Abstract

The purpose of the present study is to review empirical evidence of the effects of interventions designed to improve engagement in mental health services among adolescents, young adults and their families. Investigators searched relevant databases, prior reviews, and conducted hand searches for intervention studies that met the following criteria: (1) examined engagement in mental health services; (2) included a comparison condition; and (3) focused on adolescents and/or young adults. Effect sizes for all reported outcomes were calculated. Thirteen studies met inclusion criteria. Conceptualizations of engagement and measurement approaches varied throughout studies. Approaches to improving engagement varied in effectiveness based on level of intervention. Individual level approaches improved attendance during the initial stage of treatment. While family level engagement interventions increased initial attendance rates, the impact did not extend to the ongoing use of services, whereas service delivery level interventions were more effective at improving ongoing engagement. The review illuminated that engagement interventions framed in an ecological model may be most effective at facilitating engagement. Implications for future research and practice are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Client disengagement in the mental health system is most often defined in the literature as dropping out of services, skipping sessions, attrition, and/or premature termination. It is considered a significant obstacle to both effective service delivery and the efficacy and outcomes of treatments and services (Baydar et al. 2003; Meyers et al. 2002; Nye et al. 1999), as clients are less likely to improve if they are not fully engaged in care. Although service outcomes have received the bulk of attention at the policy level, at the practice level, workers struggle daily with the challenges of maintaining client engagement, defined in this paper as a continuum that includes initial contact, intake appointments, continued retention in treatment, along with investment in treatment by both the client and provider of services.

Service disengagement during the transition to adulthood creates unique developmental and service delivery challenges. Young adults are at a critical time for shifts in decision-making (McMillen and Raghavan 2009), developmentally, the transition-process is still happening, and the role of supportive others in their lives is changing. The movement from an adolescent- to an adult-oriented system, and more restrictive eligibility criteria for adult mental health services may create special obstacles to successful service engagement (Davis et al. 2006). The majority of those who enter outpatient treatment drop out quickly or make only a small number of visits to their providers (Harpaz-Rotem et al. 2004). For example, estimates regarding premature treatment termination range from 22 to 32% (Olfson et al. 2009). Also, attrition rates of initial intake appointments can range from 48 to 62% of youth accepted for an evaluation (Harrison et al. 2004). Furthermore, with respect to ongoing service engagement, estimates of average length of care have been documented as low as four sessions of service, or rates of as few as 9% of youth remaining in care after a 3-month period (McKay and Bannon 2004).

Although factors related to premature termination, attrition, or drop-out have been widely studied in adult populations (Armbruster and Kazdin 1994), fewer studies have examined risk factors related to disengagement among young adults (e.g. mistrust, lack of insight, emotional reactions, unmet need) (See Munson et al. 2011; Ialongo et al. 2004). We do not know of any studies that focus on reviewing interventions geared toward decreasing the influence of risk factors and increasing engagement among adolescents, young adults, and families. This paper hones in on examining the literature on engagement in mental health services among adolescents and young adults, along with their families. The paper focuses on studies of engagement interventions; that is, the focus on the intervention was to ameliorate the problem of client disengagement. Of note, intervention studies that examine engagement-type outcomes, but whose primary focus is not engagement are not included. For example, studies which analyze attrition and/or intent-to-treat within a larger outcome study are beyond the scope of this paper. This paper includes only studies whose primary aim was to investigate improved engagement outcomes.

The Concept of Engagement

Engagement is widely defined in the mental health literature with little consistency. As was suggested above, service engagement and other terms (e.g. attendance, adherence, retention, attrition, maintain service, drop-out, premature termination, and compliance) appear interchangeably in the literature. When client engagement emerges in empirical studies, conceptual definitions vary broadly and frequently refer to clients keeping appointments and staying in treatment (Littell et al. 2001). On the other hand, in the practice literature, the term engagement commonly refers to the early stage of activities with clients, whether the emphasis is on cooperation during sessions (Prinz and Miller 1994), emotional involvement in sessions and progress toward goals (Cunningham and Henggeler 1999), or some other aspect of the help-seeking process.

Researchers have conceptualized engagement in varying ways, capturing different dimensions on the continuum of engagement authors put forth above. For example, McKay et al. (1998) point out that engagement in mental health services has been divided into two specific steps: initial attendance and ongoing engagement. McKay and Bannon (2004) suggest that “the initial and ongoing stages are considered related to each other, but each one also appears as a distinct construct being independently related to characteristics of the client, the family, and the service system” (p. 906).

More recently, two additional researchers have moved forward thinking regarding engagement in services among children and families through examination of the literature, synthesis, and measurement development (i.e. Staudt 2007; Yatchmenoff 2005). First, Staudt’s (2007) review offers a number of important points on engagement, for example, articulating that engagement is an ongoing process that is dynamic and does not remain the same throughout the treatment process. Staudt goes on to describe two “components of engagement” (p. 185), namely behavioral and attitudinal. This analysis is useful in thinking about how engagement is something more than just making an appointment, a behavior, but that it is also about what one believes about treatment and whether they are invested in treatment, which she discusses as more attitudinal. A critical point here is that often social service professionals, and particularly researchers, account for engagement in care by measuring attendance, while professionals know that attendance alone does not equate to being engaged in treatment. There are barriers and facilitators to service engagement at all levels (Munson et al. 2011), whether one is measuring engagement through a behavioral and/or attitudinal lens.

Yatchmenoff added to the study of engagement by reviewing the extant literature on engagement in social work and developing a measure that can be utilized to examine engagement in social services, that is the Client Engagement in Child Protective Services measure (Yatchmenoff 2005). The dimensions of engagement included in the measure developed by Yatchmenoff expand conceptualizations of engagement to consider the sub-dimensions of receptivity, buy-in, the working relationship and level of trust/mistrust in providers/services (Yatchmenoff 2005).

