Abstract

While a relationship has been identified between physical aggression and executive functioning within the adult population, this relationship has not yet been consistently examined in the adolescent population. This study examined the association between physical aggression towards others, self-reported depressive symptoms, and executive functioning within an adolescent inpatient sample diagnosed with a mood disorder. This study consisted of a retrospective chart review of 105 adolescent inpatients (ages 13–19) that received a diagnosis of a mood disorder (excluding Bipolar Disorder). Participants were grouped based on history of aggression towards others, resulting in a mood disorder with physically aggressive symptoms group (n = 49) and a mood disorder without physically aggressive symptoms group (n = 56). Ten scores on various measures of executive functioning were grouped into five executive functioning subdomains: Problem Solving/Planning, Cognitive Flexibility/Set Shifting, Response Inhibition/Interference Control, Fluency, and Working Memory/Simple Attention. Results from analyses of covariance indicated that there were no significant differences (p < .01) between aggression groups on any executive functioning subdomains. Correlation analyses (p < .01) indicated a negative correlation between disruptive behavior disorders and response inhibition/interference control, while anxiety disorders were negatively correlated with problem solving/planning. These findings provide important information regarding the presence of executive dysfunction in adolescent psychiatric conditions, and the specific executive subdomains that are implicated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mood Disorders and Aggression in Childhood and Adolescence

Pediatric mood disorders, typically defined as mood disorders that develop between early childhood and late adolescence [1], have been identified as one of the most common diagnoses for childhood psychiatric and general hospitalizations [2, 3]. Specifically, the 2006 population rate of child and adolescent psychiatric hospitalizations at a general hospital due to a mood disorder was at 12.1 per 10,000 patients [2].

Aggressive behavior is a highly frequent reason for childhood psychiatric hospitalizations [4], with researchers reporting that up to 50 % of child inpatients engage in physical aggression during their hospitalization [3]. The engagement in aggressive behavior has significant long-term consequences [5], with those who lack impulse control and display impulsive aggressive behaviors at risk for engaging in stimulating or “thrill-seeking” activities such as criminal behavior, as well as at risk for dropping out of school [6]. The presence of externalizing behaviors in children and adolescents not only negatively impacts the young person’s ability to function, but also causes significant difficulties for families, schools, and communities [7].

Aggressive behavior and disruptive behavioral presentations are very heterogeneous in nature and are often associated with a range of psychiatric conditions, including behavioral, attention, and mood disorders [4, 8, 9]. In addition, the presentation of a mood disorder is often accompanied by co-morbid behavioral and attention disorders [10], with depressive symptoms, a core symptom of a group of mood disorders, considered a potential predictor of violence and aggression in children [11].

Executive Functioning and Aggression

Executive functioning (EF) has been defined as a heterogeneous set of neurocognitive abilities involving cognitive flexibility, problem solving, response inhibition, working memory, fluency, and the planning and organization of behavior [12–16]. Executive functions have direct neural correlates, predominantly the dorsolateral and ventrolateral regions of the prefrontal cortex, while also including orbitofrontal cortex, thalamus, striatum, and the basal ganglia. [16–19]. In addition, the dorsal and ventral regions of the prefrontal cortex, as well as the amygdala and angular gyrus have been associated with the engagement in violent and aggressive behavior [20]. A history of aggression has also been associated with decreased volume of the left orbital frontal cortex [21]. These findings suggest that given their shared neural correlates (e.g., prefrontal and orbitofrontal cortices), it might be expected to see an association between aggression and executive functioning.

Intact EF has been found to be a moderator between emotional distress or temperament and the engagement in physical aggression, assisting in the inhibition of aggression [22, 23]. In contrast, it has been suggested that without intact EF, individuals may not possess the reasoning and inhibition required for appropriate problem solving; instead, relying on violence or aggression in response to a given problem [24–26].

