Abstract

Research on employees’ responses to corporate social responsibility (CSR) has recently accelerated and begun appearing in top-tier academic journals. However, existing findings are still largely fragmented, and this stream of research lacks theoretical consolidation. This article integrates the diffuse and multi-disciplinary literature on CSR micro-level influences in a theoretically driven conceptual framework that contributes to explain and predict when, why, and how employees might react to CSR activity in a way that influences organizations’ economic and social performance. Drawing on social identity theory and social exchange theory, we delineate the different but interdependent psychological mechanisms that explain how CSR can strengthen the employee–organization relationship and subsequently foster employee-related, micro-level outcomes. Contributions of our framework to extant literature and potential extensions for future research are then discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Whereas the focus on corporate social responsibility (CSR) has gained increasing attention in management literature and practice in the past 30 years, only recently has a micro-level perspective of CSR, intended to explain how employees respond to CSR activity (e.g., initiatives, policies) directed at themselves and other stakeholders, expanded into a particularly dynamic stream of research.

Nevertheless, the rapid expansion of this field of inquiry situated at the crossroads between various management-related disciplines (e.g., business ethics, organizational behavior and psychology, human resource management, marketing) has also created a largely fragmented literature that is, to a certain extent, loosely rooted in CSR’s historical debate and literature. Moreover, extant empirical research efforts can often be characterized as exploratory, as the theories underlying the potential of CSR to affect employees lack integrative and systematic testing and refinement (Morgeson et al. 2013; Rupp et al. 2013). As a consequence, few studies have truly acknowledged previous research contributions in this field, causing a tendency to repeatedly replicate the same kind of results. Furthermore, the lack of theoretical consolidation limits the generalizability of most findings, which prevents academics from fully fostering future development of this stream of research and managers from acting with confidence when advising and implementing CSR activity with employee-associated considerations in mind (Aguinis and Glavas 2012; Morgeson et al. 2013).

In this context, our overall objective is to develop theoretical foundations that are necessary to consolidate existing findings into a more homogeneous body of literature that will contribute to bridging CSR research efforts at the individual (micro) and organizational (meso) levels. For this purpose, we advance a dual-path, integrative theoretically driven conceptual framework that clarifies, at the micro-level of analysis, some of the main mechanisms explaining how organizations can best reap the returns from their social (and environmental) engagement. Specifically we argue that employees, as internal stakeholders, naturally form perceptions of internal CSR (or CSR-related initiatives directed at themselves) and external CSR (or CSR initiatives directed at other stakeholders), which can subsequently strengthen the employee–organization relationship (i.e., through organizational trust and identification) and, thus, employees’ propensity to support and contribute to the organization’s social and economic performance.

As suggested in existing literature (e.g., Farooq et al. 2014; Glavas and Godwin 2013; Gond et al. 2010), we rely on social identity theory (see Ashforth et al. 2008; Ashforth and Mael 1989; Pratt 1998) and social exchange theory (see Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005; Cropanzano and Rupp 2008; Emerson 1976), two of the most fundamental frameworks to understand how employees make sense of and navigate in the organizational milieu through relationship-building activities. In particular, in line with the self-enhancement motivation underlying social identity theory (Hogg et al. 1995; Smidts et al. 2001), we suggest that external CSR is more likely to foster employees’ organizational identification, consisting of the perception of oneness with or belongingness to an organization (Mael and Ashforth 1992). In addition, adopting a justice-based perspective of social exchange theory (Aryee et al. 2002; Cropanzano and Rupp 2008), we propose that internal CSR is more likely to foster organizational trust and, thus, employees’ propensity to enter into reciprocal exchanges with their employer (Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005).

With this conceptual endeavor, we address the critical need to consolidate and advance the psychological foundations of CSR (Aguinis and Glavas 2012). Moreover, our dual-path integrative framework drawing on social identity theory and social exchange theory provides a necessary scheme for the development of a constructive research agenda in this increasingly dynamic stream of research (Morgeson et al. 2013; Rupp and Mallory 2015).

The Business Case for CSR: Toward a Micro-Level Perspective

CSR can be characterized as an umbrella construct that comprises various concepts commonly interested in the relationship between business and society (see Glavas and Kelley 2014; Gond and Crane 2010; Waddock 2004). Although the definition of CSR has been debated for decades (see Carroll 1999), consistent across the various approaches is the idea that it refers to an organization’s discretionary initiatives (i.e., those that go beyond the letter of the law and corporate traditional economic activities) that preserve and contribute to social welfare (Barnett 2007; McWilliams and Siegel 2001; McWilliams et al. 2006a; Morgeson et al. 2013; Waldman et al. 2006). Typical CSR activity in this sense includes philanthropy and support to good causes, business- and strategy-integrated initiatives and policies (e.g., global responsibility standards adoption, environmental management systems and processes development, design of more sustainable products and services), and initiatives directed at employees’ psychological and emotional well-being (e.g., human rights protection initiatives, diversity policies, work–life balance programs) (Gond et al. 2011; Kotler and Lee 2005; Shen and Jiuhua Zhu 2011; Spiller 2000).

Although concerns about the impact of business on society can be traced for centuries (Carroll 1999), modern conceptions of social responsibilities associated with business activities are commonly attributed to Howard Bowen (1953). In his book Social Responsibilities of the Businessman, Bowen (1953, p. 6) emphasized, from a normative standpoint, “the obligations of businessmen to pursue those policies, to make those decisions, or to follow those lines of action which are desirable in terms of the objectives and values of our society.” From a more instrumental perspective, Bowen argued that free-market capitalism needed regulation and proposed that businesses’ social responsibility represented a corrective means to avoid, or at least minimize, firms’ negative externalities in pure laisser-faire capitalism (Acquier et al. 2011). Specifically, he stated that “voluntary assumption of social responsibility by businessmen is, or might be, a practicable means toward ameliorating economic problems and attaining more fully the economic goals we seek” (Bowen 1953, p. 6). However, at that time, the idea that a firm should be involved in the social arena was still particularly controversial and derided by many scholars, including Milton Friedman, the winner of the 1976 Nobel Prize in Economics, who claimed that the only social responsibility of firms was to maximize profit for shareholders (Friedman 1962, 1970).

A first significant attempt to reconcile defenders and opponents of the CSR cause was Carroll’s (1979) three-dimensional model of corporate social performance—addressing types of social responsibilities, social issues, and philosophy of response to such issues—which emphasized that companies’ social responsibilities (i.e., ethical and philanthropic) were not incompatible with traditional economic and legal obligations of a firm. However, studies trying to empirically demonstrate the existence of a direct link between CSR and economic performance have so far produced mixed results (McWilliams et al. 2006b; Peloza 2009; Roman et al. 1999), and meta-analyses have found only a mildly positive link between CSR and economic performance (see Margolis et al. 2009; Orlitzky et al. 2003), suggesting that there is not a simple yes or no answer to the question of whether it pays to be good. Consequently, research has called for further investigation of the underlying mechanisms and boundary conditions that drive and explain favorable returns of firms’ investments in CSR (Aguinis and Glavas 2012; Bhattacharya et al. 2009).

Research on the business case for CSR thus progressively evolved from a narrow perspective, which assumes only a direct relationship between CSR and economic performance, to a broader, more syncretic one, in which intermediate variables pertaining to stakeholders’ attitudes and behaviors are considered more likely to explain the CSR–performance relationship (Barnett 2007; Carroll and Shabana 2010; Perrini and Castaldo 2008). In this latter perspective, CSR actions are said to contribute to economic performance by decreasing transaction and agency costs with key stakeholders on which the organization depends for its survival (e.g., access to critical resources, license to operate) (Jones 1995; Waddock and Graves 1997). Accordingly, the positive returns of a firm’s social investment rely on its capacity to pursue CSR initiatives that promote key stakeholders’ well-being and, as such, foster trusting and cooperative relationships that attract stakeholders’ support to the organization (Barnett 2007; Jones 1995).

