Abstract

Advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) are elevated in aging and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and they can stimulate the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROSs) via NADPH oxidase, induce oxidative stress that lead to cell death. In the current study, we investigated the molecular events underlying the process that AGEs induce cell death in SH-SY5Y cells and rat cortical neurons. We found: (1) AGEs increase intracellular ROSs; (2) AGEs cause cell death after ROSs increase; (3) oxidative stress-induced cell death is inhibited via the blockage of AGEs receptor (RAGE), the down-regulation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase, and the increase of scavenging by anti-oxidant alpha-lipoic acid (ALA); (4) endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress was triggered by AGE-induced oxidative stress, resulting in the activation of C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) and caspase-12 that consequently initiates cell death, taurine-conjugated ursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA) inhibited AGE-induced ER stress and cell death. Blocking RAGE–NADPH oxidase, and RAGE–NADPH oxidase–ROSs and ER stress scavenging pathways could efficiently prevent the oxidative and ER stresses, and consequently inhibited cell death. Our results suggest a new prevention and or therapeutic approach in AGE-induced cell death.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A sugar molecule bonds to a protein or lipid molecule, a process called glycation, resulting in the formation of advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs), and this process is enzyme-independent. Studies indicated that intracellular AGEs can accumulate in endosomes or lysosomes, being a constituent of lipofuscin (Anzai et al. 2006; Kimura et al. 1995). In brains, AGEs may impair neurons through direct covalent cross linking to substrates (Yan et al. 1995). The extracellular AGEs can affect the neurons via the surface AGEs receptor, namely RAGE (Rahmadi et al. 2011). These receptors are expressed in various cell types such as astrocytes, microglias, endothelial cells, and neurons (Srikanth et al. 2011). In another paralleling study of ours, we found that AGE-BSA up-regulates RAGE in rat cortical neurons and SH-SY5Y cells in a dosage-dependent manner (Xu et al. 2012, in preparation). AGEs binding to cells can stimulate the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Urata et al. 2002).

ROSs such as oxygen ions and peroxides, highly reactive due to the presence of unpaired valence shell electrons, are essential intermediates in oxidative metabolism. ROSs play important roles in regulating multiple cellular functions in certain range of local concentration. Nonetheless, when generated in excess (oxidative stress), ROSs damage cells by peroxidizing lipids and disrupting structural proteins, enzymes, and nucleic acids (Dalton et al. 1999). The multicomponent enzyme 47 kDa cytosolic subunit (p47) of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase is a major source of ROSs in cells (Guimaraes et al. 2010; Bedard and Krause 2007). To counter the destructive roles of reactive intermediates or repair cell damages, cells express an array of anti-oxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), glutathione reductase (GR), and catalase (CAT). SOD converts superoxide anions to hydrogen peroxide, which is then transformed to water by GSH-Px or by CAT (Lin and Beal, 2006). Oxidative stress caused by the disruption of intracellular redox homeostasis has been proposed to be a potential mechanism for AGE-induced neuronal death (Watts et al. 2005; Loh et al. 2006). Some ROSs can even act as messengers through a phenomenon called redox signaling (Lin and Beal 2006). It has been shown that ROSs trigger ER stress (Hayashi et al. 2003; Xue et al. 2005). However, there is no direct link between AGEs and ER stress.

Apoptotic process is characterized by distinct morphological changes such as cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, cell-membrane blebbing, cell fragmentation (formation of apoptotic bodies), and phagocytosis of the cell remainings by macrophages (Duvall and Wyllie 1986). The cellular power plant mitochondria contain many pro-apoptotic proteins such as apoptosis inducing factor (AIF) and cytochrome C (Jeong and Seol 2008). When mitochondria are damaged in oxidative stress condition, cell death is initiated via a chain of reactions including the cleavage of the pro-enzyme of initiator caspase-9 into active form that in turn cleaves effector procaspase-3/7 (Caroppi et al. 2009; Jeong and Seol 2008).

ER is responsible for synthesizing, folding, and transporting nascent proteins (Nakayama et al. 2008). Exposure to ROSs resulted in the accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins in ER that triggers a series of responses termed unfolded protein response (UPR), and consequently apoptotic initiator C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) and cysteine-aspartic proteases (caspase)-12 were activated under sustained ER stress (Benavides et al. 2005; Kaufman 1999; Szegezdi et al. 2003, 2006; Nakagawa et al. 2000). The glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78) in ER acts as a molecular chaperone, and facilitates translocation of newly synthesized proteins to ER membrane (Lee 2001). GRP78 is activated when it is associated with unfolded proteins and signaling molecules are released (Xue et al. 2005). Under normal conditions, GRP78 interacts with double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase-like ER kinase (PERK), activated PERK phosphorylates the subunit of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 (eIF2α) to the phosphorylated form (p-eIF2α), then protein synthesis is inhibited to prevent further accumulation of unfolded protein in the ER (Harding et al. 1999; Xue et al. 2005). However, the detailed molecular events underlying AGEs-induced cell death are not clear.

