Abstract

Purpose

Comprehensive cancer control (CCC) coalitions and programs have delivered effective models and approaches to reducing cancer burden across the United States over the last two decades. Communication plays an essential role in diverse coalition activities from prevention to survivorship, including organizational and community capacity-building and as cancer control intervention strategies.

Methods

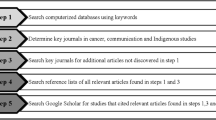

Based upon a review of published CCC research as well as public health communication best practices, this article describes lessons learned to assist CCC coalitions and programs with systematic implementation of communication efforts as key strategies in cancer control.

Results

Communication-oriented lessons include (1) effective communication work requires listening and ongoing engagement with key stakeholders, (2) communication interventions should target multiple levels from interpersonal to mediated channels, (3) educational outreach can be a valuable opportunity to bolster coalition effectiveness and cancer control outcomes, and (4) dedicated support is necessary to ensure consistent communication efforts.

Conclusions

External and internal communication strategies can optimize coalition efforts and resources to ultimately help produce meaningful improvement in cancer control outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Comprehensive cancer control (CCC) coalitions offer an essential, systematic approach to reducing cancer risk and burden [1]. The first two decades of the CCC movement have included diverse efforts offering lessons and best practices for the future of cancer control, driven by collaborations among government public health programs, academic institutions, community organizations, political bodies, and professional societies [2]. Noteworthy coalition work operates at a range of levels, from national policy efforts to community and tribal interventions, as well as across the spectrum of cancer-related topics.

Cancer prevention and control efforts have contributed to improvements in cancer-screening rates, better alignment between institutional and policy goals, as well as longer-term prevention efforts to mitigate risk factors such as obesity and sun exposure [2, 3]. In addition, targeted, evidence-based approaches have improved surveillance and early detection in healthy and high-risk population subgroups and disease types. Despite this, cancer-related morbidity and mortality rates remain high [4, 5]. Lessons from two decades of CCC experiences, including communication strategies, continue progress made toward reducing cancer burdens [6].

The importance of communication in cancer prevention and control has become increasingly clear. Communication plays a significant role in (1) creating strong community coalition partnerships, (2) capacity-building within coalitions, and (3) improving intervention outcomes across the cancer continuum from prevention through survivorship or palliative care (see the Comprehensive Cancer Control Implementation Building Blocks at cccnationalpartners.org). Courtesy of efforts launched by the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) across 20 years, there now exists a more accurate understanding of how to employ well-structured communication planning and strategy to improve coalition effectiveness and outcomes. Thus, the intent of this article is to offer examples of how coalitions have used a range of communication options to successfully promote cancer prevention and control.

CCC and communication

When the CCC movement began, it was built upon the idea that if national, state, and local partners collaborated effectively, more people could be screened, diagnosed, and connected to care earlier. Some cancers could be prevented if the places where people lived, worked, and played allowed them to lead healthier lives. Since the late nineties, these collaborations have focused energy and resources on:

-

reducing people’s risks for developing cancer;

-

ensuring screenings at the right times;

-

helping cancer survivors live longer, healthier lives; and

-

expanding opportunities for communities with the poorest cancer outcomes to improve their health [7,8,9].

External and internal communication strategies have served as the backbone of CCC coalitions, helping foster improved health outcomes across states, tribes, and tribal organizations as well as U.S. territory and Pacific Island Jurisdictions.

Coalitions formed and expanded using communication to successfully attract and encourage new partners to join. Once formed, CCC groups often developed internal communication strategies to create an identity, organize partnerships more efficiently, and govern how information would be shared among members as well as the public. Over the years, coalitions have shared key messages via a number of methods, including websites, program briefs, newsletters, traditional, and social media as well as word-of-mouth campaigns. Internal communication tactics helped effectively organize partnerships and resources to continue programs, campaigns, and control efforts [10].

Educational campaigns have also been an important way of communication efforts to externally support the CCC movement. Some recent examples include CCC coalitions and programs sharing messages and materials from campaigns such as:

-

Tips From Former Smokers public service announcements (PSAs) and materials used to reduce smoking and tobacco use [11].

-

Inside Knowledge campaign raising gynecologic cancer awareness among women, educating them about the warning signs, and encouraging them to seek medical care [12].

-

Bring Your Brave campaign sharing the voices and experiences of young breast cancer survivors to educate other young women about reducing breast cancer risks [13].

