Abstract

Objective

Current standards of care for early-stage breast cancer include either breast-conserving surgery (BCS) with post-operative radiation or mastectomy. A variety of factors influence the type of treatment chosen. In northern, rural areas, daily travel for radiation can be difficult in winter. We investigated whether proximity to a radiation treatment facility (RTF) and season of diagnosis affected treatment choice for New Hampshire women with early-stage breast cancer.

Methods

Using a population-based cancer registry, we identified all women residents of New Hampshire diagnosed with stage I or II breast cancer during 1998–2000. We assessed factors influencing treatment choices using multivariate logistic regression.

Results

New Hampshire women with early-stage breast cancer were less likely to choose BCS if they live further from a RTF (P < 0.001). Of those electing BCS, radiation was less likely to be used by women living >20 miles from a RTF (P = 0.002) and those whose diagnosis was made during winter (P = 0.031).

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that a substantial fraction of women with early-stage breast cancer in New Hampshire receive suboptimal treatment by forgoing radiation because of the difficulty traveling for radiation in winter. Future treatment planning strategies should consider these barriers to care in cold rural regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Most women with early-stage breast cancer have a choice between two roughly equivalent treatment options: either breast conserving surgery (BCS) followed by radiation therapy (RT), or a modified radical mastectomy (MRM) [1, 2]. Both approaches have been shown in randomized clinical trials to result in similar long-term survival [3–6]. BCS without subsequent radiation carries an increased risk of local recurrence, and current guidelines recommend against this approach [2].

Previous studies have shown that the use of BCS and post-operative radiation is influenced by age [7–10], psycho-social factors [11–13], and hospital characteristics [14–17]. Ease of access to treatment may also affect treatment choice for rural patients with cancer [12, 18–21]. Geographic factors, particularly proximity of treatment facilities to patients’ residence may play a role in treatment choice for rural patients with cancer. In a study of lung cancer patients in New Hampshire and Vermont, Greenberg et al. [18, 19] found that patients living further from a radiation therapy unit were less likely to receive radiation for their disease.

We assessed whether distance from a radiation treatment facility (RTF) and season of diagnosis affected choice of treatment among women with early stage breast cancer in New Hampshire, a state with a largely rural population [22] and which is noted for severe winter weather [23].

Materials and methods

Data collection

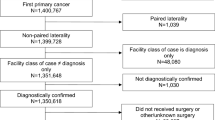

We identified women for study from the population-based New Hampshire State Cancer Registry (NHSCR). This statewide cancer surveillance program collects information on cases of in situ and invasive cancers seen and/or treated in the 27 hospitals and by other health care providers in New Hampshire and also receives data for state residents with cancer who are cared for in the three adjacent New England states, as well as Florida, New York, and other states with cancer registries. The quality of case reports and the case completeness of data meet standards set by the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACCR) [24]. Our study population consisted of all women residents of New Hampshire who were diagnosed between 1 January 1998 and 31 December 2001 with breast cancer histology and morphology codes 8500–8543 defined by ICD-O-2 for cases diagnosed in 1998–2000 and ICD-O-3 for cases diagnosed in year 2001. We excluded women diagnosed at autopsy or identified only through death certificates. The American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) staging group was used to classify cases by stage. Each case had either a pathologic or clinical AJCC stage group, and these were pooled into a combined stage group. Cases were defined as early-stage if the AJCC stage group was I–IIB (Fig. 1).

The treatment types studied were first course of surgery and radiation. Surgical treatment was categorized as BCS and non-BCS, regardless of whether axillary lymph node dissection was performed. BCS included partial mastectomy, nipple resection, lumpectomy, re-excision, wedge resection, tylectomy, quadrantectomy, and segmental and subcutaneous mastectomies. Non-BCS consisted of total/simple, radical and extended mastectomies. Only the most definitive surgical treatment within each type was considered. For example, if a patient had both BCS and non-BCS, the non-BCS was considered to be the most definitive. We collected information about possible predictors of treatment choices, including patient residence, date of diagnosis, marital status, age, presence of multiple primary cancers, and tumor stage and size. We classified the season of diagnosis as winter (December–February) or non-winter (March–November). Marital status was defined as married or unmarried (single, separated, divorced, or widowed). We defined women as having their first primary cancer (sequence 00 or 01) or multiple primaries (sequence 02–04) based on data in the registry.

