Abstract

To evaluate discriminant validity, reliability, internal consistency, and dimensional structure of the World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) in a heterogeneous Iranian population. A clustered randomized sample of 2,956 healthy with 2,936 unhealthy rural and urban inhabitants aged 30 and above from two dissimilar Iranian provinces during 2006 completed the Persian version of the WHOQOL-BREF. We performed descriptive and analytical analysis including t-student, correlation matrix, Cronbach’s Alpha, and factor analysis with principal components method and Varimax rotation with SPSS.15. The mean age of the participants was 42.2 ± 12.1 years and the mean years of education was 9.3 ± 3.8. The Iranian version of the WHOQOL-BREF domain scores demonstrated good internal consistency, criterion validity, and discriminant validity. The physical health domain contributed most in overall quality of life, while the environment domain made the least contribution. Factor analysis provided evidence for construct validity for four-factor model of the instrument. The scores of all domains discriminated between healthy persons and the patients. The WHOQOL-BREF has adequate psychometric properties and is, therefore, an adequate measure for assessing quality of life at the domain level in an adult Iranian population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Quality of life incorporates humanistic elements of health and well being and is one of the criteria in the evaluation of health care delivery system, assessment of treatment and evaluation of cost-effectiveness (WHOQOL Group 1993). Instruments on quality of life and functioning instruments abound in health care literature, ranging from simple to complex. Researchers have invariably incorporated an array of subjective and objective indices which measure impact of disease and impairment on daily activities and behavior, perceived health measures and disability/functioning-status (Bergner et al. 1981; Hunt et al. 1989; Ware et al. 1993). A short version of the World Health Organization Quality-100 called WHOQOL-BREF with 26 items and four domains of health, namely, physical, psychological, social relationships, and environmental is considered an equally valid and reliable alternative to the assessment of domain profiles used in the WHOQOL-100 (WHOQOL Group 1998a, b). Its promising results are reported in several epidemiological and clinical trials (Kalfoss et al. 2008; Angermeyer et al. 2002; Barros da Silva Lima et al. 2005; O’Caroll et al. 2000; Hsiung et al. 2005; Jang et al. 2004; Leplege et al. 2000; Tazaki et al. 1998).

Validation of the WHOQOL-BREF in terms of reliability, internal consistency, construct validity, criterion validity, and discriminant validity has attracted the attention of the health researchers. But, the research has yielded different results. Some studies are limited to normal population (Min et al. 2002) while some have aimed at comparing small groups, without making any effort to ensure that items of the WHOQOL-BREF really represent the same constructs across groups (Fang et al. 2002; Noerholam et al. 2004). Some scholars have tried to confirm whether their observed data represent the original structure prescribed by the WHOQOL-Group, using rigorous and tedious statistical methods including confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) (Trompenaars et al. 2005; Berlim et al. 2005; Lima et al. 2005; Yao and Wu 2005; Izutsu et al. 2005; Nedjat et al. 2008). Others have relied simply on descriptive statistics and reliability Cronbach Alpha, without ruling out the possibility of factor invariance (Leung et al. 2005; Chien et al. 2007; Yao et al. 2008). Most of the studies were conducted in countries with different cultures and languages (Yao and Wu 2005; Leung et al. 2005; Chien et al. 2007; Yao et al. 2008). A single evidence in Iran by Nedjat et al. (2008) produced acceptable reliability (0.55–0.84) and discriminant validity for the interview version of the WHOQOL-BREF. This instrument also demonstrated statistically significant correlation with the Iranian version of the SF-36. However, their sample was limited to urban population in Tehran, Iran; also, they did not apply factor analysis (Nedjat et al. 2008).

