Abstract

The extent to which measures of coping adequately capture the ways that homeless youth cope with challenges, and the influence these coping styles have on mental health outcomes, is largely absent from the literature. This study tests the factor structure of the Coping Scale using Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and then investigates the relationship between coping styles and depression using hierarchical logistic regression with data from 201 homeless youth. Results of the EFA indicate a 3-factor structure of coping, which includes active, avoidant, and social coping styles. Results of the hierarchical logistic regression show that homeless youth who engage in greater avoidant coping are at increased risk of meeting criteria for major depressive disorder. Findings provide insight into the utility of a preliminary tool for assessing homeless youths’ coping styles. Such assessment may identify malleable risk factors that could be addressed by service providers to help prevent mental health problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

When exposed to stressful situations, youths’ coping methods may influence their risk for mental health problems. Coping is a process in which individuals apply strategies to help change stressful environments or reduce psychological distress associated with adverse circumstances (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). The ability to adapt to stressful stimuli is crucial in a young person’s development, with successful adaptation often helping to regulate emotions and behavior, thereby decreasing sources of stress (Compas et al. 2001). Because youths’ exposure to multiple stressors is a significant risk factor for poor health and well-being (Grant et al. 2003), the methods that youth use to cope with distressing situations have implications for their future adjustment and development of mental health problems.

Although progress has been made in the measurement of coping among youth in the general population (Compas et al. 2001), less is known about the extent to which measures of coping adequately capture the ways in which homeless youth cope with stress. This is quite an oversight, as research suggests homeless youth face an abundance of significant stressors, including a search for basic needs such as housing and food as well as dangers on the streets associated with victimization (Coates and Mckenzie-Mohr 2010). These uniquely stressful living environments, coupled with homeless youths’ lack of traditional resources, may elicit different forms of coping compared to youth in the general population. As such, homeless youth research would benefit from including coping scales normed with homeless youth populations to improve methodological rigor. With this understanding, Kidd and Carroll (2007) developed the Coping Scale, an instrument integrating themes from qualitative coping interviews with homeless youth (Kidd 2003) and existing standardized coping items. However, the psychometric properties of the Coping Scale have yet to be tested with a larger sample of homeless youth. With the overarching goal of developing sound instruments that effectively explore coping responses among this vulnerable group, the current study aimed to: (1) explore the factor structure of the Coping Scale, (2) describe the coping styles most commonly utilized in a sample of homeless youth, and (3) explore the relationship between identified coping styles and depression.

Multiple Styles of Coping

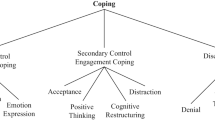

In the broad coping literature, reactions to stressful situations and use of coping styles are multifaceted (Skinner et al. 2003). Extant research commonly dichotomizes these multiple ways of coping into problem-focused and emotion-focused coping (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). Problem-focused coping, which encompasses goal-oriented strategies where individuals generate alternative solutions to problems and attempt to change stress-provoking situations, has been associated with positive adaptation to stressors and improved mental health and well-being (Lazarus and Folkman 1984; Mayordomo-Rodríguez et al. 2014). Emotion-focused coping includes lessening emotional distress through strategies such as minimization and tension reduction (Boals et al. 2011; Lazarus and Folkman 1984). Although emotionally-laden reactions are often seen as a maladaptive response to stress, certain forms of emotion-focused coping can help promote positive solutions through processes such as cognitive reappraisal, wherein individuals effectively change the meaning of a situation (Lazarus and Folkman 1984).

An additional distinction frequently made in the literature is between active and avoidant coping styles (Boals et al. 2011; Chao 2011; Wilkinson et al. 2000). Active types of coping include responses that aim to change the stressor itself or how one thinks about it (Herman-Stahl et al. 1994), and these methods of coping tend to produce more favorable outcomes as individuals seek helpful information and direct efforts to maintain control of challenging circumstances (Curry and Russ 1985). One distinct form of active coping involves the mobilization of social resources. Seeking social support as a response to stress has been shown to significantly predict overall life satisfaction among youth samples (Saha et al. 2014). In contrast, avoidant coping includes withdrawal or distancing oneself from a problematic situation, which may in turn lead to ineffective efforts to reduce distress (Curry and Russ 1985) and stress-related psychological issues (Herman-Stahl et al. 1994).

