Abstract

Longstanding disparities in substance use disorders and treatment access exist among American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/AN). Computerized, web-delivered interventions have potential to increase access to quality treatment and improve patient outcomes. Prior research supports the efficacy of a web-based version [therapeutic education system (TES)] of the community reinforcement approach to improve outcomes among outpatients in substance abuse treatment; however, TES has not been tested among AI/AN. The results from this mixed method acceptability study among a diverse sample of urban AI/AN (N = 40) show that TES was acceptable across seven indices (range 7.8–9.4 on 0–10 scales with 10 indicating highest acceptability). Qualitative interviews suggest adaptation specific to AI/AN culture could improve adoption. Additional efforts to adapt TES and conduct a larger effectiveness study are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/AN) face disproportionately greater and persistent health disparities (Beals et al. 2005; Thomas et al. 2009; National Center for Health Statistics 2012), including higher rates of substance use disorders as compared to the U.S. general population (Compton et al. 2007; Hasin et al. 2007; Gone and Trimble 2012; Greenfield and Venner 2012; SAMHSA 2010, 2012). In 2010, 16 % of individuals that identified as AI/AN met criteria for a substance use disorder, compared to 10 % of the general population (SAMHSA 2012). Substance abuse has also been linked to poorer health outcomes among AI/ANs compared to other American racial subgroups (Pleis et al. 2010; Indian Health Services (IHS) 2009; SAMHSA 2010). Further, and often related to high rates of substance use disorders, data suggest that AI/ANs also face higher rates of alcohol related deaths (Chartier and Caetano 2010; Russo et al. 2004; National Center for Health Statistics 2012), mental health disorders (National Center for Health Statistics 2012), suicide rates (National Center for Health Statistics 2012; Gone and Trimble 2012; Advancing Indian Health Care 2009), and lower AIDS survival rates (CDC 2012). The U.S. government has recently noted the disproportionately negative health consequences among AI/AN through the formation of the Office of Indian Alcohol and Substance Abuse in 2010. Thus, increasing targeted research to reduce substance-related health disparities is a critical national priority.

Numerous factors contribute to persistent health disparities among AI/AN, including limited access to health services (CDC 2010; Indian Health Services (IHS) 2009; SAMHSA 2011). AI/AN substance abuse treatment facilities [operated by Tribal government, Indian Health Service (IHS) or IHS identified programs, or facilities providing services in an AI/AN language] are predominantly located in rural areas (60 %), while only 22 % of the AI/AN population now reside in rural areas (Norris et al. 2012; SAMHSA 2009). Further compromising service delivery for AI/AN are the limited resources available to the IHS, with reported per capita health expenditures lower than Medicare, Medicaid, federal employees, and the Veteran’s Administration (Roubideaux 2005; Whitesell et al. 2012). Recent research in California demonstrated that AI participants received less individual treatment and out of program services compared to their non-AI counterparts (Evans et al. 2006). Additional barriers to treatment for this population include: inadequate transportation; limited insurance coverage; low socioeconomic status; stigma related to substance abuse; discomfort in a “westernized” treatment delivery system; and a shortage of opioid treatment programs (Dickerson et al. 2011).

Given the deleterious effects of substance use disorders and significant barriers to accessing and receiving appropriate services, computer-assisted, web-delivered interventions could improve the quality and capacity of treatment services for AI/AN communities. Implementation of evidence-based substance abuse treatment interventions has been slow (McLellan et al. 2003; Lamb et al. 1998), with key barriers including the need for adequate staff and budget resources and re-training due to high staff turnover. Further, once therapists are trained, maintaining adequate adherence to the intervention requires ongoing monitoring and supervision. Computer-delivered interventions can address some of these barriers by allowing complex, evidence-based treatments to be delivered with high fidelity and at a low cost without increasing demands on staff time or training (Carroll and Rounsaville 2010; Kiluk et al. 2011; Marsch 2012). Other potential advantages are that computer interactive programs may be less threatening to patients and provide greater anonymity, especially with sensitive or stigmatized issues such as sexual behavior and drug taking (e.g., Des Jarlais et al. 1999). Web-based technologies allow a user to access the intervention at a convenient time and place, providing greater flexibility. Finally, computerized interventions allow individuals to review necessary skills, concepts, and other therapeutic activities at their own pace and for greater amounts of time than would be possible with a therapist alone (Bickel and Marsch 2007; Newman et al. 1996). There is a limited, but growing science base for technology-based interventions to treat substance use disorders. Several randomized trials provide support for the efficacy of computer-assisted technology for addiction treatment (Bickel et al. 2008; Budney et al. 2011; Carroll et al. 2008, 2014; Chaple et al. 2014; Gustafson et al. 2014; Kay-Lambkin et al. 2011; Marsch et al. 2014), including a multi-site effectiveness trial using the same intervention as the current study (Campbell et al. 2014).

