Abstract

Purpose

Previous studies documented significant increase in overall survival for metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) since the late 1990s coinciding with the introduction and dissemination of new treatments. We examined whether this survival increase differed across major racial/ethnic populations and age groups.

Methods

We identified patients diagnosed with primary metastatic colorectal cancer during 1992–2009 from 13 population-based cancer registries of the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, which cover about 14 % of the US population. The 5-year cause-specific survival rates were calculated using SEER*Stat software.

Results

From 1992–1997 to 2004–2009, 5-year cause-specific survival rates increased significantly from 9.8 % (95 % CI 9.2–10.4) to 15.7 % (95 % CI 14.7–16.6) in non-Hispanic whites and from 11.4 % (95 % CI 9.4–13.6) to 17.7 % (95 % CI 15.1–20.5) in non-Hispanic Asians, but not in non-Hispanic blacks [from 8.6 % (95 % CI 7.2–10.1) to 9.8 % (95 % CI 8.1–11.8)] or Hispanics [from 14.0 % (95 % CI 11.8–16.3) to 16.4 % (95 % CI 14.0–19.0)]. By age group, survival rates increased significantly for the 20–64-year age group and 65 years or older age group in non-Hispanic whites, although the improvement in the older non-Hispanic whites was substantially smaller. Rates also increased in non-Hispanic Asians for the 20–64-year age group although marginally nonsignificant. In contrast, survival rates did not show significant increases in both younger and older age groups in non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics.

Conclusion

Non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanics, and older patients diagnosed with metastatic CRC have not equally benefitted from the introduction and dissemination of new treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Previous reports indicated survival improvement for metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) [1–4]. For instance, Kopetz et al. [4] documented that overall survival rates for metastatic CRC significantly increased beginning in 1998, followed by another increase starting in 2004 based on retrospective medical review of 2,470 metastatic CRC patients treated at two large academic centers [MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX) and the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN)] from 1990 through 2006. The authors also showed similar improvements in overall survival rates for metastatic CRC in population-based cancer registries participating in the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program [4]. These improvements in survival beginning in 1998 and 2004, respectively, are thought to reflect rapid increases in resection of liver metastases and the introduction of new drugs, specifically bevacizumab and cetuximab [4–12]. In this paper, we examined survival improvement for metastatic CRC in the general U.S. population across major racial/ethnic groups and broad age groups (20–64 and ≥65 years) in view of a number of prior examples of significant disparities in dissemination of new treatments by race/ethnicity and age [13–17].

Materials and methods

We used cancer incidence data collected by the 13 population-based cancer registries of the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program, which covers about 14 % of the US population [18]. Our analyses included patients who were diagnosed with primary metastatic CRC (historic stage = distant) between 1992 and 2009, aged 20 years or older, and actively followed for vital status. We excluded patients who were reported through death certificate or autopsy report only, alive with no survival time, missing or unknown cause of death, and with missing diagnosis dates. We further restricted our analyses to the four major US racial/ethnic groups (non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, non-Hispanic Asians, and Hispanics); data for American Indians/Alaska Natives were sparse. Age at diagnosis was grouped into two categories (20–64 years, ≥65 years) for each of the four major racial/ethnic groups. To evaluate temporal changes in survival rates, diagnosis years were grouped into four periods (1992–1997, 1998–2000, 2001–2003, 2004–2009). Using SEER*Stat statistical software (version 8.0.4; National Cancer Institute), we then calculated 5-year cause-specific survival rates for the four major racial/ethnic groups by age and calendar periods. Cause-specific survival rate was calculated using the actuarial method, and the SEER cause-specific death classification variable was used as the endpoint [19, 20]. Cause-specific survival rate differences between groups were considered significant if their 95 % confidence intervals did not overlap.

Results

There were a total of 49,893 selected patients with metastatic CRC in the SEER-13 database during 1992–2009. Of these patients, 69.4 % were non-Hispanic whites, 12.8 % non-Hispanic blacks, 8.8 % non-Hispanic Asians, and 9.0 % Hispanics; 41.0 % of patients were 20–64 years old and 59.0 % were 65 years or older.

