Abstract

Mental health and addiction (MHA) related Emergency Department (ED) visits have increased significantly in recent years. Studies identified that a small subgroup of patients constitutes a disproportionally large number of visits. However, there is limited qualitative research exploring the phenomenon from the perspectives of patients who visited ED frequently for MHA reasons, and healthcare providers who provide care to the patients since the overwhelming majority of studies were quantitative based on clinical records. Without input from patients and healthcare providers, policymakers have inadequate information for designing and implementing programs. The purpose of this study was to systematically review the literature of qualitative research on frequent MHA related ED visits. The findings of the review revealed that a lack of community resources and existing community resources not meeting the needs of patients were critical contributing factors for frequent MHA related ED visits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mental health and addiction (MHA) related emergency department (ED) visits have increased in recent decades (Brennan et al., 2014). In response to the continued rise in the number of patients who use ED services for MHA issues, studies have examined the phenomenon, and found a relatively small number of patients with MHA disorders account for a disproportionately large number of ED visits (Lincoln et al., 2016; Meng et al., 2017; Quail et al., 2017). Studies of frequent MHA related ED visits have identified some predictive factors, including schizophrenia disorder (Chaput, Y. J. & Lebel, 2007); personality disorder (Pasic et al., 2005); substance use (Fleury et al., 2015); social and personal stressors (Pasic et al., 2005); and homelessness (Lindamer et al., 2012). The number of MHA related ED visits has also increased among those who do not represent “true” psychiatric emergencies (e.g., acute excitement with psychomotor agitation and self-destructive or suicidal behavior) (Mavrogiorgou et al., 2011) but who use ED as a source of support (Catalano et al., 2003; Chaput et al., 2008). In addition, high rates of readmission and ED visits after discharge reflect difficulties in accessing outpatient care and a lack of community services (Aagaard et al., 2014) However, little is known about this issue and the reasons why patients frequently use ED services, particularly from the perspective of patients who visit the ED frequently, and the healthcare providers who work with these patients. An overwhelming majority of studies on MHA related ED visits utilize quantitative analyses based on data from patient’s health records (Meng et al., 2017; Quail et al., 2017). A lack of input from the patients who frequently visit the ED, and healthcare providers who work with these patients leaves policymakers with inadequate information on program design and implementation of community service programs.

The aim of this study was to systematically review the literature on MHA related ED visits from the perspective of patients who visit ED frequently, and healthcare providers who provide care to these patients.

Methods

Search Strategy

This review followed PRISMA guidelines for reporting systematic reviews (Moher et al., 2009). Search strategies and terms were developed in consultation with a health science librarian and a researcher in the MHA field. Two authors searched six databases: Cochrane, Embase, PubMed, MEDLINE, PsychINFO, and Scopus. Initial searches were done for each concept, and their common synonyms: mental health; addiction; MHA; and ED. Free-text terms and controlled vocabulary terms were subsequently searched.

The inclusion criteria for the current systematic review included (1) participants (patients with MHA disorders who visited ED frequently and healthcare providers) ≥ 18 years old; (2) qualitative or mixed methods study designs; (3) literature published between January 2000 and October 2020. We excluded studies with (1) participants < 18 years old; (2) quantitative methods; (3) non-English language; and (4) non-peer-reviewed publications.

Screening and Selection

Two authors independently screened both titles and abstracts to determine relevance. Full text reviews based on the results of title and abstract screening were conducted by two authors independently. Any disagreements in screening and selection process were resolved through discussion. Articles that met the inclusion criteria proceeded to data extraction and quality appraisal.

Data Extraction and Quality Appraisal

The researchers developed a standardized data extraction protocol to ensure uniformity. For each study, the following data were extracted: authors, country, year of publication, type of study, eligibility criteria, number of participants, types of participants, data collection methods, and findings.

The quality of each study was appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme for qualitative studies (CASP) (CASP, 2018), one of the most widely used tools in the health and social sciences to assess study qualitative rigour (Dalton et al., 2017; Hannes & Macaitis, 2012). CASP assessment is divided into three categories with a possible total score of 16: Section A includes 6 questions that focus on validity and methodology; Section B is comprised of three questions related to ethical issues, data analysis, and findings; Section C investigates the value of the study in regards to the generalization of the findings (CASP, 2018). The studies selected for this review were assigned a quality score out of 16 as follows: low (≤ 9), medium (10–13), and high (≥ 14) quality respectively (Nadelson & Nadelson, 2014). The quality appraisal of each study was assessed by two independent researchers. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Results

Study Selection

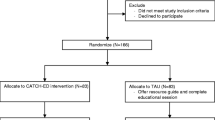

A total of 3175 studies were identified. After duplicates were removed, the title and abstract of the remaining 2426 studies were reviewed. Of the 2426, 34 were determined as meeting initial eligibility. The full text of each article was reviewed, and 17 were chosen for further data extraction and quality appraisal. A PRISMA flow diagram presents all phases of the review process (Fig. 1) (Moher et al., 2009).

