Abstract

In a sample of 522 police officers and staff in an English police force, we investigated the role of authoritarian leadership in reducing the levels of employee ethical voice (i.e., employees discussing and speaking out opinions against unethical issues in the workplace). Drawing upon uncertainty management theory, we found that authoritarian leadership was negatively related to employee ethical voice through increased levels of felt uncertainty, when the effects of a motivational-based mechanism suggested by previous studies were controlled. In addition, we found that the negative relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee ethical voice via felt uncertainty is mitigated by higher levels of benevolent leadership. That is, when authoritarian leaders simultaneously exhibit benevolence, they are less likely to cause feelings of uncertainty in their followers who are then more likely to speak up about unethical issues. We discuss theoretical and practical implications of the findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With a series of ethical scandals damaging trust in organizations and impairing the effectiveness of business functioning across the world (e.g., Price and Van der Walt 2013; Yandle 2010), researchers have emphasized the importance of promoting ethical conduct in organizations (e.g., Feldman et al. 2015; Hassan et al. 2014; Wright et al. 2016). An example of ethical conduct is ethical voice, which refers to employees discussing and speaking up about unethical issues in the workplace (Lee et al. 2017). Ethical voice has been viewed as a unique and important form of ethical conduct in organizations because it enables the identification and challenge of unethical issues before serious problems occur (Lee et al. 2017). Prior studies have identified the critical role that leaders serve in motivating followers to participate in ethical voice behavior (e.g., Huang and Paterson 2017; Lee et al. 2017).

Leaders in organizations are frequently expected to be decisive and safeguard team functioning to achieve results (Bass 1990; Yukl 2002). Prior research has shown that a controlling style of leadership (i.e., authoritarian leadership), which asserts absolute authority and control over followers (Farh and Cheng 2000), is effective for facilitating team performance under specific contexts (see a review by Harms et al. 2018; Huang et al. 2015). An authoritarian leadership style has been found to be widely applied in practice in various contexts including the military (Geddes et al. 2014), sport (Kellett 2002), and companies across Eastern and Western countries (Aycan 2006; Cheng et al. 2014; De Hoogh and Den Hartog 2009; De Hoogh et al. 2015; Farh and Cheng 2000). As noted earlier, employee ethical behavior has been identified as being essential for long-term organizational success (e.g., Feldman et al. 2015). Although the impact of positive leadership styles such as ethical leadership on employee ethical behavior is well-established (Huang and Paterson 2017), little is known about how a leader behaving in a rule-bound and demanding manner influences follower intentions to conduct ethical behavior. This gap is an important one to address as a leadership style which emphasizes compliance and achieving results may lead to employees feeling constrained from conducting ethical behaviors, especially when these behaviors are inherent with risks. Thus, the primary purpose of this study is to provide a framework to explain how and when authoritarian leadership influences employee ethical voice.

We draw upon uncertainty management theory (Lind and Van den Bos 2002; Van den Bos and Lind 2002) to explain how authoritarian leaders affect employee ethical voice. Uncertainty exists to the degree that situations are unpredictable or cannot be adequately understood (Van den Bos and Lind 2002). Although the original uncertainty management theory does not address the issue of the type of uncertainty being experienced, later studies reveal that uncertainty can be generated from the external environment (Waldman et al. 2001), from interpersonal relationships (Berger 1979; Berger and Gudykunst 1991), or from an individuals’ own status (De Cremer and Sedikides 2005). Of relevance to our focus of authoritarian leadership, we theorize uncertainty from an interpersonal perspective, which refers to an individual’s feelings of uncertainty due of a lack of information to be able to predict the attitudes and behaviors of another party within an interaction (Berger 1979; Berger and Calabrese 1975). We argue that because authoritarian leaders conceal their true intentions and provide little explanation for their decisions, followers will feel uncertain as to the consequences they may face from their leader if they engage in risk-inherent behaviors, such as ethical voice.

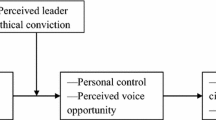

In addition, we examine a potential moderator of the relationship between authoritarian leadership and ethical voice via felt uncertainty. We focus on the moderating role of benevolent leadership, which is defined as leader behaviors that demonstrate individualized and holistic concern about employees’ personal and familial well-being beyond work relations (Farh and Cheng 2000). Past research has examined the interactive effect of authoritarian leadership and benevolent leadership and has found that the detrimental effect of authoritarian leadership on followers’ well-being and work performance is weakened if an authoritarian leader simultaneously exhibits high levels of benevolence (Chan et al. 2013; Farh et al. 2006; Tian and Sanchez 2017). This occurs due to the compensation effect that takes place when the leader exhibits benevolence towards followers, who will feel that their leader cares about their well-being and will also be encouraged to interpret the authoritarian leader’s behavior as well-intended (Chan et al. 2013). Following this line of research, we suggest that a higher level of benevolent leadership results in followers seeing authoritarian leaders as less threatening, which acts to alleviate the degree to which employees feel uncertain so that they become more prepared to conduct ethical voice behavior in the workplace. Figure 1 shows our research model.

This research makes several contributions to the literature. First, while the extant literature on ethical voice focuses on the positive role of ethical leaders (Huang and Paterson 2017; Lee et al. 2017), we develop and test a model that examines how authoritarian leadership affects follower ethical voice behavior. We add to the ethics literature by studying why there will be a negative impact on followers’ ethical behavior when leaders focus on personal power, employee obedience, and achievement of results. Second, prior studies of authoritarian leadership have focused on its impact on general work behaviors rather than its implications for workplace ethics. We are among the first to explore the role authoritarian leadership plays in influencing followers’ ethical behaviors (i.e., ethical voice). We develop an uncertainty-reduction perspective to illustrate the negative impact of authoritarian leadership on ethical voice. An uncertainty-reduction perspective has previously been used to explain the link between justice and employees’ general voice behavior (Takeuchi et al. 2012). Our study extends this literature by focusing on a leadership perspective and an ethics-oriented voice behavior. In this regard, we also add to the existing authoritarian leadership literature by theorizing and testing a new mechanism of felt uncertainty that helps to explain how and why authoritarian leadership exerts negative impacts on followers’ positive work behaviors. Furthermore, past research has mainly suggested that authoritarian leadership reduces followers’ discretionary efforts through a demotivational process by which authoritarian leaders imply the incompetence and powerlessness of followers (Chan et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2015). However, the authoritarian leadership—ethical voice relationship may not be fully captured by this demotivational process. While employees may not speak up due to feelings of incompetence and powerlessness, we consider it more likely that the main reason for their lack of voice behavior is the uncertainty they feel as to whether they may face sanctions from their leader. To test this, we examine whether the mediation effect of felt uncertainty provides stronger explanatory power than a motivational-based mechanism which is represented by work engagement. Finally, building on prior studies on paternalistic leadership (Chan et al. 2013; Farh et al. 2006), we extend the existing literature by demonstrating the joint effect of authoritarian and benevolent leadership on followers’ work behaviors from a new theoretical perspective, that of felt uncertainty. Since prior research on this joint effect was predominantly conducted in an Eastern context, this research also provides additional empirical support to the literature by using a Western sample in the United Kingdom.

Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

The Relationship Between Authoritarian Leadership and Ethical Voice

Voice is a type of discretionary behavior which seeks to improve work processes and policies (Van Dyne and LePine 1998). Scholars have suggested that there are distinct types of voice according to its content, namely, promotive voice and prohibitive voice (Liang et al. 2012). Promotive voice is framed as expressing new ideas or suggestions to improve organizational functioning, while prohibitive voice is framed as expressing concerns about harmful practices to prevent organizational failure. We suggest that ethical voice is prohibitive in nature due to its purpose of calling attention to existing or impending ethical issues and dilemmas. According to Liang et al. (2012, p. 75), voice with prohibitive content is efficient in identifying problematic issues and preventing crises in a timely manner. It is therefore of great importance for organizational functioning. Moreover, considering the nature of our sample in policing, concealing or not reporting wrongdoing in public sector organizations (e.g., police forces) has been found to severely harm the organization and wider communities. Prior research has shown that silence on ethical issues is associated with increased levels of violence and corruption in organizations (Rothwell and Baldwin 2007) and with decreased levels of public respect for law and regulation (Kleinig 1996). This evidence suggests that it is important for organizations to understand the importance of ethical voice and how it can be facilitated in the workplace.

Nevertheless, ethical voice is risky in nature because challenging “the way people behave” in the workplace may generate disagreement and confrontation with others, such as with coworkers. Prior studies have found that ethical leadership, which promotes ethical values and sets clear ethical standards for followers, plays a prominent role in engaging followers in ethical voice (Huang and Paterson 2017; Lee et al. 2016). However, in the extant literature little is known about how an authoritarian style of leadership will influence employee ethical voice. This is an intriguing question because recent studies argue that when authoritarian leaders centralize power to maximize performance, employees may strive to comply with high performance standards due to concerns of facing sanctions if they do not (De Hoogh et al. 2015; Wang and Guan 2018). Apart from this performance-oriented perspective, we know little about how leaders adopting centralized power and insisting on high standards influence employees’ intentions to conduct ethical behavior. To better understand this question, we apply uncertainty management theory and propose that authoritarian leadership causes followers to feel a high level of uncertainty when interacting with their leader which subsequently leads followers to withdraw from ethical voice behavior.

Authoritarian Leadership and Ethical Voice: The Mediating Role of Felt Uncertainty

Authoritarian leaders demand that their subordinates obey their instructions without questioning (Farh and Cheng 2000). They centralize decision-making around themselves and punish followers for disobedience of their instructions. The majority of the extant literature on authoritarian leadership has shown its detrimental effect on employees’ work attitudes, job performance, and extra-role behaviors (Chen et al. 2014; Cheng et al. 2002a, b; Wu et al. 2012). The main perspective to explain these negative impacts is that authoritarian leaders do not value followers’ input and do not put effort into harnessing followers’ self-worth. This demotivates followers and adversely affects their engagement in their work and their performance (e.g., Chan et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2011).

We propose that felt uncertainty is a particularly relevant mechanism to link authoritarian leadership to follower ethical voice behavior. In this study, we focus on the relational uncertainty that is generated when an individual perceives he or she is unable to predict their leader’s attitudes and responses within interactions (Berger 1979; Berger and Calabrese 1975). Individuals have normative expectations to be treated with dignity and respect from others and to receive explanations for decision outcomes (Bies and Moag 1986; Tyler and Bies 1990). In organizations, employees feel that it is a moral obligation for authority figures to show respect and explain their decisions in an interpersonally sensitive manner (Folger and Skarlicki 1999; Tyler and Bies 1990). Extending this perspective to a leadership context, effective communication has been identified as one of the most significant aspects of leadership which acts to decrease employees’ feeling of uncertainty and increase their willingness to engage in risk-taking behaviors such as voice (Carmeli et al. 2014; Chen and Hou 2016). For example, Takeuchi et al. (2012) argued that as leaders are often responsible for allocating rewards and enacting punishment, employees will refuse to speak up when they are uncertain how their leader will interpret and react to voice behavior.

As authoritarian leaders rely on a top-down style and make unilateral decisions, this leadership style highlights power asymmetry between the leader and the follower and reduces the quality of communication through the leader withholding important information (Cheng et al. 2004). Followers of authoritarian leaders are required to follow their leader’s instructions without question and are provided with low levels of explanation of the reasons or rationale for decisions made. Moreover, authoritarian leaders deliberately maintain distance and do not reveal their true intentions to followers (Farh and Cheng 2000). This generates a high level of uncertainty for followers in their ability to predict which behaviors will be welcomed by the leader and how they will react to proactive behavior by the follower. Furthermore, authoritarian leadership is related to exertion of high levels of control over followers and the use of punitive tactics to influence them. As the relationship with an authoritarian leader is beyond the follower’s ability to control, they will experience high levels of felt uncertainty. The interactional justice literature is closely aligned with these arguments in that it suggests that when leaders provide adequate explanations and treat followers with dignity and respect, followers are less likely to experience a sense of uncertainty or fear (Carter et al. 2014; Erkutlu and Chafra 2013). Prior research on authoritarian leadership has also provided support for this perspective. Specifically, authoritarian leadership has been shown to decrease followers’ perceptions of interpersonal justice (Aryee et al. 2007; Wu et al. 2012) and to result in followers experiencing higher levels of negative feelings such as fear and caution (Cheng et al. 2004).

Although we propose a positive relationship between authoritarian leadership and felt uncertainty, it could be argued that by sending clear signals to employees on how they should behave authoritarian leadership will reduce followers’ levels of felt uncertainty. However, we suggest that this will not be the case for the following reasons. Firstly, as noted earlier, felt uncertainty can be associated with both the external environment (Waldman et al. 2001) and with interpersonal interactions (Berger 1979; Berger and Gudykunst 1991). Prior research (Zhang and Xie 2017) has shown that while authoritarian leaders can reduce aspects of environmental uncertainty through communicating clear performance expectations, it acts to increase follower role conflict and ambiguity through the leader remaining unapproachable and not providing the follower with sufficient relevant information or support to meet these performance standards. In this sense, although authoritarian leaders utilize their hierarchical power to provide their followers with clarity on performance requirements for in-role tasks, followers working for an authoritarian leader will still feel high levels of uncertainty during interactions with them. As felt uncertainty in interpersonal interactions has previously been identified as an important factor in increasing employees’ concerns about whether to confront others (Kish-Gephart et al. 2009; Morrison 2011), followers will consider ethical voice behavior to be associated with high risks and will be reluctant to engage in this type of behavior. Furthermore, authoritarian leaders punish employee rule-breaking behavior and disobedience based on preferences and behavioral norms that they themselves decide (De Hoogh and Den Hartog 2009). Ryan and Oestreich (1998) noted that employees feel most uncertain about speaking up when their supervisors were “secretive” or “ambiguous.” In this regard, followers will be discouraged from taking the risk of conducting ethical voice behavior as they will be unable to judge whether this may offend their leader which would result in them being subjected to sanctions and punishment.

Hypothesis 1

Authoritarian leadership is positively related to felt uncertainty.

