“…Smog is also a symptom of maladministration and corruption—a lack of will to limit polluting factories, diesel vehicles and coal-fired power plants because politicians and officials are too docile and biddable…”—John Gapper, Financial Times.

Abstract

Environmental pollution has become a serious challenge in emerging markets. Using a unique survey of privately owned enterprises in China, this paper investigates how polluting firms respond to institutional pressures. We find that polluting firms conform to external pressures by combining relational activities and clean technology investments. However, some polluting firms alleviate regulative pressures by bribing government officials, which represents an unethical relational strategy to manage political relationship. We further analyze the contingency on firm-level political connection and local institutional conditions. Political connection buffers firms from institutional demand and demotivates firms’ willingness to respond to institutional pressures; stronger local civic activism and better bureaucratic governance curb the pollution-driven bribery, but they are not strong enough to enhance environmentally friendly practices. Collectively, our study demonstrates how polluting firms navigate institutional pressures in emerging markets, and it particularly highlights the pollution-driven bribery as an obstacle to sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Environmental pollution is becoming an increasingly serious problem around the world, especially in emerging markets. Some studies explore the possible routines to foster sustainable growth, and institutional pressures are proposed to be a powerful driving force in developed countries (Delmas 2002; Delmas and Toffel 2008; Sarkis et al. 2010; Berrone et al. 2013; Clarkson et al. 2013). However, given that emerging markets are characterized by the prevalence of corruption, bribery, and low public consciousness on environmental issues (Cai et al. 2011; Marquis et al. 2011; Giannetti et al. 2017; Jia and Mayer 2017; Lin et al. 2018; Marquis and Bird 2018), it is unclear whether and how polluting firms respond to institutional pressures in emerging markets.

We investigate polluting firms’ responses to institutional pressures using a unique survey of privately owned enterprises in China. As the largest emerging economy, China faces great challenge of environmental pollution (Marquis et al. 2011; Du 2015; Landrigan et al. 2018; Marquis and Bird 2018; Wang et al. 2018).Footnote 1 In addition to examining firms’ efforts to adopt environmentally friendly practices, we particularly explore firms’ engagement in bribery, which represents an unethical relational strategy to alleviate regulative pressures.

Our study is based on the Chinese Private Enterprise Survey (CPES), which has three advantages making it a unique dataset to test our research question. First, it contains abundant information on firms’ responses to institutional pressures. Second, we use the pollution fees charged by governments as a novel measure for corporate pollution. It is unlikely to be subject to self-reporting bias, and it is more comparable than the measures solely based on certain pollutants (e.g., carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide). Finally, the sample is restricted to family-owned small and medium-sized enterprises, which are more sensitive to institutional pressures (Berrone et al. 2010; Cheung et al. 2015).

We demonstrate double-sided effect of institutional pressures in emerging markets. On the one hand, polluting firms passively conform to external pressures by combining relational strategies and infrastructure-building strategies, which reflect on their investments in clean technology, voluntary corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting, and cooperation with nonprofit organizations (NPOs). However, on the other hand, some polluting firms take advantage of the weak institutional environment to alleviate pressures by bribing government officials, which represents an unethical relational strategy to manage political relationship. We measure bribery as firms’ entertainment expenditures, following Cai et al. (2011), Chen et al. (2013), Zeng et al. (2016), Giannetti et al. (2017), and Lin et al. (2018). 1% increase in pollution intensity is associated with 0.211% increase in bribery, which significantly misappropriates firms’ resources that could potentially be used for clean production. Our results are robust to a battery of alternative model specifications, propensity score matching, and instrumental variable regression.

We further examine the contingency on firm-level political connection and local institutional conditions. Politically connected polluting firms are less likely to adopt environmentally friendly policies or engage in bribery, suggesting that political capital buffers firms from institutional demand. Stronger local civic activism and better local bureaucratic governance discipline polluting firms’ engagement in bribery, but they are not strong enough to promote clean technology investments and relational activities. The above results indicate that the relatively weak institutional environment and the conflict between central government and local governments remain to be an obstacle to sustainability in China.

This study contributes to the literature in three ways. First, it is one of the first studies that present direct evidence on polluting firms’ engagement in bribery, and it highlights the challenge of pollution control in a corrupt society. Previous literature tries to explore the link between pollution and corruption, but they are either theoretical works (Stathopoulou and Varvarigos 2014; Biswas and Thum 2017) or based on country-level perception of corruption (Ivanova 2010; Fredriksson and Neumayer 2016). In a concurrent study, Karplus et al. (2018) find that the anti-corruption campaign in China leaded to reduction of pollution emissions in coal power plants, which indicates the pollution-related bribery from another perspective. Different from Karplus et al. (2018), we directly document the association between corporate pollution and firms’ engagement in bribery based on a representative sample across multiple industries and regions.

Second, it contributes to the institutional literature by documenting polluting firms’ institutional strategies in emerging markets. It not only provides new evidence on firms’ combination of relational strategies with infrastructure-building strategies but also adds to Marquis and Raynard (2015) by proposing firms’ engagement in unethical relational strategies. Our findings are also linked to the discussion on firms’ strategic responses to institutional pressures (Oliver 1991; Dorobantu et al. 2017) and indicate the necessity of analyzing institutional environment in emerging markets.

Third, this study also broadly contributes to the studies on the role of governments in environmental control. Previous literature usually views governments as unitary entities (Sharma and Henriques 2005; Delmas and Toffel 2008; Berrone et al. 2013). In contrast, we show that some government officials take advantage of their authority for rent seeking, indicating the decoupling between regulations and enforcement. This is complementary to recent studies on the multifaceted influences of governments on environmental pollution (Marquis et al. 2011; Jia 2017; Marquis and Bird 2018; Wang et al. 2018). We also add to this line of research by demonstrating the role of civic activism and bureaucratic governance in curbing bribery and stimulating the effective enforcement of environmental regulations.

