Abstract

Parent involvement in children’s education is an important element in enhancing academic achievement and promoting positive behavior in young people. This qualitative study uses a Grounded Theory approach to examining parent’s perceptions of their ability or inability to be involved in their children’s education by querying about factors impacting involvement and their experiences overcoming barriers. A semi-structured interview guide was used to collect data on parents (N = 12) of youth who participate in a public housing after-school program by way of focus groups. Results suggest that parents are hopeful about engaging in education, but often fail to become actively involved because they feel marginalized. Furthermore, tangible barriers, a hurdle they were previously able to combat, was more challenging for them to overcome in the face of oppression. Marginalization is manifested cyclically for these parents. Implications for strategies helping parents become more involved in the educational process are identified.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The importance of parents becoming involved in their children’s education should be at the forefront of social concern if we hope to make strides towards academic excellence in America. There are vast implications for studying the impact of parental involvement. As studies increasingly identify it as successful marker of educational achievement among youth (Fan and Chen 2001; Van Voorhis 2003; Sui-Chu and Willms 1996; Griffith 1996; Jeynes 2005a) and as policies now incorporate provisions that include parental involvement (DePlanty et al. 2007), it is argued that parental involvement is a critical factor that may play a role in facilitating systematic change through the education sector (Hoover-Dempsey and Sandler 1995).

Parental involvement in children’s education has been shown to be associated with academic achievement and positive development (Fan and Chen 2001). Parental involvement is related to academic outcomes such as higher grades in science (VanVoorhis 2003), effects in reading scores (Sui-Chu and Willms 1996), and is positively associated with increases in standardized test scores (Griffith 1996; Jeynes 2005a). Active parental involvement is also a protective factor for school engagement among both elementary and secondary students, where youth excel when parents are frequently involved in their education (Jeynes 2005c; Gutman and Midgley 1999). It has been argued that youth are positively impacted when the link between school environment and home environment is consistent and cohesive (Epstein and Sheldon 2002; Sheldon and Epstein 2005). Specifically during youth development, with new complexities of social lives and increased responsibilities, a connected home-school environment is critical for successful educational outcomes (DePlanty et al. 2007; Bacete and Remirez 2001).

To assess parental involvement as it relates to positive outcomes, a deeper understanding of the nuances of involvement is needed. Parent involvement has been defined in a variety of ways. Some scholars have argued that it is the connection parents have with the school environment while others have suggested it is fostering academic success in the home. For example, some parents may not attend activities at their children’s school, but may choose to take an active role in homework or other community-based learning opportunities (Walker et al. 2010). In one study, parental involvement was defined as communication between the home and school, supporting learning at home, participating in school activities, and having a voice in decision-making practices within the administrative structure (Fantuzzo et al. 2004). Yet, in a meta-analysis of understanding factors related to parent involvement in education, several additional components were measured including parental expectations, parental interest in the educational process, parental supervision of homework, and attendance at school functions (Jeynes 2003).

Barriers to Involvement

It is clear there are various definitions explaining ways in which parents become engaged. Knowing this, there are several factors that influence parental involvement. Research has enumerated the challenges confronting parents who seek to engage in education, particularly those parents who live in high-risk communities (Eccles and Harold 1993). These challenges are often extensive and aren’t easy for parents to overcome, requiring strategies or skills they may not possess. The barriers are frequently beyond the control of parents and may be directly influenced by personal traits and characteristics.

Some evidence suggests that involvement may vary depending on race, ethnicity, and culture (Wa Wong and Hughes 2006), where minority parents, immigrant parents, or families deriving from a low socioeconomic status may be at a disadvantage and it may be impractical if not impossible to be involved. Also, the willingness for parents to be involved may have more to do with their physical, emotional, or intellectual capabilities rather than motivation or desire (Eccles and Harold 1993). Some parents find it relatively difficult and intimidating to engage when they feel they are a limited resource to their children (DePlanty et al. 2007). Undoubtedly, there are factors outside of the control of parents that impede their abilities to be involved. Therefore, it is increasingly important to consider why these barriers may prevent parents from becoming actively engaged in their child’s education.

Lack of Resources and Racial Considerations

Access to resources and opportunities often determine the level of participation parents will have (Muller and Kerbow 1993). One of the reasons parents may not be involved is related to socioeconomic status, where socioeconomic status has been suggested to be related to the degree to which parents are involved (Jeynes 2005b). For example, parents who earn a higher income and have advanced educational attainments have more engagement than parents with low socio-economic status (Lareau 2000). Meager financial resources and the lack of financial stability hinder parental involvement in school activities and can subsequently influence youths’ academic success (Menning 2002). Also, a lack of childcare, concerns about safety of the school/neighborhood, lack of transportation, and inability to leave work due to daytime meetings have all been identified as barriers to parental involvement (Muller 1995; Bengtson 2001; Turney and Kao 2009). Social networks may also play a role in determining parental involvement. Parents with extensive social network and community supports are more likely to have the resources necessary to take a more active role in education compared to parents with minimal social networks (Sheldon 2002).

