Abstract

This research advances our understanding of the manifestation of tensions and ethical issues in entrepreneurial finance. In doing so, we offer an overview of ethics in entrepreneurship and finance, delineating the curious paucity of research at their intersection. Using twelve vignettes, we put forward the asymmetries between entrepreneurs and investors and discuss a set of ethical problems that arise among key actors centring on the dynamics of venture partner entry and exit, applying the multiple-lens ethical perspective to analyse these issues. This analysis culminates in the introduction of a general classification scheme for ethical problems across venture partners. Our analysis highlights the moral dimension inherent in the entry and exit of venture partners and the importance of considering moral judgement, as well as intention in future analysis of any decision-making. Our study also points to the moral responsibility in finance, especially to the mutual moral responsibilities of investors and entrepreneurs. By integrating ethics into finance, this research also demonstrates that in the case of venture partner exit, an ethical approach and decent governance go beyond compliance to the law. We conclude with implications for practitioners, specifically with some proposals for a solution to the problem of blocked and forced exit. Together, we make several contributions to the literature by integrating ethics, finance and entrepreneurship, and we call for future research to stimulate a growing body of research within this presently overlooked area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Across the global business landscape, the finance and banking sectors have been sailing on a tumultuous course. A collective lack of attention to and application of rigorous ethical standards has led to myriad scandals, conflicts and tensions. A number of scholars have taken note and have rightfully called attention to, as well as taken steps towards delineating remedies which instil greater ethical standards. Much of this work, however, focuses on larger corporations and larger banks in incumbent industries. This means that the study of ethics in the entrepreneurial context—particularly venture financing—has been left relatively untouched. As governments, scholars and practitioners call for more accountability for all parties involved, we believe it is crucial to contribute to the largely overlooked study of ethics in entrepreneurial finance. Because of the important economic role of financing entrepreneurial ventures (Sohl 1999) and the unique dilemmas that financing young, uncertain ventures poses, we take a step towards integrating ethics in this context—particularly the conduct of entrepreneurs, angel investors and venture capitalists (VCs) in their relations with one another. As such, the objectives of this paper are fourfold: (1) provide an initial overview of the importance of ethics in entrepreneurial finance, (2) identify a preliminary set of ethical problems that occur among key actors, (3) offer a classification scheme for such problems and (4) call for future research at this intersection while outlining several possible directions.

Moreover, financing in the entrepreneurial setting is particularly distinct because, due to the inherent uncertainties (i.e. lack of track record, profit generation and tangible assets), young, high-growth potential companies generally face difficulties in raising funds from traditional sources such as banks and public capital markets (Berger and Udell 1998; Da Rin et al. 2006). Thus, entrepreneurs regularly turn to sources of equity financing, such as angel investors or VCs, who, in addition to providing capital, often become actively involved in the ventures in which they invest (Harrison and Mason 1999). Venture investors search for high profit potential, often technologically disruptive ventures in which to invest their capital. Angels and VC investors, then, engage in unique, high-risk partnerships with founding entrepreneurs. As in other forms of strategic relations, the goals, interests and values of the involved investors and entrepreneurs are not always aligned—thus, funding relationships among stakeholders are often characterized by tensions, conflict and agency problems (Yitshaki 2008; Drover et al. 2014a, b; Fassin 1993). By way of twelve vignettes, we introduce a series of problems that shed light on such issues. While misconduct can occur throughout the different stages of a start-up’s lifecycle (Fassin 2000), we focus specifically on important critical milestones related to the financing of these entrepreneurial ventures: the entry and exit of new venture partners, where either party enters or withdraws from the financial ownership of the venture concerned. While many exits likely occur in mutual agreement, others are involuntary and may result from conflicts and unethical behaviours among venture partners. These include questionable actions in the investor–entrepreneur and investor–investor (i.e. investment syndicates) dyads that lead to negative, often harmful outcomes.

Distinctively, we begin by offering an overview of ethics in entrepreneurial finance and a brief presentation of different ethical perspectives. We then discuss the dynamics of the venture lifecycle, illustrating some of the antecedents such as tensions, conflicts and asymmetries that arise throughout. Next, we discuss the vignettes from multiple ethical perspectives which offer a preliminary look into a set of ethical problems that occur. These offer the opportunity to classify such problems and to analyse the ethical dimensions of the problems. Following the scholarly and practitioners implications, we call for and suggest future avenues of research.

Collectively, by integrating ethics into finance, we aim to contribute to the literature in a number of ways. By focusing on the dangers and consequences of unethical behaviour of venture partners, we contribute to the call for more research on ethics and entrepreneurship (Drover et al. 2014a, b; Hannafey 2003; Fisscher et al. 2005; Harris et al. 2009). In addition, we address the “darker” sides of their relationships in general and the tensions these occasion. We suggest that the inclusion of this overlooked aspect and the consideration of the moral judgement in decision-making in finance assist in more completely understanding the role of finance and banking in the business landscape and anticipate that this work will serve as an impetus for future research investigating ethical-related relational tensions and possible remedies mitigating such tensions.

Ethics in Entrepreneurial Finance

While focus on entrepreneurship and ethics is generally scarce (Scott et al. 2014), research on entrepreneurial finance has garnered even less attention. The rare books or articles on finance ethics (Boatright 1999, 2000, 2010) hardly mention ethics in entrepreneurial settings, while recent research has pointed to the link between corporate governance and business ethics (Ryan et al. 2010). Within the research that does exist, an important avenue treats the agency relation between entrepreneurs and investors (Jensen and Meckling 1976; Amit et al. 1998; Hellmann 1998; Kaplan and Stromberg 2001; Bonnet and Wirtz 2012). Higashide and Birley (2002) and Yitshaki (2008) investigate the conflicts between venture capitalists and entrepreneurs. Collewaert (2012) studied the angel investors’ and entrepreneurs’ intentions to exit their ventures from a conflict perspective. Interestingly, few scholars have studied opportunisticFootnote 1 behaviour from the entrepreneur’s side (Gorman and Sahlman 1989; Scarlata and Alemany 2010) or from the side of the venture investor (Cable and Shane 1997; Fassin 2000; Fried and Ganor 2006; Hellmann 2006; Smith 1998; De Bettignies and Brander 2007).

Some scholars (e.g. Payne et al. 2009; and De Clercq et al. 2006) have analysed information asymmetries and the imbalance of power. Other researchers have emphasized the role of trust (Argandona 1999; Kickul et al. 2005; De Clercq et al. 2006; Maxwell and Lévesque 2014) or the role of procedural justice and fairness in the relationships between the entrepreneur and his investors (Sapienza and Korsgaard 1996). Collewaert and Fassin (2013) analysed the influence of the ethical attitude on the escalation of conflict and threat of detrimental outcome for the venture. More generally, Levicki et al. (1994) and Bazerman et al. (2000) point to the ethical aspects in every negotiation process. More specifically, though, only a few specific articles treat the ethics in VC (Fassin 1993, 2000; Collewaert and Fassin 2013; Useem 2000). Recently, Drover et al. (2014a) investigated the mitigating effect of entrepreneurs’ evaluations of investors’ ethical reputation on the entrepreneurs’ willingness to partner, while Pollack and Bosse (2014) examined when investors forgive entrepreneurs for lying.

