Abstract

Corruption is an undoubtedly a difficult conceptual area to operate in. This is particularly accurate for the post-Soviet space, where seemingly mutually exclusive forces appear to coexist on regular basis, defying and rejecting rational interpretations. Standard assumptions, definitions and theoretical perspectives often fail to generate useful understandings of corruption in Eastern Europe, habitually obscuring fundamental patterns, hence leaving corruption largely misunderstood. In order to construct anticorruption policies that would be effective in the environment where corruption is systemic, it is critical to resist the temptation of eschewing the complexity of societal factors by over-focusing on the corrupt individual. In an effort to reemphasize the imperative role played by societal variables in explaining corruption in the post-Soviet space, this article uses insights gathered from studying corruption in Republic of Moldova to discuss the role of three fundamental dynamics: “dirty hands,” the problem of “collective action” and the achromatic schema of white-gray-black corruption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

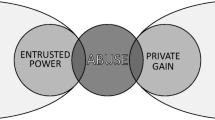

The literature on organizational misbehavior does not offer a conclusive answer to the debate of whether the decision to misbehave is primarily a function of individual personal traits or one’s social context [45]. In regards to corruption, which generally can be conceptualized as an act (or failure to act) as a result of receiving personal rewards from interested outside parties [14], recent works [4, 6, 7, 16, 45] have argued that neither individual nor social variables alone are able to provide satisfactory understandings of its nature. The tendency to reduce corruption to a problem of a few “bad apples,” although theoretically and methodologically appealing, often misses the thick implications of the pressures that stem from the power networks couched within the social matrix. The dynamics associated with the latter, however, play a serious role in understanding and explaining corruption within the context of fledgling democracies, such as those of Eastern EuropeFootnote 1 (see [2, 16, 25, 36]).

Corruption is undoubtedly a difficult conceptual area to operate in. This is particularly the case for discussions of public corruption with the post-Soviet space, where seemingly mutually exclusive forces appear to coexist on regular basis, often defying and escaping rational interpretations. Standard assumptions, definitions and theoretical perspectives regularly fail in terms of constructing practical understandings of the systematic nature of corruption in Eastern Europe; they habitually obscure fundamental patterns, hence leaving corruption largely misunderstood.Footnote 2 In order to construct anticorruption policies that would be effective in environments where corruption is systemic, it becomes critical to resist the temptation of eschewing the complexity of societal factors by over-focusing on the corrupt individual. While, introducing societal variables in the discussion of corruption makes for a much messier argument, still, as it is suggested in this article, any attempt to explain corruption within the post-Soviet space at the individual level alone will provide few, if any, satisfactory answers. In this vein, in an effort to re-emphasize the imperative role played by societal variables in explaining corruption in Eastern Europe, this article uses insights from original research on corruption in Republic of Moldova (hereafter “Moldova”), as well as from other recent empirical studies and theoretical discussions, to explore the role of three fundamental dynamics: “dirty hands,” the problem of “collective action” and the achromatic schema of white-gray-black corruption. Albeit Moldova represents only a single case, given that Eastern European countries share a common Soviet past and given that the nature of corruption within their territories exhibits sensible similarities [16, 25], there are important lessons that can be drawn from understandings developed from the Moldovan experience. In a sense, this article should be interpreted as a case driven theoretical discussion.

Beyond this introduction, the article is organized within six interdependent sections. The first section discusses the details that have inspired this writing. The following three sections, drawing heavily on insights gathered from the Moldovan case, examine corruption in Eastern Europe within the frames offered by the concepts of dirty hands, collective action and white, gray and black corruption, respectively. The principal suggestion made within the space of these three sections is that any anticorruption policies targeting a post-Soviet milieu that do not account at least in part for the three broad dynamics mentioned above will be incomplete at best, and will almost certainly a fail in long run. The article will conclude with two short sections that will delineate the role played by societal variables in terms of designing practical and effective anticorruption policies.

The paradox of “clean” Moldovan public officials

In an attempt to examine the nature of public corruption in Eastern Europe, Roman and Miller [36] replicated the methodological approach suggested by de Graaf and Huberts [7] in studying 28 MoldovanFootnote 3 public corruption cases. Each case was analyzed in-depth based on the information that was drawn from the suspect’s file (e.g. interrogation record, official statements) and other publically available data on the case. The underlying purpose of the research was to delineate the nature of corruption in Moldova. The reviewed cases were from the period from 2003 to 2009. All cases were closed based on receiving final decisions from the Supreme Court of Justice. While the studied sample was one of convenience, given the nature of the focus of the analysis, it is believed that the results were not meaningfully influenced by the case selection.

