Abstract

The morphodynamic response of large tidal inlet/basin systems to future relative sea level rise (RSLR), incorporating both Eustatic sea level rise and local land subsidence effects, is qualitatively investigated using the state-of-the-art Delft3D numerical model and the Realistic analogue modelling philosophy. The modelling approach is implemented on a highly schematised morphology representing a typical large inlet/basin system located on the Dutch Wadden Sea (Ameland Inlet) over a 110-year study period. Three different RSLR Scenarios are considered: (a) No RSLR, (b) IPCC lower sea level rise (SLR) projection (0.2 m SLR by 2100 compared to 1990) and land subsidence, and (c) IPCC higher SLR projection (0.7 m SLR by 2100 compared to 1990) and land subsidence. Model results indicate that, for the 110-year study duration, the existing flood dominance of the system will increase with increasing rates of RSLR causing the ebb-tidal delta to erode and the basin to accrete. The rates of erosion/accretion are positively correlated with the rate of RSLR. Under the No RSLR condition, the tidal flats continue to develop while under the high RSLR scenario tidal flats eventually drown, implying that under this condition the system may degenerate into a tidal lagoon within the next 110 years. The tidal flats are stable under the low RSLR scenario implying that, at least for the next 100 years, this may be the critical RSLR condition for the maintenance of the system. Essentially the results of this study indicate that, as the Eustatic SLR is likely to be greater than the apparently critical rise of 0.2 m (by 2100 compared to 1990), the tidal flats in these systems will at least diminish. In the worst, but not unlikely, scenario that the Eustatic SLR is as high as the IPCC higher projections (0.7 m by 2100), the tidal flats may completely disappear. In either case, the associated environmental and socio-economic impacts will be massive. Therefore, more research focusing on the quantification of the physical and socio-economic impacts of RSLR on these systems is urgently needed to enable the development of effective and timely adaptation strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Large tidal inlet/basin systems, which usually contain extensive tidal flats that are rich in bio-diversity, are commonly found along the coasts of the Netherlands (Sha 1989), USA (Fenster and Dolan 1996), China (Gao and Jia 2003), Bangladesh (Ortiz 1994), and Vietnam (Duc 2008). The rich bio-diversity in these systems results in their localities becoming major tourist attractions, thus generating billions of tourism dollars for the local economy. Due to the associated increase in economic activities, local communities in these areas have grown rapidly in recent decades. The continued existence and/or growth of these environmental systems and communities are directly linked to the extensive tidal flats in the basins that are host to a plethora of diverse flora and fauna. However, these tidal flats are particularly vulnerable to any rise in the mean sea level and may be very sensitive to potential SLR impacts such as coastline transgression (landward retreat), regression (seaward advance), erosion of ebb-tidal deltas and sedimentation of tidal basins (Dissanayake et al. 2009b). In view of projected climate change impacts, a clear understanding of the potential impacts of relative sea level rise (i.e. Eustatic SLR and local effects such as subsidence/rebound etc.) on these inlet/basin systems is therefore a pre-requisite for the sustainable management of both the inlet/basin system and the communities that depend on them. To date however, little is known about the potential impact of relative sea level rise (RSLR) on this type of systems.

Only a few studies have investigated the potential impacts of RSLR on large inlet/basin systems. Friedrichs et al. (1990) investigated the impact of RSLR on tidal basins on the US East coast using the simple one-dimensional numerical model of Speer and Aubrey (1985) and found that RSLR results in sediment import or export depending on local basin geometry. Van Dongeren and De Vriend (1994) investigated the RSLR induced morphological behaviour of the Frisian inlet in the Dutch Wadden Sea using a one-dimensional semi-empirical model with a time-invariant RSLR. Using historical bathymetric surveys, Louters and Gerritsen (1995) found that the Wadden Sea accumulates sediment and bed levels keep up with RSLR. The sediment balance in the wider North Sea basin for the Holocene sea level rise was modelled by Gerritsen and Berentsen (1998). However, their large-scale results are not directly applicable at single tidal basin scale. Dronkers (1998) analysed the net sediment transport behaviour of the Wadden Sea tidal basins using an analytical approach and predicted that the basins are generally flood dominant and that RSLR tends to result in sediment accumulation in order to restore the dynamic equilibrium of the basin. Van Goor et al. (2003) adopted a semi-empirical modelling approach (ASMITA) to investigate the impact of RSLR on two of the Wadden Sea inlets, Ameland and Eierland, and showed the inlet/basin morphology of the two systems could keep up with a RSLR of more than 10 mm/year and 15 mm/year respectively.

The major shortcoming of the above studies is that none of them provided useful insight into the RSLR induced morphological changes in the inlet/basin morphology at spatial resolutions that are useful for efficient environmental and coastal management/planning in these socio-economically and environmentally sensitive areas. The study presented herein, which focuses on the Ameland inlet in the Dutch Wadden Sea area, attempts to address this knowledge gap by investigating the morphological evolution of a typical large inlet/basin system in response to RSLR at relatively high temporal and spatial resolutions.

2 Approach

2.1 Study area

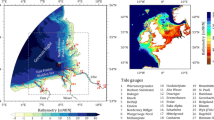

The Dutch Wadden Sea area is characterised by a chain of barrier islands (i.e. Texel, Eijerland, Vlie, Ameland and Frisian) forming several large inlet/basin systems (Fig. 1). The tidal inlets and associated tidal waterways are collectively defined as tidal basins. The extremely rich biodiversity in these tidal basins has resulted in the entire area becoming a major tourist attraction (12 million overnight stays per year (De Jong et al. 1999)) generating significant incomes for local industries (Euro 0.7 billion per year). Furthermore, the popularity of the area has led to billions of Euros worth of development and infrastructure within the coastal zone, particularly over the last 50 years. Additionally, the basin tidal flats are ecologically rich (i.e. feeding areas for birds, breeding areas for fish, resting areas for seals and plant (Vendel et al. 2003), species such as zoobenthos (Beukema et al. 1996)). A significant rise in the relative sea level (i.e. sea level rise with respect to a fixed bench mark, RSLR) is likely to threaten both the safety of the coastal developments/infrastructures and the physical characteristics of these tidal basins.

In the Wadden Sea area, RSLR has two main contributors. The first is the contribution due to Climate change driven Eustatic sea level rise (SLR). This is expected to accelerate during the 21st Century (IPCC 2001 (Houghton et al. 2001) and IPCC 2007 (Bindoff et al. 2007)). The second is the contribution due to the vertical land movement resulting from tectonic activities or compaction. The Wadden Sea area experiences significant land subsidence due to extensive gas extraction.

The present study focuses on one of the Wadden Sea inlets, the Ameland inlet, which experiences strong alongshore tidal currents (~0.3 m/s) and inlet currents (~1.0 m/s) (Ehlers 1988). This inlet was specifically selected as a case study because it is a relatively closed basin with minimal connectivity to other adjacent basins and hence lends itself to being numerically modelled as a closed system (Ridderinkhof 1988). The Ameland inlet is located between the barrier islands of Terschelling (on the west) and Ameland (on the east) (Fig. 1).

