Abstract

Our study contributes by providing new insights into the relationship between the individual levels of the antecedents and how the intention of whistleblowing is moderated by perceived organizational support (POS), team norms (TNs), and perceived moral intensity (PMI). In this paper, we argue that the intention of both internal and external whistleblowing depends on the individual-level antecedents [attitudes toward whistleblowing, perceived behavioral control, independence commitment, personal responsibility for reporting, and personal cost of reporting (PCR)] and is moderated by POS, TNs, and PMI. The findings confirm our predictions. Data were collected using an online survey on 256 Indonesian public accountants who worked in the audit firm affiliated with the Big 4 and non-Big 4. The results support the argument that all the antecedents of individual levels can improve the auditors’ intention to blow the whistle (internally and externally). The nature of the relationship is more complex than analysis by adding moderating variables using the Partial Least Squares-Structural Equation Modeling approach. We found that POS, TNs, and PMI can partially improve the relationship between the individual-level antecedents and whistleblowing intentions. These findings indicate that the POS, TNs, and PMI are a mechanism or that attribute is important in controlling behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

More recently, the public was shocked by corporate scandals in which the main actor was a whistleblower.Footnote 1 The last case that put whistleblowing in the headlines of the news media was about telephone tapping and hacking cases involving the National Security Agency (NSA) and Edward Snowden leaked documents that were meant to be secret (Archambeault and Webber 2015). This suggests that the role of whistleblowers in detecting errors is crucial. On one hand, managers/supervisors often learn from mistakes in their company only when someone blows the whistle about the mistake (Near and Miceli 1985, 2016). On the other hand, a whistleblower may face many obstacles, suffer from the negative impact on his personal and professional life (such as increased levels of stress or loss of reputation), and run the risk of retaliation (Izraeli and Jaffe 1998; Liyanarachchi and Adler 2011; Webber and Archambeault 2015). Given the low public visibility and the high technical complexity of many illegal activities in the company, the success of the monitoring and detection of financial fraud depends largely on auditor (Chiu 2002). However, the auditor cannot be separated from ethical issues related to his work and can also observe the behavior violations of the professional code of conduct among fellow coworkers (Alleyne et al. 2016; Bedard et al. 2008).

The interest of academics on this issue was indicated by the development and testing of several models of research associated with the intention to blow the whistle on audit firms (Alleyne et al. 2016; Curtis and Taylor 2009; Robertson et al. 2011; Seifert et al. 2014; Taylor and Curtis 2010, 2013; Wainberg and Perreault 2016). However, the existing models do not show how the role of the organizational support/team norms and moral intensity possessed the auditor to arrive at causal explanation and assessment of responsibility for the perceived mistakes that caused the auditor’s decision to blow the whistle. Organizational support will eliminate the fear of retaliation when the auditor will report wrong-doings, while the team norms and moral intensity assist the auditor when faced with an ethical dilemma. These factors become key elements of the auditor’s decision to blow the whistle. As stated by Alleyne et al. (2013), previous studies have responded and proposed a model of whistleblowing, but fail to capture all of the important factors for the context of external audit. Alleyne et al. (2013) proposed a new model for whistleblowing, but this model has not been validated empirically. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to validate the model developed by Alleyne et al. (2013) for the Indonesian context.

Indonesia offers an interesting phenomenon to study because it is one country in Southeast Asia that has increased corporate governance significantly in 2015, according to data from the Indonesian Institute for Corporate Directorship (IICD). That is evidenced by Indonesia recently adopting International Accounting Standards such as International Standards on Auditing (ISA) and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). Besides, according to data from the Association of Certified Fraud Examiner (ACFE), in 2015, Indonesia was one of five countries in the world experiencing the largest fraud cases after South Africa, India, Nigeria, and China. This indicates that Indonesia provides the right setting for testing models of whistleblowing, while previous studies have also been conducted in Barbados (Alleyne 2016; Alleyne et al. 2016), China (Liu et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2009), South Africa (Maroun and Gowar 2013; Maroun and Solomon 2014), Turkey (Erkmen et al. 2014; Nayir and Herzig 2012), New Zealand (Liyanarachchi and Newdick 2009), Taiwan (Hwang et al. 2008), South Korea (Park and Blenkinsopp 2009), Ireland (Brennan and Kelly 2007), Australia (Cassematis and Wortley 2013; Liyanarachchi and Adler 2011), Germany (Pittroff 2014), and the US (MacGregor and Stuebs 2014; Robinson et al. 2012). However, research in Indonesia still leaves an empirical gap. In addition, we believe that the high cases of fraud discovered by the ACFE in Indonesia are an indication that the auditors or public accountants in Indonesia are still reluctant to become whistleblowers. So it is important to examine what factors are instrumental in improving the intention of whistleblowing public accountants in Indonesia.

Our study contributes to the current literature in several ways. First, this is the first study to test the model of whistleblowing proposed by Alleyne et al. (2013), where there are many factors that have not been tested and included in previous studies in a single comprehensive model. Thus, this study answers the call from Alleyne et al. (2013) to test their model in external audit functions. Although Alleyne et al. (2016) tested this model on a public accountant in Barbados, the models they tested are incomplete.Footnote 2 Second, this study reconciles evidence mixture of whistleblowing intentions for the Indonesian context, whereas previous studies provide inconsistent evidence for the relationship between variables. For example, Alleyne et al. (2016) found that intentions for whistleblowing were internally affected by attitudes and externally influenced by perceived behavioral control (PBC), while Izraeli and Jaffe (1998), Park and Blenkinsopp (2009), Buchan (2005), and Carpenter and Reimers (2005) found no association. Instead, Dalton and Radtke (2013) found no association between the personal cost of reporting (PCR) and the intention of whistleblowing, while Alleyne et al. (2016) found that relationship.

Third, this study extends state-of-the art research on whistleblowing by providing evidence from Indonesia. Based on our best knowledge, this is the first study conducted in Indonesia that tests the intentions of whistleblowing on a public accountant. Because there are no empirical results available from Indonesia on whistleblowing in the context of accounting, this study provides initial evidence of the importance of individual and organizational factors in support of whistleblowing intentions on public accountants (Alleyne et al. 2013; Mesmer-Magnus and Viswesvaran 2005). Finally, it is important to conduct this study with experienced professionals such as CPAs, who experience real-life ethical dilemmas that may be different from those outside the professional organizations (Curtis and Taylor 2009). Previous studies have used students (Gao et al. 2015), internal auditors (Alleyne 2016; Robinson et al. 2012; Seifert et al. 2014), managers (Nayir and Herzig 2012), and employees (Cassematis and Wortley 2013; Liu et al. 2015). However, few studies have used public accountants as a sample.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. The next section presents the development of the hypotheses, followed by the research method employed. Next, we present our results. Finally, we discuss the results and provide important implications of our study as well as its limitations.

Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

Whistleblowing as Pro-social Behavior and the Mechanisms of Justice

The act of whistleblowing can be framed as a pro-social part of the contemporary corporate governance system (Maroun and Atkins 2014), which has synergy with mechanisms for promoting justice in organizations. From this perspective, whistleblowing is seen as a positive behavior (not selfish and altruistic) conducted without a specific purpose (such as reward or praise) and the action is in line with social norms (Brennan and Kelly 2007; Dozier and Miceli 1985; Seifert et al. 2010). Whistleblowing and corporate governance are linked because both of them aim to promote organizational effectiveness, corporate social responsibility, and employee empowerment (Callahan et al. 2002; Vandekerckhove 2006). As described by Callahan et al. (2002), unifying these significant contemporary organizational trends offers an opportunity for organizations to improve their efficiency when relating to stakeholders, increase employee morale, reduce risk-related damages to reputation, and boost ethical behavior throughout the corporate context. According to Vera-Munoz (2005), whistleblower provisions to handle anonymous misconduct is one of the pillars that sustain the corporate governance reforms and framework adopted by the modern U.S.

Whistleblowing act can be characterized as a pro-social empowered behavior driven both by voluntary and duty-related disclosures of wrongdoing. A pro-social behavior is intended to be socially beneficial and motivated, although exceptions can be noticed, such as revenge (Seifert et al. 2010) and other dysfunctions (Maroun and Atkins 2014). In this context, theory of organizational justice has the potential to contribute to the implementation of effective whistleblowing mechanisms because research has indicated a positive relationship between its justice dimensions and pro-social behaviors (Seifert et al. 2010; Soni et al. 2015). When subordinates feel treated fairly, they will tend to have pro-social behavior against the company, thus increasing the possibility to report wrong-doings.

In some countries, including Indonesia, there are policies or regulations governing whistleblowing.Footnote 3 Indeed, in Indonesia the issue of whistleblowing received attention in 1998, precisely during the economic crisis. The system of corporate governance that is weak in Indonesia led to wrong-doings difficult to detect. To that end, the National Committee on Governance as the pioneer of whistleblowing in Indonesia introduced a system which can prevent violations in the company. Every company in Indonesia currently has a whistleblowing system to support good corporate governance. Some rules were made for the protection of whistleblower in Indonesia such as Law No. 13 of 2006. However, the Whistleblower Protection Act (WPA) in Indonesia has not fully protected whistleblowers from various risks and retaliation.

In this paper, we tested the whistleblowing conceptual model developed by Alleyne et al. (2013), in which there are five factors of individuals who become antecedents/predictors for attitudes toward whistleblowing (ATW), PBC, independence commitment (IC), personal responsibility for reporting (PRR), and PCR, with three moderating variables, namely perceived organizational support (POS), team norms (TNs), and perceived moral intensity (PMI) that affect whistleblowing intentions both internally and externally. Furthermore, the development of hypotheses for this research will be described. First, the hypothesis of the direct relationship between the variables is presented, followed by the hypothesis of the interaction between variables. Figure 1 presents a conceptual model that will be tested in this study.

Attitudes Toward Whistleblowing and Whistleblowing Intentions

Ajzen (2005) stated that the attitude is the disposition to respond positively or not, either for an object, a person, an institution, or an event. The theory of planned behavior (TPB) found that attitude is strongly predictive of behavioral intentions (Ajzen 2005). Attitude will have a direct influence on the intentions of whistleblowing to assess how favorably or unfavorably individuals blow the whistle (Alleyne et al. 2013; Izraeli and Jaffe 1998). This is also in line with the expectation theory proposed by Vroom (1964), where potential whistleblowers report (action) offense only if they hope that such measures provide the expected results.Footnote 4 Previous research has found a significant relationship between attitudes and intentions of whistleblowing (Alleyne et al. 2016; Park and Blenkinsopp 2009; Trongmateerut and Sweeney 2013), ethical behavior (Alleyne and Phillips 2011; Bobek and Hatfield 2003; Bobek et al. 2007; Buchan 2005; Carpenter and Reimers 2005; Cieslewicz 2016), and sustainability reporting (Thoradeniya et al. 2015). From the above discussion, the following hypothesis can be derived:

H1

Attitude toward whistleblowing has a positive effect on both internal and external whistleblowing intentions.

Perceived Behavioral Control and Whistleblowing Intentions

PBC is the individual’s perception of how easy or difficult it is to perform certain behaviors depending on the resources and opportunities that exist (Ajzen 2005). For example, a public accountant would have a dilemma when he wanted to blow the whistle on colleagues or superiors as an audit partner who signed the audit report that is free from material misstatement in the financial statements misleading (Alleyne et al. 2013). However, when there are resources and opportunities that support it (such as support from top management or trusted channel), he may report the violation. In other words, the PBC has implications for a strong motivation toward intention, where the greater the individual’s PBC, the greater the possibility or intention to perform the behavior (Ajzen 2005). Previous research has found a significant relationship between the PBC and the intentions of whistleblowing (Alleyne et al. 2016; Park and Blenkinsopp 2009), ethical behavior (Alleyne and Phillips 2011; Bobek et al. 2007; Cieslewicz 2016), and sustainability reporting (Thoradeniya et al. 2015). From the above discussion, the following hypothesis can be derived:

H2

Perceived behavioral control has a positive effect on both internal and external whistleblowing intentions.

Independence Commitment and Whistleblowing Intentions

Gendron et al. (2006) defined IC as “the extent to which the individual accountant considers auditor independence as a key attribute of the profession, and believes that regulatory standards of auditor independence (issued by the profession and/or external regulatory agencies) should be rigorously binding and enforced in the public accounting domain.” In the context of the audit, the IC is considered to be the key for objectivity and integrity, so this is an important factor in favor of whistleblowing intentions. Thus, public accountants must act and be seen as an independent in both tasks and performances. When a public accountant has a high IC and is confronted with ethical issues, he will be inclined to take action to report unethical behavior. Previous research has found a significant relationship between the independence of the commitment and intentions of whistleblowing (Alleyne 2016; Taylor and Curtis 2010), as well as between role conflict and role ambiguity (Ahmad and Taylor 2009). From the above discussion, the following hypothesis can be derived:

H3

Independence commitment has a positive effect on both internal and external whistleblowing intentions.

Personal Responsibility for Reporting and Whistleblowing Intentions

Graham (1986) defined personal responsibility as “the psychological state of feeling personally responsible for responding to an issue of principle….” (p. 39). In the auditing profession, the rights and responsibilities of professional auditors to report errors are set in a professional code of conduct and regulations (for example, ISA), so that PRR is regarded as one important component in deciding to report violations (Dalton and Radtke 2013; Lowe et al. 2015). When the whistleblowing is seen as a pro-social behavior/moral obligation in a company, PRR will influence the decision of individuals to report defiance by the moral sense of whether it is right or wrong (Alleyne et al. 2013; Miceli and Near 1984). So individuals who have a high PRR are more likely to report violations (Schultz et al. 1993). Previous research has found a significant relationship between the PRR and the intention of whistleblowing (Alleyne et al. 2016; Dalton and Radtke 2013; Kaplan and Whitecotton 2001; Lowe et al. 2015; Schultz et al. 1993). From the above discussion, the following hypothesis can be derived:

H4

Personal responsibility for reporting has a positive effect on both internal and external whistleblowing intentions.

