Abstract

Although sleep problems often comprise core features of psychiatric disorders, inadequate attention has been paid to the complex, reciprocal relationships involved in the early regulation of sleep, emotion, and behavior. In this paper, we review the pediatric literature examining sleep in children with primary psychiatric disorders as well as evidence for the role of early sleep problems as a risk factor for the development of psychopathology. Based on these cumulative data, possible mechanisms and implications of early sleep disruption are considered. Finally, assessment recommendations for mental health clinicians working with children and adolescents are provided toward reducing the risk of and improving treatments for sleep disorders and psychopathology in children and adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Up to 40% of children experience a sleep problem at some point during their development (Kahn et al. 1989; Mindell et al. 1999). For many, these problems represent transient difficulties that will remit in the absence of specific intervention. For others, however, sleep disruption can endure over extended periods of time and (negatively) impact overall health and behavior. For example, persistent sleep disturbance during childhood has been associated with concurrent and long-term problems in academic performance, school absenteeism, poor impulse control, risk-taking behavior, injury and impaired social functioning (see McLaughlin-Crabtree and Witcher 2008 for a review). Potential effects on physical health are also deleterious, including cardiovascular risks, compromised immune function and metabolic changes such as insulin resistance, which can persist into adulthood in the absence of treatment (Amin et al. 2002; de la Eva et al. 2002; Gozal and Kheirandish-Gozal 2008). Thus, it is apparent that the way children sleep affects nearly every aspect of their functioning.

Perhaps no group is at greater risk for the development of enduring sleep disorders than children with psychiatric illness. It is well-recognized that sleep problems frequently accompany mental health diagnoses, with as many as 80% of adult patients complaining of sleep disruption some time during the course of their illness (Morin and Ware 1996). While historically viewed as a manifestation or prominent feature of psychopathology, the past decade has witnessed an exponential increase in the number of reports highlighting a bidirectional relationship between sleep and emotional and behavioral functioning. For example, in addition to high rates of sleep problems among children with psychiatric disorders, a majority of youth presenting with a primary complaint of insomnia (defined as difficulty initiating/maintaining sleep) meet criteria for a mental health diagnosis (Ivanenko et al. 2004). In fact, early sleep problems independently predict the later development of emotional and behavioral problems including depression, anxiety, inattention and hyperactivity (Gregory et al. 2004; Gregory and O’Connor 2002; Johnson et al. 2000; Ong et al. 2006). Accordingly, many adult psychiatric patients report that their sleep problems originated during childhood (Philip and Guilleminault 1996).

Findings from experimental research are equally supportive of a bidirectional relationship. Results from several investigations reveal that even modest amounts of sleep restriction result in subsequent problems with emotion regulation, mood and attention (Dinges et al. 1997; Leotta et al. 1997; Sagaspe et al. 2006). Among adult anxiety disorder patients, one night of sleep deprivation results in significant increases in anxiety and panic symptoms (Roy-Byrne et al. 1986). Although experimental data are more limited in children, heuristically, just as commonly as the parent of a behavior-problem child seeks the child’s pediatrician’s advice for a sleep problem, a child with a primary sleep disorder is referred to a mental health professional for difficulties regulating daytime behavior and mood.

Together, research and clinical observation underscore a need for clinicians to evaluate sleep among all youth presenting with mental health concerns. Considering the reciprocal relationship between these problems, attention to sleep as part of comprehensive assessment may ultimately assist in reducing the high continuity and relapse rates of psychiatric illness over the life span by revealing underlying processes and factors to be targeted in treatment. Moreover, because early sleep patterns are in part reflective of a child’s ability to self-regulate, prior even to the appearance of more complex behavioral or cognitive developments, the presence of early sleep-related problems may help to identify youth at risk for the later development of psychopathology. In this way, important opportunities for prevention in both clinical and research settings may be revealed. The current paper is therefore aimed at providing an overview of research examining sleep in youth with psychiatric disorders with the goal of better informing assessment and referral practices. For the sake of brevity, broad categories of childhood disorders consistently associated with disturbed sleep are reviewed, though findings are assuredly relevant for all psychiatric diagnoses.

Sleep in Children with Anxiety Disorders

As the most common childhood psychiatric disorders, anxiety disorders occur in up to 20% of children (Costello et al. 2005; Shaffer et al. 1996) and are associated with significant impairments in functioning across multiples domains including academics, family relationships, and social interactions (Ialongo et al. 1994, 1995). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV; APA 1994) includes several anxiety disorders that may include sleep disturbance, including separation anxiety disorder (SAD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In general, however, many non-clinical childhood fears (e.g., monsters under the bed, the dark) are associated with the presence of transient sleep disruption. These problems are for the most part developmentally appropriate and occur in a majority of children (King et al. 1997; Muris et al. 2000). By comparison, nighttime fears that are co-accompanied by severe and persistent sleep problems may be symptomatic of an underlying anxiety disorder (Muris et al. 2000).

Among youth with anxiety disorders rates of parent-reported sleep problems are as high as 95% (Alfano et al. 2006, 2007). While objective evidence of sleep disturbance is more limited, Forbes et al. (2008) used polysomnography (PSG) to examine the sleep of anxious youth compared to depressed and healthy children. Results revealed an increased number of nighttime arousals, longer sleep onset latencies and decreased slow wave sleep (i.e., deep sleep) among anxious children. However, sleep difficulties were generally underreported by this group as compared with objective measures. Hudson et al. (2009) used 1-week sleep diaries to compare the sleep patterns of anxious and control children. Anxious youth had later bedtimes and obtained significantly less sleep during weekdays. Although this study did not find differences in sleep onset latencies and nighttime awakenings, results reported by Forbes et al. (2008) raise some question regarding anxious children’s awareness and reporting of their own sleep.

