Abstract

Activities aimed at promoting sustainable consumption need to be introduced into everyday settings, as sustainable consumption behaviour needs to become part of daily living. Therefore it is worthwhile reflecting on social settings where consumption plays a minor role, but where people nonetheless learn and experience new attitudes and behaviours. The workplace is an important focal point of adults’ daily routines. This paper examines companies’ role in promoting sustainable consumption of their employees.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Putting sustainable consumption into practice is dependent upon our understanding of normality. The conduct of everyday life refers to the habits of the individual and the structuring of day-to-day activities in all areas of life. The repetition of certain activities and behavioural patterns results in subjective interpretations of normality. Putting sustainable consumption into practice depends on its integration into everyday life and habitual activities which are perceived as normal. Therefore, activities aimed at promoting sustainable consumption need to be introduced into everyday settings. Analysing the opportunities and challenges of these everyday settings is a precondition for creating successful practical approaches in these contexts. Workplaces are key settings in adults’ daily routines. They shape people’s attitudes and behaviour and provide important peer groups. Workplace conditions have the power to broaden or constrain the opportunities people have to behave in certain ways, including their sustainable consumption behaviour. This paper aims at examining companies’ role in promoting sustainable consumption. After introducing the theoretical background, this paper first illustrates the suitability of workplaces as “learning places” for sustainable consumption. Secondly, companies’ potentials concerning their engagement in promoting sustainable consumption will be enlightened. Thirdly, factors that are considered important in the promotion of employees’ sustainable consumption are presented.

Everyday Settings and Learning

There is a huge variety of theoretical and practical approaches dedicated to enhancing sustainable consumption (e.g., IÖW 2009; Schrader 2007; WBCSD 2008). Although many studies show an increase in environmental consciousness and individual behaviour change, changes are lacking in quality and quantity (e.g., Jackson 2006a, b). It is fair to say that processes of collective change take time, as does the implementation of certain policies. Thus, one could argue that the full potential of the implemented approaches to promote sustainable consumption has not yet been realized.

It has been argued that the dominant focus in consumer research on the change of individual unsustainable consumption patterns has impeded the development of policy-relevant concepts for enhancing sustainable consumption and a sustainable society (e.g., Spaargaren 2003). Approaches which posit consumers as “victims” who cannot escape from their circumstances (e.g., Sanne 2002) are likewise ineffective in bringing about change. It is important to reflect on social structures that may be both determined by and determine the scope of individual actions (e.g., Ölander and Thøgersen 1995). Analyses of both individual behaviour and social structure are prerequisites to understanding social practice (e.g., Warde 2005). Sociological theories which contextualize both human agency and social structures are fundamental to understanding interdependencies (e.g., Bourdieu 1984; Giddens 1984). In contrast to most theories of action, Bourdieu’s concept of “habitus” as an incorporated social structure reveals that individual behaviour is not primarily intentional but intuitive. His social practice approach reveals that individuals act with a certain “practical sense,” in which cultural and class-specific patterns are reproduced. Therefore, practice theory is appropriate for decoding everyday actions such as consumption habits, which are individually embodied social conditions (Bourdieu 1987). A large number of empirical studies in different branches of consumption document the importance of contextual factors on behaviour (e.g., Ölander and Thøgersen 1995; Spaargaren 2003; Stern 2000). Even though these integrated consumer studies have sparked interest in the complexity of consumer behaviour, their range of vision is limited. As consumer studies, most of them concentrate on consumption and/or consumption-related behaviour, as well as analysing either the constraints of structure or the individual reasons for unsustainable practices. They usually conclude with certain hints for change in agency and/or structure. Hence, these approaches can be characterized as consumption-focused and problem-oriented.

I propose a different perspective on sustainable consumption with new and promising starting points: firstly by recognizing people in all their various social contexts, where consumption is less important and where they are not primarily performing as consumers, and secondly by assuming that certain settings have an enabling and facilitating capacity for the enhancement of sustainable consumption. This capacity is understood to significantly influence peoples’ behavioural patterns. As consumption patterns are important aspects of peoples’ lifestyles, which are influenced by their everyday settings, an approach which focuses on learning and socialization in everyday settings is useful for establishing good starting points for the promotion of sustainable consumption.