Theory and Hypotheses Development

Institutional Theory and Institutional Pressures for Polluting Firms

According to the institutional theory, firms need to conform to social and cultural pressure to obtain legitimacy (Meyer and Rowan 1977; Oliver 1991; Delmas 2002; Scott 2005; Marquis and Raynard 2015; Dorobantu et al. 2017). Meyer and Rowan (1977) summarize institutional pressure as rationalized myth and ceremony, and it is widely used to analyze organizational behavior with social externalities (Delmas and Toffel 2008; Berrone et al. 2010; Sarkis et al. 2010; Marquis et al. 2011; Marquis and Bird 2018). For instance, Berrone et al. (2013) use it to analyze firms’ investments in environmental innovations, and Delmas and Toffel (2008) use it to analyze the voluntary adoption of environmental control systems.

Two types of institutional pressures are discussed in the literature: regulative pressure and normative pressure (Scott 2005; Delmas and Toffel 2008; Berrone et al. 2013; Luo et al. 2016; Marquis and Bird 2018), which correspond to governments and the public as two key stakeholders. Regulative pressure is introduced by governments in form of laws or regulations, and normative pressure stems from implicit norms shared by the public.

The regulative pressure from governments is viewed as an important driving force for environmental protection (Sarkis et al. 2010; Berrone et al. 2013). In emerging economies, governments are also essential actors of pollution control (Marquis et al. 2011; Marquis and Qian 2014; Marquis and Bird 2018; Wang et al. 2018). However, the role of governments is challenged by the prevalence of corruption and bribery (Bertrand et al. 2007; Cai et al. 2011; Mironov 2015; Oliva 2015; Birhanu et al. 2016), and local governments could also give priority to short-term economic growth (Marquis et al. 2011; Jia and Mayer 2017; Luo et al. 2017; Marquis and Bird 2018; Wang et al. 2018). Thus, it is an open question whether governments act as an effective monitor in emerging markets.

The public imposes pressures through implicitly shared values (Berrone et al. 2010; Surroca et al. 2013; Du 2015; Luo et al. 2016; Marquis et al. 2016; Chen et al. 2018). Berrone et al. (2010) document the negative association between family ownership and pollution emissions and attribute it to family firms’ incentives to reduce normative pressure. Capital market-based research on CSR essentially reflects the power of normative pressures (e.g., Dhaliwal et al. 2011; 2012; Lins et al. 2017). Normative pressure could also stimulate the enforcement of environmental regulations and reduce local governments’ motivation to pursue short-term economic growth (Marquis et al. 2011, 2016; Marquis and Bird 2018).

Institutional Environment in Emerging Markets: Corruption and Political Extraction

Corruption and bribery are common phenomenon in emerging markets. According to the Corruption Perceptions Index 2017 issued by the Transparency International, the “BRIC” countries have low rankings among all the 180 rated countries. Brazil, Russia, India, and China are ranked as 96, 135, 81, and 77, respectively. The corruption problem in emerging markets is widely discussed in the literature. For instance, Mironov (2015) examines how management teams’ engagement in corruption influences firms’ operations in Russia. Bertrand et al. (2007) and Niehaus and Sukhtankar (2013) investigate the corruption in India. Some studies discuss corruption in Brazil (Halter et al. 2009), China (Cai et al. 2011; Zeng et al. 2016; Lin et al. 2018), Mexico (Oliva 2015), Vietnam (Nguyen and Van Dijk 2012), and African and Latin American countries (Birhanu et al. 2016).

Another related phenomenon is governments’ direct expropriation of private entities’ benefits (Xu 2011; Firth et al. 2013; Du et al. 2015; Jia and Mayer 2017), and it is directly conducted by government agencies instead of individual officials (Firth et al. 2013; Jia and Mayer 2017). Jia and Mayer (2017) examine the unauthorized levies as a specific form of expropriation. It is influenced by a firm’s political connection and relative bargaining power (Du et al. 2015; Ma et al. 2015; Jia and Mayer 2017), and it also shows variations across regions due to local bureaucratic governance (Firth et al. 2013).

Governments in emerging markets show multifaceted and even conflicting influence on environmental control, which further distorts firms’ institutional strategies (Jia 2017; Luo et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2018). In China, for instance, although central government shows high motivation to reduce pollution, local governments usually give priority to short-term economic growth (Jia 2017; Wang et al. 2018). Luo et al. (2017) find that firms controlled by local governments are more likely to issue low-quality CSR reports. Similarly, Jia and Nie (2017) find that local governments have low incentives to monitor workplace safety.

Institutional Strategies in Emerging Markets

A growing stream of literature investigates the strategies to navigate the institutionally diverse environment in emerging markets (Hoskisson et al. 2000; Peng 2003; Marquis and Raynard 2015; Dorobantu et al. 2017). Marquis and Raynard (2015) review this body of literature and summarize it under the umbrella of institutional strategies. Three sets of institutional strategies are identified: infrastructure-building strategies, relational strategies, and socio-cultural bridging strategies. The infrastructure-building strategies refer to the ones to develop infrastructure that are currently inadequate or missing, relational strategies are used to cultivate the relationship with key stakeholders, and socio-cultural bridging strategies address the social-cultural conflicts.

Nonmarket strategies are also developed to cope with the weak institutional environment. Dorobantu et al. (2017) discuss nonmarket strategies through the lens of new institutional economics, and they propose that firms can either adapt their strategies to the existing environment, invest resources to improve it, or even transform it. Likewise, Oliver (1991) argues that firms not only passively conform to institutional environment but also employ proactive strategies to avoid or manipulate the environment.

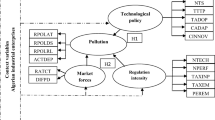

Hypotheses

Firms’ Infrastructure-Building Strategies by Investing in Clean Technology

The direct response of polluting firms to meet institutional demand is to reduce pollution (Delmas 2002; Delmas and Toffel 2008; Berrone et al. 2010; Sarkis et al. 2010; Marquis et al. 2011). We focus on firms’ investments in clean technology, which can be used to build inadequate technological infrastructure, as suggested by Marquis and Raynard (2015). In developed countries with good institutional environment, polluting firms tend to reduce pollution to respond to external pressures (Berrone et al. 2010; Sarkis et al. 2010). If institutional pressures also play a positive role in emerging markets, polluting firms would be more willing to invest in clean technology. We propose the following hypothesis:

H1a

Polluting firms respond to institutional pressures by investing more in clean technology to build the technological infrastructure for clean production.

