Abstract

The emphasis on care in the community in current mental health policy poses challenges for community mental health professionals with responsibility for patients who do not wish to receive services. Previous studies report that professionals employ a range of behaviors to influence reluctant patients. We investigated professionals’ own conceptualizations of such influencing behaviors through focus groups with community teams in England. Participants perceived that good, trusting relationships are a prerequisite to the negotiation of reciprocal agreements that, in turn, lead to patient-centred care. They described that although asserting professional authority sometimes is necessary, it can be a potential threat to relationships. Balancing potentially conflicting processes—one based on reciprocity and the other on authority—represents a challenge in clinical practice. By providing descriptive accounts of micro-level dynamics of clinical encounters, our analysis shows how the authoritative aspect of the professional role has the potential to undermine therapeutic interactions with reluctant patients. We argue that such micro-level analyses are necessary to enhance our understanding of how patient-centered mental health policy may be implemented through clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the last few decades, UK mental health policy, like that in most Western industrialized countries, has focused on deinstitutionalizing services. Consequently, there has been a sharp increase in the number of people with severe and enduring mental illness receiving services in the community. For professionals, this presents challenges in how to respond when patients for whom they hold responsibility do not wish to receive services. Mental health legislation has been amended to allow for involuntary community treatment (Rugkåsa and Burns 2009; Sjöström et al. 2011), and new models for service delivery are developing that monitor patients closely while seeking to assist them to achieve stability, insight and independence (Burns and Firn 2002; Davies 2002; Moser 2007). Mental health services are increasingly delivered via case management approaches by multidisciplinary teams consisting of psychiatrists, nurses, psychologists, social workers, support workers and occasionally other professionals such as occupational therapists (Burns and Firn 2002; Burns 2004; Stanhope and Matejkowski 2010). The overarching therapeutic aim of mental health professionalsFootnote 1 working with patients with severe mental illness is to prevent relapse and readmission to hospital by ensuring adherence to treatment and by addressing patients’ wider needs. Increasingly, services focus on assisting ‘recovery’, which refers to a patient’s ability to identify their needs, manage their symptoms and live fulfilling lives with a mental illness (Anthony 1993). To achieve these aims, professionals become involved in a wide range of patients’ daily activities and interact with family members and those services with a remit for housing, social security benefits and so forth (Davies 2002; Szmukler and Appelbaum 2008). This approach to service delivery means that professionals are often involved across different spheres of patients’ personal lives and take on roles that are both empowering and controlling (Moser 2007; Angell and Mahoney 2007). Different types (and degrees) of influence or pressure are applied, and these have been described as spanning:

A continuum of restrictiveness that includes verbal encouragement or admonition (“That behaviour keeps getting you into trouble”), contingent support or contracting (“Once you manage your medication reliably, we’ll see about getting you that job”), involvement of others (“You seem to need help managing your money”), informal coercion (“You can enter the hospital voluntarily, or we will have to commit you”), or formal coercion (Neale and Rosenheck 2000, p. 499).

Patients might, of course, perceive the ways in which professionals seek to influence their behavior as helpful or caring but also as pressurizing or coercive (Neale and Rosenheck 2000). A small but growing literature investigates patients’ experiences of various influencing behaviors. Monahan et al. (2005) focus specifically on how certain areas of social welfare (housing provision, child custody and social security benefits) and the criminal justice system can be used as ‘leverage’ by service providers, that is, where access/avoidance is made contingent on adherence to treatment. They found that more than half of patients in US services have experienced such leverage. An adaptation of Monahan’s study in England showed that these forms of leverage are also experienced here, albeit less frequently, with around a third reporting them (Burns et al. 2011). In addition to ‘leverage’, researchers also refer to ‘treatment pressure’ (Szmukler and Appelbaum 2008), ‘therapeutic limit setting’ (Neale and Rosenheck 2000) and ‘informal coercion’ (Appelbaum and Le Melle 2007). In this article, we use the descriptive ‘influencing behaviors’ as a catch-all term to refer to the full range of techniques or strategies used intentionally, or occasionally unintentionally, in attempts to make patients adhere to treatment and engage in therapeutic activities.

Not much attention has been given in the literature to community mental health professionals’ own perspectives on how they exert influence over patients (Angell et al. 2006). A small number of studies, largely from the US, identify and measure the use of different influencing behaviors. We summarize these in Box 1.