Although coping styles demonstrate long-term stability, some research suggests they may be malleable with intervention (Nielsen and Knardahl 2014). When exposed to challenging situations over time, research commonly suggests that individuals are consistent in their coping style, and therefore, one’s response to difficult experiences has significant implications for mental health and well-being (Ebata and Moos 1991). However, forms of coping are also malleable with targeted interventions. Stewart et al. (2009) developed an intervention to optimize homeless youths’ social coping. Prior to the intervention, youth reported utilizing coping styles that included substance use, avoidance, and violence, but participation in the program was associated with youths’ increased coping skills, particularly enhancing support-seeking behaviors (Stewart et al. 2009). These results highlight that, while coping styles may remain stable over time and thus can affect outcomes, programs that facilitate prosocial behaviors and tools to manage stressful situations can also change coping among vulnerable populations.

Stress and Coping among Homeless Youth

Homeless youth face stress prior to leaving home and once homeless. Many youth become homeless to escape conflict, abuse, and stress in their home environment (Cauce et al. 2000; Rosenthal et al. 2007). Without traditional support from stable adults, this group continues to face myriad stressful experiences while homeless, including inconsistent shelter, food, and financial resources (Unger et al. 1998). Moreover, homeless youth are at heightened risk for experiencing crime and violence; they are five times more likely to be physically assaulted compared to their housed counterparts (Ensign and Santelli 1998) and reported elevated rates of sexual assault, ranging from 15 % to over 50 % in some samples (Alder 1991; Kipke et al. 1997; Whitbeck et al. 1997). Such experiences lead to numerous adverse outcomes, including posttraumatic stress symptoms (Bender et al. 2010), depressive symptoms (Whitbeck et al. 1999), in addition to risk behaviors and health concerns, such as elevated HIV rates and risk behaviors (Melander and Tyler 2010), substance use and dependence (Bender et al. 2010; Rytwinski et al. 2013), criminal activity and arrests (Ferguson et al. 2012). Considering the many aforementioned stressors, better understanding youths’ methods for coping is critical, as coping methods may represent malleable intervention targets to buffer youth and help them to avoid significant psychological distress.

As such, burgeoning literature has expanded to focus on how homeless youth cope with distress while living on the streets (Kidd and Carroll 2007). Similar to youth in the general population, researchers have found that particular coping styles are associated with differential outcomes among homeless youth. Research has shown that homeless youth who report increased use of avoidant coping have higher rates of internalizing and externalizing behavior problems (Votta and Manion 2003) and increased risk of suicidal ideation, particularly among females (Kidd and Carroll 2007). In contrast, problem-focused coping has been found to buffer against the development of depression and problem substance use (Unger et al. 1998). Furthermore, social support has also been shown to mitigate the negative effects of risk factors on mental health such that homeless youth who report high levels of social support are less likely to have symptoms of depression (Unger et al. 1998). This research with homeless youth is consistent with the broader coping literature, which suggests the use of adaptive coping patterns (e.g., active, social coping) may contribute to healthy developmental trajectories, while, maladaptive coping styles (e.g., avoidant coping) used in childhood or adolescence may place youth on behavioral and emotional risk trajectories (Compas et al. 2001).

Measurement of Coping among Homeless Youth Populations

Given the substantial stress experienced by homeless youth and the potential for unique patterns in coping among this population, it is important that researchers better specify the factor structures of scales used to assess coping among this population. The Coping Scale is a 14-item instrument that was developed based on qualitative interviews with homeless youth, informed by assessments of homeless youths’ coping behaviors associated with exposure to highly stressful street contexts (Kidd and Carroll 2007). These qualitative findings highlighted the importance of social support, attitudes and beliefs such as self-worth, hope for the future, and pride in self-reliance for this population (Kidd 2003). Additionally, qualitative results showed a range of coping strategies that include adapting to changing circumstances and reducing reactance to the opinions and behaviors of others (Kidd 2003; Lindsay et al. 2000). The Coping Scale developed based on these qualitative themes also incorporates several items from preexisting standardized measures (Kidd and Carroll 2007). To our knowledge, this is the only coping instrument developed specifically for homeless youth populations, yet the psychometric properties of this scale are absent from the literature. The present study tests the factor structure of the Coping Scale and explores the relationship between identified coping factors and depression with the ultimate goal of informing researchers and practitioners about the utility of a culturally sensitive coping instrument for homeless youth.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