As a developing nation, Iran is committed to the citizens’ well being as well as to the improvement of quality of life. In this respect the WHOQOL-BREF, a short version of the WHOQOL-100, is developed for cross cultural comparisons of quality of life, encompassing four domains of life profiles. In view of the prevailing gap, this study was designed to examine the psychometric properties of the WHOQOL-BREF in terms of reliability and validity, factor structure, and factor loading, using heterogeneous data from healthy and unhealthy urban and rural regions of three districts in the central part of Iran, namely, Isfahan, Najaf-Abad, and Arak (Sarrafzadegan et al. 2003, 2006). The rationale for selection of the sample was basically our interest in examining the applicability of this instrument, despite the variations in the citizens’ socio-economic status and the instrument’s usefulness to health and social services. This is a preliminary effort to avail ourselves of the advantages of a measure of quality of life, which is easy, comprehensive and valid, such as the WHOQOL-BREF, and which can be used in future epidemiological and outcome studies.

Methods

Participants

During 2006 a clustered randomized sample of 5,892 rural and urban inhabitants from Isfahan, Najaf-Abad, and Arak participated in ‘Isfahan Healthy Heart Programme’(IHHP), a comprehensive community-based intervention trial for cardiovascular disease prevention and control (Sarrafzadegan et al. 2003, 2006). Inclusion criteria were: adults ≥19 years of age who were supposedly in the peak of their productive age, residing in urban or rural regions from either type of districts, with no such illness as could lead to death during the following 6 months or significant cognitive impairment. For this study we included adults who aged ≥30 years. Exclusion criteria were: inability to undergo various verbal and written parts of the investigation protocol (interview and questionnaires) due to mental retardation, mental illness, or refusal to participate. As per their health status, we divided the total sample into subsamples of unhealthy (clinical) and healthy (non-clinical) groups. The non-clinical group had no specific physical and mental illness while the clinical group reported chronic conditions such as musculoskeletal (51.1%), cardiovascular diseases (22.1%), endocrinological diseases such as diabetes mellitus and thyroid dysfunction (11.4%), and other medical conditions such as infertility, visual impairment, asthma, anemia, and migraine (15.4%). Incomplete questionnaires and those who did not fulfill the research criteria were excluded from the study sample. Here we report the final analysis based on the 5,892 completed questionnaires including: 2,936 patients (clinical group) and 2,956 healthy people (non-clinical group). The respondents’ consent was sought prior to their inclusion in the study.

Instrument

The WHOQOL-BREF is available in more than 40 languages including Persian. In this study we sought the approval of the WHOQOL Group and used a Persian version of the instrument. Four independent translators, who were bilingual in Persian and English, and who were not aware of the background of the questionnaire, translated the questionnaire back to English. The bilingual panel resolved the discrepancies as and when differences erupted. After a couple of debates and discussions, a provisional Persian version of the questionnaire was ready to be tested for feasibility, clarity, and response categories (WHOQOL Group 1993, 1998a, b). As it was a self-reporting questionnaire, the study participants could answer the questions on their own. However, trained investigators assisted the respondents by reading out the questions to the respondents, whenever needed. The frame of reference for each item was 1 month prior to the investigation. The instrument consists of 26 broad and comprehensive questions: the first two items which are contained in the WHOQOL-100 measure the Overall Quality of Life (OQOL) and Overall Health Status (OHS), respectively. The remaining 24 items encompass four dimensions of health including physical, psychological, social and environmental, each one with their respective items. Seven indicators such as pain, dependence on medical aids, energy, mobility, sleep and rest, activities of daily living, and work capacity measure physical health domain. Psychological health is measured with 6 items including positive feeling, personal belief, concentration, bodily image, self-esteem, and negative feeling. Social relationship, with 3 items, focuses on personal relationships, social support, and sexual life. Environmental health with 8 items deals with issues related to security, physical environment, financial support, accessibility of information, leisure activity, home environment, health, and transportation. All scores are transformed to reflect 4–20 for each domain with higher scores corresponding to a better QOL. There is no overall score for the WHOQOL-BREF and each domain is calculated by summation of their specific items. Where an item is missing, the mean of other items in the domain was inserted. Where more than two items are missing from the domain, the domain score was not calculated, except for domain 3, in which more than one missing item is required to discard the calculation. Individual’s perception of quality of life is measured by summing the total scores for each particular domain. All domain scores are scaled in a positive direction (higher score indicated higher QOL). Scoring is done using the table given for converting raw scores to transformed scores. The questionnaire was well received by the participants, who took on an average 30 min to complete it.

