Abstract

This article reviews the literature on how culture influences anxiety in Latino youth. First, a review of cross-cultural variations in prevalence and measurement is presented. Then, the article focuses on how culture impacts the meaning and expression of anxiety. Specifically, we discuss the meaning and expression of anxiety, the impact of culture on anxiety at a societal level and through its effect on family and cognitive processes, and the influence of immigration and acculturation on anxiety. Finally, we propose recommendations on how to advance the literature in this area building on existing knowledge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Anxiety disorders are among the most prevalent psychiatric disorders affecting children and adolescents (Berstein and Borchardt 1991; Kashani and Orvaschel 1990; Weiss and Last 2001). Anxiety disorders have a chronic course (Keller et al. 1992; Last et al. 1996) and negatively affect children’s functioning in a variety of domains (Last et al. 1997). In light of the chronic and pernicious aspects of anxiety disorders, research in this area has burgeoned in the last two decades yielding important findings that have informed theories of their development, maintenance, and treatment. Overall, these theories emphasize the transactional nature of constitutional (e.g., genetics, temperament, cognitive biases) and psychosocial (e.g., attachment, parent–child interactions, life experiences) elements associated with anxiety (Barlow 2002; Chorpita and Barlow 1998; Craske 1999; Pollock et al. 1995; Manassis and Bradley 1994; Vasey and Dadds 2001). Culture is believed to impact any of these dimensions and the manner in which they interact to produce risk for or protection from the emergence and maintenance of anxiety problems (Harre and Parrot 1996; Kirmayer 2001; Kirmayer et al. 1995). To date, however, the cultural angle of childhood anxiety has not been well integrated into this growing literature.

The definition of culture has been discussed at great length in the literature (for a thorough discussion of culture definitions see Eagleton 2000). In this article, we take on the definition that culture is “Shared learned behavior which is transmitted from one generation to another for purposes of individual and societal growth, adjustment, and adaptation; culture is represented externally as artifacts, roles and institutions, and it is represented internally as values, beliefs, attitudes, epistemology, consciousness, and biological functioning” (Marsella 1988, pp. 8–9). Individuals therefore can be clustered into cultural groupings based on a number of shared constructs and experiences including schemas (e.g., a collectivistic orientation), beliefs (e.g., attitudes toward mental health), socialization practices (e.g., controlling parenting), immigration, and language among others.

Some aspects of emotion are considered human universals including primary fear and stress physiological responses (e.g., fight or flight) or event types that elicit certain emotion outputs. For example, anticipation of physical danger seems to be linked to fear and anxiety across cultures (Mesquita and Frijda 1992). Beyond certain universals, however, there are several sources of cultural variation in emotion practices. Mesquita and colleagues propose that cultural models can influence various aspects of emotion practices including antecedent events, subjective feelings, appraisal, and behavior expression (Mesquita and Frijda 1992; Mesquita and Walker 2003). Cultural models refer to beliefs, values, and social practices that support and allow for what is moral, imperative, and desirable (Mesquita and Walker 2003).

In this article, we examine how cultural models influence anxiety symptomatology and expression in Latino youth. Cultural variations in values and beliefs are likely to occasion events that may place an individual at risk for or protect from anxiety problems. For example, a number of studies have found an association between cultures considered collectivistic and internalizing problems including anxiety (Weisz et al. 1987, 1993a, b; Ollendick et al. 1996). There is also some evidence that a strong family orientation may be a protective factor against mental health problems (Escobar et al. 2000). Culture-based ideologies and beliefs about parenting and parent–child interactions also serve to shape the organization and expression of affect including anxiety. For instance, whereas authoritarian parenting characterized by strict discipline and not granting autonomy is linked to clinical anxiety in western cultures, it is not associated with clinical anxiety in non-western cultures (Wood et al. 2003; Oh et al. 2002). In such case, cultural prescriptions about normative and non-normative socialization strategies are likely to influence children’s perceptions of controlling or authoritarian parenting. Cultural differences in perceptions and approaches to illness also have an impact in the experience of disease, interpretation of symptoms, symptom expression, and the manner in which one copes (Salman et al. 1997).

Examination of how cultural models impact anxiety in Latino youth is important for a number of reasons. There is plenty of evidence indicating that models of developmental psychopathology derived with white European American populations are not necessarily applicable to other cultural groups (Deater-Deckard and Dodge 1997; Ispa et al. 2004; Lindahl and Malik 1999; Luis et al. 2008). Beyond developing explicatory models of psychopathology with Latino youth, our understanding of how relevant cultural and contextual variables may serve to protect or place such children at greater risk will facilitate the development of psychosocial and cognitive interventions and preventive measures for anxiety disorders with this population. In addition, Latinos are the most numerous and fastest growing ethnic minority group in the United States, and approximately 15.4 million are under the age of 18 years (U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census 2009). Gaining an understanding of how such cultural phenomena influence the various aspects of anxiety in this large and growing population becomes even more imperative especially when one considers that a growing literature shows Latino youth are at higher risk for developing anxiety symptoms and disorders (La Greca et al. 1996; Shannon et al. 1994; Wasserstein and LaGreca 1998; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2001; Varela et al. 2004, 2008) than the corresponding risk for European American youth.

In this article, we use the term Latino to refer to individuals living in the United States whose origin is any country in Latin America including the Caribbean where Spanish is the predominant language. Although there is much heterogeneity within the Latino population, Latinos from different countries of origin share a number of experiences, values, perspectives, and socialization approaches that distinguish them as a cultural group, and we focus on this population in this review (see Marin and Marin 1991 for a thorough discussion on this topic). We indicate the country of origin whenever possible and when we refer to individuals who are still living in Latin America, we refer to those individuals by the country in which they live (e.g., Puerto Rican or Mexican). However, irrespective of whether the Latino individuals live in the United States or in Latin America, we treat them as one cultural group based on the knowledge that they share a number of values, beliefs, and socialization practices (Marin and Marin 1991). The term Hispanic refers to Latinos and other individuals whose language is Spanish including those whose country of origin is Spain (Marin and Marin 1991). Although the term Hispanic is used widely in the anxiety literature, the vast majority of studies only include populations whose country of origin is in Latin America. The term Latino then is a more accurate description of the populations being studied and reviewed here.

First, we summarize what is known about cultural variations in the prevalence of anxiety symptoms and disorders in Latino youth and their assessment. Then, we consider the influence of Latino culture on anxiety in youth. Specifically, we discuss the meaning and expression of anxiety, the impact of culture on anxiety at a societal level and through its effect on family and cognitive processes, and the influence of immigration and acculturation on anxiety. Finally, we propose recommendations on how to advance the literature in this area building on existing knowledge.

For our review, we identified articles by searching the research literature using PsycINFO with the following keywords: anxiety, anxiety disorder (and each anxiety disorder, e.g., GAD), mood, mental health, Latino, Latin American, Hispanic, Mexican, Mexican American, Puerto-Rican, Cuban, Cuban-American, Central American, South American, children, youth, adolescents, assessment, prevalence, collectivism, somatic symptoms, nervios, ataque de nervios, simpatia, cultural psychiatry, cross-cultural, culture, immigration, and acculturation. We also searched the reference lists of identified articles to find additional articles.

Prevalence and Cross-cultural Measurement

Prevalence

In one of the few studies examining differences in mental health diagnoses among Latino youth and youth from different ethnic groups, Ginsburg and Silverman (1996) found that Latino children (ages 6–17 years; primarily of Central American origin) were more likely to meet criteria for separation anxiety disorder, based on parent and child report versions of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children (ADIS-C and ADIS-P; Silverman and Nelles 1988), than their Caucasian counterparts (N = 242). Notably, no differences were found regarding the prevalence of other anxiety disorder diagnoses (e.g., phobic disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder). When anxiety disorders are considered broadly, children in Latin American countries do not seem to differ from children in the United States. A community survey of children and adolescents aged 4–17 years in Puerto Rico found that the prevalence rate of anxiety disorders assessed by the Spanish version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV; Bravo et al. 2001) in the previous year was 6.9% (N = 1,897; Canino et al. 2004), similar to findings of studies conducted in the United States. For example, Costello and colleagues (1996) found a 5.69% three-month prevalence rate of anxiety disorders among 9-, 11-, and 13-year-old participants (N = 4,500; 91.9% Caucasian) using the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA; Angold et al. 1995), and Angold and colleagues (2002) found a 6.7% three-month prevalence rate of anxiety disorders among 9–17-year-old Caucasian youth (n = 379) living in North Carolina utilizing the CAPA.