Racial, cultural, and gender factors contribute differentially to parent involvement (Borg and Mayo 2001; Jeynes 2003; Jeynes 2005b). In a study of African American and Latino parents, parents reported feeling unwelcome at their children’s school and were 2.5 times less likely to attend school functions than White parents (Turney and Kao 2009). For immigrant and refugee parents, lack of language proficiency and meetings held only in English are reported frequently to be among the primary reasons parents do not attend school functions (Turney and Kao 2009). In addition, lack of understanding of the school structure and traditional gender or family roles and cultural attitudes pertaining to institutional authority also lead to reductions in interactions between parents and educators (Borg and Mayo 2001; Rah et al. 2009; Turney and Kao 2009).

Access to Technology

Limited access to technology creates additional barriers to parent involvement, particularly among low-income families (Hick 2006). It is no secret that technology has become the gateway through which knowledge acquisition has occurred and dissemination of ideas is delivered. Computer and technology knowledge among parents is an important skill because schools have increasingly become technologically savvy for the purpose of conveying information to students and parents (Hick 2006).

With the increase in the importance of computers and technology, many low-income families and parents lack access to these needed resources. In a recent nationwide survey of families, only 23 % of families in the lowest income quartile had access to both a computer and Internet services; 76 % of families in higher income quartiles had easy access to computers and the Internet (Hick 2006). Another survey found that poor youth were only .36 times as likely to have access to a home computer as same age non-poor youth (Eamon 2004). In a recent study aimed at exploring family technology use, computer access, and parental computer proficiency were found to be important factors in increasing parents’ interest in helping their children with homework (Lewin and Luckin 2010). Therefore, access to technology is a key element in helping parents feel more connected to schools and to their child’s educational process.

Youth Age

Parental involvement in their children’s education may taper off as youth age. Research has suggested that parents may not be as involved in their youth’s education as they age because of the commonly-held belief that parents often think their children may not require assistance with school work as they get older. Some parents believe that as youth age, they require less support from them as youth are now getting their educational needs met from the school and teachers (Drummond and Stipek 2004). Also, parents may assume that children are at an appropriate age where they are capable of completing schoolwork without parental guidance, monitoring, and assistance (Drummond and Stipek 2004).

This belief is frequently compounded by the fact that many parents lack adequate skills to help their children in their educational endeavors. Parents may become less involved in their children’s schools as educational content becomes more difficult during the middle and high school years (Eccles and Harold 1993). Parents may feel a high level of intimidation concerning the subject matter or the school, where they back away from assisting their children because they feel inadequate or ill equipped to help their child with homework or assignments (DePlanty et al. 2007).

Research Questions

Evidently, a number of individual and institutional barriers may reduce the likelihood of parent participation in children’s education. This manuscript suggests that parents face numerous barriers to taking an active role in their children’s education. To overcome these barriers, it is essential that parents and educators find ways to work together. An initial step in fostering a positive working relationship is to understand the nature and complexity of parent’s perceptions of their ability or inability to become involved in their children’s educational experiences at school and in the community. To this end, the current study uses a Grounded Theory approach in examining educational involvement from the perspective and voices of public housing residents. This qualitative study answered the following research questions: (1) What are the factors that impact parental involvement in their child’s education? and (2) How do parent’s overcome barriers to involvement?

Methods

Sampling and Procedures

In the early 1990s, the University developed a non-profit agency aimed at enhancing the academic success of children living in four low-income housing communities. In the Bridge Project, at-risk children receive tutoring, literacy programming, help with homework, and technology training. Youth who participate in the Bridge Project have demonstrated improvements in academic performance, school engagement and positive behavioral outcomes (Anthony et al. 2009). The program provides academic services to children ages 3–18. A site director, an on-site educator and an administrative assistant operate each site and graduate social work interns and community volunteers who provide tutoring and mentoring services support the sites. Parents are also welcome at the Bridge Project, but other than monthly family game nights, there is currently no programming specific to the parents.

