Abstract

Despite the central role culture plays in racial and ethnic disparities in mental health among ethnic minority and immigrant children and families, existing measures of engagement in mental health services have failed to integrate culturally specific factors that shape these families’ engagement with mental health services. To illustrate this gap, the authors systematically review 119 existing instruments that measure the multi-dimensional and developmental process of engagement for ethnic minority and immigrant children and families. The review is anchored in a new integrated conceptualization of engagement, the culturally infused engagement model. The review assesses culturally relevant cognitive, attitudinal, and behavioral mechanisms of engagement from the stages of problem recognition and help seeking to treatment participation that can help illuminate the gaps. Existing measures examined four central domains pertinent to the process of engagement for ethnic minority and immigrant children and families: (a) expressions of mental distress and illness, (b) causal explanations of mental distress and illness, (c) beliefs about mental distress and illness, and (d) beliefs and experiences of seeking help. The findings highlight the variety of tools that are used to measure behavioral and attitudinal dimensions of engagement, showing the limitations of their application for ethnic minority and immigrant children and families. The review proposes directions for promising research methodologies to help intervention scientists and clinicians improve engagement and service delivery and reduce disparities among ethnic minority and immigrant children and families at large, and recommends practical applications for training, program planning, and policymaking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 1977, Stanley Sue raised a serious concern about racial and ethnic disparities in mental health service use and treatment outcomes. More than three decades later, the Surgeon General (2001) echoed the same concern, exposing racial and ethnic disparities as an unrelenting and unresolved challenge. Despite decades of attention to the issue, ethnic and racial minority children and families continue to be less likely to access mental health services than their mainstream counterparts (Wang et al. 2005) and are more likely to delay seeking treatment and to drop out of treatment (Addis et al. 1999; Chorpita et al. 2002; Hoagwood et al. 2010; McKay et al. 2004). Contemporary thinkers have posited that racial and ethnic disparities in mental health services may result not only from logistical barriers, but also from the ubiquitous pressures of poverty and racism (Johnson et al. 2000), stigma associated with receiving mental health care (McCabe 2002), and lack of knowledge about mental health (McKay et al. 2004). The effects are particularly concerning: While there is variation among ethnic and cultural groups, ethnic minority children and families in general face additional sociocultural stressors, such as discrimination, acculturation, cultural isolation, and poverty, that may increase their risk for developing psychopathology and reduce service use despite need (Chorpita et al. 2002; Stormshak et al. 2005). The combination of increased risk for psychopathology and less use of services produces a double burden for these families, as well as increased healthcare costs for communities and the country as a whole.

Improving engagement in mental health treatment may be the key to solve these enduring problems. Examining key mechanisms of engagement that affect ethnic minority and immigrant children and families’ perceived need and utilization of mental health care may help to improve engagement. Better understanding of cultural and contextual factors specific to mental health service use may be critical in identifying some of those mechanisms and enhancing care for ethnic minority and immigrant children and families.

Emerging scholarship points to the centrality of culture in the contextualization of mental health problems among ethnic minorities (Bernal and Domenech-Rodríguez 2012). Although the definition of culture has been constantly debated among social scientists, it is largely agreed upon that culture has both the stability to define the boundary of a group and the flexibility to be transformed along with people’s everyday actions and interactions. In line with this, in this paper, we define culture as an intergenerationally transmitted system of meanings that encompasses values, beliefs, and expectations, including traditions, customs, and practices shared by a group or groups of people (Betancourt and López 1993). Culture shapes the very meaning of health and approaches to healing at multiple levels—from the individual’s beliefs, attitudes, and practices to the broader expectations, beliefs, and practices of families, communities, and cultures. For ethnic minority and immigrant children and families, the process of engaging in mental health treatment involves the complex challenge of navigating individual, familial, and culturally derived sets of beliefs, attitudes, and practices. Lau (2006) and Barrera and Castro (2006) underscore the need to empirically examine this indwelling effect of culture on the engagement process. However, limited empirical work has addressed ethnic and cultural factors that influence the treatment engagement process (Alegría et al. 2011; Cauce et al. 2002). Thus, better understandings of cultural and contextual factors specific to mental health service use may be critical in identifying key mechanisms of treatment engagement that can enhance care for ethnic minority children and families.

Our paper addresses this existing gap by proposing a conceptual framework of engagement for ethnic minority and immigrant children and families that is derived from a review of existing measures assessing culturally specific approaches to problem recognition, help seeking, and treatment participation. It builds on, and extends, the conceptualization of culture as endogenous to the socialization and development of ethnic minority and immigrant children and families and proposes the need to incorporate culturally anchored methods in assessments and interventions involving ethnic minority and immigrant children and families (Yasui and Dishion 2007). We review the significant contributions and limitations of existing conceptual models of engagement, which have informed the development of the culturally infused engagement (CIE) model (Fig. 1). Further, the systematic review of existing measures will demonstrate the relevance of our conceptual dimensions of culturally informed engagement and measurement, as well as for training, program planning, and policymaking.

Current Conceptualization and Assessment of Engagement

Conceptual frameworks of engagement in mental health treatment describe engagement as process, occurring over stages. According to McKay and Bannon (2004), treatment engagement includes: (a) the recognition of the child/family member’s mental health issues, (b) bridging the child and his/her family to appropriate services, and (c) involvement with a mental health provider (e.g., mental health center or school-based mental health care). Interian et al. (2013) also describe engagement as a process that involves a progression of linked steps: from the encouragement of seeking treatment and client continuation in care, to treatment retention and medication adherence.

This process-based conceptualization of engagement is shared by scholars across professional fields, but the increasing awareness of racial and ethnic disparities in mental health among children has directed empirical investigations to focus particularly on engagement in mental health treatment/care participation, specifically in two domains: (a) behavioral, which encompasses the client’s “performance of tasks necessary to implement treatment and achieve outcomes” and (b) attitudinal, described as the “emotional investment in and commitment to treatment” (Staudt 2007, p. 185). Within these domains, empirical literature has assessed, for example, session attendance (Nock and Ferriter 2005), adherence (Garvey et al. 2006; Nock and Ferriter 2005), therapeutic alliance (Bordin 1994), and cognitive preparation (Becker et al. 2015).

Current measures have predominantly assessed behavioral indicators, and to a lesser degree, attitudinal aspects of engagement. For example, in their systematic review, Tetley et al. (2011) identified 40 measures assessing clients’ behavioral engagement in treatment including session attendance, completion of treatment (within identified timeframe), completion of homework, client contribution such as self-disclosure or completing session activities, working alliance with the therapist, and helpful behavior in group therapies. Similarly, Becker et al. (2015) conducted a systematic review of existing engagement interventions and found of the 40 studies examined, 25 used measures of behavioral engagement, and 13 included measures of cognitive preparation, which targeted clients’ attitudes and expectations as well as knowledge regarding treatment.

Overall, these reviews highlight the importance of assessing the behavioral and attitudinal indicators of engagement, but also point to limitations of the existing literature in the near-exclusive focus on engagement behaviors or attitudes at entry into or during receipt of treatment services, and the lack of attention to preceding engagement processes (i.e., recognition of clinical need and help seeking) that is the prerequisite for treatment utilization.

