Abstract

A series of platinum loaded catalysts supported on cation (Me)-doped cerium dioxide (Me = Ba, La, Y, Hf and Zn) was prepared by co-precipitation of the Me-nitrates and impregnation of a Pt precursor. Low temperature water–gas shift activity depends on the nature of dopant employed, varying in the order of Ba > Y > Hf > La > undoped ceria > Zn. TPR-XANES measurements with flowing hydrogen reveal that adding dopants to ceria facilitate ceria reduction and increases the extents of both surface shell and bulk reduction of ceria. Experimental results confirm past theoretical models that dopants enhance both O-mobility and reducibility of ceria. DRIFTS measurements of the transient decomposition of formates in steam suggest that formate half-life follows the trend Zn > undoped ceria > La > Hf > Y > Ba, indicating that the formate decomposition rate is enhanced by the addition of most of the dopants tested. Taken together, the results suggest that dopant addition improves the WGS rate by increasing the O-mobility of O-bound associated intermediates. Therefore, less Pt and Ce, which are expensive, is required to achieve comparable levels of activity.

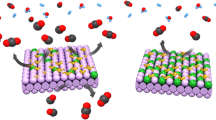

Graphical Abstract

TPR-XANES profiles of 0.5% Pt/ceria catalyst with and without Y-dopant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The water–gas shift reaction (WGS) plays a critical role in the production of hydrogen from fossil and renewable resources. It has attracted great attention because of its applications in producing syngas for chemicals and liquid fuels, providing hydrogen-rich streams for fuel cells [1, 2] and processing exhaust gases from automobiles [3–6]. WGS is a reversible and an exothermic chemical reaction and thus limited by thermodynamic equilibrium at high temperatures. At low temperatures, the thermodynamics are favorable, but the reaction is constrained by slow kinetics. Commercially, the WGS reaction is performed in two stages to overcome the thermodynamic and kinetic limitations of the reaction. The two steps involve a high-temperature (350–500°C) shift (HT-WGS) reaction typically over Fe2O3/Cr2O3 catalysts at which thermodynamics limits the equilibrium conversion [1], followed by a low temperature (200–250°C) shift (LT-WGS) reaction over a Cu/ZnO-based catalysts, in which thermodynamics are favorable but the reaction rate is constrained by kinetics, such that highly active catalysts are necessary to provide adequate activity.

Precious metals dispersed on partially reducible oxides (PRO) e.g., ceria, zirconia, thoria, and titania are reported as promising catalysts for LTS in fuel processors for fuel cell applications, because they exhibit high activity and are non-pyrophoric relative to the conventional Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalyst, an important factor considering that the catalyst should be resistant to repeated start-up/shut-down cycles [7, 8]. The WGS activity of ceria-supported precious metal catalysts can be enhanced significantly by addition of surface promoters [9–14]. This has been attributed to the effects induced by the presence of promoters on the surface properties of ceria [14], including reducibility, oxygen storage capacity and resistance to sintering [13]. It has been also proposed that the role of the promoter is to lower the barrier for oxygen transfer from ceria to the metal [9], thereby facilitating oxidation of adsorbed CO. Recently we have conducted numerous studies with Pt/CeO2 catalysts, and our findings support a low-temperature WGS reaction mechanism involving surface formate intermediates, as proposed by Shido and Iwasawa [15, 16]. The catalytically active sites for formation of the intermediate were found to be Type II bridging OH groups [15–19] on partially reduced ceria, and these react with CO to generate surface formates. The relative stability of the formates at low temperature is such that their decomposition is proposed to be the elementary step that is rate limiting. However, another important consideration is that mounting evidence suggests that H2O promotes the forward decomposition rate of surface formates during WGS to H2 and unidentate carbonate [15, 16], which decomposes to CO2 to regenerate the OH groups, completing the catalytic cycle. We have recently verified the autocatalytic role of H2O in transient formate decomposition experiments [20]. One role of the metal (e.g., Pt, Rh) is to promote the surface reduction of ceria to generate the active bridging OH groups at lower temperatures [15, 21].