Other data suggest differences in rates and specific types of sleep problems based on individual diagnoses. For example, Alfano et al. (2007) compared the prevalence of sleep problems among youth with and without specific anxiety diagnoses based on parent and clinician reports. Sleep problems were more common in children with SAD and GAD than in children with social phobia (SOC). Insomnia, refusal to sleep alone, and nightmares were most commonly found. An important limitation of this approach, however, includes the possibility of spurious associations between secondary diagnoses and sleep behaviors. In fact, the presence of comorbid anxiety disorders is not associated with greater levels of sleep disturbance (Alfano et al. 2009). Accordingly, the sleep of youth with primary GAD, SAD, SOC and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) was recently compared (Alfano et al. 2009). A greater proportion of children with primary GAD (85%) reported sleep problems and difficulty waking in the morning compared to the other groups. Thus, consistent with research among adults (Uhde 2000), insomnia occurs early and persists for a majority of children with GAD.

Rapoport et al. (1981) compared the sleep characteristics of adolescents with OCD (ages 13–17 years) to healthy adolescents based on PSG. Significantly reduced sleep efficiency and increased sleep onset latency were found among the OCD group. These adolescents required twice as long as controls to fall asleep. Among a larger sample, Storch et al. (2008) reported that more than 50% of youth with primary OCD experienced trouble sleeping and/or daytime tiredness. Importantly, the presence of sleep disturbance designated a more severe form of illness. By comparison, this does not appear to the case for sleep disturbance in PTSD. Children with a history of trauma and/or abuse exhibit disturbed sleep regardless of whether a PTSD diagnosis is present (Glod et al. 1997). Two studies have reported poorer sleep efficiencies among children with a history of physical compared to sexual abuse (Glod et al. 1997; Sadeh et al. 1995a). Collectively, data suggest the presence of potentially unique mechanisms underlying sleep disruption across childhood anxiety diagnoses.

Both environmental and biological factors account for a significant portion of the variance in sleep and anxiety problems (Gregory et al. 2004; Van den Oord et al. 2000). For example, Warren et al. (2003) found that parents of young children at-risk for anxiety (based on having an anxiety-disordered parent) were overly involved in bedtime routines, and over-involved parenting was associated with high rates of child sleep problems. Thus, inadequate limit setting at night (e.g., delaying bedtimes, permitting co-sleeping) may reinforce anxiety and interfere with the development of necessary self-regulatory skills (Dahl 1996). Hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis dysregulation associated with anxiety also may negatively impact the timing and patterns of children’s sleep. Significantly higher levels of cortisol (i.e., hormone released in response to stress/anxiety) during the pre-sleep period have been found among anxious children compared to depressed and healthy controls (Forbes et al. 2006). Pre-sleep worry and cognitive arousal, prominent features of sleep disturbance among anxious adults, have been implicated as well, with anxious children reporting greater levels of cognitive than somatic arousal at night (Alfano et al. 2009).

Sleep in Children with Depressive Disorders

Depression affects approximately 1% of children and up to 5% of adolescents (Birmaher et al. 1996). Similar to adults, teenage girls are two to three times more likely to suffer from a depressive disorder than teenage boys (Lewinsohn et al. 1993). This often chronic and recurrent illness is associated with significant impairments in educational, family, societal and occupational functioning as well as increased risk of suicide (Rohde et al. 1991, 1994). Although the presence of a sleep problem is not necessary for a DSM-IV diagnosis, more than 90% of depressed children and adolescents report problems with their sleep (Roberts et al. 1995). The majority of youth report symptoms of insomnia and/or poor sleep quality resulting in excessive daytime sleepiness, while approximately 10% report the presence of hypersomnia (i.e., excessive sleep) (Liu et al. 2007). The presence of both insomnia and hypersomnia, present in approximately 10% of depressed youth, is associated with longer depressive episodes and more severe symptomatology (Liu et al. 2007).

Hypersomnia is more common in depressed adolescents than children (Ryan et al. 1987). Depressed adolescents also commonly present with circadian rhythm disorders which involve an inability to fall asleep and awaken at appropriate times (Carskadon 1990). In many cases, delayed sleep phase syndrome (DSPS) is diagnosed, defined as a sleep disorder in which the major sleep episode is delayed in relation to the desired clock time. Adolescents with DSPS are typically unable to fall asleep before midnight and have extreme difficulty waking in the morning for school (Dahl and Carskadon 1995). Symptoms of decreased motivation, social withdrawal, school avoidance, and poor sleep hygiene may converge to result a shifted sleep schedule. Not surprisingly, DSPS often results in impairments in academic and social functioning, as well as increased family conflict; all of which may serve to further increase depressive symptoms. As it is often difficult to differentiate between depressive symptoms and daytime impairments associated with ongoing sleep disruption, thorough assessment should include information about the sleep behaviors and schedules of depressed youth.

Despite the presence of sleep complaints among a majority of youth, objective evidence of sleep disruption is somewhat inconsistent. Based on the use of PSG, several investigations have not found differences in the sleep of depressed and healthy children (Dahl et al. 1991; Puig-Antich et al. 1982), whereas others provide evidence of sleep abnormalities including longer sleep onset latencies and shorter latencies to rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (Emslie et al. 1990; Lahmeyer et al. 1983). Use of actigraphy has revealed the presence of poor sleep quality and abnormal circadian rhythms in this population (Sadeh et al. 1995b; Teicher et al. 1993). While the basis for these differences is unclear, inconsistent findings may be explained, in part, by developmental differences as well as the severity and duration of depressive symptoms present (Dahl and Carskadon 1995). Specifically, with increasing age and with more severe forms of depression, objective evidence of sleep disruption becomes increasingly consistent, revealing reductions in total sleep time, longer sleep onset latencies and shorter latency to REM sleep (Benca et al. 1992).

Although long-term follow-up studies are rare, at least 10% of depressed children and adolescents continue to experience sleep problems after their depressive symptoms remit (Puig-Antich et al. 1983). The continued presence of these problems in the absence of a depressive diagnosis may have important implications for the course of illness. Emslie et al. (2001) found that children and adolescents with sleep onset latencies greater than 10 min following recovery from a depressive episode were significantly more likely to relapse within 12 months compared to youth with no sleep difficulties. This finding corresponds with longitudinal data indicating early sleep disturbance to be a specific risk factor for depression (and anxiety) during adolescence and adulthood (Gregory et al. 2005; Gregory and O’Connor 2002; Johnson et al. 2000). Thus, treating both depressive and sleep symptoms simultaneously may be critical to achieving the best possible clinical outcomes.