The importance of everyday settings is perfectly illustrated by the “settings approach;” a core strategy within health promotion (WHO 2009). “Settings” refer to everyday locations as social contexts, where people work, learn, and live. As people spend most of their time under these conditions, health is seen as a product of these settings rather than of any external activities. It is argued that health promotion needs to take place in the same settings, as they provide opportunities to reach target groups and to implement the required theoretical and practical knowledge. Although the “settings approach” does not refer in particular to socialization theories, it is a core insight that new behavioural patterns can only be acquired in these social learning contexts. Concrete concepts and codes of practice aimed at enhancing health in these locations are still deficient, yet the “settings approach” is accepted as a reasonable approach, especially for areas where health care services are not commonplace (WHO 2009).

When analysing people’s everyday routines in order to establish their focal points of life, various organizations cannot be overlooked. Different organizations play a pivotal role in a person’s everyday life at different times. Schools, universities, and workplaces are examples of institutions that are integral to everyday life during childhood, youth, and adulthood. They determine routines and prescribe peer groups. A huge amount of formal and informal learning takes place in these locations. Therefore, they are important settings for (organizational) socialization (e.g., Chao et al. 1994) and formal education. In accordance with the “settings approach,” sustainable consumption patterns need to be learned in those key organizations, as people spend most of their time there. Although the lifestyles and daily activities of people differ, most are integrated into these organizations, which offer a great chance for much needed mainstreaming processes of sustainable consumption (e.g., Fricke and Schrader 2009).

It is worthwhile taking a closer look at such key organizations and their role in socialising people for sustainable consumption. In the following section, workplaces will be examined in more detail.

Companies and Sustainable Consumption

A growing number of companies are adopting the principles of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Beyond complying with legal regulations, these companies take social and environmental concerns into consideration (e.g., Crane et al. 2008). Employees are an important target group for internal CSR activities concerning, for instance, work–life balance arrangements, occupational health and safety actions, and the enhancement of labour rights and life-long learning. In these activities, employees are perceived as crucial internal stakeholders, whose needs and everyday problems must be addressed. Many companies also stress the importance of employees’ concerns and lifestyle problems in their mission statements. One of the world’s leading consumer goods companies writes in its vision: “Our People Vitality Program aims to enhance the personal well-being and effectiveness of our people through advice on exercise, nutrition and mental resilience” (Unilever 2010). Another company claims that it is “providing improved health and lifestyle information to [its] employees” (Marks & Spencer 2010). One of the largest cosmetic franchises in the world has an initiative called “Learning is Of Value to Everyone,” in which it states, “by funding a range of training courses, events and health treatments, we aim to enhance our staff’s sense of wellbeing” (The Body Shop 2009). Even though consumption is an important factor for physical and social wellbeing, it is rare for companies to support employees’ private, sustainable consumption, however.

While a certain degree of spillover effects from the workplace into private social settings might occur (Berger and Kanetkar 1995; Thøgersen 1999; Thøgersen and Ölander 2003), companies that are engaged in employees’ sustainable behavioural patterns as part of their CSR, for example waste management, energy consumption, or food supply, do not usually reflect on effects these organizational arrangements can have on employees’ private consumption behaviour in general. Mobility management (especially concerning the route to and from work) figures as a “grey area” between private and workplace-related behaviour, meaning that such interventions often embrace private consumption patterns. However, in most cases, companies’ interventions for sustainability focus on workplace-related actions. They do not help to dismantle certain behavioural barriers for sustainable consumption in employees’ private lives, and they lack any insight into how these experiences may be transferred to the private household or other social settings. Therefore, it is possible that company-related activities might influence employees’ private consumption behaviour, but it is equally possible that they do not. It is rarely seen that companies actively and consciously strengthen private sustainable consumption behaviour among their employees.

Instead, active sustainable consumption promotion takes place on the business-to-business marketplace (through the creation of sustainable supply chains) and on the business-to-consumer marketplace (through the promotion of innovative sustainable products, and the removal of unsustainable products from the marketplace) (WBSCB 2008). But consumers are not merely external stakeholders (Fig. 1). Employees are consumers too, and they can be addressed differently from other consumers. Presently, activities geared towards sustainable consumption concentrate exclusively on external stakeholders.

Up to now, companies have not usually supported their employees’ sustainable consumption patterns as they do not recognize them in their role as consumers. Their organizational culture might bring about sustainable behavioural patterns at the workplace, but it does not explicitly support sustainable consumption styles.

