Abstract

Beliefs regarding the toleration of frustration and discomfort are often described as underlying psychological disturbance, and represent a fundamental concept in Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT). Nevertheless, there has been little systematic analysis of the content of these beliefs, which are often treated as a unidimensional construct. This paper investigates the relationship between a multidimensional Frustration Discomfort Scale (FDS) and measures of depressed mood, anxiety, and anger, in a clinical population. Results indicated that FDS sub-scales were differentially related to specific emotions, independent of self-esteem and negative affect. The entitlement sub-scale was uniquely associated with anger, discomfort intolerance with depressed mood, and emotional intolerance with anxiety. These results supported the validity of the FDS, the importance of distinguishing between frustration intolerance dimensions, and of separating these beliefs from those related to self-worth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Frustration intolerance has a long history as an explanatory concept, playing an important role in both behavioral and cognitive models of emotional problems. In particular, Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT) has placed considerable emphasis on frustration intolerance as one of two fundamental categories of belief, the other being self-worth. These two categories of belief are considered as having separate and distinct relationships with individual problems (Ellis, 1979, 1980). Indeed, it is argued that frustration intolerance and self-worth reflect different underlying cognitive processes, although both are absolute evaluations (DiGiuseppe, 1996). Frustration intolerance is based on a refusal to accept the difference between desire and reality (e.g., “I can’t stand not getting what I want”). Whilst the other category reflects the belief that self-worth is dependent on meeting absolute conditions (e.g., “If I do not succeed, I am a failure”).

REBT theory suggests that psychological problems may derive from either category of belief. For example, depressed mood may be related to a sense of worthlessness, or the belief that life is intolerably difficult; anxiety to feared loss of approval or intolerance of anxiety; and anger to threatened self-worth or intolerance of frustration (Walen, DiGiuseppe, & Dryden, 1992). In terms of empirical evidence, both belief categories are reported to be related to depressed mood (McDermut, Haaga, & Bilek, 1997), consistent with the REBT hypothesis that two sub-types of depression exist. Similarly, different irrational beliefs are associated with specific anxiety problems (Deffenbacher, Zwemer, Whisman, Hill, & Sloan, 1986). As regards anger, frustration intolerance beliefs have remained relatively neglected, with more emphasis placed on issues of self-worth (e.g., Beck, 1999; Jones & Trower, 2004). Nevertheless, the evidence linking anger and low self-esteem is weak; although threatened high self-esteem has been proposed as an alternative (Baumeister, Smart, & Boden, 1996). Certainly, this would be consistent with the REBT position that both positive and negative global self-evaluation can be dysfunctional. However, other research has suggested a further hypothesis: that frustration intolerance, rather than self-worth, is the fundamental belief category related to anger (Martin & Dahlen, 2004).

Investigation of frustration intolerance beliefs, and their relative importance compared to self-worth, has been limited by difficulties in assessing irrational beliefs. Early scales were based on a simplistic model, and showed poor discriminative ability due to items referring to both emotions and cognitions. Later scales have suffered from the emphasis by REBT theory on the four belief processes (demands, self-worth, frustration intolerance, and awfulizing), rather than analysis of their belief content. The assumption that demands (e.g., “I must have approval” vs. “I would like approval”) are the central belief has also been questioned. For instance, self-worth and frustration intolerance beliefs, rather than demands, have been found to significantly predict anxiety and depression (Chang & D’Zurilla, 1996).

Whether or not demand beliefs are fundamental to psychological problems, all four belief processes are probably too generalized to allow specific predictions (Brown & Beck, 1989). Indeed, recent studies indicate that belief content may be of central importance in determining the type of emotional disturbance (Bond & Dryden, 2000). Such evidence suggests it would be more useful to separate and analyse these processes in more detail (Chadwick, Trower, & Dagnan, 1999; Dryden, 1999). Unfortunately, frustration intolerance has been largely treated as unidimensional, even though the REBT literature describes a wide range of beliefs as characteristic of this concept. Such beliefs include intolerance of injustice, discomfort, frustration, uncomfortable emotions, and uncertainty (Dryden, 1999; Dryden & Gordon, 1993). Furthermore, it is likely that these different content areas are related to distinct disorders. For instance, intolerance of uncertainty has been specifically linked to generalized anxiety (Dugas, Gagnon, Ladouceur, & Freeston, 1998). However, uncertainty may be associated with several areas of frustration intolerance, and the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (Buhr & Dugas, 2002) includes items referring to fairness, achievement, and emotional distress, as well as to self-worth. Similarly, whilst specific frustration intolerance beliefs have been found to be related to depression (McDermut et al., 1997) and anxiety (Deffenbacher et al., 1986), the lack of systematic analysis of these beliefs, and their factor structure, limits the conclusions that may be drawn.