The activity of fresh Pt/ceria catalysts was found to be not enough to meet the weight and cost constraints found in automotive applications [22]. As a result, efforts are made to further increase catalytic activity and to improve structural stability of ceria-supported noble metal catalysts. Current research aims to reduce costs by restricting the amounts of both precious and rare earth metals involved in the catalyst formulation. It was demonstrated [23] that both higher formate decomposition and low-temperature shift rates are achieved at a significant cost if one resorts to increasing Pt levels. Thus, another role of Pt is to assist in promoting formate decomposition by assisting in H-abstraction, where Pt is a porthole for H2 removal [23]. Increasing Pt loading improves the reducibility of the catalyst, thus increasing the number of active bridging OH groups on the surface, and increases the platinum-ceria interface to increase the formate turnover rate. However, the problem of decreasing noble metal loadings while maintaining high activity poses a significant challenge. Less surface intermediate in the rapid reaction zone (RRZ) [24] close to the platinum-ceria interface means that, if the amount of Pt is to be decreased, either (a) the dispersion of Pt must be increased or (b) the rate of surface diffusion of associated intermediates to the platinum-ceria interface must be enhanced. In the first case, one challenge is that the metal-support interaction [23, 25] prevents activation of the catalyst components (i.e., reduction of Pt and the ceria surface shell) within temperatures needed for LTS. In the latter case, there is no guarantee of improved CO conversion rates if decomposition of the surface intermediate is slow relative to its surface diffusion rate. As explained by Duprez [26], oxygen mobility in the partially reducible oxide (PRO) may be an important parameter that could be developed to improve the surface diffusion rates of O-bound intermediates during low-temperature water–gas shift, such that reaction intermediates (e.g., formates and carbonates [8, 23] or perhaps carboxylates [27]) are supplied at adequate rates to the platinum-ceria interface. Although carboxylates have recently been suggested as alternative surface intermediates to formates/carbonates, it should be noted that the species has not been identified by infrared spectroscopy, which is not a satisfying conclusion. Our view on this subject and continued support of the formate mechanism is described in a recent research account [28].

Metal-modified ceria has higher oxygen storage capacity and enhanced reducibility than pure ceria. The addition of metal dopants leads to the formation of oxygen vacancies in ceria, which is expected to increase the redox activity [29]. The addition of dopants to ceria may have two consequences: (1) to increase the number of oxygen vacancies in the ceria structure and (2) to improve the reducibility by weakening the Ce–O bond through lattice strain. In the present study we performed a comparative analysis regarding these aspects using as examples platinum catalysts supported on ceria doped by Ba, La, Y, Hf and Zn. The nature of the dopants and their influence on catalyst reducibility, formate mobility, and WGS activity, are discussed. Special emphasis is placed on using time resolved EXAFS and XANES, a technique that has been successfully applied for examining the oxygen storage and release properties of CeO2–ZrO2 mixed oxides [30].

2 Experimental

2.1 Catalyst Preparation

High surface area mixed oxide solid solutions of CexMe1−x O y were prepared via a homogenous precipitation of cerium and nitrate salt of the dopant, using NaOH (Sigma-Aldrich, 97%, 20–40 mesh beads) as the precipitating agent. In this method, appropriate amounts of Ce(NO3)3·6H2O (Alfa Aesar, 99.5%) and nitrate salt of the dopant were first dissolved simultaneously in deionized water at room temperature. The total metal ion concentration was maintained at 1 M for all experiments. The nitrate salt of dopants was stirred at 500 RPM at room temperature until completely dissolved. The nitrate salt of dopant solution was slowly added drop-wise to a sodium hydroxide solution (1 M), accompanied by constant stirring at 700 RPM to avoid the formation of lumps and to ensure a complete dissolution. The pH was maintained at ~12 to ensure simultaneous precipitation of dopants and ceria. The solution was refluxed at 80°C with constant stirring (500 RPM) for 20 h. The resulting precipitate was filtered and suspended in 4 L of deionized water a total of three times, and each time the solution was stirred for 1 h at room temperature to remove Na ions. The resulting residue was filtered and washed thoroughly with deionized water. It was then dried in a static oven at 110°C overnight. The solid material obtained was crushed and the resulting powder was calcined in air in a muffle furnace at 400°C for 4 h.

To the resulting supports, platinum was deposited via incipient wetness impregnation by taking into consideration the pore volume of the support as measured by N2 physisorption. Appropriate amounts of Pt (NH3)4(NO3)2 (Alfa Aesar, 99%) were dissolved in deionized water, and the solution was added drop-wise to the supports to obtain 0.5% by weight Pt. The resulting material was dried in a static oven overnight at 110°C and then calcined at 400°C for 4 h. Before testing, the catalyst samples were pelletized at 15 tons per square inch for 5 s and sieved in the diameter range of 355 μm < Φ < 600 μm.