Diverse definitions of the concept “engagement” exist in the literature. Conceptualizations depend on what aspect of engagement is being examined (e.g. client, worker, both), how is the aspect being measured, and is engagement being studied alone as an intervention, or is engagement being examined with other aspects of interventions, such as case management. The relationship between engagement and service outcomes can take many directions. Therefore, further empirical research is needed to examine overall engagement and the relationships between these aspects of engagement and outcomes to build knowledge in this critical area of inquiry.

Theoretical Framework

In the reviewed articles, four theoretical models were commonly utilized to inform engagement interventions. For example, the Health Belief Model (HBM, Rosenstock 1974) informed the interventions developed in a number of studies (e.g. Sawyer et al. 2002; Watt et al., 2007; Donohue et al. 1998; and McKay et al. 1996a). The HBM proposes that health behavior depends on both an individual’s perceptions of his/her vulnerability to an illness and his/her judgment of the perceived potential risk, barriers, or effectiveness of treatment (Elder et al. 1999). These factors are thought to influence medical decision making among individuals. Within the framework of health behavior theories, a reduction of environmental barriers is also linked to behavior change (Rosenstock 1974). These barriers could be either physical or psychological. For example, provision of financial incentives to not miss appointments and reduction of logistical barriers to attending appointments provide a strong link between environmental barriers and individual behaviors (e.g. service engagement).

Another common theoretical framework was Behavior Modification. According to Behavior Modification (Bandura 1969), one branch of learning theory, behaviors may or may not occur as a function of either performance or skill deficits (Elder et al. 1999). Performance deficits specify that the person knows how to perform a given behavior but chooses not to engage in the behavior because there are restricted positive consequences for doing the targeted actions (e.g. keeping appointments for therapy sessions) (Elder et al. 1999). In the case of those interventions, for example, motivational appointment reminder calls and incentives for attendance were provided to clients by providers as positive reinforcement for maintaining engagement. Reinforcement from providers for health behavior change is generally viewed positively and is likely to lead to individual health-behavior change (Elder et al. 1999).

Although some forms of family therapy are based on behavioral or psychodynamic principles, many engagement intervention studies (Szapocznik et al. 1988; Santisteban et al. 1996; Coatsworth et al. 2001) relied on concepts from Strategic and Structural Family Systems Theory to develop engagement interventions. The interventions were based on the premise that failure to engage in treatment is often because of dysfunctional family interactions. This approach regards the entire family, as the unit of treatment, and addresses such factors as relationships, interactions and communication patterns of a family rather than symptoms, or difficulties, in individual members (Szapocznik et al. 1988). Accordingly, this model is based on Minuchin’s (1974) principles of structural and systemic family therapy. These studies assume that the principles that apply to understanding family functioning and the treatment of dysfunctional families also apply to understanding and modifying the family’s resistance to engagement (Santisteban et al. 1996).

The ecological point of view leads to the identification of treatment barriers at multiple system levels, such as the individual, family, community, and agency (McKay et al. 1995b). McKay et al. (1995a) suggest that the ecological perspective illustrated that there are multiple barriers to services and failure to engage is not simply due to lack of client motivation or individual problems, but a combination of factors that exist on varying levels of the ecosystem. In Santisteban et al. (1996) study, they saw the ecological framework emerge for understanding the mechanisms by which cultural or environmental factors influence clinical processes that, in turn, moderate intervention effectiveness. In a variety of service delivery settings, many studies utilized an ecological framework where the origins of variation in engagement are identified at multiple levels (individual, family, organization, community, and public policy). These interventions are unique in that they are implemented within and across levels to reduce disengagement risks. The strength of the model is the ability to integrate salient factors at all levels of client ecosystem.

In addition to the four models, the therapeutic alliance is considered to be a salient common factor found in most mental health treatments and does not rely on a specific diagnosis or theory (Bickman et al. 2004; DeVet et al. 2003; Shirk and Karver 2003). The therapeutic alliance can be defined as the quality of the helping relationship, an emotional bond between the therapist and the client, the level of agreement between the two parties on the therapeutic tasks, and/or the agreement between the two parties on the expectations and goals of therapy (Bickman et al. 2004). For this reason, the strength of the relationship between the client and the therapist is a universal concern in the therapeutic process.

Study Purpose and Research Questions

Mental health service disengagement poses clinical, fiscal, and morale problems for mental health professionals, perhaps the most significant of which are reduced treatment efficacy, poor client outcomes, and decreased cost-effectiveness. The high rates of disengagement in children’s mental health care raises concern about every aspect of service delivery. This public health matter must continue to be a focus of systematic research efforts to assure the mental health of future generations. Lambert and Barley (2002) noted, even besides specific therapeutic technique factors, relationship factors (e.g. alliance, rapport, engagement) accounted for 30% of the variance in mental health treatment outcomes. Despite recognizing the salience of understanding engagement, relatively few studies have investigated engagement interventions and the relationship between engagement and outcomes. To date, the adolescent and young adult engagement literature(s) have not been systematic. Thus, the purpose of this paper is to critically review studies of interventions expressly designed to increase mental health service engagement among adolescents and young adults, synthesize findings, and identify knowledge gaps and future research needs. This study asked the following research questions: (1) How effective are individual level interventions in improving engagement in mental health service, (2) How effective are family level interventions in improving engagement in mental health service, (3) How effective are service system level interventions in improving engagement in mental health service, (4) Which interventions are most effective in improving engagement in mental health services, (5) Where does the research on engagement in mental health services among adolescents and young adults need to focus in future studies?

