Abstract

Research indicates that on average, children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) overestimate their competence in various domains. ADHD also frequently co-occurs with disorders involving aggressive and depressive symptoms, which themselves seem to influence estimations of self-competence in social, academic, and behavioral domains. In particular, high levels of aggressive behavior are generally associated with overestimations of competence, and high levels of depressive symptoms are related to underestimations of competence. This paper reviews studies of overestimations of competence among children with ADHD and examines the extent to which comorbid aggressive or depressive symptoms may be influencing these estimates. Although significant challenges arise due to limited information regarding comorbidities and problematic methods used to assess overestimations of competence, existing evidence suggests that ADHD may be associated with overestimations of competence over and above co-occurring aggression. As well, studies suggest that comorbid depression may reduce the appearance of overestimations of competence in children with ADHD. Underlying mechanisms (e.g., neuropsychological deficits or self-protection) of overestimations in children with ADHD are discussed, each with particular clinical implications for the assessment and treatment of ADHD. Future research would do well to carefully consider and explicitly describe the comorbid aggressive and depressive characteristics among individuals with ADHD when overestimations of competence are examined.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

On average, children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) appear to overestimate their competence in various domains compared to non-ADHD children (Owens et al. 2007). However, ADHD is frequently comorbid with other disorders, which themselves are related to inconsistencies between self-perceptions and more objective measures of competence. Thus, it is unclear whether overestimations of competence among children with ADHD may differ depending on the child’s comorbid symptomatology. This article reviews existing studies to evaluate the relationships between co-occurring aggressive and depressive characteristics and overestimations of competence by children with ADHD. First, a brief outline of ADHD and the characteristic self-perceptions associated with this disorder are presented. Then, findings indicating that aggression is linked with overestimations of competence are discussed. As well, studies showing that depressive symptoms are associated with underestimations of competence are outlined. Subsequently, studies of overestimations of competence in children with ADHD are described in detail, with attention to sample comorbidities, and a case is made for a unique link between ADHD and overestimations of competence. Finally, possible mechanisms underlying the overestimations, clinical implications, limitations of the existing research, and directions for future studies are discussed.

ADHD and Overestimations of Competence

ADHD is characterized by developmentally inappropriate levels of inattention and/or hyperactivity/impulsivity, with an estimated prevalence rate of approximately 5 % in children (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Among other difficulties, this disorder has been linked in some children to relatively extreme overestimations in self-perception. This overestimation has been named the positive illusory bias (PIB) and refers to a higher self-report of competence compared with actual competence (see Owens et al. 2007 for a review). According to Owens et al. (2007), this PIB in children with ADHD appears to be different from the positive self-illusions of typically developing individuals in that it is more extreme in terms of the divergence between perceived and actual ability, counterintuitive because children with ADHD maintain their positive self-illusions despite frequent failures, and maladaptive in its absence of association with greater persistence, motivation, or performance. In addition, the PIB is related to lowered responsiveness to behavioral treatment among children with ADHD (e.g., Mikami et al. 2010), as well as adolescent risky behavior (Hoza et al. 2013).

Previous research has used a variety of methodologies to capture the PIB (Owens et al. 2007). A few studies have used raw or absolute self-perception scores, suggesting that similar levels of self-perceived competence in children with and without ADHD are evidence of the PIB, based on the assumption that children with ADHD have lower actual competence compared to children without ADHD (e.g., Hoza et al. 1993). Relatively more studies have operationalized the PIB as a discrepancy between self-reports and more objective measures of competence (e.g., Evangelista et al. 2008; Hoza et al. 2002, 2004; Owens and Hoza 2003). This discrepancy score represents how much greater the child’s estimate of his/her own level of ability is compared with his/her actual ability level (Owens et al. 2007). More objective measures of competence are usually reports of the child by significant others (e.g., parents, teachers, and peers), or observed performance (e.g., social interactions and academic tasks). Commonly, the PIB is indexed by a standardized difference score, which addresses a psychometric weakness of unstandardized difference scores that arise from potential unequal variances in the difference score’s components (De Los Reyes and Kazdin 2004; Owens et al. 2007). A standardized difference score is calculated by first standardizing the child’s estimates and the more objective measures of competence before subtracting one from the other (De Los Reyes and Kazdin 2004; Owens et al. 2007). Yet other studies have used experimental manipulations, yielding results generally suggesting that the PIB in children with ADHD is malleable depending on the valence of feedback for task performance (Diener and Milich 1997; Ohan and Johnston 2002), that is, when positive feedback is provided to children with ADHD, their PIB appears to diminish, whereas this outcome is not the case for children without ADHD. Overall, a number of studies comparing absolute self-perceptions and difference scores between ADHD and non-ADHD children, as well as studies using experimental manipulations, demonstrate the presence of a PIB among latency-aged children with ADHD (Owens et al. 2007).

Recently, methodological and conceptual concerns have called into question the measurement of the PIB using difference scores. Specifically, Laird and Weems (2011) show that regression analyses conducted with a difference score as the predictor are equivalent to regressions conducted using the separate difference score components along with the means of the separate scores as predictors. They demonstrate that when a difference score is found to be a significant predictor in such a regression model, the correct interpretation is that there is a difference in the predictive ability of the two components that comprise the difference score, that is, unequal correlations between the predictors and the third variable are responsible for the predictive ability of the difference score. Thus, when discrepancy scores are used to indicate greater PIBs in children with ADHD compared to controls, unequal correlations of ADHD/control status with child self-reports versus with more objective measures of competence may explain the presence of a PIB, that is, the possibility exists that ADHD may not be associated with illusory biases per se, but instead that there are relatively stronger associations between measures of actual competence and ADHD status compared with the associations between child self-reports and ADHD status. Furthermore, this same problem also exists in studies using difference scores to test links between child aggression, depression, and estimations of competence.

We acknowledge this issue with the widespread use of difference scores in the literature, and note that there is often insufficient information to determine whether interpretations garnered from studies using difference scores are accurate. However, other types of evidence in the child aggression and depression literature support the interpretations based on the difference scores (Barry et al. 2011; Baumeister et al. 1996, 2000; Gladstone and Kaslow 1995). Although further research is clearly necessary to determine the veracity of the conclusions drawn from studies of over- and underestimations of competence in the child ADHD, aggression, and depression literatures, this review will consider the existing ADHD studies in order to better understand how overestimations in children with ADHD may differ depending on co-occurring symptomatology. We also note that this review will proceed by refraining from using the word “illusory” to describe the positive biases of children with ADHD, as it is often difficult to determine whether such biases are indeed illusory or rather are accurate in comparison with negatively biased reports of others. We will instead use the more neutral term, overestimations. In sum, we argue that not only are modifications needed in how we operationalize overestimations in the ADHD literature, but changes also are required in how we measure, report, and account for comorbid conditions in this body of research.

Aggression and Overestimations of Competence

Not only is ADHD in children associated with overestimates of competence, high levels of aggressive behavior also have been linked to overestimated levels of competence. This similarity between ADHD and aggressive behavior has potentially important ramifications given that disorders involving aggression are oftentimes comorbid with ADHD (Connor et al. 2010). Indeed, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD), which involve defiance, hostility, and/or aggression, have estimated prevalence rates of 60 and 20 %, respectively, in children with ADHD (Biederman 2005).

The bulk of the research that has examined overestimations of competence in association with aggression in children has focused on the domain of social functioning. These studies generally compare self-reports and other reports of the child’s social acceptance, and find that children who overestimate their level of social acceptance compared to reports offered by peers, teachers, or parents are more likely to be aggressive than children with more accurate self-perceptions. With a few exceptions (e.g., Brendgen et al. 2004; Pardini et al. 2006; Sandstrom and Herlan 2007), this result appears across children in kindergarten to grade seven and in both community (Brendgen et al. 2002, 2004; David and Kistner 2000; Diamantopoulou et al. 2008; Orobio de Castro et al. 2007; Van Boxtel et al. 2004; White and Kistner 2011) and clinic samples (Edens et al. 1999; Hughes et al. 2001).

