Abstract

According to social learning theory, we explored the relation between ethical leadership and knowledge hiding. We developed a moderated mediation model of the psychological safety linking ethical leadership and knowledge hiding. Surveying 436 employees in 78 teams, we found that ethical leadership was negatively related to knowledge hiding, and that this relation was mediated by psychological safety. We further found that the effect of ethical leadership on knowledge hiding was contingent on a mastery climate. Finally, theoretical and practical implications were discussed for leadership and knowledge management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the years, leadership researchers have studied ethical leadership intensively (Ng and Feldman 2015). A number of empirical studies have examined its positive effects on employee and organizational outcomes (Ng and Feldman 2015). For example, ethical leadership has been shown to be positively associated with favorable outcomes, such as organizational citizenship behavior (Kacmar et al. 2011; Mo and Shi 2017), job satisfaction (Avey et al. 2012), voice behavior (Lee et al. 2017), group learning behavior (Walumbwa et al. 2017), and performance (Hung and Paterson 2017; Treviño et al. 2015; Walumbwa et al. 2012). Also, research has shown a negative relation between ethical leadership and turnover intention (Demirtas and Akdogan 2015), and organizational deviance (van Gils et al. 2015).

While there exists an abundance of studies examining the relation between ethical leadership and employee ethical behaviors and deviant conduct, the research examining the relation between ethical leadership and knowledge management is fragmented (Tang et al. 2015). However, a preponderance of knowledge management research has examined the contextual factors that might enhance or impede knowledge sharing (e.g., Lee et al. 2018), while what contributes to knowledge hiding or what reduces knowledge hiding begs for more research. Knowledge hiding is common among workers. For example, a newspaper poll of 1700 readers by The Globe and Mail showed that 76% of employees hid knowledge from their coworkers, and most viewed knowledge as privacy (The Globe and Mail 2006). In China, a survey showed that 46% of respondents have ever hidden knowledge at work (Peng 2013). Moreover, according to Babcock (2004), the loss of knowledge hiding is US $31.5 billion a year for Fortune 500 companies. Given the enormous loss resulting from knowledge hiding, it would be necessary to understand how ethical leadership affects employees’ knowledge hiding behaviors. Ethical leadership, which stresses the criticality of ethical behaviors, is well suitable for explaining unethical behaviors in work units (e.g., Mayer et al. 2012; Ng and Feldman 2015). Specifically, ethical leaders can actively help subordinates to shape their values by being moral role models, utilizing contingent punishments and rewards to prompt higher level of ethical standards, communicating important ethical values to subordinates, and treating subordinates with concern and care (Brown and Treviño 2006). According to Serenko and Bontisin (2016), most of the employees view knowledge hiding as generally unethical, unhealthy, and harmful to both employees and organizations. Moreover, in a highly ethical work environment, knowledge hiding is likely to be considered inappropriate (Serenko and Bontisin (2016). Thus, examining how ethical leadership affects knowledge hiding is of significant research interest.

While the relation between ethical leadership and knowledge hiding has received little research attention, research about the intervening mechanisms through which ethical leadership associates with knowledge hiding is even scarcer (e.g., Tang et al. 2015). The only exception is a study by Tang et al. (2015), which explored the influence of ethical leadership on knowledge hiding, as well as its intervening mechanism. However, they did not examine the boundary conditions and used full-time students in laboratory settings instead of employees in real work contexts. According to Shin (2014), tasks used in laboratory settings may not engage enough to elicit negative or positive affective reactions, and thus, they may not be effective in examining complicated affective processes that result in unethical behavior. Also, teams temporarily constructed in a laboratory may not capture the long-term relationships and interactive dynamics in real work teams (Tsai et al. 2012). Thus, in this study, we aim to examine how and when ethical leadership associates with knowledge hiding in real work contexts.

To explicate whether and how ethical leadership relates to knowledge hiding in the workplace, we adopt the social learning perspective (Bandura 1977). Social learning theory suggests that individuals may try to emulate the behaviors of role models (e.g., supervisors) in their work environments (Bandura 1977). Accordingly, ethical leaders’ proactive communication about what is (un-)ethical behavior, and their open and transparent knowledge sharing, gives employees a model of what is (in-)appropriate behavior at work (Bouckenooghe et al. 2015; Gok et al. 2017). Thus, social learning theory may be a useful perspective to explore why employees are less likely to hide their knowledge when under ethical leadership. Drawing insights from social learning theory (Bandura 1977), we explore the influence of ethical leadership on employees’ knowledge hiding behaviors. Also, the study examines the psychological mechanism through which ethical leadership influences employees’ knowledge hiding behaviors. Employees under ethical leadership are likely to perceive mutual respect that goes beyond interpersonal trust, leading to high psychological safety (Walumbwa and Schaubroeck 2009). Psychological safety—the extent to which individuals believe their colleagues (e.g., supervisors, coworkers) will not punish or misunderstand them for taking risks (Liang et al. 2012)—is an important intervening mechanism linking leadership and outcomes (Siemsen et al. 2009). Also by articulating psychological safety as a crucial motivation for employees to voice (Liang et al. 2012), share, and exchange knowledge (Siemsen et al. 2009), we argue that ethical leadership has implications for the psychological safety of employees, which, in turn, associates with knowledge hiding.