Whereas it is important to ascertain which influencing behaviors are used and to what extent, there remains a gap in the literature regarding how these behaviors or strategies are conceptualized by those applying them (Neale and Rosenheck 2000). In this article, we present an analysis of focus group discussions in which mental health professionals in community teams in England described what they wanted patients to do and how they attempted to get them to do it. Our analysis focuses on participants’ descriptions of their relationships with patients, a recurrent theme in the focus groups and a central feature in the current discourse on mental health services in the United Kingdom (Mind 2008; Shepherd et al. 2009; Department of Health 2011; Gillard et al. 2012; Kirsh and Tate 2012) and elsewhere (Curtis and Hodge 1995; Davies 2002). In this discourse, the ideal relationship is presented as supporting recovery and moving beyond a more narrow focus on treatment to foster ‘patient-centered care’ (Anthony 1993; Department of Health 2009). The (albeit limited) literature on health professionals’ descriptions of their relationships vis-à-vis patients suggests that professionals also view these relationships as central mechanisms for the delivery of care and that they perceive their approach to be patient-centered (Seale et al. 2005). Indeed, in the literature, mental health professionals (particularly nurses) describe how building trusting relationships is a core aspect of their practice (Olofsson et al. 1995; Magnusson and Severinsson 2004; Seale et al. 2005) and that coercive measures often result from a failure to achieve this (Olofson and Norberg 2001; Seale et al. 2005). The development of trusting relationships can be impeded by difficulties in balancing trust building with insistance on change (Lützén 1998; Neale and Rosenheck 2000; Nath et al. 2012), and with moving in and out of the authoritative part of the professional role (Seale et al. 2005). We return to these issues below where we apply the notion of reciprocity (Mauss 1990 [1922]) to an analysis of these dynamics. We also discuss how the context within which these relationships occur, where one party ultimately holds authority to compel the other, makes them unlike many other social relationships and, arguably, ones where reciprocal exchange cannot be balanced (Øye 2010) because the relationships are played out in what can be described as a ‘coercion context’ (Sjöström 2005). Given the central role of therapeutic relationships in current mental health policy, investigating professionals’ conceptualizations of these relationships might, we argue, shed light on how such policy is implemented in practice (Nath et al. 2012).

Methods

The data reported here are from focus groups conducted as part of a research program on ‘leverage’ in community mental health services in England. A total of 417 patients in one NHS Trust area took part in structured interviews (Burns et al. 2011), and 39 of them were also interviewed in-depth (Canvin et al. 2013). We then conducted focus group interviews with staff in a purposive sample of six of the community teams from which the patient sample was drawn. The aim was to investigate how influencing behaviors were conceptualized by professionals. We used naturalistic groups (i.e. existing groups, in this case, community teams, rather than people brought together for the purpose of research) to encourage participants to express their own views and comment on those of others through discussion of real cases as opposed to hypothetical or abstract situations (Kitzinger 2005). We moderated the groups to obtain reflection more than consensus, and, because we were investigating current service delivery, attention was primarily directed towards team approaches rather than individual ones.

Between three and 13 participants attended the six groups, and in total 48 people (16 men, 32 women) took part, from a range of professions as outlined in Table 1. Each participant received information about the research and signed a consent form. The sessions were facilitated by AS, with another member of the research team observing and taking notes.

We designed a topic guide based on a review of the literature and the qualitative interviews with the patient sample. The guide was designed to investigate participants’ experience of using leverage (as described above), other types of influencing behaviors and general interactions with reluctanct patients and their families. To facilitate discussion about their own practice, each group was asked two opening questions:

-

What are the things you want patients to do?

-

What do you do to get them to do those things?

Responses to these two questions were recorded on a flip chart to act as prompts in the discussions that followed, and the topic guide probed for case examples throughout. The focus groups were audio recorded, and the audio files range from 50 to 80 min in duration (average 60 min). Files were transcribed ad verbatim, and the transcripts imported into the qualitative software package Atlas.ti (1999) to aid analysis. Each author read the transcripts and made a draft coding plan. We discussed these in detail before reaching consensus on a coding framework. Subsequent adjustments to this framework were discussed among the authors before they were implemented. Some of the final codes corresponded to the themes included in the topic guide or derived from theoretical interests, whereas others emerged from the data. This article is based on thematic analyses of the coding reports, using the constant comparison method (Glaser 1965; Denzin and Lincoln 1993). The findings we present below are accompanied by quotes from the transcripts to illustrate and validate our interpretations (Smart 2007). Each quote is identified by an alias name, profession and the focus group in which that person participated (FG1–6). Names of patients and organizations have been changed or removed.

Ethical approval was given by an NHS Resarch Ethics Committee (Ref. 05/Q1604/180). All authors certify responsibility for the study and this article and that they hold no conflict of interest.

Results

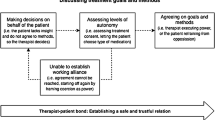

When asked: ‘What are the things you want patients to do?’, participants’ replies broadly included wanting patients to take medication as prescribed, to engage with the team and keep appointments, and to take responsibility for leading more stable, healthy lives. When we asked participants how they tried to achieve these goals, they provided rich, contextual accounts of how, and in what circumstances, they sought to exert influence over patients. We identified three categories of influencing behaviours: building trusting relationships; negotiating agreements; and, asserting authority.

