Abstract

The present study examined associations between narcissism (total, adaptive, and maladaptive), self-esteem, and externalizing and internalizing problems in 157 non-referred adolescents (aged 14 to 18). Consistent with previous research, narcissism was positively associated with self-reported delinquency, overt aggression, and relational aggression. Maladaptive narcissism showed unique positive associations with aggression and delinquency variables, while adaptive narcissism showed unique negative associations with anxiety symptoms. In general, self-esteem was negatively related to internalizing and externalizing problems. An interaction effect was observed for self-esteem and narcissism in predicting overt aggression. Specifically, at high levels of self-esteem narcissism was significantly associated with overt aggression, whereas it was not at low levels of self-esteem. The current results add to the growing body of research on the role of narcissism in the development of adjustment problems in youth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recent research indicates that narcissism, a personality construct characterized by a grandiose sense of self, a need for attention and admiration, hypersensitivity to the evaluation of others, and a sense of entitlement (American Psychiatric Association 1994), is associated with a host of social-psychological adjustment problems including aggression (Barry et al. 2009; Washburn et al. 2004), delinquency (Barry et al. 2007a), conduct problems (Barry et al. 2003), and internalizing symptoms (Washburn et al. 2004) in youth. Much of this work has been conducted with adolescents who show high rates of behavior problems or those considered at-risk for future adjustment issues (e.g., Barry et al. 2003, 2007b). However, it is critical to examine associations among narcissism and adjustment problems in non-referred school-based samples of youth in order to better inform interventions within school settings.

Researchers generally agree that narcissism is a multidimensional construct (Raskin and Terry 1988), with evidence for both adaptive (i.e., self-sufficiency, leadership, superiority) and maladaptive (i.e., exploitativeness, exhibitionism, entitlement) domains. In general, maladaptive narcissism shows stronger associations with negative outcome variables in both youth and adults (Barry et al. 2007a, 2009; Emmons 1984; Raskin and Terry 1988; Washburn et al. 2004). For example, in a sample of at-risk youth, Barry et al. (2007a) found that maladaptive but not adaptive narcissism predicted delinquency at three follow-up time points. In addition, Golmaryami and Barry (2010) recently found unique associations between maladaptive narcissism and peer-nominated relational aggression in a similar sample.

Overall, it seems clear that narcissism plays a role in the manifestation of aggressive and antisocial behavior in youth, with the maladaptive dimension of the construct showing some specificity for predicting problems. However, much less is known about the relationship between narcissism and internalizing problems in youth. The limited available evidence is mixed. In a study of male adolescent offenders, Calhoun et al. (2000) found that adaptive narcissism was negatively associated with anxiety, depression, and emotional problems, while maladaptive narcissism was not associated with these variables. Conversely, Washburn et al. (2004) studied students attending schools in a high-crime community and found that a maladaptive factor representing narcissistic exhibitionism was positively associated with depression and anxiety, but that an adaptive narcissism factor was not associated with internalizing symptoms. This was in contrast to their hypothesis that adaptive narcissism would show a negative association with internalizing problems similar to that found in Calhoun et al.’s study. Interestingly, neither study included a priori hypotheses regarding associations between internalizing problems and maladaptive narcissism, which creates difficulty in interpreting the inconsistent findings. Thus, analyses for the relationship between maladaptive and adaptive narcissism and anxiety are considered exploratory in the current study.

A final issue to consider when studying narcissism and adjustment problems is the potential role of self-esteem. Several studies have found interactions between narcissism and self-esteem in the manifestation of problems among youth (e.g., Barry et al. 2003; Golmaryami and Barry 2010; Washburn et al. 2004). For example, in a sample of 9 to 15 year old community youth selected to ensure high levels of oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder symptoms, Barry et al. (2003) found that the relation between narcissism and conduct problems was moderated by self-esteem. Specifically, those youth with high levels of narcissism and low levels of self-esteem exhibited the highest rates of conduct problem symptoms. Interestingly, Golmaryami and Barry found an interaction between self-esteem and narcissism in predicting relational aggression, where narcissism was particularly related to relational aggression for those with high self-esteem. Finally, Washburn et al. (2004) found an interaction between exploitative (maladaptive) narcissism and self-esteem in predicting depression and anxiety symptoms, wherein self-esteem was negatively associated with internalizing problems only in youth with low levels of exploitative narcissism. Individuals with higher exploitative narcissism scores showed higher levels of internalizing symptoms regardless of self-esteem. Taken together, these findings seem to suggest that narcissism and self-esteem both play a role in the manifestation of adjustment problems in youth. However, due to the mixed nature of these findings it is not clear whether narcissistic youth show more problems at high or low levels of self-esteem. Further, it is not clear whether the associations found between narcissism, self-esteem, and adjustment problems are generalizable to a non-referred, school-based sample of adolescents.

