Abstract

Whistleblowing refers to the disclosure by organization members of illegal, immoral, or illegitimate practices to persons or organizations that may be able to effect action. Most studies on the topic have been conducted in North American or European private sector organizations, and less attention has been paid to regions such as Turkey. In this study, we study the whistleblowing intentions and channel choices of Turkish employees in private and public sector organizations. Using data from 327 private sector and 405 public sector employees, we find that public sector employees are more idealistic and less inclined to whistleblow externally and anonymously. Higher idealism among public sector employees does not moderate these effects. We find that private sector employees are more relativistic, and that they are more inclined to whistleblow through external and anonymous channels. More relativistic private sector employees are more likely to prefer external whistleblowing; however sector does not moderate the propensity to whistleblow anonymously.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Whistleblowing has been defined as “the disclosure by organization members (former or current) of illegal, immoral, or illegitimate practices under the control of their employers, to persons or organizations that may be able to effect action” (Near and Miceli 1985, p. 4). Often the goal is to warn the public about a serious wrongdoing created within or masked by the organization (Bolsin et al. 2005). The topic has become a much-studied research field in recent years, as management fraud and employee theft have been found to be potentially very costly to organizations. According to Sweeney (2008), one-third of deviant cases within companies are discovered through information from whistleblowers. Their tips prove even more effective in revealing fraud than internal or external audits. Coworkers willing to monitor their peers’ behaviour and report violations to management represent therefore a potentially important supplemental control resource for organizations (Treviño and Victor 1992).

In spite of the huge potential the topic entails, the interest of media has been outpacing the growth of academic research on the issue (Near and Miceli 2005). Already in the 1980s, Dozier and Miceli (1985) stated that a continued study of whistleblowing would be helpful in the development of organizational policies that enable legitimate whistleblowers to come forward. Ever since, significant research has investigated the antecedents of whistleblowing. Most studies have favoured demographic and rational decision-making processes when examining whistleblowing decisions (Miceli and Near 1984, 1988; Near and Miceli 1996). The values, emotions and personality aspects of whistleblowers have been studied more rarely. Some authors have pointed out that a purely rational approach to whistleblowing may not be sufficient to identify its predictors and that the ethical orientation of the individual, i.e. whether he/she is idealistic or relativistic (Forsyth 1980) may influence whistleblowing decisions as well.

Most studies on whistleblowing have concentrated on private sector organizations. The question whether whistleblowing in the private sector compares to feelings and actions in the public sector has not been investigated sufficiently. As Rainey (2009) correctly notes, the mainstream research literature assumes that public–private differences are trivial. Especially in recent years, this similarity has been taken for granted, as in many countries, public sector organisations have started to import managerial processes and behaviours from the private sector (Box 1999; Carroll and Garkut 1996; Hood 1991). Although the transfer of management techniques between sectors rests on the underlying assumption that “management is management” (Murray 1975), it is questionable whether the values of the private sector translate readily into the public sector given that a defining role of the public service is the “primacy of the public interest” (Preston 2000, p. 17). Studies on the differences between public and private organizations focus only on dimensions such as ownership, funding and social control (Bozeman 1987; Perry and Rainey 1988), and only limited attention is devoted to different ethical positions of employees and their consequences. O’Kelly and Dubnick (2005) have stated that the ways in which public administrators make decisions in the face of dilemmas and in the context of bureaucracies should be investigated more in depth.

Most whistleblowing studies have been conducted in North America and Western European countries, whereas less attention has been paid to regions such as Turkey. This puts the generalizability of findings into question, as people with different cultural upbringings and living under different socioeconomical influences may not share necessarily the same views of what is ethical or unethical (Chen 2001; Patel 2003), although they may be included in the same culture cluster as Poland and Albania in the global leadership and organizational behavior (GLOBE) Research Program (House et al. 1999) The reactions of company management may also differ from those of the Western countries. For example, in a study at 15 private sector companies in Kazakhstan, more than 50 % of respondents stated that when they expressed their opinions on certain problematic matters within their organizations, their efforts were neglected and they received no viable and feasible answer to their enquiries (Kunanbayeva and Kenzhegaranova 2013). Treviño and Brown (2004) showed that Kazakhstani managers tended to be “ethically silent leaders” who are more concerned about financial results than holding people accountable for their (un)ethical behaviour. The study of Sutherland (2013) in the telecommunications sector led to similar findings in Uzbekistan. Also the interpretation of concepts such as responsiveness, fairness and integrity (Cooper 1991; Lewis 1991), which commonly represent so called “public sector values” may be different in some developing countries. Bardhan (1997) for example argues that in many emerging economies corruption—especially in the public sector—is the biggest problem. The silence of theorists on this issue is therefore surprising. Also in Turkey, where the present study is set, there are relatively high levels of public sector corruption (Transparency International 2011). Although steps have been set to address corruption challenges in Turkey and major international anticorruption conventions have been signed (Transparency International 2011), the issue continues to be a problem. Studies on ethical behaviour in developed countries may not necessarily have any lessons for organizations in emerging economies such as Turkey, because of the relative weakness of robust legal systems and cultural dimensions such as collectivism. Even in countries which are in the same cultural cluster as Iran and Turkey, attitudes to whistleblowing and channels preferred to report wrongdoing may differ. The study of Oktem and Shahbazh (2012) for example demonstrated using a sample of students that both respondents in Iran and Turkey tended to blow the whistle internally, but that Iranian students preferred to do this informally, whereas Turkish students expressed their complaints formally. In Turkey, whistleblowing is perceived as a negative act, and complaining openly about ethical misconduct such as bribery is not common. Many individuals do not lodge formal complaints out of fear of potential harassment and reprisal (Transparency International 2009). This is particularly true for victims of bribery in Turkey. We argue that also religious orientation may have an effect on ethical decision making, as stated by Woiceshyn (2011). As Turkey is a predominantly Islamic country, especially devout Muslims may refrain from whistleblowing basing them selves on sections in religious phrases such as ‘do not seek Muslims’ dishonors…’ or statements of the Prophet Muhammad such as ‘do not seek your intimates’ (Kandemir 2012). Nevertheless, whistleblowing may be a useful deterrent to correct misconduct, yet little is known about attitudes towards whistleblowing in Turkey (see Nayir and Herzig 2012; Park et al. 2008). As researchers stress the necessity to further examine these relationships, an attempt is being made to find out the factors that affect whistleblowing in private and public sector organizations of Turkey, an under-researched country.

The above-mentioned considerations give rise to the following research questions: Given that employers should prefer that employees report perceived wrongdoing through internal channels, rather than resort to external whistleblowing, how can organizational leaders in emerging countries such as Turkey ensure that they are informed of possible wrongdoing? How should whistleblowing be encouraged in private and public sectors? Do the same mechanisms work, just because both sectors are becoming similar due to “new public sector” managerialism? If there are differences, should organizations in both sectors then design varying mechanisms to encourage whistleblowing? Moreover, what should these different mechanisms look like, i.e. where should their emphasis be?

In this article, we study the whistleblowing intentions and channel choices of Turkish employees in private and public sector organizations. Whistleblowing intention is an individual’s probability of choosing whistleblowing under certain circumstances (Zhang et al. 2009). According to the theory of planned behaviour, intention is a good predictor of actual behaviour (Ajzen 1991). The decision to study whistleblowing intention rather than actual whistleblowing action is justified due to the difficulty of carrying out investigations of unethical conduct in the workplace by first-hand observation (Victor et al. 1993). Thus, whistleblowing intention is deemed appropriate in the context of this study.