To address the issues, we intervened AGES-induced cell responses in SH-SY5Y cells and rat cortical neurons with AGEs in the current study at following steps: blockage of RAGE at plasma membrane by RAGE-neutralizing anti-body (RAGE-ab) (Liu et al. 2010); inhibition of NADPH oxidase by diphenylene iodonium (DPI); increase of ROSs scavenging by alpha-lipoic acid (ALA); and alleviating ER stress by taurine-conjugated ursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA) (Chen et al. 2008a, b; Ozcan et al. 2006).

Materials and Methods

Materials

Pregnant Wistar rats were obtained from the Research Center of Experimental Animals in Shandong University. The SH-SY5Y cells were purchased from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) medium, B27 supplement, and Trizol one step RNA extraction kit were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium/Ham’s F12 medium were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Fetal ovine serum (FBS) was from Hyclone (Thermo, USA). Bovine serum aluminum (BSA), and AGE- BSA (10 mg/ml) were from Biovision (CA, USA). RAGE-ab was from Millipore (CA, USA). 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA), ALA, penicillin, streptomycin, DPI, and TUDCA were from Sigma (MO, USA). Anti-bodies against p-eIF2α and NADPH oxidase subunit p47phox were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (MA, USA), anti-body against GRP78 from Spring (CA, USA), anti-body against CHOP and caspase-12 were from Abcam (Hong Kong, China), anti-body against β-actin, and the associated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary anti-bodies were from Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology (Beijing, China). Polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane was from Biorad (CA, USA). Enhanced chemiluminescence kit was from Millipore (MA, USA). Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) Detection Kit and the assay Kit for malondialdehyde (MDA), GSH-Px, SOD, and CAT were from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China). Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit was from KeyGEN (Nanjing, China). The bicinchoninic acid (BCA) kit, DAPI and Hoechst 33342 were from Beyotime (Shanghai, China), the reverse transcription reaction system and random hexamers (TaKaRa Bio Inc, Shiga, Japan), caspase-9 and caspase-12 fluorometric assay kit (BioVision, Mountain View, CA).

Cells Culture and Treatment

Embryos were removed from pregnant Wistar rats at 17 or 19 days of gestation. The rat cortical cortice were dissected and digested with 0.125 % tryptase for 15 min at 37 °C. Digestion was ended with the proliferation growth medium composed of a 1:9 mixture of fetal bovine serum and DMEM, and 2 % B27 supplement. Then, the cells were dissociated mechanically with a pipette. The dispersed cells were plated on culture dishes (2.0 × 106 cells/ml) or 12-well plates (6.0 × 105cells/ml) (Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) coated with poly-d-lysine (5 lg/ml) at 37 °C in 95 % air and 5 % CO2 for 7 days. SH-SY5Y cells were cultured in DMEM/Ham’s-F12 containing 10 % fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, in a 37 °C humidified 5 % CO2 incubator. Cells were grown to 70–80 % confluence in 60-mm dishes and the media were replaced every fourth day.

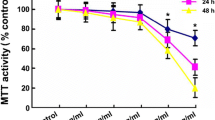

We recently tested different dosages of AGE-BSA for 48 h in both rat cortical neurons and SH-SY5Y cells, and we found that 200 μg/ml AGE-BSA in rat cortical neurons and 250 μg/ml in SH-SY5Y cells decreased about 50 % cell viability by MTT reduction assay as compared to the control group (Xu et al. 2012, in preparation). Thus, we treated the rat cortical neurons and SH-SY5Y cells with 200 or 250 μg/ml AGE-BSA for 48 h, respectively. The reagents for treatment were diluted in culture media. The treatments of rat cortical neurons were divided into six groups: (1) 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH7.4) 48 h (Control); (2) 200 μg/ml BSA 48 h; (3) 200 μg/ml AGE-BSA 48 h; (4) 10 μg/ml RAGE-ab 1 h, then treated with 200 μg/ml AGE-BSA 47 h (AGE + RAGE-ab); (5) 30 nM DPI 1 h, then treated with 200 μg/ml AGE-BSA 47 h (AGE + DPI), or 100 μM TUDCA 1 h, then treated with 200 μg/ml AGE-BSA 47 h (AGE + TUDCA); (6) 250 μM ALA 1 h, then treated with 200 μg/ml AGE-BSA 47 h (AGE + ALA).

Measurement of the Intracellular ROSs

After the pretreatment 1 h and treatment 47 h, the cultured cells were washed twice in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4), trypsinized and collected. Then cells were re-suspended in the PBS. 5 μM DCFH-DA was added into 0.5 ml cell suspension in 5 ml luminometer cuvettes. After incubation at 37 °C for 30 min, the cells were washed twice with 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4), and then analyzed using FACS Vantage flow cytometer with an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and an emission wavelength of 530 nm. Fluorescent signal intensity was examined with Cellguest software, the content of ROSs was assessed by the mean of fluorescence intensity.