Further, we suggest that experiencing higher levels of felt uncertainty, as a result of interactions with an authoritarian leader, will lead to employees engaging less in ethical voice behavior. Felt uncertainty has been suggested as an important inhibitor of employee voice, due to higher levels of uncertainty increasing levels of perceived risk associated with voice behavior, resulting in employees being more likely to stay silent on subjects (Erkutlu and Chafra 2015; Gao et al. 2011; Takeuchi et al. 2012). Indeed, prior empirical research has found that felt uncertainty reduces employees’ levels of cooperative attitudes (Lind and Tyler 1988; Lind and Van den Bos 2002) and their levels of voice behavior (Takeuchi et al. 2012). In sum, we expect that authoritarian leadership increases the level of felt uncertainty for employees, and that this will result in them experiencing concern about potential risks and they will therefore be less prepared to engage in ethical voice behavior.

Finally, it is worth noting that it is conceptually different to theorize from a felt uncertainty perspective to explain how authoritarian leadership influences followers rather than from the demotivational process perspective adopted in previous studies (see for example Chan et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2015). A demotivational perspective argues that authoritarian leaders disregard followers’ input and require them to obey instructions completely. This results in the follower feeling incompetent in the workplace and makes them less likely to feel personally invested in their work and confident to voice their thoughts. In prior studies, work engagement has been used as a mediator to capture this process and show how leaders influence followers through generating feelings in the follower of the meaningfulness of their work and of feeling useful and worthwhile (Bono and Judge 2003; Tims et al. 2011). However, because ethical voice is prohibitive in nature and focuses on the presence of wrongdoing or harmful situations, a fair and safe communication context is a particularly important factor to ensure employees who conduct ethical voice are not penalized. The motivational mechanism of work engagement, which has a focus on whether employees do not engage in voice behavior due to a lack of confidence in their skills and knowledge, does not fully capture this view. In this sense, felt uncertainty will function differently to work engagement; when facing felt uncertainty, employees’ decisions to conduct voice depend on whether they have sufficient information about their leader to evaluate the inherent risks that may exist of them facing sanctions as a result of this behavior. Thus, we believe that felt uncertainty will effectively mediate the relationship between authoritarian leadership and voice, even when work engagement is accounted for.

Hypothesis 2

Felt uncertainty mediates the negative relationship between authoritarian leadership and ethical voice.

The Moderating Role of Leader Benevolence

Past research has found that authoritarian leadership can be associated with both high and low levels of benevolent leadership (Chan et al. 2013; Tian and Sanchez 2017). Empirical evidence has shown that benevolent leadership plays an important role in offsetting the negative impact of authoritarian leadership on followers’ job satisfaction (Farh et al. 2006), affective trust to the leader (Tian and Sanchez 2017), organizational-based self-esteem, job performance, and organizational citizenship behavior (Chan et al. 2013). Following this line of research, we propose that benevolent leadership is a key factor to offset the positive relationship between authoritarian leadership and felt uncertainty. We argue that benevolent leadership is important in this regard because leader benevolence, which focuses on showing consideration and facilitating work and non-work communication, helps followers to understand an authoritarian leader’s intentions and preferences (Chan et al. 2013; Tian and Sanchez 2017). In this situation, followers are less likely to experience felt uncertainty.

Leaders with high benevolence show consideration to their followers in both work and non-work domains (Farh and Cheng 2000). In the work domain, benevolent leaders coach followers, encourage them to ask for support, and help them to understand the workplace (Chan 2014; Zhang et al. 2015). In the non-work domain, benevolent leaders display individualized care to followers beyond the formal work relationship (Wang and Cheng 2010). In this situation, an authoritarian leader with high benevolence is more likely to share work information and to initiate personal communication with followers beyond the work relationship (Chan 2014). This will provide the follower with opportunities to communicate with their leader and reduce their level of felt uncertainty through gaining understanding of their leader’s preferences and intentions and of work-related information. Furthermore, benevolent leadership signals that although an authoritarian leader will punish disobedience, they will also provide fatherly like protection to the follower and have concern for the follower’s well-being (Cheng et al. 2004; Farh and Cheng 2000). When a follower perceives their leader as being more benevolent, their concerns regarding the possibility of facing severe sanctions will be reduced. This will lead to followers feel more willing to engage in ethical voice. In contrast, when leader benevolence is low, the follower will have less information on their leader’s intentions and preferences (Chan 2014), and will thus feel higher uncertainty due to concerns of the risk of facing severe sanctions from a leader who has little regard for their well-being and may punish them severely. In this situation, followers are more likely to feel high levels of uncertainty and thereby will be less likely to engage in ethical voice behavior. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3

The positive relationship between authoritarian leadership and felt uncertainty is moderated by benevolent leadership, such that the relationship is weaker when benevolent leadership is high rather than low.

Taken together, the above arguments predict a moderated mediation hypothesis, such that the level of benevolent leadership moderates the indirect effect of felt uncertainty linking the relationship between authoritarian leadership and ethical voice. We predict that when an authoritarian leader demonstrates a higher level of benevolence, this leader is less likely to cause high levels of felt uncertainty in followers, and thus stop them from raising ethical voice. Thus, we propose:

Hypothesis 4

Benevolent leadership moderates the indirect effect of authoritarian leadership on ethical voice via felt uncertainty, such that this indirect effect is weaker when benevolent leadership is high rather than low.

Method

Research Design

We examine the impact of authoritarian leadership on employee ethical voice in the context of policing. The survey was designed to focus at a dyadic level with no aggregation to the leader level. Data were collected from two sources. First, we asked respondents to rate their immediate supervisors’ levels of authoritarian leadership and benevolent leadership, and their own levels of felt uncertainty and work engagement. Second, we asked each respondent to provide a short coworker survey with a prepaid self-addressed sealed envelope to a colleague who had the opportunity to work closely with him/her. Each coworker was asked to evaluate the respondent’s level of ethical voice. Participants and their coworkers were asked to complete their surveys and post them back to the research team within a month. Coworkers have high daily interactions with the respondents and thus more opportunity to observe respondents’ voice behavior than other sources will have, such as supervisors (LePine and Van Dyne 1998). The validity of this approach to evaluating voice has been recognized and widely applied in previous studies (LePine and Van Dyne 1998, 2001; Liu et al. 2010).

An Overview of the Sample

Police forces have long been viewed as a type of organization that is authoritarian and militaristic in character (Dandeker 1992; Gordon et al. 2009). Prior research (Cowper 2000; Jermier and Berkes 1979; Shane 2010) has confirmed the prevalence of an authoritarian leadership style in policing. Moreover, in England and Wales, police officers and staff are expected to be aware of and comply with the principles and standards of professional behavior stated in the Policing Code of Ethics (College of Policing 2014). This professional code of conduct emphasizes the need to behave with honesty and integrity and that individuals should use ethical values to guide their judgements on how to behave and the decisions they make (College of Policing 2014, p. 5). Furthermore, the need for “challenging and reporting improper behavior” (p. 15) is specified as a behavioral standard for all police officers and staff. These standards suggest that raising ethical voice is advocated in policing. In sum, the current sample is appropriate for the investigation of the relationship between authoritarian leadership and followers’ ethical voice.

Sample and Procedure

We invited police officers and staff working in an English police force to participate in this study. All participants were informed that participation in the research was voluntary. The research team produced pencil and paper survey packs which were then sent to participants through the force’s internal postal system. Each pack consisted of a respondent questionnaire and a coworker questionnaire. First, we asked respondents to rate their supervisors’ levels of authoritarian leadership (and benevolent leadership), and their levels of felt uncertainty (and engagement) and return them to the research team using the prepaid, self-addressed envelopes provided. Evaluation of each respondent’s level of ethical voice was done by one of their coworkers. To achieve this we asked respondents to provide the separate short coworker survey and a second prepaid, self-addressed envelope that had been included in their survey pack to a colleague with whom they worked closely. To ensure confidentiality, each questionnaire was coded with a research-assigned identification number and all completed questionnaires were mailed directly back to the research team.