Building Trusting Relationships

The quality of their relationships emerged as the central way of attempting to influence patients to achieve treatment aims. Achieving good, trusting relationships required the participants to “be honest”, “interested”, “fair”, “empathetic”, “reliable” and “consistent” all of which might, of course, be perceived as an ideal for any social relationship. Trust, often built up over time, was seen as fostering continued contact with services:

‘Cause we work with some of our patients for quite a long time – to work with somebody that they like and they trust and they can talk to – that often retains people in treatment, actually. When things are tough they will come and see you (Lisa, nurse, FG3).

“Good” relationships were described as providing a platform for achieving “engagement” and for educating, encouraging or reminding patients to take treatment, such as when the professional could reflect on past experiences with the patient:

“Last September, this is what you were doing: You were in employment; you were much more active, seeing the family. That was obviously a good place to be. Let’s try and get back to that again.” So it’s reminding them that they were well and there was a reason for them being well and again, “At that time you were taking 150 mg of Clozapine. [Now] you’re only taking 50. Do you think there’s something relating to that?” (Marko, nurse, FG4)

Being attuned to the patients’ situations and taking their concerns and priorities into account was perceived as crucial to get patients to work “with” professionals:

[One should be] prepared to think outside the box, you know, maybe do the unconventional things for them. I think it’s difficult to give examples specifically but it might be about, you know, phoning up somebody on their behalf, writing a letter, just doing stuff that will improve their quality of life, which might be secondary to a mental health agenda. But doing those things, you know, proving your worth to them as a practitioner and part of the service. To ultimately keep them engaged with the service as well (Alice, occupational therapist, FG6).

Focusing on patients’ priorities and perspectives was not only perceived to provide necessary information about the patient (including why he or she might be reluctant to take treatment), but also to form part of the reciprocal ‘give and take’ of social relationships that could facilitate longer-term aims:

Finding out what people’s priorities are for them and trying to have as much focus on that, even though it might not be my biggest concern. Because I think if you can find out what people want and show them that you can be effective in helping them improve what they want to improve then you might also get to work on the other things that we see as more of a priority. (Emma, nurse, FG6)

Addressing practical issues was often believed necessary before pursuing other aims:

I can’t go and do anxiety management with somebody because of the money issues that she’s got [if] the bailiffs are coming around next week. […] And so sometimes you’ve got to do the practical things [first] (Emma, nurse, FG6).

Participants described how they assisted patients who neglected themselves to keep their homes tidy and clean, attend to their diet and personal hygiene and to take exercise. Educational activities and employment was also encouraged and supported. Participants assisted with paperwork and other forms of communication with other agencies and sometimes helped patients “fight off eviction” through extensive liaison with housing providers. Some participants explained that they occasionally needed to apply assertive approaches to ensure that patients received the support to which they were entitled:

Sometimes it’s not so much signposting and it’s, [pause] ‘dragging’ is not the right word but, I mean, it’s going along with them and, you know, actually taking them, you know, sometimes make all the appointments for them and going and picking them up and taking them rather than just saying, you know, “There’s so and so, why don’t you go and try that?” They wouldn’t do it (Mike, nurse, FG1).

Several participants indicated how offering something outside patients’ expectations, such as going out for coffee or meals or doing practical tasks, helped to create reciprocal obligations, which in turn could pave the way for constructive interactions:

AS: If you do do these things, mowing the lawn and launderettes and stuff, do you think that helps? Because you said about building a relationship. Do you think that helps to get them to take the medication? […]

Claire: With Jim I think, you know, “You’re going to do this; you’re going to do that for me”. “Yeah I am going to take my medication”. He’s said that to me before (Nurse, FG1).

Linda: I think he’s sort of playing ball because we’re doing some things for him (Nurse, FG1).

Claire: If we don’t, I don’t think he would. He wouldn’t come to the clinic (Nurse, FG1).

Liz, who believed one of her patients would both enjoy and benefit therapeutically from a local gardening project, said she had given him a plant when he was still in hospital with the aim of nudging him towards using this service:

So I took [the plant] to him and said, “This is from [the gardening project], come and have a look”. And he later on came and thanked me for it ‘cause he was obviously quite touched by that. And a few weeks later he was down at the project digging and gardening. And he did that for quite a few months until he decided he’d had enough of it. But that was, I suppose, a slightly creative way of getting him to do what I wanted him to do (Liz, social worker, FG2).

Negotiating Agreements

Negotiations with patients to find mutually acceptable solutions were common. Participants reported reaching compromises with patients about medication:

There was a female patient, Mary, who refused to have – she was on leave [from hospital] – refused to have her depot [injection]. Came to see me, I had a bit of a chat with her and I said, “Oh why don’t you have it every three weeks then?” [i.e., less frequently] And she said, “Oh great, yes that’s fine” and off she went and had it (Dan, psychiatrist, FG 4).

Courses of action regarding wider well-being issues were also negotiated:

He won’t let me in and he can’t move because of books. He can’t cook and so he eats out and he’s over 20 stone and his health is suffering. And so rather than hit him head on and get into the house – which I know I won’t do – I’ve got him to fill the bin liners and leave them out without seeing me and I collect them. As a result, he has cleared a little bit of his draining board and he is now eating fresh food (Alice, occupational therapist, FG6).

