Abstract

For decades, scholars have debated the corporate objective. Scholars have either advocated a corporate objective focused on generating value for shareholders or creating value for multiple groups of stakeholders. Although it has been established that the corporate objective can shape many aspects of the corporation—including culture, compensation, and decision making—to date, scholars have not yet explored its psychological impact; particularly, how the corporate objective might influence employee well-being. In this article, we explore how two views of the corporate objective affect employee self-determination, a key component of overall psychological need satisfaction and well-being. We hypothesize that a corporate objective based on creating value for multiple stakeholders will increase employee psychological need satisfaction as compared to one focused on creating value for only shareholders. Across four experimental studies and one field survey, we find consistent support for our hypotheses and test three facets of a stakeholder-focused corporate objective. Theoretical implications and future research directions are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Employee psychological well-being has been linked to a variety of important individual and organizational outcomes (Deci and Ryan 2011; Baard et al. 2004; Ilardi et al. 1993; Gagné and Deci 2005) such as positive affect (Sheldon et al. 2001), increased creativity (Amabile 1983; Rosen et al. 2014), proactive behaviors at work (Rosen et al. 2014), and increased work engagement (Deci et al. 2001). This research has largely focused on the individual and interpersonal antecedents of employee well-being, and, therefore, scholars have called for better understanding of the impact of organizational context on employee well-being (Greguras and Diefendorff 2009; Sheldon et al. 2003; Johns 2006). One important element of organizational context is a firm’s corporate objective—or the purposes to which an organization directs its resources and attention (Freeman et al. 2004). Our goal is to examine how different corporate objectives shape employee well-being, specifically their level of psychological need satisfaction at work.

The debates about the corporate objective have been dominated by two main perspectives since the 1930s: one based on ownership rights (Jensen and Meckling 1979; Sundaram and Inkpen 2004; Friedman 1970; Berle and Means 1968), which we refer to as the “shareholder perspective,” and another based on stakeholder rights (Freeman 1984, 1994; Berle and Means 1968; Keay 2008), which we refer to as the “stakeholder perspective.” The shareholder perspective sees the corporation as an economic entity whose primary objective is to maximize shareholder value (Sundaram and Inkpen 2004; Bradley et al. 1999). The term shareholder value can apply specifically to profits (Friedman 1970) or the total financial value of the firm, including equity, debt, preferred stock, and warrants (Jensen 2002).

In contrast, the stakeholder perspective sees the corporation as a cooperative endeavor with a primary purpose of creating value for a range of different stakeholders, including but not limited to customers, employees, suppliers, investors, and the community. From this view, managers consider the legitimate interests of the firm’s stakeholders or the people who could be affected by or who could affect the organization’s activities (Donaldson and Preston 1995; Freeman 1994). Decisions about the corporate objective influence a variety of organizational systems and routines from governance to compensation (Jensen 2002).

To date, debates about the merits and implications of stakeholder and shareholder theory have remained largely theoretical, especially as they pertain to the psychological impact on individual stakeholders. To better understand how organizational context affects employee psychological well-being, our research question is, “Does a corporate objective framed around creating value for multiple stakeholders better support employee psychological well-being than a corporate objective framed around creating value only for shareholders?”

To understand employee psychological well-being, we utilize self-determination theory, a theory of motivation positing that individuals aim to satisfy three key psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Deci and Ryan 1980; Ryan and Deci 2000). An organizational context that promotes psychological need satisfaction will also support intrinsic motivation, facilitate the internalization of extrinsic goals or objectives, and increase the likelihood of positive individual and organizational outcomes (Gagné and Deci 2005). Individuals who focus on living well by satisfying their needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness have been shown to act more prosocial and create benefits for the group and themselves (Ryan et al. 2013). A corporate objective plays an important role in shaping the context in which employees will internalize and enact behaviors that support the organization’s stated objectives (Barnard 1968).

To empirically examine the effects of a corporate objective on self-determination at work, we conduct four laboratory studies and one online survey. We hypothesize, and our empirical results demonstrate that a corporate objective framed around creating value for multiple stakeholders will increase employees’ perceived levels of need satisfaction at work. We also explore three facets of a stakeholder-focused corporate objective suggested in the literature to understand better how it may drive increases in self-determination at work: (1) the idea that a stakeholder-focused objective creates the opportunity for organizations to be purpose-driven, specific organizations can define their purpose beyond profit maximization and use those shared values to align stakeholder interests (Freeman et al. 2007), (2) the idea that the number of stakeholders increases managerial discretion (Sundaram and Inkpen 2004), and (3) the idea taken from evolutionary psychology that human beings are wired to focus on other individuals rather than abstract artifacts such as profits (Walton et al. 2012; Haidt et al. 2008; Chudek and Henrich 2011).

This article and its results contribute to existing theory and practice in several ways. First, this research makes an important advance in the debate about corporate objective by going beyond theoretical arguments to empirically assess the impact of the dominant perspective about corporate objectives on the psychological well-being of employees. Second, we develop and test a series of hypotheses that propose specific ways in which stakeholder theory may create value for employees answering calls to understand better how firms create non-financial value for stakeholders (Freeman et al. 2010). Third, we examine important contextual antecedents of employee self-determination at work; therefore, our results have implications for how managers should think about their organization’s objective if they want to increase the psychological well-being of their employees.

In the subsequent sections, we review the relevant research on self-determination theory and the corporate objective. We develop hypotheses that predict that a stakeholder-focused corporate objective will increase employee self-determination at work, then present supporting evidence through five studies, and close with a discussion of the theoretical and practical implications of our results.

Self-Determination at Work

Self-determination theory (Deci 1976; Ryan and Deci 2000) argues that individuals are able to grow and develop based on their ability to satisfy three needs—autonomy, relatedness, and competence in—specific conditions that facilitate intrinsic motivation (Baumeister and Leary 1995; deCharms 1968; Deci 1976; Ryan and Deci 2000; Reis et al. 2000).

Building on work that explores managerial motivation and its consequences for organizations, including expectancy-valence theory (Baumeister and Leary 1995; deCharms 1968; Deci 1976; Ryan and Deci 2000; Reis et al. 2000) and cognitive evaluation theory (Deci 1976; Ryan and Deci 2000), scholars have more recently coalesced around self-determination as a theoretically robust and empirically grounded construct. Gagné and Deci (2005) describe the variables of competence, relatedness, and autonomy as critical for human psychological development. Competence is the degree to which an individual perceives the ability to have an effect on his or her surroundings; relatedness is the degree to which individuals feel a connection with others in a particular context; and autonomy is an internally perceived locus of causality (Ryan and Deci 2000; Greguras and Diefendorff 2009). Environments that satisfy these three needs tend to foster individual psychological health, whereas environments that do not satisfy these needs tend to erode psychological health (Ryan and Deci 2000: 68).

Research in self-determination theory demonstrates that higher levels of self-determination tend to create favorable outcomes for organizations and individuals. As workers move toward intrinsic motivations (i.e., higher levels of self-determination), an array of outcomes follow: (1) constancy of changes in behavior; (2) higher performance, especially when tasks involve creativity, the ability to understand concepts, and flexibility in cognition; (3) greater job satisfaction; (4) better attitude toward work; (5) organizational citizenship behaviors; and (6) individual well-being and psychological adjustment (Gagné and Deci 2005: 337).

