Abstract

Exploring romantic relationships is a hallmark of adolescence. As dating relationships are often new during this development trajectory, learning how to be in a relationship (e.g., learning healthy communication skills, etc.) is necessary to facilitate positive partnerships during the transition to adulthood. However, foster youth are a group routinely overlooked within the literature on developing positive and healthy relationships. This formative, exploratory study utilizes focus groups and in-depth interviews to understand foster youth perceptions of healthy and unhealthy dating relationships through a social learning theory lens. Findings explore foster youth perceptions of ideal relationships, the realities of their lived relational experiences, as well as the lessons learned that they would like to impart on future generations of foster youth. Implications for research, practice, and policy (e.g., the need for communication skill building, comprehensive sex and relationship education, as well as screenings for dating violence) are also explored.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adolescent Relationships

Relationship formation is a normative dimension of healthy adolescent development (Christopher, Poulsen, & McKenney, 2015). Over one-third of young people, ages 13–17, have been in an intimate, romantic relationship (Lenhart, Anderson & Smith, 2015). The formation of these relationships is a transition that occurs steadily, over time. During this transition, adolescents learn effective, pro-social patterns and skills that are necessary for dating (Christopher et al., 2015). According to social learning theory (Bandura & Huston, 1961), adolescents are able to learn the necessary skills by observing and interacting with significant others (e.g., adult role models with whom they have held a close attachment). For example foster youth who feel secure in their relationship with a caregiver are more likely to develop a healthy, intimate peer-based relationship (Rayburn, Withers, & McWey, 2017). Similarly, professional adults working in the field of youth development have proven integral to relationship formation among foster youth (Forenza, 2017), as have targeted, peer-based models of support (Scannapieco & Painter, 2014).

The skills that young people learn from significant others can translate into positive behaviors and qualities for later relationships (Madsen & Collins, 2011; Meier & Allen, 2009). This is important, as youth are more likely than not to have a relationship when they enter later adolescence (Lenhart et al., 2015). Furthermore, youth who are in serious relationships (partnerships) in later adolescence are more likely than not to be in a serious (e.g., cohabitating) partnership by early adulthood (Meier & Allen, 2009). As such, it is necessary to understand how youth engage in their early relationships in order to facilitate healthy and happy long-term partnerships.

When youth begin engaging in relationships, they often describe struggling to communicate and express themselves, despite feeling strong, genuine emotions for their romantic partners (Lenhart et al., 2015; Giordano, Longmore, & Manning, 2006). Females are more likely than males to engage in dating relationships during adolescence (Meier & Allen, 2009). Research suggests that males struggle more with communication in early relationships than females (Giordano et al., 2006; Rueda, Lindsay, & Williams, 2015). Some researchers have attributed this difference to the socialization of adolescent males to act in stereotypically masculine ways (Giordano et al., 2006). Further, in their study of Mexican-American youth in middle adolescence, Rueda and Williams (2016) noted that even adolescent couples in longer-term relationships struggled to communicate when attempting to resolve arguments. For instance, Rueda and Williams (2016) found that avoiding conflict, blaming a partner (or, conversely, taking the blame to end a conflict), and expressing feelings of helplessness, were commonly employed communication tactics for youth they studied.

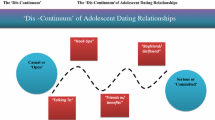

Even within relationship dissolution, adolescent couples struggle with communication, often letting relationships fade out instead of having a concrete ending (Lenhart et al., 2015). Fostering positive communication skills among adolescents is important work in helping to equip them with the best resources available to navigate subsequent relationships. However, it is also important to recognize that adolescents are not a homogenous group. There are many sub-populations within this pivotal demographic, including the aforementioned category of “foster youth” (youth living in out-of-home care).

Foster Youth Relationships

In 2015 over 600,000 children in the U.S. were served by public child welfare systems, with almost 270,000 entering the system that year alone (United States Administration for Children and Families, 2016). Despite the frequency of adolescents in care, little qualitative research has been conducted to explore their intimate relationship patterns. Much of the literature frames foster youth relationships in terms of risk behaviors (e.g., teen pregnancy among foster youth; Dworsky & Courtney, 2010; Oshima, Narendorf, & McMillen, 2013). This approach to understanding foster youth relationships is important, and the authors of the present study would never negate or whitewash the risk that foster youth have potential to experience. However, the present study aims to contextualize perceptions of healthy and unhealthy relationships from the perspective of foster youth themselves.

In addition to disproportionately high teen pregnancy, foster youth are also at increased risk for experiencing teen dating violence (TDV; Jonson-Reid, Scott, McMillian, & Edmond, 2007; Wekerle et al., 2009). Because of prior trauma, adolescents in foster care who experience TDV may be more vulnerable to negative health and mental health outcomes, such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and substance use, than adolescents who are not in care (Jonson-Reid et al., 2007). Research on other unique populations (e.g., Rueda & Williams, 2016; Rueda et al., 2015; Toews & Yazedjian, 2010) indicates that couples’ communication characteristics are often unique to in-group memberships. To date, little is known about relationship dynamics as they relate to the perception and experiences of foster youth.

