Abstract

The aim of this study was to examine the extent to which intimate partner violence (IPV) is discussed in couple therapy, what the participants say about it and how, and how the participants’ electrodermal activity (EDA) is activated during these discussions. We studied four couples for whom IPV was an issue in dialog with their therapists. We used thematic analysis and examined the differences in EDA (measured as skin conductance responses, SCRs) between the participants. We found that although IPV was discussed relatively little in therapy, when the topic arose the victims took an active part in the discussion. We also found that the main themes were descriptions of IPV, explanations for IPV and the consequences of IPV, and that most of the SCR peaks occurred during talk on these themes. Moreover, differences were observed between participants in the frequency of peaks, therapists manifesting more peaks than clients. However, the overall proportions of the peaks were rather small, and no difference in mean SCR was found between victims, perpetrators or therapists. These results indicate that victims are not afraid to speak about IPV and that therapists are able to deal with it; however, dealing with IPV in therapy merits more attention. Moreover, our results showed that the participants experienced talking about IPV differently, an observation that should be taken into account in the therapy process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Intimate Partner Violence and Couple Therapy

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is considered to be difficult issue in couple therapy for both the clients and the therapists. The aim of our study was to examine how much discussion of IPV takes place in couple therapy when IPV is the main purpose of the sessions, what the participants say about it and how. We also measured the participants’ psychophysiological arousal to determine level of psychosocial stress during the talk about IPV.

Couple therapy is a somewhat controversial approach to treating IPV, some practitioners believing that it increases the risk for the victim’s safety and reduces the perpetrator’s responsibility for the violence (Stith et al. 2011). Hence gender-differentiated treatments are generally used in cases of IPV. Moreover, the male partner is usually assumed to be the perpetrator and his female partner the victim (Stith et al. 2012). However, community-based studies have indicated that the gender distribution of perpetrators and victims of IPV is more heterogeneous than previously thought, although statistics on persons arrested for violent behavior and shelter-seeking victims continue to be substantially skewed by gender. The idea of a female perpetrator can be difficult for therapists to internalize including in cases where the violence is psychological (Kaufman 1992). Female aggressors are perceived as less able to inflict harm than their male counterparts, even when engaging in the same behaviors (Hammock et al. 2017).

Victims of IPV are commonly encouraged to exit their relationship, and are often recommended to seek individual therapy to deal with their experience of IPV (Karakurt et al. 2013). However, studies show that a considerable number of couples remain in their relationship even where the violence perpetrated has been severe (e.g. Stith et al. 2011). In couple therapy, it is essential to motivate the perpetrator to take responsibility and to help the couple to improve their mutual communication and interaction. This can, of course, present challenges; many therapists do not ask their clients about violence because they may feel that they lack knowledge on how to deal with it. It has also been shown that women’s viewpoints have not been adequately taken into account in therapy (Husso 2003; Kaufman 1992). One potential explanation for this is that family therapists may be hesitant about breaking the social norm according to which the man is the controller in a heterosexual relationship (Kaufman 1992) and hesitate to address gender and power issues (Knudson-Martin 2013). Challenging gendered power differences means therapists cannot be neutral and requires that they take an active role in relation to taken-for-granted practices. Family therapists have also been found to downplay and even deny the existence of IPV (Kaufman 1992). IPV is a difficult subject for therapists to deal with; for example, therapists have reported fear of exacerbating the violence, worry about managing their own anxiety and insecurity about their ability to work with partner abuse (Karakurt et al. 2013; Brosi and Carolan 2006). However, they have also reported trust in couple therapy as a treatment for IPV. It must be noted that lack of trust between partners may also complicate the therapy process from the therapist’s standpoint (Vall et al. 2014).

Dealing with IPV in couple therapy is also considered to be difficult for the couple. Victims may be cautious to about discussing IPV for fear of provoking or insulting their partner (Kaufman 1992; Stith et al. 2011). However, most couples seem not to think that discussing IPV will lead to violent acts by the perpetrator (Stith et al. 2011). According to Husso (2003), describing oneself to others as a target of violence is a pervasive, physical process that may not only relieve but also frighten and be hurtful to the victim, while inducing fear, confusion and shame in listeners. Difficulty in expressing one’s thoughts about IPV, and especially blaming the victim for supposedly provoking the perpetrator or not being able to function in a relationship, are central in the process of generating feelings of shame. However, more and more studies are showing that well-organized couple therapy can be as safe and effective as other general treatments for intimate partner violence (McCollum and Stith 2008; Stith et al. 2003), especially in situational couple violence, where the violence is not usually as severe as in intimate terrorism (Stith et al. 2011).

Partners’ Views on Intimate Partner Violence

Partner´s views on the consequences and causes of IPV may differ widely. Reports of physical injuries have been found to differ between victims and perpetrators of IPV: victims have reported more injuries than perpetrators have admitted causing (Dobash et al. 2000). Perpetrators have downplayed or denied causing injuries or have claimed unawareness of them (Dobash et al. 2000), and they have invalidated women’s experiences and views of violent events (Husso 2003). Victims in turn have reported negative emotional consequences, including stress, anxiety, depression and fear of violence, while perpetrators often appear unaware of or insensitive to the consequences of violence (Dobash et al. 2000; Husso 2003). Women often report fear as the hardest consequence of violence (Husso 2003). Moreover, not only perpetrators but also victims have been found to downplay or deny IPV (Kaufman 1992). According to Päivinen et al. (2016b), victims’ and perpetrators’ views on IPV and its severity and their descriptions of specific violent situations can differ substantially. They may also disagree on the definition of violence or who is responsible for it. However, views on what counted as physical violence between victims and perpetrators in couple therapy were found to be congruent in most couples, whereas disagreements arose over psychological violence (Vall et al. 2017). Views on what can be considered psychological violence and who has used it differed between victims and perpetrators.

Both victims and perpetrators have given several explanations for IPV, alcohol abuse being one of the more common (Dobash et al. 2000; Husso 2003; Holma et al. 2006). Drinking has also been seen to decrease perpetrators’ admission of responsibility for IPV (Husso 2003). Moreover, IPV has been explained by jealousy (Dobash et al. 2000) and by stress and negative emotional state or mood (Husso 2003; Holma et al. 2006). Violent men find it hard to accept and admit their responsibility for violence, and often tend to outsource the reasons for violence far away from themselves (Holma et al. 2006).

Autonomic Nervous System and Emotions

ANS activity is associated with several features of emotional behavior (Andreassi 2007), and is thus considered a significant factor in the emotion response (Kreibig 2010). James and Lange (James 1894) were the first to consider that emotions derive from bodily changes. However, theorists’ views of the degree of specificity of ANS activation in the emotion response have varied, ranging from undifferentiated arousal to specific assumptions of autonomic response patterns (for review, see e.g. Kreibig 2010). In the model of embodied affectivity, bodily responses are considered an essential component in the experience of emotions (Fuchs and Koch 2014). The model suggests that emotions result from the circular interaction between affective features in the environment and the person’s bodily resonance, manifested in e.g., sensations, postures and movements. The bodily functions color or charge the environment with affective features and thus have an effect on the experience of emotions, although bodily resonance is nonconscious. This same phenomenon also applies to interaffectivity, which refers to the interaction of embodied affectivity between individuals, each modifying the emotional experience of the other. Thus, emotions are mainly shared states experienced through interbodily affection, a process that can be considered as the bodily basis of empathy and social understanding.