The final sample consisted of 522 employee responses (32.2%), each with a matched coworker response, reporting to 249 supervisors. The average number of respondents per supervisor was 2. The average tenure of respondents with their supervisors was 2.78 years,Footnote 1 51.8% were male, and 46.4% were police officers.

Measures

All items used a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree.

Employee-Rated

Authoritarian Leadership

We adapted from a 9-item subscale from the paternalistic leadership scale developed by Cheng et al. (2004) to measure authoritarian leadership. This scale has been widely used in a global context (e.g., Chen et al. 2014; Cheng et al. 2014; Schaubroeck et al. 2017). We adapted this scale and slightly modified the language to fix the context. Sample items are “my supervisor requires me to follow his/her instructions completely,” “my supervisor determines all decisions in the team whether they are important or not,” “my supervisor always has the last say in our team meetings,” and “my supervisor always behaves in a commanding fashion in front of employees.” The Cronbach’s alpha in this sample was .81.

Benevolent Leadership

Benevolent leadership was measured using an 11-item subscale from the same paternalistic leadership scale described above (Cheng et al. 2004). Sample items are “my supervisor takes very thoughtful care of subordinates who have spent a long time with him/her,” “my supervisor devotes all his/her energy to taking care of me,” and “beyond work relations, my supervisor expresses concern about my daily life.” The Cronbach’s alpha was .92.

Felt Uncertainty

To measure felt uncertainty, we adapted a six-item scale from McGregor et al.’s (2001) felt uncertainty scale. Sample items were “after interacting with my supervisor I often feel bothered,” “after interacting with my supervisor I often feel uncomfortable,” and “after interacting with my supervisor I often feel uneasy.” The Cronbach’s alpha of this scale was .98.

Coworker-Rated

Ethical Voice

Ethical voice was measured by four items referent-shifted from Tucker et al. (2008) safety voice measure. We modified the items and focused them on individuals raising concerns about the unethical issues in the workplace. Items included “She/he is prepared to talk to coworkers who fail to behave ethically,” “She/he would tell a coworker who is doing something unethical to stop,” and “She/he encourages her/his coworkers to act with integrity.” The Cronbach’s alpha of this scale was .93.

Control Variables

Past research suggests that demographic variables may influence employees’ work attitudes and behaviors (Van Knippenberg et al. 2005; Vandenberghe et al. 2007). We controlled for respondents’ gender (0 = male; 1 = female), job roles (0 = police officer; 1 = police staff), and tenure with supervisors (in years).

In addition, in order to demonstrate the unique mechanism of felt uncertainty explaining the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee ethical voice, we controlled for employees’ work engagement (Rich et al. 2010; Schaufeli et al. 2006) as an alternative mediator linking authoritarian leadership and ethical voice. This accounts for the potential influences from a motivational perspective of authoritarian leadership. Work engagement was measured using nine high loading items from Rich et al.’s (2010) job engagement scale. Sample items included “I am enthusiastic in my job” (emotional engagement), “at work I focus a great deal of attention on my job” (cognitive engagement), and “I try my hardest to perform well on my job” (physical engagement). The Cronbach’s alpha was .92.

Statistical Approach

Although our hypotheses focus on dyadic-level relationships, given that employees were nested within supervisory groups, we assessed the extent to which the data were non-independent by calculating intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC1) for the mediators and outcome variables. ICC1 values were .03 for felt uncertainty, .08 for work engagement, and .29 for ethical voice, indicating a lack of data independence in our data (ICC1 > .10, Bliese 2000). We followed prior research (Liu et al. 2015; Schaubroeck et al. 2017; Wu et al. 2016) and used “Cluster” and “TYPE = COMPLEX” commands in Mplus 8 (Muthén and Muthén 2012–2017) to examine our model. This approach corrects the potential bias in estimation that results from data non-independence due to individuals being clustered within units.

We specified a path model to test our hypotheses. To estimate the indirect and conditional indirect effects, we applied the Monte Carlo method and used 20,000 random draws from the estimated sampling distribution of the estimates to generate 95% bootstrapping confidence intervals for the indirect effects (Selig and Preacher 2008). The Monte Carlo method is recommended for multilevel models where lower-level mediation is predicted (Bauer et al. 2006), which is consistent with our hypothesized model. For the moderation analysis, before creating the interaction term, the independent variable and the moderator were grand-mean centered.

Results

Preliminary Statistics

Means, standard deviations, and the correlations among variables are shown in Table 1. As expected, authoritarian leadership was positively correlated with felt uncertainty (r = .37, p < .01) and felt uncertainty was negatively correlated with ethical voice (r = − .22, p < .01).

Before testing the hypotheses, we conducted a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs), to examine the validity of our measurement model. As shown in Table 2, the model fit indices of the five-factor model (authoritarian leadership, benevolent leadership, felt uncertainty, work engagement, and ethical voice) showed an acceptable fit (χ2 = 2458.86, df = 690, root mean square of approximation [RMSEA] = .07, comparative fit index [CFI] = .90, Tucker–Lewis Index [TLI] = .88, standardized root mean square residual [SRMR] = .08)Footnote 2 and was better than other alternative models examined. Although the hypothesis model has a relatively low TLI value, the observed items had significant loadings on their respective latent factors. We therefore conclude that these results supported the distinctiveness of the measurements used in this study.

Mediating Results

To test Hypotheses 1 and 2, we specified the indirect effects of felt uncertainty and work engagement linking authoritarian leadership with ethical voice in Mplus. We followed prior research (e.g., Wu et al. 2016) and allowed the disturbances of the two mediators which were assessed at the same time to be correlated in our model. In the first step, we first tested a full mediation model where we regressed ethical voice on felt uncertainty and work engagement and regressed the two mediators on authoritarian leadership. All demographics were used to predict the mediators and outcome. This model has a good fit to the data (χ2 = 0.03, df = 1, RMSEA = .00, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, SRMR = .002). We then tested a partial mediation model with a direct effect from authoritarian leadership to ethical voice included. Since this model is fully saturated with zero degree of freedom, we excluded the model fit indices. However, we found authoritarian leadership was not significantly related to ethical voice (B = − .01, n.s.). From this result, we concluded that felt uncertainty fully mediates the relationship between authoritarian leadership and ethical voice, and we hereafter report on findings from this full mediation model.

Table 3 summarizes the coefficients estimated in the mediation and moderated mediation models. We found that authoritarian leadership was positively related to felt uncertainty (Model 1a: B = .51, p < .001), supporting Hypothesis 1. We found that felt uncertainty was negatively related to ethical voice (Model 1c: B = − .21, p < .001). In terms of considering work engagement as an alternative mechanism linking authoritarian leadership and ethical voice, we did not find authoritarian leadership to be significantly related to work engagement (Model 1b: B = − .04, n.s.), and we found a positive relationship between work engagement and ethical voice (Model 1c: B = .18, p < .01).These results indicated that as we expected, authoritarian leadership influences the level of ethical voice via felt uncertainty rather than via work engagement.