In addition, we extend our model of ethical leadership and knowledge hiding by identifying a key boundary condition of our presumed causal sequence. From the perspective of the organization, a mastery climate is extremely important in understanding how to inhibit knowledge hiding (Cerne et al. 2014). Social learning and psychological safety theorists also typically develop their perspectives under the assumption of a mastery climate, which values employees’ efforts, cooperation, learning, and self-development (Brown and Treviño 2006; Gok et al. 2017). In a mastery climate, employees may view knowledge hiding as a destructive behavior because it inhibits the mutual benefits of knowledge exchange such as skill-development in their work teams (Cerne et al. 2014). In addition, mastery climate has been highlighted as a key contextual moderator in the knowledge hiding literature (Cerne et al. 2014). Thus, we propose to examine the boundary conditions of the ethical leadership–knowledge hiding link by testing the moderating role of mastery climate.

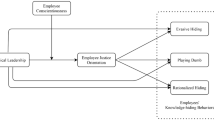

Our theoretical point of view and empirical results offer significant contributions to the leadership and knowledge management literatures respectively. First, we provide the first empirical test of how ethical leadership negatively impacts knowledge hiding in the workplace. According to social learning theory and the psychological safety perspective, we develop a mediation model that links ethical leadership to knowledge hiding through psychological safety. Second, we explore the contextual boundary condition of the effect of ethical leadership on knowledge hiding. In particular, we explore how to theorize and test the way in which psychological safety and mastery climate interact to affect knowledge hiding. In addition, this study uses a two-phase data collection and adopts a cross-level design which is helpful in providing more meaningful and robust outcomes. Figure 1 presents our research model.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Ethical Leadership and Knowledge Hiding

Ethical leadership is defined as “the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making” (Brown et al. 2005: p 120). According to Brown et al. (2005), ethical leadership encompasses two crucial dimensions. One is the moral person component, wherein ethical leaders possess personal traits and desirable characteristics such as integrity, honesty, and trustworthiness. The other is moral manager component, whereby ethical leaders proactively seek to influence followers’ ethical conduct such as encouraging normative behavior and punishing unethical behavior (Brown and Treviño 2006). These proactive efforts encompass role modeling behaviors and the communication of high-performance expectations to hold followers responsible for normatively appropriate conduct while treating followers fairly (Bouckenooghe et al. 2015). Thus, ethical leaders may consciously or unconsciously influence employee behaviors through role modeling, a process explained by social learning theory (Bandura 1977).

In this study, we argue that the social learning theory (Bandura 1977) can help to explain the effect of ethical leadership on knowledge hiding. Social learning theory represents a departure from reinforcement theories of learning by arguing that individuals can learn appropriate behaviors through a role-modeling process, by observing the behaviors of others (Liden et al. 2014). According to Liden et al. (2014), role modeling which involves both a demonstration of the appropriate behaviors and the guidance of followers through activities such as punishments and rewards that have been shown to be especially effective in evoking attitude change and behavior in followers. Specifically, in choosing role models for appropriate behavior, employees may pay attention to and emulate behaviors from attractive and credible role models. Given their positions in organizations, ethical leaders are often viewed as attractive and legitimate models for normative behaviors. In this regard, ethical leaders provide important clues to employees to engage in ethical behaviors instead of unethical behaviors such as knowledge hiding (Brown et al. 2005). In addition, ethical leaders can encourage employees to engage in ethical and desired behaviors, because they have the power to deliver either punishments or rewards. That is, ethical leaders may reward employees who display the pro-social behaviors such as knowledge sharing. By contrast, ethical leaders may discipline unethical behaviors such as knowledge hiding. In sum, it is argued that ethical leadership has a negative effect on employees’ knowledge hiding behaviors because, through behaving in an ethical manner and punishing or rewarding (in-)appropriate behavior, they clarify to the employees that what the right thing should do in the workplace.

Previous research has explored the processes underlying the ethical leadership–follower outcomes link and has demonstrated that trust plays a crucial mediating role (Epitropaki and Martin 2005). While we acknowledge the importance of the quality of social exchange between leaders and followers measured as affective trust (Zhu et al. 2013), this emphasis on trust may have obscured the consideration of other dimensions or facets that define high quality relation between followers and leaders (Zhang et al. 2012). According to Edmondson (1999), psychological safety goes beyond perceiving and experiencing high levels of interpersonal trust; it also describes a work climate characterized by mutual respect, one in which employees are comfortable to share and exchange knowledge. Furthermore, a number of scholars and practitioners argued that leader behaviors that draw on an internalized moral perspective and positive ethical climate can increase employees’ psychological safety (Brown and Treviño 2006). Thus, in this study, we take into account the mediating effect of psychological safety in the relation between ethical leadership and knowledge hiding.

Ethical Leadership and Psychological Safety

We expect ethical leadership to influence employees’ psychological safety in the workplace. By definition, ethical leaders exhibit normatively appropriate conduct through their actions and interpersonal relationships with employees in work units (Brown et al. 2005). Also, they exhibit social responsiveness and caring by communicating to employees that their best interests are the leaders’ primary concern (Brown et al. 2005). Drawing on social learning theory, the behaviors displayed by ethical leaders may “trickle down” to followers encouraging those who witness the behaviors to behave in a fairly homogeneous manner toward their coworkers (Mayer et al. 2012; Quade et al. 2017). Accordingly, when ethical leaders interact with their employees with truthfulness and openness, mutual respect and interpersonal trust will be promoted both between the leader and followers and among the followers themselves (Walumbwa and Schaubroeck 2009). Moreover, prior work has suggested when employees observed interpersonal behavior displayed by ethical leaders in their work teams such as benevolence, advocacy, loyalty, and caring, higher levels of liking, commitment, participation, trust, and collaboration may result (Mayer et al. 2012). Thus, by working under ethical leaders, employees are more likely to engage in interpersonal risk taking, and demonstrate trust and mutual respect with coworkers (Mayer et al. 2012). According to Edmondson (1999), psychological safety describes a psychological state characterized by mutual respect and interpersonal trust, in which individual employees are comfortable being themselves and engage in interpersonal risk taking. Thus, ethical leadership plays an important role in shaping employees’ psychological safety.