The Need for a Paradigm Shift: Bridging the Gap in Existing Conceptualization and Measurement of Engagement for Ethnic Minority and Immigrant Children and Families

While existing operationalizations of engagement provide a comprehensive understanding of individual clients’ behavioral and attitudinal participation in treatment, limitations may arise in their application in addressing poor engagement among ethnic minority and immigrant children and families. Scholars note that cultural incompatibility can significantly influence ethnic minority and immigrant children and families’ seeking of, and involvement in, mental health services, because mainstream notions of mental health and appropriate treatments may counter specific cultural values, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors endorsed by these families (Comas-Díaz 2006; Yeh and Kwong 2009). For example, among some immigrant and refugee communities, discussion of mental health problems or mental illnesses is taboo due to cultural perspectives that mental illnesses signify being “crazy” or “mad,” thereby preventing families from seeking help despite need because of their fear of bringing shame on the family (Green et al. 2006; Hsiao et al. 2006; Scuglik et al. 2007). McCabe (2002) found that Mexican-American families tended to endorse negative attitudes toward modern medical and psychological approaches to treating mental health, which in turn impacted their retention in treatment. Sanders Thompson et al. (2004) noted that for African Americans, cultural beliefs that stressed family strength and emphasized resolving family concerns within the family clashed with views on seeking psychotherapy, influencing attitudes toward use of professional help. Further, the historical legacies of institutional racism have resulted in cultural mistrust at the system level, thereby increasing African Americans’ negative expectations of mental health services (Richardson 2001). These studies suggest that failure to understand engagement behaviors and attitudes from within the families’ cultural contexts can impede awareness of central mechanisms of engagement in mental health treatment.

Ethnic minority and immigrant children and families’ culture is likely also to influence the trajectory of engagement. Existing operationalizations that primarily focus on engagement behaviors and attitudes in treatment presume clients: (a) understand and accept the concept of “mental health” in the mainstream culture, (b) recognize their problem as a mental health problem, and (c) perceive mental health services as appropriate solutions for treatment. However, evidence suggests that even at the initial stage of problem recognition, ethnic minorities and immigrants vary in their perceptions and experiences of mental health problems, resulting in complex expressions of symptoms that conventional measures may not adequately capture. Studies report that ethnic minority and immigrant populations are likely to exhibit somatic rather than psychological symptoms (Mak 2005; Ryder et al. 2008; Tseng et al. 1990), as well as engage in culturally specific expressions of distress (Kirmayer 2001). Conceivably, these culturally derived frames for identifying symptoms and experiences of distress also shape ethnic minority and immigrant families’ expectations and preferences for treatment—i.e., families may be more likely to seek cultural remedies or healing approaches that align with their cultural interpretations of mental health distress.

Taken together, the aforementioned studies highlight the shortcomings of current conceptualizations of engagement in empirically addressing poor engagement among ethnic minority families. For ethnic minority and immigrant children and families, culture is infused in their individual and social understandings of health and well-being, thereby shaping what they might consider “problems” as well as what healing approaches they might think as acceptable, available, and preferable. These complex cultural influences intertwined at multiple levels of the immigrant, ethnic minority client’s life (i.e., from individual beliefs, attitudes, and practices to familial expectations, beliefs, and practices, and further, community norms, worldviews, and practices) dictate the process of engaging in the sequence of treatment from the initial stage of help seeking (e.g., recognizing the presence of a “problem” and finding appropriate sources) to the latter stages of treatment participation (e.g., attending consecutive treatment sessions) (Cauce et al. 2002; Gopalan et al. 2010; McKay and Bannon 2004).

These shortcomings signal the need for a paradigm shift from a more mechanistic view of engagement to a culturally infused process, by which culture shapes the ethnic minority and immigrant children and families’ trajectory of engagement via multiple levels and domains. The new paradigm can provide a wide lens that will help clinicians, program planners, and policymakers with information to improve the delivery of mental health services and treatment through innovations in community education and outreach, as well as in clinical work. We propose a model for a culturally infused process of engagement that draws from four theoretical models of health and mental health. Further, we apply this framework to systematically review and critique existing measures pertinent to ethnic minority and immigrant children and families. It is important to note that our review uses racial and ethnic categories as they are reported in existing studies. We recognize that these categories may be controversial in certain contexts, and we acknowledge that they may be culturally, contextually, and geographically defined. We refer to them solely in reporting the descriptions of previous articles.

Theoretical Models Informing Mechanisms of Engagement Among Ethnically Diverse Populations

The CIE model (Fig. 1) draws from four theoretical models from several disciplines (e.g., health study, medical anthropology, and mental health study) that address the salience of culture in the pathways to treatment engagement among ethnic minority and immigrant children and families. These include: (a) the sociocultural framework for the study of Health Service Disparities (SCF-HSD; Alegría et al. 2011) that highlights the multi-level factors of culture within the ecology of ethnic minority and immigrant children that influence engagement, (b) the mental help-seeking framework (Cauce et al. 2002) which illustrates the influence of culture on the progression of the engagement process (i.e., from problem recognition to treatment participation), and (c) the explanatory models of illness framework (Kleinman 1980) that describes the centrality of culture in the individual’s conceptualization of mental illness or mental distress, thereby shaping approaches to problem recognition and help seeking. Finally, we apply the theory of planned behavior model (TPB; Ajzen 1991) as a foundation for our framework to identify the influence of culture on the internal mechanisms of help-seeking intentions and actions that guide the engagement process of ethnic minority and immigrant children and families.

An Ecological Model of Influences on Engagement

The sociocultural framework for the study of Health Service Disparities (SCF-HSD; Alegría et al. 2011) is a theoretical framework of health disparities that conceptualizes the influences of multiple systems and their interactions in which cultural and societal factors shape the treatment process for ethnic minority clients. The SCF-HSD delineates influences across micro-, meso-, and macro-level contexts in two central domains: (a) the healthcare system and (b) the client’s community. Further, it identifies how these systems interact. Specifically, within the healthcare system, ethnic minority and immigrant clients’ pathways to appropriate clinical care are impacted from macro-level policies (e.g., federal, state, and economic), to meso-level influences of healthcare systems and provider organizations (e.g., diversity in workforce, organizational culture, climate), and finally, to micro-level clinician influences (e.g., gender, race, ethnicity, and provider training). Similarly, ethnic minority and immigrant clients themselves are impacted by influences from the macro-level environmental context (e.g., poverty, available health programs, residential segregation), meso-level community systems (e.g., social cohesion/support, community perceptions of health care), and micro-level individual influences (e.g., client beliefs, language, health literacy, acculturation). In this way, the SCF-HSD highlights that cultural and contextual influences saturate and further transform pathways to engagement for the ethnic minority and immigrant child.

Extending the Conceptual Understanding of “Engagement” as a Process

While the SCF-HSD illuminates the influences of culture at multiple system levels, Cauce et al. (2002) highlight the centrality of culture in the individual’s internal processes that develop through progressive stages of the engagement process. Cauce et al. (2002)’s mental help-seeking framework builds on the existing conceptual models that identify engagement as a process (e.g., Interian et al. 2013; McKay and Bannon 2004) by identifying the central cultural and contextual influences within a client’s ecology that guides the pathways to seeking help for mental health. Within each phase, culture and context have distinctive roles in shaping client’s motivation, commitment, and activation to engage in stages of seeking mental health treatment—from how problems are conceptualized, to whether help is sought, to what sources of help were targeted. For example, the authors describe that even at the first phase of problem recognition clients undergo a process of balancing an individual’s view of a “problem” with familial and larger cultural definitions of what constitutes a mental health problem. Thus, by addressing engagement processes prior to service utilization, Cauce’s model highlights the trajectory of engagement through illustrating the individual’s internal processes that are shaped by culture.

