Abstract

This prospective 2-year longitudinal study tested whether inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptom dimensions predicted future peer problems, when accounting for concurrent conduct problems and prosocial skills. A community sample of 492 children (49 % female) who ranged in age from 6 to 10 years (M = 8.6, SD = .93) was recruited. Teacher reports of children’s inattention, and hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms, conduct problems, prosocial skills and peer problems were collected in two consecutive school years. Elevated inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity in Year-1 predicted greater peer problems in Year-2. Conduct problems in the first and second years of the study were associated with more peer problems, and explained a portion of the relationship between inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity with peer problems. However, prosocial skills were associated with fewer peer problems in children with elevated inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity. Inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity have negative effects on children’s peer functioning after 1-year, but concurrent conduct problems and prosocial skills have important and opposing impacts on these associations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Children with inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive behavior show disproportionate challenges with peer functioning [27, 37]. At clinically impairing levels, symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity (i.e., which comprise a diagnosis of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; ADHD) are associated with peer rejection, neglect and friendship problems [6, 17]. However, associations between inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptom dimensions and peer problems are also evident at diagnostically sub-threshold levels [2, 4, 17]. Developing a better understanding of the short-and long-term effects of these symptom dimensions on peer functioning is critical, given the pronounced negative outcomes associated with peer problems in childhood [6, 16, 30, 45].

Research describes a breadth of peer related difficulties in those diagnosed with ADHD in childhood [1, 4, 1, 25, 26, 27, 28]. Clinical levels of ADHD symptoms in childhood are associated with peer rejection, fewer dyadic friendships, and loneliness [7, 28, 29]. These findings are robust [27].

Moreover, even subthreshold levels of inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms contribute to peer problems [17, 26, 61]. It is likely that the salience and intrusiveness of symptoms of ADHD may have important short- and long-term impacts on peer functioning at sub-diagnostic levels [2, 17, 49]. For example, even a few persistent inattentive symptoms may be sufficient to give rise to lost opportunities for social learning, and even a few persistent hyperactive/impulsive symptoms may be sufficiently salient to cause peer rejection [1, 26, 49]. Although the mechanisms by which inattention and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms effect peer functioning have yet to be fully clarified, it seems reasonable to posit that these symptom dimensions will differentially and negatively impact social functioning.

A number of studies have described the prospective negative effects of ADHD on peer functioning [7, 23, 28, 48, 49]. These follow-up studies show that childhood ADHD is associated with longer-term peer rejection and social problems. Although these studies describe robust and negative longer-term impacts of ADHD on peer functioning, few studies have investigated the specific mechanisms which underlie peer problems [27, 37]. Developing a better understanding of prospective influence of symptom dimensions will further clarify processes that underlie long-term peer problems. Information garnered from community samples of children is essential, given that symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity show normal distributions in the general population and are associated with peer problems [2, 7, 59].

Furthermore, peer functioning is also negatively affected by behaviors that are highly associated with ADHD. Conduct problems, such as lying, fighting, bullying, co-occur at high rates with ADHD [10, 58]. Inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive children are at risk to develop early patterns of negative behaviors characterized by oppositionality, defiance, and rule breaking [8]. Researchers have queried whether these behaviors may subsequently limit appropriate social interchanges with peers, teachers and parents [14]. As such, through a pattern of social learning, conduct problems emerge which inhibit appropriate social functioning [18, 19]. Conduct problems may be one important link in the causal chain connecting symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity with peer problems [20, 23].

Similarly, children with elevated inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity may not gain the same quality of social understanding as their non-symptomatic peers [1, 14]. Through a process of social exclusion, inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive children may not be exposed to adequate social experiences and may not have sufficient experiences with positive peer interactions [13, 19, 26]. As such, prosocial skills may not have the opportunity to develop and not sufficiently serve a protective function within peer interactions. Deficits may emerge which subsequently negatively impact the quality of peer interactions [15]. Moreover, researchers have speculated that because of impoverished social experiences, inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive children may not have sufficient understanding of how to enact prosocial skills, and instead default to non-prosocial (i.e., conduct problems) as a means to garner social impact [11, 27, 36, 49]. Problematic interactions may quickly lead to sustained peer difficulties [27].

It is clear that ADHD, conduct problems and prosocial skills are differentially associated with peer functioning; however, a number of issues are in need of exploration. First, it is unclear the extent to which ADHD symptoms, conduct problems, and prosocial skills are enduring over 1-year in a community sample of children (i.e., in children in whom these behaviors are mostly below diagnostic threshold): they may differ in temporal stability. Second, it is unclear whether inattention and/or hyperactivity/impulsivity have an impact on peer functioning after 1-year. Third, it remains unclear whether conduct problem behaviors and prosocial skills account for part or all of the association between ADHD symptoms and peer problems. Inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity may contribute to increased conduct problems and decreased prosocial skills, which subsequently contribute to both immediate and longer-term peer problems. As such, conduct problems and prosocial skills may mediate the associations between inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity with peer problems.

