Abstract

Background

Regular school attendance is foundational to children’s success but school absenteeism is a common, serious, and highly vexing problem. Researchers from various disciplines have produced a rich yet diverse literature for conceptualizing problematic absenteeism that has led to considerable confusion and lack of consensus about a pragmatic and coordinated assessment and intervention approach.

Objective

To lay the foundation and suggested parameters for a Response to Intervention (RtI) model to promote school attendance and address school absenteeism.

Methods

This is a theoretical paper guided by a systematic search of the empirical literature related to school attendance, chronic absenteeism, and the utilization of an RtI framework to address the needs of school-aged children and youth.

Results

The RtI and absenteeism literature over the past 25 years have both emphasized the need for early identification and intervention, progress monitoring, functional behavioral assessment, empirically supported procedures and protocols, and a team-based approach. An RtI framework promotes regular attendance for all students at Tier 1, targeted interventions for at-risk students at Tier 2, and intense and individualized interventions for students with chronic absenteeism at Tier 3.

Conclusions

An RtI framework such as the one presented here could serve as a blueprint for researchers as well as educational, mental health, and other professionals. To develop this model and further enhance its utility for all youth, researchers and practitioners should strive for consensus in defining key terms related to school attendance and absenteeism and focus more on prevention and early intervention efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Regular school attendance is fundamental to children’s success in academic, language, social, and work-related domains. School attendance provides youth a setting for academic development, a language-rich environment, opportunities to develop social competence and relationships, and experiences that nurture work-related skills such as persistence, problem-solving, and the ability to work with others to accomplish a goal. Regular school attendance is associated with higher standardized test scores and grades (Epstein and Sheldon 2002; Tanner-Smith and Wilson 2013). In addition, students who graduate from high school are more likely to become employed and have higher salaries and less likely to require public assistance and engage in criminal activity compared to those who do not graduate from high school (Christenson and Thurlow 2004). Regular attendance has been defined as 5 or fewer school days missed per year (Balfanz and Byrnes 2012).

Conversely, a vexing but increasingly common problem for educational, mental health, and other professionals is school absenteeism. Problematic absenteeism has been defined as (1) missing at least 25 % of total school time for at least 2 weeks, (2) severe difficulty attending classes for at least 2 weeks with significant interference in a youth’s or family’s daily routine, and/or (3) absences for at least 10 days of school during any 15-week period while school is in session, with an absence defined as 25 % or more of school time missed (Kearney 2008a). Problematic absenteeism thus includes complete and partial absences from school as well as morning misbehaviors in an attempt to miss school and/or substantial distress at school that precipitates pleas for future nonattendance (Kearney 2007a; Peguero et al. 2011).

Problematic school absenteeism is prevalent. The rate of chronic absenteeism (defined as missing 10+ % of the school year) among American youth may be 10–15 %, and is particularly more evident among low-income students (Balfanz and Byrnes 2012). Others estimate the prevalence of all types of absentee behavior, including morning misbehaviors and school-based distress, to be 28–35 % (Kearney 2001; Pina et al. 2009). In addition, graduation rates for several large American cities are poor and other countries experience significant rates of school absenteeism and dropout (EPE Research Center 2008; Kearney 2008b).

Problematic school absenteeism is also debilitating. Absenteeism is most prominently linked to eventual school dropout (Rumberger 2011). Other negative correlates of chronic absenteeism include hazardous behaviors such as substance abuse, violence, suicide attempt, risky sexual behavior, pregnancy, delinquency-related behaviors, injury, and illness (Kearney 2008b). Absenteeism can also be embedded within larger problems such as anxiety, mood, or disruptive behavior disorders as well as family, school, and community exigencies (Kearney and Albano 2004; Knollman et al. 2010; McShane et al. 2001). In addition, longitudinal studies reveal severe consequences of absenteeism into adulthood, including economic deprivation and social, marital, occupational, and psychiatric problems (Hibbett et al. 1990; Tramontina et al. 2001; US Census Bureau 2005).

School absenteeism is prevalent and debilitating but educational, mental health, and other professionals who address this problem must navigate a diverse literature of varying conceptualizations. Researchers in several disciplines cover this area, including education, psychology, criminal justice, law, social work, nursing, medicine, and sociology. As such, various terms have been devised historically to describe problematic absenteeism. These terms are usually ensconced in a particular field and have thus led to a fractured literature (Kearney 2003). Psychologists, for example, commonly study anxiety-based absenteeism idiographically and clinically whereas educational and criminal justice experts commonly study delinquent-based absenteeism nomothetically and systemically. As a result, standardized terminology is lacking and a common framework to define a continuum of support based on student attendance patterns and related needs has been elusive.

The major purpose of this article is to propose the Response to Intervention (RtI) model as that framework. This model is meant as a blueprint for professionals who strive to align assessment, preventative efforts, and interventions to student attendance patterns and related needs. The following sections cover RtI principles and concepts, the compatibility of an RtI model to conceptualize attendance and absenteeism, and a proposed three-tiered system of support based on student needs that include assessment and intervention recommendations.

Response to Intervention

Response to Intervention (RtI) is a popular model to address academic and related problems in schools (Clark and Alvarez 2010). RtI refers to a systematic and hierarchical decision-making process to assign evidence-based strategies based on student need and in accordance with regular progress monitoring (Fox et al. 2010). RtI models vary but key principles include a systems-level approach, proactive and preventive efforts, alignment of interventions to student needs, data-based decision-making and problem-solving, and effective practices (Barnes and Harlacher 2008). RtI has been utilized for youth with learning difficulties in reading, writing, or mathematics as well as youth with school-based disruptive behavior, emotional disturbances, and problematic social behavior (Hawkin et al. 2008).

Response to Intervention is most often conceptualized as a three-tiered service delivery approach with universal, targeted, and intensive interventions (Barnes and Harlacher 2008). Tier 1 or universal interventions are directed toward all students and involves a core set of strategies (e.g., common curriculum) and regular screening (e.g., 2–3 times per year) to identify students who are not successfully benefitting from these core strategies (e.g., those with reading difficulties) (Fletcher and Vaughn 2009). A well-functioning three-tiered system of supportive Tier 1 activities alone should address the needs of 80–90 % of students (Searle 2010). Tier 2 or targeted interventions are directed toward at-risk students who require additional support (e.g., small group instruction) beyond universal strategies (Sailor 2009). Progress monitoring is conducted at Tier 2 as well, though more frequently than at Tier 1 (e.g., 1–2 times per month). Approximately 5–10 % of students may need additional support at this level (Searle 2010). Tier 3 or intensive interventions are directed toward students with severe or complex problems who require a more individualized and concentrated approach (e.g., one-on-one instruction) and more frequent (e.g., weekly) progress monitoring. Only 1–5 % of students should warrant support at this level (Searle 2010).

Rationale for RtI for School Attendance and Absenteeism

An RtI model may be particularly compatible for promoting school attendance and for addressing school absenteeism because the RtI and absenteeism literatures have emerged along key parallel paths over the past 25 years. These parallel paths include a focus on (1) the need for early identification and intervention with progress monitoring, (2) functional behavioral assessment, (3) empirically supported procedures and protocols to reduce obstacles to academic achievement (including absenteeism), (4) compatibility with other multi-tier approaches, and (5) a team-based approach for implementation (Sailor et al. 2009). These points are briefly discussed next.

First, an RtI model eschews a “wait to fail approach” and instead emphasizes early identification and treatment. This approach is especially important for absenteeism because several studies reveal that even a small amount of absences are linked to more severe problems (Calderon et al. 2009; Henry 2007; Henry and Huizinga 2007; Redmond and Hosp 2008; Schwartz et al. 2009). Unfortunately, many schools wait to intervene until a student has surpassed a legal limit (e.g., 10 absences in 1 semester; Kelly 2010). A proactive RtI model to promote school attendance and address absenteeism as it first occurs, and before other, more intransigent or comorbid problems develop, could be a powerful approach to lessen negative outcomes for students.