Fewer studies have examined aggression with respect to inflated self-perceptions in domains other than social functioning. Although not universally found (e.g., Patterson et al. 1990), studies comparing self-ratings of academic competence with other reports (e.g., teachers and peers) have typically found a positive relationship between the level of aggression and overestimations of academic competence in community samples of elementary school-aged children (Hughes et al. 1997; Hymel et al. 1993). Comparisons of self- and peer evaluations of athletics and appearance, and comparisons of self- and teacher evaluations of behavioral competence also show an overestimation–aggression link in community samples of children in grades three to five (Hymel et al. 1993; Patterson et al. 1990). Overall, there appears to be an established relationship between overestimations of competence and aggression in children with the strongest evidence in the social domain. It is important to note that findings of higher self-perceptions of children with aggression documented using discrepancy scores are consistent with research using other methodologies to reveal links between enhanced self-perceptions and youth delinquency (Baumeister et al. 1996). These findings are also consistent with the theory of threatened egotism as a mechanism for violence (Baumeister et al. 2000), and the wider literature on narcissism and conduct problems in youth (see Barry et al. 2011 for a review).

Depression and Underestimations of Competence

Depressive symptoms also frequently co-occur with ADHD. Indeed, mood disorders such as major depressive disorder (MDD) are estimated to occur in up to 50 % of community samples of youths with ADHD (Angold et al. 1999). Prevalence estimates may be even higher among clinical samples (Spencer et al. 1999). In contrast to the aggression research, studies suggest that children with higher levels of depressive symptoms underestimate their competence in relation to more objective criteria, compared to children with less severe depressive symptoms. For instance, comparisons of self-rated social competence with other ratings (e.g., peers and teachers) suggest that, in community samples, school-aged children with higher levels of depressive symptoms have more negative self-perceptions in comparison with others’ perceptions of them (e.g., Brendgen et al. 2002, 2004; Kistner et al. 2006; McGrath and Repetti 2002; Rudolph and Clark 2001).

Studies also demonstrate an underestimation–depression link in the academic domain. Comparisons of self-perceptions with more objective measures of academic competence (e.g., teacher ratings and report cards) suggest that children with higher depressive symptoms have more negative self-ratings, and this link appears in community and clinic samples across children of approximately 8–13 years of age (e.g., Asarnow et al. 1987; Cole 1990; Cole et al. 1998, 1999; McGrath and Repetti 2002). In addition, depressive symptoms appear to be related to underestimations across a range of domains, including such areas as athleticism, behavioral competence, and physical appearance (e.g., Cole et al. 1998; Hoffman et al. 2000; Kendall et al. 1990). In sum, studies suggest that higher depressive symptoms are associated with children’s underestimations of competence relative to more objective measures, and this relationship appears across a number of domains of functioning. Again, we note that the lower self-perceptions of children with depression found using discrepancy score methods are consistent with other research supporting associations between depressive symptoms and negative attributional styles (see Gladstone and Kaslow 1995 for a review).

Methods

As noted above, evidence suggests that children with ADHD may overestimate their levels of competence in various areas. However, as also noted, high levels of aggressive and depressive symptoms frequently co-occur with ADHD, and are themselves associated with differences in estimations of competence. The primary purpose of this review is to comprehensively survey studies of ADHD and overestimations of competence, addressing the ways in which overestimations change with respect to comorbid aggressive and depressive symptoms. A search for studies in English of overestimations of competence in children with ADHD was conducted using the keywords “positive illusory bias” and “adhd,” “positive bias” and “adhd,” “pib” and “adhd”, and “overestimation” and “adhd” in the PsycINFO, PubMed, and Web of Science databases, limiting the results to peer-reviewed articles. As well, relevant citations from the integrative review of Owens et al. (2007) were included. Studies of participants with ADHD between the ages of 6 and 13, which employed both an ADHD and non-ADHD group, and utilized self-perception scores, were included. The baseline results of longitudinal studies were included provided that children with ADHD were between the ages of 6 and 13 at baseline. As well, if more than one study examined self-perceptions of the same domain(s) using the same sample, care was taken to report only the most relevant study. However, a lack of information in some papers means that it is possible that not all redundancies were ruled out. A total of 22 relevant studies were identified (see Table 1).

Comorbid Aggression with ADHD and Overestimations of Competence

Studies Using Absolute Scores

Studies exist comparing self-perceptions of children with ADHD to the self-perceptions of children without ADHD across such diverse domains as social competence, academic competence, behavioral conduct, physical competence, and appearance. Some of these studies use what is often termed an absolute score methodology, so as to differentiate them from studies where discrepancies between self-reports and more objective measures of competence are calculated (see Table 1). Some of these studies compare these absolute self-perceptions between ADHD and non-ADHD groups without comparing all of the relevant actual competence levels of the two groups (e.g., Hoza et al. 1993; Treuting and Hinshaw 2001; Whalen et al. 1991), while others compare absolute self-perceptions as well as the related actual competencies of the children with and without ADHD (e.g., Horn et al. 1989; Ialongo et al. 1994; Milich and Okazaki 1991; Ohan and Johnston 2002).

Results found by studies using these two methodologies are somewhat mixed, but mostly support the possibility that children with ADHD overestimate their competence compared to children without ADHD. Findings using absolute self-perception scores without measuring the relevant actual competencies show that children with and without ADHD generally do not differ in their self-perceptions (e.g., Hoza et al. 1993; Treuting and Hinshaw 2001). One study did show that a significantly larger number of boys with ADHD overestimated their performance compared to boys without ADHD, but only half of the time (Whalen et al. 1991). Studies in which absolute self-perceptions and the relevant actual competence levels are compared between ADHD and non-ADHD groups demonstrate lower self-perceptions and lower actual competence in the ADHD group in contrast to the control group (Horn et al. 1989; Ialongo et al. 1994), no differences in self-perceptions despite lower actual competence in the ADHD group as compared to the control group (Hoza et al. 2001; Milich and Okazaki 1991; Ohan and Johnston 2002), or that children with ADHD have more positive self-evaluations than children without ADHD despite poorer performance (Hoza et al. 2000). It is important to note that these comparisons are based on group means, and as such they may obscure important individual differences among children. Although the bulk of the results suggests that children with ADHD as a whole hold self-perceptions inconsistent with their true performance, findings remain somewhat mixed. This heterogeneity of results may be due, in part, to a lack of consideration of the influence of comorbidities within the ADHD samples.

Only two of the studies solely using absolute self-perceptions have taken into account the influence of comorbidities on self-perceptions (Ohan and Johnston 2002; Treuting and Hinshaw 2001). Ohan and Johnston (2002), who found that boys with and without ADHD had similar levels of estimations of performance despite the fact that boys with ADHD had lower levels of actual competence, did not find any difference in performance estimates offered by boys with ADHD and comorbid ODD compared to boys with ADHD only. This finding suggests a unique ADHD–overestimation link beyond comorbidities; however, the ADHD versus ADHD/ODD comparison may have been weakened by a lack of power as only 15 of the 45 boys in the ADHD sample did not have ODD. In a similar manner, Treuting and Hinshaw (2001) directly examined the influence of comorbidities on differences in self-perceptions with the ADHD sample split into boys with ADHD + aggression and those with ADHD only. These two groups were compared to a non-ADHD group. The ADHD-only group and the non-ADHD group did not differ in estimations of competence in most domains, whereas the ADHD + aggression group had lower self-perceptions in most domains compared to the other groups. Although the lower self-perceptions of those with ADHD + aggression are unexpected given the literature on aggression and overestimations of competence, it is important to note that Treuting and Hinshaw did not control for the simultaneous presence of depressive symptoms that were more common in the ADHD + aggression group compared to the ADHD-only group. In the context of prior literature suggesting that children who are high on both aggressive and depressive symptoms may have generally negative self-perceptions (e.g., Hymel et al. 1993; Rudolph and Clark 2001; Schneider and Leitenberg 1989), it is possible that comorbid depressive symptoms overrode the influence of aggression on estimations of competence in Treuting and Hinshaw’s sample.

