Abstract

Social contractarians commonly take social contracts to be solely hypothetical and refrain from elaborating on the factors that influence the feasibility of the formation of social contracts. In contrast, this paper aims at providing a discussion of the conditions affecting the feasibility of social contracts. I argue that the more aligned the preferences of group members for public goods are, the more the individuals share similar social norms, and the smaller the group is the more feasible a genuine social contract becomes. I provide evidence in support of my contention from the medieval Hanseatic League. At the Hanseatic Kontor in Novgorod, one of the four major trading posts of the Hanseatic League in cities outside of Germany, German merchants agreed to live under the rule of a constitution that gave rise to a political authority for the Kontor society.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

According to modern versions of the social contract theory of government (Buchanan and Tullock 1962; Buchanan 1975; Rawls 1971), all members of a society agree to form a government that allows them to engage in higher levels of social cooperation by alleviating the problem of public goods provision (Kalt 1981, 577–583). Given that neither existing nor historical state governments resulted from the unanimous consent of all their society’s members, “contemporary contractarians do not argue for the historical reality of a primordial social contract” (Heckathorn and Maser 1987, 144). They regard the social contract as nonhistorical, mythical or hypothetical (Buchanan 1972, 27–28; Buchanan 1977, 82 and 139; Dworkin 1973, 501; Rawls 1985, 236). Consequently, social contractarians, for the most part, refrain from discussing the conditions for real social contracts.

Although neither the government of any nation state nor the political leader of any state under a feudal order was ever established through a genuine social contract, we find examples in recorded human history suggesting that social contracts were formed. Leeson (2009) points to pirate crews in the 17th and 18th centuries and argues that their social cooperation was based on social contracts, Anderson and Hill (2004, 124–128) discuss social contracts of 19th century wagon trains headed towards California, and Skarbek (2011) elaborates on constitutions of contemporary prison gangs. I provide here an example from the medieval Hanseatic League maintaining that the Kontor in Novgorod (Russia), an autonomous trading post of the Hanseatic League, was ruled based on a social contract.Footnote 1 While arguing against the mythical character of the social contract, Leeson (2009), following the tradition of social contractarians, limits his analysis to the characteristics of the contract itself and abstains from discussing the conditions influencing the feasibility of a social contract. In contrast, this paper is devoted to a discussion of factors that determine why social contracts come into existence in some cases and not others. I argue that three major conditions make the formation of a social contract more feasible. First, group members have to have relatively similar preferences with respect to public goods to make the cost incurred through the establishment of a political authority worthwhile. Second, members of society have to share some common social norms to facilitate the deliberations of and agreement to a social contract. Third, the smaller the group the lower are decision-making and monitoring costs, making a unanimous agreement more feasible.

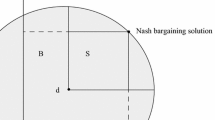

The analysis of factors contributing to the feasibility of social contracts is logically prior to the analytical investigation of the characteristics of the social contract itself. However, using the analytical device of a setting behind a veil of uncertainty (Buchanan and Tullock 1962) or ignorance (Rawls 1971) as the starting point for deliberations at the constitutional stage, social contractarians do not pay a lot of attention to the prevailing conditions of societies that contribute to the feasibility of genuine social contracts.Footnote 2 Although they are aware of the relevance of those conditions, social contractarians discuss them only in passing and quickly move on to the constitutional stage. Buchanan and Tullock provide an illustrative example of this procedure when stating that

(.) our analysis of the constitution-making process has little relevance for a society that is characterized by a sharp cleavage of the population into distinguishable social classes or separate racial, religious, or ethnic groupings sufficient to encourage the formation of predictable political coalitions and in which one of these coalitions has a clearly advantageous position at the constitutional stage (Buchanan and Tullock 1962, 76).

Buchanan and Tullock acknowledge the relevancy of pre-constitutional conditions of the society under consideration, but in the next paragraph provide an argument for why they do not base their constitutional analysis on an investigation of the conditions preceding the social contract:

This qualification should not be overemphasized, however. The requisite equality mentioned above can be secured in social groupings containing widely diverse groups and classes. So long as some mobility among groups is guaranteed, coalitions will tend to be impermanent. The individual calculus of constitutional choice presented here breaks down fully only in those groups where no real constitution is possible under democratic forms, that is to say, only for those groups which do not effectively form a ‘society’ (Buchanan and Tullock 1962, 76–77).

If the only condition for a social contract to be formed was the existence of a ‘society’, it would be striking that over the course of the history of human societies the realization of a social contract has been so rare an event. The present analysis of the conditions conducive to the formation of social contracts helps to explain the apparent contradiction.

In light of the claimed mythical character of the social contract, opponents of the social contract approach provide alternative perspectives on the formation, stability, and meaning of constitutions. Heckathorn and Maser (1987, 144–145) regard constitutions as explicit social contracts, though not necessarily based on unanimous consent. But they maintain that real constitutions are the result of incremental processes and therefore they consider the unanimous one-shot social contract to be a myth (Heckathorn and Maser 1987, 145). Going a step further and rejecting the notion of constitutions as contracts, Hardin (1989) and Ordeshook (1992, 2002) regard constitutions as conventions that allow members of society to coordinate on one particular of many possible outcomes. Accordingly, Hardin (1989, 109) states that “a constitution is clearly like a convention in the strategic sense; it may not give you the best of all results, but it gives you the best you can expect given that almost everyone else is following it.” Also breaking with the notion of constitutions as contracts, Voigt (1999) maintains that a constitution is best understood as being based on and backed by spontaneously arisen institutions. According to Voigt, instead of being conventions themselves, constitutions rest and ultimately depend for their effectiveness on self-enforcing informal institutions, among them conventions (1999, 287). A constitution is thus not a society’s most fundamental institution (Voigt 1999, 285).

Siding with the contemporary social contractarians but breaking with their notion of social contracts as myths, I argue that a social contract, as a society’s most fundamental contractual arrangement that gives rise to a novel political order, can be formed under certain circumstances. I provide evidence for my contention from a Kontor of the medieval Hanseatic League. German merchants of the Hanseatic League frequented four Kontore, trading posts in foreign cities, which were situated in Bergen, Novgorod, London, and Bruges.Footnote 3 The Kontore were to some degree independent from the councils of the hometowns of the merchants, independent in their internal organization from the foreign local authorities, and self-governed by the German merchants in residence based on the Kontore’s constitutions (Henn 2008; Schubert 2002a). I focus my discussion on the hanseatic Kontor in Novgorod, which was the most autonomous of the four.