Second, RtI models often emphasize functional behavioral assessment and analysis that involves identifying the maintaining variables of a problem behavior and then designing interventions tailored to those variables (Watson et al. 2011). Common functions include escape from aversive situations, attention-seeking, sensory reinforcement, and tangible reinforcement (Herzinger and Campbell 2007). Such an approach fits well with a functional model of absenteeism that poses that youths miss school to avoid school-based stimuli that provoke negative affectivity, escape from aversive school-based social and/or evaluative situations, pursue attention from significant others, and/or pursue tangible rewards outside of school (Kearney and Silverman 1996). A functional model of absenteeism has established methods of assessment to align interventions to the maintaining variables (Haight et al. 2011; Kearney 2006) (see also Tier 2 interventions later).

Third, instructional and intervention approaches linked to RtI and those designed to address absenteeism have received increasingly greater empirical support. RtI approaches include empirically supported instructional practices such as enhancing comprehension to improve reading, utilizing summaries to improve writing, and pairing students with peers to improve math skills (Shapiro et al. 2011). Implementation of RtI has led to improved reading fluency and academic achievement scores and less referrals to special education (Fletcher and Vaughn 2009). Interventions for absenteeism include those targeted toward individual students as well as those more systemic in nature (Kearney 2008b). In addition, RtI approaches are problem-solving oriented or protocol driven. Problem-solving approaches isolate specific skill deficits and shape targeted interventions for one or more students, whereas protocol driven approaches utilize a standard set of interventions to remediate an academic or behavioral problem (Jimerson et al. 2007). Such approaches may be useful for youths with absenteeism given their heterogeneous (internalizing and externalizing) behavior problems (deficits) and the fact that specific intervention protocols to address absenteeism have been designed (e.g., Kearney and Albano 2007).

Fourth, an RtI model is compatible with other multi-tier approaches such as those used in mental health delivery systems (Sailor et al. 2009) as well as a Positive Behavioral Interventions and Support (PBIS) framework with an emphasis on prevention (Lewis et al. 2010). An RtI model is also compatible with recent calls from scholars to develop an approach that includes all youth with absenteeism (Kearney 2008b; Lyon and Cotler 2009; Rodriguez and Conchas 2009). In addition, an RtI model can account for the many contextual variables that surround absenteeism and be designed to provide additive interventions depending on the severity of student needs. A particular advantage of an RtI approach is that it may resonate better with educational professionals and others who are familiar with its increasingly well-known and multi-tiered framework.

Fifth, an RtI model requires a team approach to identify youths with academic and behavioral difficulties, assess for specific deficits, implement multi-tiered interventions, and monitor intervention fidelity and effectiveness (King et al. 2011). This approach is consistent with recommendations from school absenteeism researchers who advocate for collaborative efforts in assessment and intervention (DeSocio et al. 2007; Kearney 2008a; Reid 2003b). Indeed, a fully implemented RtI model to promote attendance and address absenteeism would require a team of school-based professionals, parents, peers, community-based medical and mental health professionals, and legal personnel such as lawyers and police, juvenile detention, and probation officers (Richtman 2007).

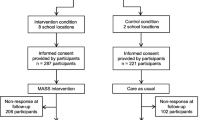

The following sections cover Tier 1, 2, and 3 interventions and assessment recommendations for an RtI model for attendance and absenteeism. The model (Fig. 1) is intended as a blueprint for educational, mental health, and other professionals who wish to implement and test this approach, but with the understanding that such a model must be modified to fit the individual needs of students and the unique characteristics and available resources of a given school. Articles for review were chosen on the basis of whether empirical support was provided for a specific intervention vis-à-vis its utility and relevance to school absenteeism.

Tier 1: Universal Interventions to Promote School Attendance

Tier 1 interventions are directed toward all students and involve a core set of strategies and regular screening to promote attendance and identify students who are not benefitting from these core strategies. Tier 1 interventions would thus involve school-wide and other broad-based efforts that are discussed next.

School Climate Strategies

School-oriented factors most predictive of absenteeism include aspects of poor school climate such as perceptions of an unsafe school environment, inadequate peer and teacher support, and inconsistent rules (Way et al. 2007). Boredom, uninteresting classes, inflexible disciplinary practices, poor student–teacher relationships, poor school connectedness, inadequate attention to individual academic needs, and lax attendance management practices propel absenteeism and later school dropout as well (Bridgeland et al. 2006; National Center for Education Statistics 2006). Conversely, positive school climate, including constructive student–teacher relationships and less grade retention, is moderately linked to attendance and less dropout (Brookmeyer et al. 2006; Jimerson et al. 2002).

Whole-school interventions to enhance a positive school climate can be relevant for Tier 1 strategies to promote school attendance and prevent absenteeism, especially at middle and high school levels. PBIS, for example, includes setting clear behavioral expectations, rewarding students for positive behaviors, emphasizing prosocial skills and behaviors, collecting and analyzing disciplinary data regularly, and implementing evidence-based academic and behavioral practices (Bradshaw et al. 2009; Sailor et al. 2006). PBIS may be implemented by a team of teachers, psychologists, counselors, or social workers with administrators, parents, and community members (Sugai and Horner 2006). PBIS has been linked to improved academic achievement and student perceptions of school safety as well as less office disciplinary referrals and school suspensions (Lassen et al. 2006).

Positive Behavioral Interventions and Support components in an RtI model to promote school attendance and prevent absenteeism might be adapted to include increased student involvement in school attendance policies, examination of patterns in attendance data, and immediate response to instances of absenteeism. The role of the classroom or homeroom teacher may be restructured to identify students at risk for absenteeism and to inform school administrators and parents about an absence (Kearney and Bates 2005). School-based personnel may also find it useful to develop a culture that recognizes regular attendance and discourages absenteeism. Examples include award ceremonies and tangible rewards for good attendance as well as regular monitoring of absences and immediate parent contact following an absence (Epstein and Sheldon 2002; Weller 2000).

Safety-Oriented Strategies

Another whole-school intervention approach relevant to Tier 1 efforts to promote attendance includes bullying and violence prevention and conflict resolution practices (Nickerson and Martens 2008). These strategies may be relevant to all grade levels. Youths who are bullied or who witness violence at school are at high risk for absenteeism (Dake et al. 2003). The Olweus Bullying Prevention Program is a whole-school intervention involving clear and well-enforced school rules regarding bullying, classroom discussions, immediate interventions, follow-up meetings, parental engagement, and community participation (Olweus and Limber 2010). Other anti-bullying programs focus on curriculum changes, increased supervision, social skills and support groups, behavioral contracts, counseling for victims and perpetrators, and mentoring (Vreeman and Carroll 2007). Beane et al. (2008) reported that their Bully Free Program was associated with increased school attendance between baseline (90.8 %) and after 175 days of program implementation (97.8 %).

Bullying prevention relates closely to school-wide procedures to reduce violence. These procedures include increased adult supervision in areas where bullying has occurred, security enforcement (e.g., cameras), crisis plans for responding to violent acts, and availability of therapeutic approaches such as anger management classes, parent training and family therapy, and peer mediation programs (Ehiri et al. 2007). Enhancing safe learning environments is a key component of many absenteeism and dropout prevention programs (Johnson 2009; Smink and Reimer 2005).

Health-Based Strategies

Tier 1 interventions to promote attendance could also include school-based health programs. Some of these programs are relevant to all grade levels and serve to increase hand washing, flu immunization, asthma and lice management, dental health, and specialized educational services for students with chronic medical conditions (Andresen and McCarthy 2009; Guevara et al. 2003; Meadows and Le Saux 2004; Sandora et al. 2008). Other programs are geared more toward older youth. Routine medical care has been evaluated for older pregnant youth to avoid out-of-school doctor visits (Barnet et al. 2004). Each of these programs has been shown to boost attendance levels. Broader school-based health services that may also promote attendance include health and nutrition education as well as HIV and STD prevention (Freudenberg and Ruglis 2007).

