2002; Hashimoto et al. 2003), anti-hypertensive (Yokozawa et al. 1994), anti-hypercholesterolemic (Murase et al. 2002; Chisaka et al. 1988; Matsumoto et al. 1998), anti-dental caries (Hattori et al. 1990; Sakanaka et al. 1992), anti-bacterial (Fukai et al. 1991), and to contribute to intestinal flora amelioration activity (Okubo et al. 1992). Catechins, a group of polyphenolic compounds, have been shown to be largely responsible for these activities.

Allergy has been defined as a disease of excessive immune activity, and in Japan, the morbidity of allergy is estimated to be about 30%. Many Japanese have misgivings about the use of anti-allergic medicine because of side effects and mounting medical expenses, so there is a demand for the development of physiological-functional foods for allergy prevention. An anti-allergic effect is a functional property in which catechins apparently play a significant role. We have reported that O-methylated EGCGs (epigallocatechin-3-O-(3-O-methyl) gallate (EGCG3″Me) and epigallocatechin-3-O-(4-O-methyl) gallate (EGCG4″Me)) (Sano et al. 1999; Suzuki et al. 2000; Fujimura et al. 2002; Maeda-Yamamoto et al. 2004) and strictinin (Tachibana et al. 2001) had anti-allergic action and that the Japanese tea cultivar ‘benifuuki’ was rich in EGCG3″Me, which disappeared in black tea (Maeda-Yamamoto et al. 1998, 2001). Oral administration of these methylated catechins significantly and dose-dependently (5–50 mg/kg) inhibited type I allergic (anaphylactic) reactions in mice sensitized with ovalbumin and Freund’s incomplete adjuvant. These catechins also strongly inhibited mast cell activation through the prevention of tyrosine phosphorylation (Lyn, Syk and Btk) of cellular protein and histamine/leukotriene release, interleukin-2 secretion after Fcepsilon RI cross-linking (Maeda-Yamamoto et al. 2004). In this paper, to examine the influence on not only immediate allergy but also delay-type allergy, we investigated the in vitro and in vivo effects of ‘benifuuki’ green tea containing O-methylated catechin and a combination of food components working synergistically with ‘benifuuki’ on inflammatory cytokine production from mast cells after antigen stimulation, symptom relief and safety in subjects with seasonal allergic rhinitis (a double-blind clinical trial), and the blood levels of unconjugated EGCG or EGCG3″Me after the administration of ‘benifuuki’ green tea to humans.

Materials and methods

Cells, stimulation, cytokine secretion

Bone marrow cells from the femurs of NC/Nga mice were cultured in 4 ng/ml of murine recombinant IL-3 (Peprotec, NJ, USA)-containing RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen Life Technologies, CA, USA), 2 mM glutamine and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol in humidified 95% air/5% CO2 at 37 °C. More than 95% pure mast cells were obtained as bone marrow-derived mast cells (BMMC) after 4 weeks of culture. BMMC cells were passively sensitized at a density of 2 × 106 cells/ml with 0.5 μg/ml anti-dinitrophenyl (DNP) mouse monoclonal IgE antibody (Sigma-Aldrich (MO, USA)) at 37 °C overnight. After washing in Tyrode buffer (Ca2+-free; 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4; Wako Chemical, Osaka, Japan; containing 0.8% NaCl, 0.02% KCl, 0.056% NaH2PO4, 0.1% glucose, 0.05% gelatin, and 1 μM MgCl2/6H2O), the cells were resuspended in Tyrode buffer at a density of 1 × 107 cells/ml, incubated for 20 min with samples at 37 °C, and then stimulated by 300 ng/ml of DNP-HSA (LSL Cosmo Bio, Tokyo, Japan) with 300 μM CaCl2 at 37 °C. About 18 kinds of cytokines secreted into the Tyrode solution during 2–4 h stimulation were measured by Bio-plex protein suspension array system (Bio-Rad, USA).

Overall, 2.5 g of ‘benifuuki’ green tea powder were extracted at 95 °C for 6 min with 25 ml of distilled water. After centrifugation, the polyphenol (tannin) content of the supernatant was measured by colorimetry using the ferrous-tartrate method (Iwasa and Torii 1962) and 50 μg tannin content added per 1 × 107 cells of BMMC. About 5 g of vegetables (broccoli sprout, radish sprout, red cabbage sprout, rucola sprout, ginger) were added to 5 ml of 50% ethanol and ground well in a mortar. After centrifugation at 6,000g for 15 min, the supernatant as vegetable extract was added to 50 μl of BMMC per 1 × 107 cells.