Most evidence-based practices for treatment of substance abuse have not been examined among AI/AN communities—urban, rural or reservation-based (Gone and Looking 2011; Lucero 2011; Thomas et al. 2009). More specifically, there is a significant shortage of culturally relevant interventions that can be integrated into treatment program curricula (Dickerson et al. 2011; Greenfield and Venner 2012). However, local, state, and national funding streams have recently become predicated on programs offering evidenced-based practices. Thus, substance abuse providers that serve AI/AN clients face considerable challenges to providing culturally relevant, research-supported treatments.

The community reinforcement approach (CRA; Budney and Higgins 1998) has extensive support as an intervention for individuals with alcohol and other drug use disorders (Budney and Higgins 1998; Smith et al. 2001). However, there is little published research on the acceptability or efficacy of CRA among AI/AN communities (NIAAA 2002). CRA is grounded in the idea that drugs compete with more delayed prosocial reinforcers; thus, the treatment promotes skills training to teach, encourage, and increase satisfaction with drug-free sources of reinforcement (Budney and Higgins 1998). The current pilot study aimed to assess the acceptability of an efficacious web-based version of CRA, the therapeutic education system (TES; Bickel et al. 2008; Marsch et al. 2014; Campbell et al. 2014), which was developed for mainstream, substance abuse treatment seekers, among urban AI/AN clients at two outpatient treatment programs. The goals of the study were to: (1) explore the extent to which TES would be acceptable to urban AI/AN treatment seekers in its current form; (2) assess the association between AI/AN ethnic identity and TES acceptability; and (3) determine what type of intervention modification might be warranted to increase acceptability.

Methods

Study Sites

The study was conducted at two urban outpatient substance abuse treatment programs affiliated with the National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network (CTN). One treatment program was located in the Northern Plains region; the second in the Pacific Northwest. The majority of clients served by both programs identified as AI/AN. The study staff followed principles of the Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR; Davis and Reid 1999; Israel 2000) approach which emphasizese equal partnerships, building community capacity, and long-term commitment to the community. CTN research centers have ongoing relationships and collaborations with both of these programs, promoting bi-directional communication, engagement, and trust among stakeholder groups and increased efficiency and quality of research efforts. AI/AN clinical researchers and the clinical and administrative staffs at the two treatment programs provided consultation during proposal development on issues pertaining to training, recruitment and assessment and were active collaborators throughout the study process by providing guidance on implementation, feedback on interpretation of data, and participation in manuscript development.

Participants and Study Design

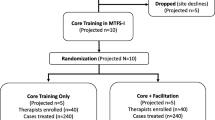

Eligible participants were men and women, 18 or older, who self-identified as AI/AN, and were within the first 30 days of their treatment episode. Twenty participants were recruited from each of the two programs January–May of 2011 (N = 40). Research staff approached clients individually or through announcements in treatment groups, briefly informed them about the purpose of the study, and asked if they were interested in participating. Interested clients completed a brief screen to assess eligibility (with verbal consent), followed by full study consent and a baseline assessment. Participants then completed 8 weeks of web-based TES using onsite computers. A follow up assessment, including a qualitative interview, was completed 1 week after the intervention phase.

The study was approved by the New York State Psychiatric Institute Institutional Review Board (IRB), the University of Cincinnati IRB and the Portland Area Indian Health Service IRB prior to study initiation and monitored annually during the trial. There are no known conflicts of interest and all authors certify responsibility for this manuscript.

Intervention

Participants received access to the therapeutic education system (TES; Bickel et al. 2008; Campbell et al. 2012) on computers at their respective treatment programs. TES addresses substance use in general and is able to individualize the various substance use-related problems with which patients may present. The TES program is self-directed so no prior computer experience is required. Participants had access to 32 interactive, multimedia modules or topics (see Table 1) considered core to the CRA approach. Topics included basic cognitive behavioral relapse prevention skills (e.g., drug refusal skills, managing thoughts about drug use, conducting functional analyses and self-management planning), skills aimed at improving psychosocial functioning (e.g., vocational and employment skills, family/social relations, financial management, communication skills, management of negative moods, time management and recreational activities), and content related to the prevention of HIV, Hepatitis and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). The first module is a training module that teaches participants how to use the system (e.g., provides an overview of the goals of TES, how TES is organized, how to respond to questions on the computer, etc.). Video clips within some modules show actors modeling the skills being taught. Short quizzes at the end of each module assess participant’s grasp of material; the pace and level of repetition of material is adjusted accordingly to maximize individual mastery of the skills and information being taught.

Participants were asked to complete four modules per week over the 8 weeks of treatment, ideally at two different visits during the week. These visits were typically linked to patients’ attendance at treatment as usual within the program. Two computers were available for use during usual treatment program hours; research staff were onsite and available for assistance and support. TES has a back-end system that tracks participant activity. Thus, participant access to TES was documented and used to assess TES exposure. Each module took approximately 15–20 min to complete and modules were completed in the same order for all participants to enhance consistency of delivery in this acceptability study.

Measures

Demographic Variables

Participant demographics and other characteristics were obtained at screening and baseline and included age, gender, race/ethnicity, tribal affiliation, education, marital status, employment, and internet use. Frequency of internet use was assessed for the prior 30 days.