Mental Health and Social-Emotional Learning

School-based mental health services to promote all students’ mental health and social-emotional learning could also improve attendance as part of a Tier 1 approach. These approaches are generally used for middle and high school youth but can be modified for younger youth. Substance abuse prevention programs involve skills-based, affective, and knowledge-focused programs (Faggiano et al. 2008). Other mental health strategies serve to reduce emotional, learning, and disruptive behavior disorders or enhance coping skills (Weist et al. 2010). Other programs focus on conflict resolution, anger management, peer mediation, coping with divorce or family conflict, and sex education (Brown and Bolen 2008). Mental health programs in schools combined with academic remediation strategies lead to improvements in tardiness, absenteeism, and dropout rates (Hoagwood et al. 2007).

Tier 1 approaches to promote school attendance could also involve social and emotional learning programs (Graczyk et al. 2000). An example is character education, which emphasizes training in core values and life skills to promote social competence and learning (Cheung and Lee 2010). Character education programs enhance attendance (Miller et al. 2008). Snyder et al. (2010) implemented a social-emotional and character development program across 140 interactive lessons. Lessons focused on (1) self-concept (relationship among thoughts, feelings, and behaviors), (2) physical and intellectual actions (e.g., hygiene, nutrition, decision-making skills), (3) social and emotional actions (self-control, time management), (4) interpersonal skills (e.g., empathy, conflict resolution), (5) integrity and self-appraisal, and (6) self-improvement (e.g., goal setting, problem solving, persistence). Schools with the intervention had significantly higher reading and math scores, lower absenteeism, and fewer suspensions and retentions than control schools.

Parental Involvement

Another Tier 1 approach would be to boost parental involvement to promote attendance, which is relevant to youth of all ages. Parental involvement is important for enhancing academic socialization (Hill and Tyson 2009). Parents who are actively interested in a child’s daily and long-term educational activities may have children with less truancy and other school-based misbehaviors (Jeynes 2007; McNeal 1999). Conversely, lax parental supervision is a key risk factor for problematic absenteeism (Ingul et al. 2012).

Strategies to boost parental involvement involve school, family, and community partnerships. Sheldon (2007) examined a school partnership program to help families establish supportive home environments, increase parent–school communication, recruit parents to help at school and serve on school committees, provide information to families about how to help students with homework, and integrate community-based resources to strengthen school programs (p. 268). School-based action teams organized and implemented the involvement activities. Schools that implemented the partnership program evinced significantly greater improvement in attendance than control schools.

Parental involvement could also be enhanced by bridging language and cultural differences between school faculty and parents. Such differences impede communication and lead to parental difficulties deciphering homework assignments, progress reports, and report cards. Suggestions for bridging this gap include using interpreters, engaging in home visits, implementing culturally responsive curricula, promoting integration of cultures within a school, providing school-based child care for parent–teacher conferences, recruiting parents for school-based governing positions and parent–teacher associations, matching better the ethnicity of school personnel to the surrounding community, and issuing invitations to special school-based events that are conducted in various languages and geared toward all family members (Broussard 2003; Garcia-Gracia 2008; Kearney and Bates 2005).

Other Tier 1 Strategies

Tier 1 approaches could also involve helping students adjust or transition to a new school or maintain academic and social skills learned from a previous year. Youths who transition to a new school, especially middle school, and who fail to retain academic skills from the previous year are at particular risk for psychosocial problems and absenteeism (Grills-Taquechel et al. 2010; Kearney 2001). However, these effects can be mitigated by support from school personnel (Cooper and Liou 2007). Applicable Tier 1 approaches might thus include detailed orientation activities and summer bridge and school readiness programs to enhance adaptation to a new school building (Bekman et al. 2011). Parents should also be informed early in the academic year about a school’s attendance policy (Reid 2003a).

Tier 1 approaches could also involve educating school personnel about the warning signs of emerging absenteeism. Examples include frequent departures from class or occasional skipped classes, particularly those involving tests (Gresham et al. 2013). In addition, others claim that boosting student involvement in school-based extracurricular activities is a promising Tier 1 activity to enhance attendance (Lehr et al. 2003).

District-wide task forces could also review existing attendance policies and implement changes to reduce absenteeism. One key change might be less use of suspensions (and expulsions) to address absenteeism because these practices paradoxically lead to greater lag in academic achievement as well as delinquency and school dropout (Stone and Stone 2011). Instead, nuanced and flexible approaches to address instances of absenteeism (as opposed to immediate legal referral) are beneficial (Reid 2003a; Scott and Friedli 2002). Such approaches could intersect well with broader practices to enhance school climate and student engagement and attendance such as (1) customizing curriculum and instruction to individual academic needs, and (2) developing alternative and flexible educational methods that allow for more gradual accumulation of academic credit and minimize grade retention (Martin 2011). In addition, task forces could work with community agencies to streamline educational and social services and apply for grant funding to support the prevention of absenteeism (Bye et al. 2010).

Tier 1 Assessment

A key element of RtI at Tier 1 is regular assessment to identify youth with emerging problems that may require Tier 2 intervention. Academic assessments in an RtI model are often conducted 2–3 times annually (Fletcher and Vaughn 2009). However, the fluid and often urgent nature of absenteeism means that attendance assessments in an RtI model must be ongoing. In addition, RtI teams may wish to monitor attendance, academics, and behavior simultaneously as is recommended in early warning systems (Neild et al. 2007).

Response to Intervention teams at Tier 1 should review attendance data at least twice per month (Mac Iver and Mac Iver 2010). Attendance data can include full-day absences as well as tardiness, skipped classes, and premature departures from campus. In addition, subtle indicators of absenteeism include difficulties getting to or entering school in the morning, frequent visits to the nurse’s office, requests to leave the classroom or to use the restroom, and persistent distress (e.g., crying or clinging) at separation from family members (Kearney and Albano 2007). Attendance assessments can also include office disciplinary referrals, suspensions, behavioral observations, and reports from parents, teachers, guidance counselors, and school-based psychologists, social workers, and nurses (Sailor 2009). RtI teams should also pay special attention to youths with difficulty transitioning from elementary to middle school and from middle to high school, to youths with failing grades in mathematics or English, and to youths with unsatisfactory behavior marks, all of which are key predictors of absenteeism and dropout (Neild et al. 2007; Sinclair et al. 1998).

Students eligible for Tier 2 likely have absentee problems that approach but do not yet surpass a legal limit (e.g., 10 absences in a semester). However, some students do experience severe absenteeism and other problems quickly and must transition immediately to Tier 3 (see later section). Students eligible for Tier 2 likely comprise about 25–35 % of students at this time (Pina et al. 2009). Tier 1 preventative tactics must thus be emphasized heavily in an RtI approach for attendance and absenteeism to insure that no more than 15–20 % of students eventually warrant Tier 2 and Tier 3 supports (Searle 2010), which are described next.

Tier 2: Targeted Interventions for At-Risk Students

Tier 2 interventions are directed toward at-risk students who require additional support beyond the core set of universal (Tier 1) intervention strategies. Tier 2 interventions must include key considerations regarding goals, parent collaboration, and adjunctive supports. These considerations and Tier 2 interventions are discussed next.

Key Considerations for Tier 2

Primary goals at Tier 2 include stabilizing school attendance, developing a clear and gradual strategy for orienting a youth to school, reducing emerging distress and obstacles to attendance, and ruling out competing explanations for absenteeism such as actual school-based threats (e.g., bullying). Secondary goals include establishing regular parent–school contact, identifying and addressing high-risk times for premature departure from the classroom or school, resolving emerging academic deficiencies from nonattendance, or supplying academic work if a child remains home from school (Kearney and Bates 2005; Kearney and Bensaheb 2006).

Tier 2 interventions will also likely require collaboration with parents. Scholars have noted the importance of strong family–school connections to address attendance problems (Kearney and Albano 2007; Murdock et al. 2009). At Tier 2, parents might supervise attendance more closely, refrain from keeping a child home from school, maintain a regular morning routine for school preparation behaviors, and implement consequences for attendance and nonattendance as appropriate (Kearney et al. 2007). In addition, regular parent–school contact has been strongly advocated to resolve emerging challenges to school attendance (Adams and Christenson 2000). Frequent consultations between school-based personnel and parents are recommended regarding a student’s attendance status, grades, required past and present academic work, and policies regarding absenteeism (Kearney 2007b).