Blood levels of unconjugated GCG and EGCG3″Me after administration of ‘benifuuki’ green tea

Six healthy male and female subjects <40 years of age were recruited as participants in this study. Study participants were informed of all procedures and requirements for the study. All participants were required to refrain from ingesting tea or tea products for 3 days before this study. All procedures were in strict compliance with the study protocol, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asahi Soft Drinks Ltd. on Human Research. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The day before the study, all participants were instructed to fast after 9 p.m. except for drinking water. On the study day, all subjects skipped breakfast, came to the clinic and drank ‘benifuuki’ green tea containing 43.5 mg of EGCG and 8.5 mg of EGCG3″Me within 3 min. Blood samples (5 ml each) were collected before administration and 1, 6, 12, 24 h after ‘benifuuki’ green tea administration. After each blood collection, Japanese noodles without meat and vegetables were provided to all subjects. Blood samples were centrifuged at 4 °C and 0.4 ml of plasma was added to 0.2 ml of 0.2 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) supplemented with 0.5 mM EDTA and 0.2 ml of DW. The mixture was added to 0.8 ml of methylene chloride and mixed well with a vortex. The centrifuged supernatant (aqueous phase) was extracted with 5-fold ethyl acetate. The ethyl acetate fraction was dried by vacuum centrifugation. The dried sample was redissolved in 0.1 M NaH2PO4 buffer (pH 2.5) supplemented with 0.1 mM EDTA-acetonitrile (87:13) solution.

About 20 μl of the filtrate after filtration through a membrane filter (DISMIC-13HP-PTFE, pore size 0.45 μm, ADVANTEC, Tokyo, Japan) was injected by an autosampler (SIL-10Avp, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) into HPLC apparatus (Shimadzu class VP HPLC system). HPLC was performed with a Shimadzu LC-10A pump coupled with an electrochemical detector (Coulochem II, ESA, USA) using a reverse-phase Wakopak Navi C18-5 column (150 × 4.6 mm i.d., particle size; 5 μm, Wako Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) with Wakopak Navi C18-5 column (10 × 4.6 mm i.d., particle size; 5 μm, Wako Chemical) as a guard column eluted with the eluent described below at a flow rate of 1 ml/min at 40 °C. HPLC analysis was performed using a linear gradient system with mobile phase A (H2O-acetonitrile-H3PO4, 400:10:1) and mobile phase B (methanol-mobile phase A, 1:2). Linear gradient elution was performed as follows: 100% mobile phase A for 2 min; 20% mobile phase A for 27 min; maintained 20% mobile phase A for 10 min; and return to 100% mobile phase A for 7 min. The eluent was monitored by the Coulochem electrode array system with potential settings at −200 (E1) and 400 mV (E2). Quantification was carried out using the external standard method. Quantification of EGCG and EGCG3″Me was performed after data acquisition using an LC workstation (Class VP system, Shimadzu).

Human clinical trial on seasonal allergy rhinitis

About 18 male and 9 female subjects (>22 years of age) with a stuffy nose, itching eyes, a sore throat or persistent sneezing during cedar pollen season, and with a positive Japanese cedar pollen-specific IgE value without treatment at a medical institution were recruited as participants in this study. A researcher who did not participate directly in the final examination divided participants into three groups, a ‘benifuuki’ test group (7 men and 2 women, aged 39.1 ± 9.9 years old), a ‘benifuuki’ + ginger extract group (5 men and 4 women, aged 37.6 ± 10.3 years old) and a ‘yabukita’ placebo group (5 men and 4 women, aged 41.8 ± 12.3 years old), based on each cedar pollen-specific IgE value of blood. Study participants were informed of all procedures and requirements for the study. All procedures were in strict compliance with study protocol, which was approved by an Institutional Review Board of National Institute of Vegetable and Tea Science on Human Research. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The placebo, ‘yabukita’ green tea, did not contain EGCG3″Me whereas ‘benifuuki’ green tea contained 1.49%DB of EGCG3″Me, but the total catechin content of both was approximately 14%. During the test period, all subjects consumed 2 × 1.5 g tea bags with water every day. The ‘benifuuki’ + ginger test sample was supplemented with 30 mg of ginger extract per 1.5 g of tea powder and the ginger flavor was hardly noticed. This test started on December 17, 2004, approximately two months before cedar pollen season. Tea drinking started on December 22, 2004 and continued for 86 days (to March 18, 2005), and all tests finished on April 8, 2005. All subjects visited the hospital every 4 weeks for consultation, and blood and urine samples were taken each time for hematological examination, general biochemical examination, histamine content, IgE score, cedar pollen-specific IgE score, total IgG antibody titer, and serum iron content. During the test period, all subjects were required to write an ‘allergy diary’ which included the frequency of sneezing and nose blowing, a stuffy nose, itching eyes, the extent of eye watering, sore throat pain, difficulties in daily life, and use conditions of the medicine every day in accordance with the method proposed by the Japanese Society of Allergology Allergic Rhinitis Committee. Symptoms were evaluated from 0 (no symptoms) to 4 (severe symptoms present all day). The diary was collected at the end of examination and we calculated the Nose Symptom Score and Medication Score (pattern of taking medicine), and the Symptom Medication Score, the sum of both scores, according to the practical guidelines for the management of allergic rhinitis of the Japan Allergy Foundation.

