Abstract

A large body of research has been devoted to the study of family-of-origin (FOO) experience influences on future relationship outcomes and processes. In addition, substantial information exists regarding the role relationship attributions play in connection with relationship quality and stability. Yet, limited information has been forthcoming regarding how the FOO experience has an influence on attributions made in romantic relationships. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was employed to assess the impact of the FOO experience on attributions made about one’s own communication and personality variables, as well as the communication and personality variables of one’s partner from a sample of individuals who had completed the RELATionship Evaluation (N = 6,649). Results show evidence of a relationship between the FOO experience and the attributions made about oneself and one’s partner. Results were particularly pronounced for the communication variables. Gender differences also were found. The utility of study findings for couple and family researchers and practitioners is discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A great deal of research has been devoted to the family-of-origin (FOO) experience, including examination of FOO influences on a number of different areas of development and functioning. Of this large body of research, a considerable amount of literature includes reports of various effects of FOO factors on romantic relationships, including both relationship outcomes and relationship processes.

Family-of-Origin Influences on Future Relationship Outcomes

In the area of relationship outcomes, a number of studies addressing the effects of parental divorce on children’s marriages have been documented. Some of the findings have shown associations between parental divorce and an increase in the risk of psychological, social, and relational difficulties later in life (Amato 2010; Amato and Booth 2001). The longitudinal format utilized by Amato and colleagues examined the relation of parental marital discord with marital discord and marital harmony in children’s future marriages. These findings show that reports of parental discord with participants in 1980 predicted offspring’s reports of marital discord and marital harmony in 1992 (Amato and Booth 2001).

Further results of these longitudinal investigations have shown influences not only on the children of the divorcing couple, but also on two subsequent generations (grandchildren) (Amato and Cheadle 2005). Influences experienced down to the grandchildren generation have included lower educational attainment and greater marital discord. These results suggest that parents’ marital quality has a causal impact on offspring’s marital quality and even grandchildren’s marital quality (Amato and Cheadle).

Additionally, Amato and colleagues found a number of different areas in which parental divorce was connected with relationship outcomes in children. Of these findings, associations indicate that children whose parents divorce are more likely to see their own marriages end in divorce, and that these children are also more likely to report relationship problems, conflict, perceived instability, and lack of trust in their own relationships. This body of research also indicates that problems in the parents’ marriage involving jealousy, anger, overly critical behavior, poor spousal communication, and a tendency for one spouse to dominate the other all appear to have negative effects on offspring’s future marriages (Amato 1996, 2010; Amato and Booth 1991, 2001; Amato and Cheadle 2005).

In addition, several studies have shown associations between parental divorce and other FOO factors and children’s future marital quality and marital satisfaction. Findings indicate that wives from divorced family backgrounds report elevated levels of psychological and physical aggression as newlyweds, and husbands who have reported negativity in the FOO have shown higher levels of observed dyadic anger and contempt in newlywed marital interactions, increasing the likelihood of adverse marital outcomes (Story et al. 2004). Additional findings show an influence of parental divorce on mate selection in that children from divorced families are more likely to select high-risk partners who are also from divorced families and who are often impulsive and socially irresponsible. These high-risk partners also often have a history of antisocial behaviors such as alcohol and drug use, trouble with the law, problems in school, fighting, and an unstable job history (Hetherington 2003).

Researchers also have reported that factors related to divorce and perceived levels of FOO functioning are related to levels of current marital satisfaction. Individuals raised in alcoholic homes have reported significantly lower perceived levels of FOO functioning than those who did not report such a history (Campbell et al. 1998), and generally children whose parents’ marriage ended in divorce report lower marital happiness and feel less positive about their marriages (Glen and Kramer 1987).

FOO experience links to commitment levels in future relationships also have been demonstrated. Children with more happily married parents often report receiving messages about the significance of dedication to one’s partner and that work is required in order for relationships to last. On the other hand, children with less happily married parents have reported learning lessons about the impermanence of relationships, such as a partner choosing to stay in a relationship due to constraints, and that most relationships ultimately will collapse (Weigel et al. 2003). These researchers also noted that individuals who grew up with models of satisfying relationships (e.g., married and happy parents) were more likely to report relationship descriptions of commitment including love, partnership, and stability, while those with more stressful models of relationships (e.g., divorced and unhappy parents) were more likely to report messages about the more tenuous and hurtful side of relationships (Weigel et al.).

Family-of-Origin Influences on Future Relationship Processes

The FOO experience also has been shown to influence several areas of relationship processes. One process that has been documented is relationship maintenance, which has been linked to experiences in the FOO, especially during points of change such as the transition to parenthood (Curran et al. 2005). Results have indicated that prenatal low-levels of maintenance were predicted primarily by a dismissing attachment pattern. Also, interestingly, maintenance declines across the transition to parenthood were predicted independently for adults with preoccupied attachments and adults with memories of their parents’ marriage as low in conflict and high in parental affection and communication (Curran et al.). These findings point toward the influential nature of the manner in which close relationships are ascribed meaning through discussions and portrayals of relationships in the FOO, and how these experiences predict different levels of relationship maintenance. Findings show that when compared with secure adults, adults classified as dismissing presented the least descriptively rich information of their parents’ marriage (Curran et al.).