The interest in examining parent involvement in children’s education came from a desire to better understand the barriers of involvement among parents whose children attend the Bridge Project. Thus, the decision was made to conduct focus groups with parents of Bridge Project participants at the program sites. The research was approved through the University’s Institutional Review Board to conduct this qualitative study. Although Bridge sites are in low-income communities, they vary in the cultural make-up of the community population, have fluctuating levels of parental involvement, and have been open to the neighborhoods for differing periods of time. There are a total four sites, but with guidance from program directors who could elucidate the level of parental involvement, two out of the four sites with the highest parental involvement were chosen.

Recruitment of participants took place from January 2010–March 2010. To participate in the study, individuals had to be parents of youth involved in the Bridge Project. Participant recruitment and sampling procedures occurred in several different ways. At the first location, the site director invited the research team to attend Family Fun Night, an opportunity for the parents to learn about the Bridge Project, interact with staff and play games with their children. At the Family Fun Night, the research team handed out recruitment flyers and spoke directly to parents about the study. A recruitment advertisement was also left with the staff to hand out to parents and was displayed in the main area of the site. As a result, six parents who were recruited through this process participated in the focus group held at this site.

At the second location, the site director introduced the research team to three parents who then served as an advisory committee to the research team. This committee offered suggestions on recruitment and interview questions, and helped with snowball sampling of other parents in the neighborhood. The research team also attended Family Fun Night at the second site. At this site, the researcher also directly spoke to parents and provided advertisements, while the parents from the parent advisory committee also helped speak to parents and hand out flyers. The evening of the focus group, the three parents from the advisory committee, as well as three additional parents, attended the focus group.

Through these sampling procedures, six participants were recruited for focus groups at each site with a total of (N = 12). At the site one, the group consisted of six participants, one Native American man, one Native American woman, one Caucasian woman and three Hispanic women. At the second site, the group consisted of six participants, one African American woman, one bi-racial woman and four Hispanic women. The racial and gender make-up of the groups was representative of the Bridge Project. The ages of participants’ school aged children ranged from 4 years old to 17 years old. The numbers of children living in the home ranged from one child to four children. The participants represented children in preschool, elementary school, middle school and high school. Each of the participants reported having attended school through the 12th grade, though not all of the parents report graduating. Several of the participants reported having attended “some college” but none reported having graduated from college. All of the parents reported that their children attended the afterschool program on a consistent basis.

Data Collection

As previously noted, focus groups served as the method for data collection. In a qualitative study such as this, focus groups have several advantages in gathering data, in that they typically have higher sample sizes, are cost efficient, and they are relatively easy to conduct (Rubin and Rubin 2005). In addition, focus group discussions allow for the ability to bring in new perspectives that were not originally considered (Krueger 1988; Morgan 1988). The interplay among participants not only stimulates thinking among them, it may also provide a community approach, which has shown to be empowering among oppressed groups (Rubin and Rubin 2005).

Each focus group was held at the respective Bridge site from which the parents were recruited. The groups were held in a private room, with only the parents and the research team present. The facilitators used interview guides to allow for more openness of responses than a structured interview schedule (Patton 2002). The interview guide was developed prior to the focus groups with questions guided by the literature and suggestions from key informants including both staff from the afterschool program and parents. Although the interview guides were used to suggest topics, each of the groups also had free flowing conversation in which the parents brought up new issues as well as using the comments of their peers to stimulate their own thinking. Both groups lasted about 90 min and were audio recorded. Each participant completed a handwritten survey that included demographic questions, their own educational experiences, and financial issues related to technology access and use. Each parent was compensated with a $10 grocery card for his or her participation.

Data Analysis

First Cycle Coding

The focus groups were audio taped and then transcribed. Also included in data analyses were field notes from the parent advisory meeting at site two and observations from family game night. Analyses began with open cycle coding as a means to begin to organize the data (Saldana 2009). The research team and one additional colleague trained in qualitative data analysis first coded the transcripts from site two. The three methods used were descriptive coding, in vivo coding, and structural coding (Saldana 2009). Descriptive coding facilitates a comprehensive understanding of the information in the data by subjectively reviewing the data and writing comments or other information found in the transcript (Saldana 2009, p. 70). The second method, in vivo coding is a method in which a short word or phrase directly from the participants is used as the code (Saldana 2009). This allows for use of “local language” (p. 74) and remains true to the exact statements of the participants (Saldana 2009). The third type of coding, structural coding is used for studies “employing multiple participants, standardized or semi structured data gathering protocols… to gather topics, lists or indexes of major categories or themes” (Saldana 2009, p. 66–67). These three distinct coding methods created a process that worked beneficially together and yielded similar results from all three coders. Given the similar results that were obtained using three different coders and three different coding methods, the resulting triangulation indicated support for the initial codes.