The purpose of this study is to address the research gaps identified above. The remainder of this article is organized as follows: First, the theoretical background is presented with specific focus on ethical positions and whistleblowing in public/private sectors, followed by our hypotheses. Then, country setting, sampling, and data collection are described. Next, measurement, and construct reliability and validity are delineated, followed by our analyses and the results obtained. The article ends with a discussion of our findings, their implications to theory and practice as well as future research directions.

Literature Review

Whistleblowing in the Private and Public Sectors

It has been rather difficult to make a clear distinction between public and private sectors as especially in today’s world, organizations are characterized by a variety of structural forms combining various aspects of the public and private sectors (Hvidman and Andersen 2014). Scholars have emphasized that both types of organizations, and all of the intermediate organizational forms, are to some degree regulated by political authority (Bozeman 1987). Still, similarities and differences between public and private organizations have been constituting a research topic that has aroused much interest (Hvidman and Andersen 2014).

Some studies claim that public and private sector organizations have many similarities and that employees in both types of organizations merely respond to the incentives they are offered and the opportunities and constraints of the organizations in which they work (Brewer and Brewer 2011). These views have been supported by changes that have been going on in the public sector to shift attention from rules and input regulation to goal setting and the use of performance information to improve public sector performance (Hood 1991; Pollitt and Bouckaert 2004). However, studies have shown that private and public sector values are actually very different. In general, private sector employees have organizational and job attitudes that are different from those of public sector employees (Karl and Sutton 1998; Naff and Crum 1999). This is partly due to the need to be open to market forces and respond to the environment effectively (Meier and O’Toole 2011). Public organizations, on the other hand, have massive processes to buffer the environment (O’Toole and Meier 2003) and are therefore less concerned about organizational adaptation. One another difference between the two sectors is related to relationships with stakeholders. Customers are the most important stakeholder group in the private sector, and the desire of firms is to meet their demands as well as possible (Boyne 2002). In the public sector, rather than customers, working relationships between public sector officials and a range of other stakeholders such as officials in other departments, governmental ministers, elected officials, ministerial staff, and members of the wider community are central.

Reviews of the relevant literature reveal that work motivation among public sector employees and managers is very different from that of their private sector counterparts (Ambrose and Kulik 1999; Rainey and Bozeman 2000; Wittmer 1991; Wright 2001). Public sector employees show a stronger service ethic and more often make a choice to deliver a more worthwhile service to society (Rainey 1982) than private sector employees (Wittmer 1991). Unlike their private sector counterparts, public sector employees are motivated by a strong desire to serve (Boyne 2002; Perry 2000; Perry and Wise 1990) and promote the public interest (Box 1999). The traditional public sector ethos is characterized by O’Toole and Meier (2003) as setting aside personal interests, working altruistically for the public good and working with others in a collegial and anonymous manner. Frederickson (1997) refers to “the calling of the public service” as being at the heart of the spirit of public administration.

Although the topic of whistleblowing has been primarily studied within private sector organizations, some studies in the public sector have investigated the phenomenon. Johnson (2003) concentrated on external whistleblowers, and O’Leary (2006) on government guerrillas in the public sector. Several studies of whistleblowing by the US federal employees have been published primarily using data collected by surveys from the Merit Systems Protection Board (Near and Miceli 2008). Brewer and Selden (1998) examined whistleblowing among federal employees as an act consistent with the public service ethic. Their study found that whistleblowers are more likely to possess public service motivation than individuals who observe but do not report inappropriate acts. Although this is the case, especially peers in public organizations have been shown to wrestle with the government code of being loyal to the highest moral principle (Johnson 2003) and loyalty to immediate colleagues, which is often much stronger than loyalty to the organization (e.g. Heck 1992). In the public sector, therefore, wrongdoing is often not reported at all. In a study of corruption, the peers of corrupt officials often had suspicions— sometimes even evidence—that something was wrong long before the investigation, but kept the information to themselves (De Graaf and Huberts 2008).

Whistleblowing has largely been divided into external and internal whistleblowing, based on the channels by means of which the wrongdoing is reported (Park et al. 2005; Park et al. 2008). External whistleblowing refers to the disclosure of the wrongdoing committed in the organization to someone outside of that organization (e.g. the media), whereas in the case of internal whistleblowing, the wrongdoing is reported to somebody within the organization (Elliston 1982a) as a form of lateral control (King 2000). Both can be done either anonymously, i.e. without the whistleblower disclosing his/her name, or in an identified manner (Park et al. 2008). Internal whistleblowing has been considered less harmful than external, as alerting internal organizational bodies about poor practice or other issues of concern, has been considered acceptable and desirable behaviour (Carson et al. 2008). Whereas internal reporting does not necessarily involve a breach of confidentiality (Firtko and Jackson 2005), embarrassing publicity is an inevitable outcome of external whistleblowing (Gobert and Punch 2000). A number of researchers have specifically linked external whistleblowing to the absence of a well-managed internal reporting apparatus (Tavakolian 1994).

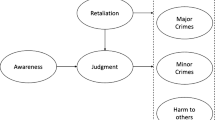

Ethical Position as Determinant of Preferred Whistleblowing Channel

Whistleblowing has been associated with some personal characteristics (gender, self-esteem, personality traits, religion) and situational aspects (type of alleged wrongdoing, quality of supervision, status of the recipient, organizational integrity policy, and so on). Since persons going against the dominant forces in a setting are seen as acting more according to their personalities (Kelley 1972), it also seems possible that whistleblowers could be viewed as less influenced by situational variables and more by their personalities (Decker and Calo 2007; Bjørkelo et al. 2010). Whistleblowing poses ethical dilemmas for both the employee and the employer. For the employee, there are questions of motive, fairness, loyalty, cooperativeness, and moral obligation (Elliston 1982a, b). According to Church et al. (2005), a person’s level of moral development also has a dramatic effect on behaviour. Personal moral philosophy is one of the determinants of ethical decision making (Forsyth 1980; Fraedrich and Ferrell 1992; Fritzsche and Becker 1984; Hunt and Vitell 1986; Barnett et al. 1994; Hunt and Vasquez-Parraga 1993). A personal moral philosophy refers to the framework used by an individual to decide on an ethical dilemma (Barnett et al. 1994), helping him to make ethical judgments (Forsyth and Nye 1990). According to Forsyth (1992) personal moral philosophies influence perceptions of certain business practices and decisions related to them. Ethics is about human relationships and how we, as human beings, ought to act and relate to one another (Freakley and Burgh 2000).

Whistleblowing has often been referred to as the voice of conscience and in some cases disloyalty against the organization may disrupt business and damage the image of the company. Differences amongst individuals in their acceptance of ethical philosophies are seen to affect their ethical judgments and behavioural intentions (Fraedrich and Ferrell 1992; Fritzsche and Becker 1984; Hunt and Vitell 1986) as they provide a framework within which individuals contemplate issues of right and wrong (Fraedrich and Ferrell 1992). A person’s assessment of the ethicality of whistleblowing may therefore also affect his/her intention as to whether or not to engage in the practice (Appelbaum et al. 2006). Forsyth (1980) argues that relativism and idealism are two basic dimensions of personal moral philosophies that have a profound impact on business ethical decisions. Idealism is defined as the extent to which an individual believes that ethically correct actions will consistently produce desirable outcomes (Forsyth 1980). Relativism on the other hand refers to the extent to which individuals accept universal moral principles as the basis for ethical decisions (Forsyth 1980). Idealistic individuals feel that harming others is always avoidable, meaning they would rather not choose between the lesser of two evils which will lead to negative consequences for other people (Forsyth 1992). Individuals, who are less idealistic, in contrast, pragmatically assume that in some cases harm is unavoidable, and that one must sometimes choose between the lesser of two evils. Idealistic individuals tend to be very strict when making moral judgments, especially if the action harms others or violates universal moral principles (Forsyth 1992). Studies also reveal that in general idealistic individuals are more likely to blow the whistle than are more relativistic individuals (Arnold and Ponemon 1991; Brabeck 1984). In a situation where they observe wrongdoing in their organization, idealists may act out of a sense of duty, even if this is opposed to organizational and situational pressures (Vinten 1995), whereas relativists may be less concerned. Relativistic individuals generally feel that no universal ethical rules exist that apply to everyone (Beekun et al. 2005; Robertson et al. 2001) and moral actions depend upon the nature of the situation and the individuals involved (Forsyth 1992). Highly relativistic individuals’ moral judgments are configural, for they base their appraisals on features of the particular situation and action they are evaluating (Forsyth 1980).