Given previous findings, the current study had several purposes. First, we sought to examine the roles of narcissism and self-esteem in predicting behavioral problems (aggression and delinquency) in a non-referred school-based sample of adolescents. Student bullying/aggression is one of the most frequently reported discipline problems in public and private schools internationally (Borntrager et al. 2009; U.S. Department of Education 2006) and has damaging effects on peer relationships and academic outcomes for both aggressors and victims (Haynie et al. 2001). Thus, it is critical to examine potential predictors of such behavior in school-based samples in order to inform intervention efforts within schools. Overall, we expected a positive association between narcissism and the aggression and delinquency variables, and negative association between self-esteem and these variables. Further, based on results from previous self-report studies (Barry et al. 2003, 2007b), we expected that at low levels of self-esteem, narcissism would be a better predictor of overt aggression and delinquency than at high levels of self-esteem. We also attempted to replicate Golmaryami and Barry’s (2010) finding that narcissism was related to peer-nominated relational aggression at high levels of self-esteem using a self-report measure of relational aggression. Second, we sought to expand upon the scarce literature on narcissism and internalizing problems in youth by examining the relationship between narcissism, self-esteem, and anxiety symptoms. This study also sought to examine the differential associations between adaptive and maladaptive narcissism and adjustment problems in youth, with the expectation that maladaptive narcissism would show stronger associations with self-reported delinquency and aggression than adaptive narcissism. Exploratory analyses were also conducted to determine whether anxiety was significantly associated with the maladaptive and adaptive components of narcissism.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from two public schools in the southern United States. Parental consent forms were distributed to students enrolled in 9th to 12th grade. Approximately 317 parental consent forms were returned allowing those students to participate in the study. Of the 317 students with signed consent forms, roughly 140 students were absent, did not show up, or were preparing for standardized testing during the three data collection days. The initial study sample was thus composed of 177 participants. However, 20 (11%) of cases were missing data on more than half of the data points on the main measures of interest. A Missing Values Analysis (MVA) was conducted in SPSS to examine patterns of missing values. Based on this analysis it was determined that data for these cases were missing completely at random, and thus they were deleted from the final analyses. The resulting sample consisted of 157 youth (62% girls) ranging in age from 14 to 18 years (M = 14.99; SD = 1.10). The self-reported ethnicity of the sample was 63% Caucasian, 30% African American, and 7% other.

Measures

Narcissistic Personality Inventory for Children (NPIC)

The NPIC (Barry et al. 2003) is a downward age extension of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI) that has been used in past research with adults (Raskin and Hall 1979). The NPIC is a 40-item forced-choice self-report inventory. Each item consists of a pair of statements, and the respondent must choose which statement is more like him- or herself (e.g., “I am good at getting other people to do what I want” or “I am not good at getting other people to do what I want”). Additional response points (i.e., asking if the chosen statement is “sort of true” or “really true”) were added for the youth measure. The NPI was developed primarily for use in nonclinical populations of adults (Raskin and Hall 1979), and its construct validity has been supported in numerous previous studies (e.g., Emmons 1984; Raskin and Terry 1988; Watson and Biderman 1993). Previous studies show that the NPIC consists of items that assess both adaptive and maladaptive narcissism (Barry et al. 2003, 2007a). Internal consistency has been shown to be good for the overall narcissism scale (Barry et al. 2003). Further, previous research has shown that youth who score high on the NPIC are likely to exhibit conduct problems, aggression (Barry et al. 2003), and later delinquent behavior (Barry et al. 2007a). The total NPIC score had good internal consistency in the current study (Cronbach’s alpha = .87). Internal consistency was relatively lower for the maladaptive (Cronbach’s alpha = .67) and adaptive composites (Cronbach’s alpha = .60).

