Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to analyse the factors that influence female entrepreneurship in Spain, using institutional economics as the theoretical framework. The empirical research uses Spanish regional-level panel data (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor and National Statistics Institute of Spain) covering the period 2003–2010. The main findings indicate that informal factors (recognition of entrepreneurial career and female networks) are more relevant for female entrepreneurship than formal factors (education, family context and differential of income level). The research contributes both theoretically (advancing knowledge with respect to environmental factors that affect female entrepreneurship), and practically (for the design of support policies and educational programmes to foster female entrepreneurial activity).

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent years there has been a significant deceleration of the world economy and a downward revision of all economic growth forecasts for the Eurozone. In the case of Spanish economy, the gross domestic product (GDP) has fallen from 4.1 % in 2006 to −1.0 % in 2012 (Eurostat 2012) and the unemployment rising from 8.3 % in 2006 to 23.6 % in 2012 (INE 2003; Eurostat 2012). This overall downturn, along with the consequent contraction of both private and public consumption and the adjustments in the public investment policies implemented by the Spanish government, reflects the country’s current scenario. Within this context, the evolution of female entrepreneurial activity is more sensitive to economic recession than is male entrepreneurial activity (De Bruin et al. 2007; Manolova et al. 2012). However, Verheul et al. (2006, p. 151) suggest that women not only contribute to employment generation and economic growth, but they also “make a contribution to the diversity of entrepreneurship in the economic process”. Consequently, public administrations at all levels (European: Commission for Enterprise and Industry; Spanish: Directorate General of SME policy; and regional, such as: Department of Enterprises and Employment of the Government of Catalonia) are interested to develop policies to foster entrepreneurial activity and, specifically, female entrepreneurship.

The purpose of this paper is to analyse the factors that influence female entrepreneurship in Spain, using institutional economics (North 1990, 2005) as the theoretical framework. The empirical research uses Spanish regional-level panel data (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor and National Statistics Institute of Spain) covering the period 2003–2010.

The main findings indicate that informal factors (recognition of entrepreneurial career and female networks) are more relevant for female entrepreneurship than formal factors (education, family context and differential of income level). The research contributes both theoretically (advancing knowledge with respect to environmental factors that affect female entrepreneurship), and practically (for the design of support policies and educational programmes to foster female entrepreneurial activity).

After this brief introduction, the paper is structured in fourth additional sections. First, the theoretical framework of the investigation is presented. Next, the methodology employed in the empirical work is explained, and then, the most relevant results of the study are discussed. Finally, the article provides the conclusions and the future research lines.

2 Theoretical framework

As we mentioned before, the literature suggests the importance of the study of female entrepreneurship for both social and economic development. However, the investigations developed in this field were not considered relevant until the greater inclusion of women in the job market (Gofee and Scase 1990). Also, it should be noted that initially the research into female entrepreneurship was situated within the framework of feminist theories, since the initial objectives were focused more on obtaining advantageous political and social results for women than on academic findings (Hurley 1999).

Many scholars have dealt with gender differences and their relationship to business creation, considering topics such as characteristics of female entrepreneurs, entrepreneurial intentions, motivations and self-efficacy (Brush 1992; Rosa and Hamilton 1994; Brush et al. 2006; Gatewood et al. 2003; Sexton and Bowman-Upton 1990; Welter et al. 2006). Other investigations have drawn attention to a number of problems including those related to financing (Alsos et al. 2006; Brush 1992; Carter and Rosa 1998; Carter et al. 2007; Gatewood et al. 2009; Kim 2006; Marlow and Patton 2005; Verheul and Thurik 2001), management practices, growth and strategies for success (Brush and Hisrich 1988; Carter and Cannon 1991), entrepreneurship support policies (Carter 2000; Nilsson 1997) and socio-cultural factors that affect female entrepreneurial activity (Gatewood et al. 2009; Greve and Salaff 2003; Sorenson et al. 2008).

