Abstract

Children with callous–unemotional (CU) traits manifest a range of deficits in their emotional functioning, and parents play a key role in socializing children’s understanding, experience, expression, and regulation of emotions. However, research examining emotion-related parenting in families of children with CU traits is scarce. In two independent studies we examined emotion socialization styles in parents of children high on CU traits. In Study 1, we assessed parents’ self-reported beliefs and feelings regarding their own and their child’s emotions, in a sample of 111 clinic-referred and community children aged 7–12 years. In Study 2, we directly observed parents’ responding to child emotion during an emotional reminiscing task, in a clinic sample of 59 conduct-problem children aged 3–9 years. Taken together, the results were consistent in suggesting that the mothers of children with higher levels of CU traits are more likely to have affective attitudes that are less accepting of emotion (Study 1), and emotion socialization practices that are more dismissing of child emotion (Study 2). Fathers’ emotion socialization beliefs and practices were unrelated to levels of CU traits. Our findings provide initial evidence for a relationship between CU traits and parents’ emotion socialization style, and have significant implications for the design of novel family-based interventions targeting CU traits and co-occurring conduct problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Callous–unemotional (CU) traits mark a subgroup of children with conduct problems that are most at risk of developing serious forms of antisocial behavior. Elevated levels of CU traits in childhood account for unique variance in the prediction of later antisocial outcomes, over and above influences of competing disruptive behaviors; such as symptoms of conduct disorder (CD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [1]. Accordingly, CU traits have significance in the conceptualization of etiological and diagnostic models of conduct problems [2]. Modeled on the affective-interpersonal dimension of adult psychopathy, CU traits are characterized by a lack of regard for other people’s feelings, deficient guilt associated with wrongdoing, and restricted emotionality. Children and adolescents displaying these interpersonal-affective features manifest a unique profile of impairments across social, cognitive, and emotional domains of functioning; and evidence more frequent, severe, and varied aggressive behavior [3]. Despite its overlap with conduct problems, CU traits are a distinct risk-related feature in children [4].

There is evidence for a reasonable degree of stability of CU traits across development [5, 6], and a genetic component to the development of these traits [7]. Notwithstanding this, CU traits are proving to be malleable in childhood. Recent studies are beginning to show that CU traits—and co-occurring conduct problems—respond to some psychosocial interventions [8–12]. Interestingly, a few of the interventions that have been successful in ameliorating CU traits/conduct problems across treatment, have tailored the regimen to fit with the presenting problems of the referred child and his/her family [8–10]. Although specific details regarding these adaptations for CU traits have only been documented in one of these past studies [8], these findings highlight the value of personalizing family-based interventions for conduct-problem children where high levels of CU traits may be present. In this light, it is important to investigate theoretically informed dimensions of family functioning that may be associated with CU traits in conduct-problem children, which may inform the design of future prevention and treatment programs targeting these traits and associated problem behavior.

Prior studies have demonstrated relationships between negative parenting behavior and CU traits, in both children and adolescents. For instance, a growing body of research suggests that harsh and ineffective parenting practices may be related to high levels of CU traits, both concurrently and over time [6, 13–15]. There is also some evidence to suggest that CU traits might provoke more harsh and aversive responding from parents [13, 16]. Moreover, improvements in harsh and inconsistent parenting mediated the effects of a behavioral parenting intervention on levels of CU traits [11]. Therefore it appears that dimensions of parents’ goal-directed practices, specifically their responding to child misbehavior and management of discipline, may have some influence on the development and/or maintenance of CU traits across childhood.

The quality of the parent–child relationship appears to be another dimension of family functioning associated with CU traits. Past studies have found significant links between higher levels of CU traits and more difficult parent–child relationships [14, 17], and child attachment disturbances [18–20]. Moreover, for children elevated on CU traits, parental warmth is negatively associated with their conduct problems [19]. Thus, together these studies provide evidence that CU traits may interfere with, and/or be affected by, the emotional tone of the parent–child relationship. This is in line with findings from developmental research demonstrating the significance of a positive parent–child emotional connection for the development of conscience in children with a CU-like temperament; that is, low fearful arousal [21].

While the aforementioned body of work indicates that children with high CU traits experience more negative parenting and poorer quality parent–child relationships, what is less understood, however, are the specific ways in which parents socialize such children about emotions. For example, how do parents of children elevated on CU traits interpret and respond to their child’s experience and expression of affect? Considering that conduct-problem children with CU traits demonstrate significant interpersonal deficits in their emotional functioning, and that parents play a fundamental role in socializing the ways in which children understand, experience, express, and regulate emotions [22]; it is surprising that the topic of parental emotion socialization in the families of children with CU traits has received very limited attention from researchers. Thus, the purpose of the present research is to examine emotion socialization styles in parents of high CU children. Below we will delineate the particular emotion-related characteristics of children with elevated CU traits, and then we will discuss theory and prior research on parental emotion socialization, and its significance for children manifesting these traits.

Children with CU traits display several core emotional deficits that potentially undermine healthy social interactions. First, CU traits are related to empathy deficits, particularly impairments in sharing in another’s feelings (i.e., affective empathy) [23, 24]. In preadolescents, these traits may also be associated with difficulties in understanding another’s feelings (i.e., cognitive empathy) [24]. Second, previous findings suggest that children high on CU traits show less physiological responsivity to others’ distress [25]. Third, children with elevated CU traits evidence emotion recognition deficits. That is, children with these traits appear to have relative difficulties recognizing other people’s displays of fear and sadness, as communicated via facial expressions [26], tone of voice [27], and body gestures [28]. Thus, in terms of their impaired emotional functioning, children with CU traits are less likely to recognize and respond to others’ negative emotions.

Notwithstanding these deficits, results from a recent observational study suggest that children with elevated levels of CU traits may have intact emotional expression. In a sample of 3–9 year-old conduct-problem boys and their parents, instances of verbal emotional expression were coded during a family emotional reminiscing task [29]. Against the authors’ predictions, results showed that children high on CU traits made more references to negative feelings during conversations with their caregivers. According to a panel of child psychologists, their emotional displays were not judged to be less genuine than those shown by their low CU peers. While these findings do not speak to the possibilities that children with high CU traits are better able to switch on and off their emotions, and that they might experience less arousal associated with particular emotions (as suggested by the evidence reviewed above), they do suggest that these children may not be deficient in showing, and communicating about, emotions in the family. To our knowledge, we are unaware of any previous research examining how caregivers respond to high CU children when they are emotional or verbalizing feelings.