Substance Use

The Timeline Follow-back method (TLFB; Sobell and Sobell 1992) was used to obtain self-report days of alcohol and other substance use (cocaine, opiates, amphetamines, methamphetamines, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, oxycodone/oxycontin, methadone, and marijuana) in the 30 days prior to baseline. The TLFB has good psychometric properties, including test–retest measurement with multiple populations (Sobell and Sobell 2000).

Cultural/Ethnic Identity

Ethnic identity was assessed using The Scale of Ethnic Experience (SEE; Malcarne et al. 2006). An assessment of ethnic identity was used to determine the extent to which study participants identified with their AI/AN culture and heritage. The SEE contains 32-items on 5-point Likert-type scales that measure the experience of ethnicity across four dimensions: ethnic identity; perceived discrimination; mainstream comfort; and social affiliation. Ethnic identity reflects a person’s attitude toward being a member of their ethnic group, ethnic pride and participation in cultural activities. Perceived discrimination reflects how a person perceives their ethnic group is treated in the U.S. Social affiliation reflects a person’s preference and comfort for interaction with their own ethnic group compared to other groups. Mainstream comfort was developed as a proxy for assimilation: that is, a person’s perception of comfort with U.S. mainstream culture. Higher scores on the subscales indicate greater endorsement of the construct. The SEE was developed for individuals of any ethnic background. Internal consistency reliability of the scale with the current sample was adequate (α = 0.72–0.82 across the four domains). Several additional questions from the Addiction Severity Index-Native American Version (Carise and McLellan 1999) were also included to capture participation in AI/AN activities and residence on reservations. These measures were completed at baseline only.

Intervention Acceptability

Acceptability of the TES intervention was based on three pre-specified outcomes: proportion of participants who agree to participate (i.e., number enrolled divided by the number approached); number of modules completed (range 0–32); and quantitative participant feedback following completion of each module. A participant feedback survey was completed on the computer immediately following the completion of each module. Participants rated each module on a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 10 (anchored from “not at all” to “very much”) consisting of seven question indices: (1) interesting, (2) easy to understand, (3) useful, (4) extent to which the intervention provided novel information, (5) satisfaction, (6) relevance, and (7) how much the participant liked it.

A semi-structured interview was conducted with each participant as part of the 1-week post treatment assessment. The interviews consisted of seven core questions with follow up probes to elicit specific information about TES acceptability in terms of content, material, and delivery, including relevance to AI/AN heritage and culture. The interview was digitally recorded and later transcribed for data analysis purposes.

Data Analysis

Means, standard deviations, and percentages were used to describe the sample on descriptive characteristics. Similarly, means and standard deviations were calculated for each “acceptability” indicator for each module, as well as an overall mean and standard deviation for each module (across all seven indicators). Associations of the mean acceptability of the five highest and five lowest rated TES modules with the high/low median splits of SEE subscales were analyzed using the non-parametric Wilcoxon significance test. The purpose of the latter analysis was to determine if theoretically informed ethnic identity constructs influenced level of acceptability among AI/AN. A median split was used given that the mean scores of the scale are not readily interpretable. These analyses were conducted using SPSS version 18.

Generalized linear models (using identity link function for normal data) on module acceptability were applied to examine the associations among the order of module completion (continuous, 2–32), the phase of intervention completion (i.e., earlier: modules 2–16 vs later: modules 17–32) and overall acceptability ratings among (1) whole sample and (2) those that completed more than half the modules (>16). These analyses were conducted using PROC GLIMMIX in SAS 9.3.

Qualitative interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed, and entered into Atlas.ti v5.1® for the purpose of coding and analyzing text. A codebook was developed prior to data collection representing general themes of interest that corresponded with the interview guides. Two interviews were initially reviewed and coded by all members of the qualitative analysis team (comprised of three research team members and two staff from the treatment programs, one of whom was AI/AN). An iterative process of discussion and review of code definitions and application was used to reach consensus and finalize the codebook. Two team members then coded the remaining interviews and again the analysis team met to review final codes and discuss content found within each of the themes.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Forty participants were enrolled in the study, 20 at each treatment program. Twenty-six participants (65 %) completed the 1-week post treatment follow up assessment and interview. The mean age was 37.5 (SD = 10.9) years, and about half of the sample was women (47.5 %). The vast majority reported alcohol as the primary substance of abuse (77.5 %), followed by methamphetamines (10.0 %), opiates/heroin (7.5 %), and cannabis (5.0 %). The mean number of days of alcohol and drug use in the past 30 was 2.5 (SD = 7.6); 80 % of the sample reported 0 days of drug and alcohol use in the past 30. Over half reported a high school degree or equivalent (57.5 %), 25.0 % had less than a high school degree, and 17.5 % greater than a high school degree. About one-third of the sample reported working full or part-time in the prior month (35.0 %) and almost half (47.5 %) were under or unemployed.