Ethical decision-making, more generally, is affected by issue characteristics, context and personal situation (Barnett 2001). As ethics is about perceptions (Singhapakdi 1999; Carlson and Kacmar 1997; Ambrose and Schminke 1999), ethical judgments can and often do differ (Forsyth 1992; Reidenbach and Robin 1995). Applied to the entrepreneurial context, both the entrepreneur and the investors can form separate views and differing perceptions of what constitutes ethical and unethical behaviours. There exists “a grey area in which the lines of acceptable and unacceptable conduct are not easily drawn” (Boatright 1999, p. 13). As such, certain actions of the investor may be perceived as opportunistic and unethical by the entrepreneur (e.g. firing a longstanding founder or excessive dilution) (Broughman 2010), while investors may believe the same actions to be legal, as in compliance with the contract, and thus not unethical in their mind, but merely part of the game (Collewaert and Fassin 2013). Such perceptions are important considerations as researchers begin to consider the role of ethics in entrepreneurial finance.

Different Ethical Perspectives on Decision-Making

Mele (2012) posits that “ethics in managerial decision-making” involves a descriptive compound, based on behavioural studies and a normative, prescriptive meaning. He further argues that “ethics should be present in a holistic perspective of decision-making” (Mele 2012, p. 46). In this holistic approach, it is therefore proposed to consider duties, consequences and virtues perspectives, rather than only one perspective. Theories of ethics each have different foundations—are all equally correct?Footnote 2 Different theoretical frameworks can shed complementary light from different angles on a single problem. As Crane and Matten (2004, p. 104) argue, “by viewing an ethical problem through the prism of ethical theories, we are provided with a variety of considerations and aspects pertinent to the moral assessment of the matter at hand”. In a pragmatic approach, our ethical analysis will reflect the actions or decisions of different ethical theoretical frameworks, such as utilitarianism, the ethics of rights and duties, and the ethics of justice.

Utilitarianism, a consequentialist theory based on Bentham and Mill’s principles, focuses on the consequences of actions rather than procedure or motivation (Buchholz and Rosenthal 1998). Utilitarianism weighs the benefits of an action against the costs that the action incurs (Ferrell and Fraedrich 1994), the pleasure derived against the pain, or happiness versus unhappiness. “According to utilitarianism, an action is morally right if it results in the greatest amount of good for the greatest number of people affected by the action” (Crane and Matten 2004, p. 84). Utilitarianism reflects ‘the greatest happiness principle’.

The two other perspectives focus on the underlying morality of the action. In this perspective, deontology and principles count. Ethics of duties (following Kant) tends to start by assigning “a duty to act in a certain way” to protect the other party’s right (Crane and Matten 2004, p. 86). The deontological approach to the ethics of rights (developed by John Locke) contends that an action’s intentions (Mele 2012) are more important than its consequences. It states that it is our duty to act towards specific others in the way we would have acted towards the rest of humanity, just as it is our right to expect the same from others (Velasquez 2002). The morality of the motivation defines the morality of the action.

The ethics of justice approach, based on Rawls’s principle of justice (Rawls 1999), aims for a fair distribution of costs and benefits among the parties; it strives for the fair treatment of individuals in a given situation with the result that everybody gets what they deserve (Crane and Matten 2004, p. 92). Distributive justice is described by social scientists as the fairness of outcomes that one receives. It considers whether everyone had an equal opportunity to achieve a just reward for their efforts in proportion to their contribution (Cropanzano and Stein 2009). Procedural justice concerns the fairness of the allocation process through which outcomes are assigned. Individuals are generally willing to accept unfavourable results as long as the process is seen as fair (Cropanzano and Stein 2009). Interactional justice concerns the fairness of the interpersonal treatment one receives from others and, as such, encompasses the dignity and the respect with which decision-makers treat others (Bies and Moag 1986). Fairness principles endorse the ‘Golden Rule’: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you” (Ragatz and Duska 2010, in Boatright, 2010, p. 305). Fairness requires a professional to treat others as he or she should wish to be treated. In the financial markets, this implies the concept of a “level playing field, which requires everyone plays by the same rules but that they be equally equipped to compete” (Boatright 1999, p. 44).

According to Mele’s Triple Font of Morality Theory, “a sound moral judgment considers three elements of morality: (1) intention, (2) action chosen and (3) circumstances, including predictable consequences and situational factors” (Mele 2012, p. 60). Intention refers to the morality of the end or goal for which the decision is taken; the action chosen to the morality of the means for this end; and the morality of relevant consequences and situational factors (Mele 2012, p. 70). In behavioural ethics literature, unethical intention can be defined as “the expression of one’s willingness or commitment to engage in an unethical behavior”. (Kish-Gephart et al. 2010, p. 2; Harrison et al. 2006). According to Rest, intention precedes behaviour (Rest 1986, in Kish-Gephart et al. 2010),

By leveraging different ethical perspectives, we are able to gain a comprehensive overview of considerations and aspects pertinent to the moral assessment of issues at play between entrepreneurs, angel investors and VCs. This ‘spectrum of views’ allows us “to fully comprehend the problems, the issues and dilemmas and its possible solutions and justifications” (Crane and Matten 2004, p. 104)—resulting in a step towards advancing our understanding of the role of ethics in entrepreneurial finance.

The Dynamics of a Venture’s Lifecycle

Beginning to understand ethics as applied to entrepreneurial finance first necessitates an understanding of the unique lifecycle of entrepreneurial ventures. During a venture’s lifecycle, several new actors may appear, not only in terms of investors, but also in terms of actively involved individuals. Starting out with only the founding team members, the new venture team gradually expands by hiring a number of key team members. Then, with successive rounds of financing, experienced and hands-on board members may enter. Not only may new venture partners enter at different times during the entrepreneurial lifecycle, some may also leave (e.g. Ucbasaran et al. 2003). These changing dynamics in new venture teams hold the potential to create tensions, conflicts and asymmetries among venture partners given that each change often entails new rules and agreements following negotiations. Figure 1 illustrates the lifecycle of a venture with subsequent crucial phases of entry of new financiers, which also implies new partners and new board members alongside new rules and new agreements. The figure illustrates a generalizing example, where the cases in the vignettes (discussed below) describe critical moments that coincide with these crucial events in the lifecycle of a venture.

Theoretical Approaches: Conflict Theory and Corporate Governance

The dynamics of entrepreneurial venture capital-backed companies can be been studied from diverse theoretical perspectives. We build on conflict literature and corporate governance research to establish a framework for analysis for our theme.

The conflict literature identifies task-related conflicts and relational conflict (De Dreu & Weingart 2003). Task conflicts are functional and refer to perceived disagreement about what should be done, while socio-emotional relationship conflicts pertain to perceived interpersonal incompatibilities. Higashide and Birley (2002) differentiate divergences between goal objectives and policies. Yitshaki (2008) identifies three dimensions of coordination conflicts between VCs and entrepreneurs: contractual, contextual and procedural. Collewaert (2012) adds specific goal conflicts to relationship and task conflicts.

Corporate governance literature has mainly approached the governance of entrepreneur–investor relations from the perspective of agency theory (Daily et al. 2003). According to agency theory, it is “assumed that investors mainly use governance mechanisms to reduce agency risks, through active monitoring and contractual clauses designed to enhance their control over the venture, to limit their downsize risk, and to incentivize entrepreneurs to create value” (Bonnet and Wirtz 2012, p. 49; Kaplan and Stromberg 2001). However, besides controlling and monitoring, VCs and business angels also play an active role in strategy formulation and add value through networking. This alternative approach to corporate governance borrows on knowledge-based and behavioural theories and complements the classical approach to corporate governance.