This study reports on a 1-year follow-up of a community sample of children aged 6–10 years old, in whom we assessed the concurrent relationship between ADHD symptoms and peer problems [2]. In that cross-sectional analysis of the first data wave, we found that inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms were associated with elevated peer problems; however, conduct problems and prosocial skills partially accounted for the effect of hyperactive/impulsive symptoms, and fully accounted for the effects of inattention on peer problems. In both instances, concurrent conduct problems were associated with more peer problems, whereas concurrent prosocial skills mitigated some of the negative effects on peer functioning.

The current report extends the methods and findings from [Andrade and Tannock [2] in three ways. First, it estimates the 1-year stability of inattention and hyperactive/impulsive symptom dimensions, conduct problems and prosocial skills in the community sample of children. Second, it tests whether Year-1 symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity predict Year-2 peer problems. Third, it tests whether Year-1 or Year-2 conduct problems and prosocial skills mediate the relationship between ADHD symptoms and peer problems.

Based on findings from [2], it is hypothesized that inattention, hyperactivity/impulsivity, conduct problems and prosocial skills will be stable from one school year to the next (i.e., fromYear-1–2). Elevated inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity in Year-1 will predict elevated peer problems in Year-2. Conduct problems and prosocial skills will partially mediate the hyperactivity/impulsivity and peer problems association and fully mediate the inattention and peer problems association. More specifically, inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity will be associated with elevated conduct problems and fewer prosocial skills, which will subsequently be associated with more peer problems.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Data were derived from a larger longitudinal study of 492 children (49 % girls; aged 6–10 years; M = 8.6 years, SD = 0.93 year) investigating inattention and cognitive problems as predictors of academic functioning (Funded by Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada: #410-2008-1052). Children and their teachers were recruited initially from grades 1, 2, and 3 in seven public elementary schools in a large rural and suburban district school board in Canada, constituting 20 % of the schools in that board. This study followed and reassessed the sample of children 1 year later, when they were in Grades 2–4. As such, the reader is directed to previous publications for more detailed descriptions of procedures and methodology [2]; [43]; [44].

Study procedures were approved by Institutional Review Boards at the Hospital for Sick Children, University of Toronto, and the participating school boards. All of the teachers in grades 1–3 (n = 52) in participating schools consented to take part in the study in Year-1. Participating Grade-2 and Grade-3 teachers were re-consented in Year-2. The majority of participants from year 1 (96 %) consented to participate in year 2. Twenty new Grade 4 teachers consented to participate in the second year of the study. More specifically, from the teacher perspective, each Grade-2 and Grade-3 teacher rated two consecutive cohorts of children over the two-year study; Grade-1 and Grade 4 teacher’s rated just one cohort each. From the child perspective, each child was rated by two different teachers over the course of the two academic years. On average, teachers rated 75 students. Participating teachers were primarily Caucasian (86 %), female (95 %), with 14.7 years (SD = 7.9) on average of experience. 39 % of teachers had additional qualifications in special education. Written informed consent from the child’s parent and verbal assent from child were obtained.

Participating children spoke English as their primary language (97 %) and were primarily Caucasian (86 %). According to their parents who completed a basic demographics questionnaire that also probed their child’s mental health and behavior, children had the following mental and behavioral health issues: ADHD (4 %), language impairment (3 %), learning disability (3 %), and behavior problem (2 %). As such, children in the study represent a generally unimpaired and typical community sample of children. Data collection occurred in November of Years-1 and 2 to ensure that teachers had sufficient time to observe and interact with students prior to completing rating scales. Child participant descriptive information is displayed in Table 1.

Measures Completed by Teachers

Strengths and Weaknesses of ADHD-Symptoms and Normal Behavior Scale (SWAN)

The SWAN is an 18-item questionnaire based on DSM-IV-TR used measure symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity [56, 57]. The SWAN contains 9 items measuring symptoms of inattention and 9 items measuring symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity which comprise a diagnosis of ADHD. Items are phrased as positive statements and scored on a 7-point scale that captures both strengths and weaknesses. Thus, one advantage of the SWAN is that it yields scores that are normally distributed [47, 53]. For this study, scores on the SWAN that are typically rated on a scale of−3 (far above average) to +3 (far below average) were converted to positive values (i.e., scaled from 1–7) to aid interpretation of data (higher score indicates more symptoms or greater problems). The specificity of SWAN ratings to measure symptom domains of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity have been described (see [5, 43]). Similar to previous studies showing strong psychometric properties, internal consistencies of the inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity scales in the present study were high (0.97 and 0.98 respectively) (Arnett et al., [5]; Swanson et al., [56]). Mean teacher-reported inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity scores were used as the independent variables in the analyses.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)