In addition to the in-depth multiple case analysis, the authors also conducted 33 semi-structured interviews with Moldovan knowledgeable informants (public officials, journalists, business owners, and with both former and current anticorruption employees). One fully unexpected, yet powerfully intriguing, revelation of the study was associated with the fact that all of the informants, including the interviewed public servants, have admitted that throughout their careers they have at least once paid a bribe or made use of a network of association or office for personal gain. Yet, none of the informants would have categorized themselves as being corrupt. On the contrary, they argued that accepting or paying bribes, even on regular basis, does not make one corrupt. Every so often, according to what was gathered during the interviews, even morally commendable administrative actions demanded operationalization within the frame of corrupt networks and practices. In the words of one of the informants:

It really doesn’t matter what you need the favor for. It could even be for a good deed. You still have to pay someone or owe them a favor. Nothing gets done in time without appropriate encouragement…a reason to get it done right, so to speak. To get things done right you have to be able to offer something in return. For example, if you want to donate to a kindergarten - let’s say some toys, yes? You’ll have to pay to make sure that they get to the kids. Otherwise, they’ll just sell the toys. The kids will get zilch. You have to work with the system. The system doesn’t care what you want to do….good…bad…or whatever. You have to give the process its dues. Essentially, you don’t have a choice. Getting things done….anything …requires money or relations; most of the time it’s both.

We could unreflectively continue to assume that corruption is “bad” and label it as a misbehavior that is at the discretion of the individual. But as the above statement elegantly captures, there would be a lot that such approach would miss. It becomes easily apparent that there is much more to corruption in countries without experienced democratic institutions such as Moldova than bribes. Although precariously thin and fickle, within the habitus of homo post-Sovieticus there exists a well-constructed understanding of operational necessity of corruption. Normative condemnations, which otherwise would be logical from the perspective of established democracies, are certainly not at home in the discussions of the nature of corruption and its evolutions within the postcommunist bloc. The understandings constructed from studying corruption in Moldova would suggest that corruption in Eastern Europe does not (perhaps, no yet) lend itself to a “bad-good” dichotomization; matters are unquestionably much more complex than that.

In what follows, insights from the interviews conducted during the Moldovan study will be used to examine the practical and theoretical challenges associated with understanding corrupt behavior within the Eastern European environments. Particular attention will be paid to the inherent entangled nature of corruption and the habitually failures of “one-size-fits-all,” principal-agent theory inspired, anticorruption policies. It is important to note that the core arguments presented here are assembled based on the findings that resulted from studying corruption in Moldova. Even though all the generalizations to Eastern Europe are justifiable by being based on other extant research, their acceptance still should be scrutinized under the auspices of typical academic caution.

Serving the public or getting your hands dirty

In modern times the dilemma appears most often as the problem of “dirty hands,” and it is typically stated by the Communist leader Hoerderer in Sartre’s play of that name: “I have dirty hands right up to the elbows. I’ve plunged them in filth and blood. Do you think you can govern innocently?… For sometimes it is right to try to succeed, and then it must also be right to get one’s hands dirty. But one’s hands get dirty form doing what it is wrong to do. ([46], pp. 161–164)

In simple terms the dilemma of dirty hands refers to the situation when one is facing the choice between two actions that would both be morally wrong to undertake. One would end up with dirty hands when reaching a certain social status or undertaking a given action, which might be appropriate from a moral reference, calls for approaches or behaviors that are morally unacceptable. This, unfortunately, is not solely a theoretical or philosophical question. It is a very real dilemma that elected officials and public servants face quite regularly, perhaps much more often than it is commonly believed or otherwise suggested by empirical literature.Footnote 4

In the context of Eastern Europe, even if we leave aside for a moment the question of whether a public official who has at one point in time undertaken corrupt acts could eventually do the “right” things in terms of administration, we are still faced with the troubling challenge of how to reach the point when corrupt acts are no longer “normal.” For considering that it is habitual for post-Soviet cultures to identify corruption as necessary [11, 16, 21, 36], whether corruption can ever become “unnecessary” appears to be a question that would logical precede any discussion of dirty hands. It has been suggested elsewhere that within post-Soviet space many of the public officials who eventually behave corruptly came in into their positions with the expectations that such behavior is associated with holding office [8, 16, 36]. The holder of the office assumes its “ownership” and hence the “right” to use the office as one finds fit, where fit more often than not is equated with personal interest. Public office is consistently captured for the unambiguous purpose of manipulation. Within the moral framework of the office holder, the public interest helplessly collapses into private interest. More importantly, however, is the fact that in order to move up the promotion ladder or to assume an administrative position of any serious importance in the first place - one needs to call upon favors from extant power networks. Yet, many of these favors would be in themselves, by their nature, nothing short of corrupt acts. In essence, then, conventional wisdom would suggest that it would be rather difficult for any high ranking Eastern European public servant, regardless of end intentions, to operate or come into office without setting oneself up for participation in a corrupt network. One of the Moldovan informants, a high ranking public official, acknowledged the reality of this dilemma when stating:

If you think about it, there is no way around it. To get anything done – you need to be someone. To become someone you have to know people or bribe your way up. When you get your position, you are expected to work within the accepted norms. That means that you have to share. So even if you would like to accomplish something that it is morally desirable or in the public’s interest – you would still have to play by the rules. If you don’t play by the rules…trust me…you will lose your job the next day. That’s just how it all works.