Sleep in Children with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) which occurs in 2–17% of youth (Scahill and Schwab-Stone 2000), usually presents during early childhood as an inability to focus and maintain attention, control impulses and suppress overactive behavior (APA 1994). Left untreated, ADHD tends to persist into adolescence and adulthood (Fischer et al. 2005) causing significant impairments in academic, occupational, social and interpersonal functioning (Biederman et al. 1997; Maedgen and Carlson 2000). The disorder is also associated with sleep disturbances that may exacerbate symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity. Poor sleep was listed as a diagnostic symptom of ADHD in previous editions of the DSM, but was removed from DSM-IV based on concern that it represented a non-specific symptom of the disorder (APA 1994). More recent studies indicate the presence of sleep problems in at least 50% of children with ADHD (Corkum et al. 1999); a two to three fold higher prevalence than healthy youth (Owens 2005). The most common sleep complaints reported by parents include difficulty falling/staying asleep, frequent nighttime awakenings and restless sleep (Ball et al. 1997; Kaplan et al. 1987). Studies using PSG or actigraphy have documented delayed sleep onset, abnormalities in REM sleep and/or increased sleep-related movement (Kirov et al. 2004; Konofal et al. 2001; O’Brien et al. 2003). However, no one particular type of sleep problem appears to well-characterize this population of youth.

ADHD is associated with an increased prevalence of certain co-occurring sleep disorders including periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD)/restless legs syndrome (RLS) and sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) (Cortese et al. 2006; O’Brien et al. 2003; Picchietti et al. 1998, 1999). PLMD involves the repeated, involuntarily movement of limbs during sleep whereas RLS movements are a voluntary response to unpleasant sensations in the legs during wakefulness. Both disorders result in disrupted sleep as well as excessive daytime sleepiness. Although many investigations have found considerable night-to-night variability in periodic limb movements (PLM) (Gruber and Sadeh 2004; Gruber et al. 2000), a recent meta-analysis of studies using PSG concluded that increased PLM is the only consistent sleep finding among ADHD children (Sadeh et al. 2006). The specific mechanisms underlying the association between ADHD and PLMD/RLS are not entirely clear, but several investigations indicate a common deficiency in the neurotransmitter dopamine as well as serum ferritin (i.e., cellular iron stores) which is essential for the metabolism of dopamine (Cortese et al. 2005; Konofal et al. 2004; Montplaisir et al. 1999).

Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB), which is associated with numerous physical and behavioral health risks, is characterized by repeated episodes of partial or complete upper airway obstruction during sleep which can cause lowered blood oxygen levels and elevations in blood pressure. In severe cases, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) may be diagnosed. A relationship between SDB and inattention/hyperactivity is well-established. In addition to the fact that youth with ADHD are more likely to have SDB than healthy controls (Cortese et al. 2006), children with SDB (without ADHD) often present with daytime behavioral symptoms that are remarkably similar to those observed among ADHD youth including inattention, hyperactivity and poor impulsive control. This finding lends support to the hypothesis that children with ADHD may actually be under-(as opposed to over-) aroused and display hyperactivity as an adaptive behavior to counteract daytime sleepiness (Owens 2005). Along these lines, snoring, the hallmark symptom of SDB, is more common in children with the hyperactive subtype of the disorder (LeBourgeois et al. 2004; O’Brien et al. 2003). Further, removal of enlarged tonsils and/or adenoids (the leading cause of SDB in children) has been shown to result in significant reductions in hyperactivity post-surgery (Chervin et al. 2006). Thus, it is critically important for clinicians to consider the extent to which symptoms of ADHD and SDB overlap so as to facilitate accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Sleep in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD; also referred to as pervasive developmental disorders) represent a group of disorders typically identified before age 3 and characterized by varying degrees of deficit in communication and socialization as well as patterns of repetitive behaviors and restricted interests (APA 2004). Approximately one out of every 150 children is diagnosed with an ASD (Hertz-Picciotto and Delwiche 2009). Boys are four times more likely to receive the diagnosis than girls. Although ASD are associated with a range of impairments and outcomes, there is increasing evidence for the positive impact of early, intensive interventions targeting both in-home and community-based (e.g., school) behaviors (see Rogers and Vismara 2008).

Despite the fact that sleep problems are highly frequent in ASD children, with prevalence rates ranging from 50–80% (Allik et al. 2006; Krakowiak et al. 2008), sleep disruption is not part of DSM-IV diagnostic criteria. Insomnia is the most common sleep complaint (Richdale 1999), though a range of sleep problems have been reported in this population including irregular sleep-wake patterns, frequent nighttime awakenings, and bedtime resistance (Cotton and Richdale 2006; Honomichl et al. 2002; Patzold et al. 1998; Richdale and Prior 1995). Early sleep studies of autistic children showed abnormalities in REM sleep (Ornitz 1985; Tanguay et al. 1976). However, more recent data among ASD youth have not replicated these findings (Elia et al. 2000). By comparison, sleep initiation and maintenance difficulties have been substantiated by objective sleep measures. For example, Malow et al. (2006) compared the sleep of ASD children and healthy controls based on the use of PSG. The ASD group was divided into “poor sleepers” and “good sleepers” based on parental report. Results showed delayed sleep onset and decreased sleep efficiency among the poor-sleepers compared to the other two groups.

