Abstract

This paper employs theory of normal organizational wrongdoing and investigates the joint effects of management tone and the slippery slope on financial reporting misbehavior. In Study 1, we investigate assumptions about the effects of sliding down the slippery slope and tone at the top on financial executives’ decisions to misreport earnings. Results of Study 1 indicate that executives are willing to engage in misreporting behavior when there is a positive tone set by the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) (kind attitude toward employees and non-aggressive attitude about earnings), regardless of the presence or absence of a slippery slope. A negative tone set by the CFO does not facilitate the transition from minor indiscretions to financial misreporting. In Study 2, we find that auditors evaluating executives’ decisions under the same conditions as those in Study 1 do not react to the slippery slope condition, but auditors assess higher risks of fraud when the CFO sets a negative tone. Overall, our results indicate that many assumptions about the slippery slope and tone at the top should be questioned. We provide evidence that pro-organizational behaviors and incrementalism yield new insights into the causes of ethical failures, financial misreporting behavior, and failures of corporate governance mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Financial executives and external auditors play key roles in corporate governance (Gramling et al. 2004). Financial executives assist top management to safeguard the integrity of financial reporting (Maas and Matejka 2009; Suh et al. 2018), while auditors actively monitor organizational risks and provide assurance regarding the quality of financial reporting (Gramling et al. 2004). As internal corporate watchdogs, financial executives are expected to maintain their independence from “top management’s overly aggressive accounting and reporting practices” (Howell 2002, p. 20) while still working closely with top management (Ezkenazi et al. 2016). External auditors are required to exercise their professional skepticism throughout audit engagements, as they serve as external corporate watchdogs (Anderson et al. 2004; Rose et al. 2020; Trompeter and Wright 2010).

While reporting directly to the Chief Financial Officer (CFO), financial executives supervise the accounting department at a corporate or business unit level, participate in reporting-related activities (preparation of financial statements, operating budgets, and tax reports), and validate the completeness and integrity of financial information (e.g., Bell 2007; Davis and McLaughlin 2009; Ezkenazi et al. 2016; Ernst and Young 2008; Hopper 1980; Suh et al. 2020). Examples of financial executives are Chief Accounting Officers (CAOs), Controllers, Financial Operating Officers, Vice-Presidents (VPs) of Accounting, VPs of Finance, VPs of Financial Reporting, Directors of Finance, and Directors of Accounting (Suh et al. 2020).

There is evidence, however, that the governance structures designed to prevent financial misreporting often fail. The 14th Global Fraud Survey reveals that 46% of the financial executives interviewed provide justification for unethical reporting conduct when they perceive pressure to meet financial targets (EY Global Fraud Survey 2016). Another analysis completed by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO) indicates that the percentage of controllers’ participating in financial fraud cases during 1998–2007 increased strikingly (by 61.9%), relative to the previous 10 years (Beasley et al. 2010). In addition, the 2018 survey conducted by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE 2018) reveals that only 4% of fraud cases are detected by external auditors. Collectively, these studies reveal ineffective oversight and raise important questions about the causes of financial misreporting. These questions include: Why do financial executives become desensitized to unethical reporting conduct? Does the tone set by top management mitigate or magnify the likelihood of financial executives engaging in fraud? Do external auditors accurately incorporate the situational context in which financial executives are immersed (e.g., the presence of a slippery slope and tone at the top) into their understanding of fraud risk factors? We address these questions in two separate, but related experiments by examining the combined effects of slippery slope and tone at the top on financial executives’ reporting decisions and external auditors’ assessments of fraud risk.

It is important to examine management tone and the slippery slope together because organizational power structures and escalation from minor to major violations are both considered to be primary sources of organizational wrongdoing, such as financial fraud. The theory of Normal Organizational Wrongdoing (Palmer 2012; Palmer and Maher 2006) proposes that organizational wrongdoing is a normal behavior (rather than some form of criminal instinct) that results from social contexts and escalations from harmless to serious acts. The tone set by management is one example of an important social context that can lead to fraud (Palmer 2012). By studying the joint effects of management tone and the slippery slope, we are able to offer the first empirical test of several propositions of normal organizational wrongdoing.

According to Palmer (2012) and Palmer and Maher (2006), most wrongdoing is not the result of deliberately wrong or illegal action for personal gain, but rather wrongdoing results from organizational power structures, organizational norms, and from progressing from small to significant wrongdoings. They propose that the right organizational conditions, combined with small indiscretions, facilitate rationalization and the numbing processes described by Bandura (1999) that ultimately lead to problems like financial fraud. They also propose that problems such as financial fraud can be solved if managers are more careful not to pressure or instruct subordinates to start down a slippery slope by violating small rules. That is, normal organizational wrongdoing theory proposes that preventing financial fraud is not about training employees about illegal acts (because they already know what is legally or morally wrong), but instead calls for firm management to avoid creating pressure for subordinates to engage in minor indiscretions. Thus, theory indicates a critical need to examine the important interplay between management tone and movement from small indiscretions to major violations.

Research in organizational behavior and behavioral ethics has put forth the notion of a slippery slope as a gradual, incremental progression of minor misdeeds to major ones, leading individuals to view their misconduct as ethical when it is not. That is, there is a numbing effect associated with the slippery slope (a similar effect is called neutralization) (Ashforth and Anand 2003; Bandura 1999; Chugh and Bazerman 2007; Moore and Gino 2013). As a result of this numbing to ethical violations, decision makers can become blind to their subsequent unethical actions. However, the existence of a slippery slope is based largely on anecdotal evidence. We address this gap in the literature and offer the first direct tests to investigate the causal effects of sliding down the slippery slope (i.e., violating a minor rule before making a decision to engage in fraud) on the misreporting decisions of financial executives and oversight of these decisions by auditors. Further, we simultaneously examine the effects of the slippery slope in the presence of different tones at the top set by CFOs.

The tone at the top is considered vital to the health of the financial reporting system and essential to creating a culture of integrity, honesty, and ethical behavior in a firm (IIA 2016; ACFE 2006; COSO 1987). The ACFE and the Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) state that the tone at the top creates problems for an organization when (1) management appears to care more about results than ethics, and (2) when employees fear repercussions from top management (IIA 2016; ACFE 2006). Aligned with the view of ACFE and IIA, auditing standards have assumed that an intimidating and aggressive tone set by top management indicates a significant risk of financial statement fraud (e.g., Statement of Auditing Standards (SAS) No. 99 (AICPA 2002)). Theoretical models in organizational behavior, however, propose that non-aggressive or kind tones can lead employees to engage in unethical behavior as a way to please their superiors and/or to help their firms (Umphress and Bingham 2011). From this perspective, non-aggressive and kind tones may cause misreporting behavior when financial executives view misreporting as beneficial for both the firm and the firm leaders that the executives respect. There is a clear disconnect between theories espoused by the auditing profession and theories of pro-organizational behavior in management literature.

We test these competing perspectives by manipulating the tone created by the CFO as positive (kind attitude toward employees and unaggressive attitude toward meeting earnings targets) or negative (unkind and aggressive attitude) to investigate how tone at the top influences the likelihood of both misreporting behavior by financial executives and auditor responses to executives’ decisions. Further, we examine how the tone set by top management can enable financial executives who chose to violate a minor rule (i.e., slide down the slippery slope) to engage in unethical financial reporting behavior. This approach also allows us to address the call for fraud research investigating the role of situational factors and minor indiscretions leading to more egregious behaviors, through the use of creative research methods (Anand et al. 2015).