Following this logic it could be asserted that ironically “non-corrupt” public officials will have to make use of corrupt networks or approaches simply to assume desired office. What is of import for this discussion is the fact that, regardless of whether behaving corruptly to come into office “dirties” one’s hands or whether one can administrate innocently afterwards – there is a high probability that corruption becomes necessary for assuming office and for lasting public service career. In Moldova and other Eastern European countries with systemic public corruption, any office of consequential administrative value might simply be unreachable outside paths set within the frame of corrupt networks and understandings. This arrangement, certainly for many reasons, is resilient, self-reinforcing and highly likely to continue.

An administrator, who operates in a society that accepts corruption as a social norm and is guided by administrative structures which support corruption, hence making it methodical and perhaps even rational, might have to navigate corrupt networks for a mere “chance” to faithfully serve the public.Footnote 5 To some extent, it can be asserted that under these structural conditions public administrators have “no right” and perhaps few opportunities to keep their hands clean. Typically one simply cannot assume an important administrative role without dirtying one’s hands. It is rarely a problem of “availability,” since in most of Eastern Europe the majority of administrative or legislative positions, including parliamentary seats, are “available” for the right price (see [16, 26]). This was confirmed by one of the informants to be the case for Moldova as well:

Everything is for sale. If you know the right people, you can buy anything you want. You can by a judge, a cop, a news story or even a law. If there is someone you don’t like – you can easily acquire a fabricated compromising file. People and positions are all for sale and it is not like nobody knows about it. Everything has its price. The price changes, but it is always known. You don’t have to be a detective to know that… You can get any position you want if you have the money for it.

Once it becomes clear that in Eastern Europe corrupt behavior might become inescapable for purposes of public service the moral question then becomes whether a non-corrupt public servant with dirty hands is in any way “better” than a corrupt one. Even if our moral compasses might diverge here we should remember that the former supposedly engaged in corruption in pursuit of public interest, the latter, however, is corrupt because of a number of motives, with public interest surely not being one of them. In highly corrupt systems, there are many who wait ready to embrace corruption for personal interests or the interests of one’s network; it wouldn’t be much of an exaggeration, then, to argue that public servants, who would like to serve the public, might have to be similarly fitting in their approach or else stand to lose office. What becomes dishearteningly clear, nonetheless, is the fact that any effective anticorruption action, would paradoxically have to rely at the outset on corrupt public officials who are familiar with and can navigate the established corrupt networks.

The problem of “collective action”

Scores of scholars have supported the argument that in post-Soviet Europe the nature of corruption should be understood within the context of a country’s cultural, historical and societal environments ([16, 20–22, 24, 25, 35, 36]). Technical-instrumental, principal-agent driven perspectives are too precise in their foci on the individual, which leads them to miss critical aspects the nature of corruption in systemically corrupt countries [5, 27, 32]. Should a rational lens be employed, it is perhaps more appropriate to delineate corruption in Eastern European countries such as Moldova as a collective action challenge. In broad terms, a collective action problem can be framed as a condition in which no individual will undertake a given action (e.g. reject to profit from corruption), even if such strategy would benefit everyone, since individual cost of such action will be too high (see [30]).

Interpreting corruption from a collective action theoretical perspective would allow delineating the occurrence of corruption as direct outcome of the number of individuals who are standing ready to become corrupt. Given that in Eastern Europe corruption is not only accepted, but in large part expected [2, 11, 16], it would be erroneous to presume that there will be sufficiently many public officials or citizens to enforce and demand non-corrupt behavior in order to motivate genuine change in the short run. The citizens and social structures that condemn corruption on regular basis represent the very same structural matrices that will actively support and participate in corrupt networks when such behaviors are convenient or of interest.

A historical habit of corruption has led to the fact that the majority of citizenry in Eastern Europe are what Miller et al. [25] call “corruptible”; on the one hand, they denounce corruption, on the other hand, they keep themselves in position and apt to engage into corrupt acts should a favorable opportunity arise. As Miller et al. [25] expressively described it - citizens of postcommunist states are simultaneously victims and accomplices. “The system makes people complicit in their own demoralization and their own corruption” ([22], p. 732). Indeed, the social legitimacy of corruption appears to be one of the core legacies of communist systems and citizens are oppressed by their own habits. In the case of Moldova, one of the respondents emotionally captures this condition when stating:

Would you really turn down something if it meant that you and yours can get ahead? No matter what you might say to my face, I guarantee that you will take it. It is in our national makeup. You will certainly do it, since you know that if you don’t do it, then your neighbor or someone else will gladly do it. There is always someone who will do it. It has been like this for as long as I can remember and I am pretty sure it will never change.

Eastern European citizens often appear to have resigned to the idea that change is neither possible nor forthcoming. Given the ordinariness of corrupt behavior in postcommunist societies, being honest simply does not “pay” [16]. Furthermore, as another Moldovan informant suggested, turning down an opportunity to benefit from corruption is not only a losing proposition, but is also socially ridiculed.

Here [Moldova] being honest is the same as being stupid. Unless you are a complete idiot, you’ll quickly realize that in the real world nobody cares about your honesty. You can stick to your integrity and continue to be nobody for as long as you want.