Social Learning Theory

Broadly, social learning theory proposes that individuals learn values, beliefs, and behaviors from the individuals around them (Bandura & Huston, 1961). Youth learn how to behave in intimate relationships from those who are important to them (Bandura & Huston, 1961; Miller, Gorman-Smith, Sullivan, Orpinas, & Simon, 2009). Specifically, Miller et al. (2009) noted that adolescent boys exhibited positive (e.g., nonaggressive) relationship behaviors from significant others who modeled similar relationship behaviors. However, focusing on the larger contexts, not only the immediate surroundings, of those around the individual learning relationship values and behaviors is also critical (Johnson & Bradbury, 2015). Those who have experienced extreme poverty, pervasive levels of stress, and unsupportive social networks are less likely to learn healthy and constructive relationship behaviors (Johnson & Bradbury, 2015).

Foster youth, who are vulnerable to experience such conditions may have also experienced or witnessed maltreatment directly at the discretion of those they loved (Aparicio, Pecukonis, & O’Neal, 2015). Having experienced child maltreatment is illustrative of an unhealthy, albeit significant, relationship. Further, as noted by Johnson and Bradbury (2015) it is remiss to fail to look beyond these relationships in influencing later in life romantic relationship behaviors. A combination of aggressive modeling in relationships from family members or foster carers (Miller et al., 2009) as well as the potential for a social or community network to demonstrate negative relationship characteristics (e.g., dating violence; Arriaga & Foshee, 2004) might suggest poor significant others from which to learn dating behaviors. Indeed, The Midwest Evaluation of the Adult Functioning of Former Foster Youth found that foster youth fare worse than non-foster youth across a variety of outcome-oriented domains, including teen pregnancy (Courtney, Terao, & Bost, 2004).

Taking into account the importance of the significant others with whom the foster youth are able to interact (e.g., those who demonstrate positive relationship behaviors), as well as the context they are in, the creation of relationship education programs may be beneficial (Johnson & Bradbury, 2015). For instance, foster youth that have adult mentors report better overall health; they are less likely to report suicidal thoughts/behaviors, and are less likely to be diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection (STI) than those without adult mentors (Ahrens, DuBois, Richardson, Fan, & Lozano, 2008).

As such, targeted, positive relationship education can serve as a resource for many foster youth (Scott, Moore, Hawkins, Malm, & Beltz, 2012). In doing so, it can replace contexts that facilitate negative learning experiences concerning relationships with positive ones (Johnson & Bradbury, 2015; Purvis, Cross, & Pennings, 2009; Toews & Yazedjian, 2010). Still, little is known about how foster youth perceive and experience relationships (Scott et al., 2012). Given the dearth of knowledge surrounding foster youth relationships, it is difficult to create these opportunities that truly reflect these youth’s lived experiences and how they have come to understand and behave in their own relationships. Therefore, this present formative, exploratory study attempted to answer the following research question: What are perceptions of healthy and unhealthy relationships among youth aging out of foster care?

Method

Research Setting and Sample

Supportive housing programs can offer long-term, free- or reduced-rent, as well as easy access to helping professionals for focal consumer groups (SHNNY, n.d.). A core population served by one supportive housing program in the northeast corridor of the United States is foster youth on the cusp of emancipation from care or recently emancipated. Two freestanding buildings of the same umbrella agency provide the sampling frame for this research. One dorm-style building of this agency is dedicated to youth still completing their secondary educations; one studio apartment-style building is for youth who have recently emancipated.

Following IRB approval, an exploratory, qualitative study was conducted with the aim of discerning perceptions of healthy and unhealthy relationships among current and former foster youth (those in the process of emancipating and those recently emancipated). Youth from both buildings were invited to participate in this study (convenience sampling) via a recruitment flyer that was distributed to them through one of two, on-site housing supervisors. Both supervisors were unaffiliated with the principal investigator and this study; they were asked to distribute the flier by the agency’s executive director (also unaffiliated with this study, but a professional acquaintance of the principal investigator). All youth in the program were eligible to participate as long as they were 18 years old. A total of 16 youth (84.2% of eligible individuals) elected to join the study. They discussed their perceptions of healthy and unhealthy relationships via two focus groups (n = 5; n = 6), and individual interviews (n = 5). Although this is a relatively small sample size, other studies of foster youth concerning their relationships collecting data via focus groups have been utilized with similar sample sizes (Forenza & Lardier, 2017).

Of the 16 total participants, a majority was male (n = 9; 56%). Almost all (94%) identified as Black/African American. At the time of interview, three-quarters (n = 12) had been emancipated from care, while the remainder was still in the aging out process. Participants ranged from 19 to 21 years old (mean: 19.6; median: 20.0; mode: 19.5), suggesting a sample of what Arnett (2000, 2007) might call “emerging adults.”

Data Collection

The six-question interview guide asked participants to answer the following: (1) “What qualities do you look for in a friend?” (2) “What qualities do you look for in an intimate relationship?” (3) “What happens if someone breaks your trust? How do you deal with someone breaking your trust?” (4) “What makes a healthy dating relationship?” (5) “What makes an unhealthy dating relationship?” The sixth question called on participants to describe their dating experiences, and to impart their experiential knowledge about what other foster youth should know before engaging in intimate relationships. The same questionnaire was used for both in-depth interviews (n = 5) and each of the two focus groups (n = 11).