The transmission of communication patterns and practices from the FOO also has been documented in a number of studies. For example, children from divorced families have been found to be less likely to use effective problem solving strategies, and tend to employ more contemptuous and belligerent interactions to cope with or manage conflict (Hetherington 1999).

These family communication patterns have been documented to have different influences on males and females. Men whose partners report a higher level of conflict in their FOO have been shown to be less satisfied with new relationships, and women who come from families better skilled at expressing individual feelings and perspectives are more able to establish a shared set of ground rules in their current relationships. Conflict resolution behaviors such as the ability to respond with positive behavior given a prior negative behavior, and not to respond with negative behavior when given a prior negative behavior, also have shown connections to functioning primarily in women’s FOO (Levy et al. 1997; Wamboldt and Reiss 1989).

Researchers also have shown interest in the influences of behaviors and practices of parents on children’s future relationships. Dysfunctional rules from the FOO have been shown to negatively affect young adult dating relationships and negatively affect the specific areas of emotional, intellectual, and sexual health and satisfaction (Larson et al. 2000; Larson et al. 2001). Other researchers have highlighted the socialization practices of parents as more likely than parents’ marital interactions to affect the quality of interpersonal behaviors in early romantic relationships. Interpersonal behaviors in FOO relationships characterized as high in warmth and low in hostility have shown positive associations with the quality of early adult romantic relationships. In this case, parenting behaviors were the only significant FOO predictors of later interpersonal competence (Conger et al. 2000).

The transmission of violence from the FOO experience also has been documented as influencing future romantic relationship processes. Adults exposed to violence between parents while growing up are more likely to be physically aggressive as well as to be victimized in their own intimate relationships later in life (O’Leary and Cascardi 1998).

In addition, the influence on the relationships of both male and female children exposed to parental aggression and violence in the FOO have been examined. Halford et al. (2000) found that where the male partner had been exposed to parental aggression much more negativity in affect and behavior was exhibited in a conflict management discussion, even when the female partner had not been exposed to parental violence. Findings on female partners who had been exposed to parental aggression show increased levels of negative cognitions during problem solving interactions with their male partners (Halford et al. 2000).

These findings highlight the substantial body of literature pointing towards the connection between the FOO experience and several different areas of relationship outcomes and processes. In addition, attributions (cognitive processes in relationships) also have been widely explored by researchers. These findings offer further information exploring how attributions made in relationships influence relationship quality and functioning.

Attributions Research

Relational attributions—the perceived meaning one partner assigns to the other partner’s characteristics and behavior—have been shown to affect many aspects of intimate relationships. One of the best-studied areas is communication. Research suggests that communication is influenced by relational attributions in a variety of ways, including the interchange of positivity and negativity (Miller and Bradbury 1995), solution-oriented talk during conflict discussions (Bradbury et al. 1996; Bradbury and Fincham 1992, 1993; Johnson et al. 2001), and nonverbal behaviors (Manusov 2002).

During problem-solving discussions, maladaptive attributions made by both husbands and wives have been found to influence communication patterns, which often results in patterns of negative communication among married couples. For example, wives who make maladaptive attributions tend to be less expressive, accepting, or agreeable, and more critical in their relationships (Bradbury and Fincham 1992, 1993; Bradbury et al. 1996; Johnson et al. 2001). Even during social support discussions, husbands who formed maladaptive attributions were more likely to respond to their wives’ neutral behavior with negative behavior (Miller and Bradbury 1995). In addition, husbands’ dysfunctional beliefs have been shown to be connected with their spouses’ inclination towards reciprocating negative communication behavior (Bradbury and Fincham 1992; Bradbury and Fincham 1993; Johnson et al. 2001). Thus, it can be inferred that maladaptive attributions made by either husbands or wives affect romantic relationships in ways that hinder problem resolution and effective communication.

Pleasant and negative nonverbal behaviors also have been found to be both triggers of and reactions to “adjusted” and “maladjusted” attributions made by couples while communicating. Specifically, when partners attributed their spouses’ positive nonverbal cues as internal or purposeful, the partner provided a relationship “reward,” such as smiling and talking in a pleasant tone. On the other hand, maladjusted attributions are more closely linked to nonverbal behaviors showing that the other person does not feel good about, or want to be involved in, the interaction with his or her partner (Manusov 2002).

In association with conflict situations, relational attributions also have been found to impact the likelihood for anger and forgiveness among romantic couples (Friesen et al. 2005; Sanford 2005). Sanford (2005) established that event-dependent attributions, attributions based on the aspects of one’s current situation, are the best predictor of anger for wives, and schematic attributions, which are based on one’s overall attitude in the relationship, are the best predictor of husbands’ anger. Friesen et al. (2005) found that positive attributions and relationship quality independently predicted higher internal forgiveness, where more positive attributions made about the partner’s forgiveness were associated with greater relationship satisfaction. Thus, attribution processes in relationships may influence bouts of anger in couple interaction, as well as the propensity to forgive one’s partner.