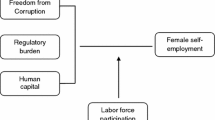

Although many theoretical frameworks have been used to analyse the entrepreneurship phenomenon, in this paper we used institutional economics as the conceptual framework (Guerrero and Urbano 2012; Liñán et al. 2011; Ribeiro-Soriano and Urbano 2009; Smallbone et al. 2010; Thornton et al. 2011; Urbano et al. 2011). Concretely, Amine and Staub (2009), Baughn et al. (2006), Estrin and Mickiewicz (2011) and Noguera et al. (2013) apply this theory to analyse the environmental factors that condition female entrepreneurship.

Institutional economics (North 1990, 2005) develops a general concept of institutions. Institutions are the limitations conceived by the human, and their main function is to facilitate a stable and, at the same time, evolutionary structure upon which interaction can take place. North (1990) distinguishes formal institutions (laws, regulations and government procedures) and informal institutions (beliefs, ideas and attitudes—that is, the culture of a society). In this study formal institutions are education, family context, income level differences, and informal institutions are entrepreneurial career, female networks and role models.

2.1 Education

Initial studies established a negative relationship between educational level and entrepreneurship, suggesting that the entrepreneurial career was left to those persons who did not have a high educational level (Collins and Moore 1964). However, recent works (Robinson and Sexton 1994; Bates 1995; Orser et al. 2012) demonstrated quite the opposite, that there was a positive relationship between higher levels of education and the likelihood of creating a business. Furthermore, these studies indicated that women relied much more upon advanced education as their route to self-employment than did men. Also, some authors suggested a positive relationship between education level and entrepreneurship, using human capital theory (Schultz 1959; Becker 1964) or resource-based theory (Urbano and Yordanova 2008; Castrogiovanni et al. 2011). In this line, Delmar and Davidsson (2000) and Davidsson and Honig (2003) suggested that individuals with more human capital or higher quality of human capital are more capable of perceiving entrepreneurial opportunities, when such opportunities exist. Also, Wilson et al. (2007, p. 402) highlight not only the importance of educational level but also the strong relationship between the inclusion of entrepreneurship education in tertiary education and entrepreneurial self-efficacy, indicating “entrepreneurship education can be positioned as an equalizer, possibly reducing the limiting effects of low self-efficacy and ultimately increasing the chances for successful venture creation by women”. However, Castagnetti and Rosti (2011) suggested that the relationship between education and entrepreneurial activity may be contradictory because higher education might generate better outside options in paid employment, making the consideration of entrepreneurship as a desirable career option less probable. Given the different positions found in the literature, in this paper we consider the level of education to be an important factor for entrepreneurial activity. Then, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1

Education has a positive effect on female entrepreneurial activity.

2.2 Family context

Literature established a strong relationship between family and female entrepreneurial activity. However, the existing relationship between family members has changed drastically in recent decades, moving away from the model of the traditional family, in which the principal activity of women who married was to take care of the children and a professional job was an option depending on the existing family context. Nowadays, marriage (and cohabitation by couples of all kinds) is postponed until a stable job is available, divorce rates are on the rise, and birth rates are falling. In this context, Mincer (1985) and Unger and Crawford (1992) suggest that reductions in average family size—and in how long marriages tend to last—increase the motivation to be part of the job market and to start a business, although they assert that women continue to figure as the principal caretaker of the family. Along the same lines, the study conducted by the OECD (2002) determined the negative relationship between the presence of children and female employment rates. On the other hand, Verheul et al. (2006) establish that although a priori women’s family context has a negative effect on female entrepreneurship due to the high demand on their time, there is evidence that self-employment may provide women with the possibility of adjusting the number of hours they dedicate to the needs of the family, thereby promoting female entrepreneurship. Also, Mattis (2004) and Shelton (2006) suggest that women can start a business to balance work and family responsibilities, although most of the research has focused to a greater extent on the work-role and family conflict experiences of women employees. Based on the previous literature the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2

The family context has a negative influence on entrepreneurship.