In addition to the evidence that Latino children and adolescents may be more at risk for certain anxiety disorders (i.e., separation anxiety) than Caucasian children, other researchers have found that symptoms of anxiety are elevated in Latino youth compared to American youth from other ethnic groups. Even during early childhood (from 2 to 4 years of age), Latino children are more likely to exhibit clinical levels of internalizing symptoms based on parent reports on the Child Behavior Checklist/1½–5 (Achenbach and Rescorla 2000) than Caucasian or African American children of the same age (N = 682; Gross et al. 2006). This pattern appears to continue through later childhood and adolescence. For example, Glover et al. (1999) administered the Youth Self Report (YSR; Achenbach and Edelbrock 1987) to 2,528 participants (from 7th to 12th grade) from two regions in Texas. They found that the Latino adolescents (predominantly Mexican American) reported more anxiety symptoms than white non-Latino adolescents. In another study, McLaughlin et al. (2007) administered the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; March et al. 1997) and the Penn State Worry Questionnaire for Children (Chorpita et al. 1997) to an ethnically diverse sample among 6th–8th graders (N = 1,065). Consistent with trends noted in previous research, these researchers found that Latino adolescents (from Central and South American backgrounds) reported higher levels of worry than Caucasian participants and more symptoms of separation anxiety than Caucasian and African American participants. Furthermore, Latino females reported the highest level of social anxiety symptoms among all participants and the most physical symptoms of anxiety among all the female participants.

The finding that Latino children worry more than children of other ethnicities is perhaps the most corroborated. For example, Ginsburg and Silverman (1996) found that Latino parents reported their children worried more than did Caucasian parents, specifically reporting higher elevations in their children’s fear of the unknown and fears of danger and death, measured by the Fear Survey Schedule for Children—Revised (FSSC-R; Ollendick 1983). Also, Silverman et al. (1995) found that Latino children from 2nd to 6th grades reported more health-related worries than their Caucasian peers in semi-structured interviews developed and conducted by the researchers (N = 273; ages 7–12).

Research extending beyond the mainland United States also supports the notion that, in general, Latino youth report more worries than Caucasian youth. Varela et al. (2004) administered the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS; Reynolds and Richmond 1978) to 10–14-year-old children in Mexico and Mexican American and European American youth living in the United States (N = 154). Mexican and Mexican American children self-reported more general worry symptoms than European American children. In a later study, Varela et al. (2008) administered the RCMAS, MASC, and FSSC-R to 7–16-year-old youth in Mexico, and Latino (Mexican and Central American descent), and European American youth and their parents (N = 217). The results were similar to those of their previous study. Mexican and Latino youth reported more worries than the European American youth and mothers' reports corroborated these differences. Similar to the Ginsburg and Silverman (1996) findings, mothers of the Mexican and Latino youth reported more fears of the unknown, and fears of danger and death for their children than European American mothers reported for their children. In a comparison study among 4–16-year-old Puerto Rican children living in Puerto Rico and children living in mainland United States (approximately 80% white) matched with the Puerto Rican sample for age, sex, and SES (N = 1,448), Puerto Rican children scored higher than mainland children according to at least two informants on 14 internalizing items common to Child Behavior Checklist/4-16 (CBCL; Achenbach and Edelbrock 1983), Teacher Report Form (TRF; Achenbach and Edelbrock 1986), and YSR. Four of these items load directly on the Anxiety Problems scale (“nervous, high strung, or tense,” “clings to adults or too dependent,” “too fearful or anxious,” and “worries”). Mainland children did not score higher than Puerto Rican children on any of internalizing items (Achenbach et al. 1990).

Age and gender seem to have an effect on reported anxiety symptoms among Latino youth, with evidence that younger children report more fears on the FSSC-R than older children (Ginsburg and Silverman 1996) and that girls report more worries during clinical interviews than boys (Silverman et al. 1995). These trends are in the same direction as those observed by Weems and Costa (2005) with a multi-ethnic sample of youth (N = 145; ages 6–17) utilizing the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS; Chorpita et al. 2000) and the FSSC-R. Other data (Varela et al. 2007; N = 351; grades 9–12) suggests that there are no interaction effects between gender and ethnicity in the prediction of anxiety symptoms as measured by the Brief Symptom Inventory—18 (BSI-18; Derogatis 2000).

Assessment

By and large assessment of anxiety in Latino populations has been mostly conducted using the same instruments used to gauge anxiety in the majority white non-Latino population. On the one hand, this approach is useful in that it allows for direct comparisons of symptom expression across groups. On the other hand, the danger of making fallacious conclusions exists due to non-equivalence in measurement. Measurement equivalence refers to the accurate assessment of a construct across different populations with the same instrument or measurement method (Knight and Hill 1998; van de Vijver and Leung 1997). Equivalence cannot be assumed even when the construct in question appears applicable to all groups under study. Among other potential confounders (e.g., measurement error), cultural bias could systematically influence the psychometric properties of a scale and lead to measurement nonequivalence (Knight and Hill 1998; van de Vijver and Leung 1997).

A variety of analytic strategies proposed to provide evidence of measurement equivalence exist in the literature. Item-total related strategies such as item response theory and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) gauge the relationship between a specific item and the total scale score to determine the accuracy with which specific items measure the same construct between two populations (item equivalence: Hui and Triandis 1985; Knight and Hill 1998). Comparing the correlations of the construct in question with other theoretically relevant constructs across groups and testing whether such relations are equivalent help determine if the construct functions in the same manner across the groups or if there is functional equivalence in measurement. According to Hui and Triandis, functional equivalence is established when the scores representing an underlying construct have similar antecedents, consequences, and correlates.

Employing these analytic strategies, Varela and Biggs (2006) reanalyzed data from the Varela et al. (2004) study described above and found that the RCMAS shows factorial invariance across groups of Mexican, Mexican American, and European American youth. Similarly, Varela et al. (2008) found evidence that the RCMAS, MASC, and FSSC-R are cross culturally valid with Mexican, Latino (Mexican and Central American descent), and European American children. The measures demonstrated factorial invariance (item equivalence) and they related to each other in the same manner across groups (functional equivalence). Pina et al. (2009) found further support for the factorial invariance and functional equivalence of the RCMAS across a sample of Latino and white non-Latino youth referred for treatment to an anxiety disorders clinic (N = 677). Approximately 49% of the Latino sample in that study was of Cuban descent and the rest were of other Latino backgrounds (e.g., Mexican, Caribbean, Central American, and South American). The cross-cultural equivalence of these measures not only allows for comparisons across groups in the dimensions being measured but informs the multidimensionality of anxiety in Latino populations. That is, anxiety as a construct in Latino culture seems to comprise physiological, cognitive, social, and behavioral aspects.

Analytic strategies other than CFA and item response theory have been used to examine the validity of anxiety measures with Latino youth. For example, principal component factor analyses show that the factor structure of the RCMAS with youth in Uruguay is similar to the factor structure of the scales with youth in the United States (N = 1,423; Richmond et al. 1988). Although this study did not use structural equation modeling procedures, the results provide further evidence that the scales tap similar constructs in Latin American countries as in the United States. Similarly, the Spanish version of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAI-C; Spielberger 1973) has been shown to have good internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and construct and concurrent validity with Latino youth in Puerto Rico and Panama (Bauermeister et al. 1986). Some evidence also exists for the validity of two broad band measures of children’s behaviors with Latino populations. The CBCL, parent and teacher report (Achenbach and Edelbrock 1983) has been shown to exhibit good internal consistency and good construct validity with higher scores being associated with more maladjustment in Puerto Rican children (N = 273; Rubio-Stipec et al. 1990). Similarly, there is some evidence, although with a limited sample (N = 55), that the Behavior Assessment for Children (Reynolds and Kamphaus 2002) may be a valid measure to use with Latino youth (McCloskey et al. 2003). In that study, however, some of the subscales, including the withdrawal scale, had inadequate internal consistencies.