Summary of Study Characteristics

A majority (14) of selected studies were published between 2010 and 2020, and 3 were from 2000 to 2010. Of the 17 studies, 7 were published by Canadian researchers, 4 were Swedish publications, both the UK and the USA researchers published two studies, and one publication came from Singapore and Denmark respectively (Table 1). Of the total 17 studies, 12 were qualitative and 5 employed mixed methods. There were a total of 12 studies focused exclusively on patient perspectives (Aagaard et al., 2014; Fleury et al., 2019b; Lincoln et al., 2016; McCormack et al., 2015; Olsson & Hansagi, 2001; Parkman et al., 2017a, b; Poremski et al., 2020; Schmidt et al., 2018; Vandyk et al., 2018, 2019; Wise-Harris et al., 2017).Three studies were exclusive to healthcare providers' perspectives (Fleury et al., 2019a; Schmidt et al., 2020a, b, while two studies incorporated both patient and healthcare provider perspectives (Bergmans et al., 2009; Spence et al., 2008).

Overall, of the 17 selected studies, there were a total of 660 patient participants, and 122 healthcare provider participants. Data were collected by conducting one-on-one semi-structured interviews for all patient participants while studies that were healthcare provider focused, utilized supplemented individual interviews with focus groups.

Are ED Visits Inevitable?

Patients came to ED under different circumstances including perceived inevitable situations, seeking mental health services, and/or involuntary visits, or being redirected by others.

Perceived Inevitable Situations

Patients discussed their ED visits as a last resort when seeking help for intolerable conditions, feeling as though their ED visit was unavoidable and the only way to address their urgent needs (Aagaard et al., 2014; Bergmans et al., 2009; Fleury et al., 2019b; Vandyk et al., 2019). For example, some viewed their chronic health conditions, and MHA issues as a threat to their life (e.g., severe mood symptoms, suicidal behaviors), and needed immediate medical attention (Lincoln et al., 2016; Parkman et al., 2017b; Vandyk et al., 2019; Wise-Harris et al., 2017).

Seeking Mental Health Services

Some patients used ED services exclusively to manage their MHA related symptoms, while others cited using ED services as supplemental care to their usual primary care services (Aagaard et al., 2014; Fleury et al., 2019a). Visiting ED due to psychotropic medications related matters has been documented in the literature, such as the inability to pay, refill, mediation adjustment, and to receive long-acting injectable medications (Fleury et al., 2019a; Poremski et al., 2020), while for others the purpose of ED visits was to receive a referral for community services that were otherwise difficult to access (Lincoln et al., 2016; Wise-Harris et al., 2017).

Involuntary ED Visits or Redirected by Others

Some patients were brought to ED by police due to public intoxication, self-endangerment (e.g., suicidal behavior), violent incidents (either as victims or as perpetrators), or public nuisance caused by acute psychotic symptoms (McCormack et al., 2015; Poremski et al., 2020; Vandyk et al., 2019). Other patients reported that their ED visits were redirected or endorsed by their regular care providers or family members despite the availability of community resources (Spence et al., 2008; Wise-Harris et al., 2017).

Perspectives from Healthcare Provider

Healthcare providers viewed that the provision of care in ED is often problematic, as interventions rarely provide solutions, rather they act as a Band-Aid until the patient’s next visit (Bergmans et al., 2009). Patients often have comorbidities, with complex needs beyond what ED can provide, and treatment of patients who frequently visit ED is often inadequate without a wider, integrated community care response (Fleury et al., 2019a).

Lack of Social Support and Housing

Patients with MHA disorders face challenges every day, including housing issues, and lack of social support and social connection. Studies have found that a lack of reliable social networks during crisis, seeking external support, and having a safe and secure place to stay were identified to be contributing factors for ED visits among some patients (Aagaard et al., 2014; Schmidt, et al., 2020a, b).

Seeking Social Support

Schmidt et al., (2020a, b) found that due to limited social support and stigma towards patients with mental health disorders, patients felt isolated in the community. To relieve loneliness, patients visited ED where they could talk and interact with ED staff, where they felt seen and confirmed by ED staff. EDs also provided a refuge for patients to temporarily escape seemingly unmanageable situations (Parkman et al., 2017a; Poremski et al., 2020; Schmidt, et al., 2020a, b). Parkman et al. (2017a) found that patients in a specialized addiction program were more appreciative of the social aspect of activities that the services provided, including making friends and interacting with staff. Vandyk et al. (2018) suggested that social connections were critical to patient success in symptom management including timing and availability, and these social relationships helped stabilize patients’ symptoms prior to accessing the ED.

Feeling Safe and Secure

For patients who did not have a stable home, a secure place to stay, or were homeless, ED was viewed as a safe and secure place where they could voice their needs for a professional approach, such as assurance of privacy and confidentiality (McCormack et al., 2015; Schmidt, et al., 2020a, b). There was an inherent feeling of safety associated with ED visits due to the immediate access to care and helpful staff (Parkman et al., 2017b).

Inadequate Community Resources

Both patients and healthcare providers viewed frequent ED visits as directly tied to the lack of community resources (Spence et al., 2008; Wise-Harris et al., 2017).

Self-management of Symptoms in the Community

Many patients presented with pre-existing conditions, suffering from MHA issues, or sometimes co-occurring with other chronic or acute health problems (Parkman et al., 2017b). Prior to visiting ED, they often experienced a pattern of deteriorating symptoms (Bergmans et al., 2009). In an effort to reduce ED visits, some patients implemented self-management strategies and coping skills, which included negative coping (e.g., substance use or self-harm) and positive coping (e.g., connecting with friends and family) (Vandyk et al., 2019). In an earlier study by Vandyk et al (2018), patients cited work or other volunteer activities as a key coping mechanism as it provided them with a sense of purpose and feelings of normalcy. Utilizing coping skills including participating new therapies and implementing new strategies has been reported to be associated with reduced ED visits among patients (Vandyk et al., 2018). For some, visiting ED only occurred when self-management failed (Vandyk et al., 2018).