Within the adult literature, executive dysfunction has been associated with the presence of physically aggressive behavior in community, college, prison, and psychiatric inpatient samples [6, 21, 23, 24, 27]. However, other studies have not found such a clear relationship between EF and physical aggression [28, 29]. Barkataki et al. [28] found that in adult incarcerated individuals, processing speed deficits, although not executive dysfunction were associated with violence. Stanford et al. [29] found that while physical aggression was related to executive dysfunction, it was only found in one subdomain of EF, specifically impulse control. In addition, when examining aggression within an adult inpatient setting, Serper et al. [26] found that executive dysfunction was strongly related to the engagement in aggressive behavior while at the hospital. Within this study, executive dysfunction also appeared to be an underlying mechanism in the presence of psychiatric symptoms.

Executive Functioning and Aggression in Adolescents

The development of the childhood brain undergoes significant changes during adolescence, notably in the development of the prefrontal functions [21]. Of note, those individuals with impaired or undeveloped frontal lobe function typically display limited behavioral control [30]. This suggests that especially during the period of adolescence, the ability to engage in adaptive behaviors may be highly dependent on the development of the frontal areas of the brain.

In studies examining community samples of adolescent males, a history of physical aggression has been associated with executive dysfunction [31, 32]. The presence of executive dysfunction has also been associated with greater likelihood of engaging in verbal aggression [25]. Cauffman et al. [33] found that in the adolescent prison setting, poor performance on tasks of spatial working memory was associated with decreased self-control, with impaired self-control identified as a predictor of violent behavior. The findings from this study suggested that poor performance on tasks of EF (spatial working memory) was predictive of the engagement in violent behavior. However, another study examined EF within conduct disorder (CD) and attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adolescents [34]. This study found no association between executive dysfunction and the presence of CD or ADHD. Most notably, the presence of aggressive behavior was not associated with executive dysfunction or verbal deficits.

Research has also suggested that the presence of both aggression and internalizing behaviors is associated with different self-regulation mechanisms than those involved in aggression without internalizing behaviors [7, 35]. Specifically, those externalizing and internalizing children showed hyper alert threat-oriented activation [35] as well as a range of withdrawal, over control, and impulsivity symptoms [7]. This suggests that the self-regulation system of those individuals with aggression and a co-morbid psychiatric condition may be unique and therefore, important to study.

Present Study

While the adult research has established a relationship between physical aggression and executive functioning, this relationship has not yet been consistently identified in the adolescent population. In addition, the adult research has shown a relationship between aggression and executive functioning within the psychiatric inpatient population [26], while there has been no literature examining physical aggression and EF within the adolescent inpatient population. There is also a dearth of literature examining the relationship between physical aggression and EF within mood disorders.

The present study is a continuation of recent and yet to be published research that examined the association between executive functioning and self-reported depressive symptoms within an adolescent inpatient setting. In order to contribute to the examination of physical aggression and EF, this study examined the relationship between recent history of physical aggression towards others and performance on measures of EF within an adolescent inpatient sample diagnosed with a mood disorder. It was hypothesized that a recent history of aggression towards others would be associated with executive dysfunction, exhibited in significantly lower scores on measures of executive functioning. Given research indicating a potential association between depressive symptoms and aggression [11], it was also hypothesized that there would be positive correlation between self-reported depressive symptoms and the presence of recent physical aggression.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

This study followed the ethical principles of the American Psychological Association and received Institutional Review Board approval from Butler Hospital [36].

This study is part of a research project examining neuropsychological correlates of psychiatric conditions in adolescents at Butler Hospital, an inpatient psychiatric hospital. The data was gathered by retrospective chart review for inpatient adolescents who participated in a combined psychological/neuropsychological assessment between the years of 2002–2012. A clinical child neuropsychologist, a professional psychometrist, or a doctoral student in clinical psychology under direct supervision of a child neuropsychologist conducted assessments.