Phosphatidylserine in Outer Plasma Membrane by FACS Analysis

The occurrence of phosphatidylserine in outer plasma membrane is a typical sign of apoptosis. Annexin V, a calcium dependent phospholipid-binding protein that has a high affinity for PS, is used as a sensitive probe for the exposure of PS on plasma membrane. Cells that are negative for both Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI) are considered as at viable stage, only positive for Annexin V-FITC as at early apoptotic stage, and positive for both Annexin V-FITC and PI as at late apoptotic stage. Cells were seeded into 6-well plate in triplicate for each group at a density of 1 × 105 cells/ml. Following the pretreatment 1 h and treatment for 47 h, cells were harvested and cell density was adjusted to 1 × 105/ml, then they were centrifuged at 300×g for 5 min. The supernatant was removed, and the cells were incubated in 5 μl of Annexin V, 195 μl of buffer and 20 μl of PI for 20 min in darkness. Then, 3 × 104 cells collected from each group were measured by the FACS Vantage flow cytometry at the excitation wavelength of 488 nm.

Assay for LDH Leakage

Plasma membrane may be damaged by toxic insults, then the LDH was released into culture medium. So, LDH release from cells was used as an indicator of necrosis (Li et al. 2012). In the assay, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) is reduced to NADH through the conversion of lactate to pyruvate by LDH, and NADH reduces tetrazolium into formazan dyes in the presence of diaphorase. Culture media and cells were separately harvested from each dish, and the cells were lysed in 2 % Triton X-100, then the supernatants and cell lysates were incubated with the appropriate reagent mixture according to the instructions at 37 °C for 30 min. After the reaction, samples were measured at wavelength 490 nm with UV 720 spectrophotometer. The percentage of LDH leakage was calculated as follows: LDH leakage = a/(a + b) × 100 %, where a is the absorbance read in culture media and b is absorbance read in cell lysates.

Morphological Characterization of Apoptosis by Hoechst 33342 Staining

Cells grown on coverslips in 12-well plate were fixed in 0.1 M PBS pH 7.4 containing 4 % paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature, and then were washed three times with 0.1 M PBS pH 7.4. In order to assess the possible morphological changes of apoptotic cells, Hoechst 33342 (5 μg/ml) was applied to cells for 6 min. Cells were washed and analyzed immediately under fluorescence microscopy. Apoptotic cells with bright blue fragmented nuclei indicating condensation of chromatin were identified.

Quantitative Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from individual cortex with Trizol onestep RNA extraction kit. The RNA, together with the control mRNA (1 μg) provided by the supplier, was reversely transcripted into cDNA using the reverse transcription reaction system and random hexamers, according to the manufactures’ instruction. The cDNA was subjected to a series of 10-fold dilutions with EASY dilution for the generation of standard curve. A total of 25 μl reaction containing 12.5 μl SYBR Premix Ex TaqTM (2×), 0.5 μl ROX reference dye (50×), 2 μl cDNA, 9 μl dH2O, 0.5 μl PCR forward and reverse primers (10 μmol/l, Shanghai Sangon Biological Engineering Technology Co, Shanghai, China) was denatured at 95 °C for 10 s and then subjected to 45 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 60–63 °C for 31 s in ABI PRISM 7000 HT (Invitrogen, California, USA). The sequences of PCR primers was 5′-GGC TTT GGT TCT CAT GGT AAC TTC A-3′ (sense) and 5′- AGG CCA TGG ATC CCT AAG CAG-3′ (anti-sense) for NADPH oxidase p47phox (119 bp) 5-TGG TGG ACC TCA TGG CCTAC-3′ (sense) and 5-CAG CAA CTG AGG GCC TCT CT-3′ (anti-sense) for GAPDH (105 bp). Standard curves for the target genes and internal reference gene were built under the same condition, and the cycle threshold values of the samples were used to calculate the corresponding gene copy number. The results were presented as the ratio of target gene copy over housekeeping gene (GAPDH) copy (Yamamoto et al. 2004).

Assays of SOD, MDA, GSH-Px and CAT

After the pretreatment 1 h and treatment 47 h, the cells were washed with ice-cold 0.1 M PBS pH 7.4 three times, then 106 cells were lysed in 0.1 M PBS pH 7.4 containing 5 μM EDTA, 0.1 % SDS, and homogenized for 20 min at 4 °C. Then, the homogenate was centrifuged at 2,000×g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were collected immediately and stored at −80 °C until use. The levels of MDA, GSH-Px, SOD, and CAT were determined by the assay kit according to the instruction. The SOD activity was analyzed by monitoring the inhibition of the reduction of nitro blue tetrazolium at 560 nm (Winterbourn et al. 1975). The MDA level was analyzed with 2-thiobarbituricacid (Placer et al. 1966). The GSH-Px activity was determined by 5-5′-dithiobis-p-nitrobenzoic acid (Hafemen 1974). The CAT activity was taken as the rate of decrease in absorbance of H2O2 at 240 nM/min/mg protein in the presence of CAT (Aebi 1984). All experiments were performed using three separate cultures to confirm reproducibility.

Caspase-9 and Caspase-12 Fluorometric Assay

The activity of caspase-9 and caspase-12 were detected with fluorometric assay kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, cells were suspended in 50 μl of chilled cell lysis buffer for 10 min. After 50 μl of reaction buffer (containing 10 mM DTT) and 5 μl of the acetyl-alanine-threonine-alanine-aspartic acid (ATAD)-7-amino-4-trifluoromethyl coumarin (AFC) substrate (50 μM) were added, cells were incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. Samples were then read in a fluorometer equipped with a 400-nm excitation filter and 505-nm emission filter. Caspase-9 and caspase-12 activity was expressed as arbitrary unit/g protein.