The majority of other studies using absolute self-perceptions, although not controlling for comorbid conditions in the analyses, did measure comorbid aggression, ODD, CD, or externalizing difficulties in their ADHD samples. For instance, 92 % of the boys in Hoza et al.’s (1993) ADHD sample had either comorbid ODD or CD, in contrast to the control group of children, who did not have behavior problems of any kind. Along the same line, in both studies from the Horn and Ialongo group (Horn et al. 1989; Ialongo et al. 1994), the children with ADHD had significantly higher levels of aggression or conduct problems than the children without ADHD. As well, the ADHD groups in the studies conducted by Hoza et al. (2000) and Hoza et al. (2001) had significantly more externalizing difficulties than the non-ADHD groups. Such between-group differences underscore the importance of controlling for comorbidities in studies of overestimations of competence in ADHD samples and point to the difficulties in interpreting the results from these studies as supporting a unique link between ADHD and overestimation.

Studies Using Discrepancy Scores

Along with the lack of control for aggression or ODD/CD comorbidities, absolute self-perception studies also fail to explicitly account for the specific competence level of each child, making it difficult to interpret the individual reality of the self-perceptions. Thus, we turn to the examination of these comorbidities with ADHD in studies using discrepancies between self-ratings and more objective measures of competence specific to each child (see Table 1). Among the studies using a discrepancy score approach to study overestimations among children with ADHD, some do not report the aggression-related comorbidities of their samples (e.g., O’Neill and Douglas 1991). However, the majority do report aggression or aggression-related comorbidities (Emeh and Mikami 2012; Hoza et al. 2012; McQuade et al. 2011; Owens and Hoza 2003; Rizzo et al. 2010) and most show at least indirect evidence of a positive correlation between the presence of aggressive comorbidity and overestimations of competence among children with ADHD. For instance, Owens and Hoza (2003) found that children with either primarily hyperactive/impulsive or both inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive ADHD symptoms overestimated their academic competence more than children without ADHD. In contrast, children with primarily inattentive ADHD symptoms generally did not overestimate their competence. Of particular relevance, the children with hyperactive/impulsive symptoms also had significantly higher levels of ODD and CD symptoms compared to the inattentive group, suggesting that aggression may play some role in accounting for the overestimations of competence in children with hyperactive/impulsive ADHD symptoms. Interestingly, when examining aggression within an ADHD sample that was limited to children with hyperactive/impulsive symptoms, both Linnea et al. (2012) and McQuade et al. (2011) found no differences in ODD, CD, or externalizing symptoms between groups of children with ADHD who did and did not overestimate their competence, possibly due to a restriction of range of aggression-related symptoms. Further evidence for the possible influence of aggression on overestimations was found by Rizzo et al. (2010), who used a non-aggressive ADHD sample, and found no overestimation differences between children with and without ADHD in areas of self-regulation.

Although several studies have used discrepancy scores to compare the overestimations of children with and without ADHD across a variety of domains, only a few have controlled for or directly examined the influence of comorbid aggressive symptoms or aggression-related disorders in analyses of the relationships between ADHD and overestimations of competence (e.g., Evangelista et al. 2008; Hoza et al. 2002, 2004; Ohan and Johnston 2011). The studies that do include ODD or CD in their analyses suggest that overestimation remains associated with ADHD, even after taking these comorbid conditions into account. For instance, Evangelista et al. (2008) found that children with ADHD overestimated across various domains compared with non-ADHD children, and that after controlling for ODD and CD, only one of the differences in ratings of overestimations became nonsignificant, suggesting that ADHD may be linked to overestimations, at least in some domains, independent of comorbid aggression. Similar results were obtained by Ohan and Johnston (2011), who found that ADHD/high ODD girls overestimated more than either ADHD/low ODD or typical girls, but the ADHD/low ODD group still overestimated compared with the typical group. These findings suggest an association between ADHD and overestimations that remains despite the positive correlation between ODD symptoms and overestimations. In addition to considering comorbid ODD or CD, studies taking into account comorbid aggression appear to yield similar findings that show both higher aggressive levels associated with greater overestimations among children with ADHD, as well as an association specific to ADHD and overestimation. For instance, in two separate studies, Hoza et al. (2002, 2004) found that although children with ADHD overestimated their competence compared to non-ADHD children regardless of whether they also evidenced aggressive symptoms across many domains, children with ADHD/high aggression overestimated themselves more than those with ADHD/low aggression in certain domains (i.e., social and/or behavioral).

Summarizing across studies of overestimations in children with ADHD, most do not directly assess the influence of comorbid aggression with ADHD on overestimations of competence. Those that do yield findings that support a unique relationship between ADHD and overestimations of competence independent of aggression levels. However, at the same time, aggressive levels appear to be associated with higher overestimations of competence.

Comorbid Depression with ADHD and Estimations of Competence

Studies Using Absolute Scores

The association of comorbid depressive symptoms with ADHD in relation to children’s estimations of competence was studied by examining research using absolute assessments of children’s reported competence as well as studies using discrepancy scores comparing self-reports to more objective competence measures (see Table 1). Although most studies comparing absolute self-perceptions of children with ADHD to children without ADHD do not directly control for depressive symptoms, some do report information regarding the depressive or internalizing difficulties in their samples. These studies generally indicate higher internalizing or depressive difficulties in children with ADHD compared to those without ADHD (e.g., Horn et al. 1989; Hoza et al. 2000, 2001; Ialongo et al. 1994; Treuting and Hinshaw 2001). Only one study that solely used absolute self-perception scores of competence controlled for co-occurring internalizing symptoms (Hoza et al. 1993). Hoza et al. found that the self-perceptions of children with ADHD generally increased when comorbid internalizing symptoms were covaried, suggesting a negative relationship between comorbid internalizing difficulties, which includes depressive symptoms, and estimations of competence.

Studies Using Discrepancy Scores

Next, we turn to studies that have examined the possible influence of internalizing symptoms in studies using discrepancies between self-ratings and actual levels of competence. Some of these studies included no measurement of depressive symptoms in the children with ADHD (e.g., Diener and Milich 1997; Evangelista et al. 2008; O’Neill and Douglas 1991). In a study by McQuade et al. (2011) that did not directly control for, but did measure, depressive symptoms, children with ADHD who did not overestimate their competence were found to have more depressive symptoms than children without ADHD. As well, it was found that children with ADHD who did and did not overestimate differed in their levels of depressive symptoms. This finding, however, is tempered by Linnea et al.’s (2012) result of no differences in internalizing symptoms between overestimators and non-overestimators in children with ADHD.

A few studies have controlled for comorbid depressive symptoms in studying ADHD and overestimations of competence. Owens and Hoza (2003) controlled for depressive symptoms in the context of hierarchical multiple regressions of ADHD symptoms on overestimations, but did not report the results of their regression analyses without controlling for depressive symptoms, and therefore, it is difficult to ascertain whether controlling for comorbid depressive symptoms affected their results. Similarly, Hoza et al. (2012) controlled for depressive symptoms in their analyses, but did not report their results without controlling for depressive symptoms. They did find, however, that higher depressive symptoms were associated with reduced overestimations of competence. Studies directly investigating the influence of comorbid depressive symptoms with ADHD on overestimations of competence found that children with ADHD/low depressive symptoms showed greater overestimations than children with ADHD/high depressive symptoms in the academic and social domains, and that the estimations of those with ADHD/high depressive symptoms did not differ from, or tended to be closer in value to, those of children without ADHD in certain domains (Hoza et al. 2002, 2004; Ohan and Johnston 2011). Although Swanson et al. (2012) did not find any differences in overestimations between ADHD girls with or without MDD/dysthymic disorder, they did find in dimensional analyses that higher depressive symptoms were associated with lower overestimations among girls with ADHD. Across the studies, comorbid depressive symptoms appear to attenuate the overestimations of competence associated with childhood ADHD.