All hospitalized adolescents receive an admitting diagnosis and a discharge diagnosis by their attending psychiatrist (or psychiatry resident under supervision of attending psychiatrist), based on the diagnostic criteria of the DSM-IV-TR [37]. However, not all adolescents participate in a psychological/neuropsychological assessment. Referrals for evaluation are based on the parent/guardian concerns and/or a request for additional information by the attending psychiatrist. Assessments are typically completed within a few days of the hospital admission.

The present study focused on the relationship between physical aggression towards others and performance on measures of executive functioning in those inpatients diagnosed with a mood disorder. Inpatients diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder, a psychotic disorder, or a pervasive developmental disorder (e.g., Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Disorder, Rett’s Disorder, Childhood Disintegrative Disorder or Pervasive Developmental Disorder—Not Otherwise Specified [NOS]) were not included in this study. The sample consisted of 105 adolescent inpatients (ages 13–18) that received a discharge diagnosis of a mood disorder: Major Depressive Disorder (n = 22; 21 %), Dysthymic Disorder/Depressive Disorder NOS (n = 28; 27 %) or Mood Disorder NOS (n = 55; 53 %). 49 (47 %) inpatients were identified as having a recent history of physical aggression towards others, while 56 (53 %) inpatients were identified as having no recent history of physical aggression towards others. There was also a high prevalence of psychiatric co-morbidity in the sample. Clinical and demographic differences between groups was identified either using Chi squared or analyses of variance (ANOVA). Results are provided in Table 1.

Materials

Indication of Physical Aggression Towards Others

Information regarding the presence of physically aggressive symptoms was gathered directly from the patient’s chart. At the time of the hospital admission, detailed information was obtained by clinicians regarding recent behaviors exhibited by patients, including behaviors related to their level of safety. This included information on the presence of physical and verbal aggression towards one’s self, towards property, and towards others during the events immediately prior to hospitalization. Incidents included in the physical aggression towards others category involved acts of physical aggression towards another individual that could have or did cause significant harm. Therefore, documented acts of physical aggression towards others occurred immediately prior to hospitalization and were generally considered a significant component of the hospitalization.

Measures of Self-Reported Depression

The Childhood Depression Inventory (CDI) and the Scale 2 on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-Adolescent Edition (MMPI-A), measured adolescent self-reported depressive symptoms. The CDI has been shown to measure depressive symptoms such as negative mood, interpersonal problems, ineffectiveness, anhedonia, and negative self-esteem [38]. Scale 2 on the MMPI-A is one of ten clinical scales designed to assess various components of mental health. Scale 2 has been shown to measure depressive symptoms such as a lack of interest in activities, physical symptoms, and social difficulties [39]. Of note, all MPMI-A profiles were included in the present study based on research indicating that especially within the adolescent psychiatric inpatient setting, validity scales can represent true psychological distress, as opposed to an indication of invalid reporting [39].

Tasks of Executive Functioning

It was concluded that due to the significant heterogeneity of the term “executive functioning,” the executive functioning of participants should be examined based five core executive subdomains that have been repeatedly acknowledged in pediatric neuropsychology [13–16]. These included (1) Problem Solving/Planning, (2) Cognitive Flexibility/Set Shifting, (3) Response Inhibition/Interference Control, (4) Fluency, (5) Working Memory/Simple Attention. T Scores were reported for all measures of executive functioning. T Scores were obtained with the assistance of specific tool manuals as well as from resources providing normative data on relevant pediatric tools [13].

Problem Solving/Planning

The Rey Osterreith Complex Figure (ROCF) and the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) Categories score were used to represent the planning/problem-solving subdomain. The ROCF is a visual-spatial assessment tool, designed to assess planning, integration, and organizational abilities [40]. The WCST is a neuropsychological tool designed to assess a range of executive functions, including set shifting/cognitive flexibility, impulse control/interference control, abstraction, goal orientation, and problem solving [14–16, 40]. The WCST Categories score was used to assess planning/problem solving [14, 40].