In terms of clinical interviews that assess anxiety, the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (Reich 2000) has been shown to have good reliability and validity with Puerto Rican youth (N = 777; Gould et al. 1993). The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children for DSMIV (Silverman and Albano 1996) has also been shown to have good reliability and validity with samples that include Latino youth in the United States (N = 62; Silverman et al. 2001).

Children’s Anxiety in a Latino Cultural Context

The meaning of anxiety has been discussed comprehensively in the literature including its distinction from related constructs fear and panic (e.g., Barlow 2002; Barlow et al. 1996; Craske 1999; Izard and Blumberg 1985; Gray 1991; Lang 1985). Recent conceptualizations designate fear (and panic) as a transitory response to imminent threat, real or imagined, with salient physiological arousal and behavioral indices (e.g., fight/flight); whereas anxiety, although sharing similar physiological and behavioral indices, can be thought of as a response to danger or threat in the future, thereby having a more salient cognitive component (Barlow et al. 1996; Craske 1999). Most definitions of anxiety then include some physiological component, autonomic arousal and endocrine system involvement specifically, a cognitive component including biases in information processing elements (e.g., attention, interpretation, response selection), and behavioral indices (e.g., avoidance) (for thorough discussions see Barlow 2002; Craske 1999). Other dimensions of anxiety may also include the propensity for anxious responding (e.g., trait form) and actualizations of anxious outputs that may vary by situation (state form) (Cattell and Scheier 1961; Spielberger 1972).

There is no reason to believe that the overall dimensions associated with anxiety as described above do not apply to Latino youth populations. A number of studies that include Latino youth in their samples or focus on youth living in Latin America provide some evidence that anxiety as a construct is conceptualized as including physiological, cognitive, and behavioral dimensions and in state/trait form in Latino culture (de Minzi and Sacchi 1999; Joiner et al. 1996; Kort et al. 1998; Moreno et al. 1995; Phillips et al. 2002; Stoyva 1984). Also supporting the contention that anxiety as a construct involves these basic components is the cross-cultural validity of measures discussed above that tap into anxiety. That is, because the factor structure of widely used anxiety measures is equivalent across Latino and white non-Latino cultures, one can assume that at a minimum the same aspects of anxiety as measured by these factors (e.g., physiological, worry, social subscales of the RCMAS) exist in both cultures and are used to define the construct of anxiety.

Thus, anxiety in Latino youth involves physiological, cognitive, and behavioral dimensions in some fashion and can be conceptualized in trait or state forms. However, cultural models impact the manner in which such components look and interact with each other and with other emotion relevant variables, how symptoms are experienced and which ones are emphasized in expression, and the meaning attributed to such symptoms (Kirmayer et al. 1995; Mesquita and Walker 2003).

Cultural Influences in Meaning and Expression

In Latino culture social stigma and family shame implications associated with mental disorders appear to color descriptions and interpretations of psychological symptoms including anxiety (Salman et al. 1997). Mental illness carries a heavy stigma for both the individual and the family. For instance, Magaña et al. (2007) found that Latino caretakers of an adult within the family diagnosed with schizophrenia reported their level of distress to be associated with how negatively they thought others perceived them for having a mentally ill family member. Others have also found more negative attitudes toward mentally ill individuals in Latino populations relative to white non-Latinos. These findings include that mentally ill individuals are inferior and should be isolated from others (Silva de Crane and Spielberger 1981) and that mentally ill individuals are more dangerous than non-mentally ill individuals (Whaley 1997). In contrast to these findings, Alvidrez (1999) found that Latino women were less likely to endorse beliefs that mental illness carries a stigma than African American and white non-Latino women. However, Alvidrez explains that this result may have been confounded by the lack of variability in the responses across the three groups. Mental illness in Latino culture may carry a stigma because it is believed to reflect a weakness of character, lack of will power, or just being intentionally unreasonable (Keefe 1981; Padilla and Salgado de Snyder 1988; Urdaneta et al. 1995).

Nervios

Considering the negative connotations of mental illness in the Latino culture, some have proposed that Latinos prefer to use more benign culturally accepted terms when referring to symptoms that may be construed as indicative of mental illness (Jenkins 1988a, b; Milstein et al. 1995; Salman et al. 1997). One culture syntonic idiom of distress that is widely used by Latinos, particularly of Caribbean, Mexican, and Central American origins is the term nervios. Nervios (literal translation is nerves) is used to describe a wide range of negative emotional conditions including anxiety, troubling states, and somatic distress (Baer et al. 2003; Guarnaccia et al. 1989, 1992, 1993; Guarnaccia and Farias 1988; Jenkins 1988a; Salgado de Snyder et al. 2000). There is some evidence that the term nervios may be used to avoid stigma associated with formal psychiatric terms. For example, families from Latino cultures may describe the symptoms of schizophrenia as a form of nervios to avoid the negative social stigma associated with mental illness (Jenkins 1988a, b). Similarly, Salman et al. (1997) indicate that some of the patients seen at the Hispanic Treatment Program at the New York State Psychiatric Institute prefer the use of the term nervios to avoid the psychiatric label of panic attacks. Similar uses of the term have been found in investigations of affective and anxiety symptoms among adult women in rural Mexican communities (Salgado de Snyder et al. 2000).

Although the literature on nervios as a form of emotional expression is rich and increasingly expanding, it has mostly focused on adult populations with minimal attention to children’s idioms of expression. One study conducted by Arcia et al. (2004) focused on Latino mothers’ use of the term nervios in describing their children’s disruptive behaviors and mental health issues in the family. Arcia et al. interviewed 62 mothers of Cuban, Dominican, or Puerto Rican background whose children exhibited disruptive behaviors including symptoms of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, and Conduct Disorder. The authors found that a large number of mothers used the terms nervios and anxiety to describe their children’s disruptive behaviors and the term nervios to describe a wide range of mental health issues in adults. Interestingly, the concept of nervios when applied to children was reflective of a temperament trait suggesting vulnerability to future mental health problems but not indicative of actual mental health illness or related dysfunction, uses of the term reserved for adults. These findings are consistent with the adult literature that indicates nervios is linked to anxiety but is used to describe a wider range of symptoms. The study also highlights the need to examine cultural idioms of distress in children as these are likely to mean different things and have different uses than with adults.

A closely related term used in Latino culture to express emotional distress and imbalances in one’s life is ataque de nervios, a cultural syndrome recognized in the DSM-IV. Whereas nervios is construed to reflect chronic and low-grade distress and can also be used to describe reactive symptoms to external stressors, ataque de nervios is a more acute condition generally used to describe a loss of emotional control following severe stress-inducing events such as funerals and car accidents (Guarnaccia et al. 1989b; Liebowitz et al. 1994; Salman et al. 1998). Relative to nervios, ataques de nervios are usually stress induced and may not be remembered by the individual experiencing them (Guarnaccia et al. 1989a). Particular symptoms of ataques may include feeling out of control, shaking, palpitations, difficulty breathing, numbness, shouting, swearing, striking at others, and falling to the ground and experiencing convulsions (Guarnaccia et al. 1989a, 1996). Epidemiologically, acknowledgement of having had ataques de nervios increases the likelihood of meeting criteria for affective or anxiety disorders, and Latin Americans may employ the term ataque de nervios to identify panic attacks (Lewis-Fernandez et al. 2002; Salman et al. 1997). Although ataques de nervios share several symptoms with panic episodes, Guarnaccia and Lewis-Fernandez and colleagues have provided ample evidence that ataques de nervios are phenomenologically distinct from panic attacks and panic disorder (Lewis-Fernandez et al. 2002; Guarnaccia et al. 1993; Liebowitz et al. 1994; Salman et al. 1998). Unlike panic attacks and panic disorder, ataques do not tend to crescendo in less than 10 minutes, individuals experiencing an ataque tend to report feeling better and relieved after the ataque, and ataques appear to be provoked by some life circumstance.