A sample of 201 homeless youth were recruited from homeless youth-serving host agencies located in a large city in the Rocky Mountain region of the U S. For study eligibility, participants were required to fall within the age range of 18–24 years and provide written informed consent. Additionally, in order to identify youth who were indeed spending substantial time away from home rather than simply accessing ancillary services through the agency, youth were screened into the study if they indicated spending at least 2 weeks away from home in the month prior to the interview (Whitbeck 2009). Youth who were not capable of providing consent, due to cognitive limitations or noticeable intoxication at the time of the interview, were excluded from the study. Characteristics of the sample including demographics (age, gender, ethnicity), homelessness experiences (primary residence, transience, length of time homeless), coping strategies, and depressive outcomes are described in Table 1.

Homeless youth-serving host agencies included drop-in centers that offered referral services, case management, and basic subsistence items (e.g., food, hygiene supplies), and short- and long-term shelters. These agencies were selected based on their existing relationships with researchers and their commitment to be involved with the study. Agency staff determined if youth were eligible for participation and referred youth to research staff who explained the study procedures and secured written consent. Participants completed a 45-min quantitative retrospective interview, which was facilitated by research staff. Youth were compensated with a $10.00 gift card in appreciation of their participation.

Measures

Through 1:1 interviews, participants answered a series of standardized, self-report instruments and researcher-developed questions that examined demographic and background information, coping, and major depressive episode.

Demographics

Age, gender, (0 = male, 1 = female), and ethnicity (1 = White, 2 = Black, 3 = Hispanic, 4 = other) were assessed as demographic variables. Ethnicity was subsequently dummy-coded to include Black (0 = no, 1 = yes), Latino (0 = no, 1 = yes), and other (0 = no, 1 = yes) with White as a reference category.

Homelessness Experiences

Background information regarding youths’ experiences while homeless was obtained. Participants were asked about their primary living arrangement (0 = homeless, 1 = temporarily housed with relative, friend, foster parent, or formal facility), transience (number of intercity moves since leaving home for the first time), and length of time homeless (number of years between interview data and the date the youth last left home).

Coping Styles

Coping strategies were examined using the Coping Scale developed by Kidd and Carroll (2007). This instrument included four dimensions of coping based on items derived from previous standardized measures and qualitative work by Kidd (2003). All coping items used a 5-point scale from 1 (Never) to 5 (Almost Always) in response to the prompt “Please rate how much you use each of the following ways of dealing with problems.” In this original version of the Coping Scale (Kidd and Carroll 2007), Problem-Focused Coping was assessed using two items: (1) “Concentrated on what to do and how to solve the problem,” and (2) “Think about what happened and try to sort it out in my head.” These items were originated from the Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WCQ; Folkman and Lazarus 1985). Avoidant Coping was assessed with two items: (1) “Try not to think about it,” which was used from the WCQ and (2) “Go to sleep,” a commonly mentioned coping strategy among homeless youth. Social Coping was comprised of two items derived from qualitative interviews: (1) “Go to someone I trust for support,” and an item characterized as social withdrawal, (2) “Go off by myself to think.” The fourth dimension, Other Ways of Coping, was assessed with eight items particularly derived from Kid’s (2003) qualitative work. These items included, (1) “Try to learn from the bad experience,” (2) “Use my anger to get me through it,” (3) “Use drugs or alcohol,” (4) “Do a hobby (e.g., read, draw),” (5) “Try to value myself and not think so much about other people’s opinions,” (6) “Realize that I am strong and can deal with whatever is bothering me,” (7) “Think about how things will get better in the future,” and (8) “Use my spiritual beliefs/belief in a higher power.”