Indeed, empirical research has shown that psychological safety represents one of the most prominent psychological mechanisms in the organizational literature (Liu et al. 2016), and has been shown to play a critical mediating role between ethical leadership and positive work outcomes (Walumbwa and Schaubroeck 2009). Thus, it suggests a possible positive relation between ethical leadership and psychological safety. Based on both theoretical reasoning and empirical research, we argue that:

Hypothesis 1

Ethical leadership is positively related to psychological safety.

Psychological Safety and Knowledge Hiding

Knowledge hiding refers to an intentional attempt to conceal or withhold knowledge that has been requested by others (Connelly et al. 2012). Knowledge hiding occurs between employees, and the interpersonal trust among employees is likely to affect how an individual employee responds to a request for knowledge from a coworker (Connelly et al. 2012). We expect psychological safety to associate with knowledge hiding for two reasons. First, psychological safety stems from mutual respect and interpersonal trust (Kahn 1990), factors that the empirical literature has shown to be central to knowledge hiding (Connelly et al. 2012). Specifically, psychological safety describes an individual’s perceptions as to whether he is comfortable to show and employ himself without fear of negative consequences to self-image, status, or career. An individual is more likely to feel psychologically safe when he has trusting and supportive interpersonal relationships with his work colleagues (Kahn 1990). That is, if an individual has a high psychological safety, he will feel confident that the surrounding interpersonal context is not threatening, and he will trust his coworkers and not be embarrassed or punished for expressing himself (Zhang et al. 2010). By contrast, an individual with a low psychological safety may have a basic mind-set of distrust—that is, a lack of confidence in his or her coworkers/ or a concern that the coworkers may do harm to him. According to Connelly et al. (2012), interpersonal distrust is likely to influence individual employees’ knowledge hiding behaviors. Thus, an individual with low psychological safety may be lack of confidence in their coworkers and engage in knowledge hiding.

Second, high psychological safety gives an individual more motivation to communicate and share work-related knowledge with others, because he or she feels less threatened by exposure to the judgment of the recipient (Liu et al. 2016; Zhao et al. 2016). According to Ehrhart (2004), frequent communication and interactions with other colleagues about work events are helpful to foster shared meaning and collective judgments about the work environments. Thus, high psychological safety can facilitate employees to engage in open communication and be helpful to create a knowledge sharing climate for employees to exchange and share work-related knowledge (Siemsen et al. 2009). Prior research has suggested that knowledge sharing climate is crucial to employees’ knowledge hiding behaviors (Connelly et al. 2012). Thus, we predict:

Hypothesis 2

Psychological safety will relate negatively to knowledge hiding.

Integrating the first two hypotheses suggests the possibility that psychological safety acts as a mediating role in the relation between ethical leadership and followers’ knowledge hiding behaviors. Specifically, previous research has suggested that ethical leadership can inhibit knowledge hiding (e.g., Tang et al. 2015), while empirical evidence to support this speculation in the workplace has been lacking. Because psychological safety is considered a strong precursor to knowledge sharing and exchange (Siemsen et al. 2009), and ethical leadership is an important factor to enhance psychological safety (Hung and Paterson 2017), it is logical that ethical leadership will inhibit followers’ knowledge hiding behaviors through encouraging the development of psychological safety (e.g., Walumbwa and Schaubroeck 2009). Accordingly, we argue that the important precursor to psychological safety, ethical leadership, will be associated with psychological safety, which in turn will inhibit knowledge hiding. Thus, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 3

Psychological safety mediates the relation between ethical leadership and knowledge hiding.

The Moderating Effect of Mastery Climate

Research indicates that achievement context plays an essential role in knowledge hiding (Connelly et al. 2012). Mastery climate that focuses on self-improvement represents such a context (Cerne et al. 2014). According to Cerne et al. (2014), mastery climate has been highlighted as a contextual moderator in the literature of knowledge hiding. Moreover, social learning and psychological safety theories explicitly assume a mastery climate. By extension, the relation between ethical leadership and knowledge hiding, via psychological safety, should be weakened in a high mastery climate.

A mastery climate may reduce the motivation for knowledge hiding (Nerstad et al. 2013). Specifically, in a mastery climate, success requires an inherent focus on cooperation (Cerne et al. 2014). As such behavior is signaled to be publicly recognized, expected, and rewarded, individual employees should be less likely to engage in knowledge hiding. This tendency is possibly due to employees’ focus on learning and self-improvement (Poortvliet and Giebels 2012), and they cannot realized that by hiding knowledge. Thus, in a mastery climate, employees may be more prone to valuing their own self-improvement by engaging in less knowledge hiding behavior, seeking positive cooperation by thus prompting their skill-development.

Additionally, from an interactionist perspective, we would expect that psychological safety and mastery climate should work together to affect knowledge hiding. Specifically, when individual employees have high psychological safety, they have the internal drive to communicate and share work-related knowledge, and they work in a mastery climate that is supportive of knowledge exchange, knowledge hiding behaviors should be reduced (Ames and Archer 1988). Individuals with high psychological safety should be more likely to engage in knowledge sharing when their work climate encourages, values, and rewards these types of initiatives (Siemsen et al. 2009). In contrast, we would expect those with low psychological safety and in a climate that is not supportive of knowledge exchange and cooperation to be more likely to engage in knowledge hiding. In sum, in a high mastery climate, psychological safety allows team members to engage in risk taking and reduce the motivation of knowledge hiding. We therefore hypothesize:

Hypothesis 4

The relation between psychological safety and knowledge hiding will be moderated by a mastery climate. The higher the mastery climate, the less negative the relation.