2.3 Income level differences

In previous investigations it has been demonstrated that one of the most relevant factors in the decision to create a business is the degree of workers satisfaction derived from their work place. When working for others means a less-than-desired income level for the workers, or when their work conditions are not what they expected, they may consider starting their own business (Douglas and Shepherd 1999; Dubini 1988; Eisenhauer 1995). In the case of working women, an added difficulty is found in accessing top positions in the firm (the “glass ceiling”). In this scenario, some women decide to create their own business to avoid the existing barriers to their professional and personal development (Powell 1999). Fairlie (2005) also suggests that young women who have created their own businesses tend to earn less than wage/salary workers. Based on the previous literature we suggest the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3

The existence of income level differences has a positive influence on female entrepreneurship.

2.4 Social recognition of the entrepreneurial career

Literature suggests divergent work preferences for men and women, evidenced by the way in which children were steered towards career choices deemed appropriate for their sex (Harriman 1985; Hisrich 1986). Along the same line, Baron et al. (2001), Langowitz and Minniti (2007) and Marlow and Patton (2005) consider that traditional roles assigned to women encourage the idea that entrepreneurial activity is less desirable for women than for men. Also, Arenius and Minniti (2005), Kolvereid and Isaksen (2006) and Langowitz and Minniti (2007) suggest that male and female perceptions are equally relevant to the decision to create a business, but these perceptions differ depending on the gender of the entrepreneur, given that the culture of a society, understood as a set of attitudes, values, social conventions belonging to that society, may encourage or discourage certain behaviours, including entrepreneurship (Thomas and Mueller 2000; Zahra et al. 1999). Specifically, these perceptions can further discourage women from being entrepreneurs in the advanced technology sectors where they perceived barriers to career advancement (Orser et al. 2012). Based on that the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4

Social recognition of the entrepreneurial career has a positive influence on female entrepreneurship.

2.5 Female network

Literature has demonstrated interest in how networks are a very relevant factor in the decision to create a business and to innovate within the existing firm (Capaldo 2007). In the entrepreneurial process entrepreneurs need some resources (such as information, capital, skills, etc.) and these could be available by accessing their networks (such as suppliers, customers, other entrepreneurs, etc.) (Aldrich and Zimmer 1986). Concerning the gender issues, Katz and Williams (1997) consider that networks available not depend on gender of entrepreneur, but instead on their status within the business. However, networks created by women were quite important to the process of creating a business than to strategic level (in the case of men the situation is the opposite) (Brush et al. 2009; Greve and Salaff 2003); women have fewer diverse relationships than men, thereby limiting the identification of opportunities (Renzulli et al. 2000); and women prefer collaborative networks, in many cases using their contacts to obtain more personal support than operational support at the business level (Díaz and Carter 2009; Sorenson et al. 2008). Also, some scholars confirm the importance of personally knowing someone who has recently started a business, and his/her influence on the probability of starting a business. In the case of women, this can be even more important when the entrepreneur they know personally is a family member (Hisrich and Brush 1986; Klyver and Grant 2010; Langowitz and Minniti 2007). Then, we propose:

Hypothesis 5

Female networks have a positive influence on female entrepreneurship.

2.6 Female role model

Role models could be defined as those people who are similar to oneself; this similarity allows one to more easily learn from the role model, facilitates the bond between them, and helps one to define their self-perception (Gibson 2004). Bandura (1989) in his social cognitive theory, maintains that individuals pay great attention to the role models who provide indirect lessons; these lessons arrive in the form of observation of individuals they consider worthy of emulation and who make use of skills or norms which may be of use to them in their own activities. The existence of entrepreneurs with similar characteristics is a factor that could increase the probability of creating a business, by reducing the uncertainty associated with the process of new firm creation (Davidsson and Honig 2003; Arenius and Minniti 2005). Role models are important because of their ability to enhance self-efficacy. Exposure to role models may have higher impact on women than on men when it comes to how they perceive their own entrepreneurial skills (Minniti and Nardone 2007). However, there is an absence of female role models that lies with the fact that the attributes one needs in order to be considered a role model are generated by the very organizations which place a higher value on male characteristics, as opposed to female characteristics, thus reducing the probability that women will become role models (Meyerson and Fletcher 2000). Furthermore, the importance of the existence of female role models is established, as these not only offer professional orientation, but also provide information and knowledge about specific problems brought about by the entrepreneurial activity, relating to reconciling work and family, an aspect considered to be quite important by women when making the final decision to create a business. Also, women associate the existence of male role models with the perception of the greater barriers they face in creating businesses (Lockwood 2006; Ridgeway and Smith-Lovin 1999). Based on the previous literature, we derived the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 6

Female role models have a positive influence on female entrepreneurship.