Similar to the literature with nervios, the literature on ataques de nervios is primarily focused on the adult population with little emphasis on children’s use of this idiom of expression. Two recent studies, however, have begun to examine this cultural syndrome in Latino youth. Guarnaccia et al. (2005) assessed a large probability sample of community (n = 1,886) and clinic referred (n = 751) 4–17-year-old children and adolescents in Puerto Rico for the presence of ataques de nervios and other disorders. Nine percent of the community sample and 26% of the clinical sample were reported to have experienced an ataque de nervios. Girls 11 years or older were more than three times as likely to have an ataque than boys or younger girls and perceived poverty was associated with greater likelihood of experiencing an ataque. Overall, the presence of ataques was highly related to meeting criteria for any psychiatric disorder and this association was strongest for Dysthymia and Panic Disorder in the community sample and PTSD and major depression in the clinical sample. In a second study using probability community samples of 5–13-year-old children from Puerto Rico (n = 2,951) and the South Bronx, New York (n = 1,138), Lopez et al. (in press) found no significant differences across these the two samples in rates of ataques, causes for the ataques, and functional impairment associated with the ataques. Four to five percent of all children were identified as having had an ataque, and most of the children indicated that their ataques were caused by stress and were more impaired than children not identified as having had an ataque. Like with the Guarnaccia et al. (2005) study, ataques were associated with most forms of psychopathology including anxiety and disruptive disorders.

The studies by Arcia et al. (2004), Guarnaccia et al. (2005), and Lopez et al. (in press) present important contributions to our understanding of Latino children’s forms of emotion expression including anxiety. This literature indicates that the idioms nervios and ataque de nervios in children are used widely to convey negative affective and anxious states. However, these terms can also be used to reflect a broad range of emotional and behavioral conditions and their specificity to anxiety emotion is unclear based on the small number of studies in this area.

From a cultural perspective, the terms nervios and ataque de nervios may reflect subtle preferences by Latinos to describe troubling cognitive and somatic experiences that resemble specific mental disorders in broader, more benign and culturally accepted terms.

Somatic Symptoms

Some have proposed that somatic symptoms, like nervios, may also be a culturally sanctioned manner of expressing emotional or social distress that may only make sense in the individual’s cultural context (Kirmayer and Young 1998). The notion that somatic symptoms can be a manner of expression for emotional distress has been present in the literature for decades (Kirmayer 1984; Kleinman 1977; Lipowski 1988). However, it is not until recently that somatic symptoms as a form of expression has been investigated in Latino youth.

Varela et al. (2004) administered the RCMAS to 10–14-year-old Mexican children (n = 53) in Mexico, and to Mexican American (n = 50) and European American (n = 51) children in the United States. After controlling for socioeconomic status (SES) and scores on Lie scale of the RCMAS, the authors found that the Mexican and Mexican American children reported more physiological anxiety symptoms and more worry/sensitivity symptoms than the European American children. In a second study, Varela et al. (2008) administered the RCMAS and MASC to an independent sample of 7–16-year-old Mexican children in Mexico (n = 99), and Latino (n = 72; Mexican and Central American origin) and European American (n = 46) children in the United States and all the children’s parents. Consistent with their previous results, after controlling for SES differences, Mexican children reported more physiological anxiety symptoms using the RCMAS than the European American children. Using the MASC, Mexican children reported more physical symptoms than both the Latino and the European American children, although the scores of the Latino children landed in the middle of the other two scores. Using the MASC, the mothers of the Mexican children reported more physical symptoms of anxiety for their children than mothers of the Latino children, who in turn, reported more physical symptoms than the European American mothers did for their children. Of note is that in both of these studies the main differences in anxiety reporting across the three groups were evident only in the physiological or worry symptoms. That is, the groups did not differ in other types of anxiety symptoms including self- and parent-reported separation/panic or social anxiety symptoms.

A third study conducted by Varela et al. (2007) examined somatic, anxiety, and depression symptoms in Colombian youth in Colombia (n = 163), and Latino (n = 116) and white non-Latino (n = 72) youth in the United States. All the children were in the 9th–12th grade and were administered the BSI (Derogatis 2000). The authors found that white non-Latino males scored lower in somatic symptoms than white non-Latino females and all the Colombian and Latin American youth. Latino and Colombian females were higher in anxiety than the white non-Latino males. A fourth study conducted by Pina and Silverman (2004) examined somatic and anxiety symptoms in 5–17-year-old Latino (n = 91) and white non-Latino (n = 61) youth presenting to an anxiety disorders clinic. The Latino youth were further divided into a group of Cuban origin (n = 62) and a group of those whose origin was in other Latino countries (n = 29) (e.g., Nicaragua, Venezuela, Colombia, and Honduras). Using the physiological subscale of the RCMAS and the somatic subscale of the CBCL the authors found that non-Cuban Latino parents reported more somatic symptoms of anxiety for their children than European American and Cuban American parents reported for their children.

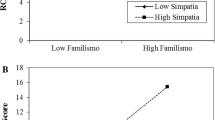

Although variability in cultural models is presumed to effect differences in somatic symptom expression across Latino and white non-Latino cultures, only one study has examined this hypothesis directly. With the backdrop that mental illness carries a heavy stigma in Latino culture, Varela et al. (2004) hypothesized that because Mexican descent children are socialized to shape their interpersonal interactions so as to have pleasant outcomes (i.e., simpatia; Gabrielidis et al. 1997; Triandis et al. 1984) and have a strong group orientation (i.e., collectivism; Markus and Kitayama 1991; Shkodriani and Gibbons 1995; Vega 1990), they may not want to bother family members with emotional difficulties that may signal mental problems so as not to disrupt family harmony. Thus, Latino children may turn to somatic symptoms as a manner of expressing their emotional discomforts. Children were administered measures of collectivism and simpatia and were asked to interpret ambiguous situations (e.g., “On the way to school you begin to feel funny in your stomach”). They were also asked to discuss these situations with their parents. Analyses of these discussions revealed that Mexican and Mexican American parents voiced a greater proportion of somatic interpretations for these situations than European American parents did, suggesting a cultural preference for somatic explanations of internal and social ambiguous stimuli. Somatic interpretations were not related to collectivism or simpatia. In addition, Mexican children voiced fewer somatic interpretations than Mexican American or European American children with the Mexican American children scoring between the other two groups.

The pattern of results from these studies is that Latinos in the United States and Latinos in their country of origin report more somatic symptoms than their European American counterparts in the United States. The finding by Pina and Silverman that Latinos of Cuban descent differed from Latinos of non-Cuban descent, however, highlights the importance of examining differences within Latino groups here in the United States. The Latinos of Central American descent and Mexican descent in the Varela et al. (2008) study did not differ in physiological or anxiety scores. In all, these results suggest that differences in somatic symptom reporting between Latino and white non-Latino youth are to a large degree culturally influenced. However, although cultural models have been proposed as causal factors in the cross-cultural variability of somatic symptom expression, there is little empirical investigation of specific cultural mechanisms potentially responsible for such variability (Varela et al. 2008).