Section 2 provides a brief introduction to the Hanseatic League and its Kontore and argues that the political organization of the Kontor in Novgorod was based on a social contract. Section 3 discusses the general conditions conducive to the creation of a social contract and analyzes the conditions prevailing in the context of the Kontor in Novgorod. Section 4 discusses the influence of existing political authorities on the formation of a social contract. Section 5 provides concluding remarks.

2 The Hanseatic League’s Kontor in Novgorod: a genuine social contract

The Hanseatic League grew successful during the commercial revolution of the Middle Ages (Dollinger 1970; De Roover 1963, 105–115; Lopez 1971, 113–119). The Hanseatic League was an association first of merchants and later of cities, whose members had an interest in inter-city and international trade. The League existed for about 500 years from the middle of the 12th century to the middle of the 17th century.Footnote 4 It had a vast impact on international trade especially in the Baltic and Northern Sea regions, fought wars with local and national rulers, and made and overturned kings.Footnote 5

Trading posts in foreign ports that merchants from German cities frequented were one of the constituting elements of the Hanseatic League. Four of the hanseatic foreign trading posts, the Kontore, stood out from other trading posts in terms of significance for the merchants of the Hanseatic League: Novgorod, Bruges, London, and Bergen. The Kontore were the centers of the Hanseatic merchant communities in these foreign ports. The merchants not only stored and traded their goods at the location of the Kontor but organized their social lives around it.Footnote 6 Membership in a Kontor was not conditional on a merchant’s hometown. Merchants from all hanseatic towns could join a Kontor and benefit from the privileges granted by the foreign authorities, such as guarantees of relatively free trade and legal securities.

Founded at the end of the 12th century, the Novgorod Kontor was the oldest of the four Kontore (Johansen 1953, 135). The German merchants were introduced to trade in Novgorod by Scandinavian merchants from the island of Gotland. A group of German merchants, the so-called Gotlandic Community, frequented Gotland from the middle of the 12th century onwards. In the beginning, the Germans lived with the Scandinavians when traveling to Novgorod. But already before the end of the 12th century they built their own quarters in Novgorod, which was frequented by summer and winter travelers from Germany (De Roover 1963, 112).Footnote 7 The German traders mostly brought cloth and other high-end goods from the markets of Western Europe to Novgorod and left with wax, fur and other regional products (Dollinger 1970, 233–236).

In the beginning, the inner organization of the Kontor was independent from direct outside political influence. Neither the Russian rulers nor any individual hanseatic city had control over the Kontor’s organization (Henn 2008, 21; Zeller 2002, 31).Footnote 8 From the end of the 13th century onwards cities belonging to the Hanseatic League were able to influence the affairs at the Kontor in Novgorod and by the middle of the 14th century the cities had de facto control over the Kontor (Schubert 2002a, 80–81; Groth 1999, 4; Ebel 1971, 380–381; Angermann 1989, 238). When the first hanseatic diet, the parliamentary convention of the Hanseatic League (Hansetag), took place in 1356 (Dollinger 1970, 92–97; Henn 2008, 16), the cities also claimed to be the de jure authority of the Kontore. Although the hanseatic diet was held irregularly—general meetings were held 72 times between 1356 and 1480 (Dollinger 1970, 92–93)—and was never attended by representatives of all cities participating in the Hanseatic League, it had considerable control over the affairs of the Kontore.

In order to determine whether the constitution of the Kontor in Novgorod qualifies as a social contract, it is necessary to define the essential characteristics that turn a contract into a social contract and to analyze the constitution of the Novgorod Kontor with respect to this standard. Leeson (2009) lays out three elements that have to be observed for a social contract to be present: First, a social contract has to be based on a written document geared towards the installment of a political authority to foster social cooperation. Although a contract, a written agreement between two people to trade fur for money at a future date does not constitute a social contract since it does not aim at establishing a political authority for the participants of the contractual arrangement. Second, the social contract has to elevate the society out of a state of nature in which no political authority exists. Third, all members of the society for which the social contract is binding have to enter the agreement voluntarily.Footnote 9

2.1 Written document giving rise to the installment of a political authority

The first constitution of the Kontor in Novgorod, also known as Skra, is estimated to have come into existence before the middle of the 13th century (Henn 2008, 19–20; Schlüter 1911b, 8).Footnote 10 The first extant edition is a copy of the original Skra and is estimated to have been created around 1270 (Henn 2008, 19; Schlüter 1911b, 8). Overall, seven different editions of the Skra are extant, drafted between the 13th and the 17th century (Schlüter 1911b). The first Skra contains a preamble and nine articles, applying to all merchants who joined the Kontor in Novgorod. The first sentence of article one of the Skra suggests that its primary goal was to establish a political authority:

As soon as they arrive at the Neva River, summer travelers and winter travelers shall elect one olderman for the court and one olderman for St. Peter who may be from any city. (Schlüter 1911b, 50, author’s translation from the original Middle Low German)Footnote 11

The elected olderman of the court served as highest judge, headed the plenary meetings, the so-called Steven, and represented the Kontor to the outside (Henn 2008, 20).Footnote 12 The olderman of the court thus presided over the legislative and judicial system of the Kontor. The olderman for St. Peter was subordinate to the olderman of the court and had merely administrative duties (Gurland 1913, 28–29).Footnote 13 The plenary meetings served as the Kontor’s legislature, enacting internal rules of the Kontor and trade regulations (Zeller 2002, 31; Gurland 1913, 14–15; Angermann 1989, 238). The oldermen had the right to summon the plenary meetings and the merchants ruled by the Skra had the duty to participate in it. Merchants who did not attend the meetings were fined (Henn 2008, 20).