Assuming a mastery climate moderates the relation between psychological safety and knowledge hiding, it is also likely that a mastery climate will conditionally influence the strength of the indirect relation between ethical leadership and knowledge hiding—thereby demonstrating a pattern of moderated mediation between the variables in our study, as depicted in Fig. 1. Because we predict a weak (strong) relation between psychological safety and knowledge hiding in a high (low) mastery climate, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 5

The strength of the mediated relation between ethical leadership and knowledge hiding (through psychological safety) will depend on the mastery climate; the indirect of ethical leadership on knowledge hiding will be weaker when the mastery climate is high.

Method

Sample and Procedure

Data were collected from subordinates and their direct supervisors from 96 knowledge work teams (such as project teams and R&D teams) in Chinese high-technology organizations located in the eastern part of China (63.54% in software; 31.26% in meters and equipment manufacturing; 5.20% in biotechnology and pharmaceuticals). Access to the participants was gained through professional and personal contacts of the author(s). The team supervisors were contacted by one of the authors to introduce the study. We delivered separate questionnaires to the subordinates and supervisors. In the survey, the questionnaires were coded before being distributed to match the employee responses (T1 and T2) with the responses of their direct supervisors (T1). Respondents were instructed to put their completed surveys into sealed envelopes, and the researcher collected the sealed envelopes. The teams agreed to engage on condition that a copy of the findings could be obtained. Participation was voluntary, and respondents were assured of the anonymity of their responses. In addition, we told the participants that all identifying information would be removed to preserve their anonymity.

To reduce the potential common method biases (Podsakoff et al. (2003), we conducted surveys in two different phases separated by 6 weeks. According to Podsakoff et al. (2012), the time lag in data collection should neither be too long nor too short. If the time lag is too long, certain factors such as leadership development programs and strong response attrition may mask existing relation between variables (Babalola et al. 2017). By contrast, if the time lag is too short, memory effects may inflate the relation artificially between variables (Babalola et al. 2017). Thus, six weeks should offer an optimal choice of time lag (Babalola et al. 2017; Walumbwa and Schaubroeck 2009). In phase 1, we asked 595 employees to report ethical leadership, psychological safety, and demographic characteristics and collected 512 responses (86.1%). Also, we asked 97 team supervisors to assess mastery climate and team size and collected 83 responses (85.6%). After approximately six weeks, in phase 2, employees who had returned the completed first-wave questionnaires were asked to complete the second wave survey to assess knowledge hiding. Four hundred fifty-eight responses returned their completed surveys (89.5%).

Because of a small team such as fewer than three members and respondents with incomplete data (Shin et al. 2012), the final sample used in the analysis comprised 436 employees nested in 78 teams, with an average of 5.59 members per team. Their demographic data are as follows: 58.0% of the employees were male, and their average age was 33.50 years. For employees’ education, 47.2% had a master degree or above.

Measures

The measurements were originally developed in English, and we translated it into Chinese using the back-translation procedure (Brislin 1986). Specifically, two bilingual scholars independently translated the measurements from English to Chinese. A third bilingual scholar translated the measurements back to English and made modifications.

Ethical Leadership

Ethical leadership was measured using a ten-item scale developed by Brown et al. (2005). A sample item is “My supervisor defines success not just by results but also the way that they are obtained.” Ethical leadership was measured on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for ethical leadership was 0.83.

Knowledge Hiding

Knowledge hiding was measured using a twelve-item scale instrument developed by Connelly et al. (2012). A sample item is “I offered other members of my team some other information instead of what they wanted.” Knowledge hiding was measured on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for individual knowledge hiding was 0.80.

Psychological Safety

We measured psychological safety using Liang et al.’s (2012) five-item scale. A sample item is “Nobody in my unit will pick on me even if I have different opinions.” Psychological safety was measured on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for individual psychological safety was 0.80.

Mastery Climate

We measured mastery climate using Nerstad et al.’s (2013) six-item scale. A sample item is “In my department/work group, team members are encouraged to cooperate and exchange thoughts and ideas mutually.” The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for mastery climate was 0.75.

Control Variables

Several variables were controlled. Previous research has shown that individual demographics (i.e., age, gender, and educational level) are likely to influence employees’ knowledge behaviors (e.g., Connelly et al. 2012; Fong et al. 2018; Zhao et al. 2016). Thus, these variables were controlled in this study. Specifically, we controlled for individual employees’ educational level with four response options (1 = junior college or below; 2 = bachelor; 3 = master; 4 = doctorate). Gender was dummy coded, with female coded as 0 and male coded as 1. Age was self reported in years. In addition, team size was controlled in our study. Prior research suggests that larger team size is likely to diminish a leader’s ability to affect individual employees’ behavior and also influence knowledge hiding within workgroups (Zhao et al. 2016).

Analytic Strategy

Given the multilevel nature of the data in the current study, hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) analyses with the software HLM 6.08 were applied to test our hypotheses (Raudenbush et al. 2004). We first ran null models with no predictors but knowledge hiding as the dependent variable. The test results showed significant between-team variances in knowledge hiding (χ2 = 155.98, df = 77, p < 0.01; ICC1 = 0.23, indicating 23% of variance residing in between teams), justifying HLM as the appropriate analytic technique.

