Abstract

The purpose of this study was to explore perceptions of subjective burden among Latino family members providing care for a loved one with schizophrenia. Data were collected from outpatient community mental health centers and featured 64 Latino family members who were primarily Spanish speaking and of Mexican origin. We used qualitative methods to examine subjective burden based on an open section of the Family Burden Interview Schedule. Five salient themes emerged capturing family members’ subjective burden experience: (a) interpersonal family relationships, (b) emotional and physical health, (c) loss of role expectations, (d) religion and spirituality, and (e) stigma. Overall, findings illustrated that families perceived numerous challenges in their caregiving. Implications for research and practice among Latino family members are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As a serious mental disorder affecting 1.1 % of the population, schizophrenia can cause profound functional and social impairments that negatively affect consumer and family well-being (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2009). Due to the impact of the illness, many consumers rely on family for various forms of support, including emotional, financial, and illness management (Awad and Voruganti 2008; Desai et al. 2013). Although providing direct tangible and emotional support may enhance the lives of consumers, it may also contribute to negative outcomes for families (Awad and Voruganti 2008; Gater et al. 2014; Maurin and Boyd 1990). A recent study found that when compared to families not caring for a family member with schizophrenia, those caring for a loved one with the illness were at greater risk of mental health and substance abuse disorders (DeVylder and Lukens 2013). Indeed, caring for a loved one with schizophrenia is often an overwhelming experience for family members and can contribute to burden.

The move from institutional care to community-based settings in the 1950s prompted many families to assume caregiving roles for family members with schizophrenia (Hatfield 1987; Maurin and Boyd 1990). Early researchers recognized that caring for a loved one with schizophrenia could pose unique challenges for families that may be conducive to greater burden. As such, there was interest in understanding and defining these caregiving challenges. In particular, Hoenig and Hamilton’s (1966) conceptualization of burden as composed of objective and subjective domains due to caregiving has influenced our current operationalization of this construct. Objective burden represents concrete factors affecting family life, such as financial difficulties and disruption of family activities. Subjective burden refers to perceptions or emotional reactions such as depression that individuals experience in relation to their caregiving. Although most measures examining burden have used Hoenig and Hamilton’s (1966) conceptualization of objective and subjective domains, several researchers have called for a more nuanced understanding of this multifaceted construct due to the potential lack of clarity when operationalizing these domains (Awad and Voruganti 2008; Gater et al. 2014; Maurin and Boyd 1990). One way to enhance our understanding of burden is by examining caregiver perspectives to shed light on family members’ salient caregiving experiences (Schulze and Rössler 2005) and inform treatment strategies that address family needs and strengths.

Subjective experiences may be especially important given research findings indicating that subjective burden may be difficult to manage due to the deleterious effects it can have on caregivers’ emotional and physical well-being (Breitborde et al. 2009; Breitborde et al. 2010; Magaña et al. 2007; Maurin and Boyd 1990). Obtaining family perspectives on burden experiences may improve our understanding of caregiving among underserved groups such as Latinos. Such knowledge is critical considering that Latinos with serious mental illness are more likely than other groups to live with their family (Barrio et al. 2003; Guarnaccia 1998; Ramírez García et al. 2009).

In line with the stress and coping literature, family members’ appraisals of caregiving stressors may influence their perceptions of burden (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). These appraisals are highly related to cultural beliefs regarding the caregiving role, responsibilities, and use of coping mechanisms (Barrio et al. 2011; Guarnaccia et al. 1992; Jenkins and Schumacher 1999; Saldaña et al. 1999). For instance, Latino families often report low levels of burden, as evidenced in a study examining hope and objective burden among low-acculturated family members caring for a loved one with schizophrenia that found family members generally reported low levels of objective burden despite probable caregiving strain (Hernandez et al. 2013). Moreover, Latino families are frequently characterized as close knit and supportive—values exemplified in collectivist cultures (Barrio 2000). However, it is important to consider that Latinos are not a monolithic group; therefore, such levels of support may not be present in all Latino family systems given the wide within-group heterogeneity. There are substantial differences within and between Latino groups related to factors such as level of acculturation, country of origin, migration experiences, socioeconomic, and regional differences that may affect the level of adherence to cultural norms (Guarnaccia et al. 2007). Such diversity may not only contribute to differences in adherence to cultural beliefs, but may also play a role in mental health service use (Alegría et al. 2007).

Studies have found that responsibilities associated with caregiving usually fall on one individual who may have little support from other family members (Marquez and Ramírez García 2011). Limited social support may lead to feelings of isolation and consequently increase caregivers’ perception of burden (Magliano et al. 2005). In addition, Latino families may struggle with low levels of education, poor English language skills, and stigma, which may impede access to needed resources and treatment (Magaña et al. 2007). Despite these challenges, Latino families may be culturally compelled to provide ongoing care to their loved ones, placing these families at greater risk of increased burden.