Research also has unpacked several interpersonal and relational factors that aid in increasing self-determination at work. For example, managers and corporations can influence the conditions that will support need satisfaction and lead to positive work outcomes (Baard 2002). Baard and Aridas (2001), in a study of church organizations, suggested that the most effective managers will be those that provide autonomy, competence, and relatedness supporting environments for their employees. These increases are supported by managerial behaviors such as providing a rationale for completing a task that was meaningful, validating the possibility that participants may find an activity uninteresting, and focusing on choice instead of control. These behaviors all tend to foster higher levels of self-determination (Gagné and Deci 2005: 338). Other factors such as communication, concern, empathy, and participation all tend to promote higher levels of self-determination (Gagné and Deci 2005: 339). Deci et al. (1989) found that managers’ interpersonal orientations, how supportive or controlling they were, effected self-determination for their subordinates. These insights non-withstanding, scholars in the self-determination field have called for more research in order to understand the organizational and contextual determinants of self-determination (Greguras and Diefendorff 2009; Sheldon et al. 2003; Johns 2006).

From Managing for Profits to Managing for Stakeholders

Corporations wield immense power in our global society. Therefore, some organizational scholars have argued that understanding the objectives of the corporation is the “most important theoretical and practical issue confronting us today” (Walsh 2004: 349).

In the late 1970s, a broad array of American companies adopted an approach to management that is generally referred to as “shareholder capitalism” (Dobbin and Zorn 2005). In general, this approach was built on the premise that the purpose of every corporation is to maximize its profits for shareholders (Friedman 1970; Jensen 2002; Fligstein and Shin 2004). This idea has its roots in over two centuries of economic theory and research (Jensen 2001; Berle and Means 1968). In the traditional operating model, corporations maximized value by attending to shareholder interests (Lan and Heracleous 2010). Because shareholder value is a function of corporate profits, this shareholder primacy tends to produce policies that help manage the “bottom line,” referring to financial profits (Jensen 2001). As a result, the goal of maximizing profits has been a strong driving force behind much of what has shaped 40 years of corporate policies, including compensation schemes, board composition, corporate financial policies, supplier contracts, corporate culture, customer management, and human resource management (Nyberg et al. 2010; Geletkanycz and Boyd 2011; Lan and Heracleous 2010; Dobbin and Zorn 2005). Not surprisingly, policies designed to maximize profits both through cutting costs and increasing revenue, impact the experiences of employees whose behavior is dictated by them (Werhane et al. 2008; Stout 2012).

Several scholars have made the case that stakeholder theory better captures how many organizations describe their corporate objective and run their operations (Freeman et al. 2010; Stout 2012). Stakeholders include those individuals and groups who can affect or are affected by the corporation—shareholders, customers, employees, suppliers, the community, governments, NGO’s, among others (Freeman 1984; Freeman et al. 2010). To effectively manage these interests, managers need to pay attention to a variety of factors above and beyond profits.

Evidence of this shift in practice can be found in the emergence of databases focused on value creation for non-financial stakeholders, such as the Kinder, Lydenberg, Domini Index (KLD) (Delmas et al. 2013), the rise of alternative accounting methods such as the Triple Bottom Line (Cronin et al. 2011), the popularity of published surveys like Fortune’s “Most Admired and Best Places to Work” (Anginer and Statman 2010), and “The Rise of Socially Responsible Investing in Mutual Funds” (Renneboog et al. 2011). Influential CEOs, who in the past have tended to extol their allegiance to shareholder-wealth maximization, are endorsing a stakeholder-based approach to managing for firm value. For example, Unilever CEO Paul Polman said when he took the job in 2010, “I do not work for the shareholder, to be honest; I work for the consumer, the customer…” (Stern 2010). A recent report from a survey of the Confederation of British Industry members found that most of them believed corporations would adopt a “more collaborative approach [than shareholder management]…with various different groups of stakeholders” (Economist2010). As former GE CEO Jack Welch recently observed, “Shareholder value is a result, not a strategy… Your main constituencies are your employees, your customers and your products” (Denning 2011). The stakeholder theorists assert that to maximize the value of the corporation, managers and corporate policy should focus on relationships with its stakeholders (Freeman et al. 2010). By tending to stakeholder needs and keeping them in balance, the firm will benefit from these stakeholders’ ongoing participation in the firm’s activities, and this will yield the maximum value of the firm in the future.

Theorists have debated the merits of these approaches and several hybrids along multiple dimensions including the level of legal precedent and support (Blair and Stout 1999; Stout 2012); the economic impacts and efficiency (Sundaram and Inkpen 2004; Jensen 2002); alignment of managerial incentives (Jensen and Murphy 1990); the issue of stakeholder heterogeneity and competing interests (Pirson and Malhotra 2011); and the amount of market options and legal protection afforded to various stakeholders (Lan and Heracleous 2010; Orts 1992, 1997). Although informative, these theoretical arguments miss the impact that the corporate objective can have on individuals in organizations (Harrison et al. 2010; McVea and Freeman 2005).

Recent research has demonstrated several benefits of a corporate objective framed around stakeholders rather than profits. De Luque et al. (2008) found that when a company’s leadership framed its purpose in terms of stakeholders rather than financial terms, employees were more likely to see the leaders as visionary and to exert more effort in their tasks, which led to measurable increases in firm performance. Corporate objectives shape and are shaped by culture (Pearce and David 1987; Swales and Rogers 1995; Bartkus et al. 2000); therefore, the effects of a corporate objective happen through culture. Jones Felps and Bigley (2007) argue that a firm’s stakeholder culture or the “beliefs, values, and practices that have evolved for solving stakeholder-related problems and otherwise managing relationships with stakeholders” will shape what kinds of stakeholders that employees are more likely to see as salient and thus shape managerial decision making. This growing body of research aims to tie a company’s objective to the behavior and decision making of managers. But missing from prior work is the impact on the psychological well-being of the individuals who are affected by the corporate objective, particularly employees whose work environment, goals, behaviors, and evaluations are framed by the corporate objective. Little scholarly attention thus far has been paid to the effect of the corporate objective on the well-being of stakeholders, including the psychological well-being of non-managerial employees.

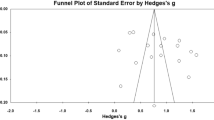

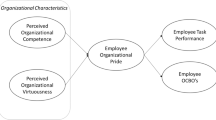

Therefore, in this paper, we will examine the effect of a stakeholder-focused corporate objective and a shareholder-focused corporate objective on employees’ level of self-determination at work (Hypotheses 1 and 2). Additionally, there are several elements of a stakeholder approach that theorists have argued could lead to benefits for employees. Hypothesis 3 posits that increases in self-determination are related to the shared values and purpose used to align stakeholder interests (Freeman et al. 2007). Hypothesis 4 presents the idea that the number of salient stakeholders increases managerial discretion and therefore self-determination (Sundaram and Inkpen 2004). Hypothesis 5 draws on evolutionary psychology to connect self-determination and the fact that human beings are wired to focus on other individuals and relationships rather than abstract artifacts such as profits (Walton et al. 2012; Haidt et al. 2008; Chudek and Henrich 2011) (Fig. 1).

How Corporate Objectives Impact Employees’ Psychological Need Satisfaction

The corporate objective shapes the cultural and decision-making context at a firm (Jones et al. 2007), and this context can either support or inhibit self-determination (Ryan and Deci 2000). Stakeholder- and shareholder-focused corporate objectives are not necessarily mutually exclusive because to make profits firms must pay attention to stakeholders and to address stakeholders’ concerns firms need profits (Freeman et al. 2007). These two perspectives are also not exhaustive of the various ways in which firms conceptualize their objective (Jones et al. 2007). Yet firms differ on which stakeholder concerns they make salient in their culture, through their communication, choice of objective and values, and structuring of incentives (Jones et al. 2007).

We hypothesize that the context created by a firm’s objective toward either profits or people (i.e., stakeholders) will likely impact employees’ sense of self-determination in several ways.