Statistical Analysis

We used Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 15.1 (SPSS) to calculate basic descriptive statistics such as percentage distribution, range, mean, standard deviation of the respondents’ demographic features, scores for 26 items, and four domains of the WHOQOL-BREF. We ran the Student’s t test for independent samples to compare the quality of life status of the two subgroups for all domains, overall quality of life (OQOL), and overall health status (OHS). As a measure of internal consistency we calculated the Cronbach’s Alpha from the correlation coefficient values yielded for each domain and 26 items of the WHOQOL-BREF. For the purpose of analysis Cronbach’s Alpha equal to or greater than 0.70 were considered satisfactory. Intra-class correlation (ICC) was carried out to establish of the WHOQOL-BREF reliability. Basically ICC is an estimate of the fraction of the total measurement variability due to variation among individuals and we expected that the ICC for each WHOQOL-BREF domain, the OQOL and OHS to exceed 0.70 (Bonomi et al. 2000a, b; Anastasia 1990). The same investigator carried out the test and retest interviews. Finally, factor analysis was carried out, using the principal components method with Varimax rotation, to examine the dimensional structure of the questionnaire (Joreskog 1971; Vandenberg and Lance 2000). A hypothesis matrix of 1s and 0s was formed: 1 indicated that an item was hypothesized to load on a dimension and 0 indicated a non-hypothesized relationship.

Findings

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

The total sample study was 5,892: 2,936 clinical and 2,956 non clinical subjects. There was no significant difference between the clinical and non clinical groups in terms of age [mean (SD): 42.1 ± 12.1 and 41.3 ± 13.6; χ2 = 3.48; df = 3; P = 0.32], education [mean (SD): 9.2 ± 3.2 and 9.4 ± 3.9; χ2 = 4.99; df = 4; P = 0.29], sex (χ2 = 1.24; df = 1; P = 0.14), and occupational status (χ2 = 1.14; df = 1; P = 0.14), respectively. However, significant differences were noted between two groups in terms of marital status (χ2 = 208.14; df = 2; P = 0.00) (Table 1).

Means of Scales

Table 2 shows the mean scores for the four health domains, the means of overall quality of life (OQOL), and overall health status (OHS) were higher in the health (non clinical) sample as compared with the unhealthy (clinical) one. Both groups showed highest mean score for environmental followed by psychological domains. Lowest mean scores were noted for physical domain of clinical group and social relationships of the non clinical group. These differences were statistically significant.

Distinctiveness of Subscales

As a measure for the internal consistency and confirming the fact that all the items of the WHOQOL-BREF contribute to measuring areas related to quality of life, we calculated the Cronbach’s alpha for four health domains. As Table 3 reveals, for the total sample, the internal consistency of the domains was satisfactory to good, yielding Cronbach’s Alpha ranging from 0.78 for psychological health to 0.82 for social relationships. The Cronbach’s alpha for the entire sample, the clinical, and the non-clinical were 0.82, 0.82, and 0.84, respectively.

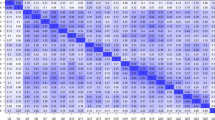

Table 4 shows the bivariate inter-correlation coefficients (ICCs) of the four domains with OQOL and OHS, for the entire sample and its subgroups. The data analysis showed satisfactory correlation at <0.01 level for all domains. This observation confirms our theory that these four domains are highly relevant to the OQOL and OHS.