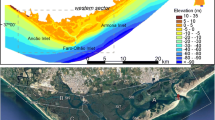

The bathymetry (measured in 2004) of the Ameland inlet is shown in Fig. 2 (De Fockert 2008). The average foreshore slope is about 1:100. The ebb-tidal delta has an area and volume of about 25 km2 and 130 Mm3 respectively and its maximum seaward protrusion is about 5 km (Cheung et al. 2007). Most of the bottom material in the basin is fine sand which has a mean diameter of about 200 μm.

The measured (2004) bathymetry of the Ameland inlet (De Fockert et al. 2008)

The tidal signal in the area is semidiurnal with a mean tidal range of about 2.0 m and propagates from West to East at a speed of about 15 m/s. The average annual significant wave height is about 1.0 m (Cheung et al. 2007). The combination of tidal- and wave-induced currents leads to an easterly net sediment transport from the western coast of Terschelling of about 1.0 Mm3/year (Steetzel 1995). At present, the tidal inlet consists of a two-channel system. The main inlet channel is oriented to the east at the basin end and to the west at the seaward end. The inlet width is about 4 km and the maximum depth is about 27 m.

The basin area is about 300 km2 and the associated tidal prism is 480 Mm3 (Sha 1989) resulting in a high tidal prism to alongshore sediment transport rate ratio (Ω/Mtot = 480) which is indicative of a highly stable inlet (Bruun and Gerritsen 1960). This implies that tidal-flow bypassing is the dominant transport process at the inlet, i.e. strong ebb currents flush littoral sediments out of the inlet gorge. A large part of the basin (about 60%) consists of tidal flats which are submerged during high tide and exposed during low tide. The tidal flats restrict water exchange with adjacent basins (Frisian to the east and Vlie to the west) during low tide (Fig. 1). During high tide, the flats form a tidal divide between the Ameland inlet basin and the adjacent basins making the basin a virtually closed system as far as tidal hydrodynamics are concerned. The sediment demand by the basin has been estimated to be about 0.4 Mm3/year (Louters and Gerritsen 1994). This is partly satisfied at the cost of adjacent coastlines and the ebb-tidal delta.

2.2 Numerical modelling

This study extensively uses the process-based model Delft3D developed by Deltares (formerly WL | Delft Hydraulics). The model allows one- (1D), two- (2DV and 2DH) and three-dimensional (3D) simulations. It also allows the discretisation of the study area in rectilinear, curvilinear or spherical co-ordinate systems. The primary variables of flow, water level and velocity, are specified on Arakawa C staggered grids. The model structure is shown in Fig. 3. As 3D processes such as vertical density stratification is not of critical importance to reach the objectives of the present study, here a 2DH version (depth averaged area model) of Delft3D is employed.

2.2.1 Hydrodynamics

The unsteady shallow water equations are solved via the alternating direction implicit (ADI) method to compute the hydrodynamics (Leendertse 1987; Stelling 1984; Stelling and Leendertse 1991). The system of equations consists of the horizontal momentum equations, the continuity equation, the transport equation and a turbulence closure model. The application of these equations in Delft3D is described in detail by Lesser et al. (2004) and is hence not reproduced here.

2.2.2 Sediment transport

Sediment transport is calculated using Van Rijn’s (1993) sediment transport formulas for total transport based on the depth-integrated advection–diffusion equation.

In Van Rijn’s (1993) formulations, the sediment transport below and above the reference height ‘a’ is defined as bed load and suspended load respectively. The reference height is mainly a function of water depth and a user defined reference factor. Sediment entrainment into the water column is facilitated by imposing a reference concentration at the reference height.

Suspended sediment transport is estimated based on the advection–diffusion equation. In depth-averaged simulations, the 3D advection–diffusion equation is approximated by the depth-integrated advection–diffusion equation:

where, D H is the horizontal dispersion coefficient (m2/s), \( \overline c \) is the depth averaged sediment concentration (kg/m3), \( {\overline c_{eq}} \) is the depth-averaged equilibrium concentration (kg/m3) as described by Van Rijn (1993) and T s is an adaptation time-scale (s). T s is given by (Galappatti 1983):

where, h is the water depth, w is the sediment fall velocity and T sd is an analytical function of shear velocity u * and w. Where, u * is given by:

Bed load sediment transport is given by:

where, D * is non-dimensional particle diameter.

and, T a is the non-dimensional bed shear stress.

For Eqs. 1–6, S b , is bed load transport rate (kg/m/s); f bed is a calibration factor (−); η is relative availability of sand at bottom (−); d 50 is the mean grain diameter (m); ρ s is density of sediment (kg/m3);\( f_c^\prime \) is current-related friction factor (−); \( \overline u \) is the depth average velocity (m/s); s is relative sediment density (−); υ is the horizontal eddy viscosity (m2/s); and, τ b,cr is critical bed shear stress for initiation of sediment transport (N/m2).

A d 50 of 200 μm, ρ s of 2,650 kg/m3 and f bed of 1.0 were specified in all simulations, while a spatially varying current-related friction factor was defined as described in Van Rijn (1993).

2.2.3 Morphodynamics

Coastal morphodynamic changes occur at time scales that are about 1 to 2 orders of magnitude greater than the hydrodynamic time scales (Stive et al. 1990). Therefore, in a conventional morphodynamic model, many hydrodynamic computations need to be performed to achieve significant morphological changes. Thus, conventional morphodynamic simulations, by necessity have been very long and inefficient. However, the morphological scale factor (MORFAC) approach presented by Lesser et al. (2004) and Roelvink (2006), which is used in Delft3D for bed level updates, circumnavigates this problem. In this approach, which is particularly geared at significantly improving the efficiency of morphodynamic calculations, the bed level changes calculated at each hydrodynamic time step are scaled up by multiplying erosion and deposition fluxes by a constant (MORFAC).

This approach also allows accelerated bed level changes to be dynamically coupled (on-line) with hydrodynamic computations (Fig. 3). Therefore, long-term morphological changes can be simulated at reasonable computational cost. In general usage, several trial simulations are undertaken with incremental MORFACs to determine the highest MORFAC value that can be used safely for a given simulation. Delft3D also recommends that bed level changes within one tidal cycle should not exceed 10% of the local water depth.

The model domain used in the present study contains dry banks which are outside the computational domain (Fig. 5). Therefore, the technique of dry cell erosion is applied to activate in the hydrodynamic calculations (Lesser et al. 2004; Roelvink 2006). This feature enables the gradual and realistic widening of the inlet.