Tier 2 interventions for absenteeism may require adjunctive support for comorbid problems. Families may benefit from referrals to a pediatrician (e.g., for somatic complaints), family therapist (e.g., for communication and problem-solving deficiencies), clinical child psychologist (e.g., for psychosocial problems), psychiatrist (e.g., for severe depression), social worker (e.g., for economic assistance), tutor (e.g., for academic problems), and specialists for developmental or learning disorders (Bernstein et al. 1997; Reid 2011; Sewell 2008). Tier 2 could include psychological interventions as well as those implemented systemically to boost student engagement and to provide peer and teacher mentoring. These interventions are described next.

Psychological Interventions for Absenteeism

Psychologists have focused historically on anxiety-based absenteeism via cognitive-behavioral and family-oriented treatments to reduce stress and problematic parent–youth interactions and to increase attendance. Youth-based procedures are used to manage physical and cognitive anxiety symptoms, ease re-entry to missed classes, and resolve obstacles to attendance such as social alienation (Suveg et al. 2005). Key procedures include relaxation training and breathing retraining to help a child control physical aspects of anxiety, cognitive procedures to modify inaccurate beliefs about others or one’s school environment, gradual reintegration into classes, increased participation in extracurricular activities to build friendships, social skills training, and conflict resolution. Cognitive procedures are generally more relevant to older youth. Guidelines for these procedures are available (Eisen and Engler 2006; Heyne and Rollings 2002; Kearney 2007b).

Several outcome studies have been conducted for anxiety-based absenteeism. King et al. (1998) found that cognitive-behavioral treatment (CBT) for youth aged 5–15 years was superior to wait-list control for attendance, fear, anxiety, and depression. Treatment was most effective if a youth returned swiftly to school and if parents and youth were involved in the intervention. Last et al. (1998) found that CBT and education support (control) for youth aged 6–17 years both produced substantial improvements in attendance, fear, anxiety, and depression. Education support involved allowing youths to express concerns about school. Bernstein and colleagues (Bernstein et al. 2000) found that CBT with imipramine for youth aged 10–17 years was superior to placebo for attendance and depression. Heyne et al. (2002, 2011) also found that youth/parent-based CBT for youth aged 7–17 years produced improvements in attendance and distress.

These studies utilized standardized treatment protocols but generally excluded youths with varied attendance patterns, externalizing behavior problems, and little anxiety (Lyon and Cotler 2009). Some have called for expanding personalized interventions to reach a broader range of youth with absenteeism and related problems (La Greca et al. 2009; Last et al. 1998). A nuanced approach that accounts for heterogeneous attendance patterns and symptoms, especially non-anxiety-based cases, and that relies on empirically supported subtypes of absenteeism may thus be particularly necessary at Tier 2. This approach is described next.

Kearney (2007a) identified functions of absenteeism that include avoidance of school-based stimuli that provoke negative affectivity, escape from aversive school-based social and/or evaluative situations, pursuit of attention from significant others, and pursuit of tangible rewards outside of school. The first two functions refer to youths who refuse school for negative reinforcement; the latter two functions refer to youths who refuse school for positive reinforcement outside of school. The functional model of absenteeism thus covers anxiety- and non-anxiety-based cases and was designed to be relevant to school-age youth aged 5–17 years. The School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised is designed to identify the key maintaining variables of a child’s absenteeism (Kearney 2006; Haight et al. 2011).

Kearney and colleagues designed a prescriptive treatment approach whereby interventions are tailored to a child’s main reason for missing school. Youth who refuse school to avoid school-based stimuli that provoke negative affectivity receive child-based somatic control exercises and gradual reintegration to school. Youth who refuse school to escape aversive school-based social and/or evaluative situations receive child-based somatic control exercises, cognitive therapy, and gradual reintegration to school. A common form of evaluative anxiety in school-aged youth is test anxiety, which is modestly associated with greater absenteeism, lower grades, and general anxiety and depression (Caraway et al. 2003; Weems et al. 2010). Weems et al. (2009) found empirical support for a test anxiety treatment protocol that includes psychoeducation, somatic control exercises, a test anxiety exposure hierarchy and exposure tasks, and strategies to examine self-evaluation and build self-efficacy. Because test anxiety is prevalent and because this protocol was successfully delivered as part of a school’s counseling curriculum program, this protocol could also be considered a Tier 1 intervention.

Youth who refuse school to pursue attention from significant others receive parent-based contingency management that involves establishing set morning routines and providing attention-based consequences. Youth who refuse school to pursue tangible rewards outside of school receive family-based contingency contracting to boost incentives for attendance and disincentives for nonattendance, as well as increased parent supervision. This prescriptive treatment approach is empirically supported (Chorpita et al. 1996; Kearney 2002; Kearney et al. 2001; Kearney and Silverman 1990; Tolin et al. 2009). Prescriptive treatment, or intervention administered on the basis of a youth’s primary function of absenteeism, has also been found superior to nonprescriptive treatment, or intervention administered on the basis of a youth’s least influential function of absenteeism (Kearney and Silverman 1999).

Pina et al. (2009) conducted a meta-analysis of psychosocial (and largely cognitive-behavioral) interventions for absenteeism. Across group design studies, school attendance improved from 30 % at pre-test to 75 % at post-test (range at post-test: 47–100 %). Effect sizes were also calculated for continuous variables associated with absenteeism such as anxiety, fear, and depression. These effect sizes were quite variable (range −0.40–4.64), leading the authors to conclude that CBT may be effective for some domains (e.g., anxiety) more so than others (e.g., depression). More research is needed to include a wider swath of youths who refuse school, to refine interventions and detect mediators to maximize effectiveness, and to identify which youths are most likely to benefit from intervention (Tolin et al. 2009). Other Tier 2 interventions for problematic absenteeism may be better suited for these broader cases and are described next.

Student Engagement

Student engagement with school is a multifaceted construct that includes liking school, interest in schoolwork, willingness to learn, following rules, and attending school. Unstable pathways of student engagement relate strongly to school dropout (Janosz et al. 2008). Some programs have thus targeted student engagement to address emerging absenteeism. A prominent example is the Check and Connect model, which involves building relationships between school officials and family members, routine monitoring of absentee and other misbehaviors, and cognitive-behavioral problem-solving to develop social and coping skills and resolve obstacles to attendance (Sinclair et al. 2003). School-based monitors are also identified to meet individually with students and family members, check attendance and behavior referrals, and persistently facilitate efforts to promote student engagement. Check and Connect is highly useful for reducing tardiness and absenteeism (Anderson et al. 2004; Lehr et al. 2004). The model is used primarily for older youth but could be modified for youth at the elementary school level.

Peers and Mentoring

A related Tier 2 strategy is to utilize peer mentors who contact an absentee youth, encourage him to return to school, and offer to help remove obstacles to attendance. This strategy is likely most relevant for older youth. Peers can also be utilized as “buddies” with whom at-risk students can walk to school or serve as a companion/resource to students who frequently attempt to escape anxiety-provoking situations at school. Peer mentors may be especially helpful for youths with social skill deficits (White and Kelly 2010) and have been utilized to ease the transition process to a new school (Reid 2007). Peer mentoring programs may be particularly well-received if academic credit is provided and if the program is culturally sensitive (Crooks et al. 2010).

Peer mentors can supplement teacher mentoring that includes tutoring, advocacy, resilience building, and support (DeSocio et al. 2007). Teacher and community mentoring programs are effective for reducing absentee rates (effect size 0.19) (Dubois et al. 2011; Wheeler et al. 2010) and fit well in an RtI model. A mentoring program that includes weekly and positively viewed contact is likely best for older Tier 2 students with problematic absenteeism (Converse and Lignugaris-Kraft 2009).

Tier 2 Assessment

As mentioned, a key element of RtI is regular assessment, and attendance assessments at Tier 1 should occur at least twice per month. Attendance assessments during Tier 2 interventions, however, must be more frequent given the debilitating nature of existing absences and difficulty entering school. Tier 2 interventions must thus be accompanied by daily or weekly monitoring of attendance, especially in the early stages of intervention (Kearney and Albano 2007). Many youths at Tier 2 display various forms of absenteeism, including surreptitious behaviors such as premature departure from campus, so RtI team members should record actual percentage of time in school. Many youths at Tier 2 also display subtle behaviors such as dawdling in the morning before school, so RtI members should assess as well for home-based problems in the morning that may set the stage for absence or tardiness.