Peer Conflict Scale (PCS)

The PCS (Marsee and Frick 2007) is a 40-item self-report measure including 20 items assessing overt aggression (both reactive overt: “When someone hurts me, I end up getting into a fight” and proactive overt: “I start fights to get what I want”) and 20 items assessing relational aggression (both reactive relational: “If others make me mad, I tell their secrets” and proactive relational: “I gossip about others to become popular”). Items are rated on a 4-point scale (0 = “not at all true,” 1 = “somewhat true,” 2 = “very true,” and 3 = “definitely true”) and scores are calculated by summing the items to create either total reactive, total proactive, total overt, or total relational scales (range 0–60). Research supports the distinction between the reactive and proactive scales as well as the relational and overt scales, in that they show associations with expected emotional and cognitive correlates (Marsee and Frick 2007) as well as narcissism and delinquency (Barry et al. 2007b) in adolescent samples. For the purposes of the current study, scores for total relational and total overt aggression were used. Previous research supports the internal consistency of these scales in at-risk (Barry et al. 2007b) and detained adolescents (Marsee and Frick 2007). The scales demonstrated good internal consistency in the current study (Cronbach’s alpha: total relational = .87; total overt = .88).

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE)

The RSE (Rosenberg 1965) is a 10-item self-report questionnaire that asks participants to indicate on a 4-point scale how much they agree or disagree with statements about their self-worth (0 = strongly agree, 1 = agree, 2 = disagree, 3 = strongly disagree). The statements contain both positive and negative evaluations (e.g., “I take a positive attitude toward myself,” “At times I think I am no good at all”). The possible range of RSE scores is 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating higher levels of self-esteem. The RSE has demonstrated good internal consistency in past research with adolescents and has shown associations with narcissism and externalizing problems (Barry et al. 2009; Donnellan et al. 2005). The internal consistency of the RSE was good (Cronbach’s alpha = .83) in the current study.

Self-Report of Delinquency (SRD)

The SRD (Elliott and Ageton 1980) is a 46-item self-report measure that assesses 36 illegal juvenile acts. It was developed from a list of offenses reported in the Uniform Crime Report with a juvenile base rate of greater than 1% (Elliott and Huizinga 1984). For each delinquent act, the youth is asked (a) whether or not he or she has ever engaged in the particular problem behaviors, (b) the number of times he or she engaged in the behavior, (c) the age in which he or she first engaged the behavior, and (d) whether or not he or she has friends who have engaged in the behavior. The remaining 10 items assess the arrest history of the youth’s immediate family. Krueger et al. (1994) reported significant correlations between the SRD and informant report of delinquency (i.e., friends or family who reported on youth’s antisocial behavior during the past 12 months) (r = .48, p < .01), police contacts (r = .42, p < .01), and court convictions (r = .36, p < .01). For the purposes of the current study, a total delinquency score was created by summing the number of delinquent acts (with a possible range of 0–19) committed while omitting questions relating to sexual behavior, nonviolent delinquency, drug use, and family history items (Cronbach’s alpha = .83).

The Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scales (RCADS)

The RCADS (Spence 1997 ) is a 47-item instrument that assesses anxiety and depression symptoms based on DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association 1994). Respondents are asked to circle an answer corresponding to how often each symptom happens to them on a 4-point scale (i.e., “Never,” “Sometimes,” “Often,” or “Always”). The RCADS is an adaptation of the Spence Anxiety Scales (Spence 1997). The scale has good internal consistency (coefficient alpha = .93) and cross-informant (r = .27) and convergent validity (r = .60) in previous research (Weems et al. 2007). For the purposes of the current study, a 24-item anxiety scale was used, with items measuring depression, separation anxiety, and obsessive–compulsive disorder omitted (Cronbach’s alpha = .94).

Procedures

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the university prior to data collection. Participants were assessed in groups during their free period at school. Prior to beginning the questionnaire packet, the procedures of the study were explained to the students and they were asked if they would like to participate. It was also explained to the students that they could withdraw at any time. Participants were asked to sign an assent form on the front page of the questionnaire packet, then to remove the page and use it to cover their answers as they completed the packet.