To redress this, the Frustration Discomfort Scale (FDS) was developed as a multidimensional measure of frustration intolerance, and the reliability and factor structure investigated in two separate studies (Harrington, 2005a). The first study employed a more complex preliminary scale in which each item consisted of a demand statement (“I must...”) combined with a frustration intolerance statement (“I can’t stand it...”). However, subsequent research questioned the need for demands, suggesting items may be best worded simply in terms of frustration intolerance (Bond & Dryden, 2000). Therefore, the second study extended the content and simplified the item structure by employing only frustration intolerance statements. Analysis showed that both versions of the scale displayed good psychometric properties, discriminated between student and clinical groups, and supported construct validity (Harrington, 2005a, b).

Exploratory factor analysis indicated that frustration intolerance was best described by four factors, and this was supported by a confirmatory factor analysis in the second study. The factors were labeled: Emotional intolerance, discomfort intolerance, entitlement, and achievement. The emotional intolerance factor reflected the belief that thoughts and feelings associated with emotional distress were intolerable (e.g., “I can’t bear disturbing feelings”). These beliefs formed a separate factor from those relating to intolerance of general discomfort, effort or difficulty (e.g., “I can’t stand doing things that involve a lot of hassle”).

The entitlement factor represented the belief that other people should indulge and not frustrate our desires (e.g., “I can’t bear it if other people stand in the way of what I want”). Echoing REBT theory, Major (1994) suggests that entitlement can be distinguished from “related concepts like wants and expectations” by a sense of “moral imperative,” that is the belief that one should be treated in a certain way (p. 299). Similarly, Karen Horney (1950), who strongly influenced REBT theory, proposed that “demands” were more than just “needs” since they assumed an entitlement to have those needs met. Although from her perspective, entitlement is an aspect of all irrational demands, it can be argued that entitlement refers primarily to frustration regarding other people. The entitlement factor includes two facets, with items referring to intolerance of unfairness and delayed gratification.

The last factor reflected perfectionistic achievement beliefs. Importantly, perfectionism research has argued that high standards may only be dysfunctional when self-worth is contingent on achieving those standards (Alden, Ryder, & Mellings, 2002). However, existing measures of perfectionism do not clearly distinguish between perfectionism related to self-worth as opposed to intolerance of goal frustration. Therefore, the achievement sub-scale aimed to assess perfectionistic beliefs associated with frustration intolerance, separate from self-worth (e.g., “I can’t bear the frustration of not achieving my goals”).

The purpose of this paper was to present evidence regarding the validity of the revised FDS in relation to measures of emotion in a clinical population. Given that self-worth and frustration intolerance beliefs are expected to overlap (Ellis, 1980), it was necessary to demonstrate that the FDS sub-scales were related to specific emotions, independent of self-esteem or shared association with negative affect (Kendall et al., 1995). To achieve this, a regression strategy was employed, controlling for these two variables, and allowing the relative contribution of self-worth and frustration intolerance to be examined. In addition, the present study sought to replicate the findings of the preliminary scale study, which involved a similar population (Harrington, 2003). Preliminary results indicated that entitlement was a unique predictor of anger, discomfort intolerance of depressed mood, and emotional intolerance of anxiety, even when accounting for self-worth and negative affect. The present sample represented the clinical group included in the revised FDS confirmatory factor analysis (Harrington, 2005a), although none of the results presented in this paper have been previously reported.