Existing Community Resources

Many patients struggled with an array of challenges. However, patients felt existing community supports did not meet their complex needs (Parkman et al., 2017b). Additionally, patients often dealt with other issues simultaneously including unstable housing, poor social relationships, and/or being unemployed (Aagaard et al., 2014; Parkman et al., 2017a, b; Spence et al., 2008; Vandyk et al., 2018). Poremski et al. (2020) found that patients believed ED would allow them to address their needs because someone would listen to their concerns, unlike in outpatient programs.

For existing services, some patients reported the Crisis Line having limited capabilities and usefulness (Vandyk et al., 2018). Another study examined the utilization of a specialized addiction service, and low usage of the services was evidenced (Parkman et al., 2017a). In this study, structural barriers were not found to be the reason for the low utilization, rather patients believed they did not require specialized addiction services for their addiction, and a lack of knowledge on what these services could provide was identified as a factor for the low usage (Parkman et al., 2017a).

Additionally, knowledge deficits of existing community resources were identified among ED staff to be a barrier for patients to access community services, therefore, patients were either not referred or referred to inappropriate community services before discharge from ED (Fleury et al., 2019b). However, Olsson and Hansagi (2001) found that referrals to community mental health services did not prove helpful as patients did not follow-up with these services, nor did they make changes to their help-seeking behavior.

Comprehensive MHA Services Care Required

Parkman et al. (2017b) found that community-based resources were often inadequate, and the lack of positive social support made these resources unappealing. As well, inconsistencies in coordination and continuation with mental health services exasperated the need for patients to visit the ED for mental health related issues (Fleury et al., 2019a). Healthcare providers suggested that in order to provide cohesive care and adequate support, comprehensive care including stable social connections and community services (e.g., learning coping skills via therapies, helping with employment or volunteer activities) needed to be included (Schmidt et al., 2020a, b). In the study by Fleury et al. (2019b), healthcare providers identified several barriers in patients’ symptom management in EDs and communities including ineffective ED management, lack of resources causing long delays in accessing community services, inadequate services during non-business hours, and lack of training among ED staff regarding comorbid conditions among patients. In order to reduce MHA related ED visits, healthcare providers suggested utilizing existing resources more efficiently such as enhancing the quality of relationships with other health systems (e.g., Crisis Centers), and collaborating between MHA services leading to more appropriate referrals outside of ED settings (Fleury et al., 2019b).

Experiences of ED Visits

The experiences of frequent ED visits according to patients and healthcare providers were mostly negative.

Assessment, Discharge, and Consultation

Patients viewed assessments in ED as acting as ‘gatekeepers’, causing concern about whether they were ‘sick enough’ to receive care as a result of past experiences of rejection (Aagaard et al., 2014). Patients also felt that they were discharged without their concerns addressed or before being fully stabilized (Vandyk et al., 2018; Wise-Harris et al., 2017). Patients with addiction issues reported that healthcare providers focused more on their addiction, but their mental health related symptoms were ignored, and they believed that their MHA symptoms should be treated concurrently (Lincoln et al., 2016).

Being Known

As frequent ED visitors, positive experiences were premised on ED staff providing care that met patients’ needs, while negative experiences were related to ED staff assuming the reasons for patients’ ED visit or speaking to patients unprofessionally (Vandyk et al., 2018). Patients felt care suffered once they had been identified as a “frequent flyer” which negatively impacted their ability to seek and find ongoing care (Spence et al., 2008; Wise-Harris et al., 2017).

Stigma, Discrimination, and Unsympathetic Treatment

Patients felt stigmatized, discriminated against, and received unsympathetic treatment because they had MHA issues and repeated ED visits (Wise-Harris et al., 2017). The long waiting time for having an assessment in ED was viewed as evidence of stigmatization, and unsympathetic ED staff made patients feel unwelcome (Wise-Harris et al., 2017). Patients also felt disrespected and receiving sub-optimal care such as short consultation time, being rushed, and judged poorly by healthcare providers (Vandyk et al., 2018).

Problematic Behavior

Disruptive behaviors among patients in ED were documented including aggression and agitation (Bergmans et al., 2009; Spence et al., 2008). Long wait times for assessment, multiple interviews, and confinement in ED were seen as the main causes of patients’ disruptive behaviors (Bergmans et al., 2009; Spence et al., 2008). Healthcare providers expressed that disruptive behavior was associated with the stressful nature of the ED, which increased their frustration with patients, and affected the service and care patients received (Bergmans et al., 2009; Spence et al., 2008).

Interaction with Healthcare Providers

Patients reported that interactions with ED doctors often were positive, however interactions with nurses varied with reported positive (e.g., caring and understanding) and negative (e.g., disrespectful and judgmental) experiences (Bergmans et al., 2009; Olsson & Hansagi, 2001; Vandyk et al., 2018; Wise-Harris et al., 2017). Patients reported that security staff lacked understanding and/or the training to work with patients with MHA issues (Vandyk et al., 2018). Interestingly, before arriving at ED, patients perceived police encounters to be positive and felt as though they were cared for. Conversely, experiences with paramedics who transport patients to the ED were discussed as lacking sensitivity and compassion (Vandyk et al., 2018).

