Abstract

Deception is common in the marketplace where individuals pursue self-interests from their perspectives. Extant research suggests that perspective-taking, a cognitive process of putting oneself in other’s situation, increases consumers’ ethical tolerance for marketers’ deceptive behaviors. By contrast, the current research demonstrates that consumers (as observers) who take the dishonest marketers’ perspective (vs. not) become less tolerant of deception when consumers’ moral self-awareness is high. This effect is driven by moral self-other differentiation as consumers contemplate deception from the marketers’ perspective: high awareness of the “moral self” motivates consumers to distance themselves from the “immoral other.” The findings shed new light on how self-morality can vicariously shape social consideration in ethical judgments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Deception is ubiquitous during marketplace interactions among consumers and marketersFootnote 1 (Boush et al. 2009). Extant research focuses on defining and characterizing deception in specific functional areas such as advertising and personal selling (e.g., Gardner 1975; Hyman 1990; Xie et al. 2015a, b), and how consumers respond to marketers’ deceptive persuasion attempts (e.g., Craig et al. 2012; Darke and Ritchie 2007). From an ethical standpoint, anecdotal evidence suggests that consumers’ tolerance toward marketers’ acts of deception can be influenced by the social perspective they take (Boush et al. 2009; Ekman 2001). Previous studies have explored various aspects of the consumer’s or the deceiver’s perspective, respectively (e.g., Argo et al. 2006; Cowley and Anthony 2019; Mazar et al. 2008; Gino and Bazerman 2009; Rotman et al. 2018). However, little is known about whether taking the deceiver’s perspective influences consumer’s ethical tolerance toward marketplace deception. Imagine the following: you sit down with friends, John and Katy, and tell them about your recent experience with a car salesperson. You explain to them that you felt bothered, as the salesperson lied about the invoice price of a car you were interested in buying. Katy says: “Why wouldn’t he just be honest? It doesn’t make sense.” John has an opposite view, “I see where he was coming from. If I was in his shoes, I would probably have done the same thing.” “It’s unethical; I would have been honest if I were him,” Katy adds. This conversation exemplifies an intriguing, yet under-researched question: when it comes to judging marketplace deception, why does perspective-taking increase ethical tolerance for some people, but decrease it for others? This research aims to understand better when and why such different ethical judgments occur at the individual level.

Perspective-taking is “the process of imagining the world from another’s vantage point or imagining oneself in another’s shoes” (Galinsky et al. 2005, p. 110), whereas ethical tolerance refers to the extent to which one considers ethically questionable behaviors acceptable (Ashkanasy et al. 2000; Nenkov et al. 2019; Weeks et al. 2005). It appears obvious that consumers who take a deceiver’s perspective (vs. not) will be more tolerant, as a wealth of literature has documented that perspective-taking often fosters the understanding of different viewpoints and moderates negative social judgments (for a review, see Ku et al. 2015). However, empirical evidence is scarce. In the literature, only two studies have reported correlational data on the effects of dispositional tendency to take others’ perspectives on one’s perceptions of others’ deceptive behaviors. Cohen (2010) finds that the perspective-taking, as a personality trait, is not significantly correlated with people’s approval level of using deceitful negotiation tactics. Further, Cojuharenco and Sguera (2015) examine perspective-taking as a personality trait to understand its effect on employees’ acceptability of lying to protect their company’s interest. The findings show that perspective-taking is negatively correlated with the acceptability of lying among participants who tended to do things quickly and in a hurry at work. In both studies, the research participants were not instructed explicitly to think as observers or actors, although the use of first- and second-person pronouns (e.g., “intentionally misrepresent information to your opponent in order to strengthen your negotiating arguments or position;” “at work, I tend to do things fast”) in the questionnaires may have primed them toward thinking as actors (i.e., negotiators or employees). These findings suggest that perspective-taking does not necessarily increase ethical tolerance for deception, but it remains unclear as to whether any causal effect of perspective-taking exists, especially beyond the actor’s standpoint.

The present research explicitly explores consumer observers’ judgments of marketplace deception, examining the causal effect of perspective-taking on their ethical tolerance and the moderating role of their moral self-awareness. Moral self-awareness is “a mindset informed by reflection on moral identity, namely what one’s actions say about oneself given (a) the negative impact on others or society that one’s action may effect, and (b) what one contributes to others and/or society by taking a given action” (Friedland and Cole 2019, p. 196). In theory, people can think of themselves as moral and/or immoral. In line with extant literature, this research focuses on one’s awareness of the moral self, rather than the immoral self, that evokes deontological moral principles (e.g., “it is wrong to act dishonestly”) and/or virtue moral motivation (e.g., “acting honestly is personally fulfilling”) toward self-actualization (Friedland et al. 2020). For instance, previous work shows that people tend to uphold a sense of moral self in justifying their dishonest behaviors (e.g., Mazar et al. 2008; Mulder and Aquino 2013). In particular, Mazar et al. (2008) find that people rationalize their inconsequential dishonest behaviors in order to maintain positive self-concepts of being honest, suggesting that moral self-awareness plays an important role in shaping ethical judgments of one’s own deceptive behaviors. It awaits to be examined whether and how moral self-awareness influences ethical tolerance of marketers’ deceptive behaviors, when people have an opportunity to deliberate about the situation from the marketer’s perspective. As people switch their vantage points by deliberating the marketer’s situation vicariously, it is plausible that a different set of social norms can be evoked (Gino and Galinsky 2012). The current research examines whether and how moral self-awareness can shift consumer observers’ ethical judgments in line with their own moral compasses in perspective-taking.

In two experiments and one correlational study, this research demonstrates that when consumers observe a marketer’s act of deception, taking the marketer’s perspective decreases ethical tolerance, specifically when consumers’ moral self-awareness is high. In other words, while observing a marketer’s deceptive behavior, consumers are less ethically tolerant when taking the marketer’s perspective (vs. not) if they are particularly aware of their moral self. Further, the findings pinpoint an essential aspect of the underlying mechanism, “moral self-other differentiation,” a psychological process defined as the extent to which people differentiate themselves from others as a result of perceived conflicting moral identities (Aquino and Reed II 2002; Berger and Heath 2008). When moral self-awareness is high, consumers who take the marketer’s perspective (vs. not) are motivated to differentiate their “moral self” from the “immoral other” to a greater extent. Thus, consumers tend to vicariously distance themselves from the marketer by weighing more on moral ramifications instead of material gains in the marketer’s situation. The greater extent of moral self-other differentiation results in harsher ethical judgments, decreasing consumers’ ethical tolerance of the marketer’s act of deception.

These findings contribute to three streams of research: ethical judgment, marketplace deception, and perspective-taking. Foremost, the current research proposes and demonstrates the moderating role of moral self-awareness in shaping one’s ethical judgment from beyond his or her own perspective. It provides the first direct empirical evidence concerning the psychological effect of a novel construct, moral self-awareness (Friedland and Cole 2019), in the business ethics literature. This work extends previous research on the effects of self-oriented motivations on consumers’ ethical consumption behaviors (e.g., Hwang and Kim 2018). Interestingly, when considering ethical behavior from the marketer’s vantage point, consumers tend to rely on their own moral compass as elicited by moral self-priming (Study 1 and 3) or behavioral projection (Study 2). While a vast majority of empirical studies on ethical judgment are derived from one particular type of perspective (for the most recent reviews, see Craft 2013; Lehnert et al. 2015; Sparks and Pan 2010), this research examines ethical tolerance when consumers take marketers’ perspective that can be diagonally different from their own. Specifically, previous studies (e.g., Gino et al. 2009; Gino and Galinsky 2012) demonstrate one’s own selfish behavior can be influenced by feeling connected with selfish others when people take others’ perspectives. By contrast, the current work shows that one’s sense of self-morality can vicariously shape the effect of the social component of morality. That is, one’s own moral compass can indeed resist social connectedness, and “self-correct” when people feel motivated to differentiate themselves morally from an unethical other. This occurs when one’s moral self-awareness is indeed moral and particularly high (vs. low) at the moment of taking the other’s perspective.

