Abstract

Despite families providing considerable care at end of life, there are substantial gaps in the provision of supportive care. A qualitative interview study was conducted with 17 caregivers of people supported by an adult hospice to explore the support needs of families. Family members readily identified the ways in which the diagnosis of a life-limiting illness impacted on them and the family as a whole, not just the patient. Implications for practice demonstrate the need to intervene at a family and relational level prior to bereavement, in order to mitigate complicated grief for the surviving family members. Such an approach offers a fruitful prospective alternative to supporting caregivers post-bereavement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Many life-threatening conditions, such as cancer, Parkinson’s disease and dementia are more prevalent in older adults. Consequently with an ever aging population, the incidence of these conditions is projected to increase considerably. Care for people at the end of life is often delivered at home, meaning that family members share closely in the experience. Indeed, healthcare policy increasingly recognises and formalises the role of family members in providing informal, unpaid care and support. Consequently, death, dying and bereavement are not confined to hospitals and hospices but are increasingly part of family life. This study sought to examine the impact of palliative care on family members, adopting a systemic approach to analysing and interpreting the accounts of informal caregivers.

Background

The impact on family members of people receiving palliative care has been well documented; for example, more than three-quarters (76 %) of people looking after an ill, frail or disabled relative do not feel as though they have a life outside of their caring role (Help the hospices 2010).

To date, limited research has explored the nature and course of changes in family relationships during the palliative care phase. Indeed, research has tended to focus on spouses (Bakas et al. 2001), particularly partners of women with breast cancer (Thomas and Morris 2002), daughters (Wellisch et al. 1992) and siblings of children with cancer (Madan-Swain et al. 1993). Such work has tended towards quantifying relationships (Persson et al. 2008; Wennman-Larsen et al. 2009), focusing on distress and describing bereavement (Grassi 2007).

Such studies tended to examine the impact of palliative care on family members from a quantitative and individualistic paradigm (Payne et al. 1999; Boerner and Mock 2011; Aoun et al. 2010; Janssen et al. 2012). That is, studies purporting to explore the impact on family members have treated people individually, seeing palliative care as impacting on individuals rather than taking the relationship as the unit of analysis. This individualistic approach is mirrored in policy (with its focus on unpaid caregivers), but sits at odds with viewing relatives as part of the whole family system. This individualistic approach presents a clear limitation, since this precludes consideration of the complex relational context in which palliative care is delivered.

There has been, however, an increasing groundswell of work marrying medical research and systemic/family supportive care in palliative services (Mehta et al. 2009; Ballard-Reisch and Letner 2003). Work has included prevalence studies of relating styles in families receiving palliative care, mapping out patterns of psychological morbidity (such as conflict, poor cohesion and limited expressiveness) (Kissane et al. 1994) and has led to the development of systemic interventions (Kissane et al. 2003).

This study sought to complement the quantitative studies that utilise psychometrics to establish impact on relatives, to examine the qualitative accounts of family members. The study addresses the core research question: What are the support needs of caregivers when someone is receiving palliative care.

Methods

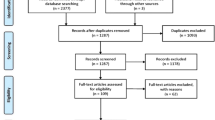

This study adopted a qualitative design wherein we undertook a series of semi-structured interview using open-ended questions.

Sampling and Recruitment

Participants were identified by using a systematic sampling technique. The caseload of Community Clinical Nurse Specialists at an adult hospice was identified, and every fifth name was selected. Clinical advice was taken regarding whether an invitation to the person’s relative to invite them to participate was appropriate, in order to ensure that people who were recently bereaved were not approached, and only relatives of out-patients were included. A final sample size of 17 relatives was achieved. A sample of 30 was the initial intention to allow for a broader cross-section of the hospice population; however despite not reaching this target the 17 interviews achieved allows for considerable depth analysis, provided sufficient data to reach saturation, and exceeded the minimum data-set proposed by other researchers applying qualitative methods (Guest et al. 2006). Participants were all relatives of the hospice user, and defined themselves as informal caregivers. Table 1 indicates the characteristics of respondents, and reflects 5 interviewees (31 %) as supporting someone with a non-malignant illness, 13 interviewees (81 %) being female carers.