While most studies adopting this perspective have focused on external stakeholders (e.g., consumers, job seekers, shareholders) less attention has been paid to internal stakeholders’ reactions to CSR activity (Aguinis and Glavas 2012; Morgeson et al. 2013). Notably, literature in this domain remains largely spread out in a multiplicity of management-related disciplines and reflects a lack of clarity of the role of variables (whether there are antecedents, outcomes, moderators, or mediators of one another) suggested to determine employees’ reactions to CSR (Aguinis and Glavas 2012; Glavas and Kelley 2014). In this context, the provision of an inclusive and organized mapping of the micro-processes characterizing employees’ reactions to CSR activity would contribute to structure this stream of research and foster the emergence of a clearer and stronger business case that would support the legitimization of managers’ CSR investments on economic grounds (Aguilera et al. 2007; McWilliams and Siegel 2001).

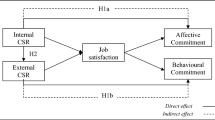

In line with a more syncretic perspective on the business case for CSR, our theoretically driven integrative framework addresses these challenges by delineating when, why, and how CSR activity can affect the employee–organization relationship in a way that fosters employees’ supportive attitudes and behaviors and, in turn, firms’ social and economic performance. For the sake of clarity, and consistent with existing structuring frameworks in organizational behavior and CSR-related literatures (e.g., Aguinis and Glavas 2012; Gond et al. 2010; Ilgen et al. 2005; Littlepage 1995), we divide and present our dual-path integrative conceptual framework into three sequential meta-categories (see Fig. 1): the input category (encompassing CSR meso-level activity and employees’ micro-level CSR perceptions), the process category (micro-level mediating mechanisms; a black box that needs to be opened), and the outcomes category (micro-level attitudes and behaviors, and meso-level performance indicators). In addition, our framework highlights three types of contingency factors (i.e., contextual/environmental, organizational, and individual level factors) that affect the extent to which CSR activity influences perceived CSR, employee-associated mediational mechanisms, and resulting outcomes.

The Input Category: From Meso-Level CSR Activity to Micro-Level Employee Perceptions

Extant literature suggests that it is employees’ subjective perceptions of CSR that influence their attitudes and behaviors, and thus their propensity to support their organization in achieving its social and economic goals (El Akremi et al. 2015; Glavas and Godwin 2013; Rupp et al. 2013). As such, we argue that perception of CSR, defined as a stakeholder’s evaluation of an organization’s impact on the well-being of its stakeholders and the natural environment (Glavas and Godwin 2013), represents the most appropriate independent variable to examine employees’ responses to CSR.

In addition, we posit that employees, as internal stakeholders, naturally distinguish between internal CSR activity (i.e., directed to employees’ well-being including, for example, policies aimed at improving working conditions and health and safety, specific training programs, or increased labor participation) and external CSR activity (i.e., directed to external stakeholders’ well-being including, for example, community and regional development, philanthropy and sponsorship, cross-sector social collaborations and partnerships, or promotion and development of social and environmental practices in the supply chain). This is consistent with arguments that employees as recipients and contributors experiencing direct corporate (social) behaviors develop self-related perceptions of CSR initiatives that they then distinguish from their perceptions of CSR initiatives targeting other stakeholders’ well-being (De Roeck et al. 2014; Hillenbrand et al. 2013). Thus we introduce the following proposition:

Proposition 1

Employees’ responses to CSR activity are mediated by their perceptions of CSR, which they cognitively categorize as ( a ) internal (self-related) or ( b ) external (other-related) initiatives.

The Process Category: Mechanisms Driving Employees’ Responses to Perceived CSR

A syncretic perspective on the business case for CSR suggests that the beneficial returns of investment in CSR depend on the capacity of CSR activity to increase the strength, or quality, of the relationship between an organization and its stakeholders (Barnett 2007; Bhattacharya et al. 2009; Jones 1995).

In line with such a view, we rely on social identity theory and social exchange theory to integrate the multi-disciplinary and fragmented literature investigating how perceived CSR can affect employees’ attitudinal and behavioral outcomes (see Table 1 in Appendix). We distinguish two processes that we highlight in Fig. 1 as the two horizontal and parallel paths that divide our figure: (1) the social identity theory path (labeled ‘SIT path’ in Fig. 1) through which perceived external CSR (ECSR in Fig. 1) impacts employees’ organizational identification (OI in Fig. 1) through the sequential mediation of perceived external prestige (PEP) and organizational pride; and (2) the social exchange theory path (labeled ‘SET path’ in Fig. 1) through which perceived internal CSR (ICSR in Fig. 1) impacts employees’ trust in the organization through the sequential mediation of overall justice (OJ in Fig. 1) and perceived organizational support (POS).

The Social Identity Mechanism: External CSR and Organizational Identification

Social identity theory argues that individuals partly define themselves through the construction of social identities containing “that part of an individual’s self-concept which derives from his knowledge of his membership of a social group (or groups) together with the value and emotional significance attached to that membership” (Tajfel 1978, p. 63). Social identification refers to the psychological process through which individuals categorize themselves into various social groups of reference (e.g., organizational, political, religious affiliations, and so forth) to reinforce their overall self-concept and thereby satisfy some higher-order psychological needs for self-esteem, belongingness, and meaningful existence (Pratt 1998).

Organizational identification corresponds to a specific form of social identification defined as a “perception of oneness with or belongingness to an organization, where the individual defines him or herself in terms of the organization in which he or she is a member” (Mael and Ashforth 1992, p. 104). Strongly identified employees intrinsically link their self-concept to their organization and thus typically develop attitudes and behaviors governed by their group membership (Dutton and Dukerich 1991; Pratt 1998).

According to the self-enhancement motivation that guides social identification, individuals have a basic need to see themselves in a positive light (i.e., an evaluative positive self-esteem) in relation to relevant others (Hogg et al. 1995; Pratt 1998). Building on this premise, research has argued that employees develop perceptions of their employer’s external prestige (i.e., perceived external prestige, hereafter labeled PEP), because external stakeholders’ admiration or disregard for the organization has implications for employees’ own reputation and, thus, sense of self-worth (Dutton and Dukerich 1991). More specifically, a well-reputed company makes group membership rewarding for employees, which creates a feeling of organizational pride, or “a sense of pleasure and self-respect arising from organizational membership” (Jones 2010, p. 859), which in turn fosters employees’ propensity to bask in the organization’s reflected glory through enhanced levels of identification (Bartels et al. 2007; Smidts et al. 2001).

Research efforts in the CSR field has hence begun investigating whether external CSR activity can positively affect an organization’s reputation (e.g., Fombrun and Shanley 1990; Minor and Morgan 2011; Sen and Bhattacharya 2001), which in turn might trigger employees’ self-enhancement process and related identification (Carmeli et al. 2007; Jones 2010; Kim et al. 2010). For example, Carmeli et al. (2007) demonstrate that employees’ organizational identification mediates the relationship between perceived external CSR (i.e., customer-related initiatives) and job performance. Kim et al. (2010) extend these preliminary findings to suggest that perceived external CSR (i.e., community donation initiatives) can positively affect employees’ organizational commitment through the mediating role of organizational PEP and identification. In the same vein, Jones (2010) finds that organizational pride and identification mediate employees’ responses (i.e., organizational citizenship behaviors [OCB], intent to stay) to volunteerism programs.

From the sum of these theoretical and empirical arguments, we suggest that external CSR can positively affect employees’ PEP, which then creates a rewarding feeling of membership (or organizational pride) and fosters their propensity to strengthen their relationship with the organization through enhanced levels of identification.