Personal Cost of Reporting and Whistleblowing Intentions

Dalton and Radtke (2013) stated that “PCR is the perceived harm or discomfort that could result from reporting wrongdoing.” Various studies have shown that retaliation or threat can hinder the whistleblower’s decision to report violations (Bedard et al. 2008; Liyanarachchi and Adler 2011; Miceli 2013; Rehg et al. 2008). The threat may be a rejection of raises, unfair performance appraisal, reduction of duties, reduction in communication with colleagues/management, or termination from the company. Previous research has found a significant negative relationship between PCR and the intention of whistleblowing (Alleyne et al. 2016; Kaplan and Whitecotton 2001; Schultz et al. 1993). From the above discussion, the following hypothesis can be derived:

H5

Personal cost for reporting has a negative effect on both internal and external whistleblowing intentions.

Moderating Effect of Perceived Organizational Support on Individual-Level Antecedents and Whistleblowing Intentions

According to organizational support theory (OST; (Eisenberger et al. 1986; Rhoades and Eisenberger 2002), employees develop a general perception concerning the extent to which the organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being (perceived organizational support or POS). So the POS is highly dependent on the individual attribution by assessing whether certain actions are favorable or unfavorable and in accordance with the goals and objectives of the organization (Kurtessis et al. 2015). Similarly, within audit firms, public accountants will feel comfortable in the decision to blow the whistle when there is high support from the organization (Alleyne et al. 2013). However, POS by itself may not stimulate the intention to report errors (Alleyne et al. 2016), but it could when combined with the characteristics of the individual levels of the auditor.

A public accountant may have ATW, PBC, IC, and PRR to report errors/unethical behaviors that occur in the workplace, but he also needs to consider the POS available before deciding to report it. So the POS can reinforce the intention of whistleblowing, where the auditor may be more confident and have the courage to report any violations without fear/worry. In addition, the auditor should also assess the level of support expected when deciding whether to report any errors, thus reducing PCR. In other words, the POS will provide assurance that the auditors are free from the risk of retaliation. Previous research has found a significant relationship between the ATW, PBC, IC, PRR, and PCR with the intention of whistleblowing moderated by POS (Alleyne et al. 2016). From the above discussion, the following hypotheses can be derived:

H6a

Perceived organizational support will moderate the relationship of ATW with both internal and external whistleblowing intentions.

H6b

Perceived organizational support will moderate the relationships of PBC with both internal and external whistleblowing intentions.

H6c

Perceived organizational support will moderate the relationships of IC with both internal and external whistleblowing intentions.

H6d

Perceived organizational support will moderate the relationships of PRR with both internal and external whistleblowing intentions.

H6e

Perceived organizational support will moderate the relationships of PCR with both internal and external whistleblowing intentions.

Moderating Effect of Team Norms on Individual-Level Antecedents and Whistleblowing Intentions

Feldman (1984) stated that TNs are the informal rules that groups adopt to regulate and regularize group members’ behavior. Previous research has explained the close relationship between the TNs and unethical behavior (Dunn and Schweitzer 2006; Narayanan et al. 2006; Zhong et al. 2006). The extent to which an individual is involved in a particular behavior is largely dependent on the norms inherent in the group where he became a member (Alleyne et al. 2013). The concept of norms in the context of unethical behavior has received much attention from researchers, where the perceived social pressure and subjective norms are two important factors that influence ethical decision making (Ajzen 2005; Buchan 2005). Therefore, we argue that the norms in the audit team may also affect the behavior of individual members, where an auditor will report any errors that occur in both the assignment and the engagement when the TNs are in line with professional standards and codes of conduct. So the TNs will strengthen the relationship between the ATW, PBC, IC, PRR, and PCR with the intention of whistleblowing (Alleyne et al. 2013; Narayanan et al. 2006). From the above discussion, the following hypotheses can be derived:

H7a

Team norms will moderate the relationship of ATW with both internal and external whistleblowing intentions.

H7b

Team norms will moderate the relationship of PBC with both internal and external whistleblowing intentions.

H7c

Team norms will moderate the relationship of IC with both internal and external whistleblowing intentions.

H7d

Team norms will moderate the relationship of PRR with both internal and external whistleblowing intentions.

H7e

Team norms will moderate the relationship of PCR with both internal and external whistleblowing intentions.

Moderating Effect of Perceived Moral Intensity on Individual-Level Antecedents and Whistleblowing Intentions

Jones (1991) stated that the individual ethical decision-making model should place emphasis on the characteristics of ethical issues. Based on the issue-contingency perspective, Jones (1991) introduced a construct called moral intensity with which the determining factors are ethical decision making and behavior. We adopt this perspective that assumes individuals more easily identify ethical issues when they have high moral intensity. Moral intensity is composed of six factors: (1) magnitude of consequences, (2) social consensus, (3) probability of effect, (4) temporal immediacy, (5) proximity, and (6) concentration of effect. However, according to Curtis and Taylor (2009), only three factors are relevant in the context of the audit, which include the magnitude of consequences, probability of effect, and proximity, and these three factors can affect the auditor’s whistleblowing intentions (p. 198).

The first factor, magnitude of consequences, refers to the sum of harm (or benefits) done to victims (or beneficiaries) in terms of the moral act in question (Jones 1991, p. 374). The magnitude of consequences includes the auditor blowing the whistle when a violation of auditing standards and professional codes of conduct only results in significant losses. The second factor, the probability of effect of the moral act in question, is a joint function of the probability that the act in question will actually take place and cause the harm (benefit) predicted (Jones 1991, p. 375). When a whistleblower is faced with the decision to blow the whistle, error usually occurs. However, the possibility that a mistake will cause harm in the future is a matter that must be considered. Finally, the proximity of the moral issue is the feeling of nearness (social, cultural, psychological, or physical) that the moral agent has for victims (beneficiaries) of the evil (beneficial) act in question (Jones 1991, p. 376). Generally, people tend to report a violation that is potentially detrimental to their group members (such as coworkers or family members), but they are less likely to report it when they personally do not know each other. Previous research has found a significant relationship between moral intensity and the intention to behave ethically (Singer 1996; Coram et al. 2008; McMahon and Harvey 2007; Valentine and Hollingworth 2012) and the intention of whistleblowing (Clements and Shawver 2011; Curtis and Taylor 2009; Taylor and Curtis 2010; Shawver and Clements 2015; Shawver et al. 2015). Another study from Beu et al. (2003) showed that the moral intensity moderates the relationship between several independent variables and the intention to behave ethically. From the above discussion, the following hypotheses can be derived:

H8a

Moral intensity will moderate the relationship of ATW with both internal and external whistleblowing intentions.

H8b

Moral intensity will moderate the relationship of PBC with both internal and external whistleblowing intentions.

H8c

Moral intensity will moderate the relationship of IC with both internal and external whistleblowing intentions.

H8d

Moral intensity will moderate the relationship of PRR with both internal and external whistleblowing intentions.

H8e

Moral intensity will moderate the relationship of PCR with both internal and external whistleblowing intentions.