The persistent sentiments of renunciation, cynicism regarding the possibility of change and the uncertainty about the future have led to what could perhaps be deemed as a “predatory opportunism” – a vigorous and committed search for opportunities to engage in corrupt acts. Entrepreneurship is routinely defined in terms of one’s ability to “beat the system.” Both citizens and public servants are actively searching, out of personal and social reasons, for prospects to draw unwarranted benefits. In the words of another Moldovan informant:

Everyone tries to get ahead any way they can. Everyone is looking for a way they can get something out of the system. One of my college buddies got a job with the economic police the other year. It cost him 3,000 Euros. Within a year he got all his money back and made enough for a car…The last time I saw him he was very nervous. He wasn’t sure whether he would still have a job after the elections. He was stressing because he needed a couple of big scores in case he might lose his job, but his team didn’t really have anything lined up. They had nobody left to shake.

An ingrained trait or postcommunist cultures is that what, when, who and how things get done is an outcome of unwritten rules and intertwined and seamlessly interdepend networks of association. Once one accepts one’s role within a given community or network one also accepts the obligations that come with such associations [36]. With time, questions of whether it should be done or not are not even asked; the single predicament of the day is how much can be skimmed. This condition is perceived as a bona fide construct of administrative processes. Ledeneva [22] vividly describes these post-Soviet residues by referring to them as “the open secrets of knowing smiles.” In postcommunist countries, legislative mandates are only a minor part of the rule structures that guide administrative interactions and decisions. Soviet habits and norms are deeply entrenched within the social matrix and have by no means become irrelevant just because communist regimes have stopped existing formally. Clientelist power and “blat”Footnote 6 networks have adapted and transitioned cleanly into the new democratic contexts.

[T]he ability of the rule of law to function coherently has been diverted by a powerful set of practices that has evolved organically in the post-Soviet milieu. An immediate grasp of the gap between the way things are claimed to be and the ways things are in practice constitutes an advantage enjoyed by an insider over outsiders, much more reliant on written sources of competence. The unwritten rules are non-verbal yet essential in understanding the order of things, whether in politics, economy, or society. ([22], p. 721)

White, gray and black: corruption and its multiple shades

Heidenheimer [13] argues that the concept of corruption has become especially ambiguous since the “melting away of the Cold War.” What corruption is and whether it is condemned is often a function of local preferences. Something that might be acceptable for community, or “white corruption,” could be demonized and persecuted as “black” corruption in others. Corruption’s color, although “sticky,” is by no means permanent. A large scale scandal, for instance, can repaint yesterday’s white corruption into black. To an extent, corruption is neither white nor black; it might take on vague shades of grey. Heidenheimer [13] suggests that even the achromatic black-grey-white schema, might not be sufficient as corruption could take on many other colors or degrees of brightness.

And while the shades of corruption have received ample attention within the extant literature, the dynamics behind the “brushes” have attracted significantly less attention. Corruption by its nature might not have a predetermined color. Its color hinges on the light shed by societal variables. Delineating certain behaviors as black corruption within the framework of legislative mandates would do little in terms of color infusion, if socially such behaviors are accepted and supported. The perspective provided by one of the Moldovan informants is a case in point:

At times very is nothing wrong with paying a bribe. Let’s take for example the case when you get stopped for speeding. It is in your own interest to take care of things on the spot. If procedures are enforced, it will cost you much more time and money in the end. It is too much hustle and too expensive. Why not pay a little bribe on the spot? You get on your way and the officer just got a little richer. You are happy and he is happy. The process is too slow and it doesn’t work. I don’t think there is too much wrong with this…at least not in this case.

Corruption is not everywhere the same, nor is a bribe everywhere a bribe. What constitutes a clear cut bribe in the Western world can indeed turn out to be a harmless gift or show of appreciation in other cultures [12, 37]. Within the Eastern European context, some of the more consequential corrupt acts, even if essentially financially or power related, might never involve a bribe [26]. In other instances, a bribe is nothing more that the acquisition of the right to be treated equally within the sequence of social influences.

Influence, not money, is the main currency, and the benefits to and individual anywhere in the chain are hard to measure: Favors are distributed or denied as part of a customary exchange with rules of its own, sometimes not involving direct personal gain for the “gatekeeper.” Bribery often occurs as a means of circumventing inequality: for the many people with lower status, bribing an official may be the only way to secure equal treatment ([26], p. 88).

The ambivalence towards corruption of citizens of post-Soviet societies is well documented [2, 11, 16]. Individuals will condemn most forms of corruption as long as there is no direct benefit they could draw from it. Nonetheless, at the first prolific opportunity to gain the system, corruption is no longer interpreted as bad. Perceptions of corruption are driven by a detached individualism – it’s seen as bad only if it directly hurts one’s wellbeing. As such, it can be concluded that there is limited stability in the shade that citizens in postcommunist countries attribute to corruption. Whether corruption is seen as white, gray or black is the outcome of a fragile and fluctuating interdependency between societal variables, which most often are conditioned by unreliable and flimsy collective memories and interpretations. One of the Moldovan informants stated the following:

People have to do it. How will they otherwise survive? For example, school teachers, even doctors, they get paid very little. They cannot survive on that. Is it really that catastrophic when they take a little extra? I don’t think so…Overall, it’s not that simple. Things are bad when they get out of hand. Let’s say, if they would sell school assets, but otherwise that’s just someone who wants to make a living. You cannot blame someone for wanting to protect and favor one’s friends and family. I, for one, wouldn’t be where I am now if I wouldn’t have pulled some strings in the past. Does this make me corrupt? Of course not….Everyone does it. Anyone who tells you anything different is lying to you… You cannot say that someone is corrupt only because he got a little money on the side or took a gift. Sometimes it’s different. When you don’t have a choice it shouldn’t count. Not all corruption is corruption. I am definitely not corrupt, but sometimes I have to do what I have to do, it is not really my choice. Do I want to do it? No. But this is our culture.