A similar process was used to code the transcripts from site one. The same three coders used a different first cycle coding method. For this document, descriptive coding was again used, as well as versus coding and process coding. Versus coding is a way of identifying and illuminating dichotomies in the data and in a manner that identifies any social injustices or polarizations of events, individuals, phenomenon, or circumstances (Saldana 2009, p. 94). Process coding is used to explore for action within the data, whether it is “simple observable activity” or “general conceptual action” (Saldana 2009, p. 77). The third code used was descriptive coding, as described above. Again, using three coders supported the accuracy of the codes. The first cycle coding methods began to reveal several different codes, which were then compared between the two documents. Once these codes were identified, the research team began creating rules and definitions for each of the codes (Lincoln and Guba 1985).

Second Cycle Coding

Once the rules were defined, the data were analyzed using second cycle coding. The goal of second cycle coding method was to organize and conceptualize the first cycle codes. Although second cycle codes aren’t always a necessary process, it was useful for this data in that it provided the researchers with a structured and beneficial way of reanalyzing the data and “developing a sense of categorical, thematic, conceptual, and/or theoretical organization from the array of first cycle codes” (Saldana 2009, p. 149). The transcripts, the codes and list of rules were analyzed by the two authors and three additional raters trained in qualitative analysis. The coders verified the data codes from the first cycle, and helped to conceptualize themes and networks from the data (Lincoln and Guba 1985). The method used for second cycle coding was theoretical coding, a method in which the emerging codes are grounded in the theory and literature (Saldana 2009). In theoretical coding, the code functions as “an umbrella that covers and accounts for all other codes and categories thus far formulated in the grounded theory” (Saldana 2009, p. 163). The codes and rules created through first cycle coding were combined with the existing literature about parental involvement to determine similarities or differences. Through this process, the data showed many similarities to existing literature about barriers, including what the research team called “tangible barriers.” This included codes such as lack of childcare, lack of transportation, and language barriers. However, the team also came across codes that were not directly stated in the literature including “jumping through hoops,” “children receiving the minimum,” and stigma associated with living in a low-income community. Combining these codes related to power differentials revealed a theoretical definition of marginalization.

Marginalization as defined by Brown and Strega (2005) is “context in which those who routinely experience injustice, inequality and exploitation through their lives” (p. 6). The parents clearly offered codes relating their experiences of inequality and injustice when attempting to deal with the school system. This term, marginalization, appeared to serve as the umbrella code needed to define the concepts emerging in using first cycle coding methods and provided a link between the theory and data.

Methods to Ensure Qualitative Rigor

To strengthen evidentiary adequacy, several forms of data were included in the analyses. Triangulation of data was achieved through documented through field notes, decision memos, and audio taping of the groups themselves. During the focus groups, in-session member checks were completed in which statements were clarified to ensure accuracy, and during completion of the sessions, common ideas were reviewed with the participants. Also, peer debriefing and support was used throughout data analyses to confirm agreement among the research team and other professionals. After the focus groups, the research team verified findings, using Bridge staff as experts, and during the coding process, the data continually revealed common themes, even with six separate coders working on the data.

Results

The coding processes resulted in findings that revealed one overarching category, called factors impacting parental engagement. This category contained five unique themes: tangible barriers, supports and resources, marginalization, jumping through hoops, and school choice. Each theme, the definition, examples, and quotes from participants are reported in Table 1.

Factors Impacting Parental Engagement

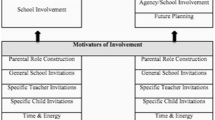

The category called factors impacting parental engagement is the idea represented by the participants as reasons they personally do or do not attend school events, help with homework or communicate with the school professionals. The category also includes any explanation or speculation from the parents as to why they believe other parents do not become involved; such as things other parents have told them or things they have personally witnessed within the school or community. This category revealed five unique themes that help explain how these factors interact with the process of parental involvement including: tangible barriers, supports and resources, marginalization, jumping through hoops, school choice. A conceptual schema, clarifying the salient themes and how they relate to each other is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Tangible Barriers

The first theme, tangible barriers were defined as any external task, activity or responsibility that makes involvement difficult. Codes included in this theme were time restrictions, lack of finances or lack of access to technology, lack of access to transportation, and language or cultural barriers. These barriers were considered by parents to be practical challenges that often stood in the way of involvement. Not having enough time, lacking finances, transportation, or access to technology were all concrete obstacles facing the majority of these parents. For example, one mother spoke of her employment as a reason she does not participate in school activities,

I am a single parent, well divorced. And umm I absolutely have to work. My schedule is during the week, while my kids are at school. So I don’t have that extra time to go you know to school parties or things like that.