While it was never the principal investigator’s intention to collect data via different means (doing so was a matter of convenience for participants), utilizing in-depth interviews and focus groups did allow for methodological triangulation. Methodological triangulation occurs when two or more techniques are used to investigate the same phenomenon (Denzin, 1978). Procuring complimentary data through in-depth interviews and focus groups enabled the research team to minimize the potential weaknesses of either approach. For example, the in-depth interview is a hallmark of qualitative research: it helped to elicit a deep understanding of healthy and unhealthy dating relationships among foster youth. Focus groups, on the other hand, enabled the research team to observe interactions among group members, which was not possible to do in the in-depth interviews (see Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2009). Following guidelines from Krueger and Casey (2000), both focus groups were experientially homogenous; both consisted of five or six individuals.

Per IRB approval, no participant was allowed to be audio or video recorded. Consequently, the research team needed to take real-time, electronic transcription of in-depth interview and focus group responses, on laptop computers. Reciting quotes back to participants—reading directly from the real-time transcription—served as a form of member checking (Koelsch, 2013), though the researchers confess that some data was likely lost in this real-time note taking process. Finally, every participant received $20 for her or his time.

Qualitative Analysis

An inductive, thematic analysis was conducted on the real-time interview and focus-group transcripts. Per Braun and Clarke (2006), thematic analysis allows for both a rich and extensive exploration of topics described by participants. During open coding, the principal investigator and a doctoral research assistant separately read the real-time interview and focus group transcripts, in order to ensure their views did not influence each other’s interpretations of data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Both interviews and focus groups were read and coded concurrently, in order to understand the experiences of foster youth living in supportive housing as a single bounded group of participants (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). During this formative process, the team recognized and discussed the utility of applying a social learning theoretical lens to help develop the codebook.

After the codebook was developed, the team coded data, ensuring the codebook’s applicability to the dataset. As the same protocol was used for both focus groups and interviews, the codebook was appropriate for both. Therefore, the developed codebook was used to code both sets of transcripts. Following this, the team chunked the codes into larger categories, based on applicability to the research question (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). The research team met and, after substantive discussion, reached full consensus on the accuracy of data representation. This process resolved disagreements on data interpretation and added to the trustworthiness of analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Furthermore, the team aligned to Krueger and Casey’s (2000) recommendations for research using focus group data. As such, the team took into account the extensiveness and specificity of each code in addition to each code’s ability to provide a concrete example of an overarching theme and the emotionality of the participant offering it (Krueger & Casey, 2000). Due to the exploratory nature of the study, this provided the team with a more realistic interpretation of data.

During the entire coding process, the team was aware of the social context in which participants experienced their dating relationships (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). Although the team certainly did not assume all participants had experienced or violence or neglect in their pasts, they did consider a more ontologically holistic analysis that understood foster youth as being vulnerable to traumatic events (e.g., Aparicio et al., 2015; Manlove, Welti, McCoy-Roth, Berger, & Malm, 2011), which may have had the potential to affect their responses.

According to the social learning theoretical lens with which the authors undertook this study, it was important to take into consideration that the heightened risk for exposure to violent or aggressive relationship and communication styles (Miller et al., 2009). In taking account the specific experiences and contexts the team paid attention to these influences that may have an impact on the research question. However, it is equally important to note that to ensure trustworthiness, we also utilized reverse case analyses, which will be discussed further in depth below (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016).

In sum, throughout the coding process, the authors were sensitized to literature regarding the filial experiences and social environments of foster youth, which may have influenced the relationship skills of participants. Given the inductive nature of our analysis, it is critical to be sensitized to what may emerge based on theoretical underpinnings, regardless of an explicit inclusion or exclusion in an interview protocol (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016).

Trustworthiness

Through the entire analytic process, we utilized techniques for trustworthiness in order to ensure our interpretation of the data was valid. First, we triangulated the data between two separate researchers and then reconverged to discuss our interpretation (investigator triangulation; Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). In another form of triangulation, we were able to compare between two different forms of data, interviews and focus groups (Creswell & Miller, 2000; Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). We were also able to recognize, however, that our study was exploratory. Holliday (2013) suggests a study becomes more trustworthy when it makes transparent and realistic claims about its purpose. Furthermore, one of the authors had active engagement in supportive communities for foster youth and foster youth alumni (prolonged engagement in the field; Creswell & Miller, 2000). This allows for increased knowledge about the practices and views of those directly in the field (Creswell & Miller, 2000). We also utilized what Creswell and Miller (2000) refer to as “disconfirming evidence” (p. 127), or reverse case analysis. In doing so we examined the data for discussions that did not fit the codebook we had developed (Holliday, 2013; Merriam & Tisdell, 2016).

Findings

Findings from the thematic analysis presented seemingly contradictory results. However, upon further examination, these contradictions reveal the need for relationship education among foster youth. In discussing their definitions of ideal relationships, participants emphasized the paramount importance of good communication for healthy relationships. However, in discussing their own lived experiences, participants provided examples of struggling to communicate with intimate, romantic partners. Finally, in order to improve upon (1) theoretical understandings of idealized relationships, and (2) lived dating experiences for future generations of foster youth, participants in this study offered examples of concepts to be incorporated in tangible relationship education and prospective curricula.