Nevertheless, companies supposedly have great potentials for promoting sustainable consumption styles. It is a somewhat simple, yet fundamental, principle that companies should recognize employees in their different roles. Employees are predominantly acting as producers at the workplace and as consumers in private life (e.g., Scherhorn 1980). Companies should be able to consider employees in their twofold role as consumers and producers. In addition to the aforementioned spillover effects, which are a product of the incidental transfer of experiences from one area of life to another, sustainable consumption needs to be strengthened actively and consciously (Fig. 2). Work-related interventions will address just one part of employees’ behavioural patterns. Companies that create interventions for sustainable behavioural patterns at work and sustainable consumption at home might actually help to create consistent sustainable lifestyles.

Theoretical approaches and empirical research concerning the workplace influence on sustainable consumption patterns are rare (e.g., ISOE et al. 2010). There is more research about the relevance of other key organizations, such as schools and universities, places of formal learning and socialization, for sustainable consumption (e.g., BINK 2010).

Promoting Sustainable Consumption of Employees

In the following, the “workplace setting” will be outlined according to three questions: (1) Why do workplaces provide suitable settings for learning sustainable consumption? (2) What reasons companies have for these actions? (3) What factors are supposed to characterize successful activities for promoting sustainable consumption?

Suitability of Workplace Settings for Promoting Employees’ Sustainable Consumption

Although the term “workplace” does not refer to a defined set of conditions, it can be assumed that some general characteristics are inherent in most company settings. People do not live in the workplace. Employees spend a certain amount of time there, carrying out their duties in exchange for payment. Although the number of people now working from home is increasing, the following considerations will concentrate on company workplaces.

Companies are places of learning. On the one hand, they focus on formal learning processes and education, for example, in-house training, vocational education, and learning how to operate new devices. Issues of sustainable consumption can be integrated into these formal learning processes. On the other hand, companies have specific organizational structures, which manifest themselves as formal and informal rules and norms (e.g., working times or codes of conduct), as certain constellations of relationships (e.g., between management and employees) and certain patterns of interpretation (e.g., an open door signals that colleagues can come in; e.g., Daft 2007). These social structures within organizations trigger the aforementioned organizational socialization process, which is primarily about employees adopting certain behaviour and attitudes in order to become a member of the organization (e.g., Chao et al. 1994). There might be some company organizational structures which are particularly advantageous for learning sustainable consumption. In the following section, the aspects most typically prevalent in companies’ social systems will be focussed upon.

Firstly, the workplace is naturally understood to be a place for learning and experience. In-house training and further educational activities are perceived as part and parcel of working life. Employees are under constant pressure to adapt and grow (Packer and Sharrar 2003), because a life-long career with one single employer is unlikely. Information campaigns, learning arrangements, and learning for sustainable consumption in particular might seem more acceptable in this context than in free time settings, where learning objectives are motivated by individual taste and preference. At work, employees subordinate their private interests to work-related issues, and are free of private obligations and distractions. Therefore, activities during working time might not only benefit from the “learning atmosphere” of the workplace, but might also reach people that are normally difficult to engage in issues of sustainability, due to different priorities in their free time.

Secondly, companies attend to the concerns of both internal and external stakeholders. They might practice different forms of employee participation in order to consider employees’ thoughts, ideas, and concerns. These participation forms (e.g., idea management, work councils, employee representatives, labour unions, etc.) can be used to reflect on certain consumption issues and to set up activities which correspond to employees’ needs (e.g., Poutsma et al. 2003). Additionally, it is common for companies to offer incentives as a means of enhancing employees’ readiness to come up with innovative ideas, or to encourage their engagement with company practices. Such reward systems can also be used in conjunction with activities for promoting sustainable consumption. Given that companies also take into account the concerns of their external stakeholders (e.g., Selsky and Parker 2005), it has become normal for them to set up certain arrangements, networks or partnerships with other companies, organizations, or the government. Even though it remains a challenge to identify the correct partners and cooperate successfully, such skills are essential to implement their corporate responsibility. Therefore, companies should be able to do so in favour of sustainable consumption.

Thirdly, organizational relationship patterns can prove useful when planning sustainable consumption interventions. Companies are commonly structured hierarchically. In such cases, managers and other superiors might act as role models for their subordinates (e.g., Chao et al. 1994), meaning that the sustainable consumption patterns of superiors might help to enhance those of their subordinates. Colleagues are also important peer groups. An atmosphere of camaraderie could work to lessen employees’ reluctance to participate in certain activities or adapt new behavioural patterns. The “I will if you will” principle can be perfectly realized at the workplace (SCR 2006). The creation of a certain organizational culture in which the promotion and approval of sustainable lifestyles becomes matter of course helps employees to stay motivated and committed.

