Abstract

Using a large sample of 3,040 U.S. firms and 16,606 firm-year observations over the 1991–2010 period, we find strong evidence that firm internationalization is positively related to the firm’s corporate social responsibility (CSR) rating. This finding persists when we use alternative estimation methods, samples, and proxies for internationalization and when we address endogeneity concerns. We also provide evidence that the positive relation between internationalization and CSR rating holds for a large sample of firms from 44 countries. Finally, we offer novel evidence that firms with extensive foreign subsidiaries in countries with well-functioning political and legal institutions have better CSR ratings. Our findings shed light on the role of internationalization in influencing multinational firms’ CSR activities in the U.S. and around the world.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Reporting on a firm’s corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities has become a mainstream business practice, as indicated by KPMG’s (2013) survey finding that 51 % of reporting companies worldwide include information on corporate responsibility and sustainability in their annual financial reports (compared to 20 % in 2011 and 9 % in 2008). As socially responsible investment has gained prominence, an increasing number of investors factor firms’ CSR activity into their investment decisions (e.g., Scholtens and Sievänen 2013; Sievänen et al. 2013, and references therein). Motivated by the growing attention paid to CSR, which according to McWilliams and Siegel (2001, p. 117) reflects firm actions that “further some social good, beyond the interests of the firm and that which is required by law”, we investigate the extent to which firms’ CSR activities are influenced by corporate internationalization.

In this paper we adopt the strategic view of CSR (Orlitzky et al. 2011), which holds that voluntary CSR actions positively affect primary stakeholders’ interests and the firm’s reputation. While this view suggests that socially responsible behavior is an aspect of firm strategy (Amato and Amato 2012) and an indicator of “long-term firm performance and viability” (Kang 2013, p. 94), it is difficult to measure directly (Carroll 1991). Using Kinder Lydenburg Domini (KLD) data, which are drawn from MSCI ESG Research and are widely used in studies of corporate social performance,Footnote 1 we construct a proxy for CSR activity based on a firm’s engagement in social, ethical, governance, and legal practices (Kang 2013). As a multidimensional construct that captures a firm’s response to various social issues and stakeholder interests (Kang 2013; Kacperczyk 2009), our CSR score is a relevant measure for the purpose of this study for at least two reasons. First, stakeholders’ perception of a firm’s social responsibility draws on all relevant information pertaining to the firm’s social initiatives (Godfrey 2005; Jones 1995, as cited in Brammer et al. 2009).Footnote 2 Second, as we discuss next, firm internationalization also reflects a variety of considerations and stakeholder demands (e.g., Kang 2013).

Firm internationalization is the process “through which a firm expands the sales of its goods or services across the borders of global regions and countries into different geographic locations or markets” (Hitt et al. 2007, p. 251). On a prima facie basis, firm internationalization can be viewed as a strategy to increase a firm’s competitive advantage (e.g., Nachum and Zaheer 2005) and in turn value, through enhanced economies of scale and scope (Kogut 1985), growth opportunities (Porter 1990), and diversification benefits (e.g., Geringer et al. 1989), as well as access to new resources, production capabilities, and knowledge (Hitt et al. 1997). However, firms expanding internationally also face not only the liability of foreignness (Zaheer 1995) and a potentially hostile international environment (Zahra and Garvis 2000), but also increased pressure from an expanded set of stakeholders.

The intensified pressures arising from a larger and culturally, politically, institutionally, and economically more diverse stakeholder environment are likely to induce multinational firms to increase their CSR activities to “demonstrate their responsiveness to a wide range of stakeholders” (Brammer et al. 2009, p. 575, and references therein) and “pursue safe strategic decisions” (Kang 2013, p. 97). Increased visibility through expanded media and analyst coverage might further lead multinational firms to increase their CSR activities to protect the firm’s reputation. Relative to focused firms, multinational firms may also increase their CSR activities to realize greater economies of scope from CSR investment (Kang 2013). Taken together, these arguments suggest that internationalization of corporate activities is positively related to CSR activities. On the other hand, one might argue that the increased diversity and range of stakeholder demands could lead internationally diversified firms to locate in countries with lower CSR standards.Footnote 3

Extant research on firm internationalization has had little to say about the impact of internationalization on a firm’s CSR activities, focusing instead on financial performance effects. This is striking since multinational corporations have often come under attack for being socially irresponsible, as demonstrated, for instance, by protests during the WTO meetings or revelations in the New York Times about Nike’s labor practices in Indonesia. Prior studies that do link firm internationalization and CSR provide mixed evidence. Brammer et al. (2006, 2009), Strike et al. (2006), and Kang (2013) document a positive relationship between internationalization and CSR for samples of U.K. and U.S. firms, while Simerly (1997) and Simerly and Li (2000) do not find a significant link between CSR and firm internationalization for their sample of U.S. firms.

Our study contributes to the above research by using the largest sample to date. For instance, while Brammer et al. (2006, 2009) study a sample of large U.K. firms in 2002, Strike et al. (2006) examine a sample of 222 publicly traded U.S. firms over the 1993–2003 period, and Kang (2013) studies a panel of 511 large U.S. firms over the 1993–2006 period, we examine 3,040 U.S. firms representing 16,606 firm-year observations over the 1991–2010 period. In doing so, we answer Brammer et al.’s (2009, p. 593) call for more research on the link between CSR and internationalization using longitudinal data. In addition, by focusing on firm CSR as a dependent variable, our study contributes to the sparse CSR literature on the determinants of corporate social performance.

To shed light on the effect of firm internationalization on CSR activities, we conduct four sets of tests. First, we examine the association between internationalization and a firm’s aggregate CSR rating. We find that internationalization is significantly positively related to a firm’s CSR rating, consistent with Brammer et al. (2006, 2009) and Kang (2013). In additional analysis we employ alternative measures of internationalization, different subsample periods, and different estimation methods and find that our result is robust. Moreover, our result holds when we use Thomson Reuters ASSET4 and Governance Metrics International (GMI) as alternative sources of CSR data for U.S. firms and when we use a large panel of firms representing 11,077 firm-year observations from 44 countries over the 2002–2010 period. This latter test provides the first multinational evidence on the relation between internationalization and CSR. To address potential endogeneity resulting from the direction of causality between internationalization and its outcomes, we use instrumental variables estimation, propensity score matching, and Heckman sample selection.

Second, delving deeper into the association between internationalization and CSR, we separately investigate the effect of internationalization on the components of firms’ CSR score. When we examine CSR strengths versus concerns, we find that a firm’s internationalization loads significantly (positively) only on CSR strengths. When we examine the impact of internationalization on the individual CSR dimensions, we find that while internationalization loads significantly positively on the Community, Diversity, and Environment dimensions, it loads significantly negatively on the Human Rights dimension. It thus appears that the CSR activities that matter most for multinational firms are those that relate to a firm’s primary stakeholders. However, as suggested by Brammer et al. (2009, p. 579), information regarding an individual CSR dimension “does not enable stakeholders to concretely evaluate the degree to which a firm is socially responsible or irresponsible”.

Third, we investigate whether different institutions across host countries of firm subsidiaries have different effects on multinationals’ CSR activities. We find that multinationals with extensive subsidiaries in countries with strong political and legal institutions have higher CSR ratings. This result goes beyond evidence in earlier studies that diversification is positively related to CSR, and underscores the conditioning role of the institutional environments in which a firm’s subsidiaries operate.

The rest of the article proceeds as follows. In Sect. 2, we review related literature and elaborate on our main hypotheses. In Sect. 3 we describe our data and summarize our research design. We present results in Sect. 4. Finally, we conclude in Sect. 5.