Ideal Relationships: “A Healthy Relationship Is Communication”

Participants discussed their conceptualization and personal definitions of ideal relationships, noting above all that, “Communication makes a healthy relationship.” In other words, they valued open and honest communication between partners, which facilitated trust. For instance, one participant shared that “A healthy relationship is communication, trust, and being able to sacrifice equally. [Relationships also mean] compromising.” In turn, a lack of communication would foster feelings of distrust; a participant in a different focus group felt that, “Dishonesty [is] unhealthy.” A peer in the same group emphasized that “Being supportive [makes] a healthy relationship.” In order to note the importance of communication, a participant emphasized this when he provided an example of how to do so:

Sit down and talk with [your partner]. Whatever is making the relationship unhealthy, drop [it] like a bad habit. If you see some type of change and you see a difference [for the better] in your relationship, you keep working at it.

Similarly, another youth advised, “Keep it a hundred percent” (i.e., be completely open and honest). Yet another participant emphasized how he used open communication in the context of his own relationship:

A healthy relationship is not a perfect relationship. It’s gonna have arguments and fights. Hugs and kisses, curses, love letters. You need the bad with the good, or you won’t know the good is good. At the end of the day, when that first argument comes, that’s how you know how true the relationship is… For example, me and my girlfriend got into a fight and I didn’t want to talk to her anymore. I was getting upset. She broke down and cried and I left [and] went home. And then we talked about [what our specific problem was] and we missed each other. At the end of the day, I couldn’t see myself without her.

Interestingly, in interviews but not focus groups, youth juxtaposed the importance of good communication with discussions condemning communication breakdown, vis-à-vis dating violence. One young man felt that “Unhealthy [relationships] are abusive.” A second young man described that, “A healthy relationship is being caring, supportive, and trusting. You have to be all that for another person and they have to be that for you. An unhealthy relationship is one that is controlling, abusive, and disrespectful.”

The youth discussed their perceptions of what a relationship should be, often mirroring what is incorporated in relationship education for those in the general population, such as marriage therapy (e.g., open communication, an ability to have healthy arguments; Karam, Antle, Stanley, & Rhoads, 2015). However, these interventions have been critiqued through a social learning lens (see Johnson & Bradbury, 2015 for discussion) for failing to incorporate other conditions external to the relationship for a positive implementation. Indeed, the experiences the youth had in their own relationships indicated that although they may have been aware of the benefits of good communication, they may have had few significant others to model it for them.

Lived Experiences: “I Wouldn’t Even Tell Her That It Was Over”

Participant lived experiences, or their own histories of dating and partnerships, tended to differ from their ideals. Although foster youth in this sample described feeling that positive communication was the bedrock of an ideal relationship, they provided mixed evidence for being able to implement positive communication in their own lived experiences.

Initially, participants discussed how “[My partner and I] worked out a mutual agreement to start talking out our problems, and it has worked. Open communication has worked.” Another young woman recalled that, “[My partner and I] got together, we talked over it, tried to pinpoint the problems. We got back together and tried to change certain things.” However, many participants explained that they struggled to communicate in their own relationships. In both focus groups, participants agreed that they would attempt communication in some situations, but not in others. This idea was agreed upon unanimously in both focus groups, where it was independently and inductively explored. For instance, one participant suggested a desire to avoid conflict in her relationships. “I keep a positive vibe,” she said. “If you have positive vibes, there should be no problems,” she concluded, expressing a desire to avoid conflict. However, although certainly not unique to foster youth, healthy conflict and conflict resolution is a learned skill and one that can be taught (Karam et al., 2015; Toews & Yazedjian, 2010). It can be difficult to do so when coming from families where conflict resolution is taught via violence or aggression (Toews & Yazedjian, 2010). Certainly, within these discussions, some of these youth avoided conflict with their partners entirely. Focus group participants disclosed that their desire to communicate in some situations but not in others was the result of lessons learned from prior relationships. For instance, one participant noted that:

I [was in an] unhealthy relationship for 5 years and it didn’t go well for 5 years. I did everything I could to preserve it, and in that relationship I didn’t try to argue… I learned from that relationship because there were a lot of things that I had problems with, but I didn’t want to deal with them, because I didn’t want to lose [my partner]… I didn’t put on my big-boy pants. I just let it all go. In the relationship I’m in now, I said, “There will be no secrets with us,” and it’s going good. We tell each other everything. We talk to each other about everything.

However, as interview and focus group dynamics evolved, many participants described abandoning relationships altogether, although there was little disclosure as to why relationships were abandoned. When asked why she abandoned a relationship that she currently missed, one participant conceded that, “I’m still young, so I don’t know a lot about relationships.” This may have been due to how family relationships had been modeled from those they viewed as significant others, such as parents, foster carers, or close friends within the community. For instance, in a study by Toews and Yazedjian (2010), young adolescent mothers discussed struggling to conceptualize positive expectations about serious relationships and marriage due to how it had been modeled by their parents in their family of origin. For example, in the present study, when asked what they would do to fix a relationship, participants offered similar narratives that they would rather “Get out of it” or “End it.” Most participants described a desire to abruptly leave relationships that soured. One young man shared how he, “Walked away from it. I wouldn’t even tell her that it was over. She just didn’t see me anymore.” Another participant recalled, “Before, I used to just give people chances, but now I don’t know how to deal with [bad relationships], so I leave.”

Prospective Curricula: “Make Sure It’s the Right Person”

Finally, participants offered examples of valuable information that could be included in targeted education, designed to improve healthy relationships among youth in general, and foster youth specifically. Although participants had emphasized the importance of positive communication in creating and maintaining ideal relationships, few expressly addressed communication when hypothesizing prospective curricula. Instead, participants offered broad topics for instruction (e.g., “How to identify an unhealthy relationship,” “How to build a strong relationship foundation,” and “The pros and cons of sexual activity”).