Less visible but also essential are those communications that fostered support and implementation of policy, systems, and environmental (PSE) improvements. Persuasive communication with various stakeholders supports organizational and community partnership development, allowing PSE change to advance through broad promotion that generates public buy-in (see Action4PSEChange.org for more details). In recent years, CCC programs have used public information campaigns to gain public support for PSE change by raising awareness about how cancer can be prevented through healthier lifestyle changes such as healthy eating and increased physical activity [14, 15].

Coalition partners have also used program briefs and infographics to educate decision-makers about the PSE interventions such as: smoke-free buildings, parks, and cities; increased opportunities for physical activity through bike lanes and building designs that promote walking; and system changes such as tailored messaging employed by community health workers to promote screening. Subsequently, CCC coalitions and their partners have used communications to ensure that public health improvements are implemented after policies and laws have been passed [15,16,17].

One recent example includes working with federal, state, and local officials to educate public housing agencies of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) smoke-free policy. In September 2017, the CDC, American Cancer Society, and HUD convened a workshop to increase states’ abilities to implement the new smoke-free public housing law. State teams comprising a Tobacco Control Program Manager, CCC Program Director, ACS Health Systems Manager, and HUD/Public Housing Authority Representative collaboratively developed action plans to support compliance with the new rule [18].

Coalition efforts have produced significant successes for individual- and population-level health outcomes in addition to systems-level changes within organizations and government [16, 19,20,21]. Reviewing what works within CCC communication efforts is necessary to promote best practices. Continued health disparities reveal opportunities for development and expansion of effective communication strategies. The intent of this article is to offer lessons learned, best practices, and strategic considerations that CCC programs can use to sustain coalitions and improve the effectiveness of cancer control efforts. Examples of targeted campaigns and internal communication strategies are offered to illustrate how coalitions have leveraged traditional public health practices and communication science.

Communication Best Practices

Over the years, National Comprehensive Cancer Control awardees have been required to develop communication plans to educate their staff, partners, constituents, and other stakeholders about their state’s cancer burden and the types of cancer control interventions and PSE strategies that could reduce that burden. Based on a review of published practices, four lessons stand out as essential to effective cancer control and prevention work: (1) listening to stakeholders during development and strategy implementation; (2) using multiple channels and varying levels to maximize communication effectiveness; (3) using non-traditional communication channels such as continuing education classes for capacity-building opportunities and lasting impact; and (4) having a dedicated owner of communication activities to ensure consistent communication efforts.

Listening to key stakeholders

Effective communication starts with listening. For coalitions, a number of program evaluations demonstrate the importance of engaging with stakeholders before starting work and continuing to do so once underway [22, 23]. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) programs offer a potentially useful framework because effective listening to community and coalition members, as well as collaboration at each step, helps bring human factors such as culture and health literacy into the planning and implementation processes.

Additionally, being connected to the community presents innovative opportunities for communication placements that may not otherwise be obvious, such as at farmers’ markets or other events. Active listening also presents opportunities to learn about community features that could inform coalition strategy and communication nuances, making listening essential at step one and every step along the way.

In this context, CBPR is primarily concerned with the fundamental task of involving community stakeholders in determining how to translate and disseminate evidence-based cancer prevention and control knowledge into key communities and how to optimize implementation strategies to improve public health [24]. It is an approach to research and cancer control designed to ensure and establish connections with community stakeholders continuously and in multiple ways, beginning with an understanding that CCC members and stakeholders are on equal ground. All parties share the joint goal of distributing knowledge multi-directionally with shared decision-making power and mutual ownership of programs.

Substantial engagement among stakeholders forces consideration of human factors like health literacy and culture, increasing accessibility and community-level leadership [25]. An example is the National Cancer Institute (NCI)-funded Tampa Bay Community Cancer Network (TBCCN) aiming to reduce cancer health disparities in the Tampa Bay area. Working with the Moffitt Cancer Center, this academic-community partnership includes local entities such as health centers, non-profit organizations, faith-based groups, and adult education and literacy groups, along with county-level government departments. Representatives from community organizations are involved in all network activities and at every level of programming, including research, training, and outreach work.

Community involvement at each level, including leadership, ensures that resources are being employed in ways that will be likely to resonate with and be useful to stakeholder communities to maximize effectiveness. For example, responding to a community-identified need for culturally and linguistically appropriate resources, the TBCCN supports Campamento Alegria, a three-day camp conducted in Spanish to offer support around Latina survivorship issues. Organized and delivered by community volunteers, the ground-breaking program operates under a planning committee that includes community members and Latina cancer survivors in addition to health professionals [25].