In Study 1, we collect a sample of 65 practicing controllers and 69 executive MBAs to examine the effects of tone at the top and the slippery slope on decisions to misreport earnings. Our findings reveal that financial executives are more willing to engage in misreporting behavior (i.e., intentionally overstate earnings) when the CFO’s tone is positive, relative to when the CFO’s tone is negative. These results challenge several existing assumptions and expectations that standard setters, academics, and practitioners currently have about the nature of tone at the top. That is, we find that intentional misreporting of earnings can be promoted to a greater extent by a positive tone relative to a negative tone, which favors the theoretical model of pro-organizational unethical behavior proposed by Umphress and Bingham (2011). In addition, results indicate that executive MBAs and controllers are just as likely to misreport earnings whether or not they have begun to slide down the slippery slope when the tone set by the CFO is positive. However, when the CFO tone is negative, the effects of the slippery slope are opposite of existing assumptions and expectations. Specifically, when the CFO tone is negative, financial executives who slide down the slippery slope (i.e., they violate a minor rule before making decisions about misreporting earnings) are less likely to misreport earnings than are financial executives who have not started down the slippery slope.

These results are important for theory, practice, and standard setting because they challenge the notion that minor indiscretions lead decision makers to engage in more serious misdeeds such as earnings management and financial fraud. Instead, the results suggest that a negative tone at the top may not be the primary threat to financial reporting quality, although it is currently espoused in the accounting literature. Our findings also demonstrate that CFO tone changes the way financial executives respond to the presence of a slippery slope. Given the nature and vital importance of findings in Study 1, we investigate in Study 2 the potential for threats created by the tone at the top and the slippery slope to go unnoticed during the external audit process. Results from an experiment using the same scenario that was presented to financial executives in Study 1 indicate that auditors increase assessments of fraud risk for a negative tone set by the CFOs relative to a positive tone, and that they do not react to evidence of a slippery slope.

Taken together, findings from the experiments suggest that factors prompting financial executives to engage in misreporting conduct are not consistent with many expectations in the literature and are not consistent with the factors that heighten auditors’ concerns about potential risk of fraud. For practice, these mismatches raise the need for regulators to draw professionals’ attention to the potential for a positive tone at the top to elicit unethical reporting conduct.

Study 1: Financial Executives’ Misreporting Conduct

Top management (e.g., the CFO) is considered one of the four cornerstones of corporate governance because of its strong influence in setting the overall tone for governance (Cohen et al. 2002; Gramling et al. 2004). As the second–in–command, who is focused on investors and other external relations, the CFO is significantly “moving away from scorekeeper to business partner” (Ernst and Young 2008, p. 7). These executives “work in close proximity to [top management] and form strong personal relationships with them” (Eskenazi et al. 2016, p. 42). At the same time, they are “the first line of defense against overly aggressive accounting and reporting practices” (Howell 2002, p. 20).

We investigate the financial reporting decisions of controllers because of their important role in the external financial reporting process and their potential to be influenced by executive management’s tone. Controllers’ responsibilities, in particular the oversight of financial reporting quality, require them to fiercely maintain their independence (Ezkenazi et al. 2016) from “top management’s overly aggressive accounting and reporting practices” (Howell 2002, p. 20). However, controllers typically report directly to top management, such as the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) and/or the CFO, and they can incur significant pressure from executive management. In recent years, the role of the controller has evolved from “bean counter” to “business partner” (e.g., Burns and Baldvinsdottir 2007; Granlund and Lukka 1998; Howell 2002; Zorn 2004), leading controllers to “work in close proximity to [top management] and form strong personal relationships with them” (Eskenazi et al. 2016, p. 42). The organizational environment shaped by top management’s tone at the top therefore has the potential to significantly influence controllers’ misreporting decisions.

Importantly, the number of financial executives interviewed who would justify unethical reporting behavior has increased since 2016 (EY Global Fraud Survey 2018). Increases in alleged unethical reporting behavior by financial executives and their willingness to justify misreporting conduct raise important questions about the effectiveness of current governance systems in organizations. For example, how do financial executives become desensitized to unethical conduct and slip down the path to misreporting conduct? And, how does the tone set by top management influence executives’ path to unethical reporting behavior? To date, there is a paucity of research examining these issues.

We address these voids by using the Theory of Normal Organizational Wrongdoing, which posits that organizational participants become involved in unethical conduct (e.g., financial statement fraud) because of the influence of proximal social contexts such as situational environment set by top management (Palmer 2012; Palmer and Maher 2006). The situational social influence explanation, for example, views organizations as a locus of social interactions conducive to continual exposures of organizational participants (e.g., financial executives) to the attitudes and behaviors of other social actors in the surrounding environment such as the tone set by top management (Palmer 2012). The close working relationship with the CFO provides ‘cues’ for what is the ‘right’ reporting behavior and creates opportunities for financial executives to evaluate and align their reporting decisions with the expectations of the CFOs in an escalating fashion. Unlike the dominant perspective of organizational wrongdoing that views individuals’ unethical behavior as a result of their deliberate (and possibly criminal) mind-sets, the alternative explanation proposed by the theory of normal organizational wrongdoing argues that organizational participants become immersed into wrongful conduct in a gradual, incremental manner through a series of decisions, escalating from minor to major acts (Palmer 2012; Palmer and Maher 2006).

The Slippery Slope

The slippery slope phenomenon has been described by researchers in organizational behavior (e.g., Ashforth and Anand 2003; Palmer and Maher 2006; Palmer 2012) and behavioral ethics (e.g., Chugh and Bazerman 2007; Moore and Gino 2013; Tenbrunsel and Messick 2004). Ashforth and Anand (2003) proposed “incrementalism” to advance the idea that organizational corruption stems from small, harmless acts which then spiral into significant deviant conduct. Similarly, Tenbrunsel and Messick (2004) postulate that the slippery slope effect consists of a “psychological numbing” where exposure to repetitive routinization of unethical dilemmas or practices creates reference points that are used to assess similar decisions. Moore and Gino (2013) draw on a large body of empirical evidence to theorize that biases and cognitive failures, such as “change blindness” (Chugh and Bazerman 2007) or the influence of other social actors, can help to facilitate moral neglect, moral justification or moral inaction, persuading individuals to believe that they are behaving ethically when they are not. The general conclusion from this literature is that large frauds are the eventual result of small, more harmless acts of misconduct.

While there is much theoretical discussion of the slippery slope, only a handful of studies have provided empirical evidence supporting the notion that a slippery slope can lead to financial fraud (Brown 2014; Free and Murphy 2015; Schrand and Zechman 2012; Suh et al. 2020). Brown (2014), for example, examines whether exposure to egregious examples of earnings management lead to rationalization of less egregious forms of earnings management. His research focuses on perceptions of acceptability that result from the ability to rationalize earnings management. Schrand and Zechman (2012) investigate firms identified by Security and Exchange Commission Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Releases (AAER) as managing earnings and argue that overconfident, optimistic biases on initial earnings led these firms to slip into misreporting behavior. While the research documents an association between optimistic bias and misreporting, there again is no evidence of a causal effect of smaller indiscretions, unrelated to a reporting context, spiraling out of control into financial fraud. Research further suggests that individuals are more influenced by small increases in misconduct, relative to large increases. Gino and Bazerman (2009) find that observers are more tolerant of others’ misconduct when it happens in small increments rather than all at once. In a similar vein, results of Brown et al. (2014) demonstrate that gradual increases in compensation incentives, compared to an abrupt change, lead some individuals to engage in greater misreporting behavior. Welsh et al. (2015) also report that gradual increases in compensation incentives enable subjects to morally disengage and justify their questionable conduct relative to a sudden increase in compensation.