Most participants reported living on a reservation at some point in their lives (72.5 %) and almost half were familiar with their native language (47.5 %). Slightly over half (55.0 %) accessed the internet at least once in the month prior to study enrollment and 42.5 % of the sample accessed the internet at least once per day. The following means were found using the Scale of Ethnic Experience, with higher scores indicating greater endorsement of the concept (range 1–5): ethnic identity M = 3.78 (SD = 0.7); perceived discrimination M = 3.44 (SD = 0.6); mainstream comfort M = 3.35 (SD = 0.7); and social affiliation M = 3.06 (SD = 0.7).

TES Acceptability: Proportion Enrolled and Module Completion

Sixty-eight clients were approached for the study and 40 enrolled (58.8 %). All but three participants completed at least one module. Of those that completed modules, the mean number was 18.6 [Standard Deviation (SD) = 9.2], with a range of 4–32.

TES Acceptability (Quantitative Indicators)

Participants reported the following mean ratings for each acceptability indicator (range 0–10; higher scores indicated greater acceptability): 8.33 (SD = 2.1) interesting; 8.54 (SD = 1.9) usefulness; 8.26 (SD = 2.2) new information; 8.49 (SD = 1.9) satisfaction; 8.39 (SD = 2.2) relevance; 8.22 (SD = 2.2) likability; and 7.43 (SD = 3.5) understanding. Each individual TES module was also rated for overall acceptability, again on a scale from 0 to 10. No modules received an overall mean rating of less than 6, the a priori score for indicating definite need for adaptation. The division at the midway point of the scale (<5 vs. 6 or greater) allows for a general alignment with one of the endpoints for each question (e.g., not interesting vs. very interesting). The lowest rated module was Self-management Planning (M = 7.76) and the highest was Drug Use, HIV, and Hepatitis (M = 9.39) (see Table 2).

There was no significant difference detected in module ratings up through module 16 based on whether participants completed more than half or less than half of the modules (see Fig. 1). Further, there was not a significant increase in module acceptability ratings over time for modules 2–16 among the total sample. Finally, of those who completed more than half of the modules (n = 22), acceptability for the first half (2–16) was significantly lower than for the second half (modules 17–32) (b = 0.242, se = 0.108, t-value = 2.25, p = .025). TES Acceptability by Ethnic Identity. Table 3 displays associations between domains of the Scale of Ethnic Experience (dichotomized as high versus low) and overall acceptability among the five lowest and five highest rated modules. Participants with greater perceived discrimination rated the Receiving Criticism module lower (z = 2.45, p = .014) and participants with greater mainstream comfort rated Self-management Planning higher (z = 1.97, p = .049). There were no other significant associations detected.

TES Acceptability (Qualitative Interviews)

Two primary themes emerged when examining in-depth interviews. First, participants found TES information relevant to addiction treatment and recovery (endorsed by 21 of 26 participants). This overall acceptability of relapse prevention and other cognitive skills training was noted by several participants: “Well, being able to deal with drug and alcohol addiction. I think that’s apparent in any culture though.” and “Everything that was in these modules were things—I mean, there was something in each one of them I did not know.” The content appeared to complement outpatient substance abuse treatment curricula and provided new information that participants had not received previously, especially content related to HIV and other STI prevention.

The second main theme that emerged was that TES could be improved through better AI/AN representation within module content and presentation (endorsed by 16 of 26 participants). This was summarized by one participant: “I didn’t think it was culturally specific. But when you say culture, I think of sweat lodges, I think of ceremonies, I think of powwows, I think of drumming and singing. Culturally, I don’t see it.” Another participant put forth that “…some Natives will only receive the information if it’s about us or for us, you know? Maybe they’ll put it off because they’re just thinking it’s another way the White man’s trying to tell us how to do things, but if it’s about Natives, maybe we’ll accept it more and use more of it and take it as a tool […].”

Specific suggestions supplied within the interviews included: (1) inserting humor, Native words or slang, and storytelling; (2) using Native actors in videos and for voice over; (3) references to and depictions of nature and the natural world; (4) scenarios for the videos that were more relevant to AI/AN experience (one participant described the, “use of native themes in scenes when in the home such as Native art and such”). One participant suggested showing a video about returning to the reservation to visit family, confronting and dealing with alcohol and drug use; (5) incorporating Native spirituality, especially as it relates to effective coping. Examples of spirituality included prayer, sweats, singing, and drumming; and (6) removing specific content that might be counter to Native culture. For example, a video clip in TES suggests using direct eye contact when refusing drugs; this was seen as opposite to many AI/AN cultures that rely more heavily on non-verbal communication and view direct eye contact as disrespectful. A participant more generally explained “…a lot of times people would think communication just comes from […] your mouth, but it also comes with your body language and your eye contact, and that pretty much speaks louder than what’s coming out of your mouth.”