Numerous studies have tried to understand the influence of individual moral philosophy on reactions to observed organizational wrongdoing. Idealism and relativism have been shown to influence organizational deviance (Henle et al. 2005); perceived ethical problem (Hunt and Vitell 1986); perceived importance of ethics and social responsibility (Singhapakdi et al. 1995) and ethical judgment (Vitell and Singhapakdi 1993), among others. Some studies have looked at explicit influences according to sector. Investigating ethical position in the private sector, Nayir and Herzig (2012) show that potential whistleblowers are generally reluctant to express their observations about organizational wrongdoings to external parties and if they were intending to blow the whistle, they would do it with the highest level of anonymity. Also public managers are often confronted with ethical dilemmas as they endeavour to choose options amongst competing sets of principles, values and beliefs. Badaracco (1992) refers to these competing sets of principles as “spheres of responsibility” that have the potential to ‘pull [managers] in different directions’ (p. 66) and thus create ethical dilemmas for them. Although studies show that whistleblowing injures the employer’s reputation, individuals may sometimes feel a greater need to be loyal to their own perceptions of right and wrong (Bather and Kelly 2006). According to Johnson (2003 p. 27), ‘… loyalty can be seen as a devotion to a cause and the way we choose between loyalties is to choose the cause that is more compelling’.

Hypotheses

Ethical Position and Preferred Channels in the Public Sector

In contrast to the private sector, employment in the public sector has often been portrayed as a calling, a sense of duty, rather than a job (Pattakos 2004; Perry 1996). Individuals who respond to this call are characterized by an ethic built on benevolence, a life in service of others, and a desire to affect the community (Houston 2006). Studies show that public employees are motivated more by meaningful work (Crewson 1997; Rainey 1982; Wittmer 1991) whereas in the private sector rewards of extrinsic nature, such as higher pay are considered motivators (Jurkiewicz et al. 1998; Rainey 1982; Wittmer 1991).

Public officials are often required to choose among multiple and complex values, thus making their decisions contestable (Preston 1994). When asked about the relative importance of behaving ethically correct, Berman and West’s (2011) study, showed that more than two-thirds of public employees in various sectors reported that they considered ethical behaviour to be very important. More than 60 percent of respondents regarded accountability to the governing board as very important. Callender (1998) observes that a sense of public service and a strong emphasis on ethical behaviour provide part of the professional identity of the public service practitioner. As public officials are often portrayed as “principled agents” (Brehm and Gates 1997), who are believed to be less materialistic than their private sector counterparts (Boyne 2002) we assume that

Hypothesis 1

In general, public sector employees are more idealistic than employees in the private sector.

Studies have shown that differences exist between external and internal whistleblowing in terms of the seriousness of the wrongdoing whistleblowers witness, the retaliation they experience, and the effectiveness of their intervention (Dworkin and Baucus 1998). If individuals report internally, organizations have the opportunity to detect the wrongdoing as early as possible, limiting the negative consequences. Further, if it becomes well known that individuals are willing to report wrongdoing, this may also serve as a preventive function and discourage employees from engaging in wrongdoing. Internal whistleblowing also gives the organization a greater chance to avoid the negative consequences potentially brought on by external whistleblowing (Miceli and Near 1988).

Several studies have found that external disclosures are likely when employees believe that the organization would ignore their complaints (Miceli and Near 1988). Near and Miceli (1985) state that observers of wrongdoing who are well acquainted with the ineffectual operation of a formal complaint recipient may decide that another action, or no action, would be more appropriate than whistleblowing through that channel. If an employee chooses to step outside and whistleblow to external channels, the act gives the impression that fault lies with the person in a position of authority (Evans 2008). External whistleblowing therefore tends to cause greater damage to an employee’s coworkers and the employer than internal whistleblowing. As people with an idealistic ethical orientation believe it is always possible and desirable to avoid harm when reporting organizational wrongdoing and external whistleblowing is more damaging than internal whistleblowing, we claim that

Hypothesis 1a

The more idealistic the employee the less likely he or she is to prefer an external form of whistleblowing

Hypothesis 1b

The more idealistic the employee the more likely he or she is to prefer an internal form of whistleblowing

Dozier and Miceli (1985) describe whistleblowing as an act of highly moral individuals; it is therefore understandable that committed employees are more likely to report wrongdoing in organizations (Vinten 1995). Especially public sector employees are committed to public, community and social service (Brewer and Selden 1998), meaning that they are more “other directed” than private employees. Brewer (2003) finds that public employees score higher on attitudinal items such as social trust. Public sector employees also have more altruistic attitudes than private sector workers (Rainey 1997), are more supportive of democratic values (Blair and Garand 1995), and possess a higher sense of civic duty (Conway 2000).

Public organizations are ‘open systems’ that are easily influenced by external events. Indeed, it is the responsibility of public managers to protect and promote this permeability of organizational boundaries, in order to ensure that services are responsive to public needs (Boyne 2002). It is important for public managers to be able to balance and reconcile conflicting objectives (Boyne 2002). With respect to whistleblowing, this may have an influence on channels chosen for reporting. Internal disclosures provide organizations an opportunity to investigate wrongdoing (Dworkin and Near 1997) and correct it internally, before ‘airing its dirty linen’ in public (Near and Miceli 1985). External whistleblowing may lead to negative publicity, regulatory investigations, and legal liability. As public employees are strongly motivated to serve others and protect the public interest (Brewer and Brewer 2011), we claim that rather than using external reporting mechanisms, they will prefer internal reporting means and thus this effect will be stronger in the public sector, meaning that:

Hypothesis 1c

More idealistic public sector employees are even less likely to prefer an external form of whistleblowing and,

Hypothesis 1d

More idealistic public sector employees are even more likely to prefer an internal form of whistleblowing

Whether reporting results in negative consequences for the whistleblower in a high percentage of cases has recently been questioned. Skivenes and Trygstad (2010) studied whistleblowing among a sample of public officials in Norway, and found a high proportion of them (83 %) reported positive reactions, but whistleblowers who persisted in the reporting process were more likely to suffer retaliation. Brown and Olsen (2008, p. 137) report that only 20–30 percent of whistleblowers reported “bad treatment” in a survey of Australian public sector organizations. Smith (2014) noted that different research methodologies have resulted in different conclusions regarding the extent of suffering that whistleblowers experience—case studies and smaller samples showing higher rates of retaliation, while larger surveys have shown lower rates of retaliation. However, retaliation need not be widespread to indicate to organizational members the risk of engaging in whistleblowing behaviour. According to Graham (1986), the primary personal cost is the risk of reprisal from others in the organization. Ponemon (1994) notes retaliations or sanctions imposed by management or coworkers against the whistleblower may be the most significant determinant influencing the prospective whistle-blower’s decision to report organizational wrongdoing. Previous research (Dozier and Miceli 1985; Miceli and Near 1992) also has found that cost perceptions are associated with reporting intentions. Similarly, Kaplan and Whitecotton (2001) report that there is a negative relationship between the individual’s assessment of the perceived costs of reporting and reporting intentions.