These prior experiments provide some evidence of a progression of unethical behavior, primarily stemming from escalation of commitment, and the role of moral disengagement in the slippery slope phenomenon. Findings from prior work corroborate with the incrementalism narratives of Free and Murphy (2015) and Suh et al. (2020). In Free and Murphy (2015, p. 21), interview narratives of prison inmates reveal that co-offending behavior (cooperation with a group of two or more individuals to commit white-collar crime) started in “a small scale and subsequently escalated over time” (p. 38). Similarly, Suh et al. (2020) find that the majority of C-suite financial executives who were involved in and indicted for accounting fraud claimed to have difficulty pinpointing exactly when their misreporting behavior started, which suggests that major frauds may have begun as something small and potentially very ‘innocent.’ None of these studies, however, have examined the causal effects of a slippery slope on misreporting behavior—a clean test to determine whether individuals’ choices to engage in minor misdeeds (e.g., breaking a minor rule) can actually cause them to later engage in major unrelated misconducts (e.g., misreporting/fraudulent behavior). We address this gap in our understanding of the causal effects of a slippery slope.

According to Palmer and Maher (2006, p. 365), organizational wrongdoing is characterized as “a series of [individual and group] decisions that constitutes a slow progression toward and across the line between right and wrong behavior, has [unintended] consequences […], and represents small departures from prior behaviors.” Implicit in this conception is the use of recent, questionable practice to evaluate prospective, wrongful behavior that is different than the previous one (Palmer 2012). That is, any questionable act can lead a decision maker to be more open to engaging in a subsequent, more serious questionable act. At the heart of the theoretical propositions that small misdeeds change future judgments about engaging in larger misdeeds is the underlying psychological notion of the numbing effect. Theory suggests that individuals become less sensitive to unethical activities over time because they become numb or blind to ethical violations. This numbing effect causes decisions makers to perceive ethical violations as increasingly less meaningful, after small ethical violations have been made (Ashforth and Anand 2003; Chugh and Bazerman 2007; Moore and Gino 2013). When decision makers become numb to the importance of ethics and rules, they also become more willing to engage in more serious violations. Retrospective accounts of C-suite financial executives, for example, suggest that witnessing slippery slope decisions in non-reporting contexts led some executives to engage in misreporting in subsequent reporting decisions (Suh et al. 2020).

Building upon the prior research, we propose that financial executives who begin to slide down the slippery slope (i.e., choose to break a minor rule before making a decision about misreporting earnings) will be more likely to engage in serious misreporting conduct. More specifically, we expect that financial executives who choose to break a minor company rule will be more likely to intentionally understate expenses in a subsequent decision. Breaking a minor rule will desensitize executives to the importance of rules and increase the likelihood that they are willing to violate significant rules related to financial misreporting. This leads to our first hypothesis:

H1

Financial executives will be more likely to intentionally understate expenses after they violate a minor rule (start down the slippery slope) relative to before they violate a minor rule.

Financial Executives’ Responses to Tone at the Top

Financial executives, as one of the corporate watchdogs, must maintain independence in judgment from top management to ensure objective and reliable financial reporting processes (Eskenazi et al. 2016; Maas and Matejka, 2009). Their incentives to oversee financial reporting quality, however, may depend on the tone set by top management (Hambricks and Mason 1984; Patelli and Padrini 2015). According to upper echelons theory, tone at the top provides an environment conducive to influencing financial executives’ judgment and decision-making through a filter woven by top management’s values and goals (Hambricks and Mason 1984). While research demonstrates that tone at the top is a key factor of ethical practices in business organizations (Patelli and Padrini 2015), there is scarce research to support causal effects of management’s tone at the top on reporting practices. The lack of empirical research related to this important issue largely results from the fact that tone at the top is difficult to measure reliably using archival data. Due to the lack of quality archival measures of tone, research has largely focused on management fixed effects (i.e., management characteristics) and their effects on organizational outcomes and strategic choices. Management fixed effects are known to affect strategy and performance (Chatterjee and Hambrick 2007), discretionary accounting accruals (Ge et al. 2011), voluntary disclosures (Bamber et al. 2010), tax avoidance behavior (Dyreng et al. 2010), and earnings management (DeJong and Ling 2010; Jiang et al. 2010).

Prior archival research has used demographics (i.e., birth/cohort/age, gender, MBA education), functional backgrounds (i.e., accounting/finance functions, legal or general management), and military experience as measures of characteristics that differentiate managers in order to explain differences in corporate decision-making across executives. Evidence on the explanatory power of easily observable characteristics on managerial decision-making remains mixed. Some studies find that demographic characteristics are correlated with decision strategies. For example, Bertrand and Schoar (2003) find that CEOs from older generations are more conservative when making decisions about capital expenditures and financial leverage relative to younger CEOs. On the other hand, follow-up analyses of Bamber et al. (2010) and Ge et al. (2011) show only weak explanatory power of demographic characteristics on executives’ accounting choices. Other studies find no relationship at all between demographics and executives’ decisions. For example, Dyreng et al. (2010) report no significant association between observable characteristics and firms’ effective tax rates (a proxy measure of corporate tax avoidance behavior), suggesting that these characteristics lack explanatory power. Instead, the authors propose that the less observable “tone at the top” is what likely drives executives’ fixed effects on corporate decisions.

Tone at the top is defined by Amernic et al. (2010) as the shared set of values that reflects the attitudes and actions of top executives (e.g., the CFOs’ words and deeds) and by Schwartz et al. (2005) as examples and actions of top management (CEOs and CFOs) that is central to the overall ethical environment of a company. COSO (1987) describes tone and company culture as the most important elements for maintaining the integrity of financial reporting. The ACFE (2006) describes the tone at the top as “the ethical atmosphere that is created in the workplace by the organization’s leadership.” The ACFE also states that when “upper management appears unconcerned with ethics and focuses solely on the bottom line, employees will be more prone to commit fraud because they feel that ethical conduct is not a focus or priority within the organization.” Similarly, the IIA (2016) indicates that tone is likely to lead to fraud and failures to report fraud when “employees constantly fear being rebuked or, worse, fired.” The various definitions of tone at the top proposed by prior research as well as COSO, ACFE, and IIA suggest that tone is multidimensional and incorporates top leaders’ attitudes and actions toward employees and financial reporting. This construct is difficult to reliably measure using archival data, and prior research has paid relatively little attention to causal effects of tone at the top on financial executives’ reporting decisions.

Accounting researchers and regulators have long assumed that aggressive tones set by executive management represent major problems for misreporting and financial fraud. Aggressive tones are considered reflective of an attitude that favors rule-breaking behavior and intimidating behavior. An environment of intimidation and its pervasive effects on financial reporting decision-making is listed in the Statement on Auditing Standards (SAS) No. 99, Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit (AICPA 2002), as one of the primary risk factors associated with fraud. However, there are reasons to believe that non-aggressive tones lead to a culture of misreporting, and that current assumptions about tone, prevalent in regulation, require empirical testing.

Non-aggressive tones at the top can elicit unethical pro-organizational behavior in employees. Umphress and Bingham (2011) argue that employees act on behalf of the organization and/or leaders with little or no apparent personal motives, and that they will violate core societal values or standards/laws of proper conduct because they want to reciprocate favorable treatments received from their leaders within the organization. Interview narratives analyzed by Suh et al. (2020, p. 20) indicate that some C-suite financial executives slipped into misreporting conduct because they wanted their supervisors to benefit. For example, one of the financial executive interviewees drew on the CFO’s kind attitude toward him and his staff as well as his non-aggressive plea toward earnings to explain his misreporting decisions:

The CFO was never anything but nice to me and my staff in that matter. He was angry with operations, and he was pleading with us to stay the course and help get the company back where it was. (Tom-Director of Finance)

This excerpt suggests that those who committed fraud often did so in order to help their leaders and their company succeed, rather than as a result of fear of reprisal. It also indicates that non-aggressive, kind leaders, with the respect and admiration of subordinates, could push employees to misreport earnings. An experimental setting allows for rigorous testing of the alternative theories of the effects of tone on unethical behavior.