Dependent Variable: Depression

Major depressive episode was assessed using the Mini International Neuropsychiatry Interview (MINI; Sheehan et al. 1998). This is a widely-used, brief, structured interview that helps screen for Axis I psychiatric disorders as determined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association 2000). The MINI has demonstrated good reliability (Lecrubier et al. 1997) as well as convergent validity with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis 1 Disorders (SCID), an established measure of diagnostic criteria (Sheehan et al. 1998). In assessing whether youth met criteria for major depressive episode, participants were asked, if in the prior 2 weeks, they felt down and lost interest. Participants who confirmed either of these items were then asked a series of questions regarding depressive-related symptomology that might have occurred within the past 2 weeks, such as changes in appetite, sleep patterns, energy level, concentration, and suicidal thoughts. Those who indicated 5 or more of the 9 symptoms were coded positive for meeting criteria for a current major depressive episode (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Data Analysis

Using SPSS (version 21.0), descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic, homelessness experience, and coping variables as well as for rates of major depressive episode to characterize the sample. To test the factor structure of the Coping Scale, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted on the original 14 items using principal components analysis. EFA provides preliminary information as to whether there are underlying factors that are present in a scale specific to a particular sample (DeVellis 1991; Guada et al. 2011). The scree test was used to determine the number of factors to retain (DeVellis 1991). The scree test allows for visual examination of a graphical illustration of the eigenvalues. The eigenvalues are illustrated by dots and presented in descending order (Ledesma and Valero-Mora 2007). These dots are linked with a line and the point at which the line levels off establishes the cutoff point (Ledesma and Valero-Mora 2007). As such, the number of factors that should be retained is determined by the eigenvalues that fall above this cutoff point. With regard to missing data, only one case had missing data on the variables examined in the current analysis and was therefore excluded by listwise deletion.

Hierarchical logistic regression analyses were then conducted to examine how identified coping factors were associated with major depressive episode, controlling for demographic and homelessness experience variables. Variables were entered sequentially in 3 steps. First, demographics were entered, particularly focusing on age, gender, and ethnicity. Second, homelessness experiences including primary residence, transience, and length of time homeless were entered into the model. Finally, coping style factors were entered into the third block of the model. Our primary interest was to determine if types of coping accounted for a significant amount of variance over and above demographic and homelessness experience variables, and these coping variables were therefore entered together in the third block of the hierarchical regression model.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 provides demographic information pertaining to the 201 participants included in this study. As noted, more than half of the sample was male and primarily identified racially and ethnically as White. At the time of the interviews, the sample had been homeless, on average, for approximately 30 months. Over one-third of the sample met diagnostic criteria for major depressive episode.

Exploratory Factor Analysis

An EFA, using principal components analysis as an extraction method, was conducted to explore the underlying factor structure of the original 14-item Coping Scale. The fit of the factor model was assessed using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. The overall KMO was .736, and Barlett’s test of sphericity was significant, χ2(91) = 588.33, p < .001. The scree test gave a three-factor solution accounting for 47.30 % of the variance. Inspection of the component matrix, however, indicated that three variables had values less than .55; a “good” interpretable loading as recommended by Comrey and Lee (1992). These three variables comprised items: (1) “Go off by myself to think,” (2) “Use my spiritual beliefs/belief in a higher power,” and (3) “Go to sleep.” These variables were also conceptually problematic in that it is unclear if they adequately fit with the higher loaded items in each factor. As such, these variables were excluded from the three confirmed factors.

The factor loading matrix for the three-factor solution with the original 14 Coping Scale items is presented in Table 2. Of the 14 Coping Scale items included in the EFA, seven items with loadings of ≥.55 loaded on factor 1, three items on factor 2, and one item on factor 3. Given our results, we conducted a second factor analysis, limiting the test to three factors and excluding the three aforementioned items with low loadings. Results from the subsequent EFA indicated an overall KMO of .724 and Barlett’s test of sphericity was significant, χ2(55) = 478.98, p < .001. As seen in Table 3, values produced in the component matrix had values greater or equal to .55.

Factor 1 was defined as active coping and accounted for 29.08 % of the variance with an eigenvalue of 3.20. Active coping items involved problem-focused techniques as well as efforts to increase awareness of stressors and attempts to reduce negative outcomes. These items included: (1) “Realize that I am strong and can deal with whatever is bothering me,” (2) “Think about how things will get better in the future,” (3) “Try to learn from the bad experience,” (4) “Concentrated on what to do and how to solve the problem,” (5) “Think about what happened and try to sort it out in my head,” (6) “Do a hobby,” and (7) “Try to value myself and not think so much about other people’s opinions.” The three items that loaded on Factor 2 (“Try not to think about it”; “Use drugs or alcohol”; “Use my anger to get me through it”) were described as avoidant coping, which accounted for 14.13 % of the variance and had an eigenvalue of 1.55. These items are consistent with prior research describing avoidant coping styles in which individuals use maladaptive coping techniques to escape problematic situations. Finally, factor 3 was defined as social coping and included one item, “Go to someone I trust for support.” This accounted for 11.01 % of the variance with an eigenvalue of 1.21. The final three-factor solution of the Coping Scale explained 54.22 % of the total variance in homeless youths’ coping strategies. Internal consistency for the three factors was examined using Cronbach’s alpha. The alphas for the individual factors ranged from moderate (α = .51) for avoidant coping to excellent (α = .78) for active coping. Due to only one item loading on factor 3, an alpha could not be calculated for social coping.