Second, this research expands the current understandings of how consumers respond to marketplace deception. Rather than defensively rejecting a marketer’s deceptive behaviors as prior studies have documented (e.g., Craig et al. 2012; Darke and Ritchie 2007; Xie et al. 2015a, b), consumers are capable of contemplating situational or social norms from different viewpoints when taking the marketer’s perspective. Whether consumers are tolerant of such deceptive behaviors, however, depends largely upon the extent to which their moral self-awareness psychologically separates themselves from the marketer. This finding can also have broader implications for understanding moral judgments of deception in other contexts, such as personal interactions, workplace negotiations, and public affairs.

Third, this research reveals a counter-intuitive effect of perspective-taking on ethical judgments. Prior research suggests that perspective-taking reduces the psychological distance between people with conflicting interests or viewpoints (Batson et al. 1997; Davis et al. 1996; Galinsky et al. 2005; Gino and Galinsky 2012; Todd and Burgmer 2013). By contrast, this work demonstrates when and why one’s sense of self-morality can separate people psychologically, and thus reverse the otherwise positive perspective-taking effect on ethical tolerance. The “moral self-other differentiation” highlighted in this research presents a sharp contrast to the well-documented “self-other overlap,” adding a new perspective on the underlying mechanisms of perspective-taking, specifically when it comes to ethical tolerance of marketplace deception.

Theoretical Development

Perspectives on Marketplace Deception

Marketplace deception is at the core of academic research on marketplace morality, marketing public policy, and consumer protection (Boush et al. 2009; Campbell and Winterich 2018). From a communication standpoint, deception is “the act of knowingly transmitting a message intended to lead a receiver to false belief or conclusion” (Burgoon et al. 1999, p. 669). For instance, it is deceptive when people provide online product reviews, stating that they had purchased an item that they had never purchased (Anderson and Simester 2014). The marketplace is a social context where ethical or moral judgments are particularly relevant to consumers. Marketplace interactions are featured by one’s pursuit of self-interests from exchanges, transactions, or relationships (Campbell and Winterich 2018). Deception in the marketplace is often perceived intentional (Boush et al. 2009), compared to sometimes unintentional deception in other contexts (e.g., social gatherings of friends or strangers). For the deceivers in the marketplace, deception is instrumental in gaining material or psychological benefits (Argo et al. 2006; Shalvi 2012). Meanwhile, the marketplace demands certain moral values such as abiding social contracts and serving greater goods (Grayson 2014), which can demotivate deceptive behaviors. Thus, conflicts or tradeoffs between self-interest and self-morality often underlie the different perspectives on the perceived ethicality of marketplace deception (Bhattacharjee et al. 2013; Campbell and Winterich 2018; Kirmani et al. 2017).

The consumer research literature on marketplace deception entails two main perspectives: (1) the “deceiver’s” perspective—how and why consumers themselves act deceptively (e.g., Anthony and Cowley 2012; Argo and Shiv 2012; Cowley and Anthony 2019; Rotman et al. 2018; Sengupta et al. 2002), and (2) the “target’s” perspective—how and why consumers respond to deceivers who attempt to deceive them or other consumers (e.g., Craig et al. 2012; Darke and Ritchie 2007; Johar 1995). Concerning the “deceiver’s perspective,” consumers can act dishonestly, while delicately balancing considerations of self-interest and self-morality. For instance, Mazar et al. (2008) demonstrate that consumers can lie without deeming themselves as being dishonest, as long as they consider the lies trivial. The authors find that this effect is driven by “self-concept maintenance,” a theory suggesting that consumers rationalize or justify their acts of dishonesty (i.e., lying or cheating) in order to maintain a moral self-concept. Similarly, Rotman et al. (2018) find that consumers can lie to demand compensations from harmful companies, while they do not feel immoral.

When it comes to consumers as the “target,” extant studies suggest that consumers tend to resent deception and react defensively. Negative repercussions of perceived deception are extensive: consumers are inclined to terminate processing marketing messages involving explicit deception (Craig et al. 2012); they are more likely to hold strongly negative attitudes toward deceptive advertisements (Xie et al. 2015a, b); and they are less likely to consider purchasing from deceptive agents (Barone and Miniard 1999). Elevated distrust underlying such unequivocally negative responses toward a dishonest marketer can spill over to other innocent marketers that do not engage in deception, similar to a negative “halo effect” (Darke and Ritchie 2007).

Despite the rich findings around the consequences of deception, this literature has yet examined how consumers would judge deceptive behaviors ethically when the deceiver’s and the target’s perspectives collide. More specifically, when consumers take the deceiver’s perspective, do they realize that they themselves might also deceive a target in pursuit of self-interest? Or, do they disassociate themselves from the deceiver by adhering to moral values of being honest? This inquiry expands the current understanding of how consumers cope with conflicts between self-interest and self-morality in the marketplace from beyond the target’s or the deceiver’s perspective alone. Based on previous perspective-taking research, the next section discusses the plausible effects regarding what might occur when consumer observers take the deceiver’s perspective.

Effects of Perspective-Taking

Perspective-taking is an ability as well as a process. A classic definition of perspective-taking is “the ability to put oneself in the place of others and recognize that other individuals may have points of view different from one’s own” (Johnson 1975, p. 241). Over the past four decades, the definition has evolved to be more process-focused, referring to “the active cognitive process of imagining the world from another’s vantage point or imagining oneself in another’s shoes to understand their visual viewpoint, thoughts, motivations, intentions, and/or emotions” (Ku et al. 2015, pp. 94–95). Extant research has documented multiple antecedents and consequences of perspective-taking in a variety of contexts (see Ku et al. 2015 for a review). Individuals’ tendency to think actively from others’ perspectives is contingent upon both personal and situational factors, such as perceiver’s developmental stage (Gjerde et al. 1986), perceiver-target dependency (Wu and Keysar 2007), and perceiver’s power status (Galinsky et al. 2006). The consequences are predominantly positive, such as eliciting empathy toward others (Batson et al. 1997), enhancing self-other relationships (Arriaga and Rusbult 1998), and attenuating stereotypes toward others (Laurent and Myers 2011). In the context of marketplace, Mazzocco et al. (2012) find that perspective-taking can promote consumers to identify temporarily with an out-group, motivating conspicuous consumption.

Regarding the mechanisms underlying the perspective-taking effects, the notion of “self-other overlap” and its variants have emerged as a primary cognitive account (Batson et al. 1997; Galinsky et al. 2005; Ku et al. 2015). That is, taking another’s perspective prompts people to associate a greater percentage of self-descriptive traits with others, as if oneself and the other share more similar beliefs, viewpoints, and even identities (Davis et al. 1996). For instance, Galinsky et al. (2008) find that perspective-takers rate both positive and negative stereotypic traits of others as being more self-descriptive. Due to incorporating these traits of others in the self, perspective-takers tend to behave in ways that are consistent with stereotypes toward others. Variants of “self-other overlap” include concepts such as “merged identities" (Goldstein and Cialdini 2007), “psychological closeness” (Gino and Galinsky 2012), and “psychological connectedness” (Todd and Burgmer 2013). Despite some nuances, these concepts converge at the point that perspective-takers are inclined to focus on self-other similarities when they deliberate about situations from others’ vantage points.

Despite the vast amount of research around the self-other overlap, a handful of studies suggest that people do not necessarily “overlap” with others in perspective-taking (e.g., Lucas et al. 2016; Skorinko and Sinclair 2013; Tarrant et al. 2012). Lucas et al. (2016) show that perspective-taking can reinforce negative judgments of others when people access stereotypes more readily and refrain from associating the self with others. Similarly, Skorinko and Sinclair (2013) demonstrate that when an out-group target carries salient (vs. ambiguous) stereotypical traits, out-group biases increase among those observers who engage in perspective-taking. Tarrant et al. (2012) also find that the perspective-takers who identify highly (vs. not) with their own in-group identities use a greater number of negative traits to describe disadvantaged others from an out-group. These findings suggest that perspective-taking can result in “self-other differentiation” rather than “self-other overlap,” driven by perspective-takers’ self-concepts. Extending this stream of research, the current work examines specifically how high or low awareness of one’s moral self can shape perspective-takers’ ethical tolerance for marketplace deception, as discussed next.