Overall, few studies actually directly evaluate the influence of comorbid depressive symptoms on overestimations of competence in children with ADHD. Those studies that measured depressive symptoms in their samples generally show a negative association between overestimations of competence and depressive symptoms. Further, the majority of studies that directly control for depressive symptoms point to the possibility that comorbid depressive symptoms serve to reduce these children’s estimations (or overestimates) of their competence. In other words, it appears that children with ADHD and comorbid depressive symptoms show diminished levels of overly positive self-perceptions of competence and may have self-perceptions of competence comparable to non-ADHD children.

Table of Studies of Overestimations in Children with ADHD

Table 1 outlines the reviewed studies of overestimations of competence in children with and without ADHD. Study citations are presented, along with headings describing the main measure of overestimation that was used, whether child aggressive and depressive symptoms were considered or controlled, and if so, the constructs used for control, and whether controlling for these constructs changed the results regarding ADHD and overestimations of competence. To allow for accurate interpretation of the table, some parts require further clarification. For the measure of overestimation, although the primary measure of overestimation used in the study is reported in the table, it is acknowledged that several studies used more than one measure (i.e., both absolute and discrepancy scores, e.g., Diener and Milich 1997; Hoza et al. 2002, 2012; Owens and Hoza 2003; Evangelista et al. 2008; Rizzo et al. 2010; McQuade et al. 2011; Ohan and Johnston 2011; Linnea et al. 2012; Swanson et al. 2012). With respect to controlling for child aggressive and depressive symptoms, it is also recognized that some studies did not control for these symptoms but did measure the associations of these symptoms to their dependent variables and found no need to control for them as covariates. In addition, we used the term control to include studies that treat aggressive or depressive symptoms as covariates as well as studies that compare groups that are high and low on these symptoms. However, for the purposes of this table, controlling for aggressive or depressive symptoms was not defined to include control groups that had purposely been screened for these symptoms, nor does it include selecting an ADHD sample that was non-aggressive or not depressed. In terms of whether controlling for aggressive or depressive symptoms led to a change in results, an unknown was recorded in the table for those studies (i.e., Emeh and Mikami 2012; Hoza et al. 2012; McQuade et al. 2011; Owens and Hoza 2003) that controlled for these symptoms but did not investigate whether such control altered the results regarding the associations between ADHD and overestimations of competence.

Discussion

On average, ADHD in children has been consistently linked to overestimations of self-competence, typically called the PIB. As well, ADHD is characterized by high rates of comorbidities with both aggression and depressive symptoms, which are themselves associated with overestimations and underestimations of competence. The degree to which overestimations or underestimations of competence are associated with ADHD per se is therefore unclear, and aggressive and depressive comorbidities are often not taken into account in studies of overestimations in children with ADHD. The purpose of this review was to examine the ways in which self-reported estimations of competence differed depending on the comorbid aggressive and depressive characteristics of children with ADHD.

Our review of studies of overestimations in children with ADHD generally suggested that co-occurring aggression and depressive symptoms influence overestimations in expected ways. Comorbid aggression inflates, and co-occurring depressive symptoms attenuate, overestimations of competence in children with ADHD. The overestimation commonly observed in aggressive children is consistent with the threatened egotism model, which proposes that aggression occurs as a self-protective response to stimuli that threaten positive self-illusions (Baumeister et al. 2000). The overestimations of children with aggression may therefore serve a self-protection purpose, allowing these children to continue to hold a positive view of themselves in the face of consistent and threatening feedback regarding their incompetence. In contrast to the overestimations typical of children who are aggressive, children with elevated levels of depressive symptoms tend to underestimate their competence, consistent with the larger body of evidence on depressogenic cognitions including negative views of the self (e.g., Gladstone and Kaslow 1995). However, many of the reviewed studies also support the presence of a unique association between ADHD and overestimations of competence, irrespective of the presence of aggressive or depressive symptoms. That is, in addition to the expected inflating influence of aggression and deflating influence of depression, there remains a significant association between ADHD diagnoses or symptoms and children’s tendency to overestimate their levels of competence.

We speculate that the independent association between ADHD and overestimations of competence may be fueled by a need for self-protection among those with ADHD, similar to the mechanism of threatened egotism attributed to individuals with high levels of aggression (Baumeister et al. 2000). Certainly, the abundance of severe impairments that children with ADHD regularly experience in various significant life domains (American Psychiatric Association 2013) could be argued to contribute to a defensive or protective style of perceiving or reporting one’s own abilities. Consistent with this argument, it appears that children’s overestimations are highest for their most impaired domains of competence (Hoza et al. 2002, 2004). Instead of realistically assessing or describing one’s deficiencies, and suffering the negative affect that would be an almost inevitable result, children with ADHD may instead hold and/or report inflated self-views as a means of averting the negative consequences of an accurate self-view (see Owens et al. 2007 for further description). Self-perceptions as influenced by a need for self-protection may be similar to impression management or a social desirability bias. Indeed, Ohan and Johnston (2002, 2011) demonstrated that scores on a measure of social desirability were positively correlated with overestimations of social competence in children with ADHD. Further support for the self-protection hypothesis comes from studies that show that, at least in the social domain, when the need for self-protection is lower, overestimations of competence diminish. Specifically, Diener and Milich (1997) as well as Ohan and Johnston (2002) demonstrated that children with ADHD lowered their overestimations of competence after having received positive feedback on a social task, which differed from control children who increased their self-ratings of competence when given positive feedback. Presumably, the positive feedback created a “safer” environment for the children with ADHD and thus served to lower their need for self-protective defensiveness. In sum, the findings of the studies conducted testing the self-protection hypothesis provide some support for the idea that children with ADHD hold overly positive self-perceptions due to a need to self-protect.

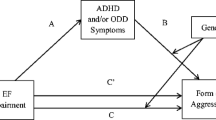

An alternative explanation for the relationship between ADHD and overestimations of competence involves the influence of neuropsychological deficits on self-perceptions. ADHD has been associated with various executive function impairments (e.g., Barkley 1997; Oosterlaan et al. 2005; Willcutt et al. 2005), and these impairments may be associated with a lack of self-awareness that in turn may account for the overestimations of competence (Owens et al. 2007). This lack of self-awareness in children with ADHD may result from the inability to attend to self-evaluative information and/or appraise such information in relation to the self, leading to possible inaccuracies in self-perceptions. A number of executive function deficits are related to ADHD (Willcutt et al. 2005). One could speculate how deficits in working memory could lead to reduced attention to self-relevant feedback, how an inability to inhibit prepotent responses may be related to difficulty in subsuming self-relevant negative feedback in the face of a need to see oneself in a positive light, or how an incapacity in mental flexibility may be linked to an inability to incorporate negative self-evaluative feedback that does not fit into a preexistent positive cognitive schema of the self. In addition to research that demonstrates lack of insight or self-awareness in individuals with cognitive deficits stemming from acquired brain injury (Ownsworth et al. 2002) or possible Alzheimer’s (Barrett et al. 2005), research shows that deficiencies in insight are specifically associated with deficits in executive function tasks in adult populations (e.g., Bivona et al. 2008; Hart et al. 2005; Shad et al. 2006). Most relevant to the ADHD and executive functioning link, a study by McQuade et al. (2011) found that children with ADHD who overestimated their competence generally had greater executive functioning deficits than children with ADHD who did not overestimate their competence. In addition, these executive functions were partial mediators in the relationship between overestimations and ADHD status.