Discussion

This study offers important information about the acceptability of an efficacious, web-based intervention among AI/AN clients receiving outpatient substance abuse treatment. Although alcohol and drug abuse disproportionately impact AI/AN communities, very few evidence-based treatments have been developed or adapted for AI/AN clients. Given the rural locations of many Indian reservations, as well as treatment accessibility issues facing urban-dwelling AI/AN peoples, a web-based treatment offers compelling advantages and benefits.

Overall findings suggest that core TES content is acceptable among a diverse AI/AN client population who agreed to participate in this study. AI/AN clients gave the highest ratings of acceptability to TES modules that included HIV/STI information, as well as managing triggers that can lead to risky sexual or drug using behavior. It may be that this information was not widely available within their treatment programs, a conclusion supported via anecdotal conversation with research staff. Modules receiving lower ratings tended to be those completed earlier; lower ratings may reflect features of TES functionality, such as getting comfortable with the interface and answering questions to demonstrate learning to be able to move from one module to the next. Initial, lower acceptance rates (and the relatively low use of the internet in the population at baseline) may indicate that web-based interventions need more comprehensive introduction.

Earlier modules also included topics on functional analysis (analysis of sequences of thoughts, feelings and events leading up to episodes of substance use) and managing thoughts about using alcohol and illicit substances and urges to use. Specific details of these modules, such as person and place triggers may have been less culturally relevant or appeared more didactic. Since participants were early in their treatment episode, these topics may not have corresponded to their readiness to make changes. Alternatively, given the high 30-day abstinence rates of the sample, these early relapse prevention topics may have been less relevant or useful. Higher ratings for later modules could reflect early attrition by individuals who were less likely to find TES acceptable. However, this was not borne out in analyses examining module acceptability among those who completed less than or more than half the modules. Research staff noted that most individuals who did not complete the research study also had left the treatment program, corroborating this quantitative finding. This would suggest a lack of interest or motivation in substance abuse treatment overall, rather than a specific reaction to the web-delivered treatment.

Only one module, Functional Analysis, received a low score (6) on the acceptability measure “easily understood.” This module walks clients through a multi-step analysis of events or emotions that can trigger relapse/substance use. It is relatively dense in terms of information and may contain off-putting academic “jargon.” TES modules are deliberately ordered based on the accumulation of specific cognitive behavioral skills, so placing functional analysis later in the order is not recommended. Thus, this particular module should be reviewed for more specific modification and possible cultural adaptation.

Findings specific to the qualitative data suggest that moderate adaptation would improve acceptability and engagement in TES among AI/AN clients. Users might relate to the content more easily if video clips and voice-over narration are more representative of AI/AN culture. As others have noted, services for AI/AN that marry traditional or cultural practices, such as strengths-based cultural assets, with evidence-based addiction treatments produce better effects (Dickerson et al. 2011; Etz et al. 2012; Kropp et al. 2013). Adaptation of existing treatments, however, must take into account that AI/AN communities are diverse—with over 280 separate cultural groups representing 560 tribes (Gray and Nye 2001; Bureau of Indian Affairs 2010). Thus, adaptation either needs to account for differences in AI/AN culture with regard to health disparities, access to resources, geography, culture, tradition, exposure to post-colonial trauma and issues related to substance abuse (Thomas et al. 2011) or be more generic in terms of providing the faces, voices and elements of culture and spirituality that could resonate across tribal affiliations. Overall, increasing cultural congruency and compatibility could lead to stronger acceptability and treatment program adoption within AI/AN communities and programs serving large numbers of urban AI/AN, enhancing the ability of clients to integrate information into their daily lives.

Few significant relationships emerged between AI/AN cultural identity, as measured by the Scale of Ethnic Experience, and the acceptability of TES. This may in part be due to the limited sample size in this pilot study and the relatively limited variability in module ratings. Further, because these were exploratory analyses, corrections for multiple tests of association were not applied but should be considered when thinking about implications of these findings. Acceptability of Self Management Planning was significantly related to higher Mainstream Comfort, i.e., feeling assimilated into American culture. This module might particularly benefit from adaptation to increase acceptability among more traditional or less assimilated AI/AN people. Of interest, Receiving Criticism was rated higher among those who endorsed greater perceived discrimination. This module may have presented useful coping strategies for individuals who perceive or experience more discrimination.

The Scale of Ethnic Experience demonstrated good internal consistency reliability in this sample, comparable to that in African American, Caucasian American, Filipino American and Mexican–American groups who participated in the scale development studies (Malcarne et al. 2006). These pilot results suggest that Scale of Ethnic Experience may have potential for further use in AI/AN studies of ethnic identity and experience and additional research is warranted.