Cognitive Flexibility/Set Shifting

The Trail Making Test (TMT) Form B and WCST Perseverative Errors score were used to assess set shifting/cognitive flexibility. The TMT is a two part task designed to assess components of attention, processing speed, and cognitive flexibility, with Form A assessing simple attention and Form B assessing complex attention and cognitive flexibility [14, 15, 40]. TMT Form B was included in the set shifting/cognitive flexibility subdomain, along with the Perseverative Errors score from the WCST [14, 40].

Response Inhibition/Interference Control

The Stroop Test Color–Word score and the WCST Failure to Maintain Set score were used to assess response inhibition/interference control [40]. The Stroop Test is a neuropsychological tool designed to assess attention, response inhibition, and resistance to distraction [14–16, 40]. The third Stroop condition, Color–Word (C–W), was the only score used in the current study. This is the most complex and demanding condition in the Stroop, designed to assess interference control and response inhibition.

Working Memory/Simple Attention

The wide range assessment of memory and learning (WRAML) Sentence Repetition score and TMT A were included in the working memory/simple attention subdomain [14, 40, 41]. The WRAML Sentence Repetition score is a verbally presented sentence repetition task, shown to assess working memory/simple attention [41, 42].

Fluency

Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT) is a verbal task that requires the patient to produce words based on clinician-delivered characteristics and is typically viewed as a task assessing executive functioning [14, 15, 40]. Two conditions were used in this administration, phonemic and semantic. The phonemic condition, FAS, asks the client to produce words starting with the letters F, A, S for 1 min per letter. The semantic condition, Animals, asks the client to say the names of various animals for 1 min. COWAT FAS and Animals comprise the fluency subdomain.

Results

Executive Functions

Composite scores were calculated for each executive functioning subdomain based on the mean performance of administered executive functioning measures for each individual: Cognitive Flexibility/Set Shifting (TMT B & WCST Perseverative Errors), Interference Control/Response Inhibition (Stroop C–W & WCST FMS), Problem Solving/Planning (ROCF & WCST Categories), Verbal Fluency (COWAT FAS & COWAT Animals), and Working Memory/Simple Attention (WRAML Sentences & TMT A). In addition, an Executive Functioning Composite was calculated based on all executive functioning measures.

Physical Aggression History and Executive Functioning

The sample of participants was dichotomized based on incidence of physical aggression towards others prior to hospitalization. Based on chart review, 49 participants were included in the mood disorder with physically aggressive symptoms group (47 %) and 56 participants were included in the mood disorder without physically aggressive symptoms group (53 %). This percentage of physical aggression is consistent with other research that reported 50 % of a child inpatient sample exhibited physical aggression during hospitalization [3].

Analysis of Covariance

Analyses of covariance were conducted in order to determine differences between aggression groups in executive functioning and self-reported depressive symptoms (CDI Total score). Prior to analyzing group differences, three variables needed to be controlled: Age (X2 = 5.6), ADHD (X2 = 10.07), and disruptive behavior disorders (X2 = 7.65), which all showed significant differences between aggression groups. To ensure that aggression contributed uniquely to the analysis, the variables Age, ADHD, and disruptive behavior disorder were entered into the analyses as covariates. In order to protect against repeated analyses, statistical significance was set at p < .01. There were no significant differences between aggression groups on any executive subdomains or self-reported depressive symptoms. Results are provided in Table 2.

Of note, there were significant diagnostic differences observed between aggression groups, specifically regarding Mood NOS and depressive disorders. These differences were not controlled for in the ANOVA because the original aim of the study was to examine aggression within a group of mood disorders, regardless of the specific type of mood disorder. Despite this, the differences between specific mood disorders were analyzed in the next section.