Autonomy

Managing for stakeholders allows corporate managers to devise their own strategies and permits considerably more latitude for managerial discretion than does managing to the financial bottom line (Marens and Wicks 1999; Berman et al. 2005). Whereas a shareholder-centric approach is focused on profits, a stakeholder management approach is much more open-ended. A stakeholder focus adds complexity to decision making by demanding that the individual considers a range of stakeholders, as opposed to only shareholders or profits (Freeman et al. 2004; Sundaram and Inkpen 2004). This choice of which stakeholder and outcomes to prioritize can affect employees on the front lines as well as executives through such diverse mechanisms as corporate policies, informal feedback, cultural expectations, and performance evaluations. For example, in a retail chain that values both profitability and customer satisfaction, a store clerk may have more discretion to accept returns from customers. Returns are not just a way to reduce sales and affect the bottom line, but also a way to increase customer satisfaction and loyalty. A stakeholder focus may not maximize discretion for all employees, but because there are multiple objectives for the firm as the number of salient stakeholders increase, employees at various levels will have more choice about how to frame their choices and thus how to act. Moving from a singular focus on profits to a broader focus on multiple stakeholders could impact the degree to which workers and managers have discretion over their decision making. A context that provides options for decisions creates more opportunities for individuals to feel in control of their work and to choose how to do it (Ryan and Deci 2000). Additionally, research in self-determination demonstrates that prosocial behaviors are related to autonomy and are more likely to be internalized, whereas a profit focus can feel externally imposed and lead to lower perceptions of autonomy (Ryan and Deci 2000).

Competence

A stakeholder-focused corporate objective encourages the active participation of a firm’s stakeholders over time, and the success of these relationships determines the financial fortunes of the firm. Therefore, the more that employees and managers can experience successful interactions with stakeholders, the more they will feel that they are effectively contributing to the firm’s success (e.g., Freeman 1994; Wicks et al. 1994).

A stakeholder focus encourages employees to understand, engage, and balance stakeholder interests, and if stakeholders need to be included in the process of decision making, then the individual judgment and choices of managers and employees gain more importance. Prior research provides some basis for this claim (de Luque et al. 2008; Ghoshal and Moran 1996; Cording et al. 2014), particularly for the notion that a stakeholder approach increases employee effort. For example, de Luque et al. (2008) analyzed survey responses from 520 firms in 17 countries to find that when CEOs emphasize stakeholder-oriented values (in contrast to economically oriented values), employees were more likely to perceive transformational leadership (rather than autocratic leadership) and therefore expend extra effort in their work, which predicted firm performance. Additionally, research on self-determination at work has established that “the experience of autonomy, competence, and relatedness improves employee satisfaction and autonomous motivation, which are themselves linked to retention and job performance” (Van Quaquebeke and Felps 2016: 14).

Additionally, interacting with people can provide richer multichannel feedback than focusing on abstractions such as numbers and metrics, which can take time to tabulate and disseminate. People’s emotions, body language, and verbal feedback are all cues that can signal whether an employee is doing something right or whether they can improve their approach; therefore, interacting with stakeholders rather than focusing on profits may provide richer feedback and thus increase perceptions of competence. Recent research has shown that connecting employees with the human beneficiaries of their work increases intrinsic motivation (Grant 2008). In contrast, profits are a lagging indicator (Kaplan and Norton 1996). Thus, the lag between an individual’s actions and the firm’s profits might be greater, and there may be a variety of intermediary causes that disrupt individuals’ perception that they can and do affect the bottom line.

Relatedness

Self-determination theory research provides empirical support for the idea that individuals have a fundamental psychological need to relate to others (Deci and Ryan 2011). Stakeholder theory, both in academic theory and in managerial practice, brings ethics, and more specifically, a concern for the human element to the fore of business and management (Donaldson and Preston 1995; Freeman et al. 2010; Jones and Wicks 1999). Stakeholder theory highlights the idea that all core stakeholders have intrinsic worth, that their concerns and interests should influence decision making alongside those of shareholders, and that they ought to have a voice in the process (Donaldson and Preston 1995; Freeman 1984; Jones and Wicks 1999). It also emphasizes the importance of creating and sustaining connections between the corporation and its stakeholders, not only as a good thing to do but as vital to the success and performance of the firm (e.g., Berman et al. 1999; Freeman 1994). Stakeholder firms have the ability to define a purpose or a set of shared values and goals that align stakeholder interests. For example, the purpose of Google is to “categorize the world’s information,” and the motto of Whole Foods, “Whole Foods, Whole People, Whole Planet,” captures the values that inspire and align their stakeholders. Stakeholder-oriented firms will tend to design work structures to provide opportunities for workers to connect with stakeholders to live and enact their corporate purpose, and to build meaningful relationships with the individuals who benefit from their efforts. Contact with the beneficiaries of their efforts has significant effects on employees’ sense of relatedness and self-determination (Grant et al. 2007; Grant 2008). Contact with stakeholders who share purpose and values will also increase perceptions of relatedness.

Several scholars have critiqued the shareholder primacy perspective for embracing an amoral view of business, putting profits above people, and emphasizing a mechanistic view of business in which the human element is downplayed or absent (Steinbeck 1939; Freeman 1994; Solomon 1992; Nelson 2010; Dobbin and Zorn 2005). Certainly, evidence suggests that a focus on profits could influence psychology in numerous ways that would inhibit feelings of relatedness and a connection between an individual’s work and the human beneficiaries of it. For example, the study of economics has been shown to make individuals focus more on the self and less on others (Frank et al. 1993), as has the study of accounting (Loeb 1991).

Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H1

The more a corporate objective emphasizes creating value for all stakeholders, the higher the self-determination of employees.

H2

The more a corporate objective emphasizes profits, the lower the self-determination of employees.

The increases in self-determination at work provided by a stakeholder-focused objective could be attributable to the fact that stakeholders can be seen as ends in and of themselves, rather than as means to profit maximization. A purpose-driven stakeholder objective is grounded in the idea that stakeholders have inherent worth and deserve consideration in the priorities and decision making of managers because they share the values and purpose of the firm (e.g., Donaldson and Preston 1995; Jones and Wicks 1999). By purpose, we mean the shared values and goals of the organization. For example, the stated purpose of Wal-Mart is to “help people save money and live better.” In a stakeholder-focused organization, the firm is free to choose a purpose that appeals to multiple stakeholders and catalyzes their cooperation and intrinsic motivation (Freeman et al. 2010). Increases in self-determination may be attributable to this non-financial purpose and its role in increasing stakeholder motivation. If this is true, then there should not be a similar increase in self-determination for firms that see stakeholders as relevant, not as ends in and of themselves, but rather as instrumental for maximizing profits. This is the case for both a shareholder-focused objective and an instrumental stakeholder objective (Jones 1995; Jones et al. 2007) that views a commitment to stakeholders as conditional and contingent on their role in creating value. In this view, stakeholders are seen as a means to the end of profit.

H3

A corporate objective that focuses on stakeholders’ shared purpose will be associated with higher levels of self-determination for employees than a corporate objective that focuses on the instrumental value of stakeholders.

In contrast to a shareholder approach that focuses managerial attention predominantly on financial metrics including profits, a stakeholder focus may allow managers more degrees of freedom in their decision making; they can choose which stakeholders to prioritize and how much attention to pay to them, and therefore there is increased autonomy for employees (Sundaram and Inkpen 2004; Jensen 2001). While stakeholder-focused firms see all stakeholders as legitimate, they are free to prioritize different groups based on their purpose or their impact on specific decisions (Jones et al. (2007); Freeman et al. 2010; Mitchell et al. 1997). Thus one source of increased self-determination may be the number of stakeholders and the different amounts of autonomy and freedom associated with having a single prominent stakeholder versus several salient stakeholders. If degrees of freedom matter in increasing self-determination, we would expect to see an increase in self-determination for employees as the number of salient stakeholder groups a company considers increases. Additionally, an increase in the number of stakeholders considered could increase opportunities for experiencing relatedness, and depending on the types of stakeholders recognized could increase the likelihood that any one employee’s skills and competence will be useful and recognized.