Other assessment methods are available for youths with problematic absenteeism and have been described at length elsewhere (Dube and Orpinas 2009). Examples include structured diagnostic interviews, questionnaires of internalizing and externalizing behavior, observations of school preparation and school entry behaviors, and review of academic records (Kearney et al. 2011). The purpose of these assessment methods is to better understand the contextual variables that impact a child’s absenteeism to determine appropriate educational and community-based programming and supports.

Students eligible for Tier 3 support include those who are chronically and severely absent from school. These students typically have (1) absences that have surpassed a legal limit for truancy (e.g., more than 10 absences in a semester), (2) sporadic attendance of classes if in school (e.g., 20 % or more of missed class time), and/or (3) frequent premature departures from school. Such problems have lasted at least 6 weeks (and likely longer) with severe impairments in academic and social functioning (McCluskey et al. 2004). Youths with absenteeism persistent enough to qualify for Tier 3 likely comprise about 5–10 % of students (Veenstra et al. 2010). Tier 3 interventions are described next.

Tier 3: Intensive Interventions for Chronically Absent Students

Tier 3 interventions are those directed toward students with complex or severe problems who require a concentrated approach and frequent progress monitoring. Tier 3 absenteeism can be thought of as near or past the “tipping point,” meaning that return to full-time attendance in a regular classroom setting is much less likely than in Tier 2. In addition, a student’s ability to pass the academic year is seriously compromised due to failing grades and lack of accrued credits (Rodriguez and Conchas 2009). Tier 3 interventions must thus include innovative, creative, and intense procedures to propel academic achievement, enhance parental involvement, and address comorbid problems. Developmental considerations must also be taken into account given that Tier 3 interventions have been designed primarily for adolescents. Tier 3 interventions for severe absenteeism include expanded Tier 2 interventions, alternative educational programs, legal strategies, and other ideas described next.

Expanded Tier 2 Interventions

Tier 3 interventions can include those described for Tier 2, but with substantial expansion. The severity and breadth of absenteeism at Tier 3 demands an intensive and wide-ranging approach that is best implemented by RtI team members and others (Kearney 2003; Reid 2003b). The RtI team could thus be expanded to include school-based mental health professionals with administrators and select teachers who review attendance and academic records, consult with clinicians and family members, and develop individualized education or 504 plans (Logan et al. 2008). These plans can allow for part-time attendance, modifications in class schedule and academic work, escorts to school and class, attendance journals, increased supervision, and daily feedback to parents regarding attendance and academic performance (Kearney and Bensaheb 2006; Schwartz et al. 2009).

Expansion also will likely require increased collaboration between RtI team members and community-based mental health professionals. Family therapy, parental skills training, social skills training, reduction of severe psychopathology, and crisis management are often necessary at Tier 3 (Kearney and Bates 2005). Family therapy can involve teaching parents to boost a child’s social and anxiety management skills to return to school, addressing family dynamics such as enmeshment, mobilizing a family’s social support network so others can help bring a youth to school, easing logistical problems such as transportation, implementing family-based communication and problem-solving training, expanding the intervention plan to address psychiatric problems in parents, and pursuing a slower pace of school reintegration (Carr 2009; Kearney and Bensaheb 2006).

Expanded parental skills training for younger children may focus on authoritative parenting that consists of high expectations of maturity, responsiveness, nurturance, and limit-setting (Eyberg et al. 2001). Parental skills training for older youth often includes a contingency management or contracting approach to enhance general communication, parent commands, disciplinary, and problem-solving skills (Kearney and Albano 2007). Intervention at Tier 3 may also require assuaging parents who have become deeply skeptical or suspicious of school officials or detached or confused about how to address their child’s absenteeism (Kearney 2008c).

Youth-based skills training may be needed to ease a child’s reintegration to school, reduce access to deviant peers, and increase access to helpful peers (Polansky et al. 2008). Peer refusal skills training can help a child decline offers to miss school (Kearney and Albano 2007). Youth-based intervention is often needed at Tier 3 to reduce extensive psychopathology such as depressive behavior, learning or oppositional defiant or conduct disorder, and substance abuse (Kearney and Albano 2004).

Tier 3 interventions must also address the urgency of a child’s academic situation; many cases at Tier 3 require extensive parent-RtI team collaboration to help a child acquire academic credit. This may involve summer or laboratory or online classes, part-time educational programs, and partial classroom attendance (e.g., 4 periods per day). Other options include switching schools or modifying class schedules (with independent study) and designing a curriculum more tailored to a youth’s academic interests and needs (Kearney 2008a). Home visits may be crucial at Tier 3. In addition, many families at Tier 3 are involved with public assistance or probation officers, caseworkers, and physicians, among others. Coordinating services by gathering representatives in one place such as school may improve consistency of care, reduce stigma and transportation problems for a family, and increase school attendance (Reid 2011).

Alternative Educational Programs

Alternative and self-contained educational programs that focus on part-time or supervised attendance as well as close mentoring of academic work are often necessary at Tier 3 (Lever et al. 2004). Alternative educational programs encompass a “school within a school” approach with small class size, project-based and cooperative learning, individualized and interdisciplinary instruction such as vocational or technical skills training, apprenticeships, and diverse instructional methods such as computers, direct experience, and service-learning activities. These programs may also include intense student mentoring, re-engagement with academic work, advocacy for highly absent students, and social networking (Rodriguez and Conchas 2009). Students are supervised closely, receive extended instruction for troublesome subjects, obtain specialized training that fits the business needs of a local community (e.g., finance, tourism), and earn equivalent college course credit. Career academies, for example, are often joint ventures between school officials and business owners who supply funding, curriculum input and review, and later employment internships and opportunities (Detgen and Alfeld 2011).

Alternative educational programs are often best for reducing dropout and enhancing attendance, academic achievement, and graduation rates compared to other Tier 3 methods (Klima et al. 2009). Successful programs involve an individualized approach that tailors intervention to the academic, health, social, and resource needs of students and their families to maintain investment in the educational process (Christenson and Thurlow 2004; Dynarski and Gleason 2002; Prevatt and Kelly 2003). Career academy graduates are more likely to be engaged in the academic process and to plan for college than controls (Orr et al. 2007). In addition, graduates of career academies have greater earning potential than control groups (Fleischman and Heppen 2009). Career academies could also be viewed as a Tier 1 approach but, because they have been developed in at-risk communities with very high absenteeism rates, are included here as a Tier 3 strategy.

A related Tier 3 strategy is alternative schools that involve completely separate learning facilities for students with histories of academic achievement difficulty, disruptive behavior problems, and nonattendance. Alternative schools may include a specific type of vocational training, a combination of home study and in-class or laboratory work, extended class time, summer coursework, work release, or afternoon or evening classes, among other nontraditional options. These schools emphasize academic remediation and credit accrual at a modified pace, individualized curricula and psychosocial services, and links to the business community. Alternative schools may be more educational or disciplinary in nature, though the former tends to be more effective for preventing school dropout (Dupper 2008).

Legal Strategies

Legal strategies to address severe absenteeism include truancy court or other avenues such as juvenile detention as well as police intervention to return students to campus (Desai et al. 2006; Hendricks et al. 2010). Laws to deter absenteeism via fines, deprived access to benefits or privileges, or increased compulsory education age have also been enacted but are criticized for ineffectiveness and high cost (Markussen and Sandberg 2011). Some laws paradoxically increase barriers to attendance by depriving youths of transportation, jailing parents, or mandating community-based service outside of the school setting (Mogulescu and Segal 2002; Zhang 2004). However, consistent enforcement of truancy policy within a system has been advocated as a successful strategy for curbing absenteeism (Bye et al. 2010). These policies may include more regular tracking of attendance, educating support staff about truancy policies, referral to juvenile justice agencies, and citations to parents for educational neglect (Jonson-Reid et al. 2007).