As noted above, parents play a significant role in shaping children’s emotional lives. One of the most powerful ways in which parents socialize children about emotions, relates to how they appraise and consequently respond to child affect [22]. Gottman et al. [30] have distinguished between parents’ emotion socialization styles that are either supportive/coaching or dismissing of emotions. “Emotion-coaching” parents are validating and accepting of child affect, encourage their child’s expression of both positive and negative emotions, and see emotions in their children as opportunities for intimacy and teaching. Conversely, “emotion-dismissing” parents are invalidating of child affect and encourage avoidance or minimization of emotions, particularly involving negative feelings; and have a tendency to want to fix or change these emotions quickly. Parents’ thoughts and feelings about emotions; that is, their meta-emotion philosophy, are thought to influence their emotion socialization practices [22, 30]. Relative to other parenting dimensions (e.g., harsh discipline), individual differences in parents’ emotion socialization styles appear to be more subtle, and share only modest overlap with positive parenting practices and global measures of relationship quality, such as warmth [31]. The concept of parental meta-emotion philosophy is gaining increasing attention from researchers investigating family processes associated with children’s emotional and behavioral problems, and has recently been translated into a parenting intervention [32].

Past research regarding parental meta-emotion philosophy has demonstrated concurrent and longitudinal relationships between parents’ emotion socialization beliefs and practices and children’s internalizing, externalizing, and peer problems [33]. Previous studies that have investigated these relationships in clinic-referred children with disruptive behavior disorders (DBDs), have found parents’ coaching of emotions to be inversely associated with severity of behavioral problems [34], and less characteristic of the parents of conduct-problem children versus non-clinic controls [35]. Although some studies have not found a direct relationship between parents’ emotion socialization beliefs and conduct problems [36], prior results provide support for an indirect association wherein parental emotion coaching influences children’s emotional competence (e.g., affect regulation), which in turn is linked to severity of behavioral problems [33]. Regarding the negative aspects of parental emotion socialization, higher levels of parents’ dismissing of child emotion—as directly observed during family emotional conversations—have demonstrated relationships with elevated behavioral problems [37]. Thus, the current literature suggests that parents’ coaching and dismissing of emotions appear to be important for various child developmental processes and outcomes such as disruptive behavior.

As reviewed above, children with elevated CU traits appear to be less cognizant of, and responsive to, others’ emotions, but willing to discuss emotions in the family. Taking into account this pattern of emotional functioning, there are several reasons to suggest a potential link between parents’ style of emotion socialization and levels of childhood CU traits. As theorized by Gottman et al. [30], parents who label and ask questions of their child’s emotions may be scaffolding a greater awareness and understanding of emotions in their child, which is considered a building block for the development of empathy [38]. Moreover, from the perspective of social learning theory, parents who are less accepting and more dismissing of their child’s emotions, are less likely to provide a model of interpersonal behavior that values and considers emotions in other people. Therefore, it can be argued that parents’ style of emotion socialization beliefs and practices play an important role in shaping levels of CU traits in children. It is also important, however, to consider the potential influence of CU traits, or an underlying temperament characterized by low emotionality, on parents’ attempts at emotion socialization, considering previous findings on bi-directional associations between these personality features and dimensions of parenting [13]. Children who are either more manipulative or shallow in their expression of emotions, purportedly those with elevated CU traits, might provoke more dismissing behavior from parents in the context of emotional interactions. Similarly, the lack of guilt and remorse associated with CU traits might frustrate parents in their bids to socialize high CU children about emotions, leading to less positive and more negative emotion socialization practices over time.

The goal of the current research was to investigate emotion socialization beliefs and practices in the parents of children with elevated CU traits. Although past studies have demonstrated associations between CU traits and discipline-related parenting practices and global qualities of the parent–child relationship, there has been no prior examination of parents’ evaluations and reactions to emotional displays in high CU children (to our knowledge). Findings from this line of research have direct implications for tailoring novel interventions for conduct-problem children with CU traits, and will expand on the limited research investigating emotion-related parenting in the families of such children.

This paper reports on two separate studies that examined unique dimensions of parental emotion socialization in relation to childhood CU traits, using different methods and independent samples of families. In Study 1, parents reported on their thoughts and feelings about their own and their child’s emotions. In Study 2, parents’ emotion socialization practices—that is, their use of emotion coaching and dismissing behavior—were coded from direct observations of family interactions involving the discussion of past emotional experiences. In both studies, based on our rationale described above, we expected to find significant relationships between higher CU traits and a more negative pattern of parental emotion socialization beliefs and practices; including less coaching and acceptance of emotions, and more dismissing and disapproval of emotions. Considering that this was the first investigation of parents’ appraisals of and responding to child emotion in the families of children with CU traits, we did not make specific hypotheses for mothers and fathers. Moreover, the literature on fathers’ parenting behavior and CU traits is limited, and has produced mixed findings regarding the relative importance of fathers and mothers in the prediction of these traits [29, 39]. We also examined the potentially confounding effects of children’s externalizing symptoms, to confirm unique relationships between parental emotion socialization and levels of CU traits.

Study 1 Method

Participants

Participants were mothers (n = 108) and/or fathers (n = 81) of 111 elementary school age children. Children included 84 boys (75.7 %) and 27 girls (24.3 %) between the ages of 7 and 12 years (M = 9.58, SD = 1.60). Parent consent and child assent were obtained prior to collection of data, as was ethics approval from the IWK Health Centre Research Ethics Board. 81 % of children were Caucasian, 6 % were African-Canadian, and 13 % had various “Other” ethnic origins. Family annual income ranged from less than $10,000 to greater than $100,000, with a mean of $40,000–$50,000. Participants were recruited from local elementary schools, health care centers, and through local advertisements. All children were evaluated as part of the intake assessment for a summer day treatment and research program (STP) in Atlantic Canada. The majority of children met DSM-IV [40] diagnostic criteria for one or more DBDs, including ADHD only (n = 9), ODD/CD only (n = 2), or both ADHD and ODD/CD (n = 77). The remaining 23 children did not meet diagnostic criteria for ADHD, ODD or CD and were evaluated solely for research purposes.