Coping Styles Most Frequently Employed

Youth most highly endorsed using active coping (M = 3.82; SD = .73), followed by social coping strategies (M = 3.41; SD = 1.29), and, finally, avoidant coping (M = 2.74, SD = .98). Measured on a 5-point scale from 1 (Never) to 5 (Almost Always), these results indicate youth report using active coping often, using social coping sometimes-often and using avoidant coping sometimes.

Relationship Between Coping Styles and Depression

A three-step model regressing depression on demographic, homelessness variables and coping styles was then tested. The rate of correct classification for the null model was 64.0 %. In the first block, goodness-of-fit tests of models with demographics against constant-only models did not significantly distinguish youth with depression, χ2(5) = 4.76, p = .45 (Nagelkerke R2 = .03). In the second block, homelessness experiences were entered into the regression model. Goodness-of-fit tests of the overall, χ2(8) = 11.98, p = .15 (Nagelkerke R2 = .08) and block Chi square, χ2(3) = 7.22, p = .07 models were not statistically significant. As such, the addition of homelessness experience variables did not contribute significantly beyond models with demographics and constants in determining youth who met criteria for major depressive episode.

In the third block, coping style variables (active, avoidant, and social coping) were examined as correlates of depression. Goodness-of-fit tests of the overall models were statistically significant in predicting depression, χ2(11) = 33.12, p < .01 (Nagelkerke R2 = .21). Furthermore, block Chi square indicated that the addition of coping strategy variables explained 13 % of variation in depression and this change in R2 was significant, χ2(3) = 21.13, p < .001. The rate of correct classification for this model was 72.0 %. For each 1-pt increase in avoidant coping, youth were more than twice as likely to meet criteria for major depressive episode. Moreover, the number of years homeless was statistically significant in this final block, indicating that for each additional year of homelessness, the odds of meeting criteria for major depressive episode increased by 17 %. Results for the hierarchical logistic regression models retained from the third block can be found in Table 4.

Discussion

The current study sought to test the factor structure of the Coping Scale (Kidd and Carroll 2007), developed to assess the coping strategies employed by homeless youth, and to determine whether the identified coping factors predicted depression among a relatively large and diverse sample of homeless youth. While the Coping Scale offers unique insight into homeless youths’ coping by using items derived from qualitative interviews with youth (Kidd 2003), our study aimed to improve the utility of this instrument in research and practice by beginning to establish its psychometric properties.

Our results indicate a three-factor structure of the Coping Scale, suggesting the presence of active coping (cognitive or behavioral efforts to address the stressor directly, think about it differently, or implement healthy activities), avoidant coping (strategies to escape thinking about or encountering the stressor), and social coping subscales (seeking the support of others to cope with the stressor). These factors are similar but not completely aligned to Kidd and Carroll’s (2007) four anticipated dimensions of coping: problem-focused, avoidant coping, social coping, and “other ways of coping”. Specifically, most items in the original subscale “other ways of coping”, which were all derived directly from Kidd’s (2003) qualitative work, actually loaded on either the avoidant coping factor (use my anger to get me through it; use drugs or alcohol), or on the active coping factor (Try to learn from the bad experience; Do a hobby; Try to value myself and not think so much about other people’s opinions; Realize that I am strong and can deal with whatever is bothering me; Think about how things will get better in the future). This new factor structure may arguably have more utility in research and practice as it dismantles the rather vague “other” category and helps identify distinct coping styles with more practical implications for intervention.