Procedure

In-depth qualitative interviews were conducted with these 17 relatives of hospice users. Following best practice in service user involvement (Scottish Executive 2006), interview schedules were developed based on advice from people who had experience of hospice care as relatives of someone with a terminal diagnosis. Questions were derived from their views about what prompts would elicit meaningful and useful accounts of relatives receiving palliative care and the caregivers’ support needs. The final interview topic guide focused on prompts to talk about the help and support currently provided to the caregiver by the hospice, accessibility of other supports for caregiver, what support caregivers would wish for, and anticipated benefits that additional caregiver support would result in.

Analysis

Qualitative data was analysed inductively and thematically. Transcripts were read and re-read, and organized according to themes and classifying patterns which provided order to the data set. Sub-themes were then identified and the data further classified. This thematic, data-driven analysis drew on the approach discussed by Braun and Clarke (2006) which is informed by a position of theoretical freedom and flexibility. The rigour of the analytic process was augmented by drawing on two other members of the research team in group analysis of the data corpus and team discussion around individual transcripts. Within this team context the identified themes and patterns were further theorized to draw implications about their meaning and implications on service development. The analytic team compromised two nurses (one holding a PhD in phenomenology and one holding a Master’s degree in nursing practice) both of whom have considerable palliative care experience as clinicians and educators. The team was led by a research psychologist/family therapist (holding both a Master’s degree and PhD) with 15 years of research experience in ill-health and informal caregiving. Analysis was assisted by the use of NVivo.

Ethics

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the local National Health Service’s Research Ethics Committee. All data has been anonymised and numerical identifiers are used to preserve confidentiality of participants.

Findings

The study examined the expressed support needs of caregivers whose relative was receiving palliative care. In addition to specific supports requested around nursing interventions, respite and assistive technologies, many of the participants spoke at length about their family relationships and how these had been impacted by advanced disease. Consequently, this paper focuses on the data which illuminates the disease’s impact on interpersonal relationships, and the conceptual implications for developing practice.

Participant talk about relationships was apparent throughout all the interviews, describing both the role of pre-existing relational ties which influenced the uptake of a caregiver position, and also the impact of caring on their relationship with the person with the diagnosis. Relationships often changed and shifted as the need for care intensified. Often, the need for care impacted the whole family, as the following sister describes:

It’s pretty much all-consuming really. I mean, it’s not just debilitating for her but it’s debilitating, it’s very difficult for the, for the whole family but especially the ones closely there with her. (12)

The above quotation illustrates the impact on entire family systems, and the power of relationships in determining the uptake of the role of unpaid caregiver. For several interviewees, taking on a caring role contributed to a major shift in lifestyle. The parents of one woman, for example, found themselves travelling 300 miles to look after their daughter. Another participant expressed the magnitude of responsibility on her:

Well, you just feel it’s a massive responsibility, originally I had lived abroad and I more or less came back because my mum wasn’t so well because I didn’t want to be abroad, and my own health wasn’t as good either … I’m not so able because my illnesses are getting worse. (7)

For other interviewees, the impact of the disease was informed by the age and stage of the family members. The following interviewee places the disease in the context of his retirement, and the flexibility this affords him to be with his wife, unconstrained by work commitments:

- Interviewer:

-

How your wife’s illness has affected both you and your family … what effect that has had on you?

- Interviewee:

-

Eh … it hasn’t … being retired it’s not as though is it, would have affected me in terms of any trauma or any job I had to do. (6)

For other participants however, the onset of palliative care had led to, or exacerbated, relational difficulties.