Disruptive behavior disorder diagnoses were based upon several sources of information. First, symptom counts were computed for each child. Symptoms were considered present if they were endorsed by either parent or teacher on the Disruptive Behavior Disorders Rating Scale [41] or by parent response on the DSM-IV version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children [42]. Next, impairment was evaluated using parent and teacher ratings on the Impairment Rating Scale [43]. Finally, children were assigned a diagnosis if a sufficient number of symptoms were endorsed (using symptom count criteria specified in the DSM-IV) and if there was evidence of clinically significant impairment.

Measures

CU Traits

We used parent and teacher ratings on the Antisocial Process Screening Device (APSD) to measure CU traits. The APSD consists of 20 items rated on 0 (“not at all”) to 2 (“definitely true”) Likert scales [44]. After reverse scoring relevant items, parent and teacher ratings were combined on an item-by-item basis by taking the highest score across informant [45, 46]. The items were then summed to yield three scales, including the CU scale used in this study, and t-scores were computed using published sex-specific norms (Cronbach’s α = .76). The reliability and validity of the CU scale from the APSD has been well supported, as reported in the technical manual [44].

DBD Symptoms

The Disruptive Behavior Disorder Rating Scale (DBDRS) consists of 45 questions designed to measure DSM-IV symptoms of ADHD, ODD and CD using 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“very much”) Likert scales [41]. Parent and teacher ratings on the DBDRS were combined by taking the maximum (most deviant) score across informants. Combined data were then used to compute the frequency of conduct problem symptoms, defined as the sum of both ODD and CD symptoms (α = .93) and the frequency of ADHD symptoms, defined as the sum of both inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms (α = .98). Ratings of two (“pretty much”) or three (“very much”) were interpreted as indicating symptom presence. The reliability and validity of the DBDRS is well established in this and other samples [47, 48].

Parental Emotion Socialization Beliefs

The emotion-related parenting styles self-test (ERPSST) is a parent self-report scale designed to measure parents’ thoughts and feelings about their own and their child’s anger and sadness [49]. The ERPSST consists of 81 items, each of which is rated no (0) or yes (1). Based on Gottman et al. [30] conceptualization of emotion socialization styles, the ERPSST was designed to yield four scores: dismissive, disapproving, laissez-faire, and emotion coaching. To our knowledge, two studies have examined the psychometric properties (including the factor structure) of the ERPSST; one using community preschoolers [50], and the other using typically developing children and children with developmental disabilities (M = 5.92 years) [51]. Because our sample differed from those used in these previous studies (e.g., majority of children in our sample had a DBD and all were aged 7 years and over), rather than use the a priori scales, we computed parallel analysis and exploratory factor analysis (described below) and scored the measure based on these results. We had scores from both mothers and fathers on the ERPSST for 78 families.

Analytic Plan

Preliminary analyses showed that several items on the ERPSST questionnaire produced bivariate tables with empty cells, indicating that either the item had an extremely low base rate (less than 5 % of the sample endorsed one of the two possible responses) or that the item was redundant with other items. As recommended [52], these 21 items were dropped from the analyses (items 9, 23, 29, 30, 32, 34, 35, 40, 41, 44, 47, 52, 55, 62, 64, 65, 72, 73, 74, 75, 81). Three sets of analyses were computed with the remaining 60 items. First, parallel analysis based on minimum rank factor analysis was computed to determine the number of factors to extract from the ERPSST. Second, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was computed using unweighted least squares extraction and oblique (promin) rotation. These analyses were computed using FACTOR version 8.02 [53] based on polychoric correlations due to the dichotomous nature of the items. Third, based on EFA results, factor scores were computed and compared across mothers and fathers using SPSS version 18. To test our main hypotheses, the resulting parental emotion socialization variables were entered alongside potential confounds in multiple regression analyses, with multi-informant CU traits scores as the dependent variable.

Study 1 Results

Exploratory Factor Analysis

Parallel analysis suggested that four dimensions were related to variance larger than random variance. Based on this finding, a four-factor EFA was computed. Forty items were dropped because they did not load .30 or higher (explaining approximately 10 % of variance) on any factor. EFA results using the remaining 20 items are summarized in Table 1, along with means, standard deviations, and maximal reliability for the resulting scales. Maximal reliability is “…a quantitative index of the quality of measurement of a latent variable from a given set of indicators.” [54]. Because assumptions underlying Cronbach’s alpha (tau equivalence) are often not met for scales comprised of dichotomous items [55], maximal reliability is thought to be more appropriate than Cronbach’s alpha. The first factor—Disapproving of Emotion (DISAP)—included seven items that described parents who viewed children’s anger and sadness as unimportant or as manipulative. The second factor—Accepting of Emotion (ACCEPT)—included four items that described parents who were accepting and understanding of children’s anger and sadness. The third factor—Nonplussed by Emotion (NONP)—included four items that described parents who seemed confused and annoyed by their child’s and their own anger and sadness. The fourth factor—Reducer of Emotion (REDUCE)—included five items that described parents who viewed anger and sadness as conditions that needed to be changed quickly. Paterson et al. [51] reported a very similar factor structure in their 20-item shortened version of the ERPSST, comprising four scales: Emotion Coaching, Acceptance of Emotion, Rejection of Emotion, and Feelings of Uncertainty/Ineffectiveness in Emotion Socialization. The latter three scales were in line with ACCEPT, DISAP, and NONP, respectively; with some overlap in item content between the corresponding scales.

Mother and Father Comparisons on Emotion Socialization Beliefs

Mother and father scores were compared using a series of one-way ANOVAs, with informant (mother vs. father) as a repeated measures factor. These analyses used the subset of participants who had ratings from both mothers and fathers (n = 78). Mothers and fathers differed significantly on DISAP, F(1, 77) = 8.49, p = .005, and on NONP, F(1, 77) = 9.55, p = .003, but not on the other scales. Examination of means and standard deviations (see Table 2) and computation of standardized mean difference effect sizes (Cohen’s d) showed that fathers were more disapproving (d = .35) of and nonplussed (d = .38) by emotions.