Fourthly, companies that already consider sustainability issues in the workplace are well equipped to extend these activities to consumption issues at home. Employees are already sensitized to sustainable behavioural patterns and have experienced firsthand the consequences of behavioural changes in the organization. Companies with successful waste management programmes, for instance, could offer information and assistance for recycling and waste avoidance at home. Companies that sell organic products in their cafeterias could provide employees with additional information, could put on special offers outside working hours, or could facilitate collective orders from nearby organic farmers. In contrast to organizations that have not yet integrated any organizational changes for sustainability, these companies might be able to realize these goals rather simply, yet effectively.

In summary, it can be assumed that workplaces provide certain conditions which are beneficial for sustainable consumption learning. Nevertheless, there is a risk that company interventions might generate employee reactance. Reactance appears if someone perceives a threat to his or her personal freedom, for instance when someone feels pressured to accept a certain view or attitude, or feels forced to behave in a certain way (Brehm et al. 1966). Consumption could prove a very sensitive issue for employees who view their consumer decisions as private and personal. In such cases, an employer’s interest in their private matters could meet with refusal or reluctance. Such reactions might strengthen an attitude or behaviour that is just the opposite of what was intended. Given that interventions always carry the risk of reinforcing or reenergizing unsustainable habits, it is vital that activities are managed with care and sensitivity. In view of these risks, it is important to illustrate what advantages these interventions might have for companies.

Benefits for Companies

As sustainable consumption is a normative concept it is easy to find arguments for why companies should promote their employees’ sustainable consumption. Even though it is commonly accepted that the economy is dependent on certain social values and norms, there is still no consensus on companies’ contribution to upholding these values. Following the rational choice paradigm could have positive effects if the enhancement of values and norms was gratified as much as, or even more than, they cost. As this is not necessarily the case, CSR activities to promote sustainable development are always accompanied by questions as to whether they pay off. The debate surrounding this controversial question demonstrates that there is no single answer. Different studies find both positive and negative relationships between CSR-activities and financial outcomes (e.g., Burke and Logsdon 1999; den Hond et al. 2007; Vogel 2005). Moreover, there are many CSR activities that can be applied very differently according to their quality, their coverage, and their continuance. It is difficult to calculate or estimate costs and benefits with an acceptable degree of certainty. Hence, the following aspects are seen as positive arguments for employers that are already conscious about their responsibility and that operate proactively.

Many reasons that are proposed by companies’ managements for adopting CSR are also valid for sustainable consumption activities. Nevertheless, sustainable consumption activities are special in that they demand explicit and sensitive attention to employees’ personal and non-organizational behaviour. Hence, sustainable consumption activities are seen as a unique feature in the CSR profile, but also as a promising complement to other CSR activities.

Firstly, activities aimed at promoting sustainable consumption might facilitate organizational change towards sustainability. Organizational change might risk negative reactions on the part of employees, such as distrust or resistance, which could potentially be prevented by paying due attention to employees’ concerns (Stanley et al. 2005). This requires involving employees in organizational change and a participatory style of management (e.g., Brown and Cregan 2008). Consumption activities are considered helpful in involving employees and asserting companies’ interest in employee issues. It can be assumed that employees are more likely to approve of certain activities if they can directly experience and influence them. According to employees’ requirements, centralized orders of organic products, for instance, can be arranged differently in terms of frequency or variety of products. Involving the employees might have positive effects on employees’ acceptance concerning the whole organizational change process, and might in turn strengthen a sense of togetherness among employees.

Secondly, any lived culture of sustainability in an organization requires corresponding attitudes and behaviour on the part of all members of that organization (e.g., Cramer 2005). Individual workplace-related learning is considered one-dimensional and insufficient. If CSR is to be a holistic and integrative concept, employees must be recognized as people that are active in a wide range of social contexts. Reflecting on employees’ private consumption issues and assisting them in the small challenges of their daily lives fulfils CSR as corporate social responsibility. The intended behavioural changes might have a retroactive effect on workplace-related activities as well as the work performance. Therefore, employees who uphold sustainable ways of life at home are also likely to do so at the workplace. Ultimately a holistic CSR concept can only be established by taking into account the complexity of sustainability in all its facets.

Thirdly, it is important to acknowledge that companies’ engagement in employees’ concerns can also have positive effects on workers’ motivation and how long they stay in their jobs. Due in particular to shortages of skilled workers, companies’ levels of performance are becoming increasingly important. They need to define their “employer brand,” which depends on certain features offered to employees (Greening and Turban 2000). Conventional incentives that are offered in the hope of attracting or retaining employees can be reconceived as sustainable incentives. For example, companies can provide eco-efficient cars for employees, they can offer discounted train tickets, or they can pay for flight emissions. Hence, support for sustainable consumption might figure as a competitive advantage with regard to recruitment and if used as such it could have a positive “push-effect” on other companies. Moreover, companies that adopt such ideas will be “first-movers” in this area and there might be “first-mover-advantages” (e.g., image advantages, positive publicity, etc.) that the company will profit from (e.g., Tetrault Sirsly and Lamertz 2008).