Hypothesis 7

Male role models have a negative influence on female entrepreneurship.

3 Methodology

As noted previously, in this research we proposed that female entrepreneurial activity is influenced by environmental factors, measured through informal and formal institutions. We test the hypotheses using Spanish regional-level panel data covering an 8-year period (2003–2010) from two sources of information: Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM)—the largest ongoing project of entrepreneurial dynamics in the world-, and National Statistics Institute of Spain (INE). Table 1 presents the list of the dependent and the independent variables used in this study. Our final sample consists of a panel of 103 observations from 19 Spanish regions. The general model considered in this study is the following:

For i = 1, 2, …, 19 Spanish regions; t = 2003, 2004, …, 2010.

In the above equation \(TEAfem_{it}\) is the dependent variable in year t; FI it is a matrix of formal institutions in region i in year t; II it is a matrix of informal institutions in region i in year t; CV it is a matrix of the control variable in region i in year t, and finally, \(\alpha_{i}\) is a vector of a region specific-constant term and is fixed over time, and \(\mu_{it}\) is an idiosyncratic disturbance that changes across time as well as across region.

We estimate all the regressions using country fixed effects, according to Hausman’s specification test, which does not rejects the null hypothesis that errors are independent within regions. The fixed effects model is also more appropriate because it estimates average within-regional changes in female entrepreneurship as the institutional environment changes over time. We discard autocorrelation problems but heteroskedasticity is detected. Thus, we estimate linear regressions with panel-corrected standard errors.

4 Results and discussion

In Table 2 are shown the means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients of the study variables. Table 3 presents the results of linear regressions with panel-corrected standard errors (PCSE).Footnote 1

The first model analyses the effect of control variables on female entrepreneurship. As we expected, both female unemployment and per capita income have a negative and significant (p < 0.01) influence on female entrepreneurial activity, in line with the reviewed literature (Carree et al. 2007; Wennekers and Thurik 1999; Wennekers et al. 2005). This model explains 35 % of the total variation of female entrepreneurial activity. In second model we include both the control variable and the formal institutions. This model slightly increases the percentage of total variation of female entrepreneurial activity explained, to 36 %. The results show that the coefficients of formal institutions have no statistically significant effect on female entrepreneurship. Also, model 3 shows the effect of informal institutions on female entrepreneurship. In this case, almost all the coefficients are statistically significant and they are the expected sign, except for the female role model. The explanatory power of the model increases with 55 % of the variance being explained.

Model 4 includes formal and informal institutions and control variables. Again, the coefficients of formal institutions are not statistically significant, while the coefficients of almost all informal institutions are significant. Finally, model 5 shows only the significant variables. This model explains 53 % of the total variation of female entrepreneurship. Thus, informal institutions such as entrepreneurial career and female networks have a positive and significant influence (p < 0.01) on female entrepreneurship in Spanish regions, when we controlled for female unemployment and per capita income.

As mentioned above, Hypothesis 1 suggests the positive impact of education on entrepreneurial activity and Hypothesis 2 suggests the negative influence of family context on female entrepreneurship. Similarly, Hypothesis 3 proposes that income level differences have a positive influence on entrepreneurship.

However, the coefficients of these considered formal institutions in model 2 and 4 are not statistically significant; thus, the data rejects Hypotheses 1, 2 and 3.

Likewise, Hypothesis 4 proposes that social recognition of the entrepreneurial career has a positive influence on female entrepreneurship. The coefficients of this variable in model 3, 4, and 5 are statistically significant (p < 0.05), and they are constant for all models. Thus, Hypothesis 4 is not rejected. The results show the positive influence of social recognition of the entrepreneurial career on female entrepreneurship.