2.3 Modelling philosophy

The traditional morphodynamic modelling philosophy is to calibrate and validate a model using laboratory and/or field measurements and then use the calibrated/validated model in hindcast or forecast mode to obtain quantitative estimates of system response to forcing. Depending on model accuracy, quality of data, and the accuracy of forcing conditions used for the hindcast/forecast, this traditional approach (i.e. virtual reality) may provide quantitatively accurate morphological predictions over relatively short time scales (~days-months). The present application is, however, a qualitative long term morphodynamic modelling exercise (~100 years) for which this traditional ‘virtual reality’ approach is not ideally suited due to several reasons. First, it is well known that a calibrated/validated model is quite likely to depart from the ‘truth’ the farther the simulation progresses past the calibration/validation period (Fig. 4). This is largely due to the almost unavoidable initial imbalance between initial model bathymetry and hydrodynamic forcing resulting in large and unrealistic morphological changes at the beginning of the simulation while the model attempts to create a morphology that is more or less in equilibrium with the forcing. Depending on model settings, these initially large changes may result in a positive feedback loop which may eventually produce nonsensical predictions. The deterministically chaotic nature of numerical models (Lorenz 1972) is another phenomenon that places significant uncertainties on the quantitative accuracy of long term morphodynamic model predictions. Secondly, significant input reduction is required for long term simulations (i.e. present computational costs do not allow multiple long term brute force simulations). Therefore, even a model that is perfectly calibrated/validated (i.e. representing real forcing/response relationships), cannot be expected to predict future system response accurately due to the highly schematised nature of future forcing that is unavoidable in long term morphodynamic simulations. Finally, to have confidence in the ‘virtual reality’ approach, the calibration/validation periods should be of a similar duration to the hindcast/forecast period. As such, to have a satisfactory level of confidence in a 100 year simulation, ample high quality calibration/validation data should be available over the last 100 years. This is clearly not the case as older (pre 1950) morphology/hydrodynamic data is of questionable quality, and also very sparse.

Pessimistic scenario for effect of calibration: real development, unadjusted model and calibrated model (Virtual reality) (after Roelvink and Reniers 2011)

For the long term forecasts necessary in this study, therefore, a different modelling philosophy (‘Realistic analogue’ (Roelvink and Reniers 2011)) is adopted. The ‘Realistic analogue’ philosophy essentially commences the simulation with a highly schematised initial bathymetry and allows the model to gradually produce the morphology that is in equilibrium with the main forcing (e.g. tidal forcing) that is to be used in forecast mode. The level of schematisation in the initial bathymetry is extreme in that while the geometry of the coastal system under investigation is very broadly represented, the initial bed is assumed to be more or less flat (i.e. flat bed morphology). Once this initial ‘establishment simulation’ produces a near-equilibrium morphology that is sufficiently similar to the observed system in terms of channel/shoal patterns and typical morphometric properties, the simulation can be extended into the future with slightly varied forcing (e.g. tidal forcing and slow sea level rise) to qualitatively investigate future system behaviour. It is, however, crucial, that the model generated ‘equilibrium morphology’ be compared with data to ensure that it is indeed an equilibrium morphology. This requirement, does limit the application of the ‘Realistic analogue’ philosophy to mature systems that are currently in equilibrium or have previously been in equilibrium prior to human interventions. It is emphasised that the ‘Realistic analogue’ approach is only suitable for qualitative assessments of long term system response to forcing.

2.4 Model implementation

2.4.1 Schematised bathymetry

A highly schematised Ameland bathymetry, based on measurements obtained in 2004 (Fig. 2), was used in the present study. The model domain essentially consists of three rectangular areas: the back barrier basin, the inlet gorge and the open sea area (Fig. 5). The back barrier basin has dimensions of 24 km × 13 km while the inlet gorge dimensions are 4 km × 3 km. The open sea area is 60 km in width and 24 km in length. The back barrier basin and the inlet gorge have a flat bed of 3 m depth. The open sea area consists of a concave profile from the shoreline up to 9 km offshore where the depth varies from 0 m to 20 m. Beyond that a constant depth of 20 m is specified. These depth values represent average characteristics of the inlet area and have hardly changed during the last 50 years or so. The shaded area in Fig. 5 indicates the dry banks (erodible area) which are specified at the beginning of simulations to enable the gradual development of conditions that are representative of the present-day morphology (see establishment simulation—Section 3.1).

2.4.2 Boundary forcing

The model domain consists of six boundaries, three on the Wadden Sea side and three on the North Sea side. The boundaries on the Wadden Sea side are specified as closed boundaries, while the North Sea side boundaries are open boundaries allowing water exchange through the boundaries. The northern boundary is forced with time varying water levels (tide and/or sea level rise). Neumann boundaries (i.e. zero gradient water levels) are specified for the two open lateral boundaries (west and east). This combination of boundary conditions is expected to minimise boundary disturbances (Roelvink and Walstra 2004).

-

(a)

Tidal forcing

Several previous long term modelling studies focussing on the Wadden Sea area have shown that models starting with a schematised flat bed bathymetry and forced with the M2, M4 and M6 tidal constituents are able to qualitatively reproduce the major morphological features of Wadden sea inlet/basin systems (Dastgheib et al. 2008; Dissanayake et al. 2009c). Therefore, the tidal forcing in the present study is limited to the M2, M4 and M6 tidal constituents. Tidal forcing conditions for the schematised model were extracted from the ZUNO model simulation (ZUNO is a well calibrated 2DH model which covers the entire North Sea area (Roelvink et al. 2001)). The ZUNO model was forced with astronomical tidal constituents and the amplitudes and phases of the dominant M2, M4 and M6 constituents were extracted at the offshore corner points of the computational domain (Fig. 5). These were subsequently used to force the open boundaries of the schematised model.

-

(b)

Relative sea level rise

Relative sea level rise consists of two main components: Eustatic SLR and local vertical land movement. Projections for global average Eustatic SLR are given in IPCC 2001 (Houghton et al. 2001) and IPCC 2007 (Bindoff et al. 2007). In this study, only the lower and higher ensemble average SLR projections (0.2 m and 0.7 m by 2100 compared to 1990) are taken into account. Vertical land movement is a result of subsidence and glacial rebounds. A local subsidence due to gas extraction has been observed in the study area (Marquenie and De Vlas 2005), and it is expected to be between 0 and 0.1 m over the next 50 years (Van der Meij and Minnema 1999). In the simulations undertaken herein, a land subsidence of 0.1 m in the next 50 years was specified, representing the worst case scenario. The effect of land subsidence is introduced by means of raising the mean water level in the model domain (see Dissanayake et al. 2008). The effect of the composite RSLR is implemented as a long period harmonic wave.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Establishment simulation

In this study the “Realistic analogue” philosophy described in Section 2.3 is adopted. The first step then is to analyse existing bathymetric data to determine whether the study area is in (or close to) morphological equilibrium. Two equilibrium relations (tidal prism vs inlet cross-sectional area (Jarret 1976; Eysink 1990); and tidal amplitude to mean channel depth ratio vs shoal volume to channel volume ratio (Wang et al. 1999)) were used for this purpose. Bathymetric data from 1930 to 2004 were available for the analysis. Figure 6 shows the bathymetry data in comparison to the equilibrium relations. Arrows indicate the general trend of the data points. If the points are closer to the lines, they tend to be equilibrium. The points on the lines imply equilibrium systems. According to both empirical equilibrium relations, the 2004 bathymetry appears to be very close to equilibrium conditions. Therefore, the “Realistic analogue” philosophy then dictates that the initial ‘establishment simulation’ starting from a schematised flat bed bathymetry should reproduce a bathymetry that is qualitatively similar to the 2004 measured bathymetry. An establishment simulation was thus undertaken, starting with the schematised bathymetry shown in Fig. 5, forced with M2, M4 and M6 tidal constituents.