The descriptions of negotiations often focused on striking “deals” or agreeing “contracts”, again alluding to a relationship’s reciprocal dimensions. Negotiation also occurred when participants and patients held radically different views about their respective rights and responsibilities. For example, some patients were portrayed as holding unrealistic expectations, thinking professionals possessed a “magic wand” with which they could solve “any” problem. Extensive assistance with practical issues were in some cases perceived to undermine efforts to increase patients’ independence:

I think we do too much ‘doing’ for people […] Because we’re so concerned with engaging them that we are doing all these things for the person, and then quite often we need to then take a back step. And we’re trying to help people; we want to help people to do things for themselves (Linda, nurse, FG1).

If patients were unwilling to take on responsibilities that they might be capable of, participants sometimes tried to re-negotiate the relationship, which, at times, could be frustrating:

I find the most frustrating ones the ones that do want you to be their mother. And trying to get them to accept the fact that you’re not going to do that and that they do have to take responsibility for themselves. And that you’ll be there to help with bits (Lucy, nurse, FG4).

Although participants emphasized an ambition to let patients’ views influence agreements, balancing a patient-centered approach with their responsibility for patient safety could occasionally limit the room for negotiation:

It’s kind of compromise isn’t it? Anne would perhaps prefer not to take any medication at all but in terms of the deals we might strike with her they’re a bit stacked on our side ‘cause we’ve got the Mental Health Act, but within that then there’s some compromise offered. […] So it’s not all, “No, you will do exactly what I say”. That, as far as you can, you give back but not to the extent that you make somebody ill again. So that would be the balance but that’s the kind of balance you’re trying to get in the deal (Lucy, nurse, FG4).

As this quote suggests, participants perceived that their power to compel impacted on negotiations. This power was seen as creating an underlying coercive dimension that took effect when, for example, professionals presented predictions to patients about what could happen if they failed to follow up on conditions for hospital leave:

Well, if you put somebody out on leave when they’re sectioned [detained] in the hospital the deal is, “You come here and have your treatment and you can see us as often or as little as you want to. You can do what you like in between times but that is the deal. If you don’t come, the other side of the deal [is] then I’m forced to put you back in hospital where, presumably, you don’t want to go” (Dan, psychiatrist, FG4).

Asserting Authority

Building trusting relationships that facilitated negotiation of mutual agreements was presented by participants as the ideal way to achieve therapeutic aims. Nevertheless, where encouragement and education failed, “deals” were broken, or participants believed patients were unable to act in their own best interests, more authoritative approaches were sometimes deemed necessary:

It’s building up the rapport and trust, you know. And he’s had that with us and he now knows that we will listen. And also to set boundaries. […] And so we’ve had to be firm with him and set guidelines about what he can do and can’t do (Emma, nurse, FG6).

If they were worried that a patient might be relapsing, participants described using more assertive methods for ensuring that medication was taken, such as counting pills, using depot injections or observing consumption:

A great deal of the work of this team, I think, is chasing people up. Sometimes we make daily visits and sometimes we can visit people twice a day to actually ensure that they, we observe them and they take their medication (Linda, nurse, FG1).

The ultimate assertion of authority was the application of the Mental Health Act. Although participants saw the appropriate use of the Act as part of their duty of care, it was portrayed as an inferior tool to what could be achieved by other means:

AS: Is there any one thing of what you want patients to do that you would consider to be top of the list?

Lucy: I suppose it would be engage wouldn’t it? Because we can’t do any of the other things without it (Nurse, FG4).

Ajmal: Engagement (Psychiatrist, FG4).

Rob: Engagement (Community support worker, FG4).

Sue: Yes (Nurse, FG4).

Lucy: Or all we’re left with is the Mental Health Act, isn’t it, if we haven’t engaged them? (Nurse, FG4)

Moreover, applying the Act was considered to have the potential to undermine relationships:

I think the next time I hear that things are bad I might insist [under the MHA] to be let in. But it’s a pretty heavy handed way of dealing with things, when they are a family who are in family therapy and you’re trying to work together. It’s pretty sort of [a] sledgehammer approach (Amy, social worker, FG2).

Previous experience of legal coercion was described as alerting some patients to “early signs” that an involuntary admission to hospital was being considered:

For example, someone’s starting to relapse and – [or] we think they are – and we may decide to do joint visits. Some of the patients are so experienced they say, “Oh you’re doing joint visits. You must think I’m relapsing” (John, community support worker, FG4).

Participants experienced a need to address perceptions of coercive services:

So people often have the idea, “If I stop taking my medication, you’ll put me in hospital”. Well, we wouldn’t automatically do that. Other than about two people I can think of off the top of my head […] we try to get through to people, “No, it’s about working with us” (Lucy, nurse, FG4).

The authority of the professional role (including the use of the Mental Health Act) therefore simultaneously represented a useful tool to ensure patient safety during relapse but also a threat to relationships.