2.2 Elevation from a state of nature into a situation with a political authority

Prior to the establishment of a political authority through the constitution, there was no official third party that members of the Kontor society could turn to for adjudication in cases of conflict, leaving the merchants in Novgorod in a state of nature. Whereas Russians intruding the rights of Germans on the territory of the Kontor were handed over to the Russian jurisdiction and Germans inflicting harm on Russians were subject to a sentence in the guest court of Novgorod (Rennkamp 1977, 158–160), conflicts within the German group were settled internally (Szeftel 1958, 404). The authorization of the olderman to serve as first among equals in juridical matters for a defined period of time facilitated the settlement of intra-group conflict. The olderman’s authority even extended to ordering death sentences in cases of capital crimes committed by merchants living under the Kontor rule (Henn 2008, 20–21). Article nine of the constitution suggests that for persecutions outside of the Kontor Germans relied on the Russian juridical system. The article mentions that if a merchant left the Kontor without settling his account with his contract partner, a Russian bailiff was sent after the offender, implying that the olderman’s authority ended at the Kontor’s gates (Schlüter 1911b, 66).

2.3 All individuals enter the social contract voluntarily

Merchants who decided to travel to Novgorod did so voluntarily. The fact that all merchants had to adhere to the rules of the Kontor, if they wanted to benefit from the trade privileges granted to the Hanseatic traders and other public goods provided by the Kontor does not allow for the conclusion that some merchants were forced to abide by the rules. The constitution was stored in the church on the premises of the Kontor and the inhabitants of the Kontor could consult it at any time (Zeller 2002, 29; Gurland 1913, 30). The Hanseatic merchants either participated in the creation of the Kontor’s constitution, knew about it when leaving their hometowns and traveling towards Novgorod, or were introduced to it upon arrival at Novgorod.Footnote 14 The merchants therefore had a viable exit option, which, as Lowenberg and Yu (1992) argue, can serve as a perfect substitute for unanimous consent behind the veil of uncertainty and thus guaranteed the voluntariness of the agreement.

The employment contracts between merchant masters and their aides and apprentices were long term. Although the employment contracts applied to the whole period of their master’s journey to and stay in Novgorod, the aides of the merchants were not forced under the rule of the social contract either. They voluntarily joined the merchants and accompanied them to Novgorod. Article five of the constitution mandates that once an aide agreed to work for a master he ‘has the duty to stay with his master in good times as well as in bad times and he can leave his master only if it is the will of both of them’ (Schlüter 1911b, 58, author’s own translation from the original Middle Low German). Article five of the constitution also mandates that a master has to take care of his aide even if the aide suffers from severe illness (Schlüter 1911b, 58). Master and aide therefore appear to have participated as equal parties in the employment contract.

According to the standard applied here the members of the Kontor society lived under the rule of a social contract. Correspondingly, Gurland (1913, 13) observes that for at least the first 100 years, the Kontor in Novgorod, in the middle of the Russian state, formed a small, isolated German State of its own with its own government, its own laws, and its own judiciary.

2.4 Club or government?

Despite being open only to German merchants, the Kontor in Novgorod should not be understood as a club in the economic sense presented by Buchanan (1965) but rather as a voluntary governmental organization. Only few social scientists would maintain that governments are simply large clubs. There appears to be a considerable difference between clubs and governments. As Holcombe (1994, 73) maintains, there is, however, no commonly accepted dividing line between clubs and governments. In part this is the result of differing understandings of what constitutes a government.Footnote 15 Whereas Holcombe (1994) regards coercion as the main characteristic separating governments from clubs, I use the broader definition of government provided by Max Weber. According to Weber government is an organization that holds a ‘monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force in enforcing its order within a given territorial area’ (1947, 154). The term government then includes the structures of government that imply a monopoly of the use of force independent of the government’s origin.Footnote 16 Governments that were formed through a social contract as well as governments that originally resulted from coercion are comprised under this definition, making Weber’s definition more inclusive than a definition of government as a necessarily coercive organization.Footnote 17

The Weberian concept of government allows identifying two main differences separating a club, which is embedded in a larger legal order, from a voluntary organization of government based on a social contract. First, when a conflict between a club and one of its members arises, the two parties can turn to a third party arbitrator. In conflicts between the government and a member of society, on the other hand, no third party arbitrator is available to the opposing parties. If members of a golf club cannot settle a conflict internally, they can proceed to a higher-level adjudication system. Conflicts about unpaid fees, for example, are adjudicated by local courts—or maybe some arbitration agency. Conflicts in the Kontor in Novgorod, on the other hand, were in its entirety settled through the governance structure set up by the social contract. There was no third party available. Second, clubs do not pertain to all aspects of an individual’s social life. Club members only set up rules and according enforcement mechanisms for specific aspects of the members’ lives. A tennis club can assure that its members take proper care of the courts but it does not, for example, adjudicate in the case of physical conflict between two club members. A government is potentially pervasive in that conflicts arising in all kinds of social interactions can be subject to settlement through the set up system of adjudication. The political authority of the Kontor in Novgorod, the olderman, was authorized to settle any conflict independent of its nature. Therefore, according to the functional definition of government employed here, the Kontor, although based on a voluntary agreement, is controlled by a political authority that qualifies as government.Footnote 18

3 Three conditions conducive to the formation of social contracts

The fact that social contracts did not give rise to the political structures of modern nation states or states as part of feudal orders should not make us throw out the social contract concept. Alternative forms of governmental organization are possible. As Vincent Ostrom puts it, “we need not think of ‘government’ or ‘governance’ as something provided by the state alone. Families, voluntary associations, villages, and other forms of human associations all involve some form of self-government” (Aligica and Boettke 2009, 146, interview with Vincent Ostrom). Social contracts then potentially lead to structures of governance including a political authority that differ greatly from the nation states that we encounter in recent human history. Besides the merchants of the Hanseatic League other groups ruled by a political authority based on constitutions can be found in history, such as criminal organizations (see, for instance, Skarbek (2011); Leeson (2007b, 2009)) or 19th century wagon trains on their way to California (Anderson and Hill 2004). The examples suggest that there is no reason to either abolish the concept of the social contract or to water it down by allowing for conceptual unanimity. Under what conditions then can we expect to observe the formation of genuine social contracts? I identify three conditions that determine why some societies are able to form a social contract while others are not: aligned preferences for public goods, the preexistence of similar social norms, and a small group size.