Electrodermal Activity

Electrodermal activity (EDA) is a frequently used measure of psychophysiological arousal, and it refers to the capacity of the skin to conduct electricity (Hugdahl 1995). Unlike several other functions of the ANS that are innervated by both the PNS and the SNS, EDA is innervated solely by the SNS (Andreassi 2007). Increased EDA has been suggested to reflect cognitively or emotionally mediated motor preparation (Fredrikson et al. 1998), a notion which is consistent with the view that emotions motivate action (Brehm 1999). Moreover, in his review, Crider (2008) found in his review that greater EDA response instability was related to the suppression of emotions and agreeableness, whereas greater stability was related to the active expression of emotions and antisocial behavior.

EDA is considered to be a sensitive marker of personally significant events, as these are usually related to emotions, novelty and attention (Sequeira et al. 2009). A close temporal relation between EDA and emotional experience in healthy research participants has been found, indicating that EDA reflects emotional reactivity (Hot et al. 2005). In her meta-analysis, Kreibig (2010) found that increased EDA was related to the most positive and most negative emotions such as anger, anxiety, embarrassment, fear, amusement, happiness, and joy. Decreased EDA, in turn, was associated with only a few emotions: non-crying and acute sadness, contentment, and relief. However, EDA has also been found to be clearly higher during voluntary facial portrayal of negative emotions (anger, fear, sadness and disgust) than during the portrayal of positive emotions (happiness and surprise; Levenson et al. 1990).

Novelty and the significance of the stimulus seem to be central in EDA response (Bradley 2009). Even a novel neutral stimulus caused increased EDA, although novel pleasant and unpleasant stimuli caused larger increases in EDA than a neutral stimulus. When the stimuli were repeated, EDA was clearly lower for the repeated neutral stimulus than in the novelty situation, although the increases in EDA remained significant. Supporting Bradley’s findings, increased EDA was also found to be related to attention to threat cues in the general population (Löw et al. 2008; Wiemer et al. 2013) and people with phobia (Wessel and Merckelbach 1998), and to reward cues (Löw et al. 2008).

A relation between EDA and stress has also been found. EDA increased in stressful situations that included cognitive, emotional, acoustic and motivational stressors (Reinhardt et al. 2012), and EDA peaks were related to psychosocial stress (Setz et al. 2010). EDA was also associated with stressful life events (Clements and Turpin 2000; Najström and Jansson 2007). After controlling for trait anxiety, increased EDA observed during the viewing of masked (i.e. unavailable for conscious processing) threatening pictures predicted greater emotional distress in response to naturally occurring stressful events (Najström and Jansson 2007). However, the greatest exposure to stressful life events has been found to be related to the hyporesponsive pattern of EDA, manifested as lower EDA, compared to moderate exposure to stressful life events, manifested as increased EDA (Clements and Turpin 2000).

Gottman, Jacobson, Rushe and Shortt (1995) were the first to examine the psychophysiological responses of men who had been violent towards their intimate partner. They measured the heart rate of men in marital conflict and found two different types of IPV perpetrators: type I perpetrators, who were more violent and showed autonomic underarousal, and type II perpetrators, who were less severely violent and showed autonomic hyperactivity. The EDA of perpetrators has also been studied. Babcock et al. (2005) compared the EDA of severely violent perpetrators (considered as type I) to low-level violent perpetrators and nonviolent men during a conflict discussion between partners and found that low EDA was associated with antisocial behavior in severely violent men. Romero-Martínez et al. (2013) also compared the EDA of IPV perpetrators (considered as type II) and nonviolent men, measured before, during and after they talked about their own experiences and problems related to IPV and their opinions about IPV legislation. They found that the perpetrators showed higher EDA responses during the recovery phase than the nonviolent men. Thus, the findings of both Babcock et al. and Romero et al. supported those of Gottman et al. for different perpetrator types. Kalliomäki (2015), in turn, examined the EDA of a perpetrator while the victim was talking about IPV in couple therapy and found that the perpetrator’s EDA increased during the victim’s speech. However, the EDA changes were not as large as they were later in the therapy session when other subjects were being discussed. In a stimulated recall interview (described in Seikkula et al. 2015), the perpetrator described talking about IPV as unpleasant, and something he would rather not talk about. This along with his EDA responses indicated that the perpetrator felt guilty and feared the therapists’ reaction to his IPV. It has been noticed that targeting the other person’s identity, blaming the other, is a strongly felt discursive act which also manifests at the level of EDA (Päivinen et al. 2016a).

The aim of our study was to examine to what extent IPV is discussed in couple therapy, what the participants say about it and how, and how their EDA (measured as skin conductance responses, SCRs) is related to what is said in these discussions. An additional aim was to observe what themes are talked about, where the SCR peaks occur, and how the individuals present participate in general discussions about IPV. To our knowledge, EDA has not previously been studied among IPV victims and therapists dealing with IPV, while overall psychophysiological responses in the couple therapy context have been little researched. To gain a broader understanding about best to deal with IPV in couple therapy, we combined EDA analysis with a qualitative analysis of discussions on the topic of IPV. Our research questions were as follows:

-

1.

How much discussion of IPV takes place in couple therapy?

-

2.

What IPV themes are discussed, and how, in couple therapy?

-

3.

Do the participants differ in (a) SCR means, (b) the frequencies and proportions of SCR peaks, and (c) the proportions of SCR peaks during different IPV discussion themes?

Method

Our study forms part of the research project “Relational Mind in Moments of Change in Multi-actor Therapeutic Dialogues”. Relational Mind is a part of the “Human Mind” research programme funded 2013–2016 by the Academy of Finland (Seikkula et al. 2015). The project aims to expand understanding of the embodiment of multi-actor therapeutic dialogues and synchronization in embodied responses between participants. The project examines clients and therapists in the same way, with each participant’s ANS responses gathered in two therapy sessions during the therapy process (generally the 2nd and 6th sessions). Moreover, each measurement session is followed by stimulated recall interviews (described in Seikkula et al. 2015).

Material

For this study, we examined four cases, each with two clients and two therapists. The clients were couples who had sought treatment for IPV from the Jyvaskyla University Psychotherapy Training and Research Centre. Before treatment, the couples’ situations and backgrounds were examined with interviews and questionnaires. Both partners were interviewed to assess the willingness to participate in couple therapy and the safety to discuss difficult issues during the session.