Discussion

Fighting corruption has in recent years become a “major industry” [26]. Despite the latest spike in awareness and the growing number of anticorruption efforts, there has been little progress and few, if any, notable successes within the countries that suffer from systemic corruption. Some have even argued that in spite of the coordinated international anticorruption support, in many instances matters have actually gotten worse, [15, 19, 23, 40, 35]. In fact, Kotkin and Sajo [18] contended that postcommunist administrations make a habit of generating ambitious and ambiguous anticorruption legislature to provide cover for otherwise rotten regimes. The adoption of legislative anticorruption mandates in Eastern Europe can rarely be taken at face value and interpreted as authentic signs of improvement.

In part due to the lackluster anticorruption track record, identifying effective strategies for addressing public corruption in systemically corrupt countries has been delineated as a top priority of international policies [26]. Ledeneva [20], Persson et al. [32] and Roman [35] have suggested that one of the chief reasons for the minimal impacts of the latest anticorruption reforms in countries, which have historically been highly corrupt, lies within the theoretical misunderstanding of the organized nature of public corruption. De Graaf [6] asserted that many empirical studies of corruption lack contingency and the direction of the proposed solutions is more often than not nothing more than a reaction to the theoretical model employed by the researcher. Along similar lines, Ledeneva [20] argued that “a de-historicized notion of corruption is unusable in postcommunist societies”; for such interpretation to be even remotely applicable, postcommunist societies need to have administrative habits that at least faintly resemble Weber’s ideal type. The latter is obviously rarely the case. Corruption in postcommunist countries, as clearly exemplified here by the Moldovan experience, cannot be understood or contained outside a culturally framed approach [16]. Taken together, there are many significant points of disagreement between preferred theoretical assumptions within current anticorruption policy designs and reality in the field. Anticorruption initiatives often fail in postcommunist countries primarily because what is labeled as corruption -

…is not the same phenomenon as corruption in developed countries. In the latter, the term corruption usually designates individual cases of infringement of the norm of integrity. In the former, corruption actually means “particularism” – a mode of social organization characterized by the regular distribution of public goods on a nonuniversalistic basis that mirrors the vicious distribution of power within such societies…anticorruption strategies are adopted and implemented in cooperation with the very predators who control the government and, in some cases, the anticorruption instruments themselves. ([26], pp. 86–87, original emphasis)

The nature of a collective action problem, which can be located at the core of corruption in Eastern Europe, is importantly different from principal-agent logic. As a result, within highly corrupt environments such as Moldova, solutions constructed on the principal-agent framework are more likely to be successful by chance than by design. Off-the-shelf, instrumental-rational anticorruption policies are simply unable to handle the inherent complexity of corruption in post-Soviet bloc. Within these environments, the lines between principals and agents are highly blurred or perhaps even non-existent. Above all, however, neither the agent nor the principal might have an interest in behaving non-corruptly [15, 11, 32]. This is what scholars [3, 31, 32, 39] describe as a collective action problem of the “second order.” Every citizen might understand and accept that doing away with corruption will lead to large common benefits; yet, since it is strategically beneficial to engage in corruption and there is no trust that anyone will resist corruption, there is no individual incentive to behave any differently [3, 38]. Without a “critical mass” of non-corrupt citizenry, willing to take a firm stand, it becomes difficult to break the vicious cycle of public corruption [27]. Consequently, anticorruption efforts should perhaps make it a priority to identify and nurture a critical mass of citizens, who would determinedly and actively reject corruption.

If recent failures of anticorruption policies have taught us anything, it is that societal variables cannot be overlooked and corruption cannot be solved through legislative restructurings. Strong legal anticorruption frameworks consistently fail to lead to any genuine change; in fact, such frameworks might create new opportunities and trigger increases in corruption [1, 41] or become the backbone of corrupt networks that they attempted to address in the first place [26]. It has been argued that institutional structures cannot account neither for the roots nor the solutions to public corruption [44]. In the post-Soviet space newly established institutions and supposedly rigorous democratic processes are regularly nothing more than Potemkin-village-type procedural decoys designed to satisfy domestic or international appearances, with real decisions being made elsewhere. By continuing to choose the elegant simplicity of principal-agent perspectives when constructing anticorruption approaches, we continue to insure, as it were, that the nature of Eastern European corruption remains in large part misunderstood, hence unaddressed.