Bivariate Associations among Parental Emotion Socialization Beliefs, Child Disruptive Behavior, and CU Traits

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics for children’s DBD symptoms (i.e., CP and ADHD symptoms) and CU traits, and parental emotion socialization variables; as well as the bivariate correlations among these variables. Higher scores on DBD symptoms and CU traits were significantly associated with lower levels of mothers’ acceptance of emotions, and higher levels of mothers’ nonplussed by emotions. Only DBD symptoms evidenced significant (positive) associations with levels of mothers’ reducer of emotions. Mothers’ disapproving did not relate to child behavior. For fathers, only one significant association was observed: higher levels of fathers’ reducer of emotions were linked to higher CP symptoms. The significant relationships between parental emotion socialization beliefs and DBD symptoms were in expected directions and in line with results from some previous studies [34, 35], and provide support for the convergent validity of this study’s brief version of the ERPSST.

Unique Relationships Between Parental Emotion Socialization Beliefs and CU Traits

We then examined independent associations between parental emotion socialization variables and CU traits in multiple regression, controlling for age, sex, and DBD symptoms. Income and race did not significantly relate to CU traits scores, therefore were not considered potential covariates. The results of the regression analyses are displayed in Table 3. In mothers, consistent with our predictions, lower levels of acceptance of emotions were uniquely associated with higher CU traits scores, and there was a trend (p = .07) towards a positive relationship between nonplussed by emotions and CU traits. In the separate regression equation examined for fathers, there were no unique associations between paternal emotion socialization variables and CU traits; only conduct problem symptoms demonstrated a unique (positive) relationship with levels of these traits.

Study 2 Method

Participants

Participants were 59 boys aged 3–9 years (M = 5.85; SD = 1.83) and their mothers (n = 59) and fathers (n = 49). This study was approved by the University of New South Wales (UNSW) ethics board, and participant consent was obtained prior to data collection. We have previously reported on other measures from this sample in one prior study [29]. Children were community referred to the UNSW Child Behaviour Research Clinic (CBRC) in Sydney, Australia, for assessment and treatment of conduct problems. Diagnoses were based on DSM-IV [40] criteria using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, Adolescents, and Parents (DISCAP) [56]; a semi-structured, diagnostic interview, which was administered to parents. Children received a primary diagnosis of either ODD (97 %) or CD (3 %); comorbid diagnoses included ADHD (29 %) and anxiety disorders (7 %). Interrater agreement for primary diagnoses among a team of psychologists/psychiatrists was good (Cohen’s kappa = .79). The majority of children were from Anglo-European families (95 %), with other children having Asian, Pacific Islander, and Latin American ethnic origins. 78 % of children lived in two-parent families. Parents’ highest education level attained ranged from: 4 years of secondary school (mothers: 7 % and fathers: 7 %), to 6 years of secondary school (mothers: 3 % and fathers: 7 %), to technical/skills-based tertiary education (mothers: 56 % and fathers: 58 %), to university education (mothers: 34 % and fathers: 28 %).

Measures and Procedure

Child Behavior

We used the UNSW system of combining items taken from APSD subscales (i.e., CU Traits, Impulsivity, and Narcissism) and Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) [57] subscales (i.e., Prosocial Behavior, Conduct Problems, Hyperactivity, Emotional Problems, and Peer Problems) to form factors for CU traits, conduct problems, hyperactivity, anxiety, and peer problems [5]. This measurement system has been extensively evaluated in community [13] and clinic [58] samples. Regarding the assessment of CU traits, Dadds et al. [5] demonstrated an improvement in reliability obtained from this amalgamated measure, compared to using the APSD-CU scale alone. There was satisfactory to good reliability for all five scales, across mothers (range α = .63–.85), fathers (range α = .62–.80), and teachers (range α = .74–.90). In line with previous studies conducted at the UNSW CBRC [8, 19, 29, 39, 58], parent and teacher reports were combined using a hybrid categorical/continuous rating method. First, scores on the five scales were split into ‘high’ (top third) and ‘low’ categories within each informant group (i.e., mothers, fathers, and teachers). Second, a multi-informant score for each scale was determined by computing the percentage of reporters that classified a child as ‘high’ on the scale. Dependent on the number of informant reports available, possible final scores were: 0, 33.3, 50, 66.7, and 100 %. Reports were available from 95 % of mothers, 81 % of fathers, and 78 % of teachers. Although peer problems related to the number of missing reporters (r = .31, p = .02), the final multi-informant scores for the remaining four scales did not correlate with the corresponding number of missing informants (range r = −.14–.09, all p’s > .05). Moreover, final scores for the five scales significantly correlated with respective scores across each informant group (range r = .45–.79; all p’s < .05).

Parental Emotion Socialization Practices

Families were observed during a 10-min emotional reminiscing task, wherein parents and referred child were instructed to talk about: “a happy time that you have all shared together and a sad time that you have all shared together”. Similar tasks have been used to code various dimensions of family emotional communication in past research involving school-aged children [37, 59]. Families’ conversations were transcribed verbatim and randomly checked for accuracy by a senior research assistant. Both video-clips and transcripts were used for coding frequencies of parental emotion coaching and dismissing.

Based on guidelines developed by Shields, Lunkenheimer, and Reed-Twiss [60], we coded emotion coaching as parents’ statements and questions that validated or labeled child negative emotion and encouraged the child to reflect on his affect (e.g., “How did you feel about that?” and “I could see that you were sad”), and/or helped problem solve around emotions (e.g., “What could you have done to feel less upset?”). Dismissing included statements (e.g., “You were silly to be upset about that” and “That’s not how you felt”) and behavior (e.g., eye-rolling and sighing) that criticized, minimized, or ignored child emotion [60]. Two postgraduate psychology students were trained on the coding methods, passed a pre-coding reliability exam, and met regularly throughout the coding phase to control for coder’s drift. Coders were blind to children’s CU traits scores and all other diagnostic information. 25 % of the families were re-coded by an independent coder to examine interrater reliability. Intraclass correlations were strong for both emotion coaching (mothers = .95; fathers = .98) and dismissing (mothers = .96; fathers = .78).