Firms’ Relational Strategies by Issuing CSR Reports and Cooperating with NPOs

Polluting firms are expected to cultivate stakeholder relationship by voluntarily disclosing CSR information. Voluntary CSR disclosure is an effective way to communicate with stakeholders and build positive social image (Dhaliwal et al. 2011, 2012; Clarkson et al. 2013; Marquis and Qian 2014; Lys et al. 2015; Marquis et al. 2016). Previous literature documents various benefits of CSR disclosure, such as lower cost of capital (Dhaliwal et al. 2011), more accurate analyst forecasting (Dhaliwal et al. 2012), and higher firm value (Clarkson et al. 2013). It also works as a monitoring mechanism to improve firms’ environmental performance (Chen et al. 2018). Meanwhile, some studies raise the concern of green washing and selective disclosure (Clarkson et al. 2008; Marquis and Qian 2014; Marquis et al. 2016; Luo et al. 2017).

Cooperating with NPOs is another way to respond to institutional demand. Such cooperation contributes to a firm’s social capital and builds up the trust between firms and stakeholders (Luo et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2016; Lins et al. 2017; Zheng et al. 2019). It can also be used to offset corporate misconducts (Du 2015; Gao et al. 2017; Luo et al. 2018) and reduce uncertainty by providing “insurance-like” protection (Godfrey 2005; Godfrey et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2016). In sum, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1b

Polluting firms are more likely to cultivate stakeholder relationship by issuing CSR reports and cooperating with NPOs.

Firms’ Engagement in Bribery as Unethical Relational Strategy

We expect that polluting firms could circumvent the enforcement of environmental regulations through bribery activities. Despite its substantial improvement, China is still characterized by the prevalence of corruption and bribery (Cai et al. 2011; Xu 2011; Du et al. 2015; Lin et al. 2018). Bribery can help private firms remove regulatory roadblocks and obtain government-controlled resources (Cai et al. 2011; Chen et al. 2013; Giannetti et al. 2017). The anti-corruption campaign in China significantly reduced coal power plants’ pollution emissions (Karplus et al. 2018), which implies the pollution-related bribery from another perspective. Bribery is also used by individuals to cheat in vehicle emission tests in Mexico (Oliva 2015).

Bribery can be further accelerated by local governments’ priority to short-term economic growth. Different from the central government’s target to foster sustainable development, local governments tend to give priority to short-term economic growth (Marquis et al. 2011; Marquis and Qian 2014; Jia 2017; Jia and Nie 2017; Luo et al. 2017; Marquis and Bird 2018; Wang et al. 2018). Hence, local governments are expected to be tolerant of pollution and bribery, which makes bribery a feasible way to alleviate polluting firms’ exposure to regulative pressures. We propose the following hypothesis:

H1c

As an unethical relational strategy, polluting firms are more likely to engage in bribery activities.

Contingency on Firm-Level Political Connection

We expect that political connection reduces institutional pressures, thus politically connected polluting firms are less willing to adopt environmentally friendly policies. Previous literature finds that political connection contributes to firms’ social capital and buffers firms from institutional demand (Du 2015; Zhang et al. 2016; Gao et al. 2017). When a politically connected firm is involved in environmental misconducts, it is less likely to take actions to improve its reputation (Du 2015; Zhang et al. 2016). Similarly, Gao et al. (2017) find that political connection reduces external uncertainty, implying firms’ less exposure to institutional demand.

Political connection could also reduce the incentives of bribery. Political connection deters government expropriation and the bribes extracted by individual officials (Jia and Mayer 2017). Karplus et al. (2018) find that the anti-corruption campaign in China only affected private power plants rather than state-owned power plants, which implies that political connection reduces regulatory pressures. Some studies also document the benefits of political connection to trade expansion and the access to government-controlled bank loans (Lu 2011; Zhao and Lu 2016). We propose the following hypotheses:

H2a

Politically connected polluting firms invest less in clean technology.

H2b

Politically connected polluting firms adopt less relational activities.

H2c

Politically connected polluting firms engage less in bribery.

Contingency on Local Institutional Conditions

Institutional strategies could show contingency on local civic activism and bureaucratic governance. Environmental enforcement is usually decoupled from regulations in China (Marquis et al. 2011; Marquis and Qian 2014; Jia 2017; Luo et al. 2017), and local civic activism contributes to the improved enforcement in recent years (Marquis et al. 2011; Luo et al. 2016; Marquis and Bird 2018), which would result in more investments in environmentally friendly policies and less engagement in bribery. Likewise, Luo et al. (2018) find that local civic capacity mitigates adverse selection and reduces the likelihood of firms using philanthropy to hide away their environmental misconducts.

Bureaucratic governance could also affect local governments’ attitude to corruption and the enforcement of environmental regulations. Political extraction shows variations across regions (Xu 2011; Firth et al. 2013; Du et al. 2015; Jia and Mayer 2017), and firms located in provinces with inadequate bureaucratic governance are likely to be grabbed by local governments, which results in lower firm value, lower firm performance, and lower labor productivity (Firth et al. 2013; Jia and Mayer 2017). Consequently, firms facing inadequate bureaucratic governance would be more likely to resort to bribery and less likely to adopt environmentally friendly practices. We propose the following hypotheses:

H3a

Stronger local civic activism and better bureaucratic governance enhance polluting firms’ investments in clean technology.

H3b

Stronger local civic activism and better bureaucratic governance enhance polluting firms’ adoption of relational activities.

H3c

Stronger local civic activism and better bureaucratic governance reduce polluting firms’ engagement in bribery.

Research Design

Data

Our sample is based on the Chinese Private Enterprises Survey (CPES) collected by the Privately Owned Enterprises Research Project Team. To ensure representativeness, the multiple-stage stratified random sampling was employed to select sample firms across provinces in mainland China. The CPES has been widely used in previous studies, such as Lu (2011), Chen et al. (2013), Du (2015), and Jia and Mayer (2017). Our study is based on the survey in early 2012, which reflects the information in 2011.Footnote 2 We exclude observations from the finance and utilities industries, further eliminate those with zero or missing sales revenue, and those with missing variables. The final sample includes 3557 firm observations. The sample distribution across province, size, and industry are reported in Appendix Table 11.