Protein Measurement and Western Blots

Cells were washed three times with ice-cold 0.1 M PBS pH 7.4 and proteins were lysed in the buffer (500 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 150 nM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM benzamiden, 1 μg/ml trypsin inhibitor) containing a cocktail of protease inhibitor (5 μl/ml) for 30 min at 4 °C. They were then centrifuged at 12,000×g for 30 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were collected and protein concentrations were determined with the BCA kit.

60 μg proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE gels, and transferred on PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5 % non-fat milk in TBST (100 mM Tris–HCl, 0.9 % NaCl, 0.5 % Tween-20) for 1 h, were incubated first with primary antibodies (rabbit polyclonal antibodies against NADPH oxidase p47phox and GRP78; mouse polyclonal antibodies against p-eIF2α and caspase-12) (1:1,000) overnight at 4 °C, and then with goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (1:5,000) for 1 h at 37 °C. Immunoreactions were enhanced by an enhanced chemiluminescence kit, then the bands were analyzed by the use of an image analyzer (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA, USA). Results were quantified by densitometry using the software Alphamager 2200 (AlphaInnotech Corporation, California, USA). The expression of target proteins was normalized to the level of β-actin.

Statistical Analysis

All values were reported as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Turkey–Kramer test for multiple groups comparison. The acceptable level for statistical significance was P < 0.05.

Results

Inhibition of AGE-Induced Intracellular ROSs by RAGE-ab, DPI, and ALA

AGE-BSA was shown to induce the production of ROSs via NADPH oxidase in murine hepatic stellate cells (Guimaraes et al. 2010). After AGE-BSA treatment, the intracellular ROSs levels were similar between control and BSA groups, AGE-BSA caused a rapid elevation of ROSs compared to the control, this change could be inhibited (>50 %) by the pretreatment of cells with RAGE-ab, ALA, or DPI as compared to AGE-BSA in both SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 1a) and rat cortical neurons (Fig. 1b).

Effects of AGE-BSA on intracellular ROS levels in SH-SY5Y cells (a) and rat cortical neurons (b). The DCFH-DA fluorescence was detected in 20 randomly selected cells in each experiment condition. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. *P < 0.01 compared with the controls, # P < 0.01 compared with the AGE-BSA group, △ P < 0.05 compared with the AGE-BSA group

Decrease of AGE-Induced Cell Death by RAGE-ab, ALA, and TUDCA

The cells only positive for FITC-Annexin V are considered as apoptotic cells at early stage. As shown in Fig. 2a (SH-SY5Y cells) and Fig. 2b (rat cortical neurons), ~15 % of the early apoptotic cells was observed in the AGE-BSA group, more than half of the early apoptotic cells were inhibited by the pretreatment of RAGE-ab, ALA, or TUDCA as compared to the AGE-BSA group.

Effects of AGE-BSA on cell death in SH-SY5Y cells and rat cortical neurons. Percentages of cells at early stage of apoptosis distinguished by positive Annexin V-FITC and negative Propidium iodide staining in different treatment conditions as compared to control in SH-SY5Y cells (a) and rat cortical neurons (b). Percentages of LDH leakage as compared to the control in different treatment conditions in SH-SY5Y cells (c) and rat cortical neurons (d). e apoptotic cells were visualized by Hoechst 33342 staining in rat cortical neurons (Magnification: ×400) a control; b BSA; c AGE-BSA; d AGE-BSA + RAGE-ab; e AGE-BSA + ALA; f AGE-BSA + TUDCA. Data were shown as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. *P < 0.01 compared with the controls, # P < 0.01 compared with the AGE-BSA group, △ P < 0.05 compared with the AGE-BSA group

Data from LDH release assay that estimates the degree of necrosis as shown in Fig. 2c, d demonstrated that in both SH-SY5Y cells and rat cortical neurons there was no difference between control and BSA group, AGE-BSA treatment significantly increased LDH leakage as compared with control. RAGE-ab, ALA, or TUDCA could significantly inhibit the LDH leakage induced by AGE approximately.

The nuclear morphology was assessed by staining SH-SY5Y cells with membrane-permeable blue Hoechst 33342 (Fig. 2e). In control and BSA groups (a, b), the cell nuclei were round or ellipse in shape. In contrast, many cells with smaller nuclei and condensed chromatin were seen in the AGE-BSA group (c), and RAGE-ab, ALA or TUDCA pretreatment could improve the AGE-induced morphological changes and decrease the number of apoptotic cells (d–f).

Data from the three methods suggested that RAGE-ab, ALA, or TUDCA prevents the cell death induced by AGEs.