As part of a larger battery, participants completed the Peer Conflict Scale (Marsee and Frick 2007), the Narcissistic Personality Inventory for Children (Barry et al. 2003), the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg 1965), the Self-Report of Delinquency scale (Elliott and Ageton 1980), and the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression scale (Spence 1997). Instructions for completing the questionnaires were read aloud to the participants. The assessment sessions lasted from 60 to 90 min. Students completed questionnaire packets in one session, and data were collected over 3 separate sessions between December, 2006 and March, 2007. After completing the questionnaire packets, each student received a coupon redeemable at a fast food restaurant for a free snack.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations for the main study variables are provided in Table 1. Males (M = 4.49, SD = 4.23) reported significantly higher levels of delinquency than females (M = 3.16, SD = 2.87), t(90.1) = 2.14, p < .05, whereas females (M = 28.00, SD = 15.58) reported significantly higher levels of anxiety than males (M = 22.16, SD = 13.51), t(135.88) = −2.48, p < .05. Narcissism was positively correlated with self-esteem (r = .35), delinquency (r = .30), overt aggression (r = .28), and relational aggression (r = .37), all ps < .001. Self-esteem was negatively correlated with delinquency (r = −.20, p < .01), and anxiety (r = −.46, p < .001). Both maladaptive and adaptive narcissism were positively associated with delinquency (r = .38, p < .001 and, r = .22, p < .01, respectively), overt aggression (r = .35, p < .001 and, r = .23, p < .01, respectively), relational aggression (r = .43, p < .001 and, r = .23, p < .01, respectively), and self-esteem (r = .17, p < .05 and, r = .35, p < .001, respectively). Narcissism (total, maladaptive, and adaptive) was not significantly correlated with anxiety at the bivariate level (see Table 1).

Partial correlations were conducted on the adaptive and maladaptive composites of narcissism to determine whether they showed unique associations with the dependent variables. After controlling for maladaptive narcissism, the associations between adaptive narcissism and delinquency (pr = −.07), overt aggression (pr = −.01) and relational aggression (pr = −.09) were no longer significant. However, the association between maladaptive narcissism and delinquency (pr = .33, p < .01), overt aggression (pr = .27, p < .01) and relational aggression (pr = .38, p < .01), were still significant after controlling for adaptive narcissism. The pattern of results was opposite for anxiety: after controlling for maladaptive narcissism, anxiety was significantly negatively associated with adaptive narcissism (r = −.18, p < .05), but after controlling for adaptive narcissism, anxiety did not remain significantly associated with maladaptive narcissism.

A series of regression analyses were conducted to examine the relationships between narcissism, self-esteem, and the externalizing and internalizing variables. Regression analyses were conducted separately for the total narcissism scale, the maladaptive scale, and the adaptive scale (see Table 2). To avoid collinearity and to create the interaction terms, narcissism (total, maladaptive, and adaptive scales) and self-esteem were centered by subtracting the means of the two variables from their respective scores (Jaccard and Turrisi 2003). The centered variables were then multiplied with each other to create the interaction term. Narcissism variables and self-esteem were entered on the first step and their interaction term was entered on the second step with the delinquency, aggression, and anxiety variables as the criterion variables.

There was a significant positive main effect for total narcissism predicting delinquency (β = .42, t = 5.27, p < .001), overt aggression (β = .32, t = 4.19, p < .001), and relational aggression (β = .41, t = 5.18, p < .001) and a significant negative main effect for self-esteem predicting delinquency (β = −.33, t = −4.16, p < .001), overt aggression (β = −.24, t = −3.15, p < .01), relational aggression (β = −.18, t = −2.34, p < .05), and anxiety (β = −.49, t = −6.50, p < .001). In addition, the interaction for narcissism and self-esteem in predicting overt aggression was significant (β = .30, t = 4.23, p < .001). There was a trend toward a significant interaction for narcissism and self-esteem in predicting relational aggression (β = .14, t = 1.90, p = .060) and anxiety (β = .14, t = 1.93, p = .056).

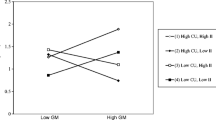

To further investigate the significant interaction of narcissism and self-esteem in predicting overt aggression and to examine the pattern of associations for the nonsignificant interactions of narcissism and self-esteem in predicting relational aggression and anxiety, post hoc probing, as suggested by Holmbeck (2002) was conducted. Two new conditional moderator variables were created, high self-esteem (1 SD above the mean) and low self-esteem (1 SD below the mean). Two new interaction terms that incorporated these conditional variables were also created, high self-esteem by narcissism and low self-esteem by narcissism. Finally, six additional regression analyses were conducted, three with high self-esteem, narcissism, and their interaction as predictors of the three dependent variables and three with low self-esteem, narcissism, and their interaction as predictors. Results indicated that at high self-esteem narcissism was significantly associated with overt aggression (β = .60, t = 6.50, p < .001) but not at low self-esteem (β = .04, t = 0.35, p = .728). Though the initial narcissism by self-esteem interactions were not significant for relational aggression and anxiety, the pattern of results indicated that narcissism was associated with relational aggression at both high (β = .54, t = 5.63, p < .001) and low (β = .28, t = 2.46, p < .05) self-esteem, and that narcissism was associated with anxiety at high self-esteem (β = .20, t = 2.19, p < .05) but not low (β = −.05, t = −0.50, p = .619).