H4

As a corporate objective involves more stakeholders, employees will experience more self-determination at work.

The final mechanism suggested in the literature is the idea that a corporate objective based on a stakeholder approach directs attention to people and human beings, with names and faces, as the main beneficiaries of the organization’s activities (Freeman et al. 2010). A focus on shareholders, by contrast, tends to direct attention to non-human artifacts, like profits, as the purpose of work. Research in evolutionary psychology shows that human beings are wired to respond more positively to other people rather than to objects (Walton et al. 2012; Haidt et al. 2008; Chudek and Henrich 2011). Human evolutionary history has been heavily influenced by culture, and individuals have a basic biological instinct to connect with other people (Chudek and Henrich 2011). For this reason, we would expect that a corporate objective focused on people as the beneficiaries, as opposed to abstraction-like profits, would tend to highlight the human element of firm activities and therefore increase self-determination, particularly the relatedness aspect.

H5

A corporate objective that focuses on people will increase employee’s level of self-determination at work, relative to a corporate objective that focuses on profits.

Overview of Empirical Studies

In study 1, we conducted an experimental study to examine whether a stakeholder-focused corporate objective increased self-determination at work when compared to a shareholder-focused corporate objective. Although we found preliminary support for our hypothesized effect, in study 2, we assessed the external validity of our results. Specifically, in study 2, we conducted an online survey and asked participants about their current work and their current company’s focus on creating value for all stakeholders or increasing profits. The results of study 2 supported our initial findings. In studies 3–5, we aimed to understand better the specific elements through which corporate objectives influence self-determination: Study 3 examined whether the differences in self-determination at work are due to the role of purpose provided by a stakeholder-focused approach, or to the instrumental attention to stakeholders as a means of increasing profits. We find these manipulations only work in specific situations such as a side-by-side comparison. Study 4 examined whether the increase in self-determination at work was due to the amount of decision-making discretion gained as the number of stakeholders increased. Again, the number of stakeholders only increases self-determination under a side-by-side comparison. Study 5 examined the idea that people respond differently to other human beings versus abstract artifacts like profits and was supported by our data.

Study 1

Participants

One hundred and thirteen participants solicited from Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk)Footnote 1 (56% Male, Average Age = 30.53, SD = 10.91) participated in this study. Participant answers were excluded from this data set if (1) they did not complete the study, (2) they failed the attention checks embedded in the study, and (3) their elapsed time in the study was more than one standard deviation below the mean for the study indicating that they sped through the questions. MTurk participants were from a broad spectrum of industries and types of work and therefore provided an ideal sample from which to start to understand how a company’s objective can impact a broad sample of employees’ level of self-determination at work.

Procedure

To begin testing H1 and H2, we used a basic between-subjects designs to examine the effects of priming a stakeholder or shareholder-focused objective on an individual’s expected self-determination at work. Participants read a vignette of a stakeholder-focused company or a profit-focused company and then answered the 21-item self-determination at work scale (Ilardi et al. 1993; Kasser et al. 1992; Rosen et al. 2014) as if they had worked at the company portrayed in the vignette.

After agreeing to complete the study and accepting the IRB agreement, participants were asked to read one of two randomly assigned vignettes about a company. In the stakeholder condition, the vignette read:

You are a manager at a large multi-national company that manufactures electronic devices that are sold directly to customers. Your company emphasizes the importance of making all stakeholders (including employees, customers, suppliers, shareholders, and the larger community) better off in the long term. These criteria are part of annual individual performance evaluations, as well as the larger culture of the company. The CEO regularly highlights the importance of creating value for stakeholders in his internal and external communication.

In the shareholder condition the vignette read:

You are a manager at a large multi-national company that manufactures electronic devices that are sold directly to customers. Your company emphasizes the importance of making as much money as possible. Profitability is a key part of annual individual performance evaluations, as well as the larger culture of the company. The CEO regularly highlights the importance of making money for shareholders in his internal and external communication.

The two messages were identical except for the overall purpose of the company.

Unless otherwise indicated, all items were conducted on a 7-point Likert scale, where 1 = Strongly Disagree and 7 = Strongly Agree. Our dependent variable was the level of self-determination at work, measured by the self-determination at work scale (Ilardi et al. 1993; Kasser et al. 1992), which has 21 items that measure three properties of self-determination: autonomy (Cronbach’s α = 0.84), relatedness (Cronbach’s α = 0.87), and competence (Cronbach’s α = 0.71). Participants were asked to imagine that they worked at the company they read about and to answer the questions as if they worked at the company. See Appendices 1, 2 for full scale.

Results

Supporting our manipulation, an independent samples t test showed that participants in the stakeholder condition demonstrated a statistically significant increase in all three components of self-determination at work (see Fig. 2). Participants in the shareholder condition exhibited significantly less autonomy (M = 3.18, SD = 1.16) than the stakeholder condition (M = 4.43, SD = 0.87, t(111) = 6.48, p < .0001, d = 0.193). Participants in the shareholder condition (M = 3.94, SD = 1.07) exhibited less relatedness than the stakeholder condition (M = 4.86, SD = 0.92, t(111) = 4.90, p < .0001, d = 0.118), and finally, participants in the shareholder condition (M = 4.22, SD = 0.97) exhibited less competence than the stakeholder condition (M = 5.11, SD = 0.79, t(111) = 5.35, p < .0001, d = 0.166).

Study 1 Discussion

These initial results provide support that firm-level characteristics such as a corporate objective focused on stakeholders or shareholders do impact the amount of self-determination of individuals who work at that company, and that a stakeholder-focused objective increases self-determination at work across all three components of self-determination theory. This study raises two additional questions, which we seek to answer in study 2. First, these results, while compelling, do not allow us to assess the relative effects of a stakeholder- and shareholder-focused objective, specifically whether a stakeholder-focused objective increases self-determination as argued in H1, or whether a shareholder-focused objective decreases self-determination as argued in H2. Second, a controlled laboratory study such as study 1 can verify the presence of a causal effect but cannot speak to the external validity of that effect. In the second study, we set out to examine individuals’ level of self-determination in their real jobs and its relationship to their actual company’s objective.

Study 2

Participants

We recruited 201 MTurk participants (64% Male, Average Age = 35.02, SD = 10.99). The same criteria used in study 1 were used to delete incomplete responses from the data set. Each of the studies in the paper was conducted several weeks apart, and we screened out participants from previous studies so that each study contained unique participants. For study 2 we screened for participants who had been employed at a for-profit company for at least one year.

Measures and Procedure

We designed an online survey to measure the individuals’ current level of self-determination at work and also asked participants to report their perceived level of shareholder and stakeholder focus for their current employer. This design allowed us to independently assess the effects of each corporate objective, as well as to establish the external validity of the findings in study 1.

To avoid any priming and to provide a conservative test of our hypothesis, participants were first asked to think about their current job and fill out the self-determination at work scale (Ilardi et al. 1993; Kasser et al. 1992), just as in study 1. Autonomy (Cronbach’s α = .81), competence (Cronbach’s α = .72), relatedness (Cronbach’s α = .85). Additionally, recent meta-analyses (Van den Broeck et al. 2016) have argued that each psychological need explains unique variance and therefore should not be averaged into a single self-determination score. We confirmed that finding by running a confirmatory factor analysis. The results of a confirmatory factor analyses on Mplus 7.4 revealed that a three-factor structure (autonomy, competence, and relatedness) yielded acceptable fit to our data (χ2 = 191.92, df = 24, RMSEA = .17, CFI = .85, TLI = .77). Chi-square difference tests showed that an alternative nested model with a single factor achieved a significantly poorer fit (χ2 = 230.78, df = 27, RMSEA = .18, CFI = .82, TLI = .76) (Δχ2 = 38.86, df = 3, p < .01). Thus, although the individual measures were highly correlated as expected, these analyses provided support for the proposed three-factor structure.