The purpose of this qualitative study was to expand our understanding of subjective burden among primarily Spanish-speaking Latino family members of Mexican origin residing in Southern California. Specifically, we were interested in exploring how Latino families caring for a loved one with schizophrenia perceived caregiving responsibilities and how they conceptualized subjective burden.

Methods

Sample

Data came from a controlled multifamily group intervention development study with Latino family members caring for a relative diagnosed with schizophrenia (Barrio and Yamada 2010). Sixty-four participants were enrolled in the study from outpatient community mental health centers directly operated by the County Department of Mental Health. Study criteria included: (a) diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder as defined in the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association 2000); (b) at least 18 years old; (c) no substance use or abuse disorder; (d) currently receiving medication support; and (e) living or maintaining contact on a weekly basis with a family member. Bilingual–bicultural research assistants contacted eligible consumers and asked them to participate in the study. If consumers provided permission, a key family member was identified and asked to participate in the study.

Family members primarily spoke Spanish and most were of Mexican origin (n = 52, 81 %). The majority of family members (n = 55, 92 %) fell in the very or mostly Mexican acculturation group using the Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican–Americans (Cuellar et al. 1980). In addition, most consumers (n = 59, 92 %) lived with their family and had an average length of illness of 12.78 years (SD = 11.75). Table 1 provides additional information on key family member demographic characteristics.

Study Procedures

As reported elsewhere (Barrio and Yamada 2010; Hernandez et al. 2013), data were collected by trained bilingual–bicultural interviewers in each participant’s preferred language. Most family member interviews were conducted in Spanish (n = 57, 89 %). Interviews took place at the community mental health center or at the family member’s home based on stated preference. The affiliated university’s institutional review board approved all study procedures.

Family members participated in three separate assessments examining key clinical and functional outcomes, including family burden. To examine subjective burden, data were collected from key family members using the open-ended section of the Family Burden Interview Schedule (FBIS; Pai and Kapur 1981). The FBIS not only includes items examining objective burden but also contains an open-ended section addressing subjective burden. The open section asks family members, “In what other ways has the family suffered as a result of family member’s illness?” Researchers adapted the FBIS in a previous study with a family sample of Latinos of Mexican origin (Kopelowicz et al. 2003).

Research interviewers administered the FBIS as part of the study protocol during each interview. Interviewers recorded participant responses to the open-ended section verbatim. Two bilingual–bicultural team members, also of Mexican origin, translated the responses in Spanish to English.

Analysis

We used a grounded theory approach (Glaser and Strauss 1967; Strauss and Corbin 1990) to analyze the data. This approach allowed for examination of burden among Latino family members of individuals with schizophrenia with the purpose of developing a greater conceptual understanding to enable theoretical formulation in this critical area of mental health research. Given that burden among Latino family members of individuals with schizophrenia has been understudied, grounded theory methods can provide a richer link to the data and study population through an inductive framework that allows for flexibility in the analysis process (Glaser and Strauss 1967; Padgett 2008).

Our substantial clinical and research experience with Latino populations and our bilingual and bicultural backgrounds facilitated the analysis process, making it possible to recognize cultural nuances present in the data. Open coding analysis entailed line-by-line reading of participant data by two team members. After independent coding of a subset of interviews, the team members discussed emerging findings and reached consensus on codes to begin the development of a codebook, which guided the coding process and improved dependability. The team members coded the remaining interviews and compared and further synthesized codes. Throughout the analysis process, team members examined co-occurrence of codes and used ongoing comparative analysis, memo writing, and discussion to reach a final consensus on themes and subthemes (Charmaz 2014). Data were sorted and coded using the qualitative software program ATLAS.ti, version 7.

Results

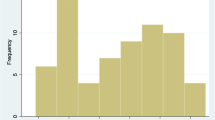

We identified five salient themes addressing perceptions of subjective burden among all study participants: (a) interpersonal family relationships, (b) effect on caregiver emotional and physical health, (c) loss of role expectations, (d) use of religion and spirituality to cope with the illness, and (e) stigma. Figure 1 provides a schematic layout of the salient themes and associated relationships that emerged from this examination of subjective burden.

Interpersonal Family Relationships

Participants generally said they considered the effect on their interpersonal relationships as the most challenging aspect of the illness. Most of these difficulties arose due to consumer behavior related to the illness. Families noted how arguments and verbal and physical altercations created a negative family environment that affected the quality of family relationships. A family member noted, “Our family has separated. We used to do everything together, but now we can’t all be together at the same time, because my youngest son is afraid [of the consumer] and they’ve gotten violent and physical before.” Similarly, several participants expressed how isolation of the individual with schizophrenia from others, possibly due to negative symptoms associated with the illness, made it difficult for family members to engage with the consumer, thus affecting family relationships. A family member said, “We don’t do anything as a family anymore. For Christmas, he only spent a little time with us. There’s improvement—he ate with us. He did come out of his room.”