Related Literature and Hypotheses

Given the strategic view of CSR we employ in this study, we expect multinational firms to address increased pressures arising from a larger and culturally, politically, institutionally, and economically more diverse stakeholder environment by integrating them into their CSR activities. Sanders and Carpenter (1998, p. 158) note that as internationalization increases, firm survival increasingly depends on the “ability to cope with the high levels of complexity that derive from heterogeneous cultural, institutional, and competitive environments and the need to coordinate and integrate their geographically dispersed resources”. In particular, firms that expand internationally need to take into consideration the interests and expectations of a wider set of communities, customers, investors, creditors, employees, regulators, and non-government organizations, among other parties (Detomasi 2007).Footnote 4 As a strategic response to the expectations of this more diverse stakeholder base, multinational firms can increase investment in CSR activities to, for instance, reduce the negative environmental impact of their operations and increase employee satisfaction. Thus, from this perspective, one can think of a firm’s CSR score as an indicator of the degree to which a firm responds to its various stakeholder demands (Kacperczyk 2009).

We argue that internationalization drives firms to respond to stakeholder demands through increased CSR activity for several reasons. First, as noted in Kang (2013), internationalization lowers managerial employment risk since multinational firms depend more on manager-specific skills and experience, making it more costly to replace the current management. As a result, managers of such firms are likely to allocate more firm resources to address stakeholder demands (Kacperczyk 2009).

Second, as they enter foreign markets, firms face increased litigation risk from violating (unfamiliar) societal and/or regulatory requirements. Firms can reduce the perceived riskFootnote 5 associated with expanding into foreign markets, and strengthen their reputation as socially responsible actors, by increasing their CSR activities. For instance, Feldman et al. (1997) show that firms that adopt an environmentally proactive posture significantly reduce their perceived risk, and Brammer et al. (2009) argue that the extent to which stakeholders believe that the firm is socially responsible affects stakeholders’ continued involvement with the firm.Footnote 6 In addition, multinational firms can signal their commitment to a foreign market by increasing their CSR activities in the market, which can alleviate communication problems (Zahra et al. 2000) and the adverse effects of psychic distance (Johanson and Vahlne 1977).Footnote 7

Third, internationalization intensifies managerial risk aversion. In seeking to reduce firm risk, managers are likely to avoid “costly problems with regulations, activists and consumers” (Kang 2013, p. 97) by increasing their CSR activities. In addition, because multinational firms are associated with increased analyst coverage and media attention (e.g., Hong and Kacperczyk 2009; El Ghoul et al. 2011), managers are more likely to respond to stakeholder demands to protect the firm’s reputation globally.

While the above arguments favor a positive association between firm internationalization and CSR, alternative arguments suggest that there may exist mitigating factors. For instance, expanding on the pollution haven hypothesis (e.g., Dam and Scholtens 2008), one could argue that multinational firms may locate their production activities in countries or regions with low CSR standards. In this case, one would not expect a relation between CSR and internationalization. Also, as pointed out by Kang (2013), a strong focus on short-term profit maximization rather than long-term performance might crowd out the benefits of investing in CSR, which accrue over the long run, and lead to a weaker relation between CSR and internationalization.

Accordingly, our first and main hypothesis is as follows:

H 1

Internationalization is positively related to a firm’s aggregate CSR score.

Next, we separately examine the extent to which internationalization influences CSR concerns and strengths. This test is useful because aggregating CSR strengths and concerns may overlook cross-sectional variation in CSR behavior (Chatterji et al. 2009).Footnote 8 Strike et al. (2006), for instance, provide evidence that multinational firms are likely to be operating both responsibly and irresponsibly, and thus argue that CSR should be decomposed into its negative and positive aspects (concerns and strengths, respectively). Under the strategic view of internationalization, we expect a positive link between CSR strengths and internationalization. Using the argument of Hart (1995), Attig (2011) stresses that while CSR strengths are proactive in nature and more costly to implement, they are more beneficial than avoiding CSR concerns. This is likely the case because CSR concerns tend to relate to industry standards, or minimum performance levels expected by the public (Block et al. 2013, and references therein). Servaes and Tamayo (2013, p. 1054) similarly hold that CSR strengths should matter more than concerns when capturing firms’ CSR activities, arguing that CSR concerns are likely the outcome of decisions other than a firm’s specific CSR efforts. Supportive evidence is provided by Kim et al. (2012), who show that CSR strengths (concerns) are associated with more conservative (aggressive) financial reporting. Based on these arguments, our second hypothesis is as follows:

H 2a

Internationalization is positively related to a firm’s CSR strengths

H 2b

Internationalization is negatively or not related to a firm’s CSR concerns.

Following similar arguments as above, using an aggregate CSR score might also mask variation in the relevance of its component dimensions (Griffin and Mahon 1997; Attig 2011; Galema et al. 2008). Hillman and Keim (2001) distinguish two main groups of CSR components: those related to a firm’s primary stakeholders (e.g., Employee Relations, Diversity, Product Characteristics, Community, and Environment) and those that reflect participation in social issues and are not directly related to a firm’s primary stakeholders (e.g., Human Rights). Given the importance of investing in relationships with primary stakeholders to maintain their involvement in the company’s business activities and thus increase the firm’s competitive advantage (Hillman and Keim 2001), we expect internationalization to have a greater effect on the CSR dimensions related to the firm’s primary stakeholders. In contrast, internationalization may have little or no impact on the aspects of social performance that reflect participation in social issues, because, all else being equal, they are less likely to influence stakeholders’ involvement in the firm’s activities. Our third hypothesis is thus as follows:

H 3

Internationalization is positively related to the CSR dimensions related to the interests of the firm’s primary stakeholders.

To shed further light on the relevance of internationalization in shaping multinational firms’ CSR activities, we investigate the extent to which host-country institutions affect the CSR activity of multinational firms. Murtha and Lenway (1994) suggest that national institutional factors exert great influence on a firm’s non-market behavior and strategies. While empirical research offering convincing support for the impact of institutional and legal factors on corporate outcomes (e.g., La Porta et al. 1998) is abundant, in work more closely related to this study Ioannou and Serafeim (2012) find that country (e.g., political and legal) institutions are important determinants of social and environmental performance. In addition, Dam and Scholtens (2007) conclude that cultural values are an important determinant of international differences in ethical policies. Building on this stream of research, we posit that multinational firms’ CSR activities vary across institutional environments. To test this prediction, we examine whether variation in political risk, government stability, investment profile, control of corruption, law-and-order rating, democratic accountability, and quality of bureaucracy across a firm’s foreign subsidiaries affects the firm’s CSR score. Accordingly, our fourth hypothesis is as follows:

H 4

The institutional environment of a multinational firm’s host countries conditions the link between firm internationalization and its CSR score.

Data and Research Design

Sample Selection

Our sample of U.S. firms comes from two databases: Compustat, which we use to obtain financial information and construct our internationalization variables, and MSCI ESG STATS, which we use to obtain CSR scores.Footnote 9 MSCI ESG STATS, together with its predecessor KLD Stats, is widely used in CSR studies (e.g., Hillman and Keim 2001; Chatterji et al. 2009; Servaes and Tamayo 2013; Kang 2013).