Method

Participants

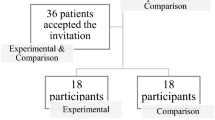

The sample was drawn from consecutive therapy referrals to an adult clinical psychology department. The response rate was 45%, leaving 254 FDS questionnaires for analysis (105 men and 149 women; mean age 37.35, SD = 12.36, range 17–74). Although detailed socio-economic data was not available, the sample was recruited from a diverse geographical and social area, including rural, industrial and university towns.

Problems were classified by the treating psychologist at the end of therapy, and represented a broad range of non-psychotic problems: 31% of clients had a primary classification of anxiety, 25% depression, 15% anger, with obsessional, addiction, marital/interpersonal, and eating disorders each representing approximately 5% of the sample. A previous analysis of referrals to the department indicated that mean scores on the Symptom Checklist 90 (Derogatis, 1994), a measure of overall symptom severity, had the same pattern as United States outpatient norms, but with higher global index scores (1.55 compared to 1.22) (Turvey, Humphreys, Smith, & Smeddle, 1998). This study also indicated that non-responders did not differ from responders on diagnostic or demographic characteristics.

Measures and procedure

The questionnaire package was included with notification of first appointment, and returned by stamped addressed envelope.

The Frustration Discomfort Scale (FDS; Harrington, 2005a) consists of 28 items, with four 7-item sub-scales: Discomfort intolerance, entitlement, emotional intolerance, and achievement. Apart from two items, all statements were worded only in terms of frustration intolerance. Individuals were asked to rate the strength of belief on a 5-point Likert-type scale with the following anchors: (1) absent, (2) mild, (3) moderate, (4) strong, (5) very strong. There was good evidence of reliability, with coefficient alphas for the respective sub-scales: .88, .85, .87, and .84.

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965) was chosen for its brevity and widespread use as a measure of global self-worth. It is scored on a 10-item Likert-type scale and has good internal reliability. Careful preliminary analysis and screening of “careless responses” was undertaken (Corwyn, 2000). Following elimination of spoilt responses, 248 Rosenberg Scale questionnaires were analyzed. The mean score was 24.31 (SD = 5.69), with high scores representing higher self-esteem.

The Trait Anger Scale (TAS; Spielberger, Jacobs, Russell, & Crane, 1983) is a 10-item scale with each item rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale. The TAS has internal reliabilities between .87 to .91 and extensive evidence of validity (Deffenbacher et al., 1996). The scale contains two facets: “angry temperament” measuring a general propensity to experience and express anger without specific provocation, and “angry reaction” measuring the predisposition to express anger when criticized or treated unfairly. Referrals for anger problems to a British forensic psychology outpatient service (McMurran et al., 2000) are reported as having a TAS mean score of 25.59 (SD = 7.78). Due to an administrative error, only 235 questionnaires were available for analysis.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD; Zigmond & Snaith, 1983) is a 14-item self-report rating scale, with two sub-scales each containing seven items measuring anxiety and depressive symptom. It has extensive reliability and validity data (Herrmann, 1997), with reported Cronbach’s α of .82 and .77 respectively, and a total scale of .86 (Crawford, Henry, Crombie, & Taylor, 2001). The HAD was initially developed to identify clinical levels of pathology using cut-points. However, recent British normative data enables the scale to be used as a continuous measure, consistent with the assumption that anxiety and depressed mood are dimensional constructs (Crawford et al., 2001). This research recommends sub-scale cut-points of 11 or more to identify moderate to severe “cases” of depression or anxiety. The HAD contains two features that make it useful in the present study. First, the depression sub-scale focuses on anhedonic symptoms, with no items referring to self-esteem. Secondly, the HAD contains no cognitive items, avoiding the problem of overlap between measures of emotions and beliefs.

Results

Preliminary and correlational analysis

A one-way (Gender) MANOVA across all measures indicated a significant multivariate gender effect, F(8, 221) = 2.77, P < .001. Significant univariate gender effects, with females reporting higher scores, were found for HAD anxiety, F(1, 228) = 5.02, P < .05 (Ms = 14.15 vs. 12.82) and emotional intolerance, F(1, 228) = 4.38, P < .05 (Ms = 26.31 vs. 24.47). Effect sizes (η squared = .022 and .026, respectively) were small (Cohen, 1988). Females also had lower self-esteem, F(1, 228) = 15.10, P < .001 (Ms = 23.05 vs. 25.91), representing a medium effect size (η squared = .062). Gender effects regarding entitlement (Ms = 21.74 vs. 22.36), discomfort intolerance (Ms = 20.63 vs. 19.8), achievement (Ms = 22.68 vs. 22.43), anger (Ms = 21.79 vs. 22.18), and depression (Ms = 9.78 vs. 9.00), were all non-significant.