Relationship Difficulties

For many interviewees, there was a sense of a growing difficulty in relationships as a result of the multitude of changes brought on by the illness. Difficulties emerged between the person receiving palliative care and wider family members. The following quotation echoes debates that have been well documented in the care literature around the shift in roles, whereby becoming an unpaid caregiver seemed to necessitate relinquishing or at least re-negotiating their role as spouse (Henderson and Forbat 2002), as the following quotation illustrates:

At times I think that my husband just sees me as the carer, and I can’t remember what I said once but when he answered me I said, ‘Excuse me, I am your wife first and then your carer!’ (4)

Relationship difficulties were present for some people before a poor prognosis was given; the stress of a life-threatening disease seemed to trigger the end of some relationships:

She was with her partner for 14 years, they were due to get married, she took breast cancer, and he went off with someone else. (11)

There was often an impact upon wider relationships. The following quotation is from a woman who describes the impact on her marriage, in the context of caring for a son with advanced cancer:

I think that the relationship with my husband that sort of went away for a while there, so it did, but that’s coming back again. (14)

For some, the strain of caring was visible in how people related to each other. The following quotation is taken from a woman who cares for her sister with MS. The patient compares the care she receives from her sister unfavourably with that received from a paid caregiver:

[My sister] said ‘You’re not gentle, the girl [paid carer] who’d just left she’s so gentle, you’re not gentle,’ you know, and I was just like, I just, I never do it, I never and, I just went out and I just slammed the door behind me, because you know, I literally go there every morning. (12)

Interviewees also marked out how struggles in managing symptoms, such as breathlessness in COPD, led to relational tensions:

You sit and watch people gasping for breath and they can’t breathe and you are giving them a nebuliser and it’s not working, and they get ratty [short tempered] because they can’t help you and you get ratty at them and resentful for what the disease has done to this person. (4)

Other caregivers used the interview to reconstruct scenarios where they had become angry with their relative as a consequence of the pressure they were under in providing support:

I turned to mummy and I just swore at her, I said, ‘For so and so’s sake, don’t fucking get a chest infection, because I can’t take it’, and she went, ‘Well, I don’t want one and if I get one it’s not my fucking fault,’ … and I don’t want to speak to my mother like that. (7)

Some interviewees conceded that they found it hard to relinquish care, which resulted in strain in other areas of life:

I find it very difficult to leave [daughter] with anybody. (2)

Further, for some families, the aetiology of the illness was a factor which added strain to family relationships. The following quotation comes from a mother who describes a suboptimal conversation with doctors and the subsequent role of blame within the family:

At the beginning one of the doctors said that there was a chance that [my son] could have picked this up in the womb so there was, that it could have been a gene. So something, it was something to that effect anyway, so that, that was like the, the blame so it was, where the blame came out. So we had quite a few weeks where we were arguing quite heavily over that. Everybody said it, ‘You picked something up when you were carrying him, why didn’t you know?’ (14)

Support in the Context of Other Family Members

Many of the interviewees spoke of how their role as a caregiver involved far more than looking after the person with the diagnosis. Often they were drawn into supporting a range of other family members. This seemed to represent taking on the position of caregiver across the whole family. The following quotation comes from the daughter of a man with organ failure, talking about supporting her mother:

I’m there every day with my mum and I feel I’m maybe more supporting her in so far as I took the time off so that I didn’t want my mum to become like a recluse so at least if I’m there I can say to her sometime during the day for her to go out and get a break … but in turn, me doing that, I’ve become the recluse. (1)

Another participant, a woman caring for her father, highlighted her role in supporting her siblings too, and managing their reactions to their father’s declining health:

I have got three brothers and there’s times when he’s really low and they’re there and you ask them to help to do something with them and they’re standing there like maybe there’s … he [father] goes through phases where he’s maybe vomiting and [I’ll say] ‘Can you give me a hand to hold him up?’ and they’re standing and they have tears down their face and I’m standing there and I’m looking, thinking ‘For God’s sake, he’s only being sick […] Why, [laughs], why do my brothers not think like this? Why am I thinking like this? Why [laughs], can I not have a full weekend away? (1)

The interviewee marks out her very different position of responsibility to that of her brothers, and the role she sees herself as accommodating in supporting their father. Thus, while there are other family members present, they have different roles in providing care.