Afterward, we asked participants to measure the degree of their company’s focus on shareholders by asking them how much they agreed with the following statements: (1) I believe that my organization values profits above all else, (2) My organization predominantly emphasizes the bottom line, (3) Leaders in my organization care predominantly about profits, and (4) To perform my role well I need to focus on increasing profits. Then we asked the participants whether they agreed with the following four statements to measure their perception of their company’s stakeholder focus: (1) I believe my organization cares about multiple-stakeholder groups including employees, customers, suppliers, the community, and shareholders/lenders, (2) My organization emphasizes more than the bottom line, (3) Leaders in my organization care about a broad group of stakeholders, and (4) To perform my role well I need to focus on more than the bottom line. The average of the four responses to the profit-focused statements was our measure of perceived profit focus (Cronbach’s α = 0.814), and the average of the four responses to the stakeholder-focused statements was our measure of perceived stakeholder focus (Cronbach’s α = 0.798).

Age, gender, and tenure have been shown to influence how employees experience their work (Bowen et al. 2000; Rosen et al. 2014). Therefore, these variables are regularly included as controls in studies examining discretionary behaviors. We asked participants how long they had been with their current employers and how much cumulative work experience they had. The average company experience was 3.39 years, SD = 1.48, and the average cumulative work experience was 5.56, SD = 1.84. Participants were drawn from a broad pool of industries including but not limited to professional, scientific, or technical services (14%), financial services (10%), information services (9%), manufacturing (9%), educational services (9%), retail trade (8%), and health care (6%). In light of research’s methodological best practice (Aguinis and Bradley 2014; Becker 2005), we have also run our regressions without controls to demonstrate the strength of the relationship.

Results

Table 1 depicts the descriptive statistics and correlations between variables used in this study. The correlations between the self-determination variables are in line with previously published research as field studies indicate that the three components covary to a high degree in natural settings (Rosen et al. 2014). Interestingly, there was a small significant negative correlation between the reported stakeholder focus and profit focus for a firm (−0.189, p < 0.001).

We subsequently ran three regression models, using each of the self-determination variables as the dependent variable and the individual’s reported company profit focus, stakeholder focus, as well as their years of experience at the company, and total years of experience as independent variables. Table 2 reports the outcomes of these regressions. As predicted, a profit focus had a negative effect on all three dimensions of self-determination: autonomy β = −0.276, p < .000, competence β = −0.111, p = .082, relatedness β = −0.214, p = .001, and an increased stakeholder focus increased self-determination even when controlling for profit focus, autonomy β = 0.514, p < .000, competence β = 0.403, p < .000, relatedness β = 0.344, p < .000.

Study 2 Discussion

Study 2 elaborated on the findings of study 1 and demonstrated that the effects observed in the laboratory also have external validity. Additionally, study 2 confirmed both H1 and H2 by showing that a corporate objective focused on stakeholders is related to increases in self-determination, and a corporate objective focused on shareholders is related to decreased self-determination, even while controlling for the other effect. Having preliminarily supported H1 and H2 with a correlational study and a randomly assigned controlled laboratory study, we set out to better understand which specific elements of a stakeholder focus increase self-determination at work. In the subsequent studies, we tested three hypotheses offered in the literature to see which one was more likely to drive the significant effects observed in studies 1 and 2.

Study 3

Participants

One hundred and forty-eight participants solicited from MTurk (60% Male, Average Age = 29, SD = 8.12) participated in this study. The same criteria for study 1 were used to exclude participant responses from the data set.

Procedure

To further explore whether a stakeholder-oriented objective increases self-determination at work because of the instrumental involvement of stakeholders or because of some inspiring purpose, we created a between-subjects design with three conditions: (1) a purpose-driven condition, (2) an instrumental stakeholder condition, and (3) a shareholder condition. Each of these manipulations is an ideal type that falls along the continuum of a stakeholder culture identified by Jones et al. (2007).

The shareholder condition read:

You are a manager at a multinational pharmaceutical company. Your company emphasizes the importance of making as much money as possible. Profitability is a key part of annual individual performance evaluations, as well as the larger culture of the company. The CEO regularly highlights the importance of making money for shareholders in his internal and external communication.

The purpose-driven condition read:

You are a manager at a multinational pharmaceutical company. Your company emphasizes the importance of “Creating medicines to help people live better lives.” These criteria are part of annual individual performance evaluations, as well as the larger culture of the company. The CEO regularly highlights the importance of the company’s mission in his internal and external communication.

And the instrumental stakeholder condition read:

You are a manager at a multinational pharmaceutical company. Your company emphasizes the importance of long-term success. Sustainable profits are made by focusing on the needs of stakeholders (including employees, customers, suppliers, shareholders, and the larger community) and making them better off in the long term. These criteria are part of annual individual performance evaluations, as well as the larger culture of the company. The CEO regularly highlights the importance of profitability through stakeholder engagement in his internal and external communication.

Again we measured self-determination at work using the same scale as studies 1 and 2 (Ilardi et al. 1993), autonomy (Cronbach’s α = 0.84), relatedness (Cronbach’s α = 0.85), and competence (Cronbach’s α = 0.82).

Results

The results are depicted in Fig. 3. An independent samples t test confirmed that there were no significant differences between the purpose-driven and instrumental stakeholder conditions in any of the three self-determination variables. For the purpose-driven condition the mean for autonomy was M = 4.41, and SD = 0.81, whereas the instrumental stakeholder condition had a mean of M = 4.18, and a SD = 0.97, thus, t(94) = 1.23, p = 0.222, d = 0.22. Similarly, for competence the purpose-driven condition mean was M = 5.13, SD = 0.82, and the instrumental stakeholder condition mean was M = 5.04, SD = 0.99, thus, t(94) = 0.518, p = 0.605, d = 0.09. Finally, for relatedness the purpose-driven condition mean was M = 4.82, SD = 0.76 and the mean for the instrumental stakeholder condition was: M = 4.93, SD = 0.88, t(94) = −0.667, p = 0.506, d = −0.118.

Both the stakeholder conditions (purpose-driven and instrumental) were significantly different from the profit-driven condition. Table 3 depicts the means and standard deviations for each of the three conditions:

Study 3 did not support H3 despite the fact that this distinction is important in theory (Jones 1995; Freeman et al. 2004; Parmar et al. 2010). Therefore, to better understand the context of our findings, we ran a follow-up study using the same procedure and increased the strength of our manipulation.

Participants

In study 3b, 145 participants (61% Male, Average Age = 28.6, SD = 9.11) were recruited from MTurk.

Procedure

Participants read both the purpose-driven and instrumental stakeholder conditions to compare the conditions, were randomly assigned to one of those conditions, asked to imagine they worked at that company, and answered the self-determination at work scale. Side-by-side comparisons have been demonstrated to heighten the effect of a manipulation (Tversky et al. 1988; Hsee et al. 1999), and, more importantly, they more accurately resembled the comparisons that theorists make when they evaluate corporate objectives.

Results

The results show that when participants were allowed to compare a purpose-driven and an instrumental stakeholder focus, there were significant increases for self-determination in the purpose-driven condition (see Fig. 4).