Proximity of residence to radiation therapy facilities

We identified all facilities providing radiation treatment in New Hampshire (5), Maine (5), Massachusetts (30) and Vermont (3) during the years 1998–2001 [25–28]. Each facility and the addresses of the patients were geocoded by Geographic Data Technology (GDT) of Lebanon, NH to an exact street address (n=2292; 80.1%), or to the zip code centroid if only a post office box or rural route address (n=569; 19.9%) was provided. The shortest straight-line distance to a RTF was estimated for each case [29]. Of the 38 candidate RTFs, 9 were the nearest to at least one patient in the study (5 in NH, 3 in MA, and 1 in ME).

Statistical analysis

We performed simple descriptive analyses for all variables as well as tabulations of their treatment choices. We used univariate analyses (chi-square) to test the variables for statistical significance in relation to BCS and post-BCS RT. We then calculated odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals with multiple logistic regression to identify factors that determine treatment choices for women with early-stage breast cancer. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows version 11 [30] and SAS statistical software [31].

Approval for the study of human subjects

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Dartmouth College and the University of New Hampshire. Authorization was also granted by the State of New Hampshire, Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Community and Public Health, Bureau of Health Statistics and Data Management.

Results

The mean age of patients was 61 years (range 24–101). The mean distance between patient residence and the nearest RTF was 15.1 miles (range 0.1–89.9; median 13.9). Almost one quarter of patients lived ≥20 miles from the nearest RTF. Of the 1,883 (65.8%) women who were treated with BCS, 79% received post-operative RT. Of the 978 (34.2%) women who had non-BCS, 17.8% also had RT. Overall, 1,662 women (58.1%) had RT as part of their initial therapy.

In univariate analyses the shortest distance to a RTF (P ≤ 0.001), smaller tumor size (P ≤ 0.001), lower stage (P ≤ 0.001), first primary cancer (P ≤ 0.001), and age 75 or older (P = 0.001) were all predictors of women undergoing BCS. Diagnosis in the winter (P = 0.740) and marital status (P = 0.188) were unrelated to the choice of BCS. Even so, we included these two variables in our multivariate regression analysis given their relevance to this study.

In the multivariate model, we confirmed that women were less likely to have BCS with increasing distance from residence to RTF (P < 0.001), higher stage disease (P ≤ 0.001), increasing age (P = 0.003) or previous primary cancer (OR = 0.56, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.45–0.71). Diagnosis in the winter (P = 0.907) and marital status (P = 0.551) remained unrelated to the choice of BCS (Table 1). Interactions between distance and the patient’s age, and distance and winter diagnosis were not significant predictors in the model.

Following BCS, 395 women did not have RT; among this group, 22% (n = 87) had adjuvant chemotherapy, and 23% (n = 90) had adjuvant hormonal therapy. Univariate analysis showed that post-BCS RT was less likely in women diagnosed in the winter (P = 0.019) and those living further from the RTF (P < 0.001). Married women and women with no history of were also less likely to have RT (P < 0.001). Among women choosing BCS, stage did not affect whether they defaulted from RT (P = 0.962).

Using the same variables, we developed a multivariate logistic regression model for women who had BCS (Table 2). Patients were less likely to have radiation after BCS with increasing distance from residence to RTF (P = 0.002); diagnosis in winter months (OR = 0.75, 95% CI 0.57–0.97); age ≥75 (OR = 0.41, 95% CI 0.27–0.63); unmarried status (OR = 0.65, 95% CI 0.50–0.83); previous primary cancer (OR = 0.60, 95% CI 0.43–0.84), or tumor size 2–5 cm (OR = 0.76, 95% CI 0.50–1.17). There was no statistically significant interaction between distance and age or distance and winter diagnosis.

Discussion

Our study confirms previous findings that the choice of BCS may be influenced by the distance a patient lives from the nearest RTF [12, 20, 21]. We also found that, among women treated with BCS, those diagnosed during the winter months and those living more than 20 miles from a RTF were less likely to receive post-operative radiation. The use of BCS without radiation may put women at increased risk of recurrence [6] and lower survival [32]. However, the choice of treatment may not be completely clear-cut, especially for women over 70 who also receive adjuvant treatment [33–35].