In postcommunist societies, with no real stability in administrative structures, being part of administration could often be an adventure even for experienced and seemingly inconsequential street-level administrators. With every change in regime comes a change of staff or at least in loyalties. In such environments, there is neither patience nor room for traditional approaches in achieving change for “good” or in serving public interest. If any meaningful change should be achieved, paradoxically, corrupt public officials will unavoidably need to become central participants within the early part of the process.

Taking the liberty of firmly looking on the hopeful side, it could be argued that authentic change is still possible. At least that is what the Georgian experience would suggest. There was nothing pretty about Georgia’s recent anticorruption efforts, but current results are sufficiently robust to warrant feeling cautiously optimistic that corruption in postcommunist countries can be brought under control. In under a decade, Georgia went from one of the most corrupt post-Soviet countries to being ranked by Transparency International as being considered less corrupt than Czech Republic, Latvia, Slovakia, Romania and Bulgaria [43].Footnote 7 International observers have noted the Georgian transformation as nothing short of impressive ([10, 29, 42, 47]). Although, there is little to go off besides anecdotal evidence and reports of nongovernmental organizations, the scarce empirical accounts that are available all point in agreement in the same positive direction. But, then again, there are many things about Georgia’s historical and social makeup, which when considered in aggregate, make Georgia significantly different from most nations in the post-Soviet space. Of particular interest here is Georgia’s affinity for the West, its strong cultural identity and its long history of survival despite continuous attacks from external forces [34]. As it is always the case, it would be dangerously misleading to draw decisive conclusions just on one circumstance. Nevertheless, it may be worthwhile to take an attentive look at this hopeful success story. There surely are useful empirical insights to be garnered from an in-depth exploration of such an incredible transformation.

Conclusion

This article started with the argument that the nature of corruption in postcommunist societies is a particular complex socially-dependent construct; useful understandings of the nature of corruption cannot realistically be constructed without serious consideration of societal variables. To this end, it used the insights obtained from studying corruption in Moldova to suggest that without incorporating the ideas of dirty hands, collective action and white-grey-black corruption – most theoretical discussions on corruption in Eastern Europe would be unrepresentative or limiting at best. At first, it might seem axiomatic that the three concepts discussed here are critical for understanding corruption in Eastern Europe. After all, it is evident that all societal variables considered here condition, under one form or another, the context within which corruption currently thrives. In addition, given Eastern Europe’s common communist past, it might not be too much of an exaggeration to weave common threads through the evolution of corruption within its space. The analysis in this article shows, however, that the interaction of these societal variables builds a powerful self-strengthening and difficult to penetrate veil of habits. In a certain way, in a world of constant change and uncertainty, corrupt associations develop into widely accepted and easily accessible sense making mechanisms. Therefore, when dealing with corrupt behavior in the post-Soviet space, which is heavily weltered in corruption, we simply cannot handicap our understandings by taking for granted the legitimacy of rational perspectives. A deeper reflection might provide sufficient grounds to seriously reconsider the blasé associations between engaging in corrupt behavior and being corrupt. For established democracies the correlation between the two is indeed high and perhaps rather clear; in Eastern European societies “behaving” corruptly and “being” corrupt might differ in a few, but critically significant ways.

Nowadays corruption is ubiquitous in the myriad of transactions in the political, economic and cultural sphere, in private transactions large and small, and at the highest and lowest levels of the governmental and social hierarchy. Many corruption cases become public knowledge. Everyone is angry, and –often unwillingly – many people get dirty. It is almost impossible to avoid becoming involved in some transaction where one or another of the parties engages in certain shady tractions, and where the client, the citizen, the seller or the buyer, would not attempt to bribe, or be involved in a phoney tax-evasion scheme of some sort ([17], p. 232).

We are far too easily and too often attracted to the idea of attaching moral labels to corruption in Eastern Europe. As the Moldovan case might suggest, there are, however, many important reasons to resist such hast over-simplifications; among the more important ones is that operating within corrupt networks is frequently the only means of getting anything done. Assuming that the Eastern European public administrators stand alone in their decisions to become corrupt makes for well-behaved empirical and theoretical discussions; yet, they rarely stand alone in their decisions. Societal values shaped by culture, kinship associations and network pressures provide a more complete and realistic evaluation of the nature of corrupt behavior by public servants in post-Soviet space. In their everyday social interactions, many Eastern European citizens and public servants are only ephemerally exposed to the idea of the need to rebuff all forms of corruption. It could be argued that in their milieus behaving non-corruptly is a behavioral deviation.

There is an explicit difference between corruption that undermines a legitimate democratic system and corruption that people feel forced to use in order to circumvent a repressive, dysfunctional, and illegitimate system…If citizens perceive that public institutions do not serve them, they themselves do less in terms of public service, paying taxes, and observing laws. A vicious circle can evolve where such popular attitudes lead to even worse government ([16], p. 93).