For the purpose-driven condition, the mean for autonomy was M = 4.67, and SD = 0.84, whereas the instrumental stakeholder condition had a mean of M = 3.53, and SD = 1.11, thus, t(144) = 7.05, p < 0.0001, d = 0.163. Similarly, for competence, the purpose-driven condition mean was M = 5.14, SD = 0.84, and the instrumental stakeholder condition mean was M = 4.40, SD = 0.94, thus, t(144) = 4.98, p < 0.0001, d = 0.149. Finally, for relatedness, the purpose-driven condition mean was M = 4.97, SD = 0.86; the mean for the instrumental stakeholder condition was M = 4.02, SD = 1.07, t(144) = 6.01, p < 0.0001, d = 0.158. Therefore, H3 was supported only in the context of a side-by-side comparison.

Study 3 (a and b) Discussion

Study 3b demonstrates that when the manipulation was made more salient, as participants were allowed to compare across vignettes, an increase in self-determination resulted for a purpose-driven corporate objective relative to an instrumental stakeholder objective. This finding puts current theoretical arguments into perspective by demonstrating that a purpose-driven firm can best reap the benefits of its objective function (relative to an instrumental stakeholder company) when employees compare it to other less purpose-driven companies. The idea that a purpose-driven approach directly increases in self-determination above and beyond an instrumental approach was not supported by our data (study 3a) but only when participants compared the two companies side by side. Theorists who have argued for the strengths and weaknesses of each approach have been making side-by-side comparisons, but that may not reflect what employees experience at work. Thus to understand the source of direct increases in self-determination for a corporate objective focused on stakeholders, we turned our attention to a second argument presented in the stakeholder/shareholder literature: the amount of managerial discretion allowed by stakeholder theory.

Study 4

Participants

One hundred and twenty-four participants solicited from MTurk (52% Male, Average Age = 29.70, SD = 9.08) participated in this study. The same criteria for study 1 were used to exclude participant responses from the data set.

Procedure

In study 4, we created a between-subjects design with two conditions. The first had a single stakeholder (customers), and the second had two stakeholders (customers and suppliers). If increased discretion is partially responsible for increases in self-determination, then we should have observed more self-determination in the multiple-stakeholder condition than in the single-stakeholder condition. We chose these groups because they were both external to the firm (Pirson and Malhotra 2011), whereas internal stakeholders such as employees might have been easier for participants (in the role of employees) to empathize with, and thus, participants might overstate their level of self-determination. Because we excluded employees in these conditions, we also hoped to verify that increases in self-determination are not totally dependent on employees’ perception that they are more likely to be considered in a stakeholder-focused firm.

In the single-stakeholder condition, the participants read:

You are a manager at a large multi-national company that manufactures electronic devices that are sold directly to customers. Your company emphasizes the importance of making customers happy. Customer satisfaction is a key part of annual individual performance evaluations, as well as the larger culture of the company. The CEO regularly highlights the importance of customer satisfaction in his internal and external communication.

In the multiple-stakeholder condition, participants read:

You are a manager at a large multi-national company that manufactures electronic devices that are sold directly to customers. Your company emphasizes the importance of serving customer and suppliers. Customer and supplier satisfaction are part of annual individual performance evaluations, as well as the larger culture of the company. The CEO regularly highlights the importance of creating value for suppliers and customers in his internal and external communication.

Once again, we measured this using the self-determination at work scale: autonomy (Cronbach’s α = 0.65), relatedness (Cronbach’s α = 0.70), and competence (Cronbach’s α = 0.56).

Results

Figure 4 depicts the results from study 4. An independent samples t test showed that there were no significant differences between the single- and multiple-stakeholder conditions. For the single-stakeholder condition, the mean was M = 4.25, SD 1.06; for the multiple-stakeholder condition, the mean was M = 4.39, SD = 0.87, thus t(121) = −0.778, p = 0.438, d = −0.141. For competence, the single-stakeholder mean was M = 5.07, SD = 0.89, and the multiple-stakeholder mean was M = 5.21, SD = 0.89, therefore t(121) = −0.841, p = 0.402, d = −0.139. Finally the mean for the single-stakeholder condition for relatedness was M = 4.93, SD = 0.83, and the mean for the multiple-stakeholder group was M = 4.95, SD = 0.81, therefore, t(121) = −0.090, p = 0.929, d = −0.0137. While these means were statistically indistinguishable, they were both in line with the stakeholder means reported in study 3 and therefore also statistically different from the shareholder means in that study (Fig. 5).

With no direct effects observed for the number of stakeholders, we again tried to understand the context of our finding, because of the importance of these arguments in theory (Sundaram and Inkpen 2004).

Participants

One hundred participants (66% Male, Average Age = 30.0, SD = 8.) participated in study 4b.

Procedure

We strengthened our manipulation in study 4b and allowed participants to again compare both conditions (Tversky et al. 1988; Hsee et al. 1999) and then randomly assigned them to one of the conditions and asked them to fill out the self-determination at work questionnaire.

Results

As in study 3, the ability to compare across companies led to significant results. For the single-stakeholder condition, the mean for autonomy was M = 3.73 and SD = 0.96, whereas the multiple-stakeholder condition had a mean of M = 4.79, and a SD = 0.77, thus, t(98) = 6.03, p < 0.0001, d = 0.174. Similarly, for competence, the single-stakeholder condition mean was M = 4.40, SD = 0.85, and the multiple-stakeholder condition mean was M = 5.27, SD = 0.78, thus, t(98) = 5.33, p < 0.0001, d = 0.163. Finally, for relatedness, the single-stakeholder condition mean was M = 4.23, SD = 0.78; the mean for the multiple-stakeholder condition was: M = 5.15, SD = 0.81, t(98) = 5.79, p < 0.0001, d = 0.159. Therefore, once again, when presented with both conditions in a side-by-side comparison, the theoretical argument held up, and the multiple-stakeholder condition demonstrated an increase in self-determination (see Fig. 6).

Study 4 (a and b) Discussion

In study 4a, we found that increasing the number of stakeholders did not have a significant direct effect on self-determination at work when presented without a side-by-side comparison. Our study 4b shows that only when participants were allowed to compare both conditions and were randomly assigned to one, did we find a significant effect for the multiple-stakeholder condition even though employees were not included as one of the salient stakeholder groups.

Study 5

Participants

One hundred participants solicited from MTurk (58%, Male, Average Age = 29.86, SD = 7.99) participated in this study.

Procedures

To test this idea, we created two conditions, a profit condition and a people condition. The profit condition was the same vignette used in the previous studies:

You are a manager at a large multi-national company that manufactures electronic devices that are sold directly to customers. Your company emphasizes the importance of making as much money as possible. Profitability is a key part of annual individual performance evaluations, as well as the larger culture of the company. The CEO regularly highlights the importance of making money for shareholders in his internal and external communication.

Whereas the people condition read:

You are a manager at a large multi-national company that manufactures electronic devices that are sold directly to customers. Your company emphasizes the importance of people. Criteria that measure satisfaction of different groups are part of annual individual performance evaluations, as well as the larger culture of the company. The CEO regularly highlights the importance of people in his internal and external communication.

We measured this using the self-determination at work scale: autonomy (Cronbach’s α = 0.86), relatedness (Cronbach’s α = 0.82), and competence (Cronbach’s α = 0.71).

Results

An independent sample t test confirmed that a focus on people versus profits directly impacted on reported self-determination at work. The autonomy mean for the profit condition was M = 3.21, SD = 1.13, whereas the mean for the people condition was M = 4.62, SD = 0.91, thus, t(98) = 6.91, p < .0001, d = 1.42. The competence mean for the profit condition was M = 4.23, SD = 0.866, and the people mean was M = 5.05, SD = 0.89, therefore t(98) = 4.66, p < .0001, d = 0.822. Finally, the relatedness mean for the profit group was M = 3.99, SD = 0.80, and the mean for the people condition was M = 4.98, SD = 0.89, therefore, t(98) = 5.85, p < .0001, d = 0.995 (Fig. 7).