Building from these discussions, it appears that both negative and positive tones could help push financial executives into a willingness to misreport earnings. A negative tone set by the CFO (unkind attitude toward employees and aggressive attitude toward earnings target) could lead to more misreporting behavior because financial executives feel pressure to manage earnings and fear the negative personal repercussions of not managing earnings (Amernic et al. 2010). A positive tone set by the CFO (kind attitude toward employees and non-aggressive attitude toward earnings target), on the other hand, could lead to more misreporting behavior by financial executives because they want to engage in pro-organizational behaviors (Suh et al. 2020; Umphress and Bingham, 2011). This leads to the following non-directional hypothesis:

H2

Financial executives will make different misreporting decisions depending upon whether the CFO’s tone at the top is negative (unkind and aggressive) or positive (kind and non-aggressive).

Study 1: Research Method

We employ a 2 × 2 between-participant randomized experiment to investigate the effects of slippery slope (violation of a minor company policy before or after facing the opportunity to engage in serious misreporting conduct) and CFO tone (negative or positive) on financial executives’ reporting decisions involving the misreporting of expenses.

Participants

A total of 72 experienced, Dutch controllers and 73 executive MBA students (hereafter referred to as financial executives) participated in the first study. The final sample included 65 controllers and 69 MBAs after excluding participants who failed to provide correct answers to an attention check question. For the 65 controllers, 91% have a Master degree, and 52.3% are certified registered controllers or in the process of obtaining this certification. The majority of these participants hold a controllership-related job title (82%), and the rest work as a Chief of Finance/Financial Manager (18%). On average, controllers have 8.6 years of experience in financial reporting. Controllers were recruited from the Dutch Association of Controllers and three different Dutch universities that offer a part-time executive professional program titled “Registered Controller” or “Certified Controller,” which is equivalent to the U.S. Certified Management Accountant (CMA) designation. During the program, one of the authors administered the experimental materials and de-briefed the participants. All data collection sessions were conducted in English. The executive MBA students came from a large, public US university and volunteered to participate during a scheduled class meeting. On average, the executive MBA participants have 3.6 years of professional experience.

Experimental Design and Procedure

The experiment was conducted under controlled laboratory conditions. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the four experimental treatment groups. The experimental materials instructed participants to assume the role of a controller for a large division of a consumer goods company. Participants were informed of the CFO’s overall tone, which described the CFO’s beliefs about employees’ role in making reporting decisions, attitude toward meeting or beating analysts’ earnings per share (EPS) forecasts, and reputation for being kind or unkind to employees. After reading the description of the CFO’s overall positive or negative tone, participants analyzed 2 year-end issues. One issue consisted of an opportunity to violate a minor rule in a non-reporting context, and the other issue involved an accounting estimate for warranty expense (derived from Brown 2014). After analyzing the year-end issues, participants responded to manipulation/attention check items, debriefing questions, and demographic items.

Our warranty decision context is derived from the earnings management case used in Brown (2014). The case involves an accounting estimate for a large division of a consumer goods company. Participants were informed of a new product that the division started selling with a 10-year warranty and were instructed to estimate and record expected warranty expense for this new product. While evaluating a range of possible outcomes for the warranty expense, participants received information about the division’s operational profit prior to accounting for the warranty expense ($42 million dollars) and the operational profit target for the division ($40.5 million dollars) that would enable the company to meet the consensus analyst forecast of EPS. After reading information about the current and expected operational profit target, participants read about the potential consequence of meeting or failing to meet the EPS forecast, the different scenarios of warranty expense that could be recorded, and the effects of the different scenarios on the division’s profit target and the firm’s ability to meet the EPS forecast.

Independent Variables

The Slippery Slope manipulation involved the opportunity to violate a minor and inconsequential company rule. All participants were given this opportunity, but half made a decision about violating a minor rule before making a decision to engage in far more serious misreporting of earnings, and half of the participants made a decision regarding the violation of a minor rule after deciding whether to misreport earnings. The minor rule had little or no implication for the firm, and no implication for decisions about earnings. It was critical to provide participants with an opportunity to violate a rule that was unrelated to misreporting earnings for three reasons: (1) theory predicts that psychological numbing results from small ethical violations that do not need to be related to more serious ethical violations; (2) making a decision to engage in a minor misreporting of earnings and then major misreporting of earnings would be confounded with escalation of commitment; and (3) even minor misreporting of earnings would represent violations of professional standards for controllers (a serious violation), while breaking the minor gift rule does not relate directly to violations of controller duties or financial reporting. Thus, the minor violation of the company rule provides a clean measure of the slippery slope and offers controllers a situation where the initial, minor infraction does not require them to violate professional standards. We examine the misreporting decisions of participants who choose to violate the minor rule, and we compare those who violate a minor rule before making a misreporting decision (i.e., participants who have started to slide down the slippery slope) to participants who violate a minor rule after making a misreporting decision (i.e., participants who have not started down the slippery slope before making a decision about a serious violation).

To ensure that the instrument included decisions that represented both minor and major violations, we created the violations in collaboration with practicing controllers and CFOs. We also sent our two decisions to practicing and high-level controllers (several at Fortune 500 firms) and asked them to rate each decision with regard to the severity of ethical and professional violations represented by the decision. The seven responding controllers all indicated that our minor violation decision (i.e., giving away merchandising items) represented a very minor infraction, while our major violation (i.e., misreporting of expenses) was serious and represented intentional earnings management.

All participants in the experiment read the following statement that described background information on the year-end issue involving marketing items (half of the participants made this decision before estimating warranty expense and half made the decision after):

The CFO has asked you to get small gifts for all of the employees in your division to celebrate the year-end, and he indicated that this should be done without spending very much money. The CFO stated that he wants you to make a decision and get it done quickly. You recently noticed that there is a large supply of high quality coffee mugs and polo shirts with the company logo sitting in a storage facility. These items were produced for marketing purposes. There is a company policy that states that marketing items cannot be given to employees. You asked the marketing department about these items, and you have learned that they are leftovers from previous marketing efforts. Marketing has indicated that these items are no longer being used for marketing, and the items will likely be given away to charity or recycled in the near future.

Participants then indicated which item (coffee mugs or polo shirts) they believed would be the best gift for employees and the likelihood that they would choose to give each item to the division’s employees using an 11-point Likert-type scale (− 5 = Definitely would not give mugs or shirts, 0 = uncertain, + 5 = Definitely would give mugs or shirts). We classify participants who select “1” or higher for either mugs or shirts as having started down the slippery slope because they decided that they would violate the company rules regarding marketing items.

Financial executive participants read the following paragraph that described the CFO’s overall tone:

From your personal meetings with the CFO and prior experiences, you know that the CFO believes that employees should focus on (meeting their earnings targets) [making good decisions], and he (pushes very aggressively) [does not push aggressively] to meet or beat analysts’ EPS forecasts. The CFO also has a reputation for being (unkind) [kind] to employees, and it is not unusual for him to (yell at employees in the hallways or consider firing them when they fail to meet their performance targets) [praise employees in the hallways or reward them for making good decisions.]