That some coping factors identified in this study were significantly associated with depression, lends support for using future iterations of this tool to understand the psychosocial needs of this vulnerable population. Specifically, avoidant coping (as re-conceptualized in this study to include getting angry or using substances to cope) predicted depression. Our revision of the Coping Scale’s avoidant coping factor is thus, not only consistent with prior conceptualizations of avoidant coping (e.g., Adolescent Coping Orientation for Problem Experiences, Ways of Coping Questionnaire) but also predictive of mental health problems in a pattern that replicates previous studies that find youth who employ avoidant coping strategies are at increased risk for suicidality (Kidd and Carroll 2007). This broadened assessment of avoidant coping may have utility in understanding homeless youths’ coping strategies as it relates to psychological functioning in the future.

It is surprising, however, that neither the active coping nor the social coping factors were associated with reduced odds of depression, as previous research would suggest these forms of coping can be protective among homeless youth (Unger et al. 1998). One possible explanation is that the active coping factor included a large number of items that may represent diverse coping strategies. In the existing literature, number and types of coping items vary across measures of active coping, yet they often aim to assess underlying constructs that are similar to the ones established in this study’s active coping factor, such as positive cognitive restructuring and problem solving (Pina et al. 2008). For example, the Brief COPE instrument (Carver 1997) includes only two items that comprise the active coping subscale: “I’ve been concentrating my efforts on doing something about the situation I’m in”, and “I’ve been taking action to try to make the situation better.” Although our analyses indicate these items load together as one factor, the items represent efforts to change thoughts, to employ health behaviors, and to problem solve to address the problem directly. Such diversity may have minimized our ability to find a relationship between active coping methods and depression. Conversely, only one item (Go to someone I trust for support) was utilized to measure social coping, which may explain a lack of relationship to depression.

On the other hand, it is possible that these surprising findings are related less to measurement and more to youth’s effectiveness in employing these potentially protective strategies. Future research will need to investigate homeless youths’ competencies in employing active and social coping strategies, as this may be an area for future intervention if found lacking.

Limitations

Certain study limitations should be considered in interpreting our results. Because our sample included service-seeking youth who were recruited from agencies connected to the researchers and were located in a small geographic area, our ability to generalize results to youth disconnected from services or to service-seeking youth in other regions is limited. Additionally, youth who were cognitively impaired and intoxicated during the time of assessment were excluded from this study. This may in turn limit the degree to which the findings generalize to youth struggling with these issues. Future research should test the identified factor structures by administering the Coping Scale with other diverse samples of homeless youth. Furthermore, due to the cross-sectional design used in this study we are unable to make assumptions of causal order. It may, therefore, be that youth who meet criteria for depressive episodes were more likely to use certain coping strategies or that certain coping strategies placed youth at risk for depression. Although challenging with this transient population, longitudinal research would allow greater understanding about causal order of the relationships identified in our study. In addition, social desirability bias may have prevented youth from sharing sensitive or personal information, which may have resulted in underreports of psychiatric symptoms. Our interviewers were extensively trained in building rapport, assuring confidentiality, and establishing privacy during interviews in an effort to reduce this bias.

Implications

Despite the identified limitations, the results presented here have several implications for research and practice. The newly structured Coping Scale offers a preliminary tool for assessing coping styles that could have a real impact on youths’ functioning. However, the tool requires further refinement and testing. First, because of the aforementioned limitation regarding the one-item measure of social coping, future refinement of this scale might consider additional items to more fully capture forms of social coping, such as seeking someone to talk to about the situation (Folkman and Lazarus 1988) and items that query whom youth go to for support (e.g., stable adults, trusted family members, peers, case managers/service providers, etc.). While social support is typically deemed a positive construct, it is possible that youths’ social supports, at times, come in the form of negative influences or others who encourage or condone risky behaviors. Additional social coping items might include asking youth about the types of support provided, including informational, emotional and instrumental resources.

Moreover, future research would also benefit from further understanding the seemingly diverse array of sub-constructs encompassed within the measure of active coping. Upon reviewing the items loading on the active coping factor, it is possible that this measure may be further dissected into more specific sub-constructs, such as belief in self (Realize that I am strong and can deal with whatever is bothering me; Try to value myself and not think so much about other people’s opinions), and hope (Think about how things will get better in the future; Try to learn from the bad experience). Agencies aiming to foster youths’ strengths and resiliencies would benefit from a measure that establishes a more refined and precise ways of measuring this coping style.