Similar to children with other psychiatric disorders, inadequate sleep and chronic daytime sleepiness are common in ASD children (Allik et al. 2006; Paavonen et al. 2008; Patzold et al. 1998). More specific to this population, core symptoms of ASD appear to be exacerbated or intensified by sleep loss. Difficulties with behavioral and emotional regulation including increased aggression, stereotyped behaviors, social skill deficits, and self-injury are associated with sleep disruption (Allik et al. 2006; Didden and Sigafoos 2001; Hoffman et al. 2005; Schreck et al. 2004). Schreck et al. (2004) found that fewer hours of sleep per night predicted higher autism scores and social skills deficits. Moreover, improvements in sleep are associated with reductions in problematic daytime behaviors (Robinson and Richdale 2004). Intellectual abilities, which vary considerably among ASD youth, do not appear to account for these findings (Patzold et al. 1998; Richdale and Prior 1995). For example, Cotton and Richdale (2006) compared parental report of sleep problems in children with autism, Down syndrome, Prader–Willi syndrome, intellectual disability and typically developing children. Sleep problems were most prevalent in autistic children, including difficulties settling at bedtime and co-sleeping.

The causes of sleep disturbances in children with ASD are multifactorial with a variety of bio-psychosocial factors purported. Difficulties falling asleep and waking during the night may be related to circadian rhythm and associated melatonin abnormalities. Melatonin is an endogenous neurohormone that promotes sleepiness and regulates the sleep/wake cycle, and abnormalities in the amount and/or timing of melatonin release may be responsible for difficulties falling asleep, frequent nighttime and early morning awakenings (Patzold et al. 1998). Several studies have found abnormal melatonin regulation in ASD children including increased daytime and decreased evening melatonin production (Kulman et al. 2000; Ritvo et al. 1993). Exacerbating these abnormalities, social and communication deficits prohibit many ASD children from recognizing important environmental cues that reinforce a regular sleep-wake schedule, such as a consistent bedtime routine (Johnson 1996; Richdale 1999). Hypersensitivities to sound, certain textures or fabrics, and/or light also may contribute to sleep initiation and maintenance difficulties. Treatments that include attention to sleep, including visual schedules depicting appropriate night time routines, use of exogenous melatonin, and/or light therapy have been shown to be efficacious (Gordon 2000; Richdale 1999; Wiggs and Stores 2004).

Practice Implications: Assessment of Pediatric Sleep

While a thorough discussion of assessment methods for evaluating sleep in children is beyond the scope of this paper, in general, practitioners across settings can readily incorporate inquiry regarding sleep into standard assessment procedures by way of clinical interviews, sleep diaries and/or parent and child report measures. These efforts can be highly beneficial both in guiding appropriate referral practices as well as informing treatment protocols. We briefly review these methods and measures below.

Clinical Interviews

Comprehensive clinical interviews for childhood sleep disorders generally include child and parent reports of a child’s sleep history, current sleep schedules, behaviors and habits, surrounding sleep, and the specific nature and duration of difficulties (e.g., bedtime resistance, nighttime awakenings, snoring/gasping during sleep). Although sleep-related impairments often mimic those linked to psychiatric disorders (e.g., increased anxiety, hyperactivity, decreased motivation) and can therefore be challenging to disentangle, potent indicators of insufficient sleep include an inability to awakening in the morning, increased sleep on weekends, and sleepiness in inappropriate settings such as in school. Also, because certain medical problems such as allergies, gastroesophageal reflux, and headaches may contribute to sleep difficulties, interviews should query the presence of physical symptoms and complaints. Along these lines, several types of medications have been shown to alter the timing and architecture of children’s sleep. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and stimulant medications (e.g., methylphenidate) in particular, which are commonly prescribed for various childhood psychiatric diagnoses, have been associated with increased sleep disruption in some children (Armitage et al. 1997; Sangal et al. 2005; Wagner et al. 2004). Thus, prescribing clinicians should consider the potential iatrogenic effects of these medications on sleep. Finally, the presence of certain environmental factors that may cause and/or maintain childhood sleep problems should be considered. Poor parental limit setting and responses to bedtime resistance, inconsistent household routines and bedtimes, co-sleeping, caffeine consumption, and evening use of electronic media including computers and mobile phones may play a central role in ongoing sleep disruption and require attention during treatment.

Sleep Diaries

In line with best-practice standards for adults (Buysse et al. 2006) children with a suspected sleep disorder should be asked to keep a one to two week sleep diary. Sleep diaries usually consist of a one-page, 24-h grid used to record the sleep/wake cycle on a prospective basis. Information captured typically includes nightly bedtimes, time required to fall asleep, length and number of night-time awakenings, morning wake times, and any daytime naps. Young children may need parental assistance in completing diaries with accuracy. Information can be used to calculate key sleep variables including average sleep-onset latency, variability in weekday and weekend sleep times, sleep efficiency, and time spent awake after sleep onset. Sleep diaries provides several benefits over other assessment tools including a detailed, visual depiction of sleep behaviors and habits, and avoidance of potential biases associated with retrospective reporting of sleep. This can also be a helping tool in teaching children and families to recognize connections between sleep behaviors and daytime functioning before, during and after treatment.

Questionnaire Measures

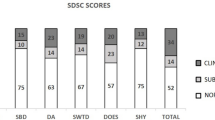

There are several validated and readily available parent-report measures of children’s sleep. The Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CHSQ; Owens et al. 2000a) is a comprehensive measure that yields a total sleep score and eight subscales scores reflecting key sleep domains encompassing a range of medical and behavioral sleep problems including sleep-related anxiety, sleep-disordered breathing, and daytime sleepiness. The CSHQ also assesses average total sleep time and nightly bedtime. Similarly, the Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC; Bruni et al. 1996) is a 27-item parent-report questionnaire designed to assess the most common types of sleep disorders in childhood and adolescence including disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep, disorders of arousal/nightmares, sleep/wake transition disorders and excessive sleepiness.

In terms of child report, the Sleep Self Report (SSR; Owens et al. 2000b) is a 26-item measure designed to be administered to or self-administered by school-aged children 7 to 12 years of age. The SSR assesses sleep domains corresponding to those of the CSHQ. For adolescents, the School Sleep Habits Survey (SSHS; Wolfson and Carskadon 1998) is a reliable measure that has been validated in comparison to both sleep diaries and actigraphy. The SSHS assesses sleep patterns and problems over the past 2 weeks including school-night and weekend variations. In addition, the Pediatric Daytime Sleepiness Scale (PDSS; Drake et al. 2003) is a widely used measure of daytime sleepiness in children and can be used as a gauge of dysfunction associated with insufficient sleep. The PDSS consists of eight items which require children to rate how sleepy they feel in various situations (e.g., at school, riding on the bus, etc.) over the past 2 weeks. The brief format allows for easy administration across settings.