At the start of the ‘Establishment simulation’ an inlet width of 1 km was specified in line with historical observations (Rijzewijk 1981). Two separate simulations were undertaken: one with a single MORFAC of 100 for the entire simulation and the other with time varying MORFACs where smaller MORFACs gradually changed to larger MORFACs as the simulation progressed in time. A MORFAC value of 100 was selected for the single MORFAC simulation following the results of rigorous performance comparisons of simulations with MORFACs of 50, 100, 200 and 400 presented by Dissanayake et al. 2009b, c.

A very rapid morphological evolution is shown at the beginning of both simulations while the initial flat bed bathymetry attempts to reach a state that is in equilibrium with the forcing (see, for example, the growth rate of the ebb-tidal delta during the first 20 years of the single MORFAC simulation shown in Fig. 9a). However, after this initial rapid adjustment, the evolution of both the ebb-tidal delta and the basin appears to reach quasi-steady conditions after 50 years of simulation (see Fig. 9) implying near-equilibrium conditions. Therefore, the length of the establishment simulation, the purpose of which is to establish a morphology that is in (or close to) equilibrium, was limited to 50 years.

3.1.1 Visual comparison

Figure 7 shows model predicted morphologies after the 50-year simulation period for both cases in comparison with the 2004 measured bathymetry. A visual comparison indicates that both model predictions are fairly consistent with the measurements where the main morphological features are concerned. Both the measured and modelled morphologies consist of an inlet with a two-channel system. Inside the basin, the main inlet channel extends towards the east, while a secondary channel extends towards the west. One major difference between the modelled and measured morphologies is that, in the measurements, the main inlet channel is located adjacent to the eastern barrier island while in the modelled morphologies it is located close to the western barrier island. The ebb-tidal delta and the main inlet channel are skewed to the west in both the measurements and model predictions. However, the western part of the model predicted ebb-tidal delta consists of more shoal areas in comparison to the measurements. These differences between the model predicted and measured morphologies are likely to be due to a) the highly schematised initial bathymetry, and b) the non-inclusion of wave effects (Dissanayake et al. 2009a and ongoing work).

3.1.2 Statistical comparison

To quantitatively determine whether the single or time varying MORFAC approach gives a better representation of the present bathymetry, a statistical analysis was undertaken using the Brier Skill Score (BSS) (Sutherland et al. 2004; Van Rijn et al. 2003). It is noted that the BSS is not a perfect method to evaluate model performance especially where individual characteristics such as basin infilling, lateral displacement and rate of bifurcation of channels etc. are concerned. However, at this point in time this is the most widely adopted method to objectively assess model skill (Ruessink et al. 2003; Pedrozo-Acuna et al. 2006; Ruggiero et al. 2009; Roelvink et al. 2009), and due to the lack of a better alternative, the BSS approach is adopted to evaluate model skill. The BSS is defined by Van Rijn et al. (2003) as:

where, brackets <> indicate the mean value. z measured , z MORFAC and z Flat are bed levels corresponding to measured bathymetry, predicted bathymetry with MORFAC and initial flat bathymetry.

In the above definition of the BSS, a value of 1 indicates an excellent comparison between the measurements and the model results (i.e. numerator is in the limit zero). Negative BSS values (i.e. numerator is large and/or denominator is small) imply large differences between the modelled and measured bathymetries.

A more comprehensive definition of the BSS is given by Sutherland et al. (2004):

where, \( \matrix{{*{20}{c}} {\alpha = r_{Y\prime X\prime }^2} \hfill & {\beta = {{\left( {{r_{Y\prime X\prime }} - \frac{{{\sigma_{Y\prime }}}}{{{\sigma_{X\prime }}}}} \right)}^2}} \hfill & {\gamma = {{\left( {\frac{{\left\langle {Y\prime } \right\rangle - \left\langle {X\prime } \right\rangle }}{{{\sigma_{X\prime }}}}} \right)}^2}} \hfill & {\varepsilon = {{\left( {\frac{{\left\langle {X\prime } \right\rangle }}{{{\sigma_{X\prime }}}}} \right)}^2}} \hfill \\ } \)and \( \matrix{{*{20}{c}} {Y\prime = {z_{measured}} - {z_{Flat}}} \hfill & {X\prime = {z_{MORFAC}} - {z_{Flat}}} \hfill \\ } \)

- α :

-

a measure of bed form phase error and perfect model gives α = 1

- β :

-

a measure of bed form amplitude error and perfect model gives β = 0

- γ :

-

an averaged bed level error and perfect model gives γ = 0

- ε :

-

a normalisation term which indicates the measured changes from the baseline bed

Van Rijn et al. (2003) and Sutherland et al. (2004) give the following classifications for the assessment of model performance against the BSS (Table 1).

In the present application, BSS values for the two simulations were calculated using both methods described above for a control area which contains the area of interest consisting of the ebb-tidal delta, inlet and basin areas (Fig. 8). Table 2 shows decomposition terms (α, β, γ and ε) of Sutherland et al. (2004) and the estimated BSS values of both methods. Difference in phase (α) and amplitude (β) of the two simulations is significant compared to that of mean (γ) and normalisation term (ε) indicating that phase and amplitude dominate on the BSS value. The BSS values thus calculated indicate that, according to Van Rijn et al. (2003), the comparison between measurements and morphologies predicted with single and time varying MORFAC approaches are reasonably good and poor respectively while both predicted morphologies are good according to Sutherland et al. (2004) while the single MORFAC simulation results in a higher BSS value compared to the time varying MORFAC simulation. Thus, the morphology predicted by the single MORFAC approach after a 50-year simulation period appears to be consistently and sufficiently close to the equilibrium morphology at the study area. Following the “Realistic analogue” philosophy, this equilibrium bathymetry is therefore adopted as the initial bathymetry to qualitatively investigate system response to various RSLR scenarios in subsequent model simulations. For convenience, this bathymetry (shown in Fig. 7c) will be referred to as ‘initial bathymetry’ from hereon.

3.1.3 Ebb-tidal delta and tidal basin evolution

The evolution of the ebb-tidal delta and tidal basin volumes during the Establishment simulation is shown in Fig. 9.