Because of the risks involved in whistleblowing, employees who blow the whistle place themselves at risk to further the public interest. This may be why some whistleblowers choose to report anonymously. Individuals with an idealistic orientation may perceive this risk as less important, as they are strongly related to corporate values (Karande et al. 2002). Highly idealistic individuals judge ethically ambiguous actions more harshly (Barnett et al. 1994; Forsyth 1980) and may therefore be expected to care more than relativists about whether organizational wrongdoing is corrected. As whistleblowing reports by anonymous informants are generally perceived as less accurate than reports by identified whistleblowers (Price 1998), more idealistic individuals may be less interested in disguising their identity and choose to openly show their identity.

Hypothesis 1e

The more idealistic the employee the less likely he or she is to prefer an anonymous form of whistleblowing

Several studies show that in the public sector, whistleblowing can have negative consequences. Glazer and Glazer (1989) found that 89 percent of whistleblowers had difficulty finding employment in the public sector. Still, whistleblowers do so in spite of possible negative consequences. Essentially, these people expose many types of wrongdoing although they are aware of the potential negative outcomes of this act, which can include loss of job (Bucka and Kleiner 2001).

Individual ethical values play a crucial role in the whistleblowing decision-making process. Values are especially important in the public sector, and quite often public employees are confronted with loyalty conflicts when making this decision. Studying these conflicts in public sector employees is therefore closely tied to the (mostly normative) public administration literature on values, moral conflicts, and ethical dilemmas (e.g., Bowman and Williams 1997). Government statute requires public employees to put loyalty to the highest principles above loyalty to persons or party (Johnson 2003). This is also due to public sector employees having multiple goals imposed upon them by the numerous stakeholders that they must attempt to satisfy (Boyne 2002). In an incident of observing organizational wrongdoing, public sector employees may be especially inclined to blow the whistle, because in the public sector, employees are exhorted by law to exercise integrity in the workplace (Johnson and Chope 2005). As anonymous information providers may lack credibility (Ayers and Kaplan 2005), more idealistic employees may spend greater efforts to bring the wrongdoing they observe to daylight without trying to hide their identity. Moreover, especially in the public sector, where values are even more pronounced than in the private sector, idealists may want to be taken seriously and the wrongdoing to be corrected as soon as possible. This expectation is also based on the findings of a study involving employees at three public sector institutions in the Netherlands, in which de Graaf (2010) found that anonymous reporting was rare.

Hypothesis 1f

More idealistic public sector employees are even less likely to prefer an anonymous form of whistleblowing.

Ethical Position and Preferred Channels in the Private Sector

In comparison to public sector institutions which are administered by the government, private organizations are embedded in an environment controlled by market forces and profit orientation (Farnham and Horton 1996). Additionally, private business is characterized by competition between companies absent in the public sector which is based on collaboration of service institutions (Nutt and Backoff 1993). From the private sector’s perspective the staff plays a role as human capital to realize business processes in return for financial rewards (Konzelmann et al. 2006).

According to the sorting hypothesis, individuals choose their workplace on a basis of correspondence between personal dispositions and organizational attributes (Schneider 1987; Bretz et al. 1994). Thus, an individual’s decision to work in the private sector suggests that they are equipped with a different mindset than their public sector counterparts. For example, research provides evidence that in private organizations the levels of flexibility and risk affinity are higher (Bozeman and Kingsley 1998; Farnham and Horton 1996) and business executives’ care for their fellow employees is less (Posner and Schmidt 1982). Furthermore, numerous studies verify private employees’ propensity for extrinsic motivation, namely personal economic prosperity, monetary rewards and prestige (Cacioppe and Mock 1984; Crewson 1997; Jurkiewicz et al. 1998; Karl and Sutton 1998; Khojasteh 1993; Newstrom et al. 1976; Rainey 1982; Wittmer 1991). These findings are in contrast to the predominantly intrinsic motivational factors in the public sector which are characterized by idealistic values such as orientation towards the society, altruistic behaviour and intellectual stimulation (Guyot 1962; Lyons et al. 2006; Taylor 2010).

As a consequence of private sector employees’ materialistic orientation and competitive working environment, we assume that they may be less concerned about ethical practices in their current company or causing harm to others (Forsyth 1992). We therefore hypothesize that,

Hypothesis 2

In general, private sector employees are more relativistic than employees in the public sector.

Although the widespread definition of whistleblowing suggests its dichotomous nature regarding internal and external recipients, some researchers argue for a general external facet of this phenomenon due to the attention and consequences whistleblowing provokes (Chiasson et al. 1995; Johnson 2003). However, while internal acts of disclosure might be approached discretely within the organization, external whistleblowing creates negative publicity for the entire organization including its staff (Barnett 1992; Bather and Kelly 2006; Miceli et al. 2009). In consequence of the damage caused, even the whistleblowers themselves may sometimes possibly become victims of retaliation (Firtko and Jackson 2005). On the other hand, Firtko and Jackson (2005) argue in favour of the media’s legitimation to provide the public with information about abusive actions.

Idealistic individuals attach more importance to internal whistleblowing regarding its greater moral perception and employees’ reservation towards breach of organizational obligations (Zhang et al. 2009). From the idealistic perspective, positive outcomes can always be achieved regardless of the type or severity of the ethical dilemma. According to Karande et al. (2002) a relativistic attitude is related to less corporate ethical behaviour, thus, relativists may be more likely to deprive their employer of their loyalty and cause harm by referring to external recipients. Especially decision-making processes in relativistic settings—i.e. supervisors’ behaviour of trying to satisfy specific stakeholder groups while ignoring others—may encourage underprivileged employees to share their disappointment with external contacts (Barnett 1992). Due to these findings we assume that

Hypothesis 2a

The more relativistic the employee, the more likely he or she is to prefer an external form of whistleblowing.

Hypothesis 2b

The more relativistic the employee, the less likely he or she is to prefer an internal form of whistleblowing.

Whereas idealists hold on to determined superior goals, relativists balance positive against negative consequences dependent on their individual interpretation of situations and circumstances (Forsyth 1992). This point may lead to the presumption that employees with higher relativistic orientation are more likely to switch their workplace in the case of another potential employer offering better working conditions. Particularly, increased competition for highly educated human resources may encourage such a behaviour. Indeed, extensive research demonstrates the effect of lower organizational commitment on increased turnover intentions (Calisir et al. 2011; Meyer et al. 2002; Ng and Sorensen 2008; Paille et al. 2011; Rutherford et al. 2011; Smith 2005). Especially private sector employees show weaker commitment to their organization than their public counterparts (Markovitz et al. 2010) and thus, have higher turnover intentions (Wang et al. 2012). Other than the factor of lower commitment, private sector employees have to face a development towards ‘a more flexible use of labour (e.g. part-time or temporary jobs)’ which may increase their job insecurity (Staufenbiel and König 2010; Burchell 2002). According to Staufenbiel and König (2010, p. 102) ‘one way to emotionally cope with such a stressor is to behaviourally withdraw from the situation’, namely turnover. Current trends reveal an average fluctuation rate of approx. 25 % worldwide; altogether in 2018 about 198 million employees are expected to leave their company (HayGroup 2013).