2.2 BET Surface Area and Porosity

BET surface area was determined using a Micromeritics TRISTAR 3000 gas adsorption analyzer. In each test, approximately 0.30 g of the sample was used. The adsorption gas was nitrogen and the sample analyses were performed at the boiling temperature of liquid nitrogen. Samples were degassed under vacuum for 12 h before conducting the nitrogen adsorption measurements. The specific surface areas were determined by the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method.

2.3 X-ray Absorption Near Edge Spectroscopy (XANES)

In situ H2-TPR XAFS studies were performed at the Materials Research Collaborative Access Team (MR-CAT) beamline at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. A cryogenically cooled Si (111) monochromator selected the incident energy and a rhodium-coated mirror rejected higher order harmonics of the fundamental beam energy. The experiment setup was similar to that outlined by Jacoby [31]. A stainless steel multi-sample holder (4.0 mm i.d. channels) was used to monitor the in situ reduction of six samples during a single TPR run. The catalyst samples were diluted with silica gel at a weight ratio (silica/sample) of approximately 4.0. Approximately 3.0 mg of each sample was loaded as a self-supporting wafer in each channel. The holder was placed in the center of a quartz tube, equipped with gas and thermocouple ports and Kapton windows. The amount of sample used was optimized for the Ce LIII edge (5723 eV). The quartz tube was placed in a clamshell furnace mounted on a positioning table. Each sample cell was positioned relative to the beam by finely adjusting the position of the table to an accuracy of 20 μm (for repeated scans). Once the sample positions were fine-tuned, the reactor was purged with helium for more than 5 min at 30 ml/min. Then, the reactant gas (H2/He, 4%) was flowed through the samples (30 ml/min) and a temperature ramp of ~1.8°C/min was initiated for the furnace. Samples were ramped to ~980°C.

The Ce LIII-edge spectra were recorded in transmission mode and a Cr metallic foil spectrum was measured simultaneously with each sample spectrum for energy calibration. X-ray absorption spectra for each sample were collected from 5623 to 6032 eV, with a step size of 0.40 eV and acquisition times of 30 s per spectrum. By measuring each sample, in turn, and repeating, this allowed 182 scans to be collected for each sample over a 7.5 h period. A sample’s temperature change from the absorption edge through the end of the scan was then about 0.7°C, while a spectrum was measured approximately every 0.9°C. Data reduction of the XAFS spectra was carried out using the WinXAS program [32], and raw data were processed to give the normalized XANES spectra. Linear combination fitting of spectra with appropriate reference compounds was carried out. The initial spectrum of each catalyst was used as a fingerprint for the Ce4+ oxidation state, while the final spectrum of the 0.5%Pt/Hf0.50Ce0.50Ox catalyst following TPR was used as a fingerprint of the Ce3+ oxidation state for all samples, since its lineshape resembled Ce3+ compounds, such as Ce(NO3)3.

2.4 Diffuse Reflectance Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (DRIFTS)

A Nicolet Nexus 870 infrared spectrometer was used equipped with a DTGS-TEC detector. A chamber fitted with ZnSe windows was utilized as the WGS reactor for in situ measurements. Experimental procedures are provided elsewhere [33]. For each run, the catalyst was first activated at 350°C in 50 ml/min of 33% H2 (balance He) for 2 h and then cooled to 130°C. Formates were generated using the following procedure. Steady state low-temperature shift was first carried out at 225°C using a mixture consisting of 37.5 ml/min of 10% CO/He, 62.5 ml/min of H2O, and 33.75 ml/min He. This condition produces a rate-limited coverage of surface formate on the catalyst surface. To achieve a high coverage of formate, H2O was switched off and CO adsorption was carried out using 37.5 ml/min of 10% CO/He and 96.25 ml/min He. When H2O is completely removed from the system, formate generated from reaction of Type II bridging OH groups and CO cannot at low temperature undergo forward decomposition to hydrogen and unidentate carbonate, the latter being the precursor to CO2 formation. Thus, when the water is switched off, the steady state formate coverage increases. After the formate was generated, the temperature was lowered to 130°C and the catalyst was then exposed to H2O vapor generated from a bubbler using helium at 50 ml/min. Since decomposition of formate was found to be quite rapid in previous transient formate decomposition studies [20, 34, 35] when the concentration of H2O was high (e.g., 32–56%), which is typical of steady state fuel processor conditions, the decision was made to significantly slow down the forward formate decomposition rate by employing only 3% H2O as produced using the bubbler. It should be noted that, after a complete coverage of formate is generated on the surface of Pt/ceria, when exposed to H2O the formates have been observed to decompose completely in the LTS temperature range in ~20 s [36]. During decomposition, an intense CO2 peak was observed due to forward decomposition, which stopped only after no formate remained on the surface.