The ebb-tidal delta volume is estimated relative to the undisturbed bathymetry which consists of shore parallel contours (Walton and Adams 1976). The basin volume is defined as the sediment volume with reference to the initial flat bed. For the first 15 years of the Establishment simulation, the basin volume is slightly negative and then turns positive as a result of pattern formation on the flat bed. The ebb-tidal delta volume changes from zero to about 180 Mm3 by the end of the Establishment simulation, which is, to a first order, comparable, to the 2004 measured ebb-tidal delta volume of about 130 Mm3. The discrepancy of 50 Mm3 is likely due to the negligence of wave driven processes in the present simulations. Wave generated alongshore currents advect sediment away from the ebb-tidal delta and decrease ebb transport in the inlet. Both of these phenomena contribute to lower ebb-tidal delta volumes. The relative contribution of wave driven processes to inlet/basin evolution is the subject of ongoing research which is beyond the scope of this paper (which mainly focuses on the relative comparison among different RSLR scenarios). Figure 9 indicates an initially strongly ebb dominant system which becomes weakly flood dominant by the end of the 50 year simulation. This is consistent with contemporary observations of flood dominance at the study site (Dronkers 1986, 1998; Ridderinkhof 1988). These observations further justify the adoption of the morphology predicted at the end of the establishment simulation as a proxy for the present day morphology of the study site.

3.2 Relative sea level rise scenarios

Three simulations spanning a period of 110 years were undertaken with the above described ‘initial bathymetry’ to qualitatively investigate the effect of three potential RSLR scenarios on the morphological evolution of the study area. The three scenarios considered are given in Table 3.

Figure 10a shows the implementation of scenarios 2 and 3 via a harmonic schematisation. As per projections, the rate of Eustatic SLR increases during most of the 110-year period while the rate of land subsidence increases slightly for the first 50 years and then decreases (Fig. 10b).

3.2.1 Bed evolution

-

(a)

Visual comparison

Figure 11 shows the predicted morphology at the end of the three 110-year simulations. In general, two major differences can be identified in these patterns with respect to the initial bathymetry; eroding of the ebb-tidal delta, and significant infilling of the basin. Both of these characteristics become more pronounced with increasing RSLR.

The areas of the model predicted final ebb-tidal deltas are generally smaller than that of the initial bathymetry. This is largely due to the formation of pronounced channels within the ebb-tidal delta. More ebb-tidal delta channels are formed as the RSLR is increased leading to the smallest ebb-tidal delta area in Scenario 3 (i.e. IPCC H + LS) (Fig. 11d). This implies accelerated erosion of the ebb-tidal delta due to RSLR.

In the two non-zero RSLR scenarios (Fig. 11c and d), significant infilling of the basin leads to the disappearance of the pronounced channel configuration that is initially present in the basin. The shoal area (relative to initial MSL) increases as RSLR increases. However, the dominant east–west orientation, following the propagation direction of tidal wave (Dissanayake et al. 2009c), is still apparent at the end of all three RSLR scenario simulations.

-

(b)

Statistical comparison

Here, the model predicted bed level changes are quantified using two statistical methods. This analysis was also undertaken using the control area described in Section 3.1. The two statistical parameters employed are (a) the correlation coefficient (R 2), and (b) the BSS value of Van Rijn et al. (2003) (see Section 3.1.2). Both parameters are used to quantify the final predicted bed level changes (with respect to the initial bathymetry) between the RSLR and ‘No RSLR’ Scenarios.

Bed level changes (and not bed levels) are used in the calculation of R 2 to ensure that areas of no change (e.g. barrier islands) are not included in the calculation. This ensures that there is no bias towards high R 2 values due to the presence of such ‘no change’ areas inherent in the bathymetry. R 2 is defined as,

where, Δz NoRSLR is the bed level change of No RSLR scenario with respect to initial bathymetry. Similarly, Δz Scenario is the relative bed level change for the low and high RSLR scenarios.

High R 2 values indicate a high degree of similarity between the bed level changes in the RSLR and No RSLR scenarios, and thus no significant morphological influence of RSLR. Figure 12 shows the results of this comparison. The solid line indicates the linear fit and the cloud shows the density of bed level changes between two data sets. The darker the cloud area the higher the density. Generally, most bed level changes are found in the 0–10 m depth range. Scenario 3 (IPCC H + LS) is associated with the lower correlation coefficient (Fig. 12b) implying the highest bed level changes compared to the No RSLR scenario.

The second statistical parameter used here is the BSS value, given by:

where, z Scenario and z NoRSLR are predicted bed levels of the RSLR scenarios (low and high) and No RSLR scenario respectively. z Initial represents the initial bathymetry. This definition of BSS provides a relative measure of the RSLR effect with respect to the No RSLR situation. As the denominator remains unchanged for both RSLR scenarios, the BSS is determined by the numerator. As the numerator increases with z Scenario , the BSS decreases with increasing z Scenario .

Similar to R 2, BSS of 1 predicts excellent comparison between the bed level changes, implying in this case, an insignificant morphological influence of RSLR. The calculated BSS values given in Table 4 and indicate that higher bed level changes are associated with Scenario 3 (IPCC H + LS), which is consistent with the above correlation analysis.

The above discussion qualitatively indicates that:

-

Bed level changes increase as RSLR increases

-

The ebb-tidal delta erodes as RSLR increases

-

The basin accretes as RSLR increases

All of the above phenomena can be, to first order, explained by the cumulative sediment transport through the inlet. Figure 13 shows the cumulative sediment transport through the middle cross-section of the inlet for the 3 Scenarios given in Table 3. Mildly flood dominant transport patterns are predicted for all 3 scenarios during the first 10 years implying quasi-stable conditions. This is probably because RSLR is negligible during this period. After the first 10 years, the degree of flood dominance increases rapidly in time and increases with RSLR. This is probably because the tidal wave distortion due to inlet geometry and the reflected wave from the basin (Dronkers 1986, 1998), both of which result in flood dominance, are enhanced due to RSLR. Higher RSLR will likely result in more enhancement of the tidal wave distortion, thus leading to the unsurprising result (shown in Fig. 13) that flood dominance increases with increasing RSLR.

Cumulative sediment transport through the inlet during the 110-year simulation period for the three RSLR scenarios given in Table 3. Negative transport values imply landward (flood) transport

3.2.2 Evolution of morphological elements

Here the temporal evolution of the various morphological elements in the inlet/basin system under the three RSLR scenarios is described.

-

(a)

Ebb-tidal delta and basin volume

Figure 14 shows the variation of the ebb-tidal delta and basin volume during the 110-year simulations for the three different RSLR scenarios considered.

Evolution of a the ebb-tidal delta volume, and b the basin volume during the 110-year simulation period for the three RSLR scenarios given in Table 3

The ebb-tidal delta volume appears not to be correlated with the rate of RSLR during the first 20 years, probably due to the low rate of RSLR during this initial period (see Fig. 10). After this period, the eroded ebb-tidal delta volume appears to be strongly positively correlated with the rate of RSLR with the No RSLR and IPCC H + LS resulting in the highest and lowest ebb-tidal delta volumes respectively. Analysis of tidal prisms, tidal asymmetry (M2/M4) and phase difference (2M2-M4) suggests that this correlation is not due to any RSLR induced increase in tidal prism but due to the RSLR driven enhancement of the tidal wave interaction with the inlet geometry and changes in the reflected tidal wave which results in increased flood dominance. The degree of flood dominance is directly correlated with the rate of RSLR, thus causing the ebb-tidal delta erosion volume to increase with increasing rates of RSLR.

