Abstract

This article presents the results of a cross-cultural study that examines the relationship between spirituality and a consumer’s ethical predisposition, and further examines the relationship between the internalization of one’s moral identity and a consumer’s ethical predisposition. Finally, the moderating impact of cultural factors on the above relationships is tested using Hofstede’s five dimensions. Data were gathered from young adult, well-educated consumers in five different countries, namely the U.S., France, Spain, India, and Egypt. The results indicate that the more spiritual an individual consumer is, the more likely that consumer is to be ethically predisposed. Furthermore, the stronger one’s internalization of a moral identity, the more likely one is to be ethically predisposed. These two relationships are further moderated by Hofstede’s cultural factors such as the degree of collectivism versus individualism in the culture. However, the strength and direction of the moderation may vary depending upon the specific Hofstede dimension.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Religion has a significant influence on many people’s lives. It affects human behavior in terms of moral standards, beliefs, judgments, attitudes, and ultimately actions. One’s own individual moral identity also affects moral beliefs and behavior in similar myriad ways. Previous research has indeed shown that religion and moral identity affect consumer decision making and attitudes. However, no one has yet examined the impact of these two constructs on consumers’ moral attitudes within a cross-cultural context. That is, the unanswered question is “what is the role that culture plays in shaping consumer attitudes and opinions, and, more specifically, how does this impact the roles of religion and moral identity on moral attitudes?” However, in order to “control” for differences in religions across cultures, spirituality will be examined within the context of this study in lieu of religion. While spirituality and religion are indeed related, the former may be defined as a “search for universal truth” (Goldberg 2006), whereas the latter tends to be associated with more formal beliefs and group practices as related to existential issues. Thus, while religion and religious practices differ from culture to culture, spirituality is a construct that tends to be more universal in nature even perhaps applying to those who do not follow any particular traditional and formalized religion. That is, one’s spirituality may, or perhaps may not, be related to active membership in a specific religious group, but it does involve belief in a higher power and acting in more ethical and socially desirable ways in either case. As a potentially broader concept, spirituality has the advantage of being able to encompass and have applicability to individuals from various distinct religious beliefs. Given that the present study is a cross-cultural one that includes individuals from many distinct religious backgrounds, spirituality is presented as a logical surrogate for religiosity.

The notion that one’s religiosity, and alas spirituality, might influence an individual’s ethical judgments, beliefs, and behaviors would appear to be somewhat intuitive. Functionalist theory in sociology credits religion with promoting norms that reduce conflict and impose sanctions against antisocial conduct. Religiosity can, thus, be viewed as exercising control over beliefs and behaviors (Light et al. 1989). A major theme in functionalist theory is that religiosity, and by inference spirituality as well, is a stronger determinant of values than almost any other predictor (Huffman 1988). Thus, it is clearly germane to examine the relationship between spirituality as a kind of surrogate for religiosity, and ethical beliefs and attitudes as well as its relationship to other antecedents, such as moral identity and culture, within the ethical decision-making process.

As for moral identity, it is defined as one’s self-concept “organized around a set of moral traits,” such as compassion, fairness, generosity, and honesty (Aquino and Reed 2002; Reed et al. 2007). That is, the individual has in mind a specific sense of identity or a self-definition about the moral aspects of oneself. This revolves around certain perceptions regarding the characteristics, feelings, and behaviors of a moral person. The individual may then draw upon his or her moral identity to make moral choices in one’s everyday relationships with others. In general , moral identity is essentially a “kind of self-regulatory mechanism that motivates moral action” (Aquino and Reed 2002, p. 1423). Moral identity is therefore an important construct with the potential to predict ethical judgments, intentions, and moral actions (Weaver 2006; Trevino et al. 2006).

Based on insights from the Hunt–Vitell (1986) General Theory of Marketing Ethics, culture is considered to be antecedent to the process of ethical reasoning. Similarly, spirituality and moral identity are viewed as antecedents to the ethical reasoning process. However, just how these “antecedent” constructs might interact with one another in forming an individual’s ethical attitudes and beliefs is not explicated in the original theory. Thus, it is the objective of this paper to explore and clarify these processes within a cross-cultural, consumer ethics context.

Since relatively little is currently known about the impact of culture on the relationships between spirituality and consumer ethics, and moral identity and consumer ethics, there is a need for programmatic research to examine these issues. Thus, the objective of the current study is to partially fill this research need by examining the role of culture in impacting the influence of spirituality and moral identity on an individual consumer’s ethical beliefs and attitudes. Once this has been achieved, then it becomes possible to begin to compare consumers from varying cultural perspectives on important ethical issues.

Furthermore, while the impacts of spirituality and moral identity on ethical attitudes/beliefs seem to be already established, a review of the role of religiosity in consumer ethics (Vitell 2009) has called for cross-cultural studies to be conducted to determine the role religiosity/spirituality plays in ethical decision making. This same need for cross-cultural studies can be said to exist for the moral identity construct. Thus, as stated previously, the objective of this paper is to explicate how the various elements of culture impact the relationships between both spirituality and moral identity and consumer ethics.

Theoretical Foundations

Consumer Ethics

In the early 1990s, Vitell and Muncy (1992) identified the lack of focus on the buyer side of the buyer/seller dyad and observed that the research involving consumer ethics was very limited. They found only a handful of extant studies that empirically studied consumer ethical judgments (e.g., De Paulo 1987; Davis 1979; Wilkes 1978). Therefore, they (Vitell and Muncy 1992; Muncy and Vitell 1992) developed a consumer ethics scale and discovered that consumers react quite differently depending upon the kind of ethical issues/situations that they are faced with. Furthermore, they discovered four distinct dimensions relating to these ethical issues/situations, namely actively benefiting from illegal activities, passively benefiting at the seller’s expense, actively benefiting from questionable, but generally legal practices, and no harm activities. The first dimension (actively benefiting from illegal activities) represents those actions in which the consumer is actively involved in terms of receiving benefits at the expense of the seller. In other words, the consumer makes a conscious decision to harm the seller (e.g., changing price tags on merchandise in a retail store). The second dimension comprises situations where the consumer is the passive beneficiary of the seller’s mistake (e.g., not saying anything when you receive too much change from a store clerk). Here the consumer does not create the benefit intentionally, but rather is the serendipitous recipient of benefits. Consumers are more likely to find the actions in this second dimension acceptable as compared to those in the first. The third dimension consists of actions in which the consumer actively engages in questionable practices, but not necessarily activities that may be perceived as illegal (e.g., using a coupon for merchandise that the consumer did not purchase). Finally, the last set of actions is those that are not perceived to cause direct harm to anyone (e.g., copying a DVD from a friend rather than buying it). These actions may indeed very well cause harm, but are not readily perceived as doing so by many. If consumers believe that these potential actions are wrong, one might state that they have an ethical consumer predisposition in contrast to an unethical predisposition. Overall, this scale has been used widely in subsequent research (e.g., Rawwas et al. 1994; Polonsky et al. 2001). More recently, a fifth dimension entitled, “doing good” was added to the consumer ethics scale (Vitell and Muncy 2005). This is a positive dimension including actions such as doing “good” and recycling (e.g., buying a recycled product even if it is more expensive). If consumers believe that these actions are not wrong, one can again argue that they also have an ethical consumer predisposition. In the present study, only the actively benefiting, passively benefiting, and doing good dimensions will be used as the other two dimensions may be potentially viewed as ambiguous with many consumers believing that no harmful activities are acceptable when in reality they often do cause harm to others.