Supports and Resources

Despite the fact that parents had a variety of tangible barriers or lack of resources, they tend to find ways to overcome these barriers on their own. The parents were able to draw on their resources and external supports to navigate around barriers. These barriers weren’t as difficult for families to circumvent because they could rely on their communities, agencies, family members, or other loved ones for support. As such, resources and supports act as mitigating factors to allow the parents to be involved in education despite these barriers. The theme, resources and supports was defined as anybody or anything that can help their child achieve an educational goal through helping the parent, such as teachers, or family support,

Well my parents help out, so I rely on my parent’s support. If I didn’t have my mom and dad… my dad can take the girls and then they don’t have to get up at four in the morning to go to work with me.

Community agencies were also coded as a support and resource. Parents were seemingly grateful to have the opportunity to depend on the Bridge Project for additional resources if they were needed. One mother explains, “they have the tutors at Bridge, so they can help with the things I don’t quite know.”

Marginalization

A third theme, marginalization, resulted from participant descriptions of frustration with the school system, even though they did not directly refer to them as barriers or reasons for lack of involvement. Marginalization was a meaningful theme that emerged where parents often felt ostracized and powerless to make a change in their child’s education. The impact of marginalization was so strong as it truly paralyzed those parents who sought to be involved. As defined by the literature, marginalization refers to the context in which people “routinely experience injustice, inequality and exploitation” (Brown and Strega 2005). The parents had a sense that they lacked power and control when making changes in their child’s education. The participants frequently used the words “minimal” and “dismissed,” and offered reports of feeling frustrated, feeling as though things were unfair or feelings, or stories related to feeling helpless or unable to make changes.

My daughter went from {an affluent school district} to {current school name} because I moved over here. She went there for a few months, from February to May, and during that time I had to call the main office to get the curriculum. I want to know the curriculum because my daughter was tracing ABCs at the end of the year at {current school} and was writing stories at the other school before. So, I couldn’t understand it. I called and asked… I need to have the curriculum. Shouldn’t they all have the same curriculum? Should they be tracing ABC’s while the other school is writing stories and publishing them and doing all this stuff that I brought over to the children. And they just dismissed you like, well… And now… they said it’s basically having the same curriculum. Then why is she learning something over here and tracing ABC’s over here? She knows how to do her ABC’s and write her name. She’s reading and they just dismissed me.

Parents often made attempts to be involved in their child’s education, and marginalization was frequently an unfortunate outcome. When discussing what happens if parents try to solve a problem with the school, one parent responded,

You’re dismissed, they tend not to listen to you because you don’t count, because you’re asking for help… because you’re asking for help. You’re not worthy of it, you don’t count, you know.

Parents often directly felt as if the school’s response was to dismiss them. Parents reported feeling that they were excluded from school activities, information, or not considered an asset as a result of their status. The parents were aware of the stigma related to living in a public housing community,

Because I feel that us being low income, poor people, working people, that we get dumped on a lot and we’re not heard and they dismiss us that we’re nothing.

Parents were also filled with fear when they would challenge authority. Feelings of fear would emerge when parents would try to question or resist the current mode of operation in the school systems,

So you know you don’t want to make waves, you don’t want to speak out, you don’t want to you know like, because you feel like oh my God I’m going to be ridiculed for the rest of my life… And it’s a scary thing, so you just have to really watch what you do. If you step on people’s toes…

Jumping Through Hoops

Several parents mentioned steps they have taken to try and assert their power, at times feeling like they have both the right and responsibility to stand up for their children. However, these attempts were often not successful. Jumping through hoops is defined as any attempt to solve problems and overcome the power differentials through the process of talking with several people or taking multiple steps, however, often not leading to any conclusion. The parents described several times when their complaints and frustrations went unsolved, despite going through the process of jumping through hoops. It was often a process of fruitless efforts to make changes, assert themselves, or challenge the system. Unlike the resources and supports, which mitigated the tangible barriers, jumping through hoops or trying to “work the system” instead proved to cause more frustration, more hopelessness and acted to reinforce the parents’ powerlessness and marginalization.

Now I understand why parents don’t say stuff, it’s like a process of like five or six days on the phone, meeting, calling, calling, meeting, to get anything done—It makes you want to just give up.

School Choice

The last theme is a mechanism that can help mitigate the power differentials felt by marginalization. The final theme was school choice and is defined as any statement related to being able to pick a child’s classroom, teacher, or school, and the resulting feelings of power and acceptance for making that decision. Parents had the choice as to where their child went to school, and this was a way parents were able to feel empowered, assert themselves, and demonstrate privilege. One parent described the importance of school choice,

I mean, you want your kids to be in the best schools so they have all the positive stuff…{former school} was off the wall, so now we’re changed to a different school. I love the new school… they have so many different things, so many kinds of culture, everything is so positive.