In Hypothesis 5 we suggested that female networks have a positive influence on female entrepreneurship. The coefficient of this informal institution is positive and statistically significant (p < 0.05), thus, the data supports Hypothesis 5. In line with the literature, this result confirms the importance to female entrepreneurship of personally knowing someone who has created a business (Brush et al. 2009; Greve and Salaff 2003).

Finally, Hypothesis 6 postulates that female role models have a positive influence on female entrepreneurship, while the Hypothesis 7 suggests that male role models have a negative influence on female entrepreneurship. Models 3 and 4 show that female role model is not statistically significant, thus the data rejects Hypothesis 6. The coefficient of the male role model is also significant in model 3 and 4, but the significance level is low (p < 0.1). In fact, in model 5 male role model is not significant; hence Hypothesis 7 is not supported. These results suggest the importance of female role models versus male role models, as previous research has indicated (Lockwood 2006; Meyerson and Fletcher 2000; Ridgeway and Smith-Lovin 1999).

5 Conclusions

The main purpose of this paper was to contribute to the existing entrepreneurship literature by exploring the influence of environmental factors on female entrepreneurial activity in the Spanist context. To achieve this aim we developed a longitudinal analysis for the period 2003–2010, using data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor and the National Statistics Institute of Spain).

The main findings of this study show on the one hand that formal institutions, such as education, family context and income level differences, have no significant influence on female entrepreneurship in Spain. A possible explanation of this result could be the small difference of the formal institutional framework among the Spanish regions analysed. On the other hand, based on the findings of the current research, the informal institutions that appear to be most relevant to the creation of businesses by women are social recognition of the entrepreneurial career and female networks. As we stated earlier, the level of desirability conceded by the Spanish society through its values and social conventions towards entrepreneurship, has changed according to the evolution of the role assigned to women (Baron et al. 2001; Langowitz and Minniti 2007; Marlow and Patton 2005). Also, the presence of a greater number of women entrepreneurs in society, who provide visibility to their situation as female entrepreneurs, can help potential female entrepreneurs to create their own firm (Brush et al. 2009; Greve and Salaff 2003). Therefore, informal institutions in Spain are more important than formal institutions for the promotion of female entrepreneurship, which is in line with other studies in the field (Alvarez et al. 2011; Coduras et al. 2008; Noguera et al. 2013; Urbano et al. 2010).

With regard to the future research lines, a deeper analysis of the regional differences could be implemented, with the aim of improving the explanatory capacity of the proposed model. Also, it is anticipated that some other independent variables could be usefully incorporated for improving the findings.

The research contributes both theoretically (advancing knowledge with respect to environmental factors that affect female entrepreneurship), and practically (for the design of support policies and educational programmes to foster female entrepreneurial activity). Concretely, the government could increase the presence and visibility of female role models in the society, and also designing education programmes, from primary school to university, which will promote a set of attitudes and values that encourage the positive perception of entrepreneurship, especially of female entrepreneurship.

Notes

Given the correlations among several independent and control variables, we tested for the problem of multicollinearity that might affect the significance of the main parameters in the regressions through variance inflation factor (VIF) computations. The VIF values were low (lower than 5.03).

References

Aldrich HE, Zimmer C (1986) Entrepreneurship through social networks. In: Sexton D, Smilor R (eds) The art and science of entrepreneurship. Ballinger, New York, pp 3–23

Alsos GH, Isaksen E, Ljunggren E (2006) New venture financing and subsequent business growth in men- and women-led businesses. Entrep Theory Pract 30(5):667–686

Alvarez C, Urbano D, Coduras A, Ruiz-Navarro J (2011) Environmental conditions and entrepreneurial activity: a regional comparison in Spain. J Small Bus Enterp Dev 18(1):120–140

Amine LS, Staub KM (2009) Women entrepreneurs in sub-Saharan Africa. An institutional theory analysis from a social marketing point of view. Entrep Reg Dev 21(2):183–211

Arenius P, Minniti M (2005) Perceptual variables and nascent entrepreneurship. Small Bus Econ 24(3):233–247

Bandura A (1989) Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am Psychol 44(9):1175–1184