Spirituality

As mentioned already, spirituality, while perhaps somewhat overlapping the concept of religion, remains distinct from religion. Religion tends to indicate a belief in a particular faith system, whereas spirituality involves the values, ideals, and virtues to which one is committed. Thus, in a sense, spirituality is most related to an intrinsic view of religiosity as both represent a commitment to values and ideals. Allport (1950) perceived religious motivation as differentiated into intrinsic religiousness and extrinsic religiousness. More specifically, the “extrinsically motivated person is viewed as using his religion to fulfil other basic needs such as social relationships or personal comfort, whereas the intrinsically motivated lives his religion,” (Allport and Ross 1967, p. 434). Donahue (1985) pointed out that intrinsic religiousness correlated more highly than extrinsic religiousness with religious commitment. On the other hand, extrinsic religiousness is the sum total of the external manifestations of religion. He further notes that the extrinsic construct does not measure religiosity per se, but measures one’s attitude toward religion as a source of comfort and social support (p. 404).

As a guide for empirical research, the Hunt–Vitell (“H–V”) theory of ethics provides us with a general theoretical framework of ethical decision making. Furthermore, the theory draws upon both the deontological and teleological ethical traditions in moral philosophy (Hunt and Vitell 1986, 1993). Hunt and Vitell (1993) in their “general theory of marketing ethics” consider religion and related individual beliefs such as spirituality as important factors that influence one’s ethical judgments. The religious/spiritual beliefs of an individual influence the ethical decision-making process (Hunt and Vitell 1986, 1993), and individuals who tend to be more “intrinsically” religious, and by inference more spiritual, have been found to be more ethical in their beliefs (Vitell and Paolillo 2003). Furthermore, the H–V theory provides a framework to recognize the reasoning behind the ethical decision making used by individuals facing ethical dilemmas and ethics-laden situations. Religiosity is strongly associated with spirituality and encourages morality (Emmons 1999). That is, religiosity has a very strong connection with morality, in the sense that religion prescribes morality, and is considered to be the source of morality by many religious persons (Geyer and Baumeister 2005).

The H–V theory suggests several points where spirituality and religiosity may impact ethical decision making, namely (1) in determining whether or not there is an ethical problem/issue that one must resolve, (2) in determining whether or not there is an impact on one’s moral philosophy and/or norms, (3) in determining, as implied above, one’s ethical judgments regarding a particular situation and various courses of action, (4) in determining one’s intentions in a particular situation involving moral choices, and finally, (5) in determining actual behavior in such situations. The third category, ethical judgments, will be the focus of this research.

Spirituality is often more highly correlated with religious commitment and ethical beliefs, and given that this is a cross-cultural study involving people of varying religious backgrounds, it is logical to use a spirituality construct rather than a religious one. Walker and Pitts (1998) assert that traits of a moral individual can be seen in an individual who is devoutly religious and/or spiritual. Accordingly, individuals with higher spirituality would tend to have a greater level of commitment toward moral and ethical beliefs. Also, people with high spirituality would tend to consider ethics to be highly important in their lives; thus, such individuals are ethically more conscientious (Vitell et al. 2005). A priori, compared with nonspiritual people, one might suspect that highly spiritual individuals would have more clearly defined deontological norms and that such norms would play a stronger role in their ethical judgments. Thus, it is hypothesized that:

H1

Individuals higher in terms of their spirituality will be more likely to have an ethical consumer predisposition; that is they will be more likely to believe that “(a) actively and (b) passively benefiting” consumer activities are wrong and that “(c) doing good” activities are not wrong.

Moral Identity

Moral motivation stems from two complementary sources—moral reasoning and moral identity (Vitell et al. 2009). Moral reasoning is defined as the cognitive activity of processing information about issues to make moral judgments (Jones 1991) and is presumed to be one of the strongest predictors of ethical behavior (Shao et al. 2008), whereas moral identity is defined as “a self-conception organized around a set of moral traits,” which has also been shown to motivate moral action (Aquino and Reed 2002). Moral identity comprises two dimensions of self-importance—one private and the other public (Aquino and Reed 2002). The internalization dimension reflects the self-importance of one’s moral characteristics, whereas the symbolization dimension reflects the sensitivity regarding how one’s moral actions are perceived (Aquino and Reed 2002). Individuals who have a higher self-importance of moral identity and individuals who are more empathetic toward others are less likely to engage in unethical behavior without apparent guilt or self-censure (Detert et al. 2008). The stronger the internalization dimension of moral identity, the more likely it is to be reflected in one’s beliefs and behaviors (Aquino and Reed 2002). This implies that individuals who value moral virtues as an integral part of their identity are less likely to act unethically.

Empirical studies suggest that the rational view of moral motivation based on reasoning alone is insufficient to explain moral actions unless it is complemented with a moral identity view (Aquino and Reed 2002). This moral identity view reflects the “extent to which the elements most central to a person’s identity (e.g., values, goal and virtues) are moral. That is, when moral virtues are important to one’s identity, this yields motivation to behave in line with one’s sense of morality” (Hardy 2006, p. 215).

The proponents of the moral identity model argue that individuals form their identity by making moral commitments that are central to their self-definition and self-consistency (Bergman 2004). One implication of the moral identity model is that individuals may have similar moral beliefs but differ in how essential morality is to their self-identities. Specifically, Aquino and Reed (2002) propose that people construct their moral self-definition in terms of traits around which personal identities are organized. Thus it is hypothesized that

H2

Individuals higher in terms of the internalization of their moral identity will be more likely to have an ethical consumer predisposition; that is they will be more likely to believe that “(a) actively and (b) passively benefiting” consumer activities are wrong and that “(c) doing good” activities are not wrong.