We used hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) and followed the procedure recommended by Baron and Kenny (1986) to test Hypothesis 3, which proposed the meditating role of psychological safety in the relation between ethical leadership and knowledge hiding. To test Hypothesis 4, which proposed a moderating role of mastery climate in the relation between ethical leadership and knowledge hiding of moral awareness on ethical leadership, we also used hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) and followed the procedure recommended by Baron and Kenny (1986). Following the approach recommended by Stone and Hollenbeck (1989), we computed the slopes using one standard deviation below and above the mean of the moderating variable mastery climate. In addition, to test Hypothesis 5, which proposed a mastery climate moderates the ethical leadership—psychological safety—knowledge hiding mediating linkage, we used Mplus 7.0 (Muthén and Muthén 2010) to calculate the normal distribution-based 95% confidence intervals (Liu et al. 2012).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 displays the means, standard deviations, correlations, and scale reliabilities. As shown in Table 1, the correlations of the study variables were in the expected directions, and all the study variables had an acceptable degree of internal consistency. Ethical leadership was positively related to employees’ psychological safety (r = 0.35, p < 0.01) and negatively related to knowledge hiding (r = − 0.21, p < 0.05). In addition, employees’ psychological safety was negatively related to knowledge hiding (r = − 0.52, p < .01).

Construct Validity

According to Anderson and Gerbing (1988), we examined the construct validity of the variables before testing the hypotheses. Because our measures of ethical leadership, psychological safety, and knowledge hiding came from the same source, we conducted a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) using AMOS 18.0 to examine the construct distinctiveness of the three major variables in our model. Results showed the three-factor model provided a good fit, with all fit indices within acceptable levels (χ2 = 645.52, df = 321, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.062). We further compared the three-factor model to a one-factor model that consisted of one single factor (χ2 = 2851.90, df = 324, CFI = 0.34, TLI = 0.29, RMSEA = 0.146). A Chi-square difference test showed the three-factor model exhibited a better fit than the one-factor model (χ2difference = 2206.38, df = 3, p < 0.01).

Graphical Depiction of the Mediating Effects

To analyze the cross-level data, we used hierarchical linear modeling (HLM). According to Raudenbush and Bryk (2004), HLM is an appropriate method for analyzing cross-level data because employees are nested within the team. The results are presented in Table 2. The results showed support for Hypothesis 3 (The mediating role of psychological safety in the relation between ethical leadership and knowledge hiding). We ran tests following the procedure recommended by Baron and Kenny (1986). First, ethical leadership was found to be significantly and positively related to psychological safety (Model 2: β = 0.45, p < 0.01), which explained 15 percent of the residual Level 1 variance in psychological safety (ΔR2 Level 1 model = 0.15). Second, ethical leadership was negatively related to knowledge hiding (Model 4: β = − 0.19 p < .01), which explained 13 percent of the residual Level 1 variance in psychological safety (ΔR2 Level 1 model = 0.13). Third, psychological safety was significantly and negatively related to knowledge hiding (Model 5: β = − 0.39, p < .01), which explained 31 percent of the residual Level 1 variance in psychological safety (ΔR2 Level 1 model = 0.31). Finally, the significant coefficient of ethical leadership for knowledge hiding was no longer significant after adding psychological safety (Model 6: β = − 0.02, n. s.). This indicates that psychological safety fully mediated the relation between ethical leadership and knowledge hiding.

Graphical Depiction and Simple Slopes of the Moderating Effects

Hypothesis 4

proposes that a mastery climate moderates the relation between psychological safety and knowledge hiding. Table 2 deals with the interaction effects of mastery climate and psychological safety on knowledge hiding. Results showed that the interaction between psychological safety and mastery climate was positively related to knowledge hiding (r = 0.16, p < 0.05, Model 8), which explained 31 percent of the residual Level 1 variance in psychological safety (ΔR2 Level 1 model = 0.31). The interaction effects were plotted using Stone and Hollenbeck’s (1989) procedure. Specifically, we computed the slopes using one standard deviation below and above the mean of the moderating variable mastery climate. Figure 2 shows that psychological safety is less negatively related to knowledge hiding when the mastery climate is high (r = − 0.23, p < 0.01) rather than low (r = − 0.55, p < 0.01). Thus, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

Hypothesis 5

predicts that a mastery climate moderates the ethical leadership–psychological safety–knowledge hiding mediating linkage. To test Hypothesis 5, we used Mplus 7.0 to calculate the normal distribution-based 95% confidence intervals for the indirect effects of ethical leadership on knowledge hiding via psychological safety at “low” and “high” values of mastery climate (one standard deviation below and above the average), as well as the difference between the conditional indirect effects (Liu et al. 2012). As shown in Table 3, the indirect effect of ethical leadership via psychology safety on knowledge hiding is stronger when the mastery climate is low [b = − 0.33, SE = 0.05, CI (− 0.43, − 0.23)] than when the mastery climate is high [b = 0.01, SE = 0.03, CI (− 0.04, 0.06)]. Furthermore, the indirect effects of ethical leadership via psychological safety on knowledge hiding differ significantly when the mastery climate is at high versus low levels [difference between conditional indirect effects = 0.34, SE = 0.05, CI (0.25, 0.44)]. That is, the indirect effect of ethical leadership on knowledge hiding (via psychological safety) became weaker in a high mastery climate. Thus, Hypothesis 5 was supported.