The clients were 30–45 years old. Two couples were cohabiting (cases 1 and 4), one couple had registered their partnership (case 2) and one couple was engaged (case 3). In each case, at least one partner had a child or children. The clients in case 2 had elementary school education and the other clients upper secondary education. In cases 1 and 2, the perpetrators had been diagnosed with depression for which they were receiving medication. In case 2, the victim had diagnosed bipolar disorder and was receiving medication for that condition. In case 4, the victim reported feelings of anxiety, melancholy and fear. Each case was conducted by two co-therapists, and in the present four cases these therapist pairs were formed from a pool of five therapists. All the therapists were psychologists. Four of them had training in family therapy and several years of experience in clinical work. One therapist was attending psychotherapy training and was less experienced in clinical work. Of the four therapist dyads, three comprised a female and a male therapist and one comprised two male therapists. Prior to therapy, all four couples had sought help from a crisis center for IPV, especially physical IPV. Despite the IPV in their relationships, the couples were, at least at the beginning of the treatment, motivated to stay together.

The therapy sessions were non-manualized and were conducted in the format of co-therapy including reflective conversation between the therapists at the end of each session. The therapies followed a need-adapted approach, taking into account the needs and aims of each couple. The therapists were trained on IPV-specific treatment including for example assessing safety and bringing up IPV in the conversation. Thus while aware of some important issues when dealing with IPV, the therapists could follow their own orientation or treatment approach. Hence various modes of therapy—dialogical, narrative and reflective—were used. The sessions lasted 90 min and were video-recorded with two cameras for display on a split screen monitor showing the clients on one side and therapists on the other. Moreover, the whole therapy setting with all participants and the facial image of each participant were video-recorded, which enabled more precise analysis of the interaction between the participants. The therapy sessions were also audio-recorded.

In the second session, the ANS responses of the participants were measured. EDA was measured from the palm of each participant’s non-dominant hand with two silver chloride electrodes, using the BrainProducts acquisition system (Germany), which enabled the simultaneous measurement of all four participants. The EDA data were synchronized with the video recordings by using marker pulses so that the EDA could be linked to the events of the therapy sessions at specific points. The ethical board of the University of Jyvaskyla approved the study design, and the clients gave their informed consent to participate in the study.

Analysis

We began our analysis with a qualitative thematic analysis of all the IPV-related extracts. Thematic analysis is a theoretically flexible method that facilitates identification of the themes of interest in the data (Braun and Clarke 2006). Since we wanted to gain as complete a view of each of the four cases as possible, we began by watching the first three therapy sessions with each couple. However, for this study, only the analysis of the second sessions, i.e., the sessions when EDA was measured, are reported. We selected extracts from the recordings where IPV in the couple relationship was explicitly discussed. Thus, we did not include extracts containing only a brief allusion to IVP. We then continued by analyzing and pruning the extracts, from which we selected 11 for further analyses.

Next, we transcribed the 11 extracts. We then categorized them on the basis of their content and extracted themes from them. If a topic came to the fore several times in the therapists’ or clients’ speech, we regarded it as a separate theme. However, the themes varied in extent: some comprised less discussion than others.

After categorizing the extracts, we translated the parts presented here from Finnish into English and gave the clients the following pseudonymes: case 1 Heidi (victim) and William (perpetrator), case 2 Miranda (victim) and Susan (perpetrator), case 3 Lisa (victim) and John (perpetrator), and case 4 Kate (victim) and Steven (perpetrator). The therapists were named T1-T5.

After completing our qualitative analysis of the IPV extracts, we began the EDA analysis. First, we examined the raw EDA data of each participant to gain an overall picture of EDA in the therapy sessions before focusing on the IPV extracts. We then analyzed the EDA data in more detail. The fast components of EDA, i.e., skin conductance responses (SCRs), coincide with SNS activation, and were detected using the Matlab-based Ledalab program (Benedek and Kaernbach 2010). The SCR signals were then standardized for each participant to facilitate comparability between the participants. Values higher than two standard deviations above the mean were considered statistically significant (at the level of 0.05) and are henceforth referred to as SCR peaks.

To determine the proportion of IPV-related talk in the discussions we began by measuring in the seconds the amount of such talk in each IPV extract. We then calculated the corresponding proportion in each of the four cases and calculated the sum total for all cases. As a last step, we compared the proportions of IPV talk in the whole session in each case with the total for all cases.

To examine possible differences between clients and therapists in their mean SCR levels during the selected IPV extracts, we first formed the participants into three groups: victims, perpetrators and therapists. The three groups were considered to be independent of each other. We then calculated the mean for each participant in each extract (n = 44). While the variances of the groups were equal, the data were not normally distributed, and therefore we conducted a nonparametric Independent-Samples Kruskal–Wallis test. The test was two-tailed with the level of significance determined as p < 0.05. The test was performed with SPSS 22.0.

To explore the frequencies and proportions of the SCR peaks in the IPV extracts, we calculated the frequencies of the peaks for each participant group (victims, perpetrators, therapist 1 and therapist 2). The co-therapists were examined individually to gain a more detailed picture of the differences in SCR peaks between the therapists. However, we also calculated the overall frequencies for both clients and therapists. Next, we compared the frequencies of the peaks to the overall frequencies of the peaks for each participant, group and case. However, due to the small sample size, statistical comparison of the frequencies and proportions between the groups was not possible.

To examine the proportions of SCR peaks of all the SCR peaks during the discussion themes in the IPV extracts, we first formed four groups: victims, perpetrators, clients and therapists. We then calculated the frequencies of the peaks observed during talk on the themes for each group and compared them to the overall frequencies of the peaks to obtain the proportions of peaks in each group.

Results

Proportion of Time Spent Discussing IPV in the Therapy Sessions

To study how much time the participants spent discussing IPV in the therapy sessions, we first measured the time spent discussing IPV in seconds in each of the selected IPV extracts. We then compared the proportion of the time spent on IPV during the whole session for each case (see Table 1). It is clear from the table that IPV was discussed at greatest length in case 1 and least in case 2. In cases 3 and 4, the proportion of time spent on IPV was almost equal. Overall, IPV was discussed for only a few moments in each case.

The IPV Themes Discussed in Therapy

Description of IPV

We analyzed what kinds of themes generally occurred in the IPV extracts and mostly found talk describing IPV and its consequences and offering explanations for it. Descriptions of IPV included descriptions of specific violent situations and of the perpetrator’s violent behavior in general. In these descriptive extracts, we found that the victims expressed their point of view about the perpetrators’ violent behavior more spontaneously than the perpetrators themselves. Moreover, the therapists actively asked about violence. The perpetrators in turn mainly described their acts of violence only when directly asked about them by the therapists.

We also found congruency between victims’ and perpetrators’ views on IPV in cases 1, 2 and 4; however, in case 3 the severity of the IPV described by the victim (Lisa) was greater than that described by the perpetrator (John). In extract 1 in case 3, T3 puts it to John that his feeling of insecurity in the relationship was manifested as jealousy and also in controlling and following Lisa; John, however, does not consider his feeling of jealousy to be severe. John had also earlier disagreed with Lisa’s description of this IPV (see extract 6). Note that time in the extracts is marked as h:min:sec. For the key to the transcription symbols, see Table 5 in Appendix.