The basin volume change is inversely proportional to that of the ebb-tidal delta. The higher the erosion of the ebb-tidal delta the higher the sedimentation of the basin. The maximum volume decrease (Scenario 3) in the ebb-tidal delta is about 100 Mm3. In contrast, the corresponding volume increase in the basin is about 200 Mm3. This implies that there are additional sediment sources which are likely to include adjacent coastlines and erodible inlet banks. Model results imply that the volume of sediment supplied to the basin by these additional sources is of the same order of magnitude as that supplied by the ebb-tidal delta. The higher volume change in the basin (e.g. 127 Mm3 higher than ebb-tidal delta volume change in Scenario 3) also implies that the basin is likely to be more vulnerable to rising mean sea level than the ebb-tidal delta.

It is emphasised however that the above observations do not take into account any wave effects on sediment transport. Simulations that incorporate wave forcing are currently being undertaken and preliminary results indicate that the inclusion of wave effects generally results in less pronounced morphological elements. This is mainly due to wave-current interaction in the inlet gorge which augments flood-transport and reduces ebb-transport. Inclusion of wave effects also appears to result in relatively higher sediment distribution in the basin and the ebb-delta areas. The effect of waves on the long-term evolution of the schematised inlet will be discussed in detail in a separate manuscript.

-

(b)

Channel and tidal flat volume in the basin

The basin consists of channels and tidal flats. The channel volume is considered to be the volume of water in the basin below mean low water (MLW) while the volume of tidal flats is considered to be the volume of shoals that exist between mean low water and high water (MHW) levels in the basin (Fig. 15). The temporal evolution of these two elements is shown in Fig. 16.

Evolution of a the Basin channel volume, and b the Tidal flat volume during the 110-year simulation period for the three RSLR scenarios given in Table 3

The channel volume is almost constant during the first decade and slightly decreases thereafter under the No RSLR scenario (Fig. 16a). The slight decrease in the channel volume after the first decade is probably due to the expansion of tidal flats resulting from substantial sediment infilling into the basin. In Scenario 2 (Low RSLR), the channel volume increases only marginally (from 609 to 739 Mm3) during the 110-year simulation. In contrast, a significant volume change (from 609 to 974 Mm3) is predicted in Scenario 3 (High RSLR). This is because, under the latter scenario, the volume of sediment imported into the basin is not sufficient to fill the new accommodation space gained due to large rise in MSL (Beets and Van der Speck 2000; Coe and Church 2003; Cowell et al. 2003; Zhang et al. 2004).

The tidal flat volume depends on the channel slopes, the mean sea level and the sediment import into the basin (Friedrichs et al. 1990). Figure 16b shows the evolution of the flat volume for the different RSLR scenarios. The No RSLR scenario shows a significant increase in the flat volume (from 28 to 73 Mm3) due to the constant mean sea level and sediment infilling into the basin. Scenario 2 shows a relatively constant flat volume. This is due to counter balancing of new accommodation space gained due to the relatively low rise in MSL and the volume of sediment imported into the basin. In contrast, flat volume at the end of the simulation for Scenario 3 is virtually zero, indicating that tidal flats would drown under these conditions. In this case, the amount of sediment imported into the basin is larger (Fig. 13), but still insufficient to fill the new accommodation space gained by the large rise in MSL.

These results are in contradiction with the previous suggestions of Van Goor et al. (2003) who applied the semi-empirical model ASMITA to the same study area and found that the tidal flats were in dynamic equilibrium with RSLR. Specifically, Van Goor et al. (2003) found that the tidal flats could keep up with RSLR up to a rate of 10.5 mm/year. However, the results of the present study predict a relatively constant flat volume under Scenario 2, where the maximum RSLR rate is about 4 mm/year (average RSLR of about 3 mm/year over 110 years), and the drowning of tidal flats under Scenario 3 (maximum RSLR of about 10 mm/year and average RSLR over 110 years of 7 mm/year). Thus the present study implies that the critical RSLR condition for the continued maintenance of the tidal flats is that associated with Scenario 2, which represents an average RSLR rate that is significantly lower than the 10.5 mm/year critical RSLR rate suggested by Van Goor et al. (2003).

-

(c)

Flat area and height in the basin

The flat area is defined as the surface area of the tidal flats between mean low water and mean high water (Fig. 15). Average flat height is obtained by dividing the flat volume by the flat area. Figure 17 shows the evolution of the tidal flat area and flat height for the different RSLR scenarios.

Evolution of the: a Basin flat area, and b Tidal flat height during the 110-year simulation period for the three RSLR scenarios given in Table 3

The No RSLR scenario predicts an increase of about 60 Mm2 and 0.15 m in the flat area and flat height, respectively, during the 110-year simulation (Fig. 17a and b). This is due to the weakly flood dominant condition and constant MSL in this simulation. In Scenario 2 (low RSLR), the flat area increases marginally. This is evidence that, under these conditions, the volume of sediment imported slightly exceeds the accommodation space gained due to RSLR. In Scenario 3 (with the highest RSLR), however, both the flat area and flat height decrease significantly. This is another indication that the volume of sediment imported into the basin is inadequate to fill the accommodation space gained due to the large rise in MSL, and hence the tidal flats drown under this scenario. The highly significant reduction of the tidal flat height to almost zero (0.1 m) indicates that under these conditions, the tidal basin may degenerate in to a tidal lagoon. A similar response is described in the final stage of the basin-inundation model of Oertel et al. (1992). A good example of the occurrence of this phenomenon in nature is the Holocene evolution of the North Sea coastal plain described by Beets and Van der Speck (2000). The coastal plain was developed by the amalgamation of a large number of relatively small and shallow estuaries as RSLR resulted in the inundation of the valleys of the existing drainage pattern. This process has lead to the development of tidal basin and lagoon systems depending on the sediment supply to balance the accommodation space created by the rate of RSLR.

The net change in volume (after 110 years of simulation) of the various morphological elemental characteristics discussed above are shown in Table 5 with respect to the initial bathymetry (i.e. after the Establishment simulation). Negative values indicate a decrease compared to the initial value. In summary, Table 5 shows that:

-

The ebb-tidal delta erodes due to RSLR. The rate of erosion is positively correlated with the rate of RSLR.

-

The basin accretes due to RSLR. The rate of accretion is positively correlated with the rate of RSLR.

-

Under Scenario 2 (low RSLR), the tidal flats remains relatively unchanged over the 110 years, indicating that these conditions may represent critical forcing conditions (tipping point) for the continued maintenance of tidal flats.

-

Under Scenario 3 (high RSLR), the tidal flats are drowned, possibly leading to the degeneration of the system into a lagoon.