Increased age was significantly related to lower anger (r = −.20, P < .01), entitlement (r = −.22, P < .001), emotional intolerance (r = −.14, P < .05), and higher self-esteem scores (r = .16, P < .01). The proportion of patients classified as above the clinical cut-points were: HAD anxiety (70%), HAD depression (34%), and TAS forensic anger referral mean (27%).

Intercorrelations between the FDS sub-scales were high (Table 1). Whilst this is consistent with a superordinate construct of frustration intolerance, the intercorrelations were not of a degree that would indicate unidimensionality (John & Benet-Martínez, 2000). In particular, the sub-scale intercorrelations were substantially lower than their respective reliabilities, suggesting that the dimensions of frustration intolerance can be discriminated as separate constructs.

Correlations between the FDS and the other measures, presented in Table 1, were substantially the same as in the preliminary scale study (Harrington, 2003). Consistent with REBT theory (Ellis, 1980), the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale and the FDS were moderately correlated. Self-esteem was most strongly associated with the discomfort and emotional intolerance sub-scales, possibly reflecting the role of these sub-scales as metacognitive beliefs secondary to problems of self-worth. The weakest relationship was between self-esteem and entitlement. It was also notable, that entitlement had the strongest correlation with anger, whilst self-esteem had the weakest. The specific relationship between high self-esteem and anger was also investigated by comparing top and bottom quartiles on the Rosenberg Scale. Patients with high self-esteem were found to have significantly lower anger scores, t(226) = 3.02, P < .01. Examining individual FDS items, the item with the strongest correlation with anger was ‘intolerance of criticism’ (“I can’t tolerate criticism especially when I know I’m right”), from the entitlement sub-scale (r = .43, P < .01). This is particularly relevant, since sensitivity to criticism has been described as a central characteristic of narcissistic personality disorder, and of anger arising from threats to self-worth (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). However, although intolerance of criticism was significantly related to anger, the item had a negligible relationship with self-worth (r = −.08, ns).

To test for differences between the correlations of the FDS sub-scales and the emotional measures, the Z statistic was computed (Meng, Rosenthal, & Rubin, 1992). Entitlement was more strongly related to anger than to either anxiety (Z = 4.01, P < .001) or depression (Z = 4.69, P < .001). Emotional intolerance was more strongly related to anxiety than depression (Z = 3.42, P < .001) or anger (Z = 3.70, P < .001). Discomfort intolerance was moderately correlated to both depression and anxiety (Z = 0.73, ns), but to a lesser degree with anger (Z = 1.97, P < .05). Achievement was moderately correlated to anxiety as well as anger (Z = 1.15, ns), but to a lower extent with depression (Z = 3.08, P < .001). When controlling for self-esteem and negative affect, the relationship of achievement with anxiety (pr = .28, P < .001) and anger (pr = .28, P < .001) remained significant, but not with depression (pr = .04, ns).

Regression analyses

To examine the unique relationship of the FDS sub-scales with each emotion, and to control for self-esteem and negative affect, a series of hierarchical multiple regressions were conducted. In the first regression, gender, age (anger only), self-esteem, and negative affect (HAD[total] for anger; HAD[anx] for depression; HAD[dep] for anxiety), were entered on step 1. The FDS sub-scales were entered on step 2. Two further hierarchical regressions were conducted to enable a comparison, in terms of the unique variance explained, between significant FDS sub-scales and self-worth. Thus, self-esteem was entered on step 1, and predictive FDS sub-scales on step 2. In the final regression, this order of entry was reversed.