The regression analyses conducted using the maladaptive and adaptive composites showed a similar pattern of results as those using the total narcissism scale (see Table 2). Specifically, there were significant positive main effects for both maladaptive and adaptive narcissism in predicting delinquency, overt aggression, and relational aggression. There were significant negative main effects for self-esteem in predicting delinquency, overt aggression, and anxiety, and though not significant, the betas for self-esteem in predicting relational aggression were moderate and in the expected direction (see Table 2). There were significant maladaptive narcissism by self-esteem interactions in predicting both overt and relational aggression. When decomposed in the manner described above, the pattern of associations was similar to those using the total narcissism score (i.e., at high self-esteem, β = .61, t = 6.98, p < .001, but not low, β = .00, t = 0.02, p = .987, maladaptive narcissism was significantly associated with overt aggression; at both high, β = .56, t = 6.21, p < .001, and low levels of self-esteem, β = .26, t = 2.27, p < .05, maladaptive narcissism was significantly associated with relational aggression). There was a significant adaptive narcissism by self-esteem interaction in predicting overt aggression (Table 2), with adaptive narcissism predicting overt aggression at high self-esteem (β = .57, t = 5.44, p < .001) but not at low self-esteem (β = .10, t = 1.04, p = .298). Finally, there was a significant adaptive narcissism by self-esteem interaction in predicting anxiety (Table 2), where adaptive narcissism was positively (but not significantly) associated with anxiety at high self-esteem (β = .18, t = 1.75, p = .082) but not at low (β = −.07, t = −0.78, p = .439). The pattern of results was similar for the nonsignificant interaction for maladaptive narcissism and self-esteem (see Table 2), where maladaptive narcissism was associated with anxiety at high self-esteem (β = .18, t = 2.02, p < .05) but not at low (β = −.06, t = −0.57, p = .572).

Based on previous research (Barry et al. 2003, 2007b), gender was entered into the regression models to examine whether it moderated the associations between narcissism (total, maladaptive, adaptive) and the dependent variables. Analyses for total narcissism resulted in a significant negative main effect for gender in predicting delinquency (β = −.19, t = −2.52, p < .05) and a significant positive main effect for gender in predicting anxiety (β = .16, t = 2.16, p < .05) and no significant gender interactions. For the maladaptive and adaptive analyses, results showed no significant main effects for gender and no significant gender interactions.

Discussion

The results of the present study support the hypothesis that narcissism is positively associated with delinquency and aggression (both overt and relational) in non-referred adolescent youth. These findings replicate the results of previous research (Barry et al. 2009, 2007b) with at-risk adolescents and suggest that narcissism may be an important variable to consider in the manifestation of problem behavior not only in high-risk youth, but also in non-referred, school-based samples of youth.

The current results are also consistent with past research showing that the maladaptive dimensions of narcissism (i.e., exploitativeness, exhibitionism, entitlement) show stronger associations with externalizing problems than the adaptive components of narcissism (i.e., self-sufficiency, leadership, superiority) (Barry et al. 2007a; Washburn et al. 2004). In particular, this study found that maladaptive narcissism was positively associated with self-reported delinquency, overt aggression, and relational aggression, even after controlling for adaptive narcissism. These findings suggest that maladaptive narcissism is related to a wide range of antisocial and aggressive behaviors among youth and provide further support for the multidimensional nature of the narcissism construct. Further, the current results support the generalizability of these associations to a non-referred school-based sample of adolescents.

Contrary to previous research in an inner-city school sample (Washburn et al. 2004), anxiety was not significantly associated with maladaptive narcissism in this study. This finding makes sense when considering that many youth who experience anxiety problems are also socially withdrawn (Rubin et al. 2009), and thus may spend much of their time avoiding social activities within their peer groups. Thus, it seems less likely that anxious youth would endorse items related to exhibitionism (e.g., “I like to be the center of attention”), exploitativeness (e.g., “I can make anybody believe anything I want them to”), or entitlement (e.g., “I expect to get a lot from other people”), as these characteristics center on involvement in and/or manipulation of a social group. More research is needed to determine whether this is the case or whether, as Washburn et al. (2004) proposed, certain maladaptive narcissistic strategies fulfill a need for attention while at the same time creating embarrassment (and hence, increases in internalizing symptoms).