2.5 Catalytic Testing Using a Fixed Bed Reactor

Catalytic tests for the LT-WGS reaction were carried out in a stainless steel fixed-bed tubular reactor (0.444 in i.d.) under steady state conditions. Typically, the catalysts were pressed into pellets, crushed, and sieved to yield grains of 355–600 μm in diameter. A 200-mg catalyst sample diluted with 1800-mg glass beads (60–80 μm in size) was packed between two layers of quartz wool. Using the glass beads ensured plug flow was maintained and minimized the effect of heat generated by the mildly exothermic reaction. The temperature of the catalyst bed was monitored by a thermocouple (Fe–Cr) and maintained by a temperature controller (Ω Omega CN 3251-R). Prior to testing, the catalysts were first reduced in H2 (100 ml/min) at 350°C for 1 h (ramp of 4°C/min). A gas mixture containing 3.0% CO, 26.1% H2O, 29.9% H2, 3.7% N2 (balance He) was used for the catalytic tests to mimic, except for the case of CO2, LTS conditions found in a typical fuel processor for fuel cell applications. The dry gases were controlled using Brooks mass flow controllers. Steam was provided to the system via a steam generator consisting of a hollow cylinder (50 mm i.d., 150 mm long) packed with quartz wool. Water was fed by infusion with a syringe pump (Thermo scientific, model Orion M361) into the steam generator via a 1/16 in. needle with a side-port hole. The whole system was heated to 180°C to avoid condensation of H2O. The feed was adjusted in bypass mode to obtain a steady state concentration of CO/H2O/N2/H2/He prior to bringing the catalyst online (concentration = 3.0/26.1/3.7/29.9/37.3 mol%, where N2 was used as an internal standard). The products were passed through a cold trap cooled to 0°C to condense water from the gas prior to GC analysis. The SRI 8610C GC includes two columns [6 ft (3.658 m) silica gel packed and 3 ft (1.829 m) molecular sieve packed] and two detectors (FID and TCD). To boost the sensitivity of the CO and CO2 signals, the GC incorporates a methanizer, such that these products can be analyzed by FID.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 BET Surface Area and Porosity

The results of nitrogen physisorption obtained for support materials are summarized in Table 1, and the corresponding 0.5% platinum loaded catalysts are shown in Table 2. The BET surface area of the as prepared pure ceria was found to be 114 m2/g. Doped ceria support surface areas were found to be higher or lower than pure ceria, and may depend on the surface area of the dopant. After the platinum impregnation, the surface areas dropped somewhat more than if the ceria or doped ceria were the only contributor to the area. This decrease in the BET surface area upon platinum impregnation is attributed to a fraction of platinum crystallites blocking the smaller pores of the support.

3.2 X-ray Absorption Near Edge Spectroscopy (XANES)

To directly monitor the reduction of the catalyst in H2, in situ TPR-XANES was employed, as the white line provides information about the density of unoccupied states above the Fermi level. In our previous studies [23, 37], TPR-XANES investigations of a series of Pt/ceria catalysts having different Pt loadings and Ca doped Pt/ceria catalysts definitively identified that once Pt oxide reduction occurs, reduction of the ceria surface shell follows. The latter step was found to involve conversion of surface O to Type II bridging OH groups [17], with a corresponding change in oxidation state of the associated Ce atoms in the surface shell from Ce4+ to Ce3+. Moreover, a significant metal-support interaction was identified, in which systematic increases in Pt loading led to corresponding decreases in reduction temperature of the surface shell. For example, with a very high loading of 5%Pt, surface shell reduction occurred at just 200°C. When the same amount of platinum loading was introduced to calcium doped ceria supports, the broad peak of surface shell reduction shifted to remarkably lower temperatures (e.g., 200–250°C).