Research Method

Sample Selection and Data Collection

The respondents in this study were public accountants who worked on the audit firm in Indonesia that is affiliated with both the Big 4 and non-Big 4 (non-affiliated).Footnote 5 We collected data using online questionnaires by placing the item in question to measure each construct in this study on a virtual network. Web links to the questionnaire later in an email to the audit firm (headquarters) are scattered in various cities in Indonesia. Email addresses from the audit firms were obtained from the directory of the Indonesian Institute of Certified Public Accountants (IAPI) for 2015. Based on that directory, 400 audit firms contacted a total of 1000 staff auditors.Footnote 6 After sending the original invitation to complete the survey, the research team sent two additional reminder emails. Finally, to improve the response rate, the research team started a more personal approach by calling the targeted respondent. In addition, respondents were reassured about the confidentiality and anonymity of their responses and that their personal information would not be disclosed. Furthermore, for the purpose of testing non-response bias, as suggested by Oppenheim (2001), the length of time given to respondents to complete this survey was 2 months.

At the end of this process, which took place between September and December 2015, we obtained 278 questionnaire responses, of which 22 were incomplete questionnaires, so the number of questionnaires that were valid and could be used in this study was 256 with a 25.6 % response rate. Of the 256 completed questionnaires, 35.3 % came from audit firms affiliated with the Big 4 and the remaining 64.7 % came from audit firms that are not affiliated (non-Big 4). Results of the t test showed that there was no difference in the statistically significant response (p < 0.05) between public accountants who came from the Big 4 and non-Big 4. We also used the Wilcoxon test for comparison. In addition, the statistical test results also showed that there was no significant difference between the response in the initial 10 respondents compared to the 10 late respondents,Footnote 7 which means that there is no problem of non-response bias that would affect the systematic results (Dillman et al. 2014). We also conducted testing for common method bias (Podsakoff et al. 2003; MacKenzie and Podsakoff 2012) using a full collinearity approach (Kock 2015). The analysis showed that the value obtained for AFVIF was less than 3.3, thus indicating that no common method bias problem occurred.

We believe that the number of questionnaires obtained is enough, based on comparisons with similar studies, for example, studies of Cieslewicz (2016) with 93 respondents, Curtis and Taylor (2009) with 122 respondents, and Robertson et al. (2011) with 129 respondents. In addition, some rules were applied to prove the adequacy of the sample size so that it did not affect the results of this study. Using Cohen’s (1992) rules, the minimum sample required is 114 (power = 80 %, significance level of 1 %, R 2 < 0.25, and minimum number of arrows pointing at a construct ≤ 8). In addition, by using the software G* power, the minimum sample required for this study was 148 (power = 0.80, effect size = 0.15, significance level of 1 %, and number of predictors ≤ 8). So, by setting all the existing rules, the study had a sample size that is larger than the minimum size recommended.Footnote 8

The summary of the respondent’s demographic profile can be described as follows. Of the 256 respondents, 61.6 % were male, with an average age of 35.4 years. In terms of positions, 37.4 % of the sample comprised senior audit staff and 62.6 % comprised junior audit staff. As for qualifications, 61.2 % held a college degree, 70.8 % of the sample had professional qualifications, and 40.2 % of the sample had completed the CPA professional qualification.

Measurement of Variables

The instrument used to measure each variable in this study consists of two parts.Footnote 9 The first part asked for the respondents’ demographic information such as gender, age, education level, work experience, and job title. The second part presented the scenarios and questions related to the variables to be studied. Given the difficulty in gaining access to the object in order to observe the real unethical behavior, a scenario approach is commonly used in research in the field of accounting and ethics (for example, Curtis and Taylor 2009; Dalton and Radtke 2013; Liyanarachchi and Adler 2011; Robertson et al. 2011; Shawver et al. 2015). This approach illustrates a specific case, and the respondents were asked to respond and put themselves as an actor in such situations. The scenario used in this study was adopted from the scenario used by Clements and Shawver (2011), Curtis and Taylor (2009), Kaplan and Whitecotton (2001), and Schultz et al. (1993) highlighting violations of auditing standards and the auditors’ professional code of conduct.Footnote 10

Whistleblowing Intentions

For the constructs of the whistleblowing intentions, both internally and externally, each item was measured using four questions and was adopted from Park and Blenkinsopp (2009). Respondents were asked whether they would report an error or violation that occurs within the company, either internally or externally, by selecting one of the seven (7) options using Likert scale from 1 = not at all to 7 = very much. The values obtained validity and reliability of the analytical result measurement model for both the loading factors so that rho_A is >0.70 and the value of AVE is > 0.50, thus meeting the recommended requirements (Hair et al. 2017). Park and Blenkinsopp (2009) and Alleyne et al. (2016) also obtained similar results when using this instrument. Table 1 below shows the indicators and outcome measurement model for this variable.

Attitudes Toward Whistleblowing

The ATW constructs were measured using a five-item questionnaire adopted from Park and Blenkinsopp (2009). Respondents were asked about the critical consequences of reporting errors or violations occurring in the audit firm in the scenario by selecting one of the seven (7) options using a Likert scale from 1 = not very true to 7 = very true. The obtained values for validity and reliability are rho_A is >0.70 and the value of AVE is > 0.50, thus meeting the recommended requirements (Hair et al. 2017; Latan and Ghozali 2015). Park and Blenkinsopp (2009) and Alleyne et al. (2016) also obtained similar results when using this instrument. Table 2A below shows the indicators and outcome measurement model for this variable.

Perceived Behavioral Control

PBC constructs are measured using a four-item questionnaire adopted from Park and Blenkinsopp (2009). Respondents will be asked about how easy or difficult it is to report errors or violations occurring in the audit firm by selecting one of the seven (7) options using a Likert scale from 1 = not likely to 7 = very likely. The values obtained validity and reliability of the analytical result measurement model for both the loading factors so that rho_A is >0.70 and the value of AVE is > 0.50 (Hair et al. 2017; Latan and Ghozali 2015). Park and Blenkinsopp (2009) and Alleyne et al. (2016) also obtained similar results when using this instrument. Table 2B above shows the indicators and outcome measurement model for this variable.

Independence Commitment

IC constructs were measured using a four-item questionnaire adopted from Gendron et al. (2006). Respondents were asked to reflect on their current organization and in the context of the scenario and assess the level of IC by selecting one of the seven (7) options using a Likert scale from 1 = completely disagree to 7 = completely agree. The values obtained validity and reliability of the analytical result measurement model for both the loading factors so that rho_A is >0.70 and the value of AVE is > 0.50, thus meeting the recommended requirements (Hair et al. 2017; Latan and Ghozali 2015). Gendron et al. (2006) and Alleyne et al. (2016) also obtained similar results when using this instrument. Table 3A below shows the indicators and outcome measurement model for this variable.

Personal Responsibility for Reporting and Personal Cost of Reporting

PRR and PCR constructs were measured, respectively, using the single item in question adopted from Schultz et al. (1993). Respondents were asked to rate their personal responsibilities (duties or obligations) in reporting violations, while the second question asked respondents to rate their personal costs (i.e., issues, risks, and discomfort) as a public accountant in reporting errors that occur. Each item in question was measured using a Likert scale of 7 points, namely from 1 = very low to 7 = very high. The validity and reliability for these two variables do not need to be tested (Hair et al. 2017; Latan and Ghozali 2015). Table 3B and C shows the indicator for this variable.