3.1 Public goods

In the presence of goods that cannot be provided for efficiently by individual initiative, members of society may be willing to consent to an agreement enforceable by physical force in order to solve the free riding problem and realize benefits from the government provision of public goods (Olson 1965, 98). Members of a given society, however, value bundles of public goods differently. Differing appraisements of public goods include, for instance, differences in valuation with respect to the kinds of public goods and the quantities of public goods provided. The more similar the desires of the members of society for public goods the more feasible is the creation of a social contract, since the less within-group preferences for public goods are heterogeneous the smaller are the expected individual costs from collective decisions concerning public goods. The costs from preference heterogeneity with respect to public goods are similar to the ‘expected external costs’ an individual has to incur from collective action as described by Buchanan and Tullock (1962, 62). Assuming decision-making rules to be fixed, reducing the expected costs of subscribing to the social contract ex ante, homogeneity of preferences for public goods increases the expected individual net gains from the provision of public goods. Empirical findings support this hypothesis. Preference heterogeneity for public goods, approximated by ethno-linguistic fractionalization, appears to decrease the quality of the public good provision (Alesina et al. 1999, 1263, 2003, 172–175; La Porta et al. 1999, 253; Desmet et al. 2009, 15–17).

The pre-selected members of the Kontor society in Novgorod shared preferences for a number of public goods, three of which stood out. First, a judicial system protecting the merchants from predation occurring within the Kontor was established. Rules, regulations and their enforcement fostered peaceful interaction and social cooperation among the German merchants, keeping the level of private predation low. The Russian authorities in Novgorod did neither enforce contracts nor adjudicate conflicts between two German parties. Every conflict between Germans had to be presented to the olderman (Henn 2008, 20). The olderman was given the authority to initiate the prosecution of and impose punishments, including capital punishments, on delinquents (Henn 2008, 20–21) for whom a prison was available on the Kontor’s premises (Schubert 2002b, 15). The social contract did thus give rise to a system allowing for adjudication between Germans according to the rules they were accustomed to. The established legal system had to a considerable degree public good character as it equally applied to every merchant under the rule of the Kontor and the consumption of services provided by the legal system by one merchant did not affect the facility of other merchants to benefit from its presence.

Further, the olderman was effectively constrained and the extent of public predation therefore limited. The olderman’s term was limited to the period of the stay of either the summer or winter travelers. The term limit reduced the relative attractiveness of opportunistic behavior for the primus inter pares. Reelection could be denied to an olderman who engaged in self-dealings and, more importantly, the immediate returns from policy changes in his favor weighed relatively little compared to the returns from being a respected member of the merchant community. In fact, article 1 of the first constitution of the Kontor not only posits that the elected olderman may chose 4 assistants from among the merchant population but also determines a fine for those who refuse to accept their post (Schlüter 1911b, 50). The explicit statement of a fine for refusing to take over a political office suggests that the advantages of being the olderman were so insignificant that an olderman was not in the position to provide considerable benefits to his political partners. This indicates that opportunism by public officials was effectively deterred.

Second, protection against attacks from outside invaders was provided by the Kontor. The privileges granted to Hanseatic merchants by the local authorities potentially caused grief to the Russian population. Although the Russian authorities officially guaranteed protection for the German merchants, the merchants were anxious to protect themselves from outside attacks by the Russian population. The Kontor was protected by a high wooden fence and guards armed with dogs provided for by the merchants (Schubert 2002a, 30). Furthermore, the stone-built church in the middle of the Kontor served as communal storage room for the most valuable goods. Overnight the church itself was watched by two guards who stayed in the church. The guards had to be employed by different merchants and could neither be friends with nor related to one another in order to reduce the chance of collaboration between them to steal from the goods stored in the church (Schubert 2002b, 15).

Third, the merchants had a common interest in trade, and the governance structure of the Kontor allowed for better access to trade-fostering privileges granted by the Russian authorities. Negotiations concerning the privileges were more promising the more merchants participated in them. Collectively acting through their political authority—the olderman was in charge of the negotiations with the Russian authorities—the German merchants were able to achieve more extensive privileges than each merchant would have individually (Johansen 1953, 137; Schubert 2002a, 80). The Kontor society of German merchants negotiated its specific privileges in the broader context of existing trade agreements between Gotlandic and German merchants on the one side and Russian authorities on the other side dating as far back as 1189 (Goetz 1916, 4). Participants in the agreement of 1189 on the non-Russian side were the German merchants who traveled to Novgorod via Gotland, Gotlandic merchants and all merchants of ‘Latin’ origin, separating Roman Catholic foreign traders from the Russian Orthodox domestic population. On the side of the Russians the Prince of Novgorod, the two highest public officials of Novgorod, and the Novgorod parliament, the so-called Vece, were mentioned as parties to the treaty (Goetz 1916, 16–21).Footnote 19 Constructed as an agreement of mutual privileges, foreign merchants were granted fair trials in cases of conflict and protection during their travels in foreign territories (Goetz 1916, 9–11).Footnote 20

Although the group of merchants profited from the provision of goods that were neither perfectly private nor perfectly public since they were only available to the members of the Kontor, for the reasons elaborated on in Sect. 2.4 it would be misleading to characterize the arrangement as a club. The Kontor should also not be mistaken for a business enterprise. In contrast, pirate crews (Leeson 2007b, 2009), prison gangs (Skarbek forthcoming), and members of wagon trains (Anderson and Hill 2004, 124–128) formed social contracts that gave rise to political authorities in order to engage in ventures as organizational units, pursuing one overarching goal. These structures are more firm-like than the Kontor society. Pirates, for instance, aimed at profit maximization as a crew and shared the booty equally among their members (Leeson 2007b, 2009). Whereas for merchants as well as for pirates the social contract mitigated problems of governance, the situation in the Kontor of Novgorod appears to genuinely depict a political arrangement more so than the corporate situation on board of a pirate ship. Members of the pirate firm aimed at solving problems of governance in order to increase the profit of the joint enterprise. The merchants of the Kontor aimed at solving the problems of governance to conduct their businesses individually. Because of their common interest in trade the merchants shared desires for the services provided by the Kontor in its function as ‘productive state’, to use a term coined by Buchanan (1975, 88–90). But outside of independent partnerships between individual merchants, the German merchants did not share profits with their fellow merchants who also traded in Novgorod.