4 Conclusions

The potential physical impacts of relative sea level rise (RSLR) on large inlet/basin systems with extensive tidal flats have been qualitatively investigated using the state-of-the-art Delft3D numerical model and the Realistic analogue modelling philosophy. The Ameland inlet, a typical large inlet/basin system located in the Dutch Wadden Sea was selected as a case study. The model simulations spanned a duration of 110 years starting from present-day conditions. Three different RSLR Scenarios were considered: (a) No RSLR, (b) IPCC lower SLR projection (0.2 m SLR by 2100 compared to 1990) and land subsidence (IPCC L + LS) and (c) IPCC higher SLR projection (0.7 m SLR by 2100 compared to 1990) and land subsidence (IPCC H + LS).

Model results indicate that, for the 110-year (from present) study duration, the existing flood dominance of the system will increase with increasing rates of RSLR. As a result, the ebb-tidal delta erodes while the basin accretes. The erosion/accretion rates are positively correlated with the rate of RSLR. Under the No RSLR condition, the tidal flats continued to develop while under the high RSLR scenario the tidal flats eventually drowned, implying that under this condition the system may degenerate into a tidal lagoon. The tidal flats were more or less stable under the low RSLR scenario implying that this may be the critical RSLR condition for the maintenance of the system. This is in contrast with the previous finding (Van Goor et al. 2003) that the tidal flats can keep up with much higher RSLR rates (up to 10.5 mm/year). This difference can be seen as an indication of the uncertainties in both methods and should serve as a strong motivation to reduce these uncertainties via further research into the physical mechanisms governing tidal inlet response to RSLR.

As the Eustatic SLR is likely to be greater than the apparently critical rise of 0.2 m (by 2100 compared to 1990), these results indicate that the extensive tidal flats in these systems may slowly diminish, resulting in major environmental and socio-economic impacts. If the Eustatic SLR over the next century follows the higher end of IPCC projections, as has been the case over the last 15 years (Rahmstorf et al. 2007), then the tidal flats may entirely disappear converting these systems into tidal lagoons which may have such massive socio-economic impacts that the continued existence of some local communities may become untenable in the long-term. More research focusing on the quantification of the physical and socio-economic impacts of RSLR on these systems is therefore urgently needed. The lack of such quantitative information will severely hamper the development of effective and timely adaptation strategies that will enable at least the partial preservation of bio-diversity and the continued existence of local communities in these regions.

References

Beets DJ, Van der Speck JF (2000) The Holocene evolution of the barrier and the back-barrier basins of Belgium and the Netherlands as a function of late Weichselian morphology, relative sea-level rise and sediment supply. Neth J Geosci 79:3–16

Beukema JJ, Essink K, Michaelis H (1996) The geographic scale of synchronized fluctuation patterns in zoobenthos populations as a key to underlying factors: climatic or man-induced. ICES J Mar Sci 53:964–971

Bindoff NL, Willebrand J, Artale V, Cazenave A, Gregory J, Gulev S, Hanawa K, Le Quéré C, Levitus S, Nojiri Y, Shum CK, Talley LD, Unnikrishnan A (2007) Observations: oceanic climate change and sea level. In: Solomon S, Qin D, Manning M, Chen Z, Marquis M, Averyt KB, Tignor M, Miller HL (eds) Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and New York, pp 409–416

Bruun P, Gerritsen F (1960) Stability of coastal inlets. North Holland Publishing Co., Amsterdam

Cheung KF, Gerritsen F, Cleveringa J (2007) Morphodynamics and sand bypassing at Ameland Inlet, The Netherlands. J Coast Res 23(1):106–118

Coe AL, Church KD (2003) The sedimentary record of sea-level change. Cambridge University Press, pp 58–61

Cowell PJ, Stive MJF, Niedoroda AW, Swift DJP, De Vriend HJ, Buijsman MC, Nicholls RJ, Roy PS, Kaminsky GM, Cleveringa J, Reed CW, De Boer PL (2003) The coastal-tract (part 2): applications of aggregated modelling to lower-order coastal change. J Coast Res 19(4):812–827

Dastgheib A, Roelvink JA, Wang ZB (2008) Long-term process-based morphological modelling of the Marsdiep Tidal Basin. Mar Geol 256:90–100

De Fockert A (2008) Impact of relative sealevel rise on the Amelander Inlet Morphology, MSc thesis, Technical University of Delft

De Jong F, Bakker JF, van Berkel CJM, Dankers NMJA, Dahl K, Gätje C, Marencic H, Potel P (1999) Wadden Sea Quality Status Report. Wadden Sea Ecosystem No. 9. Common Wadden Sea Secretariat, Trilateral Monitoring and Assessment Group, Quality Status Report Group. Wilhelmshaven, Germany

Dissanayake DMPK, Roelvink JA, Van der Wegen M (2008) Effect of sea level rise on inlet morphology, 7th International Conference on Coastal and Port Engineering in Developing Countries Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Dissanayake DMPK, Ranasinghe R, Roelvink JA (2009b) Effect of sea level rise in inlet evolution: a numerical modelling approach, Journal of Coastal Research, SI 56, Proc. of the 10th International Coastal Symposium, Lisbon, Portugal, pp 942–946

Dissanayake DMPK, Roelvink JA, Ranasinghe JA (2009a) Process-based approach on tidal inlet evolution—Part II, Proc. International Conference in Ocean Engineering, Chennai, India

Dissanayake DMPK, Roelvink JA, Van der Wegen M (2009c) Modelled channel pattern in schematised tidal inlet. Coast Eng 56:1069–1083

Dronkers J (1986) Tidal Asymmetry and estuary morphology. Neth J Sea Res 20(2/3):117–131

Dronkers J (1998) Morphodynamics of the Dutch Delta. In: Dronkers J, Scheffers M (eds) Physics of estuaries and coastal seas. Balkema, Rotterdam

Duc AH (2008) Salt intrusion, tides and mixing in multi-channel estuaries, PhD Thesis, UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education, Delft, The Netherlands

Ehlers J (1988) The morphodynamics of the Wadden Sea. Balkema, Rotterdam

Eysink WD (1990) Morphologic response of tidal basins to changes. Coast Eng 1948–1961

Fenster M, Dolan R (1996) Assessing the impact of tidal inlets on adjacent barrier island shorelines. J Coast Res 12:294–310

Friedrichs CT, Aubrey DG, Speer PE (1990) Impacts of relative sea-level rise on evolution of shallow estuaries, coastal and estuarine studies, vol. 38. In: Cheng RT (ed) Residual currents and long-term transport. Springer, New York

Galappatti R (1983) A depth integrated model for suspended transport. Report 83–7, Communications on Hydraulics, Department of Civil engineering, Delft University of Technology

Gao S, Jia JJ (2003) Sediment and carbon accumulation in a small tidal basin: Yuchu, Shandong Peninsula, China. J Reg Environ Change 4(1):63–69

Gerritsen H, Berentsen CWJ (1998) A modelling study of tidally induced equilibrium sand balances in the North Sea during the Holocene. Cont Shelf Res 18:151–200