Quality Appraisal

Based on CASP assessment, five out of 17 selected studies were rated as high quality (score received 14–16) (McCormack et al., 2015; Parkman et al., 2017a, b; Schmidt, et al., 2020a, b; Vandyk et al., 2018), in which three studies obtained a full score of 16 (McCormack et al., 2015; Parkman et al., 2017a; Vandyk et al., 2018), nine studies scored in the medium range of quality (score received 10–13) (Bergmans et al., 2009; Fleury et al., 2019b; Lincoln et al., 2016; Poremski et al., 2020; Schmidt et al., 2018, 2020a, b; Spence et al., 2008; Vandyk et al., 2019; Wise-Harris et al., 2017), and three studies earned a score of low quality (score received 8–9) (Aagaard et al., 2014; Fleury et al., 2019a; Olsson & Hansagi, 2001) (Table 1).

Section A in CASP evaluates the validity and methodology. Studies that did not receive full points in this section, showed inadequate discussion of the relationship between researchers and participants, question development/inclusion criteria, failure to consider saturation, and issues with research design (Aagaard et al., 2014; Fleury et al., 2019a; Lincoln et al., 2016; Olsson & Hansagi, 2001; Schmidt et al., 2018, 2020a, b; Spence et al., 2008; Vandyk et al., 2019). Section B in CASP reviews study procedures, methods, and results. Studies lost points for this section due to inadequate discussion of ethics and confidentiality, lack of recruitment information, researcher roles not fully examined, results not explicitly reflecting or supporting themes, rigour in data analysis, and a lack of discussion on data discrepancy (Aagaard et al., 2014; Bergmans et al., 2009; Fleury et al., 2019a, b; Lincoln et al., 2016; Olsson & Hansagi, 2001; Poremski et al., 2020; Schmidt et al., 2018, 2020a, b; Vandyk et al., 2019; Wise-Harris et al., 2017). Section C in CASP assesses the generalizability of research findings. Studies with an insufficient discussion of the implications and transferability of findings received a less perfect score (Aagaard et al., 2014; Lincoln et al., 2016; Olsson & Hansagi, 2001; Poremski et al., 2020; Schmidt et al., 2018, 2020a, b; Vandyk et al., 2019; Wise-Harris et al., 2017).

Discussion

Four major themes were identified in the current review, however, one encompassing theme was evidenced: inadequate community resources and/or existing community resources not meeting the needs of patients. Whether ED visits were inevitable, lack of social support and housing, and their ED experiences were directly or indirectly linked with community resources.

Are ED Visits Inevitable?

In the current reviews, some patients’ ED visits were inevitable due to experiencing acute psychiatric symptoms or combined acute physical and psychiatric conditions (e.g., acute psychosis, suicidal behavior, medical emergency), and thus needed immediate medical attention. However, for patients who presented with non-acute symptoms, or visited EDs due to lack of social support or housing, or lack of mental health services during non-business hours, their needs or issues could be managed in the community. For example, psychotropic medication related issues were identified in several of the studies as a factor for ED visits. These visits often took place during non-business hours, which could easily be addressed by community mental health nurses or mental health workers following up with patients in the community, such as reminding patients about the date of medication refill and injectable medication, and help patients make an appointment with their physician for medication adjustments based on patient’s response to the medication trial. For patients with alcohol intoxication, rather than go to ED, most (except medical emergency) should go to detox centers where they can receive proper care with experienced staff as most intoxication and withdrawal symptoms can be managed with supportive care (Black & Andreasen, 2014). However, lack of community resources including staff and detox centers or being unsatisfied with existing community services may result in individuals visiting ED with non-acute conditions.

Lack of Social Support

Inadequate social support was reported as a major contributing factor for ED visits in the current review. Lack of social support and social connections result in loneliness and social isolation that are common in individuals with mental illness (Beutel et al., 2017), as social support/connection has been identified as essential in recovering from mental health problems since it decreases isolation, increases access to resources, and supports individuals in their journey to recovery (Leamy et al., 2011). There are social intervention programs developed to address social support and connection among individuals with mental health problems. For example, peer-support programs are a popular form of social support and social connection, and have played a positive role in patients’ outcomes including improved functioning, quality of life, and satisfaction with care, and housing stability, and increased patients sense of belonging and hopefulness while decreased psychiatric symptoms, substance use, hospitalization, and crisis services utilization (Davidson & Guy, 2012; van Vugt et al., 2012; Vayshenker et al., 2016). However, peer-support programs may face some challenges. To be effective, peer-support programs with peer and non-peer mental health workers should be well integrated into the mental health services, and require organizational support including guidance and training (e.g., how to utilize peers, negotiate professional boundaries and accommodating their mental health needs) (Mancini, 2018).

Another intervention has been prompted by the National Health Service (NHS) in England: Social Prescribing (SP) (NHS, 2019). SP enables healthcare providers to make a referral for patients to link workers who help them identify and access activities provided by voluntary, community, and social enterprise organizations at a community level (NHS, 2019). Dayson et al. (2020) found that SP has been associated with improved emotional, psychological, and social wellbeing for patients with mental illness by providing opportunities for sustained engagement in community activities, including participation in peer-to-peer support networks and volunteering.