Most participants described the importance of self-knowledge. For instance, one young woman advised, “Let [future generations of foster youth] have different scenarios where they get to know what they like in other people. Let them figure out what they want.” Another suggested, “Don’t change who you are for someone else.” Further, a participant indicated the importance of:

Knowing what [an individual] wants, but more than that- what they don’t want- so they can know if they’re in the right relationship. A lot of people are afraid to show their true self. They want to be what the other person wants them to be. [But] I want [my partner] to enjoy the relationship as much as they enjoy chocolate cake.

Other participants disclosed that knowing a prospective partner was integral to creating and maintaining a healthy relationship. “Make sure it’s the right person for you. It’s hard to let go and it’s hard to restart,” said one young woman. Another added, “Know the person before you jump into bed.”

A minority of participants, all in individual interviews, expressed that identifying manifestations of relationship violence and manipulative behaviors should be included in prospective relationship curricula for foster youth. In one focus group, a participant suggested, “Let [future generations of foster youth] know that cheating and lying and stealing is wrong.” Another young man, in an individual interview, wanted future generations to know, “How to identify abuse, and how to identify domestic violence.” Finally, a second young man also wished that future generations could recognize “How to know if someone is trying to control them and take advantage of them.” As such, it becomes important to include positive significant others (Arriaga & Foshee, 2004; Miller et al., 2009) to not only discuss, but to model respectful and nonviolent behaviors, particularly if these youths have been exposed to or have experienced violence.

Overall, participants emphasized positive communication as the bedrock of an ideal relationship; however, participants also described struggling to achieve positive communication in their own lived experiences. Specifically, they described terminating relationships in the face of conflict. Some participants offered examples of learning better communication from previous, unsuccessful, relationships. Finally, participants offered prospective content for relationship curricula to target future generations of foster youth.

Discussion

Summary

Overall, participants described similar conceptualizations of their ideal relationships (replete with positive communication); however, participants also reported varying levels of ability in implementing healthy relationship and positive communication skills. Such findings are not unexpected. Even among youth not in foster care, many young people struggle to implement effective communication skills (Giordano et al., 2006). One task of adolescence is to develop expectations and standards surrounding relationships (Christopher et al., 2015). Furthermore, learning how to effectively communicate within adolescent romantic relationships is normative and not exclusive to the experiences of youth in foster care (Giordano et al., 2006; Rueda & Williams, 2016). It can also be difficult for youth from families where aggression has been modeled, even if those youths have never been removed from those homes (Toews & Yazedjian, 2010).

According to the social learning theoretical lens with which the authors framed this study, having positive role models can foster the ability to navigate relationships in healthy ways (Miller et al., 2009). Given the transient living situations of many foster youth, however, this resource may not be consistently available to youth in ways it is to their peers not in care (Rutman & Hubberstey, 2016). For instance, 40% of the 43 foster youth in Rutman and Hubberstey’s (2016) study indicated they did not have some form of regular support to rely on. Regular interaction with a supportive and consistent caregiver facilitates both positive emotional development and offers opportunities to engage in healthy communication (Duke, Farruggia, & Germo, 2017). Despite this, some of the foster youth in the present study described learning from navigating their own relationships. In fact, some youth described ways in which they had improved upon their own communication style as a result of past relationships. This finding is in sync with other studies with youth from general (non-foster youth) populations (see Christopher et al., 2015).

Some participants, but not all, noted the importance of recognizing relationship violence as part of developing a relationship curriculum, in addition to recognizing it as part of an unhealthy relationship. Interestingly, foster youth in interviews, but not focus groups, discussed violence and abuse. Neither violence nor abuse were expressly probed for by interviewers, but both were nevertheless self-identified by participants. The tendency to only discuss this topic in one-on-one conversation, as opposed to a group setting, may be due to the sensitive and traumatic nature of the subject matter. This was a salient finding. Given the heightened vulnerability for youth in the foster system to have witnessed some form of family violence (see Aparicio et al., 2015), it is critical to identify violence and abuse with regard to prospective curricula developed for this population, as promotion of violence may legitimize violence in one’s own relationships (Miller et al., 2009).

As noted by Manlove et al. (2011), given the transitory nature of many foster youths’ living arrangements, they are further vulnerable to having experienced a number of traumas (e.g., physical and sexual assault). Trauma among foster youth has been linked to risky behaviors in later sexual relationships such as unprotected sex (Gonzalez-Blanks & Yates, 2015). All manifestations of experiences of violence in the lives of foster youth, such as those brought up by youth in this study, should therefore be addressed in culturally sensitive relationship education (Scott et al., 2012) as they have the potential to impact youths’ relational and sexual development.

Regardless of individual relationship experiences, participants in this study offered either (a) ways in which they wanted to improve their own relationship skills, or (b) ways to develop healthy relationship education. Providing foster youth with developmentally and culturally competent relationship education may offer youth the opportunity to learn healthy communication skills. Furthermore, by offering this education from mentoring adults, with whom foster youth may engage with in a pro-social capacity, offers examples of significant others who model positive communication behaviors (Duke et al., 2017; Purvis et al., 2009).