Variables

Corporate Pollution Intensity

We use corporate pollution intensity as the proxy for the institutional pressures that a firm is exposed to. Polluting firms usually have negative social images because of their impacts on natural environment, consequently, firms with higher pollution intensity are expected to receive more pressures from the public and governments. The same viewpoint is shared by previous literature. For instance, Marquis et al. (2016) find that environmentally damaging firms are subject to more criticisms from media and the public. Marquis et al. (2011) and Marquis and Bird (2018) find that environmental regulations and enforcement tend to target at highly polluting firms. We measure corporate pollution intensity as the pollution fees charged by the Ministry of Environmental Protection of China (MEP), and it is calculated as the natural logarithm of one plus pollution fees per 10,000 RMB (approximately 1548 USD) of sales revenue.

Dependent Variables

-

(i)

Clean technology investments A firms’ investment in clean technology, Clean Tech, is used as a proxy for firms’ efforts to control pollution, which corresponds to the infrastructure-building strategies in Marquis and Raynard (2015). It is measured as the natural logarithm of one plus clean technology investments per 10,000 RMB of sales revenue.

-

(ii)

Voluntary CSR reports CSR Report is a binary variable that equals one if a firm issues a standalone CSR report and zero otherwise, following Dhaliwal et al. (2011, 2012). Although it is mandatory for a subset of publicly listed firms in China to issue CSR reports after 2008 (Ioannou and Serafeim 2014; Chen et al. 2018), our sample is isolated from this regulation because it is restricted to the family-owned small and medium-sized enterprises.

-

(iii)

Cooperation with NPOs NPO Cooperation is a binary variable indicating whether a firm cooperates with nonprofit organizations (NPOs). Two types of NPOs exist in China: government-affiliated NPOs and private NPOs (Zheng et al. 2019). NPO Cooperation takes the value one if a firm has cooperation with either government-affiliated NPOs or private NPOs and zero otherwise.

-

(iv)

Bribery engagement We measure a firm’s engagement in bribery based on its entertainment expenditures. Since bribery is illegal, it is difficult to be directly observed. We take advantage of the expense reimbursement system in China and focus on the bribery associated with entertainment activities. Inviting government officials to eat or drink or giving extravagant gifts is a common form of bribery in China, and the recent anti-corruption reform also targets to cut down the extravagant consumptions of government officials (Lin et al. 2018). The corporate employees that execute bribery activities usually need to reimburse their payments through the Entertainment and Travel Costs account, which gives us an opportunity to measure a firm’s engagement in bribery. This measure has been widely used in the literature, such as Cai et al. (2011), Chen et al. (2013), Zeng et al. (2016), Giannetti et al. (2017), and Lin et al. (2018).

We measure Bribery Engagement as the natural logarithm of one plus a firm’s entertainment expenditures per 10,000 RMB of sales revenue. Cai et al. (2011) view entertainment and travel expenses as a mix of bribes, insiders’ private benefits, and normal business expenditures. Given that our sample is restricted to owner-managed family firms, insiders’ private benefit is not a serious issue (Chen et al. 2013). Moreover, like Giannetti et al. (2017), we observe firms’ entertainment expenditures instead of entertainment and travel expenses, thus it is unlikely to be biased by the legitimate business travels.

Regression Specification

The regression specification is as follows:

\({\text{Responses}}_{i}\) represents firms’ institutional strategies, including clean technology investments, relational activities, and bribery engagement. Probit model is used when regressing with CSR Report and NPO Cooperation, and Tobit model is used to estimate Clean Tech and Bribery Engagement since both variables are left-censored at zero.

We control for firm characteristics, including firm size, leverage, profit margin, proportion of intangible assets, export proportion, and innovation intensity.Footnote 3 We also control for entrepreneur characteristics, including age, gender, education, working experience at multinational enterprises, and political connection. When regressing on bribery engagement, governance structure and relational capital are further controlled following Zeng et al. (2016). We use executive compensation and whether a firm has board of directors as the proxy for government structure. Accounts receivable and accounts payable are used as the proxy for relational capital with clients and suppliers.

The province fixed effects and industry fixed effects are included to control for the influence of regional and industrial factors. Detailed descriptions of variables are listed in Appendix Table 10. All continuous variables are winsorized at the 1% and 99% levels. To mitigate serial correlation within province and industry, two-way clustered standard errors are used following the suggestions of Petersen (2009).

Summary Statistics

Table 1 reports summary statistics for the main variables. Panel B shows the statistics for corporate pollution intensity. 37% of sample firms are charged pollution fees, and the average pollution fee is 15.43 RMB per 10,000 RMB of sales revenue. The mining, hotels and restaurants, and health industries are the ones with the most severe pollution, as reported in Appendix Table 12.

As shown in Panel A, the mean value of clean technology investments is 50.49 RMB per 10,000 RMB of sales revenue, more than three times the amount of pollution fees. 5% of firms voluntarily issue CSR reports, and 39% of firms cooperate with NPOs. The average Bribery Engagement is 169.86 RMB per 10,000 RMB of sales revenue, and the maximum value is 3125 RMB, which represents significant costs for firm operations.

The statistics for control variables are reported in Panel C. The average firm size measured as sales revenue is 87.42 million RMB (approximately 13.53 million USD). Debt accounts for 19% of total assets, average profit margin is 0.11, intangible assets represent 10% of total assets, 5% of sales are from export, and firms invest 98.19 RMB per 10,000 RMB of sales revenue in innovation. For entrepreneur-level controls, the average age of entrepreneurs is 45 years old, 16% of them are female, 63% of them received higher education, 7% of them have working experience at multinational enterprises, and 41% of them have political connection. Furthermore, 50% of firms have boards of directors, and the average annual salary of entrepreneurs is 0.19 million RMB (0.03 million USD).

We check the correlation of independent variables in Table 2. Controls do not show high correlation, and there is no significant multicollinearity concern. The only exception is the one between accounts receivable and accounts payable, with a correlation coefficient of 0.66, indicating firms’ similar relational capital with clients and suppliers. We exclude accounts payable from the controls as a robustness check, and the results are similar.