Study 5 Discussion

Given the similarity between these results and the results in study 1, we suspect that the main reason that stakeholder focus increases self-determination is that it primes individuals to think about people, rather than profits. While study 5 does not provide causal evidence, it does show that the difference in the people and profit condition was a little stronger and in the same direction as study 1. It is difficult conceptually to create a non-people-oriented stakeholder condition, and people-oriented profit condition, to provide causal evidence of this mechanism. The results suggest that a primary source of increased self-determination at work comes from focusing the attention of employees on people rather than on profits.

General Discussion

This research establishes that there are tangible differences for employee psychological well-being that are attributable to the nature of the corporate objective. Scholars have made extensive claims about how their respective theories will affect managers and various stakeholders (Freeman et al. 2004; Jensen 2002; Sundaram and Inkpen 2004), yet surprisingly little work has been devoted to exploring and testing these claims empirically. We offer empirical results that provide new directions on heated theoretical debates around the purpose of the corporation. Importantly, we add a new dimension to prior conversations. While the potential effects that a corporate objective may have on behavior—through culture, compensation, and decision-making norms—have been noted in other areas of the literature, scholarly arguments regarding the purpose of the organization have yet to systematically explore the psychological consequences that a particular focus might have on employees or other firm stakeholders. The present study demonstrates that such investigation is timely, appropriate, and would likely reveal additional empirically significant differences between the psychological consequences of a shareholder- and a stakeholder-focused objective.

Study 1 demonstrated an increase of between 17% and 33% of self-determination at work for a corporate objective focused on stakeholders compared to one focused on profits. Study 2 provided external validity and supported both H1 and H2 by demonstrating simultaneously an increase in self-determination for a corporate objective focused on stakeholders and a decrease in self-determination for a corporate objective focused on profits and shareholders across all three variables: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. In studies 3 through 5, we tested the impact of three theoretical mechanisms to explain this differential impact. We did not find evidence to support H3, which suggests that a purpose-driven or instrumental stakeholder approach differed in the level of self-determination, or H4, which suggests that the number of stakeholders impacted self-determination. In studies 3b and 4b, we found effects supporting H3 and H4 only when participants were allowed to compare these options side by side. We did find support for H5 that stakeholder theory’s focus on people rather than profits had positive effects on self-determination. Thus we extend the debates about the corporate objective by going beyond theoretical arguments to empirically assess the impact of various corporate objectives on the psychological well-being of employees.

In this paper, we make a number of contributions to the literature. First, we develop new theory, specifically identifying important new directions in the ongoing conversation comparing stakeholder theory and shareholder theory and identifying new ways to compare their relative merits and implications for firms (Freeman et al. 2010; Harrison and Wicks 2012). The hypotheses developed in this paper provide a theoretical rationale for how both stakeholder and shareholder theories differentially impact the psychological needs of employee stakeholders. Through our studies, we find empirical support for the claim that stakeholder theory is better able to meet the psychological needs of employees, and we uncover the most likely underlying mechanism to explain our findings. Much of the existing debate has been driven by academics focused on comparisons at the level of ideas that make assumptions about implications for managers (Sundaram and Inkpen 2004; Freeman et al. 2004; Jensen 2002). The present study moves beyond such debates and actually tests the effects of these ideas and how they inform stakeholder behavior.

Second, our paper moves forward efforts to better understand (and measure) the value that stakeholders seek in their collaboration with firms and other stakeholders. Previous work highlights the premise that value creation is an important topic for theoretical exploration and something that stakeholders seek (Parmar et al. 2010; Harrison and Wicks 2012). Not only do our studies provide support for the idea that stakeholder theory is more likely to meet the psychological needs of employees, but it focuses on forms of value often overlooked in the extant literature, namely, non-economic value (Freeman et al. 2010). While our study shows a tangible difference in terms of a non-economic factor, the existing literature on self-determination highlights the idea that meeting the psychological needs of employees better has an array of different behavioral implications that could lead to financial benefits for firms (e.g., through extra effort, greater levels of engagement, and expanded strategic capabilities) (see Bosse et al. 2009; Harrison et al. 2010).

Third, our study provides important new directions to bridge both stakeholder theory and micro-OB theories, particularly noting connections between the two fields that have largely been overlooked to date. While there is a vast amount of growing literature on self-determination (Deci and Ryan 1985; Ryan and Deci 2000), there is a dearth of work that examines the role of firm purpose and other organizational-level variables on self-determination. We answer calls from self-determination researchers to unpack these organization-level factors (Greguras and Diefendorff 2009; Sheldon et al. 2003). In the present paper, we demonstrate that not only is there an effect, but that its magnitude is notable and should be of interest to scholars trying to better understand micro-organizational behavior-level theory such as self-determination. At the same time, despite stakeholder theory being framed as interdisciplinary (Freeman et al. 2010), stakeholder-theory scholars have overlooked the ways in which micro-organizational behavior phenomena may well be an important proving ground for their ideas and highlight the significance these theories have for both individual stakeholders and firms. Further efforts to combine these literatures, and examine the interplay of macro- and micro-level theories, may well lead to important new insights that enrich the management literature and generate insights that are highly relevant to management practice.

Fourth, our study has implications for companies that care about employees and want to foster their well-being at work, as well as for those organizations that might want to benefit from the associated behaviors that often follow from higher levels of self-determination. We show that managers, who focus on stakeholders and people, rather than solely on shareholders and profits, are more likely to meet the psychological needs of employees and elevate their levels of self-determination. While there is clearly more work to be done to tease out precisely how best to accomplish this—mixing language with behaviors that demonstrate commitment to these ideals and finding practices that fit the context and objectives of a given firm and employees—our results cast light on critical issues that have vexed organizational scholars for decades through the debates between stakeholder and shareholder theorists about how to value both mission and efficiency, purpose and marketplace success, people and profits. While both of these factors could be essential to organizational survival and success, our results show that language highlighting a focus on profits dehumanizes business, decreases self-determination, and could (as a result) foster weakened marketplace performance. In contrast, a focus on stakeholders humanizes business, enhances employee self-determination, and could well lead to better financial returns.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our studies are a first step in understanding how a corporate objective shapes employee well-being at work. There are several next steps to further flesh out this research. First, our studies treat employees as one group of people. Future studies could further examine how these processes play out at different levels within the organization. For example, while we did not find an effect for the employees’ length of stay at a company, it might be that organizational status, which we did not measure, is a factor. There could be differences between workers and managers in how they are affected by a corporate objective. Future research should examine a range of factors, such as an individual’s work role, education, job title, salary, department, and so forth to explore how they might impact the relationships we observed. Subsequent research has the opportunity to further unpack the relative effect size of the corporate objective on self-determination in relation to other variables that have already been studied, such as the interpersonal relationship with managers (Gagné and Deci 2005).

Future research could also explore how other stakeholder groups in addition to employees might be impacted by the corporate objective. Such research need not be tied to theories like self-determination, but if the intuitions of scholars who have argued about the significance of the corporate objective are correct, and our results demonstrate a behavioral impact of such objectives on stakeholder behaviors, then further work both with employees and other stakeholders is key. Indeed, given the importance of stakeholder commitment to enabling and sustaining firm strategy, such studies would appear to be highly relevant and potentially illuminating to discussions on the theoretical merits of corporate objectives as well as to their practical effects.