An alternative, hybrid model of legal intervention for absenteeism has evolved to emphasize flexible and multidisciplinary approaches. Fantuzzo et al. (2005) found that placing court proceedings within schools and linking families with caseworkers from service organizations improved attendance compared to a control group. Richtman (2007) referred absentee students and their parents to school-based meetings with a county attorney, school social worker or counselor, and probation officer to create a school attendance plan. The meetings also included referrals to social services agencies, substance use and mental health evaluations, and student or family counseling to address nonattendance. Truancy petitions were reduced 57.8 % over a 10-year period for youths under age 16 years. Shoenfelt and Huddleston (2006) evaluated a truancy court diversion program involving school personnel home visits to investigate factors related to absenteeism, meetings with a judge, parenting classes, tutoring, anger management, mentoring, and support groups. The diversion group evinced significant reductions in unexcused absences and improved grades compared to a control group.

Sutphen et al. (2010) reviewed 16 studies of truancy interventions that used group comparison or one-group pretest/posttest designs. Some interventions involved punitive approaches such as letters to parents, inclusion of law enforcement agencies, and reduced public assistance. Community-based interventions included social services and partnerships such as referral to mental health agencies, case management, and improved parenting. The most promising specific interventions involved student and family-based approaches that relied on contingency management, student support programs, and increased monitoring of attendance. Broader interventions effective for reducing severe absenteeism included school-based structural changes such as smaller and more independent academic units as well as alternative educational programs.

Other Tier 3 Interventions

Lyon and Cotler (2009) contended that school-based professionals could become involved in “exosystem” interventions that focus on social structures and policies to generally impact absenteeism. RtI teams could incorporate their services into local truancy court and truancy diversion programs, consult with juvenile justice and other agencies regarding extant legal procedures to reduce absenteeism, participate in research-based trials of systemic interventions that include school attendance as a key variable, develop multidisciplinary teams within their locale to boost availability and consistency of health-based services, and investigate interventions such as multisystemic therapy with a particular focus on crisis resolution, mobilization of family resources, and links to community resources. Multisystemic therapy involves intensive home-based strategies to improve family functioning and support, increase social and academic skills, address psychiatric disorders, reduce association with deviant peers, and minimize barriers to service delivery (Henggeler et al. 2009). Multisystemic therapy does effectively boost school attendance and is more cost effective than comparable juvenile offender programs (Aos et al. 2001; Henggeler et al. 1999).

Tier 3 Assessment

Regular assessment of attendance is necessary at Tier 1, frequent assessment of attendance is necessary at Tier 2, and ongoing, daily assessment of attendance is necessary at Tier 3. Such assessment is needed even after some attendance is established given the high rate of relapse in this group (Kearney and Albano 2007). Ongoing assessment at Tier 3 is often needed as well for academic deficiencies, psychopathology, and parent, family, and peer factors that impede attendance and cause setbacks. Tier 3 cases, for example, often involve comorbid depression, suicidality, disruptive behavior disorder, substance abuse, and medical problems (Egger et al. 2003; Kearney and Albano 2004; McShane et al. 2001). An enduring and comprehensive case study analysis for an individual student in Tier 3 that reviews educational, psychological, and legal status is highly recommended. As such, assessment at Tier 3 will likely require input from multiple agencies and evaluators such as educators, community therapists, and officers of the court.

Final Comments

Regular school attendance provides students with opportunities to develop their academic, language, social, and work-related skills. Unfortunately, rates of school absenteeism remain high. Problematic school absenteeism is a complicated issue requiring a sophisticated and nuanced approach. Such an approach would need to be integrative and pragmatic, focus on promoting regular school attendance universally, include all youth with absenteeism, and provide a common framework for collaborations with parents, community-based professionals, and others. The RtI model presented here is meant to do so and can accommodate youths with varying levels of school absenteeism. An RtI model also allows for clearer directions regarding assessment and intervention. The RtI model presented here is also meant as a heuristic for researchers and a general guideline for structuring responses to absenteeism for school-based professionals. The intricacy of problematic absenteeism, however, means that modifications will be necessary to more specifically tailor these guidelines to the demands of a given case and to a certain geographic location or school district.

Researchers, educational and mental health professionals, and parents must collaborate to develop this model and further enhance its utility for all youths with absenteeism. Several goals are critical in this regard. First, researchers and practitioners must strive for consensus in defining key terms related to school attendance and absenteeism. Such definitions should be based on empirical findings and tied to key student outcomes such as academic, social, and behavioral indicators as well as mental health and vocational outcomes. Second, schools must routinely monitor the percentage of students who attend school regularly (Tier 1), who are at-risk for chronic absenteeism (Tier 2), and who have chronic absenteeism (Tier 3). Attendance should be reviewed as a standing agenda item for a school or district leadership team that meets for data-based decision making. Attendance data could be viewed with other behavioral and academic information to provide a broader perspective on student needs and necessary interventions. Third, schools should routinely conduct a functional assessment to determine motivating conditions for absenteeism as a means to identify appropriate interventions. Finally, an increased focus on prevention in this area would produce a richer literature with respect to predictors of absenteeism and could make an RtI model more effective by reducing referrals to Tiers 2 and 3.

References

Adams, K. S., & Christenson, S. L. (2000). Trust and the family–school relationship examination of parent–teacher differences in elementary and secondary grades. Journal of School Psychology, 38, 477–497. doi:10.1016/S0022-4405(00)00048-0.

Anderson, A. R., Christenson, S. L., Sinclair, M. F., & Lehr, C. A. (2004). Check & Connect: The importance of relationships for promoting engagement with school. Journal of School Psychology, 42, 95–113. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2004.01.002.

Andresen, K., & McCarthy, A. M. (2009). A policy change statement for head lice management. Journal of School Nursing, 25, 407–416.

Aos, S., Phipps, P., Barnoski, R., & Lieb, R. (2001). The comparative costs and benefits of programs to reduce crime. Pullman, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy.

Balfanz, R., & Byrnes, V. (2012). Chronic absenteeism: Summarizing what we know from nationally available data. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University.

Barnes, A. C., & Harlacher, J. E. (2008). Clearing the confusion: Response-to-Intervention as a set of principles. Education and Treatment of Children, 31, 417–431.

Barnet, B., Arroyo, C., Devoe, M., & Duggan, A. K. (2004). Reduced school dropout rates among adolescent mothers receiving school-based prenatal care. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, 158, 262–268. doi:10.1001/archpedi.158.3.262.

Beane, A., Miller, T. W., & Spurling, R. (2008). The Bully Free Program: A profile for prevention in the school setting. In T. W. Miller (Ed.), School violence and primary prevention (pp. 391–405). New York: Springer.

Bekman, S., Aksu-Koc, A., & Erguvanli-Taylan, E. (2011). Effectiveness of an intervention program for six-year-olds: A summer-school model. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 19, 409–431. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2011.623508.

Bernstein, G. A., Borchardt, C. M., Perwein, A. R., Crosby, R. D., Kushner, M. G., Thuras, P. D., et al. (2000). Imipramine plus cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of school refusal. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 276–283. doi:10.1097/00004583-200003000-00008.

Bernstein, G. A., Massie, E. D., Thuras, P. D., Perwien, A. R., Borchardt, C. M., & Crosby, R. D. (1997). Somatic symptoms in anxious-depressed school refusers. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 661–668. doi:10.1097/00004583-199705000-00017.

Bradshaw, C. P., Koth, C. W., Thornton, L. A., & Leaf, P. J. (2009). Altering school climate through school-wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports: Findings from a group-randomized effectiveness trial. Prevention Science, 10, 100–115. doi:10.1007/s11121-008-0114-9.

Bridgeland, J. M., Dilulio, J. J., & Morison, K. B. (2006). The silent epidemic: Perspectives of high school dropouts. Seattle, WA: Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Brookmeyer, K. A., Fanti, K. A., & Henrich, G. C. (2006). Schools, parents, and youth violence: A multilevel, ecological analysis. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35, 504–514. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3504_2.