The TBCCN also includes collaboration on the Haitian Heritage Festival, an event run by local Haitian American leaders and an opportunity to again provide health resources in a culturally and linguistically relevant way. Community-level leadership made it clear that cancer-related issues were not a top-level concern in the Haitian community so the network built relationships with non-cancer-related medical providers to add screening and education resources about hypertension, diabetes, and HIV/AIDS, in addition to cancer control efforts. Changes were based on listening, which resulted in providing care driven by community-determined needs while increasing trust between medical providers and the community [25].

In situations like the two above, involving the target audience as collaborators with valuable insight and information to share allows for more effective coalitions for several reasons. It promotes commitment from community partners who feel heard, with reverberating effects through their social networks. Mistakes or misunderstandings may be avoided by listening to stakeholders, and campaigns may be more efficiently employed by aligning with cultural beliefs and respecting local practices. Community collaboration also presents innovative opportunities about when and how to reach stakeholders and to leverage existing community practices, beliefs, or infrastructure to support CCC efforts and program goals [26].

Multi-level communication planning

Communication planning requires reaching stakeholder groups through multiple channels at different levels of communication [27,28,29]. These levels range from interpersonal to mass media and all communications in-between. Communication science shows that disseminating the same message via different channels and at varied times increases the chance of it resonating with the intended audience [30]. By focusing on interpersonal, small group, organizational, and media channels, coalitions can create an integrated communication framework for consistent, cohesive messaging to partner organizations, potential collaborators, and the general public, among other audiences, with well-timed messages capable of improving awareness, attitudes, and behaviors.

A number of thoughtful, interpersonally focused communication campaigns exist in coalition efforts across the United States, and the Indiana County Cancer Coalition’s (ICCC) implementation of the American Cancer Society’s Tell a Friend® project in rural Pennsylvania is a noteworthy example. The ICCC collaborated with 18 food pantries and adapted the Tell a Friend program to improve mammography screening rates among women in medically underserved communities [29].

Tell a Friend uses interpersonal, one-to-one conversation driven by volunteers to encourage friends, family members, and neighbors to get a mammogram. The Tell a Friend program was further supported by reminders, printed materials, marketing give-aways, and radio advertisements to serve as localized mass media capable of being seen and heard by intended audiences. The foundational idea is to cause behavior change through a series of social-support-driven, one-to-one interactions reinforced by other media that can move individuals from not considering mammography screening to taking action. Moving persons through this decision process aligns with going from pre-contemplation to action in the Stages of Change model [31]. The multi-method, multi-level approach increased the likelihood that stakeholders would be exposed to the message repeatedly, in different contexts, and at different times, reinforcing the desired behavior change goal and overcoming key barriers to mammography adoption [29].

At the interpersonal level, interactions between volunteers and community members started as people entered the food pantries. This provided an opportunity for a Tell a Friend volunteer to determine which women were age-appropriate for mammograms and start one-to-one conversation about screening. In addition to engaging in conversations about annual check-ups, community members also received printed materials and marketing collateral to promote the need for regular mammograms. Once an appointment was made, medical offices followed up with phone-call reminders [29].

Building on the personally targeted outreach, a localized media campaign reinforced interpersonal messaging and support efforts. The coalition used radio advertisements to promote awareness of the risk of breast cancer, early detection benefits, and no-cost services available locally. The media promotions ran during peak hours at consistent intervals over a month, providing more opportunities for community members to engage with the topic of screening through multiple communication channels between the first interaction and the actual test [29].

During the ICC Coalition’s Tell a Friend five-month run in 2005, more than half of age-eligible women addressed by a volunteer in the line to enter the food pantries had not had a mammogram in the last year or did not have a next one scheduled. Of the group in need of a screening, almost 90% received a mammogram courtesy of the program, significantly increasing (28%) the number of no-cost screenings in Indiana County and leading to treatment regimens for three women diagnosed with breast cancer [29].

The multiple-contact method successfully bolstered cohesion in the community, including recruiting food pantry patrons and increasing awareness of cancer-screening recommendations. Notably, the one-to-one contact (peer counseling and education) with the food pantry patrons was cited by coalition members and food pantry volunteers as one of the most rewarding aspects of the initiative [29].