A negative or positive tone at the top set by the CFO is manipulated using two dimensions: kind or unkind attitude toward employees and non-aggressive or aggressive about meeting EPS forecasts. The use of a multidimensional construct is widely used by organizational behavior research to match general predictors with general outcomes (Edwards 2001). For example, overall job performance is viewed as an aggregate of performances on specific tasks, enabling researchers to “match factorially complex outcomes with factorially complex predictors” (Edwards 2001, p. 149). Sweeney et al. (2017) and Barrick et al. (2005) also rely on different dimensions to manipulate positive or negative interpersonal performance (interpersonal abilities, cooperation, communication, and client orientation). The use of a multidimensional construct allows us to holistically represent a complex theoretical construct of tone at the top (Amernic, et al. 2010; Schwartz et al. 2005). Further, this multidimensional construct captures the two primary aspects of tone described in the literature and in professional guidance: attitudes and actions toward employees and toward financial reporting.

Dependent Variable

The use of a direct questioning approach (instructing participants to indicate the amount of warranty expense that they would record) may elicit socially desirable response behavior, leading controller participants to select the amount of expense that is consistent with social norms and expectations (e.g., expectations that controllers do not intentionally understate expenses). To avoid a social desirability bias (e.g., Fisher 1993) that is common in decisions involving ethical values, we employ an indirect questioning approach such that participants can project their true judgments on a referent other (e.g., Clement and Krueger 2000; Fisher 1993; Cohen et al. 1993, 2001; Mikulincer and Horesh 1999). This approach is consistent with Brown (2014), who asked decision makers to evaluate the slippery slope decisions of a referent other in order to avoid self-presentation effects.Footnote 1 The dependent variable (Warranty Expense) is therefore measured using the following question and related scale:

What do you believe other controllers in a similar situation would choose to do? Please indicate your response by circling a number on the scale below.

3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Most Controllers Would Record $1,500,000 or Less | Undecided | Most Controllers Would Record $2,000,000 or More |

Study 1: Results

Preliminary Testing

To verify that the manipulation of CFO tone was appropriately recognized by the participants, we asked participants about the CFO’s attitude described in the case. Participants who failed this attention check were not included in the hypotheses testing. Seven controllers and four MBA students failed the attention check, resulting in sample sizes of 65 controllers and 69 MBAs.

Hypotheses Testing

The first hypothesis (H1) predicts that financial executives will be more likely to misreport earnings (record warranty expense of $1,500,000 or less) when they start down the slippery slope (i.e., violate a minor company rule before making a misreporting decision) relative to when they have not started down the slippery slope. The second hypothesis (H2) posits that CFO tone will influence financial executives’ misreporting decisions.

Given that we conduct a 2 × 2 factorial experiment involving two categorical manipulations and a scaled response variable with evidence of a significant covariate, ANCOVA is the most appropriate statistical technique for testing hypotheses related to the effects of the experimental manipulations. To test H1 and H2, we performed a 2 × 2 ANCOVA with Warranty Expense as the dependent variable, Slippery Slope and CFO Tone (aggressive vs. non-aggressive) as independent variables, and Others’ Willingness as a covariate.Footnote 2 Before running the ANCOVA, we split the sample into those financial executives who chose to violate the minor company rule and those who did not violate the rule. Our analyses focus only on those financial executives who chose to violate the minor rule, and we use the order of their decisions to represent presence or absence of a slippery slope condition. This allows us to compare financial executives who chose to violate a minor rule before facing the opportunity to misreport earnings with financial executives who chose to violate a minor rule after making the misreporting decision. The hypotheses tests examine only those participants who chose to violate the minor rule because only participants who violated a minor rule before making the earnings misreporting decision started down the slippery slope, and it is important to compare these participants to those who violated the rule after making the misreporting decision. Otherwise, participants who started down the slippery slope (who chose to violate a minor rule) would be compared to participants who did not choose to violate a minor rule, and there would be multiple explanations for differences between the two groups. Of the 134 participants who completed the experiment, 94 chose to break a minor rule. Our statistical tests are based on these 94 participants who chose to violate the minor rule. The ANCOVA model in Table 1 includes participants who violated the minor rule.

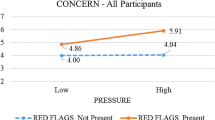

Results in Table 1 and Fig. 1 indicate a non-significant main effect of Slippery Slope (F = 2.47, p = 0.119, two-tailed), a significant effect of CFO’s Tone (F = 4.82, p = 0.031, two-tailed), and a significant interaction (F = 7.58, p = 0.007, two-tailed) between Slippery Slope and CFO’s Tone on the warranty expense decision. The main effect of CFO Tone cannot readily be interpreted as a result of the significant disordinal interaction effect. We use simple effect tests to further examine the meaning of the interaction effect. When the CFO tone is positive, Fig. 1 shows that financial executives consistently choose to misreport earnings (i.e., understate expenses), and the slippery slope has little influence on their behavior. A non-significant simple effect of slippery slope on misreporting decisions when tone is positive indicates that sliding down the slippery slope (mean = − 1.11) does not significantly increase misreporting (p = 0.418, two-tailed) relative to not sliding down the slippery slope (mean = − 0.78).

The results change when the CFO tone is negative. Financial executives assigned to a negative CFO tone are less likely (p = 0.002, two-tailed) to misreport earnings when there is a slippery slope (mean = 0.67), relative to when there is no slippery slope (mean = − 0.92). These results indicate that the effects of a slippery slope on misreporting expenses are more complex than what has been assumed. In addition, the effects are dependent upon the CFO tone. A positive tone at the top appears to push controllers to misreport, regardless of prior, minor indiscretions. This supports the perspective that a positive CFO tone fosters executives’ willingness to engage in misreporting and runs counter to the perspective that misreporting is a result of fear of negative tone at the top. Financial executives who violated a minor rule under the negative tone at the top, however, appear to refuse to let themselves slide down the slippery slope on behalf of a CFO who is unkind to employees and aggressive about meeting EPS targets. These results challenge many of our assumptions about the effects of CFO tone and the operation of the slippery slope. Most importantly, a positive CFO tone consistently pushes financial executives, both practicing controllers and executive MBAs, toward a willingness to misreport.Footnote 3

Post-experiment Debriefing: Perception of Warranty Expense and Rules

Participants responded to debriefing items aimed at understanding how they rationalized their decisions about determining warranty expense and violating company policy. Our first group of debriefing items are related to participants’ decisions to determine warranty expense and include: (1) negative consequences if one fails to meet the division’s earnings targets (Negative Consequences), (2) pressure to decrease the warranty expense (Pressure Warranty Expense), and (3) the notion that understating warranty expense is a harmless or harmful decision for others (Harmless Warranty Expense). Our second group of debriefing items are related to participants’ perceptions about breaking minor rules and include: (1) the perceived pressure to give the old marketing items to the employees (Pressure Gift), (2) the assessment of breaking minor rules as a harmless decision for others (Harmless Gift), and (3) the belief that it can be ethical to violate rules (Ethical to Violate Rules). The debriefing items were measured based on 7-point Likert-type scales.