Study 2 Results

Bivariate Associations Between Parental Emotion Socialization Practices and Child Behavior

Table 4 shows descriptive statistics for child behavior variables and parental emotion coaching and dismissing; as well as their bivariate associations. As reported in a previous observational study [37], scores for parental dismissing were positively skewed. CU traits scores tended to be positively correlated with other dimensions of behavioral problems, however, no statistically significant associations were observed. Mothers’ coaching and dismissing of emotions were significantly positively correlated, as were mothers’ and fathers’ dismissing scores. Results revealed one significant association between the parent and child variables: mothers with higher frequencies of emotion dismissing had sons rated higher on CU traits.

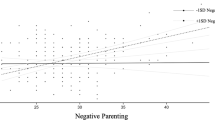

Unique Relationships Between Parental Emotion Socialization Practices and CU Traits

Due to the skewed data for parental dismissing, we examined unique associations between parents’ coaching and dismissing of emotions and CU traits by calculating bootstrap estimates of confidence intervals of the regression coefficients with 1,000 resamples. Bootstrapping is a nonparametric approach to statistical inference that does not make a priori assumptions about a sampling distribution (e.g., does not necessitate a normal distribution of scores for a given variable), and empirically derives its sampling distribution from the study’s data [61].

Age was included as a covariate in the analyses; there were no significant associations between CU traits and the demographic variables reported earlier, and child behavioral/emotional problems. The bootstrap estimates are presented in Table 5. For mothers, consistent with this study’s hypotheses, greater frequencies of emotion dismissing were significantly associated with higher CU traits scores (CI95 = .03, .53). For fathers, there were no significant relationships between emotion socialization practices and CU traits scores. To further evaluate the robustness of these findings, we re-computed these analyses including all the other dimensions of child behavioral/emotional problems (as reported in Table 4) as potential covariates. The positive association between frequencies of mothers’ dismissing of emotion and CU traits scores remained significant (Estimate = .29; SD = .15; CI95 = .02, .58).

Discussion

The aim of this research was to examine emotion socialization styles in the parents of children with high levels of CU traits. To this end, we reported on results from two independent, yet complementary studies that assessed unique dimensions of parental emotion socialization. In Study 1, parents of a combined clinic-referred and community sample of children reported on their thoughts and feelings regarding their own and their child’s anger and sadness. In Study 2, we coded parents’ emotion coaching and dismissing behavior from direct observations of family interactions involving the discussion of past emotional experiences, in a clinic sample of conduct-problem children. Across both studies, we expected the parents of children with high CU traits to demonstrate a more negative pattern of emotion socialization beliefs and practices, including less coaching and acceptance of emotions, and more dismissing and disapproval of emotions.

The current findings provide support for our hypotheses. In our first study, we found that mothers of children rated higher on CU traits tended to have affective attitudes that were less accepting of children’s experience and expression of emotions. This finding was independent of the effects of the severity of children’s disruptive behavior and did not overlap with the other scales of maternal emotion socialization beliefs. There were no significant associations involving fathers’ emotion socialization attitudes. In our second study, we observed that mothers of higher CU children were more likely to dismiss instances of children’s verbal expression of emotion. This finding remained significant after accounting for the potential effects of other dimensions of child problematic behavior, suggesting a unique association between this element of emotion socialization and CU traits. As in Study 1, no significant associations were identified for fathers’ responding to child emotion.

The findings from these studies converge to suggest that the mothers of children with high levels of CU traits have a more negative emotion socialization style, characterized by less acceptance and more dismissing of children’s experience and expression of emotions. Fathers’ emotion socialization styles appear to be unrelated to CU traits. Interestingly, the pattern of emotion socialization beliefs and practices observed in the mothers of high CU children, also seems to co-occur in some parents of typically developing children. Based on self-reports of parents’ emotion-related beliefs and behavior, Wong et al. [62] found that parents who are less accepting of their child’s negative emotions, react in more nonsupportive ways to these emotional displays, involving behavior that is punitive and minimizing of child emotion. This is consistent with the idea that parents’ thoughts and feelings about emotions influence the way in which they respond to child emotion [22, 30], which provides a reasonable explanation for the pattern of findings observed here.

Our results are in line with those from a growing body of research suggesting that dimensions of parent–child interaction may be implicated in the development and/or maintenance of levels of CU traits in children. For instance, past studies have reported links between CU traits and the quality of parental behavior management [13, 15] and the parent–child relationship [14, 17, 63]. In the one previous study that has examined emotion-related parenting behavior, mothers’ frequency of communication about negative emotions was found to be inversely related to conduct problem severity in children with high levels of CU traits [29]. Here we extend on these past studies by providing the first evidence of a relationship between CU traits and the style in which parents appraise and respond to children’s experience and expression of emotions. Taken together, results from this line of inquiry suggest that the quality of parental responding to both children’s behavior and emotions are linked to levels of CU traits.

Our results also fit with recent findings suggesting an association between disorganized attachment and higher levels of CU traits [18, 19]. The manner in which parents respond to child emotion plays an important role in defining the type and quality of attachment a child develops towards his or her caregiver, such that children with parents who are less sensitive and attuned to their emotions, are at greater risk of developing a disrupted attachment. Moreover, the emotional processing deficits associated with CU traits, may predispose parents of children elevated on these traits to significant challenges throughout their task of emotion socialization. Thus, it is likely that the affective interactions between high CU children and their parents involve some degree of reciprocated dysfunction that is manifesting as disruptions at both the level of parenting (e.g., impaired responding to child emotion) and child functioning (e.g., disorganized attachment).

The finding that mothers of high CU children are less likely to accept, and more inclined to dismiss, their child’s emotions is consistent with the lack of regard these children have for others’ affect. CU traits are purportedly underpinned by a temperament characterized by low emotional arousal. Thus, the combination of a predisposition towards low emotionality and a style of parenting that is disregarding of emotion, would seem to be particularly conducive to the development of an interpersonal-affective style that is less focused on other people’s feelings and lacking in moral emotions, such as guilt. Considering that, relative to their low CU peers, conduct-problem children high on CU traits do not appear to be deficient in expressing emotional language with their caregivers [29], mothers’ disregard for emotions might not be impairing their willingness to openly discuss feelings in the family. This is somewhat consistent with the suggestion that conduct problems in high CU children are less influenced by coercive parental responding to this behavior, including harsh discipline and criticism [58, 64, 65].