While the neuropsychological deficit hypothesis implies that children with ADHD are unaware of their impairments, it is unclear whether the self-protection hypothesis indicates that children with ADHD consciously overestimate due to an explicit need for self-protection or if these overestimations are less intentional and operating at a more automatic, covert level. The recent finding of Hoza et al. (2012) that children with ADHD provided lower overestimations for some domains when provided incentives to match their self-ratings with the ratings of their teachers suggests that children’s overestimations may be at a more explicit level. However, Hoza et al. (2012) also found that children with ADHD were unable to fully normalize their overestimations compared to children without ADHD even under incentive conditions, which indicates that at least part of the overestimations may be outside of the child’s volition. Thus, the inability to provide accurate overestimations may stem from either an implicit need for self-protection or from neuropsychological deficits in self-awareness, and the boundary between the self-protection and neuropsychological deficit hypotheses becomes blurred. One can think of a child who, due to a desire to self-protect, chooses not to attend to negative self-evaluative information in the environment and through time becomes habitually unaware of such negative feedback. In this example, over time, explicit self-protection becomes implicit and difficult to distinguish from lack of self-awareness due to neuropsychological deficits.

Further adding to the complexity of explanations for overestimations of competence is the possibility that the self-protection and neuropsychological deficit mechanisms may not be mutually exclusive, and that both may underlie the overestimations of children with ADHD. Children with ADHD may have impairments in integrating negative self-relevant feedback and may also possess a self-protective style. Both of these deficits may occur within the same child, and the extent to which each of these deficits accounts for overestimations of competence may vary across children. Studies show that children with ADHD have greater overestimations in areas in which they are more severely impaired (Hoza et al. 2002, 2004; McQuade et al. 2011). It is not difficult to explain this finding in terms of the self-protective or neuropsychological deficit hypotheses. Indeed, it seems reasonable to expect that children may be more self-protective in areas in which they are more severely impaired and also reasonable to predict that children with greater deficits may have greater neuropsychological impairment, which may then drive overestimations. Another possibility could be that the mechanism driving overestimations of competence differs depending on the circumstances. For instance, children may be more consciously self-protective in domains that are more important to them, while they may not be as self-protective in less self-important domains. As well, children may possess a greater lack of self-awareness in domains where the feedback they receive about their performance is less defined or more ambiguous (e.g., social interactions) and more self-awareness in domains with clearer feedback (e.g., academics). Studies have yet to test the contextual factors that may affect these mechanisms. In sum, the self-protective and the neuropsychological deficit accounts of overestimations of competence may not be independent of one another and may function jointly to explain overestimations of competence. As well, the degree to which these two mechanisms explain overestimations of competence in children with ADHD may differ depending on the particular child as well as the specifics of the circumstances.

We turn now to consideration of how the presence of comorbid aggression appeared to exacerbate overestimations among children with ADHD. First, such an increase in overestimations is consistent with research showing that children with ADHD and comorbid ODD/CD seem to possess more serious features of ADHD and ODD/CD compared to those with ADHD or ODD/CD alone (e.g., greater ADHD symptoms, an earlier onset of antisocial behavior, more stable antisocial conduct, and greater parental psychopathology; Connor and Doerfler 2008; Hinshaw 1987; Retz and Rösler 2009). Similar to the greater symptom and functional severity attributed to the comorbidity of ADHD and aggressive disorders, the overestimations of children with ADHD and aggression are also higher than those in children with either disorder alone (e.g., Hoza et al. 2002, 2004; Ohan and Johnston 2011). The heightened overestimations of those with ADHD and co-occurring aggression may be due to the self-protection motivations stemming from both conditions combining to form an even greater need to self-protect. Alternatively, given that executive functioning deficits have been found to be more closely associated with ADHD than ODD/CD (e.g., Oosterlaan et al. 2005), the finding that comorbid aggression with ADHD is related to greater overestimations may be explained by the combined influences of a self-protective mechanism associated with aggression and executive function deficits of ADHD. Research comparing the executive function profiles and self-protective biases (e.g., using social desirability measures) of children with ADHD and comorbid aggression to groups of children with ADHD alone and aggression alone may aid in better understanding the underlying mechanisms of overestimations in children with both ADHD and aggression. Such studies may help disentangle whether the heightened overestimations of children with ADHD and co-occurring aggression, compared to children with ADHD alone, are driven by greater self-protective motivations, exacerbated executive functioning difficulties, or a combination of self-protective biases and executive function weaknesses.

Interestingly, in the studies reviewed, children with ADHD and comorbid depressive symptoms typically offered estimations of their competence that were comparable to those provided by children without ADHD. Such an attenuation of overestimations is in contrast to the underestimations expected in children with elevated depressive symptoms alone (e.g., Cole et al. 1998; Hoffman et al. 2000; Kendall et al. 1990). In a sense, ADHD appears to buffer against underestimations of competence among those who are simultaneously experiencing problems of depression. Given that depression is associated with a negative attribution bias that does not favor the self, if the primary mechanism behind the ADHD–overestimation link is self-protection, then these opposing self-protective and self-deprecating biases may in effect “cancel” each other out in the estimations of children with ADHD and comorbid depression. An alternative, but non-exclusive, possibility is that ADHD-related neuropsychological deficits, which are responsible for an absence of self-awareness, are pitted against a depression-related self-deprecating style. It seems unlikely that ADHD and high depressive symptoms both primarily contribute executive functioning difficulties related to a lack of self-awareness, as such a combination of mechanisms would not predict reduced overestimations. Indeed, research on other populations with impaired executive functions shows links between executive function deficits and overestimations, rather than underestimations of self-perceptions (e.g., Barrett et al. 2005; Shad et al. 2006; Starkstein et al. 2006). To address these differing hypotheses of mechanisms, research on the executive function profiles as well as the need for self-protection (again, perhaps by using social desirability measures) in children with ADHD and depression as compared to children with ADHD alone and depression alone would contribute to a better understanding of the explanations for overestimations in children with both ADHD and depressive symptoms.

Conclusion

Research at present suggests a unique relationship between ADHD and overestimations of competence, although these overestimations are influenced by comorbid aggression and depressive symptoms. Specifically, co-occurring aggression with ADHD is associated with inflated overestimations of competence, while concurrent elevated depressive symptoms are related to estimations of competence no different from children without ADHD. The failure to take comorbid conditions into account in studies of overestimations of competence in children with ADHD has limited our existing knowledge of the nature of overestimations of competence and stands as an impediment to understanding the mechanisms that may underlie overestimations in children with ADHD. Given the effects of comorbid conditions such as aggression and depressive symptoms on self-perceptions, such symptoms need to be taken into account by future studies in order to move the literature on overestimations in children with ADHD forward. These considerations must also be undertaken in light of the limitations of the statistical use of the analysis of covariance under conditions of non-random assignment to groups (e.g., Miller and Chapman 2001).

Limitations and Future Directions

Firstly, the conclusions drawn from our review remain relatively tentative due to the paucity of studies that control for the influence of comorbidities with ADHD on overestimations of competence. Future studies must be more explicit in identifying and investigating the effects of comorbid aggression and depressive symptoms on estimations of competence. Covarying for aggressive and depressive symptoms would allow for a better understanding of how overestimations of competence relate to ADHD per se, and may also clarify questions about the mechanisms of overestimations without possible confounding mechanisms stemming from comorbidities. As previously mentioned, studies of the mechanisms of estimations of children with aggression and depression alone would be helpful to better understand how these mechanisms operate in the context of overestimations of children with ADHD and aggression or depression.