In studies 3b and 4b, we employed a side-by-side comparison approach (Tversky et al. 1988) to understand how participants thought about different corporate objectives. This approach mirrors reality in the sense that employees know their own company’s objectives and can compare to them to the objectives of other firms they encounter. Even though participants had the opportunity to show ambivalence and give similar ratings to both objectives, the side-by-side comparison method could also signal to participants that there should be a different rating and therefore increase the variance demonstrated. Subsequent studies can control for this effect by employing different methods to understand corporate objectives’ effects on need satisfaction. For example, methods such as qualitative coding of interviews where employees discuss their corporate objective (Miles and Huberman 1994) can allow employees’ interpretation to be unfiltered; methods such as conjoint analysis (Green and Srinivasan 1978), and factorial vignette studies (Jasso 2006) that manipulate a variety of factors to assess the impact on a single dependent variable, provide add additional factors that may remove bias and add important new study controls.

Additionally, the aim of this paper was to establish that differences exist in the levels of employee psychological well-being for different corporate objectives. Our goal is not to map perfectly the differences and subtleties in practice, but to better understand the psychological impact of the ideal types provided by theory. Firms differ on whether they place their emphasis on one or many stakeholders. Indeed, employees sampled in study 2 demonstrated a small but negative correlation (−0.19, p < 0.05) between these two approaches when describing their own companies, which suggests that actual firms highlight one of these objectives while having both. Future research can further distinguish types of profit orientation or specific hybrids of stakeholder and shareholder objectives in companies as well as the impact of these objectives and their resulting level of need satisfaction on profits. Existing work demonstrates that profitability can be improved through increased autonomy, specifically by reduced turnover and increased organizational citizenship behaviors (Dubreuil et al. 2014).

Future research can more systematically examine individual-level differences such as prosocial personality (Penner et al. 1995) or moral attentiveness (Reynolds 2008), which may moderate the effects we observed. Future research may show that, for example, taking individual prosocial personality into account could help explain some of the results we observed, and provide some indication that individuals are more or less impacted by the corporate objective. Individuals who are more prosocially oriented may likely feel more self-determined in a stakeholder-focused firm than a shareholder-focused firm, whereas individuals who are less prosocially oriented might be less impacted by these features.

Conclusion

Theorists have been debating the strengths and weaknesses of a corporate objective focused on stakeholders or shareholders for decades. We examine the impact of these different objectives on employee psychological well-being, specifically their level of self-determination at work. Through four laboratory studies and one online survey, we show that an approach framed in the language of stakeholder theory increases autonomy, relatedness, and competence. Our findings suggest that a corporate objective that is focused on creating value for multiple stakeholders is likely to make employees more psychologically satisfied. While this does not mean they will perform better in all circumstances, it is likely to lead to tangible benefits for the firm. Given that previous research has linked self-determination to positive individual- and organizational-outcome variables, it is possible that a corporate objective focused on creating value for stakeholders will have an appreciable impact on firm performance, albeit firm performance may be measured differently in firms that are more stakeholder-oriented. Perhaps most importantly, we have added a new approach with which future scholars can pursue questions around the purpose of the corporation and, hopefully, inform a vision for the purpose of the corporation that satisfies both financial and psychological needs of its stakeholders.

Notes

Researchers have evaluated MTurk for the quality of data and compared it to other platforms. They have concluded that MTurk samples are more representative of the US population than in-person convenience samples (Mason and Suri 2012) and that MTurk results demonstrate internal and external validity (Berinsky et al. 2012; Horton et al. 2011). Research has demonstrated that the data obtained are at least as reliable as those obtained via traditional methods (Buhrmester et al. 2011).

References

Aguinis, H., & Bradley, K. J. (2014). Best practice recommendations for designing and implementing experimental vignette methodology studies. Organizational Research Methods, 17(4), 351–371.

Amabile, T. M. (1983). The social psychology of creativity (Vol. 11). New York: Springer.

Anginer, D., & Statman, M. (2010). Stocks of admired and spurned companies. The Journal of Portfolio Management, 36(3), 71–77.

Baard, P. P. (2002). Intrinsic need satisfaction in organizations: A motivational basis of success in for-profit and not-for-profit settings. In: E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 255–275). University Rochester Press.

Baard, P. P., & Aridas, C. (2001). Motivating your church: How any leader can ignite intrinsic motivation and growth. New York: Crossroad Publishing Company.

Baard, P. P., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2004). Intrinsic need satisfaction: A motivational basis of performance and weil-being in two work settings. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(10), 2045–2068.

Barnard, C. I. (1968). The functions of the executive (Vol. 11). Harvard university press.

Bartkus, B., Glassman, M., & McAfee, B. R. (2000). Mission statements: Are they smoke and mirrors? Business Horizons, 43(6), 23–28.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for Interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497.

Becker, T. E. (2005). Potential problems in the statistical control of variables in organizational research: A qualitative analysis with recommendations. Organizational Research Methods, 8(3), 274–289.

Berinsky, A. J., Huber, G. A., & Lenz, G. S. (2012). Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk. Political Analysis, 20(3), 351–368.

Berle, A., & Means, G. (1968). The modern corporation and private property, 1932. New York, NY: McMillan.

Berman, S. L., Phillips, R. A., & Wicks, A. C. (2005). Resource dependence, managerial discretion and stakeholder performance. In: Academy of management proceedings (Vol. 2005, No. 1, pp. B1–B6). Briarcliff Manor: Academy of Management.

Berman, S. L., Wicks, A. C., Kotha, S., & Jones, T. M. (1999). Does stakeholder orientation matter? The relationship between stakeholder management models and firm financial performance. Academy of Management Journal, 42(5), 488–506.

Blair, M. M., & Stout, L. A. (1999). A team production theory of corporate law. Virginia Law Review, 85(2), 247–328.

Bosse, D. A., Phillips, R. A., & Harrison, J. S. (2009). Stakeholders, reciprocity, and firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 30(4), 447–456.

Bowen, C. C., Swim, J. K., & Jacobs, R. R. (2000). Evaluating gender biases on actual job performance of real people: A meta analysis. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30(10), 2194–2215.

Bradley, M., Schipani, C. A., SundaramJ, A. K., & Walsh, P. (1999). The purposes and accountability of the corporation in contemporary society: Corporate governance at a crossroads. Law Contemporary Problems, 62(3), 9–86.

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. D. (2011). Amazon’s Mechanical Turk a new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 3–5.

Chudek, M., & Henrich, J. (2011). Culture–gene coevolution, norm-psychology and the emergence of human prosociality. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15(5), 218–226.

Cording, M., Harrison, J., Hoskisson, R., & Jonsen, K. (2014). “Walking the talk”: A multi-stakeholder exploration of organizational authenticity, employee productivity & post-merger performance. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 28(1), 38–56.

Cronin, J. J., Jr., Smith, J. S., Gleim, M. R., Ramirez, E., & Martinez, J. D. (2011). Green marketing strategies: An examination of stakeholders and the opportunities they present. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(1), 158–174.

de Luque, M. S., Washburn, N. T., Waldman, D. A., & House, R. J. (2008). Unrequited profit: How stakeholder and economic values relate to subordinates’ perceptions of leadership and firm performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 53(4), 626–654.

deCharms, R. (1968). Personal causation: The internal affective determinant of behavior. New York: Academic Press.

Deci, E. L. (1976). Notes on the theory and metatheory of intrinsic motivation. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 15(1), 130–145.

Deci, E. L., Connell, J. P., & Ryan, R. M. (1989). Self-determination in a work organization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74(4), 580.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1980). The empirical exploration of intrinsic motivational processes. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 13, 39–80.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 19(2), 109–134.

Deci, E., & Ryan, R. M. (2011). Self-determination theory. Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology, 1, 416–433.

Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Gagné, M., Leone, D. R., Usunov, J., & Kornazheva, B. P. (2001). Need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in the work organizations of a former eastern bloc country: A cross-cultural study of self-determination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(8), 930–942.