Perceived Organizational Support, Team Norms, and Perceived Moral Intensity

POS constructs were measured using an eight-item questionnaire adopted from Eisenberger et al. (1986) and Rhoades and Eisenberger (2002). Respondents were asked to think about their organization and to provide their perceptions on how organizational support in the workplace, by selecting one of the seven (7) options using a Likert scale from 1 = completely disagree to 7 = completely agree. As for the PMI constructs measured, they were using a six-item questionnaire adopted from Clements and Shawver (2011). Respondents were asked to provide feedback on the scenarios to assess the level of moral intensity with 1 = strongly agree to 7 = strongly disagree. The obtained values for validity and reliability are rho_A is >0.70 and the value of AVE is > 0.50 (Hair et al. 2017; Latan and Ghozali 2015). Table 4 shows the indicators and outcome measurement model for this variable.

Finally, we tested the discriminant validity for all variables in the model. Table 5 above shows the results of testing discriminant validity (divergent) using Fornell–Larcker criterion and heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT). From the analysis above, it can be seen that the square root of the AVE on diagonal lines is greater than the correlation between the constructs in the model, which means that it can be concluded that all variables in this research model meet the discriminant validity. We also tested the discriminant validity using HTMT, and the results of the analysis in the table above show that the value of HTMT was smaller than 0.90, which means that it meets the recommended requirements (Hair et al. 2017; Henseler et al. 2015; Latan and Ghozali 2015).

Data Analysis

Once we are sure that the adequacy of the sample size and a preliminary analysis has been fulfilled, we analyzed the data using a Partial Least Squares-Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) approach. The main purpose of the PLS-SEM is to analyze the complex situations where data and prior information are relatively scarce (Rigdon 2016; Wold 1977, 1982).Footnote 11 Previous research in this area also used PLS-SEM as an analytical tool (Buchan 2005; Cieslewicz 2016; Dalton and Radtke 2013; Thoradeniya et al. 2015). Because PLS-SEM is the distribution-free (soft modeling), then some assumptions such as normality is not necessary, but still maintain the assumption of such quality of measurement model and structural model will be described in the following sections.Footnote 12

Results

We tested the hypothesis using a PLS-SEM approach. PLS-SEM election is made on the grounds that this approach can test causal–predictive relationships between the latent variables simultaneously to support the weak theory (Jöreskog and Wold 1982). PLS-SEM enables researchers to examine the relationship with the complex variables, which is not possible using the covariance-based SEM approach or traditional regression (Hair et al. 2017; Latan and Ghozali 2015).Footnote 13 Testing PLS will pass through two stages, namely the measurement model and the structural model. The measurement model is intended to assess the validity (convergent and discriminant) and reliability of each indicator forming latent constructs (Latan and Ghozali 2015). Evaluation of the measurement model is already done in the previous section.Footnote 14 Furthermore, the evaluation of the structural model, it is intended to assess the quality of the model and examine the research hypothesis with the help of the SmartPLS 3 program (Ringle et al. 2015) through the process of bootstrapping (bias-corrected and accelerated), with a 5000 resample that obtained structural model evaluation results in Table 6.

In Table 6, it can be seen that the internal/external whistleblowing (IWB/EWB) is able to be explained by individual-level antecedents (e.g., ATW, PBC, IC, PRR, PCR) of 0640/0612 or 64/61.2 %. This value indicates that the ability of the predictor variables to explain the outcome variables was approaching substantial (Latan and Ghozali 2015). The resulting effect size value of each predictor variable in the model ranged from 0.01 to 0.09, which is included in the category of small to medium. The value of variance inflation factor (VIF) generated for all the independent variables in the model is <3.3, which means that there was no collinearity problem between the predictor variables. The Q 2 predictive relevance value generated excellent endogenous variables, i.e., >0, which means that the model has predictive relevance. The value of goodness of fit that is generated through the standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) that is equal to 0.062 < 0.080 and the normed fix index (NFI) 0.802 > 0.80, which means that our model fits the empirical data.

Hypothesis Testing (Direct Effect)

We tested the hypothesis (direct effect) before testing the hypothesis (interaction) with a view of the coefficient parameter and the significant value generated from the 95 % bias-corrected confidence intervals of each independent variable. As shown in Table 7 below, the ATW and PBC positively and significantly affected either internal whistleblowing ATW → IWB β = 0.283, p = 0.003; PCB → IWB β = 0.396, p = 0.001 or external whistleblowing ATW → EWB β = 0.283, p = 0.003; PCB → EWB β = 0.290, p = 0.002 (one-tailed), thus fully supporting H1 and H2. These results are consistent with the TPB stating that the ATW and PBC are important predictors in influencing behavior. Public accountants who have high ATW and PBC will tend to have a high whistleblowing intention in reporting errors that occur. Furthermore, variables IC, PCR, and PCR were also positive and significant for both internal whistleblowing IC → IWB β = 0.260, p = 0.003; PRR → IWB β = 0.268, p = 0.001; PCR → IWB β = −0.029, p = 0.001 and external whistleblowing IC → EWB β = 0.236, p = 0.008; PRR → EWB β = 0.384, p = 0.002; PCR → EWB β = −0.073, p = 0.001 (one-tailed),Footnote 15 thus fully supporting H3–H5. Public accountants who have high IC and PRR tend to act in accordance with professional standards and a code of ethics, so they will have strong whistleblowing intentions for any violations. Conversely, if the PCR is perceived high/low by the auditor, the whistleblowing intentions will depend on the cost/benefit perceived. So, the lower the risk, the higher the auditors’ whistleblowing intentions in error reporting.

The results support previous studies (Alleyne et al. 2016; Park and Blenkinsopp 2009; Dalton and Radtke 2013; Kaplan and Whitecotton 2001; Lowe et al. 2015; Schultz et al. 1993; Taylor and Curtis 2010; Trongmateerut and Sweeney 2013) and extend the generalization of the findings in different contexts. Given the currently corporate governance has increased significantly in Indonesia, supported by the adoption of International Accounting Standards such as ISA and IFRS recently, perhaps a direct implication on improving the intention of auditor in reporting wrong-doings. In addition, with the support of the WPA and the availability of a trusted channel in Indonesia, the auditor in Indonesia starting today is not reluctant to blow the whistle. Both these factors play an important role in influencing the decision of the auditor’s to report wrong-doings in the context of Indonesia.

Hypothesis Testing (Interaction Effect)

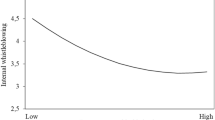

We tested the hypothesis interactions using the orthogonalization approach.Footnote 16 This approach was chosen because it produces an accurate estimate, has a high predictive accuracy, and is able to minimize collinearity problem. The results of the analysis of interactions are shown in Table 8. From the table, it can be seen that the hypotheses 6–8 are supported partially, whereas POS, TNs, and PMI may moderate the relationship between the individual-level antecedents and the intentions of whistleblowing.

This shows that the organizational support and norms applied in the organization play an important role in improving the auditors’ ethical attitudes, and the consequence is that they have the higher intention of whistleblowing to report any errors or violations. Also, the moral intensity possessed by the auditor will assist in considering any magnitude of the consequences, the probability of future losses, and the close relationship with the organization or individual in decisions or actions to blow the whistle. Organizational support will assist the auditor in the face of perceived stress and norms shaping the character of a public accountant. Finally, with the moral intensity owned, the public accountant can act with high prudence.