Extract 1, case 3 (48:37-48:56)

T3: but your insecurity about the continuation of your relationship manifested like as jealousy and still after that also as some kind of controlling and following

John: mm yes (.) yes a bit like that but nothing morbid and like that way everyday

We also discovered mutual IPV in case 4, when the victim (Kate) talked about how she was psychologically violent towards the perpetrator (Steven) in conflict situations (see extract 7). However, the therapists did not comment on this.

Explanations for IPV

Explanations for IPV included discussion on the possible reasons why the perpetrator acted violently towards his or her partner. Such explanations were related to the perpetrators’ personal qualities, the dynamics of the relationship and contextual factors. The possible explanations offered differed widely, including disappointments in the relationship, perceiving the violent situation as an accident and the perpetrator’s temper and alcohol use. The victims and therapists mainly discussed explanations for IPV, the perpetrators, in turn, did not offer explanations for their IPV spontaneously, but only did so when prompted or explicitly asked by the therapists.

In extract 2 in case 2, the therapists (T3 and T4) bring up many different reasons for the IPV in their reflective conversation: disappointments in the relationship, inability to give in to partner’s wishes, fear of abandonment, contradictory ways of acting in conflicts, and difficulty in trusting one another. Neither the victim (Miranda) nor the perpetrator (Susan) comment on the therapists’ views.

Extract 2, case 2 (1:18:56-1:19:49)

T4: -- and anyway maybe in this conversation we have been much like ((clearing throat)) how erm from where that violence has probably risen or (.) like in my opinion (.) surely it could somehow be related to these fundamental disappointments or expectations of one another and which is burdening and it is difficult for you to get round to TALK about it but now ↑ here it has been opened pretty much

T3: and surely then also these like quite contradictory ways of acting in specific crisis situations (.) well and- and in the c-conflict situation which like has been (.) brought such pressure inside hh in that situation so that you haven’t been able to give ↑in or go ↑away or (.) fear of a-abandonment and lack of trust has existed and all of this is like as entangled there which has (.) brought those feelings and such (2) well to the surface in that situation

T4: mm

T3: and brought that violence

Consequences of IPV

The consequences of IPV included discussion on caution and fear of violence, commitment to the relationship, trust, the traumatic effects experienced by the victim, and the fear of using violence and the shame experienced by the perpetrator. The consequences of IPV were mostly discussed from the victim’s perspective, but occasionally also from the perpetrator’s viewpoint. Although the therapists mostly prompted the perpetrators to talk about the consequences of IPV, we found that the victims talked significantly more about these than the perpetrators. The therapists also actively took part in discussions on the consequences of IPV and reflected on the clients’ views. The victims talked about how the violence had affected their own behavior and caused fear and apprehension, feelings and experiences that the perpetrators mainly seemed to understand. In extract 3 in case 2, T3 puts it to Miranda that she feels she has to avoid expressing her frustration because of her fear of violence. Both Miranda and Susan agree.

Extract 3, case 2 (44:48-45:00)

T3: so you have to swallow your own frustration [and there is some kind of fear of arguing

Miranda: [yes

T3: [and its starting is there a fear even of something like that the arguing escalates like

Susan: [mm

T3: into violence or

Miranda: ((nodding))

The perpetrators discussed their own experiences of the consequences of IPV such as the fear of using violence and their feeling of shame, but only when asked directly by the therapist to do so. There was also one case (case 3) where the consequences of IPV were not discussed at all.

Overall, across all the discussion themes, the victims and therapists were more active participants than the perpetrators. We noted that the victims expressed their views spontaneously, whereas the perpetrators gave their views mainly when directly asked or prompted to speak by the therapists. Moreover, the therapists seemed to be more interested in obtaining information about IPV from the victims, asking them specific questions and reflecting on what they said. The couples’ descriptions of IPV, explanations for IPV and views about the consequences of IPV were also rather consistent with each other.

SCR Means and Peaks in IPV Extracts

As earlier described we first formed three groups: victims, perpetrators and therapists. We then calculated the SCR mean of each participant for each extract (n = 44). Differences in means between the groups were tested using the Independent-Samples Kruskal–Wallis test. The test showed no significant differences in participant means between the groups [H (2) = 1,186, p = 0.553].

We calculated the frequencies and proportions of the clients’ and therapists’ SCR peaks during discussions of IPV in the therapy session. The victims showed 13 and perpetrators 14 peaks during the IPV extracts, yielding a total of 27 peaks for the clients. The therapists showed 36 peaks in the same extracts, and thus approximately a third more than the clients.

Table 2 presents the proportions of SCR peaks in the IPV extracts of all SCR peaks for clients and therapists separately. The overall proportions of the peaks in the IPV extracts of all peaks in the therapy session were rather small. Most of the variance in the proportions of peaks was observed among the therapists and perpetrators while the least variance was found among the victims. The therapists showed the highest proportion of the total peaks in all three participant groups. Moreover, in 3 of the 4 cases (cases 1, 2 and 4) the therapists showed the highest proportion of peaks compared to the other participants. Therapists T2 and T5 also showed the two highest proportions of peaks of all the participants, and these were the only proportions that were over 20%. However, therapists T4 and T5 also showed the second and the third lowest proportions of peaks. The perpetrator in case 2 (Susan) had the lowest proportion of peaks of the all the participants, i.e., she showed no peaks at all. Case 1 showed the highest proportion of peaks of all the cases, and the proportions of the peaks for both clients and therapists were also the highest proportions in their respective groups. Moreover, IPV received the most discussion in case 1. Case 3 showed the lowest proportion of peaks of all cases, and the therapists in case 3 also showed the lowest proportion of the peaks in their group. However, IPV received the second largest amount of discussion in case 3, while the lowest proportion of peaks in the client group were found in case 2.

The Discussion Themes During SCR Peaks and SCRs in the IPV Extracts

First, we analyzed the discussion during SCR peaks in the IPV extracts separately for each case and identified subthemes. We then merged all the cases together and extracted eight main discussion themes, including subthemes (see Table 3). Only two of our main discussion themes included more than one subtheme—the remaining subthemes were not suitable for merging and thus were considered main themes l. The eight main discussion themes were (1) consequences of IPV, (2) explanations for IPV, (3) description of IPV, (4) monitoring IPV, (5) criticism of perpetrator by victim, (6) commitment to the relationship, (7) psychological IPV shown towards perpetrator by victim during conflicts, and (8) interruption by therapist. Consequences of IPV included subthemes such as the victim’s giving up, fear of violence, trust issues and traumatic effects. Monitoring IPV, in turn, included subthemes such as exploring specific violent situations and the perpetrator’s general violent behavior. We also analyzed SCRs in extracts showing a high frequency of peaks.

Consequences of IPV discussed during SCR peaks included different consequences for victims and perpetrators, effects on trust and being on guard. In extract 4 in case 4, T3 asks Kate about trust after IPV, and Kate answers that her trust in the relationship is still in need of repair. During T3’s question, T3 himself, T4 and Steven showed peaks, and at the end of Kate’s answer T5 showed a peak after Kate’s talk about being on guard (see peaks in extract).