Proposition 2

Perceived external CSR affects employees’ level of organizational identification through the sequential mediation of PEP and organizational pride.

The Social Exchange Mechanism: Internal CSR and Organizational Trust

Although social identity theory explains how perceived CSR can affect employees’ attitudes and behaviors through group membership dynamics, it does not integrate the social norm of reciprocity and mutual obligations embedded in social exchange relationships (Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005; Gond et al. 2010). Contrary to economic exchange relationships, social exchange relationships are mainly associated with non-tangible assets whose price cannot be determined (see Shore et al. 2006), which usually make the terms of exchange rather unclear and, thus, essentially based on trust (Blau 1964). Trust is a relational marker that testifies of individuals’ “willingness to be vulnerable to the actions of the trustee on the basis of the expectation that the trustee will perform a particular action, irrespective of any monitoring or control mechanisms” (Colquitt and Rodell 2011, p. 1184). This willingness to put oneself at risk in relation to another is notably fostered by the trustor’s appraisal of the trustworthiness of the trustee, which relates to the ability, benevolence, and integrity of a trustee (Bhattacharya et al. 2009; Mayer et al. 1995).

Accordingly, the justice-based perspective of social exchange theory assumes that the way employees believe they are being treated by their organization (e.g., whether there are fairly treated, with benevolence and integrity) serves as a heuristic for trust (Cropanzano et al. 2001; Konovsky and Pugh 1994; Lind 2001). These beliefs thereby influence employees’ propensity to enter into an exchange relationship in which they might feel obligated to reciprocate the organization’s favors (Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005; Rhoades et al. 2001). In line with this assumption, trust has been empirically identified as a critical mediating mechanism to explain the link between organizational justice-based evaluations and employees’ outcomes such as job satisfaction, turnover intention, organizational commitment, and OCB (e.g., Aryee et al. 2002; Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005; Cropanzano and Rupp 2008). These findings are also corroborated by the perceived organizational support (hereafter POS) model of social exchange theory, which suggests that POS, or employees’ “global beliefs concerning the extent to which the organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being” (Eisenberger et al. 1986, p. 501), plays a mediating role in the relationship between organizational justice and subsequent trust (Stinglhamber et al. 2006).

In summary, from a social exchange theory perspective, we expect that employees use justice-based perceptions to evaluate whether the organization supports them as valuable and respected organizational members, which in turn foster organizational trust and the (felt) obligation to care about the organization’s welfare (Rhoades et al. 2001).

CSR scholars have shown that trust can mediate the relationship between perceived CSR and different work attitudes (i.e., OCB, intent to stay) (e.g., Hansen et al. 2011; Hillenbrand et al. 2013). These studies, largely influenced by relationship marketing literature in CSR (e.g., Perrini et al. 2010; Swaen and Chumpitaz 2008), assume that CSR activity signals an organization’s ethical attributes (e.g., integrity, benevolence) and, thus, the extent to which it can be trusted by employees (Mayer et al. 1995; Morgan and Hunt 1994). However, although these studies have offered new empirical findings, they appeared mostly as data-driven as they only relied implicitly on social exchange theory dynamics and largely ignored previous development in research about CSR micro-level outcomes such as those exploring the mediating process of organizational identification.

More recent studies have started to emerge with the objectives to consolidate previous findings while recognizing more clearly social exchange theory dynamics in the underlying processes explaining how perceived CSR can impact employee-associated outcomes. For example, De Roeck and Delobbe (2012) investigate whether external CSR activity (i.e., initiatives that protect and promote the natural environment) of a controversial petro-chemical company can reinforce organizational identification through the mediating role of organizational trust. This study’s findings indicate that employees use external CSR as a heuristic tool for trust-based evaluations which in turns foster their willingness to put themselves at risk through an enhanced level of identification with their organization. Farooq et al. (2014) complement these findings by clearly recognizing the importance of social exchange theory in explaining the mediating role of trust in the relationship between perceived CSR and specific employee-associated outcomes (i.e., organizational commitment).

De Roeck et al. (2014) further highlight that perceived internal and external CSR can both affect employee identification and job satisfaction by fostering increased levels of overall justice, or the holistic judgment about the fairness of their organization (Ambrose and Schminke, 2009). Additionally, their findings suggest that internal CSR has a much stronger impact on justice-based evaluations than external CSR, which can only be used as a heuristic to support employees’ self-focused justice evaluations—as how outsiders are treated provides clues to employees about how they, too, might be treated. In the same vein, Glavas and Kelley (2014) empirically confirm the potential mediating role of POS (a social exchange theory-related construct) in the relationship between perceived CSR (in particular, internal CSR) and employee-associated outcomes (i.e., organizational commitment and job satisfaction).

These insights collectively indicate that the impact of perceived CSR, particularly perceived internal CSR, on employees’ attitudes and behaviors can also be mediated by constructs pertaining to social exchange theory dynamics (i.e., overall justice, POS, and trust) beyond the mediating influence of social identity theory-related constructs (i.e., PEP, organizational pride and identification). This stream of research also suggests that rather than viewing these two theoretical frameworks as independent or compensatory/competing mediating processes, research should treat them as complementary processes that can influence each other in determining employees’ attitudinal and behavioral responses to perceived CSR. Therefore, in line with social exchange theory dynamics and the empirical evidences discussed, we propose the following:

Proposition 3

Perceived ( a ) internal and ( b ) external CSR affect organizational trust through the sequential mediation of overall justice and POS.

Proposition 3 (c)

Perceived internal CSR has a stronger impact on overall justice and subsequent outcomes than perceived external CSR.

Proposition 4

Variables pertaining to social exchange theory dynamics (e.g., overall justice, organizational trust) mediate the impact of perceived external CSR on organizational identification.

Outcomes Category: From Employee-Associated, Micro-Level Outcomes to Organizational, Meso-Level Outcomes

Building on previous CSR marketing-related research (Bhattacharya et al. 2009; Bhattacharya and Sen 2004), we propose that employee-associated, micro-level outcomes of CSR can best be conceptualized into three sub-categories: organization-oriented outcomes (i.e., directly linked to organizations’ prosperity), individual-oriented outcomes (i.e., directly linked to employees’ personal well-being), and society-oriented outcomes (i.e., directly linked to other stakeholders’ well-being).

Organization-Oriented, Employee-Associated, Micro-Level Outcomes of CSR

Prior research examining CSR’s potential to directly affect micro-level outcomes (see Table 2 in Appendix) has initially focused on the link between perceived CSR and organizational commitment, or the extent to which employees deem their own futures as tied to that of the organization and are willing to make personal sacrifices for it (Brammer et al. 2007; Maignan et al. 1999; Peterson 2004). Assuming that CSR signals some organization characteristics and ethical values that foster employees’ satisfaction and attachment to the organization (Brammer et al. 2007; Valentine and Fleischman 2008), scholars have further investigated the impact of perceived CSR on employees’ affective commitment (Mueller et al. 2012; Shen and Jiuhua Zhu 2011; Turker 2009), or their emotional attachment to and involvement in the organization (Allen and Meyer 1990). More recently, Rupp et al. (2013) report a link between perceived CSR and extra-role performance indicators, such as employee OCB, while Vlachos et al. (2014) integrate previous findings showing that affective commitment mediates the impact of perceived CSR on employees’ performance at work.