Main Results

Polluting Firms’ Adoption of Environmentally Friendly Policies

We first analyze whether polluting firms respond to institutional pressures by adopting environmentally friendly policies. Column 1 of Table 3 corresponds to the results on clean technology investments. Consistent with H1a, the coefficient estimate of Pollution Intensity is 1.499, which is statistically significant at the 1% level. It suggests that polluting firms show high incentives to conform to institutional demand by building technological infrastructure (Marquis and Raynard 2015), which is in line with previous studies based on developed countries (Delmas 2002; Delmas and Toffel 2008; Sarkis et al. 2010; Berrone et al. 2013). With pollution intensity increasing by one standard deviation, clean technology investments increase by 612% (= 63.01/15.43 × 1.499).

Columns 2–3 present polluting firms’ propensity to issue CSR reports and cooperate with NPOs. Consistent with H1b, Pollution Intensity is positively associated with CSR Report and NPO Cooperation. It suggests that polluting firms combine relational strategies with infrastructure-building strategies to navigate institutional pressures, which is consistent with the institutional strategy theory proposed by Marquis and Raynard (2015). One standard deviation increase of pollution intensity raises the propensity of CSR disclosure by 3.73% (= ln(63.01) × 0.009) and the propensity of cooperating with NPOs by 13.26% (= ln(63.01) × 0.032).

The Dark Side of Institutional Pressures: Polluting Firms’ Engagement in Bribery

We analyze polluting firms’ engagement in bribery in Table 4. Consistent with H1c, corporate pollution intensity is positively associated with bribery engagement, suggesting that firms with higher pollution intensity are more likely to bribe government officials to circumvent the enforcement of environmental regulations. The results are robust to controlling for governance structure and firms’ relational capital with clients and suppliers.

The coefficient estimate of Pollution Intensity is 0.211 after introducing all the controls in column 4. With polluting intensity increasing by one standard deviation (i.e., 63.01/15.43 = 408%), bribery engagement increases by 86.09% (= 408% × 0.211). Given that the average sales revenue is 87.42 million RMB, and the average bribes per 10,000 RMB of sales revenue is 169.86 RMB, one standard deviation increase of pollution intensity is linked to 1.28 million increase of bribes (= 8742 × 169.86 × 86.09%), which represents significant cost given that the average profit is only 9.62 million RMB (= 87.42 × 0.11). This suggests that bribery takes up significant resources that could potentially be used for clean production, indicating the negative social impacts of unethical relational strategies.

Contingency on Firm-Level Political Connection

We investigate the contingency on firm-level political connection in Table 5. Two proxies for political connection are employed: Connection via CPC/CPPCC and Connection via ACFIC. The first proxy is based on the membership of the Chinese People’s Congress (CPC) and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), two most important political institutions in China. A firm is viewed as having political connection if its entrepreneur is a deputy of the CPC or a member of the CPPCC. It has been widely used in previous literature, such as Lu (2011), Jia (2014), Zhao and Lu (2016), and Du (2017).

The second proxy is based on the membership of the All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce (ACFIC), a business association initiated and controlled by governments. The ACFIC is a springboard to politics, and the members of the ACFIC have high chances to obtain formal political identities (Ma et al. 2015). A firm has political connection if its entrepreneur is a member of the ACFIC, following Jia (2014) and Ma et al. (2015).

The odd columns in Table 5 correspond to the firms without political connection, and the even columns are those with political connection. Although Pollution Intensity shows positive association with dependent variables in both odd and even columns, the coefficient estimates in even columns are significantly lower than those in odd columns. This finding indicates that political connection demotivates a firm’s willingness to respond to institutional demand. It is worth noting that, when a firm’s entrepreneur has the CPC or CPPCC membership, Pollution Intensity is not significantly associated with Bribery Engagement. It indicates the substitutive relationship between political connection and bribery in alleviating regulatory pressures.

Contingency on Local Institutional Conditions

We analyze the contingency on local civic activism and bureaucratic governance in Table 6. We take advantage of the debate on PM2.5 in 2011 to measure local civic activism on environmental pollution. China experienced severe air pollution in Winter 2011, whereas the air quality reports released by China government substantially deviated from those released by the US Embassy in China, wherein PM2.5 was the main indicator. This triggered a debate on whether to include PM2.5 into the air quality reports.

Two proxies of civic activism are constructed: public consciousness and media scrutiny on environmental issues. We measure public consciousness as local Baidu internet search volume of PM2.5 between October 2011 and February 2012, scaled by province-level population. This measure reflects civic activism on the internet, an important channel to execute civil mobilization in the internet age (Luo et al. 2016). As shown in Fig. 1 in Appendix, the internet search volume of “PM2.5” dramatically increased after October 2011. Figure 2 shows the scaled internet search volume across provinces.

We measure media scrutiny as the scaled local media reports on PM2.5. Media scrutiny imposes pressures on local governments and firms to control pollution (Marquis et al. 2016; Marquis and Bird 2018). We collect regional media reports between October 2011 and February 2012 from the Dow Jones Factiva, and the language is restricted to simplified Chinese. 398 news reports are finally identified, and the regional distribution is illustrated in Fig. 3.

We measure local bureaucratic governance as the province-level proportion of administrative expenditures in total fiscal expenditures, following Firth et al. (2013), and the data is collected from the China Statistical Yearbook. Local governments with higher administrative expenditures usually have lower efficiency and worse bureaucratic governance. The proportion of administrative expenditures across provinces are illustrated in Fig. 4.

Panel D in Table 6 shows the results on Bribery Engagement. The coefficients of Pollution Intensity are positive and statistically significant in all columns, indicating that pollution-driven bribery is a common phenomenon in China. The coefficients of Pollution Intensity in even columns are significantly lower than those in odd columns. This is consistent with H3c and suggests that local civic pressure and bureaucratic governance reduce polluting firms’ engagement in bribery.