Hofstede’s Cultural Framework

In order to measure individual cultural differences, this study will incorporate Hofstede’s (1983, 1984) cultural taxonomy. It encompasses five distinct cultural values: power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism/collectivism, femininity/masculinity, and long-term orientation. According to Nakata and Sivakumar (1996), Hofstede’s taxonomy captures the major components of culture, integrating the relevant cultural dimensions proposed by other studies. While Hofstede’s framework is essentially a global/macro measure of national culture, the various country indices were developed by aggregating the measures of individuals within various cultures. Thus, national culture can be (and was) measured at the individual or micro level as well using Hofstede’s dimensions. That is, it is precisely the aggregation of the beliefs of individuals in a society that establishes a unique, more global, national culture. However, within any particular society, there will be differences among individuals in terms of these beliefs. As Auger et al. (2004) state, there is likely to be more variance among those within a single culture or country than between different countries regarding various social issues including even recycling. Extending this to Hofstede’s dimensions, for example, some individuals, within the same culture, will tend to be more individualistic, while others may tend to be more collectivistic. Similarly, some individuals may be quite strong in terms of uncertainty avoidance, while others may be weak in terms of this dimension although both reside within the same culture. Thus, it is quite appropriate to measure these dimensions at the individual level as will be done in this research.

Power Distance

Power distance is a gage of interpersonal power or the influence a superior may have over a subordinate. It is defined as the degree to which the members of a group or society accept the fact “that power in institutions and organizations is distributed unequally” (Hofstede 1985, p. 347). Individuals with a higher power distance more easily accept the inequality of power as they perceive differences between superiors and subordinates as the normal condition of things; furthermore, they are reluctant to disagree with superiors and believe that superiors are entitled to privileges (Hofstede 1984). In contrast, individuals lower in power distance are less likely to tolerate class distinctions, are more likely to prefer democratic participation, and are not afraid to disagree with their superiors.

Uncertainty Avoidance

Uncertainty about the future is a basic fact faced by individuals in all cultures, generating anxiety and uneasiness. In response, people try to cope with uncertainty through different means such as technology, the law, or perhaps religion. The tolerance for uncertainty, and the means of coping with it, can vary significantly from culture to culture and from individual to individual. Hofstede (1985) defined uncertainty avoidance as “the degree to which the members of a society feel uncomfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity, which leads them to support beliefs promising certainty and to maintain institutions protecting conformity” (pp. 347–348). Individuals with high uncertainty avoidance are more concerned with security in life, feel a greater need for consensus and written rules, and are intolerant of deviations from standard practices as compared to individuals with low uncertainty avoidance (Hofstede 1984).

Individualism/Collectivism

Individualism refers to the relationship between an individual and the collective interests of the group(s) to which he/she belongs. Individualism has been defined as the extent to which an individual pursues self-interests, individual expression, and prefers loose ties with others in society as compared to more formal ties (Hofstede 1984; Triandis 1995). Individualists tend to value personal time and freedom (Hofstede 1984; Parsons and Shils 1951), and independence (Schwartz 1994), and also tend to believe that personal interests are more important than group interests (Hofstede 1984; Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck 1961). In contrast, a collectivist views him/herself as part of a group, and thus places group interests first. In addition, collectivists, and collectivist cultures, value reciprocation of favors and a greater respect for tradition (Schwartz 1994).

Femininity/Masculinity

Masculinity has been defined as “a preference for achievement, heroism, assertiveness, and material success” (Hofstede 1985, p. 348). Individuals from masculine cultures are characterized as assertive, aggressive, ambitious, and competitive with an orientation toward money and material things (Hofstede 1984). In contrast, individuals belonging to less masculine cultures (or feminine cultures) are described as modest, humble, and nurturing. They measure achievement in terms of close relationships, and are more people oriented, more benevolent, and less interested in personal recognition, than those from masculine cultures (Hofstede 1984).

Long-Term Orientation

Although not originally a part of Hofstede’s (1984) framework, long-term orientation represents a unique and distinct factor. It represents an orientation that emphasizes virtues such as persistence, thrift, and loyalty (Hofstede 1991). The primary driving force of this dimension is that an individual, or a society, might give up today’s pleasures for success in the future. In contrast, a short-term orientation tends to place greater emphasis or focus on today’s successes rather than possible successes in the future.

Propositions

The Hunt–Vitell Theory of Ethics (1986, 1993) proposes a number of antecedent constructs to the decision-making process of an individual. These can be classified into five broad categories, namely, the professional environment, the industry environment, the organizational environment, the cultural environment, and personal characteristics. However, only the latter two apply to individual consumer ethics which is the focus of this particular study. Individual characteristics are represented in this study by spirituality and the internalization dimension of moral identity, whereas the cultural environment is most appropriately represented by Hofstede’s five dimensions of culture.

Unfortunately, the H–V theory does not explicate how these antecedent constructs may be related to each other. Therefore, rather than presenting specific hypotheses regarding the role of the five Hofstede dimensions, propositions are put forth wherein the cultural dimensions of the Hofstede typology are expected to moderate both the relationship between (1) spirituality and the ethical predisposition of consumers and the relationship between (2) the internalization of moral identity and the ethical predisposition of consumers. Thus, the specific strength and directional impact of these proposed moderators is not hypothesized.

Spirituality and Consumer Ethical Predisposition

P1

The impact of spirituality on the ethical predispositions of consumers will be moderated by Hofstede’s five cultural dimensions, namely

-

(i)

power distance,

-

(ii)

uncertainty avoidance,

-

(iii)

individualism/collectivism,

-

(iv)

femininity/masculinity and

-

(v)

long-term orientation.

More specifically, Hofstede’s dimensions will moderate the relationships between spirituality and the (a) “actively benefiting,” (b) “passively benefiting,” and (c) “doing good” consumer ethical predispositions.

Internalization and Consumer Ethical Predisposition

P2

The impact of the internalization of moral identity on the ethical predispositions of consumers will be moderated by Hofstede’s five cultural dimensions, namely

-

(i)

power distance,

-

(ii)

uncertainty avoidance,

-

(iii)

individualism/collectivism,

-

(iv)

femininity/masculinity and

-

(v)

long-term orientation.

More specifically, Hofstede’s dimensions will moderate the relationships between the internalization of moral identity and the (a) “actively benefiting,” (b) “passively benefiting,” and (c) “doing good” consumer ethical predispositions.

Methodology

Samples and Procedures

The data were collected with an online survey using existing scales from previous research studies. The questionnaire took approximately 20 min to complete. The scales were presented in the following order: religiosity, spirituality, the Hofstede’s typology, consumer ethics, and moral identity plus general demographic information. The identical items and order were followed in the other versions of this survey as well. However, depending upon the venue, language changes were instituted where needed. While sampling techniques varied somewhat depending upon the cultural venue, the samples, in all cases, were drawn from an essentially young (18–35 years old), well-educated population with a fairly equal gender distribution. Overall, 1052 surveys were completed.