One previous report, based on older women in 10 northern states, assessed the effects of season on therapy choice in breast cancer and noted no association overall between season and treatment received [36]. However, in three of these states (New Hampshire, Vermont, and South Dakota), the proportions of women having BCS were substantially lower in winter than summer. The effect of season on choice of RT in these three states was not specified. Another study by Greenberg et al. reported that New Hampshire and Vermont lung cancer patients diagnosed in January and February were more likely to be referred to a university cancer center for treatment, and that referral was more likely in winter only if the patient lived within 25 miles of a cancer center [19]. Possible reasons for the decreased use of BCS and/or RT among early-stage breast cancer patients living further from a RTF include women’s perceived access to care [20], regional practice patterns [21], access to transportation [36], and socioeconomic status [37].

A strength of our study was its use of a large population-based sample from the New Hampshire State Cancer Registry. However, we did not consider other types of treatment (i.e. axillary lymph node dissections, chemotherapy, and hormones), which in conjunction with certain clinical indicators, are all incorporated into the treatment guidelines. Additional limitations of the study relate to the procedures used by NHSCR to collect data. Most cases are reported to the registry within 6 months of diagnosis. Because the stage of cancers is generally determined at the time of the most definitive surgery, we would have misclassified stage if additional staging information was obtained after surgery. It has been reported that RT information may be incomplete in central registries [7, 38]. We would have misclassified the use of radiation if there was a significant delay before the course of radiation was given, for example, if patients in remote locations diagnosed during winter preferred to defer their treatment until spring.

Our estimate of straight-line distance to the nearest RTF only approximates the true travel distance, and estimates based on post office boxes addresses also entail some misclassification. A more precise representation of distance-related barriers to health care might be the travel time, which may reflect road quality. Future studies to confirm our findings might be to investigate travel time, which would also be a useful measure of access to healthcare. It is also possible that distance to treatment represents other factors that might vary by region and affect treatment choices, such as employment or income. Our database did not include the individual level variables that might have clarified this issue. Finally, it has been shown that women in rural areas tend to be diagnosed with breast cancer at a later stage. These women would be under-represented in a study of early-stage breast cancer such as ours [39].

In conclusion, early-stage breast cancer treatment is influenced by several factors; in New Hampshire, barriers to care include distance to nearest RTF and season of diagnosis. Women living more than 20 miles from a radiation treatment facility are not only less likely to have breast conserving surgery, but, if they do so, they are significantly less likely to receive post-operative radiation that would reduce their risk of recurrence. Of those electing BCS, a substantial fraction appear to forgo radiation because of the difficulty traveling during winter.

References

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2003) Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Breast Cancer. Version 3

National Institutes of Health (1990) National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement. Treatment of early-stage breast cancer. June 18–21

AS Lichter ME Lippman DN Danforth SuffixJr et al. (1992) ArticleTitleMastectomy versus breast-conserving therapy in the treatment of stage I and II carcinoma of the breast: a randomized trial at the National Cancer Institute J Clin Oncol 10 IssueID6 976–983 Occurrence Handle1588378 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK383mvV2mtg%3D%3D

JA Jacobson DN Danforth KH Cowan et al. (1995) ArticleTitleTen-year results of a comparison of conservation with mastectomy in the treatment of stage I and II breast cancer N Engl J Med 332 IssueID14 907–911 Occurrence Handle7877647 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK2M7otlSqsw%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1056/NEJM199504063321402

MM Poggi DN Danforth LC Sciuto et al. (2003) ArticleTitleEighteen-year results in the treatment of early breast carcinoma with mastectomy versus breast conservation therapy: the National Cancer Institute Randomized Trial Cancer 98 IssueID4 697–702 Occurrence Handle12910512 Occurrence Handle10.1002/cncr.11580

B Fisher S Anderson J Bryant et al. (2002) ArticleTitleTwenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer N Engl J Med 347 IssueID16 1233–1241 Occurrence Handle12393820 Occurrence Handle10.1056/NEJMoa022152

R Ballard-Barbash AL Potosky LC Harlan SG Nayfield LG Kessler (1996) ArticleTitleFactors associated with surgical and radiation therapy for early stage breast cancer in older women J Natl Cancer Inst 88 IssueID11 716–726 Occurrence Handle8637025 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK283hslKisA%3D%3D

SA Joslyn (1999) ArticleTitleRadiation therapy and patient age in the survival from early-stage breast cancer Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 44 IssueID4 821–826 Occurrence Handle10386638 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1Mzhtlajuw%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1016/S0360-3016(99)00071-1