Tensions and Conflicts: A Conflict Theory Perspective

The entry of new venture partners has significant impact on the nature and quality of the relationship between the different shareholder categories and the entrepreneur (Bonnet and Wirtz 2012). Prior to venture partner entry, existing and potential new partners will exchange information and familiarize themselves with one another. As such, trust and mutual liking is built (Forbes et al. 2006; Harrison et al. 1997; Maxwell and Lévesque 2014). If the interest is confirmed, further due diligence is conducted by the new investor (Amit et al. 1998; Fiet 1995). Upon actual entry, a number of agreements will be made and recorded in contracts, defining each other’s obligations and rights (e.g. Kelly and Hay 2003; Kaplan and Stromberg 2001; Wright et al. 2009). Investors can use multiple mechanisms, including contracting, board membership and relationship building with management to reduce agency problems (e.g. Fiet 1995; Landström 1993; Van den Berghe and Levrau 2002). These contracts include a number of covenants, conditions (e.g. milestones) and procedures to follow in case of, for instance, the sale of shares to third parties (Cumming 2008; Dessein 2005).

In some cases, such changes around entry and exit of venture partners may immediately result in conflicts about exit (Collewaert 2012). In situations where partners agree—exiting or staying—there is generally no problem. If, upon the entry of a new partner, everyone agrees that incumbent partners should remain, an agreement should be reached regarding the conditions under which this will occur and regarding the role of each party. If all parties are in agreement that a particular partner should exit, all partners must agree on the price and conditions of the deal. Tensions that lead to problems or conflicts, however, can and do occur when the involved partners possess opposing aspirations (e.g. some partners may want to exit, but may be forced to stay, and vice versa).

In addition to conflicts arising upon the entry of new venture partners, conflicts may also arise at a later juncture despite agreements being made upon entry. Conflicts may also derive from the asymmetric contractual agreements that are perceived as unfair by one party—especially when decisions are unilaterally imposed by the majority shareholders (Dessein 2005; Collewaert and Fassin 2013). Such tensions, if not carefully managed, may still result in the premature exit of one or more of the parties involved and at worst in the failure of the venture. Further, promises, explicit or implicit, are often made (Parhankangas and Landstrom 2006). While promises and agreements may be made with the best intentions, problems may nonetheless later arise (Parhankangas and Landstrom 2006). Content-wise, agreements and promises may be made with regard to operations, strategy and governance. Operational agreements involve task descriptions, i.e. what is expected from each partner, while strategic agreements refer to how to transpose the vision into a growth path for the venture. With regard to governance, agreements will be made regarding which control mechanisms to implement that achieve the right balance between shareholders and management (Jensen and Meckling 1976; Van Osnabrugge 2000; Wright et al. 2009). Expectations based on promises made may differ among the various parties involved, leading to discussions at a later juncture. Also, perceptions of how one is treated may vary fundamentally among parties (Collewaert and Fassin 2013).

The instances outlined above simply illustrate the potential of ethics-related issues in the high stakes game of entrepreneurial finance. We next discuss some of the asymmetries that often underpin such problems and then more concretely explore such ethical issues in greater detail utilizing illustrations from vignettes.

Asymmetries Among Venture Partners

Throughout a venture’s lifecycle, entrepreneurs are faced with a number of asymmetries with their stakeholders. Specifically, entrepreneurs and their investors—VCs and BA’s—are confronted with problems of asymmetry: asymmetries of resources, asymmetries of objectives and asymmetries of power.

Asymmetries of Resources

The asymmetry of resources consists of information asymmetry (Boatright, 1999, p. 99), knowledge asymmetry (Bonnet and Wirtz 2012), asymmetry of money and asymmetry of experience. Especially in high technology ventures, the entrepreneur/founder generally possesses greater technical intellectual property and product-related information, while the VC may have a broader view on the market and environment. VCs are often more knowledgeable on legal and financial matters than entrepreneurs, and often also in managerial skills. They typically have an extensive network of contacts (e.g. other investors, entrepreneurship attorneys and accountants, consultants, etc.). VCs have the availability of financial means, which the entrepreneur lacks. The entrepreneur’s experience is generally more limited and specific in the field he or she is operating, while the VCs have broader experience. Besides the capital, VCs have also added value such as marketing skills, implementation of thorough monitoring systems and access to their network; they also bring their reputation. Table 1 offers an overview of the varied aspects of asymmetries in the entrepreneurship–VC relation, where the angel investor’s view can be positioned somewhere in between.

Asymmetries of Objectives

The objectives and strategy also strongly differ between the entrepreneur and his or her investors. Organization theory research indicates that different types of shareholders may have different objectives (Fiss and Zajac 2004). These different types of owners, entrepreneurs, angel and venture investors also have a different time horizon. Risks and objectives are different. VCs spread their risks over several projects, whereas the venture is the entrepreneur’s single project, where he has put most of his energy and resources, including money and time. Angel investors again are positioned in the middle of this continuum, with investment in a selected number of projects (Bonnet and Wirtz 2012).

Entrepreneurs, BAs or VCs have a common objective: to increase the value of the venture. Asymmetries often arise, however, among venture partners. VCs have a limited time perspective and want to exit with a capital gain to return to their limited partners. Entrepreneurs as founders may be more attached to their company and often prefer to stay in control of their company; in fact, some entrepreneurs may like to stay forever with their company. The attitudes of BAs, who invest their own personal capital, can depend on the personality and objective of the BA and their specific situation. Some prefer to be hands-on and prefer to be active in the management of the company; some are more hands-off and passive investors. For many BAs, participating with a venture may be an important driver, and making exponential profits on an exit may yield an added bonus, as opposed to the pure financial objective of the professional VCs. For the entrepreneur, the need for achievement is often the major driver—the realization of his or her dream, so making the project succeed is often equally important as the potential financial gain. As the above depicts, rewards and objectives can vary considerably, contingent upon the partners in the venture; thus, asymmetries of objectives can surface as a source of perceived unethical behaviours and conflicts.

Asymmetries of Power

Asymmetries of information, resources and money create also an asymmetry in power between investors and entrepreneurs (Yitshaki 2012). Investors have to rely on the entrepreneur for correctness of the information concerning the potential advantages of the technology and the advancement of the product development or prototype. When investors commit funds to a venture, they want these funds to be utilized in an efficient way. Experience has unfortunately shown that some less ethical entrepreneurs have concealed important information or disguised or misrepresented the stage of development of their project and that others have not always utilized the funds they received in a proper manner (Pollack and Bosse 2014). This behaviour has led investors to impose strict control measures and governance principles to counterbalance the asymmetry in power (Drover et al. 2014a). This asymmetry in resources and unequal bargaining power lies at the origin of many disagreements between the entrepreneur and his investors. As Mele (2012, p. 154) put it: “Power can foster opportunism.” The asymmetry of resources, objectives and power, then, can lead to different views on different issues and disagreements in vision, as the various cases will illustrate.