To estimate the indirect effects, we used a bootstrapping procedure with 20,000 Monte Carlo replications (Selig and Preacher 2008). After controlling work engagement as an alternative mediator, bootstrapping results showed a significant negative indirect effect of authoritarian leadership on ethical voice via felt uncertainty, as indicated by the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) (effect size = − .11, 95% confidence intervals [− .18, − .03]),Footnote 3 which excluded 0. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

Moderation Results

In order to test Hypothesis 3, we introduced benevolent leadership as a moderator in the mediation model to predict felt uncertainty. The rest of the moderated mediation model was the same as in the mediation model described above. As shown in Table 3, the interaction term of authoritarian leadership and benevolent leadership was significantly related to felt uncertainty (B = − .10, p < .01). To assist with interpretation, the plot of the interaction effect is shown in Fig. 2. Consistent with our expectation, simple slope analyses showed that authoritarian leadership was more positively correlated with felt uncertainty when benevolent leadership was low (B = .61, p < .001) than when benevolent leadership was high (B = .35, p < .001), with a significant difference in the relationship magnitude (difference = .26, p <.001). Hypothesis 3 was thus supported.

Further, we examined the extent to which the overall mediation effect of felt uncertainty was conditionally influenced by the levels of benevolent leadership. We followed Edwards and Lambert (2007) method, which has been widely used in later studies (Grant et al. 2011; Panaccio et al. 2014), to test the difference of the conditional indirect effects under low and high levels of a moderator. As expected, the indirect, negative effect of authoritarian leadership on ethical voice through felt uncertainty was stronger when benevolent leadership was low (effect size = − .12, 95% CIs [− .13, − .008]) than when benevolent leadership was high (effect size = − .08, 95% CIs [− .06, − .002]), with a significant different estimate (difference = − .04, 95% CIs [− .08, − .004]). Therefore, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

Discussion

The purpose of this paper is to first investigate the impact of authoritarian leadership on employee ethical voice and its underlying mechanism, and second to explore a boundary condition of this relationship. By proposing a moderated mediation model, we found support for our hypotheses in which the impact of authoritarian leadership on ethical voice was mediated by subordinates’ felt uncertainty. We also found that the positive impact of authoritarian leadership on felt uncertainty was buffered by benevolent leadership. The mediation effect of felt uncertainty from authoritarian leadership to ethical voice was weaker when the level of benevolent leadership was higher.

Theoretical Implications

This study has several theoretical implications. First, this research enriches the theoretical and empirical foundation of the voice literature. In particular, though growing evidence has demonstrated the role of positive leaders (i.e., ethical leaders) in facilitating employee ethical voice, limited studies have considered how controlling leaders influence followers’ intentions towards raising conducting ethical voice. Drawing upon uncertainty management theory (Lind and Van den Bos 2002; Van den Bos and Lind 2002), our work explores why and when followers’ levels of ethical voice are harmed by an authoritarian style of leadership. Uncertainty management theory emphasizes that individuals rely on external referents, such as leaders, to get relevant information about how they will be treated in response to their behavior. Our results suggest that authoritarian leaders, who use their positional power to make decisions and share little information with followers, generate feelings of uncertainty in their followers, which then inhibit followers from conducting ethical voice behavior. Thus, examining these impacts of authoritarian leadership extends our current understanding of the relationship between leadership styles and follower ethical voice.

Second, existing research on authoritarian leadership has called for future studies to include more theoretically relevant outcomes and mediators to depict a complete picture of this leadership style (Chen et al. 2014; De Hoogh et al. 2015; Gao et al. 2011). Our research contributes to the authoritarian leadership literature from two perspectives. First, the development of an uncertainty perspective offers an additional theoretical lens to illustrate the negative impacts of authoritarian leadership on employees. Past research has theorized and examined authoritarian leadership from a motivational perspective, suggesting that authoritarian leadership behaviors harm employees’ motivations towards their work and to engage in discretionary effort (Chan et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2011). Our research suggests an alternative perspective of uncertainty, which is shown to better explain why authoritarian leadership constrains followers’ intentions to take risks and engage in ethical voice. Second, by including ethical voice as an outcome of authoritarian leadership, we provide insights for the impact of authoritarian leadership from an ethics perspective. The impact of authoritarian leadership on ethics-related outcomes has rarely been examined in the authoritarian leadership literature. We encourage future studies to examine the relationship between authoritarian leadership and additional ethics-related outcomes.

Third, our findings provide additional evidence of the joint effect of authoritarian and benevolent leadership on employees’ work attitudes and behaviors. Authoritarian leadership and benevolent leadership have been theorized as two main components of paternalistic leadership (Aycan et al. 2013; Farh and Cheng 2000). Recent research has attempted to understand the interplay of leader authoritarian and benevolent leadership by examining their interaction effects, and found that the negative impacts of authoritarian leadership on employee outcomes are weaker when leaders exhibited higher benevolent leadership (Chan et al. 2013; Farh et al. 2006). This study adds to this line of literature by replicating the compensation effect of benevolent leadership using a different mediator of felt uncertainty and a novel outcome of ethical voice and shows that the compensating effect indeed exists. This research provides further evidence of the importance of taking into consideration the role of benevolent leadership when investigating the impacts of leader authoritarianism.

Finally, research regarding the interaction between authoritarian leadership and benevolent leadership (i.e., paternalistic leadership: Farh and Cheng 2000) has been conducted predominantly in an Eastern context (Chen et al. 2018; Pellegrini et al. 2010) and the research in a Western context is limited (see De Hoogh and Den Hartog 2009; De Hoogh et al. 2015 for exceptions). Through our testing of the predictive power of authoritarian leadership on employee ethical voice in a sample from the United Kingdom, our results indicate the comparability and applicability of authoritarian leadership in a Western context. The results of this research provide additional evidence for this joint leadership style and offer further insights to understand its effects associated with employee outcomes. Furthermore, our study meets the research calls from Zhang et al. (2015) and Li and Sun (2015) for studies in Western samples of authoritarian leadership on employee voice behavior.

Practical Implication

Our findings provide important practical implications for managers. Organizations should be aware that authoritarian leaders who exert personal dominance over and maintain distance from employees will increase feelings of uncertainty in their followers, which will reduce their preparedness to speak up and make effective suggestions on issues. Prior research has found that authoritarian leadership can benefit individual job performance, or group performance, under certain specific conditions, such as when employees have higher levels of power distance orientation (Wang and Guan 2018) or when companies are under harsh economic conditions (Huang et al. 2015). However, when it comes to facilitation of employees’ discretionary efforts, such as that of ethical voice in this case, authoritarian leadership hinders employees’ willingness to exert discretionary effort and engage in extra-mile behavior. Therefore, dependent on the types of behaviors organizations want to encourage, particular attention is required with regard to selection of supervisors and managers and to the occurrence of the adoption of an authoritarian leadership style by managers and supervisors within the organization.

In addition, our findings clearly suggest that when authoritarian leaders show high levels of benevolent leadership, their subordinates experience less felt uncertainty, which then results in a smaller reduction in ethical voice. As a result of this finding, we advocate that supervisors and managers show benevolent concern and provide guidance to their employees. Indeed, we find that higher benevolent leadership is associated with reduced employee felt uncertainty, and higher levels of ethical voice, compared to when benevolence is low (Table 1: r = − .52, p < .01, for felt uncertainty; r = .27, p < .01, for ethical voice). In sum, in situations where leaders need to behave in an authoritarian manner, such as when they need to achieve short-term goals when resources such as time are limited, if leaders can also show benevolence, they can lessen the suppressing effects of authoritarianism on employee ethical voice.