Oxidative Stress and Cell Death

As shown in the panels a (SH-SY5Y cells) and b (rat cortical neurons) of Fig. 3, AGE-BSA treatment induced a dramatic increase of NADPH oxidase RNA and RAGE-ab pretreatment reduced the mRNA levels of NADPH oxidase induced by AGE. Data in the panels c (SH-SY5Y cells) and d (rat cortical neurons) of Fig. 3 showed ~3 times more of p47phox expression in AGE-BSA group as compared to the control and BSA groups, and the pretreatment of RAGE-ab could block ~30 % of the changes induced by AGE-BSA. The tendency is consistent with the qRT-PCR data (Panels a and b).

Effects of AGE-BSA on oxidative stress in SH-SY5Y cells or rat cortical neurons. mRNA levels of NADPH oxidase treated with AGE-BSA in SH-SY5Y cells (a) and rat cortical neurons (b) pretreated with RAGE-ab or not. Western blot analysis of NADPH oxidase in SH-SY5Y cells (c) and rat cortical neurons (d), pretreated with RAGE-ab or not. e, f effects of AGE-BSA on the activity of caspase-9 and the blocking effects of RAGE-ab, DPI, or ALA on the AGE-induced changes in SH-SY5Y cells (e) and rat cortical neurons (f). Effects of 200 μg/ml AGE-BSA on the levels of SOD, MDA, GSH-Px, and CAT, and the blocking effects of RAGE-ab, DPI, or ALA on the AGE-induced changes in rat cortical neurons (g, h, i, j). Data were shown as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. *P < 0.01 compared with the controls, # P < 0.01 compared with the AGE-BSA group, △ P < 0.05 compared with the AGE-BSA group

AGEs increased the activity of caspase-9, and it could be inhibited by RAGE-ab, DPI, or ALA in both SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 3e) and rat cortical neurons (Fig. 3f).

Data in the panels g, h, and i of Fig. 3 showed that AGEs reduced the activities of SOD, GSH-Px, and CAT in rat cortical neurons. In contrast, AGEs increased the level of MDA (panel j). All of these changes could be reversed by the pretreatment of cells with RAGE-ab, DPI, or ALA.

Oxidative stress, ER stress, and Cell Death

As shown in the panel a of Fig. 4, in rat cortical neurons, 200 μg/ml AGE-BSA induced increased levels of the two ER markers GRP78 and p-eEF2α in a time-dependent manner, with peak at 24 h. The apoptotic initiator markers CHOP and caspase-12 showed the highest level at 48 h. Based on the data from the panel a, the levels of GRP78 and p-eIF2α, and the levels of CHOP and caspase-12 were analyzed in cells treated with 200 μg/ml ASA-BSA for 24 and 48 h, respectively. The levels of GRP78 and p-eEF2α, and CHOP and caspase-12 were similar between control and BSA groups. However, the levels of the four markers in AGE-BSA group increased ~4 times as compared with the control, and the increase could be significantly blocked by the pretreatment of rat cortical neurons with RAGE-ab, DPI, or ALA (panels b, c, d, and e of Fig. 5). The trend was almost the same as in SH-SY5Y cells treated with 250 μg/ml AGE-BSA (not shown).

Effects of AGE-BSA on ER stress in rat cortical neurons. a western blot analysis of GRP78, p-eIF2α, CHOP, and caspase-12 with 200 μg/ml AGE-BSA treatment for 0, 12, 24, and 48 h. b Western blot analysis of GRP78 and p-eIF2α for 24 h, CHOP and caspase-12 for 48 h with or without the pretreatment of RAGE-ab, ALA, or TUDCA for 1 h. c–e the relative level of GRP78, p-eIF2α, CHOP, and activity of caspase-12 to that of β-actin. Data were shown as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. * P < 0.01 compared with the controls, # P < 0.01 compared with the AGE-BSA group, △ P < 0.05 compared with the AGE-BSA group

Discussion

Accumulation of AGEs is a symbolic feature of aging, and a significant increase of AGEs is also found in Alzheimer disease, diabetes, and other aging-related conditions (Rahmadi et al. 2011). AGEs can induce apoptosis in endothelial and neuronal cells through RAGE (Srikanth et al. 2011; Chen et al. 2009). The possible underlying molecular events in AGEs-triggered cell death were investigated in SH-SY5Y cells and rat cortical neurons in the current study.

DCFH-DA was used as a substrate for measuring intracellular oxidant production. Most recently, the toxic effect of AGEs was found to be caused via RAGE-induced ROSs production (Srikanth et al. 2011). Our results in the current study confirmed that AGEs-induced an increase of intracellular ROSs. This increase was found not only via RAGE, consistent to the above-mentioned study, but also via increased NAPDH oxidase activity and decreased scavenging of ROSs. Overproduction of ROSs is considered to induce the opening of the membrane permeability transition pore in mitochondria and release of apoptotic initiator such as caspase-9, leading to apoptosis (Tatton and Olanow 1999).