These high figures of fluctuation imply a decrease of private sector employees’ tenure with the organization which may in turn be linked to lower loyalty and higher external whistleblowing propensity (Dworkin and Baucus 1998). The reason behind this relationship is to be affiliated to newcomers’ lack of knowledge about internal reporting channels, a lower level of organizational identification and the subjective perception of powerlessness (Callahan and Dworkin 1994; Dworkin and Baucus 1998; Miceli and Near 1992).

Due to lower loyalty levels to the current organization in the private sector, we claim that the effect of relativism on whistleblowing is stronger in the private sector, meaning that:

Hypothesis 2c

More relativistic private sector employees are even more likely to prefer an external form of whistleblowing.

Hypothesis 2d

More relativistic private sector employees are even less likely to prefer an internal form of whistleblowing

Studies show that whistleblowing is frequently met with retaliation, which can take many forms, ranging from attempted coercion of the whistleblower to withdraw accusations of wrongdoing to the outright exclusion of the whistleblower from the organization (e.g., Parmerlee et al. 1982). Other retaliatory acts may include organizational steps taken to undermine the complaint process, isolation of the whistleblower, character defamation, imposition of hardship or disgrace upon the whistleblower, exclusion from meetings, elimination of prerequisites, and other forms of discrimination or harassment (e.g., Parmerlee et al. 1982). Retaliatory acts may be motivated by the organization’s desire to silence the whistleblower completely, prevent a full public knowledge of the complaint, discredit the whistleblower, and/or discourage other potential whistleblowers from taking action (Miceli and Near 1984; Parmerlee et al. 1982).

Whistleblowers are damaged persons when success comes, if it comes at all. They experience long-term adverse effects on their economic standing and on workplace and broader social relationships (Jubb 1999). Many therefore choose to disguise their identity when reporting organizational wrongdoing. Kaplan and Schultz (2007) state that different triggers of non-anonymous versus anonymous whistleblowing behaviours are not well understood. However, literature reveals a link between anonymous disclosure and perceived personal costs connected with the act of reporting wrongdoing (Ayers and Kaplan 2005; Kaplan and Schultz 2007; Kaplan et al. 2008; Ponemon 1994). Thus, if the whistleblower anticipates a high risk of retaliation due to his or her exposure he/she is more likely to keep his/her identity a secret.

According to Nayir and Herzig (2012), employees with higher career orientation and concern about their personal interests are most likely to protect these. Thus, as relativists especially balance personal consequences (or in this context—costs -) and prefer the ‘lesser of two evils’ (Forsyth 1992) they are likely to try to avoid any possible retaliation by reporting anonymously. Therefore we hypothesize that

Hypothesis 2e

The more relativistic the employees, the more likely he/she is to prefer an anonymous form of whistleblowing.

Particularly disclosure of organizational wrongdoings towards external parties causes unwelcome media attention, considerable damage concerning the organization’s image (Bather and Kelly 2006) and raises accusations concerning the supervisor’s competence to appropriately control the staff (Parmerlee et al. 1982). As a result, the management punishes the employee’s so-viewed disloyalty by retaliation and dismissal (Dworkin and Baucus 1998). There is evidence that potential whistleblowers are aware of such consequences (Johnson and Chope 2005) which discourages them to make their identity public.

Research has consistently found that private sector employees and managers value economic rewards more highly than do public sector employees and managers (Cacioppe and Mock 1984; Crewson 1997; Karl and Sutton 1998). Direct economic benefits are less important for public sector employees than for those in the private sector (Newstrom et al. 1976). Pay for example is a much greater motivator for private sector employees, supervisors (Jurkiewicz et al. 1998), and managers (Khojasteh 1993) than it is for their public sector counterparts. We may therefore expect private sector employees to be more careful when comparing the possible gains and losses of a whistleblowing decision. Also due to the legal framework they operate in, private sector employees are at risk of being made redundant for any reason (Hames 1988). According to Elliston (1982a, p. 172) ‘the unwillingness to risk his/her career, his/her personal livelihood and the means whereby he/she supports his/her family are perfectly understandable reasons for remaining silent.’ He adds the argument that imbalance concerning the power relations between whistleblower and the subject of accusation restrains the whistleblower from non-anonymous reporting.

On account of relativists’ orientation to reduce personal costs, combined with the harsh response of private sector organizations to whistleblowing acts, we expect this effect to be stronger in the private sector, thus

Hypothesis 2f

More relativistic private sector employees are even more likely they are to prefer an anonymous form of whistleblowing.

Method

Sample and Demographics

The private sector sample data was collected from Turkish managers working at various levels in private businesses in summer 2009. A total of 600 questionnaires were distributed and 327 were returned for a 54.5 % response rate. This group showed an average age of 35.1 years, was 64.2 % male, with a mean education level of 3.7, a mean management level of 2.4, and a mean tenure in present job of 6.8 years.

The public sector data was collected from Turkish officials at various levels in different public institutions in the first quarter of 2010. Again a total of 600 questionnaires were distributed, and 405 were returned for a response rate of 67.5 %. This group showed an average age of 39.4 years, was 79.5 % male, with a mean education level of 3.7, a mean management level of 2.2 and a mean tenure in present job of 12.5 years. Table 1 shows the results of ANOVA analysis comparing the two samples on the study variables as well as the demographics. The public sector sample showed significantly higher values among respondents for age and job tenure while the private sector showed significantly higher values of females and the managerial level of respondents. There was no significant difference in the education levels of respondents between the two sectors. Among these control variables, high intercorrelations existed between ages, job tenures and management levels.

For both samples, the questionnaires were personally distributed to the respondents (by a research group of 20 members). Instructions were given and respondents were assured of data anonymity and confidentiality. The questionnaire was self-administered by the managers and collected after a few days.

Measures

All of the scales used to measure the constructs of interest were taken from previously validated sources. Ethical values of Idealism and Relativism were measured using the ethics position questionnairre (EPQ) from Forsyth 1980, and Oumlil and Joseph 2009. For Idealism, we found a Cronbach’s alpha of .81 and for Relativism an alpha of .75. These reliabilities are consistent with Oumlil and Balloun (2009), who found Cronbach alpha values of .83 and .76, respectively.

Whistleblowing. All three whistleblowing variables were measured by respondents indicating their level of agreement (on a scale of 1 = completely disagree to 5 = completely agree), with statements of how they would report wrongdoing. Thus, higher scores indicate respondents willingness to blow the whistle in that manner. Although measuring whistleblowing in this manner has its drawbacks (see Bjorkelo and Bye 2014; Mesmer-Magnus and Viswesvaran 2005), the practical constraints of obtaining data about actual whistleblowing have led to many studies taking this approach, although it has some advantages as well (Bjorkelo and Bye 2014).

Internal whistleblowing. This was measured with a three-item scale, finding a Cronbach’s alpha of .70. A sample item is “I would report the wrongdoing to the appropriate persons within the workplace.” Previous studies found reliabilities of .78 and .72 respectively (Park et al. 2005, 2008).

External. This was measured with a three-item scale also used previously by Park et al. (2005, 2008). A sample item is: “I would report the wrongdoing to the appropriate authorities outside of the workplace”. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .82, comparable to the measure’s reliability of .85 in Park et al. (2005), and superior to the alphas of .72 in Nayir and Herzig (2012), and alpha of .61 in Park et al. (2008).