Emotional and Physical Health

The stress on interpersonal relationships often led families to encounter emotional or physical health issues, or both. For instance, several family members expressed their burden as an emotional experience, commonly describing feelings of depression or deep sadness. A family member stated, “I also feel depression—I have cried, I have felt sadness for seeing him like this.” Some families also described physical health problems that they attributed to stressors linked to their caregiving responsibilities. One family member said, “High blood pressure … at times I feel a pain in my chest. I know that it is due to the sadness that I have, the pressure.” It was also common for family members to describe exhaustion and stress as a response to their caregiving role.

Stress and frustration were particularly present during the initial phase of the illness, when family members were confused about the consumer’s symptoms and behavioral changes. A family member described this time as “a very drastic thing.” Family members usually did not know what was happening to their loved one when symptoms first appeared, leading to feelings of apprehension and fear. A family member noted, “It was only at the beginning, not knowing, not having knowledge about the illness, the shock for what was happening.” Some family members described their continued vigilance for possible relapse and subsequent stress. One participant said family members are most affected, “Just when he relapses, trying to be there for him showing support. Just worrying about him and trying to be there. When he’s well, try to make sure he stays well.”

Loss of Role Expectations

Many family members expressed the sense of loss that they felt due to their loved one’s illness. A family member said, “I feel like my son is dead because he’s not the same person anymore.” Many family members said they had adjusted their expectations for their loved ones and were coming to terms with their new role as a caregiver for their adult child. Some participants described mourning for what could have been and the loss of potential achievement for their loved one’s future.

Moreover, some family members believed that the illness would make it difficult for consumers to meet social roles and expectations considered important, such as obtaining an education and having their own family. This sentiment was best expressed by one family member who said, “He always liked to study and he had to leave it. Only the sorrow, that one cannot do anything … that he cannot continue studying nor have his own family.” For some families, perceptions regarding role expectations were especially difficult because they questioned their loved one’s capacity for independence and self-care in the future.

Religion and Spirituality

Families often drew on their religious and spiritual beliefs and practices when discussing their perceptions of burden, especially how this resource helped them come to terms with their loved one’s illness and better manage their responsibilities. A family member stated, “There was a time when it caused me much worry and now, well, it is not that I am getting used to it, but it is God who helps.” Like many other family members in this study, this family member’s religious and spiritual beliefs helped her to cope with her loved one’s illness. Similarly, another family member interpreted her daughter’s behavior and related challenges as a test from God. She said:

When she gets sick, she yells at me and orders me around. During those times I say, “Why do I have to live this?” But then, things get better, and it is as if nothing had happened. God is something, isn’t he? He gives us tests to see how much we can withstand.

Conceptualizing her loved one’s illness as a test may ease some of the emotional burden for this mother as the key caregiver. At the same time, it may prevent her from seeking support to address possible caregiving stressors.

Stigma

Negative comments and actions toward consumers and family members were also connected to burden. One mother said, “One feels rejected by society as if it were a crime to have a child like this.” Family members described how stigma toward mental illness resulted in a lack of support and understanding from others, including extended family members. A mother said, “At times one can feel bad. Sometimes I feel isolated. My married daughter, well, her husband … I feel he rejects my son. He sees him as a danger.” The experience of stigma by family members may contribute to feelings of isolation and limit their sources of social support. Another family member expressed the negative perceptions of her extended family regarding her husband’s illness. She said, “The rejection of the family, not my children, but my extended family. My family, they say he is crazy and tease him. His family criticizes me that I have a spell on him and keep him sick.” It appears that this family member struggled with her extended family members’ criticisms and beliefs regarding illness causation, which may contribute to increased burden.

Discussion

Few studies have examined subjective burden among Latino family members caring for a loved one with schizophrenia. As such, our study makes an important contribution to the field of mental health research. In particular, our use of qualitative methods allowed us to explore the perspectives of Latino family members, gaining a richer understanding of the process and possible effects of caregiving burden. Such understanding is needed to develop a conceptual framework that includes cultural contexts. Moreover, due to cultural views on caregiving, burden may be a sensitive topic that standardized measures may not fully capture (Saldaña et al. 1999); therefore, our qualitative approach provided greater depth to this area of research.

The cultural context is an important component of the caregiving experience. For instance, consumers in our study overwhelmingly lived with their family members and as previously mentioned, this living situation is common among low-acculturated Latino consumers with serious mental illness. For instance, in a multicultural community sample of family members caring for a loved one with serious mental illness, Latino consumers were more likely to live with their family (78 %) when compared to African Americans (59 %) and European Americans (31 %; Guarnaccia and Parra 1996). Living situation has been found to contribute to increased burden (Maurin and Boyd 1990; Schulze and Rössler 2005), including subjective burden (Solomon and Draine 1995). In addition, when considering sociocultural factors such as low English language proficiency and lack of familiarity with the mental health system, low-acculturated Latino family caregivers may experience additional burden (Magaña et al. 2007). Therefore, although Latinos may share similar subjective burden experiences with other ethnocultural groups, their level of direct caregiving and involvement with their loved one may add another layer of burden that may be inadvertently missed or disregarded.