Extract 4, case 4 (1:03:44-1:04:06)

T3: has (T3’s peak) your trust been restored to the level (T5’s peak) that- that it was before this violence or is there still (Steven’s peak) (3) patching up

Kate: like there’s patching up like I’m a bit (.) on my toes in some situations just like if for example there is an argument and Steven raises his voice (.) so then I- I’m quite on guard ((becomes emotionally moved)) (T5’s peak)

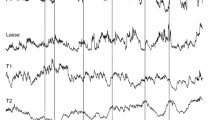

The standardized SCRs for each participant in extract 4, presented in Fig. 1, show that at the beginning of the extract Kate, Steven and T5 showed increasing SCRs while, simultaneously, T3 showed decreasing SCRs. However, Steven’s highest SCRs (also his peak) occurred later than those of Kate and T5. At the end of the extract (from approximately 15 s onwards) Kate, Steven and T3 showed decreasing SCRs while T5 showed increasing SCRs. However, Steven’s SCRs began to increase 2–3 s later, thereafter decreasing once again. Overall, the SCR graphs for Steven and T5 resembled each other, although Steven’s peak occurred 2–3 s later than T5’s, and Steven’s SCRs also decreased at a slower rate than T5’s. Kate and T3 showed similar SCR graphs from approximately 5 s onwards.

Explanations for IPV varied. In extract 5 in case 1, T2 asks William whether his family was somehow involved when he was choking Heidi. Earlier in the session, discussion has occurred on how William’s childhood family interferes in and is also a cause of, the couple’s quarrels. William, however, answers that it was only him. T2 then summarizes this by saying that William’s family was not a factor in the attempted strangulation, and Williams confirms this. During T2’s question both T2 himself and Heidi showed peaks, and T2 two further peaks during his second speech turn (see peaks in extract).

Extract 5, case 1 (54:39-54:59)

T2: what do you William think yourself about that ((looks down)) (.) situation when you were choking (1) Heidi (T2’s peak) (.) (Heidi’s peak) so erm (.) was it you or was your family involved °somehow°

William: yes it’s me

T2: mm↑ (2) that (T2’s peak) (.) you have ((gestures with hand)) (.) this kind of connection to that (.) your own family didn’t involve [any way in that situation] (T2’s peak)

William: [no-o

Overall, T2’s SCRs differed from those of the other participants, remaining high (2 standard deviations above the mean) during most of extract 5 (see Fig. 2). Moreover, Heidi, T1 and T2 showed similar SCR graphs, albeit their SCRs differed, with T2 showing the highest SCRs and T1 the lowest. Their SCRs increased at the beginning of the extract (although Heidi also showed a decrease during the same interval) and began to decrease from approximately 7 s onwards. However, of all the participants, Heidi and T1 showed the closest resemblance in their SCRs. Williams’s SCRs differed from those of the other participants at the beginning of the extract, but resembled those of T2 at the end of the extract (from approximately 8 s onwards).

During criticism of the perpetrator by the victim only two peaks occurred and this theme was present only in case 3. In extract 6 in case 3, Lisa talks about John’s violent raging and criticizes John for not repairing the damage that he has done in their home and not understanding that the marks of his raging are constant reminder of his violent acts. John agrees with Lisa’s criticism. T3 does not know what raging Lisa is talking about and asks about it. Both Lisa and John answer the question, but they do not agree about the severity of John’s behavior; Lisa says that John has smashed up “half the house”, but John denies this.

Extract 6, case 3 (35:57-36:43)

Lisa: and then there were these marks of John’s raging so I was always annoyed when I saw every day them like some dents on cabinets and what he has smashed up there and the refrigerator (.) it annoyed me then I bought these doors with my ow- own money and (.) something like well every day when you see things they come back to your mind so I said about it too John didn’t quite understand that I was really annoyed (.) they now must now be repaired and patched up and this man did a renovation there then and

John: yeah yeah (John’s peak)

T3: erm what raging are you talking about (.) now I didn’t quite catch it

Lisa: well then when (T3’s peak)

John: well then drunk terribly drunk when there have had been rows then something always gets thrown

Lisa: well half of the house has been smashed up they are so bad those rows [that are something that

John: (John’s peak) [half of the house hasn’t been smashed up it’s (Lisa’s peak) completely (John’s peak) rubbish that but

In this extract, the clients showed most of the peaks, and John the first peak after Lisa’s criticism of him (see peaks in extract). T3, in turn, showed a peak after he had asked about the violent raging. Moreover, Both Lisa and John showed peaks when describing the IPV: John after Lisa had said that John has smashed up “half the house” and Lisa and John almost simultaneously when John denied this. Overall, T3’s SCRs differed from those of the other participants; he had shown a high peak just before this extract, and thus his SCRs were decreasing at the beginning of the extract (see Fig. 3). He also showed the highest peak of the participants in this extract. John and T5 showed similar SCRs at the beginning of the extract (until 20 s), and also did Lisa and T5 at the end of the extract (from approximately 27–39 s).

The peaks during talk about psychological IPV by the victim in conflict situations and commitment to the relationship and during interruption by a therapist occurred in a few extracts (only one extract per theme). In extract 7 in case 4, Kate describes how she had acted towards Steven in conflict situations, including “bashing” and blaming him. However, the therapists did not react to this description of Kate’s psychological violence towards Steven, and the issue was not taken up. Both Kate and Steven showed peaks during Kate’s description.

Extract 7, case 4 (13:29-13:46)

Kate: -- ((emotionally moved)) you haven’t read messages that you assumed that I was bashing you in some way in those messages like I may often do

Steven: mm =

Kate: = when you (Steven’s peak) turn- I get angry you turn that phone off (.) then I get pissed of and the I like bla- then I become really nasty I blame (Kate’s peak) (.) and- and like bash you about your behavior

The Proportions of SCR Peaks During the Discussion Themes

We also calculated the proportions of SCR peaks during each of the discussion themes (see Table 4). Overall, the discussion themes varied across cases with some themes present only in individual cases. However, the most common themes across cases were the consequences of IPV (cases 1, 2 and 4), explanations for IPV (cases 1 and 2), descriptions of IPV (cases 1 and 3), and monitoring IPV (cases 1 and 3). The other discussion themes were present only in individual cases, and also contained only 1–2 peaks per theme.