U.S. Sample and Procedures

The U.S. data were collected using a survey administered to participants at a large U.S. Southeastern University using Qualtrics survey software. The makeup of the sample was primarily, but not exclusively, university students from various disciplines. The sample of 376 respondents can be characterized as follows: 65.9 % males and 34.1 % females; 96.8 % of participants were 25 years of age or younger. All except 0.8 % of the sample had completed at least some college, with 78.7 % either having a bachelor degree or being a current undergraduate student; further, 11.8 % were working on a graduate degree, either a master’s degree or a doctorate degree.

French Sample and Procedures

In France, the survey was similarly conducted as an online survey. An e-mail was sent to 210 business students at Aix-Marseille University in the South of France. Potential respondents were directed to a website where they could respond to the survey. The survey was translated to French by an expert fluent in both French and English and back-translated by a second expert fluent in both languages. The two versions were scrutinized for any differences until all differences were resolved. Data were collected over a 3-week period. One hundred and four (104) questionnaires were completed and returned for a 49.5 % response rate. The majority of respondents were graduate students (55.7 %) with the rest being undergraduates. Males comprised 41.3 % of the sample with females comprising 58.7 %; 84.6 % of the sample was below 25 years of age with another 14.4 % being between 26 and 35.

Indian Sample and Procedures

The Indian sample used for the study primarily consisted of young business professionals holding managerial and supervisory positions, again being consistent with the other samples in terms of being a sample of young, well-educated adults. The participants received both e-mail and personal invitations to participate in an online survey. They were informed that the purpose of the study was to understand the decision-making process of individuals in different work situations. As all potential respondents were screened for being highly proficient in English, the English version of the survey, as used in the U.S. study, was the one administered. This survey was identical to the U.S. survey in all respects. As with all versions, the respondents were assured of the confidentiality of their responses. Males made up 46.6 % of the Indian sample with females representing 53.4 %; 56.8 % were less than 25 years of age with another 37.5 % being between 25 and 35. This sample was represented by 25 % having a bachelor’s degree and 71.6 % having a graduate degree.

Spanish Sample and Procedures

The Spanish survey was conducted in three distinct cities in the South of Spain, namely Sevilla, Malaga, and Grenada. All respondents were well-educated, young adult residents of Spain. The survey was translated into Spanish by an expert fluent in both Spanish (Castellano) and English and back-translated by a second expert fluent in both languages. The two versions were scrutinized for any differences until all differences were resolved. Two hundred eighty-seven surveys were completed from a total of 337 for a response rate of 85 %. Again this was primarily a sample of young, well-educated adults as 72.7 % of the sample was under 25 years of age. Undergraduates comprised the majority of the sample with over 80 % of respondents either working on an undergraduate degree or having a bachelor degree in hand while the sample was almost equally divided between males and females with 44.4 % of the respondents being male.

Egyptian Sample and Procedures

A total of 300 questionnaires were distributed in all six districts of the city of Alexandria, Egypt. Of these, 198 were returned, 45 refused to answer the questionnaire, and 67 were returned incomplete (e.g., when the unanswered questions exceeded 10 % of total number of questions). The questionnaires were translated into Arabic by an expert fluent in both languages and then back-translated to English by another expert. The two versions were then scrutinized for any differences until any and all differences were resolved. Again these were primarily young, well-educated adults completing the surveys as seen by the fact that 20.7 % were under 25 and another 35.4 % were between 26 and 35 while 73.2 % were either undergraduate students or had a bachelor degree in hand. The sample was equally divided between males (46.7 %) and females (53.3 %).

Scales

Religiosity and Spirituality

The religiosity scale initially used in the study is by Allport and Ross (1967). Their research has determined that there are two underlying dimensions of religiosity known as intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity. They differentiate the two by noting that (an) “extrinsically motivated person uses his religion, whereas the intrinsically motivated lives his religion” (p. 434, emphasis in the original). However, the extrinsic dimension was not included in the study as it is most often not related to ethics, and the intrinsic dimension was not sufficiently reliable to warrant its inclusion in the final analyses of the study.

Therefore, we now have methodological as well as conceptual arguments for not using a religiosity construct in the study. As explained earlier, the primary religion-oriented construct used in this study is an underrepresented compliment to religiosity, namely, spirituality. Although currently not used in the marketing literature, the authors feel that this construct is viable as an accompaniment, and even superior replacement, to the religiosity construct. This is due in part to intrinsic religiosity’s close tie to spirituality (Ryan and Fiorito, 2003). Intrinsic religiosity is “indicative of having religious commitment and involvement for more inherent, spiritual objectives” (Vitell et al. 2009, p. 158). Thus, while it is different in that someone high in intrinsic religiosity is likely to also be spiritual, an individual could be high in spirituality but not necessarily religious. A sample item from the spirituality scale is “I feel joy when I am in touch with the spiritual side of my life.” The spirituality scale has an overall reliability of 0.904.

Hofstede’s Dimensions

Hofstede defines culture as “the training or refining of one’s mind from social environments in which one grew up” (Hofstede 1991, p. 4). In this study of consumer ethics, we examine social decisions that are influenced by the norms and expectations shaped by a consumer’s culture. AS mentioned, Hofstede identified five specific dimensions by which cultures differ: power distance, uncertainty avoidance, femininity/masculinity, individualism/collectivism, and long-term orientation. This scale encompasses items with statements regarding each specific dimension. Respondents evaluated the statements and responded on a 5-point scale anchored by “strongly agree” and “strongly disagree.”

-

Power Distance Power distance pertains to how power inequality is accepted by people (Hofstede 1991). People with high power distance orientation are comfortable with distinct differences between “superiors” and “subordinates” (Hofstede 1980). Conversely, individuals with a lower power distance orientation view others as equals and feel they have a right to a voice in decision making (Brockner et al. 2001; Tata 2005). A sample item for the power distance scale is, “People in lower positions should not disagree with decisions by people in higher positions.” The power distance scale has an overall reliability of 0.765

-

Uncertainty Avoidance People with a high uncertainty avoidance orientation desire security and appreciate formal rules and standards (Rawwas et al. 2005). They believe it is important to closely follow instructions and procedures. A sample item for uncertainty avoidance is, “It is important to have instructions spelled out in detail so that I always know what I’m expected to do.” The uncertainty avoidance scale has an overall reliability of 0.814.

-

Individualism/Collectivism Collectivists believe that group loyalty should be encouraged even if the individual goals suffer. Individuals who are collectivists value altruism and being helpful more than do non-collectivists, e.g., “individualists” (Torelli and Shavitt 2010). Collectivists are more likely to follow norms, even if they break rules in the process. Alternatively, individualists are more likely to go against norms and to adhere to rules (Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner 1998). A sample item from the collectivism scale is, “Individuals should sacrifice self-interest for the group.” Collectivism has an overall reliability of 0.793.

-

Femininity/Masculinity The femininity/masculinity dimension encompasses the values placed on achievement, assertiveness, and material success by an individual or a society (Hofstede 2010). A sample item of this scale is, “It is more important for men to have a professional career than it is for women.” The reliability of this scale is 0.755.