These studies’ findings are complemented by previously reviewed CSR research indicating that both organizational identification and trust (see Table 1 in Appendix) represent important relational markers that mediate the impact of perceived CSR on employees’ organizational (affective) commitment and related behaviors supporting an organization’s competitive goals (Ashforth et al. 2008; Colquitt et al. 2007; Riketta 2005; Schoorman et al. 2007). Thus, to the extent that employees’ attitudes (e.g., affective commitment) and behaviors (e.g., in-/extra-role performance, OCB, loyalty) do effectively influence organizational performance (see Angle and Perry 1981; Chun et al. 2013; Gong et al. 2009; Judge et al. 2001; McElroy et al. 2001; Podsakoff and MacKenzie 1997), these findings indicate that the success of CSR initiatives in improving an organization’s bottom line relies on its ability to foster strong relationships between the organization and its employees.

Proposition 5 (a)

Perceived internal and external CSR affect employee-associated, organization-oriented, micro-level outcomes (e.g., commitment, OCB, turnover intention, job performance) by strengthening the quality of the relationship (i.e., enhanced trust and organizational identification) between an organization and its employees.

Proposition 5 (b)

Employee-associated, organization-oriented, micro-level outcomes affect organizational economic performance.

Individual-Oriented, Employee-Associated, Micro-Level Outcomes of CSR

Recent research efforts at the micro-level have also contributed to the business case of CSR by highlighting the positive impact of perceived CSR on employees’ job satisfaction (De Roeck et al. 2014; Glavas and Kelley 2014; Valentine and Fleischman 2008), defined as “a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experiences” (Locke 1976, p. 1304), and which is recognized as a key antecedent of important micro-level, organization-oriented outcomes such as job performance, OCB, absenteeism, and turnover (Organ and Ryan 1995; Saari and Judge 2004; Wegge et al. 2007). As such, these research efforts also suggest that CSR initiatives can create win–win situations because they affect employees’ well-being, which can motivate employees’ support for organizational goals (i.e., improved economic and social performance resulting from the adoption of organization- and society-oriented extra-role behaviors) in exchange for the perceived personal benefits they associate with CSR initiatives. For example, De Roeck et al. (2014) suggest that internal and external CSR can contribute to employees’ job satisfaction because both foster identification, which helps employees satisfy their psychological need for self-esteem, belongingness, and a meaningful existence. Although these findings remain preliminary, we propose the following:

Proposition 6 (a)

Perceived internal and external CSR affect employee-associated, individual-oriented, micro-level outcomes by strengthening the quality of the relationship (i.e., enhanced trust and organizational identification) between an organization and its employees.

Proposition 6 (b)

Employee-associated, individual-oriented, micro-level outcomes indirectly affect an organization’s economic performance through its impact on employee-associated, organization-oriented, micro-level outcomes.

Proposition 6 (c)

Employee-associated, individual-oriented, micro-level outcomes indirectly affect an organization’s social performance through its impact on employee-associated, society-oriented, micro-level outcomes.

Society-Oriented, Employee-Associated, Micro-Level Outcomes of CSR

In their seminal contribution, Crilly et al. (2008) define two types of socially responsible behaviors: employees’ intention to enhance societal welfare (do good) and their intention to avoid harmful consequences for society (do no harm). Nevertheless, although an understanding of the factors that influence employees’ decisions to preserve or contribute to social welfare would be relevant, this research area remains at an embryonic stage of development in CSR literature. This is surprising because CSR initiatives provide many opportunities to educate and engage employees in socially responsible behaviors, such as through volunteerism programs, donation to charities supported by the organization, or the design, management, and promotion of CSR-related projects inside and outside the organization.

According to Crilly et al. (2008), individuals who “do good” or “do no harm” do not take such actions because they believe it makes sense for the organization’s economic performance. That is, instrumental rationality and economic calculation do not constitute essential drivers of employees’ behaviors at stake, which is consistent with the assumptions underlying our integrative framework based on social identity and social exchange theories. In this view, the mechanisms through which perceived CSR might affect employees’ willingness to engage in good deeds or avoid harmful deeds would be affected by the strength of the employee–organization relationship.

Consistent with this premise, Vlachos et al. (2014) show that perceived CSR can foster employees’ socially responsible behaviors by increasing their affective commitment and, thus, attachment to their organization. Jones’s (2010) study on volunteerism programs further shows that involvement in such CSR-related initiatives can strengthen exchange relationships and encourage employees to develop shared identities with the organization in terms of ethics and social values. In this context, we expect that identified employees of an organization they perceive as highly socially responsible will display socially responsible behaviors as a way to support their organization’s goals, such as social performance. On this basis, employees may even carry out some socially responsible behaviors outside any organizational/work context because their self-definition is tied to their organization’s socially responsible image and related character.

Proposition 7 (a)

Perceived internal and external CSR affect employee-associated, society-oriented, micro-level outcomes by strengthening the quality of the relationship (i.e., enhanced trust and organizational identification) between an organization and its employees.

Proposition 7 (b)

Employee-associated, society-oriented, micro-level outcomes (e.g., socially responsible behaviors) affect organizational social performance.

Contingency Factors

Extant micro-level research also indicates that the extent to which CSR activity influences perceived CSR, social identity, and social exchange mediational mechanisms, and resulting outcomes is dependent on contingency factors that we categorize as: (1) environmental/contextual, (2) organizational, and (3) individual factors. These factors, which moderate the whole process,Footnote 1 from CSR activity to CSR outcomes, appear in the upper gray box of Fig. 1.

Environmental/Macro-Contextual Contingency Factors

Kim et al. (2010), who explore the relationship between CSR and employees’ identification with their organization in a Korean context, suggest that employees in more collectivist cultures are more sensitive to CSR initiatives, which in turn likely strengthens the impact of perceived CSR on employees’ identification with and attachment to the organization. Building on this proposition, Mueller et al. (2012) empirically investigate the importance of national cultural contexts in moderating the impact of perceived CSR on affective organizational commitment. In their study, the overall measure of external CSR shows predictive validity for affective commitment and OCB, and these relationships appear stronger in national cultures that are higher in human orientation and institutional collectivism as well as in culture that are lower in power distance.

Emerging research also suggests that the industrial context in which an organization operates is likely to influence employees’ perceptions of and responses to CSR activity. For example, De Roeck and Delobbe (2012) conduct a study in the controversial petro-chemical industry and find no evidence of the mediating role of PEP between external CSR and employees’ identification, though other studies conducted in less controversial industry sectors do suggest such kind of relationship (see Jones et al. 2014; Kim et al. 2010). De Roeck and Delobbe suggest that belonging to a controversial industry might dampen the potential of an organization’s CSR activity to foster employee identification through a self-enhancement motivation. While we acknowledge that additional studies are warranted to investigate these assumptions, we contend the following:

Proposition 8

Environmental/macro-contextual contingency factors (e.g., cultural and industrial contexts) moderate the mediational processes among CSR activity, perceived CSR, and employees’ reactions to perceived CSR.

Organizational Contingency Factors

Some organizational factors can also affect the relationship among CSR activity, mediational constructs, and employee-associated, micro-level outcomes. First, CSR–organization fit, consisting of the perceived overlap between CSR activity and the organization’s operations, mission, and overall positioning (Becker-Olsen et al. 2006), can influence employees’ perceptions of and responses to CSR activity (Aguinis and Glavas 2013). Based on previous theoretical research (see Aguinis and Glavas 2013; Bhattacharya et al. 2009) we argue that “embedded CSR” approaches—which build upon the organization’s core competencies and entail the integration of CSR activity within an organization’s strategy, routines, and operations—characterized by a high CSR–organization fit can strengthen the propensity of CSR activity to generate more positive CSR perceptions and subsequently strengthen the impact of perceived CSR on employees’ psychological, attitudinal, and behavioral reactions.