Limitation and Future Research

There are several limitations in this study. First, although we collected the outcome variable of ethical voice from a different source (i.e., coworker), the study is cross-sectional since the other variables were collected at the same time. Therefore, we cannot rule out common-method variance (CMV) in our study (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Furthermore, future studies would benefit from longitudinal or experimental research designs to investigate the causal directions among proposed variables. In addition, this study focuses on ethical voice ethical voice targeted at speaking up to coworkers. Future research is encouraged to measure voice targeted at different sources (e.g., supervisors and other out-group individuals) to depict a full picture of how authoritarian leadership and felt uncertainty influence followers’ intention to voice ethical concerns. In addition, as we did not control for the quality of the relationship between the participant and the coworker this may have resulted in bias in the ratings of voice behavior. While we note that bias may be present, we argue that this bias should have occurred uniformly across the sample and as suggested by prior scholars (Ostroff et al. 2002; Spector and Brannick 1995) and as such, although it may affect the intercept of our model it should not confound our hypotheses testing. Nevertheless, we suggest that to reduce bias in ratings, future research should control for interpersonal liking (Liden and Maslyn 1998) when using coworker ratings of voice.

Second, we argued from an uncertainty management perspective that felt uncertainty is an important mechanism underlying the relationship between authoritarian leadership and ethical voice. Although we take account for the potential impact of work engagement, other potential mediators should be taken into consideration. Past research has suggested that authoritarian leaders who impost strict control over employees are viewed as fear-inspiring (Farh and Cheng 2000). Therefore, emotion-related mechanisms such as fear (Farh et al. 2006), or stress-related mechanisms, such as emotional exhaustion (Maslach and Jackson 1981) or resource-depletion (Vohs and Heatherton 2000), can be considered in future research. In addition to alternative mediators, prior research has found that the negative impact of authoritarian leadership is weaker if followers endorse high levels of power distance orientation (e.g., Schaubroeck et al. 2017). A limitation of this study is that we did not control for power distance. It may be that followers with a higher power distance may view authoritarian leadership as more acceptable and thus would feel less uncertainty and hence would be more likely to engage in ethical voice behavior. The impact of power distance and other possible moderators of the relationship between authoritarian leadership and felt uncertainty could also be examined in future research.

Finally, it should be noted that the samples in this study were from policing. Policing organizations are relatively hierarchical in rank and it is likely that authoritarianism may be more tolerated by policing employees. Future research may also examine the external validity of our findings in different organizational settings. For example, it would be interesting to examine whether authoritarian leadership is less tolerated and causes even more negative employee outcomes in private service firms.

To conclude, the prevalence of the existence of authoritarian leadership in various organizations and across multiple cultures has drawn attention to this style of leadership from scholars. This study provides new insights on the impact of authoritarian leadership on employee ethical voice. Authoritarian leadership is positively related to employee felt uncertainty, which in turn decreases their levels of ethical voice. This study also contributes to the literature by confirming the compensating role of benevolent leadership on the negative impact of authoritarian leadership on subordinates. Taken together, the present study offers interesting insights into why and when employee ethical voice tends to be decreased by authoritarian leadership.

Notes

We were not allowed to collect other personal data, such as age, due to confidentiality concerns raised by force personnel.

The original model fit was (χ2 = 2927.21, df = 692, RMSEA = .08, CFI = .86, TLI = .85, SRMR = .08). Following the model modification index, we correlated disturbances between two pairs of items which had modification values over 100. These two pairs were “after interacting with my supervisor I often feel uneasy (felt uncertainty)” and “after interacting with my supervisor I often feel uncomfortable (felt uncertainty),” and “I feel positive about my job (engagement)” and “I feel energetic at my job (engagement).” Hystad et al. (2010) argued that error correlation between item pairs is justifiable when there is perceived redundancy in item content. Following this, we argue that correlating the two item pairs mentioned above is justifiable because each pair was similar in content.

We also excluded work engagement as a mediator and repeated all mediation analysis. We found that the results remained largely unchanged: authoritarian leadership was positively related to felt uncertainty (B = .52, p < .001), felt uncertainty was negatively related to ethical voice (B = − .23, p < .001), and the indirect effect of felt uncertainty was significant (indirect effect = − .12, 95% confidence intervals [− .19, − .06]).

References

Aryee, S., Chen, Z. X., Sun, L. Y., & Debrah, Y. A. (2007). Antecedents and outcomes of abusive supervision: Test of a trickle-down model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 191–201.

Aycan, Z. (2006). Paternalism: Towards conceptual refinement and operationalization. In K. S. Yang, K. K. Hwang, & U. Kim (Eds.), Indigenous and cultural psychology: Understanding people in context (pp. 445–466). New York: Springer.

Aycan, Z., Schyns, B., Sun, J. M., Felfe, J., & Saher, N. (2013). Convergence and divergence of paternalistic leadership: A cross-cultural investigation of prototypes. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(9), 962–969.

Bass, B. M. (1990). Stogdill’s handbook of leadership. New York: Free Press.

Bauer, D. J., Preacher, K. J., & Gil, K. M. (2006). Conceptualizing and testing random indirect effects and moderated mediation in multilevel models: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 11(2), 142–163.

Berger, C. R. (1979). Beyond initial interaction: Uncertainty, understanding, and the development of interpersonal relationships. In H. Giles & R. S. Clair (Eds.), Language and social psychology (pp. 122–144). Baltimore, MD: University Park Press.

Berger, C. R., & Calabrese, R. J. (1975). Some explorations in initial interaction and beyond: Toward a developmental theory of interpersonal communication. Human Communication Research, 1(2), 99–112.

Berger, C. R., & Gudykunst, W. B. (1991). Uncertainty and communication. In B. Dervin & M. J. Voight (Eds.), Progress in communication sciences (Vol. 10, pp. 21–66). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Bies, R. J., & Moag, J. S. (1986). Interactional communication criteria of fairness. In R. J. Lewicki, B. H. Sheppard, & M. H. Bazerman (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (pp. 289–319). Greenwich, CT: JAI.

Bliese, P. D. (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In K. J. Klein & S. W. J. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multi-level theory, research and methods in organizations: foundations, extensions, and new directions (pp. 349–381). San Francisco, CA: JoKsey-Bass.

Bono, J. E., & Judge, T. A. (2003). Self-concordance at work: Toward understanding the motivational effects of transformational leaders. Academy of Management Journal, 46(5), 554–571.

Carmeli, A., Sheaffer, Z., Binyamin, G., Reiter-Palmon, R., & Shimoni, T. (2014). Transformational leadership and creative problem-solving: The mediating role of psychological safety and reflexivity. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 48(2), 115–135.

Carter, M. Z., Mossholder, K. W., Feild, H. S., & Armenakis, A. A. (2014). Transformational leadership, interactional justice, and organizational citizenship behavior: The effects of racial and gender dissimilarity between supervisors and subordinates. Group & Organization Management, 39(6), 691–719.

Chan, S. C. (2014). Paternalistic leadership and employee voice: Does information sharing matter? Human Relations, 67(6), 667–693.