A Hurria D Leung K Trainor P Borgen L Norton C Hudis (2003) ArticleTitleFactors influencing treatment patterns of breast cancer patients age 75 and older Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 46 IssueID2 121–126 Occurrence Handle12711357

GF Riley AL Potosky CN Klabunde JL Warren R Ballard-Barbash (1999) ArticleTitleStage at diagnosis and treatment patterns among older women with breast cancer: an HMO and fee-for-service comparison JAMA 281 IssueID8 720–726 Occurrence Handle10052442 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1M7lvFyjtQ%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1001/jama.281.8.720

RJ Nold RL Beamer SD Helmer MF McBoyle (2000) ArticleTitleFactors influencing a woman’s choice to undergo breast-conserving surgery versus modified radical mastectomy Am J Surg 180 IssueID6 413–418 Occurrence Handle11182389 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3M7lvVWrug%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1016/S0002-9610(00)00501-8

D Stafford R Szczys R Becker J Anderson S Bushfield (1998) ArticleTitleHow breast cancer treatment decisions are made by women in North Dakota Am J Surg 176 IssueID6 515–519 Occurrence Handle9926781 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1M7itl2ksw%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1016/S0002-9610(98)00257-8

S Benedict DJ Cole L Baron P Baron (2001) ArticleTitleFactors influencing choice between mastectomy and lumpectomy for women in the Carolinas J Surg Oncol 76 6–12 Occurrence Handle11223818 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3M7kvF2rtQ%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1002/1096-9098(200101)76:1<6::AID-JSO1002>3.0.CO;2-F

N Hebert-Croteau J Brisson J Latreille C Blanchette L Deschenes (1999) ArticleTitleVariations in the treatment of early-stage breast cancer in Quebec between 1988 and 1994 CMAJ 161 IssueID8 951–955 Occurrence Handle10551190 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3c%2FhvVyrtQ%3D%3D

ER Satariano GM Swanson PP Moll (1992) ArticleTitleNonclinical factors associated with surgery received for treatment of early-stage breast cancer Am J Public Health 82 IssueID2 195–198 Occurrence Handle1739146 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK387lt1egug%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.2105/AJPH.82.2.195

AB Nattinger MS Gottlieb J Veum D Yahnke JS Goodwin (1992) ArticleTitleGeographic variation in the use of breast-conserving treatment for breast cancer N Engl J Med 326 1102–1107 Occurrence Handle1552911 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK383gsVWqsA%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1056/NEJM199204233261702

ME Johantgen RM Coffey DR Harris H Levy JJ Clinton (1995) ArticleTitleTreating early-stage breast cancer: hospital characteristics associated with breast-conserving surgery Am J Public Health 85 IssueID10 1432–1434 Occurrence Handle7573632 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK28%2FisFSitQ%3D%3D

ER Greenberg CG Chute T Stukel et al. (1988) ArticleTitleSocial and economic factors in the choice of lung cancer treatment N Engl J Med 318 IssueID10 612–617 Occurrence Handle2830514 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaL1c7ktlSjtQ%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1056/NEJM198803103181006

ER Greenberg B Bain D Freeman J Yates R Korson (1988) ArticleTitleReferral of lung cancer patients to university hospital cancer centers Cancer 62 1647–1652 Occurrence Handle3167780 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaL1M%2Fgt1Kgsg%3D%3D

AB Nattinger RT Kneusel RG Hoffmann MA Gilligan (2001) ArticleTitleRelationship of distance from a radiotherapy facility and initial breast cancer treatment J Natl Cancer Inst 93 IssueID17 1344–1346 Occurrence Handle11535710 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3Mvptlartg%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1093/jnci/93.17.1344

WF Athas M Adams-Cameron WC Hunt A Amir-Fazli CR Key (2000) ArticleTitleTravel distance to radiation therapy and receipt of radiotherapy following breast-conserving surgery J Natl Cancer Inst 92 IssueID3 269–271 Occurrence Handle10655446 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3c7it1GhsQ%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1093/jnci/92.3.269

New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, Division of Public health Services (2004) NH Rural Health Report

State of New Hampshire. The New Hampshire Almanac. Fast New Hampshire Facts. [Accessed: 03/01/2004.] Available from: http://www.state.nh.us/nhinfo/index.html