Finally, the marital literature reveals that relational attributions have a significant influence on the satisfaction of romantic partners. Even when controlling for spousal negativity, depression, and violence, relationship attributions exert a unique and considerable influence on couples’ relationship satisfaction (Bauserman et al. 1995; Fincham et al. 1997; Karney et al. 1994; Neff and Karney 2003).

Additional research has shown how certain factors may moderate or mediate the influence of relational attributions on relationship satisfaction. Fincham et al. (2000) investigated whether associations between attributions and marital satisfaction are mediated by other relationship factors, specifically efficacy expectations regarding marital conflict. They found that efficacy expectations, or the perceiver’s belief that he or she can execute the behaviors needed to resolve the conflict, were positively related to marital satisfaction and negatively related to causal and responsibility attributions for both spouses, supporting their hypothesis that efficacy expectations mediate the relationship between attributions and marital quality. Furthermore, in a study of 352 students in a romantic relationship, Sumer and Cozzarelli (2004) reported that securely attached people reported less maladaptive attributions than those who were insecurely attached. They note that “a more positive model of self is associated with a lower level of negative attributions, which in turn contributes to a higher level of relationship satisfaction” (p. 366).

Others have noted that both a strong sense of self identity as well as strong couple closeness, or connection to one’s partner (couple identity), also have an influence on the manner in which attributions are made in romantic relationships (Acitelli et al. 1999; Cropley and Reid 2008; Sumer and Cozzarelli 2004). Cropley and Reid (2008) found that couples who reported a high degree of closeness to one another reported greater relationship satisfaction and more positive attributions regarding partner behaviors.

Thus, as noted here, a substantial amount of attention has been given to the influence of FOO experience on future romantic relationship processes and outcomes. In addition, ample amounts of study addressing how attributions made about oneself and about one’s partner have an influence on romantic relationships have yielded important information on the role of cognitions and the assigned meaning attached to behaviors in relationships. However, scant information exists joining these two topic areas: How are attributions made about oneself and one’s partner influenced by the FOO? We hypothesized that the FOO would have an influence on self and relational attributions made in romantic relationships.

Methods

Instrument and Sample

Analyses were conducted using data from the RELATionship Evaluation (RELATE; Busby et al. 2001) instrument database. The purpose of the RELATE is to examine the relationship between romantic couple partners from different potential influencing areas. The instrument contains 271 questions aimed at providing an in-depth comparison of partners’ backgrounds, beliefs, experiences, and relationship goals to assess similarities and differences and identify strength and growth areas in the couple relationship. The questions investigate multiple potential influencing factors including individual (e.g., personality), social/cultural (e.g., values), family (e.g., family of origin, family life) and couple (e.g., social interactions) factors. Previous evaluation and testing have recorded reliability and validity information for the RELATE (Busby et al. 2001). Overall, RELATE scales show reliability coefficients between .70 and .95 over analyses utilizing different samples.

From a larger sample of 24,158 respondents who completed the RELATE between 1997 and 2003, a subsample of 6,649 individuals (males and females in this sample were not coupled with one another) was stratified across race and religion to resemble national norms (based on 2004 Census data). This subsample was 41% male (n = 2,699) and 59% female (n = 3,950), 66.7% (n = 4,435) of the sample reported Caucasian ethnicity, 12.8% (n = 851) African American, 10.2% (n = 680) Latino, 3.7% (n = 248) Mixed/Biracial, 3.7% (n = 243) Asian, and 2.9% (n = 192) American Indian. Regarding education, 47% (n = 3,123) of respondents had completed some college, 6.3% (n = 418) reported having completed an Associates degree, 39.2% (n = 2611), had received a Bachelor’s degree or higher, 6.6% (n = 436) completed high school or high school equivalency, and less than 1% (n = 55) did not complete high school. Of those in the sample, 37.4% (n = 2,484) reported being in a serious or steady dating relationship, 22.5% (n = 1,493) reported being engaged, 20.2% (n = 1,341) were either casually dating or not dating at all, and 19.7% (n = 1,312) were married.

Variables and Analyses

Structural equation modeling (SEM) (via Amos 5.0) was utilized to analyze the data and evaluate relationships between variables of interest. Utilizing SEM, latent variables may be constructed given that specific items used to identify every latent variable significantly load upon that variable. The Current Impact of Family of Origin scale of the RELATE served as the primary FOO latent variable. This latent variable consisted of RELATE items designed to investigate how the perceptions of one’s FOO experience are presently affecting him or her. This three-item scale asks respondents to rate how much they agree with statements such as “There are matters from my family experience that I’m still having trouble dealing with/coming to terms with,” or “There are matters from my family experience that negatively affect my ability to form close relationships.” In keeping with our intergenerational perspective on relationship attributions, we hypothesized that respondents’ reports on the Current Impact scale would be predicted by their reports of their Parents’ Marriage.

We then selected personality and communication variables from the RELATE that have been shown to exert a significant influence on future relationship satisfaction and stability (Busby et al. 2001). For personality, respondents’ ratings of both their own and their partner’s Kindness, Flexibility, and Self-esteem were selected. For communication, respondents’ ratings of both their own and their partner’s Empathic Communication, Contempt/Defensive Communication, and Clear Communication were selected. Each of these latent variables was constructed with three to seven individual items, and all are also well-established standard scales in the RELATE instrument.