AGEs and RAGE were demonstrated to induce apoptosis in many cell types (Bucciarelli et al. 2002a, b; Srikanth et al. 2011; Chen et al. 2009). During apoptosis, the perturbation of plasma membrane could be reflected by the increased level of phosphatidylserine on outer plasma membrane labeled by Annexin V, and the increased leakage of LDH in culture media. This is true in both cell types: SH-SY5Y cells and rat cortical neurons. Conversion of phosphatidylserine from inner membrane to outer membrane (apoptosis) was found to be sensitive to the pretreatment of inhibitors, and the disturbance of cell membrane might contribute to the increased LDH level (necrosis) in culture media. The pretreatment of the inhibitors was shown to have less effect on necrosis as compared to apoptosis. The chromosome condensation could be distinguished under microscopy by the DNA changes visualized by fluorescent dye Hoechst 33342. Our results in the current study confirmed that AGEs can induce cell apoptosis. Furthermore, we found that AGEs-induced apoptosis can be inhibited by RAGE-ab, DPI or ALA, suggesting that RAGE, NADPH oxidase, and ROS scavenging are involved in the process of cell death.

MDA increase is an important indicator of toxic lipid peroxidation in oxidative stress (Ereeman and Crapo 1981). AGEs up-regulated the levels of ROSs and MDA, and decreased the activities of anti-oxidant enzymes (SOD, GSH-Px, CAT). RAGE, DPI, and ALA blocked the overproduction of ROSs and MDA, and decreased the activities of the anti-oxidant enzymes, suggesting that AGEs induce oxidative stress via RAGE and NADPH oxidase. ALA is a well-known efficient anti-oxidant in scavenging ROS. In the current study, the efficient scavenging role of ALA was consistently found.

Evidences have demonstrated that AGEs play an important role in the oxidative stress of vascular endothelial cells and murine hepatic stellate cells via RAGE–NADPH oxidase pathway (Guimaraes et al. 2010; Niiya et al. 2011; Thallas-Bonke et al. 2008). In the current study, we found that AGEs increase the expression of both the mRNA and protein levels of NADPH oxidase p47phox that are in turn blocked by RAGE-ab, confirming that NADPH oxidase is a downstream target of RAGE in AGE-induced ROSs pathway in SH-SY5Y cells and rat cortical neurons.

Studies showed that ER stress may play a crucial role in the development of neurodegenerative diseases (Nakagawa et al. 2000; Yoshida 2007), and ER stress may occur before neuronal cell death (Watts et al. 2005; Loh et al. 2006). Recently, a lot of studies revealed that oxidative stress contributes to ER stress (Yan et al. 2008; Xia et al. 2011; Chen et al. 2008a, b). In the current study, ER was stressed secondary to AGE-induced oxidative stress in SH-SY5Y cells and rat cortical neurons. GRP78 is a molecular chaperone only located in the ER; p-eEF2α and CHOP are important mediators of ER stress-induced cell death (Harding et al. 1999; Szegezdi et al. 2006). The sustained ER stress reminisced by the time delay of the occurrence of increased CHOP and caspase-12 as compared to that of ER markers GRP78 and p-eEF2α (48 to 24 h) (Harding et al. 1999; Yu et al. 1999; Hiramatsu et al. 2006) supported that activation of CHOP and caspase-12 are sequential events after the ER stress caused by oxidative stress (Benavides et al. 2005; Nakagawa et al. 2000).

Taken together, we have demonstrated that AGEs induce oxidative and ER stresses through activation of NADPH oxidase and reduction of ROSs scavenging, both of which were mediated by RAGE, resulting in cell death. We have also proved that AGE-induced oxidative stress contributes to ER stress, and the cell death induced by ER stress is involved by CHOP and caspase-12. Inhibiting both AGE–RAGE–NADPH-ROSs scavenging pathways and ER stress can lead to the prevention of cell death. The signaling pathway involved during AGE-induced apoptosis identified in the current study suggested that targeting RAGE, NADPH oxidase, ROSs scavenging, or ER stress may be a potential novel approach for the prevention of RAGE-induced neurodegeneration.

Abbreviations

- AGEs:

-

Advanced glycation endproducts

- ROSs:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- RAGE:

-

AGEs receptor

- NADPH:

-

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- ALA:

-

Alpha-lipoic acid

- ER:

-

Endoplasmic reticulum

- MDA:

-

Malondialdehyde

- SOD:

-

Superoxide dismutase

- GSH-Px:

-

Glutathione peroxidase

- GR:

-

Glutathione reductase

- CAT:

-

Catalase

- AIF:

-

Apoptosis inducing factor

- UPR:

-

Unfolded protein response

- GRP78:

-

Glucose-regulated protein 78

- eIF2α:

-

Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2

- RAGE-ab:

-

RAGE-neutralizing antibody

- DPI:

-

Diphenylene iodonium

- BSA:

-

Bovine serum aluminum

- CHOP:

-

C/EBP homologous protein

- DCFH-DA:

-

2′,7′-Dichlorofluorescein diacetate

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- PERK:

-

Double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase-like ER kinase

References

Aebi H (1984) Catalase in vitro. Method Enzymol 105:121–126

Anzai Y, Hayashi M, Fueki N, Kurata K, ohya T (2006) Protracted juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis-an autopsy report and immunohistochemical analysis. Brain Dev 28:462–465

Bedard K, Krause kH (2007) The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev 87:245–313