Prosocial skills and conduct problems from Year-1 and Year-2, as well as Year-2 peer problems were assessed using discrete scales on the strengths and difficulties questionnaire [21, 22]. The SDQ is a brief screening questionnaire that inquires about 25 attributes via 25 questions that are evenly divided among five behavioral dimensions (i.e., subscales): prosocial skills, emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity-inattention, and peer problems. Example items from the prosocial skills scale include, “considerate of other people’s feelings” and “shares readily with other children, for example toys, treats, pencils”. Items from the conduct problems scale include, “often lies and cheats” and “often fights with children and bullies them”. Subscales do not overlap. Each item is rated on a 3-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not true), to 1 (somewhat true), to 2 (certainly true). The teacher version of the SDQ shows strong internal consistency and construct validity [55]. The factor structure of the SDQ has been supported by previous large-scale studies [24]. Consistent with past research, internal consistency of the prosocial skills, conduct problems and peer problems subscales in the present study were moderate for year−1 (0.83, 0.74, and 0.65 respectively) and year−2 (0.82, 0.74, 0.71 respectively) [12]. Mean teacher-reported scores for children’s prosocial skills, conduct problems, and peer problems were used in the analyses.

Analysis Plan

First, Pearson correlational analysis was conducted to ascertain relationships between participant age, sex and symptom scores (IV’s) to statistically determine covariates. Participant sex was significantly correlated with Year-2 symptom scores: males were rated with higher levels of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity compared to females. Therefore, this variable was included as a control in mediation analyses (see Table 2).

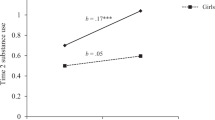

To test hypothesis 1, correlations and repeated measures ANOVA were computed to determine the stability of inattention, hyperactivity/impulsivity, conduct problems and prosocial skills from Year-1–2. To test the second hypothesis, four mediation models were conducted, guided by the causal steps strategy proposed by [9].Footnote 1 A script developed by [51] and run in SPSS V15 was used to test (1) the relation between the independent variable and the mediators, (2) the total effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, and (3) the direct effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable after accounting for the indirect effect of the mediators [9]. Full mediation occurs when the indirect effect of the mediators reduces the relationship between the independent variable and dependent variable to a non-statistically significant level. Partial mediation occurs when inclusion of the indirect effect accounts for some of the relationship between the independent and dependent variable, which still remains statistically significant. The first two mediation models tested whether Year-1 inattention predicted Year-2 peer problems, and whether Year-1 or Year-2 conduct problems and prosocial skills significantly mediated these associations. Models three and four tested whether Year-1 hyperactivity/impulsivity was associated with Year-2 peer problems, and whether Year-1 or Year-2 conduct problems and prosocial skills significantly mediated these associations. Prosocial skills and conduct problems were included in each model to test their indirect (i.e., mediational) effect along with the direct effect of symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity (IV’s) on peer problems (DV). Mediators were included simultaneously in each model to determine the magnitudes of their relative indirect effects. This was done to take into account concurrent prosocial skills and conduct problems. Analyses are summarized below, presented in Tables 4 and 7 and displayed in Figs. 1, 2, 3 4.

Graphical display of model 1. Path “c” delineates the total effect of Year-1 symptoms of Inattention on Year-2 Peer Problems. Path “a” delineates correlations between symptoms of Inattention and Year-1 Conduct Problems (CP) and Prosocial Skills (PS). Path “b” delineates semi-partial correlations between potential mediators and Year-2 Peer Problems. Path “c-prime” delineates the direct effect of Year- 1 Inattention on Year-2 Peer Problems after accounting for the indirect effect of the mediators. *p < .01, ns = non-significant at p > .05. The standardized regression coefficient (β) is indicated in brackets

Graphical display of model 2. Path “c” delineates the total effect of symptoms of Year-1 Inattention on Year-2 Peer Problems. Path “a” delineates correlations between symptoms of Inattention and Year-2 Conduct Problems (CP) and Prosocial Skills (PS). Path “b” delineates semi-partial correlations between potential mediators and Year-2 Peer Problems. Path “c-prime” delineates the direct effect of Year-1 Inattention on Year-2 Peer Problems after accounting for the indirect effect of the mediators.*p < .01, ns = non-significant at p > .05. The standardized regression coefficient (β) is indicated in brackets

Graphical display of model 2. Path “c” delineates the total effect of symptoms of year 1 Hyperactivity/Impulsivity on Year-2 Peer Problems. Path “a” delineates correlations between symptoms of Hyperactivity/Impulsivity and Year-1 Conduct Problems (CP) and Prosocial Skills (PS). Path “b” delineates semi-partial correlations between potential mediators and Year-2 Peer Problems. Path “c-prime” delineates the direct effect of symptoms of Year-1 Hyperactivity/Impulsivity on Year-2 Peer Problems after accounting for the indirect effect of the mediators. *p < .01, ns = non-significant at p > .05. The standardized regression coefficient (β) is indicated in brackets