To summarize, we hypothesized that respondents’ ratings of their Parents’ Marriage would predict their ratings of the Current Impact their family experience has on them. The Current Impact ratings were then hypothesized to predict respondents’ ratings of their own and their partner’s personality (Kindness, Flexibility, Self-esteem) and communicative (Empathic, Contempt/Defensive, Clear) characteristics. Separate analyses were conducted for males and females in order to explore any potential gender differences.

Results

Measurement Model

Individual survey items’ (indicators’) associations with each latent construct or variable are included in the measurement model. This study utilized 54 survey items per gender to construct 14 latent variables. Ensuring that survey items used to construct a specific latent variable are suitably related to one another, evaluation of the measurement model is in order. One indicator is selected as the metric, is set to 1.0, and all other indicators for a particular latent variable are evaluated by this metric. In this manner, all other indicators freely “load” on their corresponding latent constructs with a path coefficient. Loadings that receive a critical ratio (CR) greater than ±1.96 are significant at the .05 level. All factors loaded significantly on their respective latent constructs within the measurement model. Results for the analyses regarding the measurement model can be seen in Table 1.

Structural Model

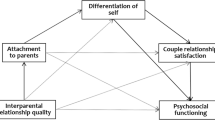

In general, a structural equation model is said to have a good fit with the data if fit indices such as the NFI, TLI, and CFI are all above .90. Furthermore, an RMSEA of less than .05 indicates good overall fit, while adequate fit can be achieved with an RMSEA of between .05 and .08 (McDonald and Ho 2002). Results for these analyses can be seen in Table 2. Also, as can be seen in Figs. 1 and 2, all paths were statistically significant (at the .05 level), and the model fit the data moderately well. A low and non-significant chi-square statistic also indicates good fit; however, the chi-square is susceptible to inflation with large sample sizes, and thus is not an appropriate indicator of fit for this particular model. The current model obtained moderate scores on fit indices (Males: NFI = 0.859, CFI = 0.876; Females: NFI = 0.861, CFI = 0.873) and adequate fit according to the RMSEA (Males = .048; Females = .048).

Overall, the lowest path coefficients in the models were .181 (CR 6.323; males’ reported impact of parents’ marriage on current family of origin impact → Male Model: Current Impact), .332 (CR 7.827; males’ reports of own flexibility → Male Model: Own Flexibility), .244 (CR 9.164; females’ reported impact of parents’ marriage on current family of origin impact → Female Model: Current Impact), and .332 (CR 9.983); females’ report of own flexibility → Female Model: Own Flexibility). All other coefficients in the two models ranged from .375 (CR 8.304) and .956 (CR 9.474).

For both male and female personality and communication variables, the paths from the Current Impact construct to their own personality constructs were the weakest in the models, but still significant, with the path between Current Impact and Own Kindness being the strongest of the three for both males and females. Paths from the Current Impact construct to the communicative constructs—both own and partner—were the strongest in both male and female models, with the strongest being those from Current Impact to Partner’s Empathic Communication (for both males and females). All of the paths from the Current Impact construct to the partner personality constructs were significant, with the strongest paths being those between Current Impact and Partner’s Kindness, for both males and females. Thus, between the analyses of both models, the FOO experience had the strongest impact on ratings of both male and female own and partner kindness in terms of personality variables, and both male and female empathic communication in terms of communication variables.

For males, the correlation between Own Empathic Communication and Partner’s Empathic Communication was strong and negative (−.146). This correlation for females was also negative but at a weaker level. Connections between Own Contempt/Defensiveness and Partner’s Contempt/Defensiveness showed strong positive correlations (Male: .905, Female: .906) in both the male and female models. Thus, the FOO experience appears to have a strong bearing on the rating of one’s own empathic communication for males, but also a reduced likelihood of seeing this same quality in one’s partner. In contrast, the FOO experience has an influence on the ratings of one’s own contemptuous/defensive communication, but also a greater likelihood of seeing this same communication style in one’s partner for both males and females.

Discussion

The results of this study expand current knowledge and broaden the methods used to study families and close relationships. Overall, the results of the structural model confirmed our hypothesis that FOO experiences contribute to the formation of relationship attributions. This general finding serves to extend our comprehension from the existing relationship literature showing indications of FOO experience influences on future relationship outcomes and processes to FOO influences on the attributions that individuals make about themselves and their partners. This suggests that FOO influences and experiences not only have an effect on the ways individuals think and behave in relationships, but also on the ways they attach meaning to their own as well as their partner’s characteristics and behavior. Additional investigatory work on how attributions are shaped will help clinicians, researchers, and educators better know how attributions impact romantic relationships.

Convergent Findings

This study yielded a number of interesting findings important to address further in future studies of relationships. Overall, the strongest paths found were those that illustrated the relationship between the FOO experience and the self and partner communication variables, suggesting that the FOO experience was a strong predictor for both self and partner communication attributions. The strength of the associations between the FOO experience and both self and partner communication variables was relatively similar in both the male and female models, but the correlations between the different communication variables differed in some ways across gender in the different models.