As Table 1 shows, from 1992–1997 to 2004–2009, 5-year cause-specific survival rate significantly increased from 9.8 % (95 % CI 9.2–10.4) to 15.7 % (95 % CI 14.7–16.6) in non-Hispanic whites and from 11.4 % (95 % CI 9.4–13.6) to 17.7 % (95 % CI 15.1–20.5) in non-Hispanic Asians, but not in non-Hispanic blacks [from 8.6 % (95 % CI 7.2–10.1) to 9.8 % (95 % CI 8.1–11.8)] or Hispanics [from 14.0 % (95 % CI 11.8–16.3) to 16.4 % (95 % CI 14.0–19.0)]. Notably, there was no significant difference in 5-year cause-specific survival between non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, and non-Hispanic Asians during 1992–1997, 1998–2000, and 2001–2003. However, during 2004–2009 period, non-Hispanic blacks had significantly lower 5-year cause-specific survival rate than did the other racial/ethnic groups.

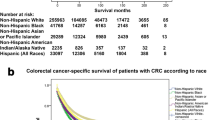

Table 2 shows 5-year cause-specific survival rates for racial/ethnic groups by age group. From 1992–1997 to 2004–2009, survival rates increased in age 20–64 years and ≥65 years for both non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic Asians, although the increase was statistically significant in non-Hispanic whites only. In contrast, survival rates remained unchanged for non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics, especially in the older age group. Although survival rates in non-Hispanic whites aged 65 years or older significantly increased from 1992–1997 to 2004–2009, the magnitude of increase was smaller and survival rates were significantly lower compared with their counterparts in the 20–64 years age group. The widening of the gap in cause-specific survival rates over the study period between non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks, especially in the younger age group, is further illustrated in the Fig. 1.

Discussion

We found that the improvement in survival rates for metastatic CRC from 1992 to 2009, presumably due to the introduction and dissemination of new treatments, was largely confined to the younger non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic Asians. There were no statistically significant increases in survival rates for non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics.

A number of studies have reported significant inequalities in dissemination of new treatments for CRC and other cancers between racial/ethnic groups [13, 21–24] despite accumulated evidence for equal treatment leading to equal outcome from randomized trials and from observational studies based on more equitable health care delivery systems [25–32]. For instance, Obeidat et al. [13] reported that African American patients were 37.9 % less likely to initially receive newer chemotherapy agents for metastatic CRC than white patients. Blacks also were less likely to receive surgical resection of colon cancer compared with whites (68 % blacks vs. 78 % whites) [33]. In addition, minorities have also been reported to be more likely to have a delayed initiation of treatment (especially adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy) and be less likely to be adherent to the treatment plan [13, 21]. Reasons for these treatment disparities may include difference in comorbidities, socioeconomic and psychosocial factors, quality of screening or diagnostic tests, affordability of new drugs, structural barriers such as lack of health insurance and limited transportation means to travel to treatment facilities, as well as within stage disease severity which may impact eligibility for certain treatments such as surgical resection of liver metastases [17, 23, 34–41].

Similarly, several studies documented that persons aged 65 years or older are less likely to receive aggressive treatment for CRC in part because of comorbidities, provider or patient preferences, and high Medicare co-payments for new drugs [14, 21, 27, 42, 43]. For example, McKibbin et al. [15] reported that 58 % of patients aged >65 years received chemotherapy for advanced CRC compared with 84 % of those aged ≤65 years. However, a recent study showed that first-line chemotherapy for metastatic CRC in older patients significantly improves survival rates with side effects comparable with those in younger patients [44].