We performed t tests on the reporting decision debriefing items and rules-related debriefing items comparing the group of participants who had slipped (chose to break the minor rule) and the group of participants who had not slipped (did not choose to break the minor rule). Results of t tests presented in Table 2, Panel A, indicate that participants’ perceptions of the warranty expense decision did not differ significantly between those who had slipped and those who had not slipped. Results of Table 2, Panel B, show that participants believed that giving the gifts to employees was more harmless (p < 0.001) when they had slipped (mean = 5.79), relative to when they had not slipped (mean = 4.08). This result is consistent with a psychological numbing perspective of the slippery slope (Tenbrunsel and Messick, 2004; Chugh and Bazerman, 2007).Footnote 4

Supplemental Analysis

Given that the effects of a negative tone on financial executives’ willingness to slide farther down the slippery slope differ from much of the theoretical literature and anecdotal evidence (i.e., a negative tone reduces the likelihood of engaging in misreporting, rather than increasing the likelihood of misreporting), we conduct further analyses to better understand this result. Our pattern of results suggests that negative tones are not resulting in psychological numbing, but they are instead increasing moral awareness. That is, results suggest that negative tones, but not positive tones, heighten the moral awareness of participants who had already violated a minor rule, which causes them to be less likely to misreport warranty expense. To examine whether negative CFO tones have the capacity to activate more moral awareness after a subordinate has violated a minor rule, we examine whether a negative tone could increase concerns about the harm caused by engaging in misreporting.

To test this theory, we employ regression analyses because the independent variables of interest are continuous measures, rather than categorical. We regress the debriefing items related to perceptions of harm on participants’ reporting decisions using the sample of participants who had slipped. Results of regression analyses presented in Table 3 reveal a negative association between Harmless Warranty Expense and the Warranty Expense dependent variable (p = 0.001) when CFO’s tone is negative and there is a slippery slope. In contrast, when the CFO’s tone is positive and there is a slippery slope, we do not find any significant association between Harmless Warranty Expense and Warranty Expense. We also do not find a similar difference between perceptions of harm related to the minor indiscretion of giving the free gifts. These results indicate that negative tones increase perceptions of harm after the violation of a minor rule, supporting the theory that a negative tone activates heightened moral awareness after the violation of a minor rule, but that positive tones do not activate such moral awareness. Collectively, our results indicate that contextual factors such as tone at the top set by the CFO can magnify or mitigate the loss of moral compass and its related effects on financial executives’ reporting conduct.

Study 2: External Auditors’ Responses to the Slippery Slope and Tone at the Top

Audit standards promote the notion that aggressive management tones are key risk factors associated with fraud (e.g., SAS No. 99 (AICPA 2002)). Following the COSO (1992) framework, the relevant professional standards (e.g., PCAOB AS 2201, Para. 25) outline three factors that must be considered by auditors when evaluating control environment effectiveness at publicly traded companies. They are (1) whether management’s philosophy and operating style promote effective internal control over financial reporting; (2) whether sound integrity and ethical values, particularly of top management, are developed and understood; and (3) whether the board or audit committee understands and exercises oversight responsibility over financial reporting and internal control.

Despite the guidelines offered in the professional standards, the measurement of tone at the top can be difficult, and auditors are often trained how to evaluate tone with the use of case examples demonstrating negative repercussions of aggressive tone at the top. For example, until its bankruptcy in December 2001, Enron’s corporate culture was characterized by a grueling performance evaluation culture that was implemented by its then company president, Jeffrey Skilling. To do so, Skilling established highly aggressive performance targets where the top performers had the potential to earn significant bonus compensation and low performers were often terminated. Clearly, the resultant company culture was manifested in large part due to management’s highly aggressive, unkind “philosophy and operating style.” As a result of this case and many others, auditors are taught to recognize negative management tones as signals of financial fraud risks. Therefore, we anticipate that auditors will increase assessments of fraud risk for negative CFO tones relative to positive CFO tone, while financial executives who were faced with the same case information were actually more likely to engage in fraud in the presence of positive tones.

H3

Auditors will assess higher levels of fraud risk when the tone set by the CFO is negative (aggressive and unkind), relative to when the tone set by the CFO is positive (non-aggressive and kind).

Beyond the importance of management’s philosophy and operating style, the integrity and ethical values of management are also critical for auditors when evaluating financial reporting risks. Integrity and ethical values, as well as behavioral standards, are “[communicated] to personnel through policy statements and code of conduct and by example” (Arens et al. 2017, p. 274). In fact, in its report on deterring financial statement fraud, the Center for Audit Quality (CAQ 2010) emphasizes the importance of management promoting a positive attitude toward establishing and maintaining an effective internal control system through their actions. Indeed, top management must set the proper example and always signal an intolerance for all types of unethical behavior. Simply stated, if the employees of an organization perceive that management only takes ethical actions, they are far less likely to engage in unethical behavior themselves. Drawing on the relevance of management integrity and ethical values in evaluating the risks of material misstatements, we predict that small misdeeds (i.e., evidence of sliding down the slippery slope) will lead auditors to question financial executives’ integrity and increase assessments of fraud risk.

H4

Auditors will assess higher levels of fraud risk when financial executives have violated a minor rule (started down the slippery slope) relative to when financial executives have not violated a minor rule.

Study 2: Research Method

Results of Study 1 indicate that a positive tone set by the CFOs (non-aggressive and kind attitude) is more likely to push financial executives down the slippery slope than is a negative tone set by the CFOs (aggressive and unkind attitude). In Study 2, we examine whether auditors consider cues related to the slippery slope and CFO tone when evaluating fraud risk. The second experiment involves a 2 × 2 factorial design where the manipulated independent variables are the presence/absence of a slippery slope and CFO tone. Auditors evaluate a warranty estimate decision and assess the risk of financial fraud. The instrument was evaluated by a panel of audit partners and research experts from the firms involved.

Participants

Participants are practicing senior auditors from two Big 4 accounting firms. All participants are seniors, and they have an average of 3.65 years of experience with their firms. The participants completed the task during a firm training session. Multiple authors attended the training session and administered the experiment. Ninety-three auditors participated, 11 auditors failed an attention check, and 4 did not complete the instrument, resulting in a final sample of 78 auditors.

Experimental Design and Procedure

The design of Study 2 employed the instrument from Study 1, but we slightly altered the decision context. In this experiment, auditors were asked to evaluate the warranty estimate that had already been made by the controller. The controller had determined that warranty expense should be recorded as $1,500,000 (which is an aggressive estimate). The manipulation of CFO tone was identical to the manipulation in Study 1. For the manipulation of slippery slope, auditors were informed that the controller either did or did not decide to give the gifts to the employees. Thus, this experiment examines whether auditors’ decisions are influenced by the same types of tone that caused changes in controllers’ behavior and whether auditors’ decisions are influenced by evidence that the controller has begun to slide down the slippery slope by violating a minor company rule.

Independent Variables

The manipulation of tone was identical to Study 1. To manipulate the (presence)/[absence] of a slippery slope, the following statement indicated whether or not the controller had decided to violate the minor firm rule regarding gifts:

The controller (decided to give)/[decided not to give] these items to the employees as gifts.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable captured auditors’ assessment of fraud risk:

What is the overall risk of financial statement fraud at ABC Inc.?

0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Very Low | Very High |

Study 2: Hypotheses Testing and Results

The third hypothesis (H3) posits that fraud risk assessment will be higher when the tone set by the CFO is negative relative to when the tone set by the CFO is positive. The fourth hypothesis (H4) predicts that fraud risk assessment will be higher when auditors are aware that financial executives have violated a minor rule than when financial executives have not violated a minor rule. To test these hypotheses, we performed a 2 × 2 ANOVA with Fraud Risk Assessment as the dependent variable and Slippery Slope and CFO Tone (negative vs. positive) as independent variables.Footnote 5 Results in Table 4 indicate a significant main effect of tone (F = 15.38, p < 0.001) on assessments of fraud risk, and the means are in the expected direction (mean for positive CFO tone = 4.01, and mean for negative CFO tone = 5.28). Thus, H3 is supported. Auditors perceive that a negative CFO tone increases fraud risk relative to a positive CFO tone. We also employed an alternate dependent variable where we ask auditors directly whether they believe that the CFO’s tone increases or decreases the likelihood of financial fraud (− 5 = definitely would decrease risk and 5 = definitely would increase risk). Again, there is a significant main effect of tone (F = 42.06, p < 0.001), and the negative tone is associated with increased perceived risks of financial fraud (mean = 4.10), relative to a positive tone (mean = 0.41). Further, the mean response in the positive tone treatment is not significantly different than zero (i.e., participants perceive that the positive tone has no effect on fraud risk). Again, results support H3.