Chan, S. C., Huang, X., Snape, E., & Lam, C. K. (2013). The Janus face of paternalistic leaders: Authoritarianism, benevolence, subordinates’ organization-based self-esteem, and performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(1), 108–128.

Chen, A. S. Y., & Hou, Y. H. (2016). The effects of ethical leadership, voice behavior and climates for innovation on creativity: A moderated mediation examination. The Leadership Quarterly, 27(1), 1–13.

Chen, X. P., Eberly, M. B., Chiang, T. J., Farh, J. L., & Cheng, B. S. (2014). Affective trust in Chinese leaders linking paternalistic leadership to employee performance. Journal of Management, 40(3), 796–819.

Chen, Y., Zhou, X., & Klyver, K. (2018). Collective efficacy: Linking paternalistic leadership to organizational commitment. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3847-9.

Cheng, B. S., Huang, M. P., & Chou, L. F. (2002a). Paternalistic leadership and its effectiveness: Evidence from Chinese organizational teams. Journal of Psychology in Chinese Societies, 3(1), 85–112.

Cheng, B. S., Shieh, P. Y., & Chou, L. F. (2002b). The principal’s leadership, leader-member exchange quality, and the teacher’s extra-role behavior: The effects of transformational and paternalistic leadership. Indigenous Psychological Research in Chinese Societies, 17, 105–161.

Cheng, B. S., Chou, L. F., Wu, T. Y., Huang, M. P., & Farh, J. L. (2004). Paternalistic leadership and subordinate responses: Establishing a leadership model in Chinese organizations. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 7(1), 89–117.

Cheng, B. S., Boer, D., Chou, L. F., Huang, M. P., Yoneyama, S., Shim, D., et al. (2014). Paternalistic leadership in four East Asian societies generalizability and cultural differences of the triad model. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45(1), 82–90.

College of Policing. (2014). Code of ethics: A code of practice for the principles and standards of professional behaviour for the policing profession of England and Wales. Coventry: College of Policing. Available at: https://www.college.police.uk/What-we-do/Ethics/Documents/Code_of_Ethics.pdf.

Cowper, T. J. (2000). The myth of the “military model” of leadership in law enforcement. Police Quarterly, 3(3), 228–246.

Dandeker, C. (1992). Surveillance, power and modernity: Bureaucracy and discipline from 1700 to the present day. Cambridge: Polity Press.

De Cremer, D., & Sedikides, C. (2005). Self-uncertainty and responsiveness to procedural justice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41(2), 157–173.

De Hoogh, A. H., & Den Hartog, D. N. (2009). Neuroticism and locus of control as moderators of the relationships of charismatic and autocratic leadership with burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(4), 1058–1067.

De Hoogh, A. H., Greer, L. L., & Den Hartog, D. N. (2015). Diabolical dictators or capable commanders? An investigation of the differential effects of autocratic leadership on team performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(5), 687–701.

Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological methods, 12(1), 1–22.

Erkutlu, H., & Chafra, J. (2013). Effects of trust and psychological contract violation on authentic leadership and organizational deviance. Management Research Review, 36(9), 828–848.

Erkutlu, H., & Chafra, J. (2015). The mediating roles of psychological safety and employee voice on the relationship between conflict management styles and organizational identification. American Journal of Business, 30(1), 72–91.

Farh, J. L., & Cheng, B. S. (2000). A cultural analysis of paternalistic leadership in Chinese organizations. In J. T. Li, A. S. Tsui, & E. Weldon (Eds.), Management and organizations in the Chinese context (pp. 84–127). London: Macmillan.

Farh, J. L., Cheng, B. S., Chou, L. F., & Chu, X. P. (2006). Authority and benevolence: Employees’ responses to paternalistic leadership in China. In A. S. Tsui, Y. J. Bian, & L. Cheng (Eds.), China’s domestic private firms: Multidisciplinary perspectives on management and performance (pp. 230–260). New York: Sharpe.

Feldman, G., Chao, M. M., Farh, J. L., & Bardi, A. (2015). The motivation and inhibition of breaking the rules: Personal values structures predict unethicality. Journal of Research in Personality, 59, 69–80.

Folger, R., & Skarlicki, D. P. (1999). Unfairness and resistance to change: Hardship as mistreatment. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 12(1), 35–50.

Gao, L., Janssen, O., & Shi, K. (2011). Leader trust and employee voice: The moderating role of empowering leader behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(4), 787–798.

Geddes, B., Frantz, E., & Wright, J. G. (2014). Military rule. Annual Review of Political Science, 17, 147–162.

Gordon, R., Clegg, S., & Kornberger, M. (2009). Embedded ethics: Discourse and power in the New South Wales police service. Organization Studies, 30(1), 73–99.

Grant, A. M., Gino, F., & Hofmann, D. A. (2011). Reversing the extraverted leadership advantage: The role of employee proactivity. Academy of Management Journal, 54(3), 528–550.

Harms, P., Wood, D., Landay, K., Lester, P. B., & Lester, G. V. (2018). Autocratic leaders and authoritarian followers revisited: A review and agenda for the future. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(1), 105–122.

Hassan, S., Wright, B. E., & Yukl, G. (2014). Does ethical leadership matter in government? Effects on organizational commitment, absenteeism, and willingness to report ethical problems. Public Administration Review, 74(3), 333–343.

Huang, L., & Paterson, T. A. (2017). Group ethical voice: Influence of ethical leadership and impact on ethical performance. Journal of Management, 43(4), 1157–1184.

Huang, X., Xu, E., Chiu, W., Lam, C., & Farh, J. L. (2015). When authoritarian leaders outperform transformational leaders: Firm performance in a harsh economic environment. Academy of Management Discoveries, 1(2), 180–200.

Hystad, S. W., Eid, J., Johnsen, B. H., Laberg, J. C., & Thomas Bartone, P. (2010). Psychometric properties of the revised Norwegian dispositional resilience (hardiness) scale. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 51(3), 237–245.

Jermier, J. M., & Berkes, L. J. (1979). Leader behavior in a police command bureaucracy: A closer look at the quasi-military model. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24, 1–23.

Kellett, P. (2002). Football-as-war, coach-as-general: Analogy, metaphor and management implications. Football Studies, 5(1), 60–76.

Kish-Gephart, J. J., Detert, J. R., Treviño, L. K., & Edmondson, A. C. (2009). Silenced by fear: The nature, sources, and consequences of fear at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 29, 163–193.

Kleinig, J. (1996). The ethics of policing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lee, D., Choi, Y., Youn, S., & Chun, J. U. (2017). Ethical leadership and employee moral voice: The mediating role of moral efficacy and the moderating role of leader–follower value congruence. Journal of Business Ethics, 141(1), 47–57.

Lee, K., Kim, E., Bhave, D. P., & Duffy, M. K. (2016). Why victims of undermining at work become perpetrators of undermining: An integrative model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(6), 915.

LePine, J. A., & Van Dyne, L. (1998). Predicting voice behavior in work groups. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(6), 853–868.

LePine, J. A., & Van Dyne, L. (2001). Voice and cooperative behavior as contrasting forms of contextual performance: Evidence of differential relationships with big five personality characteristics and cognitive ability. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(2), 326–336.