Correlations

Pearson and Point bi-serial correlations were conducted between executive/depressive measures and clinical/diagnostic presentation. Due to the significant diagnostic differences between aggression groups, the specific psychiatric diagnoses were included in the correlations. Statistical significance was set at p < .01 and diagnoses were coded as present or not present (1 = Diagnosis present; 0 = No diagnosis). There were no significant correlations between physical aggression and any executive functioning subdomains. There were also no correlations between physical aggression and depressive symptoms. Physical aggression was positively correlated with Mood Disorder NOS, ADHD, and disruptive behavior disorders, while depressive disorders were negatively correlated with physical aggression. Alternatively, depressive disorders were positively correlated (p < .01) with MMPI-A self-reported depressive symptoms, while Mood Disorder NOS was negatively correlated with MMPI-A depressive symptoms.

Neither type of mood disorder was associated with any executive functioning subdomains, although the presence of certain co-morbid conditions was associated with executive functioning. Specifically, anxiety disorders were negatively correlated with problem solving/planning, while disruptive behavior disorders were negatively correlated with response inhibition/interference control. In addition, Sex (1 = Female; 2 = Male) was negatively correlated with CDI responding, Results are provided in Table 3.

Discussion

The current study examined the association between a recent history of physical aggression towards others and performance on tasks of executive functioning. It also examined the association between depressive conditions/symptoms and physical aggression towards others. It is the first study to our knowledge that has examined the association between physical aggression and executive functioning within an adolescent inpatient setting. Results from the current study did not support our two main hypotheses; there was no association between executive functioning and aggression or between depressive conditions/symptoms and aggression. Despite this, there were important secondary findings regarding psychiatric conditions in adolescence and the role of executive functioning.

Results from ANOVA indicated no significant differences between aggression groups on performance on a range of tasks assessing various executive functioning subdomains. In addition, there was no significant correlation identified between physical aggression and any of the executive functioning subdomains. Taken together, this study did not identify a relationship between a recent history of physical aggression towards others and executive functioning in adolescent inpatients diagnosed with a mood disorder. These findings are inconsistent with research [31–33] that has identified executive dysfunction in the presence of physical aggression within the adolescent population. However, it is in line with one study that found no association between executive functioning and aggression within a sample characterized by psychiatric psychopathology [34]. In addition, the current findings did not find an association between aggression and self-reported depressive symptoms, which is somewhat inconsistent with past research [11]. It has also been suggested that there may be different self-regulation mechanisms in those children with co-morbid affective and externalizing conditions [7, 35]. Our lack of significant findings may represent the different neurocognitive and emotional involvement in aggressive behavior within those individuals with significant affective conditions.

Significant diagnostic differences between aggression groups were identified, notably in the type of mood disorder, as well as within disruptive behavior disorders (Conduct Disorder, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, and Disruptive Behavior Disorder NOS), anxiety disorders (Social Phobia, Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Anxiety Disorder NOS) and ADHD. In order to help elucidate this finding, a correlation analysis was conducted regarding the associations between executive functioning, aggression, depressive symptoms, and psychiatric diagnosis. One major finding was the significant clinical differences between Mood Disorder NOS and depressive disorders (Major Depressive Disorder, Dysthymic Disorder, and Depressive Disorder NOS). While Mood Disorder NOS was positively correlated (p < .01) with the presence of physical aggression, it was negatively correlated with self-reported depressive symptoms. Depressive disorders had the opposite profile, with a positive correlation with self-reported depressive symptoms and a negative correlation with physical aggression. While the experience of depressive symptoms is a core symptom criterion for depressive disorders, physical aggression is not a core symptom of Mood Disorder NOS [37]. Therefore, this finding sheds some light on the clinical characteristics of adolescents diagnosed with Mood Disorder NOS.