First, no correlation was found between females reporting a contemptuous/defensive communication state and being able to communicate clearly/empathetically. This finding indicates that females may be more able to clearly and empathically communicate regardless of whether or not they are in a hostile state. Females reported, according to the attributions that they made, that their male partners were not as able to communicate clearly when in a more contemptuous/defensive state. This suggests that females noticed that their male partner’s contempt or defensive mechanisms often overrode their ability to communicate in a clear and empathic manner.

The reports given by males were both similar to and different from those given by females. Males reported a correlation between their own ability to communicate clearly and empathically while in a contemptuous or defensive state. Males also reported no correlation between their female partner’s capability to communicate clearly when contempt and defensiveness were also present factors. This suggests that males may not see their female partner’s ability to communicate empathically and clearly as wholly unrelated to their ability to communicate in a contemptuous or defensive manner. These reports also indicate that males notice the communication skills of their female partners in their capacity to communicate effectively despite the presence of other present factors. Males noted that their partner’s ability to accomplish this feat was greater than their own. Interestingly, partners gave these reports independently of one other, in that the data was not coupled (partner with partner).

In addition, the correlation between ratings for males’ own ability to communicate empathically and ratings of partners’ empathic communication was negative. This finding indicates that male ratings of their own empathic communicative abilities may limit their ability to see this same attribute in their partner. This path coefficient for females was also negative but at a somewhat weaker level. Both male and female ratings of their own contemptuous and defensive communication styles were highly correlated with these same ratings of their partner. This suggests that ratings of one’s own contemptuous and defensive communication behaviors are strongly associated with noticing these same behaviors in the communication of one’s partner.

This set of findings suggests that not only does the FOO experience have a direct influence on attributions made of both self and partner communication style ratings, but also on how ratings of self and partner communication styles relate to one another. Interestingly, the results showed that the manner in which the FOO experience was connected with how male and female partners attribute self and partner communication skills differed.

These findings are in many ways consistent and related to the results of previous studies of FOO influences on relationships. For instance, prior results have indicated that women who experienced FOO relationships characterized by the expression of feelings are also more skilled to set relationship ground rules, as well as to find common ground in future relationships (Wamboldt and Reiss 1989). Other findings have noted that women with higher functioning FOO experiences have better overall conflict resolution skills. These women tend not to become heated when arguing, and are able to give positive responses when confronted with negative stimuli while communicating (Levy et al. 1997).

These findings suggest that a FOO experience in which it was safe to express emotion and was typified by higher levels of functionality for females lead to better communication and conflict resolution skills in future relationships. Such FOO experiences were most likely influencing the females in this study, since previous findings are consistent with our findings indicating that FOO influences on both female self reports and male partner reports indicate that females were better able to communicate clearly and empathically despite the presence of negative communicative components such as contempt.

For males, the FOO experience on shaping the self and partner communication attributions was somewhat different. Findings have noted that when relationship partners perceive positive nonverbal cues given by their spouse as intentional, the behavior that is reciprocated is more often positive as well, and “rewarded” by giving a smile or replying in an agreeable manner (Manusov 2002). The manner in which communicative behaviors (e.g., negativity) are perceived and managed in partner interaction may be shaped by FOO processes (Levy et al. 1997; Wamboldt and Reiss 1989).

The shaping effect of these processes may differ by gender. In our study, the influence of the FOO experience on the relationship between different communication styles varied in the male and female models. Males reported that their female partners were able to communicate clearly even when hostile, while females did not see the same phenomenon in their male partners. Males, even though the interaction with their partner has grown argumentative, may also attribute and recognize the clear communication skills of their partner as positive and respond accordingly. The same pattern may not be present for female attributions of their male partner’s communication skills. Thus, the FOO experience may shape the perception of the communication skills of one’s partner differently for males and females.

Overall, the results suggest a strong FOO experience connection with behaviors that have been shown to contribute positively to romantic relationships (e.g., Busby et al. 2001) in that a more positive appraisal of the FOO experience was strongly related to the attributions made of one’s own and one’s partner’s kindness attributes and empathic communication abilities in both the male and female models. Further distinction as to the specific qualities of the FOO experience that contribute to the attributions made of self and partner characteristics will shed further light on how romantic relationships are shaped by aspects of one’s family while growing up.

Divergent Findings

Our findings also show some variations from previous research results. For example, Bradbury and Fincham (1992) found that wives who had formed maladaptive attributions tended also to be less accepting and expressive, and more critical of their partner. This differs somewhat from our finding indicating that the FOO experience influence on communication styles for females showed that females were able to differentiate and regulate emotions during communication and were able to speak and express clearly even with the factors of contempt and defensiveness present. However, maladaptive attributions formed by both males and females have been noted to be connected with patterns of negative communication (Bradbury et al. 1996). Thus, the previous formation of maladaptive attributions for both husbands and wives would have some influence on relational interactions and communication. Yet, this study is unique in that very little research has focused on FOO influences on relational attributions. Thus, the findings of the current study represent new information that is difficult to compare with previous research.