Role of Moral Self-awareness

The moral self is a critical component of one’s self-concept regarding how moral people view themselves and relate to others (Aquino and Reed II 2002; Bartels et al. 2014; Darley and Shultz 1990). Prior studies show that people tend to favor those who share the same moral identities with themselves in evaluating others’ ideas or behaviors (e.g., Liu et al. 2019; Reed II 2004; Sachdeva et al. 2009; Winterich et al. 2009). When it comes to understanding how consumers judge marketplace deception, moral self-awareness becomes a crucial factor to consider, as the previous work on self-awareness in general suggests that “inconsistencies become much more aversive when people direct their attention to the self” (Goukens et al. 2009, p. 682). Vincent et al. (2013) find that the positive affect facilitates moral disengagement and promotes dishonest acts; but when one’s self-awareness of morality becomes high, the facilitative effect of positive affect on dishonest acts is mitigated. In this regard, moral self-awareness is a situational mental state reflecting the accessibility of one’s moral self-identity, which informs people whether one’s actions are morally right or wrong, and whether others are relatable or not (Friedland and Cole 2019). Once accessible and diagnostic to a situation, the moral self-identity can function as an “egocentric anchor” that guides one’s judgments of others (Bolton and Reed II 2004; Naylor et al. 2011). This anchor then influences the decision process by directing people to consider how morally similar or different others are to the self (Sachdeva et al. 2009).

In line with previous research on marketplace deception (e.g., Darke and Ritchie 2007; Xie et al. 2015a, b), the current work postulates that when observing acts of deception in the marketplace, consumers would, in general, consider deceptive behaviors unethical, inappropriate, unacceptable, or unfair, which indicates low ethical tolerance. When moral self-awareness is low, perspective-taking will increase consumers’ ethical tolerance due to “self-other overlap.” That is, when consumer observers take the perspective of the deceiver (vs. not), they tend to justify the dishonest behaviors to a greater extent, as they would consider the pursuit of self-interest in the deceiver’s position more acceptable and/or they would probably act similarly as the deceiver does (Gino and Galinsky 2012). Consumers are more likely to feel psychologically connected with the deceiver when taking the deceiver’s perspective. As a result, perspective-takers’ ethical tolerance of marketplace deception will increase.

Whereas when one’s moral self-awareness is high, the current work postulates that consumer observers will distance the “moral self” from the “immoral other” to a greater extent when taking the deceiver’s perspective (vs. not). This phenomenon occurs in that people are motivated to maintain or enhance a positive moral self-concept and can do so by comparing themselves to others in a given situation (Argo et al. 2006; Gino and Bazerman 2009; Mazar et al. 2008). Perspective-taking (vs. not) will elicit more deliberation concerning the moral wrongness of deception in a deceiver’s situation, which can outweigh one’s social consideration about self-interest from the deceiver’s vantage point. In particular, those perspective-takers who would project acting honestly when in the deceiver’s situation would tolerate deception to a much less extent to maintain or enhance their sense of moral self. Based on this reasoning and consistent with a more general “egocentric anchoring” mechanism in social judgments (Naylor et al. 2011), the hypothesis 1 (H1) posits that perspective-takers are less tolerant toward marketers’ deceptive acts when their moral self-awareness is high. Importantly, this hypothesis suggests that moral self-awareness does not simply attenuate the positive effect of perspective-taking on ethical tolerance. Instead, moral self-awareness will reverse the perspective-taking effect toward making harsher ethical judgments on marketplace deception. In short, H1 posits that moral self-awareness moderates the perspective-taking effect on ethical tolerance, as the following:

H1

When consumer observers’ moral self-awareness is high (vs. low), perspective-taking will decrease (vs. increase) ethical tolerance for marketplace deception.

Regarding the underlying mechanism, the hypothesis 2 (H2) posits that the conditional effect of perspective-taking on ethical tolerance will be driven by “moral self-other differentiation.” In the context of taking a dishonest marketer’s perspective, high moral self-awareness will motivate consumer observers to distance themselves from the marketer to a greater extent due to a more considerable contrast between the “moral self” and the “immoral other.” Using an analogy, they would project themselves standing on the higher moral ground to maintain or enhance their own sense of being moral. When consumer observers’ moral self-awareness is low, taking the marketer’s perspective would make them feel more connected psychologically to the marketer from his or her viewpoint, as reflected by a less degree of “moral self-other differentiation.” By contrast, when consumer observers’ moral self-awareness is high, taking the marketer’s perspective would vicariously evoke a sharper contrast between the marketer’s immorality and one’s sense of self-morality. The moral self-awareness, in effect, enacts consumers’ thinking or feeling about their identities as being a moral person. Previous research suggests that when such identities become salient, people become more sensitive to situational cues that are consistent or inconsistent with their identities (e.g., Coleman and Williams 2015; Oyserman 2019; Reed II 2004). People generally prefer to act in ways that they consider consistent with such identities (LeBoeuf et al. 2010; Oyserman 2019) and avoid acting in ways that are inconsistent with such identities (e.g., Berger and Heath 2008; Rank-Christman et al. 2017; Ward and Broniarczyk 2011). In line with this stream of research, the current work postulates when one’s moral self-awareness is high, perspective-taking (vs. not) would make the inconsistency between the “moral self” and the “immoral other” more pronounced, because of the projected conflicting moral identities. To resolve the inconsistency, perspective-takers with high moral self-awareness reconfirm or reinforce their moral identities with less ethical tolerance for deception. In other words, when perspective-takers with high awareness of the moral self deliberate about a marketer’s deceptive act, they tend to think it is wrong for themselves to deceive, and/or it is personally fulfilling to be honest, in the marketer’s situation. As a result, they will be more likely to project themselves as being different from the dishonest marketer, as reflected by a greater degree of moral self-other differentiation, which in turn decreases ethical tolerance for deception. In short, H2 posits a moderated mediation mechanism explaining why the hypothesized moderated effect of perspective-taking occurs in the context of marketplace deception, as the following:

H2

The moderated effect of perspective-taking on ethical tolerance is mediated by moral self-other differentiation.

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual model that H1 and H2 present.

Overview of Empirical Studies

Three studies examine the conditional effects of perspective-taking on consumer observers’ ethical tolerance for marketplace deception when their moral self-awareness is high (vs. low). In Study 1, as observers, participants evaluated a dishonest salesperson in a personal selling scenario after they took the salesperson’s perspective (vs. not). High moral self-awareness was elicited by priming participants to elaborate on moral values of being honest relating to their personal experiences. Moral self-other differentiation was measured and tested as a mediator of the hypothesized interaction between perspective-taking and moral self-awareness. In other words, moral self-other differentiation was operationalized as perceived “psychological distance” (Gino and Galinsky 2012; Liberman and Trope 2014), as this measure captures how socially different participants would feel toward the salesperson as a result of moral concerns in this context. In Study 2, participants not only took the dishonest salesperson’s perspective, but also indicated what they would do if they were in the salesperson’s situation. This unique design elicited perspective-takers’ moral self-awareness distinctively from Study 1 and specifically measured the extent to which the participant would act honestly if they were in the salesperson’s situation. Study 3 presented a different context using a dishonest online seller. Participants again were instructed to take the seller’s perspective (vs. not) experimentally. In this study, moral self-awareness was manipulated differently from that in Study 1, by priming participants to elaborate on their personal experiences of acting honestly.

Study 1: “The Moral Self” vs. “The Immoral Other”

The purpose of Study 1 was to test the moderated effect of perspective-taking on ethical tolerance when moral self-awareness is high (vs. low). Study 1 also examined the underlying mechanism driven by moral self-other differentiation.

Sample, Design, and Procedure

One hundred and sixty participants (55 females, Mage = 36.2) from Amazon Mechanical Turk (M-Turk) participated in an online experiment in exchange for a small monetary sum.Footnote 2 The experiment employed a 2 (perspective-taking vs. control) × 2 (high vs. low moral self-awareness) randomized between-subjects design.