Across both studies we did not find evidence for any significant relationships between fathers’ emotion socialization beliefs and practices and levels of CU traits. Although this could be due to limited power to detect significant effects associated with the lower number of fathers relative to mothers in both studies, the size of the correlations still suggest weaker relationships for fathers. Research with typically developing children, however, suggests that fathers’ emotion socialization style may influence areas of children’s emotional functioning; including their processing and expression of emotion [66, 67]. It should also be noted that levels of CU traits appear to be associated with relational aspects of fathers’ behavior, such as warmth [58] and frequency of eye contact [39]. Considering the current findings and that there has been very limited research on paternal behavior in relation to CU traits in general, it will be an important endeavor for future research to continue to investigate the differential importance of mothers’ and fathers’ emotion socialization styles as predictors of levels of CU traits.

Along with the consistency in the results between both the studies reported here, our findings are strengthened by several methodological and design characteristics of this research. Namely, the use of multiple informants (i.e., mother, father, teacher) to rate child CU traits and behavior, unique methods (i.e., self-reports and direct observations) to assess two distinct dimensions of parents’ emotion socialization style, and the use of independent and heterogeneous samples (i.e., community and clinic children) to test our hypotheses.

There are also several noteworthy limitations of this research. First, the self-report measure of parents’ thoughts and feelings about emotions in Study 1 only referenced anger and sadness. CU traits have been linked to specific deficits in recognizing others’ distress (i.e., fear and sadness). Thus, it would have been valuable to have included a measure of parents’ affective attitudes towards fear as well. However, in Study 2 we directly observed parents’ emotion coaching and dismissing behavior in relation to all negative emotions expressed by children. Second, our use of slightly different assessments of CU traits in Study 1 (APSD-CU subscale) and 2 (combination of items from APSD and SDQ subscales) may be considered a limitation. Third, the reliability for at least one ERPSST subscale in Study 1 was suboptimal. However, the reliabilities for the ERPSST measure were consistent with scales with other published, widely-used scales, such as the CU scale from the APSD, and the fact that the correlations (see Table 2) were in expected directions suggests reliability was not a major concern for this study. Two previous studies have provided evidence for the reliability and validity of the ERPSST in parents of young children [50, 51]. The four scales empirically derived in Study 1 were very similar—in terms of both item content and reduction—to the factor structure reported in a recent study examining a shortened version of the ERPSST [51]. Despite this, the brief measure identified here would benefit from further psychometric evaluation in studies using larger samples of both clinic-referred and community children, spanning both early and middle childhood.

Fourth, our results reflect correlations that do not necessarily imply causation. Moreover, considering that various facets of parent–child interaction relate to CU traits, future longitudinal research should examine which particular dimensions (e.g., parental behavior management, relationship-based, and emotion-related) independently predict levels of childhood CU traits over time. Previous results demonstrate only modest correlations between parents’ emotion socialization style and other parenting behavior (e.g., warmth) [31], and unique associations between parental emotion socialization and child behavioral and emotional problems controlling for alternative aspects of parenting behavior [68]. Thus, there is reason to speculate that the significant dimensions of parental emotion socialization uncovered in the current research may be uniquely predictive of CU traits over and above behavior-oriented parenting practices and global qualities of the parent–child relationship.

Finally, considering that the majority of families in both Study 1 and 2 were Caucasian/Anglo-European, our results may not generalize to other samples that include a greater diversity in ethnicity. For instance, past research suggests that, in comparison to other ethnic groups, African American families tend to use less emotion coaching and are less emotion focused in their interactions [35, 69]. Further research is needed to examine relationships between parents’ emotion socialization style and CU traits using more ethnically diverse samples.

The current findings have significant implications for family-based intervention programs targeting CU traits and associated problem behavior. Parent management training (PMT) is considered best practice for the treatment of childhood behavioral problems, and although appears to be having some success in reducing CU traits, there are still children with elevated levels of such traits that may respond less well to this traditional intervention [8, 70, 71]. Given what we now know about the heterogeneity of conduct problems, it is timely to develop and trial novel interventions that are specifically suited to conduct-problem children displaying a callous interpersonal style. In a recent clinical trial, Dadds et al. [8] examined the efficacy of an emotion-recognition training adjunct to standard PMT, in a sample of children with complex presentations of behavioral/emotional disorders. For the children rated high on CU traits at baseline, this novel treatment significantly improved their levels of affective empathy, and decreased conduct problem behavior, in comparison to standard PMT.

The added value of training parents in emotional communication during PMT has received support in meta-analytic research [72]. Our results further support this line of thinking regarding parenting interventions for CU traits and conduct problems in children. That is, such interventions should fuse training in behavioral management skills with consultation on building emotional communication and relationship enhancement skills. The findings here specifically suggest focusing on the way parents socialize children about emotions, particularly with respect to their affective attitudes and practices regarding children’s emotions. Recent treatment studies demonstrate that parents can improve on various aspects of their emotion socialization practices in the context of interventions that also target child behavioral problems [32, 73].

Summary

Past research has shown that various dimensions of parent–child interaction, including qualities of parents’ disciplinary behavior and the parent–child relationship, are associated with levels of CU traits in children. Here we extend on this body of research, by demonstrating in two independent studies with unique methodologies, that the style in which parents appraise and respond to child emotion is related to the severity of CU traits. Specifically, mothers of children rated higher on CU traits appear to have emotion socialization beliefs and practices that are less accepting, and more dismissing, of child emotion. These findings highlight the importance of targeting parents’ responding to both child behavior and emotions in family-based interventions for children with CU traits and co-occurring conduct problems.