Method

Inclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria for the review were as follows: (1) intervention designed and evaluated, which specifically focused on engagement in mental health servicesFootnote 1 among adolescents and young adults; (2) mean age of participants between 10 and 25 yearsFootnote 2; (3) randomized-controlled trials (RCTs) with at least one comparison intervention; (4) examined individual or individual combined with family treatment(s); (5) were published in a journal or available as a dissertation from January 1988 to July 2010; and (6) were written in English. This review focuses only on studies of mental health service engagement interventions for adolescents, young adults and, in many cases, their families and does not include studies of engagement interventions for adult only populations.

Search Strategy

To obtain relevant studies, search methods made use of relevant databases, prior reviews, and hand searches of social work and mental health journals from a variety of allied disciplines. A computer search of English language articles using electronic databases EBSCO, MEDLINE, psychINFO and Social Sciences Index was conducted. The search words ‘engagement’, ‘retention’, ‘attrition’, ‘adherence’, ‘therapeutic alliance’, ‘premature termination’, ‘drop-out’, combined with ‘mental illness’, ‘community mental health’, and ‘adolescent’ and ‘young adults’ were used to identify relevant studies. Reference sections of previous reviews of service engagement were examined, and reference sections of identified studies were examined. A total of 1,949 titles were reviewed, and 499 articles were excluded based on title review. 1,450 abstracts were reviewed for inclusion. In this review process, studies were eliminated due to many factors, such as (a) adult samples, (b) not RCTs, (c) alcohol/drug abuse treatment alone, and (d) primary outcome of the intervention was not engagement. The 13 articles that met all search criteria were included in this review.

Effect Size Calculation Procedures

Examining effect sizes is a method of quantifying the effectiveness of a particular intervention relative to some comparison intervention. In this case, it quantifies the size of the difference between outcomes for two groups who received essentially the same treatment but in the context of different level(s) of intervention models. The authors closely read each study and identified the outcomes measured. Several studies assessed more than one outcome. In these studies, each outcome for which bivariate results were presented was included for effect size calculation. For each outcome, steps were taken to calculate Cohen’s d as a standard effect size of engagement intervention. While many measures of effect size are available, Cohen’s d has the advantages of being widely used, easily interpretable, and computationally applicable to a range of inferential statistics (Dunst et al. 2004).

When possible, we report the effect sizes that were reported in the articles. When effect sizes were not reported but sufficient data (i.e. frequencies or proportions experiencing an outcome, or values of Chi-square, t or F) was provided by the authors, we report effect sizes that we either calculated or estimated based on the results. We relied on online effect size calculators for most computations (Becker 1998, 1999; Wilson 2001; Lowry 2001–2009). For categorical outcomes, we calculated the values of Cohen’s d by hand, after obtaining values for Chi-square and sample size (Dunst et al. 2004). With this method, an effect size ≥0.8 is considered to be large, an effect size = 0.5 is considered to be medium, and an effect size ≤0.2 is considered to be small (Cohen 1988).

Results

Reviewed Studies

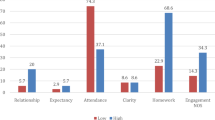

Thirteen published studiesFootnote 3 examining engagement interventions met criteria for the present study. Studies were organized by type of engagement intervention, namely individual level (e.g. interventions for client behavior change or barriers reduction), family level (e.g. intensive parent and youth attendance intervention), and service delivery level (e.g. therapist engagement strategies, different service delivery approaches). Each study was characterized in terms of sample size, method used to assign groups, and participant demographics (See Table 1). A summary of the studies’ sample composition and setting, intervention methods, measures, and outcomes is provided in Table 2. All of the interventions were RCTs with at least one comparison group. The desired outcomes of these interventions were to increase at least one aspect of engagement, such as attendance at treatment sessions and/or to improved investment in treatment. In Table 3, studies are grouped by the comparison condition as well as grouped by specific steps of engagement outcomes: initial and ongoing engagement.

Individual Level

Many of the individual level engagement interventions were based on Behavior Modification and the Health Belief Model. In the case of those interventions, positive reinforcement was given by providers for maintaining engagement. Any type of reinforcement from the providers for health behavior change was generally viewed positively and was likely to lead to health-behavior change. Reminder interventions implemented either during initial contacts with clients or before initial contact have been shown to boost service use. For example, supplying a simple reminder letter or phone call was widely used in the reviewed studies. The results suggest positive intervention outcomes, with small to moderate effects. Sawyer et al. (2002), reported the use of reminders significantly reduced the non-attendance rate from 20 to 8% among those randomized to the telephone group, when compared to those that did not receive a telephone reminder. Watt et al. (2007) also conducted a randomized, controlled trial that compared a control condition with telephone reminder interventions prior to the first five scheduled sessions. Findings suggested that the provision of reminders to children with high conduct problems improves initial attendance during the first sessions of treatment. While reminder calls also decreased attrition, the effect was not statistically significant. Reminder interventions were also utilized on some of the family combined level intervention studies (See McKay et al. 1996a, 1998, next section).