Cultural Influences at Societal Level

A large body of literature indicates an association between collectivistic societies and the expression of more overcontrolled or internalizing symptoms relative to individualistic societies where undercontrolled or externalizing problems are more prevalent (Weisz et al. 1987, 1993a, b; Ollendick et al. 1996). Collectivism refers to the notion that individuals place their needs secondary to the needs of the collective group, and the behaviors, cognitions and emotions of individuals are experienced and enacted in reference to others (Hofstede 1984; Marin and Marin 1991; Triandis et al. 1985). This group orientation or “interdependent self-construal” implies a constant control and regulation of one’s own characteristics, emotions, and opinions so as to channel these to the task of interdependence (Markus and Kitayama 1991). Moreover, in a collectivistic society, the promulgation of interdependence and subordination to the group are further cultivated through strict social norms and expectations of conformity, self-restraint and social inhibition (Hofstede 1984).

One proposed explanation for the relationship between a collectivistic group orientation and anxiety is that behaviors and expressions that are consistent with cultural models of a society are likely to be propagated and have higher rates of occurrence than behaviors and expressions not consistent with cultural models of such society (Mesquita and Walker 2003). Symptom elevations in certain domains then are considered to reflect the societal emphasis on those particular types of mood states or behaviors (Draguns 1973; Ollendick et al. 1996; Weisz et al. 1987, 2006). From this perspective, individualistic cultures (e.g., the United States) which emphasize autonomous, outgoing, self-promoting behaviors are likely to have more youth with outward and noticeable, often disruptive, behavior problems because this type of expression is supported. In contrast, collectivistic societies that emphasize self-control, emotional restraint, compliance with social norms and social inhibition (e.g., Latino or Asian culture) are likely to have more youth that exhibit internalizing behaviors (e.g., shyness, anxiety, fear) because these types of behaviors are valued as a manner of emotion expression.

An alternative explanation for a relationship between the cultural model of collectivism and anxiety may deal with the effect that strict social norms and expectations for conformity have on the individuals in that culture. Individuals living in cultures where there are strict social norms and expectations for conformity are high may be more anxious because deviations from such rules and norms may carry severe consequences (Hofstede 1984). Supporting this notion, in a study with adults, Heinrichs et al. (2006) found that acceptance of attention-avoiding behaviors at a personal and perceived cultural level, consistent with a collectivistic model, was associated with more social anxiety and more fear of blushing.

To our knowledge only two studies have examined the direct effect of a collectivistic model on anxiety in Latino children (Varela et al. 2004; Varela et al. in press). The Varela et al. (2004) study was reviewed above and the Varela et al. (in press) study used the same sample as the Varela et al. (2008) study also reviewed above. Both studies used the Horizontal Collectivism (HC) subscale of the Individualism/Collectivism Scale (Singelis et al. 1995) to measure collectivism and the RCMAS to measure anxiety in Mexican, Latin American (Mexican and Central American descent), and European American children. Varela and colleagues hypothesized that an association between a collectivistic orientation and internalizing symptoms could be the product of an emphasis on self-regulation and control of emotions leading to a stifling of children’s understanding and managing of their internal states (Varela et al. 2004). That is, by not openly processing otherwise innocuous or transient feelings of depression or anxiety and somatic discomfort children may not learn to effectively deal with these conditions placing them at risk for anxiety problems (Suveg et al. 2005). In both studies, Varela and colleagues found that collectivism was higher among the Latino children than the European American children. However, one study found only a small positive correlation between collectivism and anxiety (Varela et al. 2004) and the other study found that collectivism was not predictive of anxiety using regression analyses (Varela et al. in press).

Thus, the literature shows strong evidence that internalizing symptoms including anxiety are more prevalent in youth from cultures characterized by a collectivistic ideal than in cultures where an individualistic orientation is the norm. However, how the cultural model emphasizing a collectivistic group orientation is directly linked to anxiety in youth is unclear. Some evidence supports the notion that a collectivistic model may influence anxiety by dictating negative consequences to deviating from the strict social norms and expectations associated with such culture (Heinrichs et al. 2006).

Cultural Influences on Family and Cognitive Processes

Beyond the influence of collectivistic models, culture can have a more visibly direct impact in emotion expression by influencing family interactions and cognitive processes. In the area of family processes, parenting that reflects over control of children, lacks in warmth and acceptance, and models maladaptive coping and catastrophizing have been consistently associated with clinical anxiety (Wood et al. 2003) but not in Latino populations. Luis et al. (2008) re-analyzed the family discussions of the Varela et al. (2004) study to gauge parental levels of control and warmth and acceptance in relation to the children’s anxiety reporting. They hypothesized that because controlling parenting in Latino culture is a valued socialization tool and may signal good and caring parenting it may not lead to negative appraisals for such parenting and ultimately anxiety in Latino children as it does for European American children. Luis et al. found support for this hypothesis in that controlling parenting was only positively associated with anxiety for the European American children, but negatively associated with anxiety for the Mexican American children; however, controlling parenting was also positively associated with anxiety for the Mexican children. The authors propose that a high number of direct commands or controlling parenting may serve an adaptive function for Mexican American children living in the United States. That is, this type of parenting may facilitate a unified response from ethnic minority families to ecological challenges (e.g., discrimination) by enhancing deference to authority and subordination of individual needs to the needs of the collective family. Contrary to their hypothesis, parental warmth and acceptance was positively associated with anxiety reporting for all children independent of cultural group. The authors interpreted this finding to indicate through warmth and acceptance parents may inadvertently reinforce children’s anxious responding.

One other study conducted by Varela et al. (in press) found similar results to these described above. In that study, Varela et al. examined child-reported parenting practices in relation to child and mother report of the children’s anxiety in Mexican, Latino (Mexican and Central American descent), and European American families. The authors found that father control was positively associated with anxiety for the European American children and negatively associated with anxiety in the Latino children. Mother control was positively associated with more anxiety independent of cultural group. Less father acceptance was related to higher anxiety symptoms independent of cultural group. Mother acceptance, however, was positively related with more anxiety for the European American and Latino groups but negatively associated with anxiety for the Mexican group. These results are largely consistent with the results of Luis et al. (2008) but also highlight the need to tease out the effects of parenting by parent gender.

In terms of cognitive processes, attention biases for stimuli that signal threat and interpretations reflecting danger or threat have been linked to clinical anxiety in children (Vasey and MacLeod 2001). These findings have been informative in the development of treatments for anxiety disorders in youth. Only two studies have looked at whether these processes are applicable to Latino youth or how culture may influence their impact on anxiety.

In one study described above, Varela et al. (2004) examined whether Mexican and Mexican American children and their parents produced more somatic and anxiety interpretations to ambiguous scenarios than European American children and their parents and whether these interpretations were related to anxiety reporting. The children were presented with three ambiguous scenarios based on the work of Chorpita et al. (1996) and Barrett et al. (1996) and asked to provide interpretations to the scenarios. The children and both of their parents were also asked to discuss the three scenarios for 5 minutes each. The children and parent anxious interpretations were not related to anxiety for any of the groups. In a second study conducted by Suarez-Morales and Bell (2006), Latino (n = 138), Caucasian (n = 88), and African American (n = 66) children were administered the Worry/Oversensitivity subscale of the RCMAS and the Children’s Opinion of Everyday Life Events-Revised questionnaire (Suarez and Bell-Dolan 2001), a measure of information processing including interpretation, subjective probability in judgments, and problem solving biases in response to ambiguous hypothetical situations paralleling the work of Chorpita et al. (1996) and Barrett et al. (1996). There were no differences in the manner in which worry related to interpretive biases between Latino and Caucasian children. Specifically, worry was a significant predictor of negative spontaneous interpretations and ratings of threat for the ambiguous situations independent of these two cultural groups. There were only minimal differences between the Caucasian and African American youth.

In all, the scant literature in this area shows that parent control, more specifically father control, seems to be associated with less anxiety for Latinos in the United States than for European Americans, whereas mother control may have similar effects across cultures. In terms of culture and the relationship between cognitive biases and ethnicity, the two studies reviewed suggest that there are no variations in the manner in which Latino and white non-Latino youth process information and in how cognitive processes link to anxiety across the two groups.

