Abstract

Multinational enterprises (MNEs) venturing into emerging economies operate in relatively unfamiliar environments that, compared with their home countries, often display a high degree of administrative distance (i.e., differences in social rules, regulations, and governmental control and enforcement mechanisms). At the same time, many MNEs face the question of how intensely to commit to corporate social responsibility (CSR) in emerging economies, given the often relatively lower social standards in those countries. This research addresses the question of how administrative distance, MNE subsidiary size, and experience in the host country relate to the extent to which MNEs strategically commit to CSR in their emerging economy subsidiaries. We argue that the greater the administrative distance between MNEs’ home and host countries, the lesser the MNE subsidiaries strategically commit to CSR. At the same time, we predict that the larger the size of MNE subsidiaries (as a proxy for local subsidiaries’ available resources), and the longer their experience in the host country, the more the MNE subsidiaries strategically commit to CSR. To test our hypotheses, we use data from a large-scale, cross-industry survey of 213 subsidiaries of Western MNEs in Asia, Eastern Europe, and Latin America. We complement the survey data with country-level data from the World Bank Governance Indicators.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The question of how intensely to engage in corporate social responsibility (CSR) ranks high on the agenda of multinational enterprises (MNEs) (Reimann et al. 2012). Increasingly, firms move away from isolated social activities (e.g., making selective donations) toward establishing CSR as an overarching business activity, to increase the authentic value of their commitment (Hart and Milstein 2003). Such emphasis on strategic commitment to CSR might be particularly important when operating in emerging economies, a context in which administrative requirements for CSR are often relatively lower than in developed markets (Lee 2011; Yang and Rivers 2009). In addition, MNEs have long been accused of harboring exploitative intentions in emerging economies, such as taking advantage of low local labor rights or poor working standards for their own profit (Christmann and Taylor 2006). However, research has only scarcely explored the role of different administrative environments on MNE subsidiaries’ strategic commitment to CSR in emerging economies. Furthermore, despite general acknowledgment that firms’ commitment to CSR is resource consuming (Russo and Perrini 2010), scant research has investigated the role of MNE subsidiary size (as a proxy for subsidiaries’ available resources) and MNE subsidiary’s experience in the host country (as a proxy for accumulated knowledge and awareness of the local situation) in determining their strategic commitment to CSR in emerging economies. To further augment knowledge in the area, we investigate the following research question: How do administrative distance, MNE subsidiary size, and MNE subsidiary’s experience in the host country (as a proxy for accumulated knowledge and awareness of the local situation) relate to the extent to which MNE subsidiaries strategically commit to CSR in emerging economies?

We define strategic commitment to CSR as the extent to which MNE subsidiaries make clear their strategic intentions and direction to CSR (Pirsch et al. 2007), which provides guidance to their organizational members on the seriousness attached to CSR issues (Boswell and Boudreau 2001). Strategic commitment to CSR involves the dedication of resources, such as channeling management attention to CSR (Carter and Jennings 2004), making CSR an integral part of the local business strategy (Aguilera et al. 2007), placing CSR at the center of corporate branding (Sen and Bhattacharya 2001), and defining and monitoring measurable targets regarding social performance (Marrewijk et al. 2004). By implementing such guiding principles, MNEs can provide their organizational members a “framework of meaning” (Jarzabkowski 2005, p. 95) with which they can align their actions (Noda and Bauer 1996).

With our research, we investigate an apparent paradox MNEs face in emerging economies. On the one hand, MNEs’ need to build legitimacy with local constituents increases with rising cross-country distance (Kostova and Zaheer 1999; Lee 2011) and higher visibility of the firm (González-Benito and González-Benito 2006; Meznar and Nigh 1995). Prior research suggests that CSR can help building legitimacy in emerging economies (Reimann et al. 2012). On the other hand, MNEs face rising costs and complexities in administratively distant countries (Eden and Miller 2004; Kostova and Zaheer 1999), which, depending on their local subsidiary size, might force them to dedicate their scarce resources on their core business and thus limit their ability to move away from isolated CSR activities to develop a true overarching strategic commitment to CSR (Campbell et al. 2012).