-

Long-Term Orientation Cultures that characterize a long-term orientation emphasize persistence, thrift, and loyalty (Hofstede 2010). The basic idea is to give up today’s pleasures for success in the future. A sample item for the long-term orientation scale is, “Long-term planning is a necessity for success.” The reliability of this scale is 0.737.

Consumer Ethical Predisposition

In order to gain insights into the ethical perceptions of consumers, Muncy and Vitell (1992) and Vitell and Muncy (1992) created the Consumer Ethics Scale (CES). The initial scale was developed to examine how certain potentially unethical consumer behaviors are viewed by respondents, either as ethical or unethical. Thus, the scale is essentially a measure of a respondent’s consumer ethical predisposition. The initial scale items were based on four constructs of (1) actively benefiting from illegal, (2) passively benefiting from illegal activities, (3) actively benefiting from deceptive (or questionable, but legal) acts, and (4) no harm/no foul activities. The “actively benefiting from deceptive practices” dimension means that the consumer knowingly takes very questionable actions (e.g., drinking a can of soda in the supermarket and not paying for it). This active dimension has an overall reliability of 0.745. Passively benefiting from illegal activities is where the consumer is the passive recipient of some accidental benefit but does not correct the mistake (e.g., not saying anything when you receive too much change from a store clerk). The passive dimension has an overall reliability of 0.785. In 2005, Vitell and Muncy added a “positive” activity dimension, doing good and recycling, to increase the validity of the scale through the addition of an inversely related factor (e.g., buying a more expensive product since it is made from recycled materials). This “doing good” dimension has an overall reliability of 0.713. The actively benefiting from questionable practices and the no harm/no foul dimensions were not used as their reliabilities were too low to allow valid inclusion in the final analyses of the study (i.e., alphas below 0.60) (Table 1).

Moral Identity

Aquino and Reed (2002) introduced moral identity as an explanation for the schema people possess of moral traits that encompass the moral self. Moral identity is composed of two factors, internalization and symbolization. The two dimensions can be likened to religiosity’s dimensions of intrinsic and extrinsic with intrinsic and internalization being similar and extrinsic and symbolization being similar. Individuals vary on how salient or self-important their moral identity personality is (Reed et al. 2007). Additionally, individuals can rank high or low on the specific dimensions. An individual who is high in internalization will feel that possessing “moral” characteristics are a part of their personality, while a person who is high in symbolization will feel that they can convey their characteristics through their actions or other means of portraying themselves to others. To measure moral identity, respondents are given a list of nine characteristics (e.g., caring, hardworking, kind) that they are asked to give answers to internalization and symbolization questions. An example of internalization is “being someone who has these characteristics is an important part of who I am.” The internalization dimension has an overall reliability of 0.651. Symbolization data were not collected for this study as it is not believed to be likely to be correlated with moral beliefs. It is not at all uncommon in studies for only the internalization dimension to be linked to ethically oriented issues (i.e., Vitell et al. 2011).

Results

Hypotheses

To test the hypotheses, regression analyses were used with spirituality and the internalization of moral identity as independent variables and the ethical predisposition of consumers as the dependent variable. Specifically, three dimensions of the consumer ethics scale served as dependent constructs, namely the following (‘‘actively benefiting from illegal activities’’ (Active/Illegal), ‘‘passively benefiting at the expense of others’’ (Passive), and ‘‘doing good’’ (Doing Good). Thus, to test Hypothesis 1, we conducted three separate regression analyses. Table 2 displays the results from these tests. H1 (a) and (b) are supported at a p < .0005 level. These hypotheses stated that individuals higher in terms of their spirituality tend to be more ethically predisposed in that they will be more likely to believe that actively and passively benefitting from illegal activities are wrong. However, H1 (c) was not supported (p = 0.732). This suggests that an individual's level of spirituality does not impact how they evaluate “doing good” consumer activities such as like recycling.

Table 2 also displays the results from testing of H2. How individuals internalize their moral identity was found to be significantly related to all three consumer dimensions of a consumer ethical predisposition (all p’s < .0005), thus providing support for H2 (a), (b), and (c).

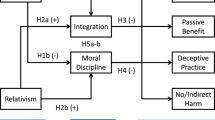

Propositions: Moderation Effects of Hofstede Dimensions

To further understand the relationships between the independent variables, spirituality and internalization, and consumer ethics predisposition, the moderating effect of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions was tested. This allowed the effect of the independent variables to change in intensity and/or direction in accordance with the values of the moderator. Interactions were created individually with each Hofstede dimension and spirituality and then regressed separately on all three consumer ethics dimensions. Haye’s PROCESS macro in SPSS was used to conduct the moderation analyses. The Haye’s PROCESS macro (henceforth PROCESS) is a macro created for SPSS and SAS by Andrew F. Hayes that automates conditional process analysis. Conditional process analysis is used “when one’s research goal is to describe the conditional nature of the mechanism or mechanisms by which a variable transmits its effect on another and testing hypotheses about such contingent effects” (Hayes 2013, p. 10). The benefit of using the PROCESS model is that the macro alleviates the possibility of human error in computation through the use of a “point-and-click” format. By entering the values for the independent variable, the outcome variable, and the moderator, the output provides the conditional and unconditional effects for the proposed model. Our model is the effect of either the internalization of moral identity or spirituality on the CES dimensions moderated by Hofstede’s collectivism, long-term orientation, masculinity, uncertainty avoidance, and power distance dimensions (see Fig. 1).

Spirituality → “Actively Benefiting”

Support was found for Proposition 1 (i and ii) when “actively benefiting” was the consumer ethical predisposition, but only for the cultural dimensions of power distance and uncertainty avoidance. That is, how strongly an individual is in terms of their spirituality interacts with their level of power distance (β = −0.086, p = 0.005) and uncertainty avoidance (β = −0.088, p < .004); thus, apparently the lower one’s scores for the construct of power distance and the less one’s need to avoid uncertainty, the stronger is the consumer ethical predisposition. However, femininity/masculinity, individualism/collectivism, and long-term orientation do not seem to impact either the direction or magnitude of the relationship of spirituality and “actively benefiting.”

Spirituality → “Passively Benefiting”

Partial support was also found for Proposition 1 (ii, iv and v) when “passively benefiting” was the consumer ethical predisposition, but only for the cultural dimensions of uncertainty avoidance, masculinity and long-term orientation. How strongly an individual is in terms of their spirituality interacts with their levels of uncertainty avoidance (β = −0.077, p < 0.023), masculinity (β = −.082, p < .045), and long-term orientation (β = −0.093, p = 0.032) in predicting their evaluation of situations where consumers passively benefit from deceptive acts. Thus, the less one’s need to avoid uncertainty, the less one’s masculinity and the less one’s long-term orientation, the stronger is their consumer ethical predisposition, but power distance and collectivism do not seem to impact either the direction or magnitude of the relationship of spirituality and “passively benefiting.”