Baron R, Markman G, Hirza A (2001) Perceptions of women and men as entrepreneurs: evidence for differential effects of attributional augmenting. J Appl Psychol 86(5):923–929

Bates T (1995) Self-employment entry across industry groups. J Bus Ventur 10:143

Baughn CC, Chua B, Neupert KE (2006) The normative context for women’s participation in entrepreneurship: a multicountry study. Entrep Theory Pract 30(5):687–708

Becker GS (1964) Human capital. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Brush C (1992) Research on women business owners: past trends, a new perspective and future directions. Entrep Theory Pract 16(4):5–30

Brush CG, Hisrich RD (1988) Women entrepreneurs: strategic origins impact on growth. In: Kirchhoff BA, Long WA, McMillan WE, Vesper KH, Wetzel WE (eds) Frontiers of entrepreneurship research. Babson College, Wellesley, pp 612–625

Brush C, Carter N, Gatewood E, Greene P, Hart M (2006) Growth-oriented women entrepreneurs and their businesses: a global research perspective. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Brush C, de Bruin A, Welter F (2009) A gender-aware framework for women’s entrepreneurship. Int J Gender Entrep 1(1):8–24

Capaldo A (2007) Network structure and innovation: the leveraging of a dual network as a distinctive relational capability. Strateg Manag J 28(6):585–608

Carree M, Van Stel A, Thurik R, Wennekers S (2007) The relationship between economic development and business ownership revisited. Entrep Region Dev 19(3):281–291

Carter S (2000) Improving the numbers and performance of women-owned business. Some implications for training and advisory services. Educ Train 42(4–5):326–334

Carter S, Cannon T (1991) Women as entrepreneurs: a study of female business owners, their motivations, experience and strategies for success. Academic, London

Carter S, Rosa P (1998) The financing of male -and female- owned business. Entrep Region Dev 10(3):225–241

Carter S, Shaw E, Lam W, Wilson F (2007) Gender, entrepreneurship, and bank lending: the criteria and processes used by bank loan officers in assessing applications. Entrep Theory Pract 31(3):427–444

Castagnetti C, Rosti L (2011) Who skims the cream of the Italian graduate crop? Wage employment versus self-employment. Small Bus Econ 36(2):223–234

Castrogiovanni G, Urbano D, Loras J (2011) Linking corporate entrepreneurship and human resource management. Int J Manpow 32(1):34–47

Coduras A, Urbano D, Rojas A, Martínez S (2008) The relationship between university support to entrepreneurship with entrepreneurial activity in Spain: a GEM data based analysis. Int Adv Econ Res 14(4):395–406

Collins OF, Moore DG (1964) The enterprising man. Michigan State University, East Lansing

Davidsson P, Honig BL (2003) The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. J Bus Ventur 18(3):301–331

De Bruin A, Brush C, Welter F (2007) Advancing a framework for coherent research on women’s entrepreneurship. Entrep Theory Pract 31(3):323–339

Delmar F, Davidsson P (2000) Where do they come from? Prevalence and characteristics of nascent entrepreneurs. Entrep Region Dev 12(1):1–23

Díaz MC, Carter S (2009) Resource mobilization through business owners networks: is gender a issue? Int J Gend Entrep 1(3):226–252

Douglas EJ, Shepherd DA (1999) Entrepreneurship as a utility maximizing response. J Bus Ventur 15(3):231–251

Dubini P (1988) The influence of motivations and environment ob business start-ups: some hints for public policies. J Bus Ventur 4(1):11–26

Eisenhauer JG (1995) The entrepreneurial decision: economic theory and empirical evidence. Entrep Theory Pract 19(4):67–79

Estrin S, Mickiewicz T (2011) Institutions and female entrepreneurship. Small Bus Econ 37(4):397–415

Eurostat (2012) Database tables. Available from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Accessed 11 Oct 2012

Fairlie RW (2005) Entrepreneurship and earnings among young adults from disadvantaged families. Small Bus Econ 25:223–236

Gatewood E, Carter NM, Brush CG, Greene PG, Hart MM (2003) Women entrepreneurs, their ventures and the venture capital industry: an annotated bibliography. The Diana Project. ESBRI, Stockholm