Identifying Ethical Problems in Venture Financing: A Vignette Approach

For this exploratory study on ethics and entry/exit in entrepreneurial finance, we selected examples of companies that received financing from angel and/or VC investors. These cases are presented in a short description in the vignettes in Appendix. They were obtained through referrals from entrepreneurs, VCs, business angel networks, and a couple were sourced from the press. We presented the vignettes in short story form as such examples have been used in other studies (e.g. Hornett and Fredericks 2005; Collewaert and Fassin 2013). The vignettes have been reduced to focus on one theme with the danger of losing nuances. Conflict situations are frequently used in business ethics studies to describe unethical standards or practices (Brinkmann and Ims 2004). The vignette style will be used to reveal a preliminary investigation of the facets of a phenomenon specifically to provide an indicative illustration of different ways in which entry or exit can occur in start-ups and in VC- or angel-backed companies as well as of questionable practices leading up to or triggering exit. While this handful of selected cases has no claim of being representative, the cases do provide some initial insight into a number of entry and exit-related ethical problems in entrepreneurial finance. Table 2 briefly schematizes the problems, stage of financing, conflicts and results for the twelve cases.Footnote 3

Overview of Vignettes

The vignette cases cover a wide range in entry and exit scenarios in the entrepreneurial context, at different stages of the venture: investors force an entrepreneur to resign as a CEO and to sell his (the entrepreneur’s) shares at a loss (Case G), to buy back the investors’ shares (Case I); another entrepreneur abandons the venture himself when he sees no other way out (Case E), while there have also been cases in the beginning years of Silicon Valley where an entrepreneur leaves the team after completion of his finance round for another venture for a better remuneration and stock options. Case A presents a pre-entry situation, where the entry promise is broken by the entrepreneur. Case B illustrates a fraud case where the entrepreneurs build on a fake project and embezzle the money they have raised. Investors may also be faced with the dilemma of deciding whether it is the CEO or the inventor who has to quit (case C); the entrepreneur can also agree with investors to step down as a CEO, take on another function in the venture, and keep his shares (H). A variation of the latter can be found in the famous Cisco Case, where the entrepreneurs also agreed to quit as CEO, but wanted to stay on as passive shareholders (De Clercq et al. 2006).

Other cases highlight the potential for investor exits; while a VC generally tends to decide himself upon whether or not to exit (excluding the venture’s financial situation), angel investors are in a somewhat different situation. While these investors may be needed in the start-up phases of a venture, their presence is generally not indispensable as soon as larger financial partners make their entry. Angel investors may then be asked to resign from the board and to become passive investors; they may be required to subscribe to new shares. They may be asked or forced to sell their shares to the new investor (case D) or, quite the contrary, may be blocked from exiting (Case F and H). VCs may also be indifferent and accept that angel investors stay on as shareholders. Additionally, exit through an external acquisition proposal can bring conflicting views among VCs who step in at different times and with a different entry price and consequently may have a different evaluation of the proposal (case J). Finally, we present a case where the entrepreneur sold his company to a foreign group shortly after having bought back his financial partners (case K). A variation of this case is the case L, where in a post-IPO situation, the entrepreneur delisted the company just before selling it to an industrial group.

Ethical Problems and Classifications

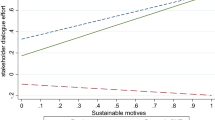

Building on the various streams of literature, we propose a framework to further analyse the ethical dimensions in the venture entry and exit issue. Here, we introduce a categorization of problem areas that entrepreneurs and investors may encounter in their partnership. Expanding upon our discussion of the venture’s lifecycle and the tensions and conflicts that often result among venture partners who enter and exit, we draw on our set of vignettes to identify several ethical problems that arise. Table 3 shows an overview of these unethical issues in the cases. We classify such problems under operational, strategic, governance, relations and ownership/valuation problems. This classification and the problems arising across venture partners are illustrated in Fig. 2 below. The second column in Table 4 shows the major areas of problem of the twelve cases.

Operational Problems

On the operational side, entrepreneurs are generally expected to take the driver’s seat, while investors are expected to act as board members with angel investors being somewhat more actively involved than VCs (Van den Berghe and Levrau 2002; Van Osnabrugge 2000). The way these roles are executed in reality, however, may be substantially different. For instance, investors’ attempts to add value may sometimes result in excessive interference, which the entrepreneur may perceive more as a burden than a benefit. Indeed, entrepreneurs may not expect active participation from their financial partners and may see their VCs or angel investors much in the same way as banks, i.e. providers of only financial capital, not human and social capital. If this is the case, they will likely be surprised by actively intervening angel investors and VCs, which may cause friction. In some cases, however, intervention is necessary from the investors’ standpoint because of the entrepreneur’s lack of experience, professionalism or management capabilities (Parhankangas and Landstrom 2006). Such interventions, if unanticipated, may require investors to alter their own role definitions, which again may serve as a source of friction. Illustrations of such conflicts can be found in case C, where angel investors and entrepreneurs do not agree on how to run the business; the investors want the entrepreneur to focus on sales rather than technological development, while the entrepreneur thinks the investors are interfering and concerned only about their financial goals. In case D, investors are put off by the longer-than-expected/promised development times. In case E, the entrepreneurs are dissatisfied when their VC starts imposing unexpected additional costs, such as hiring a CFO. In sum, dissonance between expectations and actual executions of investors’ and entrepreneurs’ roles may give rise to a set of problems.

Strategic Problems

Changes in strategy may also engender ethical problems among venture partners. The entrance of a new partner can imply drastic strategic changes, as illustrated in case F, where the incoming VC changed the original plan to a more aggressive one aimed at rapid growth. From the VC’s perspective, a window of opportunity presented itself and had to be taken advantage of rapidly. However, this change in strategy not only increased the venture’s return potential, but also its risk for the entrepreneur and employees. While this fits within a VC’s overall strategy of portfolio diversification and risk spreading (i.e. over different investments), this is not traditionally the case for other partners involved, such as entrepreneurs and angel investors, who cannot achieve the same level of risk spreading. Hence, it should not be surprising that in case F, strategic changes resulted in problems between old and new partners. A change in strategy, however, can happen not only at the company level, but also can occur at the level of the investor’s fund. Different and painful for the entrepreneur is case G, where the VC carries out a strategic reorientation of its own fund and, as a consequence, refuses the follow-on investment he had previously approved for the company.

Governance Problems

Corporate governance also has an important role to play in this process, and several problems can arise. Governance focuses on devising incentive and control measures to ensure alignment of managers’ and owners’ interests. Governance issues pertain to control over and sound management of the company. Given there are multiple partners, or owners, governance works in several directions. For example, our vignettes illustrate that investors want to assure that entrepreneurs are acting in their best interest, while entrepreneurs are also concerned about investors acting in their best interest. Moreover, the board also plays an impactful role in assuring effective governance.

With multiple parties involved—often coming and going over the venture’s lifecycle—it is important to make agreements on governance, as reflected in representation on the board of directors and active involvement. The composition of the board is an essential part of the shareholder agreement. Besides a strategic role, the board has a monitoring and control role. In case ventures have different shareholder groups, boards also fulfil an important information and communication role. Given that key partners have a right to be represented in the board, new representatives tend to be added to the board throughout consecutive financing rounds. However, there are limits to a board’s size for reasons of efficiency. The traditional “solution” is that the number of representatives of older partners is decreased. For instance, as described in cases D and F, angel investors often make room for more professional board members. Most codes of corporate governance consider the number of independent board directors as an important guarantee of board independence (Klein 2002). While changing a board’s composition upon entry of new investors by replacing old investors’ representatives by those of new ones is not necessarily problematic, one needs to pay careful attention to safeguarding the board’s independence. In addition to their own representatives, VCs for instance often appoint new people out of their network as independent directors (as in case E). One may, however, question whether such directors can indeed be considered independent (Van den Berghe and Levrau 2002).