In addition, the results of this review must be interpreted with some caution due to methodological weaknesses in the measurement of overestimations of competence in many existing studies (e.g., Laird and Weems 2011). As such, it is possible that the unique ADHD–overestimation link and the exacerbating association of comorbid aggression with overestimations are, at least in part, attributable to the lower actual competence levels in children with ADHD and comorbid aggression compared to children with ADHD without comorbid aggression (e.g., Abikoff et al. 2002; Connor and Doerfler 2008; Connor et al. 2003; Hinshaw and Melnick 1995). However, children with ADHD and comorbid depression are also characterized by marked impairments (e.g., Daviss 2008) over and above those of either disorder alone, but these children do not appear to have high overestimations of competence. Therefore, the explanation of lower impairment driving the relationships between overestimations of competence and ADHD and comorbidity status does not serve to provide a full explanation of these effects. Nevertheless, future research would do well to bolster these interpretations by using other ways to address the methodological weaknesses of difference scores. For instance, Laird and De Los Reyes (2013) recommend the use of interaction terms in polynomial regression analyses to better understand the relationships between informant discrepancies and psychopathology. As well, studies could utilize designs in which actual performance is held constant between groups (e.g., ADHD and control groups) while measuring differences in self-perceptions of such performance. Further, in testing the self-protective hypothesis, researchers may investigate differences between implicit and explicit self-esteem between ADHD and non-ADHD groups (e.g., by using the implicit association test) to determine whether discrepancies between these different types of self-esteem in the ADHD group are consistent with self-protection.

As well, the existing studies that do report and/or control for comorbid aggression and depressive symptoms have used non-uniform methods for the measurement of these comorbid conditions. For instance, some studies report the numbers of children who meet DSM diagnostic criteria for disruptive behavior or mood disorders, while others report the number of children in their sample with clinically significant levels of internalizing or externalizing symptoms. Examining broad categories of internalizing and externalizing disorders can make it difficult to tease apart whether depression and aggression in particular are associated with changes in overestimations of competence. In addition, high comorbidity across disorders may be confounding results. For instance, it is possible that anxiety, rather than depression, may be associated with reductions in overestimations. While a variety of levels and methods of measurement is likely optimal at this relatively early stage of research to prevent missing important information regarding the specificities of comorbidities and their influences on overestimations, future studies must take care to explicitly detail the criteria used to characterize the aggression and depressive symptoms of children with ADHD and clarify whether dimensional or categorical approaches to studying these comorbidities are most helpful.

Another important direction for future studies will be to assess estimations of competence among children with the confluence of all three conditions of ADHD and comorbid aggression and depression, given prior research showing that depressive symptoms among aggressive children decrease overestimations (e.g., Hymel et al. 1993; Rudolph and Clark 2001; Schneider and Leitenberg 1989). Thus, it may be that children with ADHD, aggression, and depression may continue to show overestimations compared to controls. Such a finding would provide further support for the unique link between ADHD and overestimations of competence. Moreover, studies comparing the self-perceptions of children with only depression or aggression to those of children with ADHD with and without these comorbid conditions may be helpful in better clarifying the links between ADHD and overestimations of competence, although such samples may be difficult to find. In addition, as the literature on overestimations of competence in children with ADHD matures, further studies are needed to explore the relations of other comorbid conditions, such as anxiety, to such self-perceptions, as well as to explore which domains of competence are most affected by comorbidities.

It also is important to clarify the associations between gender and overestimations of competence in individuals with ADHD. Given that aggression is more common in males than females (Lahey et al. 2000), and depression is higher in females than males at least during adolescence and adulthood (Kessler et al. 1993; Nolen-Hoeksema 2001), it is possible that lower overestimations of competence are primarily found in samples of females with ADHD and higher overestimations are representative of males with ADHD. However, at least for depression, research indicates that this gender imbalance is not as strong for preadolescents (Hankin et al. 1998; Nolen-Hoeksema and Girgus 1994) and thus is unlikely to account for the findings. In addition, studies directly examining, and demonstrating, differential relationships between comorbid depressive and aggressive symptoms on overestimations of competence have either utilized single-gender ADHD samples (Hoza et al. 2002; Ohan and Johnston 2011), or have examined gender as a moderator of overestimations (Hoza et al. 2004), suggesting that gender is unlikely to be confounding these findings. However, further studies are needed to better disentangle the influence of gender differences on the associations between co-occurring aggression and depression and overestimations in children with ADHD.

In addition to gender, the influence of ADHD subtypes is important to consider. For instance, research suggests that the ADHD combined subtype is more strongly associated with externalizing disorders compared to the primarily inattentive ADHD subtype (e.g., Eiraldi et al. 1997), which in turn is more strongly linked to depression (e.g., Faraone et al. 1998). Consistent with this, overestimations have been found by one study to be more strongly associated with the hyperactive/impulsive or combined subtypes of ADHD than with the inattentive subtype (Owens and Hoza 2003). In contrast, other studies have continued to find differential relationships between co-occurring aggression and depressive symptoms with ADHD and overestimations despite controlling for ADHD subtype by either utilizing samples comprised of only one subtype (i.e., combined subtype; Hoza et al. 2004), or covarying for subtype (Ohan and Johnston 2011). These divergent results argue that moving forward, it would be prudent to consider ADHD subtypes in assessing the influence of comorbid conditions on overestimations of competence.

Finally, using longitudinal designs to study the ways in which overestimations endure over time for those with ADHD and comorbid disorders may also contribute to better understanding the mechanisms involved in the self-perceptions of this population through the life span. Existing longitudinal studies of self-perceptions among youth with ADHD suggest that decreases in positive self-perceptions are associated with depressive symptoms, and that increases in overestimations are associated with aggressive symptoms in particular domains (e.g., Hoza et al. 2010; McQuade et al. 2011; Murray-Close et al. 2010). A few cross-sectional studies have examined overestimations of competence in adults with ADHD (e.g., Jiang and Johnston 2012; Knouse et al. 2005; Knouse et al. 2006), yielding conflicting results. Similar to the child literature, most of these studies either did not measure or did not control for both comorbid aggressive and depressive conditions in understanding the association between ADHD and overestimations. Such lack of measurement and/or control for both aggressive and depressive symptoms may have contributed to the conflicting results.

Clinical Implications

From a clinical standpoint, our review suggests first that overestimations are, on average, characteristic of children with ADHD, regardless of coexisting conditions. However, the findings also point to the necessity of accounting for comorbid aggressive and depressive symptoms of children in interpreting the overestimations of child self-reports. It is important to be cognizant of the greater tendency toward overestimations of self-competence among children with both ADHD and high aggressive levels, as well as the greater inclination to be more accurate in self-ratings among those with ADHD and elevated depressive symptoms.

Overestimations of competence are likely maladaptive (e.g., Mikami et al. 2010). In terms of management, understanding the mechanisms underlying the overestimations seems to be a key. For instance, if the self-protective hypothesis is the primary underlying mechanism for these overestimations, then they may be reduced by bolstering children’s self-esteem (e.g., through the use of positive feedback or mastery experiences) and by attempting to improve their actual levels of competence and social acceptance (e.g., behavioral management and skills training). Alternatively, if neuropsychological deficits in executive functioning mainly underlie the overestimations of competence, a focus on increasing levels of executive functioning, through medication or executive function training programs (e.g., Klingberg et al. 2002), may be critical to improve self-awareness. If both self-protection and neuropsychological deficits are operating to enhance self-perceptions, a two-pronged approach may be most appropriate. Although the true clinical impact of these overestimations awaits further testing, it is clear from this review that awareness of the potential for overestimations of competence among children with ADHD and the influences of comorbidities on these estimations will be useful to clinicians in interpreting information from children’s self-reports and in planning strategies to enhance the competence of children with ADHD.