Fourthly, supporting employees regarding their private consumption issues might lead them to spread the word in their social setting. It is very important for companies to “talk the CSR-walk” to consumers and other external stakeholders (e.g., Schrader et al. 2008), therefore employees should be considered important communicators. Activities aimed at employees and their private concerns are perhaps more likely to be communicated to friends and family than other company activities. Given that word-of-mouth is a highly effective mode of publicity, companies’ engagement in employees concerns might help improve the company’s image.

In summary, there are numerous grounds for companies to promote sustainable consumption (Fig. 3). Sustainable consumption interventions could round off their present CSR activities and they may help to create companies’ CSR profiles.

Requirements for Success

There is a wide range of interventions that can be applied in companies making employees’ private consumption more sustainable. These include adding information and assistance for private issues to existing internal CSR activities as well as establishing new activities. Under all circumstances, doing so calls for the creation of an organizational culture, which encourages a sustainable lifestyle in all its facets. This is undoubtedly a big challenge as there are many (indirect) factors that have an impact on employees’ consumption patterns. For instance, corporate arrangements concerning working times influence employees’ mobility behaviour and eating habits. However, the following considerations concentrate on active, direct, and consumption-related activities that can be incorporated into workplace settings. In general, there are two complementary approaches that should be considered. One is enhancing employees’ knowledge, capability, and motivation to consume differently. The other one is enhancing the desirability of sustainable goods by making them cheaper and/or more convenient. Given that each company will choose which interventions are suitable to its particular situation, I do not focus on the details of those activities, but on possible determinants of implementing them successfully.

The overall objective should be to set up interventions which establish an organizational culture in which employees learn sustainable consumption patterns. Because of the complexity of the factors which influence behavioural patterns, tangible changes cannot be the only benchmark for successful activities. Interventions that generate important preconditions for behavioural change will also be perceived as successful. With reference to social learning theory, practicability, and motivation are also considered crucial preconditions for learning sustainable consumption patterns through companies’ interventions (Bandura 1977). Moreover, companies’ engagement for sustainable consumption needs to be accepted by the employees, since consumption is, as mentioned previously, a very sensitive issue. It is not only important to avoid reactance, but it is also essential to foster positive attitudes and feelings. Employees who appreciate the activities and are pleased to gain new knowledge and experience will demonstrate much more interest and motivation. It can be assumed that objectives such as motivation, practicability, and acceptance are interdependent. It is useful to consider possible determinants that may play a key role in achieving them.

First, the corporate framework conditions within which activities promoting sustainable consumption take place should be considered. The planning and organizing of interventions should begin with an analysis of a company’s characteristics and competences, since these framework conditions might influence the interventions’ credibility and acceptance. This inside-out strategy is appropriate because activities need to be matched to the company and not the other way around (e.g., Prahalad and Hamel 1990). In this context, it might be appropriate to reflect on internal organizational shortcomings too. It is important, for instance, to avoid sending conflicting messages, such as, encouraging employees to avoid wasteful practices at home, while wasting paper within the company. Companies should aim to anchor these activities in the long-term corporate performance and, hence, they should be tailored to each individual company. Especially in the early stages, employees are likely to consider interventions more credible and authentic if they see direct links to their jobs and the particular nature of their company.