The Ce L III edge (L III = 5723 eV) was also examined for each catalyst over a series of reduction temperatures in flowing hydrogen. As displayed in Figure 1, the XANES line shapes of Ce3+ and Ce4+ oxidation states are very different. Peak C for Ce4+ has been assigned to absorption into the 5d level with no occupancy in 4f for either the initial or final state, and, while present in completely oxidized CeO2, it is virtually absent for Ce3+. The final state configuration may be written Ce [2p54f05d1] O [2p6]. The peak labeled B is split into at least two separate assignments [38, 39]. Peak B1, also present in the CeO2 sample (i.e., Ce4+), has been assigned to absorption into the 4f level in the final state. That is, in addition to an electron excited from the Ce 2p shell to the 5d shell, another electron is excited, coming from the valence band (i.e., the O 2p shell) to the Ce 4f shell, leaving a hole in the valence band. For the sake of brevity, the simplest final state configuration associated with B1 may be written Ce [2p54f15d1] O [2p5]. During reduction, peaks B1 and C decrease and a new peak, B0, develops, occurring just below that of B1, and associated with absorption into the 5d level, with 4f occupancy in the initial state. Its final state configuration may be written Ce [2p54f15d1] O [2p6]. The intensity of B0 is very high for any Ce3+ reference, with one example (cerous carbonate) provided in Figure 1. These key features (B0 for Ce3+ and both B1 and C as a fingerprint for Ce4+) were used to gain insight into the degree of reduction of the ceria catalyst component.

TPR-XANES trajectories of 0.5% platinum loaded undoped, La, Ba, Y, Hf, and Zn doped ceria catalysts are presented in Figure 2. The degree of reduction of ceria was quantified by carrying out a linear combination fitting of XANES spectra for treated catalysts with WinXAS [32], with reference compounds for Ce3+ and Ce4+ oxidation states, in the range of 5.69 and 5.75 keV. Results of the fitting procedure are shown in Figure 3. TPR begins with ceria presenting the Ce4+ oxidation state. The two steps of reduction (i.e., surface shell reduction and bulk reduction) of undoped ceria with 0.5% Pt, and surface shell reduction was complete (~20% of Ce as Ce3+) between 300 and 350°C as shown in Figure 3. In our previous investigation, [37] TPR-XANES of an undoped pure ceria identified that surface shell reduction was complete (~25% of Ce as Ce3+) between 450 and 500°C. Addition of Pt shifted the surface shell reduction but did not significantly impact the extent of ceria reduction or its bulk reduction. Ba, La, Y, Hf and Zn doped ceria samples display a decrease in reduction temperature and a significant increase in the extent of Ce reduction. For the Ba doped sample, the extent of Ce reduction is 25% as Ce3+ at 300°C, for the La doped sample, the extent of Ce reduction is 30% as Ce3+ at 300°C, and Zn doped sample it is 35% as the Ce3+ at 300°C, for Y doped sample it is found to be 40% as the Ce3+ at 300°C. Whereas for the Hf doped sample, the extent of Ce reduction is 80% as Ce3+ at 300°C. A similar decrease in the temperature of the surface reduction step was also observed in the case of zirconia [35] and calcium [37] doped ceria catalysts promoted with Pt and this was taken as evidence for an enhancement in surface O-mobility.

3.3 Catalytic Testing Using a Fixed Bed Reactor

Results of catalytic performance tests obtained over the Pt/Ce-Me-O catalysts are presented in Figure 4, where the conversion of CO (X CO) is plotted as a function of reaction temperature. The dopants have different effects on catalytic behavior of the modified Pt/CeO2 catalysts. It is observed that doping of Pt/ceria with Y, Hf, La and especially Ba, results in a shift of the conversion curves toward lower reaction temperatures, compared to the undoped catalyst. All catalysts were selective to WGS products (CO2 and H2). At 300°C, the CO conversion for the 0.5% Pt/CeO2 catalyst was 44% while CO conversion increases to 82, 86, 89 and 93% when the reaction was conducted over 0.5% Pt/Ce0.5La0.5O1.5, 0.5% Pt/Ce0.5Hf0.5O1.5, 0.5% Pt/Ce0.5Y0.5O1.5, and 0.5% Pt/Ce0.5Ba0.5O1.5 catalysts, respectively. Whereas, for the 0.5% Pt/Ce0.5Zn0.5O1.5 catalyst the CO conversion was found to be 18%, which is lower than the undoped Pt/ceria catalyst. These results are in good agreement with the results of other studies [23–26, 33–37], that the oxide support has a strong influence on the WGS activity. The implication is that Ba, Y, Hf, and La strains the lattice, improving the O-mobility. This in turn improves the mobility of O-bound intermediates which are proposed to form on the support and then migrate and decompose at the Pt–oxide interface. To test the viewpoint further, we turn to results of DRIFTS spectroscopy.