As presented in Table 5, 100% (24) of the WHOQOL-BREF questions showed maximum correlation with their original domains in the expected direction. Statistically the Pearson correlation values for all items were highly significant (P < 0.01). The ICCs for the four health domains of the WHOQOL-BREF were within the range of acceptable values (physical health = 0.78; psychological health = 0.79; social relationships = 0.74). The ICC for OQOL was 0.70.

Dimensional Structure

A principal axis factor analysis was conducted on the bivariate correlations among the 24 variables. Four factors were initially extracted with Eigen values equal to or greater than 1.00. An examination of the factors leads to the justification of all 7 items of physical health, 5 items of psychological health, all items of social relationships, and 5 items of environmental health. Orthogonal rotation of the factors produced a desirable factor structure. As Table 6 shows, the percentage of explained variance of the first four factors was 50.4. The first factor (physical health) with 7 question accounted for 31.1% of the variance and is defined by items on pain, dependence on medical aids, energy, mobility, sleep and rest, activities of daily living, and work capacity. The second factor (psychological health) with 5 question explained 7.9% of the variance, including positive feeling, concentration, bodily image, self-esteem, and negative feeling. Personal belief which originally belonged to psychological domain was shifted to social relationships. The third factor (social relationships) with its 3 original questions (i.e., personal relationships, sexual activity, and social support), one question from the psychological domain (i.e., personal belief) and 3 questions for the environmental health (i.e., health services, physical environment, and transportation) explained 5.9% of variance. The fourth factor (environmental health) was left with 3 questions (i.e., financial support, accessibility of information, and leisure activity) and explained 5.5% of the variance in quality of life.

Discussion

Hypothetically, we expected a better quality of life for our non-clinical (healthy) sample. The analysis of data proved that the healthy group enjoyed a better quality of life as compared with their unhealthy counterparts who complained of chronic physical conditions like musculoskeletal, cardiovascular diseases, endocrinological diseases, and other medical conditions such as infertility, visual impairment, asthma, anemia, and migraine. Significant differences between the clinical and the non clinical samples viz-a-viz four domains as well OQOL and OHS were evident (Table 2). This observation is an indication of the distinctiveness of the WHOQOL-BREF in demarcating healthy and unhealthy individuals from each other. Nedjat et al. (2008) relied on means of all dimensions for the total sample and did not consider the subsamples.

This study reported Cronbach’s Alpha of minimum 0.76 and maximum of 0.82 for four domains of the WHOQOL-BREF which are satisfactory (Table 3). Intra-class correlation (ICC) for each WHOQOL-BREF domain, the OQOL and OHS exceed 0.7. Moreover, item-scale correlation matrix for the WHOQOL-BREF measures showed that all 7 items of the physical, 6 items of the psychological, 3 items of the social relationships, and 8 items of the environmental domains had high significant correlation coefficients with their respective health domains. The aforementioned study in Iran (Nedjat et al. 2008) reported Cronbach Alpha of 0.55–0.61 for the social relationships which is supposed to be unsatisfactory. In this respect our observation is different from that of the previous study in Iran and some studies conducted in other communities (Noerholam et al. 2004; Izutsu et al. 2005; Leung et al. 2005; Skvington and Loftfy 2004). Nevertheless, our findings are very similar to the findings of the WHOQOL-BREF Group (1998a, b). Therefore, there is no need to reconsider the original items of the social relationships domain. Dissatisfaction with the results of social relationships in previous studies could be attributed to sampling design and homogeneity of the population under study. Cultural explanations offered by some scholars may not be valid and at least both the items on sex life and social support clearly fall into the category of social relationships domain.