Connecting with individuals at multiple points through different communication channels helps ensure repeated exposure to the desired message [27]. The evidence-based ICCC intervention demonstrates the effectiveness of multiple-contact points, employing interpersonal peer conversation while women entered the pantry, reminder calls from doctors once appointments were scheduled, and marketing materials to keep the mammogram top of mind, all showing the possibilities for coalition- and community-driven screening interventions [29].

Education as a communication channel

Beyond the obvious promotional avenues and media outlets, other coalition-relevant communication opportunities can come from integrating community or professional education trainings into the coordinated communication mix [32]. Below are two examples of how cancer coalitions and programs use continuing education as communication channels for CCC efforts.

Utah’s Cancer Action Network implements several important educational programs and trainings in its efforts to impact cancer. Utah’s strategies focus on driving change through awareness and educational efforts that include both the public and private sectors [33]. The state coalition incorporates action steps that encourage working with both providers and employers on patient education strategies to encourage and facilitate screenings and behaviors while also educating company leaders on the benefits of paid time off for medical screenings, tobacco-free workplaces, healthier food in vending machines, and protective clothing to mitigate risks from chemicals and sun exposure [34, 35]. The integration of education and training for providers, employers, and patients as well as policy makers is essential to maintaining both consistency of communication as well as conveying a perception of unity in terms of the importance of preventing cancer as a community-wide effort [36].

In 2003, as a result of more than 1,500 men and women dying from colorectal cancer (CRC) per year, the Commissioner of the New York City (NYC) Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) made increased CRC screening a top priority for NYC residents. Although evidence supported that CRC screening could prevent death through earlier detection and treatment, more than 60% of age-eligible New Yorkers had not been screened. The commissioner established an advisory committee to assess the potential contribution of colonoscopies to NYC’s CRC prevention efforts, evolving into the Citywide Colon Cancer Control Coalition (C5) [37].

The coalition established several initiatives to increase colonoscopy-screening rates for all New Yorkers aged 50-plus and eliminate racial and ethnic screening disparities. Provider education and outreach included messages promoting colonoscopy screening every 10 years and were posted in the City Health Information newsletter delivered to more than 10,000 providers. The provider education program took on a more specific focus between 2004 and 2008 when trained DOHMH representatives completed onsite visits and nearly 4,000 one-on-one contacts to encourage adherence to CRC screening guidelines.

Trained representatives also promoted screening referrals at sites that demonstrated either poor screening uptake, high poverty, and/or high immigrant populations [37] in part by implementing a navigator program. The C5 coalition implemented a patient navigator program in 11 public and 12 voluntary hospitals throughout NYC, driven by an extensive online training program offering formal orientation and ongoing continuing education seminars. In addition, coalition leaders launched radio commercials and poster placements using public transit vehicles, bus shelters, and public hospitals [35].

These examples suggest that educational and training programs can be effective at engaging the public and allied health professionals in longer-term changes that go beyond promotional efforts for short-term outcomes such as increasing screening rates. Continuing education is an opportunity to improve awareness, knowledge, attitudes, and intentions, and to make long-lasting practice changes. Leveraging professional-development channels that connect health care providers with an educational infrastructure can sustain the long-term impact of CCC efforts and allow for continuous communication training focused on multiple levels from patient-provider contexts to media training.

Coordinated Coalition Communication

It has become clear over the past two decades that coalitions benefit from having an individual or small team dedicated to the management of communication efforts [38, 39]. Consolidating communication leadership and designating the area as a specific responsibility encourages accountability to timelines, consistent messaging, consideration of how different channels are being used, and supportive collaborations among partners [40]. A program manager with a communication focus is pivotal to providing central leadership, coordinating messages and developing formal communication processes, as well as managing partner participation to create a rhythm of touch-points [41] (also see ‘Nine Habits of Successful Comprehensive Cancer Control Coalitions’ on cccnationalpartners.org).

The efforts of the Appalachian Leadership Initiative on Cancer (ALIC) and the Alabama Comprehensive Cancer Control Coalition (ACCCC) [38, 41] suggest that an organized structure led by a communication point person with expertise creates consistency and fosters team-based work. The integration of external and internal communications facilitates successful coalition building, as well as culturally competent engagement of key outside audiences.