The results support previous studies (Alleyne et al. 2013, 2016; Clements and Shawver 2011; Curtis and Taylor 2009; Narayanan et al. 2006; Taylor and Curtis 2010; Shawver and Clements 2015). Given that the social norms and moral behavior are still strong in Indonesia, with the freedom to act, it becomes a supporting factor for auditors in improving the intention to report wrong-doings without fear.

Conclusion

Our study contributes by providing new insights into the relationship between the individual levels of the antecedents to the intention of whistleblowing moderated by POS, TNs, and PMI. We answered the call of Alleyne et al. (2013) to test their model in the context of an external audit. In this paper, we argue that the intention of whistleblowing (both internal and external), depending on the individual-level antecedents (i.e., ATW, PBC, IC, PRR, and PCR), was directly and partially moderated by POS, TNs, and PMI. These findings confirm our predictions.

We support the argument that the individual-level antecedents can increase the public accountant’s intentions of whistleblowing. We have found models of whistleblowing where there is a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between individual-level antecedents to the intention of whistleblowing reinforced by moderating variables (e.g., POS, TNs, and PMI). In the practical implications, these findings provide a deep understanding of how the audit firm must be selective in choosing the audit staff that upholds professional and ethical standards of behavior and that is expected to report any errors that occur. In addition, there is a need for a training program that provides guidance to staff auditors to resolve the ethical conflict and improve the professional attitude, IC, and PRR. Audit firms also need to implement appropriate strategies to improve the auditors’ whistleblowing intentions and reduce the fear of reprisal (e.g., by holding a whistleblower hotline or reporting anonymity). Finally, senior management within the audit firm needs to implement positive norms, in accordance with professional ethics, so that the audit staff can have responsibility for the company in reporting errors.

There are several limitations to this study that should be noted. First, some of the variables in this study were measured using a single item. This may reduce the content validity of the construct being measured. Secondly, interaction testing was only partially carried out, without examining the simultaneous effects of the three moderating variables.Footnote 17 The different results may be obtained when considering it. Third, this study did not consider the effect of extraneous variables that might interfere with the results of this study (such as age, gender, or total tenure). Finally, this study only tested the whistleblowing intentions without testing the actual behavior.

Subsequent research could look into the relationship between the individual-level antecedents and the intentions of whistleblowing mediated by several variables such as trust in the supervisor/organization (Seifert et al. 2014), perceived benefit/seriousness (Dalton and Radtke 2013), or organizational culture (Kaptein 2011). Furthermore, a comparative study to examine the influence of extraneous variables is also needed (Erkmen et al. 2014). Replication studies on the other subjects and organizations will also allow access to generalize the findings of this study. Overall, the researchers feel that it is necessary to replicate this study using a qualitative approach/fsQCA (Henik 2015), which might provide new avenues for future studies in this research area.

Notes

Whistleblowing is “the disclosure by organization members (former or current) of illegal, immoral, or illegitimate practices under the control of their employers, to persons or organizations that may be able to affect action” (Near and Miceli 1985, p. 4).

Alleyne et al. (2016) examined the influence of individual-level antecedents to the intention of whistleblowing using only POS as a moderating variable. But they ignore the other moderating variables such as TNs and PMI.

See Vandekerckhove (2006) for a description of the whistleblowing system in some other countries such as the US, Australia, New Zealand, the U.K., South Africa, Japan, Belgium, and Germany.

The expectation theory by Vroom (1964) assumes that every individual believes that when he behaves in a certain way, he will obtain certain result called an expectation result (outcome expectancy). Each result has a value or an appeal to a particular person.

Audit firms (Big 4) are affiliated in Indonesia, including, among others, PriceWaterhouseCoopers with KAP Tanudiredja, Wibisana, Rintis & Rekan; Deloitte with KAP Osman Bing Satrio; Ernst and Young with KAP Purwantono, Sungkoro & Surja; and KPMG with KAP Sidharta and Widjaja.

The number of registered auditors certified as CPA in IAPI until June 2016 was 1628, while the number of registered audit firms was 525 (plus branches).

We compared 10 samples beginning with 10 samples at the end to obtain more precise results. Most of the studies generally compare the overall sample before and after the cut-off. Differences in the distance are too close and may lead to biased analysis.

Although this study uses a component-based approach (PLS-SEM), the adequacy of the sample size remains a concern for researchers.

The original copy of the questionnaire is available from the author.

The use of scenarios is more effective to give stimuli to the auditor in making ethical decisions when faced with certain situations.

When researchers do not know the data from the population common factor or composites, the use of PLS-SEM is a safer option (see Sarstedt et al. 2016).

See Henseler et al. (2017) to update the guidelines for the evaluation criteria of measurement and structural models in PLS-SEM.

The CB-SEM approach will have problems when estimating models that are very complex. In contrast, the traditional regression approach has many limitations such that it cannot test the model simultaneously and based on the total score of the variable.

Evaluation of the measurement model includes the assessment of the loading factor, average variance extracted (AVE), rho_A, and HTMT assessment as a discriminant validity assessment, which is more superior to the Fornell–Larcker criterion.

We tested the hypothesis using the one-tailed test rather than the two-tailed. Testing the hypothesis using one-tailed test is more appropriate when the hypothesis direction is clear so as to minimize the type II error.

Besides the orthogonalization approach, there are also a product indicator and a two-stage approach to test the interaction effects.

It aims to reduce the complexity of the model and multicollinearity problems that may arise. This is also in line with the proposition put forward by Alleyne et al. (2013).

References

Ahmad, Z., & Taylor, D. (2009). Commitment to independence by internal auditors: The effects of role ambiguity and role conflict. Managerial Auditing Journal, 24(9), 899–925.

Ajzen, I. (2005). Attitudes, personality and behaviour (2nd ed.). Berkshire: Open University Press.

Alleyne, P. (2016). The influence of organisational commitment and corporate ethical values on non-public accountants’ whistle-blowing intentions in Barbados. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 17(2), 190–210.

Alleyne, P., Hudaib, M., & Haniffa, R. (2016). The moderating role of perceived organisational support in breaking the silence of public accountants. Journal of Business Ethics. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2946-0.

Alleyne, P., Hudaib, M., & Pike, R. (2013). Towards a conceptual model of whistle-blowing intentions among external auditors. The British Accounting Review, 45(1), 10–23.

Alleyne, P., & Phillips, K. (2011). Exploring academic dishonesty among university students in Barbados: An extension to the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Academic Ethics, 9(1), 323–338.

Archambeault, D. S., & Webber, S. (2015). Whistleblowing 101. The CPA Journal, 85(7), 62–68.

Bedard, J. C., Deis, D. R., Curtis, M. B., & Jenkins, J. G. (2008). Risk monitoring and control in audit firms: A research synthesis. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 27(1), 187–218.

Beu, D. S., Buckley, M. R., & Harvey, M. G. (2003). Ethical decision-making: A multidimensional construct. Business Ethics: A European Review, 12(1), 88–107.

Bobek, D. D., & Hatfield, R. C. (2003). An investigation of the theory of planned behaviour and the role of moral obligation in tax compliance. Behavioural Research in Accounting, 15(1), 13–38.

Bobek, D. D., Hatfield, R. C., & Wentzel, K. (2007). An investigation of why taxpayers prefer refunds: A theory of planned behavior approach. Journal of the American Taxation Association, 29(1), 93–111.