Family Level Footnote 4

Engagement interventions have also been designed to intervene at the family level. In relation to the theoretical perspectives discussed in the introduction, family level approaches were mostly based on the Strategic and Structural Family Systems Theory. Two of the six studies used Strategic Structural Systems Engagement (SSSE) as the intervention group. For example, Szapocznik et al. (1988) conducted an important study on the family level with Latino families of youth suspected of or observed using drugs. Participants were randomized to either SSSE intervention condition or engagement as usual (EAU) condition, which relies on the family itself to become more engaged over time. In the EAU condition, the therapist does not attempt to restructure the family’s resistance during the engagement process. Within the SSSE, the therapist analyzed the resistance type and implemented the appropriate theoretically based intervention. Within this approach, the behaviors of the therapist were grouped into six levels of engagement effort (e.g. level 0-expressing polite concern, making clear who must attend; level 5-higher level of ecological interventions, out-of office visits to family members to help in doing restructuring). For both conditions, the therapist was allowed to make as many contacts as needed within a 3-week period. If the family had not been present for admission after 3 weeks, the case was considered an engagement failure. The control condition was not a placebo group. Over 48% of the participants in the SSSE condition came to the center for intake. In contrast, only 20% in the EAU condition were engaged. Of all the cases that were initially assigned, 77% of subjects in the SSSE condition completed treatment compared with 25% of subjects in the EAU condition, and these were reported as significantly different (Szapocznik et al. 1988).

Santisteban et al. (1996) reported the efficacy of SSSE, which was designed to bring hard-to-reach youth and their family members into treatment. In this study, SSSE was evaluated with Hispanic adolescent drug abusers, who were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: (a) engagement family therapy (EFT), that is, family therapy plus SSSE; (b) family therapy (FT) without SSSE; and (c) group therapy (GT) without SSSE, respectively. The effectiveness of the intervention consisted of ratings of the engagement in therapy (i.e. having the family attend the intake session and one in-office therapy session within a 4-week period following initial contact) and maintenance in therapy (i.e. completing at least eight therapy hours and termination assessment battery) (Santisteban et al. 1996). Results indicate that SSSE increased attendance at the first appointments, but findings were mixed with regard to treatment retention. There were highly significant differences between the experimental condition (i.e. EFT) and the two control conditions (i.e. FT, GT) for rates of initial engagement. Namely, the SSSE strategy was associated with an initial engagement rate of 81%, compared with a 60% involvement rate for youth and families in the control condition (i.e. 57% of FT without SSSE, 62% of GT without SSSE). However, in terms of retention (e.g. dropout, termination), there were no significant differences between the experimental and control conditions; 69% in EFT, 67% in FT, and 63% in GT of the cases successfully terminated (Santisteban et al. 1996).

The SSSE studies all favor the intervention condition in measuring outcomes. SSSE compared to the control condition seemed to have a moderate to large positive effect in initial engagement. However, in terms of treatment termination outcomes, the two showed opposite effect sizes (0.05 and 1.15). It should be noted that Santisteban et al. (1996) reported the results based on the differences between the scores of experimental condition (i.e. EFT) and the mean scores of the two control conditions (i.e. FT, GT).

In two additional studies on family level interventions, McKay and colleagues utilized a thirty-minute telephone engagement intervention (McKay et al. 1996a) and a combined telephone engagement and first-interview engagement intervention with families (McKay et al. 1998). These interventions were compared to usual intake procedures for initial attendance and ongoing retention in children’s mental health services. The thirty-minute telephone intervention included the engagement and treatment procedures with the primary caretakers, for example, identifying their children’s difficulties, framing their actions as having the potential to have an impact on the current situation, having them take some concrete steps to address the situation even before the initial appointment, and exploring barriers to help seeking (McKay et al. 1996a; McKay et al. 1998). The combined condition included not only the telephone intervention, but also providing family therapists who had been specifically trained to focus on the process of engagement in the first interview with the client (McKay et al. 1998). Both of the engagement interventions from the two studies (i.e. combined telephone and first interview, telephone-alone) improved initial appointment keeping above and beyond services as usual with moderate to large effects. However, small effect sizes reveal that both interventions were not related to the perhaps more important ongoing use of services.

Donohue et al. (1998) compared two attendance interventions (Parent-focused attendance intervention vs. Intensive parent and youth attendance intervention) in a population of adolescents who were dually diagnosed with conduct disorder and substance abuse. Parents in both interventions received a detailed program orientation that included discussion of the parent’s concerns and the benefits of the program. However, one of the interventions also included the youth’s involvement, motivational appointment reminder calls, and incentives for attendance (e.g. promises to send letters to judges and probation officers depicting punctuality and attendance). The result of attendance rates revealed that significantly more patients in the intensive parent and youth intervention kept their first appointment (89%) than the parent-only attendance intervention (60%). In addition, the intensive intervention resulted in significantly greater attendance at the overall sessions as well (82.8 vs. 57.3%) (Donohue et al. 1998). These outcomes showed moderate to large effect sizes across initial to ongoing engagement stage.

Coatsworth et al. (2001) conducted an experimental design study in which participants were randomly assigned to either Brief Strategic Family Therapy (BSFT) or a Community Comparison (CC) condition. Adolescents with drug and alcohol problems, along with depression, anxiety, and behavior problems were assessed at two time-points, namely at intake prior to randomization, and at completion of treatment. The BSFT intervention used engagement and treatment procedures with three core strategies: Joining, Family Pattern Diagnosis, and Restructuring. In the CC condition, the typical practice was to offer either individual sessions to the adolescent or parent, and family sessions to all family members willing to participate. In contrast to BSFT, the CC condition did not have a consistent procedure for engaging reluctant family members. Successful engagement for both conditions was defined as the adolescent and at least one other adult family member attending both the intake interview/initial assessment and the first therapy session. Retention in treatment was defined as completing the course of treatment advised by the clinician. The result of engagement rates revealed that BSFT was significantly more successful in engaging cases (81%) than CC (61%). The retention rates in treatment revealed that, among those engaged, a significantly higher percentage of BSFT cases (72%) were retained when compared to CC (42%). The results suggest preferable intervention outcomes with moderate effects.