Conversely, “peripheral CSR”—which includes initiatives that are not integrated into an organization’s strategy and therefore are characterized by a low level of CSR–organization fit—could be interpreted by organizational members as an attempt at window dressing and thus decrease or even reverse the potency of CSR activity to favorably affect employee-associated, micro-level outcomes. For example, an organization operating in a highly polluting industry that engages in CSR initiatives designed to fight breast cancer might face negative perceptions of and responses to its CSR activity because the company does not address the social problems caused by its core business operations (e.g., environmental impact, depletion of limited resource, workers’ safety).

In summary, with these conceptual arguments we expect that when employees perceive high CSR fit (i.e., embedded CSR), the impact of CSR activity on their perceptions of and responses to CSR will be stronger than when employees perceive low CSR fit, in which case the impact of CSR could even lead to perceptions of corporate irresponsibility and cause backfire effects on employees’ responses to perceived CSR.

A second organizational contingency factor that can moderate the underlying mechanisms and dynamics at play in our framework is CSR attribution, or the underlying motivation that employees attribute to their organization’s social engagement. Indeed, marketing literature on consumers’ reactions to CSR (or consumer-associated, micro-level impact of CSR activity)—and to a lesser extent literature on employees’ reactions to CSR (or employee-associated, micro-level impact of CSR activity)—emphasizes that self-centered/egoistic/instrumental CSR attributions (i.e., CSR initiatives viewed as a deliberate way to gain more profit for the organization) and other-centered/altruistic/genuine attributions (i.e., CSR initiatives viewed as developed for the sake of doing the right thing) can both influence stakeholders’ perceptions of and responses to CSR activity (Becker-Olsen et al. 2006; Ellen et al. 2006).

Vlachos et al. (2010) argue that egoistic motives can negatively affect sales force organizational trust, while more altruistic attributions positively influence their trust in the organization; however, they do not take perceived CSR into account in these dynamics. In this respect, De Roeck and Delobbe (2012) further show that an interaction effect can exist between perceived CSR and self-centered attribution, such that when perceived CSR increases (i.e., is better evaluated by employees), the increase in organizational trust is more pronounced for employees with higher self-centered CSR attributions than for employees with lower self-centered CSR attributions. Their results suggest that an instrumental approach to CSR can thus be acceptable in the eyes of employees as long as CSR initiatives seem to effectively increase social welfare and thus fulfill social objectives. In this respect, in adopting an internal, employee-focused viewpoint, these authors lend support to the argument that stakeholders’ suspicions and skepticism about CSR initiatives are not necessarily always driven by a firm’s instrumental-egoist approach to CSR, “but rather by a discrepancy between the stated objectives and firm action” (Becker-Olsen et al. 2006, p. 50). Thus, we propose the following:

Proposition 9

Organizational contingency factors (e.g., CSR–organization fit, CSR attribution) moderate the mediational processes among CSR activity, perceived CSR, and employees’ reactions to perceived CSR.

Individual Contingency Factors

Individual-related contingencies include socio-demographic characteristics and individuals’ attitudes toward CSR, reciprocity, and morality. From a socio-demographic perspective, characteristics such as gender can play a significant role in how employees perceive and react to CSR initiatives, as women tend to exhibit stronger preferences than men for companies’ discretionary actions, such as CSR (Brammer et al. 2007; Ibrahim and Angelidis 1994; Peterson 2004; Wehrmeyer and McNeil 2000). However, other personal characteristics, such as age and tenure, might also determine employees’ assessment of and responses to CSR activity within an organization and thus should be further investigated in future empirical research.

Beyond socio-demographic profiles, scholars have also investigated the moderating role of employees’ attitudes or sensibility toward CSR—or the extent to which an employee agrees that a firm has some social responsibilities beyond profit maximization (Turker 2009)—in determining their reactions to CSR activity. They stress that the CSR–commitment relationship is stronger among employees with higher levels of CSR sensitivity (Peterson 2004; Turker 2009).

Finally, previous research efforts in CSR have also explicitly addressed individual factors related to social identity and exchange theories that can moderate the mediating mechanisms that trigger employees’ attitudinal and behavioral response to CSR. Jones’s (2010) preliminary findings indicate that the previously evoked identification process explaining employees’ reactions to CSR is even stronger among individuals with a high social exchange ideology, because these individuals tend to have a stronger tendency to pay back favorable treatments through exchange relationships. Rupp et al. (2013) show that employees with higher moral identity, defined as the extent to which being a moral person is central to one’s self-definition, react more strongly to perceived CSR than employees with lower levels of moral identity. In summary, we propose the following:

Proposition 10

Individual contingency factors (e.g., sensibility to CSR, moral values/identity, socio-demographic variables) moderate the mediational processes among CSR activity, perceived CSR, and employees’ reactions to perceived CSR.

Discussion

Overall, our dual-path framework drawing on social identity theory and social exchange theory integrates and structures extant multi-disciplinary research efforts on employee-associated, micro-level impact of CSR activity (including studies in CSR, organizational behavior and psychology, human resource management). It contributes to establish the theoretical foundations that are needed to consolidate this previously disjointed field into a unified body of research. Our framework and propositions further highlight current gaps in existing literature and potentially fruitful research avenues, which we discuss subsequently.

Theoretical Contributions

Our conceptual effort contributes to existing literature by showing that the micro-level mediating processes between CSR activity, employees’ reactions, and organizational performance can be organized into three meta-categories (i.e., the input, the process, and the outcomes categories) and along two main theoretical paths that coherently bring together and rearrange previous insights into the dynamics underlying when, why, and how employees perceive and respond to CSR activity. In so doing, our dual-path, integrative framework both complements and extends earlier conceptual efforts aimed at contributing to the development of a more inclusive understandings of employees’ reactions to CSR activity and their potential impact on organizational performance (e.g., Aguinis and Glavas 2012; Glavas and Godwin 2013; Gond et al. 2010).

Regarding the input category, our framework indicates that a distinction needs to be made between objective measures of CSR organizational, meso-level activity (and underlying initiatives) and employees’ perceptions of these initiatives measured at the micro- (employee-) level of analysis. Regarding the measure of perceived CSR, we show that prior research has examined various underlying dimensions of CSR independently. That is, few studies have attempted to develop an appropriate scale to assess employees’ perceptions of CSR (El Akremi et al. 2015). In this respect, we underscore the notion that employees, as members and core constituents of an organization, will naturally make a distinction between CSR activity targeting their well-being (i.e., internal CSR) and activities targeting external stakeholders’ well-being (i.e., external CSR). Moreover, employees are often consumers, community members, and investors of their employing organization; therefore, they will logically develop, distinguish, and compare perceptions of internal and external CSR. Our framework clearly underlines the importance of this dimensionality when examining the mechanisms under which CSR activity can trigger employee-associated, micro-level perceptions and outcomes.

In accordance with a more syncretic perspective on the business case for CSR (Bhattacharya et al. 2009; Carroll and Shabana 2010), we also argue that social identity theory and social exchange theory both have the integrative explanatory potential to improve understanding of the micro-processes through which perceived CSR can strengthen the relationship between employees and their organizations. In this perspective, we articulate the black box surrounding these relationship-building processes in three sequential conceptual categories: (1) character/image perceptions, (2) status beliefs, and (3) relationship indicators (see Fig. 1). These conceptual categories bring more clarity about the role of variables (whether antecedents, outcomes, or mediators of one another) put forward in previous empirical and conceptual efforts to understand employees’ reactions to CSR.