Spirituality → “Doing Good”

Finally, in terms of the moderation effect of spirituality, partial support for Proposition 1 (iii and v) was only found for the cultural dimensions of collectivism and long-term orientation. Thus, how strongly an individual is in terms of their spirituality interacts with their levels of collectivism (β = 0.075, p < 0.006) and long-term orientation (β = 0.1104, p = 0.035) in predicting their evaluation of situations where consumers are perceived as “doing good.” In short, the greater the consumer levels of collectivism and long-term orientation, the more likely they are to be predisposed to “do good.”

Internalization → “Actively Benefiting”

Support was found for Proposition 2 (i, ii, iii, iv, and v) when “actively benefiting” was the consumer ethical predisposition. That is, how strongly individuals internalize their moral identity interacts with their level of power distance (β = −0.108, p = 0.002), uncertainty avoidance (β = 0.196, p < 0.0005), collectivism (β = 0.102, p = 0.008), masculinity (β = 0.191, p < 0.0005), and long-term orientation (β = 0.118, p = 0.006) in predicting one’s evaluation of situations where consumers actively benefit from deceptive acts. All of the interaction coefficients were positive, excluding that for power distance. This indicates that the higher the individual scores on the cultural dimensions of uncertainty avoidance, collectivism, masculinity, and long-term orientation, the higher is their ethical consumer predisposition relative to “actively benefitting” from unethical consumer actions. Thus, the higher one’s level of uncertainty avoidance, the more collective, the higher in masculinity and the higher in terms of a long-term orientation, the more ethically predisposed the consumer appears to be. Conversely, power distance has the opposite effect. That is, as individual scores are lower on the power distance scale, the stronger is their consumer ethical predisposition.

Internalization → “Passively Benefiting”

Support was also found for Proposition 2 (i, ii, iii, iv, and v) when “passively benefiting” was the consumer ethical predisposition. That is, how strongly individuals internalize their moral identity interacts with their level of power distance (β = −0.092, p = 0.037), uncertainty avoidance (β = 0.142, p < 0.001), collectivism (β = .116, p = 0.011), masculinity (β = 0.122, p < 0.019), and long-term orientation (β = 0.102, p = 0.046) in predicting their evaluation of situations where consumers passively benefit from deceptive acts. Again, all of the interaction coefficients were positive, excluding that for power distance. This indicates that when an individual scores higher on the cultural dimensions of uncertainty avoidance, collectivism, masculinity, and long-term orientation, the higher is their ethical consumer predisposition relative to “passively benefitting” from unethical consumer actions. This is consistent with the results for actively benefitting activities, indicating that the higher one’s degree of uncertainty avoidance, the more collective, the higher in masculinity, and the higher in terms of a long-term orientation, the more ethically predisposed the consumer appears to be. Conversely, power distance has the opposite effect. That is, the higher the individual scores on the power distance scale, the weaker is their consumer ethical predisposition.

Internalization → “Doing Good”

Finally, partial support was found for Proposition 2 (ii, iii, iv, and v) when “doing good” was the consumer ethical predisposition. The lone exception was that of the power distance dimension. How strongly individuals internalize their moral identity interacts with their level of uncertainty avoidance (β = 0.157, p < 0.0005), collectivism (β = 0.141, p = .0005), masculinity (β = .220, p < 0.0005), and long-term orientation (β = 0.191, p = 0.0005) in predicting their evaluation of situations where consumers “do good.” All relationships were positive so that the stronger one’s need to avoid uncertainty, the more collective, the higher in masculinity and the higher in terms of a long-term orientation, the more ethically predisposed the consumer appears to be. Again, only power distance seems to impact neither the direction nor magnitude of the relationship of internalization and “doing good.” The Moderation Effects of the Hofstede dimensions appear in Table 3.

Discussion

Results indicate that an individual’s spirituality impacts how they view certain questionable consumer activities. Specifically, if the individual tends to be more spiritual, then that person will also have a more positive ethical predisposition. However, spirituality does not seem to have any impact upon “doing good” activities, such as recycling. This does not mean that the individual would not look favorably upon activities such as recycling, only that it is not spirituality which determines this. Regarding moral identity, specifically the internalization dimension, results indicate that moral identity clearly impacts how consumers view not only questionable acts, but also acts of “doing good.” That is, a stronger moral identity in terms of a stronger internal sense of self (i.e., the internalization dimension) tends to mean that the consumer is more ethically predisposed. These results are consistent with what was expected and predicted by the Hunt–Vitell theory of ethics (Hunt and Vitell 1986).

The above two relationships, namely (1) spirituality and consumer ethical predisposition and (2) internalization of one’s moral identity and consumer ethical predisposition were found to be moderated by the dimensions of Hofstede’s cultural typology. However, the impact of these moderators varied depending upon the particular cultural dimension being examined, and whether the independent construct was spirituality or the internalization of moral identity. Furthermore, the impact of these moderators varied for different consumer ethical predispositions. For example, for spirituality power distance was a significant moderator only for the “actively benefiting” activities used to measure consumer ethical predisposition. Uncertainty avoidance, on the other hand, was a significant moderator for the relationship of spirituality with both “actively benefiting” and “passively benefiting” activities. Collectivism only moderated the relationship with “doing good” activities. Finally, masculinity and a long-term orientation moderated the relationships of spirituality with “actively benefiting” and “doing good” activities. What this most likely shows is that while all of the cultural dimensions are to some extent significant moderators as proposed, their significance as a moderator clearly varies depending upon the specific situation, at least where spirituality is the independent construct.

Nevertheless, although not hypothesized, the impact of these moderators was generally mixed. For instance, when power distance is lower, the relationship between spirituality and the consumer’s ethical predisposition for actively benefiting activities is stronger. The interpretation of this result would be that those who believe they are equal, or almost equal, to their superiors in terms of power distribution tend to be more ethical than those who believe there is a significant distance between themselves and their bosses in terms of the distribution of power.

The uncertainty avoidance construct is significant in two of the three instances, but in a direction that may be somewhat unexpected. That is, spirituality was less strongly associated with consumer’s ethical predisposition when uncertainty avoidance was higher for the actively and passively benefiting activities. However, one might expect that when uncertainty avoidance is high for an individual, one might tend to be more ethical as an ethical decision should be less ambiguous and thus more likely to yield uncertainties. Indeed, the correlation between uncertainty avoidance and these two dimensions of consumer ethical predisposition are both significant in a positive direction. Therefore, individuals with high levels of uncertainty avoidance also expressed high levels of ethical predispositions both in terms of actively and passively benefitting from harmful activities regardless of their spirituality levels. However, for individuals with low levels of uncertainty avoidance, there was a strong and positive influence of spirituality on their ethical predispositions along both the active and passive dimensions.