Anger

Self-esteem was not found to be significant on step 1 (t = .80, P = .43, ß = −.06). On step 2, the FDS block was significant, R² = .35, ΔR² = .20, F(4, 201) = 15.09, P < .001, accounting for a substantial proportion (20%) of the remaining variance (large effect size). Of the FDS sub-scales, only entitlement proved to be a unique predictor of trait anger (t = 6.55, P < .001, ß = .53). In the second regression, with self-esteem entered on step 1, R = .22, R² = .05, F(1, 228) = 11.31, P < .001, entitlement accounted for 31% of the remaining variance on step 2, R = .55, R² = .31, ΔR² = .26, F(1, 227) = 84.15, P < .001. In contrast, self-esteem accounted for only 1% of variance when the order of entry was reversed, ΔR² = .01, F(1, 227) = 3.29, ns.

Anxiety

Self-esteem was significant on step 1 (t = 3.39, P < .001, ß = −.21) and the FDS block on step 2, R² = 48, ΔR² = .14, F(4, 240) = 16.37, P = <.001, accounting for 14% of additional variance (large effect size). Emotional intolerance was the only unique predictor of anxiety on step 2 (t = 6.38, P < .001, ß = .45), self-esteem having failed to remain significant (t = 1.01, P = .314, ß = −.06). In the second regression, self-esteem accounted for 18% of the variance on step 1, R = .43, R² = .18, F(1, 246) = 54.41, P < .001, and the emotional intolerance sub-scale accounted for 21% of remaining variance on step 2, R = .63, R² = .39, ΔR² = .21, F(1, 245) = 83.30, P < .001. Reversing the order of entry, emotional intolerance explained 37% of the variance on step 1, R = .61, R² = .37, F(1, 246) = 144.95, P < .001, whilst the variance explained by self-esteem fell to 2% on step 2, ΔR² = .02, F(1, 245) = 8.81, P < .01.

Depression

Self-esteem was a significant predictor of depression on step 1 (t = 5.22, P < .001, ß = −.30) and remained so on step 2 (t = 3.93, P < .001, ß = −.24). The FDS block was significant, R = .39, ΔR² = .03, F(4, 240) = 2.71, P < .05, accounting for 3% of additional variance (small effect size). Of the FDS sub-scales, discomfort intolerance was the only unique predictor (t = 3.11, P < .01, ß = .22). In the second regression, self-esteem accounted for 22% of the variance on step 1, R = .47, R² = .22, F(1, 246) = 70.18, P < .001, and discomfort intolerance accounted for 6% of remaining variance on step 2, R = .53, R² = .28, ΔR² = .06, F(1, 245) = 21.31, P < .001. When the order of entry was reversed, discomfort intolerance explained 18% of variance on step 1, R = .43, R² = .18, F(1, 246) = 54.81, P < .001, and self-esteem 28% on step 2, ΔR² = .10, F(1, 245) = 34.91, P < .001.

Discussion

The results of this study provide evidence for the validity of the FDS. As expected, frustration intolerance beliefs were significantly related to negative emotions. More importantly, specific FDS sub-scales were associated with distinct emotions, supporting a multidimensional model of this concept. Thus, emotional intolerance was a unique predictor of anxiety, discomfort intolerance of depressed mood, and entitlement of anger. That these sub-scales remained significant predictors, even though highly intercorrelated and sharing substantial common variance, underlines the strength of their contribution to the regression model. Furthermore, these FDS sub-scales remained significant predictors even when negative affect and self-esteem were taken into account. The effect sizes were large, except for depressed mood, although even this degree of association is likely to be conservative, given that control variables initially secure any overlapping variance.

All the sub-scales remained significantly correlated with the emotions when controlling for self-esteem. Given the expected overlap between self-worth and frustration intolerance, this provides good evidence of the usefulness of separating these two categories of belief. Although achievement had no unique relationship with the emotion measures, it nevertheless remained correlated with anxiety and anger when controlling for negative affect and self-esteem. This supports the proposition that perfectionistic beliefs can be dysfunctional, independent of self-worth, when phrased in terms of frustration intolerance beliefs.