To construct our sample, we begin with all firms from Compustat over the 1991–2010 period with non-missing financial information. We then eliminate financial firms (SIC codes between 6000 and 6999) because they are regulated entities and firm-years for which the sum of geographic segment sales is not within 1 % of total reported firm sales. Next, we match our Compustat sample with MSCI ESG STATS, which evaluates each firm along 13 CSR dimensions using surveys, financial statement information, media reports, government documents, regulatory filings, proxy statements, and peer-reviewed legal journals. These 13 CSR dimensions are grouped into two major categories: qualitative issue areas and controversial business issues. Qualitative issue areas are Community, Corporate Governance, Diversity, Employee Relations, Environment, Human Rights, and Product Characteristics. For each area, we calculate a score equal to the number of strengths minus the number of concerns. We then sum the scores to obtain an overall CSR score (CSR_S).Footnote 10 This approach, which is commonly used in the CSR literature (e.g., El Ghoul et al. 2011; Goss and Roberts 2011; Kim et al. 2012), is relevant for this study because, as a multidimensional construct, CSR_S may capture multinational firms’ strategic response to stakeholder demands and social issues (Kang 2013).

After applying the above screens, our final sample contains 3,040 U.S. firms and 16,606 firm-year observations over the 1991–2010 period. Appendix 1 provides details on the construction of the CSR variables. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the CSR data by year. As can be seen from Panel A, the number of firms per year is fairly evenly distributed around the 300 range over the 1991–2000 period, increasing to the 500 range in 2001 and 2002 before rising dramatically to between 1,300 and 1,800 firms per year over the 2003–2010 period. The increase in the number of firms per year is largely due to increased sample coverage. In particular, firm coverage in MSCI ESG STATS has increased steadily over time. In 1991–2000, coverage consisted of the S&P 500 and the Domini Social Index. The Russell 1000 Index was added in 2001, the Large Cap Social Index in 2002, and both the Russell 2000 Index and the Broad Market Social Index in 2003. Panel A of Table 1 also reports summary statistics for our aggregate CSR measure by year. The mean CSR score declines to become negative in 2004, and remains negative until the end of our sample. The sharp decline corresponds to the number of observations more than doubling in 2003 due to the inclusion of a broader sample of firms in the database.Footnote 11 The median also becomes negative in 2005 and remains so until 2010. Panel B of Table 1 shows that in the 2004–2010 period, the average number of strengths (CSR_STR) increased at a slower rate than the average number of concerns (CSR_CON). As a result of these two trends, the overall mean CSR score declined during this period.

Regression Models and Variables

To analyze the impact of firm internationalization on CSR, we run variations of the following model (Strike et al. 2006; Brammer et al. 2006; Barnea and Rubin 2010; Kang 2013):

where CSR_S is the firm’s aggregate CSR score.

INTERNATIONALIZATION is one of several proxies for firm internationalization. Our main proxy is the ratio of foreign sales to total sales (FS/S), where foreign sales is the sum of sales of all foreign segments (e.g., Li et al. 2011). Sullivan (1994) observes that FS/S is the most commonly used measure of internationalization, consistent with the idea that “a company’s foreign sales are a meaningful first-order indicator of its involvement in international business” (p. 331). Financial information on U.S. firms’ geographic segments is available in the Compustat Segments file. Purely domestic firms report one segment, while multinational firms report one domestic segment and at least one foreign segment corresponding to a foreign country or region. We use Compustat variable Geographic Segment Type (GEOTP) to identify domestic (GEOTP = 2) and foreign (GEOTP = 3) segments.

As alternative measures of firm internationalization, we first use foreign assets to total assets (FA/A). In comparing FS/S and FA/A, Sanders and Carpenter (1998) explain that the foreign sales ratio reflects a firm’s sales to foreign markets while the foreign assets ratio reflects a firm’s foreign stock holdings. According to the authors (p. 166), the sales and asset dimensions capture the overall dependence of a firm on foreign consumer markets and foreign resources, respectively. We also use the sales Herfindahl index (Black et al. 2014) and entropy index (Hitt et al. 1997). Specifically, for a firm with N geographic segments,

where s i is the sales of geographic segment i.Footnote 12 Finally, we construct asset-based Herfindahl (HERFINDAHL_A) and entropy (ENTROPY_A) indexes. We note that we have fewer observations on the three asset-based measures of internationalization because some firms do not report information on their foreign segments’ assets.

\( FIXED\,EFFECTS \) comprises time and industry fixed effects. Z is a vector of control variables. We lag the right-hand-side variables by one period to attenuate endogeneity (i.e., simultaneity between CSR and the right-hand-side variables). We control for the logarithm of total sales (SIZE) and the logarithm of firm age (LOG_AGE) because large and older firms are more visible, and thus face more pressures from their stakeholders to behave in a socially responsible way (Brammer et al. 2009). Firm age is the number of months since the firm first appeared in the CRSP database. We also include profitability, measured as the ratio of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) to total assets (ROA), and leverage, measured as the ratio of total debt to total assets (LEV), to capture slack resources because Waddock and Graves (1997) predict that firms with more slack resources invest more in CSR (i.e., slack resources hypothesis). We further follow Kang (2013) and include the market-to-book ratio (MTB) because intangible assets may affect CSR. The market-to-book ratio is the ratio of the market value of assets to the book value of assets, where the market value of assets is given by market capitalization (number of shares outstanding × share price) minus the book value of equity plus the book value of assets. In addition, McWilliams and Siegel (2001) argue that firms with differentiated products need to invest more in CSR, and thus we include research and development intensity measured as the ratio of research and development expenses to total sales (R&D/S) to capture product differentiation.Footnote 13 McWilliams and Siegel (2001) also argue that the need to make consumers aware of CSR attributes creates a positive relationship between advertising, which is measured using the ratio of advertising expenses to total sales (ADV/S), and CSR.Footnote 14 Finally, Brammer et al. (2009) argue that CSR activities might reflect agency costs. Following their approach, we include long-term institutional ownership (LTIO) because previous research shows that long-term institutional investors play a role in corporate governance (e.g., Attig et al. 2013a). More detailed variable definitions are provided in Appendix 2.

Panel A of Table 2 provides summary statistics for the key variables used in our regression analysis. Panel B presents a correlation matrix for these variables. Of particular relevance to our study is the positive and significant (at the 1 % level) correlation between CSR (CSR_S) and internationalization (FS/S). Generally, the pairwise correlation coefficients among the control variables are low, suggesting that multicollinearity is not of concern in our analysis.

Empirical Evidence

Effects of Internationalization on a Firm’s CSR Score

Main Evidence

Table 3 reports the results of estimating Eq. (1) using ordinary least squares (OLS), with standard errors corrected for heteroskedasticity and clustering by firm to account for the lack of independence of observations within a given firm over time. In Model 1 we regress the aggregate CSR score (CSR_S) on the ratio of foreign sales to total sales (FS/S)—our main proxy for firm internationalization—and a set of controls. We find support for our hypothesis on the internationalization-CSR link: the estimated coefficient on FS/S is positive and statistically significant (at the 1 % level). This result is consistent with Strike et al. (2006) and Kang (2013), and suggests that CSR activities can help firms mitigate market imperfections and asymmetric information problems as well as manage complexities stemming from an expanded set of stakeholders.

Next, we assess whether the importance of internationalization to CSR activities varies systematically with firm size. All else being equal, large firms are better able to cope with the increased complexity and uncertainty of internationally diversified operations than small firms because their more diverse activities and more abundant resources help them exploit economies of scale (e.g., Fatemi 1984; Gaba et al. 2002). Kirca et al. (2012, p. 509) argue that the benefits of scale are more pronounced for larger firms because they have access “to privileged learning channels, they can reduce risk through wider portfolios, and they have stronger bargaining power to gain concessions from host country institutions and governments”. Not surprisingly, therefore, in Model 2 of Table 3 we find that the positive impact of internationalization on CSR is more pronounced for large firms: the estimated coefficient on the interaction between FS/S and SIZE is positive and significant at the 1 % level.Footnote 15 Thus, the societal implications of internationalization appear to concentrate among large firms.