Models of Illness as a Framework for Internal Engagement Processes

Whereas the above models identify the external influence of culture on individual engagement, culturally anchored explanatory models of illness illustrate the cardinal effect of culture within the individual via beliefs and experiences of mental health. Defined as “the notions about an episode of sickness and its treatment that are employed by all those engaged in the clinical process” (Kleinman 1980, p. 12), explanatory models are central frameworks that provide an understanding of both perceived causes of illnesses and appropriate healing methods. Since cultures vary in their explanatory models of illness, the clinical reality of clients is culturally constructed, suggesting that cultural context plays a fundamental role in shaping internal mechanisms of how individuals explain their distress, make meaning of experiences, and cope with or seek treatment for their illness.

Evidence suggests that there are cultural variations in the expression and conceptualization of mental health symptoms and problems. Ethnic minorities and immigrants are more likely to interpret and express distress in ways that are consonant with their culture (e.g., somatic symptoms, idioms of distress) (Fung and Wong 2007; Yeh et al. 2004). Moreover, these expressions of mental health distress are linked to culturally specific explanations that give meaning to the illness experience and guide approaches to healing. In this way, cultural explanatory models of illness shape the process of engagement through individuals’ (a) beliefs about their mental health distress, (b) beliefs about healing and treatment, and (c) cultural norms regarding mental health distress and appropriate treatments.

Understanding the explanatory models of mental health for ethnic minority and immigrant children and families may be critical in the context of mental health care in the USA. The explanatory model’s culturally driven approach to conceptualizing mental distress or illness distinctly contrasts with the biomedical framework that postulates a disease-oriented approach to the identification (i.e., diagnosis) and treatment of mental disorders. The increasing biomedical emphasis on precise identification of mental health dysfunction and the specialization of treatments designed to target specific dysfunctions directly have resulted in important contributions to clinical practice. But for ethnic minority and immigrant children, cultural considerations are paramount to enhance engagement, tailoring treatment and service delivery approaches to be congruent with their lived illness experiences and those of their families.

Theory of Planned Behavior—Internal Processes of Engagement

The theory of planned behavior model (TPB) (Ajzen 1991) has been applied widely to predict engagement in health behaviors (Armitage and Conner 2001) and services (Dumas et al. 2007), suggesting its relevance as a model for examining individuals’ engagement in mental health services. According to the TPB, behaviors are largely determined by the individual’s intention to perform a behavior, where intentions are a function of three domains: (a) the individual’s attitude toward the behavior, (b) the subjective norms associated with the performance of the behavior, and (c) the individual’s perception of efficacy in performing the behavior (Ajzen 1991). Thus, the TPB’s focus on the interplay of cognitive and behavioral processes in individuals’ decisions regarding their behaviors can be instrumental in identifying culturally informed individual-level attitudes, beliefs, and practices about engagement shaped by network-driven explanatory models of illness.

Proposed Model of Engagement—Cultural/Contextual Process of Engagement

Integrating and synthesizing the above models, we propose the culturally infused engagement (CIE) model (Fig. 1) that can facilitate the identification of gaps in the understanding of the engagement processes for ethnic minority and immigrant children and families. As a more comprehensive model of the help-seeking process, it is the foundation of our literature review, as its application can also provide insight into unexplored areas of the help-seeking process for ethnic minorities and immigrants that contribute to disparities in treatment and service delivery.

Figure 1 shows how the ecological context of the ethnic minority and/or immigrant child is saturated with cultural and contextual influences from multiple systemic levels. It underscores that children are primarily dependent on their parents or adult family members to seek, obtain, and participate in mental health services. Thus, family members’ explanatory models of mental health and illness are likely to be critical determinants in shaping the trajectory of treatment engagement for the ethnic minority and immigrant child. At the meso-level, the values, beliefs, and practices of the ethnic community, church, school, and neighborhood may serve as the foundation for the specific explanatory models adopted by ethnic minority and immigrant children and their families. Lastly, macro-level influences such as discrimination or the US mainstream culture (e.g., media exposure on mental health) directly or indirectly influence ethnic minority and immigrant children’s understanding of mental distress and illness, and hence, treatment engagement. These complex multi-level influences are manifested at the individual level, as the explanatory model of illness.

The explanatory model serves as a map of interwoven beliefs, intentions, and behavioral and emotional responses that uncovers how an individual understands his or her lived experience of illness. This involves examining (a) the individual’s conceptualization of the distress, which involves understanding the illness cause, course, identity, and illness experience, and (b) his or her response to the mental illness/distress (i.e., healing approaches). The conceptualization of mental distress, which points to the stage of problem recognition, could be manifested either through causal beliefs (e.g., psychological, biological, supernatural) derived from the expressions or the identity of the illness (e.g., idioms of distress), or through the way in which the client conceives the personal meaning of the illness experience. That conception can be shaped (a) by behavioral beliefs about mental distress (i.e., its expected outcomes) and (b) by agency beliefs (i.e., perceived control over the illness or distress) that encompass the effect of external barriers (e.g., lack of insurance, transportation issues, lack of childcare) on the lived illness experience. At the same time, perceived norms (the perceived meanings of the illness or distress for others) can also play a role in determining the meaning of the individual’s lived experience of illness within broader sociocultural contexts. Together, beliefs and perceived norms form the conceptualization that influences the seeking of relevant methods of healing, and, subsequently, an individual’s response to the illness experience in both help seeking and treatment participation.

Using the framework of the culturally infused process of engagement, we empirically examined the multi-dimensional and progressive process of engagement by conducting a systematic review of existing assessments that inform culturally specific approaches to problem recognition, help seeking, and treatment participation among ethnic minority and immigrant children and families. While the primary focus of our framework is ethnic minority and immigrant children and families in the US context, we also draw from cross-cultural literature to inform our understanding based on the following reasons: (a) In certain domains, evidence with culturally diverse populations is limited and (b) the studies are conducted in cultures of origin of immigrant populations in the USA.

Methods

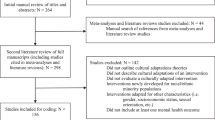

We conducted a computerized literature search of the PsycINFO, ERIC, IngentaConnect, Google Scholar, and JSTOR databases using a keyword approach to identify relevant empirical measures in domains of problem recognition, help seeking, and engagement in services between 1960 and 2015. The following keywords were used individually and in combination to guide the literature search by each domain: for problem recognition, “idioms of distress,” “culturally bound syndromes,” “child psychological problems,” “mental health symptoms,” “explanatory models of illness,” “mental health beliefs,” and “causal beliefs about mental illness/mental health problems”; for help seeking, “help seeking,” “mental health,” “explanatory models of illness,” “stigma,” “mental health beliefs,” “healing approaches,” and “treatment”; and for engagement in services, “mental health,” “explanatory models of illness,” “treatment,” “psychotherapy,” “treatment engagement,” “treatment participation,” and “mental health service use.” Across all of these, the keywords “culture,” “ethnic minority,” “immigrant,” “measures,” “scale,” and “inventory” were combined to identify existing measures within these domains. In addition to the electronic searches, we conducted manual searches for existing measures that included examining the reference lists for each paper. Measures were included in the review if they met the following criteria: (a) The instrument was designed to measure the domains according to the CIE, (b) the paper was published in a peer-reviewed journal or was a published or unpublished assessment manual, (c) the paper reported psychometric properties of the measure, (d) the paper reported measures that provided the original items or authors shared the unpublished measure, and (e) children, youth, and families, and (f) ethnic minorities, immigrants, or the measures were used with cross-cultural samples. Four semi-structured interview assessments that captured open-ended responses were also included based on the culturally anchored probes utilized to elicit client-defined beliefs about mental distress and healing approaches. Measures were excluded if they assessed beliefs and behaviors regarding one specific treatment modality or approach or if they assessed provider-centered beliefs. In addition, because an item-level analysis of existing measures was performed, instruments for which we were unable to locate the original measure were excluded.