Our findings suggest that family members experience subjective burden at many levels. In this study, these concerns primarily centered on interpersonal family relationships and emotional and physical effects on caregivers. In addition, social expectations regarding role functioning and stigma further contributed to burden, whereas religion and spirituality served as a coping mechanism but also a possible deterrent to seeking professional support. Overall, our findings and those of other studies that have included participants from diverse racial and ethnic groups (Smith et al. 2014) underscore the critical role of the cultural context in caregiving. Family relationships are a salient component of Latino culture, and caregivers identified difficulties in interpersonal family relationships as their major source of subjective burden. Similarly, in their study examining family members of individuals with schizophrenia, Weisman, Rosales, Kymalainen, and Armesto (2005) found that family cohesion was associated with better psychosocial functioning among Latinos and African Americans but not European American family members. Latinos and other groups that share strong cultural values of interdependence often view their family relationships as important to their own well-being and may place family needs above individual needs. Difficulty in these relationships has the potential to create strain among family members and lead to burden (Suro and Weisman de Mamani 2013).

In addition, our findings indicate that schizophrenia symptoms contribute to problematic behaviors that affect family relationships. Family members described disruptive behaviors associated with positive symptoms as the most difficult to manage. They also struggled with understanding consumers’ lack of interest in engaging with others, an issue possibly related to negative symptoms. Findings have been mixed regarding which symptoms cause more distress for caregivers, with some studies indicating that positive symptoms are more severe (Grandón et al. 2008; Magaña et al. 2007) and others suggesting that negative symptoms have a greater impact on interpersonal relationships (Roick et al. 2006). Our findings suggest that both positive and negative symptoms of the illness influence family relationships. Severity of symptoms may be more important than the types of symptoms (Awad and Voruganti 2008).

Psychological distress including depression has been reported among Latino caregivers (Gutiérrez-Maldonado et al. 2005; Magaña et al. 2007) and caregivers from other racial and ethnic groups (Gater et al. 2014). In our study, family members noted that caregiving was an emotional experience. Using the term emotional to refer to how families view their experience with their loved one’s illness conveys feelings associated with depression. Family members who described an emotional or physical response to their caregiving generally expressed depression, worry, and frustration. Similar findings were seen in a recent study examining caregivers of individuals with schizophrenia in which more than half of the sample was African American (Gater et al. 2014), suggesting that psychological distress is a common experience for caregivers. In the present study, psychological distress was more prominent during the initial phase of the illness. Studies have found that the early phase of the illness can be especially intense (Martens and Addington 2001) and in some cases traumatic (Barton and Jackson 2008) for caregivers as they learn about the diagnosis and illness management (Karp and Tanarugsachock 2000).

Family members also struggled with feelings of loss related to diminished aspirations for their loved one’s future. Schizophrenia can negatively affect the normative tasks associated with an individual’s life course, such as having a career and marriage (Stein and Wemmerus 2001). Family members, particularly parents, may react by expressing a deep sense of loss and grief (Richardson et al. 2011; Rose et al. 2006) related to the effects of the illness, as noted by a participant in our study who said she felt she had lost her son. The grief experienced by family members can be a potential risk factor for psychological distress, including depression and burden (Chen and Lukens 2011). Moreover, Latino families may be at greater risk due to cultural expectations regarding marriage and family (Landale and Oropesa 2007), which may create additional stress related to beliefs regarding consumers’ inability to fulfill these social roles.

Similar to other research (Guarnaccia et al. 1992; Murray-Swank et al. 2006; Rammohan et al. 2002; Weisman et al. 2003), some participants in our study used religion and spirituality to cope with their caregiving responsibilities. It appears that religion and spirituality helped families make sense of and come to terms with their loved one’s illness. For some families, it provided a framework to help them understand the challenges they experienced as caregivers. Perceiving caregiving challenges as a religious or spiritual test made difficult situations easier to handle for these families. However, the potential for dismissing these challenges and not seeking support may eventually lead to greater distress. As such, more research is needed to improve our understanding of the relationship between religion and spirituality and caregiving.

Several studies examining burden among family members caring for a loved one with schizophrenia identified stigma as a major concern that affects both families and consumers (González-Torres et al. 2007; Larson and Corrigan 2008; Struening et al. 2001). Similarly, families in this study expressed burden due to experiences with stigma. These experiences included instances in which individuals considered consumers dangerous or blamed family members for causing the illness. Negative comments and behaviors from others, including extended family members, created feelings of rejection and shame and further contributed to emotional distress among caregivers. These feelings of rejection indicate that families may experience social isolation that can add to their subjective burden (Karnieli-Miller et al. 2013; Larson and Corrigan 2008). Although caregivers may subscribe to strong views on family interdependence, they may experience limited support from their extended family and therefore be vulnerable to increased burden (Hackethal et al. 2013).