Interestingly, after controlling for maladaptive narcissism, self-reported anxiety symptoms in this study were significantly negatively associated with adaptive narcissism. This finding is consistent with Calhoun et al. (2000), who found that adaptive narcissism, specifically the Authority/Superiority component, was significantly negatively associated with self-reported anxiety and depression symptoms in a sample of male adolescent offenders. These findings fit with the idea that youth with higher levels of adaptive narcissism (e.g., leadership, self-sufficiency) may show greater social competence with peers, which has been linked to lower levels of anxiety (Obradović et al. 2010). While to our knowledge research has not examined associations between adaptive narcissism and social competence in youth, adult research has shown that some of the adaptive aspects of narcissism (e.g., authority, self-sufficiency) are associated with positive social characteristics such as sociability and self-confidence (Raskin and Terry 1988).

One goal of this study was to examine the role of self-esteem in the association between narcissism and adjustment problems (i.e., self-reported delinquency, aggressive behavior, and anxiety) in a non-referred, non-selected sample of high school students. Our results both replicate and extend previous research. Generally consistent with previous research (Barry et al. 2009, 2007b; Donnellan et al. 2005), we found significant main effects for narcissism in predicting delinquency, relational aggression, and overt aggression, as well as significant negative main effects for self-esteem in the prediction of these variables (see Table 2). Further, this analysis resulted in a significant interaction effect for narcissism and self-esteem in predicting overt aggression.

Contrary to our hypothesis and to previous research (Barry et al. 2003, 2007b), our analysis of the significant interaction revealed that among youth with high self-esteem, narcissism was significantly associated with overt aggression, whereas it was not associated with aggression among youth with low self-esteem. This pattern was the same for analyses using the maladaptive and adaptive composites as predictors. Overall these results suggest that high self-esteem may be influential in narcissistic youths’ engagement in aggressive acts and are in contrast to findings suggesting that it is the combination of low self-esteem and narcissism that predicts negative outcomes (Barry et al. 2003). This discrepancy may be due to a number of differences between the current study and Barry et al.’s study. First, Barry et al.’s sample was selected to ensure high rates of disruptive behavior problems, whereas the current sample consisted of non-selected high school students. Previous longitudinal research supports a developmental link between low self-esteem and later antisocial behavior in youth as reported by parents and teachers (Donnellan et al. 2005). Thus, it may be that high-risk samples of youth (such as Barry et al.’s sample) have overall lower self-esteem to begin with.

Levels of self-esteem may also have been differentially related to the outcome measures used in the two studies (conduct problem symptoms, Barry et al. 2003; overt aggression towards peers, current study). That is, low self-esteem may be a better predictor of severe antisocial and disruptive behavior that includes both covert (e.g., conning others, stealing) and overt (e.g., cruelty to people and animals) acts, whereas high self-esteem may show stronger associations with peer-related physical and verbal aggression, especially when combined with the need for approval from and sensitivity to the opinions of others (i.e., narcissism). Although the interaction between narcissism and self-esteem in the current study was not significant in predicting delinquency, the correlational results seem to support this idea, as low self-esteem was significantly correlated with delinquent behavior but not peer-related aggressive behavior. It is possible that these differential associations represent relatively distinct developmental pathways to problem behavior, such that narcissistic youth with low self-esteem show greater severity and variety of behavioral problems compared to narcissistic youth with high self-esteem.

Though the interaction did not reach statistical significance and thus should be interpreted with caution, the pattern of results for relational aggression showed that at both high and low levels of self-esteem, narcissism (both total and maladaptive) was associated with relational aggression. This is partially consistent with Golmaryami and Barry (2010), who found that narcissism was related to peer-nominated relational aggression for at-risk youth with high self-esteem. However, our findings suggest that narcissistic youth may engage in relational aggression regardless of their level of self-esteem. Given the socially manipulative aspects of relational aggression and the fact that many times it can be carried out without confrontation (Lagerspetz et al. 1988), it makes sense that narcissistic youth may choose to engage in this type of behavior as a means of harming another while attempting to protect their own status within the peer group. Further, different mechanisms may be driving the relationally aggressive behavior of narcissistic youth with high versus low self-esteem. As Golmaryami and Barry suggested, some youth may perceive the manipulation of peers as rewarding and thus the successful use of this type of behavior may increase self-esteem (or vice versa). On the other hand, youth with low self-esteem may feel particularly vulnerable within the social group and may utilize relational aggression because they perceive it as less likely to result in retaliation.