Brennan, N., & Kelly, J. (2007). A study of whistleblowing among trainee auditors. The British Accounting Review, 39(1), 61–87.

Buchan, H. F. (2005). Ethical decision making in the public accounting profession: An extension of Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 61(2), 165–181.

Callahan, E. S., Dworkin, T. M., Fort, T. L., & Schipani, C. A. (2002). Integrating trends in whistleblowing and corporate governance: Promoting organizational effectiveness, societal responsibility, and employee empowerment. American Business Law Journal, 40, 177–215.

Carpenter, T. D., & Reimers, J. L. (2005). Unethical and fraudulent financial reporting: Applying the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 60(2), 115–129.

Cassematis, P. G., & Wortley, R. (2013). Prediction of whistleblowing or non-reporting observation: The role of personal and situational factors. Journal of Business Ethics, 117(3), 615–634.

Chiu, R. K. (2002). Ethical judgement, locus of control, and whistleblowing intention: A case study of mainland Chinese MBA students. Managerial Auditing Journal, 17(9), 581–587.

Cieslewicz, J. K. (2016). Collusive accounting supervision and economic culture. Journal of International Accounting Research, 15(1), 89–108.

Clements, L. H., & Shawver, T. (2011). Moral intensity and intentions of accounting professionals to whistleblow internally. Journal of Forensic Studies in Accounting and Business, 3(1), 67–82.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159.

Coram, P., Glavovic, A., Ng, J., & Woodliff, D. R. (2008). The moral intensity of reduced audit quality acts. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 27(1), 127–149.

Curtis, M. B., & Taylor, E. Z. (2009). Whistleblowing in public accounting: Influence of identity disclosure, situational context, and personal characteristics. Accounting & the Public Interest, 9(1), 191–220.

Dalton, D., & Radtke, R. R. (2013). The joint effects of Machiavellianism and ethical environment on whistle-blowing. Journal of Business Ethics, 117(1), 153–172.

Dillman, D. A., Smyth, J. D., & Christian, L. M. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed mode surveys: The tailored design method (4th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Dozier, J. B., & Miceli, M. P. (1985). Potential predictors of whistle-blowing: A prosocial behavior perspective. Academy of Management Review, 10(4), 823–836.

Dunn, J. R., & Schweitzer, M. E. (2006). Green and mean: Envy and social undermining in organizations. In A. E. Tenbrunsel (Ed.), Ethics in groups: Research on managing groups and teams (Vol. 8, pp. 177–197). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Eisenberger, R., Hungtington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 500–507.

Erkmen, T., Caliskan, A. O., & Esen, E. (2014). An empirical research about whistleblowing behavior in accounting context. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 10(2), 229–243.

Feldman, D. C. (1984). The development and enforcement of group norms. Academy of Management Review, 9(1), 47–53.

Gao, J., Greenberg, R., & Wong-On-Wing, B. (2015). Whistleblowing intentions of lower-level employees: The effect of reporting channel, bystanders, and wrongdoer power status. Journal of Business Ethics, 126(1), 85–99.

Gendron, Y., Suddaby, R., & Lam, H. (2006). An examination of the ethical commitment of professional accountants to auditor independence. Journal of Business Ethics, 64(2), 169–193.

Graham, J. W. (1986). Principled organizational dissent: A theoretical essay. Research in Organizational Behavior, 8, 1–52.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Henik, E. (2015). Understanding whistle-blowing: A set-theoretic approach. Journal of Business Research, 68(2), 442–450.

Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2017). Partial least squares path modeling: Updated guidelines. In H. Latan & R. Noonan (Eds.), Recent developments in PLS-SEM. New York: Springer.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135.

Hwang, D., Staley, B., Chen, Y. T., & Lan, J.-S. (2008). Confucian culture and whistle-blowing by professional accountants: An exploratory study. Managerial Auditing Journal, 23(5), 504–526.

Izraeli, D., & Jaffe, E. D. (1998). Predicting whistle blowing: A theory of reasoned action approach. International Journal of Value Based Management, 11(1), 19–34.

Jones, T. M. (1991). Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. Academy of Management Review, 16(2), 366–395.

Jöreskog, K. G., & Wold, H. (1982). The ML and PLS techniques for modeling with latent variables: Historical and comparative aspects. In K. G. Jöreskog & H. Wold (Eds.), Systems under indirect observation: Causality, structure, prediction (Vol. 1, pp. 263–270). Amsterdam: North Holland.

Kaplan, S. E., & Whitecotton, S. M. (2001). An examination of auditors’ reporting intentions when another auditor is offered client employment. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 20(1), 45–63.

Kaptein, M. (2011). From inaction to external whistleblowing: The influence of the ethical culture of organizations on employee responses to observed wrongdoing. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(3), 513–530.

Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10.

Kurtessis, J. N., Eisenberger, R., Ford, M. T., Buffardi, L. C., Stewart, K. A., & Adis, C. S. (2015, in press). Perceived organizational support: A meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. Journal of Management. doi:10.1177/0149206315575554.

Latan, H., & Ghozali, I. (2015). Partial least squares: Concepts, techniques and application using program SmartPLS 3.0 (2nd ed.). Semarang: Diponegoro University Press.

Liu, S.-M., Liao, J.-Q., & Wei, H. (2015). Authentic leadership and whistleblowing: Mediating roles of psychological safety and personal identification. Journal of Business Ethics, 131(1), 107–119.

Liyanarachchi, G. A., & Adler, R. (2011). Accountants’ whistle-blowing intentions: The impact of retaliation, age, and gender. Australian Accounting Review, 21(2), 167–182.

Liyanarachchi, G. A., & Newdick, C. (2009). The impact of moral reasoning and retaliation on whistle-blowing: New Zealand evidence. Journal of Business Ethics, 89(1), 37–57.

Lowe, D. J., Pope, K. R., & Samuels, J. A. (2015). An examination of financial sub-certification and timing of fraud discovery on employee whistleblowing reporting intentions. Journal of Business Ethics, 131(4), 757–772.

MacGregor, J., & Stuebs, M. (2014). The silent samaritan syndrome: Why the whistle remains unblown. Journal of Business Ethics, 120(2), 149–164.

MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, P. M. (2012). Common method bias in marketing: Causes, mechanisms, and procedural remedies. Journal of Retailing, 88(4), 542–555.

Maroun, W., & Atkins, J. (2014). Section 45 of the auditing profession act: Blowing the whistle for audit quality? The British Accounting Review, 46(3), 248–263.

Maroun, W., & Gowar, C. (2013). South African auditors blowing the whistle without protection: A challenge for trust and legitimacy. International Journal of Auditing, 17(2), 177–189.

Maroun, W., & Solomon, J. (2014). Whistle-blowing by external auditors: Seeking legitimacy for the South African Audit Profession? Accounting Forum, 38(2), 109–121.

McMahon, J. M., & Harvey, R. J. (2007). The effect of moral intensity on ethical judgment. Journal of Business Ethics, 72(4), 335–357.

Mesmer-Magnus, J. R., & Viswesvaran, C. (2005). Whistleblowing in organizations: An examination of correlates of whistleblowing intentions, actions, and retaliation. Journal of Business Ethics, 62(3), 277–297.