Service Delivery Level

Alternative approaches that address service delivery level variables during the course of treatment have evidenced improved treatment engagement. Service delivery level approaches were based on the ecological perspective. The ecological perspective leads to the identification of treatment barriers at different system levels McKay et al. (1995). Henggeler et al. (1996) identified that families of delinquent or psychoactive substance-abusing youth who received multisystemic therapy had a higher rate of treatment completion (98%) compared to families that received usual community outpatient services (22%) (i.e. weekly attendance at adolescent group meetings after completing a 12-step program). This ecological approach utilized by multisystemic therapy includes a comprehensive assessment of barriers to engagement and subsequent problem solving that focuses on the whole ecology of youths and families. These problem-solving approaches are used throughout the course of treatment. The outcome seemed to have the largest positive effect in increasing treatment completion rates.

McKay and colleagues trained therapists from an inner-city mental health clinic in a first-interview engagement intervention (McKay et al. 1996b). In this study, 107 new cases at an urban children’s mental health center were randomly assigned to a total of 20 therapists that were either trained first interviewers (experimental group) or therapists who did not receive specific engagement training (comparison group) (e.g. clarifying helping process, developing a collaborative working relationship, focusing on immediate, practical concerns, and problem-solving around barriers to help seeking) (McKay et al. 1996b). In the experimental group, 88% of the children came for a first appointment and of those 97% returned for a second appointment. In comparison, 64% of the clients assigned to the routine first interview condition came for an initial appointment and of those only 83% returned for a second appointment. During the 18-week study period, the proportion of sessions kept for experimental participants was 61.7%, as opposed to the proportion of 51% for the comparison group (McKay et al. 1996b). This result reveals that although there was no significant difference between the trained and not trained groups of therapists in the return rate, results indicate that the engagement training was associated with a statistically significant increase at the first appointment and in the overall proportion of sessions in which clients were maintained in care; effect sizes were low for initial engagement and moderate for ongoing engagement.

In addition to considering service delivery models of engagement, Burns et al. (1996) conducted a test of the impact of the addition of a case manager on engagement in care among youth with serious emotional disturbances and their families. The youth were served by a multiagency treatment team that was led by a case manager (experimental condition) or the youth’s primary clinician at the mental health center (control condition). Findings from baseline and 1-year follow-up interviews of 167 participants revealed that the youths with experimental case managers (67%) were more likely to remain in the program over the course of the year than were youths with a primary mental health clinician (38%) (Burns et al. 1996). During the first 4 months after program entry, both groups showed very little termination of service use. Starting at 5 months, however, the control group began showing substantial attrition from the program with a moderate effect size.

Karver et al. (2008) investigated associations among therapist engagement strategies, therapeutic alliance, client involvement, and treatment outcome. A randomized, clinical trial was conducted to compare the therapeutic alliance between cognitive behavioral psychotherapy (CBT) and nondirective supportive psychotherapy (NST) for adolescents with depressive symptoms who have attempted suicide. In the CBT sessions, engagement strategies such as presenting a treatment model, presenting a collaborative approach, and formulating goals were used. NST used unstructured sessions in which the therapists utilized exploratory questioning, encouragement of affective expression, feedback about changes in the client, and supportive statements. This study found that the level of therapeutic alliance accounted for treatment involvement across conditions. The treatment involvement was differentially related to treatment outcomes, with a large effect size, depending on treatment type. Specifically, an association appeared to be emerging in CBT but not in NST. This study suggests the therapeutic alliance may be an important factor for improving service use and engagement.

Grote et al. (2009) conducted a culturally relevant, enhanced brief interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT-B) intervention for low income, depressed new and expectant young adult mothers. Enhanced IPT-B is a multi-component model of care consisting of an engagement session (motivational interviewing and ethnographic interviewing), followed by eight acute IPT-B sessions before the birth, and maintenance IPT up to 6 months postpartum. During the engagement session, the interviewer elicits each participant’s unique barriers to care and engages in collaborative problem solving to ameliorate each barrier. IPT-B sessions were provided for helping patients resolve one of four interpersonal problem areas (i.e. role transition, role dispute, grief, and interpersonal deficits) related to the onset of a depressive episode. Also, biweekly or monthly maintenance IPT session was designed to prevent depressive relapse by helping participants deal effectively with the social interpersonal stressors associated with remission. Substantively, results suggest preferable the multi-component engagement intervention outcomes, with a large effect size, for low income, depressed new and expectant young adult mothers. 68% of mothers in the intervention group complete treatment, compared to 7% of control group (Enhanced usual care in treating depression) mothers.

Discussion

Four primary findings emerge from this review. First, reminder calls were an effective intervention strategy to increase engagement in the individual level (Sawyer et al. 2002; Watt et al. 2007). Individual level approaches improved attendance and reduced the likelihood of premature termination during the initial stage of treatment. The individual level approaches were based on the client’s perceptions and ability to perform behaviors and/or motivational concepts. Thus, approaches may want to focus attention on youth-friendly strategies to change negative thoughts and perceptions that youth and young adults may hold about treatment. Results revealed that the reinforcement or rewarding type interventions may temporarily work on initial attendance, but not impact ongoing engagement. Individual level interventions may be more effective if detailed Individualized Service Plans (ISP) are developed as a component of practice. Further, early on in treatment the client and worker may want to consider building in concrete and intermittent incentives to improve continued engagement in treatment, in order to keep up motivation to remain in treatment.