Discussion

Our study examined the relation between ethical leadership and knowledge hiding. As predicted, ethical leadership negatively associated with knowledge hiding. The results showed that psychological safety mediated the relation between ethical leadership and knowledge hiding, that a mastery climate moderated the relation between psychological safety and knowledge hiding, and that the indirect effect of ethical leadership on knowledge hiding (via psychological safety) was weaker when a mastery climate was high rather than low.

Theoretical Implications

This study makes several theoretical contributions to the ethical leadership and knowledge hiding literatures. First, our study enhances the understanding of the role of positive leader behaviors in the development of knowledge hiding. Previous works regarding the relation between leadership and knowledge management have exclusively centered on identifying positive knowledge behaviors such as knowledge sharing (e.g., Zhang et al. 2011). For example, Bavik et al. (2018) examined the relation between ethical leadership and knowledge sharing. However, the influence of leadership on negative knowledge behaviors such as knowledge hiding has generally been left unexplored (Zhao et al. 2016). Our study provides empirical evidence on the relation between ethical leadership and knowledge hiding, which has never been examined except by Tang et al. (2015). However, in their study, participants were full-time university students. Thus, this study was the first to explore the relation between ethical leadership and knowledge hiding in the workplace.

Second, we found psychological safety to be a crucial intervening variable in the ethical leadership–knowledge hiding relation. Drawing on social learning theory and the psychological safety perspective, ethical leadership can enhance the development of individual employees’ psychological safety, which in turn will inhibit knowledge hiding. In general, the results show the potential benefits of ethical leadership and that its influence on knowledge hiding is exerted through psychological safety.

Third, this study showed that the indirect relation between ethical leadership and knowledge hiding through psychological safety was conditional on a mastery climate. In a low mastery climate, psychological safety has greater influence on knowledge hiding. Thus, another contribution of this study is to identify the contextual boundary conditions shaping the nature of the ethical leadership–knowledge hiding relation. Specifically, this study not only theoretically identified the interaction effect of psychological safety and mastery climate on knowledge hiding, but also empirically examined the moderating role of mastery climate in the relation between psychological safety and knowledge hiding.

Last but not least, our study demonstrated that the mediation-chain relation was more complicated than was previously understood, in that the relation seems to vary with a mastery climate. By adopting Edwards and Lambert’s (2007) moderated mediation approach, we found that the mediating effect of psychological safety in the relation between ethical leadership and knowledge hiding can be significantly stronger or weaker, depending on a mastery climate. In particular, our study showed that the mediating effect of psychological safety in the relation between ethical leadership and knowledge hiding was weaker in a mastery climate.

Practical Implications

Our study also provides some implications for managerial practices. First, we encourage managers to demonstrate high ethical standards, engage in concurrent reward and punishment programs, and practice ethical role modeling (Tang et al. 2015). Such efforts would be worthwhile because they can enhance the development of individual employees’ psychological safety. Employees with high psychological safety are less likely to engage in knowledge hiding. To help leaders to enhance the level of ethical leadership, organizations can offer training programs toward nurturing leaders’ ethical sensitivity, provide examples of ethical conduct that leaders should manifest in their management policies and daily behavior, and set up formal and informal mentoring programs (Bavik et al. 2018).

Second, our study supports a mastery climate as a suitable work environment for decreasing employees’ knowledge hiding behaviors. Thus, organizations can reduce knowledge hiding behaviors by establishing a mastery climate, which emphasizes learning, cooperation, and skill development. For example, managers can create a mastery climate through providing specific training and development programs which can facilitate employees to obtain work-related skills, value cooperation, and identify the criteria for success and failure during task execution. Also, managers may provide institutionalized platforms or channels for communication and knowledge exchange. These may be helpful to foster a mastery climate, which in turn will inhibit knowledge hiding.

In addition, our study has found that psychological safety plays an important mediating role in the relation between ethical leadership and knowledge hiding. Managers should take measures to improve team members’ psychological safety because psychological safety is dynamic and can be enhanced through leader relations (Frazier et al. 2017). For example, managers should interact with employees with openness and truthfulness and provide a psychologically secure environment for them. This can enhance employees’ perceived psychological safety, which in turn will decrease employees’ knowledge hiding behaviors.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

This study also has some potential limitations. First, our examples of ethical leadership, psychological safety, and knowledge hiding came from the same source. However, according to Podsakoff et al. (2003), the use of a lagged design can alleviate such common method bias. Nevertheless, future research should address this issue by using experimental designs to strengthen causal inference.

Second, our study built and tested a theoretical model at both the individual and team level. Also, we included several control variables at individual and team levels. Specifically, we controlled for age, gender, education, at the individual level, and for team size at the team level. However, according to Serenko and Bontis (2016), the variables at the organizational level such as organizational culture can also affect employees’ knowledge hiding behaviors. Future research should control organizational culture and examine whether this theoretical model is supported at the organizational level of analysis.

Third, according to social learning theory, we examined a mechanism linking ethical leadership and knowledge hiding. However, other potential mechanisms cannot be ruled out. As the field of knowledge hiding moves forward, other potential mechanisms with different theoretical approaches should be explored. For example, psychological ownership may cognitively stimulate knowledge hiding (Huo et al. 2016). Future research should capture this phenomenon and then examine it as a potential mediating mechanism.

In addition, other plausible variables may exist that play moderating roles in the relation between ethical leadership and knowledge hiding, such as self-monitoring, professional commitment, political skill, conscientiousness, social norms, and morality-based individual differences (Connelly et al. 2012). For example, Connelly et al. (2012) indicated that employees with high levels of professional commitment are less likely to hide knowledge, because they view responding to coworkers’ requests as their professional responsibility. While Sturm (2017) argued that morality-based individual differences such as perceptual moral attentiveness and reflective moral attentiveness can decrease unethical decisions. Future research should examine these moderating effects in the relation between ethical leadership and knowledge hiding.