References

McMahon RJ, Witkiewitz K, Kotler JS (2010) Predictive validity of callous–unemotional traits measured in early adolescence with respect to multiple antisocial outcomes. J Abnorm Psychol 119(4):752–763

Frick PJ (2012) Developmental pathways to conduct disorder: implications and future directions in research, assessment, and treatment. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 41(3):378–389

Frick PJ, White SF (2008) Research review: the importance of callous–unemotional traits for developmental models of aggressive and antisocial behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 49(4):359–375

Viding E, McCrory EJ (2012) Why should we care about measuring callous–unemotional traits in children? Br J Psychiatry 200(3):177–178

Dadds MR, Fraser J, Frost A, Hawes DJ (2005) Disentangling the underlying dimensions of psychopathy and conduct problems in childhood: a community study. J Consult Clin Psychol 73(3):400–410

Frick PJ, Kimonis ER, Dandreaux DM, Farell JM (2003) The 4 year stability of psychopathic traits in non-referred youth. Behav Sci Law 21(6):713–736

Viding E, Larsson H (2010) Genetics of child and adolescent psychopathy. In: Salekin RT, Lynam DT (eds) Handbook of child and adolescent psychopathy. Guilford Press, New York, pp 113–134

Dadds MR, Cauchi AJ, Wimalaweera S, Hawes DJ, Brennan J (2012) Outcomes, moderators, and mediators of empathic-emotion recognition training for complex conduct problems in childhood. Psychiatry Res 199(3):201–207

Hyde LW, Shaw DS, Gardner F, Cheong J, Dishion TJ, Wilson M (2012) Dimensions of callousness in early childhood: links to problem behavior and family intervention effectiveness. Dev Psychopathol. Advanced online publication

Kolko DJ, Dorn LD, Bukstein OG, Pardini D, Holden EA, Hart J (2009) Community vs. clinic-based modular treatment of children with early-onset ODD or CD: a clinical trial with 3-year follow-up. J Abnorm Child Psychol 37(5):591–609

McDonald R, Dodson MC, Rosenfield D, Jouriles EN (2011) Effects of a parenting intervention on features of psychopathy in children. J Abnorm Child Psychol 39(7):1013–1023

Somech LY, Elizur Y (2012) Promoting self-regulation and cooperation in pre-kindergarten children with conduct problems: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 51:412–422

Hawes DJ, Dadds MR, Frost ADJ, Hasking PA (2011) Do childhood callous–unemotional traits drive change in parenting practices? J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 40(4):507–518

Pardini DA, Lochman JE, Powell N (2007) The development of callous–unemotional traits and antisocial behavior in children: are there shared and/or unique predictors? J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 36(3):319–333

Waller R, Gardner F, Hyde LW, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN (2012) Do harsh and positive parenting predict parent reports of deceitful-callous behavior in early childhood? J Child Psychol Psychiatry 53(9):946–953

Salihovic K, Kerr M, Ozdemir M, Pakalniskiene V (2012) Direction of effects between adolescent psychopathic traits and parental behaviors. J Abnorm Child Psychol 40(6):957–969

Schneider WJ, Cavall TA, Hughes HN (2003) A sense of containment: potential moderator of the relation between parenting practices and children’s externalizing behaviors. Dev Psychopathol 15(1):95–117

Bohlin G, Eninger L, Brocki KC, Thorell LB (2012) Disorganized attachment and inhibitory capacity: predicting externalizing problem behaviors. J Abnorm Child Psychol 40(3):449–458

Pasalich DS, Dadds MR, Hawes DJ, Brennan J (2012) Attachment and callous–unemotional traits in children with early-onset conduct problems. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. Advanced online publication

Sonuga-Barke EJ, Schlotz W, Kreppner J (2010) V. Differentiating developmental trajectories for conduct, emotion, and peer problems following early deprivation. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 75(1):102–124

Kochanska G (1997) Multiple pathways to conscience for children with different temperaments: from toddlerhood to age 5. Dev Psychol 33(2):228–240

Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL (1998) Parental socialization of emotion. Psychol Inq 9(4):241–273

Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous X, Warden D (2008) Physiologically-indexed and self-perceived affective empathy in conduct-disordered children high and low on callous–unemotional traits. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 39:503–517

Dadds MR, Hawes DJ, Frost ADJ, Vassallo S, Bunn P, Hunter K et al (2009) Learning to ‘talk the talk’: the relationship of psychopathic traits to deficits in empathy across childhood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 50(5):599–606

de Wied M, van Boxtex A, Matthys W, Meeus W (2012) Verbal, facial, and autonomic responses to empathy-eliciting film clips by disruptive male adolescents with high versus low callous–unemotional traits. J Abnorm Child Psychol 40(2):211–223

Dadds MR, Perry Y, Hawes DJ, Merz S, Riddell AC, Haines DJ et al (2006) Attention to the eyes and fear-recognition deficits in child psychopathy. Br J Psychiatry 189(3):280–281

Blair RJR, Budhani S, Colledge E, Scott S (2005) Deafness to fear in boys with psychopathic tendencies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 46(3):327–336

Muñoz LC (2009) Callous–unemotional traits are related to combined deficits in recognizing afraid faces and body poses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 48(5):554–562

Pasalich DS, Dadds MR, Vincent LC, Cooper A, Hawes DJ, Brennan J (2012) Emotional communication in families of conduct-problem children with high versus low callous–unemotional traits. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 41(3):302–313

Gottman JM, Katz LF, Hooven C (1996) Parental meta-emotion philosophy and the emotional life of families: theoretical models and preliminary data. J Fam Psychol 10(10):243–268

Katz LF, Gottman JM, Hooven C (1996) Meta-emotion philosophy and family functioning: reply to Cowan (1996) and Eisenberg (1996). J Fam Psychol 10(10):284–291

Havighurst SS, Wilson KR, Harley AE, Prior MR, Kehoe C (2010) Tuning into Kids: improving emotion socialization practices in parents of preschool children—findings from a community trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 51(12):1342–1350

Katz LF, Maliken AC, Stettler NM (2012) Parental meta-emotion philosophy: a review of research and theoretical framework. Child Dev Perspect 6(4):417–422

Dunsmore JC, Booker JA, Ollendick TH (2012) Parental emotion coaching and child emotion regulation as protective factors for children with oppositional defiant disorder. Soc Dev. Advanced online publication

Katz LF, Windecker-Nelson B (2004) Parental meta-emotion philosophy in families with conduct-problem children: links with peer relations. J Abnorm Child Psychol 32(4):385–398

Ramsden SR, Hubbard JA (2002) Family expressiveness and parental emotion coaching: their role in children’s emotion regulation and aggression. J Abnorm Child Psychol 30(6):657–667

Lunkenheimer ES, Shields AM, Cortina KS (2007) Parental emotion coaching and dismissing in family interaction. Soc Dev 16(2):232–248

Baron-Cohen S, Golan O, Ashwin E (2009) Can emotion recognition be taught to children with autism spectrum conditions? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 364(1535):3567–3574