Collectivism seems to strengthen the impact of pirituality on consumers’ ethical predispositions, but only for the “doing good” dimension. Collectivist individuals and cultures prioritize collective good over individual benefit. Therefore, the more collectivistic values an individual has, the more likely the positive ties between one’s spirituality and one’s likelihood to value “doing good.” Perhaps this may be because doing good is the most visible and “positive” ethical dimension of a consumer’s ethical predisposition. One would expect a collectivist society, and thus an individual too, to be more concerned about the impact of individual actions such as recycling on society as a whole. Thus the impact of spirituality on a consumer’s ethical predisposition is strengthened by a collectivist instead of an individualist attitude. Masculinity, on the other hand, might be expected to weaken the relationship between spirituality and consumer ethical predisposition, and indeed this is the relationship that was found for the passively benefiting dimension. This is because a masculine individual prioritizes characteristics such as material success, power, and individual achievements which tend to weaken the positive impact of spirituality on ethical predispositions. Finally, a long-term orientation yielded mixed results as it strengthened the relationship between spirituality and consumer ethical predisposition for the doing good dimension, but weakened that same relationship for the passively benefiting dimension. It seems logical that one with an orientation to the values of the future rather than the present would be more inclined to engage in ethical behavior as one might be able to “get away with questionable behavior” in the short run but in the long run it is much less likely.

In terms of the impact of moral identity on consumer ethical predisposition, and the moderating effect of cultural factors, the results were much more consistent. For example, the internalization dimension of moral identity on consumer ethical predisposition was significantly moderated for all three dimensions by uncertainty avoidance, collectivism, masculinity, and long-term orientation while power distance was significant for two of the dimensions. Additionally, the direction of the moderation was in the same direction for each of the individual cultural factors across all three dimensions of consumer ethical predisposition. More specifically, a higher need to avoid uncertainty strengthens the impact of the internalization of moral identity on ethical predisposition. Thus, the need to avoid uncertainty and ambiguity increases the impact of moral identity on ethical predisposition becomes significantly stronger. The same is true for collectivism for all three dimensions of consumer ethical predisposition as the more collective is the individual in their beliefs, the stronger the impact of moral identity on consumer ethical predisposition. This makes sense as a collectivist would tend to be more likely to consider the impact of their actions on society as a whole, and favor actions such as recycling and treating others in the society more fairly. A strong sense of long-term orientation also strengthens moral identity’s (in the form of the internalization dimension) impact on consumer ethical predisposition. Again this is logical as a long-term orientation means that one is oriented toward virtues consistent with future rewards and less toward immediate gratification.

Masculinity, while significant in all three instances, is significant in that if one is more masculine in their orientation and attitudes, that will tend to strengthen the impact of moral identity on a consumer’s ethical predisposition. However, the opposite relationship might be expected with less masculine individuals being more likely to strengthen the role of moral identity on ethical predispositions. As mentioned above, this would tend to be the case as a more masculine individual tends to put more value in characteristics such as material success, power, and individual achievements which are all more likely to lead to less ethical decision making. Finally, power distance impacts the relationship between moral identity and consumer ethical predisposition by strengthening that relationship when power distance is weaker. That is, when people are less likely to accept the unequal distribution of power, and more likely to question their superiors, then they are more likely to be ethically predisposed.

The findings from this research have implications for explaining how consumers’ ethical predispositions are formed. We found that an individual’s level of spirituality and the strength of their moral identity are important determinants of how they evaluate ethical consumer situations. Moreover, we found that different dimensions of an individual’s culture may strengthen or weaken these relationships. This provides a foundation for understanding how cultural differences in ethical predisposition in various consumer settings may influence one’s ethical decision making.

This study has important implications for marketing managers. We found that individuals who scored high on power distance had a weaker relationship between spirituality and both actively and passively benefiting from unethical situations. Moreover, higher power distance scores weakened the relationship between moral identity and actively benefitting. Companies who operate in countries that rank high on power distance may be more exposed to unethical consumer actions. Care should be taken to minimize the opportunities for consumers to passively or actively benefit from unethical behaviors.

The results have interesting implications for companies targeting consumers with stronger values in the “doing good,” prosocial side of consumer ethics. Surprisingly, consumers who are more spiritual are no more or less likely to positively evaluate consumer activities for “doing good,” like recycling. However, an individual’s sense of moral identity does predict their predisposition for favoring these positive, helpful consumer actions. The results suggest that identifying these types of consumers would be an effective strategy.

The results of this study are not without limitations. The results reported could be due in part to other unaccounted for variables. For example, the samples from each country are not precisely matched in terms of age, education, or gender. Additionally, the sample is predominantly young adults, which limits the generalizability to older populations. However, this could be considered an advantage in gaining insight into a rising group of consumers. Future research should examine how ethical predispositions are formed for older individuals across different countries. Although we did have samples from a diverse collection of countries, more diversity is always desired. Future research should focus on gathering data from a wider range of countries based on Hofstede’s cultural dimensions in order to provide a more comprehensive picture of how different cultures affect consumer’s ethical predispositions.

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationships between (1) spirituality and a consumer’s ethical predisposition, and (2) the internalization of one’s moral identity and a consumer’s ethical predisposition within a cross-cultural context. Furthermore, the moderating impact of cultural factors on the above relationships was tested using Hofstede’s five dimensions. The results proved to be promising since, as predicted, both spirituality and internalization of moral identity impacted a consumer’s ethical predisposition, and Hofstede’s cultural dimensions did significantly moderate these relationships. Hopefully, this will encourage others to continue this line of research and to examine these constructs within the context of other cultures and religions.

References

Allport, G. W. (1950). The individual and his religion: A psychological interpretation. New York: MacMillan.

Allport, G. W., & Ross, J. M. (1967). Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5, 432–443.

Aquino, K., & Reed, A, I. I. (2002). The self importance of moral identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1423–1440.

Auger, P., Devinney, T. M., & Louviere, J. J. (2004). Consumer Social Beliefs: An International Investigation Using Best-Worst Scaling Methodology, unpublished working paper.

Bergman, R. (2004). Caring for the ethical ideal: Nel noddings on moral education. Journal of Moral Education, 33(2), 149–162.

Brockner, J., Ackerman, G., Greenberg, J., Gelfand, M. J., Francesco, A. M., Chen, Z. X., et al. (2001). Culture and procedural justice: The influence of power distance on reactions to voice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 37(4), 300–315.

Davis, R. (1979). Comparison of consumer acceptance of rights and responsibilities. In N. M. Ackerman (Ed.), Proceedings of the 25th Annual Conference of the American Council on Consumer Interests (pp. 68–70). American Council on Consumer Interests.