First, under the assumption that CSR can traduce an organization’s ethical stance and soul (Becker-Olsen et al. 2006; Bhattacharya et al. 2009; Valentine and Fleischman 2008), we propose that perceived CSR can affect employees’ evaluations of their organization’s character, such as its level of prestige and overall justice. Second, we argue that employees rely on these identity-based cues to form beliefs about their organizational status in the eyes of external stakeholder and of their own employer. Specifically, in line with social identity theory, we expect that employees’ positive perceptions of their organization’s external prestige and social standing affect their pride in membership and, thus, their beliefs that they are viewed (by external stakeholders) as prestigious members of a reputable and appreciated organization (Jones 2010; Smidts et al. 2001). Moreover, in line with social exchange theory, we expect that perceptions of fair treatment can affect employees’ perceptions of organizational support and, thus, their beliefs that they are acknowledged as valuable and respected members by their employer (Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005; Tyler and Blader 2003).

Third, we show that both these mechanisms can affect the quality and strength of the employee–organization relationship. Indeed, on the one hand, social identity theory holds that organizational pride encourages people to identify with their employer (O’Reilly and Chatman 1986; Smidts et al. 2001; Tyler and Blader 2003). As such, employees’ attitudes and behaviors can be explained through the formation of a relationship in which the employee’s self-concept is intrinsically defined by his or her organizational membership, which in turn encourages him or her to support the organization’s objectives and performance (Mael and Ashforth 1992; van Dick et al. 2004). On the other hand, social exchange theory holds that organizational support mediates the impact of justice perceptions on organizational trust-based evaluations (Stinglhamber et al. 2006). From this perspective, employees’ attitudes and behaviors can be explained through a norm of reciprocity that leads them to support the organization through a relationship in which the terms of the exchange are essentially based on trust that the other party will reciprocate the provided efforts and benefits (Bhattacharya et al. 2009; Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005).

Regarding the outcomes category, we argue that existing literature has largely adopted a view of success that focuses almost exclusively on “hard” measures of performance (i.e., directly related to organizations’ economic performance) without sufficiently exploring “softer” success criteria (i.e., related more to employees’ and other stakeholders’ well-being) that also have the potential to reinforce the business (and social) case of CSR.

Finally, our framework also recognizes that employees’ perceptions of and responses to CSR activity are dependent on several contingency factors. While we acknowledge that the examples of contingency factors evoked in our conceptual work are not exhaustive, we illustrate three levels of contingent influences that should be addressed. First, at the individual level, we distinguish socio-demographic factors from character traits of an employee. Second, we highlight organizational factors linked to characteristics of the CSR activity which can influence employees’ perceptions of and responses to CSR (i.e., through CSR–organization fit and CSR attributions). Third, we stress the role of environmental/contextual factors and underscore the importance of cultural and industrial considerations in moderating the impact of CSR activity on employee attitudes and behaviors.

Directions for Future Research

Further Investigating Interactions Between Social Identity Theory and Social Exchange Theory Mechanisms

Regarding the impact of perceived internal and external CSR on employees’ psychological mechanisms (i.e., the process category), we advise future research efforts to further explore the interactions that might exist between the variables depicted in our two conceptual paths based on social identity and social exchange theories. Indeed, recent studies suggest that employees’ judgments of organizational fairness and whether they feel supported and respected by their organization (i.e., POS) moderate the relationship between perceived CSR and employees’ work attitudes and behaviors (Erdogan et al. 2015; Rupp et al. 2013). In particular, relying on a deontic view of justice, Rupp et al. (2013) show that first-party distributive justice (i.e., how fair the organization is in rewarding its members) can alter the relationship between external CSR (conceived as a special kind of third-party justice) and employees’ OCB. In the same vein, Erdogan et al. (2015) show that POS moderates the mediational relationship between employees’ perceptions of their managers’ involvement in CSR and their organizational commitment and OCB.

Based on the preliminary insights provided by these studies, we suggest that future research should address the question of whether and how perceived discrepancies between internal and external CSR, internal and external CSR-related organizational images (organizational justice and PEP), and/or internal and external status beliefs (i.e., POS and organizational pride) could create interaction effects that modify the strength or jeopardize the existence of a positive relationship between perceived CSR and employee-associated, micro-level outcomes. For example, if employees perceive their organization as investing greatly in external CSR while largely ignoring its own members’ well-being, their favorable reactions to external CSR might be hindered or even lead to backfire effects on their identification and subsequent work outcomes (Mallory and Rupp 2015). Additional research efforts focusing on such mechanisms would help explain the conditions under which CSR activity can lead to detrimental impacts in terms of employees’ attitudes and behaviors and subsequent effects on organizational performance.

Digging into the Counterproductive Effects of CSR Activity

The potential detrimental influence of CSR activity on employees’ attitudes and behaviors should further be explored through research efforts that would engage more deeply with the so-called ‘dark side’ of CSR. In certain cases, well-intended CSR initiatives might indeed trigger harmful workplace behaviors, such as work-related deviances (e.g., neglecting managers’ instructions, stealing, threatening the organization’s well-being by damaging property or reputation) (Bennett and Robinson 2000; Gond et al. 2010). Research has often examined such deviant behaviors under the lens of social exchange relationships, arguing that employees’ perceptions of an unfair organization can affect workplace deviance through a negative norm of reciprocity that “serves as a means to restore the balance and eliminates anger and frustration engendered by unfair treatment” (El Akremi et al. 2010, p. 63). Building on these insights, research could examine whether employees who believe that some CSR initiatives result in discriminating or unfair treatments of internal or external stakeholders (e.g., false promises about CSR investments; perceived misbalance in investments in internal and external CSR) go on to dis-identify with the organization and/or potentially engage in retaliation against it.

Addressing Unexplored Outcomes of CSR Activity

Finally, other research opportunities relate to the need to move beyond the traditional focus on the business case for CSR toward a more systematic investigation of “softer” performance criteria, such as those related to stakeholders’ well-being and their propensity to engage in socially responsible behaviors. For example, although internal CSR refers to an organization’s policies and practices related to employees’ physical and psychological well-being, few studies have constructively analyzed potential individual-oriented, employee-associated, micro-level outcomes of CSR, such as stress level and work–life balance (Aguilera et al. 2007; Parasuraman et al. 1996). Rodrigo and Arenas (2008) show that employees’ perceptions of their organization’s social role and image led many of them, who formerly felt that their organization was “just a place to work,” to view their employer as an institution sharing their own social views and values. These mechanisms might thus support employees’ transition from the workplace to the family environment and, as such, potentially reduce their work stress and its potential negative consequences (e.g., absenteeism, burnout).

Many relevant research avenues also can be associated with the phenomenon of employees’ socially responsible behaviors, as this research area is only emerging in mainstream organizational behavior and CSR literature. In this domain, we suggest that future research should engage in a more comprehensive identification of the conditions under which perceived CSR can more or less influences employees’ engagement in socially responsible behaviors. For example, research in leadership literature reports that ethical and responsible leaders are those who purposively try to infuse ethical and socially responsible behaviors among organizational members (Brown et al. 2005; Fehr et al. 2015; Trevino et al. 2000). Hence, employees’ perceptions of ethical leadership might be a boundary condition in determining the propensity of perceived CSR to influence employees’ socially responsible behaviors.

Conclusion

CSR has become a recurrent topic of conversation in scholarly literature, the classroom, the media, and the boardroom. It is now a management idea to which many companies across the globe cannot fail to give due care, as they feel the need to find adapted ways to address their social responsibilities and generate so-called ‘win–win opportunities’ for improving economic and social value. Nevertheless, corporate leaders and managers often engage in CSR initiatives in a diffuse and unfocused way (Du et al. 2010; Delmas and Burbano 2011) without fully understanding how they might affect key stakeholders’ perceptions and attitudes and whether and how they might, in fine, contribute to improve the company social and economic performance. For companies that do want to derive the most benefits from their CSR investments, our paper suggests that corporate leaders and managers should consider employees as constituting a critical bridge between internal and external CSR activity and its impact on economic and social performance of the firm. Overall, we believe our dual-path integrative framework can constitute an inspiring and useful blueprint aimed at helping to move forward the micro-level approach to CSR and support managers in designing CSR initiatives that truly impact their employees in a positive and supportive way.