Investors also take measures to assure that entrepreneurs are acting in their best interest, where the facilitation of such cooperative actions is often described under the form of contracts and covenants. Those covenants have been gradually introduced by investors to protect them from fraudulent behaviour on the entrepreneurs’ part and to ensure their loyalty to the venture. Even if they are not meant to be used, they provide investors with all the legal possibilities to intervene (Cumming 2008). However, many restrictions in the contracts are “perceived as harsh and even unfair” (De Clercq et al. 2006, p. 99). In some cases, a lack of experience in legal and financial affairs means that entrepreneurs do not fully understand the impact of those covenants (e.g. case E), providing investors with an informational advantage. Specifically, these covenants determine the extent of control that is imposed on the entrepreneur; they can specify limitations in spending or other constraints that require the approval of the main shareholders. In certain instances, investors may not have the entrepreneur’s best interest in mind; in case I, the VC does not inform the entrepreneur of his investments in company I’s competitor. How can investors’ governance be in line with the best interests of the entrepreneur when they also partially own a competitor?

New professional investors impose more control and monitoring (Bonnet and Wirtz 2012), with administrative burdens for the entrepreneur. Different views on the use of control and on how this control may best be exercised may hence provide fertile grounds for conflict. VCs may, for instance, install mechanisms monitoring weekly sales evolution. Such follow-ups presented by the investor as professional management instruments and intended as positive stimuli may in fact be experienced by the entrepreneur as time-consuming and unnecessary pressures that contribute to deteriorating the climate between investors and entrepreneurs. In general, VCs and angel investors try to dampen agency problems through contractual and relational monitoring, with VCs relying more on the former and angel investors on the latter (Fiet 1995; Van Osnabrugge 2000).

Particularly in situations of urgency, governance principles are not always respected. Even if the law foresees a procedure to protect the rights of the minority shareholders, urgency does not always allow for sufficient time to launch the procedure. For instance, when a company urgently needs cash next week to meet its financial obligations, a capital increase needs time and preparation. Launching the procedure for minority shareholders would imply the company not being able to pay its bills and the board having to apply for bankruptcy. In case F, the VC offers a loan, but with severe conditions of interests and ulterior dilution, leaving the minority shareholders no other choice than to accept. In some cases, even “standard” principles of good governance, such as providing all information in advance (e.g. case F), are not adhered to. Moreover, the industrial investor may also use threats and intimidation techniques to get rid of the angel investors (Case D), while in case E, the VC threatens to sue the entrepreneur.

Control and monitoring can also lead to conflicts for control and hence perceived unethical behaviour. Mechanisms such as direct monitoring and incentive alignment reduce agency risks, caused by conflicts of interest between the owners and management of a firm (van Ees et al. 2009; Van Osnabrugge 2000). Direct monitoring encompasses systems through which a board can observe, control and evaluate management behaviour, such as budgets, accounting systems, executive remuneration and shareholder voting rights (Tosi and Gomez-Mejia 1989; Wiseman and Gomez-Mejia 1998).

Relational problems

Entrepreneurs and investors may have disagreements, divergent views or opinions, but also interpersonal incompatibilities that may lead to problems and conflicts. Contrary to the favourable effects of task conflicts to stimulate discussion, relationship conflicts decrease confidence in partner cooperation (Zacaharakis et al. 2010). Interpersonal dislikes and associated feelings of resentment and animosity may undermine the cooperation between two parties (Higashide and Birley 2002). The investor–entrepreneur fit remains important to build trust to avoid focusing on the emotional problems rather than on the tasks at hand (Zacharakis et al. 2010). Relational problems are present in several of our vignette cases, with different degrees. They manifest in case C, where opposing views on the business between the inventor and the CEO with a focus on technology or sales lead to deterioration of the work climate. In case G, a change of strategy of the VC leads to a serious change in the support for the venture. Changes of VC representatives in the board may also affect the good relations and impede on the collaboration. In many other cases, the problem and following conflict lead to changes in the relations between partners, with emotional consequences.

Entrants, injecting new funds, affect the relationship between the entrepreneurs and the prior investors (i.e. angel investors). As we previously discussed, this may create tensions when the partnership between entrepreneurs and angel investors is replaced by a new alliance between entrepreneurs and VCs, as in cases D and F. We see such a shift from alliances between the entrepreneur and the business angels to the new VC in case D or to the new industrial investor in case F and also in case L, where VCs negotiate a separate deal with the entrepreneur before their exit through delisting. In some cases, on the contrary, angel investors may even fulfil a mediating role between entrepreneurs and VCs. Similar problems due to changing roles may also present themselves as entrepreneurs and investor entrants experience conflict over control of the venture (e.g. cases E, G and I). In some cases, alliances between some investors or a group of investors may change and entail a shift in power distribution.

Valuation/Ownership Problems

Besides operational, strategic, governance and relational problems, we identify a specific problem in entrepreneurial ethics that can be a combination of the four categories: this problem encompasses valuation and ownership problems. Here, entrepreneurial finance is unique in that objective valuations must be made of highly uncertain, subjective ventures (Block et al. 2014). This is further complicated by the fact that venture partners come and go throughout the lifecycle, both of which give rise to ethical problems around valuation and ownership. Specifically, a key problem in entrepreneurial finance is related to the valuation of the company, which is accompanied by the delicate problem of dilution. In a fundraising operation, new shares are issued at a certain valuation—the result of negotiation between parties. At the time of entry or exit of every partner, this negotiation exercise takes place in a formal or informal, explicit or implicit way.

Valuation is a perilous exercise where a number of ethical problems can arise. Different partners put different efforts in the venture; the remuneration and rewards also differ between founders and later entrants. The founders, the entrepreneur and his team, often accept working hard and investing large efforts and time (i.e. sweat equity), at lower salaries in the first years in order to make their project succeed. A part of the remuneration is delayed largely because of financial techniques such as stock options or warrants. Entrepreneurs are willing to accept this higher risk with an upward potential in case of success. The goal is to obtain compensation for their efforts with a higher valuation of new entrants. Business angels at different phases, and often families and friends in the first round (Hellmann and Thiele 2014), also accept this higher risk in the early stages of venture development.

Clearly, given the profound implications, valuation (and dilution) becomes a critical and sensitive issue for venture partners. Entrepreneurs and early-stage investors are often diluted, meaning their percentage of shares can diminish as external capital increases. This valuation is often based upon the discounted value of future cash-flows. In case H, for example, one angel investor is pressured to sign a proxy to allow the capital increase to be executed and hence agrees with a serious dilution without having been consulted throughout the negotiations and without having received key documents, which the law requires. In case H and J, the asymmetry between different investors is illustrated. What seems to be a good deal for the one investor (in most cases the latest investor) does not always assure a profitable deal for earlier-stage investors and entrepreneurial team members who have experienced dilution. The importance for venture partners in this financial game is to keep their share percentage as high as possible so as to avoid dilution during the successive rounds of financing and loss of control. With high valuations in mind, the entrepreneur is thus in a position of conflict of interests, where a misrepresentation of reality (i.e. presenting better results or hiding crucial information (Pollack and Bosse 2014) can positively affect the valuation and hence the magnitude of dilution.

In these negotiations, though, entrepreneurs are often in a weak position due to time pressures and lengthy negotiation periods. Often, they lack viable alternatives other than accepting the deal terms as proposed by the selected investor. Some investors make use of this advantage by proposing low valuations and/or high dilution for the existing shareholders, especially when a company is running out of money (e.g. cases C, D, E and F). VCs also frequently employ a staged financing approach which creates “tough provisions that ensure participation in the upside and minimize exposure to malfeasance”, but may also cause entrepreneurs to lose ownership if their performance falls below target goals (De Clercq et al. 2006, p. 99). If milestones are not met, the VC has two alternatives: either to cut losses by not funding the next financing round or to invest at a lower valuation (De Clercq et al. 2006).