Gatewood EJ, Brush C, Carter N, Greene P, Hart M (2009) Diana: a symbol of women entrepreneurs’ hunt for knowledge, money, and the rewards of entrepreneurship. Small Bus Econ 32(2):129–145

Gibson DE (2004) Role models in career development: new directions for theory and research. J Vocat Behav 65(1):134–156

Gofee R, Scase R (1990) Women in management: towards a research agenda. Int J Hum Resour Manag 1(1):107–125

Greve A, Salaff JW (2003) Social networks and entrepreneurship. Entrep Theory Pract 8(1):1–22

Guerrero M, Urbano D (2012) The development of an entrepreneurial university. J Technol Transf 37(1):43–74

Harriman A (1985) Women/men/management. Praeger, New York

Hisrich RD (1986) The woman entrepreneur: characteristics, skills, problems, and prescriptions for success. In: Sexton DL, Smilor RW (eds) The art and science of entrepreneurship. Ballinger, Cambridge, pp 61–84

Hisrich R, Brush C (1986) The woman entrepreneur. Lexington Books, Lexington

Hurley A (1999) Incorporation feminist theories into sociological theories of entrepreneurship. Women Manag Rev 4(2):54–62

INE (National Statistics Institute) (2003–2010, and 2012). Available from http://www.ine.es/. Accessed 11 Oct 2012

Katz JA, Williams PM (1997) Gender, self-employment and weak-tie networking through formal organizations. Entrep Region Dev 9(3):183–197

Kim GO (2006) Do equally owned small businesses have equal access to credit? Small Bus Econ 27(4–5):369–386

Klyver K, Grant S (2010) Gender differences in entrepreneurial networking and participation. Int J Gend Entrep 2(3):213–227

Kolvereid L, Isaksen E (2006) New business start-up and subsequent entry into self-employment. J Bus Ventur 21(6):866–885

Langowitz N, Minniti M (2007) The entrepreneurial propensity of women. Entrep Theory Pract 31:341–364

Liñán F, Urbano D, Guerrero M (2011) Regional variations in entrepreneurial cognitions: start-up intentions of university students in Spain. Entrep Region Dev 23(3–4):187–215

Lockwood P (2006) Someone like me can be successful: do college students need same-gender role models? Psychol Women Q 30(1):36–46

Manolova TS, Brush CG, Edelman LF, Shaver KG (2012) One size does not fit all: entrepreneurial expectancies and growth intentions of us women and men nascent entrepreneurs. Entrep Region Dev 24(1–2):7–27

Marlow S, Patton D (2005) All credit to men? Entrepreneurship, finance, and gender. Entrep Theory Pract 29(6):717–735

Mattis MC (2004) Women entrepreneurs: out from under the glass ceiling. Women Manag Rev 19(3):154–163

Meyerson D, Fletcher JK (2000) A modest manifesto for shattering the glass ceiling. Harv Bus Rev 78(1):126–136

Mincer J (1985) Intercountry comparisons of labor force trends and of related developments: an overview. J Labour Econ 3(1):1–32

Minniti M, Nardone C (2007) Being in someone else’s shoes: the role of gender in nascent entrepreneurship. Small Bus Econ 28(2–3):223–239

Nilsson P (1997) Business counselling services directed towards female entrepreneurs—some legitimacy dilemmas. Entrep Region Dev 9(3):239–258

Noguera M, Alvarez C, Urbano D (2013) Socio-cultural factors and female entrepreneurship. Int Entrep Manag J 9(2):183–197

North DC (1990) Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

North DC (2005) Understanding the process of economic change. Princeton University Press, Princeton

OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) (2002) OECD employment outlook, July 2002. OECD, Paris

Orser B, Riding A, Stanley J (2012) Perceived career challenger and response strategies of women in the advanced technology sector. Entrep Region Dev 24(1–2):73–93

Powell GN (1999) Reflections on the glass ceiling. Recent trends and future prospects. In: Powell GN (ed) Handbook of gender and work. Sage, Thousand Oaks, pp 325–345