For other interviewees, the focus was on supporting their family by actively choosing not to involve them in active care-giving tasks. The following participant uses the first person singular (I) and plural pronouns (we) to illustrate that this is both her position, and that of others:

My family’s quite local but they’re not in this town but they’re not far away, if you know what I mean. And they’re, they’re very supportive … but I don’t want to, you know … I don’t want to play on them … We want them to enjoy their lives, we don’t want them sort of stuck. I don’t want them on my doorstep every day. They’ve got to have their own life. (2)

In a small number of instances, the wider family provided invaluable support to the main caregiver:

My brother has come from [40 miles away] once a fortnight which has been really great. My daughter who lives in [20 miles away] comes the alternate Tuesdays, Tuesdays are when my brother comes, from her work. She takes a long lunch hour to let me go shopping for food. I go out once a month to a ladies’ group and my daughter will come over and sit with her dad while I do that, so that’s fairly regular and apart from that she is very willing to come any time we ask her. (8)

Thus, while an on-going illness may result in exhausting family input, for some the length of time lived with the disease allowed for learning and reflection on the support needs of the primary unpaid caregiver.

Communication Within Families

Communication emerged as a dominant theme in participants’ talk, relating to the quality of the relationships at end of life. This included both relationships within the family, but also between family and healthcare professionals.

Within families, some participants reported dominant family scripts about communication patterns:

His upbringing is totally different to mine. His upbringing was very much that his parents didn’t discuss things, especially not in front of him. They weren’t very open towards him and he had a rather weird relationship … well, they had a weird relationship compared to my family. So, when […] he’s really miserable and has this really frightening thing in front of him, doesn’t know how to communicate, he doesn’t know how to put it into words. (4)

Families struggled to find ways of communicating with each other in a way that felt appropriate. Without support to find adaptive ways of expressing themselves, both patient and family members were restricted in their activities:

When she is out it is ‘I’ve got a pain in my tummy, I’ve got a pain in my tummy, need a toilet, need a toilet’, which is frustrating for her and frustrating for me. So the best thing is she just doesn’t go out, really. It’s frustrating because you can’t plan anything. (7)

Interviewees highlighted the ways in which family members and patients protect each other by monitoring their communication. Family members often recognised that the person with the diagnosis was holding back information, feelings and symptoms as a way of not overburdening caregivers with worry. Likewise, family members also held back from talking about prognosis as a mechanism for protecting the patient from thinking about death.

The following excerpt illustrates some of the footwork accomplished by relatives in communicating about the patient’s health status:

I guess we all play the game […] you try to hide it from one another, I think …. We all enter some sort of place where we are trying to minimise what is going on to one another, not minimise it, perhaps that’s the wrong word, but it’s not a denial thing, you know, we know he is ill. (10)

Living with a Life-Limiting Illness is a Systemic Issue

Family members readily identified the ways in which the need for palliative care impacted on them, not just the patient. The following participant spoke eloquently about this throughout her interview:

He [GP] asks the patient things … I know that he probably thinks that it’s not his job to think of the family … But it’s only once you’ve got someone who is really ill like my husband or with cancer or even in an alcoholic … that the illness affects not just the person, it affects the close friends and family to that person and unless you actually put your hand up and say, ‘I’ve had enough of this.’ (4)

Many interviewees identified that they were not being kept in mind by healthcare professionals:

Doctors tend to talk to the patient … now this is, must be a thing that has come out … I don’t know if it’s been through the … they don’t tend to talk to the carer or the partner or the person looking after them. (5)

Thus, there is a sense that the biomedical approach to palliation is inadequate, since it marginalises the other people who are impacted by the condition. A psychosocial approach is implicitly supported, whereby family members are also identified as impacted.