Discussion

Our participants stated that they wanted patients to adhere to treatment and to look after their social, physical and mental well-being. To facilitate this, participants attempted to build good, trusting relationships which were perceived as a prerequisite to establishing reciprocal agreements and, through that, patient-centred care. This resonates with patients’ descriptions of pressure from service providers to ‘stay well’ as well as to adhere to treatment (Canvin et al. 2013). ‘Asserting authority’ was presented by participants as a necessary tool, albeit one with potential to threaten relationships.

By emphasizing the need for trust and “deals”, participants evoked ideals of relationships containing a degree of reciprocity and equality. This was somewhat at odds with their presentation of the authoritative aspects of the professional role where it was understood that they had a unique overview over what constituted patients’ best interests and occasionally an obligation to act against patients’ wishes. This represents two overarching—and potentially conflicting—processes by which participants sought to influence patients: one based on engagement facilitated by reciprocal relationships and one based on their professional authority. We discuss each in turn.

Relationships and the Obligation to Reciprocate

The giving of gifts (material or symbolic) creates obligations in recipients to accept and reciprocate and such universal reciprocal mechanisms are thought to constitute the foundation of social relationships, feelings of community and trust (Mauss 1990 [1922]; Malinowski 1978 [1922]; Simmel 1950 [1908]). Øye (2010) suggests that creating bonds and alliances with patients always has been a central feature of psychiatry and applies this notion of reciprocity to an analysis of interactions on an in-patient ward. She describes how ward staff sometimes provide services or favours that extend beyond their professional duties, such as giving patients cigarettes or staying on after their shift to provide support. These ‘gifts’ create expectations, she argues, among staff and patients alike, that patients will participate in the therapeutic activities offered. Many of the influencing behaviors identified in the literature (Box 1) rely on similar reciprocal expectations. These were also reflected in our data, such as in the example of Liz and the gardening project.

Forming relationships that create reciprocal obligations in patients who are reluctant to take treatment might, on the face of it, appear manipulative. If, however, reciprocal obligations are inherent in all social relationships, this might simply tell us that the relationships between mental health professionals and patients rely on the same social mechanisms as most others. The context of deinstitutionalized services means that traditional boundaries between professional relationships and friendships become blurred (e.g., when giving practical assistance in the home; Angell and Mahoney 2007). The deinstitutionalized nature of the services provided by our participants thus arguably provide wider scope for initiating reciprocal obligations than the hospital setting because interactions occur across a broader range of arenas in patients’ lives, including those which are private, domestic, social and familial.

Reciprocity in an Authority Context

While our participants emphasized their efforts to negotiate “fair” solutions, the reciprocal dimension of relationships between professionals and patients with severe mental illness differ from many other social relationships in regard to at least two inherent power dimensions. First, one party is employed to create a professional (i.e. not personal) relationship with the other (whether or not the other wants this) which, as shown, extends into the private sphere of the other’s life. Second, one party holds legal authority to compel the other if needed. Sjöström (2005) describes how the latter power differential forms part of the context surrounding the relationships. In an analysis of interactions in a psychiatric ward he shows how clinicians might evoke (consciously or not) a ‘coercion context’ on the basis of patients’ previous experiences. For example, a patient who has been under compulsion a number of times might interpret a statement of how he or she “must” or “ought to” do something differently from patients without this experience, even at times when treatment is voluntary (i.e. not legally mandated). In community care, simple predictions of how compulsion might become necessary might similarly evoke perceptions of a coercive environment (Canvin et al. 2013). As our data indicate, participants perceived that these power dimensions in some cases permeated their interactions with patients. Their professional authority was acknowledged as giving participants an “advantage” over patients in negotiations, and stood in contrast to their expressions of an ideal, more balanced, professional-patient relationship. According to participants, the awareness of the possibility of compulsion could therefore be enough to undermine trust, and subsequently threaten patient-centered care and recovery. This has also been reported by patients receiving community care (Laugharne et al. 2012). Perceptions of services as coercive might be a barrier to people seeking care, as suggested by recent studies of Community Treatment Orders (legal regimes that oblige patients to accept treatment to stay out of hospital; Van Dorn et al. 2006; Swartz et al. 2003). Our analysis has shown that the ‘coercion context’ in addition to the effect on patient experiences as reported by others forms part of how professionals conceptualize their role, and produces potential conflicts between the inherent ‘care’ and ‘control’ aspects of that role.