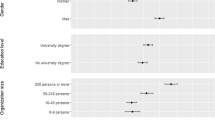

Second, employee orientation is advisable, given that employees are a heterogeneous group of people that have different attitudes and needs. Consequently, different forms of information, support, and participation are required, to reflect on their unsustainable consumption behaviour while presenting customized sustainable products, services, and support. Lifestyle approaches have revealed that there are different rationalities and understandings within social groups, which means that employees’ perception of what is practical depends on their individual attitudes and knowledge (e.g., UBA 2008). Unspecific interventions can lead to misunderstandings and reactance. For example, scepticism and rejection of organic products in some sections of the population can partly be seen as a result of misleading and inadequate campaigns (e.g., Kleinhückelkotten 2005). Thus, activities must match employees’ needs. But target-group communication for employees demands special consideration. As mentioned before, avoiding reactance is of prime importance, meaning that selecting different employee target groups is inadvisable. Selection and separation may limit personal freedom, which can lead to reactance. In terms of data protection, employers are unsuitable to survey employees’ private attitudes and behavioural patterns. Target group communication must therefore be carried out implicitly. After employees’ different interests and requests have been identified (e.g., through employee suggestions, team meetings, questionnaires, etc.), a range of activities should be considered accordingly. Activities should cover a range of different interests (variety of information), but they should also provide information on different levels (quality of information). Employees should be free to choose their own favourite activities (self-selection). The ability to choose freely from a variety of activities is likely to increase employees’ motivation to participate as well as their acceptance of the programme. Nevertheless, initiating interventions which take into account a range of needs might require resources that are beyond the means of a single company. It might be necessary to collaborate with external stakeholders and gain public support.

Third, participation by both employees and management is a further key factor. Participative and cooperative strategies are generally seen as central approaches in the promotion of sustainable development. The participation of different stakeholders and interest groups imply social learning processes and, as for collaboration, requires reflections on the various needs and desires, a certain degree of give-and-take, and the development of joint objectives and strategies. Therefore public and corporate policies (CSR activities) for sustainable development centre on participation (e.g., UNCED 1992; WCED 1987). There is a huge variety of forms of participation in European companies. Direct participation is assumed to advance commitment and involvement, stimulating high productivity and quality in the working process (e.g., Poutsma et al. 2003). Social learning effects and commitment are preconditions for successful activities. Therefore, employee participation and integration in planning, organizing, and setting up activities is essential. Depending on the company structure, workers’ councils, employee representatives, labour unions, or other delegates can be involved. Employees’ participation is also a central condition for realizing employee orientation and facilitating customized and successful interventions. Combining different approaches to employee participation tends to give rise to a variety of incentives for employees to get involved. Moreover, the participation of management is important. As mentioned previously, managers could act as role models and assert their commitment to the cause.

Fourth, the involvement of external stakeholders such as environmental or consumer organizations is useful, as their expertise might enhance employees’ learning processes. It is worthwhile to select stakeholders who best match the particular planned activities and employees’ interests, as this will boost employee participation. Their expertise and practical skills are important for strengthening the objectives of any course of action as well as companies’ credibility and reputation in that process (e.g., Berger et al. 2006). Stakeholder involvement provides a good means of motivating employees and enlisting them in the programme. It is becoming increasingly normal practice for for-profit and not-for-profit organizations to work together and network (e.g., Selsky and Parker 2005), even though differing “rationalities” and social backgrounds can create complications (e.g., Austin 2000). Cross-sector arrangements (also cooperation with public organizations) or cooperation within the private sector can increase the acceptance of activities. Since members of all organizations have consumption issues in common, that topic is suited for local or regional projects in which cross-organizational activities, such as competitions or “theme days” might take place. Such cooperative issues are crucial for building or advancing an infrastructure for sustainable goods and services. This might in turn have positive effects on the whole local community and employees’ social environment.

Policy Implications

Public policies co-design and co-create societal consumer culture. They can influence consumer framework conditions directly, by raising taxes or implementing educational campaigns, for instance. Public policies can also influence peoples’ behaviour indirectly, however. Because companies have the potential to shape framework conditions under which employees can consume more responsibly, social framework conditions that strengthen that potential need to be created too (see Fig. 4). By influencing the framework conditions under which companies implement activities aimed at promoting sustainable consumption among their employees, public policies have an indirect influence on employees’ consumption behaviour.

In general, national strategies to enhance CSR have either only recently been developed or remain works in progress (CSR in Europe 2010; IÖW 2009). Companies’ potential for promoting employees’ consumption patterns has not yet been taken into account in this connection, however. Central elements that still require integration are considered in the following.

First, public information and communication policies are needed to propagate the innovative role of companies. Companies should be initiated into the basic principles of this new sphere of activity via various communication channels. Business associations, media, employee representatives, or trade unions need to be informed. Employees must be kept in the know and should be encouraged to raise the issue of sustainable consumption with colleagues.

Second, companies need to be instructed as to how best to implement various activities. Information and instruction guides can be prepared for these purposes. This also requires an enhancement of theoretical and empirical research in this field. Local communities can help to create networks and partnerships between participating companies and other stakeholders. Incentives and reward systems can be established, by initiating competitions, for instance.