Many interviewees spoke of how practical support and interpersonal care for the patient had a knock-on effect on them as a caregiver; for example personal care performed by paid carers gives the informal caregivers some time to themselves. Thus, where support is available, this too has a wider systemic impact, ensuring that when the patient is receiving adequate help this takes the pressure off family members.

Finally, some interviewees were very mindful of the stressful position that the patient occupies, since they may worry about the whole family in addition to their own health:

They might say to the patient, but they’ve got to remember that the patient’s under stress. Right? They’re not only worried about themselves. They’re worried about the families and how they’re doing when they’re not there. (5)

Discussion

The data strongly indicate struggles with the implications and ramifications of life-threatening illnesses on the whole family. As the illness intensified there was a tendency to exacerbate previous tensions in relationships, while also often creating new difficulties. Although some support was available to caregivers, there was little provision which took cognisance of the wider family system. Indeed, despite the prevalence of relational struggles, support such as systemic family therapy was not available to these families, and is not routinely offered to people receiving palliative care.

Studies have helpfully demonstrated the importance of relationships; poorer family functioning and fewer social networks are related to higher rates of disease progression and rates of death (Funch and Marshall 1983; Reynolds and Kaplan 2008). Indeed, survival has been linked to marital status; studies have identified that people who are married have better outcomes than those who are single, divorced, widowed or recently separated (Sprehn et al. 2009). These results indicate that supporting family relationships from the point of diagnosis throughout the disease’s progression has important impacts, not only on quality of life for a range of family members, but also on mortality. However, support for families has tended to be focused on those with a child receiving palliative care (Ungureanu and Sandberg 2008; Tyndall et al. 2012).

As Rolland (1994, 1999) has argued, the impact on families, and consequently their support needs will alter alongside the course of the illness. Centripetal forces draw family members in toward each other, and may take place at the onset of illness or during a phase of acute exacerbation; centrifugal forces, by contrast, are those which create distance between family members, and which may occur during chronic phases of the condition.

Since illness trajectories vary widely, Murray et al. (2005) have begun to map likely courses of disease progression in cancer, frailty/dementia, and organ failure. Organ failure and frailty/dementia are described by Murray et al. as having a range of peaks and troughs of functioning across the length of the disease. Arguably, his work suggests that there may be predictable patterns of relational dynamics. To expand upon Rolland’s work, there may be the ability to anticipate when families adopt more centrifugal and centripetal patterns, and for clinicians to respond accordingly. Such disease pathways can be contrasted with the cancer trajectory which is characterised by a long period of high functioning with a rapid drop-off toward death, which might then have a less complex relational pattern in centrifugal and centripetal forces. Murray’s model appears to offer a fruitful way of examining the possibilities for tailored interventions for families receiving palliative care. Thus, while Kissane et al.’s (1994) work has established that inventories such as the Family Relations Index can help with risk stratification of families, Murray et al’s disease progression profiles will help refine the timing of offering interventions.

This form of risk-stratification and tailored timing has the potential to support families who are most at risk of complicated grief. As the data presented above indicates, families manage their communication in a way that often prevents them from speaking with each other about the future (which, for many, will mean coping with death, dying and bereavement). The avoidance of talking about and preparing for death and dying may lead to significant problems in bereavement, specifically risk of complicated grief. Indeed, in a cross-sectional pilot study Brintzenhofeszoc et al. (2001) identified significant relationships between the level of family functioning, psychological distress and grief reaction. Further evidence indicates that families with caregiving responsibilities (Guldin et al. 2011) and those with multiple stressors at end of life might also be at risk for increased complicated grief reactions (Tomarken et al. 2008). The findings from our study are timely in the context of the forthcoming fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, where complicated grief is presented as a newly defined diagnostic category (Shear et al. 2011).