Anonymous Whistleblowing. This was measured with a two-item scale developed by Park et al. (2008). A sample item is: “I would report the wrongdoing but wouldn’t give any information about myself.” The Cronbach’s alpha was .65. This reliability compares favourably with Park et al. (2008), which found an alpha of .64, and is slightly better than the alpha of .57 found by Nayir and Herzig (2012).

Sector. Determined by the type of organization where surveys were administered (0 = private, 1 = public).

Demographics. Gender was coded as (male = 0; female = 1). Management levels were measured using a four point scale, (1 = lower level, to 4 = top level). For other demographic variables, actual values were entered on the surveys by the respondent using fill-in-the-blank questions.

Results

In this study, we were interested in the effect of ethical orientation on the intention to blow the whistle, and whether public and private sector settings influence these whistleblowing intentions. We believed that idealism would be positively associated with internal whistleblowing and be more prevalent among employees in the public sector, while relativism would be positively associated with external and anonymous whistleblowing and be more prevalent among employees in the private sector. We also believed that the sector would magnify these relationships. For the most part those beliefs were upheld by the results described below. Table 2 contains correlations and descriptive statistics for the variables used in the multiple regression analyses with coefficient alphas along the diagonal.

Mean scores on the whistleblowing intention variables showed a preference for internal whistleblowing in the total sample (mean = 3.5, sd = .88), followed by anonymous whistleblowing (mean = 2.4, sd = 1.1) and then external whistleblowing (mean = 2.2, sd = .98). These means rank in the same way as the Turkish sample from Park et al. (2008), which found an internal whistleblowing mean of 3.7, anonymous whistleblowing mean of 2.98, and an external whistleblowing mean of 2.85. Public employees overall were less likely to blow the whistle using any type of whistleblowing, as significantly negative beta values were found in multiple regressions on dependent variables of external (b = −.24, p < .001), internal (b = −.34, p < .001) and anonymous (b = −.27, p < .01) whistleblowing intentions. Public sector employees showed a significantly higher mean on the idealism scale than private sector employees (F < .001) supporting Hypothesis 1. Private sector employees, consistent with Hypothesis 2, returned a significantly lower mean on relativism than public sector employees (F < .01). These results support our hypotheses that employees in the two sectors differ in ethical position and whistleblowing intentions, from a univariate perspective. We now turn to our multivariate analyses.

Main Effects

Hypothesis 1 proposed that public sector employees would be higher in idealism than private sector employees. We found a significantly higher mean for public sector employees on idealism (m = 3.95), compared to private sector employees (m = 3.63, F = 53, p < .001), confirming our hypothesis. We also found support for hypothesis 1a that idealistic employees would be less likely to blow the whistle externally—finding a significantly negative beta value (b = −0.23, p < .001) for idealism in a multiple regression on external whistleblowing. A second multiple regression on internal whistleblowing found a significantly positive beta (b = .29, p < .001) for the idealism variable, confirming Hypothesis 1b that more idealistic employees would prefer to blow the whistle internally. Hypothesis 1e proposed a negative effect of idealism on anonymous whistleblowing, and this was also confirmed using MLR, with a significantly negative beta value (b = −.41, p < .001) for idealism on anonymous whistleblowing. (see Tables 3, 4, 5 for regression results).

In our second set of hypotheses which addressed relativism, we found support for Hypothesis 2 which proposed that private sector employees would be more relativistic than public sector employees. We found a significantly higher mean for private sector employees on relativism (m = 3.30), compared to public sector employees (m = 3.16, F = 7.8, p < .01), confirming our hypothesis.

Our beliefs about relativism and whistleblowing were also supported by our analysis. We proposed that more relativistic employees would prefer external (Hypothesis 2a) and anonymous (Hypothesis 2e) whistleblowing, while being less likely to blow the whistle internally (Hypothesis 2b). In the MLR analysis on external whistleblowing, we found a significant positive relationship (b = .23, p < .001) with relativism, and similar results with anonymous whistleblowing (b = .25, p < .001). However Hypothesis 2b was not supported as the beta value for relativism was not significant (b = .05, ns) in the regression on internal whistleblowing.

Interaction Effects

Turning to the joint effects of sector and idealism on whistleblowing, we proposed that the relationship between idealism and whistleblowing would be magnified by the sector of the organization. In Hypothesis 1c, we expected idealistic public sector employees would be even more unlikely to prefer external channels for whistleblowing. This was not supported, as the interaction term was slightly significant in the positive direction for more idealistic public employees (b = .21, p < .10). Hypothesis 1d found no relationship between the idealism–public interaction term and the internal whistleblowing, while in Hypothesis 1f, a strong positive relationship was found with anonymous whistleblowing and the idealism—public interaction (b = .50, p < .001), disconfirming our hypothesis. Thus we found no increase in the relationship with any type of whistleblowing for idealists in the public sector compared to the private sector.

Our hypotheses dealing with the joint effects of sector and relativism were supported for two of three types of whistleblowing. We found support for Hypothesis 2c in the moderation of sector on relativism in the external whistleblowing regression (b = .25, p < .05). We also found as proposed in Hypothesis 2d more relativistic private sector employees to be less likely to prefer internal whistleblowing (b = − .27, p < .01). No moderation was found between private sector relativism and anonymous whistleblowing.

Gender Effect

Even though not proposed as a hypothesis, we did find a significant effect of gender in the regression equations. A main effect of gender was found to be slightly significant when entered as a control variable in model 1 on external whistleblowing, but decreased in significance when other variables were entered. We also found a significant interaction effect of females–public sector for internal whistleblowing (b = − .49, p < .001), indicating that females in the public sector were significantly less likely to prefer internal whistleblowing channels than private sector females.

Discussion

In this article, we studied the relationship between ethical value orientations, whistleblowing intentions and channel choices of Turkish employees in private and public sector organizations. Rather than actual whistleblowing, we focused on the probability of choosing whistleblowing under certain circumstances (Zhang et al. 2009), as according to the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen 1991), whistleblowing intention was found to be a good predictor of actual behaviour (Chiu 2003). It was our objective to compare these two sectors with respect to ethical behaviour, as most comparative studies have been conducted in the fields of organizational behaviour, work and organizational psychology (Markovitz et al. 2010) and there have been calls to further study research questions on similarities and differences between organizations in the two sectors in other disciplines (Rainey and Bozeman 2000). As Rainey (2009) correctly notes, the mainstream research literature simply assumes that public–private differences are absent or trivial. It was our expectation that ethical value orientations and whistleblowing channel choices would be different in these two sectors because employees in the two sectors are motivated by different factors. We chose Turkey as the research context to broaden the research knowledge of cross-cultural ethical issues in management to locations other than multinational corporations and developed countries, where many of these studies have been conducted. We argued that people with different cultural upbringings and living under different socioeconomic influences may not share necessarily the same views of what is ethical or unethical. With our study setting, we also wanted to respond to Bardhan (1997) who argued that although in many emerging economies such as Turkey corruption was a huge problem, especially in the public sector, studies on whistleblowing were rare.

In our first hypothesis, we argued that public sector employees would in general be more idealistic than those in the private sector, as public employees are known to be motivated by meaningful work (Crewson 1997; Rainey 1982; Wittmer 1991) rather than by extrinsic factors such as higher pay (Jurkiewicz et al. 1998; Rainey 1982; Wittmer 1991). Further, we argued that employees in the public sector are guided by values that support a public interest or the common good (Preston et al. 2002). This hypothesis was confirmed. Also our second set of hypotheses claiming that more idealistic individuals would be less inclined to whistleblow through external channels and prefer internal channels was confirmed. Scholars in moral philosophy have generally presented a “strong moral case” supporting internal reports (Zhang et al. 2009). Idealistic individuals are known to believe that positive outcomes can always be achieved regardless of the type or severity of the ethical dilemma. Whereas internal whistleblowing may give organizations a chance to fix problems before they develop into full blown scandals (Barnett 1992; Miceli et al. 2009), externally reporting organizational deviant behaviour may lead to public embarrassment for the organization and mean a failure of everyone concerned (Bather and Kelly 2006). Therefore more idealistic individuals refrain from going to outside channels and attempt to fix problems internally first.