Conclusion

In this study, we provide initial evidence that ethical leadership is positively related to knowledge hiding via psychological safety in the workplace. Moreover, a mastery climate plays a moderating role, whereby it weakens the relation that psychological safety has with knowledge hiding. Taken together, our mediated moderation model explains how and when ethical leadership matters most. Our findings contribute to the leadership and knowledge management literatures by exploring the relation of ethical leadership and knowledge hiding to previously unexplored mediators and moderators in the workplace. In doing so, this study provides a springboard for future research to explore other constructs and uncover the underlying mechanisms that inhibit knowledge hiding.

References

Ames, C., & Archer, J. (1988). Achievement goals in the classroom: Students’ learning strategies and motivation processes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80, 260–267.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411–423.

Avey, J. B., Wernsing, T. S., & Palanski, M. E. (2012). Exploring the process of ethical leadership: The mediating role of employee voice and psychological ownership. Journal of Business Ethics, 107, 21–34.

Babalola, M. T., Stouten, J., Camps, J., & Euwema, M. (2017). When do ethical leaders become less effective? The moderating role of perceived leader ethical conviction on employee discretionary reactions to ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3472-z.

Babcock, P. (2004). Shedding light on knowledge management. Human Resource Magazine, 49, 46–50.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual,strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Bavik, Y. L., Tang, P. M., Shao, R., & Lam, L. W. (2018). Ethical leadership and employee knowledge sharing: Exploring dual-mediation paths. Leadership Quarterly, 29, 322–332.

Bouckenooghe, D., Zafar, A., & Raja, U. (2015). How ethical leadership shapes employees’ job performance: The mediating roles of goal congruence and psychological capital. Journal of Business Ethics, 129, 251–264.

Brislin, R. W. (1986). Research instruments. Field Methods In Cross-Cultural Research, 8, 159–162.

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadership Quarterly, 17, 595–616.

Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97, 117–134.

Cerne, M., Nestad, C. G. L., & Skervalaj, M. (2014). What goes around comes around: Knowledge hiding, perceived motivational climate, and creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 57, 172–192.

Connelly, C. E., Zweig, D., Webster, J., & Trougakos, J. P. (2012). Knowledge hiding in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33, 64–88.

Demirtas, O., & Akdogan, A. A. (2015). The effect of ethical leadership behavior on ethical climate, turnover intention, and affective commitment. Journal of Business Ethics, 130, 59–67.

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 350–383.

Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 12, 1–22.

Ehrhart, M. G. (2004). Leadership and procedural justice climate as antecedents of unit-level organizational citizenship behavior. Personnel Psychology, 57, 61–94.

Epitropaki, O., & Martin, R. (2005). From ideal to real: A longitudinal study of the role of implicit leadership theories on leader–member exchanges and employee outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 659–676.

Fong, P. S. W., Men, C. H., Luo, J. L., & Jia, R. Q. (2018). Knowledge hiding and team creativity: The contingent role of task interdependence. Management Decision, 56, 329–343.

Frazier, M. L., Fainshmidt, S., Klinger, R. L., Pezeshkan, A., & Vracheva, V. (2017). Psychological safety: A meta-analytic review and extension. Personnel Psychology, 70, 113–165.

Gok, K., Sumanth, J. J., Bommer, W. H., Demirtas, O., Arslan, A., Eberhard, J., Ozdemir, A. I., & Yigit, A. (2017). You may not reap what you sow: How employees’ moral awareness minimizes ethical leadership’s positive impact on workplace deviance. Journal of Business Ethics, 146, 1–21.

Hung, L., & Paterson, T. A. (2017). Group ethical voice: Influence of ethical leadership and impact on ethical performance. Journal of Management, 43, 1157–1184.

Huo, W. W., Cai, Z. Y., Luo, J. L., Men, C. H., & Jia, R. Q. (2016). Antecedents and intervention mechanisms: A multi-level study of R&D team’s knowledge hiding behavior. Journal of Knowledge Management, 20, 880–897.

Kacmar, K. M., Bachrach, D. G., Harris, K. J., & Zivnuska, S. (2011). Fostering good citizenship through ethical leadership: Exploring the moderating role of gender and organizational politics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 633–642.

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 692–724.

Lee, D., Choi, Y., Youn, S., & Chun, J. U. (2017). Ethical leadership and employee moral voice: The mediating role of moral efficacy and the moderating role of leader-follower value congruence. Journal of Business Ethics, 141, 47–57.

Lee, S., Kim, S. L., & Yun, S. (2018). A moderated mediation model of the relationship between abusive supervision and knowledge sharing. Leadership Quarterly, 29, 403–413.

Liang, J., Farh, C. I., & Farh, J. L. (2012). Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave examination. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 71–92.

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Liao, C., & Meuser, J. D. (2014). Servant leadership and serving culture: Influence on individual and unit performance. Academy of Management Journal, 57, 1434–1452.

Liu, D., Zhang, Z., & Wang, M. (2012). Mono-level and multilevel mediated moderation and moderated mediation. In X. Chen, A. Tsui & I. Farh (Eds.), Empirical methods in organization and management research (2nd ed.)). Beijing: Peking University Press.

Liu, W. X., Zhang, P. C., Liao, J. Q., Hao, P., & Mao, J. H. (2016). Abusive supervision and employee creativity: The mediating role of psychological safety and organizational identification. Management Decision, 54, 130–147.