Lack of Stable Housing

Studies found that safe and stable housing is associated with enhanced social and community integration, in turn, the integration can provide individuals opportunity to access resources including social, emotional, and instrumental supports, make them feel a sense of acceptance and belonging, which can lead to improved physical and mental health in individuals with MHA disorders and homelessness (Cherner et al., 2017; Durbin et al., 2019). Different supportive housing projects in different countries have been developed to help individuals have a stable and safe place to stay although outcome evaluations on these projects have produced mixed findings (Henwood et al., 2013; Kirst et al., 2020). For example, The Housing First project in Canada is an example of addressing housing needs among individuals who experience MHA disorders and homelessness without prerequisites (e.g., some housing projects require individuals to be sober or who are engaging in treatment) (Kirst et al., 2020). A majority of evaluation studies on Housing First showed positive outcomes in physical and mental health, and quality of life (Kirst et al., 2020). Providing safe and stable housing to individuals with MHA disorders has faced ongoing challenges, and more innovative interventions and research are needed.

Discharge Planning

An estimated 20% of patients who visited ED for MHA reasons return for a second ED visit within 6 months (Newton et al., 2010). While patients in nine of the studies reviewed, a clear definition of frequent ED visitor emerged (visited ED ≥ 5 times in the past 12 months) whether they were admitted to inpatient care or discharged from ED. Issues with discharge from ED were identified as a factor for frequent ED visits in the current review, while psychiatric inpatient discharge was also associated with repeated ED visits. Researchers have suggested the period immediately following discharge from inpatient care presents increased risks of serious and even life-threatening adverse outcomes, possible risk factors include premature treatment disengagement, which in turn increases the risk of relapse, ED re-visit, and re-hospitalization (Kalseth et al., 2016; Mann, 2014), unstable housing or homelessness (Nesper et al., 2016), and suicidal behavior (Kalseth et al., 2016). Smith et al.(2020) examined over 15,000 patients who were discharged from psychiatric inpatient care, and found that making an appointment with an outpatient mental health provider following discharge was associated with successful care transition. Making follow-up appointments with outpatient mental health providers has been approved as a cost-effective way to enhance discharge planning, improve continuity of care, and increase rates of successful transitions, thus reducing hospital re-admission (Smith et al., 2020). Although there is limited research on ED post-discharge, scheduling follow-up appointments with mental health providers in the community before patients are discharged from ED may result in a similar successful transition from inpatient care to the community.

ED Experience and Alternative Programs

As vulnerable individuals, patients with MHA issues should be treated with respect and sensitivity via interpersonal interactions in ED and other healthcare services, and their concerns should be addressed before discharge. Instead, the current review revealed that patients were seen as “hard to treat” or “difficult patients”, and patients felt rushed and their needs were not met, which may be the result of a lack of MHA training among healthcare providers, an overcrowded and intensive environment in ED, lack of resources in ED, and staff burnout (Gaeta, 2020; Salway et al., 2017).

Innovative alternative destination programs have been developed to address issues with MHA related ED visits. For example, a novel, pilot emergency medical services integrated program to treat patients experiencing MHA crises in a large urban county in the United States of America. This program allows some patients experiencing a MHA crisis, without acute medical care needs, to be transported to a dedicated community mental health center (CMHC), which maintains a 24/7 Crisis and Assessment Services as an alternative destination to ED (Creed et al., 2018). CMHC has successfully connected patients experiencing crises with mental health and substance use (Henderson et al., 2019). In a qualitative study by Thomas et al. (2018), many patients who used the CMHC services, reported they liked the program because of privacy, their basic needs being met, open communication, active involvement in their health-related decisions, and follow-up care (e.g., discussion of options of referral, referral matching, and referral made before discharge). Another study investigated the re-visit rate of the CMHC program, and found the repeated visit rate of CMHC was significantly lower in comparison with ED repeated visits (34% vs 68% respectively) (Henderson et al., 2019).

Utilizing Technologies

There is growing interest in enhancing mental health services via technology with programs being delivered via web or mobile apps that may help to expand the reach of community MHA services and reduce the demand for MHA services. For example, internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy has been successfully utilized in treating patients with mental health disorders in different countries (Titov et al., 2018). However, technology-delivered MHA services are not routinely integrated into community MHA services, and most have been primarily established by researchers (Lattie et al., 2020). To date, studies examining the use of technological tools for MHA services found that a majority of the tools have been unsuccessful (Bertagnolli, 2018; Gilbody et al., 2015). This in part was due to the process of tool development which did not involve target users, and thus did not meet their needs (Lattie et al., 2020). More studies on developing and implementing technology-based MHA tools including target users (e.g., healthcare providers, patients) are required.

Digital technology has also been used in aiding intervention engagement (Pithara et al., 2020). For example, Care Pathway Tool (CPT) in England, a shared care planning in community-based mental health services, aimed to use technology tools (i.e., mobile app) to improve care delivery and facilitate collaborative work in care planning for patients. This recovery-focused care plan involving patients in their care planning provides healthcare providers and patients direct access to the electronic care plan, thus enhancing effective collaborations resulting in a new form of interaction (Pithara et al., 2020).