The conclusions reached here do indeed paint a bleak picture. There is a great deal of desperation that lies within the self-fulfilling condition of corruption in postcommunist societies. To be sure, it is unrealistic to ask whether corruption can be eradicated in Eastern Europe. The question is rather one of degree. For considering that corruption is a central part of the nature of post-Soviet habitus it is perhaps more appropriate to strive for “manageable” levels of corruption. This article, nevertheless, does not dare to conclude without supporting a concrete anticorruption effort, if for no other reason than that failure to suggest any solution appears to be the common weakness for most theoretical discussions on public corruption. Nonetheless, given that most, if not all, current, principal- agent-inspired anticorruption approaches failed miserably in the post-Soviet space - what, then, can be done? The literature appears to converge on one approach, which is also supported in this article, that of a shock to the system.Footnote 8 Scholars have recently begun to assert that piecemeal efforts will simply not work, what are needed are revolutionary-type sweeping changes ([26, 32]). The societal structures need to be shaken to the point where a critical mass of citizens who find corruption unacceptable is created. Social value structures have to be infused with sufficient levels of enthusiasm, belief and trust in order to break the historical cynicism and give institutional frameworks a fighting chance to start working as envisioned by design. The behavioral nature of the homo post-Sovieticus must make one first small, yet critically consequential, leap from corrupt to sporadically corruptible. Only at the point when a critical mass is established, it would be realistic to entrust the system to its own devices and expect it to self-correct and adapt to historical and social specificities.

Real change will become possible only in the case when behaving corruptly would no longer be believed to be the norm, would not necessarily pay (not even in the short run) and public servants would be able to access office without getting their hands dirty. It is indispensable, then, that social patterns of behavior become fraught with opportunities not to behave corruptly. The transformation of Georgia could provide a suitable starting point for learning how it can be done. As suggested by the European Commission [10], Georgia’s evolution is far from perfect, with many glaring concerns still in place; furthermore, there are no guarantees that Georgia’s progress is sustainable or whether it is even authentic. There are currently, however, few better learning options and for all its contextual peculiarities the answers to generating effective corruption management solutions for the post-Soviet space might indeed lie in the Georgian experience.

Although the discussion in this article focused on post-Soviet societies, its utility should not stop there. Recent literature on corruption in established democracies (e.g. [6, 33]) suggests that it is no longer appropriate to make the assumption that corruption is driven by “bad apples” and corrupt behavior is necessarily an exception or deviation. Corruption should conceivably be seen as a nearly universal and permanent concern [28, 33], including established democracies, which otherwise are habitually perceived, most of the time simply out of good faith, as having low levels of corruption. As such, there are many important lessons that anticorruption efforts in established democracies could learn from failures of the postcommunist experiences; not the least important being that anticorruption institutional frameworks are much less robust than ordinarily assumed. In order to understand and explain public corruption, in the East or the West, societal variables and contexts might be more important than we are currently comfortable to appreciate.

Notes

For the purposes of this paper “Eastern Europe” is understood as the European “bloc” of the former Soviet space.

See Ledeneva [20] for a well-articulated critique of the assumptions, preconceptions and methodology of the “corruption paradigm.”

The Republic of Moldova is often perceived to be one of the most corrupt countries in Europe. For instance, its Corruption Perception Index score for 2012 was 36 [43]. The score represents an estimate of the perceived level of public sector corruption on a scale of 0 to 100, where 0 stands for highly corrupt and 100 stands for not-corrupt. According to the European Commission [9] corruption remains a very serious concern for all levels of government in Moldova.

Curiously, public administration literature has dedicated little attention to this issue. There is something “inherently uncomfortable” about the admission that administrative action demands or at least is associated with opportunities to dirty one’s hands.

That is assuming that that one originally intended to and after assuming office still can or is willing to serve the public, which is obviously a rather naïve hope.

Informal exchanges of benefits (e.g. goods, jobs) using personal and kinship networks that go around formal procedural structures.

All concerns regarding the shortcomings of perception-based rankings and indexes are still in order here; yet, they are not central to the purpose of this comparison.

For instance changing “overnight” all traffic officers or the staff of a knowingly corrupt agency or department (an approach apparently favored by Georgia).

References

Bäck, H., & Hadenius, A. (2008). Democracy and state capacity: exploring a J-shaped relationship. Governance An International Journal of Policy Administration and Institutions, 21(1), 1–24.

Barsukova, S. (2009). Corruption. Russian Politics and Law, 47(4), 8–27.

Bates, R. H. (1988). Toward a political economy of development: A rational choice perspective. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Brass, D., Butterfield, K. D., & Skaggs, B. C. (1998). Relationships and unethical behavior: a social network perspective. Academy of Management Review, 23(1), 14–31.

Bukovansky, M. (2006). The hollowness of anti-corruption discourse. Review of International Political Economy, 13(2), 181–209.

de Graaf, G. (2007). Causes of corruption: towards a contextual theory of corruption. Public Administration Quarterly, 31(1), 39–86.

de Graaf, G., & Huberts, L. W. J. C. (2008). Portraying the nature of corruption using an explorative case study design. Public Administration Review, 68(4), 640–653.

Djilas, M. (1957/1985). The new class: An analysis of the communist system. New York, NY: A Harvest/HBJ.