Along these lines, we aim to contribute to the literature in two ways. First, we break new ground by employing institutional theory to investigate the role of administrative distance on MNE subsidiaries’ strategic commitment to CSR in the specific context of emerging economies. Second, we extend findings on the impact of firm size and local experience on MNE subsidiaries’ strategic commitment to CSR from a developed country context to the context of emerging economies.

To empirically test our hypotheses, we use a large-scale, cross-industry sample of 213 subsidiaries of German corporations in Brazil, China, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and India. Furthermore, we combine the sample data with country-level data drawn from the World Bank’s Governance Indicators on the administrative environments of the countries in our study. By focusing on this heterogeneous subset of emerging economies, we capture good variance of home–host country distance. The sampled countries all possess heterogeneous administrative and economic backgrounds and follow unique scales and scope of transformation to more rule-based administrative frameworks (Peng 2003; Peng et al. 2008), placing them at different relative administrative distance to the MNEs’ home country, Germany.

The remainder of this article proceeds as follows: We begin by examining administrative distance as the core concept of this study. Then, we present the research framework and hypotheses. Next, we provide the study’s methodology and empirical results. Finally, we discuss the research findings and limitations and offer further directions for research in the field.

Administrative Distance and MNEs’ Strategic Commitment to CSR

Differences between countries, frequently measured as institutional distance along various dimensions (Berry et al. 2010), influence firm strategy in several ways, including entry modes, ownership strategies (Delios and Beamish 1999; DiMaggio and Powell 1983; Gaur and Lu 2007; Meyer and Rowan 1977; Xu et al. 2004; Xu and Shenkar 2002; Yiu and Makino 2002), and staffing strategies (Boyacigiller 1990; Gaur et al. 2007; Gong 2003; Harzing 2001). Recently, research has also begun to shed light on the role of distance on firms’ stance on CSR. One dimension of distance that might be particularly influential in this regard is administrative distance, which captures differences in local rules, regulations, and governmental control and enforcement mechanisms (Ghemawat 2001; Kaufmann et al. 2006).

Prior research has argued that such distance increases a firm’s risk of being met with distrust by local stakeholders (Lee 2011; Yang and Rivers 2009), which can increase a firm’s disadvantages in accessing local resources and markets. Especially in the context of emerging economies, MNEs face such legitimacy challenges, manifested in a frequent accusation that MNEs exploit locally weaker administrative standards for their own profit (Christmann and Taylor 2006; Korten 1995; Vernon 1998; Walter 1982). In the particular context of CSR, Campbell et al. (2012) analyze the influence of administrative distance on “social” mortgage lending practices of foreign bank subsidiaries in the United States, finding a negative link between the two constructs. We expand these inroads by taking a broader, more strategy-focused perspective—namely, the strategic commitment firms place on social issues—and by focusing on the context of emerging economies, in which the notion of CSR and legitimacy challenges might differ from the Western world. To compute administrative distance between the countries in our sample, following the proven method of Campbell et al. (2012), Ghemawat (2001), and Lavie and Miller (2008), we capture data on countries’ administrative frameworks from the World Bank’s Governance Indicators, including voice and accountability, political stability and absence of violence, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and control of corruption.

Research Framework and Hypotheses

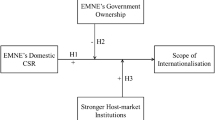

Our research framework comprises the relationships between home–host country administrative distance, MNE subsidiary size, and MNE experience in the host country (three antecedents) and MNE subsidiaries’ strategic commitment to CSR in emerging economies. In addition, we test for the moderating role of MNE subsidiary size and MNE experience in the host country on the relationship between administrative distance and MNEs’ strategic commitment to CSR. Figure 1 depicts the research framework and the results.

Administrative Distance and MNE Subsidiaries’ Strategic Commitment to CSR

Administrative distance between firms’ home and host countries refers to differences in countries’ rules, regulations, and governmental control and enforcement mechanisms (Ghemawat 2001; Kaufmann et al. 2006). To predict the relationship between administrative distance and MNE subsidiaries’ strategic commitment to CSR in emerging economies, different lines of theory are available, but they lead to controversial conclusions.