Similar to analyses for aggression, the pattern of results for anxiety showed that at high levels of self-esteem but not low, narcissism (total and maladaptive) was associated with anxiety symptoms. This finding is interesting given the lack of association between total and maladaptive narcissism and anxiety at the bivariate level and suggests that the association between these variables may differ as a function of self-esteem. As Washburn et al. (2004) suggest, narcissism may essentially be “washing out” the protective effect of high self-esteem on the manifestation of internalizing problems. However, given the lack of significance and the exploratory nature of these analyses, these findings should be interpreted with caution. Additional research is necessary to determine whether self-esteem actually moderates the association between narcissism and anxiety.

The current results should be considered in the context of several study limitations. First, the rate of participation in the study was relatively low and could affect the generalizability of the results. Also, the cross-sectional nature of the data prevents causal or temporal interpretations regarding the associations among narcissism, self-esteem, and adjustment variables. While we found that at high self-esteem, narcissism in youth was associated with acts of physical and verbal aggression (and to some extent relational aggression) against peers, the current correlational data prevent us from establishing a causal chain of events. It is certainly plausible that some youth in our study may have shown higher levels of aggression towards peers to begin with, and the rate of success for their aggressive acts may have served to reinforce feelings of superiority over others, thus increasing their self-esteem. Future research should examine these questions longitudinally to determine the sequential relations among these variables.

All variables in the current study were assessed via self-report, which may have artificially inflated associations among variables due to shared method variance. However, due to the intrapersonal nature of the narcissism and self-esteem constructs, it is thought that self-report may be the best method for accurately assessing them. Nevertheless, it is important for future studies to examine these questions using multiple informant reports, especially for the aggression and delinquency outcome variables. For example, results may be greatly enhanced with the addition of parent and teacher reports of aggression and police reports detailing delinquent activity.

Consistent with previous research (Barry et al. 2007b), an additional limitation to the current study was the relatively low internal consistency estimates for the maladaptive and adaptive components of the NPIC. Despite this low internal consistency, the maladaptive and adaptive narcissism scales are associated with theoretically important differential correlates in past research (e.g., Barry et al. 2007a, b) and in the current study. However, further refinement of the NPIC maladaptive and adaptive composite scales may be needed in order to reliably assess these components.

Despite these limitations, the results from the current study add to the growing body of research on the role of narcissism in the manifestation of adjustment problems in youth. Our results suggest that the measurement of narcissism may be useful in understanding both externalizing and internalizing symptoms in youth, with the maladaptive and adaptive composites showing some specificity in predicting outcomes. While our current results cannot resolve the question of whether low self-esteem or high self-esteem (in combination with narcissism) is a better predictor of negative outcomes, our findings do support previous researchers’ assertions that narcissism and self-esteem are best considered as separate constructs (Donnellan et al. 2005), as they show differential associations with adjustment problems. When considering the interaction between the two constructs, results showed that at high levels of self-esteem narcissism was associated with peer-related aggression. As suggested by Barry et al. (2007b), this may be due to developmental shifts in the relation between narcissism and self-esteem from childhood to adolescence, such that positive associations between the two become evident as youth get older and begin to internalize positive self-views. Or, as mentioned previously, differential relations between narcissism, self-esteem, and negative behavior may represent unique developmental trajectories. Answering these questions will require longitudinal analysis of traits and behavior patterns beginning in early childhood and spanning into late adolescence. Research to this end has the potential to significantly add to our understanding of the development and manifestation of externalizing and internalizing problems in youth.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Barry, C. T., Frick, P. J., Adler, K. K., & Grafeman, S. J. (2007a). The predictive utility of narcissism among children and adolescents: Evidence for a distinction between adaptive and maladaptive narcissism. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16, 508–521.

Barry, C. T., Frick, P. J., & Killian, A. L. (2003). The relation of narcissism and self-esteem to conduct problems in children: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Clinical and Child and Adolescent Psychology, 32, 139–152.