Second, most of the family level intervention results revealed that these engagement strategies increased initial and ongoing attendance in comparison to control groups. These interventions have proved to be a more effective method of increasing attendance at initial appointments than improving ongoing engagement. In the family level studies, the practitioners used interventions based on strategic, structural and systems concepts to involve the family and restructure family interactions to facilitate treatment engagement. In particular, the strategies (e.g. parents’ joining, family pattern diagnosis, and restructuring) strengthen parents’ ability to bring the adolescent to mental health services. Providers attempt to establish a working alliance with the caregivers and develop strategies that will help all family members attend appointments. From this point of view, family level intervention in mental health treatment requires a shift from conceptualizing the family as the source of the youth’s problem to viewing them as partners in care. In particular, for the young adults who are living with a partner, the service provider also inquires about their partners’ values and interests as well. Findings also suggest that the more time consuming activities of going out to the home of the family were not particularly effective (Santisteban et al. 1996). The providers often have a hard time reaching out to other family members who are defined as critical to successful involvement in services.

Third, several studies have shown that service delivery level approaches that focus on the various potential barriers to service engagement and the multi-layer and dynamic context of service delivery can increase substantially the attendance at initial appointments and ongoing service engagement. Almost all of the interventions studies attempted to understand service engagement are primarily based on the ecological perspective (McKay and Bannon 2004). The results of service delivery level interventions indicate that practitioners and organizations have a primary role to play in the engagement process (Cunningham and Henggeler 1999; Liddle 1995; McKay et al. 1995a; Santisteban and Szapocznik 1994). As many different types of service delivery level approaches (e.g. therapist engagement strategies training, adding case management) showed in this review, these interventions have proved to be a more effective method of increasing the rate of treatment completion than increasing attendance at initial appointments.

Fourth, depending on the clients’ developmental age, family context, family history, and mental health difficulties, the approaches varied in effectiveness. For example, for adolescents, group, family level and service delivery level interventions were more widely used than individual level approaches. For older youth and young adults, individual level and service delivery level interventions were more effective.

Implications

Indeed, service engagement barriers exist at multiple levels, including the individual, the family, the agency, and the environment (McKay et al. 1995a). From this review, it is evident that various approaches can improve the overall engagement in needed mental health services among adolescents and young adults, along with their families. Taking the current findings into consideration leads to several implications.

First, interestingly, outcome data on engagement interventions are difficult to interpret, due to variations in the definitions of what constitutes engagement. That is, different studies utilize different conceptualizations of engagement and also a variety of measurement strategies to measure the various dimensions of the construct. For example, the outcomes that were measured were initial appointment keeping, return rate for second and third appointment, treatment attendance more than a certain number of times, number of clients who came for their first scheduled intake appointment, proportion of appointments rescheduled or cancelled, and the number of appointments that were kept or skipped. This finding suggests that increased efforts need to be made to work toward consensus on how to systematically define the dimensions of engagement. Further, research efforts must hone in on developing gold standard measures to allow for better comparisons across studies.

Second, intervention design also varied significantly depending on the client’s stage of treatment and the age of the participants. However, there was little research comparing the various engagement interventions and results. Future research needs to utilize comparison studies for specific stage of treatment, such as clients who are new to the mental health system verses clients who have been involved in the system for long periods of time. Also, research may benefit from studies focusing on specific client groups, such as interventions for children/adolescents verses young adults. And, in addition, interventions that are promising need to be examined and compared to other approaches, as opposed to only comparing the engagement intervention to usual care. This will provide data on the most effective engagement interventions for future implementation efforts.

Third, the literature was almost non-existent on the engagement level of the practitioner. Engagement is influenced by the interaction between the client and the practitioner. Less engaged practitioners may result in a reduced level of engagement of youth and/or family members. As McKay et al. (1996b) study showed, practitioners’ training regarding engagement may improve their level of engagement as well as client engagement. The successful delivery of psychosocial interventions requires adequate staff training and ongoing supervision. We need a clearer understanding of this process in order to interpret the expected outcomes at different stages of work with client systems. Engagement levels among youth and professionals are instrumental to improving both the mental health and overall life outcomes of adolescents and young adults, along with their caregivers.

Fourth, many different barriers result in reduced access and engagement mental health care for clients. Many of these barriers are relatively fixed (e.g. socio economic status) or at least more difficult to influence. In contrast, organizational features such as service delivery type may be more easily modifiable. Organizational culture, which refers to basic assumptions, values, and behavioral norms and expectations found in an organization, affects work performance and organizational effectiveness by influencing the individual workers directly or indirectly (Aarons and Sawitzky 2006). These organizational features can promote clinical and system efficiencies that can substantially promote engagement of mental health care for adolescents and young adults.

Fifth, successful engagement might be dependent first on meeting a client’s basic needs. For example, for transition-age youth who “aged out” of foster care, mental health treatment may not be as important as shelter and food. An unemployed single mother living with mental illness may want to spend her time searching for a job, as opposed to navigating the mental health system. Interventions that operate across multiple levels of the ecosystem and link these levels (e.g. providing useful referral resource, cooperating intraorganizations) may be more effective and have greater reach into vulnerable populations than single-focus interventions.

Finally, few studies, as yet, focus on young adults, particularly young adults served by public systems of care. Developmentally, young adults often have become increasingly independent and often are heads of their own households. For these youth, who are increasingly making their own decision about mental health service engagement (McMillen and Raghavan 2009), engagement interventions that focus on cognitive aspects, such as the perceived advantages and disadvantages of mental health care, and social support as it relates to mental health treatment may become increasingly salient to overall engagement (See et al. “in revision”).