Panel A, B, and C correspond to firms’ incentives to adopt environmentally friendly policies. Pollution Intensity is positively associated with Clean Tech, CSR Report, and NPO Cooperation in all columns. However, local institutional conditions do not play a significant role as expected in H3a and H3b. Currently the civic activism seems not to be strong enough in China, and more civic pressure is required in the future to ensure sustainable transformation. Meanwhile, since environmental control is mainly initiated by central government (Marquis and Qian 2014), the role of local bureaucratic governance in promoting clean production is limited.Footnote 4 Overall, although local civic activism and bureaucratic governance curb pollution-driven bribery, they are not strong enough to enhance investments in clean production infrastructure and adoption of relational activities.

Robustness Tests

Alternative Model Specifications

We try a variety of alternative model specifications to ensure the robustness of main results. First, we use Pollution Dummy as an alternative measure of corporate pollution. As reported in Panel A of Table 7, all the coefficients of Pollution Dummy are statistically significant. We also estimate using the observations with positive pollution fees, and the results are robust to this subsample estimation, as shown in Panel B.

Second, we use industry-adjusted pollution intensity as an alternative measure. As shown in Panel C, the results are qualitatively similar. In addition, we separately estimate the firms in manufacturing industry (Panel D) and nonmanufacturing industries (Panel E), and the results are similar across two subsamples.

Finally, alternative dependent variables are used. We first use two alternative measures for pollution control: the dummy variable Clean Tech_d and firms’ investments in operational process improvement Process Improving, which is viewed as an effective way to reduce pollution (Delmas and Toffel 2008; Sarkis et al. 2010). Second, we differentiate two types of NPOs in China: government-affiliated NPOs and private NPOs. Finally, we use the dummy variable Bribery Engagement_d as an alternative measure for bribery engagement. We also examine polluting firms’ collusion with governments by using unauthorized levies as the dependent variable. As reported in Panel F, the results are similar.

Propensity Score Matching

One concern is that our linear model might not be properly specified, and it would be subject to estimation biases due to functional form misspecification (Shipman et al. 2017). We use propensity score matching (PSM) to alleviate this concern. The treatment/control groups are defined based on Pollution Dummy. Following the suggestions of Shipman et al. (2017), we use all the control variables to estimate the propensity score of a firm being charged positive pollution fees, and the results are reported in Appendix Table 13. One-to-one matching without replacement is employed, and the caliper value is set to be 0.01. Panel A of Table 8 shows the average treatment effects, and Panel B shows the regression based on the matched sample, which is similar to our main results.

Instrumental Variable Regression

Omitted variables and reverse causality might make the estimates biased, and we employ instrumental variables to alleviate the endogeneity concern. Two instrumental variables are used: Industry Average Pollution Intensity and Province Average Pollution Intensity. Given that corporate environmental performance shows variations across industries and regions (Clarkson et al. 2008; Marquis and Bird 2018; Wang et al. 2018), we expect that corporate pollution intensity is influenced by industrial technology and regional regulations. Since firm-level environmental performance determines their responses to institutional pressures (Marquis et al. 2011, 2016), the industry-level and province-level pollution intensity should affect firms’ institutional strategies only through influencing the firm-level pollution intensity, and they are unlikely to directly affect the dependent variables given the great variations across firms, which thus meets the exclusion restriction.

Column 1 of Table 9 shows the first-stage regression. The instrumental variables are positively associated with firm-level Pollution Intensity. Columns 2–5 show the second-stage regression. Instrumented Pollution Intensity shows a significantly positive association with all the dependent variables, and the coefficients are greater than that of main results. Overall, our findings are robust to instrumental variable regression.

Conclusions

This study investigates how polluting firms respond to institutional pressures in an emerging market. We find that polluting firms invest more in clean technology and are more likely to adopt relational strategies to cultivate stakeholder relationship. On the other hand, we highlight the dark side of institutional pressures in emerging markets, that is, polluting firms’ engagement in bribery, which misappropriates firms’ resources for clean production. We further examine the contingency on firm-level political connection and local institutional conditions. Firm-level political connection buffers firms from institutional demand; stronger local institutional conditions curb the pollution-driven bribery, but they are not enough to enhance clean technology investments and relational activities.

Our study provides valuable implications. First, despite widespread criticism on the pollution in emerging markets, we find that institutional pressures play a positive role in stimulating polluting firms’ infrastructure-building strategies and relational strategies. Second, our study highlights an institutional disadvantage in emerging markets: corruption and bribery. Emerging economies would undoubtedly benefit from their anti-corruption efforts. Third, our findings suggest the role of civic activism and bureaucratic governance in disciplining bribery, and they are especially useful under the incomplete legal system in emerging markets.

This study has several limitations and could stimulate follow-up research in the future. First, given that bribery is illegal and difficult to be directly observed, and different form of bribery could be taken in other countries, future research based on confidential datasets could provide more evidence. Second, our cross-sectional dataset lacks insights from a longitudinal perspective, and it limits our ability to fully address the endogeneity concern, future studies based on panel dataset and natural experiment would shed new light on our story.

Notes

As reported by the World Health Organization (WHO), among the 499 most polluted cities during 2008–2016, 287 are in China. In 2015, 1.8 million people died in China because of pollution-related diseases (Landrigan et al. 2018).

The sample firms of CPES change every year, and the survey questions also show variations across years. Consequently, we cannot obtain a panel dataset, and the firm fixed effects model does not work in this case.

Duanmu et al. (2018) document the influence of market competition on environmental performance. The profit margin in our regression can partially capture the firm-specific market power (Kale and Loon 2011; Dass et al. 2015), and the industry-specific market competition can be captured by the industry fixed effects.

We also run an ex-post test to see whether local institutional conditions stimulate politically connected polluting firms’ responses to institutional pressures. We implement it by introducing the three-way interaction terms of Pollution Intensity, Political Connection, and local institutional conditions. The untabulated results show that the coefficients of three-way interaction terms are not statistically significant, implying that currently the local institutional conditions are not strong enough to push politically connected polluting firms out of their comfort zone.

References

Berrone, P., Cruz, C., Gomez-Mejia, L. R., & Larraza-Kintana, M. (2010). Socioemotional wealth and corporate responses to institutional pressures: Do family-controlled firms pollute less? Administrative Science Quarterly, 55(1), 82–113.