Limitations

This study was innovative in its attempt to assess the acceptability of an efficacious, web-based psychosocial intervention among an underrepresented population in substance abuse research. However, findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, the sample was diverse, representing 19 distinct tribal affiliations. Although this demonstrates acceptability of TES across a diverse sample, the findings may not be generalizable to all AI/AN or to any one AI/AN tribal group. Second, 1-week post treatment follow up rates (70 %) were comparable to other substance abuse research studies, however conclusions should be tempered by the attrition, which could bias the findings. Efforts to track treatment dropouts were limited given staffing resources. Similarly, clients that were not interested at all in the study (i.e., did not agree to the initial screening assessment) may be different and possibly less likely to find a computer-assisted, web-delivered intervention acceptable. Third, participants accessed the intervention onsite; this study is not able to assess how frequently participants would have accessed the intervention using offsite computers. Finally, associations between ethnic identity and module acceptability may be underpowered due to modest sample size. That said, the inclusion of an ethnic identity measure, especially one with multidimensional cultural domains, is a strength of the current study and indicates further promise for more widespread use of this web-delivered treatment.

Conclusion and Future Direction

Ensuring AI/AN communities have access to culturally appropriate and acceptable evidence-based substance abuse treatment is long overdue, especially in light of the impact that substance abuse has had in this population (Dickerson et al. 2011) and the increasing demands on programs to implement empirically supported treatments. Findings from this pilot study suggest that core TES content and web-delivery format are acceptable among a diverse AI/AN client population receiving treatment in urban settings. The findings also suggest acceptability could be improved (and perhaps better integrated and utilized) if the content included representation of traditional practices, culture, and Native peoples. Although TES was not culturally tailored to a specific racial or ethnic group, adaptation to enhance relative advantage (i.e., degree to which a new intervention is perceived to be superior to the current practice) and compatibility (i.e., consistency with program values and perceived need) has been shown to enhance the likelihood of adoption and implementation (Rogers 2003). Findings suggest that moderate adaptations of TES are indicated related to delivery and presentation (e.g., casting the intervention in a Native voice by using AI/AN actors for voice and video components; use of stories as opposed to “academic” presentations; inclusion of AI/AN cultural representation). These adaptations could very likely be completed while maintaining fidelity to the core theoretical underpinnings of CRA. The content itself was generally experienced as relevant and well accepted with a few exceptions, such as the meaning and use of direct eye contact. Future research should incorporate questions specific to cultural relevance as part of acceptability.

An evidence-based intervention that is web-based and culturally-informed could address barriers to treatment access and dissemination among AI/AN communities, given its ease of implementation, limited staff training (given constricted resources), and flexibility in how TES is integrated into program curricula (Novins et al. 2011). Future research should focus on a collaborative, community-based adaptation process between intervention developers/researchers, treatment providers, and AI/AN community stakeholders. Future research should also target key implementation factors such as provider attitudes, funding (including reimbursement for non face-to-face services), and broadband internet access, including the availability and uptake of smart phone technology, in rural or reservation-based treatment programs.

References

Advancing Indian health care: Hearing before the committee on Indian affairs United States Senate, 111th Congress. (2009). U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

Beals, J., Manson, S. M., Whitesell, N. R., Spicer, P., Novins, D. K., Mitchell, C. M., et al. (2005). Prevalence of DSM-IV disorders and attendant help-seeking in 2 American Indian reservation populations. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(1), 99.

Bickel, W. K., & Marsch, L. A. (2007). A future for drug abuse prevention and treatment in the 21st century: Applications of computer-based information technologies. In J. Henningfield, P. B. Santora, & W. K. Bickel (Eds.), Addiction treatment: Science and policy for the 21st century (pp. 35–43). Baltimore, MD: The John Hopkins University Press.

Bickel, W. K., Marsch, L. A., Buchhalter, A., & Badger, G. (2008). Computerized behavior therapy for opioid dependent outpatients: A randomized, controlled trial. Experimental Clinical Psychopharmocology, 16, 132–143.

Budney, A. J., Fearer, S., Walker, D. D., Stanger, C., Thostenson, J., Grabinski, M., et al. (2011). An initial trial of a computerized behavioral intervention for cannabis use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 115(1–2), 74–79.

Budney, A., & Higgins, S. (1998). Therapy manuals for drug addiction, a community reinforcement plus vouchers approach: Treating cocaine addiction. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Bureau of Indian Affairs. (2010). Indian entities recognized and eligible to receive services from the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. Department of the Interior (Ed.) (Vol 75). Washington, DC: Federal Register, 60810–60814.

Campbell, A. N. C., Nunes, E. V., Matthews, A. G., Stitzer, M., Miele, G. M., Polsky, D., et al. (2014). Internet-delivered treatment for substance abuse: A multi-site randomized controlled clinical trial. American Journal of Psychiatry. Advance online publication. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13081055.

Campbell, A. N. C., Nunes, E. V., Miele, G. M., et al. (2012). Design and methodological considerations of an effectiveness trial of a computer-assisted intervention: An example from the NIDA Clinical Trials Network. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 33(2), 386–395.

Carise, D., & McLellan, A. T. (1999). Increasing cultural sensitivity of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI): An example with Native Americans in North Dakota (Special Report). Rockville, MD: Center for Substance Abuse Treatment.

Carroll, K. M., Ball, S. A., Martino, S., Nich, C., Babuscio, T. A., Nuro, K. F., et al. (2008). Computer-assisted delivery of cognitive-behavioral therapy for addiction: A randomized trial of CBT4CBT. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(7), 881–888.