Limitations

Very little has been published on English community mental health professionals’ perceptions of their behaviors to influence reluctant patients and as such this study was explorative in nature. The study is based on a relatively small sample and limited to one NHS Trust, so it is possible that professionals from other areas have different experiences. The influencing behaviors reported here are, however, similar to those identified elsewhere (Box 1). A strength of the study is the multi-disciplinary nature of the sample (Table 1) which facilitated analysis of team-based service delivery, in line with current practice. Although individual participants’ professions meant their practical interactions with patients differed, we found no systematic differences between professional groups as to how they conceptualized the relationships with patients. Given our design, however, we cannot conclude these do not exist, and because varying levels of authority are vested in different professions we recommend that this is a focus for future studies. Furthermore, data collection was undertaken when Community Treatment Orders had only just been introduced in England and Wales, which might account for why the use of these orders was largely absent from the data. Whether this legislation has changed professionals’ conceptualization of their roles and interactions remains to be investigated. Finally, because our aim was to explore professionals’ conceptualizations of their practice, we did not collect corroborating data to test whether the influencing behaviors did, in fact, lead to increased adherence or wellbeing.

Conclusion

Current mental health policy is focused on community care and encourages patient-centred approaches (Department of Health 2011) and relationships are envisaged as mechanisms for mental health service delivery (Anthony 1993; Department of Health 2009). To the extent that mental health professionals today more than previously are involved in the private spheres of patients’ lives, deinstitutionalization might be viewed not only as changing the locus of care but, arguably, also the relationships and interactions between mental health professionals and patients (Davies 2002; Szmukler and Appelbaum 2008). We have highlighted some aspects of how community mental health professionals conceptualize these interactions, which in turn help us gain a better understanding of their practice. The accounts of the professionals in this study express commitment to patient-centered approaches to achieving treatment adherence and wellbeing. They suggest that this approach ideally should manifest itself in trusting, reciprocal relationships that allow “deals” and agreed courses of action to be negotiated. In practice, however, they might need to assert their professional authority in these interactions when patients refuse services. As a consequence, interactions occur in a context that might evoke perceptions of coercion that affect, and sometimes threaten, the very relationship considered a prerequisite for patient-centered care.

This dual focus on patient-centered approaches and professional authority is accepted as a core part of mental health service delivery. By providing descriptive accounts of micro-level dynamics of clinical encounters, our analysis has shown how the authoritative aspect of the professional role has potential to undermine therapeutic interactions with reluctant patients. Such micro-level analyses, we argue, are needed in order to enhance our understanding of how patient-centered mental health policy may be implemented through clinical practice.

Notes

For simplicity, we use ‘mental health professionals’ in this article to refer to all those working thereputically with patients in community teams whether or not they are clinicians or have received specific professional training. Where relevant, we refer to specific professions.

References

Anderson, E., Levine, M., Sharma, A., Ferretti, L., Steinberg, K., & Wallach, L. (1993). Coercive use of mandatory reporting in therapeutic relationships. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 11, 335–345. doi:10.1002/bsl.2370110310.

Angell, B. (2006). Measuring strategies used by mental health providers to encourage medication adherence. Journal of Behaviour Health Services and Research, 33(1), 53–72. doi:10.1007/s11414-005-9000-4.

Angell, B., & Mahoney, C. (2007). Reconceptualizing the case management relationship in intensive treatment: A study of staff perceptions and experiences. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 34(2), 172–188. doi:10.1007/s10488-006-0094-7.

Angell, B., Mahoney, C. A., & Martinez, N. I. (2006). Promoting treatment adherence in assertive outreach treatment. Social Service Review, 80(3), 486–526. doi:10.1086/505447.

Anthony, W. A. (1993). Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 16(4), 11–23.

Appelbaum, P., & Le Melle, S. (2007). Techniques used by assertive community treatment (ACT) teams to encourage adherence: Patient and staff perspectives. Community Mental Health Journal, 44, 49–464. doi:10.1007/s10598-008-9149-4.

Appelbaum, P. S., & Redlich, A. (2006). Use of leverage over patients’ money to promote adherence to psychiatric treatment. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 194(4), 294–302. doi:10.1097/01.nmd.0000207368.14133.0c.

Atlas.ti. (1999). ATLAS.ti 6.2. Berlin: Scientific Software Development.

Burns, T. (2004). Community mental health teams. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Burns, T., & Firn, M. (2002). Assertive outreach in mental health: A manual for practitioners. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Burns, T., Yeeles, K., Molodynski, A., Nightingale, H., Vazquez-Montes, M., Sheehan, K., et al. (2011). Pressure to adhere to treatment (‘leverage’) in English mental healthcare. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199, 145–150. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.110.086827.

Canvin, C., Rugkåsa, J., Sinclair, J., & Burns, T. (2013). Leverage and other informal pressures in community psychiatry in England. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 36, 100–106. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2013.01.002.

Classen, D., Fakhoury, W., Ford, R., & Priebe, S. (2007). Money for medication: Financial incentives to improve medication adherence in assertive outreach. Psychiatric Bulletin, 31, 4–7. doi:10.1192/pb.31.1.4.

Curtis, L., & Hodge, M. (1995). Ethics and boundaries in community support services: New challenges. New Directions for Mental Health Services, 66, 43–59.

Davies, S. (2002). Autonomy versus coercion: Reconciling competing perspectives in community mental health. Community Mental Health Journal, 38(3), 239–250.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (1993). Handbook of qualitative research. Thousands Oaks: Sage.