Benavides A, Pastor D, Santos P, Tranque P, Calvo S (2005) CHOP plays a pivotal role in the astrocyte death induced by oxygen and glucose deprivation. Glia 52:261–275

Bucciarelli LG, Wendt T, Qu W, Lu Y, Lalla E, Hofmann MA, Taguchi GA, Yan SF, Yan SD, Stern DM (2002a) RAGE blockade stabilizes established atherosclerosis in diabetic apolipoprotein E-null mice. Circulation 106:2827–2835

Bucciarelli LG, Wendt T, Rong L, Lalla E, Hofmann MA (2002b) RAGE is a multiligand receptor of the immunoglobulin superfamily: implications for homeostasis and chronic disease. Cell Mol Life Sci 59:1117–1128

Caroppi P, Sinibaldi F, Fiorucci L, Santucci R (2009) Apoptosis and human diseases: mitochondrion damage and lethal role of released cytochrome c as proapoptotic protein. Curr Med Chem 16:4058–4065

Chen G, Ma CL, Bower KA, Shi XL, Ke ZJ, Luo J (2008a) Ethanol promotes endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced neuronal death: involvement of oxidative stress. J Neurosci Res 86:937–946

Chen Y, Liu CP, Xu KF, Mao XD, Lu YB, Fang L, Yang JW, Liu C (2008b) Effect of taurine-conjugated ursodeoxycholic acid on endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis induced by advanced glycation end products in cultured mouse podocytes. Am J Nephrol 28:1014–1022

Chen J, Song M, Yu S, Gao P, Yu Y, Wang H, Huang L (2009) Advanced glycation endproducts alter functions and promote apoptosis in endothelial progenitor cells through receptor for advanced glycation endproducts mediate overpression of cell oxidant stress. Mol Cell Biochem 335:137–146

Dalton TP, Shertzer HG, Puga A (1999) Regulation of gene expression by reactive oxygen. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 39:67–101

Duvall E, Wyllie AH (1986) Death and the cell. Immunol Today 7:115–119

Ereeman BA, Crapo JD (1981) Hyperoxia increases oxygen radical production in rat lungs and lung mitochondria. J Biol Chem 256(10):986–992

Guimaraes EL, Empsen C, Geerts A, van Grunsven LA (2010) Advanced glycation end products induce production of reactive oxygen species via the activation of NADPH oxidase in murine hepatic stellate cells. J Hepatology 52:389–397

Hafemen DG (1974) Effect of dietary selenium on erythrocyte and liver glutathione peroxidase in the rats. J Nutr 104:580–587

Harding HP, Zhang Y, Ron D (1999) Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticullum-resident kinase. Nature 397:271–274

Hayashi T, Saito A, Okuno S, Ferrand-Drake M, Dodd RL, Nishi T, Maier CM, Kinouchi H, Chan PH (2003) Oxidative damage to the endoplasmic reticulum is implicated in ischemic neuronal cell death. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 23:1117–1128

Hiramatsu N, Kasai A, Hayakama K, Yao J, Kitamura (2006) Real-time detection and continuous monitoring of ER stress in vitro and in vivo by ES-TRAP: evidence for systemic, transient ER stress during endotoxemia. Nucl Acids Res 34(13):e93

Jeong SY, Seol DW (2008) The role of mitochondria in apoptosis. BMB Rep. 41:11–22

Kaufman RJ (1999) Stress signaling from the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum: coordination of gene transcriptional and translational controls. Genes Dev 13:1211–1233

Kimura T, Takamatsu J, Araki N, Goto M, Kondo A, Miyakawa T, Horiuchi S (1995) Are advanced glycation end-products associated with amyloidosis in Alzheimer’s disease? NeuroReport 6:866–868

Lee AS (2001) The glucose-regulated proteins: stress induction and clinical applications. Trends Biochem Sci 26:504–510

Li Q, Zhang Y, Sheng Y, Huo R, Sun B, Teng X, Li N, Zhu JX, Yang BF, Dong DL (2012) Large T-antigen up-regulates Kv4.3 K+ channels through Sp1, and Kv4.3 K+ channels contribute to cell apoptosis and necrosis through activation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochem J 441:859–867

Lin MT, Beal MF (2006) Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature 443:787–795

Liu YY, Liang C, Liu X, Liang B, Pan XM, Ren YS, Fan M, Li M, He ZQ, Wu JX, Wu ZG (2010) AGEs increased migration and inflammatory responses of adventitial fibroblasts via RAGE, MAPK and NF-κB pathways. Atherosclerosis 208:34–42

Loh KP, Huang SH, De Silva R, Tan BK, Zhu YZ (2006) Oxidative stress: apoptosis in neuronal injury. Curr Alzheimer Res 3:327–337

Nakagawa T, Zhu H, Morishima N, Li E, Xu J, Yankner BA, Yuan JY (2000) Caspase-12 mediates endoplasmic-reticulum-specific apoptosis and cytotoxicity by amyloid-beta. Nature 403:98–103

Nakayama H, Hamada M, Fujikake N, Nagai Y, Zhao J, Hatano O, Shimoke K, Isosaki M, Yoshizumi M, Ikeuchi T (2008) ER stress is the initial response to polyglutamine toxicity in PC12 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 377:550–555