3.2 Social norms

Social contract approaches such as the ones to be found in Buchanan and Tullock (1962), Buchanan (1975) and Bush (1972) start from positions in which norms for social interaction are assumed to be absent. In reality, however, these asocial conditions are commonly not fulfilled. Man is almost never completely isolated and therefore institutions provide some order, even if very limited, to human interactions (Hayek 1988, 12). In order to make deliberations possible, some norms for social interaction have to precede the elaboration of the social contract itself.Footnote 21 Otherwise discussions on the constitutional stage appear to be impossible. Similarly, Voigt (1999, 287) argues that spontaneously arisen self-enforcing institutions and shared moral norms have to preexist to make the establishment of an effective constitution feasible.Footnote 22 Ultimately, Voigt (1999, 292) considers only ‘internal institutions’, i.e. non-governmental institutions, to be capable of effectively fostering social cooperation by constraining the member of society who, based on a comparative in violence, formed the government. In contrast, I maintain that shared existing social norms allow for the formation of a deliberate voluntary social contract that gives rise to a government. The social contract then potentially has a considerable effect on the political organization of the society in question.

The more members of society share in the social norms the more feasible a social contract is. First, the more diverse the existing social norms are the less individuals are inclined to submit themselves under one overarching political authority, because for each individual it is more likely that the established set of rules will not match the social norms the individual is accustomed to. Second, following Boettke et al. (2008), the formal institutions, i.e. in our case the social contract, imposed on society have to fit the preexisting underlying social norms to a considerable extent; otherwise they do not ‘stick’.Footnote 23 Since social norms are in part only tacitly known by individuals, unanimity when signing a social contract does not guarantee institutional congruence between the social contract and antecedent institutions. However, the more the members of society adhere to the same informal institutions the more feasible the creation of a social contract, which corresponds to the multitude of underlying social norms, becomes.

Acknowledging that some rules for social interaction have to precede the social contract does not imply that the social contract becomes obsolete. Social norms do not give rise to a political authority whose function as the ‘productive state’ enables the members of society to benefit from the efficient provision of public goods otherwise unattainable. The implementation of a political authority in addition to the existing structure of norms can therefore be beneficial for each member of a society.Footnote 24

The group of German merchants in Novgorod was relatively homogenous with respect to the social norms they were accustomed to. First, the commercial norms common among the German merchants traveling to Novgorod evolved from the practices of German traders that frequented the Baltic Sea even before the foundation of Lübeck in 1159 (Ebel 1950, 12, 1954, 1, 1971, 131). These commercial practices were spread throughout the Baltic area, known to the merchants, and implicitly agreed upon if no explicit changes were made. Besides norms pertaining to business practices they most likely had similar views on what is right and wrong and shared norms of interaction during social events. Second, the German merchants spoke the same language, Middle Low German, which was wide-spread throughout northern Europe during the High and Late Middle Ages, separating the Germans from the Russian speaking native population of Novgorod. Knowledge of the same language potentially fostered coordination between the parties, facilitated agreement over rules, and allowed for rapid settlement in cases of conflict. Third, the only building made of stone on the premises of the Kontor, the church of St. Peter, was not only the spatial but also the spiritual center of the Kontor. Originating from the territories of the Holy Roman Empire, the German merchants were all Roman Catholic Christians. Their religion additionally separated them from the Russian inhabitants of Novgorod who were followers of the Russian Orthodox Church. The importance of the merchants’ religion mirrors in the constitution in article three:

Nobody shall bring a priest to Novgorod at the expense of St. Peter except for the summer travelers and the winter travelers. He, who brings another priest to Novgorod, shall bring him at his own expense. (Schlüter 1911b, 54, author’s own translation from the original Middle Low German.)

The Priest of St. Peter was maintained by the funds that each inhabitant had to contribute to according to article nine of the constitution, which regulated the dues for joining the Kontor and renting a house on its premises (Schlüter 1911b, 64). The observed method of financing the Roman Catholic priest suggests that the merchants were homogenous with respect to religion not only on paper but also in practice.

3.3 Group size

The smaller the group the more likely it is for a social contract to be created.Footnote 25 Three factors in particular appear to make a social contract less feasible for larger groups than for smaller ones. Holding the degree of heterogeneity with respect to shared social norms and preferences for public goods constant, increases in group size make a social contract less feasible by increasing decision making costs, problems of free riding, and enforcement costs. First, it is more costly to commit to a social contract the larger the group of participants is because of higher decision-making costs as described by Buchanan and Tullock (1962, 65–66). Both finding a unanimous agreement on the constitutional stage and making decisions on the post-constitutional stage, given some rule for collective decision making that determines what proportion of the members of society has to agree to a decision, imply higher expected decision-making costs for the individual the larger the group is. Second, the larger the group, the more costly it is to control the problem of free-riding as it becomes more costly to ensure through centrally organized monitoring that each individual contributes to the provision of public goods. The effect of group size on free riding is, however, still subject to discussion. A considerable body of theory suggests that except for quite small groups the free-riding problem is pervasive and contributions to public goods inefficiently low (Olson 1965, 2; Hardin 1968). In contrast, there is experimental evidence that suggests that the level of voluntary contribution to public goods do not decrease with increases in group size (Isaac and Walker 1988; Isaac et al. 1994; Carpenter 2007). Third, in a larger group monitoring and enforcing of the implemented rules is more costly. An increase in the group size necessitates an increase in the resources devoted to policing per member of society.

Both summer and winter travelers represented a group of approximately 150 to 200 merchants who lived in the Kontor during different periods of the year. With each of the merchants commonly bringing 2 aides and potentially an apprentice, the group size of the Germans in Novgorod ranged from about 600 to 800 (Schubert 2002b, 14). The size of the group allowed all of the merchants to take part in the election of the olderman and to be physically present at the plenary meetings, the Steven, during their stay at the Kontor. Similar to the pirate groups of usually around 80 to 250 men (Leeson 2009), the number of merchants who took part in the social contract was thus relatively small. The decision-making costs, the costs of ensuring that every member explicitly agreed to be bound by the rules, the monitoring costs, and the policing costs were therefore relatively low.