Overall, the influences of the parents’ marriage on ratings of the current impact of the FOO experience showed the weakest relationships in both the male and female models, offering modest support for our hypotheses. The quality of the parents’ marriage in many ways sets the family climate for marital partners and children alike, and has been shown to have far reaching influences on offspring in later romantic relationships (Amato 1996; Amato and Booth 1997). Yet, in accordance with attachment theory ideas, the relationship the child has with each parent may be the more potent factor in influencing different aspects of future couple relationships (Bowlby 1979; Conger et al. 2000; Mikulincer et al. 2002).

Limitations

One major limitation of this study is the cross-sectional design through which only a “snapshot” of the associations is ascertained. Longitudinal designs investigating FOO experiences on future relationship attribution formation are needed. In addition, other possible factors not fully addressed in this study could have an impact on reflections about the FOO experience and, in particular, relationship attributions. For example, relationship satisfaction and closeness, the length or stage of the romantic relationship, early attachments to caregivers, interpersonal behavior patterns in the FOO, and parental divorce may have a bearing on attribution formation in couple relationships (Amato 1996; Amato and Booth 1991, 2001; Cropley and Reid 2008; Halford et al. 2000; Larson et al. 2001; Pearce and Halford 2008; Sumer and Cozzarelli 2004). These factors were not uniquely addressed in this study.

Despite the apparent limitations, this study does extend previous work on FOO influences on romantic relationships by addressing how the FOO experience influences attributions made in couple relationships. As is usually the case with a research area where much attention has not been given, this study has served to establish a connection and lay groundwork for future research. Much future investigation is needed to determine how specific factors from the FOO experience influence future relationships, assessing both the attributions that partners make of self and the relationship partner, and how these processes affect relationship quality.

Implications for Researchers

Building upon previous literature along with the findings of the current study, we suggest two implications for researchers involved in the study of relationships. First, the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) (George et al. 1985) is a valuable tool to address possible FOO influences on individuals and on relationships. The AAI can be used to examine how early attachment relationships from the FOO influence perceptions and behaviors in future relationships. Second, at times FOO influences can be neglected in the study of relationships. We encourage researchers not to overlook how FOO dynamics play out in couple relationships in terms of both relationship processes and outcomes, as well as in the formation of relationship attributions.

Implications for Practitioners

The results of this study have implications for marital/couples therapists and family life educators. The results confirmed our hypotheses that FOO experiences contribute to the attributions that individuals make about themselves and their partners, specifically about personality characteristics and communication, providing for a more comprehensive understanding of the potential impact of one’s FOO on the attributions relational partners may make about themselves and their partners.

Attending to FOO information might be crucial in the therapy process and in relationship education programs. For example, therapists may benefit from understanding that relational conflict may stem from their clients’ FOO experiences. Furthermore, family life educators need to ensure that their education programs include a substantial component that allows partners to explore their FOO experiences, anticipate potential future problems, and generate discussion about those FOO influences.

Marital/couples therapists would also do well to consider the importance of FOO influences on their clients’ romantic relationships. Therapists might place emphasis on gathering their clients’ FOO information and particularly focus on how their families-of-origin influence aspects of their current romantic relationships. Therapists can help their clients become aware of their own experiences, as well as their partners’ experiences, with their families-of-origin. By building awareness about FOO experiences, partners might be able to gain insight into their own and their partners’ relationship behaviors, which could facilitate communication and softening processes in therapy (Butler and Gardner 2003).

Therapeutic interventions could be designed to help build awareness about FOO experiences. For instance, from a Bowenian perspective one might utilize genograms to allow partners to become aware of their own and their partner’s FOO experiences and relationships. Multiple sessions would involve collecting information, discovering ways in which FOO dynamics may be influencing the couple and their relationship, presenting homework assignments to encourage further insight into each partner’s FOO, and assisting the couple to begin connecting their families-of-origin to their own relationship (Foster et al. 2002).

In addition, early childhood experiences with attachment figures have been shown to be critical in understanding later attachment style in adult romantic relationships (Feeney and Noller 1990). Consequently, insight-oriented approaches to couples therapy could provide couples with knowledge about and awareness of their own and their partner’s behavior. However, regardless of what their theoretical orientation is, therapists might find it helpful to utilize FOO information as a means to boost their clinical approach to couples and relationships.

Family life educators, and others who educate couples, could also place emphasis on gathering FOO information in their education programs. Allowing partners to explore their own and their partner’s FOO experiences often helps couples to identify potential problems in their couple relationship that may be related to these experiences. To do so, at least one session of their family life education programs might be devoted to exploring the potential influence of one’s FOO on the couple relationship. By utilizing such a focus, family life educators could develop prevention strategies to aid in restructuring harmful and longstanding interaction patterns within the couple relationship. These interventions would focus on couple communication processes, such as pursuer/distancer patterns, intentions and interpretations of partner behaviors, relationship experiences of each partner, and understanding of oneself and one’s partner.