Graphical display of model 2. Path “c” delineates the total effect of symptoms of Year-1 Hyperactivity/Impulsivity on Year-2 Peer Problems. Path “a” delineates correlations between symptoms of Hyperactivity/Impulsivity and Year-2 Conduct Problems (CP) and Prosocial Skills (PS). Path “b” delineates semi-partial correlations between potential mediators and Year-2 Peer Problems. Path “c-prime” delineates the direct effect of symptoms of Year-1 Hyperactivity/Impulsivity on Year-2 Peer Problems after accounting for the indirect effect of the mediators. *p < .01, ns = non-significant at p > .05. The standardized regression coefficient (β) is indicated in brackets

The bootstrapping procedure was used to test the significance of the indirect (i.e., mediational) effect. An SPSS script developed by Preacher and Hayes [51] was used to compute bootstrap estimates and confidence intervals. The bootstrapping procedure is recommended for tests of mediation and requires a single test of the hypothesis which reduces the probability of Type II error [50, 51]. Bootstrapping involves multiple re-sampling of the observed data with replacement to produce an estimate of an indirect effect. Multiplying component direct effects (i.e., the unstandardized regression coefficients) produces an estimate of the indirect effect and one bootstrap sample [50]. A large number of indirect effects are calculated and the distribution of these bootstrap estimates provides an approximation of the sampling distribution of the indirect effect and confidence interval. If the confidence interval does not include 0, then the indirect effect is significantly different from zero with 95 % confidence. The estimates presented are based on 5,000 bootstrap samples. Standardized regression coefficients, bootstrap estimates and confidence intervals are reported. Standardized effect sizes were computed for indirect effects using the ratio of the standardized indirect effect to the direct effect [54, 52].

Results

Attrition and Missing Data

Retention of participants was extremely good in this study. Only 13 (approximately 3 %) children who were rated in Year 1 were not rated in Year 2. This represents a small minority of the approximately 500 participants in this study. As such, there is not strong evidence to indicate selection bias due to drop-out and so more detailed comparisons were not conducted. Similarly, there is limited missing data in the sample. Teachers who completed measures were thorough and research team members were vigilant to ensure completeness of data. Listwise deletion of data was employed as a conservative means to handle missing data.

Descriptive Statistics

Pearson correlations were computed between Year-1 and Year-2 variables. As is shown in Table 3, correlations ranged from moderate to high. As expected, Year-1 and Year-2 inattention, hyperactivity/impulsivity, conduct problems and prosocial skills were significantly correlated. Importantly, prosocial skills were negatively correlated with symptom and problem scores, indicating that stronger prosocial skills were associated with fewer ADHD symptoms and less conduct problem behavior.

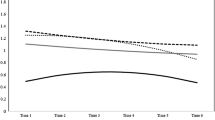

Repeated measures ANOVA were computed to compare Year-1 and Year-2 variables. As expected, inattention F(1, 471) = 1.32, p = 0.25, hyperactivity/impulsivity F(1, 471) = 0.29, p = 0.59, conduct problems F(1, 471) = 1.41, p = 0.23, and prosocial skills F(1, 471) = 2.29, p = 0.13 did not differ between years.

Mediation Analyses

Models 1 and 2: Inattention Symptoms and Peer Problems

As shown in Tables 4 and 5, and illustrated in path “c” of Figs. 1 and 2, Year-1 symptoms of inattention predict Year-2 peer problems (p < .01). Tests of path “a” show that Year-1 and Year-2 conduct problems are significantly positively associated with inattention (p < .01). Prosocial skills are significantly negatively associated with inattention (p < .01). Tests of path “b” demonstrate that both Year-1 and Year-2 conduct problems are significantly positively associated with peer problems (p < .01). By contrast, only Year-2 prosocial skills are significantly negatively associated with peer problems in the second year (p < .01). As a set, the total indirect effect of the Year-1 and Year-2 mediators are significant (p s < .01) and when included in the model reduced the effect of inattention on peer problems; however, the direct effects are still significant (p’s < .01) as shown in Table 4 and path c-prime of Figs. 1 and 2. Examination of the specific indirect effects indicates that Year-1 and Year-2 conduct problems (95 % bootstrap CI’s of 0.0104–0.0413 and 0.0121–0.0400 respectively) account for some of the negative impact of Year-1 inattention on Year-2 peer problems. However, only Year-2 prosocial skills (95 % bootstrap CI of 0.0082 to 0.0360) account for (i.e., reduce) the negative impact of Year-1 inattention on Year-2 peer problems. As such, results of models 1 and 2 are consistent with partial mediation.