The literature on service engagement among youths in mental health treatment has several limitations in this study. First, since there is a paucity of studies on youth and young adults service engagement; only 13 studies met criteria for the present study, a limitation of these study findings is their generalizability. Second, there was no widely used standardized measure for mental health service engagement. Also, the engagement is part of the whole program and the measure of engagement depends on the other parts as well as the broader context of service. Many of reviewed studies utilized a unique measure of engagement (e.g. having family attend the intake session, number of session attendance) in the different types of program, which makes it difficult to compare results across studies. Another practical limitation in examining engagement in mental health services is that adolescents often come to the mental health service setting as a result of coercion (e.g. court orders), frequently do not understand why they need the services, and often have difficulties with rapport. It makes it hard to measure the level of engagement with good reliability in the intervention study.

Conclusion

The present study reviewed engagement interventions provided primarily to examine which level of intervention is most effective for improving engagement among adolescents and young adults. Anderson and Newman (1973) suggested that health care utilization is accounted for by several dimensions: (a) individual determinants (predisposition of the individual to use services, enabling factors, and illness level), (b) societal determinants (norms, technology), and (c) health services system factors (resources, organization). Health care utilization is a broader concept that considers service engagement over time, examining how likely an individual is to seek out, utilize, maintain in and invest in services. In that sense, to increase engagement, individual level, family level, and service delivery level intervention approaches may all be critical to address the disengagement problem. And, finally the review reveals that the future of research on mental health service engagement among adolescents, young adults, and their families should explore practitioner or organizational level factors that influence client, and practitioner engagement in the mental health service process.

Notes

In this review, the mental health services that were studied included outpatient, assertive community treatment, case management, community psychiatric support, intensive family-based, therapy, and counseling.

The studies included all had adolescents in the sample; some studies included children, but they were only included because they also included significant numbers of adolescents. We included studies with child and young adult participants so long as the mean age fell within this range.

“*” marked in reference section.

In some cases, family level interventions are combined with individual level.

References

Aarons, G. A., & Sawitzky, A. C. (2006). Organizational culture and climate and mental health provider attitudes toward evidence-based practice. Psychological Services, 3(1), 61–72.

Anderson, R., & Newman, J. (1973). Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilizationin the United States. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly, 51, 95–124.

Armbruster, P., & Kazdin, A. E. (1994). Attrition in child therapy. In T. H. Ollendick & R. J. Prinz (Eds.), Advances in clinical child psychology (Vol. 16, pp. 81–109). New York: Plenum.

Bandura, A. (1969). Principles of behavior modification. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Baydar, M. N., Reid, J., & Webster-Stratto, C. (2003). The role of mental health factors and program engagement in the effectiveness of a preventive parenting program for head start mothers. Child Development, 74(5), 1433–1453.

Becker, L.A. (1998, 1999). Effect size calculators. Retrieved July 30, 2011, from http://www.uccs.edu/*faculty/lbecker/.

Bickman, L., Vides de Andrade, A. R., Lambert, W. E., Doucette, A., Sapyta, J., Boyd, S. A., et al. (2004). Youth therapeutic alliance in intensive treatment settings. The Journal of Behavioral Health & Service Research, 31, 134–148.

*Burns, B. J., Farmer, E. M., Angold, A., Costello, E. J., & Behar, L. (1996). A randomized trial of case management for youths with serious emotional disturbance. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 25, 476–486.

*Coatsworth, J. D., Santisteban, D. A., McBride, C. K., & Szapocznik, J. (2001). Brief strategic family therapy versus community control: engagement, retention, and an exploration of the moderating role of adolescent symptom severity. Family Process, 40, 313–332.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Cunningham, P. B., & Henggeler, S. W. (1999). Engaging multiproblem families in treatment: Lessons learned throughout the development of multisystemic therapy. Family Process, 38, 265–286.

Davis, M., Geller, J. L., & Hunt, B. A. (2006). Within-state availability of transition-to-adulthood services for youths with mental health conditions. Psychiatric Services, 57, 1594–1599.

DeVet, K. A., Young, K. J., & Charlot-Swilley, D. (2003). The therapeutic relationship in child therapy: perspectives of children and mothers. Journal of Clinical and Adolescent Psychology, 32, 277–283.

*Donohue, B., Azrin, N. H., Lawson, H., Friedlander, J., Teichner, G., & Rindsberg, J. (1998). Improving initial session attendance of substance abusing and conduct disordered adolescents: A controlled study. Journal of Children & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 8(1), 1–12.

Dunst, C. J., Hamby, D. W., & Truvette, C. M. (2004). Guidelines for calculation effect sizes for practice-based research syntheses. Centerscope: Evidence-Based Approaches to Early Childhood Development, 3(1), 1–10.

Elder, J. P., Ayala, G. X., & Harris, S. (1999). Theories and intervention approaches to health-behavior change in primary care. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 17(4), 275–284.

*Grote, N. K., Swarz, H. A., Geibel, S. L., Zuckoff, A., Houck, P. R., & Frank, E. (2009). A randomized controlled trial of culturally relevant, brief interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal depression. Psychiatric Services, 60, 313–321.

Harpaz-Rotem, I., Leslie, D. L., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2004). Treatment retention among children entering a new episode of mental health care. Psychiatric Services, 55(9), 1022–1028.

Harrison, M., McKay, M., & Bannon, W. (2004). Inner-city child mental health service use: The real question is why youth and families do not use services. Community Mental Health Journal, 40, 119–131.

*Henggeler, S. W., Pickrel, S. G., Brondino, M. J., & Crouch, J. L. (1996). Eliminating (almost) treatment dropout of substance abusing or dependent delinquents through home-based multisystemic therapy. American Journal of Psychiatry, 153, 427–428.

Ialongo, N., McCreary, B. K., Pearson, J. L., Koenig, A. L., Schmidt, N. B., Poduska, J., et al. (2004). Major depressive disorder in a population of urban African–American young adults: Prevalence, correlates, comorbidity and unmet mental health service need. Journal of Affective Disorders, 79, 127–136.