References

Abikoff, H. B., Jensen, P. S., Arnold, L. L. E., Hoza, B., Hechtman, L., Pollack, S., et al. (2002). Observed classroom behavior of children with ADHD: Relationship to gender and comorbidity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30, 349–359. doi:10.1023/A:1015713807297.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

Angold, A., Costello, J., & Erkanli, A. (1999). Comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40, 57–88. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00424.

Asarnow, J. R., Carlson, G. A., & Guthrie, D. (1987). Coping strategies, self-perceptions, hopelessness, and perceived family environments in depressed and suicidal children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55, 361–366. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.55.3.361.

Barkley, R. A. (1997). Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: Constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychological Bulletin, 121, 65–94. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.65.

Barrett, A. M., Eslinger, P. J., Ballentine, N. H., & Heilman, K. M. (2005). Unawareness of cognitive deficit (cognitive anosognosia) in probable AD and control subjects. Neurology, 64, 693–699. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000151959.64379.1B.

Barry, T. D., Grafeman, S. J., Bader, S. H., & Davis, S. E. (2011). Narcissism, positive illusory bias, and externalizing behaviors. In C. T. Barry, P. K. Kerig, K. K. Stellwagen, & T. D. Barry (Eds.), Narcissism and machiavellianism in youth (pp. 159–173). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Baumeister, R. F., Bushman, B. J., & Campbell, W. K. (2000). Self-esteem, narcissism, and aggression: Does violence result from low self-esteem or from threatened egotism? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9, 26–29. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.219.

Baumeister, R. F., Smart, L., & Boden, J. M. (1996). Relation of threatened egotism to violence and aggression: The dark side of high self-esteem. Psychological Review, 103, 5–33. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.103.1.5.

Biederman, J. (2005). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A selective overview. Biological Psychiatry, 57, 1215–1220. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.020.

Bivona, U., Ciurli, P., Barba, C., Onder, G., Azicnuda, E., Silvestro, D., et al. (2008). Executive function and metacognitive self-awareness after Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 14, 862–868. doi:10.1017/0S1355617708081125.

Brendgen, M., Vitaro, F., Turgeon, L., & Poulin, F. (2002). Assessing aggressive and depressed children’s social relations with classmates and friends: A matter of perspective. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30, 609–624. doi:10.1023/A:1020863730902.

Brendgen, M., Vitaro, F., Turgeon, L., Poulin, F., & Wanner, B. (2004). Is there a dark side of positive illusions? Overestimation of social competence and subsequent adjustment in aggressive and nonaggressive children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32, 305–320. doi:10.1023/B:JACP.0000026144.08470.cd.

Cole, D. A. (1990). Relation of social and academic competence to depressive symptoms in childhood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 99, 422–429. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.99.4.422.

Cole, D. A., Martin, J. M., Peeke, L. A., Seroczynski, A. D., & Fier, J. (1999). Children’s over- and underestimation of academic competence: A longitudinal study of gender differences, depression, and anxiety. Child Development, 70, 459–473. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00033.

Cole, D. A., Martin, J. M., Peeke, L. G., Seroczynski, A. D., & Hoffman, K. (1998). Are cognitive errors of underestimation predictive or reflective of depressive symptoms in children: A longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107, 481–496. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.107.3.481.

Connor, D. F., & Doerfler, L. A. (2008). ADHD with comorbid oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder; discrete or nondistinct disruptive behavior disorders? Journal of Attention Disorders, 12, 126–134. doi:10.1177/1087054707308486.

Connor, D. F., Edwards, G., Fletcher, K. E., Baird, J., Barkley, R. A., & Steingard, R. J. (2003). Correlates of comorbid psychopathology in children with ADHD. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 42, 193–200. doi:10.1097/01.CHI.0000024918.60748.B0.

Connor, D. F., Steeber, J., & McBurnett, K. (2010). A review of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder complicated by symptoms of oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 31, 427–440. doi:10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181e121bd.

David, C. F., & Kistner, J. A. (2000). Do positive self-perceptions have a “dark side”? Examination of the link between perceptual bias and aggression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 28, 327–337. doi:10.1023/A:1005164925300.

Daviss, W. B. (2008). A review of co-morbid depression in pediatric ADHD: Etiologies, phenomenology, and treatment. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 18, 565–571. doi:10.1089/cap.2008.032.

De Los Reyes, A., & Kazdin, A. E. (2004). Measuring informant discrepancies in clinical child research. Psychological Assessment, 16, 330–334. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.16.3.330.

Diamantopoulou, S., Rydell, A., & Henricsson, L. (2008). Can both low and high self-esteem be related to aggression in children? Social Development, 17, 682–698. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00444.x.

Diener, M. B., & Milich, R. (1997). Effects of positive feedback on the social interactions of boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A test of the self-protective hypothesis. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 26, 256–265. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp2603_4.

Edens, J. F., Cavell, T. A., & Hughes, J. N. (1999). The self-systems of aggressive children: A cluster-analytic investigation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40, 441–453. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00461.

Eiraldi, R. B., Power, T. J., & Nezu, C. M. (1997). Patterns of comorbidity associated with subtypes of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder among 6- to 12-year-old children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 503–514. doi:10.1097/00004583-199704000-00013.

Emeh, C. C., & Mikami, A. Y. (2012). The influence of parent behaviors on positive illusory bias in children with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders,. doi:10.1177/1087054712441831.

Evangelista, N. M., Owens, J. S., Golden, C. M., & Pelham, W. E, Jr. (2008). The positive illusory bias: Do inflated self-perceptions in children with ADHD generalize to perceptions of others? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 779–791. doi:10.1007/s10802-007-9210-8.

Faraone, S. V., Biederman, J., Weber, W., & Russell, R. L. (1998). Psychiatric, neuropsychological, and psychosocial features of DSM-IV subtypes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Results from a clinically referred sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 37, 185–193. doi:10.1097/00004583-199802000-00011.

Gladstone, T. R. G., & Kaslow, N. J. (1995). Depression and attributions in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 23, 597–606. doi:10.1007/BF01447664.

Hankin, B. L., Abramson, L. Y., Moffitt, T. E., Silva, P. A., McGee, R., & Angell, K. E. (1998). Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107, 128–140. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.107.1.128.

Hart, T., Whyte, J., Junghoon, K., & Vaccaro, M. (2005). Executive function and self-awareness of “real-world” behavior and attention deficits following traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 20, 333–347. Retrieved from http://journals.lww.com/headtraumarehab.

Hinshaw, S. P. (1987). On the distinction between attentional deficits/hyperactivity and conduct problems/aggression in child psychopathology. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 443–463. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.101.3.443.

Hinshaw, S. P., & Melnick, S. M. (1995). Peer relationships in boys with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder with and without comorbid aggression. Development and Psychopathology, 7, 627–647. doi:10.1017/S0954579400006751.

Hoffman, K. B., Cole, D. A., Martin, J. M., Tram, J., & Seroczynski, A. D. (2000). Are the discrepancies between self- and others’ appraisals of competence predictive or reflective of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: A longitudinal study, part II. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 651–662. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.109.4.651.

Horn, W. F., Wagner, A. E., & Ialongo, N. (1989). Sex differences in school-aged children with pervasive attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 17, 109–125. doi:10.1007/BF00910773.

Hoza, B., Gerdes, A. C., Hinshaw, S. P., Arnold, L. E., Pelham, W. E, Jr, Molina, B. S. G., et al. (2004). Self-perceptions of competence in children with ADHD and comparison children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 382–391. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.382.

Hoza, B., McQuade, J. D., Murray-Close, D., Shoulberg, E., Molina, B., Arnold, L. E., et al. (2013). Does childhood positive self-perceptual bias mediate adolescent risky behavior in youth from the MTA study? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology,. doi:10.1037/a0033536.