Community Resources

Underfunded MHA services have been reported in different countries (Cohen & Peachey, 2014; Kohn et al., 2018; O'Neill & Rooney, 2018), and the current review is in agreement as lack of community resources were identified by patients and healthcare providers as a major contributing factor to frequent ED visits. To address community resources, adequate staff and services including MHA healthcare providers, detox centers, and other resources are vital for accessing timely and satisfactory services that meet patients’ needs. Training is essential for staff working with patients living with MHA disorders such as knowledge of MHA disorders, and education on MHA stigma. Social support programs require MHA workers or social workers or link workers to implement while housing, ED alternative programs, and utilizing technologies need financial support. Finally, evaluations of existing community programs regularly are the key to improving the quality of the programs, thus meeting the dynamic nature of patient’s needs.

The main limitation of this review is that not one study explored patients’ perspectives of how to improve existing community services, and nor were they asked what kind of services would meet their needs in the community as they have first-hand experience in utilizing community resources. Second, few studies addressed patients’ engagement with other treatments or programs in the community, and their relation to their ED visits. Third, only one study discussed organizational structure and processes in relation to ED visits. Fourth, all selected studies were conducted in developed countries and were published in English, which may limit views on the context of frequent ED visits.

In conclusion, it became apparent that lack of community resources was directly associated with frequent MHA related ED visits in this review. To address the issue is a complex undertaking that requires services that meet patients’ needs via both traditional community programs and innovative intervenetions, and most importantly needs commitment from communities and governments of all levels.

References

Aagaard, J., Aagaard, A., & Buus, N. (2014). Predictors of frequent visits to a psychiatric emergency room: A large-scale register study combined with a small-scale interview study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 51(7), 1003–1013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.11.002

Bergmans, Y., Spence, J. M., Strike, C., Links, P. S., Ball, J. S., Rufo, C., Rhodes, A. E., Watson, W. J., & Eynan, R. (2009). Repeat substance-using suicidal clients—How can we be helpful? Social Work in Health Care, 48(4), 420–431.

Bertagnolli, A. (2018). Digital mental health: challenges in implementation. New York: American psychiatric association.

Beutel, M. E., Klein, E. M., Brähler, E., Reiner, I., Jünger, C., Michal, M., & WiltinkWild MünzelLacknerTibubos, J. P. S. T. K. J. A. N. (2017). Loneliness in the general population: Prevalence, determinants and relations to mental health. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1262-x

Black, D. W., & Andreasen, N. C. (2014). Introductory textbook of psychiatry. Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Brennan, J. J., Chan, T. C., Hsia, R. Y., Wilson, M. P., & Castillo, E. M. (2014). Emergency department utilization among frequent users with psychiatric visits. Academic Emergency Medicine, 21(9), 1015–1022. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12453

CASP. (2018). Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Retrieved from https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf. Accessed 10 Jan 2021

Catalano, R., McConnell, W., Forster, P., McFarland, B., & Thornton, D. (2003). Psychiatric emergency services and the system of care. Psychiatric Services, 54(3), 351–355. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.54.3.351

Chaput, Y. J., & Lebel, M.-J. (2007). Demographic and clinical profiles of patients who make multiple visits to psychiatric emergency services. Psychiatric Services, 58(3), 335–341. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.58.3.335

Chaput, Y., Paradis, M., Beaulieu, L., & Labonté, É. (2008). A qualitative study of a psychiatric emergency. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 2(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-4458-2-9

Cherner, R. A., Aubry, T., & Ecker, J. (2017). Predictors of the physical and psychological integration of homeless adults with problematic substance use. Journal of Community Psychology, 45(1), 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21834

Cohen, K. R., & Peachey, D. (2014). Access to psychological services for Canadians: Getting what works to work for Canada’s mental and behavioural health. Canadian Psychology/psychologie Canadienne, 55(2), 126. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036499

Creed, J. O., Cyr, J. M., Owino, H., Box, S. E., Ives-Rublee, M., Sheitman, B. B., Williams, J. G., Bachman, M. W., Cabanas, J. G., Brent Myers, J., & Glickman, S. W. (2018). Acute crisis care for patients with mental health crises: Initial assessment of an innovative prehospital alternative destination program in North Carolina. Prehospital Emergency Care, 22(5), 555–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2018.1428840

Dalton, J., Booth, A., Noyes, J., & Sowden, A. J. (2017). Potential value of systematic reviews of qualitative evidence in informing user-centered health and social care: Findings from a descriptive overview. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 88, 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.04.020

Davidson, L., & Guy, K. (2012). Peer support among persons with severe mental illnesses: A review of evidence and experience. World Psychiatry, 11(2), 123–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.05.009

Dayson, C., Painter, J., & Bennett, E. (2020). Social prescribing for patients of secondary mental health services: emotional, psychological and social well-being outcomes. Journal of Public Mental Health, 19, 271–279.

Durbin, A., Nisenbaum, R., Kopp, B., O’Campo, P., Hwang, S. W., & Stergiopoulos, V. (2019). Are resilience and perceived stress related to social support and housing stability among homeless adults with mental illness? Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(4), 1053–1062.