*Karver, M., Shirk, S., Handelsman, J. B., Fields, S., Crisp, H., Gudmundsen, G., et al. (2008). Relationship processes in youth psychotherapy: measuring alliance, alliance-building behaviors, and client involvement. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 16(1), 15–28.

Lambert, M. J., & Barley, D. E. (2002). Research summary on the therapeutic relationship and psychotherapy outcome. In J. C. Norcross (Ed.), Psychotherapy relationships that work: Therapist contributions and responsiveness to patients (pp. 17–32). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Liddle, H. A. (1995). Conceptual and clinical dimensions of a multidimensional, multisystems engagement strategy in family-based adolescent treatment. Psychotherapy, 32, 39–58.

Littell, J. H., Alexander, L. B., & Reynolds, W. W. (2001). Client participation: Central and under investigated elements of intervention. Social Service Review, 75, 1–28.

Lowry, R. (2001–2009). Chi-square, Cramer’s V, and Lambda for a rows by columns contingency table. Retrieved July 30, 2011, from http://faculty.vassar.edu/lowry/tabs.html#csq.

McKay, M., & Bannon, W. (2004). Evidence update: Engaging families in child mental health services. Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 40, 1–17.

McKay, M. M., Bennett, E., Stone, S., & Gonzales, J. (1995a). A comprehensive training model for inner-city social workers. Arete, 20, 56–64.

McKay, M., Gonzales, J., Stone, S., Ryland, D., & Kohner, K. (1995b). Multiple family therapy groups: A responsive intervention model for inner city families. Social Work with Groups, 18, 41–56.

*McKay, M. M., McCadam, K., & Gonzales, J. (1996a). Addressing the barriers to mental health services for inner city children and their caretakers. Community Mental Health Journal, 32, 353–361.

*McKay, M. M., Nudelman, R., McCadam, K., & Gonzales, J. (1996b). Evaluating a social work engagement approach to involving inner-city children and their families in mental health care. Research on Social Work Practice, 6(4), 462–472.

*McKay, M. M., Stoewe, J., McCadam, K., & Gonzales, J. (1998). Increasing access to child mental health services for urban children and their caregivers. Health Social Work, 23, 9–15.

McMillen, J. C., & Raghavan, R. (2009). Pediatric to adult mental health service use of young people leaving the foster care system. Journal of Adolescent Health, 44, 7–13.

Meyers, R. J., Miller, W. R., Smith, J. E., & Tonigan, J. S. (2002). A randomized trial of two methods for engaging treatment-refusing drug users through concerned significant others. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 1182–1185.

Minuchin, S. (1974). Families and family therapy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Munson M. R., Jaccard J., Smalling S., Kim H., & Werner, J. (in revision). Static, dynamic, integrated, and contextualized: A framework for understanding mental health service utilization among young adults. Journal of Adolescent Research.

Munson, M. R., Scott, L. D, Jr, Smalling, S., Kim, H., & Floersch, J. (2011). Young adult psychiatric services: Complexity, routes to care, insight, and mistrust. Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 2261–2266.

Nye, C. L., Zucker, R. A., & Fitzgerald, H. E. (1999). Early family-based intervention in the path to alcohol problems: Rationale and relationship between treatment process characteristics and child and parenting outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, suppl 13, 10–21.

Olfson, M., Mojtabai, R., Sampson, N. A., Hwang, I., Druss, B., Wang, P. S., et al. (2009). Dropout from outpatient mental health care in the United States. Psychiatric Services, 60(7), 898–907.

Prinz, R. J., & Miller, G. E. (1994). Family-based treatment for childhood antisocial behavior: Experimental influences on dropout and engagement. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 645–650.

Rosenstock, I. M. (1974). Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Ed Monographs, 2, 328–335.

Santisteban, D. A., & Szapocznik, J. (1994). Bridging theory, research and practice to more successfully engage substance abusing youth and their families into therapy. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse, 3, 9–24.

*Santisteban, D. A., Szapocznik, J., Perez-Vidal, A., Kurtines, W. M., Murray, E. J., & LaPerriere, A. (1996). Efficacy of intervention for engaging youth and families into treatment and some variables that may contribute to differential effectiveness. Journal of Family Psychology, 10(1), 35–44.

*Sawyer, S. M., Zalan, A., & Bond, L. M. (2002). Telephone reminders improve adolescent clinic attendance: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Paediatrist Child Health, 38, 79–83.

Shirk, S. R., & Karver, M. (2003). Prediction of treatment outcome from relationship variables in child and adolescent therapy: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 452–464.

Staudt, M. (2007). Treatment engagement with caregivers of at-risk children: Gaps in research and conceptualization. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16(2), 183–196.

*Szapocznik, J., Perez-Vidal, A., Brickman, A. L., Foote, F. H., Santisteban, D., & Hervis, O. (1988). Engaging adolescent drug abusers and their families in treatment: a strategic structural systems approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(4), 552–557.

*Watt, B. D., Hoyland, M., Best, D., & Dadds, M. R. (2007). Treatment participation among children with conduct problems and the role of telephone reminders. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16, 522–530.

Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis effect size calculator. Retrieved July 30, 2011, from http://www.campbellcollaboration.org/resources/effect_size_input.php.

Yatchmenoff, D. K. (2005). Measuring client engagement from the client’s perspective in nonvoluntary child protective services. Research on Social Work Practice, 15(2), 84–96.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, H., Munson, M.R. & McKay, M.M. Engagement in Mental Health Treatment Among Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 29, 241–266 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-012-0256-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-012-0256-2