Li, Y., & Sun, J. M. (2015). Traditional Chinese leadership and employee voice behavior: A cross-level examination. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(2), 172–189.

Liang, J., Farh, C. I., & Farh, J. L. (2012). Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave examination. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 71–92.

Liden, R. C., & Maslyn, J. M. (1998). Multidimensionality of leader-member exchange: An empirical assessment through scale development. Journal of Management, 24(1), 43–72.

Lind, E. A., & Tyler, T. R. (1988). The social psychology of procedural justice. New York: Plenum.

Lind, E. A., & Van den Bos, K. (2002). When fairness works: Toward a general theory of uncertainty management. Research in Organizational Behavior, 24, 181–223.

Liu, W., Zhu, R., & Yang, Y. (2010). I warn you because I like you: Voice behavior, employee identifications, and transformational leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(1), 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.10.014.

Liu, Y., Wang, M., Chang, C. H., Shi, J., Zhou, L., & Shao, R. (2015). Work–family conflict, emotional exhaustion, and displaced aggression toward others: The moderating roles of workplace interpersonal conflict and perceived managerial family support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(3), 793–808.

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113.

McGregor, I., Zanna, M. P., Holmes, J. G., & Spencer, S. J. (2001). Compensatory conviction in the face of personal uncertainty: Going to extremes and being oneself. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(3), 472–488.

Morrison, E. W. (2011). Employee voice behavior: Integration and directions for future research. Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 373–412.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2012–2017). Mplus: Statistical analysis with latent variables: User’s guide. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Ostroff, C., Kinicki, A. J., & Clark, M. A. (2002). Substantive and operational issues of response bias across levels of analysis: an example of climate-satisfaction relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(2), 355–368.

Panaccio, A., Vandenberghe, C., & Ben Ayed, A. K. (2014). The role of negative affectivity in the relationships between pay satisfaction, affective and continuance commitment and voluntary turnover: A moderated mediation model. Human Relations, 67(7), 821–848.

Pellegrini, E. K., Scandura, T. A., & Jayaraman, V. (2010). Cross-cultural generalizability of paternalistic leadership: An expansion of leader-member exchange theory. Group & Organization Management, 35(4), 391–420.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Price, G., & Van der Walt, A. J. (2013). Changes in attitudes towards business ethics held by former South African business management students. Journal of Business Ethics, 113(3), 429–440.

Rich, B. L., Lepine, J. A., & Crawford, E. R. (2010). Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 53(3), 617–635.

Rothwell, G. R., & Baldwin, J. N. (2007). Ethical climate theory, whistle-blowing, and the code of silence in police agencies in the state of Georgia. Journal of Business Ethics, 70(4), 341–361.

Ryan, K. D., & Oestreich, D. K. (1998). Driving fear out of the workplace: Creating the high-trust, high-performance organization. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Schaubroeck, J. M., Shen, Y., & Chong, S. (2017). A dual-stage moderated mediation model linking authoritarian leadership to follower outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(2), 203–214.

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701–716.

Selig, J. P., & Preacher, K. J. (2008). Monte Carlo method for assessing mediation: An interactive tool for creating confidence intervals for indirect effects [Computer software].

Shane, J. M. (2010). Performance management in police agencies: A conceptual framework. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 33(1), 6–29.

Spector, P. E., & Brannick, M. T. (1995). The nature and effects of method variance in organizational research. In C. L. Cooper & I. T. Robertson (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 249–274). New York: Wiley.

Takeuchi, R., Chen, Z., & Cheung, S. Y. (2012). Applying uncertainty management theory to employee voice behavior: An integrative investigation. Personnel Psychology, 65(2), 283–323.

Tian, Q., & Sanchez, J. I. (2017). Does paternalistic leadership promote innovative behavior? The interaction between authoritarianism and benevolence. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 47(5), 235–246.

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2011). Do transformational leaders enhance their followers’ daily work engagement? The Leadership Quarterly, 22(1), 121–131.

Tucker, S., Chmiel, N., Turner, N., Hershcovis, M. S., & Stride, C. B. (2008). Perceived organizational support for safety and employee safety voice: The mediating role of coworker support for safety. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 13(4), 319–330. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.13.4.319.

Tyler, T. R., & Bies, R. J. (1990). Beyond formal procedures: The interpersonal context of procedural justice. In J. S. Carroll (Ed.), Applied social psychology and organizational settings (pp. 77–98). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Van den Bos, K., & Lind, E. A. (2002). Uncertainty management by means of fairness judgments. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 34, pp. 1–60). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Van Dyne, L., & LePine, J. A. (1998). Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Academy of Management Journal, 41(1), 108–119.

Van Knippenberg, B., Van Knippenberg, D., De Cremer, D., & Hogg, M. A. (2005). Research in leadership, self, and identity: A sample of the present and a glimpse of the future. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(4), 495–499.

Vandenberghe, C., Bentein, K., Michon, R., Chebat, J.-C., Tremblay, M., & Fils, J.-F. (2007). An examination of the role of perceived support and employee commitment in employee-customer encounters. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 1177–1187.

Vohs, K. D., & Heatherton, T. F. (2000). Self-regulatory failure: A resource-depletion approach. Psychological Science, 11(3), 249–254.

Waldman, D. A., Ramirez, G. G., House, R. J., & Puranam, P. (2001). Does leadership matter? CEO leadership attributes and profitability under conditions of perceived environmental uncertainty. Academy of Management Journal, 44(1), 134–143.

Wang, A. C., & Cheng, B. S. (2010). When does benevolent leadership lead to creativity? The moderating role of creative role identity and job autonomy. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(1), 106–121.

Wang, H., & Guan, B. (2018). The positive effect of authoritarian leadership on employee performance: The moderating role of power distance. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 357.

Wright, B. E., Hassan, S., & Park, J. (2016). Does a public service ethic encourage ethical behaviour? Public service motivation, ethical leadership and the willingness to report ethical problems. Public Administration, 94(3), 647–663.

Wu, C. H., Liu, J., Kwan, H. K., & Lee, C. (2016). Why and when workplace ostracism inhibits organizational citizenship behaviors: An organizational identification perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(3), 362–378.

Wu, M., Huang, X., Li, C., & Liu, W. (2012). Perceived interactional justice and trust-in-supervisor as mediators for paternalistic leadership. Management and Organization Review, 8(1), 97–121.

Yandle, B. (2010). Lost trust: The real cause of the financial meltdown. The Independent Review, 14(3), 341–361.

Yukl, G. A. (2002). Leadership in organizations. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Zhang, A. Y., Tsui, A. S., & Wang, D. X. (2011). Leadership behaviors and group creativity in Chinese organizations: The role of group processes. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(5), 851–862.

Zhang, Y., Huai, M., & Xie, Y. (2015). Paternalistic leadership and employee voice in China: A dual process model. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(1), 25–36.

Zhang, Y., & Xie, Y. H. (2017). Authoritarian leadership and extra-role behaviors: A role-perception perspective. Management and Organization Review, 13(1), 147–166.

Acknowledgements

We would like to sincerely thank Marisa Plater (Durham University) and Natalie Brown (Durham University) for their effort on data collection and kind support of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, Y., Graham, L., Farh, JL. et al. The Impact of Authoritarian Leadership on Ethical Voice: A Moderated Mediation Model of Felt Uncertainty and Leader Benevolence. J Bus Ethics 170, 133–146 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04261-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04261-1