First, participants completed a moral self-awareness priming (vs. neutral) task by typing three morality-laden (vs. morality-neutral) sentences in the given space of the online questionnaire: “no legacy is so rich as honesty,” “honesty is the first chapter in the book of wisdom,” and “honesty is the best policy” (vs. “there’s no place like home,” “soccer is the first sport that many American children play,” and “summer is the best time”).Footnote 3 All participants were instructed to think about what these sentences meant to them. Then, they all wrote a short story about themselves reflecting on these sentences (inspired by Sachdeva et al. 2009). The instructions were: “In the space below, please write a short story (less than 100 words) about yourself reflecting on ALL of these sentences. Your story can be fictional. Please visualize the story and how it relates to your characteristics.”

The moral self-awareness priming (vs. neutral) task described above was tested in an independent pretest on its efficacy in increasing one’s awareness of moral self. One hundred and seventy-two participants from M-Turk (71 females, Mage = 35.7) participated in an online experiment in exchange for a small monetary sum. They were randomly assigned to one of two conditions (i.e., high vs. low moral self-awareness). After completing the priming (vs. neutral) task, participants indicated their moral self-awareness on the following three-item scale (adapted from Vincent et al. 2013): “At this moment, I am aware of my own morals;” “I am reflecting on my own moral self;” and “I am attentive to how moral I am as a person” (1 = completely disagree, 7 = completely agree). The scale was unidimensional and highly reliable (α = 0.90). Results from a one-way ANOVA suggest that the priming task was highly effective in increasing moral self-awareness (Mpriming = 6.06, SD = 1.03) relative to the neutral task (Mneutral = 5.22, SD = 1.44), F (1,170) = 18.78, p < 0.001.

In the main study, participants then read a vignette describing a situation about a car salesperson (see Web Appendix W1). In the scenario, the salesperson tells a customer that the margin of a chosen car is $500. The customer finds out that the true margin is $800, and that the salesperson lied by $300. Participants were instructed to imagine watching the situation as observers and to take the salesperson’s perspective: “While reading the scenario as an observer, please take the perspective of the salesperson. Imagine, if you will, walking in the salesperson’s shoes and thinking as the salesperson would while reading the scenario” (adapted from Galinsky et al. 2008). Participants in the control condition read the vignette without the perspective-taking instruction.

After reading the vignette, participants in the perspective-taking condition were reminded to take the salesperson’s perspective. Those participants in the control condition were not given this reminder. All participants then completed a thought-listing task by typing out their thoughts about the salesperson. The combination of the perspective-taking instruction (vs. control), the reminder (vs. control), and the thought-listing task manipulated the degree to which participants took the salesperson’s perspective.

Participants then evaluated the salesperson’s dishonest behavior on a four-item scale: “ethical,” “acceptable,” “appropriate,” “fair” (1 = definitely not, 7 = definitely yes). These items reflected key dimensions of ethical tolerance as documented in the previous studies, including “perceived fairness” (Lee et al. 2018), “acceptability” (Gino and Bazerman 2009), “perceived ethicality” (Ashkanasy et al. 2000), and “appropriateness” (Cohen 2010). The scale was unidimensional and highly reliable (α = 0.96). The average rating was calculated to create a measure of ethical tolerance. Participants also indicated the degree of “moral self-other differentiation.” The hypothesized mediator was measured by the perceived psychological distance between oneself and the salesperson on a 3-item scale: “similar,” “related,” and “psychologically close” (1 = not at all, 7 = to a great extent; adapted from Gino and Galinsky 2012). This scale was unidimensional and highly reliable (α = 0.95). In addition, participants reported the extent to which they took the salesperson’s perspective (1 = definitely not, 7 = definitely yes). Basic demographics (e.g., age, gender) were also collected.

Results

As a manipulation check, results from a one-way ANOVA show that the participants in the perspective-taking condition (M = 6.14, SD = 1.17) took the salesperson’s perspective to a significantly greater extent than those in the control condition (M = 4.43, SD = 1.83), F (1,137) = 43.33, p < 0.001.

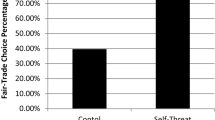

A 2 × 2 between-subjects ANOVA on ethical tolerance reveals a marginally significant main effect for moral self-awareness, F (1,135) = 3.43, p = 0.07. The main effect of perspective-taking was not significant, F (1,135) = 0.74, p = 0.39. As expected, the interaction between the two was significant, F (1,135) = 14.00, p < 0.001. Further contrasts show that in the low moral self-awareness condition, perspective-taking increased ethical tolerance (Mperspective-taking = 4.13, SD = 1.82 vs. Mcontrol = 2.86, SD = 1.55), F (1,70) = 9.77, p < 0.01. In the high moral self-awareness condition, perspective-taking decreased ethical tolerance (Mperspective-taking = 2.59, SD = 1.23 vs. Mcontrol = 3.38, SD = 1.65), F (1,65) = − 4.63, p = 0.04. H1 was supported. Figure 2 illustrates the interaction.

A moderated mediation model was tested to predict ethical tolerance following Hayes’ PROCESS procedure (2018, version 3.4; Model 7) with 5,000 bootstrap samples. Perspective-taking (binary: perspective-taking = 1 and control = 0, manipulated) was tested as the predictor, and moral self-other differentiation (continuous; measured) was tested as the mediator. Moral self-awareness (binary: moral self-awareness high = 1 and low = 0; manipulated) was tested as a moderator of the effect of perspective-taking on moral self-other differentiation, which in turn affects ethical tolerance.

The results show that the interaction between perspective-taking and moral self-awareness on moral self-other differentiation was significant (β = − 2.29, se = 0.55, p < 0.001). Moral self-other differentiation was also a significant predictor of ethical tolerance (β = 0.59, se = 0.07, p < 0.001). As expected, the hypothesized moderated mediation effect was supported (95% LLCI = − 2.09 to ULCI = − 0.71, excluding zero). Specifically, in the low moral self-awareness condition, perspective-taking was a significant predictor of moral self-other differentiation, t (70) = − 4.05, p < 0.001 (95% LLCI = − 2.31 to ULCC = − 0.80, excluding zero). The mediation pathway from perspective-taking to ethical tolerance via moral self-other differentiation was significant (95% LLCI = − 1.43 to ULCI = − 0.49, excluding zero). Whereas in the high moral self-awareness condition, perspective-taking was a marginally significant predictor of moral self-other differentiation in an opposite direction, t (65) = 1.84, p = 0.07 (95% LLCI = − 0.06 to ULCC = 1.52, including zero). The mediation pathway from perspective-taking to ethical tolerance via moral self-other differentiation was not significant (95% LLCI = − 0.01 to ULCI = 0.91, including zero).

Discussion

The findings from Study 1 provide initial evidence supporting H1, showing that when observers’ moral self-awareness is high (vs. low), perspective-taking decreases ethical tolerance of marketplace deception. In the context of observing a dishonest car salesperson, the perspective-taking effect was conditional, depending upon one’s moral self-awareness. These findings also support H2, showing that the conditional effect is partially due to a greater extent of moral self-other differentiation, as reflected by the greater psychological distance between the self and a dishonest salesperson. When moral self-awareness is high, perspective-takers differentiate themselves further from the dishonest salesperson to uphold a sense of moral self. It is worthy to note that in this study, perspective-taking and moral self-awareness were manipulated experimentally. As suggested by the experimental research paradigm, the random assignment of research participants to each of the experimental conditions ensured that the potential effect of any individual differences (i.e., perspective-taking trait and moral self-awareness) was controlled (Calder et al. 1981; Campbell and Stanley 1966; Cook and Campbell 1975; Gilovich et al. 2006; Howell 2002). To ensure the findings from Study 1 were robust, Study 2 employed a unique design to replicate the perspective-taking effect when moral self-awareness was high or low. Study 2 also measured and tested the dispositional difference in perspective-taking as a personality trait variable.

Study 2: Vicarious (Dis)Honesty

The purpose of Study 2 was to test the effect of moral self-awareness in perspective-taking with a more naturalistic approach beyond experimental manipulation. In the same context of observing a dishonest salesperson as that in Study 1, participants took the salesperson’s perspective and indicated how they themselves would act in the salesperson’s situation. The self-reported vicarious honesty (or dishonesty) indicated the extent of moral self-awareness conceptually so that perspective-takers who projected themselves acting honestly (vs. not) would have evoked higher moral self-awareness.