We expected more idealistic individuals in the public sector to be more concerned about avoiding harm to others and hypothesized that they would be even less likely to prefer an external form of whistleblowing and more likely to prefer internal reporting mechanisms. Public sector ethics involves pursuing wider moral principles in the public interest, such as justice, fairness, individual rights, and pursuit of the common good (Niland and Satkunandan 1999). As more committed individuals are more likely to report wrongdoing in organizations, we expected public sector employees with a high sense of community service to be less likely to damage the reputation of the organization by whistleblowing externally. Contrary to our expectations, a higher level of idealism among public sector employees did not have an impact on preference for external or internal reporting channels. We explain this finding with the fact that irrespective of whether the employee is idealistic or not, public managers are expected to protect their organization so that it can respond to public needs (Boyne 2002). In the special case of our research context Turkey, this finding may also have been due to legislation in the Turkish public sector. With paragraph 15 of law number 657 of July 23, 1965 (Official Gazette 12056), it is prohibited for public employees in Turkey to make official announcements through external channels such as press, news agencies or mass media channels. If such an announcement is to be made, it is permitted only through officials such as mayors. Paragraph 31 of the same law states that such an announcement is prohibited (unless written consent has been granted by the respective minister himself) even if the public servant is not in office anymore. According to paragraph 125, the individual may be reprobated and various other sanctions may be applied. Most probably, also these regulations played a role in this finding. In the recommendations for future research section of this article, we elaborate on this topic further. We thought that in combination with an idealistic value orientation this sense of responsibility would be even stronger, and public managers would refrain from telling the press or other external stakeholders about the deviance in their organization. As internal disclosures may give organizations the opportunity to repair the damage caused by misconduct, we believed that public managers would choose this way rather than going to external parties to complain about wrong organizational acts. Although our findings did not support our hypotheses, they are in line with those of de Graaf (2010), whose study showed that although public sector employees said they first and foremost considered themselves loyal to their ministers, they worked for the government because they want to serve society.

In our two hypotheses about preference for anonymous whistleblowing, we claimed that more idealistic employees would be less likely to prefer an anonymous form of whistleblowing and that public sector employees would be even less inclined to whistleblow anonymously. As reporting has negative consequences for the whistleblower and may lead to reprisal from others in the organization or sanctions imposed by management, we expected individuals to have a general preference for blowing the whistle anonymously. We claimed that individuals who judge questionable actions with less tolerance because they are more idealistic would be less inclined to use anonymous reporting mechanisms and rather correct the wrongdoing in an identified manner, as anonymous whistleblowers are generally perceived as less credible (Price 1998; Ayers and Kaplan 2005). This hypotheses was confirmed. However, our expectation about more idealistic whistleblowers in the public sector being even less likely to hide their identity, was not supported. As idealistic values are important in the public sector and employees are expected to show integrity at work (Johnson and Chope 2005), we expected employees in this sector to be particularly inclined to blow the whistle in an identified manner, as they would want the wrongdoing to be corrected as soon as possible. This expectation is also based on the findings of de Graaf (2010) in the public sector, who found that anonymous reporting was rare. However, the findings show that public sector employees in general, whether they are idealistic or not refrain from whistleblowing in an identified manner, first and foremost because it would be legally sanctioned.

Our hypotheses that private sector employees would be more relativistic than employees in the public sector was confirmed as well. Farnham and Horton (1996, p. 31) argue that private firms must pursue the single goal of profit: ‘it is success—or failure—in the market which is ultimately the measure of effective private business management, nothing else’. Further, in the private sectore it is more likely that employee contracts are terminated at any time for any or no reason (Hames 1988). Employees may be dismissed relatively easily due to poor individual performance or insubordinatiıon (McElroy et al. 2001). Consequently, private sector employees may not be as committed to their organization as public sector employees (Markovitz et al. 2010). Already the decision of an individual to work in the private sector may suggest a different mindset than their public sector counterparts. For example, direct economic benefits are less important for public sector employees than for those in the private sector (Newstrom et al. 1976). Pay is a much greater motivator for private sector employees, supervisors (Jurkiewicz et al. 1998), and managers (Khojasteh 1993) than it is for their public sector counterparts. We also found support for our hypotheses that more relativistic employees were more inclined to report externally, than idealistic ones. We considered employees with a relativistic value orientation to be less ethically concerned about their employer’s reputation and see less harm in referring to external reporting channels. This was also an expectation based on the findings of Karande et al. (2002) who stated that relativism is negatively related to corporate ethics. Whereas more relativistic employees are more likely to prefer external whistleblowing, they are not less likely to use internal channels. Relativistic employees choose internal mechanisms when they are available and depending on the situation.

Our hypothesis that relativistic private sector employees would be even more likely to prefer an external form of whistleblowing than public sector employees was supported. It has been established that external reporting puts the organization under public scrutiny and hurts innocent organizational staff (Firtko and Jackson 2005), thus we hypothesized that relativistic individuals would not be too concerned of such consequences and use the external reporting channel deliberately. In combination with their relatively low organizational commitment, private sector employees with a relativistic value orientation, see no harm in making the wrongdoing public. As there is no particular need for them to correct the issue internally, they do not spend additional effort to keep the problem within organizational boundaries. For them, causing public disgrace is not a particularly hurting issue.

With respect to anonymous whistleblowing, we found that more relativistic employees were more likely to prefer an anonymous form of whistleblowing. According to Nayir and Herzig (2012), employees with higher career orientation and concern about their personal interests are most likely to protect their interests. Relative to a non-anonymous reporting channel, an anonymous reporting channel is expected to increase individuals’ willingness to report fraudulent financial reporting by decreasing expected personal costs of reporting, including potential retaliation, and other negative consequences (Ayers and Kaplan 2005; Bjorkelo 2013; Kaplan and Schultz 2007; Ponemon 1994). In the case of the private sector, we expected preference for anonymous whistleblowing to be even higher, as private organizations are usually not tolerant towards non-conformity to organizational ideologies (Shahinpoor and Matt 2007) and questioning is perceived as an act of disloyalty (Dorasamy and Pillay 2011). Evidence suggests that many employees already know that dire consequences will follow whistleblowing (Johnson and Chope 2005) including a major, often deleterious, impact on their careers. According to Fisher and Lovell (2003), the effect on careers was a significant factor shaping the muteness of many managers in ethical organizational matters. Therefore we expected private sector employees to be aware of the punishment that may expect them if their disloyalty becomes public, and so they would try to balance personal consequences by hiding their identity when reporting organizational wrongdoing. However, this last hypotheses was not confirmed. As whistleblowing can become very harmful for individuals, they refrain from declaring their identity whether they are in the private or the public sector. In the public sector people disguise their names because it is legally prohibited and in the private sector act similarly because of personal career consequences; i.e. sector does not moderate the propensity to whistleblow anonymously.