Closely related to valuation (and dilution) are problems of ownership among venture partners. Here, key players in entrepreneurial finance can take actions that influence the ownership of the other parties, such as blocked entry (Case A) or more commonly forced or blocked exits (as presented in case D, F and H). The VC market is renowned for being illiquid: VCs cannot sell their stock in a moment’s notice (Cable and Shane 1997). This statement holds even truer for minority shareholders; they do not have access to internal venture information, often lack board seats, and are bound by covenants. Given the right of first refusal and their small percentage of shares, angel investors thus generally have no possibility for exit other than being bought out by existing or new shareholders and following the major shareholder in exit strategy and decisions. Because resources are often scarce for entrepreneurs, angel investors often rely on VCs to be bought out. Thus, this presents the case of new investors (i.e. later-stage VCs) forcing angel investors to exit or blocking them from exiting. Consider the industrial investor in case D who tries to eliminate the angel investors with all means possible, while in case F, angel investors are blocked from exiting by the VC. Bylaws and covenants may also help to prevent exit-related conflicts given that they can limit venture partners’ decision latitude and can hence prevent some of the previously discussed issues related to unexpected or unilateral changes made (Cumming 2008; Dessein 2005). Other frequently used covenants specifically pertain to exit (Gompers and Lerner 1996; Kelly and Hay 2003). Some may restrict the purchase or sale of shares of the firm between venture partners, while others may oblige the entrepreneur to stay with the venture, precluding an exit if preferred. Other covenants allow investors to fire entrepreneurs if deemed necessary (i.e. in case entrepreneurs ignore the board’s advice or when milestones or revenues are not met). Sophisticated techniques can be used, such as ratchets, as incentives to adapt the share distribution in function of results (Utset 2002).

In negotiations of ownership, VCs are often a step ahead of the entrepreneur; their experience provides them with a longer-term and more realistic perspective than that of the traditionally overoptimistic entrepreneur who has experienced fewer deals. Exit provisions for VCs may hence result in a “sophisticated transfer of control from the entrepreneur to the VCs as financial investments increase” (Smith 2005). The entrepreneur often realizes this only when milestones are not met and the VC exercises his rights as stipulated by these covenants, which the entrepreneur can potentially perceive as an abuse of power. Covenants are sometimes used in an unfair manner. Consider case F, where VCs effectively use their right of first refusal to block the angel investors from exiting and by refusing access to the data and due diligence to a new potential investor the angel investors had proposed. In case F and H, the angel investors are not consulted when new deals for the next financing round are closed.

An Integrative Discussion and Multi-Ethical Perspective Analysis

It becomes apparent that a wide variety of ethical issues exist in the financing of entrepreneurship, and thus, focus on one ethical perspective may limit our ability to reason about such actions—particularly given the heterogeneous nature of problems that can arise. Thus, instead of viewing these problems more narrowly through one ethical lens, we introduce ethical problems of entrepreneurial finance by demonstrating the potential of analysing such cases through the lenses of multiple ethical perspectives (Crane 1999; Crane and Matten, 2004; Kidder 2005) as in multi-paradigm research (Sheep 2006; Carr and Valinezhad 1994). Considering multiple perspectives can reveal both disparity as well as complementariness across perspectives (Child et al. 2003; Crane 1999; Sheep 2006). Consider Kidder’s (2005) demonstration that integrating trait, agency and psychological contracts theories can work in concert to improve our understanding of detrimental workplace behaviours. Child et al. (2003) tested multiple theoretical perspectives pertaining to cross-border affiliate performance and found all three to have unique explanatory power. Tapping into some of the benefits offered by the multi-perspective approach, we explore several delicate issues and then formulate some possible solutions for the special case of blocked and forced exit. The case analysis from different ethical perspectives is presented in Table 3.

First, in all cases except one, the analysis of the ethicality of the behaviour shows problems in view of the principle of fairness and in view of the principle of greatest happiness. In fact, in our case studies, most evaluations according to these two perspectives coincide. Many of the presented actions also have a degree of non-respect of the ethics of duty principle. Only case C survives the test on the three perspectives. This exit situation is clearly a relational problem, caused by different views on the operational side without any unfair and unethical conduct.

The within-case analysis provided an overview of reasons for conflicts and potential ethical pitfalls which might endanger the cooperative relationship between entrepreneurs, angel investors or VCs throughout the different stages of a venture’s lifecycle. By using these different ethical perspectives, we are be able to get a comprehensive overview of considerations and aspects pertinent to the moral assessment of issues at play between entrepreneurs, angel investors and VCs. Applying the Triple Font of Morality Theory, we find ethical problems related to the three elements of morality: the behaviour of some protagonists in all cases offers negative consequences; in most cases, the action chosen is also negative except for case C, where the action is neutral. Concerning the intention, we find a different scenario, from fair intention (case C), normal conflicts (case D) and unpredictable changes (case G) to deliberate plan to deceive one’s business partners (case B). In case G, the change of strategy of the VC has no intention to harm, but has severe consequences for the entrepreneur. However, in some cases, there is a hidden agenda, a clear example of dubious intention: pursuing negotiation with another party and then bluntly dropping a prior agreement to a first party (case A); investing in a competing company without disclosure (case I); buying out minority shareholders while having a trade sale arranged before (case K and L). In many deals that lead to unbalanced outcomes and unequal consequences, there was no intentional idea to harm other investors. In case J, the differences in benefits are the mathematical result in valuation at the different timings of the successive rounds of financing.

Intentions in some other cases are more dubious or questionable: dilution of prior investors can simply be a normal consequence of unforeseen bad performance, but can also be the purposeful result of a Machiavellian plan. Problems occur when one major party wants to impose its vision (in that case for exit) without taking the other partners into consideration.

Contracts and negotiation

Applying the various ethical perspectives on the negotiation of contracts reveals some problems of deontology. Case A, where the entrepreneur retracts his given word to the angel investor, illustrates opportunistic and unethical behaviour. The annulled deal may present an opportunity cost. The investor spent time in the analysis and conducted due diligence on the project, while the entrepreneur just used him to negotiate with a third party.

Cases B, D, E, H and I present problems of deontology with unequilibrated contracts. They do not respond to the greatest happiness principle, nor to principles of fairness. Perceptions of unfairness can generate dysfunction within organizations and conflicts between their stakeholders. And what one party considers as normal or acceptable does not alter the fact that it might be seen as unethical by the other party. One of the important aspects is a disconnect in time between the unethical action and the conflict. The unethical practice may have been undertaken long before the perception by the other party arises. As an example, when dilution of the entrepreneur’s share arrives following the missing of some milestones of the contract, the entrepreneur feels unfairly treated, while the VC is simply exercising his contractual right setup months or years before. The perception of the entrepreneur is often different: she considers this as an abuse of power and in fact realizes this abuse of power occurred much earlier, upon signing the contract in a situation of power inequality. This also implies that we may have a different evaluation of the ethicality of the behaviour ex ante or ex post.Footnote 4 The perception of unethical behaviour only rises when the conflict appears and when the party realizes—or imagines—she had been unfairly treated previously. The perception of the intention may differ ex ante and ex post. Where an entrepreneur may see no ethical problem when signing the contract, even with harsh clauses, she may experience a different opinion ex post, when some of the clauses as dilution are taken into execution. In hindsight, she may believe that the investor had perfidiously introduced this clause with the hidden agenda to dilute, whereas it may be meant only as a security measure. So, one may also attribute false intentions to partners. This phenomenon explains a possible asymmetry of perception of ethicality and thus the difficulty of judgment in these ethical matters.