To provide further support to our main result on the impact of internationalization on CSR, we conduct a series of additional tests. We first replace FS/S with alternative measures of firm internationalization. In particular, we use the ratio of foreign assets to total assets (FA/A) in Model 3, the sales- and assets-based Herfindahl index measures of geographical diversification (HERFINDAHL_S and HERFINDAHL_A) in Models 4 and 5, and the sales- and assets-based entropy index measures of geographical diversification (ENTROPY_S and ENTROPY_A) in Models 6 and 7, respectively. In line with our finding in Model 1, the results consistently imply that firm internationalization is significantly positively related to CSR_S, providing further support for the prediction of our first hypothesis (H 1 ) that firm internationalization increases CSR engagement.

Next, we employ alternative proxies for CSR.Footnote 16 Recall that a composite proxy for CSR is suitable for the purpose of our study given that firm internationalization leads to a larger and more diverse set of stakeholders. Following the mainstream approach in the literature (e.g., El Ghoul et al. 2011; Attig et al. 2013a, b; Attig et al. 2014; and Kim et al. 2012, 2014), we construct our composite CSR score by subtracting the number of concerns from the number of strengths across all qualitative issue areas. However, this approach could be challenged on the grounds that it assigns subjective (equal) weighting to the various components of the CSR measure. To address this concern, we perform principal component analysis on the qualitative issue area scores and retain the first principal component (PFC_CSR_S). This alternative approach of aggregating the qualitative issue area scores has the advantage of letting the data determine the appropriate weights on the CSR dimensions. The results reported in Model 8 of Table 3 further support our main finding that internationalization (FS/S) is associated with an increase in socially responsible initiatives (PFC_CSR_S).

We also consider two alternative proxies for CSR that are robust to methodological changes adopted by MSCI ESG STATS (such as covering different sets of strengths and concerns over time; see Kim et al. 2014). The first proxy, CSR_S1, is given by (CSR_S for firm i in year t − Min CSR_S in year t)/(Max CSR_S in year t − Min CSR_S in year t). This proxy ranges from zero to one and therefore is comparable over time. The second proxy, CSR_S2, is given by (CSR_S for firm i in year t − Min CSR_S in firm’s i industry in year t)/(Max CSR_S in firm’s i industry in year t − Min CSR_S in firm’s i industry in year t). This proxy also ranges from zero to one but has the additional advantage of adjusting the CSR score by industry. We re-estimate our baseline regression after replacing CSR_S with CSR_S1 and CSR_S2 in Models 9 and 10, respectively. The results show that internationalization is positively and significantly related to these alternative CSR proxies. Therefore, we rule out the possibility that MSCI ESG STATS’s changing methodology over time affects our results.

In a final set of additional tests, we employ CSR scores obtained from Thomson Reuters, namely, ASSET4 (CSR_A4) and GMI Ratings (CSR_GMI). The results are reported in Models 11 and 12 of Table 3. Despite the sharp drop in the number of observations in this analysis (3,039 observations for CSR_A4 and 6,281 observations for CSR_GMI), we find that the estimated coefficient on FS/S bears significantly positively on CSR activity. Overall, the results in Table 3 lend support to H 1 , which predicts that internationalization is positively related to firms’ CSR activities.

Turning to the control variables, several significant relations emerge from Table 3. The estimated coefficients on size (SIZE), profitability (ROA), market-to-book (MTB), R&D intensity (RD/S), advertising expenses (ADV/S), and long-term institutional ownership (LTIO) are generally positive and statistically significant, suggesting that they increase CSR ratings.Footnote 17 Firm leverage (LEV), however, loads significantly negatively on CSR_S, suggesting that an increase in leverage leads to a lower CSR rating. All these relations are consistent with expectations.

In Table 4, we examine the stability of the internationalization-CSR relation over time. To do so we re-estimate Eq. (1) over four consecutive five-year subsample periods: 1991–1995 (Model 1), 1996–2000 (Model 2), 2001–2005 (Model 3), and 2006–2010 (Model 4). During the 1991–1995 period, the coefficient on FS/S is positive but statistically insignificant at conventional levels. In contrast, the coefficient on FS/S in the three other subsample periods loads significantly positively. While it is possible that the internationalization-CSR link can be time-dependent, the data in Table 4 support our prediction on the role of internationalization in influencing firms’ CSR activities.

Recall that KLD, the predecessor of MSCI ESG, dramatically increased its coverage in 2003, with the number of observations jumping from 522 in 2002 to 1,370 in 2003 and increasing steadily thereafter. To assess the impact of the increased coverage on our results, we split the sample period into two subperiods: 1991–2002 and 2003–2010. We present regression results for these two subperiods in Models 5 and 6 of Table 4. We find that the coefficient on FS/S is positive and statistically significant over both subperiods.Footnote 18 However, the coefficient on FS/S is more statistically significant for the 2003–2010 period (1 %) than the 1991–2002 period (10 %).Footnote 19 This might be due to statistical power, as the 2003–2010 period has approximately three times the observations of the 1991–2002 period.

In Table 5 we use two alternative estimation methods. First, we exploit the panel nature of our data by estimating fixed and random effects models. In results reported in Models 1 and 2, we continue to find that internationalization is significantly positively related to a firm’s CSR score. These regressions help dispel concerns that omitted variables and unobserved heterogeneity drive our main finding. Second, following Petersen (2009) and Gow et al. (2010), we use different estimation methods to control for cross-sectional and serial dependence, namely, Newey–West in Model 3, Fama–MacBeth in Model 4, Prais-Winsten in Model 5, and two-way clustering by firm and year in Model 6 of Table 5. Importantly, the estimated coefficient on FS/S loads significantly positively on CSR in each of these regressions, indicating that our main evidence on the positive association between CSR and internationalization is unaffected by the use of different estimation methods.

To reinforce the validity of our findings, in Table 6 we provide out-of-sample evidence on the relationship between CSR and internationalization. Specifically, we use Thomson Reuters ASSET4 as an alternative source of CSR data to extend our sample to firms from 44 countries over the 2002–2010 period. Panel A of Table 6 presents the distribution of the sample by country and year. The U.S., Japan, and the U.K. are the most represented countries with 37, 13, and 12 % of the sample observations, respectively, and the number of observations increases steadily over the sample period, from in 519 in 2002 to 1,869 in 2010. Regression results are reported in Panel B of Table 6, with country effects reported in Appendix 4. We find that the estimated coefficient on FS/S bears significantly positively on the ASSET4 measure of CSR activity.Footnote 20 The results in Table 6 therefore reinforce our main evidence in Table 4 on the positive relation between internationalization and firms’ CSR activities.

Endogeneity

Although our results on the internationalization-CSR relationship are insightful, they should be interpreted with caution because we cannot rule out alternative explanations. For instance, reverse causality might be an issue since CSR as an organizational resource may help firms expand internationally. In addition, self-selection into socially responsible behavior might arise as the firm’s stance on such behavior is not a random decision. To mitigate concerns of endogeneity we use three approaches, reported in Table 7.