Renzulli LA, Aldrich H, Moody J (2000) Family matters: gender, family, and entrepreneurial outcomes. Soc Forces 79(2):523–546

Ribeiro-Soriano D, Urbano D (2009) Overview of collaborative entrepreneurship: an integrated approach between business decisions and negotiations. Group Decis Negot 18(5):419–430

Ridgeway CL, Smith-Lovin L (1999) The gender system and interaction. Annu Rev Sociol 25:191–216

Robinson PB, Sexton EA (1994) The effect of education and experience of self-employment success. J Bus Ventur 9(2):141–156

Rosa P, Hamilton D (1994) Gender and ownership in UK small firms. Entrep Theory Pract 18(3):11–28

Schultz T (1959) Investment in man. An economist’s view. Social Serv Rev 33:110–117

Sexton D, Bowman-Upton N (1990) Female and male entrepreneurs: psychological characteristics and their role in gender-related discrimination. J Bus Ventur 5:29–36

Shelton LM (2006) Female entrepreneurs, work-family conflict, and venture performance: new insights into the work-family interface. J Small Bus Manage 44(2):285–297

Smallbone D, Welter F, Voytovich A, Egorov I (2010) Government and entrepreneurship in transition economies: the case of small firms in business services in Ukraine. Serv Ind J 30(5):655–670

Sorenson RL, Folker C, Brigham KH (2008) The collaborative network orientation: achieving business success through collaborative relationship. Entrep Theory Pract 32(4):615–634

Thomas AS, Mueller SL (2000) A case for comparative entrepreneurship: assessing the relevance of culture. J Int Bus Stud 31(2):287–301

Thornton PH, Ribeiro-Soriano D, Urbano D (2011) Socio-cultural factors and entrepreneurial activity: an overview. Int Small Bus J 29(2):1–14

Unger RK, Crawford M (1992) Women and gender: a feminist psychology. McGraw-Hill, New York

Urbano D, Yordanova D (2008) Determinants of the adoption of HRM practices in tourism SMEs in Spain: an exploratory study. Serv Bus 2(3):167–185

Urbano D, Toledano N, Ribeiro-Soriano D (2010) Analyzing social entrepreneurship from an institutional perspective: evidence from Spain. J Soc Entrep 1(1):54–69

Urbano D, Toledano N, Ribeiro-Soriano D (2011) Socio-cultural factors and transnational entrepreneurship: a multiple case study in Spain. Int Small Bus J 29(2):119–134

Verheul I, Thurik AR (2001) Start-up capital: differences between male and female entrepreneurs: does gender matter? Small Bus Econ 16(4):329–345

Verheul I, Van Stel A, Thurik R (2006) Explaining female and male entrepreneurship at the country level. Entrep Region Dev 18(2):151–183

Welter F, Smallbone D, Mirzakhalikova D, Schakirova N, Maksudova C (2006) Women entrepreneurs between tradition and modernity—the case of Uzbekistan. In: Welter F, Smallbone D, Isakova N (eds) Enterprising women in transition economics. Ashgate, Aldershot, pp 45–66

Wennekers S, Thurik R (1999) Linking entrepreneurship and economic growth. Small Bus Econ 13(1):27–55

Wennekers S, Van Stel A, Thurik R, Reynolds P (2005) Nascent entrepreneurship and the level of economic development. Small Bus Econ 24(3):293–309

Wilson F, Kickul J, Marlino D (2007) Gender, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial career intentions: implications for entrepreneurship education. Entrep Theory Pract 31(3):387–406

Zahra SA, Jennings DF, Kuratko DF (1999) The antecedents and consequences of firm-level entrepreneurship: the state of the field. Entrep Theory Pract 24(2):45–63

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge the financial support from projects ECO2013-44027-P (Spanish Ministry of Economy & Competitiveness) and 2014-SGR-1626 (Economy & Knowledge Department—Catalan Government).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Noguera, M., Alvarez, C., Merigó, J.M. et al. Determinants of female entrepreneurship in Spain: an institutional approach. Comput Math Organ Theory 21, 341–355 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10588-015-9186-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10588-015-9186-9