Influences of Immigration and Acculturation

Immigration to the United States and engaging in the acculturation process carry a large number of ecological and psychological challenges that undoubtedly have an impact on children’s mental health. A large body of literature documents such effects on the mental health of the Latino population in general (for reviews see Cervantes and Castro 1985; Gamst et al. 2002; Griffith 1982; Moyerman and Forman 1992; Rogler et al. 1991) and some literature has emphasized the effects of such challenges on anxiety development in Latino youth.

The literature is clear that psychosocial stressors are strongly linked to poor adjustment in children and adolescents (e.g., Compas 1987; Pryor-Brown and Cowen 1989; Rutter 1994). Unfortunately, Latino youth in the United States face a number of stressors such as discrimination, lower access to health care and education, and poverty with implications for anxiety (Padilla et al. 2006; Ramirez and de la Cruz 2003). For example, Parke et al. (2004) found that, overall, economic stress affects Mexican American families in a similar fashion to European American families to produce internalizing symptoms in youth. Other research has found a strong link between perceived discrimination and anxiety among Puerto Rican and Mexican American youth (Phinney et al. 1998; Szalacha et al. 2003).

Beyond the ecological challenges discussed above, Latino youth in the United States face a number of unique socio-cultural circumstances related to the acculturation process that have implications for their adjustment. Acculturation as a construct has been comprehensively discussed in the literature (see Chun et al. 2003 for a thorough review and discussion of the literature). Most researchers agree that acculturation is a multidimensional and dynamic process of cultural change that occurs when two cultural groups come together (Berry 2003). Social cognitions and motivations, one’s identity in a social context and related perceived stigmas are also influential processes in acculturation (Padilla and Perez 2003). Considering the evolution of the meaning of acculturation over time and its complexity, it is not surprising that its association with the mental health of Latinos has been mixed with some research showing a positive relationship and some showing a negative one (Rogler et al. 1991). In the area of childhood anxiety, research focusing on the stress associated with engaging in the acculturation process has been highly informative.

For example, using the Hispanic Children’s Stress Inventory (Padilla et al. 1988), Alva and de Los Reyes (1999) found that culturally derived psychosocial stress was significantly correlated with self report measures of anxiety and depression in 171 ninth grade students from a predominantly Latino public school. Most Latino youth in this study were of Mexican and Central American descent. Psychosocial stress also explained 34% of the variance in scores of a composite anxiety/depression measure above the variance explained by demographic variables. The Hispanic Children’s Stress Inventory is a 30 item scale that gauges the impact of culturally specific stressors. Two sample items are: “I have felt I can’t communicate well with my parents” and “I have found it difficult to live in a home with too many people.” Others have also found that Latino youth who are more involved in activities where they are exposed to varying role expectations report more stress. For instance, expectations to speak Spanish at home and to subscribe to traditional family and gender roles espoused by parents, and being placed in a position to translate for older non-English speaking family members can all be stressful for Latino youth (Bernal et al. 1991; Padilla et al. 1988; Weisskirch and Alva 2002).

One manner to begin disentangling the effects of immigration and acculturation on anxiety is to examine Latino children in their country of origin. For example, Mexican children living in Mexico are presumably not faced with psychosocial challenges related to acculturation or immigration that Mexican American children may be experiencing. Varela and colleagues have employed this strategy in their research examining anxiety in Latino youth with three independent samples (Varela et al. 2004, 2007, 2008). The overall pattern of results from these studies is that Latinos in their native country (i.e., Mexico and Colombia) and Latinos in the United States express more anxiety than white non-Latinos in the United States. This pattern holds even after controlling for differences in SES and social desirability scores as measured by the Lie scale of the RCMAS. Of interest is that a measure of assimilation was not related to anxiety in the Latino groups in the United States in these studies. Assimilation refers to the process of seeking contact and interactions with another cultural group while retracting from one’s own cultural identity (Berry 2003).

Considering that Latinos in the United States and Latinos living in Latin America express more anxiety than white non-Latinos in the United States, Varela et al. hypothesize that culture related phenomena may be more important in driving these differences than factors associated with psychosocial stressors related to being an ethnic minority and migration. How cultural models drive cross-cultural variations in anxiety expression has yet to be fully elucidated.

Future Directions

The anxiety literature with Latino children is nascent and provides ample opportunity for growth in this area. A number of excellent reviews and frameworks for guiding future research in the cross-cultural field emphasize the need for research that considers primarily the influence of culture on mental health in ethnic populations including Latinos (Marin and Marin 1991; van de Vijver and Leung 1997; Kitayama and Cohen 2007; Fonseca et al. 1994; Good and Kleinman 1985; Kirmayer 1997). In this section, we highlight what we consider to be limitations of the literature reviewed and use these limitations along with the rich findings reviewed as the bases for recommendations to advance our understanding of how culture impacts anxiety in Latino youth.

One limitation of the literature in this area is the sheer scarcity of studies examining cultural effects on anxiety development and expression in Latino youth. A number of the studies we reviewed here, particularly those emanating from our research lab (Varela and colleagues), were cited in more than one section when discussing different angles of anxiety in Latino youth. An even more basic need in the literature is to establish normative patterns of anxiety expression with Latino youth so that valid conclusions can be made about cross-cultural comparisons. The extant literature shows Latino youth express more anxiety than their white non-Latino counterparts but research has yet to show the meaning behind these elevations for Latinos. That is, it is unclear what, if any, effect high anxiety expression has in the functioning of Latino youth. Another limitation of the present literature is the focus on community samples. With the exception of studies conducted by Guarnaccia et al. (2005), Lopez et al. (in press), and Pina and Silverman (2004), none of the other youth-focused studies reviewed in relation to cultural influences in anxiety employed clinical samples. There is no doubt that focusing on non-clinical samples is important in informing our understanding of factors linked with normative functioning and development in the area of anxiety. Such research can help inform precursors to anxiety disorders and inform prevention and intervention efforts. However, for the field in this area to move forward, more studies focusing on how cultural models influence mechanisms of functioning in the youth who are afflicted the most by anxiety (i.e., those meeting criteria for a disorder) will need to be conducted.

A third limitation to the literature reviewed is the lack of information presented on the cross-cultural validity of the measures used in the studies. As we point out in the Assessment segment of this article, to make meaningful cross-cultural comparisons and generalizations in processes associated with anxiety development one must show that the measurement of such construct is equivalent across cultures. Of the reviewed studies dealing with the influence of culture on anxiety only Varela and Biggs (2006), Varela et al. (2008), and Varela et al. (in press) present information on the cross-cultural validity of the measures used beyond presenting internal consistency coefficients for the different cultural groups (e.g., Hui and Triandis 1985; Knight and Hill 1998). A fourth limitation of most of the literature reviewed is the lack of examination of the possible psychosocial effects of environmental challenges associated migration and with being an ethnic minority on children’s anxiety. A number of studies do not include a measure of cultural affiliation or acculturation to mainstream culture. In addition, most studies do not indicate the generation of the child and parent participants (e.g., first generation immigrants, second generation immigrants, etc.). One recommended approach is to control for potential ecological effects on anxiety by including youth residing in Latin America who are similar in SES, education, and other demographic characteristics to the Latino youth in the United States under study in future research. In addition, one could also directly measure the culture and context specific variables (e.g., collectivism, stress associated with being first generation immigrant) that are purported to effect the dimensions of anxiety.

These limitations notwithstanding, the literature reviewed in this article presents some exciting findings and promising new areas of investigative pursuit. It is clear that culture has an influence over the various dimensions of emotion experience and expression. Based on the literature discussed here, there are a number of content areas in which more research is necessary to make better conceptual and empirical linkages between cultural models and anxiety in the Latino youth population.