First, in Panel A we implement an instrumental variable (IV) estimation procedure where we use three instruments to extract the exogenous component of FS/S, following Li et al. (2011). The first instrument is MID, a dummy variable set to one if the firm reports minority interest on its balance sheet. A firm carries minority interest on its balance sheet if it acquired majority stakes in other firms. To the extent that firms internationalize using foreign acquisitions, MID should be correlated with international diversification. However, since minority interest reflects past acquisitions, MID is unlikely to be directly related to contemporaneous CSR. The second instrument is PNFOR, the fraction of firms with foreign sales in the firm’s industry in a given year. A higher fraction of internationally diversified firms in the same industry indicates significant demand for the industry’s products abroad. This should encourage firms in the same industry to internationalize. However, it is not clear why a higher fraction of internationally diversified firms would be directly related to a particular firm’s CSR activities. The third instrument is STATE_FS/S, the ratio of foreign sales of all firms headquartered in the state to foreign sales of all sample firms in a given year. A firm might benefit from the international experiences of neighboring firms. Therefore, higher foreign sales by firms in the same state should be correlated with firm internationalization, but there are no theoretical reasons to believe that it should also be correlated with CSR. We regress FS/S on the three instruments and all the controls in Eq. (1). Results of this first-step regression are reported in Model 1. We then retain the predicted value of FS/S and use it instead of FS/S in the regressions examining the effect of internationalization on CSR. We use two-stage least-squares (2SLS), limited information maximum likelihood (LIML), and generalized method of moments (GMM) estimations, respectively, in Models 2, 3, and 4. The results reported in Model 1 suggest that the three instrumental variables are significantly positively related to our internationalization proxy (FS/S). Importantly, the second-stage regressions results in Models 2 through 4 consistently show that the impact of the predicted value of FS/S is positive and statistically significant at the 5 % level, reinforcing our OLS findings in Table 4.

Second, in Panel B of Table 7 we employ the propensity score matching (PSM) procedure proposed by Rosenbaum and Rubin (1983). To implement PSM we start by constructing a multinational dummy variable that takes the value of one if FS/S > 0, and zero otherwise. We then estimate a probit model where we regress the multinational dummy on all controls, and we use the scores to match (using different approaches) each observation with multinational dummy = 1 to an observation with multinational dummy = 0. We use the resulting sample in our regression. Interestingly, our key variable (multinational dummy) loads significantly positively on CSR independent of the matching method used, lending further support to our main finding that internationalization is associated with a higher CSR score. As such, CSR seems to play a non-negligible strategic role in reducing market imperfections and managing the complexity arising from expanding into new international markets.

Third, in Panel C of Table 7 we employ the Heckman self-selection (two-step) model. In the first step, we use a probit model to regress the multinational dummy on all control variables from our main specification (Column 1 in Table 4) and the instrumental variables used in Panel A of Table 7 (MID, PNFOR, and STATE_FS/S). In the second stage, the firm’s overall CSR score (CSR_S) is the dependent variable, and we include the self-selection parameter (inverse Mills’ ratio) estimated from the first stage. The results of the two-step estimation model continue to suggest that internationalization is positively associated with a higher CSR score.

Effects of Internationalization on the Components of a Firm’s CSR Score

To test our second and third hypotheses, we examine the link between internationalization and different dimensions of the overall CSR score. In Models 1 and 2 of Table 8, we test the effect of internationalization on CSR strengths (CSR_STR) and concerns (CSR_CON), respectively. In line with our second hypothesis (H 2 ), we find that the estimated coefficient on FS/S loads significantly positively on CSR strengths (CSR_STR), while it does not have a significant effect on CSR concerns (CSR_CON).Footnote 21 This evidence suggests that internationalization increases CSR strengths, but has no effect on CSR concerns. This result provides only partial support for Strike et al. (2006), who find a positive relationship between firm internationalization and both responsible and irresponsible corporate behavior. A potential explanation for the different results is that as firms expand the geographical scope of their operations, they invest proactively in CSR strengths, as doing so enhances the firm’s reputation and in turn its competitive advantage. In contrast, firms are unlikely to devote effort to avoiding CSR concerns (Servaes and Tamayo 2013), as doing so is usually achieved by complying with minimum industry standards.

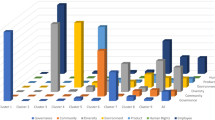

Next, we examine the effects of internationalization on the individual CSR dimensions. Specifically, we look at the following six attributes included in the CSR score: Community (CSR_COM_S) in Model 3, Diversity (CSR_DIV_S) in Model 4, Employee Relations (CSR_EMP_S) in Model 5, Environment (CSR_ENV_S) in Model 6, Human Rights (CSR_HUM_S) in Model 7, and Product Characteristics (CSR_PRO_S) in Model 8. The results suggest that the effects of internationalization vary across the six CSR dimensions. Internationalization loads significantly negatively on the dimension Human Rights (CSR_HUM_S). In contrast, internationalization loads significantly positively on the CSR dimensions related to the firm’s primary stakeholders, that is, Community (CSR_COM_S), Diversity (CSR_DIV_S), and Environment (CSR_ENV_S). Firm internationalization does not have a significant effect on the dimensions Employee Relations (CSR_EMP_S) and Product Characteristics (CSR_PRO_S). Overall, these findings provide some support to the evidence in Brammer et al. (2006) that, for a sample of U.K. firms in 2002, geographical diversification has a positive relationship with the CSR dimensions Community and Environment but no relationship with the Employee Relations dimension.

Taken together, the findings in Table 8 are largely consistent with our third hypothesis (H 3 ). The positive and significant links between internationalization and the dimensions Community, Diversity, and Environment lend weight to the finding of Hillman and Keim (2001) that the relevant CSR dimensions are those directly related to firms’ primary stakeholders. Stated differently, our evidence suggests that to address the complexities of internationalization, multinational firms try to meet their various primary stakeholders’ expectations in regard to corporate social performance. In contrast, the significant negative link between internationalization and a dimension that reflects the firm’s participation in social issues (i.e., Human Rights) suggests that firms entering foreign markets do not invest in social issues, perhaps because multinational firms do not realize competitive advantage benefits from doing so.Footnote 22 Similarly, internationalization does not appear to bear on the product and employee CSR dimensions, which are determined to a large extent by competitive pressures and legal, regulatory, and/or industry standards and have a more direct impact on multinational firms’ financial performance. For instance, employee relations, as revealed by organizational practices designed to enhance employee skills and involvement (e.g., profit-sharing program, employee stock option plans, safety programs, promotions, training, and succession planning), likely lead to a more competitive and productive workforce and thus more productivity gains and better performance (e.g., Whitener 2001; Collins and Smith 2006). Similarly, product characteristics, which tend to reflect, among other things, a firm’s long-term investment in quality, R&D/innovation, and product safety are typically determined by the industry-competitive pressures and standards (e.g., product technology and social benefits).

It is worth reiterating, however, that the evidence for the relationship between internationalization and the individual dimensions of CSR should be interpreted with caution because, as suggested by Brammer et al. (2009, p. 579), information regarding an individual component of CSR “does not enable stakeholders to concretely evaluate the degree to which a firm is socially responsible or irresponsible”.

Impact of the Institutional Environment on a Firm’s CSR Score

To test our fourth hypothesis (H 4 ), we analyze the extent to which a U.S. multinational firm’s CSR score is affected by the institutional environment of its foreign subsidiaries’ host countries. To do so we analyze the subsample of U.S. firms that disclose subsidiaries in Exhibit 21 of Form 10-K and control for a set of institutional variables obtained from International Country Risk Guide. For each institutional variable, we follow Dyreng et al. (2012) and compute the weighted average institutional rating of countries in which the firm discloses subsidiaries.Footnote 23 The results are reported in Table 9.