3.4 Diffuse Reflectance Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (DRIFTS)

As described in the experimental section, transient forward formate decomposition tests were carried out at 130°C and with only 3% H2O in order to slow down the decomposition so that comparisons could be made (Fig. 5). The band assignments for formate are well known [37]. Here, we are following bands in the formate ν(C–H) stretching region as opposed to those in the ν(OCO) region, since the latter overlap with the bending mode of H2O. The half-lives were found to vary inversely with CO conversion levels, suggesting that the decomposition of an associated intermediate such as formate may indeed be responsible for WGS catalysis. The trend was as follows: Zn-doped (249.0 min) > undoped Pt/ceria (80.4 min) > La-doped (56.2 min) > Hf-doped (37.1 min) > Y-doped (36.0 min) > Ba-doped (24.8 min). However, it should be noted that a bend was observed in the decomposition curve for the Y-doped sample, indicating that a fraction (i.e., in fact, a higher fraction) of the formates decomposed more rapidly. It is unclear at this time why this is the case, but possibilities include: (a) regions of the oxide may have enrichment of one oxide phase, leading to a fraction of less reactive formates; or (b) formates in particular regions of the oxide surface may be less accessible to Pt particles for decomposition. Furthermore, of all the catalysts screened, the Zn-doped catalyst, which displayed enhanced reducibility of ceria, exhibited lower formate decomposition and WGS rates. Again, this may be the result of surface enrichment by Zn oxide, or that the catalysts were not optimized for dopant loading.

4 Conclusions

Pt/ceria catalysts doped with specific cations (i.e., Ba, La, Y, Hf and Zn) were characterized by TPR-XANES and transient formate decomposition in order to determine whether dopant addition impacted reducibility (i.e., which in turns governs the temperature at which activation of the surface bridging OH groups takes place) and the mobility of formate, as O-bound associated species are proposed to be intermediates in the low temperature WGS reaction. TPR-XANES measurements showed that adding dopants to ceria do facilitate catalyst reduction, increasing extents of both surface shell and bulk reduction of ceria, and allowing bridging OH group formation to occur at lower temperature. CO adsorption was used to probe the active bridging OH groups to form formates. DRIFTS measurements of the transient decomposition of formates in steam at low temperature and low H2O concentration suggest that formate half-life follows the trend Zn > undoped ceria > La > Hf > Y > Ba, indicating that the formate decomposition rate is enhanced by the addition of most of the dopants tested. Low temperature water–gas shift activity showed good agreement with this trend, with activity following the order: Ba > Y > Hf > La > undoped ceria > Zn. Thus, the results suggest that dopant addition can significantly improve the WGS rate by facilitating catalyst activation and increasing the O-mobility of O-bound associated intermediates (e.g., formates). Moreover, the consequences are that lower amounts of Pt and Ce are required in the formulation to achieve comparable levels of activity.

References

Vielstich W, Lamm A, Gasteiger HA (2003) Handbook of fuel cells: fundamentals, technology, and applications. Wiley, Chichester

Song C (2002) Catal. Today 77:17–49

Koci P, Schejbal M, Trdlicka J, Gregor T, Kubicek M, Marek M (2007) Catal. Today 119:64–72

Koci P, Plat F, Stepanek J, Bartova S, Marek M, Kubicek M, Schmeisser V, Chatterjee D, Weibel M (2009) Catal. Today 147:S257–S264

Mannila P, Salmi T, Haario H, Luoma M, Harkonen M, Sohlo J (1996) Appl. Catal. B 7:179–198