Summary and Conclusions

The associations and linkages between the regulation of sleep, emotion and behavior during early development are both striking and complex. Overall, these reciprocal relationships suggest that: (a) childhood psychiatric disorders may lead to or exacerbate sleep problems; (b) insufficient or disturbed sleep may interfere with a child’s ability to regulate emotion and behavior and lead to mental health problems and disorders; and (c) these problems may persist in a cyclic fashion for extended periods of time, impairing a child’s functioning across numerous areas. While occasional sleep problems are a normal feature of early development, longitudinal data confirm the early presentation of chronic sleep disruption as a prognostic indicator for emotion and behavioral problems in adolescence and adulthood. Thus, ongoing sleep complaints should be considered a “red flag” for further assessment. Although specific mechanisms of sleep disturbance have been linked with certain psychiatric disorders, as a whole, factors underlying sleep and emotional/behavioral problems in children are multifaceted, involving both biological and environmental influences. For this reason, assessment should incorporate the use of multiple informants (children, parents, pediatricians) and methods (clinical interviews, sleep diaries, questionnaires) and consider the reciprocal relationships between nighttime and daytime behaviors. In some cases, sleep may improve with adequate psychiatric treatment, whereas in others, sleep disturbance may persist even in the presence of other improvements and serve to increase relapse risk. Clinicians should therefore assess sleep on an ongoing basis and refer children as needed for appropriate treatment services, particularly when sleep problems do not respond to standard intervention efforts.

References

Alfano, C. A., Beidel, D. C., Turner, S. M., & Lewin, D. S. (2006). Preliminary evidence for sleep complaints among children referred for anxiety. Sleep Medicine, 7, 467–473.

Alfano, C. A., Ginsburg, G. S., & Kingery, J. N. (2007). Sleep-related problems among children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46, 224–232.

Alfano, C. A., Pina, A. A., Zerr, A. G., & Villalta, I. K. (2009). Pre-sleep arousal and sleep problems of anxiety-disordered youth. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. [Epub ahead of print].

Allik, H., Larsson, J.-O., & Smedje, H. (2006). Insomnia in school-age children with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. BioMed Central Psychiatry, 28, 18.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Amin, R. S., Kimball, T. R., Bean, J. A., Jeffries, J. L., Willging, J. P., Cotton, R. T., et al. (2002). Left ventricular hypertrophy and abnormal ventricular geometry in children and adolescents with obstructive sleep apnea. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 165, 1395–1399.

Armitage, R., Emslie, G., & Rintelmann, J. (1997). The effect of fluoxetine on sleep EEG in childhood depression: A preliminary report. Neuropsychopharmacology, 17, 241–245.

Ball, J. D., Tiernan, M., Janusz, J., & Furr, A. (1997). Sleep patterns among children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A re-examination of parental perceptions. Journal of Paediatric Psychology, 22, 389–398.

Benca, R. M., Obermeyer, W. H., Thisted, R. A., & Gillin, J. C. (1992). Sleep and psychiatric disorders: A meta-analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry, 49, 651–668.

Biederman, J., Wilens, T., Mick, E., Faraone, S. V., Weber, W., Curtis, S., et al. (1997). Is ADHD a risk factor for psychoactive substance use disorders? Findings from a four-year prospective follow-up study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 21–29.

Birmaher, B., Ryan, N. D., Williamson, D. E., Brent, D. A., Kaufman, J., Dahl, R. E., et al. (1996). Childhood and adolescent depression: A review of the past 10 years. Part I. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, 1427–1439.

Bruni, O., Ottaviano, S., Guidetti, V., Romoli, M., Innocenzi, M., Cortesi, F., et al. (1996). The sleep disturbance scale for children (SDSC) construction and validation of an instrument to evaluate sleep disturbances in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Sleep Research, 5, 251–261.

Buysse, D. J., Ancoli-Israel, S., Edinger, J. D., Lichstein, K. L., & Morin, C. M. (2006). Recommendations for a standard research assessment of insomnia. Sleep, 29, 1155–1173.

Carskadon, M. A. (1990). Patterns of sleep and sleepiness in adolescents. Pediatrician, 17, 5–12.

Chervin, R. D., Ruzicka, D. L., Giordani, B. J., Weatherly, R. A., Dillon, J. E., Hodges, E. K., et al. (2006). Sleep-disordered breathing, behavior and cognition in children before and after adenotonsillectomy. Pediatrics, 117, 769–778.

Corkum, P., Moldofsky, H., Hogg-Johnson, S., Humphries, T., & Tannock, R. (1999). Sleep problems in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Impact of subtype, comorbidity and stimulant medication. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38, 1285–1294.

Cortese, S., Konofal, E., Lecendreux, M., Arnulf, I., Mouren, M. C., Darra, F., et al. (2005). Restless legs syndrome and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A review of the literature. Sleep, 28, 1007–1013.

Cortese, S., Konofal, E., & Yateman, N. (2006). Sleep and alertness in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review of the literature. Sleep, 29, 504–511.

Costello, E. J., Egger, H., & Angold, A. (2005). 10-year research update review: The epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: I. Methods and public health burden. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 44, 972–986.

Cotton, S., & Richdale, A. (2006). Brief report: Parental descriptions of sleep problems in children with autism, down syndrome, and Prader–Will syndrome. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 27, 151–161.

Dahl, R., & Carskadon, M. A. (1995). Sleep and its disorders in adolescence. In M. Kryger, T. Roth, & W. Dement (Eds.), Principles and practice of sleep medicine in the child (2nd ed., Vol. 2, pp. 19–27). Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders.