In Model 1 we examine whether variation in the local political risk rating that applies to foreign subsidiaries affects the U.S. parent. The estimated coefficient on POLIT_RISK is positive and significant at the 1 % level, suggesting that, all else being equal, diversification into countries with more political stability is associated with a higher CSR score. The estimated coefficient on the weighted average government stability rating of countries in which the firm discloses subsidiaries (GOVT_STAB), as shown in Model 2, is also positive and significant, indicating that diversification into countries with more stable governments is associated with more socially responsible behavior by U.S. firms and thus a higher CSR score. In Models 3–7 of Table 9 we compute the weighted average of, respectively, the government’s investment profile rating, control of corruption rating, law-and-order rating, democratic accountability rating, and quality of bureaucracy rating. Interestingly, the estimated coefficient on each of these factors loads significantly positively on the CSR score, providing evidence that multinational firms with subsidiaries in countries with strong legal and political institutions are associated with a higher CSR score. Moreover, the effect on CSR of our key variable (FS/S) continues to hold, lending further weight to our main finding on the societal implications of firm internationalization.Footnote 24

In sum, the evidence reported in Table 9 supports our fourth hypothesis (H 4 ). Taken together, our novel evidence on the firm-level CSR implications of the institutional environments in which a firm’s subsidiaries are located complements Ioannou and Serafeim’s (2012) findings that country institutions are important determinants of firms’ social and environmental performance. Similarly, the evidence of Table 9 lends support to the pollution haven hypothesis, which holds that firms that pollute more locate in countries with lax environmental regulations (e.g., Dam and Scholtens 2008).

Conclusion

In this paper, we shed new light on the determinants of corporate social performance by investigating the extent to which CSR activities are affected by the degree of internationalization of firms.

Using a sample of 3,040 U.S. firms representing 16,606 firm-year observations over the 1991–2010 period, we find that internationalization exerts a significant and positive effect on CSR activity. We also find that internationalization loads significantly (positively) on CSR strengths but not on CSR concerns, and that internationalization bears significantly only on those CSR dimensions that are discretionary in nature and less likely to be determined by societal and legal requirements. We further find that only large multinational firms with more abundant resources increase their CSR investments in response to their internationalization. Finally, we provide new evidence that multinational firms with subsidiaries in countries with strong institutional environments and strong legal and political institutions are associated with higher CSR ratings. In sum, our findings support the view that firm internationalization is associated with increased CSR activity, suggesting that the importance of responding to stakeholder demands increases with the degree of internationalization.

In additional analysis based on a sample of representing 11,077 firm-year observations from 44 countries over the 2002–2010 period, we go beyond Brammer et al. (2009) and more recently Kang (2013) by providing evidence on the link between internationalization and CSR in an international context. Furthermore, we expand previous literature by relating internationalization to the different components of CSR, rather than examining the outcomes of these components on firm performance, financing costs, and credit ratings. Moreover, we fill a gap in extant literature by showing how different institutional and legal environments affect the relation between internationalization and CSR.

Two caveats are in order. First, our main proxy for a firm’s CSR activities comes from KLD’s binary ratings of corporate social activity. These ratings do not distinguish the extent of CSR activity within each component area (Barnea and Rubin 2010). Our proxies for a firm’s corporate social performance are thus noisy indicators of a firm’s actual CSR behavior (Ioannou and Serafeim 2012). Second, although we employ commonly used measures of internationalization, we acknowledge that these unidimensional measures may not be ideal as suggested by Sullivan (1994).

The findings of this study invite researchers to explore the implications of the internationalization-CSR link on other corporate outcomes, while taking into account the institutional and political environments in which subsidiaries of multinational firms operate. Future research may also seek to improve our understanding of how social responsibility standards of host countries affect the CSR behavior of multinational firms. In addition, it would be interesting to test the possibility that firms could expand internationally to integrate a larger set of stakeholders’ interests, suggesting that firms that want to behave responsibly will likely aim for cross-border growth and diversification. Finally, following Sullivan’s suggestion (1994), future research should work toward identifying a broad construct that reflects the multiple dimensions of internationalization.

Notes

Thus, weakness on one dimension may be offset by strength in another dimension (Janney and Gove 2011).

Research that investigates the extent to which firms locate their business activities in countries or regions with lax corporate social standards, and in particular environmental standards, finds support for the pollution haven hypothesis, suggesting that firms tend to transfer their “dirty operations to countries with weak environmental regulation” (Dam and Scholtens 2008, p. 55).

A higher degree of internationalization exposes the firm to a proportionally wider range of demands/constraints stemming from a diversified pool of stakeholders that includes foreign customers (interested in products and services’ characteristics), governments and regulators (via taxation and regulatory compliance), foreign suppliers, employees (concerned about work ethics, work conditions, recognition and retention), environmentalists, communities, etc.

Using survey data from 172 ISO-certified firms in China, Christmann and Taylor (2001) show that the implementation of environmental standards by foreign firms depends not only on the degree of internationalization, but also on customer monitoring and sanctions (e.g., termination of the relationship).

Psychic distance refers to the uncertainty associated with factors such as “differences in language, culture, political systems, level of education, or level of industrial development” that adversely affect the flow of information between a firm and the market (Johanson and Vahlne 1977, p. 24).

As Kim et al. (2012, p. 784) state, “a firm with five strengths and five concerns is surely different from a firm with one strength and one concern”.

An advantage of the U.S. setting relative to the international setting is the availability of sophisticated measures of international diversification such as the Herfindahl and entropy indexes. Using these variables as alternatives to our primary measure of firm internationalization, the foreign sales ratio, allows us to verify the robustness of our finding on the link between CSR and internationalization. Notwithstanding, we complement our results based on a U.S. sample with the first multinational evidence on the relation between international diversification and CSR using a large panel of non-U.S. firms from 43 different countries. Using non-U.S. firms thus provides out-of-sample evidence on the impact of international diversification on CSR around the world.

Similar to Kim et al. (2014) and Krüger (2014), among others, we view corporate governance as a different construct than CSR. For instance, a well-governed firm could have a bad CSR record by maximizing shareholders’ wealth at the expense of its stakeholders (e.g., employees, environment, community) in the sense of Friedman (1970). Nonetheless, in unreported tests we find similar results irrespective of whether corporate governance is included in or excluded from our CSR score.

To assess the impact of the increased sample coverage, we identify 20 firms that were in the sample for the entire period. In untabulated results, we find that the CSR score for these firms did not change dramatically after 2003. Indeed, the average CSR_S went from 1.7 in 2003 to 1.6 in 2003 and steadily increased thereafter.

The Herfindahl index equals one and the entropy index equals zero for purely domestic (i.e., single-segment) firms.

This ratio is set to zero when research and development expenses are missing. In a robustness test, we find that excluding firms with missing research and development expenses does not affect our core inferences.

This ratio is set to zero when advertising expenses are missing. Our main results are robust to excluding firms with missing information on advertising expenses.

From Model 2 in Table 3, we obtain (∂CSR_S)/∂(FS/S) = −3.567 + 0.626 × SIZE. Therefore, the marginal impact of internationalization on CSR is increasing with firm size. Nonetheless, this expression also suggests that the marginal impact of internationalization on CSR is negative for some firms. The size threshold below which this is the case is 3.567/0.626 ≈ 5.7, which is lower than the first quartile (5.89 from Table 2). To be more precise, 5.7 corresponds to the 22nd percentile of SIZE. As such, for firms in the bottom 22 % (top 78 %) of the distribution of SIZE, the marginal impact of internationalization on CSR is negative (positive). We thank an anonymous reviewer for this insight.

We report descriptive statistics for the alternative CSR proxies in Appendix 3.