Notes

Although we invite further research to theoretically determined where in the process a given moderator is more likely to exercise its influence, in our figure, and in line with mediated moderation best practice, we advised that the moderating impact of these factors should be tested along the whole mediational process to obtain reliable and robust results (see Edwards and Lambert 2007; Hayes 2013).

Abbreviations

- CSR:

-

Corporate social responsibility

- OCB:

-

Organizational citizenship behaviors

- PEP:

-

Perceived external prestige

- POS:

-

Perceived organizational support

References

Acquier, A., Gond, J.-P., & Pasquero, J. (2011). Rediscovering Howard R. Bowen’s legacy: The unachieved agenda and continuing relevance of social responsibilities of the businessman. Business and Society, 50(4), 607–646.

Aguilera, R. V., Rupp, D. E., Williams, C. A., & Ganapathi, J. (2007). Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 836–863.

Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2012). What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 38(4), 932–968.

Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2013). Embedded versus peripheral corporate social responsibility: Psychological foundations. Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice, 6(4), 314–332.

Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(1), 1–18.

Ambrose, M., & Schminke, M. (2009). The role of overall justice judgments in organizational justice research: A test of mediation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 491–500.

Angle, H. L., & Perry, J. L. (1981). An empirical assessment of organizational commitment and organizational effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 26(1), 1–14.

Aryee, S., Budhwar, P. S., & Chen, Z. X. (2002). Trust as a mediator of the relationship between organizational justice and work outcomes: Test of a social exchange model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(3), 267–286.

Ashforth, B. E., Harrison, S. H., & Corley, K. G. (2008). Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. Journal of Management, 34(3), 325–374.

Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20–39.

Barnett, M. L. (2007). Stakeholders influence capacity and the variability of financial returns to corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 794–816.

Bartels, J., Pruyn, A., de Jong, M., & Joustra, I. (2007). Multiple organizational identification levels and the impact of perceived external prestige and communication climate. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 28(2), 173–190.

Becker-Olsen, K. L., Cudmore, B. A., & Hill, R. P. (2006). The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research, 59(1), 46–53.

Bennett, R. J., & Robinson, S. L. (2000). Development of a measure of workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 349–360.

Bhattacharya, C. B., Korschun, D., & Sen, S. (2009). Strengthening stakeholder–company relationships through mutually beneficial corporate social responsibility initiatives. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(2), 257–272.

Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2004). Doing better at doing good: When, why, and how consumers respond to corporate social initiatives. California Management Review, 47(1), 9–24.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York: John Wiley.

Bowen, H. R. (1953). Social responsibilities of the businessman. New York: Harper & Row.

Brammer, S., Millington, A., & Rayton, B. (2007). The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(10), 1701–1719.

Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134.

Carmeli, A., Gilat, G., & Waldman, D. A. (2007). The role of perceived organizational performance in organizational identification, adjustment and job performance. Journal of Management Studies, 44(6), 972–992.

Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Academy of Management Review, 4(4), 497–505.

Carroll, A. B. (1999). Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Business and Society, 38(3), 268–295.

Carroll, A. B., & Shabana, K. M. (2010). The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(1), 85–105.

Chun, J. S., Shin, Y., Choi, J. N., & Kim, M. S. (2013). How does corporate ethics contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of collective organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Management, 39(4), 853–877.

Colquitt, J. A., & Rodell, J. B. (2011). Justice, trust, and trustworthiness: A longitudinal analysis integrating three theoretical perspectives. Academy of Management Journal, 54(6), 1183–1206.

Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., & LePine, J. A. (2007). Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: A meta-analytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 909–927.

Crilly, D., Schneider, S. C., & Zollo, M. (2008). Psychological antecedents to socially responsible behavior. European Management Review, 5(3), 175–190.

Cropanzano, R., Byrne, Z. S., Bobocel, D. R., & Rupp, D. E. (2001). Moral virtues, fairness heuristics, social entities, and other denizens of organizational justice. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58(2), 164–209.

Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900.

Cropanzano, R., & Rupp, D. E. (2008). Social exchange theory and organizational justice: Job performance, citizenship behaviors, multiple foci, and a historical integration of two literatures. In S. W. Gilliland, D. D. Steiner, & D. P. Skarlicki (Eds.), Justice, morality, and social responsibility (pp. 63–99). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

De Roeck, K., & Delobbe, N. (2012). Do environmental CSR initiatives serve organizations’ legitimacy in the oil industry? Exploring employees’ reactions through organizational identification theory. Journal of Business Ethics, 110(4), 397–412.

De Roeck, K., Marique, G., Stinglhamber, F., & Swaen, V. (2014). Understanding employees’ responses to corporate social responsibility: Mediating roles of overall justice and organisational identification. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(1), 91–112.

Delmas, M., & Burbano, V. (2011). The drivers of greenwashing. California Management Review, 54(1), 64–87.

Du, S., Battacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2010). Maximizing business returns to corporate social responsibility (CSR): The role of CSR communication. International Journal of Management Reviews, 47(1), 9–24.

Dutton, J. E., & Dukerich, J. M. (1991). Keeping an eye on the mirror: Image and identity in organizational adaptation. Academy of Management Journal, 34(3), 517–554.

Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 1–22.

Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 500–507.

El Akremi, A., Gond, J.-P., Swaen, V., De Roeck, K. and Igalens, J. (2015). How do employees perceive corporate responsibility? Development and validation of a multidimensional corporate stakeholder responsibility scale. Journal of Management.

El Akremi, A., Vandenberghe, C., & Camerman, J. (2010). The role of justice and social exchange relationships in workplace deviance: Test of a mediated model. Human Relations, 63(11), 1687–1717.

Ellen, P. S., Webb, D. J., & Mohr, L. A. (2006). Building corporate associations: Consumer attributions for corporate socially responsible programs. Academy of Marketing Science Journal, 34(2), 147–157.

Emerson, R. M. (1976). Social exchange theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 2, 335–362.

Erdogan, B., Bauer, T. N., & Taylor, S. (2015). Management commitment to the ecological environment and employees: Implications for employee attitudes and citizenship behaviors. Human Relations, 68(11), 1669–1691.

Farooq, O., Payaud, M., Merunka, D., & Valette-Florence, P. (2014). The impact of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: Exploring multiple mediation mechanisms. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(4), 563–580.

Fehr, R., Yam, K. C., & Dang, C. (2015). Moralized leadership: The construction and consequences of ethical leader perceptions. Academy of Management Review, 40(2), 182–209.

Fombrun, C., & Shanley, M. (1990). What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 33(2), 233–258.

Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Friedman, M. (1970). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. New york Times Magazine, September 13, 122–126.

Glavas, A., & Godwin, L. (2013). Is the perception of ‘goodness’ good enough? Exploring the relationship between perceived corporate social responsibility and employee organizational identification. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(1), 15–27.

Glavas, A., & Kelley, K. (2014). The effects of perceived corporate social responsibility on employees. Business Ethics Quarterly, 24(2), 165–202.

Gond, J.-P., & Crane, A. (2010). Corporate social performance disoriented: Saving the lost paradigm? Business and Society, 49(4), 677–703.

Gond, J.-P., El Akremi, A., Igalens, J., & Swaen, V. (2010). A corporate social responsibility–corporate financial performance behavioural model for employees. In C. Smith, C. B. Bhattacharya, D. Vogel, & D. Levine (Eds.), Global challenges in responsible business: Corporate responsibility and strategy (pp. 13–48). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gond, J.-P., Igalens, J., Swaen, V., & El Akremi, A. (2011). The human resources contribution to responsible leadership: An exploration of the CSR-HR interface. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(1), 115–132.