Models 3 and 4: Hyperactivity/Impulsivity Symptoms and Peer Problems

As shown in Tables 6 and 7, and illustrated in path “c” of Figs. 3 and 4, Year-1 symptoms of hyperactivity/impulsivity predict Year-2 peer problems (p < .01). Tests of path “a” show that Year-1 and 2 conduct problems are significantly positively associated with hyperactivity/impulsivity (p < .01). Year-1 and 2 prosocial skills are significantly negatively associated with hyperactivity/impulsivity (p < .01). Tests of path “b” show that Year-1 and 2 conduct problems are significantly positively associated with peer problems (p < .01); however, only Year-2 prosocial skills are significantly negatively associated with peer problems (p < .01). As a set, the total indirect effects of the mediators were significant (p < .01). Examination of the specific indirect effects shows that Years-1 and 2 conduct problems (p < .01 and 95 % bootstrap Confidence Interval of 0.0135 to 0.0577 and 0.159 to 0.0489 respectively) account for some of the negative impact of Year-1 hyperactivity/impulsivity on Year-2 peer problems. However, only Year-2 prosocial skills (p < .01 and 95 % bootstrap Confidence Interval of 0.0094 to 0.0374) account for (i.e., reduce) the negative impact of Year-1 hyperactivity/impulsivity on Year-2 peer problems. Results of models 3 and 4 are consistent with partial mediation.

Discussion

Findings from this study show the negative effects of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity on peer functioning over the course of a year, even in a generally unimpaired community sample of children. Moreover, results highlight that conduct problems and prosocial skills partially mediate these associations; however, their influence varied in temporal course and direction of influence. Whereas concurrent conduct problems in Year-1 and Year-2 were associated with more peer problems in Year-2 of children with inattentive or hyperactive/impulsive symptoms, only prosocial skills in Year-2 were associated with less peer problems. Thus Year-2 prosocial skills reduced the negative impacts of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms on Year-2 peer problems, whereas Year-1 prosocial skills did not.

This study extends previously reported data on concurrent relationships between ADHD symptoms and peer problems [2]. The one-year negative effects of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity are concerning, especially so given that this study was undertaken with a community sample of children. Children in the present study continued to experience problems with peer interactions, which could be partially attributed to varying degrees of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity. Findings support the assertions that inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity are continuously distributed traits in child populations, and that even a few of these symptoms may have negative social implications [32], [61]. However, the precise mechanisms by which inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity confer risk to peer functioning are in need of investigation.

Further, as hypothesized, conduct problems partially mediated the associations between Year-1 symptom dimensions and Year-2 peer problems. This novel finding extends previous research by demonstrating the stable negative effects of even a few subthreshold-level conduct problems, and role in linking these symptom dimensions to peer problems in a community sample [2], [17] Although, the stability of conduct problems in identified children with disruptive behaviors is well documented, much less is known about stability and impacts in community samples of relatively unimpaired children [20], [25]. Importantly in this study, conduct problems accounted for a substantial portion of the variance linking Year-1 inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity with Year-2 peer problems. As such, conduct problems have a very salient negative contribution to social functioning and, from a causality perspective, are major factors disturbing peer functioning in this community sample of children.

Findings for prosocial skills differed somewhat from that of conduct problems in that only the concurrent association with peer problems in Year-2 was significant. This novel finding differs from that hypothesized and may be related to differences in saliency between prosocial skills and conduct problem behaviors. Children with conduct problems (who may also show a few prosocial skills) likely develop a negative reputation with peers and negative patterns of interaction, which contribute to social problems [7], [27], [46]. As such, children with conduct problem behaviors are rejected and show persistent peer problems. However, prosocial skills may be less salient and memorable from year to year. Peers may focus on recent prosocial actions, which more directly impact current peer relationships. It follows then that children’s current prosocial skills may more closely affect current peer interaction than do prosocial skills during the previous school year. Although reasonable, this assertion would benefit from further investigation.

Moreover, although not a primary focus of the study, sex was found to correlate significantly with inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity and was included as a covariate in analyses. Consideration of differential social outcomes associated with inattention, hyperactivity/impulsivity, prosocial behavior and conduct problems between boys and girls is an important area of study given research highlighting possible sexually dimorphic trajectories of brain development and behavior [35]. Further research specifically developed to test these differences would be beneficial.

Important to the present study is the emphasis on the concurrent effects of conduct problems and prosocial skills on peer functioning in children with even a few symptoms of inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity. Prosocial skills appear to mitigate some of the negative impacts of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity, and may lessen the negative effect of conduct problems on peer functioning. Findings are consistent with research stressing the importance of both domains of behavior on social functioning in typical and behavior disordered groups [2], [15], [20], [42]. Evidently, investigation of these two domains in children with and without diagnosed disruptive behavior will capture additional variance in social outcomes 15, [41], [42]. Considering outcomes only associated with negative behaviors, as done by much previous research with children with and without disruptive behavior, ignores a large portion of behaviors, which also impact social functioning.

Findings add to an existing body of research which describes the stability of inattentive and hyperactivity/impulsive symptom dimensions in non-diagnosed children [32]. This information is important, especially given recent work describing the validity of ADHD symptom dimensions [61]. In the present study, stability of these symptom dimensions highlights the likely accumulation of risk of emerging social and behavioral problems with development. As such, general social development programs may benefit from inclusion of strategies to address inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity to strengthen children’s social behaviors and protect against emergence of co-occurring problems.