Detert, J. R., Trevino, J. K., & Sweitzer, V. L. (2008). Moral Disengagement in ethical decision making: A study of antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(2), 374–391.

Donahue, M. J. (1985). Intrinsic and extrinsic religiousness: Review and meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(2), 400–419.

Emmons, R. A. (1999). The psychology of ultimate concerns: Motivation and spirituality in personality. New York: The Guilford Press.

Geyer, A. L., & Baumeister, R. F. (2005). Religion, morality, and self-control. In R. F. Paloutzian & C. L. Park (Eds.), The handbook of religion and spirituality (pp. 412–432). New York: The Guilford Press.

Goldberg, J. R. (2006). Spirituality, religion and secular values: What role in psychotherapy. Family Therapy News, 25, 16–17.

Hardy, S. A. (2006). Identity, reasoning, and emotion: An empirical comparison of three sources of moral motivation. Motivation and Emotion, 30(3), 207–215.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York: Guilford Press.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Motivation, leadership, and organization: Do American theories apply abroad? Organizational Dynamics, 9(1), 42–63.

Hofstede, G. (1983). National cultures in four dimensions: A research-based theory of cultural differences among nations. International Studies of Management & Organization, 13(2), 46–74.

Hofstede, G. (1984). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values (Abridged ed.). Beverly Hills: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (1985). The interaction between national and organizational value systems. Journal of Management Studies, 22(4), 347–357.

Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind, Berkshire. McGraw-Hill Book Company (UK) Limited: England.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. Revised and Expanded 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Huffman, T. E. (1988). In the world but not of the world: Religious, alienation, and philosophy of human nature among Bible College and Liberal Arts College Students, dissertation. Ames, IA: Iowa State University.

Hunt, S. D., & Vitell, S. J. (1986). A general theory of marketing ethics. Journal of Macromarketing, 8(2), 5–16.

Hunt, S. D., & Vitell, S. J. (1993). The general theory of marketing ethics: A retrospective and revision. In N. C. Smith & J. A. Quelch (Eds.), Ethics in marketing (pp. 775–784). Homewood, IL: Irwin Inc.

Jones, T. M. (1991). Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. Academy of Management Review, 16(2), 366–395.

Kluckhohn, F. R., & Strodtbeck, F. L. (1961). Variations in value orientations. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Light, D., Keller, S., & Calhoun, C. (1989). Sociology. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Muncy, J. A., & Vitell, S. J. (1992). Consumer ethics: An investigation of the ethical beliefs of the final consumer. Journal of Business Research, 24(3), 297–311.

Nakata, C., & Sivakumar, K. (1996). National culture and new product development: An integrative review. Journal of Marketing, 60(1), 61–72.

Parsons, T., & Shils, E. A. (1951). Toward a general theory of action. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Polonsky, M. J., Brito, P. Q., Pinto, J., & Higgs-Kleyn, N. (2001). Consumer ethics in the European Union: A comparison of northern and southern views. Journal of Business Ethics, 31(2), 117–130.

Rawwas, M. Y. A., Vitell, S. J., & Al-Khatib, J. (1994). Consumer ethics: The possible effects of terrorism and civil unrest on the ethical values of consumers. Journal of Business Ethics, 13(3), 223–231.

Rawwas, M. Y. A., Ziad, S., & Mine, O. (2005). Consumer ethics: A cross-cultural study of the ethical beliefs of Turkish and American consumers. Journal of Business Ethics, 57(2), 183–195.

Reed, A., Aquino, K., & Levy, E. (2007). Moral identity and judgments of charitable behaviors. Journal of Marketing, 71(1), 178–193.

Ryan, K., & Fiorito, B. (2003). Means-ends spirituality questionnaire: Reliability, validity and relationship to psychological well-being. Review of Religious Research, 45(2), 130–154.

Schwartz, S. H. (1994). Beyond individualism/collectivism: New cultural dimensions of values. London: Sage Publications Inc.

Shao, R., Aquino, Karl, & Freeman, D. (2008). Beyond moral reasoning: A review of moral identity research and its implications for business ethics. Business Ethics Quarterly, 18(4), 513–540.

Tata, J. (2005). The influence of national culture on the perceived fairness of grading procedures: A comparison of the United States and China. The Journal of psychology, 139(5), 401–412.

Tompenaars, F., & Hampden-Turner, C. (1998). Riding the waves of culture: Understanding cultural diversity in business. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Torelli, C. J., & Shavitt, S. (2010). Culture and concepts of power. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(4), 703–723.

Trevino, L. K., Weaver, G. R., & Reynolds, J. S. (2006). Behavioral ethics in organizations: A review. Journal of Management, 32(6), 951–990.

Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism and collectivism. Boulder, CO: Westview Press Inc.

Vitell, S. J. (2009). The role of religiosity in business and consumer ethics: A review of the literature. Journal of Business Ethics, 90(Suppl 2), 155–167.

Vitell, S. J., Bing, M. N., Davison, H. K., Ammeter, T. P., Garner, B. L., & Novicevic, M. M. (2009). Religiosity and moral identity: The mediating role of self-control. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(4), 601–613.

Vitell, S. J., Keith, M., & Mathura, M. (2011). Antecedents to the justification of norm violating behavior among business practitioners. Journal of Business Ethics, 101(1), 163–173.

Vitell, S. J., & Muncy, J. (1992). Consumer ethics: An empirical investigation of factors influencing ethical judgments of the final consumer. Journal of Business Ethics, 11(9), 585–597.

Vitell, S. J., & Muncy, J. (2005). The Muncy–Vitell consumer ethics scale: A modification and application. Journal of Business Ethics, 62(3), 267–275.

Vitell, S. J., & Paolillo, J. G. (2003). Consumer ethics: The role of religiosity. Journal of Business Ethics, 46(2), 151–162.

Vitell, S. J., Paolillo, J. G., & Singh, J. J. (2005). Religiosity and consumer ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 57(2), 175–181.

Walker, L. J., & Pitts, R. C. (1998). Naturalistic conceptions of moral maturity. Developmental Psychology, 34(3), 403–419.

Weaver, G. R. (2006). Virtue in organizations: Moral identity as a foundation for moral agency. Organization Studies, 27(3), 341–368.

Wilkes, R. E. (1978). Fraudulent behavior by consumers. Journal of Marketing, 41(4), 67–75.

De Paulo, P. J. (1987). Ethical perceptions of deceptive bargaining tactics used by salespersons and customers: A double standard. In J. G. Sagert (Ed.), Proceedings of the Division of Consumer Psychology (pp. 201–203). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vitell, S.J., King, R.A., Howie, K. et al. Spirituality, Moral Identity, and Consumer Ethics: A Multi-cultural Study. J Bus Ethics 139, 147–160 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2626-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2626-0