When examining the proportions of SCR peaks of all the participants combined, most of them occurred during discussion about the consequences of IPV, with the therapists showing more peaks than the clients. Moreover, the therapists showed more peaks than the clients in all the subthemes of this main theme: for example, only the therapists showed peaks when the fear of violence was discussed. The second largest proportion of peaks occurred during explanations for IPV, with the therapists again showing more peaks than the clients. The third largest proportion of peaks occurred during descriptions of IPV, with the clients showing more peaks than the therapists. The fourth largest proportion of peaks occurred when the therapists monitored the IPV. In the subtheme of monitoring specific violent situations only the therapists showed peaks, however, when this concerned the perpetrator’s general violent behavior, most of the peaks were displayed by the perpetrators. The victims, in turn, showed no peaks when the therapists monitored the IPV. Among these commonly occurring discussion themes, both victims and perpetrators showed their highest proportions of peaks during descriptions of IPV, while for the therapists, this was found during talk about the consequences of IPV. Overall, peaks featured substantially less in the other four themes, accounting for 9.52% of the total.

Discussion

The aim of our study was to examine how much discussion of IPV takes place in couple therapy when IPV is the main purpose of the sessions, what the participants say about it and how, and changes in the EDA of the participants during talk about IPV. First, we found that IPV was discussed relatively little in the couple therapy sessions for IPV. It should be noted that all the present couples had been dealing with IPV earlier in the crisis center; however, it may also be that the clients, particularly perpetrators, were simply reluctant to talk about IPV. In a stimulated recall interview, the perpetrator in case 1, William, stated IPV was not something he would have wanted to talk about and doing so made him feel uncomfortable (Kalliomäki 2015). Feelings of shame prevents perpetrators from talking about IPV and strengthens their desire to cover it up (Husso 2003), which may be one reason why the perpetrators studied here appeared reluctant to spontaneously express their thoughts.

It has been argued that victims may be unwilling to talk about IPV for fear of violence (Kaufman 1992; Vall et al. 2017). On the other hand, Stith et al. (2011) suggest that most couples do not think that discussing IPV will lead to violent acts by their partner. This finding supports our result, which showed that victims were both able and willing to talk about IPV in therapy; expressing their views spontaneously, whereas the perpetrators only spoke about IPV when directly asked about it or prompted by the therapists. Our results also showed that IPV was mainly discussed from the victim’s perspective and thus do not support the suggestion that victims’ views are not discussed or taken into account in couple therapy (Husso 2003; Karakurt et al. 2013). The therapists showed their interest in hearing more about IPV from the victims by asking specific questions and reflecting on their speech.

While the therapists took an active part in the discussion, we noted that IPV was not always discussed, even when a client mentioned it. The victim in case 4, Kate, described her use of psychological violence towards her partner, but the therapists did not react to this, and the issue was not taken up. Therapists do not always make determined efforts to evaluate whether abuse has taken place between couples, possibly because they may be unprepared to deal with IPV (Stith et al. 2011). It may be difficult for therapists to acknowledge a situation where a woman reports using psychological violence (Kaufman 1992) or violence of any kind. There is also evidence that family therapists minimize reports of violence or deny its existence (Kaufman 1992). Therapists may also hesitate to address gender and power issues as they tend to approach violence and power from the perspective of values or ethics, and may not see its clinical relevance (Knudson-Martin 2013). However, power imbalances have many destructive consequences on intimate relationships.

Descriptions of, Explanations for and Consequences of IPV

The couples’ descriptions of IPV, explanations for IPV and views on the consequences of IPV were rather consistent with each other. This may be because all four couples had discussed their relationship and IPV with a professional helper before the present therapy sessions. Like Vall et al. (2017), we also found that spouses’ views on violence, particularly psychological violence, were not congruent. In case 3, John seemed to downplay his jealousy and use of violence by reacting strongly, both verbally by denying these and physiologically by showing SCR peaks when Lisa, the victim, talked about his violence. It has been found previously that violently acting men have either denied their violence or made light of it (Dobash et al. 2000; Husso 2003; Kaufman 1992).

The explanations for IPV were very diverse, including, for example, the perpetrator’s short temper and use of alcohol, disappointments in the relationship, and the victim viewing the violent situation as an accident. Although in all four cases it was the victims and the therapists who mostly offered explanations for the IPV, the perpetrators did not challenge these. For violent men, reflecting on violence and the reasons behind it seems to be difficult. In case 3, John, the perpetrator, minimized his violence and stated that he had been violent because of drink. In earlier studies, drinking has also typically been given as an explanation by both perpetrators and victims (Dobash et al. 2000; Husso 2003).

Consistent with earlier findings (Dobash et al. 2000; Husso 2003), a feeling of fear was one of the consequences of IPV most discussed by the present couples, and in the opinion of the women victims also often the hardest consequence of violence (Husso 2003). However, unlike earlier studies (Dobash et al. 2000; Husso 2003), we found that the perpetrators mostly expressed understanding their partners’ experiences and feelings related to IPV. However Lechtenberg et al. (2015) found that both male and female participants in couple therapy for IPV appreciative of the feeling safety created by the therapists in the session and it carried this home with them after the session was over.

SCRs When Discussing IPV

SCR peaks occurred as much when discussing IPV as when discussing other topics. The overall proportions of the peaks in the IPV extracts of all the peaks in the therapy session were rather small, and no difference in SCR means between victims, perpetrators or therapists was found. Thus, it seemed that the fight-or-flight response was not strongly activated during the talk about IPV. However, participants’ differed in the frequency of SCR peaks, the therapists showing more peaks than the clients. During the time spent on the consequences subthemes, the therapists showed more peaks, while during talk about the fear of violence peaks were only observed in the therapists. It might be that the clients had become more accustomed to speaking about IPV, as the couples had talked about it before the therapy started, whereas for the therapists it was ground that had not yet been covered. Stimulus novelty has been found to be related to increased EDA (Bradley 2009). The therapists may also have observed the situation more carefully and thus been more attentive on account of the possible threat of later IPV for the victims. Observing threat cues has been found to be related to increased EDA (Löw et al. 2008; Wessel and Merckelbach 1998; Wiemer et al. 2013). Moreover, it has been observed that IPV is a difficult subject for therapists to deal with (Karakurt et al. 2013; Kaufman 1992), a factor that may have been reflected in the therapists’ SCRs. Notable, the highest proportion of peaks for both victims and perpetrators occurred during descriptions of IPV. According to Husso (2003), the act of describing oneself to others as a target of violence may not only relieve but also cause the victim to feel hurt and afraid, and also induce negative feelings among listeners. This may also lead a perpetrator who is present to feel shame (Husso 2003). These reactions may be reflected in the SCRs of both parties.

It was also notable that one participant, the perpetrator in case 2, showed no peaks at all. Two different types of perpetrator have been identified (Babcock et al. 2005; Gottman et al. 1995; Romero-Martínez et al. 2013), of which type 1 is characterized by autonomic underarousal. The case 2 perpetrator, Susan, could excemplify the type I category. Susan’s experiences of violent treatment by her mother as a child and as a youngster may also have impacted on her SCR pattern. It has been found that high exposure to stressful life events is related to a hyporesponsive pattern of EDA, manifested as lower EDA, compared to moderate exposure, manifested as increased EDA (Clements and Turpin 2000).