There is a need to develop and test conceptual models that can better explain potential associations between general cultural perceptions and understanding of mental health and illness and culturally sanctioned expressions of anxiety, nervios and somatic symptoms for example. The cultural idioms nervios and ataques de nervios, and somatic complaints appear to represent the experience and expression of symptomatology that is to a large extent socially constructed and not well captured by current nosology. A better understanding of these terms and symptoms will entail approaching their examination first from an ethnographic perspective that produces a good understanding of what nervios and ataques de nervios or physical symptoms mean to the children. For example, although in the studies by Guarnaccia et al. and Lopez et al. 9–17-year-old children were asked directly if they had ever had an ataque de nervios, the term was not defined, making conclusions about its meaning to children difficult. Nonetheless, that children recognize this term and 4–9% of them report having experienced an ataque de nervios is compelling evidence that this idiom needs to be examined further. In particular its association with affective and anxiety disorders, specially panic, make this idiom important in our understanding of how Latino youth may express emotional, cognitive, and arousal states that we tend to associate with the construct of anxiety.

Similarly, it is not clear why Latino youth report more somatic symptoms than white non-Latino youth or what somatic symptoms signify for Latino youth. For example, at least two studies have found that Latino youth report more fear of the consequences of anxiety including somatic symptoms (i.e., anxiety sensitivity) than white non-Latino youth; however, the relationship between anxiety sensitivity and anxious or somatic responding is stronger for the white non-Latino youth than for the Latinos (Weems et al. 2002). One line of future inquiry in this area may be rooted in the cultural view that Latinos perceive mental health to exist on a continuum from benign ameliorable conditions likely expressed as nervios or somatic symptoms to an irrevocable severe state of mental illness known as locura or literally craziness (Guarnaccia et al. 1989; Jenkins 1988a). From this perspective, it is perfectly acceptable to report somatic complaints but Latino youth also know that the long-term consequences of continuing to experience troubling conditions may be severe and irreparable; thus, anxiety sensitivity for them may be a healthy expression of a realistic fear, therefore the higher reports of anxiety sensitivity. In turn, repeated exposure to the message that somatic symptoms related to anxiety carry negative consequences may habituate Latino youth to this belief and not generate as much emotional distress or associated somatic problems in them as it does for white non-Latino youth (Varela et al. 2007).

We also recommend the examination of specific moderating and mediating variables that may help explain the association between anxiety symptoms and collectivistic oriented societies. Based on the literature with adults, one promising line of investigation in this area may be to examine preferences for socially reticent behavior at the personal and cultural level and fear of negative repercussions for deviations from social norms (Heinrichs et al. 2006).

Finally, based on the literature on parenting and anxiety with Latino youth, we propose that research in this area should emphasize two fronts. Parental control appears to have variable effects on children’s anxiety depending on the cultural context (Luis et al. 2008; Varela et al. in press) and the gender of the parent (Varela et al. in press). Considering that gender role expectations may vary or be dissimilarly emphasized across cultures, future research in this area should examine the effect of the child’s gender in how parenting relates to childhood anxiety. For example, it is possible that controlling parenting may have a more pernicious effect on white non-Latino boys than Latino youth in general because white non-Latino youth, boys in particular, may be more culturally expected to be independent and self-sufficient. Second, research on the differential effects of cross-cultural parenting in childhood anxiety should move to examine youth diagnosed with psychiatric disorders. The scant research to date has been conducted with community samples. Thus, it is unclear whether the preliminary findings of Varela and colleagues (Luis et al. 2008; Varela et al. in press) are relevant for youth with more severe forms of anxiety or if differential effects of controlling parenting are not relevant for clinically anxious youth.

Overall, anxiety development and expression in Latino youth is a very promising area of research, but much more needs to be done so that we can adequately meet the needs of what is to be one of the largest segments of the population in the United States. Specification of conceptual models designed to explain how discrete cultural phenomena influence anxiety experience and expression in a Latino cultural context will facilitate and help move research in this field forward.

References

Achenbach, T. M., Bird, H. R., Canino, G., Phares, V., Gould, M. S., & Rubio-Stipec, M. (1990). Epidemiological comparisons of Puerto Rican and U.S. mainland children: Parent, teacher, and self-reports. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 29, 84–93. doi:10.1097/00004583-199001000-00014.

Achenbach, T. M., & Edelbrock, C. S. (1983). Manual for the child behavior checklist and revised child behavior profile. Burlington, VA: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont.

Achenbach, T. M., & Edelbrock, C. (1986). Manual for the teacher’s report form and teacher version of the child behavior profile. Burlington, VA: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont.

Achenbach, T. M., & Edelbrock, C. (1987). Manual for the youth self report and profile. Burlington, VA: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont.

Achenbach, T., & Rescorla, L. (2000). Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms and profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families.

Alva, S. A., & de los Reyes, R. (1999). Psychosocial stress, internalized symptoms, and the academic achievement of Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 14, 343–356. doi:10.1177/0743558499143004.

Alvidrez, J. (1999). Ethnic variations in mental health attitudes and service use among low-income African American, Latina, and European American young women. Community Mental Health Journal, 35, 515–530. doi:10.1023/A:1018759201290.

Angold, A., Erkanli, A., Farmer, E. M. Z., Fairbank, J. A., Burns, B. J., Keeler, G., et al. (2002). Psychiatric disorder, impairment, and service use in rural African American and White youth. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59, 893–901. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.893.

Angold, A., Prendergast, M., Cox, A., Harrington, R., Simonoff, E., & Rutter, M. (1995). The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA). Psychological Medicine, 25, 753–793.

Arcia, E., Castillo, H., & Fernandez, M. C. (2004). Maternal cognitions about distress and anxiety in young Latino children with disruptive behaviors. Transcultural Psychiatry, 41, 99–119. doi:10.1177/1363461504041356.

Baer, R. D., Weller, S. C., de Alba, J. G., Glazer, M., Trotter, R., Pachter, L., et al. (2003). A cross-cultural approach to the study of the folk illness nervios. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 27, 315–337. doi:10.1023/A:1025351231862.

Barlow, D. H. (2002). Origins of apprehension, anxiety disorders, and related disorders. In D. H. Barlow (Ed.), Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic (pp. 252–291). New York: Guilford Press.

Barlow, D. H., Chorpita, B. F., & Turovsky, J. (1996). Fear, panic, anxiety, and disorders of emotion. In D. A. Hope (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation, 1995: Perspectives on anxiety, panic, and fear (pp. 251–328). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Barrett, P. M., Rapee, R. M., Dadds, M. M., & Ryan, S. M. (1996). Family enhancement of cognitive style in anxious and aggressive children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 24, 187–203. doi:10.1007/BF01441484.

Bauermeister, J., Colon-Fumero, O., Villamil-Forastieri, B., & Spielberger, C. D. (1986). Reliability and validity of the Spanish version of the state-trait anxiety inventory for Puerto Rican and Panamenian children. Revista Interamericana de Psicología, 20, 1–19.

Bernal, M. E., Saenz, D. S., & Knight, G. P. (1991). Ethnic identity and adaptation of Mexican American youths in school settings. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 13, 135–154. doi:10.1177/07399863910132002.

Berry, J. W. (2003). Conceptual approaches to acculturation. In K. M. Chun, P. B. Organista, & G. Marin (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research (pp. 17–37). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Berstein, G. A., & Borchardt, C. M. (1991). Anxiety disorders of childhood and adolescence: A critical review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 30, 519–532.

Bravo, M., Ribera, J., Rubio-Stipec, M., Canino, G., Shrout, P., Ramirez, R., et al. (2001). Test-retest reliability of the Spanish version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV). Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 29, 433–444. doi:10.1023/A:1010499520090.

Canino, G., Shrout, P. E., Rubio-Stipec, M., Bird, H. R., Bravo, M., Ramirez, R., et al. (2004). The DSM-IV rates of child and adolescent disorders in Puerto Rico. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61, 85–93. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.61.1.85.

Cattell, R. B., & Scheier, I. H. (1961). The meaning and measurement of neuroticism and anxiety. Oxford, England: Ronald.

Cervantes, R. C., & Castro, F. G. (1985). Stress, coping, and Mexican American mental health: A systematic review. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 7, 1–73. doi:10.1177/07399863850071001.