Dahl, R. E., Ryan, N. D., Birmaher, B., Al-Shabbout, M., Williamson, D. E., Neidig, M., et al. (1991). Electroencephalographic sleep measures in prepubertal children. Psychiatry Research, 38, 201–214.

de la Eva, R., Baur, L., Donaghue, K., & Waters, K. (2002). Metabolic correlates with obstructive sleep apnea in obese subjects. Journal of Pediatrics, 140, 654–659.

Didden, R., & Sigafoos, J. (2001). A review of the nature and treatment of sleep disorders individuals with developmental disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 22, 255–272.

Dinges, D. F., Pack, F., Williams, K., Gillen, K. A., Powell, J. W., Ott, G. E., et al. (1997). Cumulative sleepiness, mood disturbance and psychomotor vigilance performance decrements during a week of sleep restricted to 4–5 hours per night. Sleep, 20, 267–277.

Drake, C., Nickel, C., Burduvali, E., Roth, T., Jefferson, C., & Badia, P. (2003). The pediatric daytime sleepiness scale (PDSS): Sleep habits and school outcomes in middle-school children. Sleep, 26, 455–458.

Elia, M., Ferri, R., Musumeci, S. A., Del Gracco, S., Bottitta, M., Scuderi, C., et al. (2000). Sleep in subjects with autistic disorder: A neurophysiological and psychological study. Brain Development, 22, 88–92.

Emslie, G. J., Armitage, R., Weinberg, W. A., Rush, A. J., Mayes, T. L., & Hoffmann, R. F. (2001). Sleep polysomnography as a predictor of recurrence in children and adolescents with major depressive disorder. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 4, 159–168.

Emslie, G. J., Rush, A. J., Weinberg, W. A., Rintelmann, J. W., & Roffwarg, H. P. (1990). Children with major depression show reduced rapid eye movement latencies. Archives of General Psychiatry, 47, 119–124.

Fischer, M., Barkley, R., Smallish, L., & Fletcher, K. (2005). Executive functioning in hyperactive children as young adults: Attention, inhibition, response perseveration, and the impact of comorbidity. Developmental Neuropsychology, 27, 107–133.

Forbes, E. E., Bertocci, M. A., Gregory, A. M., Ryan, N. D., Axelson, D. A., Birmaher, B., et al. (2008). Objective sleep in pediatric anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 148–155.

Forbes, E. E., Williamson, D. E., Ryan, N. D., Birmaher, B., Axelson, D. A., & Dahl, R. E. (2006). Peri-sleep-onset cortisol levels in children and adolescents with affective disorders. Biological Psychiatry, 59, 24–30.

Glod, C. A., Teicher, M. H., Hartman, C. R., & Harakal, B. S. (1997). Increased nocturnal activity and impaired sleep maintenance in abused children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 1236–1243.

Gordon, N. (2000). The therapeutics of melatonin: A paediatric perspective. Brain development, 22, 213–217.

Gozal, D., & Kheirandish-Gozal, L. (2008). The multiple challenges of obstructive sleep apnea in children: Morbidity and treatment. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 20, 654–658.

Gregory, A. M., Caspi, A., Eley, T. C., Moffitt, T. E., O’Connor, T. G., & Poulton, R. (2005). Prospective longitudinal associations between persistent sleep problems in childhood and anxiety and depressive disorders in adulthood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33, 157–163.

Gregory, A. M., Eley, T. C., O’Conner, T. G., & Plomin, R. (2004). Etiologies of associations between childhood sleep and behavioral problems in a large twin sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43, 744–751.

Gregory, A. M., & O’Connor, T. G. (2002). Sleep problems in childhood: A longitudinal study of developmental change and association with behavioral problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, 964–971.

Gruber, R., & Sadeh, A. (2004). Sleep and neurobehavioral functioning in boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and no reported breathing problems. Sleep, 27, 267–273.

Gruber, R., Sadeh, A., & Raviv, A. (2000). Instability of sleep patterns in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 495–501.

Hertz-Picciotto, I., & Delwiche, L. (2009). The rise in autism and the role of age at diagnosis. Epidemiology, 20, 84–90.

Hoffman, C. D., Sweeney, D. P., Gilliam, J. E., Apodaca, D. D., Lopez-Wagner, M. C., & Castillo, M. M. (2005). Sleep problems and symptomology in children with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 20, 194–200.

Honomichl, R. D., Goodlin-Jones, B. L., Burnham, M., Gaylor, E., & Anders, T. F. (2002). Sleep patterns of children with pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 32, 553–561.

Hudson, J. L., Gradisar, M., Gamble, A., Schniering, C. A., & Rebelo, I. (2009). The sleep patterns and problems of clinically anxious children. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47, 339–344.

Ialongo, N., Edelsohn, G., Werthamer-Larsson, L., Crockett, L., & Kellam, S. (1994). The significance of self-reported anxious symptoms in first-grade children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 22, 441–455.

Ialongo, N., Edelsohn, G., Werthamer-Larsson, L., Crockett, L., & Kellam, S. (1995). The significance of self-reported anxious symptoms in first-grade children: Prediction to anxious symptoms and adaptive functioning in fifth grade. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 36, 427–437.

Ivanenko, A., Barnes, M., Crabtree, V., & Gozal, D. (2004). Psychiatric symptoms in children with insomnia referred to a pediatric sleep medicine center. Sleep Medicine, 5(3), 253–259.

Johnson, C. R. (1996). Sleep problems in children with mental retardation and autism. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 5, 673–683.

Johnson, E. O., Chilcoat, H. D., & Breslau, N. (2000). Trouble sleeping and anxiety/depression in childhood. Psychiatry Research, 94, 93–102.

Kahn, A., Van de Merckt, C., Rebuffat, E., Mozin, M. J., Sottiaux, M., Blum, D., et al. (1989). Sleep problems in healthy preadolescents. Pediatrics, 84, 542–546.

Kaplan, B. J., McNicol, J., Conte, R. A., & Moghadam, H. K. (1987). Sleep disturbance in preschool-aged hyperactive and nonhyperactive children. Pediatrics, 80, 839–844.

King, N., Ollendick, T. H., & Tonge, B. J. (1997). Children’s nighttime fears. Clinical Psychology Review, 17, 431–443.