Berrone, P., Fosfuri, A., Gelabert, L., & Gomez Mejia, L. R. (2013). Necessity as the mother of ‘green’ inventions: Institutional pressures and environmental innovations. Strategic Management Journal, 34(8), 891–909.

Bertrand, M., Djankov, S., Hanna, R., & Mullainathan, S. (2007). Obtaining a driver’s license in India: An experimental approach to studying corruption. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(4), 1639–1676.

Birhanu, A. G., Gambardella, A., & Valentini, G. (2016). Bribery and investment: Firm-level evidence from Africa and Latin America. Strategic Management Journal, 37(9), 1865–1877.

Biswas, A. K., & Thum, M. (2017). Corruption, environmental regulation and market entry. Environment and Development Economics, 22(1), 66–83.

Cai, H., Fang, H., & Xu, L. C. (2011). Eat, drink, firms, government: An investigation of corruption from the entertainment and travel costs of Chinese firms. Journal of Law and Economics, 54(1), 55–78.

Chen, Y., Hung, M., & Wang, Y. (2018). The effect of mandatory CSR disclosure on firm profitability and social externalities: Evidence from China. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 65(1), 169–190.

Chen, Y., Liu, M., & Su, J. (2013). Greasing the wheels of bank lending: Evidence from private firms in China. Journal of Banking & Finance, 37(7), 2533–2545.

Cheung, Y., Kong, D., Tan, W., & Wang, W. (2015). Being good when being international in an emerging economy: The case of China. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(4), 805–817.

Clarkson, P. M., Fang, X., Li, Y., & Richardson, G. (2013). The relevance of environmental disclosures: Are such disclosures incrementally informative? Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 32(5), 410–431.

Clarkson, P. M., Li, Y., Richardson, G. D., & Vasvari, F. P. (2008). Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical analysis. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(4), 303–327.

Dass, N., Kale, J. R., & Nanda, V. (2015). Trade credit, relationship-specific investment, and product market power. Review of Finance, 19(5), 1867–1923.

Delmas, M. A. (2002). The diffusion of environmental management standards in Europe and in the United States: An institutional perspective. Policy Sciences, 35(1), 91–119.

Delmas, M. A., & Toffel, M. W. (2008). Organizational responses to environmental demands: Opening the black box. Strategic Management Journal, 29(10), 1027–1055.

Dhaliwal, D. S., Li, O. Z., Tsang, A., & Yang, Y. G. (2011). Voluntary nonfinancial disclosure and the cost of equity capital: The initiation of corporate social responsibility reporting. The Accounting Review, 86(1), 59–100.

Dhaliwal, D. S., Radhakrishnan, S., Tsang, A., & Yang, Y. G. (2012). Nonfinancial disclosure and analyst forecast accuracy: International evidence on corporate social responsibility disclosure. The Accounting Review, 87(3), 723–759.

Dorobantu, S., Kaul, A., & Zelner, B. (2017). Nonmarket strategy research through the lens of new institutional economics: An integrative review and future directions. Strategic Management Journal, 38(1), 114–140.

Du, X. (2015). Is corporate philanthropy used as environmental misconduct dressing? Evidence from Chinese family-owned firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 129(2), 341–361.

Du, X. (2017). Religious belief, corporate philanthropy, and political involvement of entrepreneurs in Chinese family firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 142(2), 385–406.

Du, J., Lu, Y., & Tao, Z. (2015). Government expropriation and Chinese-style firm diversification. Journal of Comparative Economics, 43(1), 155–169.

Duanmu, J. L., Bu, M., & Pittman, R. (2018). Does market competition dampen environmental performance? Evidence from China. Strategic Management Journal, 39(11), 3006–3030.

Firth, M., Gong, S. X., & Shan, L. (2013). Cost of government and firm value. Journal of Corporate Finance, 21, 136–152.

Fredriksson, P. G., & Neumayer, E. (2016). Corruption and climate change policies: Do the bad old days matter? Environmental & Resource Economics, 63(2), 451–469.

Gao, Y., Lin, Y. L., & Yang, H. (2017). What’s the value in it? Corporate giving under uncertainty. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 34(1), 215–240.

Giannetti, M., Liao, G., You, J., & Yu, X. (2017). The externalities of corruption: Evidence from entrepreneurial activity in China. SSRN working paper.

Godfrey, P. C. (2005). The relationship between corporate philanthropy and shareholder wealth: A risk management perspective. Academy of Management Review, 30(4), 777–798.

Godfrey, P. C., Merrill, C. B., & Hansen, J. M. (2009). The relationship between corporate social responsibility and shareholder value: An empirical test of the risk management hypothesis. Strategic Management Journal, 30(4), 425–445.

Halter, M. V., De Arruda, M. C. C., & Halter, R. B. (2009). Transparency to reduce corruption? Journal of Business Ethics, 84(3), 373–385.

Hoskisson, R. E., Eden, L., Lau, C. M., & Wright, M. (2000). Strategy in emerging economies. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3), 249–267.

Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2014). The consequences of mandatory corporate sustainability reporting: Evidence from four countries. Harvard Business School working paper.

Ivanova, K. (2010). Corruption and air pollution in Europe. Oxford Economic Papers, 63(1), 49–70.

Jia, N. (2014). Are collective political actions and private political actions substitutes or complements? Empirical evidence from China’s private sector. Strategic Management Journal, 35(2), 292–315.

Jia, R. (2017). Pollution for promotion. SSRN working paper.

Jia, N., & Mayer, K. J. (2017). Political hazards and firms’ geographic concentration. Strategic Management Journal, 38(2), 203–231.

Jia, R., & Nie, H. (2017). Decentralization, collusion, and coal mine deaths. Review of Economics and Statistics, 99(1), 105–118.

Kale, J. R., & Loon, Y. C. (2011). Product market power and stock market liquidity. Journal of Financial Markets, 14(2), 376–410.

Karplus, V. J., Zhang, S., & Almond, D. (2018). Investigating corrupt mayors reduces SO2 pollution from coal power plants in China. MIT Sloan Working Paper.

Landrigan, P. J., Fuller, R., Acosta, N. J. R., Adeyi, O., Arnold, R., Baldé, A. B., et al. (2018). The Lancet Commission on pollution and health. The Lancet, 391(10119), 462–512.