Two systematic reviews of measures on help seeking and treatment (Gulliver et al. 2010) and treatment participation (Tetley et al. 2011) are in the extant literature. Those reviews examine engagement as a universal construct, rather than as a culturally defined process. While some overlap in the identification of measures between our review and theirs is inevitable, we focus on a different aim: whether the measures assess culturally specific mechanisms of engagement.

Based on the above criteria, 119 measures published between 1963 and 2015 were included in this review.

Coding of the Measures

All existing measures were coded independently by a team of 6 coders that categorized the measures at the item level according to the domains defined by the culturally infused engagement (CIE) model. Coders were trained (a) on the theoretical frameworks of the SCF-HSD (Alegría et al. 2011), the help-seeking model (Cauce et al. 2002), explanatory models of illness (Kleinman 1987), and the theory of planned behavior model (Ajzen 1991), (b) on differentiating items according to the domains of the TPB (Ajzen 1991), and (c) on categorizing items based on the domains identified that corresponded to the CIE. All coders were trained by the first author.

Domains were operationalized using the definitions from the aforementioned theoretical frameworks. Coders categorized items from measures according to whether they assessed the following dimensions of the CIE: (a) causal beliefs, (b) symptom presentation or expression, (c) beliefs about the mental distress (conceptualization and illness experience of the distress), (d) beliefs about seeking help, and (e) behaviors of help seeking. Within the category of beliefs about the mental distress, items were further categorized into: (i) beliefs about the illness identity, (ii) beliefs about characteristics/internal traits of individuals with the illness, (iii) the individual’s beliefs about the illness experience (i.e., attitudes and expected responses, and agency/control beliefs), and (iv) perceived norms regarding the internal and external illness experience. Beliefs about seeking help included: (v) expectations and efficacy beliefs about seeking help (professional and alternate), (vi) perceived norms associated with seeking help, (vii) agency/control beliefs and the willingness/intent to seek help (professional vs. other), and (viii) relational beliefs regarding seeking help.

Each item was examined for its relevance in assessing the CIE domains. For domains that reflected the TPB model (e.g., behavioral beliefs, agency/control beliefs, social norms, intentions), we followed the descriptions of TPB items by Fishbein and Ajzen (2010). For other domains that were uniquely identified in the CIE (e.g., causal beliefs, expressions, illness identity, beliefs about internal traits/characteristics), definitions for each domain were derived using the existing literature. For example, illness identity beliefs were defined as beliefs about the illness or distress itself and not the individual with the illness (e.g., “depression is not a real medical illness,” “I do not believe that psychological disorder is ever completely cured”), whereas beliefs about the characteristics/internal traits of the individual with the illness included items that described perceived qualities of the individual that shaped the self-illness experience (e.g., “A problem like X’s is a sign of personal weakness,” “mentally ill people tend to be violent”). Causal beliefs were defined as applying to the mental health problem itself and a range of attributed causes (e.g., “the illness is caused by a brain disease”). The expressions of illness encompassed symptoms (physical, psychological, emotional, behavioral, relational), as well as cultural idioms of distress (e.g., “Did your ears suddenly become blocked and as a result you experienced buzzing sounds in your ears?”, “I experience brain burning, crawling heat or cold or other unpleasant sensations in my head, while studying”).

Coders received training until they reached reliability in categorizing items. Discrepancy among coders on item categorization was reviewed by all coders and discussed in weekly consensus meetings. Generally, disagreements among coders were resolved by refamiliarizing them with the definitions of each domain and discussing the correspondence of specific items to their respective domains. Inter-rater reliability was assessed using Cohen’s (1960) kappa because it adjusted for raters’ agreement that can occur due to chance. The kappa coefficient obtained for this study was 0.92 which suggests an excellent level of agreement on the codes across raters (Landis and Koch 1977).

Findings

Table 1 contains 119 existing measures categorized based on the proposed domains in our conceptual model: (a) expressions of distress (idioms of distress and symptom expression across culture), (b) causal beliefs (explanations of mental distress and illness), (c) beliefs about mental distress and illness (illness identity and meaning of the illness), (d) beliefs and experiences of seeking help (beliefs about healing approaches and help-seeking behaviors). Twenty-six percent (31 measures) were identified as reflective of symptoms and expressions of mental distress, 30% (36 measures) identified causal beliefs, 50% (60 measures) assessed self and others’/public beliefs about mental health problems, and 51% (61 measures) assessed beliefs about mental health services. Further, 78% of the measures (93 of the 119) have been utilized with ethnic minority, immigrant, or cross-cultural samples; 55% of the measures (66) have been assessed with children, youth, or families; and 35% (42) have been used with ethnic minority, immigrant, or cross-cultural samples and with children, youth, or families (Table 1). These findings highlight the relative under-exploration of symptoms and expressions of distress and causal beliefs that precede problem recognition and help seeking. This phase in the help-seeking process may have the most importance for ethnic minority and immigrant children and families because it defines how the client understands the problem, setting the course for culturally responsive service use. An item-level analysis of these measures that we describe in our review reveals multiple and important contributions to measurement that is culturally sensitive. The analysis also shows significant gaps in measurement to understand the help-seeking processes for ethnic minority and immigrant populations. The review of the four domains and the item-level analysis supports the wisdom of a culturally infused perspective on the help-seeking process prior to the clinical encounter. Effective community outreach and treatment interventions are predicated on this culturally infused understanding. Below, we discuss our review of existing measures according to each of these domains, respectively.

Expressions of Distress: Idioms of Distress and Symptom Expression Across Cultures

The biomedical/biopsychosocial framework is the underlying basis for the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) which classifies mental distress as psychological, behavioral, and biophysical dysfunctions or abnormalities (American Psychiatric Association 2013). The central notion of dysfunction is foundational to the DSM’s approach to the identification of psychopathology by which symptoms are perceived as objective, measurable indicators of abnormalities (i.e., a disease) in an individual’s biological and psychological makeup and function that determine diagnoses (Thakker and Ward 1998). Further, this approach to problem identification has guided the development of mental health treatments that centralize on the reduction of symptoms, leading to the advancement of evidence-based treatments (Yasui and Dishion 2007).

Despite the significant utility of the biopsychosocial/biomedical model’s scientific, objective approach to addressing mental health problems by the identification of areas of dysfunction, studies have found that cultures differ in their notions of distress (Kirmayer 2001; Ryder et al. 2008). Rather than perceiving symptoms as indicators of dysfunction, some cultures apply a holistic interpretation that encapsulates not only the specific expressions of dysfunction but also the multifaceted reactions of the individual and their relationships and culture to the distress. This constellation of changes in state and function along with the subjective and experiential aspects of the distress is described in medical anthropology as the illness experience (Kleinman 1980). Culture shapes the illness experience through the various beliefs, values, practices, and norms, giving rise to significant variations in how illness is characterized, how individuals make meaning of the illness such as its cause and course, and appropriate ways of healing or treating the illness (Harwood 1981). In this way, culture determines the conceptualization and recognition of symptoms, as well as the idioms and expressions used to communicate the experience of the distress or illness.

Table 1 shows our review of existing measures and indicates that 99 of the 119 measures (83%) did not include items that targeted problem recognition, but rather, defined the “illness” either by the use of mental health terminology or vignettes that portrayed specific symptoms or DSM disorders. Of these, the majority used mental health terminology that included general mental health terms (e.g., mental illness, mental disorder, mental health problem, psychological problem, emotional/behavioral problem), or descriptions of receiving mental health care (e.g., psychiatric patient, mental patient, seeing therapist, psychosocial treatment) as definitions of mental distress in their questionnaires/interviews. This wide application of a generalized mental health terminology and the defining of illness expressions by DSM diagnostic criteria among existing measures reflect the implicit assumptions of the current mental health field that conceptualizations of mental health disorders/problems hold equivalent meanings and are commonly shared by the public.