The structural components of the WHOQOL-BREF were ascertained through factor analysis. We tested the assumptions of factor invariant properties in terms of factor structure form, factor loadings, and factor uniqueness variances across the clinical and non-clinical groups. Theoretically we extracted items with Eigen values equal to or greater than 1.00 and subsequently the orthogonal rotation of the factors provided a satisfactory factor structure, showing the contribution of four factors mounting to 50.4%. The contributions of the physical, psychological, social and environmental health domains were respectively 31.1, 7.9, 5.9, and 5.5%. The physical health with its maximum contribution, was represented with all its 7 original items, psychological health with 5 items, social relationships with its 3 original, and environmental health with its 5 original items. Personal belief in the context of religiosity and spiritualism were expected to be in their original place of psychological health. Moreover, items on home environment, health and social care, and accessibility and quality of transport were expected to be in their original domain of environmental health. However, factor analysis showed how these items shifted to social domain. From cultural point of view, these observations are important, and may be an indicator for social and political orientation of people towards religion. This may also mean that religious practices are not necessarily a psychological phenomena but more a social duty which appeals to people when performed in a group. Drifting of items such as home environment, health and social care, and accessibility and quality of transport from environmental health to social relationships may show that the sense of security among our people is a social issue and finds meaning in sociological rather than psychological terms. Concentration of several environmental items in the social health domain may be attributed to the lack of emphasis on environmental issues and public sense in the society. It may also indicate disparity in distribution of social and health services and the governing rules which determine accessibility and availability of health and transportation services for the community at large.

Our observations add to the body of evidence that the WHOQOL-BREF has good reliability, internal consistency, construct validity, criterion validity, discriminant validity in healthy and unhealthy Iranian population. In this respect they are in line with several studies on quality of life of life of people with rheumatoid arthritis (Taylor et al. 2004), normal population in Korean (Min et al. 2002), Denmark (Noerholam et al. 2004), Netherland (Trompenaars et al. 2005), Bangladesh (Izutsu et al. 2005), China (Leung et al. 2005), Taiwanese patients with AIDS (Fang et al. 2002), Brazilian outpatients with major depression (Berlim et al. 2005), Brazilian alcoholic male patients (Lima et al. 2005), Taiwanese aged people (Chien et al. 2007), and Iranian population with physical and mental ill health (Nedjat et al. 2008).

Although the use of an instrument does not presume that the quality of life in an individual is the same one as in the sample in which the instrument was developed, the question raised is how important these domains could be for the Iranian population. In the light of our findings, we suggest that a few modifications in the structure of the original questionnaire are needed, in order to achieve more detailed dimensions, and a quality of life model more relevant to Iranian cultural setting. The improvement of the Iranian version of the WHOQOL-BREF could represent an important step towards the assessment and monitoring of QOL, allowing for the evaluation of specific areas of strength and weakness within each individual, which is an important health indicator. Psychosocial interventions, such as integrated psycho-education models, have been successfully used in improvement of QOL of people with different ailments. One of the major limitations of this study is the failure to address how the questionnaire could be differentiated by urban and rural areas. Such an investigation will represent the next stage of our study.

Despite of these limitations, results of the factor analysis in this study provide ample evidence for construct validity for four-factor model of the instrument. The scores of all domains discriminated between healthy persons and the patients. Conclusively, we can claim that the WHOQOL-BREF has adequate psychometric properties and is, therefore, an appropriate measure for assessing quality of life at the domain level in an adult Iranian population. Nonetheless, further research efforts should be directed to a replication of the present results as well as a testing of the temporal stability of the factor structure and suggesting an alternative QOL model that fits the data by an improved manner (Joreskog 1971; Vandenberg and Lance 2000).

References

Anastasia, A. (1990). Validity: Basic concepts. In Psychological testing, 6th edn. (pp. 139–157). New York: Macmillan Publishing Company.

Angermeyer, M. C., Holzinger, A., Matschinger, H., & Stengler-Wenzke, K. (2002). Depression and quality of life: Results of a follow-up study. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 48, 189–199.

Barros da Silva Lima, A. F., Fleck, M., Pechansky, F., de Boni, R., & Sukop, P. (2005). Psychometric properties of the World Health Organization Quality of Life instrument (WHOQoL-BREF) in alcoholic males: A pilot study. Quality of Life Research, 14, 473–478.