Sample, Design, and Procedure

Two hundred M-Turk participants (88 females, Mage = 35.7) participated in an online study in exchange for a small monetary sum. Participants read the same vignette from Study 1, which described a personal selling situation about a car salesperson. In the scenario, the salesperson tells a customer that the margin of a chosen car is $500. The customer finds out that the true margin is $800 and that the salesperson lied by $300. Participants were instructed to imagine watching the situation as observers and take the salesperson’s perspective. After reading the vignette, participants were reminded to take the salesperson’s perspective. Importantly, participants then were asked to indicate a specific margin that they would have told the customer if participants were in the salesperson’s position: “what would you tell Jamie about the margin in the salesperson's position (in $ amount), considering that the salesperson says the margin is $500 when in fact it is $800?” This “vicarious (dis)honesty” task elicited moral self-awareness by having participants contemplate the extent to which they would have acted honestly in the salesperson’s situation. The task efficacy was tested in an independent pretest to ensure that moral self-awareness was higher for those participants who indicated they would act honestly, compared to those who would act dishonestly.

One hundred and twenty participants from M-Turk (46 females, Mage = 34.5) took part in an online pretest in exchange for a small monetary sum. They followed the exact task procedure as in the main study. After reading the scenario and reporting how honest they would act in the salesperson’s situation, participants completed a moral self-awareness scale using the same three items from Study 1. Again, the scale was both unidimensional and reliable (α = 0.80). One-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference in moral self-awareness for those participants who would act honestly (n = 39) compared to those who would act dishonestly (n = 81). Moral self-awareness was significantly higher among “honest perspective-takers” (Mhonest = 5.96, SD = 1.29) than “dishonest perspective-takers” (Mdishonest = 5.50, SD = 1.04), F (1,118) = 4.26, p = 0.04.

In the main study, participants reported their ethical tolerance of salesperson’s dishonest behavior on the same four-item scale as that in Study 1 (unidimensional; α = 0.95). Participants also reported the extent to which they had taken the salesperson’s perspective (1 = definitely not, 7 = definitely yes), indicating the degree of perspective-taking in the situation (i.e., “perspective-taking”). Further, given that previous research shows that perspective-taking, as a personality trait, may influence ethical judgments of deception (Cohen 2010; Cojuharenco and Sguera 2015), participants completed the perspective-taking trait scale assessing their tendencies to spontaneously adopt the point of view of others (i.e., “perspective-taking trait,” Davis 1983) toward the end of the study. This scale included six itemsFootnote 4 including “I try to look at everybody's side of a disagreement before I make a decision;” and “when I'm upset at someone, I usually try to ‘put myself in his shoes’ for a while” (1 = does not describe me at all, 7 = describes me very well). The scale was unidimensional and highly reliable (α = 0.84). The average ratings were used to calculate a perspective-taking trait measure, which accounted for participants’ dispositional tendencies to engage in perspective-taking while following the perspective-taking instructions. Basic demographics (e.g., age, gender) were also collected.

Results

Regarding the margins that participants would tell the customer if they were in the salesperson’s position, all participants reported numbers no greater than $800. These numbers met the premise that a salesperson should not tell customers a margin higher than the actual one, suggesting that participants followed the instructions and projected reasonable acts in the salesperson’s situation. The degree of their projected act of (dis) honesty was calculated, subtracting the self-reported margin from the true margin $800. In effect, the less participants would have lied to the customer in the salesperson’s situation, the more projected honesty they could have demonstrated.

In total, eighty-four participants (42%) indicated they would have told the customer the true margin $800, suggesting that they would have acted honestly in the salesperson’s situation. The other one hundred and sixteen participants (58%) reported a value ranging from $300 to $800, suggesting that they would have been dishonest to some extent if they were in the salesperson’s situation. Accordingly, two linear regression tests were performed (see Web Appendix W2): the first examined how “perspective-taking” and the “perspective-taking trait” would impact ethical tolerance among those “honest perspective-takers”(i.e., high moral self-awareness), and the second examined how these two variables would impact ethical tolerance among those “dishonest perspective-takers”(i.e., low moral self-awareness), as illustrated next.

Those participants who indicated that they would tell the customer the true margin were identified as “honest perspective-takers” (n = 84). These “honest” participants were conceptually equivalent to those participants in the high moral self-awareness condition in Study 1, as the pretest results suggested. The first linear regression model (Model 1) was tested with “ethical tolerance” as the dependent measure, and “perspective-taking” and “perspective-taking trait” as the predictors for the “honest perspective-takers.” The standard coefficient test results show that perspective-taking was a significant predictor of ethical tolerance (β = − 0.22, p = 0.05). The more these “honest” participants would take the salesperson’s perspective, the less tolerant they were of the salesperson’s act of deception. The “perspective-taking trait” was not a significant predictor of ethical tolerance (β = − 0.09, p = 0.44). In contrast, those participants who would not tell the customer the true margin were identified as “dishonest perspective-takers” (n = 115). The second linear regression model (Model 2) was tested with “ethical tolerance” as the dependent measure, and “perspective-taking” and “perspective-taking trait” as the predictors for the “dishonest perspective-takers.” The standard coefficient test results show that perspective-taking (β = − 0.06, p = 0.54) and the “perspective-taking trait” (β = 0.10, p = 0.31) were not significant predictors of ethical tolerance.

Discussion

Study 2 provides further evidence that perspective-taking can reduce ethical tolerance of a salesperson’s deceptive act, specifically for those consumer observers who would have acted honestly if they were in the salesperson’s situation. Conceptually, the vicarious sense of acting honestly (vs. dishonestly) serves as a proxy of high (vs. low) awareness of moral self. The pretest results supported that when perspective-takers projected acting honestly (vs. dishonestly), their moral self-awareness was indeed significantly higher. Consistent with Study 1, Study 2 results show that the more participants took the dishonest salesperson’s perspective, the less ethically tolerant they were, when their moral self-awareness was high.

It is worth noting that the specific context used in Study 1 and Study 2 may have elicited negative stereotypical views against car salespersons that made it relatively easy to differentiate the “moral self” from the “immoral other” in perspective-taking. Past research suggests that negative stereotypical defaults often result in “convenient” social judgments when people are engaged in perspective-taking (Galinsky et al. 2003). Study 3 addressed this potential “convenience” bias by testing the generalizability of the moderated effect of perspective-taking in a different scenario. Instead of involving a car salesperson, Study 3 introduced participants to an online seller who was not identified as a professional salesperson. In addition, previous research suggests that “rationalization,” a cognitive process where people can rationalize deceptive behaviors by referring to situational factors such as marketplace norms (e.g., Mazar et al. 2008), could contribute to lower moral self-awareness. In Study 3, the potential effect of rationalization on ethical tolerance was measured and controlled for empirically.

Study 3: The Dishonest Online Seller

The purpose of Study 3 was to test whether the moderated effect of perspective-taking on ethical tolerance could be replicated beyond the context of Studies 1 and 2. Study 3 also used a different priming technique to ensure the moral self-awareness manipulation could be replicated conceptually beyond one specific priming method. In Study 3, an ordinary person reselling a product was used in place of a car salesperson to avoid stereotype-based ethical judgments from taking the seller’s perspective. Finally, Study 3 measured and explored the potential effect of “rationalization” as a covariate.

Sample, Design, and Procedure

Four hundred and four participants (205 females, Mage = 34.5) from M-Turk took part in this online experiment in exchange for a small monetary sum. The experiment employed a randomized 2 (perspective-taking vs. control) × 2 (high vs. low moral self-awareness) between-subjects design.

First, participants in high moral self-awareness condition completed a priming task, deliberating about how they demonstrate their honesty to others: “Please think about a point in time when you were being, are being, or will be honest to others. For the next few minutes, think about the ways you would show someone else that you are being honest. Please list at least 3 (and up to 10) things that you would do to demonstrate your honesty” (inspired by Sachdeva et al. 2009). All participants in the high moral-awareness condition typed in at least three pieces of reasonable narratives to demonstrate their honesty. Those participants in the low moral self-awareness condition were not given this priming task.