The relative contribution of self-worth and frustration intolerance beliefs was very similar to the preliminary scale study (Harrington, 2003). Regarding anger, the entitlement sub-scale accounted for a substantial amount of variance. In comparison, the relationship of self-esteem with anger was weak, and became insignificant when entitlement was taken into account. This is consistent with previous research indicating little association between low self-esteem and anger (Baumeister, Smart, & Boden, 1996). The alternative proposal linking high self-esteem to anger also received little support, with high self-esteem individuals reporting lower levels of anger. Moreover, the ‘intolerance of criticism’ item, which had the strongest correlation with anger, showed a negligible relationship with self-esteem. This raises the possibility that entitlement is the central link between intolerance of criticism, narcissism, and anger, and that this relationship is independent of the level of self-esteem. Certainly, the present study suggests that entitlement beliefs are best considered a dimension of frustration intolerance, separate from self-worth. These results also question the current REBT model of anger, which assumes anger can arise from both frustration intolerance and self-worth beliefs (Dryden, 1990). Rather, the data suggest frustration intolerance is by far the most important belief in anger, with self-worth having little relationship.

Both categories of belief were significant predictors of anxiety. However, it was interesting that self-esteem failed to remain a predictor when controlling for emotional intolerance. This may reflect the importance of experiential and emotional avoidance in maintaining anxiety—a central feature of many explanatory models (e.g., Roemer, Salters, Raffa, & Orsillo, 2005). It is also consistent with REBT theory regarding the role of frustration intolerance beliefs at a “secondary” or “metacognitive” level (Ellis, 1979). Thus, whilst some anxiety problems may initially derive from threatened self-worth, the intolerance of anxiety is frequently a secondary problem. On the other hand, many anxiety problems may only involve emotional intolerance, and have no relationship with self-worth. This pattern was reversed for depressed mood, with discomfort intolerance accounting for a substantially lower amount of variance when controlling for self-esteem.

The present study has some important therapeutic implications. Commonly in therapy, several psychological problems are presented surrounded by a network of dysfunctional beliefs. In comparison to other approaches, REBT aims to target core beliefs early in therapy, and is often guided by theoretical assumptions as to which beliefs are related to particular problems (Walen et al., 1992). Clearly, such a strategy increases the risk that irrelevant beliefs may be disputed, reducing the effectiveness of therapy. Unfortunately, there is a lack of empirical evidence as to which beliefs should be targeted for specific problems. This present study represents a preliminary attempt to map the relationship between specific irrational beliefs and the emotional disorders.

As such, the results do suggest current models of disturbance may require modification. Most notably, the data indicates that entitlement beliefs should be the therapeutic focus in anger problems, and not self-worth. This is contrary to recommendations to reduce high self-esteem (Twenge & Campbell, 2003), or increase self-acceptance (e.g., Beck, 1999; Jones & Trower, 2004). Indeed, it could be argued that high entitlement individuals are less concerned with approval, than with gaining what they want. Interestingly, the belief “I must get what I want” has also been described as central to frustration intolerance depression (Hauck, 1974). However, the present results clearly indicate this belief is more characteristic of entitlement, and that entitlement has a relatively weak relationship with depression. This raises doubts as to whether focusing on the “unfairness of life” and “not getting what one deserves” will be effective for this type of depression. Rather, the evidence suggests these beliefs are more likely to lead to anger, and it would be better to target discomfort intolerance beliefs, such as helplessness and intolerance of difficulty.

More generally, the present study demonstrates the usefulness of employing a multidimensional model of frustration intolerance in therapy formulation. This may be of particular importance in complex problems, where different frustration intolerance dimensions may combine, along with self-worth, to produce distinctive patterns of disturbance (Harrington, 2005c). For such problems, there is also a danger that therapy will focus on prominent beliefs, such as self-worth, to the detriment of more subtle but pervasive frustration intolerance beliefs.

There are several possible limitations to this study. Firstly, it could be argued that the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale does not adequately represent the REBT concept of self-acceptance. However, the Rosenberg scale was designed to measure global negative self-worth, which is a defining characteristic of low self-acceptance. Consistent with this, Chamberlain and Haaga (2001) report a high correlation (r = −.56) between a REBT measure of self-acceptance and the Rosenberg scale. Nevertheless, it would be useful in future research to employ specific measures of REBT self-worth beliefs (Chadwick et al., 1999; Chamberlain & Haaga, 2001), so as to explore the relationship between the two belief categories.