Both marital/couples therapists and family life educators might find it extremely important to include FOO components in their sessions. In particular, therapists and educators could attend to potential FOO dynamics or issues when couples present for couples therapy or pre-marital or marital education programs. One way would be to include an evaluation measure, such as the PREPARE-ENRICH Inventories (Fournier et al. 1983), which could act as a stimulant for discussion on many topics related to one’s FOO in premarital and marital relationships. The Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales (FACES) (Olson et al. 1979) is a self-report instrument used to measure an individual’s perception of family cohesion and adaptability, and the Circumplex Model also can act as a stimulant for many discussions related to one’s FOO (Olson et al. 1979). Family practitioners might also consider utilizing the RELATionship Evaluation Questionnaire, a relationship evaluation instrument designed to measure the individual, familial, cultural, and couple contexts and their relationships with each other. In particular, the RELATE evaluates the current perceived relationship between the individual, familial, cultural, and couple contexts and the partner’s satisfaction with those relationships. The inventories cited here can potentially aid therapists and educators to assist couples with whom they work to explore how FOO experiences influence the attributions made about oneself and one’s partner in the current relationship.

Conclusion

In this study we investigated the influence of the FOO experience on attributions made about aspects of one’s own personality and communication, and one’s partner’s personality and communication. The results of the structural model indicated an association between FOO experiences and the formation of relationship attributions. These influences were particularly strong on attributions of both self and partner communication variables. Gender differences were observed in attributions, most notably tied to communication. The overall specific focus of this study extends prior research emphasizing the influence of FOO experiences on the attributions that individuals make about themselves and their partners. Future research is needed to investigate the impact of specific aspects of the FOO experience on relational attributions. Couples researchers and practitioners can benefit from utilizing inventories, evaluations, and therapeutic and educational techniques to assess and explore the relative influence of the FOO experience on couples’ ability to form and maintain satisfying and healthy relationships.

References

Acitelli, L. K., Roger, S., & Knee, C. R. (1999). The role of identity in the link between relationship thinking and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 16, 591–618.

Amato, P. R. (1996). Explaining the intergenerational transmission of divorce. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58, 628–640.

Amato, P. R. (2010). Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new developments. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 650–666.

Amato, P. R., & Booth, A. (1991). Consequences of parental divorce and marital unhappiness for adult well-being. Social Forces, 69, 895–914.

Amato, P. R., & Booth, A. (1997). A generation at risk: Growing up in an era of family upheaval. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Amato, P. R., & Booth, A. (2001). The legacy of parents’ marital discord: Consequences for children’s marital quality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 637–638.

Amato, P. R., & Cheadle, J. (2005). The long reach of divorce: Divorce and child well-being across three generations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 191–206.

Bauserman, S. A., Arias, I., & Craighead, W. E. (1995). Marital attribution in spouses of depressed patients. Journal of Psychopathology, 66, 53–88.

Bowlby, J. (1979). The making and breaking of affectional bonds. London: Tavistock.

Bradbury, T. N., Beach, S. R. H., Fincham, F. D., & Nelson, G. M. (1996). Attributions and behavior in functional and dysfunctional marriages. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology, 64, 569–576.

Bradbury, T. N., & Fincham, F. D. (1992). Attributions and behavior in marital interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 613–628.

Bradbury, T. N., & Fincham, F. D. (1993). Assessing dysfunctional cognition in marriage: A reconsideration of the relationship belief inventory. Psychological Assessment, 5, 92–101.

Busby, D. M., Holman, T. B., & Taniguchi, N. (2001). RELATE: Relationship evaluation of the individual, family, cultural, and couple contexts. Family Relations, 50, 308–316.

Butler, M., & Gardner, B. (2003). Adapting enactments to couple reactivity: Five developmental stages. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 29, 311–327.

Campbell, J. M., Masters, M. A., & Johnson, M. E. (1998). Relationship of parental alcoholism to family-of-origin functioning and current marital satisfaction. Journal of Addictions and Offender Counseling, 19, 1055–1068.

Conger, R. D., Cui, M., Bryant, C. M., & Elder, G. H. (2000). Competence in early romantic relationships: A developmental perspective on family influences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 224–237.

Cropley, C. J., & Reid, S. A. (2008). A latent variable analysis of couple closeness, attributions, and relational satisfaction. The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 16, 364–374.

Curran, M., Hazen, N., Jacobvitz, D., & Feldman, A. (2005). Representations of early relationships predict marital maintenance during the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 19, 189–197.

Feeney, J. A., & Noller, P. (1990). Attachment style as a predictor of adult romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 281–291.

Fincham, F. D., Bradbury, T. N., Arias, I., Byrne, C. A., & Karney, B. R. (1997). Marital violence, marital distress, and attributions. Journal of Family Psychology, 11, 367–372.

Fincham, F. D., Harold, G. T., & Gano-Phillips, S. (2000). The longitudinal association between attributions and marital satisfaction: Direction of effects and role of efficacy expectations. Journal of Family Psychology, 14, 267–285.

Foster, M. A., Jurkovic, G. J., Ferdinand, L. G., & Meadows, L. A. (2002). The impact of the genogram on couples: A manualized approach. The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 10, 34–40.