Miceli, M. P. (2013). An international comparison of the incidence of public sector whistle-blowing and the prediction of retaliation: Australia, Norway, and the US. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 72(4), 433–446.

Miceli, M. P., & Near, J. P. (1984). The relationships among beliefs, organizational position, and whistle-blowing status: A discriminant analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 27(4), 687–705.

Narayanan, J., Ronson, S., & Pillutla, M. M. (2006). Groups as enablers of unethical behaviour: The role of cohesion on group members actions. In A. E. Tenbrunsel (Ed.), Ethics in groups: Research on managing groups and teams (Vol. 8, pp. 127–147). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Nayir, D. Z., & Herzig, C. (2012). Value orientations as determinants of preference for external and anonymous whistleblowing. Journal of Business Ethics, 107(2), 197–213.

Near, J. P., & Miceli, M. P. (1985). Organizational dissidence: The case of whistle-blowing. Journal of Business Ethics, 4(1), 1–16.

Near, J. P., & Miceli, M. P. (2016). After the wrongdoing: What managers should know about whistleblowing. Business Horizons, 59, 105–114.

Oppenheim, A. (2001). Questionnaire design, interviewing and attitude measurement (2nd ed.). New York: Basic Books.

Park, H., & Blenkinsopp, J. (2009). Whistleblowing as planned behavior—A survey of South Korean police officers. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(4), 545–556.

Pittroff, E. (2014). Whistle-blowing systems and legitimacy theory: A study of the motivation to implement whistle-blowing systems in German organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 124(3), 399–412.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, N. P., & Lee, J.-Y. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Rehg, M. T., Miceli, M. P., Near, J. P., & Scotter, J. R. V. (2008). Antecedents and outcomes of retaliation against whistleblowers: Gender differences and power relationships. Organization Science, 19(2), 221–240.

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 698–714.

Rigdon, E. E. (2016). Choosing PLS path modeling as analytical method in European management research: A realist perspective. European Management Journal. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2016.05.006.

Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J.-M. (2015). SmartPLS 3. Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH. http://www.smartpls.com.

Robertson, J. C., Stefaniak, C. M., & Curtis, M. B. (2011). Does wrongdoer reputation matter? Impact of auditor wrongdoer performance and likeability reputations on fellow auditors’ intention to take action and choice of reporting outlet. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 23(2), 207–234.

Robinson, S. N., Robertson, J. C., & Curtis, M. B. (2012). The effects of contextual and wrongdoing attributes on organizational employees’ whistleblowing intentions following fraud. Journal of Business Ethics, 106(2), 213–227.

Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., Thiele, K. O., & Gudergan, S. P. (2016). Estimation issues with PLS and CBSEM: Where the bias lies! Journal of Business Research, 69(10), 3998–4010.

Schultz, J. J., Johnson, D. A., Morris, D., & Dyrnes, S. (1993). An investigation of the reporting of questionable acts in an international setting. Journal of Accounting Research, 31(3), 75–103.

Seifert, D. L., Stammerjohan, W. W., & Martin, R. B. (2014). Trust, organizational justice, and whistleblowing: A research note. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 26(1), 157–168.

Seifert, D. L., Sweeney, J. T., Joireman, J., & Thornton, J. M. (2010). The influence of organizational justice on accountant whistleblowing. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 35(7), 707–717.

Shawver, T. J., & Clements, L. H. (2015). Are there gender differences when professional accountants evaluate moral Intensity for earnings management? Journal of Business Ethics, 131(3), 557–566.

Shawver, T. J., Clements, L. H., & Sennetti, J. T. (2015). How does moral intensity impact the moral judgments and whistleblowing intentions of professional accountants? Research on Professional Responsibility and Ethics in Accounting, 19, 27–60.

Singer, M. S. (1996). The role of moral intensity and fairness perception in judgments of ethicality: A comparison of managerial professionals and the general public. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(3), 469–474.

Soni, F., Maroun, W., & Padia, N. (2015). Perceptions of justice as a catalyst for whistle-blowing by trainee auditors in South Africa. Meditari Accountancy Research, 23(1), 118–140.

Taylor, E. Z., & Curtis, M. B. (2010). An examination of the layers of workplace influences in ethical judgments: Whistleblowing likelihood and perseverance in public accounting. Journal of Business Ethics, 93(1), 21–37.

Taylor, E. Z., & Curtis, M. B. (2013). Whistleblowing in audit firms: Organizational response and power distance. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 25(2), 21–43.

Thoradeniya, P., Lee, J., Tan, R., & Ferreira, A. (2015). Sustainability reporting and the theory of planned behaviour. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 28(7), 1099–1137.

Trongmateerut, P., & Sweeney, J. T. (2013). The influence of subjective norms on whistle-blowing: A cross-cultural investigation. Journal of Business Ethics, 112(3), 437–451.

Valentine, S., & Hollingworth, D. (2012). Moral intensity, issue importance, and ethical reasoning in operations situations. Journal of Business Ethics, 108(4), 509–523.

Vandekerckhove, W. (2006). Whistleblowing and organizational social responsibility: A global assessment. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Vera-Munoz, S. C. (2005). Corporate governance reforms: Redefined expectations of audit committee responsibilities and effectiveness. Journal of Business Ethics, 62(2), 115–127.

Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and motivation. New York: Wiley.

Wainberg, J., & Perreault, S. (2016). Whistleblowing in audit firms: Do explicit protections from retaliation activate implicit threats of reprisal? Behavioral Research in Accounting, 28(1), 83–93.

Webber, S., & Archambeault, D. S. (2015). Whistleblowing: Not so simple for accountants. The CPA Journal, 85(8), 62–68.

Wold, H. (1977). On the transition from pattern cognition to model building. In R. Henn & O. Moeschlin (Eds.), Mathematical economics and game theory: Essays in honor of Oskar Morgenstern (pp. 536–549). Berlin: Springer.

Wold, H. (1982). Soft modeling: The basic design and some extensions. In K. G. Jöreskog & H. Wold (Eds.), Systems under indirect observation: Causality, structure, prediction (Vol. 2, pp. 1–54). Amsterdam: North Holland.

Zhang, J., Chiu, R., & Wei, L.-Q. (2009). On whistleblowing judgment and intention: The roles of positive mood and organizational ethical culture. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 24(7), 627–649.

Zhong, C.-B., Ku, G., Lount, R. B., & Murnighan, J. K. (2006). Group context, social identity, and ethical decision making: A preliminary test. In A. E. Tenbrunsel (Ed.), Ethics in groups: Research on managing groups and teams (Vol. 8, pp. 149–175). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Acknowledgments

This article uses the statistical software SmartPLS 3 (http://www.smartpls.com). Ringle acknowledges a financial interest in SmartPLS.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

We aware of the contents and consent to the use of our names as an author of manuscript entitled “Whistleblowing Intentions Among Public Accountants in Indonesia: Testing for the Moderation Effects.”

Additional information

We thank anonymous reviewers, Steven Dellaportas (editor) for their valuable comments on prior versions of this paper.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Latan, H., Ringle, C.M. & Jabbour, C.J.C. Whistleblowing Intentions Among Public Accountants in Indonesia: Testing for the Moderation Effects. J Bus Ethics 152, 573–588 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3318-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3318-0