Lin, C., Morck, R., Yeung, B., & Zhao, X. (2018). Anti-corruption reforms and shareholder valuations: Event study evidence from China. Journal of Financial Economics (in press).

Lins, K. V., Servaes, H., & Tamayo, A. (2017). Social capital, trust, and firm performance: The value of corporate social responsibility during the financial crisis. The Journal of Finance, 72(4), 1785–1824.

Lu, Y. (2011). Political connections and trade expansion. Economics of Transition, 19(2), 231–254.

Luo, J., Kaul, A., & Seo, H. (2018). Winning us with trifles: Adverse selection in the use of philanthropy as insurance. Strategic Management Journal, 39(10), 2591–2617.

Luo, X. R., Wang, D., & Zhang, J. (2017). Whose call to answer: Institutional complexity and firms’ CSR reporting. Academy of Management Journal, 60(1), 321–344.

Luo, X. R., Zhang, J., & Marquis, C. (2016). Mobilization in the internet age: Internet activism and corporate response. Academy of Management Journal, 59(6), 2045–2068.

Lys, T., Naughton, J. P., & Wang, C. (2015). Signaling through corporate accountability reporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 60(1), 56–72.

Ma, G., Rui, O. M., & Wu, Y. (2015). A springboard into politics: Do Chinese entrepreneurs benefit from joining the government-controlled business associations? China Economic Review, 36, 166–183.

Marquis, C., & Bird, Y. (2018). The paradox of responsive authoritarianism: How civic activism spurs environmental penalties in China. Organization Science, 29(5), 948–968.

Marquis, C., & Qian, C. (2014). Corporate social responsibility reporting in China: Symbol or substance? Organization Science, 25(1), 127–148.

Marquis, C., & Raynard, M. (2015). Institutional strategies in emerging markets. The Academy of Management Annals, 9(1), 291–335.

Marquis, C., Toffel, M. W., & Zhou, Y. (2016). Scrutiny, norms, and selective disclosure: A global study of greenwashing. Organization Science, 27(2), 483–504.

Marquis, C., Zhang, J., & Zhou, Y. (2011). Regulatory uncertainty and corporate responses to environmental protection in China. California Management Review, 54(1), 39–63.

Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340–363.

Mironov, M. (2015). Should one hire a corrupt CEO in a corrupt country? Journal of Financial Economics, 117, 29–42.

Nguyen, T. T., & Van Dijk, M. A. (2012). Corruption, growth, and governance: Private vs. state-owned firms in Vietnam. Journal of Banking & Finance, 36(11), 2935–2948.

Niehaus, P., & Sukhtankar, S. (2013). The marginal rate of corruption in public programs: Evidence from India. Journal of Public Economics, 104, 52–64.

Oliva, P. (2015). Environmental regulations and corruption: Automobile emissions in Mexico City. Journal of Political Economy, 123(3), 686–724.

Oliver, C. (1991). Strategic responses to institutional processes. Academy of Management Review, 16(1), 145–179.

Peng, M. W. (2003). Institutional transitions and strategic choices. Academy of Management Review, 28(2), 275–296.

Petersen, M. A. (2009). Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: Comparing approaches. Review of Financial Studies, 22(1), 435–480.

Sarkis, J., Gonzalez-Torre, P., & Adenso-Diaz, B. (2010). Stakeholder pressure and the adoption of environmental practices: The mediating effect of training. Journal of Operations Management, 28(2), 163–176.

Scott, W. R. (2005). Institutional theory: Contributing to a theoretical research program. Great Minds in Management: The Process of Theory Development, 37, 460–484.

Sharma, S., & Henriques, I. (2005). Stakeholder influences on sustainability practices in the Canadian forest products industry. Strategic Management Journal, 26(2), 159–180.

Shipman, J. E., Swanquist, Q. T., & Whited, R. L. (2017). Propensity score matching in accounting research. The Accounting Review, 92(1), 213–244.

Stathopoulou, E., & Varvarigos, D. (2014). Corruption, entry and pollution. Leicester working paper.

Surroca, J., Tribó, J. A., & Zahra, S. A. (2013). Stakeholder pressure on MNEs and the transfer of socially irresponsible practices to subsidiaries. Academy of Management Journal, 56(2), 549–572.

Wang, R., Wijen, F., & Heugens, P. P. (2018). Government’s green grip: Multifaceted state influence on corporate environmental actions in China. Strategic Management Journal, 39(2), 403–428.

Xu, C. (2011). The fundamental institutions of China’s reforms and development. Journal of Economic Literature, 49(4), 1076–1151.

Zeng, Y., Lee, E., & Zhang, J. (2016). Value relevance of alleged corporate bribery expenditures implied by accounting information. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 35(6), 592–608.

Zhang, J., Marquis, C., & Qiao, K. (2016). Do political connections buffer firms from or bind firms to the government? A study of corporate charitable donations of Chinese firms. Organization Science, 27(5), 1307–1324.

Zhao, H., & Lu, J. (2016). Contingent value of political capital in bank loan acquisition: Evidence from founder-controlled private enterprises in China. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(2), 153–174.

Zheng, W., Ni, N., & Crilly, D. (2019). Non-profit organizations as a nexus between government and business: Evidence from Chinese charities. Strategic Management Journal, 40(4), 658–684.

Acknowledgement

I thank the editor (Cory Searcy) and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. I am grateful to Thomas Riise Johansen and Thomas Plenborg for their comments on earlier versions of this paper, and I also appreciate the comments and suggestions from Hang Dong, Jesper Haga, Junqi Liu, Kim Pettersson, Thomas Poulsen, Carsten Rohde, Chaoyuan She, Tim Neerup Themsen, Zhifang Zhang, and participants of the European Accounting Association Annual Congress, the Nordic Accounting Conference, and the seminar at Copenhagen Business School. I would also thank the Research Center for Private Enterprises at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences for sharing the data. The usual disclaimers apply.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest related to this work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y. Greasing Dirty Machines: Evidence of Pollution-Driven Bribery in China. J Bus Ethics 170, 53–74 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04301-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04301-w