When negotiating contracts and including such covenants, it is fundamental to establish that all partners involved have a clear and correct understanding of the meaning and implications of these covenants. Generally, covenants are foreseen to preserve the investor against mala fide practices, with no negative intention. One must also ensure that covenants are used in a fair manner. When these covenants have to be applied and display unfair consequences, one should return to the intention and the spirit of the contract and rectify.

Governance

Governance issues also often have an ethical component, as illustrated in cases A, C, D, E, F, H, I, K and L. Not respecting governance codes is against deontology. In most of the cases of poor governance, principles of fairness are not followed, nor the greatest happiness principle. As most angel investors prefer to be actively involved in the venture, and when the role of each partner evolves from being active and hands-on to passive, the role of governance escalates. Too many errors occur, such as neglecting to inform incumbent partners not only formally, but also in informal ways. Often it is the way people are treated that creates negative sentiments (Gino et al. 2009; Collewaert and Fassin 2013). Most of these problems arising from changing roles of prior investors could probably be avoided or solved by including or at least informing the other partner in all deal discussions that he or she will be affected by as well as by making clearer agreements upfront in terms of role definitions. These information channels are, however, crucial to keeping inactive angel investors informed and connected to the venture (Yitshaki 2008). Independent board members, even if chosen by the major shareholder, should function in an independent way. In particular, the independent Chairman has the implicit responsibility to safeguard all shareholders’ interests, and especially that of the minority shareholders. To enable smooth exits of venture partners, more attention should be paid to respecting minority shareholders’ rights. Finally, even if many contracts negotiated with VCs confer these rights to lay off the founder–CEO at any time, it remains a delicate operation that should be realized in a decent and fair way in the interest of the company.

Information Manipulation and Insider Trading

Another delicate issue of the ethics of entrepreneurial finance relates to the abuse of knowledge asymmetry (as in cases A, B, K and L). Manipulation of information by entrepreneurs, voluntary concealing information, or false statements around product and technology features, market assessment and accountancy documents obviously conflict with all ethical principles. In case K, it is the entrepreneur who hides an acquisition proposal to his investors. Neither the action chosen nor the intention is in line with morality. But as presented supra, VCs sometimes take advantage of their knowledge. Entrepreneurial finance uses a set of rules that contains a number of more advanced financial engineering techniques that not all partners may understand. Entrepreneurs who are not specialized in this finance game do not always see the possible implications. As experts, VCs know the rules and the intricacies of fund raising and know perfectly how the financial game of valuation works. From experience in other ventures, VCs know that in case of success and high growth, the venture will need more cash; they also know that many entrepreneurs—in their over-optimism—do not always meet key milestones. When not all the players know the rules being played and are “at least ignorant of the most important ones, ones that determine the big wins and big losses”, the game is unfair (Werhane 1989, p. 841). Making abuse of one’s knowledge advantage questions the intention of the action. Insider trading (as in case J and K) based on privileged information gives unfair advantages to those actors (Werhane 1989). These actions infringe upon deontology and utilitarian perspectives and hurt principles of basic fairness. From a deontological perspective, current and potential shareholders have a right to unbiased or unmanipulated information from their agents (Brooks 2010, p. 465). The utilitarian perspectives argue that insider trading increases market efficiency, whereas fairness principles and basic market morality tend against insider trading (Engelen and Van Liedekerke 2007). Contrary to some projects, where the founders or VC investors highly marketed the future potential of their venture before IPO, in the case L, the founder seems to underplay the market potential in order to buy back his individual investors on the stock exchange to make a larger profit himself. This behaviour of insider trading is against deontology and against the principle of fairness and even illegal in some countries.

As stock options and warrants for managers and VCs benefit other stakeholders in smaller part who do not participate in these negotiations, ethical problems arise from both utilitarian and organizational justice perspectives (cases F, H and J). The size of executive pay package reflects “a winner-take-all approach that conflicts with a deeply and widely held moral understanding about fairness” (McCall 2010, p. 561). In these remuneration issues, a decent decision-making process is needed in respect of corporate governance principles.

Valuation and Dilution

Valuation and dilution are also salient considerations in the realm of entrepreneurial finance (cases A, B, D, E, F, H and I). New investors have the power of the money, which the entrepreneur desperately needs—often giving investors a serious advantage in the negotiation process. Here again, the various ethical perspectives raise questions regarding deontology, consequences and fairness. While trying to negotiate low valuations is part of the game for VCs, or any other investor for that matter, negotiations must occur in a fair manner, absent excessive pressure or abuse of power. Even if with his capital injection this new investor saved the company and, as a consequence, also the shares of the original investors, this does not mean that he should neglect the rights of the other investors of previous rounds. Even with contractual agreements, this investor who wants to realize a short-term capital gain could envisage allowing a better price for the business angel and the first VCs. Entrepreneurs placed in that case have more power than business angels; if they do not cooperate with the acquirer, often the venture has no future, making the deal vulnerable.

Applying a multi-lens ethical perspective on the valuation and dilution problem also offers interesting insights. From a rights-based theoretical approach, the legal view, in case J, advantages the property rights given to all shareholders as agreed in the contract. Applying the contract is valid, even if a mechanistic application of the agreement leads to unhappiness of some of the parties. In some cases, the outcome of the dilution—as foreseen in the contracts—does not necessarily correspond to the intention. The intention of hard compelling measures in contracts in case of not meeting the milestones is to safeguard the investors, not to squeeze the entrepreneur and early angel investors; however, if other external circumstances (as the general economic climate or technology changes) are the causes that the milestones are not met, principles of fairness would advise waiving the milestone and to re-allocating the dilution criteria. Using the hard criteria to force a dilution for false reasons would be against deontological principles and not in line with the spirit of the contract. The legal solution does not lead to respect for the greatest happiness principle. The common good approach would place the objectives and company as central. From a utilitarian perspective, the legal solution does not benefit all parties involved.

Applying principles of organizational justice to the proposal in case J confirms that the deal does not give satisfaction to all partners even if the intention was correct in the level of interpersonal treatment the negotiation of the contract had intended with respect to all parties involved at that time. According to Dalton and Dalton (2010, p. 560): “The fairness of a distribution, when the benefits are the product of a common enterprise, can be determined by the relative contribution made and risk assumed by the respective parties”. In this case, both risks and contributions are unequally distributed within the team and unequally according to their participation in the capital. The outcome of applying the contract would not be in line with the principle of fairness of outcome and with the intention. On the level of the allocation process, the agreement was made on a fair basis; it is the offer at a very premature stage that distorts the relative rewards.

Moreover, “Fairness in the distribution of benefits and costs among stakeholders is an important ethical concept but not one enshrined in the law” (Brooks 2010, p. 465). This principle is evenly valid for one specific category of stakeholders, namely shareholders. Applying the principles of fairness to case J, we come to the following solution. The VC investors again would advise re-equilibrating the deal and allocating more to the first VC and to the angel investors than originally foreseen by the mathematical application of the contracts. In some contracts, ratchet formulas allow renegotiation under changing situations or, if not foreseen, a voluntary flexible solution ad hoc can rectify the distortions of the financial game with respect for the needs and contributions of each. Possible negative consequences can be altered when put in line with the intention.