The differences in survival improvement for metastatic CRC between racial/ethnic groups may also in part reflect changes in the distribution of disease severity over time because of differential uptake of screening [45, 46]. Compared with interval cancers, screen-detected cancers are more likely to be diagnosed at the earlier stage of the disease and have better prognosis [47], in view of significant heterogeneity in disease severity within stage [48]. CRC screening rates increased more for non-Hispanic whites than for other racial and ethnic groups. For example, according to the 2010 National Health Interview Survey, 62 % of non-Hispanic whites were current with their CRC screening tests compared with 55 % of non-Hispanic blacks and 47 % of Hispanics [49]. Furthermore, non-Hispanic whites are more likely to receive high-quality screening tests and follow-up after abnormal tests [45, 46, 50, 51].

Our study has certain limitations. The 13 SEER cancer registries considered in our analysis cover approximately 14 % of the US population. However, SEER 13 is a reasonably representative of the entire US population [52]. For example, 11.8 % of the population in SEER 13 was below poverty level compared with 13.1 % in the total US population [52]. Misclassification of race and ethnicity on medical records and inaccuracy of cause of death in death certificates are also possible limitations of our study, especially for racial/ethnic groups other than non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks [53, 54]. In addition, cause-specific survival in Hispanics and non-Hispanic Asians may be influenced by the return of foreign-born migrants back to their home country after cancer diagnosis [55]. The marginally nonsignificant survival increase in non-Hispanic Asians aged 20–64 years may indicate lack of statistical power.

In conclusion, the improvement in survival rates for metastatic CRC in the general population since 1998 largely reflects gains in younger non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic Asians. Survival has not significantly improved in non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanics, and the elderly, which suggests that these subpopulations have not equally benefited from new treatment advances for metastatic CRC. Our findings underscore the need for concerted efforts to increase access to new treatments for minority groups and the elderly, as well as additional research to better understand factors associated with race/ethnicity- and age-related survival disparities for metastatic colorectal cancer.

References

Delaunoit T, Alberts SR, Sargent DJ, Green E, Goldberg RM et al (2005) Chemotherapy permits resection of metastatic colorectal cancer: experience from Intergroup N9741. Ann Surg Oncol 16:425–429

Fuchs CS, Marshall J, Barrueco J (2008) Randomized, controlled trial of irinotecan plus infusional, bolus, or oral fluoropyrimidines in first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: updated results from the BICC-C study. J Clin Oncol 26:689–690

Tabernero J, Van Cutsem E, Díaz-Rubio E, Cervantes A, Humblet Y et al (2007) Phase II trial of cetuximab in combination with fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 25:5225–5232

Kopetz S, Chang GJ, Overman MJ, Eng C, Sargent DJ et al (2009) Improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer is associated with adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 27:3677–3683

Cummings LC, Payes JD, Cooper GS (2007) Survival after hepatic resection in metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer 109:718–726

Kuvshinoff B, Fong Y (2007) Surgical therapy of liver metastases. Semin Oncol 34:177–185

Nanji S, Cleary S, Ryan P, Guindi M, Selvarajah S et al (2013) Up-front hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer results in favorable long-term survival. Ann Surg Oncol 20:295–304

Choti MA, Sitzmann JV, Tiburi MF, Sumetchotimetha W, Rangsin R et al (2002) Trends in long-term survival following liver resection for hepatic colorectal metastases. Ann Surg 235:759–766

Emmanouilides C, Sfakiotaki G, Androulakis N, Kalbakis K, Christophylakis C et al (2007) Front-line bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin, leucovorin and 5-fluorouracil (FOLFOX) in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a multicenter phase II study. BMC Cancer 7:91

Grothey A, Sargent D, Goldberg RM, Schmoll H-J (2004) Survival of patients with advanced colorectal cancer improves with the availability of fluorouracil–leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin in the course of treatment. J Clin Oncol 22:1209–1214

Schrag D (2004) The price tag on progress—chemotherapy for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 351:317–319

Mahmoud N, Bullard Dunn K (2010) Metastasectomy for stage IV colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 53:1080–1092

Obeidat NA, Pradel FG, Zuckerman IH, Trovato JA, Palumbo FB et al (2010) Racial/ethnic and age disparities in chemotherapy selection for colorectal cancer. Am J Manag Care 16:515–522