Limitations and Future Directions

Our study highlighted subjective burden experiences among Latino families of Mexican origin caring for a loved one with schizophrenia. Along with these strengths, it is important to note several limitations. First, because burden is a multidimensional construct, it is not possible to explore all its facets with a brief open-ended section. Despite this limitation, our qualitative methods and use of bilingual and bicultural research interviewers in particular may have facilitated participants’ disclosure of burden, which may be a difficult topic for families to discuss given cultural views on caregiving (Grandón et al. 2008; Guarnaccia and Parra 1996). Furthermore, previous studies using well-established measures have reported low levels of burden among Latino caregivers (Grandón et al. 2008; Hernandez et al. 2013; Kopelowicz et al. 2003). Specifically, a previous study (Hernandez et al. 2013) using the same sample of study participants found that caregivers generally reported low objective burden. Other studies (Suro and Weisman de Mamani 2013) have found that concrete factors of caregiving associated with objective burden influence caregiver reports of subjective burden. However, low levels of objective burden as seen in a previous study (Hernandez et al. 2013) did not appear to affect how families reported their subjective burden experiences. Such findings further underscore the value of qualitative methods in our current study in terms of allowing a deeper examination of the different cultural dimensions of burden.

Second, the average length of illness among consumers was 12.78 years, indicating that most family members had been providing care to their loved ones for at least several years. Future studies may consider including length of illness as a factor in examining subjective burden, especially in view of our finding that family members regarded the initial phase of the illness as the most challenging. Third, given our study parameters focusing on subjective burden, we were not able to include other positive aspects of caregiving. However, we recognize that caring for a family member with schizophrenia can be rewarding, as reported in various studies (Bauer et al. 2012; Heru 2000; Hsiao and Tsai 2014; Veltman et al. 2002; Zauszniewski et al. 2010). Consequently, further research examining caregiving should consider incorporating a multidimensional perspective that allows for different components of the caregiving experience, including benefits and strengths. Fourth, our study participants were primarily Spanish speaking and of Mexican origin; therefore, findings may not be generalizable to other Latinos. As previously noted, Latinos are a heterogeneous group and as such, there may be diversity in how different Latino subgroups experience burden. However, our sample was recruited from a community mental health setting and our findings may provide insights into the caregiver experience for family members of consumers in similar settings.

Finally, because our sample did not include other racial or ethnic groups, we were not able to compare our findings with other groups and thereby examine the unique Latino caregiving experience. Studies examining burden among caregivers of individuals with schizophrenia have found similar themes to those presented in the current study. It is important to remember, however, that because Latinos with serious mental illness are more likely to live with their family compared to other groups, examining the Latino caregiver perspective is critical to understanding possible burden and other caregiving needs that may be present in this underserved group. Therefore, although our study’s findings present themes that other groups may share, they nevertheless highlight the unique nuances that Latino family members and specifically Mexican-origin family members may experience as caregivers.

Conclusion

Based on our findings, it is important for practitioners to explore caregiving challenges that may contribute to burden among Latino family members. In particular, interpersonal family relationships and their effect on caregiver emotional and physical health are important areas to consider. Additionally, it would be beneficial to consider other relevant factors such as loss of role expectations, religion and spirituality, and stigma. Creating an accepting and nonjudgmental environment (Barrio and Dixon 2012) may facilitate communication between providers and family members and allow families to express the challenges and rewards associated with the caregiving experience. Such openness may also contribute to changes in health policy to ensure greater recognition of families as important resources in the lives of individuals with schizophrenia (Schulze and Rössler 2005).

Taken together, our findings have important implications for mental health research and practice. Numerous studies have examined the positive effects of psychoeducation as an evidence-based treatment for consumer and family well-being (Dixon et al. 2010; Lucksted et al. 2012), yet these interventions are not always available in community mental health settings (Dixon et al. 1999; Lucksted et al. 2012). Furthermore, it may be even more challenging for monolingual Spanish-speaking Latinos to receive these services. Factors such as language may affect knowledge of treatment resources or availability of bilingual staff members, and issues with transportation and stigma may further prevent these families from receiving needed services (Barrio et al. 2008, 2011). Providers should also consider that although many Latinos value a strong family orientation and interdependence, these families may experience limited social support and be at risk of burden.

References

Alegría, M., Mulvaney-Day, N., Woo, M., Torres, M., Gao, S., & Oddo, V. (2007). Correlates of past-year mental health service use among Latinos: Results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. American Journal of Public Health, 97, 76–83. doi:10.2105/ajph.2006.087197.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th edn., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author.

Awad, A. G., & Voruganti, L. N. P. (2008). The burden of schizophrenia on caregivers: A review. PharmacoEconomics, 26, 149–162. doi:10.2165/00019053-200826020-00005.