Of the total 119 measures, 31 (26%) assess the culturally infused engagement (CIE) model’s dimension of illness expressions (Fig. 1). Overall, measures assessing symptoms or expressions of mental distress captured expressions across a variety of domains including somatic symptoms, psychological (emotional, cognitive, behavioral) symptoms, culturally specific somatic symptoms, culturally specific emotional and psychological distresses, and spiritual/supernaturally related symptom expressions. Among the 31 measures (Table 2), 19% (6) of measures included items that inquired about general mental health symptoms (i.e., without specification of disorder type), 39% (12) assessed symptoms specified to DSM disorders and symptoms (e.g., depression, schizophrenia, suicide, etc.) of which 26% (8) were culturally adapted. Additionally, based on our scope to identify culturally specific symptoms, 61% of the measures (19) were identified that assessed culturally specific symptom expressions of distress or culturally bound syndromes. The diverse constellations of culturally specific symptoms across somatic, behavioral, psychological, and spiritual domains of these measures highlight their distinctiveness from the conventional symptom structures of the DSM.

Review of the measures revealed that 58% (18) of the 31 measures endorsed somatic symptoms, suggesting the salience of physical or bodily symptoms as indicators of distress. This propensity for physical and physiological symptoms as major indicators for recognizing mental distress has been documented across ethnic groups—studies among Asian, Latino, and African Americans indicate that somatic expression of psychological symptoms is much more prevalent compared to European-Americans (Choi 2002; Mak 2005; Myers et al. 2002; Ryder et al. 2008; Tseng et al. 1990). Moreover, 45% of the measures (14) included somatic symptoms that were culturally specific [e.g., sputum moving upward and causing sensations of a heart arrest or inability to breathe (e.g., the Cambodian Somatic Symptom and Syndrome Inventory), noises in ears (i.e., symptoms of Ode-Ori)], suggesting the important role of culture in the shaping the recognition/identification of distress and meanings attached to these bodily sensations. In particular, among cultures that view health holistically, interpretations of distress are viewed as stemming from the body, spirit, mind, and human relationships, resulting in expressions that link emotional and behavioral states to physical sensations (e.g., anger in the liver). Furthermore, historical influences may also shape the identification of culturally specific somatic symptoms; for example, Hinton et al. (2013) describe that somatic symptoms such as neck soreness among Cambodians are associated with the traumatic experiences of the genocide by which individuals engaged in slave labor were forced to carry heavy loads of dirt on a pole that was balanced at the neck. Thus, although there are some universal somatic representations of distress, the identification of these symptoms appears to be primarily culturally derived.

In addition to somatic symptoms, 84% (26) of measures also included psychosocial (emotional, behavioral, cognitive, and interpersonal/relational) symptoms. Thus, while ethnic minorities and immigrants may primarily endorse somatic symptoms, examining co-occurring psychological symptoms is also important. Symptoms described indicated a range of culturally specific symptoms to symptoms identified in conventional DSM disorders (e.g., little interest in doing things, trouble concentrating). Culturally specific psychological symptoms ranged from cultural phenomena such as haan, which is described as “the collapsed pain of the heart due to psychosomatic, interpersonal, social, political, economic, and cultural oppression and repression” (Park 1993, p. 16), to context-specific symptoms (e.g., “When I read I feel that the words don’t make sense”, an item of the Brain Fag Scale; Prince 1962).

Lastly, 13% of the measures (4) assessed spiritual/supernatural indicators of distress. For example, the Cambodian Somatic Symptoms and Syndrome Inventory (CSSI; Hinton et al. 2013) includes items that symbolize spiritual associations to the body (e.g., “ghost pushing you down” for sleep paralysis, lightness in the body as if your soul was not in your body). This link between spiritual or supernatural factors and symptoms/idioms of distress demonstrates the intricate connection between culturally anchored causal beliefs and the sociocultural meanings of distress and their expressions (Kleinman 1978).

In sum, our review of measures on culturally unique symptom expressions and idioms covers a wide range of indicators of distress—from somatic symptoms, to emotional or psychological problems, to spiritual or supernatural expressions—that are represented by several different ethnic minority and immigrant groups, showing the significant diversity among those groups in their conceptualization and recognition of mental illness. According to the CIE (Fig. 1), this diversity in illness expressions might fundamentally shape ethnic minority and immigrant children and families’ beliefs about, attitudes toward, and reactions to the mainstream mental health diagnoses and services which are largely based on the DSM framework, thereby affecting their engagement in treatment. However, our review also highlights a critical gap in the literature, reflected in the paucity of existing measures that capture these cultural variations. Limitations of this kind can have significant implications in clinical practice—including the misdiagnosis or underdiagnosis of mental health symptoms and disorders among ethnic minority and immigrant children and families. In fact, evidence suggests that the lack of attention to culturally specific indicators of distress has resulted in repeated underdiagnosis and misdiagnosis of psychological disorders among some minority youth and adults (Choi 2002). Thus, while conventional measures of psychological distress and dysfunction continue to be important, our review points to the need for measures that simultaneously address culturally determined presentations of psychological distress. The consideration of these cultural nuances at the symptom expression stage would position the role of culture at the foreground for understanding how ethnic minority children and families formulate their conceptions of “problems” as well as identifying their thresholds of need for help seeking, which might be an effective means to address ethnic and racial disparities in mental health service engagement.

Causal Beliefs: Explanations of Mental Distress and Illness

The culturally infused engagement (CIE) model identifies causal explanations of mental illness or distress as the crux of the conceptualization of mental health distress and response to healing (Fig. 1). Differences in causal beliefs between mental healthcare professionals and ethnic minority and immigrant children and families therefore may have significant implications in the clinical context. As we have described, mental health care in the USA has predominately operated from a biomedical framework that prioritizes the identification of the cause of the “disease” (i.e., mental disorder) in the biological, psychological, and behavioral domains. While the integration of the biopsychosocial model has broadened the scope in locating causal factors of mental distress and illness across domains, the primary focus on identifying specific causal mechanisms to target intervention may often be at odds with ethnic minority and immigrant clients’ understanding of their illness experience. For ethnic minority and immigrant children and families, causal beliefs stem from their cultures’ conceptualizations of mental health that are often holistic, without definitive boundaries between cultural, spiritual, physical, and psychosocial domains (Betancourt 2004; Bolton et al. 2004; Carrillo et al. 1999). Our review of individuals’ causal beliefs about mental health distress/mental illness across the existing measures highlighted the dichotomy between the biomedical framework (i.e., biology/genetics, psychological, or social/environmental causes) and cultural explanatory models of illness (i.e., supernatural/spiritual and culturally specific causes). We organize relevant measures in Table 3 and describe each of the causal domains identified in our review below.

Biological/Genetic/Physical Causes

Of the 36 measures assessing causal beliefs, 24 (67%) identified biological, genetic, or physical causes, highlighting the dominant view that mental health problems/illnesses are biological, medical illnesses in nature (Table 3). Biomedical causes assessed included genetic/heredity, to brain mechanisms (e.g., disorder of brain, neurochemical imbalance), prenatal influences, physical illness or injuries, and physical reactions (e.g., allergies, sensitivity to foods/drugs/alcohol). The attribution of biological/genetic/physical causes of mental health problems was evident across measures assessing: (a) clinically diagnostic as well as cultural conceptualizations of mental health distress/mental illness, and (b) diverse ethnic and racial populations, which suggests a prevalent view of biomedical explanations of mental health problems. Such may reflect the increasing spread of biomedical knowledge of causes of mental health problems/mental illness not only in mental health disciplines but further, to the general public (Insel 2009).