Dadds MR, Jambrak J, Pasalich D, Hawes DJ, Brennan J (2011) Impaired attention to the eyes of attachment figures and the developmental origins of psychopathy. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 52(3):238–245

American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th text revision ed: American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC

Pelham WE, Gnagy EM, Greenslade KE, Milich R (1992) Teacher ratings of DSM-III-R symptoms for the disruptive behavior disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 31(2):210–218

NIMH-DISC Editorial Board (1999) The National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children. Columbia University, New York

Fabiano GA, Pelham WE, Waschbusch DA, Gnagy EM, Lahey BB, Chronis AM et al (2006) A practical impairment measure: psychometric properties of the Impairment Rating Scale in samples of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and two school-based samples. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 35(3):369–385

Frick PJ, Hare RD (2001) Antisocial processes screening device: technical manual. Multi-Health Systems, Toronto

Piacentini JC, Cohen P, Cohen J (1992) Combining discrepant diagnostic information from multiple sources: are complex algorithms better than simple ones? J Abnorm Child Psychol 20(1):51–63

Bird HR, Gould MS, Staghezza BM (1992) Aggregating data from multiple informants in child psychiatry epidemiological research. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 31(1):78–85

Massetti GM, Pelham WE, Gnagy EM (2005) Situational variability of ADHD, ODD, and CD: psychometric properties of the DBD interview and rating scale for an ADHD sample. Poster presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Society for Research in Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, New York, NY

Wright KD, Waschbusch DA, Frankland BW (2007) Combining data from parent ratings and parent interview when assessing ADHD. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 29(3):141–148

Gottman JM, DeClaire J (1997) The heart of parenting: how to raise an emotionally intelligent child. Simon & Schuster, NY

Hakim-Larson J, Parker A, Lee C, Goodwin J, Voelker S (2006) Measuring parental meta-emotion: psychometric properties of the emotion-related parenting styles self-test. Early Educ Dev 17(2):229–251

Paterson AD, Babb KA, Camodeca A, Goodwin J, Hakim-Larson J, Voelker S et al (2012) Emotion-related parenting styles (erps): a short form for measuring parental meta-emotion philosophy. Early Educ Dev 23(4):583–602

Muthén B, Muthén LK (2009) Advance regression analysis, IRT, factor analysis and structural equation modeling with categorical, censored, and count outcomes. Mplus Short Course, Baltimore, MD. Johns Hopkins University

Lorezo-Seva U, Ferrando PJ (2006) FACTOR: a computer program to fit the exploratory analysis model. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 38(1):88–91

Willoughby MT, Pek J, Blair CB (2013) Measuring executive functioning in early childhood: a focus on maximal reliability and the derivation of short forms. Psychol Assess Advanced online publication

Graham JM (2006) Congeneric and (essentially) tau-equivalent estimates of score reliability: what they are and how to use them. Educ Psychol Meas 66(6):930–944

Holland D, Dadds MR (1997) The diagnostic interview schedule for children, adolescents, and parents. Griffith University, Brisbane

Goodman R (1997) The strengths and difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38(5):581–586

Pasalich DS, Dadds MR, Hawes DJ, Brennan J (2011) Do callous–unemotional traits moderate the relative importance of parental coercion versus warmth in child conduct problems? An observational study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 52(12):1308–1315

Fivush R, Marin K, McWilliams K, Bohanek JG (2009) Family reminiscing style: parent gender and emotional focus in relation to child well-being. J Cognit Dev 10(3):210–235

Shields AM, Lunkenheimer ES, Reed-Twiss I (2002) Family emotion coaching coding system. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI

Davison AC, Hinkley DV (1997) Bootstrap methods and their application. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Wong MS, McElwain NL, Halberstadt AG (2009) Parent, family, and child characteristics: associations with mother-and father-reported emotion socialization practices. J Fam Psychol 23(4):452–463

Kimonis ER, Cross B, Howard A, Donoghue K (2013) Maternal care, maltreatment and callous–unemotional traits among urban male juvenile offenders. J Youth Adolesc 42(2):165–177

Oxford M, Cavell TA, Hughes JN (2003) Callous/Unemotional traits moderate the relation between ineffective parenting and child externalizing problems: a partial replication and extension. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 32(4):577–585

Wootton JM, Frick PJ, Shelton KK, Silverthorn P (1997) Ineffective parenting and childhood conduct problems: the moderating role of callous–unemotional traits. J Consult Clin Psychol 65(2):301–308

Garner PW, Robertson S, Smith G (1997) Preschool children’s emotional expressions with peers: the roles of gender and emotion socialization. Sex Roles 36(11–12):675–691

McElwain NL, Halberstadt AG, Volling BL (2007) Mother-and father-reported reactions to children’s negative emotions: relations to young children’s emotional understanding and friendship quality. Child Dev 78(5):1407–1425

Duncombe ME, Havighurst SS, Holland KA, Frankling EJ (2012) The contribution of parenting practices and parent emotion factors in children at risk for disruptive behavior disorders. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 43(5):715–733

Gorman-Smith D, Tolan P, Henry DB, Florsheim P (2000) Patterns of family functioning and adolescent outcomes among urban African American and Mexican American families. J Fam Psychol 14(3):436–457

Hawes DJ, Dadds MR (2005) The treatment of conduct problems in children with callous–unemotional traits. J Consult Clin Psychol 73(4):737–741

Waschbusch DA, Carrey NJ, Willoughby MT, King S, Andrade BF (2007) Effects of methylphenidate and behavior modification on the social and academic behavior of children with disruptive behavior disorders: the moderating role of callous/unemotional traits. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 36(4):629–644

Kaminski JW, Valle LA, Filene JH, Boyle CL (2008) A meta-analytic review of components associated with parent training program effectiveness. J Abnorm Child Psychol 36(4):567–589

Salmon K, Dadds MR, Allen J, Hawes DJ (2009) Can emotional language skills be taught during parent training for conduct problem children? Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 40(4):485–498

Acknowledgments

This study was in part funded by grants from the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation, the IWK Health Centre, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, and the Australian Research Council. We are very appreciative of the children, parents, and teachers that kindly participated in this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pasalich, D.S., Waschbusch, D.A., Dadds, M.R. et al. Emotion Socialization Style in Parents of Children with Callous–Unemotional Traits. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 45, 229–242 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-013-0395-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-013-0395-5