Houghton GT, Ding Y, Griggs DJ, Noguer M, Van der Linden PJ, Dai X, Maskell K, Johnson CA (2001) Climate Change Scientific Basis, Contribution of Working Group I to the third Assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change (IPCC). Cambridge University Press, UK, pp 74–77

Jarret JT (1976) Tidal prism-inlet relationships. Gen. Invest. Tidal inlets Rep. 3, 32 pp, US Army Coastal Engineering and Research Centre. Fort Belvoir, Va

Leendertse JJ (1987) A three-dimensional alternating direction implicit model with iterative fourth order dissipative non-linear advection terms. WD-333-NETH, Rijkswaterstaat, The Netherands

Lesser GR, Roelvink JA, Van Kester JATM, Stelling GS (2004) Development and validation of a three-dimensional morphological model. Coast Eng 51:883–915

Lorenz EN (1972) Predictability: does the flap of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil set off a tornado in Texas? American Asso. for the Advancement of Science Annual Meeting Prog., 139

Louters T, Gerritsen F (1994) The Riddle of sands; A tidal system’s answer to a rising sea level. Report 94.040. RIKZ, The Hague

Louters T, Gerritsen F (1995) The Riddle of sands; Technical report, National Institute for Coastal and Marine Management, Rijkswaterstaat, The Hague, ISBN90-369-0084-0

Marquenie JM, De Vlas J (2005) The impact of subsidence and sea level rise in the Wadden Sea: prediction and field verification. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, pp 355–363

Oertel GF, Kraft JC, Kearney MS, Woo HJ (1992) A rational theory for barrier-lagoon development. In: Quaternary Coasts of the United States: Marine and Lacustrine Systems. SEPM Spec. Publ., 48:77–87

Ortiz CAC (1994) Sea level rise and its impact on Bangladesh. Ocean Coast Manag 23:249–270

Pedrozo-Acuna A, Simmonds DJ, Otta AK, Chadwick AJ (2006) On the cross-shore profile change of gravel beaches. Coast Eng 53:335–347

Rahmstorf S, Cazanave A, Church J, Hansen J, Keeling R, Parker D, Somerville R (2007) Recent climate observations compared to projections. Science 316:709

Ridderinkhof H (1988) Tidal and residual flows in the Western Dutch Wadden Sea I: numerical model results. Neth J Sea Res 22(1):1–21

Rijzewijk LC (1981) Overzichtskaarten Zeegaten van de Waddenzea 1796–1985, Verzameling 86.H208

Roelvink JA (2006) Coastal morphodynamic evolution techniques. Coast Eng 53:277–287

Roelvink JA, Reniers AJHM (2011) A Guide to modelling coastal morphology, advances in coastal and Ocean engineering, world scientific, 261–263

Roelvink JA, Walstra DJ (2004) Keeping it simple by using complex models. Adv Hydrosci Eng V1:1–11

Roelvink JA, Van der Kaaij T, Ruessink BG (2001) Calibration and verification of large-scale 2D/3D flow models, Phase 1, Delft Hydraulics report, Z3029.11

Roelvink D, Reniers A, Van Dongeren A, De Vries JVT, McCall R, Lescinski J (2009) Modelling storm impacts on beaches, dunes and barrier islands. Coast Eng 56:1133–1156

Ruessink BG, Walstra DJR, Southgate HN (2003) Calibration and verification of a parametric wave model on barred beaches. Coast Eng 48:139–149

Ruggiero P, Walstra DJR, Gelfenbaum G, Van Ormondt M (2009) Seasonal-scale nearshore morphological evolution: field observations and numerical modelling. Coast Eng 56:1153–1172

Sha LP (1989) Variation in ebb-delta morphologies along the West and East Frisian Islands, the Netherlands and Germany. Mar Geol 89:11–28

Speer PE, Aubrey DG (1985) A study of non-linear propagation in shallow inlet/estuarine systems. Part II, theory. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 21:207–224

Steetzel H (1995) Voorspelling ontwikkeling kustlijn en buiten-delta’s waddenkust over de periode 1990–2040. WL Report No. H1887 prepared for Rijkswaterstaat, The Hague, The Netherlands (in Dutch)

Stelling GS (1984) On the construction of computational methods for shallow water flow problem. Rijkswaterstaat Communications vol. 35. Governing printing Office, The Hague, The Netherlands

Stelling GS, Leendertse JJ (1991) Approximation of convective processes by cyclic AOI methods. Proceeding of the 2nd ASCE Conference on Estuarine and Coastal Modelling, Tampa. ASCE, New York, pp 771–782

Stive MJF, Roelvink JA, De Vriend HJ (1990) Large-scale coastal evolution concept. Proc. 22nd Int. Conf. on Coastal Engineering, ASCE, New York

Sutherland J, Peet AH, Soulsby RL (2004) Evaluating the performance of morphological models. Coast Eng 51:917–939

Van der Meij JL, Minnema B (1999) Modelling on the effect of a sea-level rise and land subsidence on the evolution of the ground water density in the subsoil of the northern part of the Netherlands. J Hydrol 226:152–166

Van Dongeren AR, De Vriend HJ (1994) A model of morphological behaviour of tidal basins. Coast Eng 22:287–310

Van Goor MA, Zitman TJ, Wang ZB, Stive MJF (2003) Impact of sea-level rise on the morphological equilibrium state. Mar Geol 202:211–227

Van Rijn LC (1993) Principles of sediment transport in rivers, estuaries and coastal seas. AQUA Publications, the Netherlands

Van Rijn LC, Walstra DJR, Grasmeijer B, Sutherland J, Pan S, Sierra JP (2003) The predictability of cross-shore evolution of sandy beaches at the scale of storm and seasons using process-based profile models. Coast Eng 47:295–327

Vendel AL, Lopes SG, Santos C, Spach HL (2003) Fish assemblages in a tidal flat. Braz Arch Boil Technol 46(2)

Walton TL, Adams WD (1976) Capacity of inlet outer bars to store sand. In: Proc. 15th Coastal Engineering Conf., Honolulu, ASCE, New York, Vol. II, 1919–1937

Wang ZB, Jeuken C, De Vriend HJ (1999) Tidal asymmetry and residual sediment transport in estuaries. A literature study and applications to the Western Scheldt, WL|Delft Hydraulics report Z2749, Delft, the Netherlands

Zhang K, Douglas BC, Leatherman SP (2004) Global warming and coastal erosion. Clim Change 64:41–58

Acknowledgements

The work presented in this paper was carried out under the project ‘Sustainable development of North Sea and Coast’ (DC-05.20) of the Delft Cluster research project dealing with sustainable use and development of low-lying deltaic areas in general and the translation of specialist knowledge to end users in particular.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dissanayake, D.M.P.K., Ranasinghe, R. & Roelvink, J.A. The morphological response of large tidal inlet/basin systems to relative sea level rise. Climatic Change 113, 253–276 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-012-0402-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-012-0402-z