Department of Health. (2009). New horizons: A shared vision for mental health. London: Department of Health.

Department of Health. (2011). No health without mental health: A cross-government mental health outcomes strategy for people of all ages. London: Department of Health.

Elbogen, E. B., Swanson, J. W., & Swartz, M. S. (2003). Psychiatric disability, the use of financial leverage and perceived coercion in mental health services. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 2(2), 119–127. doi:10.1080/14999013.2003.10471183.

Gardener, W., & Lidz, C. (2001). Gratitude and coercion between physicians and patients. Psychiatric Annuals, 31(2), 125–129.

Gillard, S., Simons, L., Lucock, M., & Edwards, C. (2012). Patient and public involvement in the coproduction of knowledge: Reflection on the analysis of qualitative data in a mental health study. Qualitative Health Research, 22(8), 1126–1137. doi:10.1177/1049732312448541.

Glaser, B. G. (1965). The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems, 12(4), 436–445. doi:10.2307/798843.

Gray, R., Wykes, T., & Gournay, K. (2002). From compliance to concordance: A review of the literature on interventions to enhance compliance with antipsychotic medication. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 9, 277–284. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2850.2002.00474.x.

Jaeger, M., & Rossler, W. (2010). Enhancement of outpatient treatment adherence: Patient’s perception of coercion, fairness and effectiveness. Psychiatry Research, 180, 48–53. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2009.09.011.

Kirsh, B., & Tate, E. (2006). Developing a comprehensive understanding of the working alliance in community mental health. Qualitative Health Research, 16(8), 1054–1074. doi:10.1177/1049732306292100.

Kitzinger, J. (2005). Focus group research: Using group dynamics to explore perceptions, experiences and understandings. In I. Holloway (Ed.), Qualitative research in health care (pp. 56–69). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Korman, H., Engster, D., & Milstein, B. M. (1996). Housing as a tool of coercion. In D. L. Dennis & J. Monahan (Eds.), Coercion and aggressive community treatment: A new frontier in mental health law (pp. 95–113). New York: Plenum.

Laugharne, R., Priebe, S., McCabe, R., Garland, N., & Clifford, D. (2012). Trust, choice and power in mental health care: Experiences of patients with psychosis. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 58(5), 496–504. doi:10.1177/0020764011408658.

Lingam, R., & Scott, J. (2002). Treatment and non-adherence in affective disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 105, 164–172. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.1r084.x.

Lopez, M. (1996). The perils of outreach work: Overreaching the limits of persuasive tactics. In D. L. Dennis & J. Monahan (Eds.), Coercion and aggressive community treatment: A new frontier in mental health law (pp. 85–92). New York: Plenum.

Lützén, K. (1998). Subtle coercion in psychiatric practice. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 5, 101–107. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2850.1998.00104.x.

Magnusson, A., & Severinsson, E. (2004). Swedish mental health nurses’ responsibility in supervised community care of persons with long-term mental illness. Nursing and Health Sciences, 6, 19–27. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2003.00171.x.

Malinowski, B. (1978 [1922]). Argonauts of the Western Pacific. London: Routledge.

Mauss, M. (1990[1922]). The gift: Forms and functions of exchange in archaic societies. London: Routledge.

Mind. (2008). Life and times of a supermodel. The recovery paradigm for mental health. London: Mind.

Monahan, J., Redlich, A. D., Swanson, J., Robbins, P. C., Appelbaum, P. S., Petrila, J., et al. (2005). Use of leverage to improve adherence to psychiatric treatment in the community. Psychiatric Services, 56(1), 37–44. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.56.1.37.

Moser, L. (2007). Coercion in assertive community treatment: Examining client, staff, and program predictors. PhD Thesis. Purdue University, Indiana. http://search.proquest.com/docview/304834899?accountid=31375. Accessed October 3, 2012.

Moser, L., & Bond, G. (2009). Scope of agency control: Assertive community treatment teams’ supervision of consumers. Psychiatric Services, 60(7), 922–928.

Nath, S. B., Alexander, L. B., & Solomon, P. L. (2012). Case managers’ perspectives on the therapeutic alliance: A qualitative study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology,. doi:10.1007/s00127-012-0483-z.

Neale, M., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2000). Therapeutic limit setting in an assertive outreach treatment programme. Psychiatric Services, 51(4), 499–505.

Nicholson, J. (2005). Use of child custody as leverage to improve treatment adherence. Psychiatric Services, 56, 357–358. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.56.3.357-a.

Olofson, B., & Norberg, A. (2001). Experiences of coercion in psychiatric care as narrated by patients, nurses and physicians. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 33(1), 89–97. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01641.x.

Olofsson, B., Norberg, A., & Jacobsson, L. (1995). Nurses’ experience of using force in institutional care of psychiatric patients. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 49, 325–330.