Broussard, C. A. (2003). Facilitating home–school partnerships for multiethnic families: School social workers collaborating for success. Children and Schools, 25, 211–222. doi:10.1093/cs/25.4.211.

Brown, M. B., & Bolen, L. M. (2008). The school-based health center as a resource for prevention and health promotion. Psychology in the Schools, 45, 28–38. doi:10.1002/pits.20276.

Bye, L., Alvarez, M. E., Haynes, J., & Sweigart, C. E. (2010). Truancy prevention and intervention: A practical guide. Oxford University Press: New York.

Calderon, J. M., Robles, R. R., Reyes, J. C., Matos, T. D., Negron, J. L., & Cruz, M. A. (2009). Predictors of school dropout among adolescents in Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico Health Sciences Journal, 28, 307–312.

Caraway, K., Tucker, C. M., Reinke, W. M., & Hall, C. (2003). Self-efficacy, goal orientation, and fear of failure as predictors of school engagement in high school students. Psychology in the Schools, 40, 417–427. doi:10.1002/pits.10092.

Carr, A. (2009). The effectiveness of family therapy and systemic interventions for child-focused problems. Journal of Family Therapy, 31, 3–45. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6427.2008.00451.x.

Cheung, C., & Lee, T. (2010). Improving social competence through character education. Evaluation and Program Planning, 33, 255–263. doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2009.08.006.

Chorpita, B. F., Albano, A. M., Heimberg, R. G., & Barlow, D. H. (1996). A systematic replication of the prescriptive treatment of school refusal behavior in a single subject. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 27, 281–290. doi:10.1016/S0005-7916(96)00023-7.

Christenson, S. L., & Thurlow, M. L. (2004). School dropouts: Prevention considerations, interventions, and challenges. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13, 36–39. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.01301010.x.

Clark, J. P., & Alvarez, M. E. (Eds.). (2010). Response to Intervention: A guide for school social workers. Oxford University Press: New York.

Converse, N., & Lignugaris-Kraft, B. (2009). Evaluation of a school-based mentoring program for at-risk middle school youth. Remedial and Special Education, 30, 33–46. doi:10.1177/0741932507314023.

Cooper, R., & Liou, D. D. (2007). The structure and culture of information pathways: Rethinking opportunity to learn in urban high schools during the ninth grade transition. High School Journal, 91, 43–56. doi:10.1353/hsj.2007.0020.

Crooks, C. V., Chiodo, D., Thomas, D., & Hughes, R. (2010). Strengths-based programming for First Nations Youth in Schools: Building engagement through healthy relationships and leadership skills. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 8, 160–173. doi:10.1007/s11469-009-9242-0.

Dake, J. A., Price, J. H., & Telljojann, S. K. (2003). The nature and extent of bullying at school. Journal of School Health, 73, 173–180. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2003.tb03599.x.

Desai, R. A., Goulet, J. L., Robbins, J., Chapman, J. F., Migdole, S. J., & Hoge, M. A. (2006). Mental health care in juvenile detention facilities: A review. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law, 34, 204–214.

DeSocio, J., VanCura, M., Nelson, L. A., Hewitt, G., Kitzman, H., & Cole, R. (2007). Engaging truant adolescents: Results from a multifaceted intervention pilot. Preventing School Failure, 51, 3–11. doi:10.3200/PSFL.51.3.3-11.

Detgen, A., & Alfeld, C. (2011). Replication of a career academy model: The Georgia Central Educational Center and four replication sites. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Southeast.

Dube, S. R., & Orpinas, P. (2009). Understanding excessive school absenteeism as school refusal behavior. Children and Schools, 31, 87–95. doi:10.1093/cs/31.2.87.

DuBois, D. L., Portillo, N., Rhodes, J. E., Silverthorn, N., & Valentine, J. C. (2011). How effective are mentoring programs for youth? A systematic assessment of the evidence. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 12, 57–91. doi:10.1177/1529100611414806.

Dupper, D. R. (2008). Guides for designing and establishing alternative school programs for dropout prevention. In C. Franklin, M. B. Harris, & P. Allen-Meares (Eds.), The school practitioner’s concise companion to preventing dropout and attendance problems (pp. 23–34). Oxford University Press: New York.

Dynarski, M., & Gleason, P. (2002). How can we help? What we have learned from recent federal dropout prevention evaluations. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 7, 43–69. doi:10.1207/S15327671ESPR0701_4.

Egger, H. L., Costello, E. J., & Angold, A. (2003). School refusal and psychiatric disorders: A community study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42, 797–807. doi:10.1097/01.CHI.0000046865.56865.79.

Ehiri, J. E., Hitchcock, L. I., Ejere, H. O. D., & Mytton, J. A. (2007). Primary prevention interventions for reducing school violence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD006347. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006347.

Eisen, A. R., & Engler, L. B. (2006). Helping your child overcome separation anxiety or school refusal: A step-by-step guide for parents. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.

EPE Research Center. (2008). Closing the graduation gap: Educational and economic conditions in America’s largest cities. Bethesda, MD: Editorial Projects in Education.

Epstein, J. L., & Sheldon, S. B. (2002). Present and accounted for: Improving student attendance through family and community involvement. Journal of Educational Research, 95, 308–318. doi:10.1080/00220670209596604.

Eyberg, S. M., Funderburk, B. W., Hembree-Kigin, T. L., McNeil, C. B., Querido, J. G., & Hood, K. K. (2001). Parent–child interaction therapy with behavior problem children: One and two year maintenance of treatment effects in the family. Child and Family Behavior Therapy, 23, 1–20. doi:10.1300/J019v23n04_01.

Faggiano, F., Vigna-Taglianti, F. D., Versino, E., Zambon, A., Borraccino, A., & Lemma, P. (2008). School-based prevention for illicit drug use: A systematic review. Preventive Medicine, 46, 385–396. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.11.012.

Fantuzzo, J., Grim, S., & Hazan, H. (2005). Project START: An evaluation of a community-wide school-based intervention to reduce truancy. Psychology in the Schools, 42, 657–667. doi:10.1002/pits.20103.

Fleischman, S., & Heppen, J. (2009). Improving low-performing high schools: Searching for evidence of promise. The Future of Children, 19, 105–133.

Fletcher, J. M., & Vaughn, S. (2009). Response to Intervention: Preventing and remediating academic difficulties. Child Development Perspectives, 3, 30–37. doi:10.1111/j.1750-8606.2008.00072.x.

Fox, L., Carta, J., Strain, P. S., Dunlap, G., & Hemmeter, M. L. (2010). Response to Intervention and the pyramid model. Infants and Young Children, 23, 3–13. doi:10.1097/IYC.0b013e3181c816e2.

Freudenberg, N., & Ruglis, J. (2007). Reframing school dropout as a public health issue. Preventing Chronic Disease, 4, 1–11.

Garcia-Gracia, M. (2008). Role of secondary schools in the face of student absenteeism: A study of schools in socially underprivileged areas. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 12, 263–280. doi:10.1080/13603110601103204.

Graczyk, P. A., Weissberg, R. P., Payton, J. W., Elias, M. J., Greenberg, M. T., & Zins, J. E. (2000). Criteria for evaluating the quality of school-based social and emotional learning programs. In R. Bar-on & J. D. A. Parker (Eds.), The handbook of emotional intelligence (pp. 391–410). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Gresham, F. M., Vance, M. J., Chenier, J., & Hunter, K. (2013). Assessment and treatment of deficits in social skills functioning and social anxiety in children engaging in school refusal behaviors. In D. McKay & E. A. Storch (Eds.), Handbook of assessing variants and complications in anxiety disorders (pp. 15–28). New York: Springer.

Grills-Taquechel, A. E., Norton, P., & Ollendick, T. H. (2010). A longitudinal evaluation of factors predicting anxiety during the transition to middle school. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 23, 493–513.

Guevara, J. P., Wolf, F. M., Grum, C. M., & Clark, N. M. (2003). Effects of educational interventions for self-management of asthma in children and adolescents: Systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal, 326, 1308–1309. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7402.1308.