The priming task (vs. no priming) was pretested to examine its efficacy in manipulating moral self-awareness. One hundred and twenty-seven participants from a public university in the U.S. (73 females, Mage = 23.0) took part in this online experiment in exchange for partial course credit. They were randomly assigned to one of two conditions (i.e., priming vs. no priming). After completing the priming task (vs. not), participants completed the same moral self-awareness scale used in Studies 1 and 2 (unidimensional; α = 0.88). Results from a one-way ANOVA suggest that participants’ moral self-awareness was significantly higher in the priming condition (Mpriming = 5.87, SD = 0.95) when compared to the no-priming condition (Mno priming = 5.43, SD = 1.27), F (1,125) = 4.90, p = 0.03.

In the main study, all participants then were instructed to read a vignette describing a seller representing an ordinary person (see Web Appendix W3). In the scenario, the seller posts an online ad for a used bike. In the ad, the seller lies about the original purchase price. As in Studies 1 and 2, participants were instructed to imagine watching the situation as observers. Those in the perspective-taking condition were instructed to take the salesperson’s perspective: “While reading the scenario as an observer, please take the perspective of the salesperson. Imagine, if you will, walking in the salesperson’s shoes and thinking as the salesperson would while reading the scenario” (adapted from Galinsky et al. 2008). Participants in the control condition were not given this perspective-taking instruction.

Ethical tolerance and perspective-taking measures remained the same as those used in Studies 1 and 2. The scale of ethical tolerance was unidimensional and highly reliable (α = 0.97). In addition, Study 3 included a measure about the extent to which participants rationalized the seller’s behavior: “The seller added other costs (e.g., sales tax) when posting the purchase price of the bicycle” (1 = definitely not, 7 = definitely yes; referred to as “rationalization” hereafter). This measure was tested as a covariate to control the potential effect of rationalization. Basic demographics (e.g., age, gender) were also collected.

Results

As a manipulation check, those in the perspective-taking condition (Mperspecive-taking = 6.11, SD = 1.32) took the salesperson’s perspective to a significantly greater extent than those in the control condition (Mcontrol = 4.71, SD = 1.76), t (402) = 8.99, p < 0.001.

A 2 × 2 between-subjects ANCOVA was conducted on ethical tolerance, treating “rationalization” as a covariate. The results show that the main effect of perspective-taking was not significant (F (1,399) = 0.55, p = 0.46). Neither was the main effect of moral self-awareness priming (F (1,399) = 0.06, p = 0.81). The covariate “rationalization” was a significant predictor of ethical tolerance (F (1,399) = 90.61, p < 0.001). As expected, the interaction between moral self-awareness and perspective-taking was also significant, F (1,399) = 4.65, p = 0.03. It is noteworthy that without the covariate, the interaction remained significant, F (1,400) = 5.64, p = 0.02.

In the low moral self-awareness condition, the one-way ANOVA results show that participants’ ethical tolerance was significantly higher in the perspective-taking condition (Mperspecive-taking = 4.19, SD = 1.63) relative to the control condition (Mcontrol = 3.73, SD = 1.66), F (1,224) = 4.38, p = 0.04. Interestingly, when controlling the effect of rationalization as a covariate in one-way ANCOVA, the effect of perspective-taking on ethical tolerance was no longer significant, F (1,223) = 0.86, p = 0.36.

In the high moral self-awareness condition, the one-way ANCOVA results show that participants’ ethical tolerance was marginally lower in the perspective-taking condition (Mperspecive-taking = 3.87, SD = 1.38) relative to the control condition (Mcontrol = 4.18, SD = 1.41), F (1,175) = 3.47, p = 0.06, while the effect of rationalization was significant as a covariate, F (1,175) = 27.32, p < 0.001. Without controlling the effect of rationalization as a covariate in one-way ANOVA, the effect of perspective-taking on ethical tolerance was no longer significant, F (1,176) = 1.73, p = 0.19. Figure 3 illustrates the interaction.

Discussion

Study 3 provides further support to the hypothesis that when consumer observers’ moral self-awareness is high (vs. low), perspective-taking decreases ethical tolerance for marketplace deception. In a context where consumers observe an ordinary person (instead of a car salesperson) reselling a product, the findings replicated the moderation role of moral self-awareness in shaping the effect of perspective-taking. When moral self-awareness was low, perspective-taking increased consumers’ ethical tolerance. When moral self-awareness was high, however, the perspective-taking effect on ethical tolerance was reversed. The reversed effect of perspective-taking could not be attributed to the context-specific factor involving stereotypes against car salespersons as in Studies 1 and 2.

Further, it is evident that rationalization played a significant role in affecting ethical tolerance in relation to perspective-taking and moral self-awareness. In the low moral self-awareness conditions, rationalization appeared to account for the positive effect of perspective-taking by eliciting a greater extent of tolerance. In the high moral self-awareness conditions, the reversed effect of perspective-taking became significant when rationalization was controlled statistically, suggesting that perspective-takers were inclined to contest rather than tolerate deception.

General Discussion

In three studies, the current research proposes and demonstrates that moral self-awareness can reverse the otherwise positive perspective-taking effect on consumer observers’ ethical tolerance for marketplace deception. Study 1 shows that perspective-taking decreases, rather than increases, consumers’ ethical tolerance when their moral self-awareness is high. This effect is mediated by moral self-other differentiation, specifically when consumers contemplate about the situation from the dishonest salesperson’s perspective. Study 2 replicates the reversed perspective-taking effect by examining how consumer observers would project themselves to act from a salesperson’s standpoint. Consumers are less ethically tolerant toward a marketer’s act of deception among those who have indicated that they would act honestly (i.e., high moral self-awareness) if they were in the marketer’s situation. Study 3 replicates the moderated effect of perspective-taking in a different marketplace context, using a different method to manipulate heightened moral self-awareness. Together, these findings showcase the generalizability of the reversed perspective-taking effect on ethical tolerance when consumers observers’ moral self-awareness is high.

Contributions

Foremost, this current research is the first of its kind that experimentally manipulates and measures the novel construct moral self-awareness (Friedland and Cole 2019) in the business ethics literature. Extending previous studies on how self-oriented motivations drive ethical consumption behaviors (e.g., Hwang and Kim 2018), findings from the three studies provide unique insights on the moderating role of moral self-awareness in shaping ethical judgment beyond one’s own vantage point. Moral self-awareness vicariously elicits not only rule-based moral reasoning (i.e., “deontology”) but also moral motivations toward self-actualization (i.e., “virtue theory”). According to Friedland et al. (2020), “deontology is etymologically defined as the logic of duty. This means that what is good is taken to be a matter of strict rule-based principle and not of consequences” (pp. 3–4). By contrast, “virtue theory conceptualizes the Good as a natural developmental function of all living things. As such, it is defined psychologically as that at which all things aim, namely, self-actualization” (p. 5). Friedland et al. (2020) find that these two lines of moral reasoning are significantly overlapped as “Deontology-Virtue” (p. 17), as demonstrated by the convergence of four empirical measures of people’s tendency in making moral judgment: I try to never break any moral rules, I try to think and act logically in every situation, when I choose to act ethically, I am also choosing to become a better person, and acting ethically is more personally fulfilling to me than acting unethically (p. 17). The “Deontology-Virtue” overlapping makes it possible for perspective-takers with high moral self-awareness to evoke either of or both lines of moral judgment when in the marketplace. That is, moral reasoning driven by deontology would center on essential moral rules such as “it is morally wrong to act dishonestly.” While moral reasoning driven by self-actualization (i.e., virtue theory) would center on fulfilling one’s personal goals of being honest such as “I would be honest if I were in the marketer’s situation because acting honestly is personally fulfilling to me.” In this regard, the current work extends the research streams on moral self in the literature by revealing the role of a novel construct, moral self-awareness, compared to previously documented constructs such as “self-focused attention” (e.g., Wickland 1975; Gibbons 1990), “self-concept maintenance” (e.g., Mazar et al. 2008), and “self-consciousness” (e.g., Goukens, et al. 2009).