Mayer, D. M., Aquino, K., Greenbaum, R. L., & Kuenzi, M. (2012). Who displays ethical leadership, and why does it matter? An examination of antecedents and consequences of ethical leadership. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 151–171.

Mo, S. J., & Shi, J. Q. (2017). Linking ethical leadership to employees’ organizational citizenship behavior: Testing the multilevel mediation role of organizational concern. Journal of Business Ethics, 141, 151–162.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2010). Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Nerstad, C. G. L., Roberts, G. C., & Richardsen, A. M. (2013). Achieving success at work: The development and validation of the motivational climate at work questionnaire (MCWQ). Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43, 2231–2250.

Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2015). Ethical leadership: Meta-analytic evidence of criterion-related and incremental validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100, 948–965.

Peng, H. (2013). Why and when do people hide knowledge? Journal of Knowledge Management, 17, 398–415.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Source of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569.

Poortvliet, P. M., & Giebels, E. (2012). Self-improvement and cooperation: How exchange relationships promote mastery-approach driven individuals’ job outcomes. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 21, 392–425.

Quade, M. J., Perry, S. J., & Hunter, E. M. (2017). Boundary conditions of ethical Leadership: Exploring supervisor-induced and job hindrance stress as potential inhibitors. Journal of Business Ethics, 6, 1–20.

Raudenbush, S. W., Bryk, A. S., Cheong, Y. F., & Congdon, R. T. Jr. (2004). HLM 6: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Chicago: Scientific Software International.

Serenko, A., & Bontis, N. (2016). Understanding counterproductive knowledge behavior: Antecedents and consequences of intra-organizational knowledge hiding. Journal of Knowledge Management, 20, 1199–1224.

Shin, S. J., Kim, T. Y., Lee, J. Y., & Bian, L. (2012). Cognitive team diversity and individual team creativity: A cross-level interaction. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 197–212.

Shin, Y. (2014). Positive group affect and team creativity: Mediation of team reflexivity and promotion focus. Small Group Research, 45, 337–364.

Siemsen, E., Roth, A. V., Balasubramanian, S., & Anand, G. (2009). The influence of psychological safety and confidence in knowledge on employee knowledge sharing. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, 11, 429–447.

Stone, E. F., & Hollenbeck, J. R. (1989). Clarifying some controversial issues surrounding statistical procedures for detecting moderator variables: Empirical evidence and related matters. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 3–10.

Sturm, R. E. (2017). Decreasing unethical decisions: The role of morality-based individual differences. Journal of Business Ethics, 142, 37–57.

Tang, P. M., Bavik, Y. L., Chen, Y. F., & Tjosvold, D. (2015). Linking ethical leadership to knowledge sharing and knowledge hiding: The mediating role of psychological engagement. International Proceedings of Economics Development and Research, 84, 71–76.

The Globe and Mail. (2006). The weekly web poll.

Treviño, L. K., Chao, M. M., & Wang, W. Y. (2015). Ethical leadership and follower voice and performance: The role of follower identifications and entity morality beliefs. Leadership Quarterly, 26, 702–718.

Tsai, W., Chi, N., Grandey, A. A., & Fung, S. (2012). Positive group affective tone and team creativity: Negative group affective tone and team trust as boundary conditions. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33, 638–656.

van Gils, S., Van Quaquebeke, N., van Knippenberg, D. L., van Dijke, M. H., & Cremer, D. D. (2015). Ethical leadership and follower organizational deviance: The moderating role of follower moral attentiveness. Leadership Quarterly, 26, 190–203.

Walumbwa, F. O., Hartnell, C. A., & Misati, E. (2017). Does ethical leadership enhance group learning behavior? Examining the mediating influence of group ethical conduct, justice climate, and peer justice. Journal of Business Research, 72, 14–23.

Walumbwa, F. O., Morrison, E. W., & Christensen, A. L. (2012). Ethical leadership and group in-role performance: The mediating roles of group conscientiousness and group voice. Leadership Quarterly, 23, 953–964.

Walumbwa, F. O., & Schaubroeck, J. (2009). Leader personality traits and employee voice behavior: Mediating roles of ethical leadership and work group psychological safety. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 1275–1286.

Zhang, A. Y., Tsui, A. S., & Wang, D. X. (2011). Leadership behaviors and group creativity in Chinese organizations: The role of group processes. Leadership Quarterly, 22, 851–862.

Zhang, Y. X., Fang, Y. L., Wei, K. K., & Chen, H. P. (2010). Exploring the role of psychological safety in promoting the intention to continue sharing knowledge in virtual communities. International Journal of Information Management, 30, 425–436.

Zhang, Z., Wang, M., & Shi, J. (2012). Leader-follower congruence in proactive personality and work outcomes: The mediating role of leader-member exchange. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 111–130.

Zhao, H. D., Xia, Q., He, P. X., Sheard, G., & Wan, P. (2016). Workplace ostracism and knowledge hiding in service organizations. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 59, 84–94.

Zhu, W., Newman, A., Miao, Q., & Hooke, G. (2013). Revisiting the mediating role of trust on transformational leadership effects: Do different types of trust make a difference? Leadership Quarterly, 24, 94–105.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank The National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 71772138, 71472137, 71701004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Men, C., Fong, P.S.W., Huo, W. et al. Ethical Leadership and Knowledge Hiding: A Moderated Mediation Model of Psychological Safety and Mastery Climate. J Bus Ethics 166, 461–472 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-4027-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-4027-7