Study Limitations

Although this study had novel and important findings some limitations should be considered. First, the findings were based solely on information gathered from classroom teachers: future studies may benefit from including ratings from children, which capture different aspects of functioning [31], [33]. Second, teacher ratings of conduct problems, prosocial skills, and peer problems were obtained from one instrument (SDQ), even though the various scales are independent and non-overlapping, the potential effect of shared method variance is a limitation. Moreover, although consistent with previous research, the peer problems scale showed somewhat lower internal consistency. Further study using supplementary measures, such as direct observation and coding of prosocial skills, conduct problems and peer functioning and assessing skills and behavior with experimental tasks would be informative. Third, this study had a very specific focus. Further research is needed that includes measures of other abilities (e.g., pragmatic language, aspects of social-cognition, aggression etc.), which are known to influence peer interactions [3], [34], [60]. Moreover, future research to determine the mechanisms by which specific prosocial skills (e.g., being kind to others, sharing etc.) and conduct problems (e.g., lying, hitting others etc.) impact peer functioning in children with inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms would be beneficial. Additionally, the study was conducted primarily with children in suburban schools, with a minority from rural schools, thus findings may not be generalizable to school children in urban areas. Finally, the analytic approach did not test the effect of continuity between Year 1 and 2 conduct problems and peer problems. Further more comprehensive cross-lagged models to expand on the findings would be informative.

Research and Clinical Implications

Results show the stability of inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms, their longer-term contribution to peer problems, and important mediating effect of conduct problems and prosocial skills on these relationships. The inclusion of instructional modules in school-based programs, which help children develop appropriate social behaviors, may benefit from instruction that promotes attention to social cues and reduces impulse control. Development of prosocial skills and problem-solving skills to reduce conduct problems are important; each of which affects peer functioning. Additionally, classroom interventions which include procedures to help teachers train peers to be socially inclusive, and adjunctive approaches which effect children’s social preferences, may further complement behavioral skills training [38], [39], [40]. These classroom-based approaches can be beneficial for children with any level of symptom severity and are important given that even a few symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity may contribute to peer problems.

Similarly, assessing symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity/impulsivity, prosocial skills and conduct problems of clinic-referred children with disruptive behavior may highlight the contributions of symptom traits or dimensions to peer functioning (regardless of diagnostic status). Building prosocial skills, while also facilitating self-regulation abilities to reduce conduct problems, may be an important and necessary combination for effective social interventions for children with inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive behaviors. As such, a focus on reduction of the breadth of symptoms and behaviors which are associated with peer problems is likely important for treatment planning.

Summary

This study examined whether symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity predicted future peer problems and whether these associations are partially explained by conduct problems and prosocial skills. Results showed that elevated inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity in Year-1 predicted greater peer problems in Year-2. Conduct problems in Years-1 and 2 explained a portion of these relationships and were associated with more peer problems. Prosocial skills in Year-2 also explained a portion of these relationships but were associated with fewer peer problems. Findings show that inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity have negative effects on peer functioning after one-year and concurrent conduct problems and prosocial skills have important and opposing effects on these associations.

Notes

Note: Although more complex analyses are possible for a nested design, a simpler design that lends itself to more straightforward interpretation was chosen. We are confident that nesting of data did not have a major impact on the findings given that teacher’s ratings of inattention, hyperactivity-impulsivity, conduct problems and prosocial skills showed stability from Years 1 to 2, despite children being rated by different teachers. As such, it is reasonable to assume that the nested design structure did not bias the obtained findings.

References

Andrade BF, Brodeur DA, Waschbusch DA, Stewart SH, McGee R (2009) Selective and sustained attention as predictors of social problems in children with typical and disordered attention ability. J Atten Disord 12(4):341–352

Andrade BF, Tannock R (2012) The direct effects of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity on peer problems and mediating roles of prosocial and conduct problem behaviors in a community sample of children. J Atten Disord. doi:10.1177/1087054712437580

Andrade BF, Waschbusch DA, Doucet AM, King S, McGrath PA, Stewart S et al. (2012) Social information processing of positive and negative hypothetical events in children with and without ADHD and conduct problems and in controls. J Atten Disord 16(6):491–504

Andrade BF, Waschbusch DA, King S (2005) Teacher classified peer social status: preliminary validation and associations with behavior ratings. J Psychoeduc Assess 23(3):279–290

Arnett AB, Pennington BF, Friend A, Wilcutt EG, Byrne B, Samuelsson S et al (2013) The SWAN captures variance at the negative and positive ends of the ADHD symptom dimension. J Atten Disord 17(2):152–162

Bagwell CL, Molina BSG, Pelham WE, Hoza B (2001) Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and problems in peer relations: predictions from childhood to adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40(11):1–16

Bagwell CL, Schmidt ME, Newcomb AF, Bukowski WM (2001) Friendship and peer rejection as predictors of adult adjustment. In: Nangle DW, Erdley CA (eds) The role of friendship in psychological adjustment, vol 91. Jossey-Bass, San Fransisco, pp 25–49