Bergner, M., Bobbitt, R. A., Carter, W. B., et al. (1981). The sickness impact profile: Development and final revision of a health status measure. Medical Care, 19, 787–805.

Berlim, M. T., Pavanello, D. P., Caldieraro, M. A. K., & Flck, M. P. A. (2005). Reliability and validity of the WHOQOL BREF in a sample of Brazilian outpatients with major depression. Quality of Life Research, 14, 561–564.

Bonomi, A. E., Patrick, D. L., Bushnell, D. M., & Martin, M. (2000a). Validation of the Unites States’ version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQL) instrument. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 53, 1–12.

Bonomi, A. E., Patrick, D. L., Bushnell, D. M., & Martin, M. (2000b). Quality of life measurement: Will we ever be satisfied? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 53, 19–23.

Chien, C., Wang, J., Yao, G., Sheu, C., & Hsieh, C. (2007). Development and validation of a WHOQOL-BREF Taiwanese audio player-assited interview version for the elderly who use a spoken dialect. Quality of Life Research, 16, 1375–1381.

Fang, C. T., Hsiung, P. C., Yu, C. F., Shen, M. Y., & Wang, J. D. (2002). Validation of the Wolrd Health Organization quality of life instrument in patients with HIV infection. Quality of Life Research, 11, 753–762.

Hsiung, P. C., Fang, C. T., Chang, Y. Y., Chen, M. Y., & Wang, J. D. (2005). Comparison of the WHOQOL-BREF and the SF-36 in patients with HIV infection. Quality of Life Research, 14, 141–150.

Hunt, S. M., McKenna, S. P., & McEwan, J. (1989). The Nottingham health profile. Users manual. Revised edition.

Izutsu, T., Tsutsumi, A., Islam, M. A., Mstsuo, Y., Yamada, H. S., Kurita, H., et al. (2005). Validity and reliability of the Bangla version of WHOQOL-BREF on an adolescent population in Bangladesh. Quality of Life Research, 14, 1783–1789.

Jang, Y., Hsieh, C. L., Wang, Y. H., & Wu, Yh. (2004). A validity study of the WHOQOL-BREF assessment in persons with traumatic spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 84, 1890–1895.

Joreskog, K. G. (1971). Simultaneous factor analysis in several populations. Psychometrika, 57, 409–426.

Kalfoss, M. H., Low, G., & Molzahn, E. (2008). The suitability of the WHOQOL-BREF for Canadian and Norwegian older adults. European Journal of Ageing. doi:10.1007/s10433-008-0070-z.

Leplege, A., Reveillere, C., Ecosse, E., Caria, A., & Rivier, H. (2000). Psychometirc properties of a new instrument for evaluating quality of life, the WHOQOL-26, in a population of patients with neuromuscular disease. Encephale, 26, 13–22.

Leung, K. F., Wong, W. W., Tay, M. S. M., Chu, M. M. L., & Ng, S. S. W. (2005). Development and validation of the interview version of the Hong Kong Chinese WHOQOL-BREF. Quality of Life Research, 14, 1413–1419.

Lima, A. F., Fleck, M., Pechansky, F., Boni, R., & Sukop, P. (2005). Psychometric properties of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Instrument (WHOQoL-BREF) in alcoholic males: A pilot study. Quality of Life Research, 14, 473–478.

Min, S. K., Kim, Ki., Lee, C. I., Gung, Y. C., Suh, S. Y., & Kim, D. K. (2002). Development of the Korean version of WHO Quality of Life scale and WHOQOL-BREF. Quality of Life Research, 11, 593–600.

Nedjat, S., Montazeri, A., Holakouie, K., Mohammad, K., & Majdzadeh, R. (2008). Psychometric properties of the Iranian interview-administered version of the World Health Organization’s Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQOL-BREF): A population-based study. BMC Health Services Research, 8, 61. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-8-61.