On the one hand, CSR can serve as a means for MNEs to improve their local legitimacy in emerging economies (Bartlett et al. 2007; Gifford and Kestler 2008; Reimann et al. 2012). This suggests a positive relationship between administrative distance and MNEs’ strategic commitment to CSR because MNEs have greater difficulties in building rapport with local constituents the more distant home and host country are (Kostova and Zaheer 1999; Lee 2011).

On the other hand, strands of research have posited a negative link between administrative distance and MNEs’ strategic commitment to CSR in emerging economies. First, according to Walter’s (1982) “pollution haven” theorem, MNEs might take advantage of administrative cross-country differences and allocate their subsidiary operations to the countries that have less strict regulation and less stringent control and enforcement mechanisms in CSR-relevant areas (Christmann and Taylor 2001). Thus, as long as emerging economies’ administrative environments do not provide sufficient inducements for firms to strategically commit to CSR as part of their local business conduct or apply little, if any, corresponding penalties, MNE subsidiaries will likely not commit to CSR (Yang and Rivers 2009).

Second, institutional theory, in particular the “concept of isomorphism” (i.e., foreign firms’ adoption of conduct similar to those of local firms), proposes a negative link between administrative distance and MNEs’ strategic commitment to CSR. According to prior research, isomorphism helps foreign MNEs survive in distant environments (Deephouse 1996; DiMaggio and Powell 1983; Kostova and Zaheer 1999; Meyer and Rowan 1977). By isomorphically adapting their business conduct to that of local incumbent firms, MNE subsidiaries are likely to avoid potential pitfalls (that might put them at a disadvantage to local competitors) and thus operate successfully in the foreign environment (Kostova and Zaheer 1999). Therefore, when operating in administratively distant emerging economies, MNE subsidiaries may mimic the relatively low levels of strategic commitment to CSR of local competitors.

Third, Campbell et al. (2012) empirically find that administrative distance is negatively related to some forms of CSR (social mortgage lending practices of banks) in a developed country context. They argue that with rising administrative distance, foreign affiliates have difficulties in dealing with contextual uncertainties, leading to “liability of foreignness” (LOF), or the extra costs incurred from a firm’s foreignness in a new business environment (Mezias 2002; Zaheer 1995), which ultimately decrease firms’ ability to commit to resource-intensive CSR. Especially when operating in highly administratively distant emerging economies, MNEs must cope with additional costs related to devoting their local subsidiaries’ resources to aspects such as “monitoring, dispute settlement, opportunistic behavior of local partners, and lack of trust in unknown partners” (Gaur and Lu 2007, p. 88). In turn, LOF might limit MNEs’ ability to allocate their subsidiaries’ resources to strategically commit to CSR in emerging economies.

In summary, despite the commitment to CSR as a potential way to build much-needed legitimacy, we argue that greater administrative distance increasingly restrains MNEs from committing to CSR because of their potential advantages from cross-country administrative arbitrage, isomorphic pressures to mimic local incumbents, and significant degrees of LOF. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H1

The greater the administrative distance between MNEs’ home and host countries, the lesser is the MNE subsidiaries’ strategic commitment to CSR.

MNE Subsidiary Size and MNE Subsidiaries’ Strategic Commitment to CSR

MNE subsidiary size, measured by MNE’s number of subsidiary employees (e.g., Aragón-Correa 1998; Elsayed 2006), may affect the level of MNEs’ strategic commitment to CSR in emerging economies for two reasons. First, the larger the subsidiary, the higher is its visibility among local constituents (González-Benito and González-Benito 2006; Meznar and Nigh 1995) that, according to legitimacy theory, often scrutinize MNEs’ strategic commitment to CSR to judge the firms’ conformance to local values and beliefs (Suchman 1995). Particularly in an emerging economy context, in which MNEs are often accused of harboring exploitative intentions (Christmann and Taylor 2006), large and, thus, more visible MNE subsidiaries may have a strong incentive to strategically commit to CSR as a means to prevent reputational damages and enhance local legitimacy.