Participants who had an active choice about the school felt more welcome, reported the teacher to be more accessible, and believed their children were receiving a better education: “there was a vibe between me and the teacher, I can call her any time, e-mail her, call her, go in the classroom”.

Tangible barriers prevented parents from being able to access school of choice, thus often reinforcing the stigma of living in a low-income community. Although participants reported being able to overcome many barriers through their resources and networks, tangible barriers played a significant role when it came to school choice. In fact, tangible barriers were the primary reason many offered as to why they were not able to make use of the school choice option the school district provides.

My girls went to {name of private school} but had to change because I don’t have no more money to pay. When I first moved here, I put my girls in {private school} but then I hurt my back, so I had two operations, so I am not going to be able to work anymore, but my two daughters got uh… a scholarship for my girls, and then, then that finished and I didn’t have any money to pay, so I had to move them to the school that is close.

Some participants stated they would exercise school choice, but lacked the resources to make this happen. As one participant noted, “If I had a car or something, I would take him to a different school.”

Discussion

As demonstrated in the results section, the findings suggested that tangible barriers, such as lack of access to computers, lack of child-care, lack of transportation, or work responsibilities were all identified as barriers to involvement. However, the parents were able to navigate around these by demonstrating a remarkable ability to manage tangible barriers with the assistance of family, friends, and neighbors. Therefore, this study refutes current literature suggesting that tangible barriers encumber parental involvement. What was evident with the parents from this sample was that they were extraordinarily creative in their ability to solve problems that could be solved. For example, parents were able to gain access to computers through community agencies if they didn’t have one at home, arrange childcare or transportation as needed for school events, or find ways to help their children with homework. Because these parents valued education, solving logistical problems, although difficult at times, was important to them. So, it is unlikely that lack of resources is exclusively attributed to lack of involvement.

Instead, it appears as though the greatest barrier to parents’ ability to engage in their child’s education is marginalization. The parents’ low-income statuses caused them to feel fear, guilt, and shame, and consequently, they were less involved. Feeling alienated from society prompted them, in turn, to alienate themselves from their children’s educational institutions. The stigma associated with being low-income made parents fear “making waves”. Power differentials were clearly evident between the parents and society, with the parents feeling powerless due to their hierarchical placement. The parents attempted to address power differentials and feelings of helplessness through “jumping through hoops.” They would be required to combat numerous hurdles when asserting prowess in the school systems. The responses from the school system were often unconstructive and served to intensify feelings of shame. Therefore, jumping through hoops only reinforced feelings of powerlessness and marginalization.

During the process of theoretical coding, the concept of marginalization among parents was further explored. This process allowed the researchers to use a Grounded Theory approach to linking their findings back to current literature and investigate emergent themes that diverge from the literature. Concepts related to lack of child-care, lack of access to technology, lack of transportation, and language and cultural issues were present in the literature and identified as barriers to involvement in a child’s education.

However, the theme of marginalization as a barrier to parental involvement in education was scarcely highlighted in the literature. Rather than using the school based parental involvement literature, the researchers conducted a subsequent literature review related to life in low-income communities. The literature supported the assertion that parents living in low-income communities do feel marginalized and stigmatized (Farber and Azar 1999). This stigma interacts with the level of involvement in school in that public schools tend to reproduce or validate the existing dominant power dynamics of socioeconomic statuses (Abrams and Gibbs 2002). Parents positioned in the margins who “question or challenge authority or do not mirror the dominant middle class norms of the school are generally made to feel unwelcome” (Lareau 1987, 1989). When children fail in school, it is assumed that parents of lower socio-economic status don’t care about their children’s’ education (Farber and Azar 1999). Rather, it is not that parents do not want to be involved; the stigma associated with low-income status leads to a belief that “due to expectations related to middle class knowledge, they will not be respected among their children’s teachers” (Farber and Azar 1999).

This literature parallels findings from this study that reveal how marginalization of low-income individuals is perpetuated within public school systems. Feelings of marginalization ultimately impede parental involvement in the schools. However, this study adds to existing literature by identifying school choice as an avenue of overcoming feelings of marginalization. School choice allowed parents to exert power and dominance when they would otherwise feel ostracized by school communities. Nevertheless, tangible barriers often prevented parents from being able to choose schools for their children, tangible barriers, a hurdle they were previously able to combat, was more challenging for parents to overcome in the face of oppression. Accordingly, marginalization appears to manifest cyclically for these parents. They experienced very powerful marginalization, and when they attempted to employ skills to overcome it, it only seemed to be exacerbated, further highlighting how they are marginalized within society.