Statistical analysis

We compared the test groups using the subjective symptoms of allergic rhinitis in the Mann-Whitney U-test as the object of analysis of the score frequency every 2 weeks.

Results and discussion

Cytokine secretion

Mast cells play a critical role in the effector phase of IgE-dependent immediate hypersensitivity and allergic diseases (Galli et al. 1999). Cross-linking of high-affinity IgE receptors (FcεRI) with IgE and allergen initiates the activation process, leading to the release of preformed and de novo synthesized vasoactive amines, proteases, leukotrienes, cytokines, and chemokines (Beaven and Metzger 1993; Kinet 1999; Kawakami and Galli 2002). These chemicals and polypeptide agents elicit various allergy-associated pathophysiological changes locally and systemically, for instance, amines, such as histamine and serotonin, enhance vascular permeability, and cytokines, such as TNF-α recruit inflammatory cells to the site of allergen exposure. Production increase by antigen stimulation was observed in IL-5, IL-6, IL-17, GM-CSF, TNF-α, MIP-1α from BMMC after antigen stimulation in 2 h, as shown in Table 1. Inflammatory cytokine TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor), eosinophil-migrating chemokine MIP-1α (macrophage inflammatory protein-1), and IL-6 were produced in particular abundance by antigen stimulation. Therefore, the inhibitory effect of ‘benifuuki’ green tea extract and the simultaneous addition of various vegetable extracts to ‘benifuuki’ green tea on cytokine (TNF-α or MIP1-α) production were investigated. As Fig. 1 shows, ‘benifuuki’ green tea inhibited TNF-α production by 38.9%, but only ginger showed 70.6% inhibition with the vegetable extract alone. Moreover, the inhibitory effect of ‘benifuuki’ on TNF-α production was enhanced approximately 2 times by adding broccoli sprout or white radish sprout extract, with 93.6% inhibition by administrating ginger and BF together. As mentioned above, MIP-1α production was suppressed 28.7, 55, and 84.2% by ‘benifuuki’, ginger and ‘benifuuki’ and ginger combination, respectively, as shown in Fig. 2.

‘Benifuuki’ green tea or the simultaneous administration of ‘benifuuki’ green tea and ginger extract strongly inhibited inflammatory cytokine production, such as TNF-α and MIP-1α, after antigen stimulation of BMMC. From these results, ‘benifuuki’ green tea or the combination of ‘benifuuki’ and ginger suppressed delay-type allergy by inhibiting inflammatory cytokine production.

Bio-availability

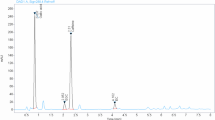

Figure 3 shows the average plasma unconjugated EGCG and EGCG3″Me concentration-time profile after ‘benifuuki’ green tea administration. After oral administration, plasma EGCG levels increased toward a peak and declined rapidly. On the other hand, the metabolism of EGCG3″Me was slow compared with EGCG. The AUC (area under the drug concentration time curve; min μg/ml) of EGCG was 6.72 ± 2.87 and EGCG3″Me was 8.48 ± 2.54. ‘Benifuuki’ green tea beverage contained 43.5 mg of EGCG and 8.5 mg of EGCG3″Me. Although the dose of EGCG was 5.1 times the dose of EGCG3″Me, the AUC of EGCG3″Me was higher than that of EGCG. Chow et al. (2001, 2003) reported that the peak of average plasma unconjugated EGCG was approximately 70, 75, 160 and 400 ng/ml at 4 h after oral administration of 200, 400, 600 and 800 mg of EGCG, respectively. From this result, it was suggested that free EGCG3″Me was more easily absorbed by blood in comparison with free EGCG; therefore, EGCG3″Me might be delivered in greater quantity to an inflammation location, with greater affect.