Despite the importance of creating healthy relationship education for foster youth, as indicated by participant discrepancies between relationship ideals and lived experiences, there remains a paucity of relationship education for this population (Scott et al., 2012). This formative, exploratory study lays the groundwork for further inquiry.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, the small sample is not representative of all youth emancipating from care. Findings are bound to the sample at hand: 16 young men and women who are part of an umbrella agency’s supportive housing program. Consequently, this sampling approach omits foster youth who live in other settings (e.g. kinship care, residential treatment, and/or traditional foster care). Even those in the sample have varying experiences in care, and their relationship perceptions/experiences are likely to be impacted accordingly. Additionally, the sample was procured through a program that subsidizes rent for emancipating and recently emancipated foster youth. Subsidized rent, which allows participants to live in supportive housing as she or he transitions to independent adulthood, is suggestive of a modest safeguard that should be afforded to all emancipating foster youth in the United States and beyond. However, not all foster youth benefit from this support, which suggests another bias of the sample. Additionally, participants may have been enticed to participate in this study because of the $20 remuneration, as opposed to a genuine desire to facilitate dialog around perceptions of healthy and unhealthy relationships among foster youth.

The researchers, largely informed by extant literature, also admit bias with respect to their conceptualizations of foster youth. With respect to the extraction of data: IRB constraints prohibited the principal investigator from audio or video recording participants; consequently, analysis was dependent upon real-time transcription on laptop computers. Finally, data collection in both focus groups tended to yield groupthink, as no group member in either focus group put forth a contrary opinion to what was being discussed at a given moment. On the bright side, however, the principle investigator observed both focus groups to be highly reactive and vocal when they agreed with an explicated concept. Additionally, in-depth interviews provided more nuanced and intimate discussions of relationships, yet a final limitation pertains to the fact that no express questions were asked about participant relationship histories (current or former). Despite these limitations, the authors believe that this formative, exploratory study has important implications for research, practice, and policy.

Implications

Research

As the present study was exploratory, the authors encourage future researchers to examine, in greater depth, the elements of relationships discussed by foster youth participants. For instance, participants discussed having difficulties communicating in their relationships and, instead of working through difficulties, participants often terminated relationships abruptly. A phenomenological analysis would be appropriate to investigate the mechanics of these self-reports. Similarly, some participants recalled how they drew upon their struggles with communication patterns in prior relationships to improve upon communication patterns in subsequent relationships. Research should investigate the mechanics of similar discussions to facilitate positive skill building among other populations.

Participants further described dating violence as both a negative aspect of relationships, as well as a topic for relationship education. Participant descriptions, in conjunction with the likelihood that they have been exposed to violence in their past (Aparicio et al., 2015), suggests that future research draw on intergenerational transmission of violence models (Kalmuss, 1984). These models can help us understand how the lack of communication strategies, in conjunction with exposure to violence and our social learning theoretical orientation, influences violence within one’s own relationship. Lastly, given the paucity of relationship education designed specifically for foster youth and their unique needs (Scott et al., 2012), this research should also be conducted specifically with the intent of developing empirically based and developmentally appropriate curricula.

Practice

In addition to research implications, findings from the present study also have important practice implications. For instance, the topic of the need for sex education was brought up in both focus groups and individual interviews. Given foster youths’ oft-cited early sexual debuts, as well as their vulnerability to become pregnant or impregnate a partner as an adolescent (Manlove et al., 2011), comprehensive sex education should be offered as part of the services provided to them. Structural constraints increasing the probability for pregnancy and parenting among foster youth makes the emancipation process difficult. Many foster youth leave care with minimal resources, including low educational attainment (Blome, 1997; Pryce & Samuels, 2010) and a desire for increased resources and social support (Mitchell, Jones, & Renema, 2015). Positive sexual relationships, such as those discussed by our participants may be learned in environments where healthy practices (e.g., consent, correct use of contraceptives) are modeled. However, sex education is only mandated in 24 states and Washington D.C.; 21 states require this education to include information on healthy sexual decision making. Only 13 states require that information provided in these courses be medically accurate (Guttmacher Institute, 2016). Policymakers in states that do not have comprehensive, safe, and accurate sexual education should reconsider these stances in order to stymie the heightened rates of pregnancy and parenting (Dworsky & Courtney, 2010) as well as STI rates (Ahrens et al., 2008) among foster youth and foster youth alumni through the use of contraceptives and other protections such as Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PReP).

Additionally, multiple participants described wanting to know more about dating violence. As such, practitioners (e.g., social workers, caseworkers, etc.) should be certain to screen foster youth clients for dating violence as well as provide information regarding how to identify and intervene when violence takes place. Given the emphasis that participants placed on knowing themselves as a vital aspect of relationship education, foster youth practitioners should work with clients to not only recover from traumas, but also to develop a more comprehensive understanding of individual wants and needs, as they relate to relationships. Thereby, any relationship education should be based as a trauma informed care model (Purvis et al., 2009). In using trauma informed care, practitioners would help to identify individual needs in regards to trauma and relationships. For instance, trauma informed care focuses on building trust through a safe environment with healthy, positive, and nurturing mentors who work specifically with each youth (Purvis et al., 2009). These mentors, who have been trained in this form of care, can engage with foster youth in understanding their own needs as well as be a significant other who models healthy relationship behaviors in a safe and nurturing environment.