Overall, little variance was observed in the proportions of peaks across the participants, and the proportions of the peaks showed no clear association with the amount of talk about IPV. The victims actively expressed their views and feelings, whereas perpetrators were more passive. It has been observed that active expression of emotions is related to greater EDA response stability, whereas suppression of emotions is associated with greater instability (Crider 2008). EDA is also considered a sensitive marker of personal significant events related to emotions, novelty and attention (Sequeira et al. 2009), and thus individual differences in how participants experience dealing with IPV may be reflected in their SCRs. Increased EDA has been found to be related to both negative and positive emotions (Kreibig 2010; Levenson et al. 1990), the emotional significance of stimulus and attention (Bradley 2009; Löw et al. 2008; Wessel and Merckelbach 1998; Wiemer et al. 2013), stress (Setz et al. 2010; Reinhardt et al. 2012) and stressful life events (Clements and Turpin 2000; Najström and Jansson 2007).

Limitations of the Study

Our study was based on a small sample (four couples, 11 extracts), a fact that must be borne in mind when evaluating the results. Moreover, the criterion for selecting the extracts was explicit discussions of IPV, and thus extracts featuring more implicit discussions of the topic were excluded. The couples, for example, discussed rows that may have included IPV, but if so, this was not mentioned. It must also be noted that the measurement sessions were the second sessions, which may have impacted the SCRs and the extent to which IPV was discussed. The fact that all the couples had dealt with IPV with a professional before the therapy sessions may have accustomed them to talking about IPV and so affected their talk and their SCRs. A limitation of our EDA analysis was that the amplitude of the SCR peaks was not examined, as doing so would have been informative about the strength of these responses.

Although the sample size was small, it enabled more detailed qualitative analysis of the IPV-related talk. We were able to examine precisely what themes emerged during the IPV talk and how the participants took part in it. Combining the SCRs with qualitative data about the IPV talk was also a strength of our study, as it yield novel information on how the participants in the couple therapy context reacted physiologically when dealing with IPV.

In the future, the relation between IPV discussions and EDA, among other physiological responses, needs to be studied with larger sample sizes. Although EDA is considered an important feature in the study of emotions, to gain a more fine-grained understanding ANS and other physiological responses need to be examined concurrently with EDA (Levenson 2014). Including stimulated recall interviews with all the participants in the IPV discussions would give more detailed information on how they experience discussing IPV and enable more precise interpretation of physiological responses while possibly also helping to explain individual differences in these. Physiological data could also be tapped during an ongoing therapy process. In their case study, Marci and Riess (2005) noted that examining the client’s EDA during therapy was advantageous for the therapy process. Both client and therapist reported gaining new insights into the client’s emotional states, while the client also felt that her feelings were validated because the EDA analysis made them explicit.

Conclusions and Clinical Implications

Couple therapy for intimate partner violence is a possible approach if the treatment is designed specifically for IPV and the participants are carefully screened. In couple therapy, the victims’ perspective on IPV can be foregrounded if therapists are active in asking about it. Therapists’ activity in interaction is an important strategy in seeking to end to the escalation process and can be done without affecting the therapeutic alliance (Vall et al. 2016). However, it might be difficult for therapists to acknowledge women as perpetrators. It is also typical of perpetrators to minimize or invalidate victim’s experiences and views of violent events. In such cases, therapists are required to be active and enable victims’ voices to be heard. In this study, the participants showed individual differences in their emotional reactions when dealing with the topic of IPV, a finding which could assist the therapy process. Overall, combining the present physiological data with the other information obtained on IPV-related talk in couple therapy yielded new understanding on how talking about IPV was experienced by the different participants that may be of value in clinical practice. These results support therapist-directed programs in which ongoing monitoring is the basis for determining whether conjoint therapy can proceed safely while seeking to develop a healthy, power and gender equal, relationship (e.g. Stith et al. 2012; Knudson-Martin 2013). Family therapy training programs require more instruction on how to deal with issues of domestic violence. Training and supervision should provide opportunities to recognize therapists’ personal values and beliefs and how these are brought into the therapeutic relationship. Therapists’ family of origin, clinical background and key life events or relationships play a significant role in shaping therapist’ belief systems and way of working with cases of partner abuse (Brosi and Carolan 2006).

References

Andreassi, J. L. (2007). Psychophysiology. Human behavior and physiological response (5th edn.). Mahwah (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates (LEA).

Babcock, J. C., Green, C. E., Webb, S. A., & Yerington, T. P. (2005). Psychophysiological profiles of batterers. Autonomic emotional reactivity as it predicts the antisocial spectrum of behavior among intimate partner abusers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114(3), 444–455. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.114.3.444.

Benedek, M., & Kaernbach, C. (2010). A continuous measure of phasic electrodermal activity. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 190, 80–91. doi:10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.04.028.

Bradley, M. M. (2009). Natural selective attention: Orienting and emotion. Psychophysiology, 46(1), 1–11. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00702.x.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Brehm, J. W. (1999). The intensity of emotion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(1), 2–22. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0301_1.

Brosi, M. W., & Carolan, M. T. (2006). Therapist response to clients’ partner abuse: Implications for training and development of marriage and family therapists. Contemporary Family Therapy, 28(1), 111–130. doi:10.1007/s10591-006-9698-z.

Clements, K., & Turpin, G. (2000). Life event exposure, physiological reactivity, and psychological strain. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 23(1), 73–94. doi:10.1023/A:1005472320986.

Crider, A. (2008). Personality and electrodermal response lability: An interpretation. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 33(3), 141–148. doi:10.1007/s10484-008-9057-y.

Dobash, R. E., Dobash, R. P., Cavanagh, K., & Lewis, R. (2000). Changing violent men. Thousands Oaks (Calif.): Sage.

Fredrikson, M., Furmark, T., Olsson, M. T., Fischer, H., Andersson, J., & Långström, B. (1998). Functional neuroanatomical correlates of electrodermal activity—A positron emission tomographic study. Psychophysiology, 35(2), 179185. doi:10.1017/S0048577298001796.

Fuchs, T., & Koch, S. C. (2014). Embodied affectivity. On moving and being moved. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1–12. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00508.

Gottman, J. M., Jacobson, N. S., Rushe, R. H., & Shortt, J. W. (1995). The relationship between heart rate reactivity, emotionally aggressive behavior, and general violence in batterers. Journal of Family Psychology, 9(3), 227–248. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.9.3.227.

Hammock, G. S., Richardson, D. S., Lamm, K. B., Taylor, E., & Verlaque, L. (2017). The effect of gender of perpetrator and victim on perceptions of psychological and physical intimate partner aggression. Journal of Family Violence, 32, 357–365. doi:10.1007/s10896-016-9850-y.

Holma, J., Partanen, T., Wahlström, J., Laitila, A., & Seikkula, J. (2006) Narratives and discourses in groups for male batterers. In M. Lipshitz (Ed.), Domestic Violence and its reveberations (pp. 59–83). New York: Nova Science Publishers.

Hot, P., Leconte, P., & Sequeira, H. (2005). Diurnal autonomic variations and emotional reactivity. Biological Psychology, 69(3), 261–270. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.08.005.