Lastly, public institutions should lead by example. They can demonstrate the important role that employers have regarding employees’ consumption patterns, which might have positive effects on other institutions and companies. In particular, public institutions can show that employees are more than “human resources” but people with differing sustainable lifestyles. In public schools and universities, it is particularly important to convey the message that sustainable living is appreciated across institutional borders. Future generations and prospective company leaders may well be initiated to this mode of thinking as a matter of course. Public institutions can inform the public about their experiences and document various strategies and ways of implementing activities successfully.

In general, public policies play an important role in fostering an atmosphere in which social actors who are pioneers on new paths of encouraging sustainable societal practices are appreciated.

Conclusions

It is suggested in this article that companies can substantially enhance or constrain employees’ possibilities to consume more responsibly. Workplaces are important social settings in adults’ daily routines where formal and informal learning processes take place. This learning environment, together with various corporate interventions, can help to advance employees’ sustainable consumption patterns. An increasing number of companies are engaged in internal CSR activities which often promote sustainable behavioural patterns at the workplace, suggesting that there are promising starting points for interventions that additionally promote sustainable consumption in private life.

As shown, there might be many benefits for companies supporting employees in their consumption issues. Possible determinants were presented, which are considered crucial to set up successful activities. However, framework conditions for companies that are active in this field need to be improved. Further empirical research is needed to validate the suggested determinants and to create instruction guides for companies that are willing to promote employees’ sustainable consumption. Public support is needed to communicate this new and decisive role of companies.

References

Austin, J. (2000). Strategic collaboration between nonprofits and business. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 29, 69–97.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Morristown: General Learning Press.

Berger, I. E., Cunningham, P. H., & Drumwright, M. E. (2006). Identity, identification, and relationship through social alliances. Journal of the Academy of Marketing and Science, 34, 128–137.

Berger, I. E., & Kanetkar, V. (1995). Increasing environmental sensitivity via workplace experiences. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 14, 205–215.

BINK. (2010). Bildungsinstitutionen und nachhaltiger Konsum (Educational Institutions and Sustainable Consumption). Available at: http://www.konsumkultur.de/index.php?id=2&L=1. Accessed on August 16, 2010.

(The) Body Shop. (2009). Available at: http://www.thebodyshop.com/_en/_ww/values-campaigns/self-esteem.aspx. Accessed on August 17, 2010.

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgment of taste. London: Routledge.

Bourdieu, P. (1987). Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brehm, J. W., Sensening, J., & Shaban, J. (1966). The attractiveness of an eliminated choice alternative. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2, 301–313.

Brown, M., & Cregan, C. (2008). Organizational change cynism. The role of employee involvement. Human Resource Management, 47, 667–686.

Burke, L., & Logsdon, J. M. (1999). How corporate social responsibility pays off. Long Range Planning, 29, 495–502.

Chao, G. T., O´Leary-Kelly, A. M., Wolf, S., Klein, H. J., & Gardner, P. D. (1994). Organizational socialization: Its content and consequences. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 79, 730–743.

Cramer, J. (2005). Company learning about corporate social responsibility. Business Strategy and the Environment, Special Issue: Partnerships for Sustainable Development, 14, 255–266.

Crane, A., Mc Williams, A., Matten, D., Moon, J., & Siegel, D. (2008). The Oxford handbook of corporate social responsibility. Oxford: University Press.

CSR in Europe. (2010). Available at: http://www.csreurope.org/data/files/20091012_a_guide_to_csr_in_europe_final.pdf. Accessed on August 21, 2010.

Daft, R. (2007). Organization theory and design (Ninthth ed.). Mason: Thomson South- Western.

Den Hond, F., De Bakker, F., & Neergaard, P. (2007). Managing corporate social responsibility in action. Talking, doing, measuring. Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Fricke, V., & Schrader, U. (2009). CSR mainstreaming and its influence on consumer citizenship. In: A. Klein & V. Thoresen (Eds.): Making a difference. Putting consumer citizenship into action (pp. 98–109). Hamar: Hedmark University College.

Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society. Outline of the theory of structuration. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Greening, D. W., & Turban, D. B. (2000). Corporate social performance as a competitive advantage in attracting a quality workforce. Business & Society, 39, 254–280.

ISOE (Institute for social-ecological research), IFZ (Inter-University Research Centre for Technology, Work and Culture), IfGP (Institute for Health promotion and Prevention), UBZ (Center for environmental education Steiermark): Nachhaltiges Handeln im beruflichen und privaten Alltag (Acting sustainable at the workplace and in private life). Available at: http://www.isoe.de/projekte/naha. Accessed on August 21, 2010.