The Case of Blocked and Forced Exit

The special cases of forced and blocked exit (cases F, G, H, I and J) pose the question of right and fair reward for angel investors. These cases emphasize the need for distributive and procedural justice. Angel investors often assume the most risk by investing in the seed phase of the venture and often spend much time advising and helping the entrepreneur without any remuneration. At some point, angel investors thus expect to be fairly rewarded for their work during the first difficult years of the venture and will generally not accept exiting at the entrance price. In case of success, their work and investments have permitted the venture to arrive at the stage it has now reached; in less-successful situations, angel investors want to capitalize on an exit at a later time, for instance, through an IPO. Some angel investors may like to share in the success and may therefore refuse to exit (case D), while others may choose to refuse high risk and should have the possibility of a fair exit (case F and H). New investors may, however, argue that success will be realized only thanks to their efforts and to their new aggressive strategy, thereby refusing to buy the old investors out, and certainly not at a higher premium. From a VC’s perspective, such an action would not make much sense, given that it does not bring in any additional funds into the venture, nor does it give them any additional control. This leads us to a serious ethical and governance question in entrepreneurial finance: Is it acceptable and fair that minority investors are blocked and have no exit possibility? Is it fair that minority investors can be forced into an uninteresting exit? Is it acceptable that one minority angel investor can block a deal for reasons of corporate governance and even based on contractual rights, while the deal would benefit the company, but would harm his own interests? From an ethical point of view, the cases posit in an exemplary way the issue of a fair price and exit for minority shareholders and especially angel investors.

Some solutions could be proposed. A blocked or forced exit does not correspond to the intention of the original deal, but is an unwanted negative consequence of the legal contract. A fair deal should acknowledge each partner’s contributions and should try to meet each partner’s goals. For instance, one may propose an exit at the angel investor’s entrance price accrued with a normal interest, potentially combined with an increase up to half of the capital gain when VCs and entrepreneurs decide to sell their shares or when they launch an IPO. The latter may in turn be combined with a declining percentage depending on the duration between this exit operation and the final exit through trade sale or IPO. Such an elegant exit agreement will allow angel investors to recover their initial investment and will reward them with some upward potential in case the venture they helped to launch is successful. A similar mechanism has been applied in the case L, but incompletely as benefitting only the VCs. Furthermore, this proposition also addresses the new investors’ needs and goals because it leaves them (and the entrepreneur) with complete control. Finally, this solution will also allow angel investors to reinvest the capital gained into a new venture, which may subsequently offer new investment opportunities for VCs. An alternative could be the development of a specialized fund that buys shares of angel investors. In return, angel investors could be offered shares of the fund. Not only would it provide them an attractive exit route, it would also allow them to benefit from the fund, which holds a wide range of small participations in different companies and hence allows them to spread some of their risks like VCs.

Synthesis

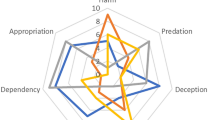

Starting from the asymmetries and tensions in the entrepreneur-investor relation, we identified issues with ethical aspects and potential for conflict; in particular, we found conflicts of interest and abuse of power at the origin of several configurations of unethical behaviour. Conflicts of interests are present with different magnitude in nine of the twelve cases. They appear in the deal structuring with valuation issues, but also in the hiding or manipulation of information and insider trading. These behaviours constitute rent extraction from other partners for one’s own benefit. Abuse of power is also present in eight of the twelve cases. It appears under forms as threatening, as neglect of minority shareholders or just as application of the advantageous clauses of a contract imposed at an earlier stage. Both conflicts of interest and abuse of power clash with the intention, with the action chosen, and with unfair consequences.

Applying principles of greatest happiness, fairness of outcome, fairness of the allocation process, fairness of the interpersonal treatment and the duty as motive to each of the conflicts categories will allow better decisions. Ethical and fairness perspectives, if taken into consideration, will benefit the cooperation between partners.

Implications and Call for Future Research

Scholarly Implications

Ethics-related behaviours in finance and a focus on improving those behaviours have been the centre of a vibrant body of research on large corporations. While important, this research has left ethics in the realm of entrepreneurial finance sparsely considered. The entrepreneurial financing process, from inception to exit, poses a number of unique ethical issues—yet we are presently left with a limited understanding of this nexus. By focusing on ethics in entrepreneurial finance, our study takes a stride towards advancing this important omission. Specifically, this paper contributes research on tensions, conflicts and dysfunctional relationships in the financing of entrepreneurship, especially during key moments such as entry and exit of new venture partners. This explorative study adds to the entrepreneurship literature by shedding more light on the dynamics of relationships among entrepreneurs, BAs and VCs. It illustrates the tensions experienced by the entrepreneur in maintaining ownership and control in growth stages. Our cases illustrate the difficulties associated with balancing organic ownership and professional management and confronting the rational and emotional dimensions in the decision-making necessary to entrepreneurial ventures (ten Bos and Wilmott 2001). Distinctively, our analysis allows us to gain insights into some of the ethical issues that may arise throughout a venture’s financing lifecycle leading up to the exit of investors or entrepreneurs. Whereas classic ethical theories focus on the ethical analysis of the action itself and its consequences, this application of ethics in entrepreneurial finance illustrates the importance of including the analysis of the intention in the ethical analysis, following Mele’s Triple Font of Morality Theory (2012). In addition, it also adds to the literature on negotiation ethics in the special case of entrepreneurial finance.

In ethical decision-making analyses, evaluations of the ethicality of decisions can be based upon different perspectives, especially consequentialism, deontology, organizational justice and fairness. These analyses also investigate the impact on the various stakeholders. Curiously, while traditional stakeholder theory has focused on the divergence between different stakeholders’ interests, the present analysis emphasizes the differences among a specific group of stakeholders, and especially among the shareholders who are seen as the most important stakeholder group in most economic theories and in corporate governance. This discussion illustrates the intra-heterogeneity of stakeholders, and in this case more particularly the intra-heterogeneity of shareholders, and the multiple role aspect—two often overlooked issues in stakeholder management (Fassin 2008). Our research, therefore, links corporate governance, business ethics and stakeholder theory. Our advice, based on our analysis through different ethical perspectives, leads to a solution that also follows the principles of stakeholder management. By connecting ethical perspectives and a stakeholder approach to the group of varied shareholders, we come to a better conclusion than possible through the pure application of legal and corporate governance principles. Thus, we concede that scholars investigating ethics in finance would do well to adopt the multi-ethical lens approach in future research efforts, given the potential utility that such an approach offers.

Moreover, our research also contributes to the delineation of key differences between the legal and the ethical dimension of decisions (Arjoon 2005). Ethics goes beyond the law (Carroll 1991). When the pure technical application of the legal contracts may sometimes lead to problems, an ethical decision will take into account the original intent. In the financial world dominated by the Anglo-Saxon vision and compliance (Michaelson 2006), this message could help to improve the fairness of entrepreneurial ventures for the benefit of all. Sole compliance cannot be a substitute for fairness and ethical treatment of all stakeholders—particularly in the realm of finance. Thus, scholars of entrepreneurial finance would do well to look beyond legal compliance to ethics and ethical perceptions in an effort to better understand ways in which positive ethics may be integrated into the high risk and high stakes context of entrepreneurial financing partnerships. In this way, we plead for the thorough implementation of existing codes of ethics, codes of corporate governance and principles of good conduct of the various associations in the practice of entrepreneurial ventures.

Avenues for Future Research