Haight, C., Kearney, C. A., Hendron, M., & Schafer, R. (2011). Confirmatory analyses of the School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised: Replication and extension to a truancy sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 33, 196–204. doi:10.1007/s10862-011-9218-9.

Hawkin, L. S., Vincent, C. G., & Schumann, J. (2008). Response to Intervention for social behavior: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 16, 213–225. doi:10.1177/1063426608316018.

Hendricks, M. A., Sale, E. W., Evans, C. J., McKinley, L., & Carter, S. D. (2010). Evaluation of a truancy court intervention in four middle schools. Psychology in the Schools, 47, 173–183. doi:10.1002/pits.20462.

Henggeler, S. W., Rowland, M. D., Randall, J., Ward, D. M., Pickrel, S. G., Cunningham, P. B., et al. (1999). Home-based multisystemic therapy as an alternative to the hospitalization of youths in psychiatric crisis: Clinical outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38, 1331–1339. doi:10.1097/00004583-199911000-00006.

Henggeler, S. W., Schoenwald, S. K., Borduin, C. M., Rowland, M. D., & Cunningham, P. B. (2009). Multisystemic therapy for antisocial behavior in children and adolescents (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford.

Henry, K. L. (2007). Who’s skipping school: Characteristics of truants in 8th and 10th grade. Journal of School Health, 77, 29–35. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00159.x.

Henry, K. L., & Huizinga, D. H. (2007). Truancy’s effect on the onset of drug use among urban adolescents placed at risk. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40, 358.e9–358.e17. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.11.138.

Herzinger, C. V., & Campbell, J. M. (2007). Comparing functional assessment methodologies: A quantitative synthesis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 1430–1445. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0219-6.

Heyne, D., King, N. J., Tonge, B. J., Rollings, S., Young, D., Pritchard, M., et al. (2002). Evaluation of child therapy and caregiver training in the treatment of school refusal. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, 687–695. doi:10.1097/00004583-200206000-00008.

Heyne, D., & Rollings, S. (2002). School refusal. Malden, MA: BPS Blackwell.

Heyne, D., Sauter, F. M., Van Widenfelt, B. M., Vermeiren, R., & Westenberg, P. M. (2011). School refusal and anxiety in adolescence: Non-randomized trial of a developmentally sensitive cognitive behavioral therapy. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25, 870–878. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.04.006.

Hibbett, A., Fogelman, K., & Manor, O. (1990). Occupational outcomes of truancy. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 60, 23–36. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8279.1990.tb00919.x.

Hill, N. E., & Tyson, D. F. (2009). Parental involvement in middle school: A meta-analytic assessment of the strategies that promote achievement. Developmental Psychology, 45, 740–763. doi:10.1037/a0015362.

Hoagwood, K. E., Olin, S. S., Kerker, B. D., Kratochwill, T. R., Crowe, M., & Saka, N. (2007). Empirically based school interventions targeted at academic and mental health functioning. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 15, 66–92. doi:10.1177/10634266070150020301.

Ingul, J. M., Klockner, C. A., Silverman, W. K., & Nordahl, H. M. (2012). Adolescent school absenteeism: Modelling social and individual risk factors. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 17, 93–100. doi:10.1111/j.1475-3588.2011.00615.x.

Janosz, M., Archambault, I., Morizot, J., & Pagani, L. S. (2008). School engagement trajectories and their differential predictive relations to dropout. Journal of Social Issues, 64, 21–40. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.00546.x.

Jeynes, W. H. (2007). The relationship between parental involvement and urban secondary school student academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Urban Education, 42, 82–110. doi:10.1177/0042085906293818.

Jimerson, S. R., Anderson, G. E., & Whipple, A. D. (2002). Winning the battle and losing the war: Examining the relation between grade retention and dropping out of high school. Psychology in the Schools, 39, 441–457. doi:10.1002/pits.10046.

Jimerson, S. R., Burns, M. K., & VanDerHeyden, A. M. (2007). Response-to-Intervention at school: The science and practice of assessment and intervention. In S. R. Jimerson, M. K. Burns, & A. M. VanDerHeyden (Eds.), Handbook of Response to Intervention: The science and practice of assessment and intervention (pp. 3–9). New York: Springer.

Johnson, S. L. (2009). Improving the school environment to reduce school violence: A review of the literature. Journal of School Health, 79, 451–465. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00435.x.

Jonson-Reid, M., Kim, J., Barolak, M., Citerman, B., Laudel, C., Essma, A., et al. (2007). Maltreated children in schools: The interface of school social work and child welfare. Children and Schools, 29, 182–191. doi:10.1093/cs/29.3.182.

Kearney, C. A. (2001). School refusal behavior in youth: A functional approach to assessment and treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Kearney, C. A. (2002). Case study of the assessment and treatment of a youth with multifunction school refusal behavior. Clinical Case Studies, 1, 67–80. doi:10.1177/1534650102001001006.

Kearney, C. A. (2003). Bridging the gap among professionals who address youth with school absenteeism: Overview and suggestions for consensus. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 34, 57–65. doi:10.1037//0735-7028.34.1.57.

Kearney, C. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis of the School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised: Child and parent versions. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 28, 139–144. doi:10.1007/s10862-005-9005-6.

Kearney, C. A. (2007a). Forms and functions of school refusal behavior in youth: An empirical analysis of absenteeism severity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48, 53–61. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01634.x.

Kearney, C. A. (2007b). Getting your child to say “yes” to school: A guide for parents of youth with school refusal behavior. Oxford University Press: New York.

Kearney, C. A. (2008a). An interdisciplinary model of school absenteeism in youth to inform professional practice and public policy. Educational Psychology Review, 20, 257–282. doi:10.1007/s10648-008-9078-3.

Kearney, C. A. (2008b). School absenteeism and school refusal behavior in youth: A contemporary review. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 451–471. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.012.

Kearney, C. A. (2008c). Helping school refusing children and their parents: A guide for school-based professionals. Oxford University Press: New York.

Kearney, C. A., & Albano, A. M. (2004). The functional profiles of school refusal behavior: Diagnostic aspects. Behavior Modification, 28, 147–161. doi:10.1177/0145445503259263.

Kearney, C. A., & Albano, A. M. (2007). When children refuse school: A cognitive-behavioral therapy approach/Therapist guide. Oxford University Press: New York.

Kearney, C. A., & Bates, M. (2005). Addressing school refusal behavior: Suggestions for frontline professionals. Children and Schools, 27, 207–216. doi:10.1093/cs/27.4.207.

Kearney, C. A., & Bensaheb, A. (2006). School absenteeism and school refusal behavior: A review and suggestions for school-based health professionals. Journal of School Health, 76, 3–7. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2006.00060.x.

Kearney, C. A., Gauger, M., Schafer, R., & Day, T. (2011). Social and performance anxiety and oppositional and school refusal behavior in adolescents. In C. A. Alfano & D. C. Beidel (Eds.), Social anxiety disorder in adolescents and young adults: Translating developmental science into practice (pp. 125–141). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Kearney, C. A., LaSota, M. T., Lemos-Miller, A., & Vecchio, J. (2007). Parent training in the treatment of school refusal behavior. In J. M. Briesmeister & C. E. Schaefer (Eds.), Handbook of parent training: Helping parents prevent and solve problem behaviors (3rd ed., pp. 164–193). New York: Wiley.

Kearney, C. A., Pursell, C., & Alvarez, K. (2001). Treatment of school refusal behavior in children with mixed functional profiles. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 8, 3–11. doi:10.1016/S1077-7229(01)80037-7.

Kearney, C. A., & Silverman, W. K. (1990). A preliminary analysis of a functional model of assessment and treatment for school refusal behavior. Behavior Modification, 14, 344–360. doi:10.1177/01454455900143007.

Kearney, C. A., & Silverman, W. K. (1996). The evolution and reconciliation of taxonomic strategies for school refusal behavior. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 3, 339–354. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.1996.tb00087.x.

Kearney, C. A., & Silverman, W. K. (1999). Functionally-based prescriptive and nonprescriptive treatment for children and adolescents with school refusal behavior. Behavior Therapy, 30, 673–695. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(99)80032-X.