Plasma unconjugated EGCG and EGCG3″Me concentration versus time profiles after oral administration of ‘benifuuki’ green tea beverage. Each point represents the average of six subjects, and the cross-vertical bars represent SD of the mean. All subjects drank ‘benifuuki’ green tea containing 43.5 mg of EGCG and 8.5 mg of EGCG3″Me within 3 min

Clinical trial

A double blind clinical study on subjects with Japanese cedar pollinosis was carried out to evaluate the effect and safety of ‘benifuuki’ green tea, which contains EGCG3″Me and a combination of ‘benifuuki’ green tea and ginger extract, together with ‘yabukita’ green tea as a placebo. First, the effect of the simultaneous administration of ‘benifuuki’ green tea and various vegetable extracts on cytokine inhibition using mast cells was investigated, and the simultaneous administration of ‘benifuuki’ green tea and ginger extract remarkably suppressed cytokine production, as described above. The subjects therefore drank 1.5 g of each tea powder, ‘benifuuki’ green tea, ‘benifuuki’ green tea containing 30 mg of ginger extract, and ‘yabukita’ green tea, with water twice a day for 13 weeks. ‘Benifuuki’ or ‘yabukita’ green tea contained 44.7 or 0 mg of EGCG3″Me, 176.1 or 202.8 mg of EGCG, 71.4 or 84.6 mg of caffeine and 432 or 425 mg of total catechin per 3 g, respectively. As cedar pollen increased, the symptoms of pollinosis worsened in the order: placebo group > ‘benifuuki’ group > ‘benifuuki’ supplemented with ginger group. About 11 weeks after starting the treatment, in the most severe cedar pollen period, the symptoms, i.e., nose blowing and itching eyes, were significantly relieved in the ‘benifuuki’ group compared with the placebo group (p < 0.05), as shown in Fig. 4a and b. In the 11th week after starting the treatment, nose blowing, itching eyes and nasal symptom score, and in the 11th and 13th weeks, a stuffy nose, sore throat and the nasal symptom medication score were significantly relieved in the ‘benifuuki’ supplemented with ginger extract group compared with the placebo group, as shown in Fig. 4c. Among test groups, there were no changes related to clinical problems in the hematological examination, general biochemical examination, total IgG antibody titer, serum iron content, and interview throughout the intake period.

The effects of ‘benifuuki’ green tea and additive ginger extract on the symptom score of seasonal allergic rhinitis. All subjects drank 1.5 g of each tea powder, ‘benifuuki’ green tea, ‘benifuuki’ green tea containing 30 mg of ginger extract, and ‘yabukita’ green tea, with water twice a day for 13 weeks. Each point represents the average of nine subjects every 2 weeks and the cross-vertical bars represent SD of the mean. (a) blowing nose (0 (0 time)–4 (more than 21 times)), (b) itching eyes (0 (no)–4 (severe)), (c) nasal symptom medication score. *,**Significantly different from the placebo group (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01)

EGCG3″Me, an active factor in ‘benifuuki’, had an absorption ratio in the body about 6.4 times higher than EGCG, a high quantity of which is contained in general tea varieties such as ‘yabukita’.

Ginger is used as a Chinese medicine, and has anti-inflammatory effects (Thomson et al. 2002; Grzanna et al. 2005), antipyretic action, increased salivation, antitussive effect, analgesic effect, antidigestive ulcer, transportation promotion in the intestinal tract, and cardiotonic action. [6]-Gingerol included in ginger is supposed to have anti-inflammatory action (inhibition of prostaglandin E2 production) (Young et al. 2005) so we surmised that the anti-inflammatory action of gingerol had a strong inhibitory effect on inflammatory cytokines and the relief of seasonal allergic rhinitis symptoms by ‘benifuuki’ supplemented with ginger extract.

These results suggested that more than one consecutive month intake of ‘benifuuki’ green tea was useful to reduce some of the symptoms of allergic rhinitis, but did not affect normal immune responses in subjects with Japanese cedar pollinosis, and that ginger extract enhanced the effect of ‘benifuuki’ green tea.