Fleury, M.-J., Grenier, G., & Bamvita, J.-M. (2015). Predictors of frequent recourse to health professionals by people with severe mental disorders. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 60(2), 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371506000205

Fleury, M.-J., Grenier, G., Farand, L., & Ferland, F. (2019a). Reasons for emergency department use among patients with mental disorders. Psychiatric Quarterly, 90(4), 703–716. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-019-09657-w

Fleury, M.-J., Grenier, G., Farand, L., & Ferland, F. (2019b). Use of emergency rooms for mental health reasons in quebec: barriers and facilitators. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 46(1), 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-018-0889-3

Gaeta, T. J. (2020). Need for a holistic approach to reducing burnout and promoting well-being. Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians Open, 1(5), 1050. https://doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12111

Gilbody, S., Littlewood, E., Hewitt, C., Brierley, G., Tharmanathan, P., Araya, R., & Gask, L. (2015). Computerised cognitive behaviour therapy (cCBT) as treatment for depression in primary care (REEACT trial): Large scale pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h5627

Hannes, K., & Macaitis, K. (2012). A move to more systematic and transparent approaches in qualitative evidence synthesis: Update on a review of published papers. Qualitative Research, 12(4), 402–442. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111432992

Henderson, S. C., Owino, H., Thomas, K. C., Cyr, J. M., Ansari, S., Glickman, S. W., & Dusetzina, S. B. (2019). Post-discharge health services use for patients with serious mental illness treated at an emergency department versus a dedicated community mental health center. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-019-01000-6

Henwood, B. F., Cabassa, L. J., Craig, C. M., & Padgett, D. K. (2013). Permanent supportive housing: Addressing homelessness and health disparities? American Journal of Public Health, 103(S2), S188–S192. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301490

Kalseth, J., Lassemo, E., Wahlbeck, K., Haaramo, P., & Magnussen, J. (2016). Psychiatric readmissions and their association with environmental and health system characteristics: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 376. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-1099-8

Kirst, M., Friesdorf, R., Ta, M., Amiri, A., Hwang, S. W., Stergiopoulos, V., & O’Campo, P. (2020). Patterns and effects of social integration on housing stability, mental health and substance use outcomes among participants in a randomized controlled Housing First trial. Social Science & Medicine, 256, 113481.

Kohn, R., Ali, A. A., Puac-Polanco, V., Figueroa, C., López-Soto, V., Morgan, K., & Vicente, B. (2018). Mental health in the Americas: An overview of the treatment gap. Revista Panamericana De Salud Pública, 42, e165. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2018.165

Lattie, E. G., Nicholas, J., Knapp, A. A., Skerl, J. J., Kaiser, S. M., & Mohr, D. C. (2020). Opportunities for and tensions surrounding the use of technology-enabled mental health services in community mental health care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 47(1), 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-019-00979-2

Leamy, M., Bird, V., Le Boutillier, C., Williams, J., & Slade, M. (2011). Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(6), 445–452. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083733

Lincoln, A. K., Wallace, L., Kaminski, M. S., Lindeman, K., Aulier, L., & Delman, J. (2016). Developing a community-based participatory research approach to understanding of the repeat use of psychiatric emergency services. Community Mental Health Journal, 52(8), 1015–1021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-016-9989-2

Lindamer, L. A., Liu, L., Sommerfeld, D. H., Folsom, D. P., Hawthorne, W., Garcia, P., & Jeste, D. V. (2012). Predisposing, enabling, and need factors associated with high service use in a public mental health system. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 39(3), 200–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-011-0350-3

Mancini, M. A. (2018). An exploration of factors that effect the implementation of peer support services in community mental health settings. Community Mental Health Journal, 54(2), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-017-0145-4

Mann, C. (2014). Reducing nonurgent use of emergency departments and improving appropriate care in appropriate settings. CMCS Informational Bulletin, 1–8.

Mavrogiorgou, P., Brüne, M., & Juckel, G. (2011). The management of psychiatric emergencies. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 108(13), 222. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2011.0222

McCormack, R. P., Hoffman, L. F., Norman, M., Goldfrank, L. R., & Norman, E. M. (2015). Voices of homeless alcoholics who frequent Bellevue hospital: a qualitative study. Annals of emergency medicine, 65(2), 178–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.05.025

Meng, X., Muggli, T., Baetz, M., & D’Arcy, C. (2017). Disordered lives: Life circumstances and clinical characteristics of very frequent users of emergency departments for primary mental health complaints. Psychiatry Research, 252, 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.02.044

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Prisma-Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS med, 6(7), e1000097.

Nadelson, S., & Nadelson, L. S. (2014). Evidence-based practice article reviews using CASP tools: A method for teaching EBP. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 11(5), 344–346. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12059

Nesper, A. C., Morris, B. A., Scher, L. M., & Holmes, J. F. (2016). Effect of decreasing county mental health services on the emergency department. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 67(4), 525–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.09.007

Newton, A. S., Ali, S., Johnson, D. W., Haines, C., Rosychuk, R. J., Keaschuk, R. A., & Klassen, T. P. (2010). Who comes back? Characteristics and predictors of return to emergency department services for pediatric mental health care. Academic Emergency Medicine, 17(2), 177–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00633.x

NHS. (2019). Social prescribing and community-based support: Summary guide. NHS England.