A second limitation was the lack of formal diagnosis, increasing the uncertainty as to how far these results generalise to other clinical populations. For instance, it can be argued that high scores on self-report depression scales reflect dysphoria, rather than clinical depression. On the other hand, irrational beliefs may be best viewed as associated with a continuum of emotional dysfunction (McDermut et al., 1997). Furthermore, the emotional measures largely refer to dysfunctional symptoms, and a substantial proportion of the population was above the cut-points indicative of clinical disorder. Given this, it seems reasonable to conclude that the present results strongly indicate a relationship between frustration intolerance beliefs and emotional disturbance.

Although future research would benefit from employing specific diagnostic groups, it may also prove useful to investigate the role of frustration intolerance as a transdiagnostic process (Harvey, Watkins, Mansell, & Shafran, 2004). Such processes, cutting across specific disorders, are likely to be important in understanding therapy resistance and relapse. For instance, there is some preliminary evidence that entitlement beliefs may be significantly related to therapy dropout, and discomfort intolerance to increased number of therapy sessions (Harrington, 2003). It seems likely that the different frustration intolerance dimensions will play distinct roles in maintaining avoidance behavior. It is hoped that the present multidimensional scale will enable a more detailed analysis of these processes, and encourage further empirical investigation of the REBT model of disturbance.

References

Alden, L. E., Ryder, A G., & Mellings, T. M. B. (2002). Perfectionism in the context of social fears: Toward a two-component model. In G. L. Flett, P. L. Hewitt (Eds.), Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment (pp. 373–391). American Psychological Association.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington DC: Author.

Baumeister, R. F., & Smart, L., & Boden, J. (1996). Relation of threatened egotism to violence and aggression: The dark side of high self-esteem. Psychological Review, 103, 5–33.

Beck, A. T. (1999). Prisoners of hate: The cognitive basis of anger, hostility, and violence. New York: Harper Collins.

Bond, W. B., & Dryden, W. (2000). How rational beliefs and irrational beliefs affect people’s inferences: An experimental investigation. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 28, 33–43.

Brown, G., & Beck, A. T. (1989). The role of imperatives in psychopathology: A reply to Ellis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 13, 315–321.

Buhr, K., & Dugas, M. J. (2002). The intolerance of uncertainty scale: Psychometric properties of the English version. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40, 931–945.

Chadwick, P., Trower, P., & Dagnan, D. (1999). Measuring negative person evaluations: The evaluative beliefs scale. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 23, 549–559.

Chamberlain, J. M., & Haaga, D. A. F. (2001). Unconditional self-acceptance and psychological health. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 19, 163–176.

Chang, C. E., & D’Zurilla, J. T. (1996). Irrational beliefs as predictors of anxiety and depression in a college population. Personality and Individual Differences, 20, 215–219.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the Behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Corwyn, R. F. (2000). The factor structure of global self-esteem among adolescents and adults. Journal of Research in Personality, 34, 357–379.

Crawford, J. R., Henry, J. D., Crombie, C., & Taylor, E. P. (2001). Normative data for the HADS from a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 40, 429–432.

Deffenbacher, J. L., Oetting, E. R. Thwaites, G. A., Lynch, R. S., Baker, D. A., Stark, R. S., Thacker, S., & Eiswerth-Cox, L. (1996). State-trait anger theory and the utility of the trait anger scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 43, 131–148.

Deffenbacher, J. L., Zwemer, W. A., Whisman, M. A., Hill, R. A., & Sloan, R. D. (1986). Irrational beliefs and anxiety. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 10, 281–292.

Derogatis, L. R. (1994). SCL-90-R administration, scoring and procedures manual (3rd ed.). Minneapolis: National Computer Systems.

DiGiuseppe, R. (1996). The nature of irrational and rational beliefs: Progress in rational emotive behavior therapy. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 14, 5–28 .

Dryden, W. (1990). Dealing with anger problems: Rational-emotive therapeutic interventions. Sarasota: Professional Resource Exchange Inc.

Dryden, W. (1999). Beyond LFT and discomfort disturbance: The case for the term “Non-ego disturbance”. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 17, 165–200.

Dryden, W., & Gordon, W. (1993). Beating the comfort trap. London: Sheldon Press.