Further, making a social contract more likely was the close proximity of the merchants to one another. The merchants traveled to Novgorod together and shared the Kontor’s property as domicile. Proximity reduces the communication and information sharing costs, making collective action, monitoring of the members’ behavior, and enforcement of the rules less costly. The creation of a social contract would have been less likely, for example, in the case of a rural community in which individual members live relatively far apart from one another.

4 The role of existing political authorities

The concept of a social contract used here rules out situations in which a political authority is already in place. It is, however, possible that the political authority as a member of the society under investigation also voluntarily agrees to subjugate itself under the rule of the social contract, allowing for an alternative political authority to arise.

Nonetheless the presence of a political authority tends to make the formation of a social contract less feasible for at least two reasons. First, if the existing ruler or ruling group enjoys certain privileges, the political authority has an incentive to employ resources to conserve the existing government structure. Second, depending on the nature of the existing political authority, all members of society are potentially satisfied with the existing regime if it enhances social cooperation by providing protection from private predation and by engaging itself only in moderate levels of public predation.

The relationship between the Kontor in Novgorod and the Hanseatic League exemplifies how the influence of a political authority, in this case an outside authority, can affect the structure of governance of a society. In the late 12th and throughout most of the 13th century the Kontor in Novgorod was autonomous and independent in its governance structure from the home towns of the residing merchants. The relationship between the Kontor and the cities of the Hanseatic League, however, changed considerably over time. The Kontor started losing its independence around the turn to the 14th century to the cities of the Hanseatic League; especially Lübeck, Visby, Dorpat, and Reval (Schubert 2002a, 80–81; Groth 1999, 4; Ebel 1971, 380–381; Angermann 1989, 238). The change of the influence of established outside political authorities mirrors in the different editions of the Kontor’s constitution. The first copy from around 1270 of the original constitution from before 1250 does not include any reference to city councils as appellate courts. One of the major differences of the second known edition of the constitution from 1295 (Schlüter 1911b, 18) is the inclusion of the city council of Lübeck as appellate court for the Kontor (Schlüter 1911a, 27–28). With the next known edition of the Kontor’s constitution of 1325 (Schlüter 1911b, 21), the influence of Lübeck and other cities on the organization of the Kontor becomes more pervasive. The city councils of Visby and Lübeck are designated to serve as an appellate court (Schlüter 1911a, 33). According to the fourth known edition of the Kontor’s constitution from roughly the middle of the 14th century (Schlüter 1911b, 29), the olderman is no longer elected by the merchants who stay at the Kontor but by representatives from Lübeck and Visby (Schlüter 1911a, 37).Footnote 26 The constitution of the Kontor over time thus lost its character as a social contract, since in its later days it did not lead to the establishment of an independent political authority anymore but rather described some rights of existing political authorities, in this case the city councils of the Hanseatic cities of Lübeck and Visby.

5 Conclusion

Three remarks are warranted. First, social contracts are not mythical and my analysis of the conditions conducive to the formation of social contracts helps to understand why social contracts get formed under some circumstances and not others. As a historical example the formation of a social contract at the Kontor of the Hanseatic League in Novgorod suggests that similar preferences for public goods, homogenous social norms, and a small group size facilitate the creation of social contracts.

Second, in all societies the conditions related to public goods, social norms, and group size are fulfilled to some degree. My analysis does not allow stating precisely to what extent the conditions have to be fulfilled to make social contracts feasible. But we can say something about the substitutability of the three conditions. They are neither perfect substitutes nor perfect complements. Similar to imperfectly substitutable inputs to a production process, meeting one condition to a relative large degree can compensate for the relative lack of another condition. A relatively large group size, for instance, can potentially be compensated by relatively homogenous preferences for the provision of public goods. Similarly, relatively diverse preexisting social norms can be compensated by a small group size that allows for low-cost monitoring and enforcement. However, since the conditions are only imperfect substitutes, for instance the degree of heterogeneity with respect to the preferences for public goods can reach a level that cannot be compensated by a small group size or social norms.

Third, the degrees to which the conditions discussed are to be found in a certain society are not independent of one another but their separation rather is a useful way of thinking about the circumstances under which social contracts might be formed. A small group of individuals, for instance, is likely to share social norms to a larger extent than a large group. Individuals who are accustomed to relatively similar social norms tend to share desires for certain public goods. Assuming for analytical purposes that the conditions are independent allows for a discussion of the effects of changes in any one of the conditions while holding other factors constant.

Notes

Kontore throughout the text refers to the plural of Kontor.

Besides the four major Kontore the Hanseatic League had additional trading posts in foreign cities. The Kontore, however, represented the most important trading posts of the Hanseatic League. Since historians paid considerably more attention to the structure of the Kontore than to other trading posts, we have a fairly good understanding of the Kontore, whereas relatively little is known about other trading posts.

For a general introduction to the Hanseatic League see Dollinger (1970).

This holds especially true for Bergen and Novgorod, where the merchants lived on the Kontor’s premises. In London and in Bruges, the merchants did not live on the site of the Kontor and the German merchants intermingled with the native population.

Summer travelers arrived in Novgorod in spring after the ice gave the seaway to Novgorod free and left just before the ice made the voyage impossible. Winter travelers accordingly arrived in Novgorod shortly before the ice covered the passage to Novgorod.

Although officially a princedom, Novgorod was de facto governed by an oligarchic class of so-called Boyars. For details on Novgorod’s political system, see for example Johansen (1953).

The second condition concerning the absence of any political authority appears to be non-binding. It is imaginable that although a political authority is present all members of a society, including the political authority, agree to a social contract giving rise to a new political authority. A preexisting political authority therefore does not per se eliminate the possibility of designing a social contract. For a discussion of the influence of an existing political authority on the formation of a social contract see Sect. 4.

Kattinger (1999, 220) estimates that the first Skra was written around the year 1192.

Schlüter (1911b) provides the original text of seven versions of the constitution of the Kontor in Novgorod.