Zafar SY, Malin JL, Grambow SC, Abbott DH, Kolimaga JT et al (2013) Chemotherapy use and patient treatment preferences in advanced colorectal cancer: a prospective cohort study. Cancer 119:854–862

McKibbin T, Frei CR, Greene RE, Kwan P, Simon J et al (2008) Disparities in the use of chemotherapy and monoclonal antibody therapy for elderly advanced colorectal cancer patients in the community oncology setting. Oncologist 13:876–885

Shavers VL, Brown ML (2002) Racial and ethnic disparities in the receipt of cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst 94:334–357

Ball JK, Elixhauser A (1996) Treatment differences between blacks and whites with colorectal cancer. Med Care 34:970–984

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) SEER*Stat databases: November 2012 submission. http://seer.cancer.gov/data/seerstat/nov2012/

The National Cancer Institute: Surveillance E, and End Results Program (2013) SEER cause-specific death classification. http://seer.cancer.gov/causespecific/index.html

Howlader N, Ries LA, Mariotto AB, Reichman ME, Ruhl J et al (2010) Improved estimates of cancer-specific survival rates from population-based data. J Natl Cancer Inst 102:1584–1598

Potosky AL, Harlan LC, Kaplan RS, Johnson KA, Lynch CF (2002) Age, sex, and racial differences in the use of standard adjuvant therapy for colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 20:1192–1202

Gross CP, Smith BD, Wolf E, Andersen M (2008) Racial disparities in cancer therapy. Cancer 112:900–908

Baldwin LM, Dobie SA, Billingsley K, Cai Y, Wright GE et al (2005) Explaining black–white differences in receipt of recommended colon cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst 97:1211–1220

Jessup J, Stewart A, Greene FL, Minsky BD (2005) Adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer: implications of race/ethnicity, age, and differentiation. JAMA 294:2703–2711

Sanoff HK, Sargent DJ, Green EM, McLeod HL, Goldberg RM (2009) Racial differences in advanced colorectal cancer outcomes and pharmacogenetics: a subgroup analysis of a large randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 27:4109–4115

Berry J, Caplan L, Davis S, Minor P, Counts-Spriggs M et al (2010) A black-white comparison of the quality of stage-specific colon cancer treatment. Cancer 116:713–722

Dominitz JA, Samsa GP, Landsman P, Provenzale D (1998) Race, treatment, and survival among colorectal carcinoma patients in an equal-access medical system. Cancer 82:2312–2320

Page WF, Kuntz AJ (1980) Racial and socioeconomic factors in cancer survival. A comparison of veterans administration results with selected studies. Cancer 45:1029–1040

Polite BN, Sing A, Sargent DJ, Grothey A, Berlin J et al (2012) Exploring racial differences in outcome and treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer 118:1083–1090

Akerley WL III, Moritz TE, Ryan LS, Henderson WG, Zacharski LR (1993) Racial comparison of outcomes of male Department of Veterans Affairs patients with lung and colon cancer. Arch Intern Med 153:1681

Rogers S, Ray W, Smalley W (2004) A population-based study of survival among elderly persons diagnosed with colorectal cancer: does race matter if all are insured? (United States). Cancer Causes Control 15:193–199

Albain KS, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, Coltman CA, Hershman DL (2009) Racial disparities in cancer survival among randomized clinical trials patients of the Southwest Oncology Group. J Natl Cancer Inst 101:984–992

Cooper GS, Yuan Z, Landefeld CS, Rimm AA (1996) Surgery for colorectal cancer: race-related differences in rates and survival among medicare beneficiaries. Am J Pub Health 86:582–586

Demissie K, Oluwole OO, Balasubramanian BA, Osinubi OO, August D et al (2004) Racial differences in the treatment of colorectal cancer: a comparison of surgical and radiation therapy between whites and blacks. Ann Epidemiol 14:215–221