Noerholam, V., Groenvold, M., Watt, T., Bjorner, J. B., Rasmussen, N. A., & Bech, P. (2004). Quality of life in the Danish general population-normative data and validity of WHOQOL-BREF using Rasch and item response theory models. Quality of Life Research, 13, 531–540.

O’Caroll, R. E., Smith, K., Couston, M., Cossar, J. A., & Hayes, P. C. (2000). A comparison of the WHOQOL-100 and the WHOWOL-Bref in detecting change in quality of life flowing liver transplantation. Quality of Life Research, 9, 121–124.

Sarrafzadegan, N., Baghaiei, A. M., Sadri, Gh., et al. (2006). Isfahan healthy heart programme: A comprehensive integrated community-based programme for non-communicable disease prevention. Prevention and control Journal, 2(2), 73–84.

Sarrafzadegan, N., Sadri, Gh., Malek Afzali, H., et al. (2003). Isfahan healthy heart programme: A comprehensive integrated community-based programme for cardiovascular disease prevention and control Design, method, and initial experience. Acta Cardiologica, 58(4), 309–320.

Skvington, S. M., Loftfy, M., & O’Connell, Ka. (2004). The World Health organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: Psychiatric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Quality of Life Research 13:299–311, 9–3110.

Taylor, W. J., Myers, J., Simpson, R. T., McPherson, K. M., & Weatherall, M. (2004). Qulaity of life of people with rheumatoid arthritis as measured by the world health organization quality of life instrument, short form (WHOQOL-BREF): Score distributions and psychometric properties. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 51, 350–357.

Tazaki, M., Nakane, Y., Endo, T., Kakikawa, F., Kano, K., Hiroomi, K., et al. (1998). Results of qualitative and field study using the WHOQOL instrument for cancer patients. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology, 28, 134–141.

Trompenaars, F. J., Masthoff, E. D., Van Heck, G. L., Hodiamont, P. P., & De Vries, J. (2005). Content validity, construct validity, and reliability of the WHOQOL-Bref in a population of Dutch adult psychiatric outpatients. Quality of Life Research, 14, 151–160.

Vandenberg, R. J., & Lance, C. E. (2000). A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices and recommendation for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 3, 4–70.

Ware, J. E., Snow, K. K., Kosinski, M., & Gadek, B. (1993). SF-36 health survey: Manual and interpretation guide. MA, USA: New England Medical Center.

WHOQOL Group. (1993). Study protocol for the World Health Organization project to develop a Quality of life assessment instrument (WHOQOL). Quality of Life Research, 2, 152–159.

WHOQOL Group. (1998a). The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): Development and general psychometric properties. Social Science and Medicine, 46, 1569–1585.

WHOQOL Group. (1998b). Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychological Medicine, 28, 551–558.

Yao, G., & Wu, C. (2005). Factorial invariance of the WHOQOL-BREF among diseases groups. Quality of Life Research, 14, 1881–1888.

Yao, G., Wu, C., & Yang, C. (2008). Examining the content validity of the WHOQOL-BREF from respondents’ perspective by quantitative methods. Social Science and Medicine, 85, 483–498.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by the office of the deputy of research Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan-Iran. It was conduced by the Medical Education Research Centre in joint venture with Isfahan Cardiovascular Research Centre, affiliated to Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. We are grateful to Dr Adibi P, the deputy research, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan Iran. We are extremely grateful to Professor R. K. Hebsur, ex-head of the Department of Research methodology, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai-India, for his meticulous and careful editing work and useful suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10597-010-9292-6

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Usefy, A.R., Ghassemi, G.R., Sarrafzadegan, N. et al. Psychometric Properties of the WHOQOL-BREF in an Iranian Adult Sample. Community Ment Health J 46, 139–147 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-009-9282-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-009-9282-8