Second and in line with Bowen (1999), firm size not only captures an organization’s visibility but also extends to a firm’s availability of managerial slack resources (Brammer and Millington 2006), which help develop a firm’s strategic commitment to CSR. That is, committing the firm to CSR is a resource-intense management challenge, including “gathering information on [CSR-related standards in a local environment], passing this information up through the organization and liaising with internal planners” (Galbreath 2010, p. 514). The larger MNEs’ subsidiaries, the greater may be their access to the managerial resources required to conduct these tasks (Johnson and Greening 1999; Perrini et al. 2007) and to formalize their internal management processes directed to CSR commitment (Donaldson 2001), including an “improved issues management architecture that facilitates improved social responsiveness” (Brammer and Millington 2006, p. 9). In contrast, smaller MNE subsidiaries may more likely dedicate their scarce managerial resources on strengthening their core business activities (Udayasankar 2007) and short-term economic survival (Munilla and Miles 2005), by concentrating on developing their local production facilities, their supply chain, and their sales, client, and distribution networks in emerging economies. To test this perspective, we hypothesize:

H2

The larger the MNE subsidiaries’ size, the greater is their strategic commitment to CSR.

Host Country Experience and MNE Subsidiaries’ Strategic Commitment to CSR

From a theoretical perspective, two different lines of argument on the influence of host country experience on strategic commitment to CSR can be made, leading to differing predictions regarding the relationship. First, when a firm enters a foreign market, it faces deficiencies in knowledge of the local environment, which can constitute a significant competitive disadvantage compared with local incumbent firms (Delios and Beamish 1999; Hymer 1976). Scholars like Davis et al. (2000) and Gaur and Lu (2007) argue that through a process of acculturation and experience, firms can over time reduce their unfamiliarity and build up the knowledge and capabilities (Barkema and Vermeulen 1997; Delios and Beamish 2001; Luo and Peng 1999) required for effective and efficient operation in the host country. Thus, at the early stages of strategy design, MNEs’ priority might lie in allocating firm-internal resources to primarily strengthen the core business (Munilla and Miles 2005). For example, MNEs might need to allocate their management capacities to their production facilities, their supply chain and distribution networks, and to ensure compliance with the administrative requirements of the host country (Gaur and Lu 2007). When MNEs have firmly established their business operation in the host country environment, they might use the now freed-up management capacities to commit more strongly to CSR. Thus, we would expect that MNEs over time increase their commitment to CSR as a legitimacy-catalyzing vehicle in their host country operations (Gardberg and Fombrun 2006).

On the other hand, when operating in unfamiliar environment, firms often resort to isomorphic strategies, i.e., they try to align their own business practices with those of local competitors (Miller and Eden 2006; Zaheer 1995). In the case of emerging economy host countries, CSR commitment of local competitors will often be relatively low (Lee 2011; Yang and Rivers 2009), so that for many MNEs, a process of isomorphic adaptation likely implies a lowering of their own CSR efforts during the adaptation process. Early in the subsidiary’s life, business practices often still resemble those of the headquarters, since subsidiary management is not yet familiar with the new business environment and does not know well how to adapt. Over time, firms have more opportunity to observe local competitors’ approaches, including their stance on CSR, so that the possibility for isomorphic behavior and a resulting lowering of CSR commitment increases.

While both of these lines of arguments appear plausible, recent empirical research by Salomon and Wu (2012) counters the notion of increasing isomorphic adaptation over time. Particularly, these authors find that general isomorphic behavior in distant environments does not increase with local experience, but remains constant. We therefore expect that the described mechanics leading to a positive link between host country experience and commitment to CSR play out more strongly, and we tentatively put forth:

H3

The longer MNEs’ experience in respective host countries, the higher is the degree to which they integrate CSR elements into their subsidiary strategies.

Moderating Effects

Our argumentation leading to H1 proposes that MNE subsidiaries can be restrained from committing to CSR because of (1) their advantages from cross-country administrative arbitrage, (2) isomorphic pressures to mimic local incumbents, and (3) the significant degrees of LOF in emerging economies. We hypothesize that these mechanics work less strongly for larger subsidiaries and for subsidiaries with longer host-country experience—that is, that subsidiary size and host country experience not only directly affect strategic commitment to CSR but also positively moderate the link between administrative distance and strategic commitment to CSR.