Abbreviations

- EGCG:

-

Epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate

- EGCG3″Me:

-

Epigallocatechin-3-O-(3-O-methyl) gallate

- AUC:

-

Area under the drug concentration time curve

References

Ahmad N, Cheng P, Mukhtar H (2000) Cell cycle dysregulation by green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 275:328–334

Beaven MA, Metzger H (1993) Signal transduction by Fc receptors: the Fc epsilon RI case. Immunol Today 14:222–226

Bors W, Saran M (1987) Radical scavenging by flavonoid antioxidants. Free Radic Res Commun 2(4–6):289–294

Cao Y, Cao R (1999) Angiogenesis inhibited by drinking tea. Nature 398:381–382

Chisaka T, Matsuda H, Kubomura Y, Mochizuki M, Yamamura J, Fujimura H (1988) The effect of crude drugs on experimental hypercholesteremia: mode of action of (−)-epigallocatechin gallate in tea leaves. Chem Pharm Bull 36:227–233

Chow H-HS, Cai Y, Alberts DS, Hakim I, Dorr R, Shahi F, Crowell JA, Yang CS, Hara Y (2001) Phase I pharmacokinetics study of tea polyohenols following single-dose administration of epigallocatechin gallate and polyphenon E. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 10:53–58

Chow H-HS, Cai Y, Hakim IA, Crowell JA, Shahi F, Brooks IA, Dorr RT, Hara Y, Akberts DS (2003) Pharmacokinetics and study of green tea polyphenols after multiple-dose administration of epigallocatechin gallate and polyphenon E in healthy individuals. Clinical Cancer Res 9:3312–3319

Fujimura Y, Tachibana H, Maeda-Yamamoto M, Miyase T, Sano M, Yamada K (2002) Antiallergic tea catechin: (−)-epigallocatechin-3-O-(3-O-methyl)-gallate, suppresses FcepsilonRI expression in human basophilic KU812 cells. J Agric Food Chem 50:5729–5730

Fukai K, Ishigami T, Hara Y (1991) Antibacterial activity of tea polyphenols against phytopathogenic bacteria. Agric Biol Chem 55:1895–1897

Galli SJ, Maurer M, Lantz CS (1999) Mast cells as sentinels of innate immunity. Curr Opin Immunol 11:53–59

Grzanna R, Lindmark L, Frondoza CG (2005) Ginger -an herbal medicinal product with broad anti-inflammatory actions. J Med Food 8(2):125–132

Hashimoto F, Ono M, Masuoka C, Ito Y, Sakata Y, Shimizu K, Nonaka G, Nishioka I, Nohara T (2003) Evaluation of the anti-oxidative effect (in vitro) of tea polyphenols. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 67:396–401

Hattori M, Kusumoto I, Namba T, Ishigami T, Hara Y (1990) Effect of tea polyphenols on glucan synthesis by glucosyltransferase from Streptococcus mutans. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 38:717–720

Isemura M, Suzuki Y, Satoh K, Narumi K, Motomiya M (1993) Effects of catechins on the mouse lung carcinoma cell adhesion to the endothelial cells. Cell Biol Int 17:559–564

Iwasa K, Torii H (1962) A colorimetric determination of tea tannin with ferrous tartrate. Stud Tea 26:87–91

Kawakami T, Galli SJ (2002) Regulation of mast-cell and basophil function and survival by IgE. Nat Rev Immunol 2:773–786

Kimura M, Umegaki K, Kasuya Y, Sugisawa A, Higuchi M (2002) The relation between single/double or repeated tea catechin ingestions and plasma antioxidant activity in humans. Eur J Clin Nutr 56:1186–1193

Kinet JP (1999) The high-affinity IgE receptor (Fc epsilon RI): from physiology to pathology. Annu Rev Immunol 17:931–972

Kuroda Y, Hara Y (1999) Antimutagenic and anticarcinogenic activity of tea polyphenols. Mutat Res 436:69–97

Lambert JD, Yang CS (2003) Cancer chemopreventive activity and bioavailability of tea and tea polyphenols. Mutat Res 523:201–208

Lin JK, Liang YC, Lin-Shiau SY (1999) Cancer chemoprevention by tea polyphenols through mitotic signal transduction blockade. Biochem Pharmacol 58:911–915

Maeda-Yamamoto M, Kawahara H, Matsuda N, Nesumi K, Sano M, Tsuji K, Kawakami Y, Kawakami T (1998) Effects of tea infusions of various varieties or different manufacturing types on inhibition of mouse mast cell activation. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 62:2277–2279

Maeda-Yamamoto M, Kawahara H, Tahara N, Tsuji K, HaraY, Isemura M (1999) Effects of tea polyphenols on the invasion and matrix metalloproteinases activities of human fibrosarcoma HT1080 cells. J Agric Food Chem 47:2350–2354