The preamble of the first Skra contains a reference to an approval of the Skra by ‘the wisest of all German cities’ (Schlüter 1911b, 58, author’s own translation from the original Middle Low German). The reference to the ‘wisest of all cities’ suggests that the extent copy was composed around 1270 in Visby, where merchants from several German cities formed a community (Schlüter 1911b, 8), and not that it was virtually approved by representatives from the wisest cities when it was first composed in the first half of the 13th century (Kattinger 1999, 217–219; Rennkamp 1977, 123).

Throughout the paper all references to the olderman of the Kontor refer to the ‘olderman of the court’.

See Holcombe (1994, 80–89) for a discussion of different definitions of government.

I consider the term ‘legitimate’ in Weber’s definition of government to indicate that despite the government’s official monopoly other members of society engage in physical force, which is then accordingly deemed ‘illegitimate’ by the established government.

Note that governments which were originally based on unanimous consent can turn into organizations that predate on those who initially consented to their creation. See Wagner (2007, 35) and the literature cited there for a discussion of the possibility that over time governments, which were originally created by unanimous consent, secure a dominant position in society not intended by those who participated in its creation.

If, as preferred by Holcombe (1994), the presence of coercive measures is considered to separate governments from clubs, due to its voluntary nature the Kontor society would have to be regarded as a club with a club leadership, which has extensive powers commonly associated with the characteristics of governments.

In the next known German-Russian trade agreement from 1259 the first mentioned participant on the German side is a representative from the city of Lübeck, followed by a representative of the German merchants frequenting Novgorod via Gotland and a representative of the Gotlandic merchants (Goetz 1916, 74). This change in the signers of the contract stands for the increase in influence of the Hanseatic Cities, especially Lübeck, over the affairs of Germans in Novgorod as elaborated on in Sect. 4.

Although the trade agreements between Russians and Germans and people from Gotland granted mutual freedoms, they were de facto privileges for the Germans (Goetz 1916, 68). The Russians’ level of international trade decreased from a very modest level in the 12th century to an even lower level during the 13th and 14th centuries, nearly vanishing completely (Johansen 1953, 130–131).

I understand norms to encompass all ‘rules of the game’ for social cooperation that are not provided for by a political authority. Whereby norms can emerge spontaneously through human interaction or be designed by individuals deliberately.

Voigt (1999) does not elaborate on further conditions for the establishment of constitutions.

Williamson (2009) provides empirical evidence for the claim that formal institutions are only effective when successfully embedded in a set of informal institutions.

For a discussion of the conditions under which either anarchy or the presence of a government is the efficient form of social organization for individual members of a society, see Leeson (2007a).

I assume here that the group is large enough to be able to produce public goods efficiently.

Without referring to any particular time period Rybina (2002, 240) states that the Kontor of Novgorod was dependent on the cities and problems concerning all businesses of the Kontor were discussed and resolved by the Hanseatic diet and the city diets of the Livland cities (especially Dorpat and Reval). If Rybina makes this statement also for the period before the first Hanseatic Diet in 1356, Rybina represents an exceptional opinion concerning the degree of independence of the Kontore. The development of the constitution itself suggests that the Kontore lost their independence over time and other historians argue that there was a time in which the Kontore were self-governed free of direct influence from any of the governing institutions of the Hanseatic cities (Gurland 1913; Zeller 2002; Angermann 1989, Szeftel 1958, 404; Johansen 1953, 138). Furthermore, Rybina (2001, 307), contradicting her dependence thesis, stresses the uniqueness of the isolated and closed settlement of the Germans in Novgorod.

References

Alesina, A., Baqir, R., & Easterly, W. (1999). Public goods and ethnic divisions. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(4), 1243–1284.

Alesina, A., Devleeschauwer, A., Easterly, W., Kurlat, S., & Wacziarg, R. (2003). Fractionalization. Journal of Economic Growth, 8(2), 155–194.

Aligica, P. D., & Boettke, P. J. (2009). Challenging institutional analysis and development. London: Routledge.

Anderson, T. L., & Hill, P. J. (2004). The Not so wild, wild west: Property rights on the frontier. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Angermann, N. (1989). Nowgorod—das Kontor im Osten. In J. Bracker, V. Henn, & R. Postel (Eds.), Die Hanse. Lebenswirklichkeit und Mythos (pp. 234–241). Lübeck: Schmidt-Römhild.

Boettke, P. J., Coyne, C. J., & Leeson, P. T. (2008). Institutional stickiness and the new development economics. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 67(2), 331–358.

Buchanan, J. M. (1965). An economic theory of clubs. Economica, 32(125), 1–14.

Buchanan, J. M. (1972). Before public choice. In G. Tullock (Ed.), Publications in the theory of anarchy (pp. 27–37). Blacksburg: Center for the Study of Public Choice.

Buchanan, J. M. (1975). The limits of liberty. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Buchanan, J. M. (1977). Freedom in constitutional contract. London: College Station.

Buchanan, J. M., & Tullock, G. (1962). The calculus of consent. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

Bush, W. C. (1972). Individual welfare in anarchy. In G. Tullock (Ed.), Explorations in the theory of anarchy (pp. 5–18). Blacksburg: Center for the Study of Public Choice.

Carpenter, J. P. (2007). Punishing free-riders: How group size affects mutual monitoring and the provision of public goods. Games and Economic Behavior, 60, 31–51.

De Roover, R. (1963). The organization of trade. In M. M. Postan, E. E. Rich, & E. Miller (Eds.), The Cambridge economic history of europe (Vol. III). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Desmet, K., Ortuno-Ortin, I., & Wacziarg, R. (2009). The political economy of ethnolinguistic cleavages. NBER Working Paper No. 15360.

Dollinger, P. (1970). The German Hansa. First published in 1964. (D. S. Ault & S. H. Steinberg, Trans.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Dworkin, R. (1973). The original position. The University of Chicago Law Review, 40(3), 500–533.

Ebel, W. (1950). Forschungen zur Geschichte des lübischen Rechts. I. Teil. Lübeck: Schmidt-Römhild.

Ebel, W. (1954). Bürgerliches Rechtsleben zur Hansezeit in Lübecker Ratsurteilen. Göttingen: Musterschmidt.

Ebel, W. (1971). Lübisches Recht. Lübeck: Schmidt-Römhild.

Goetz, L. K. (1916). Deutsch-Russische Handelsverträge des Mittelalters. Hamburg: Friederichsen & Co.