Implications for Practice and Policy

The findings suggest several implications for both future research and future intervention approaches Bridge Project staff has reported that previous intervention approaches attempted to assist parents with access to tangible resources have seen little participation. This lack of previous participation could be explained by the fact that these parents already know how to navigate through accessing resources. Instead, rather than trying to provide direct, tangible benefits, an innovative intervention approach aimed at deconstructing and resisting the power paradigm that propagates marginalization could be considered. This study suggests that giving parents some say or choice in the process is something that makes them feel more powerful, and can lessen the effects of marginalization. Facilitating parents in the decision making process and assisting with exerting a voice in their child’s education may be more useful in fostering involvement. Programs aimed at educating parents about school choice options, helping parents access school choice options, and helping them problem solve the tangible barriers preventing school choice may help parents feel more empowered and less marginalized.

Another potential intervention approach could be through using participatory action research. Through this process, the parents can decide how they will dismantle the existing dynamic. This method would be empowering and would allow the parents to have control over their situation. Through the participatory action, a communicative action strategy could also be developed. This would require parents to team up with the neighborhood and friends to seek social supports. Alongside their neighbors, they could take action in the schools through exerting their voices, and allowing themselves to be heard.

The findings also inform the current political climate with education reform at the forefront of recent political debates. The findings suggest that parents living in low-income communities feel ostracized and dismissed by school systems. It is clear that even with the establishment of de-segregation policies instituted in the education sector, there still exists a covert form of oppression among minority and low socio-economic families. Marginalizing these parents is a way to keep them from exhibiting power or authority, hinders youth success, and serves to isolate low-income communities. Therefore, it is critical to drastically overhaul the education system by providing those communities with the resources, supports, and empathetic administrators and teachers. Furthermore, fiscally re-distributing funds to low-income communities is necessary if America is striving for equality in educational opportunities. Allocating resources to low-income and minority communities in this way will truly advance the American dream of equal rights for all.

Limitations

The cross-sectional nature of data collected in this study is a limitation. Additional data points could have been obtained over time that included individual in-depth interviews, a review of the results reported by the parent advisory committee, and further recruitment of parents who are less involved in the Bridge Project. A second limitation relates directly to the focus group model. Because of the timing, significant breadth was captured. However, this format made it difficult to capture extensive depth in specific areas. Follow-up individual interviews would likely provide further information regarding the topics presented and strengthen the methodology. Additionally, similar to other studies, our investigation was not able to capture the voice of uninvolved parents. Studies that can access uninvolved parents are needed to better understand the experiences of a parent’s involvement in children’s education.

Conclusion

Parental engagement in a child’s education has been supported by literature to be important for future academic success, which was then supported by the results of this study. The findings suggest that parents within low-income communities do not get involved with their children’s education to the level they would like. Although previous literature linked lack of parental involvement to financial resources and tangible barriers, this study found that although related, were not the primary reasons parents were not involved. Instead, feelings of helplessness and marginalization appeared to be a much larger deterrent. One of the ways to address feelings of marginalization is through school choice. By allowing parents to know and exercise their choice options, they may be more likely to take an active role in their child’s education.

References

Abrams, L. S., & Gibbs, J. T. (2002). Disrupting the logic of home-school relations: Parent involvement strategies and practices of inclusion and exclusion. Urban Education, 37, 384–407.

Anthony, E. K., Alter, C. A., & Jenson, J. M. (2009). Development of a risk and resilience based out of school time program for children and youth. Social Work, 54, 45–55.

Bacete, F. J. B., & Remirez, J. M. (2001). Family and personal correlates of academic achievement. Psychological Reports, 88(2), 533–548.

Bengtson, V. L. (2001). Beyond the nuclear family: The increasing importance of multigenerational bonds. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 1–16.

Borg, C., & Mayo, P. (2001). From ‘adjuncts’ to ‘subjects’: Parental involvement in a working-class community. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 22(2), 245–266.

Brown, L., & Strega, S. (2005). Research as resistance: Critical, indigenous, and anti-oppressive approaches. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press/Women’s Press.

DePlanty, J., Coulter-Kern, R., & Duchane, K. A. (2007). Perceptions of parent involvement in academic achievement. The Journal of Educational Research, 100(6), 361–368.

Drummond, K. V., & Stipek, D. (2004). Low-income parents’ beliefs about their role in children’s academic learning. Elementary School Journal, 104, 197–213.

Eamon, M. K. (2004). Digital divide in computer access and use between poor and non-poor youth. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 31(2), 91–112.

Eccles, J. S., & Harold, R. D. (1993). Parent-school involvement during the early adolescent years. Teachers College Record, 94, 568–587.