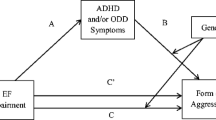

Another important finding to this study is the correlation between psychiatric diagnoses and executive functioning. Neither category of mood disorder (Mood Disorder NOS & depressive disorders) was correlated with executive functioning. However, certain co-morbid presentations were associated with executive dysfunction. Specifically, disruptive behavior disorders were negatively correlated with response inhibition/interference control, while anxiety disorders were negative correlated with problem solving/planning. Disruptive behavior disorders were also positively correlated with physical aggression, indicating that the presence of a disruptive behavior disorder is associated with physical aggression towards others and executive dysfunction in response inhibition/interference control. While no direct effect was found between physical aggression and executive functioning, the findings on disruptive behaviors partially supports our initial hypothesis regarding their relationship.

These findings suggest that while the type of primary mood disorder is not associated with executive dysfunction, the presence of an additional psychiatric condition may be associated with select executive dysfunction. This is consistent with research that has suggested that it may not be the presence of a psychiatric condition, but clinical factors such as the severity or co-morbidity of a psychiatric presentation that result in select neuropsychological impairments [43, 44]. The current study found impairments associated with comorbid psychiatric conditions, suggesting that the specific type of psychiatric condition may be particularly associated with certain executive functioning subdomains.

Despite the important findings, there are several limitations to this study. The first limitation was the dependence on chart review for assessing history of aggression. While the patients’ charts clearly identified the history of relevant behaviors including aggression, the data could not be coded on a continuum of aggressive actions. Rather, data was entered as either positive or negative for the presence of a history of aggression towards others. In addition, unlike other studies examining the executive functioning in inpatient physical aggression [26], this study did not use the presence of aggressive behaviors during the hospitalization as an indicator of physical aggression. Future studies would benefit from examining the presence of aggressive behaviors during hospitalization and obtaining more specific information on aggression history (e.g., a specific measure assessing aggressive behavior) when examining executive dysfunction within adolescent aggression.

Another limitation to this study is the fact that the adolescent inpatients with mood disorders were not compared with healthy controls on measures of executive functioning. While the objective of this study was to examine aggressive, depressive, and executive dysfunction symptoms within adolescent mood disorders, we understand the importance of comparing this population to healthy individuals. In addition, the information available for this study did not include clinical and demographic variables such as family education, patient education, or overall intelligence. Despite these limitations, we believe the comprehensive and subdivided executive functioning profile on an understudied population provided a strong contribution to the growing research in this area.

Future studies should continue to examine executive dysfunction within the adolescent inpatient setting. While this study provided some clarity regarding the executive functioning of this population, there is still a dearth of literature examining the neuropsychological abilities of inpatient adolescents. Future studies would benefit from implementing more specific criteria for assessing physical aggression in order to gain more detailed information on the association between aggression and executive dysfunction. In addition, it would beneficial to further examine specific clinical variables (e.g., diagnosis, depressive symptoms, aggressive symptoms) in relation to executive dysfunction, in order to identify those individuals who are at risk for executive dysfunction.

Summary

Aggressive behavior is a very common reason for childhood psychiatric hospitalization, although there is very little research examining the neurocognitive abilities of those adolescent inpatients with a history of aggression. Results from the current study did not identify an association between physical aggression and executive functioning. Mood Disorder NOS, disruptive behavior disorders, and ADHD were positively correlated with physical aggression, while depressive disorders were positively correlated with self-reported depressive symptoms. In addition, psychiatric co-morbidity to mood disorders was associated with select executive dysfunction. Notably, co-morbid disruptive behavior disorders were associated with lower response inhibition/interference control, while co-morbid anxiety disorders were associated with lower problem solving/planning. This provides important information regarding the neurocognitive implications of psychiatric conditions in adolescence, specifically identifying those executive subdomains that may be more susceptible to psychopathology and therefore may require more specific treatment.