Tropman SE, Hatzell T, Paskett E, Ricketts T, Cooper MR et al (1999) Colon cancer treatment in rural North and South Carolina. Cancer Detect Prev 23:428–434

Guidry JJ, Aday LA, Zhang D, Winn RJ (1997) Transportation as a barrier to cancer treatment. Cancer Pract 5:361–366

Wagner TH, Heisler M, Piette JD (2008) Prescription drug co-payments and cost-related medication underuse. Health Econ Policy Law 3:51–67

Ekberg H, Tranberg KG, Andersson R, Lundstedt C, Hagerstrand I et al (1986) Determinants of survival in liver resection for colorectal secondaries. Br J Surg 73:727–731

Dayal H, Polissar L, Yang C, Dahlberg S (1987) Race, socioeconomic status, and other prognostic factors for survival from colo-rectal cancer. J Chronic Dis 40:857–864

Ciccolallo L, Capocaccia R, Coleman MP, Berrino F, Coebergh JW et al (2005) Survival differences between European and US patients with colorectal cancer: role of stage at diagnosis and surgery. Gut 54:268–273

Feinstein AR, Sosin DM, Wells CK (1985) The Will Rogers phenomenon: stage migration and new diagnostic techniques as a source of misleading statistics for survival in cancer. N Engl J Med 312:1604–1608

Abraham A, Habermann EB, Rothenberger DA, Kwaan M, Weinberg AD et al (2012) Adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer in the oldest old. Cancer 112:395–403

Hodgson DC, Fuchs CS, Ayanian JZ (2001) Impact of patient and provider characteristics on the treatment and outcomes of colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 93:501–515

Folprecht G, Seymour MT, Saltz L, Douillard JY, Hecker H et al (2008) Irinotecan/fluorouracil combination in first-line therapy of older and younger patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: combined analysis of 2,691 patients in randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol 26:1443–1451

Cooper GS, Koroukian SM (2004) Racial disparities in the use of and indications for colorectal procedures in Medicare beneficiaries. Cancer 100:418–424

Felix-Aaron K, Moy E, Kang M, Patel M, Chesley FD et al (2005) Variation in quality of men’s health care by race/ethnicity and social class. Med Care 43:I72–181

Courtney ED, Chong D, Tighe R, Easterbrook JR, Stebbings WS et al (2013) Screen-detected colorectal cancers show improved cancer-specific survival when compared with cancers diagnosed via the 2-week suspected colorectal cancer referral guidelines. Colorectal Dis 15:177–182

Hyslop T, Weinberg DS, Schulz S, Barkun A, Waldman SA (2012) Occult tumor burden contributes to racial disparities in stage-specific colorectal cancer outcomes. Cancer 118:2532–2540

Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brawley OW (2012) Cancer screening in the United States, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 62:129–142

Bach PB, Pham HH, Schrag D, Tate RC, Hargraves JL (2004) Primary care physicians who treat blacks and whites. N Engl J Med 351:575–584

Rolnick S, Alford SH, Kucera GP, Fortman K, Yood MU et al (2005) Racial and age differences in colon examination surveillance Following a diagnosis of colorectal cancer. JNCI Monogr 2005:96–101

Hankey BF, Ries LA, Edwards BK (1999) The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program: a National Resource. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 8:1117–1121

Gomez SL, Glaser SL (2006) Misclassification of race/ethnicity in a population-based cancer registry (United States). Cancer Causes Control 17:771–781

Sarfati D, Blakely T, Pearce N (2010) Measuring cancer survival in populations: relative survival vs cancer-specific survival. Int J Epidemiol 39:598–610

Johnson C, Weir H, Yin D, Niu X (2010) The impact of patient follow-up on population-based survival rates. J Registry Manag 37:86

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sineshaw, H.M., Robbins, A.S. & Jemal, A. Disparities in survival improvement for metastatic colorectal cancer by race/ethnicity and age in the United States. Cancer Causes Control 25, 419–423 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-014-0344-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-014-0344-z