There is no support for H4. Auditors’ assessments of fraud risk were not significantly influenced by the presence/absence of a slippery slope (F = 0.09, p = 0.77). It does not appear that auditors considered the violation of a minor rule to be important for their assessments of fraud risk.

Study 2: Debriefing Analyses

The debriefing analyses examine the effects of the slippery slope and CFO tone on auditors’ perceptions of the potential consequences to the controller from the CFO. Neither perceived benefits nor perceived negative consequences mediate the relationship between tone and assessments of fraud risk that was supported by hypothesis testing in the previous section. Similarly, first impressions of the CFO and trust in the controller do not mediate this relationship. It appears that audit standards and audit firms have trained auditors to respond to indicators of a negative tone with increased assessments of fraud risk, and this is the behavior that auditors exhibit, even in a case where both practicing controllers and executive MBAs were more likely to engage in misreporting when tone was positive.

We also asked auditors about their general perceptions of the relationship between financial fraud and the CFO’s attitudes toward employees and earnings in order to determine what elements of tone drive auditors’ fraud risk assessments. For attitudes toward employees (where − 5 = aggressive CFOs are more likely to cause fraud, and 5 = kind CFOs are more likely to cause fraud), auditors perceived that unkind attitudes toward employees were more likely to cause fraud (mean = − 1.6). The mean is significantly less than zero (t = 5.68, p < 0.001). Similarly, for attitudes toward earnings, auditors perceived that being aggressive about earnings was more likely to cause fraud (mean = − 3.6). The mean is significantly less than zero (t = 15.88, p < 0.001).

Discussion

We employ two experiments to examine the effects of tone at the top and the slippery slope on financial executives’ decisions to misreport income and auditors’ fraud risk assessments. The results of Study 1 involving controllers and executive MBAs indicate that financial executives have a greater willingness to misreport earnings when the CFO sets a positive tone (kind attitude toward employees and non-aggressive about meeting EPS targets) relative to when the CFO exhibits a negative tone (unkind attitude toward employees and aggressive about meeting EPS targets). Our findings also indicate that the slippery slope did not operate as anecdotal evidence would suggest, as in the presence of a negative tone created by the CFO, financial executives were less likely to misreport earnings after violating a minor rule than they were before violating a minor rule. When the CFO tone was positive, financial executives consistently exhibited willingness to misreport earnings, regardless of the presence of a slippery slope.

A negative (e.g., aggressive and intimidating) tone is listed by SAS No. 99, Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit (AICPA 2002), as one of the primary risk factors associated with financial reporting fraud. Contrary to standard setters’ expectations and some prior research (e.g., Barboza 2002; Free et al. 2007; Kets de Vries 2006; Sims and Brinkmann 2003), our results indicate that misreporting behavior is promoted by a positive tone, rather than a negative tone. These results support the theoretical model proposed by Umphress and Bingham (2011), where positive feelings about supervisors and the firm can result in pro-organizational unethical behavior. Umphress and Bingham (2011) propose that when financial performance goals are set without clear ethical goals for performance or when supervisors emulate less-than-ethical performance, employees who feel attached with their supervisors are likely to engage in unethical pro-organizational behavior.

The results of Study 1 suggest that it is important for organizational leaders such as the CFO to align financial performance goals with ethical performance goals. One way to accomplish this is for CFOs to develop reputations for ethical leadership (Nygaard et al. 2017; Treviño et al. 2000), thus instilling financial executives with ethics and values that will appropriately guide their financial reporting conduct. Another potential method for creating ethical goals is for CFOs to set specific standards for ethical reporting behavior through formal systems (e.g., in-house ethics training forums) and informal systems (e.g., communication of normative expectations) (e.g., Abernethy and Brownell 1997; Morrison 2001; Umphress and Bingham 2011). Finally, a third approach we suggest is to make financial executives aware of the potential traps associated with unethical pro-organizational behavior through simple training. Recent research finds that even a single, brief training session can effectively combat judgment and decision biases (Sellier et al. 2019), and there is a history of research indicating that awareness of certain biases, along with training of the decision mechanisms that cause the biases, can reduce their effects (e.g., Fischoff 1981; Babcock and Loewenstein 1997; Mowen and Gaeth 1992). Making financial executives aware of the potential threats associated with attachments to their superiors could effectively reduce the likelihood that kind management tones lead to unethical subordinate behavior.

Given the nature and importance of the results from Study 1, we decided to broaden this understanding to financial reporting quality assurance by examining how auditors respond to evidence of tone at the top and the presence of a slippery slope. In Study 2, we examine whether auditors perceive that financial executives are more likely to misreport earnings under different CFO tones and the evidence of violation of minor rules. Results indicate that auditors do not use information about minor violations to assess fraud risk. This would suggest that they are not trained to consider minor indiscretions to be indicative of the potential risks of more serious misreporting. Given our findings from Study 1, where controllers were not more likely to engage in misreporting if they had violated a minor rule, the auditors’ responses to this information appear appropriate. However, with regard to tone, auditors are concerned about a negative CFO tone, heightening their assessments of fraud risk for these CFOs. This is in direct contradiction to the results we find in Study 1 with practicing controllers and executive MBAs using the same experimental materials. Auditors are specifically trained to be wary of negative (i.e., aggressive) management tones, but our results provide evidence that positive (i.e., non-aggressive and kind) tones are more likely to cause financial executives to opportunistically misreport earnings in this case setting. The results reveal serious disconnects between financial executives’ actions and auditors’ beliefs and expectations, and these disconnects represent potential failures of critical governance mechanisms.

There are clear implications of the results for the audit profession. Auditors receive significant training around fraud risk assessment and how to conduct fraud brainstorming sessions. This training and the related professional standards (e.g., SAS No. 99 (AICPA 2002)) stress the risks associated with aggressive managers at audit clients. Auditors are one of the pillars of effective governance, but Study 2 reveals that they may not recognize or they may dismiss important evidence of financial misreporting risks. The 2010 COSO Fraud Study specifically identified tone at the top as a critical component of fraud risk assessment because over 70% of financial frauds involve the CEO or CFO. Auditors are specifically charged with evaluating CEO and CFO tone, but their evaluations are currently one-sided and simplistic. Auditors require training that is far more nuanced than the current training schemes, which essentially teach auditors to beware of aggressive management. Very recent research has shown that new fraud training techniques can be very effective for improving auditors’ ability to detect financial fraud (Bierstaker et al. 2017), and we propose that training to better understand the potential effects of tone and the slippery slope would represent significant improvements to audit effectiveness. It would also be beneficial for the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board to consider new fraud risk assessment regulation that does not take a one-sided approach to the effects of management tone on the risk of financial fraud.