In this paper we employ the log of sales as our proxy for firm size. Other commonly used proxies for firm size include the log of assets and the log of market capitalization. We find that the three proxies are highly correlated (for instance, the correlation between the log of assets and the log of sales is 0.9). When we replace the log of sales with the log of assets or the log of market capitalization in our baseline model, we find that our evidence is not sensitive to the choice of proxy for size.

We also isolate the financial crisis period (i.e., 2007–2008). Interestingly, we continue to find that internationalization exhibits a positive relationship with CSR over this period.

We consider a balanced sample of 3,984 observations over the 2003–2010 period and find that the coefficient on FS/S is positive and significant.

Note that CSR_A4 has a different scale compared to CSR_S, the dependent variable used in Table 3. In particular, CSR_A4 has a mean of 55.44 and ranges from 6.65 to 97.85, while CSR_S has a mean of −0.17 and ranges from −9 to 15. This explains why the coefficient on FS/S is higher in Table 6, where the dependent variable is CSR_A4, than in Table 3, where the dependent variable is CSR_S.

Alternatively, we also isolate observations with positive CSR_S and negative CSR_S. In unreported regressions on these subsamples, we find that FS/S loads positively only in the subsample with positive CSR_S.

One could expand on the pollution haven hypothesis (e.g., Dam and Scholtens 2008) to provide an interpretation of the negative link between internationalization and Human Rights score: firms may locate subsidiaries in countries or regions with lax standards on Human Rights. Providing direct evidence on this conjecture is beyond the scope of the current study.

Weights are equal to the number of subsidiaries in each country. Data on subsidiaries come from Dyreng and Lindsey (2009).

We also decompose the overall CSR score into strengths (CSR_STR_S) and concerns (CSR_CON_S) and re-run the regressions of Table 9. In unreported results, we find that the weighted average institutional ratings of countries in which the firm discloses subsidiaries are all significantly negatively related to CSR_CON_S. However, the weighted average of two institutional ratings out of seven is significantly positively related to CSR_STR_S. This suggests there is stronger evidence that international diversification to countries with better institutional environments is associated with fewer CSR concerns.

References

Amato, L. H., & Amato, C. H. (2012). Retail philanthropy: Firm size, industry, and business cycle. Journal of Business Ethics, 107, 435–448.

Attig, N. (2011). Intangible assets, organizational capital and corporate social responsibility: Evidence from U.S. manufacturing firms. Working paper, Saint Mary’s University.

Attig, N., Cleary, S., El Ghoul, S., & Guedhami, O. (2013a). Institutional investment horizons and the cost of equity capital. Financial Management, 42, 441–477.

Attig, N., Cleary, S., El Ghoul, S., & Guedhami, O. (2014). Corporate legitimacy and investment–cash flow sensitivity. Journal of Business Ethics, 121, 297–314.

Attig, N., El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., & Suh, J. (2013). Corporate social responsibility and credit ratings. Journal of Business Ethics, 117, 679–694.

Barnea, A., & Rubin, A. (2010). Corporate social responsibility as a conflict between shareholders. Journal of Business Ethics, 97, 71–86.

Black, D. E., Dikolli, S. S., & Dyreng, S. D. (2014). CEO pay-for-complexity and the risk of managerial diversion from multinational diversification. Contemporary Accounting Research, 31, 103–135.

Block, J., & Wagner, M. (2013). The effect of family ownership on different dimensions of corporate social responsibility: Evidence from large US firms. Business Strategy and the Environment (forthcoming).

Brammer, S. J., Pavelin, S., & Porter, L. A. (2006). Corporate social performance and geographical diversification. Journal of Business Research, 59, 1025–1034.

Brammer, S. J., Pavelin, S., & Porter, L. A. (2009). Corporate charitable giving, multinational companies and countries of concern. Journal of Management Studies, 46, 575–596.

Carroll, A. B. (1991). Corporate social performance measurement: A commentary on methods for evaluating an elusive construct. Research in Corporate Social Performance and Policy, 12, 385–401.

Chatterji, A. K., Levine, D. I., & Toffel, M. W. (2009). How well do social ratings actually measure corporate social responsibility? Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 18, 125–169.

Christmann, P., & Taylor, G. (2001). Globalization and the environment: Determinants of firm self-regulation in China. Journal of International Business Studies, 32, 439–458.

Collins, C., & Smith, K. (2006). Knowledge exchange and combination: The role of human resource practices in the performance of high-technology firms. Academy of Management Journal, 49, 544–560.

Dam, L., & Scholtens, L. J. R. (2007). Cultural values and international differences in business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 75, 273–284.

Dam, L., & Scholtens, B. (2008). Environmental regulation and MNEs location: Does CSR matter? Ecological Economics, 67, 55–65.

Detomasi, D. (2007). The multinational corporation and global governance: Modelling global public policy networks. Journal of Business Ethics, 71, 321–334.

Dyreng, S., Hanlon, M., & Maydew, E. (2012). Where do firms manage earnings? Review of Accounting Studies, 17, 649–687.

Dyreng, S., & Lindsey, B. (2009). Using financial accounting data to examine the effect of foreign operations located in tax havens and other countries on U.S. multinational firms’ tax rates. Journal of Accounting Research, 47, 1283–1316.

El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., Kwok, C. C., & Mishra, D. (2011). Does corporate social responsibility affect the cost of capital? Journal of Banking & Finance, 35, 2388–2406.

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1997). Industry costs of equity. Journal of Financial Economics, 43, 153–194.

Fatemi, A. M. (1984). Shareholder benefits from corporate international diversification. Journal of Finance, 39, 1325–1344.

Feldman, S. J., Soyka, P. A., & Ameer, P. (1997). Does improving a firm’s environmental management system and environmental performance result in a higher stock price? Journal of Investing, 6, 87–97.

Friedman, M. (1970). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. New York Times Magazine, 32, 122–126.

Gaba, V., Pan, Y., & Ungson, G. R. (2002). Timing of entry in international market: An empirical study of U.S. Fortune 500 firms in China. Journal of International Business Studies, 33, 39–55.

Galema, R., Plantinga, A., & Scholtens, B. (2008). The stocks at stake: Return and risk in socially responsible investment. Journal of Banking & Finance, 32, 2646–2654.

Geringer, J. M., Beamish, P. W., & DaCosta, R. C. (1989). Diversification strategy and internationalization: Implication for MNE performance. Strategic Management Journal, 10, 109–119.

Godfrey, P. C. (2005). The relationship between corporate philanthropy and shareholder value: A risk management perspective. Academy of Management Review, 30, 777–798.

Goss, A., & Roberts, G. S. (2011). The impact of corporate social responsibility on the cost of bank loans. Journal of Banking & Finance, 35, 1794–1810.

Gow, I. D., Ormazabal, G., & Taylor, D. J. (2010). Correcting for cross-sectional and time-series dependence in accounting research. Accounting Review, 85, 483–512.

Griffin, J. J., & Mahon, J. F. (1997). The corporate social performance and corporate financial performance debate. Business and Society, 36, 5–31.

Hart, S. L. (1995). A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Academy of Management Review, 20, 986–1014.

Hillman, A. J., & Keim, J. D. (2001). Shareholder value, stakeholder management, and social issues: What’s the bottom line? Strategic Management Journal, 22, 125–139.

Hitt, M. A., Hoskisson, R. E., & Kim, H. (1997). International diversification: Effects on innovation and firm performance in product-diversified firms. Academy of Management Journal, 40, 767–798.

Hitt, M. A., Ireland, R. D., & Hoskisson, R. E. (2007). Strategic management: Competitiveness and globalization (7th ed.). Mason, OH: South-Western.