References

National Institute of Mental Health (2001) Mood disorders in children and adolescents: an NIMH perspective. Biol Psychiatry 49:962–969

Lasky T, Krieger A, Elixhauser A, Vitiello B (2011) Children’s hospitalizations with a mood disorder diagnosis in general hospitals in the united states 2000–2006. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 5:1–9

Sukhodolsky DG, Cardona L, Martin A (2005) Characterizing aggressive and noncompliant behaviors in a children’s psychiatric inpatient setting. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 36:177–193

Rice BJ, Woolston J, Stewart E, Kerker BD, Horwitz SM (2002) Differences in younger, middle, and older children admitted to child psychiatric inpatient services. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 32:241–261

King S, Waschbusch DA (2010) Aggression in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Expert Rev Neurother 10:1581–1594

Villemarette-Pittman NR, Stanford MS, Greve KW (2002) Language and executive function in self-reported impulsive aggression. Pers Individ Differ 34:1533–1544

Stieben J, Lewis MD, Granic I, Zelazo PD, Segalowitz S, Pepler D (2007) Neurophysiological mechanisms of emotion regulation for subtypes of externalizing children. Dev Psychopathol 19:455–480

Greene RW, Biderman J, Zerwas S, Monuteaux MC, Goring JC, Faraone SV (2002) Psychiatric comorbidity, family dysfunction, and social impairment in referred youth with oppositional defiant disorder. Am J Psychiatry 159:1214–1224

Jacobs RH, Becker-Weidman EG, Reinecke MA, Jordan N (2010) Treating depression and oppositional behavior in adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 39:559–567

Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Merikangas KR (2001) Mood disorders in children and adolescents: an epidemiologic perspective. Biol Psychiatry 49:1002–1014

Ferguson CJ, Miguel CS, Hartley RD (2009) A multivariate analysis of youth violence and aggression: the influence of family, peers, depression, and media violence. J Pediatrics 155:904–908

Mahone EM, Slomine BS (2007) Managing dysexecutive disorders. In: Hunter SJ, Donders J (eds) Pediatric neuropsychological intervention. Cambridge University Press, New York

Anderson P (2002) Assessment and development of executive function (EF) during childhood. Child Neuropsychol 8:71–82

Baron IS (2004) Neuropsychological evaluation of the child. New York, Oxford University Press

Henry LA, Bettenay C (2010) The assessment of executive functioning in children. Child Adolesc Ment Health 15:110–119

Willcutt EG (2010) Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In: Yeates KO, Ris MD, Taylor HG, Pennington BF (eds) Pediatric neuropsychology: research, theory, and practice, 2nd edn. The Guilford Press, New York, pp 393–417

Collette F, Van der Linden M, Laureys S, Delfiore G, Degueldre C, Luxen A, Salmon E (2005) Exploring the unity and diversity of the neural substrates of executive functioning. Hum Brain Mapp 25:409–423

Koenigs M, Grafman J (2009) The functional neuroanatomy of depression: distinct roles for ventromedial and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Behav Brain Res 201:239–243

Ottowitz WE, Dougherty DD, Savage CR (2002) The neural network basis for abnormalities of attention and executive function in major depressive disorder: implications for application of the medical disease model to psychiatric disorders. Harv Rev Psychiatry 10:86–99

Miczek KA, de Almeida RM, Kravitz EA, Rissman EF, de Boer SF, Raine A (2007) Neurobiology of escalated aggression and violence. J Neurosci 27:11803–11806

Gansler DA, McLaughlin NC, Iguchi L, Jerram M, Moore DW, Bhadelia R, Fulwiler C (2009) A multivariate approach to aggression and the orbital frontal cortex in psychiatric patients. Psychiatry Res Neuroimag 171:145–154

Giancola PR, Roth RM, Parrott DJ (2006) The mediating role of executive functioning in the relation between difficult temperament and physical aggression. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 28:211–221

Sprague J, Verona E, Kalkhoff W, Kilmer A (2011) Moderators and mediators of the stress-aggression relationship: executive function and state anger. Emotion 11:61–73

Hancock M, Tapscot JL, Hoaken P (2010) Role of executive dysfunction in predicting frequency and severity of violence. Aggress Behav 36:338–349