Carroll, K. M., Kiluk, B. D., Nich, C., Gordon, M. A., Portnoy, G. A., Marino, D. R., et al. (2014). Computer-assisted delivery of cognitive-behavioral therapy: Efficacy and durability of CBT4CBT among cocaine-dependent individuals maintained on methadone. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171, 436–444.

Carroll, K. M., & Rounsaville, B. J. (2010). Computer-assisted therapy in psychiatry: Be brave—it’s a new world. Current Psychiatry Reports, 12(5), 426–432.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. (2012). Health disparities in HIV/AIDS, viral hepatitis, STDs, and TB: American Indians and Alaska Natives. Retrieved January 29, 2012 from http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/healthdisparities/AmericanIndians.html.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], Office of Minority Health & Health Disparities. (2010). American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) populations. http://www.cdc.gov/omhd/populations/aian/aian.htm#Disparities.

Chaple, M., Sacks, S., McKendrick, K., Marsch, L. A., Belenko, S., & Leukefeld, C. (2014). Feasibility of a computerized intervention for offenders with substance use disorders: A research note. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 10, 105–127.

Chartier, K., & Caetano, R. (2010). Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research. Alcohol Research & Health: The Journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 33(1–2), 152–160.

Compton, W. M., Thomas, Y. F., Stinson, F. S., & Grant, B. F. (2007). Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 566–576.

Davis, S. M., & Reid, R. (1999). Practicing participatory research in American Indian communities. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 69(4), 755S.

Des Jarlais, D. C., Paone, D., Milliken, J., Turner, C. F., Miller, H., Gribble, J., et al. (1999). Audio-computer interviewing to measure HIV risk behaviour among injecting drug users: A quasi-randomised trial. Lancet, 353, 1657–1661.

Dickerson, D. L., Spear, S., Marinelli-Casey, P., Rawson, R., Libo, L., & Hser, Y. (2011). American Indians/Alaska Natives and substance abuse treatment outcomes: Positive signs and continuing challenges. Journal of Addiction Disorders, 30(1), 63–74.

Etz, K. E., Arroyo, J. A., Crump, A. D., Rosa, C., & Scott, M. S. (2012). Advancing American Indian and Alaska Native substance abuse research: Current science and future directions. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 38(5), 372–375.

Evans, E., Spear, S. E., Huang, Y., & Hser, Y. (2006). Outcomes of drug and alcohol treatment programs among American Indians in California. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 889–896.

Gone, J. P., & Looking, P. E. C. (2011). American Indian culture as substance abuse treatment: Pursuing evidence for a local intervention. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 43(4), 291–296.

Gone, J. P., & Trimble, J. E. (2012). American Indian and Alaska Native mental health: Diverse perspectives on enduring disparities. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8, 131–160.

Gray, N., & Nye, P. S. (2001). American Indian and Alaska Native substance abuse: Co-morbidity and cultural issues. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 10(2), 67–84.

Greenfield, B. L., & Venner, K. L. (2012). Review of substance use disorder treatment research in Indian Country: Future directions to strive toward health equity. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 38(5), 483–492.

Gustafson, D. H., McTavish, F. M., Chih, M., Atwood, A. K., Johnson, R. A., Boyle, M. G., et al. (2014). A smartphone application to support recovery from alcoholism: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. Advance online publication. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4642.

Hasin, D. S., Stinson, F. S., Ogburn, E., & Grant, B. F. (2007). Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(7), 830–842.

Indian Health Services (IHS). (2009). IHS fact sheets: Indian health disparities. http://info.ihs.gov/Disparities.asp.

Israel, B. A. (2000). Community-based participatory research: Principles, rationales and policy recommendations. In L. R. O’Fallon, F. L. Tyson, & A. Dearry (Eds.), Successful models of community-based participatory research (pp. 16–29). Washington, D.C.: National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Kay-Lambkin, F. J., Baker, A. L., Kelly, B., & Lewin, T. J. (2011). Clinician-assisted computerised versus therapist-delivered treatment for depressive and addictive disorders: a randomised controlled trial. Medical Journal of Australia, 195, S44–S50.

Kiluk, B. D., Sugarman, D. E., Nich, C., Gibbons, C. J., Martino, S., Rounsaville, B. J., et al. (2011). A methodological analysis of randomized clinical trials of computer-assisted therapies for psychiatric disorders: Toward improved standards for an emerging field. American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(8), 790–799.

Kropp, F., Somoza, E., Illleskov, M., Granados-Bad Moccasin, M., Moore, M., Lewis, D., et al. (2013). Characteristics of Northern Plains American Indians seeking substance abuse treatment in an urban, non-tribal clinic: A descriptive study. Community Mental Health Journal, 49(6), 714–721.

Lamb, S., Greenlick, M. R., & McCarty, D. (1998). Bridging the gap between practice and research: Forging partnerships with community-based drug and alcohol treatment. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Lucero, E. (2011). From tradition to evidence: Decolonization of the evidence-based practice system. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 43(4), 319–324.