Kirov, R., Kinkelbur, J., Heipke, S., Kostanecka-Endress, T., Westhoff, M., Cohrs, S. E., et al. (2004). Is there a specific polysomnographic sleep pattern in children with attention. Journal of Sleep Research, 13, 87–93.

Konofal, E., Lecendreux, M., Arnulf, I., & Mouren, M. C. (2004). Iron deficiency in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, 158, 1113–1115.

Konofal, E., Lecendreux, M., Bouvard, M. P., & Mouren-Simeoni, M. C. (2001). High levels of nocturnal activity in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A video analysis. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 55, 97–103.

Krakowiak, P., Goodlin-Jones, B., Hertz-Picciotto, I., Croen, L. A., & Hansen, R. L. (2008). Sleep problems in children with autism spectrum disorders, developmental delays, and typical development: A population-based study. Journal of Sleep Research, 17, 197–206.

Kulman, G., Lissoni, P., Rovelli, F., Roselli, M. G., Brivio, F., & Sequeri, P. (2000). Evidence of pineal endocrine hypofunction in autistic children. Neuroendocrinology Letters, 21, 31–34.

Lahmeyer, H. W., Poznanski, E. O., & Bellu, S. N. (1983). EEG sleep in depressed adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry, 40, 1150–1153.

LeBourgeois, M. K., Avis, K., Mixon, M., Harsh, J., & Olmi, J. (2004). Snoring, sleep quality, and sleepiness across attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) subtypes. Sleep, 27, 520–525.

Leotta, C., Carskadon, M. A., Acebo, C., Seifer, R., & Quinn, B. (1997). Effects of acute sleep restriction on affective response in adolescents: Preliminary results. Sleep Research, 26, 201.

Lewinsohn, P. M., Hops, H., Roberts, R. E., Seeley, J. R., & Andrews, J. A. (1993). Adolescent psychopathology I: Prevalence and incidence of depression and other DSM-III-R disorders in high school students. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 102, 133–144.

Liu, X., Buysse, D. J., Gentzler, A. L., Kiss, E., Mayer, L., Kapornai, K., et al. (2007). Insomnia and hypersomnia associated with depressive phenomenology and comorbidity in childhood depression. Sleep, 30, 83–90.

Maedgen, J. W., & Carlson, C. L. (2000). Social functioning and emotional regulation in the attention deficit hyperactivity disorder subtypes. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 29, 30–42.

Malow, B. A., Marzec, M. L., McGrew, S. G., Wang, L., Henderson, L. M., & Stone, W. L. (2006). Characterizing sleep in children with autism spectrum disorders: A multidimensional approach. Sleep, 29, 1563–1571.

McLaughlin-Crabtree, V., & Witcher, L. A. (2008). Impact of sleep loss on children and adolescents. In A. Ivanenko (Ed.), Sleep and psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents (pp. 139–148). New York, NY: Informa Healthcare.

Mindell, J. A., Owens, J. A., & Carskadon, M. A. (1999). Developmental features of sleep. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 8, 695–725.

Montplaisir, J., Nicolas, A., Denesle, R., & Gomez-Mancilla, B. (1999). Restless legs syndrome improved by pramipexole: A double-blind randomized trial. Neurology, 52, 938–943.

Morin, C. M., & Ware, J. C. (1996). Sleep and psychopathology. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 5, 211–224.

Muris, P., Merckelbach, H., Gadet, B., & Moulaert, V. (2000). Fears, worries, and scary dreams in 4- to 12-year-old children: Their content, developmental pattern, and origins. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 29, 43–52.

O’Brien, L. M., Holbrook, C. R., Mervis, C. B., Klaus, C. J., Bruner, J. L., Raffield, T. J., et al. (2003). Sleep and neurobehavioral characteristics of 5 to 7 year old children with parentally reported symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder. Pediatrics, 111, 554–563.

Ong, S. H., Wickramaratne, P., Min, T., & Weissman, M. M. (2006). Early childhood sleep and eating problems as predictors of adolescent and adult mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 96, 1–8.

Ornitz, E. M. (1985). Neurophysiology of infantile autism. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 24, 251–262.

Owens, J. A. (2005). The ADHD and sleep conundrum: A review. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 26, 312–322.

Owens, J. A., Spirito, A., & McGuinn, M. (2000a). The children’s sleep habits questionnaire (CSHQ): Psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children. Sleep, 23, 1–9.

Owens, J. A., Spirito, A., McGuinn, M., & Nobile, C. (2000b). Sleep habits and sleep disturbance in school-aged children. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 21, 27–36.

Paavonen, E. J., Vehkalahti, K., Vanhala, R., von Wendt, L., Nieminen-von Wendt, T., & Aronen, E. T. (2008). Sleep in children with Asperger syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 41–51.

Patzold, L. M., Richdale, A. L., & Tonge, B. J. (1998). An investigation into sleep characteristics of children with autism and Aspergers disorder. Journal of Paediatric Child Health, 34, 528–533.

Philip, P., & Guilleminault, C. (1996). Adult psychophysiologic insomnia and positive history of childhood insomnia. Sleep, 19, S16–S22.

Picchietti, D. L., England, S. J., Walters, A. S., Willis, K., & Verrico, T. (1998). Periodic limb movement disorder and restless leg syndrome in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Child Neurology, 13, 588–594.

Picchietti, D. L., Underwood, D. J., & Farris, W. A. (1999). Further studies on periodic limb movement disorder and restless legs syndrome in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Movement Disorders, 14, 1000–1007.

Puig-Antich, J., Goetz, R., Hanlon, C., Davies, M., Thompson, J., Chambers, W. J., et al. (1982). Sleep architecture and REM measures in pre-pubertal children with major depression. A controlled study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 39, 932–939.

Puig-Antich, J., Goetz, R., Hanlon, C., Tabrizi, M. A., Davies, M., & Weitzman, E. D. (1983). Sleep architecture and REM sleep measures in prepubertal major depressives. Studies during recovery from the depressive episode in a drug-free state. Archives of General Psychiatry, 40, 187–192.