IÖW. (2009). Innovative approaches in European sustainable consumption policies. Schriftenreihe des IÖW 192/09. Berlin: Institut für ökologische Wirtschaftsforschung (Institute for Ecological Economy Research).

Jackson, T. (2006a). Motivating sustainable consumption. A review of evidence on consumer behaviour and behavioural change. Centre for Environmental Strategy, Surrey: University of Surrey.

Jackson, T. (2006b). The Earthscan reader in sustainable consumption. London: Earthscan.

Kleinhückelkotten, S. (2005). Suffizienz und Lebensstile. Ansätze für eine milieuorientiere Nachhaltigkeitskommunikation (Approaches for milieu-orientated sustainability education), Berlin: Berliner Wissenschaftsverlag.

Marks & Spencer. (2010). Available at: http://plana.marksandspencer.com/about/the-plan/health/2/. Accessed on August 17, 2010.

Ölander, F., & Thøgersen, J. (1995). Understanding consumer behaviour as prerequisite for environmental protection. Journal of Consumer Policy, 18, 345–385.

Packer, A. H., & Sharrar, G. (2003). Linking lifelong learning, corporate social responsibility, and the changing nature of work. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 5, 332–341.

Poutsma, E., Hendrickx, J., & Huijgen, F. (2003). Employee participation in europe: In search of the participative workplace. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 24, 45–76.

Prahalad, C. K., & Hamel, G. (1990). The core competence of the corporation. Harvard Business Review, 68(3), 79–91.

Sanne, C. (2002). Willing consumers—or locked-in? Policies for a sustainable consumption. Ecological Economics, 42, 273–287.

Scherhorn, G. (1980). The origin of consumer problems. Journal of Consumer Policy, 4, 102–114.

Schrader, U. (2007). The moral responsibility of consumers as citizens. International Journal of Innovation and Sustainable Development, 2(2), 79–96.

Schrader, U., Hansen, U., & Halbes, S. (2008). Why do companies communicate with consumers about CSR? Conceptualization and empirical insights from Germany. Studies in Communication Sciences, 8, 303–330.

SCR (Sustainable Consumption Roundtable), (2006). I will if you will. Towards sustainable consumption. Available at: http://www.sdcommission.org.uk/publications/downloads/I_Will_If_You_Will.pdf. Accessed on August 17, 2010.

Selsky, J. W., & Parker, B. (2005). Cross-sector partnerships to address social issues: Challenges to theory and practice. Journal of Management, 31, 849–873.

Spaargaren, G. (2003). Sustainable consumption: A theoretical and environmental policy perspective. Society and Natural Resources, 16, 687–701.

Stanley, D. J., Meyer, J. P., & Topolnytsky, L. (2005). Employee cynicism and resistance to organizational change. Journal of Business and Psychology, 19, 429–459.

Stern, P. (2000). Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 56, 407–424.

Tetrault Sirsly, C.-A., & Lamertz, K. (2008). When does a corporate social responsibility initiative provide a first mover advantage? Business Society, 47, 343–369.

Thøgersen, J. (1999). Spillover processes in the development of a sustainable consumption pattern. Journal of Economic Psychology, 20, 53–81.

Thøgersen, J., & Ölander, F. (2003). Spillover of environment-friendly consumer behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 23, 225–236.

UBA. (2008). Umweltbewusstsein in Deutschland 2008. Ergebnisse einer repräsentativen Bevölkerungsumfrage. Berlin: Umweltbundesamt (Federal Environment Agency).

UNCED. (1992). Agenda 21. Rio de Janeiro: United Nations Conference on Environment and Development

Unilever. (2010). Available at: http://www.unilever.com/sustainability/people/employees/. Accessed on August 17, 2010.

Vogel, D. (2005). The market for virtue. The potential and limits of corporate social responsibility. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institute Press.

Warde, A. (2005). Consumption and theories of practice. Journal of Consumer Culture, 5, 131–153.

WBCSD. (2008). Sustainable consumption. Trends and facts. From a business perspective. Conches Geneva: World Business Council for Sustainable Development.

WCED (World Commission on Environment and Development). (1987). Our common future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

WHO. (2009). Milestones in health promotion. Statements from global conferences. Geneva: WHO Press. Available at: http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/Milestones_Health_Promotion_05022010.pdf. Accessed on August 17, 2010.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to two anonymous reviewers and the editors whose valuable comments have improved the paper substantially.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Muster, V. Companies Promoting Sustainable Consumption of Employees. J Consum Policy 34, 161–174 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-010-9143-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-010-9143-4