More specifically, the principle of deontology posits that perceived morality of one’s action depends on the intrinsic nature of the action (Conway and Gawronski 2013; Darley and Shultz 1990). Prior research shows that people tend to perceive deception as inherently wrong and react negatively regardless of harmful consequences (Shu et al. 2011; Xie et al. 2015a, b). This research shows that when taking a deceiver’s perspective, consumers’ ethical judgments can diverge as a result of their own moral compass. When moral self-awareness is high, ethical judgments tend to be consistent with the deontological principle to a greater extent. That is, when considering ethicality from a dishonest marketer’s vantage point, consumers can refer to one’s own moral self as a benchmark. The sense of being an honest person has moral implications that go beyond one’s own perspective and apply in a projected situation. Therefore, deontological ethical judgment can be inherently conditional, and it is imperative to consider the role of one’s moral self and its effects. It is important to note that the deontology and virtue-theory lines of moral reasoning can be inherently intertwined (Friedland et al. 2020). Perspective-takers can reason along deontological and/or virtue-theoretical lines when making ethical judgments regarding a dishonest marketer, specifically when their sense of the moral self is high. The reversed effect of perspective-taking on ethical tolerance can be attributed to vicarious rule-based moral reasoning and/or heightened motivation to act toward self-actualization (Friedland et al. 2020). That is, perspective-takers with high moral self-awareness may apply the rule of honesty and/or feel motivated to act honestly in the marketer’s station, which increases moral self-other differentiation, which in turn, decreases ethical tolerance for deception.

Second, the findings from this research shed new light on consumer responses to marketplace deception when deceiver- and target’s perspectives collide. Marketplace is an important social context to study deceptive behaviors and tolerance toward deception, especially from an ethical standpoint. In marketplace interactions, deception is often intentional, consequential, and morality-laden (Boush et al. 2009). In general, the marketplace exchanges require a certain level of trust between buyers and sellers to complete transactions. Consumers understand that honesty is essential for building trust toward mutually beneficial transactions. Thus, the norm of honesty provides an easy-to-access heuristic for consumers to make a quick ethical judgment about dishonest sellers. Most studies in the literature suggest that consumers naturally guard themselves against deceptive practices, which is driven by such heuristic processing (e.g., Darke and Ritchie 2007). The present research shows a less intuitive type of response. When consumers take a dishonest marketer’s perspective, they can go through either a heuristic process based on one’s self-morality, or a systemic process weighing self-morality and self-interest from another vantage point. Consumer responses to deception are contingent upon how they themselves resolve potential conflicts as a result of different social perspectives. In that sense, the present work reveals more nuanced understandings of the circumstances under which consumer judgments of marketplace deception are based on more systematic rather than heuristic processing.

Indeed, the findings from this work may have broader implications for understanding one’s ethical judgment of deception beyond the context of marketplace. For example, during workplace interactions or negotiations, when managers act dishonestly, employee’s moral/ethical judgments can vary significantly. In a similar vein, the general public is constantly exposed to news that politicians, celebrities, and influencers engage in deceptive behaviors. While some people choose to tolerate deception via perspective-taking, some others may choose to resist deception to a greater extent, depending upon their high or low moral self-awareness.

Third, this research contributes to the perspective-taking literature by revealing a novel effect driven by “moral self-other differentiation.” Prior studies use primarily “self-other overlap” (or its conceptual variants) to explain the positive effects of perspective-taking on interpersonal or social judgments (e.g., Ames et al. 2008; Davis et al. 1996). In contrast, the present research finds that perspective-takers can indeed dissociate the self from others when their moral self-awareness is high. These findings are one of the first to provide empirical evidence that consumers can distance themselves from deceivers without engaging the projected act of deception. Such “moral self-other differentiation” is clearly distinguishable from “egocentric bias” (Hattula et al. 2015) or “egocentric anchoring” (Epley et al. 2004; Sassenrath et al. 2014) in the literature, as moral self-other differentiation requires a relatively more deliberate cognitive process; one that evokes individuals to consider the complexity of other’s situations beyond egocentrism. In fact, it requires observers to make a vicarious trade-off choosing between, or balancing, projected self-interest and self-morality.

A notable theoretical implication of “moral self-other differentiation” is about two types of perspective-taking: “elaborative” vs. “intuitive.” Perspective-taking is inherently cognitive demanding and thus often requires an elaborative process. For instance, Yeomans (2019) finds that consumer recommenders enjoyed themselves less when they had to take their recipients’ perspective, because they understood that the recipients’ tastes were often different from their own. However, the perspective-taking manipulations in many prior studies may have unintentionally encouraged participants to engage in an automatic, less thoughtful, and pro-target “intuitive” process. A classic example can be seen with typical perspective-taking manipulations, which often ask research participants to “put yourself into his or her shoes.” The semantics of such instructions appear to prime participants to align their stances with the others in the first place. When the perspective-taking manipulation encourages participants to engage in more elaborative thinking, by contrast, it appears that the effects of perspective-taking become more complicated (e.g., Epley et al. 2004; Trötschel et al. 2011). For instance, Trötschel et al. (2011, p. 775) instructed participants during personal negotiations to “focus on other party’s perspective, such as the other party’s intention and interests in the negotiation.” Perspective-takers were more likely to exchange concessions on low- versus high-preference issues by identifying the potential of integrative gains (i.e., mutually beneficial). This current work demonstrates that perspective-taking effects can result from a more elaborative process, when participants contemplated what they would do in the other’s situation (Study 2). Moreover, in Studies 1 and 3, when moral self-awareness was high (vs. low), taking other’s perspective entailed making a more elaborative trade-off between self-interest and self-morality. Combined, these findings suggest that perspective-taking can involve a deliberate type of moral reasoning, which enriches process-based moral judgment models beyond one’s own vantage point (e.g., Bartels et al. 2014; Conway and Gawronski 2013).

Limitations and Future Research

This research focuses on ethical tolerance of observers who take a deceiver’s perspective. In line with prior studies documenting the difference between observers and actors (Hung and Mukhopadhyay 2012), it is plausible that the perspective-taking effect on ethical tolerance differs when consumers are the “targets” of deceptive behaviors (i.e., buyer or customer). As the example at the beginning of the introduction illustrates, a customer who has been deceived can be more emotional in response to deceptive behaviors. Therefore, the customer may access such “hot cognitions” that moderate the perspective-taking effects on ethical tolerance. Future research should explore the role of elicited emotions to understand better how being a victim of deception versus an observer of deception impacts responses to ethical tolerance. Moreover, it is noteworthy that participants’ role as a customer or observer may have also influenced participant’s cognitive busyness (Campbell and Kirmani 2000, Study 1), which suggests another direction for future research in line with a cognitive account.

Future research can also explore the dynamics of in-group vs. out-group identities between perspective-takers and deceivers. Previous research suggests that people are protective of their in-group's identity as moral when faced with a dishonest or immoral out-group member (e.g., Gino et al. 2009; Tarrant et al. 2012). For instance, in Experiment 1 of Gino et al. (2009, p. 396), research participants’ act of cheating was highest in the in-group-identity condition, when participants presumably shared the same university affiliation with a study confederate. When the confederate appeared to be from another local university (i.e., an out-group other), by contrast, participants’ act of cheating was significantly lower. Due to in-group vs. out-group identity's plausible interaction with moral self-awareness, future research should explore how social identity (e.g., group membership) influences perspective-takers’ ethical judgments.

It is also worth considering how more nuanced aspects of an individual’s personal identity impact the effect of perspective-taking as well as the process of moral self-other differentiation. That is, how do perspective-takers respond to others’ moral misconducts, when specific aspects of their identities are salient when they take the other’s perspective? For instance, future research may prime perspective-takers to think about their individuality (e.g., Ambady et al. 2004; Rank-Christman et al. 2017), or their identities as being talented, intelligent, or competent (e.g., Kirmani et al. 2017). Such nuances may move perspective-takers’ deliberation from being self-morality centric toward being self-interest centric, and thus tolerate moral misconducts to a greater extent. In a similar vein, when the rational, analytical, or logical (vs. emotional, intuitive, or affective) aspects of personal identities are salient, perspective-takers may become more deliberative (vs. intuitive) in considering the situational norms, which could moderate the outcomes of moral self-other differentiation.