Dugas, M. J., Gagnon, F., Ladouceur, R., & Freeston, M. H. (1998). Generalized anxiety disorder: A Preliminary test of a conceptual model. Behaviour Therapy and Research, 36, 215–226.

Ellis, A. (1979). ‘Discomfort anxiety’: A new cognitive behavioral construct. Part I. Rational Living, 14, 3–8.

Ellis, A. (1980). ‘Discomfort anxiety’: A new cognitive behavioral construct. Part II. Rational Living, 15, 25–30.

Harrington, N. (2003). The development of a multidimensional scale to measure irrational beliefs regarding frustration intolerance. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Edinburgh.

Harrington, N. (2005a). The Frustration Discomfort Scale: Development and psychometric properties. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 12, 374–387.

Harrington, N. (2005b). It’s too difficult! Frustration intolerance beliefs and procrastination. Personality and Individual Differences, 39, 873–883.

Harrington, N. (2005c). Dimensions of frustration intolerance and their relationship to self-control problems. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 23, 1–20.

Harvey, A., Watkins, E., Mansell, W., & Shafran, R. (2004). Cognitive behavioural processes across psychological disorders. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hauck, P. (1974). Overcoming depression. Philadelphia: Westminster Press.

Herrmann, C. (1997). International experiences with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – A review of validation data and clinical results. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 42, 17–41.

Horney, K. (1950). Neurosis and human growth. New York: Norton and Co.

John O. P., & Benet-Martínez V. (2000). Measurement: Reliability, construct validation, and scale construction. In H. T. Reis & C. M. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology (pp. 339–369). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press .

Jones, J., & Trower, P. (2004). Irrational and evaluative beliefs in individuals with anger disorders. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 22, 153–169.

Kendall, P. C., Haaga, D. A. F., Ellis, A., Bernard, M., DiGiuseppe, R., & Kassinove, H. (1995). Rational-emotive therapy in the 1990 and beyond: Current status, recent revisions, and research questions. Clinical Psychology Review, 15, 169–185.

Major, B. (1994). From social inequality to personal entitlement: The role of social comparisons, legitimacy appraisals, and group membership. Advances in Experimental Social psychology, 26, 293–355.

Martin, R. C., & Dahlen, E. R. (2004). Irrational beliefs and the expression of anger. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 22, 3–20.

McDermut, J. F., Haaga, D. A. F., Bilek, L. A. (1997). Cognitive bias and irrational beliefs in major depression and dysphoria. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 21, 459–476.

McMurran, M., Egan, V., Richardson, C., Street, H., Ahmadi, S., & Cooper, G. (2000). Referrals for anger and aggression in forensic psychology outpatient services. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry, 11, 206–213.

Meng, X., Rosenthal, R., & Rubin, D. B. (1992). Comparing correlated correlation coefficients. Psychological Bulletin, 111, 172–175.

Roemer, L., Salters, K., Raffa, S. D., & Orsillo, S. M. (2005). Fear and avoidance of internal experiences in GAD: Preliminary tests of a conceptual model. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 29, 71–88.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Spielberger, C. D., Jacobs, G., Russell, S., & Crane, R. (1983). Assessment of anger: The State-Trait Anger Scale. In J. N. Butcher & C. D. Spielberger (Eds.), Advances in personality assessment (Vol. 3). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Turvey, T., Humphreys, L., Smith, F., & Smeddle, M. (1998). Adult mental health outcome survey 1998. Unpublished research. Fife Healthcare NHS Trust.

Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2003). “Isn’t it fun to get the respect that we’re going to deserve?” Narcissism, social rejection, and aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 261–272.

Walen, S. R., DiGiuseppe, R., & Dryden, W. (1992). Practitioner’s guide to rational-emotive therapy (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67, 361–370.

Acknowledgment

This paper is based on research submitted to the University of Edinburgh in fulfilment of a Doctorate of Philosophy degree. I would like to thank Professor Mick Power for his help and encouragement throughout the research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Copies of the Frustration Discomfort Scale are available from the author on request

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harrington, N. Frustration Intolerance Beliefs: Their Relationship with Depression, Anxiety, and Anger, in a Clinical Population. Cogn Ther Res 30, 699–709 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-006-9061-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-006-9061-6