Niiya Y, Abumiya T, Yamagishi S, Takino J, Takeuchi M (2011) Advanced glycation end products increase permeability of brain microvascular endothelial cells through reactive oxygen species–induced vascular endothelial growth factor expression. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 21(4):293–298

Ozcan U, Yilmaz E, Ozcan L, Furuhashi M, Vaillancourt E, Smith RO, Gorgun CZ, Hotamisligil GS (2006) Chemical chaperones reduce ER stress and restore glucose homeostasis in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Science 313:1137–1140

Placer ZA, Cushman LL, Johnson BC (1966) Estimation of product of lipid peroxidation, malindialdehyde in biochemical system. Anal Biochem 16:359–367

Rahmadi A, Steiner N, Münch G (2011) Advanced glycation endproducts as gerontotoxins and biomarkers for carbonyl-based degenerative processes in Alzheimer’disease. Clin Chem Lab Med 49:385–391

Srikanth V, Maczurek A, Phan T, Steele M, Westcott B, Juskiw D, Münch G (2011) Advanced glycation endproducts and their receptor RAGE in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 32:763–777

Szegezdi E, Fitzgerald U, Samali A (2003) Caspase-12 and ER-stress-mediated apoptosis: the story so far. Ann NY Acad Sci 1010:186–194

Szegezdi E, Logue SE, Gorman AM, Samali A (2006) Mediators of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. EMBO Eep 7:880–885

Tatton WG, Olanow CW (1999) Apoptosis in neurodegenerative disease: the role of mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta 1410:195–213

Thallas-Bonke V, Thorpe SR, Coughlan MT, Fukami K, Yap FYT, Sourris KC, Penfold SA, Bach LA, Cooper ME, Forbes JM (2008) Inhibition of NADPH oxidase prevents advanced glycation end product-mediated damage in diabetic nephropathy through a protein kinase C-α-dependent pathway. Diabetes 57:460–469

Urata Y, Yamaguchi M, Higashiyama Y, Ihara Y, Goto S, Kumano M (2002) Reactive oxygen species accelerate production of vascular endothelial growth factor by advanced glycation end products in RAW264.7 mouse macrophages. Free Radic Biol Med 32:688–701

Watts LT, Rathinam ML, Schenker S, Hender GI (2005) Astrocytes protect neurons from ethanol-induced oxidative stress and apoptotic death. J Neurosci Res 80:655–666

Winterbourn CC, Hawkins RE, Brian M, Carrell R (1975) The estimation of red cell suproxide dismutase activity. J Lab Clin Med 85:337–341

Xia Q, Feng XD, Huang HF, Du LY, Yang XD, Wang K (2011) Gadolinium-induced oxidative stress triggers endoplasmic reticulum stress in rat cortical neurons. J Neurochem 117:38–47

Xu S, Zhao Y, Yin QQ, Luo DZ, Hou XY, Yu BX, Hou L, Sun H, Wang MX, Liu XP (2012) Magnitude and mechanism of the effects of advanced glycation end-products of β-amyloid in rat cortical neurons and SH-SY5Y cells, in preparation

Xue X, Piao JH, Nakajima A, Sakon-Komazawa S, Kojima Y, Mori K, Yagita H, Okumura K, Harding H, Nakano H (2005) Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFalpha) induces the unfolded protein response (UPR) in a reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent fashion, and the UPR counteracts ROS accumulation by TNFalpha. J Biol Chem 280:33917–33925

Yamamoto Y, Maeshima Y, Kitayama H, Kitamura S, Takazawa Y, Sugiyama H, Yamasaki Y, Makino H (2004) Tumstatin peptide, an inhibitor of angiogenesis, prevents glomerular hypertrophy in the early stage of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes 53:1831–1840

Yan SD, Yan SF, Chen X, Fu J, Chen M, Kuppusamy P, Smith MA, Perry G, Godman GC, Nawroth P (1995) Non-enzymatically glycated tau in Alzheimer’s disease induces neuronal oxidant stress resulting in cytokine gene expression and release of amyloid beta-peptide. Nat Med 1:693–699

Yan MS, Shen JJ, person MD, Kuang XH, Lynn WS, Atlas D, Wong PKY (2008) Endoplasmic reticulum stress and unfolded protein response in atm-deficient thymocytes and thymic lymphoma cells are attributable to oxidative stress. Neoplasia 10:160–167

Yoshida H (2007) ER stress and diseases. FEBS J 274:630–658

Yu Z, Luo H, Fu W, Mattson MP (1999) The endoplasmic reticulum stress-responsive GRP78 protects neurons against excitotoxicity and apoptosis: suppression of oxidative stress and stabilization of calcium homeostasis. Exp Neurol 155:302–314

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30971036) and Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. Y2008C13).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yin, QQ., Dong, CF., Dong, SQ. et al. AGEs Induce Cell Death via Oxidative and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stresses in Both Human SH-SY5Y Neuroblastoma Cells and Rat Cortical Neurons. Cell Mol Neurobiol 32, 1299–1309 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10571-012-9856-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10571-012-9856-9