Barrio, C. (2000). The cultural relevance of community support programs. Psychiatric Services, 51, 879–884. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.51.7.879.

Barrio, C., & Dixon, L. B. (2012). Clinician interactions with patients and families. In J. A. Lieberman & R. M. Murray (Eds.), Comprehensive care of schizophrenia: A textbook of clinical management (pp. 342–356). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Barrio, C., Hernandez, M., & Barragán, A. (2011). Serving Latino families caring for a person with serious mental illness. In L. P. Buki & L. M. Piedra (Eds.), Creating infrastructures for Latino mental health (pp. 159–175). New York, NY: Springer.

Barrio, C., Palinkas, L. A., Yamada, A.-M., Fuentes, D., Criado, V., Garcia, P., & Jeste, D. V. (2008). Unmet needs for mental health services for Latino older adults: Perspectives from consumers, family members, advocates, and service providers. Community Mental Health Journal, 44, 57–74. doi:10.1007/s10597-007-9112-9.

Barrio, C., & Yamada, A.-M. (2010). Culturally based intervention development: The case of Latino families dealing with schizophrenia. Research on Social Work Practice, 20, 483–492. doi:10.1177/1049731510361613.

Barrio, C., Yamada, A.-M., Hough, R. L., Hawthorne, W., Garcia, P., & Jeste, D. V. (2003). Ethnic disparities in use of public mental health case management services among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services, 54, 1264–1270. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.54.9.1264.

Barton, K., & Jackson, C. (2008). Reducing symptoms of trauma among carers of people with psychosis: Pilot study examining the impact of writing about caregiving experiences. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 42, 693–701. doi:10.1080/00048670802203434.

Bauer, R., Koepke, F., Sterzinger, L., & Spiessl, H. (2012). Burden, rewards, and coping—The ups and downs of caregivers of people with mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 200, 928–934. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e31827189b1.

Breitborde, N. J. K., López, S. R., Chang, C., Kopelowicz, A., & Zarate, R. (2009). Emotional over-involvement can be deleterious for caregivers’ health. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 44, 716–723. doi:10.1007/s00127-008-0492-0.

Breitborde, N. J. K., López, S. R., & Kopelowicz, A. (2010). Expressed emotion and health outcomes among Mexican-Americans with schizophrenia and their caregiving relatives. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 198, 105–109. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181cc532d.

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Chen, W.-Y., & Lukens, E. (2011). Well being, depressive symptoms, and burden among parent and sibling caregivers of persons with severe and persistent mental illness. Social Work in Mental Health, 9, 397–416. doi:10.1080/15332985.2011.575712.

Cuellar, I., Harris, L., & Jasso, R. (1980). An acculturation scale for Mexican American normal and clinical populations. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 2, 199–217.

Desai, P. R., Lawson, K. A., Barner, J. C., & Rascati, K. L. (2013). Estimating the direct and indirect costs for community-dwelling patients with schizophrenia. Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Services Research, 4, 187–194. doi:10.1111/jphs.12027.

DeVylder, J. E., & Lukens, E. P. (2013). Family history of schizophrenia as a risk factor for axis I psychiatric conditions. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 47, 181–187. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.09.023.

Dixon, L. B., Dickerson, F., Bellack, A. S., Bennett, M., Dickinson, D., Goldberg, R. W., & Kreyenbuhl, J. (2010). The 2009 Schizophrenia PORT psychosocial treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 36, 48–70. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp115.

Dixon, L., Lyles, A., Scott, J., Lehman, A., Postrado, L., Goldman, H., & McGlynn, E. (1999). Services to families of adults with schizophrenia: From treatment recommendations to dissemination. Psychiatric Services, 50, 233–238. doi:10.1176/ps.50.2.233.

Gater, A., Rofail, D., Tolley, C., Marshall, C., Abetz-Webb, L., Zarit, S. H., & Berardo, C. G. (2014). “Sometimes it’s difficult to have a normal life”: Results from a qualitative study exploring caregiver burden in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research and Treatment, 2014, 368215. doi:10.1155/2014/368215.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Piscataway, NJ: Aldine de Gruyter.

González-Torres, M. A., Oraa, R., Arístegui, M., Fernández-Rivas, A., & Guimon, J. (2007). Stigma and discrimination towards people with schizophrenia and their family members. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 42, 14–23. doi:10.1007/s00127-006-0126-3.

Grandón, P., Jenaro, C., & Lemos, S. (2008). Primary caregivers of schizophrenia outpatients: Burden and predictor variables. Psychiatry Research, 158, 335–343. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2006.12.013.

Guarnaccia, P. J. (1998). Multicultural experiences of family caregiving: A study of African American, European American, and Hispanic American families. New Directions for Mental Health Services, 1998(77), 45–61. doi:10.1002/yd.23319987706.