Olsson, M., & Hansagi, H. (2001). Repeated use of the emergency department: Qualitative study of the patient’s perspective. Emergency Medicine Journal, 18(6), 430–434. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.18.6.430

O’Neill, S., & Rooney, N. (2018). Mental health in Northern Ireland: An urgent situation. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5(12), 965–966. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30392-4

Parkman, T., Neale, J., Day, E., & Drummond, C. (2017a). How do people who frequently attend emergency departments for alcohol-related reasons use, view, and experience specialist addiction services? Substance Use & Misuse, 52(11), 1460–146.

Parkman, T., Neale, J., Day, E., & Drummond, C. (2017b). Qualitative exploration of why people repeatedly attend emergency departments for alcohol-related reasons. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2091-9

Pasic, J., Russo, J., & Roy-Byrne, P. (2005). High utilizers of psychiatric emergency services. Psychiatric Services, 56(6), 678–684. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.56.6.678

Pithara, C., Farr, M., Sullivan, S. A., Edwards, H. B., Hall, W., Gadd, C., & Horwood, J. (2020). Implementing a digital tool to support shared care planning in community-based mental health services: Qualitative evaluation. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(3), e14868. https://doi.org/10.2196/14868

Poremski, D., Wang, P., Hendriks, M., Tham, J., Koh, D., & Cheng, L. (2020). Reasons for frequent psychiatric emergency service use in a large urban center. Psychiatric Services, 71(5), 440–446. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800532

Quail, J., Anderson, M., Osman, M., de Oliveira, C., Wodchis, W., Muhajarine, N., & Teare, G. (2017). Identifying superusers of health services with mental health and addiction problems. International Journal of Population Data Science, 1(1), 167.

Salway, R., Valenzuela, R., Shoenberger, J., Mallon, W., & Viccellio, A. (2017). Emergency department (ED) overcrowding: Evidence-based answers to frequently asked questions. Revista Médica Clínica Las Condes, 28(2), 213–219.

Schmidt, M., Ekstrand, J., & Tops, A. B. (2018). Self-reported needs for care, support and treatment of persons who frequently visit psychiatric emergency rooms in Sweden. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 39(9), 738–745. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2018.1481471

Schmidt, M., Garmy, P., Stjernswärd, S., & Janlöv, A. C. (2020a). professionals’ perspective on needs of persons who frequently use psychiatric emergency services. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 41(3), 182–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2019.1663565

Schmidt, M., Stjernswärd, S., Garmy, P., & Janlöv, A. C. (2020b). Encounters with persons who frequently use psychiatric emergency services: healthcare professionals’ views. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 1012. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17031012

Smith, T. E., Haselden, M., Corbeil, T., Wall, M. M., Tang, F., Essock, S. M., & Radigan, M. (2020). Effect of scheduling a post-discharge outpatient mental health appointment on the likelihood of successful transition from hospital to community-based care. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.20m13344

Spence, J. M., Bergmans, Y., Strike, C., Links, P. S., Ball, J. S., Rhodes, A. E., & Rufo, C. (2008). Experiences of substance-using suicidal males who present frequently to the emergency department. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, 10(4), 339–346. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1481803500010344

Thomas, K. C., Owino, H., Ansari, S., Adams, L., Cyr, J. M., Gaynes, B. N., & Glickman, S. W. (2018). Patient-centered values and experiences with emergency department and mental health crisis care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 45(4), 611–622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-018-0849-y

Titov, N., Dear, B., Nielssen, O., Staples, L., Hadjistavropoulos, H., Nugent, M., & Hovland, A. (2018). ICBT in routine care: A descriptive analysis of successful clinics in five countries. Internet Interventions, 13, 108–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2018.07.006

van Vugt, M. D., Kroon, H., Delespaul, P. A., & Mulder, C. L. (2012). Consumer-providers in assertive community treatment programs: Associations with client outcomes. Psychiatric Services, 63(5), 477–481. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201000549

Vandyk, A., Bentz, A., Bissonette, S., & Cater, C. (2019). Why go to the emergency department? Perspectives from persons with borderline personality disorder. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28(3), 757–765. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12580

Vandyk, A., Young, L., MacPhee, C., & Gillis, K. (2018). Exploring the experiences of persons who frequently visit the emergency department for mental health-related reasons. Qualitative Health Research, 28(4), 587–599. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317746382

Vayshenker, B., Mulay, A. L., Gonzales, L., West, M. L., Brown, I., & Yanos, P. T. (2016). Participation in peer support services and outcomes related to recovery. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 39(3), 274. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000178

Wise-Harris, D., Pauly, D., Kahan, D., De Bibiana, J. T., Hwang, S. W., & Stergiopoulos, V. (2017). “Hospital was the only option”: Experiences of frequent emergency department users in mental health. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44(3), 405–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0728-3

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Kevin Read, a Health Science Associate Librarian, for assisting in the database search.

Funding

The work was supported by Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HL contributed to the design of the review and search strategies, data screen and selection, data synthesis, and wrote the majority of the first manuscript draft. AG contributed to database search, data screen and selection, quality appraisal, and wrote the methods section and a part of results section of the first manuscript draft. KA contributed to quality appraisal and wrote a part of results section of the first manuscript draft. HL, CPT, LH, and DL contributed to interpretation of the results, and expertise on the subject. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, H., Glecia, A., Arisman, K. et al. Mental Health and Addiction Related Emergency Department Visits: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Community Ment Health J 58, 553–577 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-021-00854-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-021-00854-1