Malcarne, V. L., Chavira, D. A., Fernandez, S., & Liu, P. (2006). The Scale of Ethnic Experience: Development and psychometric properties. Journal of Personality Assessment, 86(2), 150–161.

Marsch, L. A. (2012). Leveraging technology to enhance addiction treatment and recovery. Journal of Addiction Disorders, 31(3), 313–318.

Marsch, L. A., Guarino, H., Acosta, M., Aponte-Melendez, Y., Cleland, C., Grabinski, M., et al. (2014). Web-based behavioral treatment for substance use disorders as a partial replacement of standard methadone maintenance treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 46, 43–51.

McLellan, A. T., Carise, D., & Kleber, H. D. (2003). Can the national addiction treatment infrastructure support the public’s demand for quality care? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 25, 117–121.

National Center for Health Statistics. (2012). Health, United States, 2011: With Special Feature on Socioeconomic Status and Health. Hyattsville, MD.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [NIAAA] (2002). Alcohol and minorities: An update. Alcohol Alert, 55. Rockville, MD: Author.

Newman, M. G., Kenardy, J., Herman, S., & Taylor, C. B. (1996). The use of hand-held computers as an adjunct to cognitive-behavior therapy. Computers in Human Behavior, 12, 135–143.

Norris, T., Vines, P., & Hoeffel, E. (2012). The American Indian and Alaska Native Population: 2010. Washington, DC: United States Census bureau.

Novins, D. K., Aarons, G. A., Conti, S. G., Dahlke, D., Daw, R., Fickenscher, A., et al. (2011). Use of the evidence base in substance abuse treatment programs for American Indians and Alaska Natives: Pursuing quality in the crucible of practice and policy. Implementation Science, 6, 63. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-6-63.

Pleis, J. R., Ward, B. W., Lucas, J. W. (2010). Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2009. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Statistics, 10(249).

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). New York: Free Press.

Roubideaux, Y. (2005). Beyond red lake—The persistent crisis in American Indian health care. The New England Journal of Medicine, 353(18), 1881–1883.

Russo, D., Purohit, V., Foudin, L., & Salin, M. (2004). Workshop on alcohol use and health disparities 2002: A call to arms. Alcohol, 32(1), 37–43.

Smith, J. E., Meyers, R. J., & Miller, W. R. (2001). The community reinforcement approach to the treatment of substance use disorders. American Journal of Addictions, 10, S51–S59.

Sobell, L. C., & Sobell, M. B. (1992). Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In J. Allen & R. Z. Litten (Eds.), Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biological methods (pp. 41–72). Totowa, NJ: Humana Press.

Sobell, M. B., & Sobell, L. C. (2000). An excellent springboard. Addiction, 95(11), 1712–1715.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA]. (2010). Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Volume I. Summary of National Findings (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-4586 Findings). Rockville, MD, Author.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2011). Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. NSDUH Series H-41, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 11-4658. Rockville, MD, Author.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], Office of Applied Studies. (2009). The National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS) Report. Rockville, MD: Author.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration[SAMHSA], Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2012). Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 2000–2010. National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services. DASIS Series S-61, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-4701. Rockville, MD: Author.

Thomas, L. R., Donovan, D. M., Sigo, R. L. W., Austin, L., & Marlatt, G. A. (2009). The community pulling together: A tribal community-university partnership project to reduce substance abuse and promote good health in a reservation tribal community. Journal of Ethnicity and Substance Abuse, 8(3), 283–295.

Thomas, L. R., Rosa, C., Forcehimes, A., & Donovan, D. M. (2011). Research partnerships between academic institutions and American Indian and Alaska Native tribes and organizations: Effective strategies and lessons learned in a multisite CTN study. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 37(5), 333–338.

Whitesell, N. R., Beals, J., Crow, C. B., Mitchell, C. M., & Novins, D. K. (2012). Epidemiology and etiology of substance use among American Indians and Alaska Natives: Risk, protection, and implications for prevention. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 38(5), 376–382.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network (CTN), National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) U10 DA13035 (Edward V. Nunes and John Rotrosen), U10 DA013732 (Theresa Winhusen), and U10 DA015815 (Dennis McCarty and James L. Sorensen). This work was also supported by NIDA K24 DA022412 (Edward V. Nunes). The authors acknowledge the support of the clinical and administrative staff at the two participating community treatment programs, the work of the local research teams, including protocol managers, quality assurance monitors, research coordinators, and research assistants, and the generous commitment of time from research participants. Development of the research protocol included input from staff at the Center for Clinical Trials Network; Dr. Kamilla Venner (Athabascan), University of New Mexico; and Dr. Duane Mackey (Santee Sioux) (deceased), Prairielands ATTC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Campbell, A.N.C., Turrigiano, E., Moore, M. et al. Acceptability of a Web-Based Community Reinforcement Approach for Substance Use Disorders with Treatment-Seeking American Indians/Alaska Natives. Community Ment Health J 51, 393–403 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-014-9764-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-014-9764-1