Support for applying communication best practices

CDC has invested substantially in the development of technical assistance and training (TAT) to support the application of evidence-based communication strategies for cancer control. Table 1 provides a curated list of available resources from CDC and other Comprehensive Cancer Control National Partnership members that are designed to help cancer control professionals implement the best practices described in this article. CDC subject matter experts have released resources to support the use of plain language and attention to health literacy in public health and clinical practice. These include an assessment tool for checking the level of accessibility of written materials, a glossary of terms to help replace complicated jargon with plain language, a guide with templates for development of effective media plans, a guide to improve communication and audience engagement via social media, a success story application to help organizations highlight their work, and several open-source media resources on prevention topics that can be repurposed by state and local organizations.

From 2013 to 2018, the CDC funded the development of TAT through two cooperative agreements (DP13-1315) with the American Cancer Society (ACS) and the George Washington University (GW) Cancer Center (formerly Institute). One of the focus areas of the TAT was to support communication strategies to promote CCC program successes and leverage additional resources for cancer control and prevention. The ACS led development of several resources on behalf of the CCC National Partnership including a guide on how coalitions can work with the media to advance PSE change efforts and a communication framework for disseminating and promoting CCC program and coalition successes. In collaboration with the National Association of Chronic Disease Directors, the ACS released a guide to help cancer control coalitions develop and communicate their identity and brand, communicate clearly with one voice, and market the group and its activities. In collaboration with the National Association of County and City Health Officials, the ACS released an archived webinar and print resource to help local health departments develop targeted messages to promote tobacco cessation among cancer survivors. The ACS has also led coordination of the National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable, which produced several resources to help with evidence-based cancer communication when promoting colorectal cancer screening, particularly among the newly insured, the “insured, procrastinator/rationalizer,” and the financially challenged, with companion messages tested specifically for Hispanic/Latino and Asian American populations. Their website includes radio and TV scripts, infographics, social media messages and banner ads, tips on engaging celebrities and getting earned media coverage, and a resource on evaluating communications efforts.

The GW Cancer Center, through the CDC cooperative agreement, also produced TAT to support evidence-based communication. The Cancer Survivorship E-Learning Series for Primary Care Providers Communication Toolkit helps stakeholders establish a communication strategy to promote the Cancer Survivorship E-Learning Series for Primary Care Providers (a no-cost continuing education program), implement Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn and blogging best practices, and disseminate E-Learning Series and cancer survivorship care messaging. The GW Cancer Center also released a two-part training that uses interactive web-based presentations to train CCC professionals on communication strategies. Communication Training 101 covers media planning and media relations and 102 provides in-depth training on designing and implementing evidence-based communication campaigns. Both courses have supplemental guides, including resources and templates.

The GW Cancer Center ran one cohort of a mentorship program that was designed to help mentees develop public health competencies and apply evidence through a mentored project experience, a series of seminars, and relationships with mentors and peers. The program’s four main goals were to (1) increase skills in core public health competency areas; (2) facilitate completion of high-quality projects related to CCC plan objectives; (3) encourage the use and spread of evidence-based practices; and (4) provide opportunities for networking and collaborative learning. The GW Cancer Center plans to run additional cohorts in future years with a focus on communication related to cancer prevention and early detection services. The GW Cancer Center also publishes multiple social media toolkits for various health awareness observances throughout the year. These toolkits can help public health professionals establish a social media strategy, manage social media accounts, implement best practices, and evaluate their social media efforts. Toolkits include evidence-informed sample messaging, tips, and other resources.

Conclusion

Evidence- and best practice-based communication strategies offer opportunities to bolster the effectiveness and efficiency of CCC coalitions and programs. Key lessons from the last two decades include (1) engaging key stakeholders for effective communication work; (2) targeting multiple levels of communication channels, from interpersonal to mediated, for consistent, comprehensive communication interventions; (3) leveraging educational and training programs to bolster coalition effectiveness and promotion of long-lasting change aligned with coalition goals; and (4) dedicated support to organize and sustain communication efforts is vital to ensure consistent messaging and coalition efficiency.

Building on these lessons, particularly in the digital age, communication capabilities present a key asset in CCC efforts because of the increased possibilities for tailoring messages to more precise stakeholder groups, increasing productivity, value, and reach of coalition-based efforts [42]. The opportunity to employ more specialized, community-centric channels, such as social media, offers significant opportunities not available to prior generations of prevention and control efforts [43, 44].