Our study clearly indicates that even those people supported by specialist palliative care services continue to struggle with managing their relationships within the family. The consequences for complicated grief may therefore be considerably more profound for those without such support. Intervening at a family and relational level prior to bereavement has the potential to mitigate complicated grief for the surviving family members, and offers a fruitful prospective alternative to supporting caregivers post-bereavement. Mapping the timing of a family-based intervention against the condition’s trajectory can mean offering support when family resources are highest, and disease burden is at its lowest.

As noted by Tyndall et al. (2012), there is considerable scope for developing medical family therapy as a sub-speciality of the discipline. Further empirical evidence about the efficacy of interventions and the experience of families at end of life will help to refine the nature of the services which are required. Indeed, trialling a risk-stratified and trajectory informed intervention may offer considerable evidence for how we support families in palliative care.

Study Limitations

Despite three rounds of recruitment to the study, the response rates were low. This may have resulted in an unrepresentative sample being achieved, despite the systematic approach to sampling undertaken. Thus, while data saturation has been achieved, and minimum numbers for qualitative analysis was reached (Guest et al. 2006), the opt-in system of sampling may have resulted in people with similar views taking part in the study.

The letter of invitation was addressed to ‘the relative of’, which left the decision of who would participate in the interview with the family. This sampling strategy resulted in 10 spousal caregivers (58.8 %), four parents (23.5 %), one sibling (5.8 %) and two filial caregivers (11.6 %). Though the approach of asking families to nominate the interviewee privileges their own knowledge and views on who would provide the most useful information for the study, it resulted in the recruitment of a broad range of family members. Literature focusing on caregiving, particularly in adult palliative care, has largely focused on spouses, consequently, this study’s 40.9 % recruitment of other caregivers offers complementary, and new, data. Unpicking the rationale for why an individual was identified as the appropriate person to be interviewed would have made an interesting and potentially illuminating addition to the data corpus.

References

Aoun, S., McConigley, R., Abernethy, A., & Currow, D. C. (2010). Caregivers of people with neurodegenerative diseases: Profile and unmet needs from a population-based survey in South Australia. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 13, 653–661.

Bakas, T., Lewis, R. R., & Parsons, J. E. (2001). Caregiving tasks among family caregivers of patients with lung cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 28, 847–854.

Ballard-Reisch, D. S., & Letner, J. A. (2003). Centering families in cancer communication research: Acknowledging the impact of support, culture and process on client/provider communication in cancer management. Patient Education and Counselling, 50, 61–66.

Boerner, K. & Mock, S. E. (2011). Impact of patient suffering on caregiver well-being: The case of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients and their caregivers. Psychology Health and Medicine [On-line].

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101.

BrintzenhofeSzoc, K., Smith, E., Zabora, R., et al. (2001). Screening to predict complicated grief in spouses of cancer patients. Cancer Practice, 7, 233–239.

Funch, D. P., & Marshall, J. (1983). The role of stress, social support and age in survival from breast cancer. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 27, 77–83.

Grassi, L. (2007). Bereavement in families with relatives dying of cancer. Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care, 1, 43–49.

Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? Field Methods, 18, 59–82.

Guldin, M. B., Vedsted, P., Zachariae, R., Olesen, F., & Jensen, A. B. (2011). Complicated grief and need for professional support in family caregivers of cancer patients in palliative care: a longitudinal cohort study. Supportive Care in Cancer, eprint ahead of publishing.

Help the hospices. (2010). Hospice UK Online. Available: http://www.helpthehospices.org.uk/media-centre/press-releases/carers-week/.

Henderson, J., & Forbat, L. (2002). Relationship-based social policy: Personal and policy constructions of ‘care’. Critical Social Policy, 22, 669–687.

Janssen, D. J., Spruit, M. A., Wouters, E. F., & Schols, J. M. (2012). Family caregiving in advanced chronic organ failure. Journal of the American Medical Director’s Association [e-pub ahead of print].