Hoza, B., Murray-Close, D., Arnold, L. E., Hinshaw, S. P., Hechtman, L., & The MTA Cooperative Group. (2010). Time-dependent changes in positively biased self-perceptions of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A developmental psychopathology perspective. Development and Psychopathology, 22, 375–390. doi:10.1017/S095457941000012X.

Hoza, B., Pelham, W. E., Dobbs, J., Pillow, D. R., & Owens, J. S. (2002). Do boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder have positive illusory self-concepts? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111, 268–278. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.111.2.268.

Hoza, B., Pelham, W. E., Milich, R., Pillow, D., & McBride, K. (1993). The self-perceptions and attributions of attention deficit hyperactivity disordered and nonreferred boys. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 21, 271–286. doi:10.1007/BF00917535.

Hoza, B., Pelham, W. E., Waschbusch, D. A., Kipp, H., & Owens, J. S. (2001). Academic task persistence of normally achieving ADHD and control boys: Performance, self-evaluations, and attributions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 271–283. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.69.2.271.

Hoza, B., Vaughn, A., Waschbusch, D. A., Murray-Close, D., & McCabe, G. (2012). Can children with ADHD be motivated to reduce bias in self-reports of competence? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80, 245–254. doi:10.1037/a0027299.

Hoza, B., Waschbusch, D. A., Pelham, W. E., Molina, B. S. G., & Milich, R. (2000). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disordered and control boys’ responses to social success and failure. Child Development, 71, 432–446. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00155.

Hughes, J. N., Cavell, T. A., & Grossman, P. B. (1997). A positive view of self: Risk or protection for aggressive children? Development and Psychopathology, 9, 75–94. doi:10.1017/S0954579497001077.

Hughes, J. N., Cavell, T. A., & Prasad-Gaur, A. (2001). A positive view of peer acceptance in aggressive youth: Risk for future peer acceptance. Journal of School Psychology, 39, 239–252. doi:10.1016/S0022-4405(01)00067-X.

Hymel, S., Bowker, A., & Woody, E. (1993). Aggressive versus withdrawn unpopular children: Variations in peer and self-perceptions in multiple domains. Child Development, 64, 879–896. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02949.x.

Ialongo, N. S., Lopez, M., Horn, W. F., Pascoe, J. M., & Greenberg, G. (1994). Effects of psychostimulant medication on self-perceptions of competence, control, and mood in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 23, 161–173. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp2302_6.

Jiang, Y., & Johnston, C. (2012). The relationship between ADHD symptoms and competence as reported by both self and others. Journal of Attention Disorders, 16, 418–426. doi:10.1177/1087054710392541.

Kendall, P. C., Stark, K. D., & Adam, T. (1990). Cognitive deficit or cognitive distortion in childhood depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 18, 255–270. doi:10.1007/BF00916564.

Kessler, R. C., McGonagle, K. A., Swartz, M., Blazer, D. G., & Nelson, C. B. (1993). Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey I: Lifetime prevalence, chronicity and recurrence. Journal of Affective Disorders, 29, 85–96. doi:10.1016/0165-0327(93)90026-G.

Kistner, J. A., David-Ferdon, C. F., Repper, K. K., & Joiner, T. E, Jr. (2006). Bias and accuracy of children’s perceptions of peer acceptance: Prospective associations with depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34, 349–361. doi:10.1007/s10802-006-9028-9.

Klingberg, T., Forssberg, H., & Westerberg, H. (2002). Training of working memory in children with ADHD. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 24, 781–791. doi:10.1076/jcen.24.6.781.8395.

Knouse, L. E., Bagwell, C. L., Barkley, R. A., & Murphy, K. R. (2005). Accuracy of self-evaluation in adults with ADHD: Evidence from a driving study. Journal of Attention Disorders, 8, 221–234. doi:10.1177/1087054705280159.

Knouse, L. E., Paradise, M. J., & Dunlosky, J. (2006). Does ADHD in adults affect the relative accuracy of metamemory judgments? Journal of Attention Disorders, 10, 160–170. doi:10.1177/1087054706288116.

Lahey, B. B., Schwab-Stone, M., Goodman, S. H., Waldman, I. D., Canino, G., Rathouz, P. J., et al. (2000). Age and gender differences in oppositional behavior and conduct problems: A cross-sectional household study of middle childhood and adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 488–503. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.488.

Laird, R. D., & De Los Reyes, A. (2013). Testing information discrepancies as predictors of early adolescent psychopathology: Why difference scores cannot tell you what you want to know and how polynomial regression may. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41, 1–14. doi:10.1007/s10802-012-9659-y10.1007/s10802-012-9659-y.

Laird, R. D., & Weems, C. F. (2011). The equivalence of regression models using difference scores and models using separate scores for each informant: Implications for the study of informant discrepancies. Psychological Assessment, 23, 388–397. doi:10.1037/a0021926.

Linnea, K., Hoza, B., Tomb, M., & Kaiser, N. (2012). Does a positive bias relate to social behavior in children with ADHD? Behavior Therapy, 43, 862–875. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2012.05.004.

McGrath, E. P., & Repetti, R. L. (2002). A longitudinal study of children’s depressive symptoms, self-perceptions, and cognitive distortions about the self. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111, 77–87. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.111.1.77.

McQuade, J. D., Hoza, B., Waschbusch, D. A., Murray-Close, D., & Owens, J. S. (2011a). Changes in self-perceptions in children with ADHD: A longitudinal study of depressive symptoms and attributional style. Behavior Therapy, 42, 170–182. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2010.05.003.

McQuade, J. D., Tomb, M., Hoza, B., Waschbusch, D. A., Hurt, E. A., & Vaughn, A. J. (2011b). Cognitive deficits and positively biased self-perceptions in children with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 307–319. doi:10.1007/s10802-010-9453-7.

Mikami, A. Y., Calhoun, C. D., & Abikoff, H. B. (2010). Positive illusory bias and response to behavioral treatment among children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39, 373–385. doi:10.1080/15374411003691735.

Milich, R., & Okazaki, M. (1991). An examination of learned helplessness among attention-deficit disordered boys. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 19, 607–623. doi:10.1007/BF00925823.

Miller, G. A., & Chapman, J. P. (2001). Misunderstanding analysis of covariance. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110, 40–48. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.110.1.40.

Murray-Close, D., Hoza, B., Hinshaw, S. P., Arnold, E., Swanson, J., Jensen, P. S., et al. (2010). Developmental processes in peer problems of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the multimodal treatment study of children with ADHD: Developmental cascades and vicious cycles. Development and Psychopathology, 22, 765–802. doi:10.1017/S0954579410000465.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2001). Gender differences in depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 173–176. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00142.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Girgus, J. S. (1994). The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 424–443. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.115.3.424.

O’Neill, M. E., & Douglas, V. L. (1991). Study strategies and story recall in attention deficit disorder and reading disability. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 19, 671–692. doi:10.1007/BF00918906.

Ohan, J. L., & Johnston, C. (2002). Are the performance overestimates given by boys with ADHD self-protective? Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 31, 230–241. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3102_08.

Ohan, J. L., & Johnston, C. (2011). Positive illusions of social competence in girls with and without ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 527–539. doi:10.1007/s10802-010-9484-0.

Oosterlaan, J., Scheres, A., & Sergeant, J. A. (2005). Which executive functioning deficits are associated with AD/HD, ODD/CD and comorbid AD/HD + ODD/CD? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33, 69–85. doi:10.1007/s10802-005-0935-y.

Orobio de Castro, B., Brendgen, M., van Boxtel, H., Vitaro, F., & Schaepers, L. (2007). “Accept me, or else…”: Disputed overestimation of social competence predicts increases in proactive aggression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35, 165–178. doi:10.1007/s10802-006-9063-6.