North American Association of Central Cancer Registries. Home page. [Accessed 03/01/2004.] Available from: http://www.naaccr.org/

Medeiros G (11 Feb 2004) State of New Hampshire. Health Services Planning and Review Board. “RadTh facilities in NH.” E-mail to the author

Dawson T (16 May 2005) State of Vermont. Department of Health. Vermont Cancer Registry. “RE: Radiation Tx Facilities in VT”. E-mail to author

Verrill C (10 May 2005) State of Maine. Department of Human Services. Bureau of Health, Division of Community and Family Health. Maine Cancer Registry. “Radiation Facilities.” E-mail to author

King MJ (12 May 2005) State of Massachusetts. Department of Public Health. Center for Health Information, Statistics, Research and Evaluation. Massachusetts Cancer Registry. “Radiation treatment facilities.” Email to author

North American Association of Central Registries. Geographic Information Systems Committee. Distance Calculator SAS code. [Accessed: 05/18/2005.] Available from: http://www.naaccr.org/index.asp?Col_SectionKey=9&Col_ContentID=281

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 11.0 for Windows. (2004) SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL

Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) System for Windows, version 8.0. (2001) SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC

E Rapiti G Fioretta G Vlastos et al. (2003) ArticleTitleBreast-conserving surgery has equivalent effect as mastectomy on stage I breast cancer prognosis only when followed by radiotherapy Radiother Oncol 69 IssueID3 277–284 Occurrence Handle14644487 Occurrence Handle10.1016/j.radonc.2003.09.003

IE Smith GM Ross (2004) ArticleTitleBreast radiotherapy after lumpectomy – no longer always necessary N Engl J Med 351 IssueID10 1021–1023 Occurrence Handle15342811 Occurrence Handle1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2cXntlSqsL4%3D Occurrence Handle10.1056/NEJMe048173

KS Hughes LA Schnaper D Berry et al. (2004) ArticleTitleLumpectomy plus tamoxifen with or without irradiation in women 70 years of age or older with early breast cancer N Engl J Med 351 IssueID10 971–977 Occurrence Handle15342805 Occurrence Handle1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2cXnt12msrg%3D Occurrence Handle10.1056/NEJMoa040587

AW Fyles DR McCready LA Manchul et al. (2004) ArticleTitleTamoxifen with or without breast irradiation in women 50 years of age or older with early breast cancer N Engl J Med 351 IssueID10 963–970 Occurrence Handle15342804 Occurrence Handle1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2cXnt12nu7Y%3D Occurrence Handle10.1056/NEJMoa040595

JS Goodwin AB Nattinger (1995) ArticleTitleEffect of season and climate on choice of therapy for breast cancer in older women J Am Geriatr Soc 43 IssueID9 962–966 Occurrence Handle7657935 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK2Mzos1yhuw%3D%3D

LS McGinnis HR Menck JH Eyre et al. (2000) ArticleTitleNational Cancer Data Base survey of breast cancer management for patients from low income zip codes Cancer 88 IssueID4 933–945 Occurrence Handle10679664 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3c7ksFOhsg%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000215)88:4<933::AID-CNCR25>3.0.CO;2-I

NA Bickel NR Chassin (2000) ArticleTitleDetermining the quality of breast cancer care: do tumor registries measure up? Ann Intern Med 132 IssueID9 705–710

NC Campbell AM Elliott L Sharp LD Ritchie J Cassidy J Little (2002) ArticleTitleImpact of deprivation and rural residence on treatment of colorectal and lung cancer Br J Cancer 87 585–590 Occurrence Handle12237766 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD38vnsFWkug%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1038/sj.bjc.6600515

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Dale Collins (Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center), Dr. John Seavey and Dr. Greta Bauer (University of New Hampshire) for their helpful review and discussion of the manuscript, and Andrew Chalsma (New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services) for his continuous support of this project. This work was supported by the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Community and Family Health (Contract No. 710374) and the Norris Cotton Cancer Center Core Grant (P30 CA23108).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Celaya, M.O., Rees, J.R., Gibson, J.J. et al. Travel Distance and Season of Diagnosis Affect Treatment Choices for Women with Early-stage Breast Cancer in A Predominantly Rural Population (United States) . Cancer Causes Control 17, 851–856 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-006-0025-7

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-006-0025-7