Epstein, J. L., & Sheldon, S. B. (2002). Present and accounted for: Improving student attendance through family and community involvement. The Journal of Educational Research, 95, 308–318.

Fan, X., & Chen, M. (2001). Parental involvement and students’ academic achievement: A meta analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 13, 1–22.

Fantuzzo, J., McWayne, C., & Perrty, M. A. (2004). Multiple dimensions of family involvement and their relations to behavioral and learning competencies for urban, low-income children. School Psychology Review, 33(4), 467–480.

Farber, B. A., & Azar, S. T. (1999). Blaming the helpers: The marginalization of teachers and parents of the urban poor. American Journal of Orthopsychology, 69(4), 515–528.

Griffith, J. (1996). Relation of parental involvement, empowerment, and school traits to student academic performance. The Journal of Educational Research, 90(1), 33–41.

Gutman, L. M., & Midgley, C. (1999). The role of protective factors in supporting the academic achievement of poor African American students during the middle school transition. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29(2), 223–248.

Hick, S. (2006). Technology, social inclusion and poverty: An exploratory investigation of a community technology center. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 24(1), 53–67.

Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., & Sandler, H. M. (1995). Parental involvement in children’s education: Why does it make a difference? Teachers College Record, 97(2), 310–331.

Jeynes, W. H. (2003). A meta-analysis: The effects of parental involvement on minority children’s academic achievement. Education & Urban Society, 35(2), 202.

Jeynes, W. (2005a). Effects of parental involvement and family structure on the academic achievement of adolescents. Marriage and Family Review, 37(3), 99–115.

Jeynes, W. (2005b). The effects of parental involvement on the academic achievement of African American youth. The Journal of Negro Education, 74(3), 260–274.

Jeynes, W. (2005c). A meta-analysis: The effects of parental involvement on minority children’s academic achievement. Education and Urban Society, 35(2), 202–218.

Krueger, R. (1988). Focus groups: A practical guide to applied research. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Lareau, A. (1987). Social class differences in family–school relationships. Sociology of Education, 60, 73–85.

Lareau, A. (1989). Home advantage: Social class and parental intervention in elementary education. New York: Falmer Press.

Lareau, A. (2000). Home advantage: Social class and parental intervention in elementary education (2nd ed.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Lewin, C., & Luckin, R. (2010). Technology to support parental engagement in elementary education: Lessons learned from the UK. Computers & Education, 54(3), 749–758.

Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. London: Sage Publications.

Menning, C. L. (2002). Absent parents are more than money: The Joint effect of activities and financial support on youths’ educational attainment. Journal of Family Issues, 23(5), 648–671.

Morgan, D. (1988). Focus groups as qualitative research. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

Muller, C. (1995). Maternal employment, parent involvement, and mathematics achievement among adolescents. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 57, 85–100.

Patton, M.Q. (2002). Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd Ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing.

Muller, C., & Kerbow, D. (1993). Parent involvement in the home, school, and community. In B. Schneider & J. S. Coleman (Eds.), Parents, their children, and schools (pp. 13–42). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Rah, Y., Choi, S., & Nguyen, T. (2009). Building bridges between refugee parents and schools. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 12(4), 347–365.

Rubin, H. J., & Rubin, I. S. (2005). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing.

Saldana, J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing.

Sheldon, S. B. (2002). Parent’s social networks and beliefs as predictors of parent involvement. Elementary School Journal, 102, 301–316.

Sheldon, S. B., & Epstein, J. L. (2005). Involvement counts: Family and community partnerships and math achievement. The Journal of Educational Research, 98, 196–206.

Sui-Chu, E. H., & Willms, J. D. (1996). Effects of parental involvement on eighth-grade achievement. Sociology of Education, 69, 126–141.

Turney, K., & Kao, G. (2009). Barriers to school involvement: Are immigrant parents disadvantaged? Journal of Educational Research, 102(4), 257–271.

Voorhis, F. L. (2003). Interactive homework in middle school: Effect on family involvement and students’ science achievement. The Journal of Educational Research, 96, 323–339.

Wa Wong, S., & Hughes, J. N. (2006). Ethnicity and language contributions to dimensions of parent involvement. School Psychology Review, 35(4), 645–662.

Walker, J. M. T., Shenker, S. S., & Hoover-Dempsey, K. V. (2010). Why do parents become involved in their children’s education? Implications for school counselors. Professional School Counseling, 14(1), 27–41.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yoder, J.R., Lopez, A. Parent’s Perceptions of Involvement in Children’s Education: Findings from a Qualitative Study of Public Housing Residents. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 30, 415–433 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-013-0298-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-013-0298-0