Barry, C. T., Grafeman, S. J., Adler, K. K., & Pickard, J. D. (2007b). The relations among narcissism, self-esteem, and delinquency in a sample of at-risk adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 30, 933–942.

Barry, C. T., Pickard, J. D., & Ansel, L. L. (2009). The associations of adolescent invulnerability and narcissism with problem behaviors. Personality and Individual Differences, 47, 577–582.

Borntrager, C., Davis, J. L., Bernstein, A., & Gorman, H. (2009). A cross-national perspective on bullying. Child & Youth Care Forum, 38, 121–134. doi:10.1007/s10566-009-9071-0.

Calhoun, G. B., Glaser, B. A., Stefurak, T., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2000). Preliminary validation of the narcissistic personality inventory-juvenile offender. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 44, 564–580.

Donnellan, M. B., Trzesniewski, K. H., Robins, R. W., Moffitt, T. E., & Caspi, A. (2005). Low self-esteem is related to aggression, antisocial behavior, and delinquency. Psychological Science, 16, 328–335.

Elliott, D. S., & Ageton, S. S. (1980). Reconciling race and class differences in self-reported and official estimates of delinquency. American Sociological Review, 45, 95–110.

Elliott, D. S., & Huizinga, D. (1984). The relationship between delinquent behavior and ADM problems. Boulder, CO: Behavioral Research Institute.

Emmons, R. A. (1984). Factor analysis and construct validation of the narcissistic personality inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 48, 291–300.

Golmaryami, F. N., & Barry, C. T. (2010). The associations of self-reported and peer-reported relational aggression with narcissism and self-esteem among adolescents in a residential setting. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 39, 128–133.

Haynie, D. L., Nansel, T., Eitel, P., Crump, A. D., Saylor, K., Yu, K., et al. (2001). Bullies, victims, and bully/victims: Distinct groups of at-risk youth. Journal of Early Adolescence, 21, 29–49.

Holmbeck, G. N. (2002). Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and meditational effects in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 27, 87–96.

Jaccard, J., & Turrisi, R. (2003). Interaction effects in multiple regression. Newbury Park: Sage.

Krueger, R. F., Schmutte, P. S., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., Campbell, K., & Silva, P. A. (1994). Personality traits are linked to crime among men and women: Evidence from a birth cohort. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103, 328–338.

Lagerspetz, K. M. J., Björkqvist, K., & Peltonen, T. (1988). Is indirect aggression typical of females? Gender differences in aggressiveness in 11-to 12-year-old children. Aggressive Behavior, 14, 403–414.

Marsee, M. A., & Frick, P. J. (2007). Exploring the cognitive and emotional correlates to proactive and reactive aggression in a sample of detained girls. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35, 969–981.

Obradović, J., Burt, K. B., & Masten, A. S. (2010). Testing a dual cascade model linking competence and symptoms over 20 years from childhood to adulthood. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 39, 90–102.

Raskin, R. N., & Hall, C. S. (1979). A narcissistic personality inventory. Psychological Reports, 45, 590.

Raskin, R. N., & Terry, H. (1988). A principal components analysis of the narcissistic personality inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 890–902.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rubin, K. H., Coplan, R. J., & Bowker, J. C. (2009). Social withdrawal in childhood. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 141–171.

Spence, S. H. (1997). Structure of anxiety symptoms among children: A confirmatory factor analytic study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106, 280–297.

U.S. Department of Education. (2006). National Center for Education Statistics: 2005–06 School Survey on Crime and Safety (SSOCS). Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/.

Washburn, J. J., McMahon, S. D., King, C. A., Reinecke, M. A., & Silver, C. (2004). Narcissistic features in young adolescents: Relations to aggression and internalizing symptoms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 33, 247–260.

Watson, P. J., & Biderman, M. D. (1993). Narcissistic personality inventory factors, splitting, and self-consciousness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 61, 41–57.

Weems, C. F., Costa, N. M., Watts, S. E., Taylor, L. K., & Cannon, M. F. (2007). Cognitive errors, anxiety sensitivity and anxiety control beliefs: Their unique and specific associations with childhood anxiety symptoms. Behavior Modification, 31, 174–201.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lau, K.S.L., Marsee, M.A., Kunimatsu, M.M. et al. Examining Associations Between Narcissism, Behavior Problems, and Anxiety in Non-Referred Adolescents. Child Youth Care Forum 40, 163–176 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-010-9135-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-010-9135-1