Additionally, the emphasis that participants placed on knowing themselves and their needs, in conjunction with the number of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) youth in foster care (see Wilson, Cooper, Kastanis, & Nezhad, 2014), this work should be inclusive and appropriate to LGBTQ+ identified youth (Bermea, Rueda, & Toews, 2017). Research indicates healthy relationship needs, including those pertaining to dating violence, may not be met for foster youth in supportive housing (see Forenza & Bermea, 2017). Potential curricula as well as modeling (per adult mentors) should be mindful of appropriate and inclusive needs of all youth in care.

Policy

Finally, this study has implications for policy. First and foremost, participants emphasized the importance of communication in relationships, yet struggled to implement healthy communication in their own negotiations. According to our theoretical orientation, this discrepancy may be due to the aforementioned lack of role models that may be attributed to placement instability for the youth in this study. As such, policymakers should allocate funds for the development and implementation of relationship education for this population (e.g., the United States Health and Human Service Administration for Children and Families’ Healthy Marriage and Responsible Fatherhood Initiative).

Second, policymakers at the national level, such as senators, must recognize the need for relationship education for foster youth (Scott et al., 2012). However, little to no education for this population currently exists at this time (see Scott et al., 2012 for review), indicating there is no present model in its current form. Recognition by these policymakers would allow money and other resources not only to be allotted fund the development of programs, but also monies to evaluate its subsequent long-term outcomes (Scott et al., 2012). The benefits of doing so would not only measure the efficacy of these relationship programs (Scott et al., 2012), but also provide increased national resources to decrease the stress and strain that have been seen to act as a model for negative relationship behaviors (Johnson & Bradbury, 2015).

Lastly, given the transitory living arrangements of emancipating foster youth, such youth may not have opportunities to engage with adults who can model positive communication skills. Funding for groups and programs where foster youth have the opportunity to engage with supportive adults may provide healthy, formative relationships for foster youth to model from.

References

Ahrens, K. R., DuBois, D. L., Richardson, L. P., Fan, M. Y., & Lozano, P. (2008). Youth in foster care with adult mentors during adolescence have improved adult outcomes. Pediatrics, 121(2), e246–e252.

Aparicio, E. M., Pecukonis, E. V., & O’Neal, S. (2015). ‘The love that I was missing:” Exploring the lived experience of motherhood among teen mothers in foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 51, 44–54.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the early twenties. The American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480.

Arnett, J. J. (2007). Emerging adulthood: What is it and what is it good for? Child Development Perspectives, 1(2), 68–73.

Arriaga, X. B., & Foshee, V. A. (2004). Adolescent dating violence: Do adolescents follow in their friends’, or their parents’, footsteps? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19, 162–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260503260247.

Bandura, A., & Huston, A. C. (1961). Identification as a process of incidental learning. Journal of Abnormal & Social Psychology, 63(2), 311–318.

Bermea, A. M., Rueda, H. A., & Toews, M. L. (2017). Queerness and dating violenceamong adolescent mothers in foster care. Affilia: A Journal for Women and Social Work, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109917737880.

Blome, W. W. (1997). What happens to foster kids: Educational experiences of a random sample of foster care youth and a matched group of non-foster care youth. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 14(1), 41–53.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101.

Christopher, F. S., Poulsen, F. O., & McKenney, S. J. (2015). Early adolescents and “going out”: The emergence of romantic relationship roles. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 33(6), 814–834.

Courtney, M. E., Terao, S., & Bost, N. (2004). The Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: conditions of youth preparing to leave state care. Chicago: Chapin Hall Center for Children.

Creswell, J. W., & Miller, D. L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Into Practice, 39, 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2.

Denzin, N. K. (1978). The research act: A theoretical orientation to sociological methods. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Duke, T., Farruggia, S. P., & Germo, G. R. (2017). “I don’t know where I would be right now if it wasn’t for them:” Emancipated foster care youth and their important non-parental adults. Children and Youth Services Review, 76, 65–73.

Dworsky, A., & Courtney, M. E. (2010). The risk of teenage pregnancy among transitioning foster youth: Implications for extending state care beyond age 18. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(10), 1351–1356.

Forenza, B. (2017). Empowering processes of a countywide arts intervention for high school youth. Journal of Youth Development, 12(2), 21–41.

Forenza, B., & Bermea, A. (2017). An exploratory analysis of unhealthy and abusive relationships for adults with SMI living in supportive housing. Community Mental Health Journal, 53(6), 679–687.

Forenza, B., & Lardier, D. (2017). Sense of community through supportive housing among foster care alumni. Child Welfare, 95(2), 89–113.

Giordano, P. C., Longmore, M. A., & Manning, W. D. (2006). Gender and the meaning of adolescent romantic relationships: A focus on boys. American Sociological Review, 71(2), 260–287.

Gonzalez-Blanks, A., & Yates, T. M. (2015). Sexual risk taking among recently emancipated female foster youth: Sexual trauma and failed family reunification experiences. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26(4), 819–829.

Guttmacher Institute. (2016). Sex and HIV education. Retrieved December 1, 2016, from https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/sex-and-hiv-education.

Holliday, A. (2013). Validity in qualitative research. In C. A. Chappell (Ed.), The encyclopedia of applied linguistics. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

Johnson, M. D., & Bradbury, T. N. (2015). Contributions of social learning theory to the promotion of healthy relationships: Asset or liability? Journal of Family Theory and Review, 7, 13–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12057.

Jonson-Reid, M., Scott, L. D., McMillian, J. C., & Edmond, T. (2007). Dating violence among emancipating foster youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 29(5), 557–571.