Seventeen percent (6) of the 36 measures also captured physical causes embedded in culturally based explanatory models of illness. These measures included culturally based physiological causes that were generally identified as an imbalance or disruption of harmony in the body (e.g., energy imbalance, humoral imbalance, yin/yang, cold/hot, energy, or vitality flow). Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and Indian Ayurveda medicine are two examples of still commonly believed and practiced medical systems holding such holistic views of life and health. In TCM’s epistemology, for example, mind and body are considered inseparable, and balance of energies needs to be maintained to achieve a “healthy” state of life (Kuriyama 2002). Studies suggest that among Asian Americans, TCM is frequently used either as an alternative to or in combination with Western medical treatment approaches (Feng et al. 2006), which may reflect their strong reference to traditional causal beliefs when contemplating biological or organic causes of mental health problems (Matthews 2012).

Psychological Causes

Psychological causes of mental health problems included dimensions of cognitive, behavioral, emotional, personality/character, and trauma history/past experiences. Reflective of the centrality of the biomedical/BPS framework, 86% (31 of 36) of the measures assessed one or more dimensions of psychological causes (Table 3).

Cognitive, Emotional, Behavioral, and Personality Causes

Eighty-one percent (29) of the 36 measures assessed cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and personality causes—consisting of the following types: (a) lay perceptions of symptoms/descriptors associated with specific clinical disorders (e.g., for schizophrenia: thinking too much, for ADHD: not trying hard enough), (b) therapeutic descriptions of psychological processes related to mental distress (e.g., not having a realistic view of the good and the bad things that have happened), (c) engagement in dysfunctional behaviors or habits (e.g., substance or alcohol use or misuse), and (d) traits or qualities related to a person’s nature (e.g., bad character). Further, the psychological causes reflect two prevailing perspectives related to mental health problems/mental illness—the ascription of responsibility to the individual for his or her mental illness (e.g., not trying hard enough to control behavior) and the perceived changeability of the mental illness. Across types, the ascription of responsibility for one’s mental health problem/illness is evident, although variation exists in the degree to which the responsibility is inferred, and further, intersects with perceptions of changeability. For example, while internal causal mechanisms are implied in both the cause “having learned the wrong reactions to certain situations” and “bad character,” the latter suggests a broader internal cause that has more permanency or rootedness, and thus is more difficult to change. Thus, perceptions of the controllability, intentionality, and stability of an individual’s negative behaviors are likely to play a central role in whether others respond negatively or positively (Weiner et al. 1988). Studies examining parental attributions of child behaviors suggest that parental beliefs about causes of mental health problems influence attributions of child responsibility for negative behaviors (Gerdes and Hoza 2006; Johnston and Freeman 1997; Johnston et al. 2005; Pottick and Davis 2001). Further, culture may influence the ways in which parental causes are attributed to mental health problems among children (Mah and Johnston 2007).

Psychological Trauma Causes

Among 36% (13 of 36) of the measures included in our review, psychological trauma was identified as the cause of mental health problems/mental illness. Measures assessed causes of interpersonal trauma (e.g., physical abuse, sexual abuse, witnessing violence), as well as traumatic events or situations experienced by the family or the community (e.g., poverty, hardships, natural disaster, war, genocide).

The inclusion of psychological trauma in measures is indicative of the BPS model of mental health, which conceptualizes the interaction of traumatic events with the psychological and physical functioning of the individual. Within the field of mental health, recognition for the significance of trauma in shaping mental health problems/mental illness became widespread with the identification of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a formal diagnosis (Schnurr and Green 2004) and resulted in a large body of literature supporting the link between trauma and poor psychological functioning (Hutchinson and Dorsett 2012; Mollica et al. 1993; Steel et al. 2002). This increased awareness of the causal effects of trauma has resulted in numerous benefits such as the development of evidence-based programs addressing trauma (Westoby and Ingamells 2010).

Despite these advances, the notion of trauma is not always shared across various cultures. Some scholars have noted that the labeling of certain past experiences or events as “trauma” inadvertently promotes the biomedical conceptualization of a deficit or pathology framework of mental health (Marlowe 2009; Raymond 2005), thereby overlooking cultural explanations and ways of healing from the event(s). For example, in his study on Sudanese refugees, Marlowe (2009) highlights participants’ discomfort with others’ assumptions that trauma is a central characteristic of their identity and group identity, and argues for the understanding of the event within the lens of the ordinary lives of the individuals that are anchored within their cultural context. Such underscores the importance of assessments that capture the individual’s culturally determined experiences, expressions, and meanings of the distress that conventional measures are limited in assessing (Eisenbruch 1991).

Social/Interrelational Causes

Fifty percent (18) of the 36 measures captured social/interrelational causes highlighting a dominant belief in interpersonal contextual causes of the development of mental health problems/mental illness (Table 3).

Social/relational causes included familial (15 measures) (e.g., parental, marital, extended family relations), and non-familial (general) relational causes (10 measures) (e.g., peer relations and relations with others). Among familial causes, parental causes of mental health problems/mental illness were the majority and included negative parenting (e.g., negative discipline, poor parental involvement, and poor parent–child relationships), familial relationship problems (e.g., marital discord, conflict with relatives), and parental distress (e.g., parental mental health). Negative parenting was the most frequently assessed relational cause across measures, which likely reflects a commonly held belief that attributes responsibility to parents for a child’s mental health outcome. Particularly in the case of child mental health, evidence indicates that across ethnic groups perceptions of parental responsibility are frequent (Malacrida 2001; Singh 2004), both among parents themselves and also by others. Studies suggest that parents often blame themselves and attribute the causes of their child’s mental health problems to themselves, despite acknowledging other causes such as biological, genetic, or environmental causes (Moses 2010). The attribution of parental responsibility for child mental health problems appears to be shared widely—not only by the general public (Corrigan and Miller 2004; Struening et al. 2001; Weiner et al. 1988) but by teachers (Edwardraj et al. 2010) and mental health professionals (Johnson et al. 2000, 2003). Moreover, recent studies have reported ethnic differences in attributions of parental responsibility to child mental health problems (Young and Rabiner 2015), highlighting the importance of examining variations in these beliefs across cultures.

Three measures assessed familial relationship causes that ranged from illness or death of a family member to family conflict, reflecting the belief that the family context significantly affects the healthy functioning of individual family members. Studies indicate that family members (i.e., parents, spouses, siblings) often report concerns of being blamed or held responsible for causing family members’ mental health problems as well as the management of the illness (Greenberg et al. 1997; Phelan et al. 1998). Moses’ (2010) study on parental beliefs regarding their youth’s mental illness describes the parents’ sense of responsibility for their child’s exposure to a negative family contexts such as instability or violence. For ethnic minority and immigrant children and families from collectivistic cultures, the attribution to familial causes may be even more acute as individuals’ identities are viewed as embedded within central relationships (i.e., familial) rather than independent, autonomous entities (Markus and Kitayama 1991).

Non-familial social/relational causes included general relationship with others, peer relations, and relationships at work. Twenty-eight percent (10 of 36) of the measures assessed non-familial causes which may reflect the lower significance of such relationships compared to parental and familial relationships in their impact on the mental health of individuals.

Contextual (Environmental/Societal/Cultural) Causes

Several measures cited environmental causes of mental health problems/mental illness. Forty-seven percent (17) of the 36 measures assessed specific contextual causes such as exposure to environmental substances (e.g., contamination, atomic rays, lead), cultural factors (e.g., assimilation to American culture), societal influences (e.g., media), and socioeconomic factors (e.g., financial difficulties, family poverty) as well as a broader category of stress which was most frequently cited (Table 3).