Barkley RA, Fischer M, Edelbrock CS, Smallish L (1990) The adolescent outcome of hyperactive children diagnosed by research criteria: i. An 8-year prospective follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 29(4):546–556

Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 51:1173–1182

Biederman J, Newcorn J, Sprich S (1991) Comorbidity of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder with conduct, depressive, anxiety, and other disorders. Am J Psychiatry 148(5):564–577

Bloomquist ML, August GJ, Cohen C, Doyle A (1997) Social problem solving in hyperactive-aggressive children: how and what they think in conditions of automatic and controlled processing. J Clin Child Psychol 26(2):178–180

Bourdon KH, Goodman R, Rae DS, Simpson G, Koretz DS (2005) The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: u.s. normative data and psychometric properties. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 44(6):557–564

Coie JD, Dodge KA, Kupersmidt JB (1990) Peer group behavior and social status. In: Asher SR, Coie JD (eds) Peer rejection in childhood. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 17–59

Coie JD, Dodge KA, Terry R, Wright V (1991) The role of aggression in peer relations: an analsysis of aggression episodes in boys’ play groups. Child Dev 62:812–826

Crick NR (1996) The role of overt aggression, relational aggression, and prosocial behavior in the prediction of children’s future social adjustment. Child Dev 67:2317–2327

DeRosier ME, Kupersmidt JB, Patterson CJ (1994) Children’s academic and behavioral adjustment as a function of the chronicity and proximity of peer rejection. Child Dev 65:1799–1813

Diamantopoulou S, Henricsson L, Rydell A-M (2005) ADHD symptoms and peer relations of children in a community sample: examining associated problems, self-perceptions, and gender differences. Int J Behav Dev 29(5):388–398

Dodge KA, Crick NR (1994) A Review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychol Bull 115(1):74–101

Dodge KA, Lansford JE, Burks VS, Bates JE, Petit GS, Fontaine R et al (2003) Peer rejection and social information-processing factors in the development of aggressive behavior problems in children. Child Dev 74(2):374–393

Dodge KA, Pettit GS (2003) A biopsychosocial model of the development of chronic conduct problems in adolescence. Dev Psychol 39(2):349–371

Goodman R (1997) The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38:581–586

Goodman R, Ford T, Simmons H, Gatward R, Meltzer H (2003) Using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) to screen for child psychiatric disorders in a community sample. Br J Psychiatry 177:534–539

Greene RW, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Sienna M, Garcia-Jetton J (1997) Adolescent outcome of boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and social disability: results from a 4-year longitudinal follow-up study. J Consult Clin Psychol 65(5):758–767

Hawes DJ, Dadds MR (2004) Australian data and psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 38:644–651

Hinshaw SP, Zupan BA, Simmel C, Nigg JT, Melnyk S (1997) Peer status in boys with and without Attention Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder: predictions from overt and covert antisocial behaviour, social isolation, and authoritative parenting beliefs. Child Dev 68(5):880–896

Hodgens JB, Cole J, Boldizar J (2000) Peer-based differences among boys with ADHD. Clin Child Psychol 29(3):443–452

Hoza B (2007) Peer functioning in children with ADHD. J Pediatr Psychol 32(6):655–663

Hoza B, Gerdes AC, Mrug S, Hinshaw SP, Bukowski WM, Gold JA et al (2005) Peer assessed outcomes in the multimodal treatment study of children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiat 34:74–86

Hoza B, Mrug S, Gerdes AC, Hinshaw SP, Bukowski WM, Gold JA et al (2005) What aspects of peer relationships are impaired in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? J Consult Clin Psychol 73(3):411–423

Kupersmidt JB, Coie JD, Dodge KA (1990) The role of poor peer relationships in the development of disorder. In: Asher SR, Coie JD (eds) Peer rejection in childhood. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 274–305

La Greca AM (1981) Peer acceptance: the correspondence between children’s sociometric scores and teachers’ ratings of peer interactions. J Abnorm Child Psychol 9(2):167–178

Lahey BB, Willcutt EG (2010) Predictive validity of a continuous alternative to nominal subtypes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder for DSM-V. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiat 39(6):761–775

Landau S, Milich R, Whitten P (1984) A comparison of teacher and peer assessment of social status. J Clin Child Psychol 13(1):44–49

Leonard MA, Milich R, Lorch E (2011) The role of pragmatic language use in mediating the relation between hyperactivity and inattention and social skills problems. Speech Lang Hear Res 54:567–579

Mahone EM, Wodka EL (2008) The neurobiological profile of girls with ADHD. Dev Disabil Res Rev 14:276–284

Matthys W, Cuperus JM, Van Engeland H (1999) Deficient social problem-solving in boys with ODD/CD, with ADHD, and with both disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 38(3):311–321

McQuade JD, Hoza B (2008) Peer problems in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: current status and future directions. Dev Disabil 14:320–324

Mikami AY, Gregory A, Allen JP, Pianta RC, Lun J (2011) Effects of a teacher professional development intervention on peer relationships in secondary classrooms. Sch Psychol Rev 40(3):367–385