Kalmuss, D. (1984). The intergenerational transmission of marital aggression. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 46(1), 11–19.

Karam, E. A., Antle, B. F., Stanley, S. M., & Rhoades, G. K. (2015). The marriage of couple and relationship education to the practice of marriage and family therapy: A primer for integrated training. Journal of Couple and Relationship Therapy, 14, 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332691.2014.100265.

Koelsch, L. E. (2013). Reconceptualizing the member check interview. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 12, 168–179.

Krueger, R. A., & Casey, M. A. (2000). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lenhart, A., Anderson, M., & Smith, A. (2015). Teens, technology, & romantic relationships. Pew Research Center. Retrieved November 8, 2016, from http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/10/01/teens-technology-and-romantic-relationships-introduction/.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Madsen, S. D., & Collins, W. A. (2011). The salience of adolescent romantic experiences for romantic relationship qualities in young adulthood. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(4), 789–801.

Manlove, J., Welti, K., McCoy-Roth, M., Berger, A., & Malm, K. (2011). Teen parents in foster care: Risk factors and outcomes for teens and their children. Child Trends Research Brief #2011-28. Retrieved May 4, 2016, from http://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/Child_Trends-2011_11_01_RB_TeenParentsFC.pdf.

Meier, A., & Allen, G. (2009). Romantic relationships from adolescence to young adulthood: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. The Sociological Inquiry, 50(2), 308–335.

Merriam, S., & Tisdell, E. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Miller, S., Gorman-Smith, D., Sullivan, T., Orpinas, P., & Simon, T. R. (2009). Parent and peer predictors of physical dating violence perpetration in early adolescence: Tests of moderation and gender differences. Journal of Clinical Child & Adult Psychology, 38(4), 538–550.

Mitchell, M. B., Jones, T., & Renema, S. (2015). Will I make it on my own? Voices and visions of 17-year-old youth in transition. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 32(3), 291–300.

Oshima, K. M., Narendorf, S. C., & McMillen, J. C. (2013). Pregnancy risk among older youth transitioning out of foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(10), 1760–1765.

Pryce, J. M., & Samuels, G. M. (2010). Renewal and risk: The dual experience of young motherhood and aging out of the child welfare system. Journal of Adolescent Research, 25(2), 205–230.

Purvis, K. B., Cross, D. R., & Pennings, J. S. (2009). Trust-based relational intervention: Interactive principles for adopted children with special social-emotional needs. Practice, Theory, and Application, 48(1), 3–22.

Rayburn, A. D., Withers, M. C., & McWey, L. M. (2017). The importance of the caregiver and adolescent relationship for mental health outcomes among youth in foster care. Journal of Family Violence. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-017-9933-4.

Rueda, H., & Williams, L. R. (2016). Mexican-American adolescent couples communicating about conflict: An integrated developmental and cultural perspective. Journal of Adolescent Research, 31(3), 375–403.

Rueda, H. A., Lindsay, M., & Williams, L. R. (2015). She Posted It on Facebook:” Mexican American adolescents’ experiences with technology and romantic relationship conflict. Journal of Adolescent Research, 30(4), 419–445.

Rutman, D., & Hubberstay, C. (2016). Is anybody there? Informal supports accessed and sought by youth from foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 63, 21–27.

Scannapieco, M., & Painter, K. R. (2014). Barriers to implementing a mentoring program for youth in foster care: Implications for practice and policy innovation. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 31(2), 163–180.

Scott, M. E., Moore, K. A., Hawkins, A. J., Malm, K., & Beltz, M. (2012). Putting youth relationship education on the child welfare attention: Findings from a research and evaluation review. Child Trends Research Brief #2012–47. Retrieved May 30, 2016, from http://www.childtrends.org/?publications=putting-youth-relationship-education-on-the-child-welfare-agenda-findings-from-a-research-and-evaluation-review-full-report.

Supportive Housing Network of New York. (n.d.). What is supportive housing? Retrieved November 28, 2017, from http://shnny.org/learn-more/what-is-supportive-housing/.

Teddlie, C., & Tashakkori, A. (2009). Foundations of mixed methods research: Integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Toews, M. L., & Yazedjian, A. (2010). “I learned the bad things I’m doing:” Adolescent mothers’ perceptions of a relationship education program. Marriage and Family Review, 46(3), 207–223.

United States Administration for Children and Families, Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System. (2016). Trends in foster care and adoption, state data tables. Retrieved November 28, 2017, from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/resource/trends-in-foster-care-and-adoption-fy15.

Wekerle, C., Leung, E., Wall, A. M., MacMillan, H., Boyle, M., Trocme, N., & Waechter, R. (2009). The contribution of childhood emotional abuse to teen dating violence among child protective services-involved youth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33(1), 45–58.

Wilson, B. D. M., Cooper, K., Kastanis, A., & Nezhad, S. (2014). Sexual and gender minority youth in foster care: Assessing the disproportionality and disparities in Los Angeles. Retrieved November 28, 2017, from http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/LAFYS_report_final-aug-2014.pdf.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This original research was approved by the appropriate Institutional Review Board.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Forenza, B., Bermea, A. & Rogers, B. Ideals and Reality: Perceptions of Healthy and Unhealthy Relationships Among Foster Youth. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 35, 221–230 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-017-0523-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-017-0523-3