Chorpita, B. F., Albano, A. M., & Barlow, D. H. (1996). Cognitive processing in children: Relation to anxiety and family influences. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 25, 170–176. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp2502_5.

Chorpita, B. F., & Barlow, D. H. (1998). The development of anxiety: The role of control in the family environment. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 3–21. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.124.1.3.

Chorpita, B. F., Tracey, S. F., Brown, T. A., Collica, T. J., & Barlow, D. H. (1997). Assessment of worry in children and adolescents: An adaptation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35, 569–581. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(96)00116-7.

Chorpita, B. F., Yim, L., Moffitt, C., Umemoto, L. A., & Francis, S. E. (2000). Assessment of symptoms of DSM-IV anxiety and depression in children: A revised child anxiety and depression scale. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38, 835–855. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00130-8.

Chun, K. M., Organista, P. B., & Marin, G. (Eds.). (2003). Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Compas, B. E. (1987). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310–357.

Costello, E. J., Angold, A., Burns, B. J., Erkanli, A., Stangl, D. K., & Tweed, D. L. (1996). The Great Smoky Mountains study of youth: Functional impairment and serious emotional disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry, 53, 1137–1143.

Craske, M. G. (1999). Anxiety disorders: Psychological approaches to theory and treatment. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Deater-Deckard, K., & Dodge, K. A. (1997). Externalizing behavior problems and discipline revisited: Nonlinear effects and variation by culture, context, and gender. Psychological Inquiry, 8, 161–175. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0803_1.

Derogatis, L. R. (2000). BSI-18: Administration, scoring, and procedures manual. Minneapolis, MN: Pearson Assessments.

de Minzi, M. C. R., & Sacchi, C. (1999). Variables moderadoras del estres. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicologia, 31, 355–365.

Draguns, J. G. (1973). Comparisons of psychopathology across cultures: Issues, findings, directions. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 4, 9–47. doi:10.1177/002202217300400104.

Eagleton, T. (2000). The idea of culture. Oxford, England: Blackwell.

Escobar, J. I., Nervi, C. H., & Gara, M. A. (2000). Immigration and mental health: Mexican Americans in the United States. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 8, 64–72. doi:10.1093/hrp/8.2.64.

Fonseca, A. C., Yule, W., & Erol, N. (1994). Cross-cultural issues. In T. H. Ollendick, N. J. King, & W. Yule (Eds.), International handbook of phobic and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents (pp. 67–84). New York: Plenum Press.

Gabrielidis, C., Stephan, W. G., Ybarra, O., Pearson, V. M., & Villareal, L. (1997). Preferred styles of conflict resolution: Mexico and the United States. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 28, 661–677. doi:10.1177/0022022197286002.

Gamst, G., Dana, R. H., Der-Karabetian, A., Aragon, M., Arellano, L. M., & Kramer, T. (2002). Effects of Latino acculturation and ethnic identity on mental health outcomes. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 24, 479–504. doi:10.1177/0739986302238216.

Ginsburg, G. S., & Silverman, W. K. (1996). Phobic disorders in Hispanic and European-American youth. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 10, 517–528. doi:10.1016/S0887-6185(96)00027-8.

Glover, S. H., Pumariega, A. J., Holzer, C. E., Wise, B. K., & Rodriguez, M. (1999). Anxiety symptomatology in Mexican-American adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 8, 47–57. doi:10.1023/A:1022994510944.

Good, B., & Kleinman, A. (1985). Culture and anxiety: Cross-cultural evidence for the patterning of anxiety disorders. In A. H. Tuma & J. D. Maser (Eds.), Anxiety and the anxiety disorders (pp. 297–323). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Gould, M., Bird, H., & Staghezza, J. B. (1993). Correspondence between statistically derived behavior problem syndromes and child psychiatric diagnoses in a community sample. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 21, 287–313. doi:10.1007/BF00917536.

Gray, J. A. (1991). Fear, panic, and anxiety: What’s in a name? Psychological Inquiry, 2, 77–78. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0201_18.

Griffith, J. (1982). Relationship between acculturation and psychological impairment in adult Mexican Americans. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 5, 431–459. doi:10.1177/073998638300500404.

Gross, D., Fogg, L., Young, M., Ridge, A., Cowell, J. M., Richardson, R., et al. (2006). The equivalence of the Child Behavior Checklist/11/2-5 across parent race/ethnicity, income level, and language. Psychological Assessment, 18, 313–323. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.18.3.313.

Guarnaccia, P. J., Canino, G., Rubio-Stipec, M., & Bravo, M. (1993). The prevalence of Ataques de Nervios in the Puerto Rico disaster study. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 181, 157–165. doi:10.1097/00005053-199303000-00003.

Guarnaccia, P. J., DeLaCancela, V., & Carrillo, E. (1989a). The multiple meanings of ataques de nervios in the Latino community. Medical Anthropology, 11, 47–62.

Guarnaccia, P. J., & Farias, P. (1988). The social meanings of nervios: A case study of a Central American woman. Social Science and Medicine, 26, 1223–1231. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(88)90154-2.

Guarnaccia, P. J., Martinez, I., Ramirez, R., & Canino, G. (2005). Are ataques de nervios in Puerto Rican children associated with psychiatric disorder? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 44, 1184–1192. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000177059.34031.5d.

Guarnaccia, P. J., Parra, P., DesChamps, A., Milstein, G., & Argiles, N. (1992). Si Dios quiere: Hispanic families’ experiences of caring for a seriously mentally ill family member. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 16, 187–215. doi:10.1007/BF00117018.

Guarnaccia, P. J., Rivera, M., Franco, F., & Neighbors, C. (1996). The experiences of ataques de nervios: Towards an anthropology of emotions in Puerto Rico. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 20, 343–367. doi:10.1007/BF00113824.

Guarnaccia, P. J., Rubio-Stipec, M., & Canino, G. (1989b). Ataques de nervios in the Puerto Rican Diagnostic Interview Schedule: The impact of cultural categories on psychiatric epidemiology. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 13, 275–295. doi:10.1007/BF00054339.

Harre, R., & Parrott, W. G. (1996). The emotions: Social, cultural, and biological dimensions. London, England: Sage Publications.

Heinrichs, N., Rapee, R. M., Alden, L. A., Bogels, S., Hofmann, S. G., Oh, K. J., et al. (2006). Cultural differences in perceived social norms and social anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 1187–1197. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.09.006.

Hofstede, G. (1984). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hui, C. H., & Triandis, H. C. (1985). Measurement in cross-cultural psychology: A review and comparison of strategies. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 16, 131–152. doi:10.1177/0022002185016002001.

Ispa, J. M., Fine, M. A., Halgunseth, L. C., Harper, S., Robinson, J., Boyce, L., et al. (2004). Maternal intrusiveness, maternal warmth, and mother-toddler relationship outcomes: Variations across low-income ethnic and acculturation groups. Child Development, 75, 1613–1631. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00806.x.

Izard, C. E., & Blumberg, S. H. (1985). Emotion theory and the role of emotions in anxiety in children and adults. In A. H. Tuma & J. D. Maser (Eds.), Anxiety and the anxiety disorders (pp. 109–129). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

Jenkins, J. H. (1988a). Ethnopsychiatric interpretations of schizophrenic illness: The problem of nervios within Mexican-American families. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 12, 301–329. doi:10.1007/BF00051972.

Jenkins, J. H. (1988b). Conceptions of schizophrenia as a problem nerves: A cross-cultural comparison of Mexican-Americans and Anglo-Americans. Social Science and Medicine, 26, 1233–1243. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(88)90155-4.

Joiner, T. E., Catanzaro, S. J., & Laurent, J. (1996). Tripartite structure of positive and negative affect, depression, and anxiety in child and adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 105, 401–409. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.105.3.401.

Kashani, J. H., & Orvaschel, H. (1990). A community study of anxiety in children and adolescents. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 147, 313–318.