Kissane, D. W., Bloch, S., Burns, W. I., Patrick, J. D., Wallace, C., & MacKenzie, D. (1994). Perceptions of family functioning and cancer. Psychooncology, 3, 259–269.

Kissane, D. W., McKenzie, M., McKenzie, D. P., Forbes, A., O’Neill, I., & Bloch, S. (2003). Psychosocial morbidity associated with patterns of family functioning in palliative care: Baseline data from the family focused grief therapy controlled trial. Palliative Medicine, 17, 527–537.

Madan-Swain, A., Sexson, S. B., Brown, R. T., & Ragab, A. (1993). Family adaptation and coping among siblings of cancer patients, their brothers and sisters, and nonclinical controls. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 21, 60–70.

Mehta, A., Cohen, S. R., & Chan, L. S. (2009). Palliative care: A need for a family systems approach. Palliative and Supportive Care, 7, 235–243.

Payne, S., Smith, P., & Dean, P. (1999). Identifying the concerns of informal carers in palliative care. Palliative Medicine, 13, 37–44.

Persson, C., Östlund, U., Wengström, Y., & Gustavsson, P. (2008). Health related quality of life in significant others of patients dying from lung cancer. Palliative Medicine, 22, 239–247.

Reynolds, P. & Kaplan, G. (2008). Social connections and risk for cancer: Prospective evidence from the Alameda County Study. Behavioral Medicine, Fall, 16, 101–110.

Rolland, J. S. (1994). Families, illness and disability: An integrative treatment model. New York: Basic Books.

Rolland, J. S. (1999). Parental illness and disability: A family systems framework. Journal of Family Therapy, 21, 242–266.

Scottish Executive. (2006). Research Governance Framework for Health and Community Care http://www.research.luht.scot.nhs.uk/ResearchGovernance/ResearchGovernanceFramework.pdf: Scottish Executive.

Shear, M. L., Simon, N., Wall, M., Zisook, S., Neimeyer, R., Duan, N., et al. (2011). Complicated grief and related bereavement issues for DSM-5. Depression and Anxiety, 28, 103–117.

Sprehn, G. C., Chambers, J. E., Syakin, A. J., Konski, A., & Johnstone, A. S. (2009). Decreased cancer survival in individuals separated at time of diagnosis. Cancer, 115, 5108–5116.

Thomas, C., & Morris, S. M. (2002). Informal carers in cancer contexts. European Journal of Cancer Care, 11, 178–182.

Tomarken, A., Holland, J., Schachter, S., et al. (2008). Factors of complicated grief pre-death in caregivers of cancer patients. Psychooncology, 17, 105–111.

Tyndall, L. E., Hodgson, J. L., & Lamson, A. L. (2012). Medical family therapy: A theoretical and empirical review. Contemporary Family Therapy [online first], Doi 10.1007/s10591-012-9183-9.

Ungureanu, I., & Sandberg, J. G. (2008). Caring for dying children and their families: MFTs working at the gates of the Elysian fields. Contemporary Family Therapy, 30, 75–91.

Wellisch, D. K., Gritz, E. R., Schain, W., Wang, H., & Siau, J. (1992). Psychological functioning of daughters of breast cancer patients. Part II: Characterizing the distressed daughter of the breast cancer patient. Psychosomatics, 33, 171–179.

Wennman-Larsen, A., Persson, C., Ostlund, U., Wengstrom, Y., & Gustavsoon, J. P. (2009). Development in quality of relationship between the significant other and the lung cancer patient as perceived by the significant other. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 12, 430–435.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Caroline McDermid and Gail Allan who helped conduct interviews, and Marjory Mackay for her help with the recruitment. Thanks also to Elaine Cameron and service user advisor Linda Foster who helped devise the interview schedule.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Forbat, L., McManus, E. & Haraldsdottir, E. Clinical Implications for Supporting Caregivers at the End-of-Life: Findings and from a Qualitative Study. Contemp Fam Ther 34, 282–292 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-012-9194-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-012-9194-6