Guarnaccia, P. J., Martínez Pincay, I., Alegría, M., Shrout, P. E., Lewis-Fernández, R., & Canino, G. J. (2007). Assessing diversity among Latinos: Results from the NLAAS. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 29, 510–534. doi:10.1177/0739986307308110.

Guarnaccia, P. J., & Parra, P. (1996). Ethnicity, social status, and families’ experiences of caring for a mentally ill family member. Community Mental Health Journal, 32, 243–260. doi:10.1007/BF02249426.

Guarnaccia, P. J., Parra, P., Deschamps, A., Milstein, G., & Argiles, N. (1992). Si Dios quiere: Hispanic families’ experiences of caring for a seriously mentally ill family member. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 16, 187–215. doi:10.1007/bf00117018.

Gutiérrez-Maldonado, J., Caqueo-Urízar, A., & Kavanagh, D. J. (2005). Burden of care and general health in families of patients with schizophrenia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 40, 899–904. doi:10.1007/s00127-005-0963-5.

Hackethal, V., Spiegel, S., Lewis-Fernández, R., Kealey, E., Salerno, A., & Finnerty, M. (2013). Towards a cultural adaptation of family psychoeducation: Findings from three Latino focus groups. Community Mental Health Journal, 49, 587–598. doi:10.1007/s10597-012-9559-1.

Hatfield, A. B. (1987). Families as caregivers: A historical perspective. In A. B. Hatfield & H. P. Lefley (Eds.), Families of the mentally ill (pp. 3–29). New York, NY: Guildford Press.

Hernandez, M., Barrio, C., & Yamada, A.-M. (2013). Hope and burden among Latino families of adults with schizophrenia. Family Process, 52, 697–708. doi:10.1111/famp.12042.

Heru, A. M. (2000). Family functioning, burden, and reward in the caregiving for chronic mental illness. Families, Systems, & Health, 18, 91–103. doi:10.1037/h0091855.

Hoenig, J., & Hamilton, M. W. (1966). The schizophrenic patient in the community and his effect on the household. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 12, 165–176. doi:10.1177/002076406601200301.

Hsiao, C.-Y., & Tsai, Y.-F. (2014). Caregiver burden and satisfaction in families of individuals with schizophrenia. Nursing Research, 63, 260–269. doi:10.1097/NNR.0000000000000047.

Jenkins, J. H., & Schumacher, J. G. (1999). Family burden of schizophrenia and depressive illness: Specifying the effects of ethnicity, gender, and social ecology. British Journal of Psychiatry, 174, 31–38. doi:10.1192/bjp.174.1.31.

Karnieli-Miller, O., Perlick, D. A., Nelson, A., Mattias, K., Corrigan, P., & Roe, D. (2013). Family members’ of persons living with a serious mental illness: Experiences and efforts to cope with stigma. Journal of Mental Health, 22, 254–262. doi:10.3109/09638237.2013.779368.

Karp, D. A., & Tanarugsachock, V. (2000). Mental illness, caregiving, and emotion management. Qualitative Health Research, 10, 6–25. doi:10.1177/104973200129118219.

Kopelowicz, A., Zarate, R., Smith, V. G., Mintz, J., & Liberman, R. P. (2003). Disease management in Latinos with schizophrenia: A family-assisted, skills training approach. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 29, 211–227. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006999.

Landale, N. S., & Oropesa, R. S. (2007). Hispanic families: Stability and change. Annual Review of Sociology, 33, 381–405. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131655.

Larson, J. E., & Corrigan, P. (2008). The stigma of families with mental illness. Academic Psychiatry, 32, 87–91. doi:10.1176/appi.ap.32.2.87.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer.

Lucksted, A., McFarlane, W., Downing, D., & Dixon, L. (2012). Recent developments in family psychoeducation as an evidence-based practice. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 38, 101–121. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00256.x.

Magaña, S. M., Ramírez García, J. I., Hernández, M. G., & Cortez, R. (2007). Psychological distress among Latino family caregivers of adults with schizophrenia: The roles of burden and stigma. Psychiatric Services, 58, 378–384. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.58.3.378.

Magliano, L., Fiorillo, A., De Rosa, C., Malangone, C., Maj, M., & the National Mental Health Project Working Group. (2005). Family burden in long-term diseases: A comparative study in schizophrenia vs. physical disorders. Social Science and Medicine, 61, 313–322. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.064.

Marquez, J. A., & Ramírez García, J. I. (2011). Family caregivers’ monitoring of medication usage: A qualitative study of Mexican-origin families with serious mental illness. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 35, 63–82. doi:10.1007/s11013-010-9198-3.

Martens, L., & Addington, J. (2001). The psychological well-being of family members of individuals with schizophrenia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 36, 128–133. doi:10.1007/s001270050301.

Maurin, J. T., & Boyd, C. B. (1990). Burden of mental illness in the family: A critical review. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 4, 99–107. doi:10.1016/0883-9417(90)90016-E.