Øye, C. (2010). Omsorgens vilkår: Om gaver og tjenester som del av relasjonsdannelsen in institusjonspsykiatrien når brukermedvirkning skal vektlegges (The conditions of care: On the use of gifts and services as part of relationship building in inpatient psychiatry when user involvement is emphasised). Michael, 2, 218–233.

Redlich, A. D., Steadman, H. J., Robbins, P. C., & Swanson, J. (2006). Use of the criminal justice system to leverage mental health treatment: Effects of treatment adherence and satisfaction. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry Law, 34, 292–299.

Robbins, P., Petrila, J., Le Melle, S., & Monahan, J. (2006). The use of housing as leverage to increase adherence to psychiatric treatment in the community. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 33(2), 226–236. doi:10.1007/s10488-006-0037-3.

Rugkåsa, J., & Burns, T. (2009). Community treatment orders. Psychiatry, 8(2), 493–495. doi:10.1016/j.mppsy.2009.09.009.

Seale, C., Chaplin, R., Lelleiott, P., & Quirk, A. (2005). Sharing decisions in consultations involving anti-psychotic medication: A qualitative study of psychiatrist’ experiences. Social Science and Medicine, 62(11), 2861–2873. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.002.

Shepherd, G., Boardman, J., & Slade, M. (2009). Making recovery a reality. Briefing Paper. London: Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health.

Simmel, G. (1950 [1908]). In K. H. Wolff (Transl. and Ed.), The Sociology of Georg Simmel. New York: The Free Press.

Sjöström, S. (2005). Invocation of coercion in compliance communication—Power dynamics in psychiatric care. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 29, 36–47. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2005.06.001.

Sjöström, S., Zetterberg, L., & Markström, U. (2011). Why community compulsion became the solution—Reforming mental health law in Sweden. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 34(6), 419–428. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2011.10.007.

Smart, C. (2007). Personal life. New directions in sociological thinking. London: Polity Press.

Solomon, P. (1996). Research on the coercion of persons with severe mental illness. In D. L. Dennis & J. Monahan (Eds.), Coercion and aggressive community treatment: A new frontier in mental health law (pp. 129–145). New York: Plenum.

Stanhope, V., Marcus, S., & Solomon, P. (2009). The impact of coercion on service from the perspective of mental health care consumers with co-occurring disorders. Psychiatric Services, 60(2), 183–188.

Stanhope, V., & Matejkowski, J. (2010). Understanding the role of individual consumer–provider relationships within assertive community treatment. Community Mental Health Journal, 46, 309–318. doi:10.1007/s10597-099-9219-2.

Steadman, H. J., Gounis, K., Dennis, D., Hopper, K., Roche, B., Swartz, M., et al. (2001). Assessing the New York involuntary outpatient commitment pilot programme. Psychiatric Services, 52, 330–336. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.52.3.330.

Susser, E., & Roche, B. (1996). “Coercion” and leverage in clinical outreach. In D. L. Dennis & J. Monahan (Eds.), Coercion and aggressive community treatment: A new frontier in mental health law (pp. 73–84). New York: Plenum.

Swartz, M. S., & Swanson, J. (2008). Outpatient commitment: When it improves patient outcomes. Current Psychology, 7(4), 25–35.

Swartz, M. S., Swanson, J. W., & Hannon, M. J. (2003). Does fear of coercion keep people away from mental health treatment? Evidence from a survey of persons with schizophrenia and mental health professionals. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 21, 459–472. doi:10.1002/bsl.539.

Swartz, M. S., Swanson, J. W., Wagner, H. R., Burns, B. J., Hiday, V. A., & Borum, R. (1999). Can involuntary outpatient commitment reduce hospital recidivism? Findings from a randomized trial with severely mentally ill individuals. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156, 1968–1975.

Swartz, M. S., Wagner, H. J., Swanson, J. W., Hiday, V. A., & Burns, B. J. (2002). The perceived coerciveness of involuntary outpatient commitment: Findings from an experimental study. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry Law, 30, 207–217.

Szmukler, G., & Appelbaum, P. (2008). Treatment pressures, leverage, coercion, and compulsion in mental health care. Journal of Mental Health, 17(3), 233–244. doi:10.1080/09638230802052203.

Van Dorn, R. A., Elbogen, E. B., Redlich, A. D., Swanson, J. W., Swartz, M. S., & Mustillo, S. (2006). The relationship between mandated community treatment and perceived barriers to care in persons with severe mental illness. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 29(6), 495–506. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2006.08.002.

Zygmunt, A., Olofson, M., Boyer, C. A., & Mechanic, D. (2002). Interventions to improve medication adherence in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 1653–1664. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1653.

Acknowledgments

We thank our focus group participants for making this study possible. This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute of Health Research (Program Grant for Applied Research, Grant Number RP-PG-0606-1006). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rugkåsa, J., Canvin, K., Sinclair, J. et al. Trust, Deals and Authority: Community Mental Health Professionals’ Experiences of Influencing Reluctant Patients. Community Ment Health J 50, 886–895 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-014-9720-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-014-9720-0