Mikami AY, Griggs MS, Lerner MD, Emeh CC, Reuland, MM Jack, A et al. (2012) A randomized trial of a classroom intervention to increase peers’ social inclusion of children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 81:100–112. doi:10.1037/a0029654

Mikami AY, Griggs MS, Reuland MM, Gregory A (2012) Teacher practices as predictors of children’s classroom social preference. J Sch Psychol 50:95–111

Mikami AY, Hinshaw SP (2003) Buffers of peer rejection among girls with and without ADHD: the role of popularity with adults and goal-directed solitary play. J Abnorm Child Psychol 31(4):381–397

Nelson DA, Crick NR (1999) Rose-colored glasses: examining the social information processing of prosocial young adolescents. J Early Adolesc 19(1):17–38

Normand S, Flora DB, Toplak ME, Tannock R (2012) Evidence for a general ADHD factor in a longitudinal general school population study. J Abnorm Child Psychol 40:555–567

Normand S, Tannock R (2012) Screening for working memory deficits in the classroom: The psychometric properties of the working memory rating scale in a longitudinal school-based study. J Atten Disord. doi:10.1177/1087054712445062

Ollendick TH, Weist MD, Borden MC, Greene RW (1992) Sociometric status and academic, behavioral, and psychological adjustment. A five-year longitudinal study. J Consult Clin Psychol 60(1):80–87

Pelham WE, Bender ME (1982) Peer relationships in hyperactive children: description and treatment. In: Gadow K, Bailer I (eds) Advances in learning and behavioral disabilities, vol 1. JAI Press, Greenwich, pp 366–436

Polderman TJC, Derks EM, Hudziak JJ, Verhulst FC, Posthuma D, Boomsma DI (2007) Across the continuum of attention skills: a twin study of the SWAN ADHD rating scale. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 48:1080–1087

Pope WA, Bierman KL (1999) Predicting adolescent peer problems and antisocial activities: the relative roles of aggression and dysregulation. Dev Psychol 35:335–346

Pope WA, Bierman KL, Mumma GH (1991) Aggression, hyperactivity, and inattention-immaturity: behavior dimensions associated with peer rejection in elementary boys. Dev Psychol 27:663–671

Preacher KJ, Hayes A (2004) SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 36(4):717–731

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF (2008) Contemporary approaches to assesing mediation in communication resarch. In:AF Hayes, MD Slater, LB Snyder (Eds.) The Sage sourcebook of advanced data analysis methods for communication research (pp. 13–54). Thousand Oaks: Sage

Preacher KJ, Kelley K (2011) Effect size measures for mediation models: quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychol Methods 16:93–115

Robacey P, Amre D, Schachar R, Simard L (2007) French version of the strengths and weaknesses of ADHD symptoms and normal behaviors (SWAN-F) questionnair. Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 16:80–89

Sobel ME (1982) Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S (ed) Sociological methodology 1982. American Sociological Association, Washington DC, pp 290–312

Stone L, Otten R, Engels RC, Vermulst AA, Janssens JM (2010) Psychometric properties of the parent and teacher versions of teh Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire for 4–12 year olds: a review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 13:254–274

Swanson JM, Schuck S, Mann M, Carlson C, Hartman K, Sergeant JA (2001) Categorical and dimensional definitions and evaluations of symptoms of ADHD: The SNAP and SWAN rating scales

Swanson JM, Schuck S, Mann M, Carlson C, Hartman K, Sergeant JA (2001) Over-identification of extreme behavior in the evaluation and diagnosis of ADHD/HKD

Waschbusch DA (2002) A meta-analytic examination of comorbid hyperactive–impulsive–attention problems and conduct problems. Psychol Bull 128(1):118–150

Waschbusch DA, Sparkes SJ, Northern Partners InAction for Children and Youth. (2003) Rating scale assessment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) symptoms: is there a normal distribution and does it matter? J Psychoeduc Assess 21:261–281

Waschbusch DA, Willoughby MT (2008) Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and callous-unemotional traits as moderators of conduct problems when examining impairment and aggression in elementary school children. Aggress Behav 34(2):139–153

Willcutt EG, Nigg JT, Pennington BF, Solanto M, Rohde LA, Tannock R et al. (2012) Validity of DSM–IV attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptom dimensions and subtypes. J Abnorm Psychol. 121(4):991–1010

Acknowledgments

This study was funded in part by a Social Sciences and Research Council Grant #410-2008-1052 [RT], the Canada Research Chairs program [RT], a CIHR Canadian Child Health Clinician Scientist Training Program (CCHCSP) Career Development Award [BA], and New Investigator Fellowship with the Ontario Mental Health Foundation [BA].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Andrade, B.F., Tannock, R. Sustained Impact of Inattention and Hyperactivity-Impulsivity on Peer Problems: Mediating Roles of Prosocial Skills and Conduct Problems in a Community Sample of Children. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 45, 318–328 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-013-0402-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-013-0402-x