Murray-Swank, A. B., Lucksted, A., Medoff, D. R., Yang, Y., Wohlheiter, K., & Dixon, L. B. (2006). Religiosity, psychosocial adjustment, and subjective burden of persons who care for those with mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 57, 361–365. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.57.3.361.

Padgett, D. K. (2008). Qualitative methods in social work research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Pai, S., & Kapur, R. L. (1981). The burden on the family of a psychiatric patient: Development of an interview schedule. British Journal of Psychiatry, 138, 332–335. doi:10.1192/bjp.138.4.332.

Ramírez García, J. I., Hernández, B., & Dorian, M. (2009). Mexican American caregivers’ coping efficacy. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 44, 162–170. doi:10.1007/s00127-008-0420-3.

Rammohan, A., Rao, K., & Subbakrishna, D. K. (2002). Religious coping and psychological wellbeing in carers of relatives with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 105, 356–362. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.1o149.x.

Richardson, M., Cobham, V., Murray, J., & McDermott, B. (2011). Parents’ grief in the context of adult child mental illness: A qualitative review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14, 28–43. doi:10.1007/s10567-010-0075-y.

Roick, C., Heider, D., Toumi, M., & Angermeyer, M. C. (2006). The impact of caregivers’ characteristics, patients’ conditions and regional differences on family burden in schizophrenia: A longitudinal analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 114, 363–374. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00797.x.

Rose, L. E., Mallinson, R. K., & Gerson, L. D. (2006). Mastery, burden, and areas of concern among family caregivers of mentally ill persons. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 20, 41–51. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2005.08.009.

Saldaña, D. H., Dassori, A. M., & Miller, A. L. (1999). When is caregiving a burden? Listening to Mexican American women. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 21, 283–301. doi:10.1177/0739986399213006.

Schulze, B., & Rössler, W. (2005). Caregiver burden in mental illness: Review of measurement, findings and interventions in 2004–2005. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 18, 684–691. doi:10.1097/01.yco.0000179504.87613.00.

Smith, M. E., Lindsey, M. A., Williams, C. D., Medoff, D. R., Lucksted, A., Fang, L. J., & Dixon, L. B. (2014). Race-related differences in the experiences of family members of persons with mental illness participating in the NAMI Family to Family education program. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54, 316–327. doi:10.1007/s10464-014-9674-y.

Solomon, P., & Draine, J. (1995). Subjective burden among family members of mentally ill adults: Relation to stress, coping, and adaptation. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 65, 419–427. doi:10.1037/h0079695.

Stein, C. H., & Wemmerus, V. A. (2001). Searching for a normal life: Personal accounts of adults with schizophrenia, their parents and well-siblings. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29, 725–746. doi:10.1023/a:1010465117848.

Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Struening, E. L., Perlick, D. A., Link, B. G., Hellman, F., Herman, D., & Sirey, J. A. (2001). Stigma as a barrier to recovery: The extent to which caregivers believe most people devalue consumers and their families. Psychiatric Services, 52, 1633–1638. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1633.

Suro, G., & Weisman de Mamani, A. G. (2013). Burden, interdependence, ethnicity, and mental health in caregivers of patients with schizophrenia. Family Process, 52, 299–311. doi:10.1111/famp.12002.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2009). Schizophrenia (NIH Publication No. 09-3517). Washington, DC: National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/schizophrenia/nimh-schizophrenia-booklet.pdf

Veltman, A., Cameron, J. I., & Stewart, D. E. (2002). The experience of providing care to relatives with chronic mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 190, 108–114. doi:10.1097/00005053-200202000-00008.

Weisman, A. G., Gomes, L. G., & López, S. R. (2003). Shifting blame away from ill relatives: Latino families’ reactions to schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 191, 574–581. doi:10.1097/01.nmd.0000087183.90174.a8.

Weisman, A., Rosales, G., Kymalainen, J., & Armesto, J. (2005). Ethnicity, family cohesion, religiosity and general emotional distress in patients with schizophrenia and their relatives. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 193, 359–368. doi:10.1097/01.nmd.0000165087.20440.d1.

Zauszniewski, J. A., Bekhet, A. K., & Suresky, M. J. (2010). Resilience in family members of persons with serious mental illness. Nursing Clinics of North America, 45, 613–626. doi:10.1016/j.cnur.2010.06.007.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the families, providers, and community advisory board members who participated in this study. Dr. Barrio received support from the National Institute of Mental Health (R34 MH076087) and Dr. Hernandez received support from the National Institute of Mental Health (R36 MH102077). The authors wish to acknowledge the following individuals: Nydia Durazo, Maria Sanchez, and Paula Helu Fernandez also participated in data collection, translation, and data analysis.

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hernandez, M., Barrio, C. Perceptions of Subjective Burden Among Latino Families Caring for a Loved One with Schizophrenia. Community Ment Health J 51, 939–948 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-015-9881-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-015-9881-5