Whittington B, Jiang C, Trimm D (1995) Catal. Today 26:41–45

Phatak AA, Koryabkina N, Rai S, Ratts JL, Ruettinger W, Farrauto RJ, Blau GE, Delgass WN, Ribeiro FH (2007) Catal. Today 123:224

Azzam KG, Babich IV, Seshan K, Lefferts L (2007) J. Catal. 251:163

Wang X, Gorte RJ, Wagner JP (2002) J. Catal. 212:225

Goguet A, Meunier F, Breen JP, Burch R, Petch MI, Chenciu AF (2004) J. Catal. 226:382

Fu Q, Deng W, Saltsburg H, Flytzani-Stephanopoulos M (2005) Appl. Catal. B 56:57

Wang X, Gorte RJ (2003) Appl. Catal. A 247:157

Kundakovic L, Flytzani-Stephanopoulos M (1998) Appl. Catal. A 171:13

Qi X, Flytzani-Stephanopoulos M (2004) Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 43:3055

Shido T, Iwasawa Y (1993) J. Catal. 141:71

Shido T, Iwasawa Y (1992) J. Catal. 136:493

Laachir A, Perrichon V, Badri A, Lamotte J, Catherine E, Lavalley JC, El Fallah J, Hilaire L, Le Normand F, Quemere E, Sauvion GN, Touret O (1991) J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 87:1601

Lamotte J, Lavalley JC, Druet E, Freund E (1983) J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 79:2219

Holmgren A, Andersson B, Duprez D (1999) Appl. Catal. B 22:215

Jacobs G, Patterson P, Williams L, Graham U, Sparks DE, Davis BH (2004) Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 269:63

Jacobs G, Chenu E, Patterson P, Williams L, Sparks D, Davis BH (2004) Appl. Catal. 258:203

Zalc JM, Sokolovskii V, LÖffler DG (2002) J. Catal. 206:169

Jacobs G, Graham UM, Chenu E, Patterson PM, Dozier A, Davis BH (2005) J. Catal. 229:499–512

Jacobs G, Davis BH (2007) Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 333:192–201

Jacobs G, Ricote S, Patterson PM, Graham UM, Dozier A, Khalid S, Rhodus E, Davis BH (2005) Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 292:229–243

Duprez D (2006) Catal. Today 112:17–22

Burch R (2010) Platinum Met. Rev. 54:137–146

Jacobs G, Davis BH (2010) Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 35:3522–3536

Andreeva D, Kantcheva M, Ivanov I, Ilieva L, Sobczak JW, Lisowski W (2010) Catal. Today 158:69–77

Yamamoto T, Suzuki A, Nagai Y, Tanabe T, Dong F, Inada Y, Nomura M, Tada M, Iwasawa Y (2007) Angew Chem Int Ed 46:9253

Jacoby M (2001) Chem Eng News 79(32):33–38

T. Ressler, WinXAS 97, Version 1.0, 1997

Jacobs G, Williams L, Graham U, Sparks D, Thomas G, Davis BH (2003) Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 252:107–118

Jacobs G, Ricote S, Graham UM, Patterson PM, Davis BH (2005) Catal. Today 106:259–264

Ricote S, Jacobs G, Milling M, Ji Y, Patterson PM, Davis BH (2006) Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 303:35–47

Jacobs G, Patterson PM, Calico-Williams L, Chenu E, Sparks DE, Thomas GA, Davis BH (2004) Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 262:177–187

Linganiso LZ, Jacobs G, Azzam KG, Graham UM, Davis BH, Cronauer DC, Kropf AJ, Marshall CL (2011) Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 394:105–116

Overbury S, Huntly D, Mullins D, Glavee G (1998) Catal Lett 51:133

El Fallah J, Boujani S, Dexpert H, Kiennemann A, Majerus J, Touret O, Villain F, Le Normand F (1994) J Phys Chem 98:5522

Acknowledgments

The work carried out at the CAER was supported in part by funding from the Commonwealth of Kentucky. Argonne’s research was supported in part by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Fossil Energy, National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL). The use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. MRCAT operations are supported by the Department of Energy and the MRCAT member institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Linganiso, L.Z., Pendyala, V.R.R., Jacobs, G. et al. Low-Temperature Water–Gas Shift: Doping Ceria Improves Reducibility and Mobility of O-Bound Species and Catalyst Activity. Catal Lett 141, 1723–1731 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10562-011-0720-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10562-011-0720-1