Hugdahl, K. (1995). Psychophysiology. The mind-body perspective. Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard University Press.

Husso (2003). Parisuhdeväkivalta. Lyötyjen aika ja tila. Tampere: Vastapaino.

James, W. (1894). Discussion: The physical basis of emotion. Psychological Review, 1(5), 516–529. doi:10.1037/h0065078.

Kalliomäki, K. (2015). Millaisia muutoksia väkivallan tekijän hengitystiheydessä ja ihon sähkönjohtavuudessa tapahtuu pariterapiassa, kun uhri puhuu väkivaltatapahtumasta. A bachelor’s thesis. University of Jyväskylä, Department of Psychology, Jyväskylä.

Karakurt, G., Dial, S., Korkow, H., Mansfield, T., & Banford, A. (2013). Experiences of marriage and family therapists working with intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 24(1), 1–16. doi:10.1080/08975353.2013.762864.

Kaufman, G. (1992). The mysterious disappearance of battered women in family therapists’ offices. Male privilege colluding with male violence. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 18(3), 233–243. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.1992.tb00936.x.

Knudson-Martin, C. (2013). Why power matters: Creating a foundation of mutual support in couple relationships. Family Process, 52(1), 5–18. doi:10.1111/famp.12011.

Kreibig, S. D. (2010). Autonomic nervous system activity in emotion—A review. Biological Psychology, 84(3), 394–421. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.03.010.

Lechtenberg, M., Stith, S., Horst, K., Mendez, M., Minner, J., Dominguez, M., et al. (2015). Gender differences in experiences with couples treatment for IPV. Contemporary Family Therapy, 37(2), 89–100. doi:10.1007/s10591-015-9328-8.

Levenson, R. W. (2014). The autonomic nervous system and emotion. Emotion Review, 6(2), 100–112. doi:10.1177/1754073913512003.

Levenson, R. W., Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1990). Voluntary facial action generates emotion-specific autonomic nervous system activity. Psychophysiology, 27(4), 363–384. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.1990.tb02330.x.

Löw, A., Lang, P. J., Smith, J. C., & Bradley, M. M. (2008). Both predator and prey: Emotional arousal in threat and reward. Psychological Science, 19(9), 865–873. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02170.x.

Marci, C., & Riess, H. (2005). The clinical relevance of psychophysiology: Support for the psychobiology of empathy and psychodynamic process. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 59(3), 213–226.

McCollum, E. E., & Stith, S. M. (2008). Couples treatment for interpersonal violence: A review of outcome research literature and current clinical practices. Violence and Victims, 23(2), 187–201. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.23.2.187.

Najström, M., & Jansson, B. (2007). Skin conductance responses as predictor of emotional responses to stressful life events. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(10), 2456–2463. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2007.03.001.

Päivinen, H., Holma, J., Karvonen, A., Kykyri, V. -L., Tsatsishvili, V., Kaartinen, J., …, & Seikkula, J. (2016a). Affective arousal during blaming in couple therapy : Combining analyses of verbal discourse and physiological responses in two case studies. Contemporary Family Therapy, 38(4), 373–384. doi:10.1007/s10591-016-9393-7.

Päivinen, H., Vall, B., & Holma, J. (2016b). Research on facilitating successful treatment processes in perpetrator programs. In M. Ortiz (Ed.), Domestic violence: Prevalence, risk factors and perspectives (pp. 163–187). Nova Science Publishers.

Reinhardt, T., Schmahl, C., Wüst, S., & Bohus, M. (2012). Salivary cortisol, heart rate, electrodermal activity and subjective stress responses to the Mannheim Multicomponent Stress Test (MMST). Psychiatry Research, 198(1), 106–111. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2011.12.009.

Romero-Martínez, A., Lila, M., Williams, R. K., González-Bono, E., & Moya-Albiol, L. (2013). Skin conductance rises in preparation and recovery to psychosocial stress and its relationship with impulsivity and testosterone in intimate partner violence perpetrators. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 90(3), 329–333. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.10.003.

Seikkula, J., Karvonen, A., Kykyri, V. L., Kaartinen, J., & Penttonen, M. (2015). The embodied attunement of therapists and a couple within dialogical psychotherapy. An introduction to the relational mind research project. Family Process, 54(4), 703–715. doi:10.1111/famp.12152.

Sequeira, H., Hot, P., Silvert, L., & Delplanque, S. (2009). Electrical autonomic correlates of emotion. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 71(1), 50–56. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.07.009.

Setz, C., Arnrich, B., Schumm, J., La Marca, R., Tröster, G., & Ehlert, U. (2010). Discriminating stress from cognitive load using a wearable EDA device. IEEE Transactions on Information Technology in Biomedicine, 14(2), 410–417. doi:10.1109/TITB.2009.2036164.

Stith, S. M., McCollum, E. E., Amanor-Boadu, Y., & Smith, D. (2012). Systemic perspectives on intimate partner violence treatment. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 38(1), 220–240. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00245.x.

Stith, S. M., McCollum, E. E., & Rosen, K. H. (2011). Couples therapy for domestic violence. Finding safe solutions (1st edn.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Stith, S. M., Rosen, K. H., & McCollum, E. E. (2003). Effectiveness of couples treatment for spouse abuse. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 29(3), 407–426. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.2003.tb01215.x.

Vall, B., Päivinen, H., & Holma, J. (2017). Results of the Jyväskylä research project on couple therapy for intimate partner violence: Topics and strategies in successful therapy processes. Journal of Family Therapy. doi:10.1111/1467-6427.12142.

Vall, B., Seikkula, J., Laitila, A., Holma, J., & Botella, L. (2014). Increasing responsibility, safety, and trust through a dialogical approach. A case study in couple therapy for psychological abusive behavior. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 25(4), 275–299. doi:10.1080/08975353.2014.977672.

Vall, B., Seikkula, J., Laitila, A., & Holma, J. (2016). Dominance and dialogue in couple therapy for psychological intimate partner violence. Contemporary Family Therapy, 38(2), 223–232. doi:10.1007/s10591-015-9367-1.

Wessel, I., & Merckelbach, H. (1998). Memory for threat-relevant and threat-irrelevant cues in spider phobics. Cognition and Emotion, 12(1), 93–104. doi:10.1080/026999398379790.

Wiemer, J., Gerdes, A. B. M., & Pauli, P. (2013). The effects of an unexpected spider stimulus on skin conductance responses and eye movements: An inattentional blindness study. Psychological Research Psychologische Forschung, 77(2), 155–166. doi:10.1007/s00426-011-0407-7.

Acknowledgements

All authors studied or worked in University of Jyvaskyla, Department of Psychology or Department of Mathematical Information Technology, Finland. The research was funded by the Academy of Finland, Human Mind Programme 2013–2016 (Decision No.: 265492).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Paananen, K., Vaununmaa, R., Holma, J. et al. Electrodermal Activity in Couple Therapy for Intimate Partner Violence. Contemp Fam Ther 40, 138–152 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-017-9442-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-017-9442-x