Six measures assessed socioeconomic causes that consisted of: (a) income-related specific causes (e.g., financial difficulties, family financial crises), (b) work-related causes (e.g., unemployment), and (c) social position-related causes (e.g., single parent, lives in inner city). The causal belief in the negative impact of socioeconomic stressors on mental health is reflective of evidence establishing the causal link (Conger et al. 2002; McLoyd 1998) as well as a widespread public perception that associates mental health problems with the poor (Lind 2004; Orloff 2002) and ethnic minorities (Gilens 1999; Neubeck and Cazenave 2001).

Only a handful of measures assessed other societal causes, including such things as the influence of media, and the hectic pace of modern life. Moreover, it is alarming that only one measure (Yeh and Hough 1997) specifically assessed cultural factors as causes of mental distress. The paucity in the range of contextual causes for mental health problems signifies a need for assessments also to consider factors that may be particularly salient for ethnic minority and immigrant children and families. For example, significant literature has demonstrated the negative effects of racism or discrimination on mental health outcomes among African American, Latino, Asian American, and Native American youth and adults (Rosenbloom and Way 2004; Whitbeck et al. 2002; Wong et al. 2003). Studies indicate that the negative effects of discrimination on youth developmental outcomes include increased delinquency and problem behaviors such as shoplifting, skipping class, lying to parents, cheating, stealing cars, and bringing drugs or alcohol to school (Okamoto et al. 2009; Prelow et al. 2004; Wong et al. 2003) as well as internalizing problems such as depressive symptoms (Seaton et al. 2008) and anxiety (Gaylord-Harden and Cunningham 2009; Hwang and Goto 2008). Similarly, studies on Latino and Asian American immigrant youth suggest that acculturative stress is a significant predictor of poor mental health—including internalizing problems (e.g., withdrawal, anxiety, somatic and depressive symptoms), and externalizing behavior problems (i.e., delinquency, aggressive behaviors) (Dinh et al. 2008; Gil et al. 2000; Hovey and Magaña 2002; Vega and Gil 1998). Considering the supporting evidence, including salient contextual factors that are predictive of poor outcomes among ethnic minority and immigrant children and families will be a critical direction for future measures.

Spiritual/Supernatural Causes

The explanatory models of health among ethnic minority and immigrant children and families often include holistic conceptualizations, of which supernatural/spiritual factors are an integral component (Betancourt 2004; Carrillo et al. 1999). Of the 36 measures examined, 44% (16) identified supernatural/spiritual causal beliefs about mental illness/mental health problems, suggesting the importance of this dimension (Table 3). The supernatural causes assessed clustered under spiritual or religious (e.g., work of the devil, will of God), magical (e.g., curses, witchcraft), karmic (e.g., previous deeds of ancestors or in former life), and cosmic (e.g., born on specific days) dimensions.

The centrality of the supernatural in health and mental health is highlighted in the proposed frameworks of medical anthropologists that encompass supernatural causes of illness (e.g., Eisenbruch 1990; Murdock et al. 1980; Young 1976). Evidence supports the saliency of supernatural causal beliefs among ethnic minority and immigrant populations (Cohen et al. 2009; Tarakeshwar et al. 2003). Studies suggest that individuals and cultures where spirituality and religion play a significant role are more likely to attribute symptoms or expressions of distress to supernatural, religious, or spiritual causes, and further, seek help from religious, spiritual, and alternate sources (Abe-Kim et al. 2004; Hartog and Gow 2005; Mathews 2008; Wilcox et al. 2007). The causal attribution to supernatural factors has also been found to explain child mental illness cross-culturally. For example, autism in children has been attributed to wicked ghosts (Hwang and Charnley 2010), child psychiatric disorders have been linked to the evil eye or a curse (Guzder et al. 2013), and ADHD is seen as coming by God’s hand or the influence of stars and planets (Wilcox et al. 2007). These findings highlight the importance of addressing supernatural beliefs in mental healthcare practice, as misconstruing culturally unique conceptualizations of mental distress and illness will likely overlook ethnic minority and immigrant children and families’ existing help-seeking beliefs, resources, and behaviors, as well as deter their engagement in professional mental health services. While the ways in which supernatural causal beliefs can be addressed in clinical practice are multifaceted and dependent on the unique explanatory model of the client, gaining an understanding and knowledge of them and how they shape clients’ own understanding and meaning of their illness is essential in identifying appropriate avenues for intervention. For example, a clinician who learns that a client attributes an imbalance in the energy within her body as the cause of her mental distress may approach the discussion of psychiatric medication with an individualized caution and sensitivity, examining alternate treatment options that match the client’s culturally anchored explanatory model of illness.

Overall, our review of existing measures illustrates the diverse range of causal beliefs associated with mental distress and illness. As expected, the majority of measures assessed causal factors that represented a biomedical or biopsychosocial perspective of mental illness or distress, which suggests the predominance of these frameworks in contemporary mental health care. There are also several measures capturing causal beliefs that illustrated culturally anchored explanatory models of illness such as supernatural forces, the cultural context, and natural factors (e.g., yin yang). These measures are examples of the increased number of studies recognizing the relevance of cultural alternatives in causal beliefs for ethnic minority and immigrant populations, which is also reflected in the recent changes to the DSM through the inclusion of the cultural formulation interview (CFI). The integration of the CFI, which incorporates the explanatory model of illness framework, highlights a promising potential in broadening the current paradigms of mental health assessment and diagnosis, by taking cultural diversity and alternative epistemologies of health into serious consideration when evaluating immigrants’ and ethnic minorities’ causal beliefs about their illness experiences. However, these changes have still positioned culturally specific factors as supplements/alternatives to the mainstream biopsychosocial model.

It is worth noticing, based on the culturally infused process of engagement model, that culture should be understood as cross-system influences which shape individuals’ explanatory model of illness through the dynamics between different systemic mechanisms—from macro-level acculturation experiences, meso-level community norms and beliefs, to familial-level expectations and practices (see Fig. 1). Therefore, the mainstream biomedical/biopsychosocial perspective in mental health could also be integrated into this overarching framework as one aspect affecting ethnic minority and immigrant families’ causal beliefs about mental illness in their current living contexts. For example, immigrant parents might shift their causal beliefs about mental illness after being exposed to this mainstream perspective through media or their children’s education for a period of time. In this way, we might approach these different sources of causal beliefs not as oppositional, but as interactive in ethnic minority and immigrant families’ lived experiences. This integrative framework calls for the development of measures that allow more comprehensive and dynamic assessments of ethnic minority and immigrant populations’ causal beliefs about mental illness.

Beliefs About Mental Distress and Illness: Illness Identity and Meaning of the Illness Experience

The culturally infused engagement (CIE) model proposes that the conceptualization of mental illness and mental health problems significantly shapes the ways in which an individual may ascribe meaning to the experiences of distress or illness and hence their motivation to engage in treatment. Beliefs play a central role in how individuals interpret the illness experience, which is expressed in the attitudes, affect, and behaviors toward the illness or persons with the illness (Petrie et al. 2007). Beliefs and attitudes toward mental distress and mental illness have largely been examined within two overlapping literatures—the literature on explanatory models of illness and on mental health stigma.

As illustrated in the CIE, explanatory models of illness are central to conceptualizations of mental health. Kleinman (1978) purports that explanatory models encompass several dimensions of an individual’s beliefs about mental illness/distress—from beliefs about the illness, about personal and social meanings associated with the illness, and about healing approaches and expected outcomes. Since culture is the essential context that shapes explanatory models of illness, it provides the foundation for variations in the interpretations and definitions of distress/illness that are represented in individuals’ beliefs, norms, and practices regarding the illness experience.