Fournier, D. G., Olson, D. H., & Druckman, J. M. (1983). Assessing marital and premarital relationships: The PREPARE-ENRICH Inventories. In E. E. Filsinger (Ed.), Marriage and family assessment: A sourcebook for family therapy (pp. 229–250). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Friesen, M. D., Fletcher, G. J. O., & Overall, N. C. (2005). A dyadic assessment of forgiveness in intimate relationships. Personal Relationships, 12, 61–77.

George, C., Kaplan, N., & Main, M. (1985). An adult attachment interview. Berkeley: Department of Psychology, University of California. Unpublished manuscript.

Glen, N. D., & Kramer, K. B. (1987). The marriages and divorces of the children of divorce. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 49, 811–825.

Halford, W. K., Sanders, M. R., & Behrens, B. C. (2000). Repeating the errors of our parents? Family-of-origin spouse violence and observed conflict management in engaged couples. Family Process, 39, 219–235.

Hetherington, E. M. (1999). Social capital and the development of youths from nondivorced, divorced, and remarried families. In J. A. Collins & B. Laursen (Eds.), Relationships as developmental contexts: The 29th minnesota symposium on child psychology (Vol. 30, pp. 177–210). Hildale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hetherington, E. M. (2003). Intimate pathways: Changing patterns in close personal relationships across time. Family Relations, 52, 318–331.

Johnson, M. D., Karney, B. R., Rogge, R., & Bradbury, T. N. (2001). The role of marital behavior in the longitudinal association between attributions and marital quality. In V. Manusov & J. H. Harvey (Eds.), Attribution, communication behavior, and close relationships (pp. 173–192). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Karney, B. R., Bradbury, T. N., Fincham, F. D., & Sullivan, K. T. (1994). The role of negative affectivity in the association between attributions and marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 413–424.

Larson, J. H., Peterson, D. J., Heath, V. A., & Birch, P. (2000). The relationship between perceived dysfunctional family-of-origin rules and intimacy in young adult dating relationships. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 26, 161–175.

Larson, J. H., Taggart-Reedy, M., & Wilson, S. M. (2001). The effects of perceived dysfunctional family-of-origin rules on the dating relationships of young adults. Contemporary Family Therapy, 23, 489–512.

Levy, S. Y., Wamboldt, F. S., & Fiese, B. H. (1997). Family-of-origin experiences and conflict resolution behaviors of young adult dating couples. Family Process, 36, 297–310.

Manusov, V. (2002). Thought and action: Connecting attributions to behaviors in married couples’ interactions. In P. Noller & J. A. Feeney (Eds.), Understanding marriage: Developments in the study of couple interaction (pp. 14–31). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

McDonald, R. P., & Ho, M. R. (2002). Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods, 7, 64–82.

Mikulincer, M., Florian, V., Cowan, P. A., & Cowan, C. P. (2002). Attachment security in couple relationships: A systemic model and its implications for family dynamics. Family Process, 41, 405–434.

Miller, G. E., & Bradbury, T. N. (1995). Refining the association between attributions and behavior in marital interaction. Journal of Family Psychology, 9, 196–208.

Neff, L. A., & Karney, B. R. (2003). The dynamic structure of relationship perceptions: Differential importance as a strategy of relationship maintenance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 1433–1446.

O’Leary, K. D., & Cascardi, M. (1998). Physical aggression in marriage: A developmental analysis. In T. N. Bradbury (Ed.), The developmental course of marital dysfunction (pp. 343–374). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Olson, D. H., Sprenkle, D. H., & Russell, C. S. (1979). Circumplex Model of marital and family systems: I. Cohesion and adaptability dimensions, family types, and clinical applications. Family Process, 18, 3–27.

Pearce, Z. J., & Halford, W. K. (2008). Do attributions mediate the association between attachment and negative couple communication? Personal Relationships, 15, 155–170.

Sanford, K. (2005). Attributions and anger in early marriage: Wives are event-dependent and husbands are schematic. Journal of Family Psychology, 19, 180–188.

Story, L. B., Karney, B. R., Lawrence, E., & Bradbury, T. N. (2004). Interpersonal mediators in the transmission of marital dysfunction. Journal of Family Psychology, 18, 519–529.

Sumer, N., & Cozzarelli, C. (2004). The impact of adult attachment on partner and self-attributions and relationship quality. Personal Relationships, 11, 355–371.

Wamboldt, F. S., & Reiss, D. (1989). Defining a family heritage and a new relationship identity: Two central tasks in the making of a marriage. Family Process, 28, 317–335.

Weigel, D. J., Bennett, K. K., & Ballard-Reisch, D. S. (2003). Family influence on commitment: Examining the family of origin correlates of relationship commitment attitudes. Personal Relationships, 10, 453–474.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by funding from the College of Human Sciences at Texas Tech University and by the Family Studies Center at Brigham Young University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gardner, B.C., Busby, D.M., Burr, B.K. et al. Getting to the Root of Relationship Attributions: Family-of-Origin Perspectives on Self and Partner Views. Contemp Fam Ther 33, 253–272 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-011-9163-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-011-9163-5