Amidst this new age of communication with ever-expanding channels to connect with specific and targeted audiences, we can learn from the diverse efforts of the CCC movement over the past 20 years to identify best practices and translatable lessons. This may inform future coalition efforts to optimally employ new communication platforms available to them for greater effectiveness in the future.

References

Given LS, Hohman K, Graaf L, Rochester P, Belle-Isle L (2010) From planning to implementation to outcomes: comprehensive cancer control implementation building blocks. Cancer Causes Control 21:1987–1994

Rochester PW, Townsend JS, Given L, Krebill H, Balderrama S, Vinson C (2010) Comprehensive cancer control: progress and accomplishments. Cancer Causes Control 21:1967–1977

Weinberg A, Jackson M, Decourtney P C, et al (2010) Progress in addressing disparities through comprehensive cancer control. Cancer Causes Control 21:2015–2021

Singal AG, Gupta S, Tiro JA et al (2016) Outreach invitations for FIT and colonoscopy improve colorectal cancer screening rates: a randomized controlled trial in a safety-net health system. Cancer 122:456–463

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A (2017) Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 67: 7–30

Hesse BW, Cole GE, Powe BD (2013) Partnering against cancer today: a blueprint for coordinating efforts through communication science. JNCI Monogr 2013:233–239

Ory MG, Sanner B, Vollmer Dahlke D, Melvin CL (2015) Promoting public health through state cancer control plans: a review of capacity and sustainability. Front Public Health 3:40

Siba Y, Culpepper-Morgan J, Schechter M et al (2017) A decade of improved access to screening is associated with fewer colorectal cancer deaths in African Americans: a single-center retrospective study. Ann Gastroenterol 30:518–525

Nahmias Z, Townsend JS, Neri A, Stewart SL (2016) Worksite cancer prevention activities in the National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program. J Community Health 41:838–844

Hohman K, Rochester P, Kean T, Belle-Isle L (2010) The CCC National Partnership: an example of organizations collaborating on comprehensive cancer control. Cancer Causes Control 21:1979–1985

Davis KC, Duke J, Shafer P, Patel D, Rodes R, Beistle D (2017) Perceived Effectiveness of antismoking ads and association with quit attempts among smokers: evidence from the tips from former smokers campaign. Health Commun 32:931–938

Townsend JS, Puckett M, Gelb CA, Whiteside M, Thorsness J, Stewart SL (2018) Improving knowledge and awareness of human papillomavirus-associated gynecologic cancers: results from the national comprehensive cancer control program/inside knowledge collaboration. J Womens Health 27:955–964

Buchanan LN, SK F, Betsy S, Jennifer R, Ben W, Temeika F (2018) Young women’s perceptions regarding communication with healthcare providers about breast cancer, risk, and prevention. J Womens Health 27:162–170

Townsend JS, Steele CB, Hayes N, Bhatt A, Moore AR (2017) Human papillomavirus vaccine as an anticancer vaccine: collaborative efforts to promote human papillomavirus vaccine in the National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program. J Womens Health 26:200–206

Leeman J, Myers AE, Ribisl KM, Ammerman AS (2015) Disseminating policy and environmental change interventions: insights from obesity prevention and tobacco control. Int J Behav Med 22:301–311

Rohan EA, Chovnick G, Rose J, Townsend JS, Young M, Moore AR (2018) Prioritizing population approaches in cancer prevention and control: results of a case study evaluation of policy, systems, and environmental change. Popul Health Manag. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2018.0081

Nitta M, Navasca D, Tareg A, Palafox NA (2017) Cancer risk reduction in the US Affiliated Pacific Islands: utilizing a novel policy, systems, and environmental (PSE) approach. Cancer Epidemiol 50:278–282

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Public and Indian Housing (2016) Instituting smoke-free public housing. Fed Regist 81(33):87430–87444

Saslow D, Sienko J, Nkonga JLZ, Brewer NT (2018) Creating a national coalition to increase human papillomavirus vaccination coverage. Acad Pediatr 18:S11–S13

Hiatt RA, Sibley A, Fejerman L et al (2018) The San Francisco Cancer Initiative: a community effort to reduce the population burden of cancer. Health Aff 37:54–61

Underwood JM, Lakhani N, Finifrock D et al (2015) Evidence-based cancer survivorship activities for comprehensive cancer control. Am J Prev Med 49:S536–S542

Davis SW, Cassel K, Moseley MA et al (2011) The cancer information service: using CBPR in building community capacity. J Cancer Educ 26:51–57