As such, future research would benefit from refining and testing this instrument with other samples of homeless youth using confirmatory factor analysis to determine whether the same factor structure is supported. This is particularly important given previous research that suggests heterogeneous homeless youth populations and regional differences in the stressors youth face and related outcomes (Thompson et al. 2000).

If validated in future work, this instrument could hold promise for identifying malleable coping strategies. Understanding youths’ current methods of coping may be valuable to service agencies as a means of identifying treatment targets. If, for example, a youth relies primarily on avoidant coping styles to deal with stressors, agencies may use skill-building interventions to enhance active and social coping skills that have been shown to reduce risk for more serious emotional and behavioral problems (Unger et al. 1998). Using a valid and culturally-sensitive assessment of these different forms of coping is an essential starting place to understanding how to help homeless youth better cope with the stressors of homelessness.

References

Alder, C. (1991). Victims of violence: The case of homeless youth. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 24(1), 1–14.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., Text Revision). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Bender, K. A., Ferguson, K., Thompson, S., Komlo, C., & Pollio, D. (2010). Factors associated with trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder among homeless youth in three US cities: The importance of transience. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(1), 161–168.

Boals, A., vanDellen, M. R., & Banks, J. B. (2011). The relationship between self-control and health: The mediating effect of avoidant coping. Psychology and Health, 26, 1049–1062. doi:10.1080/08870446.2010.529139.

Carver, C. S. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4, 92–100.

Cauce, A. M., Paradise, M., Ginzler, J. A., Embry, L., Morgan, C. J., Lohr, Y., et al. (2000). The characteristics and mental health of homeless adolescents: Age and gender differences. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 8(4), 230–239. doi:10.1177/106342660000800403.

Chao, R. C. L. (2011). Managing stress and maintaining well-being: Social support, problem-focused coping, and avoidant coping. Journal of Counseling & Development, 89, 338–348.

Coates, J., & McKenzie-Mohr, S. (2010). Out of the frying pan, into the fire: Trauma in the lives of homeless youth prior to and during homelessness. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 37, 65–96.

Compas, B. E., Connor-Smith, J. K., Saltzman, H., Thomsen, A. H., & Wadsworth, M. E. (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 87–127. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.127.1.87.

Comrey, A. L., & Lee, H. B. (1992). A first course in factor analysis. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Curry, S. L., & Russ, S. W. (1985). Identifying coping strategies in children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 14, 61–69.

DeVellis, R. F. (1991). Scale development: Theory & applications. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Ebata, A. T., & Moos, R. H. (1991). Coping and adjustment in distressed and healthy adolescents. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 17, 33–54.

Ensign, J., & Santelli, J. (1998). Health status and service use: Comparison of adolescents at a school-based health clinic with homeless adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 152(1), 20–24.

Ferguson, K. M., Bender, K. A., Thompson, S. J., Xie, B., & Pollio, D. (2012). Exploration of arrest activity among homeless young adults in four US cities. Social Work Research, 36(3), 233–238.

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1985). If it changes it must be a process: Study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 150–170.

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1988). Ways of coping questionnaire. Redwood City, CA: Mind Garden.

Grant, K. E., Compas, B. E., Stuhlmacher, A. F., Thurm, A., McMahon, S. D., & Halpert, S. (2003). Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: Moving from markers to mechanisms of risk. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 447–466. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.447.

Guada, J., Land, H., & Han, J. (2011). An exploratory factor analysis of the burden assessment scale with a sample of African-American families. Community Mental Health Journal, 47, 233–242. doi:10.1007/s10597-010-9298-0.

Herman-Stahl, M. A., Stemmler, M., & Petersen, A. C. (1994). Approach and avoidant coping: Implications for adolescent mental health. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 24, 649–665.

Kidd, S. A. (2003). Street youth: Coping and interventions. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 20(4), 235–261. doi:10.1023/A:1024552808179.

Kidd, S. A., & Carroll, M. R. (2007). Coping and suicidality among homeless youth. Journal of Adolescence, 30, 283–296. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.03.002.

Kipke, M. D., Simon, T. R., Montgomery, S. B., Unger, J. B., & Iversen, E. F. (1997). Homeless youth and their exposure to and involvement in violence while living on the streets. Journal of Adolescent Health, 20(5), 360–367.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer.

Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, D., Weiller, E., Amorim, P., Bonora, I., Sheehan, K., et al. (1997). The MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interivew. A short diagnostic structured interview: Reliability and validity according to the CIDI. European Psychiatry, 12, 224–231.

Ledesma, R. D., & Valero-Mora, P. (2007). Determining the number of factors to retain in EFA: An easy-to-use computer program for carrying out parallel analysis. http://pareonline.net/pdf/v12n2.pdf.

Lindsay, E. W., Kurtz, D., Jarvis, S., Williams, N. R., & Nackerud, L. (2000). How run-aways and homeless youth navigate troubled waters: Personal strengths and resources. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 17, 115–140.

Mayordomo-Rodríguez, T., Meléndez-Moral, J. C., Viguer-Segui, P., & Sales-Galán, A. (2014). Coping strategies as predictors of well-being in youth adult. Social Indicators Research. doi:10.1007/s11205-014-0689-4.

Melander, L. A., & Tyler, K. A. (2010). The effect of early maltreatment, victimization, and partner violence on HIV risk behavior among homeless young adults. Journal of Adolescent Health, 47(6), 575–581.

Nielsen, M. B., & Knardahl, S. (2014). Coping strategies: A prospective study of patterns, stability, and relationships with psychological distress. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 55(2), 142–150.

Pina, A. A., Villalta, I. K., Ortiz, C. D., Gottschall, A. C., Costa, N. M., & Weems, C. F. (2008). Social support, discrimination, and coping as predictors of posttraumatic stress reactions in youth survivors of Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 37(3), 564–574. doi:10.1080/15374410802148228.

Rosenthal, D., Mallett, S., & Myers, P. (2007). Why do homeless young people leave home? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 30(3), 281–285. doi:10.1111/j.1467-842X.2006.tb00872.x.

Rytwinski, N. K., Avena, J. S., Echiverri-Cohen, A. M., Zoellner, L. A., & Feeny, N. C. (2013). The relationships between posttraumatic stress disorder severity, depression severity and physical health. Journal of Health Psychology, 19(4), 509–520.

Saha, R., Huebner, S., Hills, K. J., Malone, P. S., & Valois, R. F. (2014). Social coping and life satisfaction in adolescents. Social Indicators Research, 115, 241–252. doi: 10.1007/s11205-012-0217-3

Sheehan, D., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K., Amorim, P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., et al. (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59, 22–33.

Skinner, E. A., Edge, K., Altman, J., & Sherwood, H. (2003). Searching for the structure of coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 216–269. doi:10.1037/0022-2909.129.2.216.

Stewart, M., Reutter, L., Letourneau, N., & Makwarimba, E. (2009). A support intervention to promote health and coping among homeless youths. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 41, 51–77.

Thompson, S. J., Pollio, D. E., & Bitner, L. (2000). Outcomes for adolescents using runaway and homeless youth services. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 3, 79–97. doi:10.1300/J137v03n01_05.

Unger, J. B., Kipke, M. D., Simon, T. R., Johnson, C. J., Montgomery, S. B., & Iverson, E. (1998). Stress, coping, and social support among homeless youth, 13(2), 134–157. doi:10.1177/0743554898132003.

Votta, E., & Manion, I. G. (2003). Factors in the psychological adjustment of homeless adolescent males: The role of coping style. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(7), 778–785. doi:10.1097/01.CHI.0000046871.56865.D9.

Whitbeck, L. B. (2009). Mental health and emerging adulthood among homeless young people. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group.

Whitbeck, L. B., Hoyt, D. R., & Ackley, K. A. (1997). Abusive family backgrounds and later victimization among runaway and homeless adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 7(4), 375–392.

Whitbeck, L. B., Hoyt, D. R., & Yoder, K. A. (1999). A risk-amplification model of victimization and depressive symptoms among runaway and homeless adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 27(2), 273–296.

Wilkinson, R. B., Walford, W. A., & Espnes, G. A. (2000). Coping styles and psychological health in adolescents and young adults: A comparison of moderator and main effects models. Australian Journal of Psychology, 52, 155–162.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The project was approved by the researchers’ university Institutional Review Board.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brown, S.M., Begun, S., Bender, K. et al. An Exploratory Factor Analysis of Coping Styles and Relationship to Depression Among a Sample of Homeless Youth. Community Ment Health J 51, 818–827 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-015-9870-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-015-9870-8