Groth, E. (1999). Das Verhältnis der livländischen Städte zum Novgoroder HanseKontor im 14. Jahrhundert. Hamburg: Baltische Gesellschaft.

Gurland, M. (1913). Der St. Peterhof zu Nowgorod (1361–1494). Innere Hofverhältnisse. Dissertation Göttingen.

Hardin, G. (1968). The tragedy of the commons. Science, 162, 1243–1248.

Hardin, R. (1989). Why a constitution? In B. Grofman & D. Wittman (Eds.), The federalist papers and the new institutionalism (pp. 100–120). New York: Agathon Press.

Hayek, F. A. (1988). The fatal conceit. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Heckathorn, D. D., & Maser, S. M. (1987). Bargaining and constitutional contracts. American Journal of Political Science, 31(1), 142–168.

Henn, V. (2008). Die Hansekontore und ihre Ordnungen. In A. Cordes (Ed.), Hansisches und hansestädtisches Recht (pp. 15–39). Trier: Porta Alba.

Holcombe, R. G. (1994). The distinction between clubs and governments. In R. G. Holcombe (Ed.), The economic foundations of government (pp. 72–91). New York: New York University Press.

Isaac, M. R., & Walker, J. M. (1988). Group size effects in public goods provision: The voluntary contributions mechanism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 103(1), 179–199.

Isaac, M. R., Walker, J. M., & Williams, A. W. (1994). Group size and the voluntary provision of public goods. Journal of Public Economics, 54, 1–36.

Johansen, P. (1953). Novgorod und die Hanse. In A. von Brandt & W. Koppe (Eds.), Städtewesen und Bürgertum als geschichtliche Kräfte (pp. 121–148). Lübeck: Schmidt-Römhild.

Kalt, J. P. (1981). Public goods and the theory of government. Cato Journal, 1(2), 565–584.

Kattinger, D. (1999). Die Gotländische Genossenschaft. Köln: Böhlau.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1999). The quality of government. Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, 15(1), 222–279.

Leeson, P. T. (2007a). Efficient anarchy. Public Choice, 130(1–2), 41–53.

Leeson, P. T. (2007b). An-arrgh-chy: The law and economics of pirate organization. Journal of Political Economy, 115(6), 1049–1094.

Leeson, P. T. (2009). The calculus of piratical choice: The myth of the myth of the social contract. Public Choice, 139, 443–459.

Lopez, R. S. (1971). The commercial revolution of the middle ages (pp. 950–1350). Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Lowenberg, A. D., & Yu, B. T. (1992). Efficient constitutions formation and maintenance: The role of exit. Constitutional Political Economy, 3(1), 51–72.

Olson, M. (1965). The logic of collective action. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Ordeshook, P. C. (1992). Constitutional stability. Constitutional Political Economy, 3(2), 137–175.

Ordeshook, P. C. (2002). Are ‘Western’ constitutions relevant to anything other than the countries they serve? Constitutional Political Economy, 13(3), 3–24.

Rawls, J. (1971). A theory of justice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Rawls, J. (1985). Justice as fairness: Political not metaphysical. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 14(3), 223–251.

Rennkamp, W. (1977). Studien zum deutsch-russischen Handel bis zum Ende des 13. Jahrhunderts, Nowgorod und Dünagebiet. Bochum: Studienverlag Dr. N. Brockmeyer.

Rybina, E. (2001). “Frühe ‘Joint Ventures.’” Die Beziehungen Novgorods im Ostseeraum. In M. Müller-Wille et al. (Eds.), Novgorod. Das mittelalterliche Zentrum und sein Umland im Norden Russlands, (pp. 291–308). Neumünster.

Rybina, E. (2002). Die hansischen Kaufleute in Novgorod. Ihre Lebensumstände und ihre Beziehungen zu den Einwohnern der Stadt. In R. Hammel-Kiesow (Ed.), Vergleichende Ansätze in der hansischen Geschichtsforschung (pp. 237–245). Trier: Porta Alba.

Schlüter, W. (1911a). Die Nowgoroder Schra in ihrer geschichtlichen Entwicklung vom 13. bis zum 17. Jh. Dorpat: Mattiesen.

Schlüter, W. (1911b). Die Nowgoroder Schra in sieben Fassungen vom XIII. bis XVII. Jahrhundert. Dorpat: Mattiesen.

Schubert, B. (2002a). Hansische Kaufleute im Novgoroder Handelskontor. In N. Angermann & K. Friedland (Eds.), Novgorod. Markt und Kontor der Hanse (pp. 79–95). Köln: Böhlau.

Schubert, E. (2002b). Novgorod, Brügge, Bergen und London: Die Kontore der Hanse. Concilium Medii Aevi, 5, 1–50.

Skarbek, D. (2011). Putting the ‘Con’ into constitutions: The economics of prison gangs. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 26(2), 183–211.

Szeftel, M. (1958). La condition légale des étrangers dans la Russie Novgorodo-Kievienne. Recueils de la Société Jean Bodin, 10, 375–430.

Voigt, S. (1999). Breaking with the notion of social contract: Constitutions as based on spontaneously arisen institutions. Constitutional Political Economy, 10, 283–300.

Wagner, R. E. (2007). Fiscal sociology and the theory of public Finance. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Weber, M. (1947). The theory of social and economic organization. New York: Oxford University Press.

Williamson, C. R. (2009). Informal institutions rule: Institutional arrangements and economic performance. Public Choice, 139(3), 371–387.

Zeller, A. (2002). Der Handel Deutscher Kaufleute im mittelalterlichen Novgorod. Hamburg.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Simon Bilo, Peter Boettke, Nicholas Curott, Harry David, Stewart Dompe, Thomas Hogan, Ole Jürgens, Peter Leeson, William Luther, Adam Martin, Douglas Rogers, David Skarbek, Daniel Smith, Nicholas Snow, Virgil Storr, Elif Uncu, Lawrence White, and participants of the Southern Economics Association Meetings 2009 for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper. The standard disclaimer applies. He gratefully acknowledges generous research support from the Mercatus Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fink, A. Under what conditions may social contracts arise? Evidence from the Hanseatic League. Const Polit Econ 22, 173–190 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-010-9099-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-010-9099-z