Gong, Y., Law, K. S., Chang, S., & Xin, K. R. (2009). Human resources management and firm performance: The differential role of managerial affective and continuance commitment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(1), 263–275.

Hansen, S., Dunford, B., Boss, A., Boss, R., & Angermeier, I. (2011). Corporate social responsibility and the benefits of employee trust: A cross-disciplinary perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(1), 29–45.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York: The Guilford Press.

Hillenbrand, C., Money, K., & Ghobadian, A. (2013). Unpacking the mechanism by which corporate responsibility impacts stakeholder relationships. British Journal of Management, 24(1), 127–146.

Hogg, M. A., Terry, D. J., & White, K. M. (1995). A tale of two theories: A critical comparison of identity theory with social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 58(4), 255–269.

Ibrahim, N. A., & Angelidis, J. P. (1994). Effect of board member’s gender on corporate social responsiveness orientation. Journal of Applied Business Research, 10(1), 35–41.

Ilgen, D. R., Hollenbeck, J. R., Johnson, M., & Jundt, D. (2005). Teams in organizations: From input-process-output models to IMOI models. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 517–543.

Jones, T. M. (1995). Instrumental stakeholder theory: A synthesis of ethics and economics. The Academy of Management Review, 20(2), 404–437.

Jones, D. A. (2010). Does serving the community also serve the company? Using organizational identification and social exchange theories to understand employee responses to a volunteerism programme. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(4), 857–878.

Jones, D. A., Willness, C., & Madey, S. (2014). Why are job seekers attracted by corporate social performance? Experimental and field tests of three signal-based mechanisms. Academy of Management Journal, 57(2), 383–404.

Judge, T. A., Thoresen, C. J., Bono, J. E., & Patton, G. K. (2001). The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin, 127(3), 376–407.

Kim, H.-R., Lee, M., Lee, H.-T., & Kim, N.-M. (2010). Corporate social responsibility and employee–company identification. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(4), 557–569.

Konovsky, M. A., & Pugh, S. D. (1994). Citizenship behavior and social exchange. Academy of Management Journal, 37(3), 656–669.

Kotler, P., & Lee, N. (2005). Corporate social responsibility: Doing the most good for your company and your cause. NJ: John Wiley.

Lind, E. A. (2001). Fairness heuristic theory: Justice judgments as pivotal cognitions in organizational relations. In J. Greenberg & R. Cropanzano (Eds.), Advances in organizational justice (pp. 56–88). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Littlepage, G. E., Schmidt, G. W., Whisler, E. W., & Frost, A. G. (1995). An input-process-output analysis of influence and performance in problem-solving groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 877–889.

Locke, E. A. (1976). The nature and consequences of job satisfaction. In M. D. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial organizational psychology (pp. 1297–1349). Chicago: Rand McNally.

Mael, F., & Ashforth, B. E. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13(2), 103–123.

Maignan, I., Ferrell, O., & Hult, G. (1999). Corporate citizenship: Cultural antecedents and business benefits. Academy of Marketing Science Journal, 27(4), 455–469.

Mallory, D., & Rupp, D. E. (2015). “Good” leadership: Using corporate social responsibility to enhance leader-member exchange. In T. N. Bauer & B. Erdogan (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of leader member exchange. New York: Oxford University Press.

Margolis, J. D., Elfenbein, H. A., & Walsh, J. P. (2009). Does it pay to be good… and does it matter? A meta-analysis of the relationship between corporate social and financial performance. Unpublished manuscript, (March 1, 2009). SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1866371 or 10.2139/ssrn.1866371.

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734.

McElroy, J. C., Morrow, P. C., & Rude, S. N. (2001). Turnover and organizational performance: A comparative analysis of the effects of voluntary, involuntary, and reduction-in-force turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(6), 1294.

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (2001). Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 117–127.

McWilliams, A., Siegel, D. S., & Wright, P. M. (2006a). Corporate social responsibility: Strategic implications. Journal of Management Studies, 43(1), 1–18.

McWilliams, A., Siegel, D., & Wright, P. M. (2006b). Introduction by guest editors corporate social responsibility: International perspectives. Journal of Business Strategies, 23(1), 1–18.

Minor, D., & Morgan, J. (2011). CSR as reputation insurance: Primum non nocere. California Management Review, 53(3), 40–59.

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38.

Morgeson, F. P., Aguinis, H., Waldman, D. A., & Siegel, D. S. (2013). Extending corporate social responsibility research to the human resource management and organizational behavior domains: A look to the future. Personnel Psychology, 66(4), 805–824.

Mueller, K., Hattrup, K., Spiess, S.-O., & Lin-Hi, N. (2012). The effects of corporate social responsibility on employees’ affective commitment: A cross-cultural investigation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(6), 1186–1200.

O’Reilly, C., & Chatman, J. (1986). Organizational commitment and psychological attachment: The effects of compliance, identification, and internalization on prosocial behaviour. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 492–499.

Organ, D. W., & Ryan, K. (1995). A meta-analytic review of attitudinal and dispositional predictors of organizational citizenship behavior. Personnel Psychology, 48(4), 775–802.

Orlitzky, M., Schmidt, F. L., & Rynes, S. L. (2003). Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organization Studies, 24(3), 403–441.

Parasuraman, S., Purohit, Y. S., Godshalk, V. M., & Beutell, N. J. (1996). Work and family variables, entrepreneurial career success, and psychological well-being. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 48(3), 275–300.

Peloza, J. (2009). The challenge of measuring financial impacts from investments in corporate social performance. Journal of Management Studies, 35(6), 1518–1541.

Perrini, F., & Castaldo, S. (2008). Editorial introduction: corporate social responsibility and trust. Business Ethics: A European Review, 17(1), 1–2.

Perrini, F., Castaldo, S., Misani, N., & Tencati, A. (2010). The impact of corporate social responsibility associations on trust in organic products marketed by mainstream retailers: A study of Italian consumers. Business Strategy and the Environment, 19(8), 512–526.

Peterson, D. K. (2004). The relationship between perceptions of corporate citizenship and organizational commitment. Business and Society, 43(3), 296–319.

Podsakoff, P. M., & MacKenzie, S. B. (1997). Impact of organizational citizenship behavior on organizational performance: A review and suggestion for future research. Human Performance, 10(2), 133–151.

Pratt, M. G. (1998). To be or not to be? Central questions in organizational identification. In D. A. Whetten & P. Godfrey (Eds.), Identity in organizations: Building theory through conversations (pp. 171–207). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rhoades, L., Eisenberger, R., & Armeli, S. (2001). Affective commitment to the organization: The contribution of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(5), 825–836.

Riketta, M. (2005). Organizational identification: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66(2), 358–384.

Rodrigo, P., & Arenas, D. (2008). Do employees care about CSR programs? A typology of employees according to their attitudes. Journal of Business Ethics, 83(2), 265–283.

Roman, R. M., Hayibor, S., & Agle, B. R. (1999). The relationship between social and financial performance: Repainting a portrait. Business and Society, 38(1), 109–125.

Rupp, D. E. (2011). An employee-centered model of organizational justice and social responsibility. Organizational Psychology Review, 1(1), 72–94.

Rupp, D. E., & Mallory, D. B. (2015). Corporate social responsibility: Psychological, person-centric, and progressing. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 2(1), 211–236.

Rupp, D. E., Shao, R., Thornton, M. A., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2013). Applicants’ and employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: The moderating effects of first-party justice perceptions and moral identity. Personnel Psychology, 66(4), 895–933.

Saari, L. M., & Judge, T. A. (2004). Employee attitudes and job satisfaction. Human Resource Management, 43(4), 395–407.