Maeda-Yamamoto M, Sano M, Matsuda N, Miyase T, Kawamoto K, Suzuki N, Yoshimura M, Tachibana H, Hakamata K (2001) The change of epigallocatechin-3-O-(3-O-methyl) gallate contents in tea of different varieties, tea seasons of crop and processing method. J Jpn Food Sci Tech 48:64–68

Maeda-Yamamoto M, Suzuki N, Sawai Y, Miyase T, Sano M, Hashimoto-Ohta A, Isemura M (2003) Association of suppression of ERK phosphorylation by EGCG with the reduction of matrix metalloproteinase activities in human fibrosarcoma HT1080 cells. J Agric Food Chem 51:1858–1863

Maeda-Yamamoto M, Inagaki N, Kitaura J, Chikumoto T, Kawahara H, Kawakami Y, Sano M, Miyase T, Tachibana H, Nagai H, Kawakami T (2004) O-methylated catechins from tea leaves, inhibit multiple protein kinases in mast cells. J Immunol 172:4486–4492

Matsumoto N, Okushio K, Hara Y (1998) Effect of black tea polyphenols on plasma lipids in cholesterol-fed rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 44:337–342

Murase T, Nagasawa A, Suzuki J, Hase T, Tokimitsu I (2002) Beneficial effects of tea catechins on diet-induced obesity: stimulation of lipid catabolism in the liver. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 26:1459–1464

Okubo T, Ishihara N, Okura A, Serit M, Kim M, Yamamoto T, Mitsuoka T (1992) In vitro effects of tea polyphenols intake on human intestinal microflora and metabolism. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 56:588–591

Okuda T, Kimura Y, Yoshida T, Hatano T, Okuda H, Arichi S (1983) Studies on the activities of tannins and related compounds from medicinal plants and drugs. I. Inhibitory effects on lipid peroxidation in mitochondria and microsomes of liver. Chem Pharm Bull 32:1625–1631

Sakanaka S, Shiumua N, Masumi M, Kim M, Yamamoto T (1992) Preventive effect of green tea polyphenols against dental caries in conventional rats. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 56:592–594

Sano M, Suzuki M, Miyase T, Yoshino K, Maeda-Yamamoto M (1999) Novel antiallergic catechin derivatives isolated from oolong tea. J Agric Food Chem 47:1906–1910

Sazuka M, Murakami S, Isemura M, Satoh K, Nukiwa T (1995) Inhibitory effects of green tea infusion on in vitro invasion and in vivo metastasis of mouse lung carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett 98:27–31

Sazuka M, Imazawa H, Shoji Y, Mita T, Hara Y, Isemura M (1997) Inhibition of collagenases from mouse lung carcinoma cells by green tea catechins and black tea theaflavins. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 61:1504–1506

Suganuma M, Okabe S, Sueoka N, Sueoka E, Matsuyama S, Imai K, Nakachi K, Fujiki H (1999) Green tea and cancer chemoprevention. Mutat Res 428:339–344

Suzuki M, Yoshino K, Maeda-Yamamoto M, Miyase T, Sano M (2000) Inhibitory effects of tea catechins and O-methylated derivatives of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate on mouse Type-IV allergy. J Agric Food Chem 48:5649–5653

Tachibana H, Kubo T, Miyase T, Tanino S, Yoshimoto M, Sano M, Maeda-Yamamoto M, Yamada K (2001) Identification of an Inhibitor for interleukin 4-induced e germline transcription and antigen-specific IgE production in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 280:53–60

Thomson M, Al-Qattan KK, Al-Sawan SM, Alnaqeeb MA, Khan I, Ali M (2002) The use of ginger (Zingiber officinale Rosc.) as a potential anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic agent. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 67(6):475–478

Yokozawa T, Okura H, Sakanaka S, Ishigaki S, Kim M (1994) Depressor effect of tannin in green tea on rats with renal hypertension. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 58:855–858

Young HY, Luo YL, Cheng HY, Hsieh WC, Liao JC, Peng WH (2005) Analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities of [6]-gingerol. J Ethnopharmacol 96(1–2):207–210

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maeda-Yamamoto, M., Ema, K. & Shibuichi, I. In vitro and in vivo anti-allergic effects of ‘benifuuki’ green tea containing O-methylated catechin and ginger extract enhancement. Cytotechnology 55, 135–142 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10616-007-9112-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10616-007-9112-1