Cross-cultural evidence suggests that cultural health beliefs often determine individuals’ endorsement of positive or negative beliefs about mental illness. For example, among German adults, Schomerus et al. (2014) found links between biogenetic beliefs and lower social acceptance for schizophrenia and depression but higher acceptance for alcohol dependence, whereas psychosocial beliefs for schizophrenia resulted in higher acceptance. Wong et al. (2004) found that Chinese caregivers of individuals with mental illness felt less of a family burden that those from other cultures, positing that traditional Chinese medical beliefs de-emphasized family members themselves as a cause of the mental illness. Among Latino parents, Lawton et al. (2014) found that parents who reported higher levels of familism and strongly endorsed traditional gender roles were more likely to attribute sociological or spiritual causes for their child’s ADHD. Fan (1999) noted that compared to Caucasians, Asians and others (participants of other ethnicities) were more likely to endorse authoritarian attitudes that perceived individuals with mental illness as different and inferior to normal persons. Overall, research demonstrates the important role of culture as a key determinant in the variations across individuals’ endorsement of positive/supportive or negative/stigmatizing beliefs about mental health.

Related to explanatory models of illness, the literature on mental health stigma has provided a rich empirical basis of negative beliefs, attributions, and attitudes associated with mental illness. Stigma, which is defined as either an actual or inferred attribute marked by social deviance or social disapproval (Goffman 1963), manifests itself via negative sociocultural stereotypes and prejudices that are ascribed to the mental illness itself or the person with mental illness. Research suggests that the stigma of mental illness is pervasive cross-culturally, as are its adverse effects on individuals’ life experiences and opportunities (Koro-Ljungberg and Bussing 2009; Mak and Cheung 2012; Mukolo and Heflinger 2011). Evidence also indicates, however, that the concept of stigma and its influence on individuals is culturally determined, resulting in varied understandings of what constitutes “abnormal” or “undesirable” (Mak et al. 2007; Kleinman 2004). Through shaping explanatory models of illness, culture influences the formation of specific stigmatizing beliefs and attributions regarding mental health problems.

Beliefs about mental illness that are manifested as stigma are present in three forms: public stigma, self-stigma, and courtesy or associate stigma. Public stigma, which is the most examined, is described as the shared negative beliefs and attitudes that prompt others to reject, avoid, and discriminate against individuals with mental illness (Corrigan and Miller 2004; Corrigan and Penn 1999). When stigma about mental illness is manifested within an individual, it leads to a loss of self-esteem and self-efficacy (Watson et al. 2007). Self-stigma involves a process: The individual becomes aware of the social stereotypes associated with mental illness, agrees with them, and then applies stigma to the self (Corrigan et al. 2009). Finally, courtesy or associate stigma affects those who are close to the stigmatized individual. They are devalued or socially downgraded based solely on their relationship with the individual with mental illness. These distinct forms of stigma reflect critical dimensions of beliefs about mental illness that we follow in our review of existing measures below.

Our review found of the 119 measures, 50% (60) assessed CIE domains regarding attributions and beliefs toward mental distress including: (a) illness identity beliefs regarding mental distress, (b) beliefs about characteristics or internal traits of individuals with mental distress, (c) attitudes and expected responses of individuals with mental distress, (d) agency and control beliefs of the individual with mental distress, (e) perceived norms of external responses to individuals with mental distress, and (f) beliefs about close family members or associates of individuals with mental illness (Fig. 1; Table 4).

Illness Identity Beliefs About Mental Illness/Mental Health Problems

Illness identity beliefs about mental illness were assessed by 33% (20 of the 60) measures that broadly identified two views of mental illness: (a) beliefs and attitudes regarding the legitimacy or authenticity of mental illness/mental health problems, and (b) and beliefs and attitudes about the severity, treatability, and curability of mental illness/mental health problems (Table 4). Both views encompass beliefs that directly relate to the perceived origin or cause of mental illness or mental health problems.

Of the 60 measures, 12% (7) of the measures assessed beliefs related to the legitimacy/authenticity of mental illness (Table 4). These included beliefs about mental illness as: “not a real illness or disease,” involving “fake symptoms,” invented by drug companies,” “behaviors that people engage into gain medications,” and “habitual behaviors.” These beliefs were predominantly identified in measures of stigma for specific DSM diagnoses (e.g., ADHD, generalized anxiety disorder) and not commonly found across measures. In general, these beliefs pointed to an inclination of others to minimize the authenticity of mental illness/mental health problems—a view that sharply contrasts with pervasive notions of mental illness that are characterized by visible deviations from the norm (e.g., crazy, dangerous). This is likely to demonstrate the proclivity of the lay public to perceive symptoms of schizophrenia as indicators of mental illness, and hence, ambiguity in identifying symptoms of other mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, and ADHD (Angermeyer and Dietrich 2006; Bussing et al. 2003).

Twenty-three percent (14) of the measures assessed beliefs regarding the permanency, severity, and controllability of mental illness. Measures identified the following beliefs about mental illness/mental health problems as: “a serious or severe illness,” “controllable,” “incurable,” “unable to recover from,” “will not improve if treated” and “will never get better.” These responses highlight the dichotomy in the public perception of mental illness as either: (a) a condition that is unchangeable, or (b) a condition that is changeable and under the control of the suffering individual. Beliefs regarding the controllability versus permanency of mental illness link directly to the attributed causes of mental illness, for example, biological or genetic explanations are likely to be associated with perceptions that mental illness is permanent and outside of the control or responsibility of the individual (Angermeyer et al. 2003). In contrast, a belief that mental illness can be controlled suggests that the causal factors are malleable, and further, that the responsibility of mental illness lies within the individual (Feldman and Crandall 2007). It has been noted that attributions that place responsibility outside the individual are associated with less stigmatizing beliefs and attitudes (Barrowclough and Hooley 2003) and decreases in harsh treatment (Wilcox et al. 2007); however, cultural variations appear to exist (Milstein et al. 1995).

Overall, these measures illustrate that despite the predominance of the biomedical framework in health services, lay conceptualizations of mental health tend to follow explanatory models of illness. This discrepancy in the conceptualization of mental health highlights the critical need to bridge the gap between health services and the lay individual in approaching the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness or mental health problems.

Beliefs About the Meaning of the Illness Experience to the Self

Explanatory models of illness highlight the notion that illness extends beyond biological mechanisms of pain and/or dysfunction to encompass meaning and personal impact, which are influenced by the beliefs and attitudes of the individual (Kirmayer 2001; Kleinman 1980, 1987). Individuals make meaning of their lived illness experience through the dynamic process of developing an understanding of it, then responding to this understanding through cognitive, attitudinal, emotional, and behavioral avenues. The meaning of the illness experience that is derived serves a critical foundation from which emerges the beliefs, attitudes, and actions of help seeking, as illustrated in the pathway of engagement from problem recognition, help seeking, and finally to actual engagement (Fig. 1).

Reflective of this, 78% (47) of the 60 existing measures on beliefs about mental distress assessed individuals’ interpretations of the lived illness experience of mental illness/mental health problems. The measures assessed the following dimensions of the individual’s lived illness experience: (a) beliefs about the characteristics/internal traits of the individual with mental distress, (b) attitudes and expected outcomes toward the illness experience, (c) agency or control beliefs/attitudes of the illness experience, (d) perceived norms of the (i) internal experience (beliefs about how others think of the illness experience) and (ii) external responses (beliefs about how others respond to the individual), and (e) beliefs about close family members or associates of individuals with mental illness (see Table 4).

Beliefs About Characteristics/Internal Traits of Individuals with Mental Illness or Mental Health Problems