Importantly, while the current work focuses on observers’ sense of moral self-awareness (i.e., awareness of their honesty), consumers can also become highly aware of their dishonest behaviors at times. That is, people’s self-awareness of their “immoral self” can be high (vs. low), which may affect the effects of perspective-taking on ethical tolerance toward others’ deceptive behaviors. When judging dishonest sellers, it is relatively easy for perspective-takers to assume that they would act honestly in the seller’s situation. However, consumers too lie (e.g., using expired coupons), especially when they are sufficiently aware that dishonest behaviors have little harmful consequences for them (Mazar et al. 2008; Shu et al. 2011). Under such circumstances, consumers’ awareness of immoral self may be high. Therefore, future research should consider examining situations under which consumers, as observers of marketer’s deception, believe that they do not have to act honestly. In some cases, such dishonesty can be rationalized without involving immoral self. For instance, a salesperson’s honest act (e.g., implying a consumer is overweight and does not fit a skirt or suit) can adversely hurt consumers’ feelings (Liu et al. 2019). If perspective-takers believe that it is legitimate to use “white lies” under such situations (e.g., Argo and Shiv 2012), their ethical tolerance may be higher. In some other cases, it would be harder for perspective-takers to justify dishonesty if they themselves knowingly and willingly cheat (e.g., in “wardrobing,” consumers purposefully purchase a product, use it, and return the used product while claiming for a full refund; e.g., see Campbell and Winterich 2018 for types of immoral consumer behaviors). Future studies should explore how one’s awareness of the darker side of the self (i.e., “immoral self-awareness”) influences the perspective-taking effect on ethical tolerance.

Lastly, it is worth noting that three test results are marginally significant as the p values are slightly higher than 0.05 (and below 0.10), which suggests the corresponding effects are indicative yet not necessarily conclusive. In experimental studies, marginal significance can be attributed to exogenous factors such as random errors and contextual variances. Future studies are needed to address marginal significance by increasing statistical power and replicating the effects beyond the current contexts. Importantly, such marginal significance would not change the focal patterns of the significant cross-cover interactions in Study 1 and Study 3 (p < 0.05), suggesting that moral self-awareness indeed moderates the effect of perspective-taking on ethical tolerance.

Concluding Remarks

This research documents a novel effect of perspective-taking on ethical tolerance for marketplace deception: perspective-taking reduces consumers’ tolerance when observing marketer’s deceptive behaviors when their awareness of moral self is high. This effect is driven by moral self-other differentiation, which demonstrates that consumers are motivated to distance their moral self from an immoral other further when taking a dishonest marketer’s perspective. The findings from three studies contribute to the ethical judgment, marketplace deception, and perspective-taking literatures, and suggest fruitful directions for future research.

Notes

In this article, “marketer” is used as a broad term referring to “a person or company that advertises or promotes something” (Lexico 2020), including a seller, a salesperson, or a sales agent. Thus, these terms will be used interchangeably throughout the manuscript.

The compensation amounts and median durations of all studies are available in Web Appendix W4.

Twenty-one participants did not follow the priming or neutral instructions by typing three sentences as instructed. Responses from those participants who followed the instructions (n = 139; 50 females, Mage = 36.9) were used for data analysis.

The original perspective-taking trait scale has seven items. In this study, participants rated all seven items. One item, “If I'm sure I'm right about something, I don't waste much time listening to other people's argument,” did not fit well with our research context, and it was inconsistent with the other six items and would significantly reduce the scale reliability to 0.53. Thus, it was excluded from the analysis.

References

Ambady, N., Paik, S. K., Steele, J., Owen-Smith, A., & Mitchell, J. P. (2004). Deflecting negative self-relevant stereotype activation: The effects of individuation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40(3), 401–408.

Ames, D. L., Jenkins, A. C., Banaji, M. R., & Mitchell, J. P. (2008). Taking another person's perspective increases self-referential neural processing. Psychological Science, 19(7), 642–644.

Anderson, E. T., & Simester, D. I. (2014). Reviews without a purchase: Low ratings, loyal customers, and deception. Journal of Marketing Research, 51(3), 249–269.

Anthony, C. I., & Cowley, E. (2012). The labor of lies: How lying for material rewards polarizes consumers' outcome satisfaction. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(3), 478–492.

Aquino, K., & Reed, A., II. (2002). The self-importance of moral identity. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 83(6), 1423–1440.

Argo, J. J., & Shiv, B. (2012). Are white lies as innocuous as we think? Journal of Consumer Research, 38(6), 1093–1102.

Argo, J. J., White, K., & Dahl, D. W. (2006). Social comparison theory and deception in the interpersonal exchange of consumption information. Journal of Consumer Research, 33(1), 99–108.

Arriaga, X. B., & Rusbult, C. E. (1998). Standing in my partner's shoes: Partner perspective-taking and reactions to accommodative dilemmas. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24(9), 927–948.

Ashkanasy, N. M., Falkus, S., & Callan, V. J. (2000). Predictors of ethical code use and ethical tolerance in the public sector. Journal of Business Ethics, 25(3), 237–253.

Barone, M. J., & Miniard, P. W. (1999). How and when factual ad claims mislead consumers: Examining the deceptive consequences of copy × copy interactions for partial comparative advertisements. Journal of Marketing Research, 36(1), 58–74.

Bartels, D. M., Bauman, C. W., Cushman, F. A., Pizarro, D. A., & McGraw, A. P. (2014). Moral judgment and decision making. In G. K. G. Wu (Ed.), Blackwell reader of judgment and decision making. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Batson, C. D., Early, S., & Salvarani, G. (1997). Perspective taking: Imagining how another feels versus imagining how you would feel. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(7), 751–758.

Berger, J., & Heath, C. (2008). Who drives divergence? Identity signaling, outgroup dissimilarity, and the abandonment of cultural tastes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(3), 593–607.

Bhattacharjee, A., Berman, J. Z., & Reed, A., II. (2013). Tip of the hat, wag of the finger: How moral decoupling enables consumers to admire and admonish. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(6), 1167–1184.

Bolton, L. E., & Reed, A., II. (2004). Sticky priors: The perseverance of identity effects on judgment. Journal of Marketing Research, 41(4), 397–410.

Boush, D. M., Friestad, M., & Wright, P. (2009). Deception in the marketplace: The psychology of deceptive persuasion and consumer self-protection. New York: Taylor and Francis.

Burgoon, J. K., Buller, D. B., White, C. H., Afifi, W., & Buslig, A. L. S. (1999). The role of conversational involvement in deceptive interpersonal interactions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(6), 669–685.

Calder, B. J. P., Lynn, W., & Tybout, A. M. (1981). Designing research for application. Journal of Consumer Research, 8(2), 197–207.

Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1966). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Campbell, M. C., & Kirmani, A. (2000). Consumers' use of persuasion knowledge: The effects of accessibility and cognitive capacity on perceptions of an influence agent. Journal of Consumer Research, 27(1), 69–83.

Campbell, M. C., & Winterich, K. P. (2018). A framework for the consumer psychology of morality in the marketplace. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 28(2), 167–179.

Cohen, T. R. (2010). Moral emotions and unethical bargaining: The differential effects of empathy and perspective taking in deterring deceitful negotiation. Journal of Business Ethics, 94, 569–579.

Cojuharenco, I., & Sguera, F. (2015). When empathic concern and perspective taking matter for ethical judgment: The role of time hurriedness. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(3), 717–725.

Coleman, N. V., & Williams, P. (2015). Looking for myself: Identity-driven attention allocation. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 25(3), 504–511.

Conway, P., & Gawronski, B. (2013). Deontological and utilitarian inclinations in moral decision making: A process dissociation approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(2), 216–235.

Cook, T., & Campbell, D. (1975). The design and conduct of experiments and quasi-experiments in field settings. In M. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational research. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally & Co.

Cowley, E., & Anthony, C. I. (2019). Deception memory: When will consumers remember their lies? Journal of Consumer Research, 46(1), 180–199.

Craft, J. L. (2013). A review of the empirical ethical decision-making literature: 2004–2011. Journal of Business Ethics, 117(2), 221–259.