With our study, we contribute to the literature of whistleblowing and the influence of ethical characteristics of individuals on the decision to use particular modes of whistleblowing, by comparing private and public sector employees. We extend whistleblowing scholarship by adding moral value orientations to traditional whistleblowing studies, which rely on “cold” economic calculations and cost-benefit analyses to explain the judgments and actions of potential whistleblowers (Henik 2008). Although, we do not enquire actual whistleblowing behaviour, but channels in case the individual decides to whistleblow, we are nevertheless of the opinion that we address an important question as studies suggest close relationships between attitudes and actual behaviour. The theory of reasoned action for example suggests that individuals’ judgments and values influence their behavioural intentions and subsequent actual behaviour (Ajzen and Fishbein 1980). Researchers have also shown that perceptions of intention and judgments of responsibility predict responses to acts of wrongdoing (Martinko and Zellars 1998; Weiner 1995). The responses about self-reported intentions to use certain modes in case of whistleblowing may therefore be a good indicator of actual whistleblowing behaviour. In choosing Turkey as context, we build upon a previous study by Park et al. (2008).

Our study contributes valuable insights into the nature of whistleblowing and its relationships with value orientations of individuals in private and public sectors. From a theoretical perspective, our study demonstrates that ethical differences have an influence on the decision whether to and how to whistleblow. Secondly, this study demonstrates a direct relationship between the sector context in which whistleblowing takes place and channels preferred, which advances previous empirical research. In our chosen context of Turkey, where whistleblowing is seen as a negative act, external whistleblowing appears to be anonymous, i.e. one integrated mode of whistleblowing. This may be considered in the design of future studies investigating whistleblowing in Turkey or similar countries outside the US and Europe, i.e. those regions which have not been the focal point of research in the past (Miceli et al. 2009). The results of this study may additionally provide a literature in comparing whistleblowing behaviour between western and non-western countries. Lastly, this study suggests a new avenue to whistle-blowing research by incorporating ethical value orientation as a variable influencing whistleblowing intention. Fourth and in relation to this, our findings may stimulate other researchers to investigate possible relationships between internal and identified (i.e. non-anonymous) whistleblowing in future studies in Turkey as this study was limited to external and anonymous whistleblowing

The study has also managerial implications. Whistleblowing on organizational wrongdoing has the potential for many positive outcomes for the organization (Miceli and Near 1984; Near and Miceli 1996. Lewis (1991, p. 170) argues that ‘such a practice is a potential part of a system to maintain and improve organizational quality’. Today, whistleblowing should be recognized as an instrument for proposing organizational changes, rather than as an attack threatening the identity of the organization (Miceli et al. 2009). At an organizational level, to discourage employees to externally share observations about organizational wrongdoings, managers of Turkish private sector firms may work on improving the effectiveness of internal channels by taking decisive steps towards achieving international standards in governance practices. Codes of conduct and similar guidelines are equally important in the public sector. A number of developed countries have established legislation to protect people who reveal wrongdoing. Also, Turkey has made some progress in establishing these corporate governance principles in its private sector. Tougher penalties for organizations and more leniency options for individuals are being introduced, encouraging not only whistleblowing but also self-disclosure. In particular, efforts of the Capital Market Board on the establishment and application of corporate governance principles have been greatly appreciated by market players, as well as financiers and legal practitioners (Ozeke 2010). Adapting legislation may however not be enough to discourage external reporting. Also adjusting the ethical climate of the organization may be necessary to discourage employees to engage in external whistleblowing. If this can be achieved, instead of being afraid of potential whistleblowers, a culture that generates whistleblowers can be actively cultivated so that information is known and can be utilized before mistakes arise (Evans 2008). However, blindly developing ethics codes without adequate integration of personal moral philosophies would not improve the ethical climate of organizations. As Henle et al. (2005) observe, managers’ moral philosophies may make them less or more willing to adhere to organizational policies, which means that managers are likely to respond to ethically challenging situations in disparate and idiosyncratic ways. Not only should managers be made aware of corporate ethical values through ethics codes, but also recognizing managers’ and employees’ ethical ideologies when formulating ethics codes could avoid misinterpretation and misapplication of organizational values and intentions.

The mechanisms by which whistleblowing is encouraged may differ between public and private sectors, as employees in these two domains are motivated in different ways. According to Hvidman and Andersen (2014), performance management techniques constitute effective means of improving performance in the private sector, whereas in public organizations, performance management does not improve performance. As relativistic employees in the private sector are motivated by extrinsic rewards, financial incentives may be an effective means to encourage whistleblowers (Callahan and Dworkin 1992). Through a combination of an ethical climate with rewards geared towards the motivations of the private sector, reporting wrongdoing via internal mechanisms may become institutionalized as part of an open organizational culture and become an effective control device. In the public sector, through continuing education and training, the conduct of public administrators at all levels and an adequately resourced and mandated coordinating office may be important ways to monitor and advise on ethics across government. During this process, public sector organizations would benefit from knowing the personal characteristics of their employees better, paying greater attention to their value orientations and understanding how they address ethical issues in their professional decision-making process. In both sectors, leaders may want to create occasions to talk to their employees about their observations and opinions on how daily life in the organization runs. The annual performance appraisal could be one of these occasions, where employees can freely talk about what they see as main ethical problems in the company or the public office. During these conversations, managers should explain to their employees possible ways to may themselves be heard within the organization, as despite procedures for whistleblowing, employees may need more practical guidance about how to report wrongdoing. Also apart from performance appraisal sessions, managers should establish and support a culture where dialogue and feedback are regular practices, including multiple channels for reporting concerns. Within this culture, the leader himself should be an ethical role model, because if there is no supervisor support, employees may become demotivated to blow the whistle even when the organizational culture values employee dissent with respect to organizational wrongdoing (Dozier and Miceli 1985; Near and Miceli 1985). Additional mechanisms such as limited terms, rotation of office, elections instead of appointments (Hood 1991) and transparent 360° appraisals where all colleagues (and not solely supervisors) provide assessments may further help develop such an organizational culture. Through mechanisms such as these whistleblowing can become a better managed and more effective approach to reporting organizational wrongdoing and fostering responsible behaviour in organizations.

This study has some limitations which should be considered when drawing conclusions from the results. First, the study was conducted in a single country setting. It might therefore be inappropriate to derive general conclusions from the findings of the study. Second, the study is related to the use of self-reported questionnaires. The use of self-reported attitudes means that responses might be subject to social desirability effects. Especially, in a study related to ethical preferences, it might very well have been the case that respondents gave socially acceptable responses. Third, it is also important to recognize the survey’s limitation in giving a general prompt to the respondents as we did not want to limit our study to a specific type of organizational wrongdoing. This allowed respondents to imagine the specific organizational misbehaviour on their own and may have evoked different interpretations and scenarios. As modes of whistleblowing may vary depending on the magnitude of the organizational wrongdoing, future studies could build upon our study and investigate specific types of organizational wrongdoing. Fourth, in one set of hypotheses, we attempted to find a relationship between idealism and particular whistleblowing channels in the public sector. As external whistleblowing is prohibited by law in Turkey, this may have had an effect on the responses given by public sector employees. Fifth, throughout the whole article, we claimed that working in a particular sector rather than the other one, was primarily a matter of choice for the individual, based on his/her own orientation. This may not be the only factor, as employees may make different choices, when they are still employed and look for a new job; and when they are unemployed and have to take more or less what is available. Finally, the use of surveys that collected respondent’s intention to blow the whistle have been shown to produce different results than survey’s that collect data about actual whistleblowing events (Mesmer-Magnus and Viswesvaran 2005). Although this approach is not uncommon in whistleblowing research, it is a consideration when interpreting the results of this study.