Hong, H., & Kacperczyk, M. (2009). The price of sin: The effects of social norms on markets. Journal of Financial Economics, 93, 15–36.

Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2012). What drives corporate social performance? The role of nation-level institutions. Journal of International Business Studies, 43, 834–864.

Janney, J. J., & Gove, S. (2011). Reputation and corporate social responsibility aberrations, trends, and hypocrisy: Reactions to firm choices in the stock option backdating scandal. Journal of Management Studies, 48, 1562–1585.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J.-E. (1977). The internationalization process of the firm: A model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. Journal of International Business Studies, 8, 23–32.

Jones, T. M. (1995). Instrumental stakeholder theory: A synthesis of ethics and economics. Academy of Management Review, 20, 404–437.

Kacperczyk, A. (2009). With greater power comes greater responsibility? Takeover protection and corporate attention to stakeholders. Strategic Management Journal, 30, 261–285.

Kang, J. (2013). The relationship between corporate diversification and corporate social performance. Strategic Management Journal, 34, 94–109.

Kim, Y., Li, H., & Li, S. (2014). Corporate social responsibility and stock price crash risk. Journal of Banking & Finance, 43, 1–13.

Kim, Y., Park, M. S., & Wier, B. (2012). Is earnings quality associated with corporate social responsibility? Accounting Review, 87, 761–796.

Kirca, H. A., Hult, G. T. M., Deligonul, S., Perry, M. Z., & Cavusgil, S. T. (2012). A multilevel examination of the drivers of firm multinationality: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management, 38, 502–530.

Kogut, B. (1985). Designing global strategies: Profiting from operational flexibility. Sloan Management Review, 21, 27–38.

KPMG. (2013). KPMG international: The KPMG survey of corporate responsibility reporting 2013. http://www.kpmg.com/Global/en/IssuesAndInsights/ArticlesPublications/corporate-responsibility/Documents/corporate-responsibility-reporting-survey-2013-exec-summary.pdf. Accessed 26 March 2014.

Krüger, P. (2014). Corporate goodness and shareholder wealth. Journal of Financial Economics. (forthcoming).

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1998). Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy, 106, 1113–1155.

Li, S., Qiu, J., & Wan, C. (2011). Corporate globalization and bank lending. Journal of International Business Studies, 42, 1016–1042.

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (2001). Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Academy of Management Review, 28, 117–127.

Murtha, P. T., & Lenway, S. A. (1994). Country capabilities and the strategic state: How national political institutions affect multinational Corporations’ strategies. Strategic Management Journal, 15, 113–129.

Nachum, L., & Zaheer, A. (2005). The persistence of distance? The impact of technology on MNE motivations for foreign investment. Strategic Management Journal, 26, 747–767.

Orlitzky, M., Siegel, D. S., & Waldman, D. A. (2011). Strategic corporate social responsibility and environmental sustainability. Business and Society, 50, 6–27.

Petersen, M. A. (2009). Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: Comparing approaches. Review of Financial Studies, 22, 435–480.

Porter, M. E. (1990). The competitive advantage of nations. New York: Free Press.

Rosenbaum, P., & Rubin, D. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70, 41–55.

Sanders, G. W. M., & Carpenter, M. A. (1998). Internationalization and firm governance: The roles of CEO compensation, top team composition, and board structure. Academy of Management Journal, 41, 158–178.

Scholtens, B., & Sievänen, R. (2013). Drivers of socially responsible investing: A case study of four Nordic countries. Journal of Business Ethics, 115, 605–616.

Servaes, H., & Tamayo, A. (2013). The impact of corporate social responsibility on firm value: The role of customer awareness. Management Science, 59, 1045–1061.

Sievänen, R., Rita, H., & Scholten, B. (2013). The drivers of responsible investment: The case of European pension funds. Journal of Business Ethics, 117, 137–151.

Simerly, R. L. (1997). Corporate social performance and multinationality: An empirical examination. International Journal of Management, 14, 699–703.

Simerly, R. L. & Li, M. (2000). Corporate social performance and multinationality, A longitudinal study. Working paper: http://www.westga.edu/~bquest/2000/corporate.html.

Strike, M. V., Gao, J., & Bansal, P. (2006). Being good while being bad: Social responsibility and the international diversification of US firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 37, 254–280.

Sullivan, D. (1994). Measuring the degree of internationalization of a firm. Journal of International Business Studies, 25, 325–342.

Waddock, S. (2003). Myths and realities of social investing. Organization and Environment, 16, 369–380.

Waddock, S. A., & Graves, S. B. (1997). The corporate social performance-financial performance link. Strategic Management Journal, 18, 303–319.

Whitener, E. (2001). Do “high commitment” human resource practices affect employee commitment? A cross-level analysis using hierarchical linear modeling. Journal of Management, 27, 515–535.

Zaheer, S. (1995). Overcoming the liability of foreignness. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 341–363.

Zahra, S. A., & Garvis, D. M. (2000). International corporate entrepreneurship and firm performance: The moderating effect of international environment hostility. Journal of Business Venturing, 15, 469–492.

Zahra, S. A., Ireland, R. D., & Hitt, M. A. (2000). International expansion by new venture firms: International diversity, mode of market entry, technological learning, and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 925–950.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sabri Boubaker, Ruiyuan Chen, Walid Saffar, Helen Wang, and especially Gary Monroe (Section Editor) and two anonymous referees for constructive comments. We appreciate the generous financial support from Canada’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

See Table 10.

Definitions of the Qualitative Issue Area Scores and the Overall CSR Score

CSR_COM_S = (Charitable Giving + Innovative Giving + Non-U.S. Charitable Giving + Support for Housing + Support for Education + Indigenous Peoples Relations + Volunteer Programs + Other Strength) − (Investment Controversies + Negative Economic Impact + Indigenous Peoples Relations + Tax Disputes + Other Concern).

CSR_DIV_S = (CEO + Promotion + Board of Directors + Work/Life Benefits + Women & Minority Contracting + Employment of the Disabled + Gay & Lesbian Policies + Other Strength) − (Controversies + Non-Representation + Other Concern).

CSR_EMP_S = (Union Relations + No-Layoff Policy + Cash Profit Sharing + Employee Involvement + Retirement Benefits Strength + Health and Safety Strength + Other Strength) − (Union Relations + Health and Safety Concern + Workforce Reductions + Retirement Benefits Concern + Other Concern).

CSR_ENV_S = (Beneficial Products and Services + Pollution Prevention + Recycling + Clean Energy + Communications + Property, Plant, and Equipment + Other Strength) − (Hazardous Waste + Regulatory Problems + Ozone Depleting Chemicals + Substantial Emissions + Agricultural Chemicals + Climate Change + Other Concern).

CSR_HUM_S = (Positive Record in South Africa + Indigenous Peoples Relations Strength + Labor Rights Strength + Other Strength) − (South Africa + Northern Ireland + Burma Concern + Mexico + Labor Rights Concern + Indigenous Peoples Relations Concern + Other Concern).

CSR_PRO_S = (Quality + R&D/Innovation + Benefits to Economically Disadvantaged + Other Strength) − (Product Safety + Marketing/Contracting Concern + Antitrust + Other Concern).

CSR_S = CSR_COM_S + CSR_DIV_S + CSR_EMP_S + CSR_ENV_S + CSR_HUM_S + CSR_PRO_S.

Appendix 2

See Table 11.

Appendix 3

See Table 12.

Appendix 4

See Table 13.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Attig, N., Boubakri, N., El Ghoul, S. et al. Firm Internationalization and Corporate Social Responsibility. J Bus Ethics 134, 171–197 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2410-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2410-6