Santor DA, Ingram A, Kusumakar V (2003) Influence of executive functioning difficulties on verbal aggression in adolescents: moderating effects of winning and losing and increasing and decreasing levels of provocation. Aggress Behav 29:475–488

Serper M, Beech DR, Harvey PD, Dill C (2008) Neuropsychological and symptom predictors of aggression on the psychiatric inpatient service. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 30:700–709

Barker ED, Tremblay RE, van Lier P, Vitaro F, Nagin DS, Assaad J-M, Seguin JR (2011) The neurocognition of conduct disorder behaviors: specificity to physical aggression and theft after controlling for ADHD symptoms. Aggress Behav 37:63–72

Barkataki I, Kumari V, Das M, Hill M, Morris R, O’Connell P, Taylor P, Sharma T (2005) A neuropsychological investigation into violence and mental illness. Schizophr Res 74:1–13

Stanford MS, Greve KW, Gerstle JE (1997) Neuropsychological correlates of self-reported impulsive aggression in a college sample. Pers Individ Differ 23:961–965

Golden CJ, Jackson ML, Peterson-Rohne A, Gontkovsky ST (1996) Neuropsychological correlates of violence and aggression: a review of the clinical literature. Aggress Violent Behav 1:3–25

Seguin JR, Pihl RO, Harden PW, Tremblay RE, Boulerice B (1995) Cognitive and neuropsychological characteristics of physically aggressive boys. J Abnorm Psychol 104:614–624

Seguin JR, Boulerice B, Harden PW, Tremblay RE, Pihl RO (1999) Executive functions and physical aggression after controlling for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, general memory, and IQ. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 40:1197–1208

Cauffman E, Steinberg L, Piquero AR (2005) Psychological, neuropsychological and physiological correlates of serious antisocial behavior in adolescence: the role of self-control. Criminology 43:133–175

Dery M, Toupin J, Pauze R, Mercier H, Fortin L (1999) Neuropsychological characteristics of adolescents with conduct disorder: association with attention-deficit-hyperactivity and aggression. J Abnorm Child Psychol 27:225–236

Lamm C, Granic I, Zelazo PD, Lewis MD (2011) Magnitude and chronometry of neural mechanisms of emotion regulation in subtypes of aggressive children. Brain Cognit 77:159–169

American Psychological Association (2002) Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. Am Psychol 57:1060–1073

American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn (Text Revision). Author, Washington, DC

Kovacs M (1992) Children’s depression inventory (CDI) manual. Multi-Health Systems, New York, NY

Archer RP (1992) MMPI-A: assessing adolescent psychopathology. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ

Strauss E, Sherman EM, Strauss O (2006) A compendium of neuropsychological tests: administration, norms and commentary, 3rd edn. Oxford University Press, New York

Burton DB, Donders J, Mittenberg W (1996) A structural equation analysis of the wide range assessment of memory and learning in the standardization sample. Child Neuropsychol 2:39–47

Sheslow D, Adams W (1990) WRAML: wide range assessment of memory and learning administration manual. Jastak Assessment Systems, Wilmington, DE

Baune BT, McAfoose J, Leach G, Quirk F, Mitchell D (2009) Impact of psychiatric and medical comorbidity on cognitive function in depression. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 63:392–400

Beblo T, Sinnamon G, Baune BT (2011) Specifying the neuropsychology of affective disorders: clinical, demographic and neurobiological factors. Neuropsychol Rev 21:337–359

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. George Tremblay at Antioch University New England for his integral statistical analysis guidance throughout this project. Without his guidance, the project would not have been possible. We would also like to thank the whole neuropsychology team at Butler Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Holler, K., Kavanaugh, B. Physical Aggression, Diagnostic Presentation, and Executive Functioning in Inpatient Adolescents Diagnosed with Mood Disorders. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 44, 573–581 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-012-0351-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-012-0351-9