European Commission (2013a). Implementation of the European Neighbourhood Policy in Republic of Moldova: Progress in 2012 and recommendations for action. Joint Staff Working Document. Retrieved from the European Union website: http://ec.europa.eu/world/enp/docs/2012_enp_pack/progress_report_moldova_en.pdf

European Commission (2012). Implementation of the European Neighbourhood Policy in Georgia: Progress in 2011 and recommendations for action. Joint Staff Working Document. Retrieved from the European Union website: http://ec.europa.eu/world/enp/docs/2012_enp_pack/progress_report_georgia_en.pdf

Grødeland, A. (2010). Elite perceptions of anti-corruption efforts in Ukraine. Global Crime, 11(2), 237–260.

Hasty, J. (2005). The pleasures of corruption: desire and discipline in Ghanaian political culture. Cultural Anthropology, 20(2), 271–301.

Heidenheimer, A. J. (2004). Disjunctions between corruption and democracy? A qualitative exploration. Crime Law & Social Change, 42(1), 99–109.

Huberts, L. W. J. C., & Nelen, J. M. (2005). Corruptie in het Nederlandse openbaar bestuur: Omvang, aard en afdoening [Corruption in government in the Netherlands: Extent, nature and prosecution]. Utrecht: Lemma.

Johnston, M. (2005). Syndromes of corruption: Wealth, power, and democracy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Karklins, R. (2005). The system made me do it: Corruption in post-communist societies. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe.

Kornai, J. (2006). The great transformation of Central Eastern Europe: success and disappointment. Economics of Transition, 14(2), 207–244.

Kotkin, S., & Sajo, A. (Eds.). (2002). Political corruption in transition: A skeptic’s handbook. Budapest: Central European University Press.

Lawson, L. (2009). The politics of anti-corruption reform in Africa. Journal of Modern African Studies, 47(1), 73–100.

Ledeneva, A. (2009). Corruption in postcommunist societies in Europe: a re-examination. Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 10(1), 69–86.

Ledeneva, A. (2009). From Russia with blat: can informal networks help modernize Russia? Social Research, 76(1), 257–288.

Ledeneva, A. (2011). Open secrets and knowing smiles. East European Politics and Societies, 25(4), 720–736.

Meagher, P. (2005). Anti-corruption agencies: Rhetoric versus reality. Journal of Policy Reform, 8(1), 69–103.

Miller, W. L. (2006). Corruption and corruptibility. World Development, 34(2), 371–380.

Miller, W. L., Grødeland, Å. B., & Koshechkina, T. Y. (2001). A culture of corruption? Coping with government in post-communist Europe. Budapest: Central European University Press.

Mungiu-Pippidi, A. (2006). Corruption: diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Democracy, 17(3), 86–99.

Mungiu-Pippidi, A. (2013). Controlling corruption through collective action. Journal of Democracy, 24(1), 101–115.

Newburn, T. (1999). Understanding and preventing police corruption: Lessons from the literature. Police Research Series (110). London: Home Office.

OECD (2010). OECD anti-corruption network for Eastern Europe and Central Asia: Georgia monitoring report. Paris, France: OECD. Retrieved from OECD website: http://www.oecd.org/corruption/acn/istanbulactionplan/44997416.pdf

Olson, M. (1965). The logic of collective action: Public goods and theory of groups. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Ostrom, E. (1998). A behavioral approach to the rational choice theory of collective action. American Political Science Review, 92(1), 1–22.

Persson, A., Rothstein, B., & Teorell, J. (2012). Why anticorruption reforms fail – systemic corruption as a collective action problem. Governance: An International Journal of Policy, Administration, and Institutions.

Punch, M. (2000). Police corruption and its prevention. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 8(3), 301–324.

Rayfield, D. (2012). Edge of empires: A history of Georgia. London: Reaktion Books Ltd.

Roman, A. V. (2012). The Myths within anticorruption policies. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 34(2), 237–254.

Roman, A. V., & Miller, H. T. (2013). Building Social Cohesion: Family, Friends, and Corruption. Administration & Society.

Rose-Ackerman, S. (1999). Corruption and government: Causes, consequences, and reform. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rothstein, B. (2005). Social traps and the problem of trust. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rothstein, B. (2011). Anti-corruption: the indirect ‘big bang’ approach. Review of International Political Economy, 18(2), 228–250.

Svensson, J. (2005). Eight questions about corruption. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(3), 19–42.

Sung, H. (2004). Democracy and political corruption: a cross-national comparison. Crime Law & Social Change, 41(2), 179–194.

The Economist (2012). Georgia’s mental revolution: Seven years after the Rose revolution, Georgia has come a long way. Retrieved from The Economist website: http://www.economist.com/node/16847798

Transparency International (2012). Corruption perception index 2012. Retrieved from the Transparency International website: http://cpi.transparency.org/cpi2012/results/

Uslaner, E. M. (2008). Corruption, inequality, and the rule of law. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Vardi, Y., & Weitz, E. (2004). Misbehavior in organizations: Theory, research and management. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Walzer, M. (1973). Political action: the problem of dirty hands. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 2(2), 160–180.

World Bank. (2012). Fighting corruption in public services: Chronicling Georgia’s Reforms. Directions in development: Public sector governance (66449). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Roman, A. The multi-shade paradox of public corruption: the Moldovan case of dirty hands and collective action. Crime Law Soc Change 62, 65–80 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-014-9519-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-014-9519-5