Rapoport, J., Elkins, R., Langer, D. H., Sceery, W., Buchsbaum, M. S., Gillin, J. C., et al. (1981). Childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 138, 1545–1554.

Richdale, A. L. (1999). Sleep problems in autism: Prevalence, cause, and intervention. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 41, 60–66.

Richdale, A. L., & Prior, M. R. (1995). The sleep/wake rhythm in children with autism. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 4, 175–186.

Ritvo, E. R., Ritvo, R., Yuwiler, A., Brothers, A., Freeman, B. J., & Plotkin, S. (1993). Elevated daytime melatonin concentrations in autism: A pilot study. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2, 75–78.

Roberts, R. E., Lewinsohn, P. M., & Seeley, J. R. (1995). Symptoms of DSM-III-R major depression in adolescence: Evidence from an epidemiological survey. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 34, 1608–1617.

Robinson, A. M., & Richdale, A. L. (2004). Sleep problems in children with intellectual disability: Parental perceptions of sleep problems and views of treatment effectiveness. Child: Care, Health and Development, 30, 139–150.

Rogers, S. J., & Vismara, L. A. (2008). Evidence-based comprehensive treatments for early autism. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 8–38.

Rohde, P., Lewinsohn, P. M., & Seeley, J. R. (1991). Comorbidity of unipolar depression: Comorbidity with other mental disorders in adolescents and adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 214–222.

Rohde, P., Lewinsohn, P. M., & Seeley, J. R. (1994). Are adolescents changed by an episode of major depression? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 33, 1289–1298.

Roy-Byrne, P. P., Uhde, T. W., & Post, R. M. (1986). Effects of one night’s sleep deprivation on mood and behavior in panic disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 43, 895–899.

Ryan, N. D., Puig-Antich, J., Ambrosini, P., Rabinovich, H., Robinson, D., Nelson, B., et al. (1987). The clinical picture of major depression in children and adolescents. Archives of General Psychiatry, 44, 854–861.

Sadeh, A., Hauri, P. J., Kripke, D. F., & Lavie, P. (1995a). The role of actigraphy in the evaluation of sleep disorders. Sleep, 18, 288–302.

Sadeh, A., McGuire, J. P., Sachs, H., Seifer, R., Tremblay, A., Civita, R., et al. (1995b). Sleep and psychological characteristics of children on a psychiatric inpatient unit. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 34, 813–819.

Sadeh, A., Pergamin, L., & Bar-Haim, Y. (2006). Sleep in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analysis of polysomnographic studies. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 10, 381–398.

Sagaspe, P., Sanchez-Ortuno, M., Charles, A., Taillard, J., Valtat, C., Bioulac, B., et al. (2006). Effects of sleep deprivation on color-word, emotional, and specific stroop interference and on self-reported anxiety. Brain and Cognition, 60, 76–87.

Sangal, R. B., Owens, J. A., & Sangal, J. (2005). Patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder without observed apneic episodes in sleep or daytime sleepiness have normal sleep on polysomnography. Sleep, 28, 1143–1148.

Scahill, L., & Schwab-Stone, M. (2000). Epidemiology of ADHD in school-age children. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 9, 541–555.

Schreck, K. A., Mulick, J. A., & Smith, A. F. (2004). Sleep problems as possible predictors of intensified symptoms of autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 25, 57–66.

Shaffer, D., Fisher, P., Dulcan, M. K., & Davies, M. (1996). The NIMH diagnostic interview schedule for children version 2.3 (DISC-2.3). Description, acceptability, prevalence rates, and performance in the MECA study. Methods for the epidemiology of child and adolescent mental disorders study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 35(86), 5–877.

Storch, E. A., Murphy, T. K., Lack, C. W., Geffken, G. R., Jacob, M. L., & Goodman, W. K. (2008). Sleep-related problems in pediatric obsessive compulsive disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22, 877–885.

Tanguay, P. E., Ornitz, E. M., Forsythe, A. B., & Ritvo, E. R. (1976). Rapid eye movement (REM) activity in normal and autistic children during REM sleep. Journal of Autism and Childhood Schizophrenia, 6, 275–288.

Teicher, M. H., Glod, C. A., Harper, D., Magnus, E., Brasher, C., Wren, F., et al. (1993). Locomotor activity in depressed children and adolescents: I. Circadian dysregulation. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 32, 760–769.

Uhde, T. W. (2000). Anxiety disorders. In M. H. Kryger, T. Roth, & W. C. Dement (Eds.), Principles and practice of sleep medicine. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders.

Van den Oord, E. J. C., Boomsma, D. I., & Verhulst, F. C. (2000). A study of genetic and environmental effects on the co-occurrence of problem behaviors in three-year-old-twins. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 109, 360–372.

Wagner, K. D., Berard, R., Stein, M. B., Wetherhold, E., Carpenter, D. J., Perera, P., et al. (2004). A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of paroxetine in children and adolescents with social anxiety disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61, 1153–1162.

Warren, S. L., Gunnar, M. R., Kagan, J., Anders, T. F., Simmens, S. J., Rones, M., et al. (2003). Maternal panic disorder: Infant temperament, neurophysiology, and parenting behaviors. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42, 814–825.

Wiggs, L., & Stores, G. (2004). Sleep patterns and sleep disorders in children with autistic spectrum disorders: Insights using parent report and actigraphy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 46, 372–380.

Wolfson, A. R., & Carskadon, M. A. (1998). Sleep schedules and daytime functioning in adolescents. Child Development, 69, 875–887.

Further Reading

Dahl, R. E. (1996). The regulation of sleep and arousal: Development and psychopathology. Developmental Psychopathology, 8, 3–27.

Ivanenko, A. (2008). Sleep and psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents. New York, NY: Informa Healthcare.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (K23MH081188) awarded to the first author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alfano, C.A., Gamble, A.L. The Role of Sleep in Childhood Psychiatric Disorders. Child Youth Care Forum 38, 327–340 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-009-9081-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-009-9081-y