Morales-Alemán MM, Moore A, Scarinci IC (2018) Development of a participatory capacity-building program for congregational health leaders in African American churches in the US South. Ethn Dis 28(1):11–18

Harrop JP, Nelson DE, Kuratani DG, Mullen PD, Paskett ED (2012) Translating cancer prevention and control research into the community setting: workforce implications. J Cancer Educ 27:S157–S164

Meade CD, Menard JM, Luque JS, Martinez-Tyson D, Gwede CK (2011) Creating community–academic partnerships for cancer disparities research and health promotion. Health Promot Pract 12:456–462

McCracken JL, Friedman DB, Brandt HM et al (2013) Findings from the Community Health Intervention Program in South Carolina: implications for reducing cancer-related health disparities. J Cancer Educ 28:412–419

Atkin C (2001) Theory and principles of media health campaigns. In: Rice R, Atkin C (eds) Public communication campaigns. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Legler J, Meissner HI, Coyne C, Breen N, Chollette V, Rimer BK (2002) The effectiveness of interventions to promote mammography among women with historically lower rates of screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 11:59–71

Bencivenga M, DeRubis S, Leach P, Lotito L, Shoemaker C, Lengerich EJ (2008) Community partnerships, food pantries, and an evidence-based intervention to increase mammography among rural women. J Rural Health 24:91–95

Rice R, Atkin C (2002) Communication campaign: theory, design, implementation, and evaluation. In: Bryant J, Zillmann D (eds) Media effects: advances in theories and research. Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, pp 427–451

Prochaska J, Redding C, Evers K (2002) The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In: Glanz K, Rimer B, Lewis F (eds) Health behavior and health education: theory, research and practice. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, pp 99–120

St Pierre J, Bach J, Duquette D et al (2014) Strategies, actions, and outcomes of pilot state programs in public health genomics, 2003–2008. Prev Chronic Dis 11:E97

Broadwater C, Heins J, Hoelscher C, Mangone A, Rozanas C (2004) Skin and colon cancer media campaigns in Utah. Prev Chronic Dis 1:A18

Seeff LC, Major A, Townsend JS et al (2010) Comprehensive cancer control programs and coalitions: partnering to launch successful colorectal cancer screening initiatives. Cancer Causes Control 21:2023–2031

Fowler B, Ding Q, Pappas L et al (2018) Utah cancer survivors: a comprehensive comparison of health-related outcomes between survivors and individuals without a history of cancer. J Cancer Educ 33:214–221

Utah Cancer Action Network (2016) Utah Comprehensive Cancer Prevention and Control Plan 2016–2020

Itzkowitz SH, Winawer SJ, Krauskopf M et al (2016) New York Citywide Colon Cancer Control Coalition: a public health effort to increase colon cancer screening and address health disparities. Cancer 122:269–277

Garland B, Crane M, Marino C, Stone-Wiggins B, Ward A, Friedell G (2004) Effect of community coalition structure and preparation on the subsequent implementation of cancer control activities. Am J Health Promot 18:424–434

Zakocs RC, Edwards EM (2006) What explains community coalition effectiveness? A review of the literature. Am J Prev Med 30:351–361

Nowell B (2009) Profiling capacity for coordination and systems change: the relative contribution of stakeholder relationships in interorganizational collaboratives. Am J Community Psychol 44:196–212

Desmond RA, Chapman K, Graf G, Stanfield B, Waterbor JW (2014) Sustainability in a state comprehensive cancer control coalition: lessons learned. J Cancer Educ 29:188–193

Choi N, Curtis CR, Loharikar A et al (2018) Successful use of interventions in combination to improve human papillomavirus vaccination coverage rates among adolescents—Chicago, 2013 to 2015. Acad Pediatr 18:S93–S100

Burke-Garcia A, Scally G (2014) Trending now: future directions in digital media for the public health sector. J Public Health (Oxf) 36:527–534

Ems L, Gonzales AL (2016) Subculture-centered public health communication: a social media strategy. New Media Soc 18:1750–1767

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Robert Bailey II, MPH, for his work in writing and editing this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Love, B., Benedict, C., Van Kirk Villalobos, A. et al. Communication and comprehensive cancer control coalitions: lessons from two decades of campaigns, outreach, and training. Cancer Causes Control 29, 1239–1247 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-018-1122-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-018-1122-0