Our findings contribute to prior research on a number of levels. First, a handful of studies have provided evidence of the existence of a slippery slope stemming from small increases in misconduct (Gino and Bazerman 2009; Free and Murphy 2015; Suh et al. 2020). Prior research has not, however, demonstrated whether small indiscretions in a non-financial reporting setting can push financial executives or other decision makers down the slippery slope and cause them to engage in serious violations. Our study addresses this void, and we find that the slippery slope is not a simple mechanism where small indiscretions consistently lead to fraud. Instead, there appears to be a complex interaction between tone at the top and the slippery slope. Second, limited research has examined the effect of top management’s leadership on accounting managers’ willingness to engage in unethical accounting practices (e.g., Arel et al. 2012) or achieve short-term performance targets (D’Aquila 2001). Our study adds to this research by examining the effect of tone at the top on financial executives’ misreporting decisions. Third, a stream of archival studies has provided mixed evidence on the impact of management fixed effects (top executives’ individual influences) on corporate decisions (Bertrand and Schoar 2003), strategy and performance (Chatterjee and Hambrick 2007), and financial reporting quality (Bamber et al. 2010; DeJong and Ling 2010; Ge et al. 2011; Dyreng et al. 2010; Jiang et al. 2010). This paper also sheds light on the specific characteristics of top executives, in particular the CFO’s attitude toward employees and earnings (i.e., the CFO’s tone), that can drive subordinate financial executives to engage in misreporting conduct. Finally, we demonstrate a gap between financial executive behavior and auditor expectations. There appear to be numerous opportunities to improve governance through additional auditor training.

Our research is subject to several limitations. The minor violation (e.g., giving away promotional mugs and shirts) represented a single violation. It is possible that if participants were allowed to commit many small violations, the slippery slope would be more likely to activate, and that committing many small and seemingly harmless violations could be more likely to trigger greater willingness to engage in more serious financial misreporting. In addition, different manipulations of the minor violation could alter willingness to engage in more serious misreporting. Additional research could address the potential effects of changes in the severity and number of minor violations on triggering the slippery slope. Further, like many experimental studies where internal validity is essential, our results are limited by the simplicity of the case materials. The case was brief and pertained to an accounting estimate. Greater details or different decision contexts could cause controllers to make different misreporting decisions. Finally, our study focuses on the effects of management tone and the slippery slope on decisions that affect the organization and its leadership and that have pro-organizational components. It is possible that decisions that largely involve one’s personal monetary incentives could respond differently to tone and the slippery slope.

Despite these limitations, our findings challenge current thinking about the effects of tone at the top and the slippery slope on misreporting behavior and suggest that some of the greatest risks may currently go undetected by auditors. Slippery slope effects also were not consistent with many assumptions about minor indiscretions leading to more serious fraud. CFO tone completely changed the nature of slippery slope effects. Overall, the results are important because they reveal that a negative tone set by top management may not always be the primary threat to integrity, which is currently a key assumption in audit practice and much of the accounting literature.

Notes

We employ a direct questioning approach for the minor rule violation because it is minor and harmless to investors, and it does not violate controllers’ professional standards. In addition, in order to allow for psychological numbing to occur, we needed participants to make a personal decision about the marketing items.

Our ANCOVA model used to test hypotheses includes a covariate that captures participants’ beliefs about the willingness of others to engage in misreporting similar to the misreporting in the experimental case. This covariate controls for dispositional beliefs about the willingness of others to misreport. Results of hypothesis testing remain the same if this covariate is removed from the model.

To verify that results are similar for only the practicing controller subset of participants, we perform the same ANCOVA analyses using only the practicing Dutch controllers. We again find a significant interaction (F = 6.23, p = 0.018), and the same pattern of results. Results indicate that practicing controllers and the executive MBA proxies for practicing controllers make very similar decisions in our experimental scenario.

It is also plausible that these results are driven, at least in part, by dispositions. Participants who choose to slip and violate a minor rule may hold beliefs that rules are relatively unimportant.

Preliminary tests revealed no significant effects of tone or the slippery slope on perceptions of the appropriateness of the warranty estimate (p = 0.71 and 0.55). These results are not tabulated.

References

Abernethy, M. A., & Brownell, P. (1997). Management control systems in research and development organizations: The role of accounting, behavior and personnel controls. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 22(3/4), 233–248.

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). (2002). Consideration of fraud in a financial statement audit. Statement on Auditing Standards No. 99. New York, NY: AICPA.

Amernic, J., Craig, R., & Tourish, D. (2010). Measuring and assessing tone at the Top Using Annual Report CEO Letters. Edinburgh: The Institute of Chartered Accountants of Scotland.

Anand, V., Dacin, M., & Murphy, P. (2015). The continued need for diversity in fraud research. Journal of Business Ethics, 131, 751–755.

Anderson, J., Kadous, C., & Koonce, L. (2004). The role of incentives to manage earnings and quantification in auditors’ evaluations of management-provided information. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 23(1), 11–27.

Arel, B., Beaudoin, C., & Cianci, A. (2012). The impact of ethical leadership, the internal audit function, and morality intensity on a financial reporting decision. Journal of Business Ethics, 109, 351–366.

Arens, A., Elder, R., Beasley, M., & Hogan, C. (2017). Auditing and Assurance Services. Michigan: Pearson.

Ashforth, B., & Anand, V. (2003). The normalization of corruption in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 25, 1–52.

Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE). (2006). Tone at the top: How management can prevent fraud in the workplace. Retrieved from https://www.acfe.com/uploadedFiles/ACFE_Website/Content/documents/tone-at-the-top-research.pdf.

Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE). (2018). Report to the nations: 2018 Global study on occupational fraud and abuse. Austin: Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, Inc.

Babcock, L., & Loewenstein, G. (1997). Explaining bargaining impasse: The role of self-serving biases. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 11, 109–126.

Bamber, L., Jiang, J., & Wang, Y. (2010). What’s my style? The influence of top managers on voluntary corporate financial disclosure. The Accounting Review, 85(4), 1131–1162.

Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(3), 193–209.

Barboza, D. (2002). Enron’s Many strands: Fallen star; from Enron fast track to total derailment. New York: New York Times.

Barrick, M., Parks, L., & Mount, M. (2005). Self-monitoring as a moderator of the relationships between personality traits and performance. Personnel Psychology, 58, 745–767.

Beasley, M., Carcello, J., Hermanson, D., & Neal, T. (2010). Fraudulent financial reporting 1998–2007: An analysis of US public companies. New York: Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO).

Bell, R. L. (2007). The manger’s role in financial reporting: A risk consultant’s perspective. Business Communication Quarterly, 70(2), 222–226.

Bertrand, M., & Schoar, A. (2003). Managing with style: The effect of managers on firm policies. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(4), 1169–1208.

Bierstaker, J., Downey, D., Rose, J., & Thibodeau, J. (2017). Effects of stories and checklist decision aids on knowledge structure development and auditor judgment. Journal of Information Systems, 32(2), 1–24.

Brown, B. (2014). Advantageous comparison and rationalization of earnings management. Journal of Accounting Research, 52(4), 849–876.

Brown, T., Rennekamp, K., Seybert, N., & Zhu, W. (2014). Who stands at the top and bottom of the slippery slope? Working paper, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Cornell University, University of Maryland at College Park, and Hong Kong University.

Burns, J., & Baldvinsdottir, G. (2007). The changing role of management accountants. In T. Hopper, D. Northcoot, & R. Scapens (Eds.), Issues in management accounting (pp. 117–132). Harlow: Financial Times Prentice Hall.

Center for Audit Quality (CAQ). (2010). Deterring and detecting financial reporting fraud: A platform for action. Washington, DC: Center for Audit Quality.

Chatterjee, A., & Hambrick, D. (2007). It’s all about me: Narcissistic chief executive officers and their effects on company strategy and performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(3), 351–386.