First, larger firms have higher visibility both locally and internationally (González-Benito and González-Benito 2006; Udayasankar 2007) and therefore may be more careful not to take advantage of lower social standards in administratively distant emerging economies. Second, because of their greater resource availability (Brammer and Millington 2006; Perrini et al. 2007), larger subsidiaries may be less affected by LOF. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H4

The larger the MNE subsidiaries’ size, the weaker is the negative impact of administrative distance between MNEs’ home and host countries on MNE subsidiaries’ strategic commitment to CSR.

With longer experience, firms are able to more accurately interpret differences in their host country’s local rules, regulations, and governmental control and enforcement mechanisms (Gaur et al. 2007). That is, experience allows firms to better deal with the local environment, overcome liabilities of foreignness and thus reduces the relevance of home-host country administrative distance for the firm’s conduct (Henisz and Williamson 1999). Thus, we expect:

H5

The higher the MNE subsidiary’s experience in the host country, the weaker is the negative impact of administrative distance between MNEs’ home and host countries on MNE subsidiaries’ strategic commitment to CSR.

Methodology

We analyzed the subsidiaries of German firms in five host countries: Brazil, China, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and India (Table 1). Because the literature provides no universally accepted definition for “emerging economies” or a fixed set of countries belonging to a group of emerging economies, we follow Dow Jones and the Forbes-accredited Euromoney Institutional Investor Company, both of which use the term, to select the countries in our sample (Dow Jones Indexes 2010; Ehrgott et al. 2011). The five countries in our sample represent a high level of German foreign direct investment, represent economies from the world’s major emerging growth regions (Asia, Eastern Europe, and Latin America), and have varying administrative distances from Germany.

Data Collection and Sample

For data collection, we mailed a standardized questionnaire to the respective subsidiary heads. To compute the score for administrative distance between Germany and the respective host countries, we followed previous research (Campbell et al. 2012; Ghemawat 2001; Lavie and Miller 2008), used the 2007 World Bank Governance Indicators, and applied the Euclidean distance calculationFootnote 1 (Kogut and Singh 1988). Table 1 shows each country’s overall administrative distance from Germany.

Two pretests with eight CSR and international business scholars and seven managers from a diverse range of industries and regions helped improve clarity of the item wording. In total, 778 potential respondents in the five countries were approached through the German Chamber of Commerce. All were subsidiaries that had local production or logistic operations in the target country, with only one subsidiary per parent firm in each country. The overall response rate was 27.4 %, with a total response of 213 subsidiaries (see Table 1)Footnote 2. Tables 2 and 3 show the diversity of industries and firm size.

Scale Development

We used or adapted existing scales from Banerjee et al. (2003), Carter and Jennings (2004), and Judge and Douglas (1998) to measure the dependent variable “MNE subsidiary’s strategic commitment to CSR.” We formulated the associated items as statements, which asked respondents to indicate their level of agreement on a seven-point Likert-type scale, anchored by “strongly agree” and “strongly disagree.” The country-level independent variable “administrative distance” is based on items from the 2007 World Bank’s Governance Indicators. Table 1 provides a list of the included items.

For the measurement of the firm-level independent variable “MNE subsidiary size”, we followed extant literature in drawing on the number of employees (e.g., Aragón-Correa 1998; Elsayed 2006). In this, we asked the respondents to indicate the number of their local subsidiary employees as a proxy for their local subsidiaries’ slack resources available to strategically commit to CSR in light of rising LOF (extra costs) in emerging economies. To reflect the likely diminishing marginal effect of additional employees, we used the natural log of the number of employees for calculating the model (Mishra and Modi 2013; Gaur et al. 2014; Peng and Beamish 2014).

The firm-level independent variable “MNEs’ experience in host countries” refers to the number of years that the respective subsidiary in the country has been in existence. Also for this measure, we used to natural log to reflect likely diminishing marginal effects (Riaz et al. 2014).

Key Informant Issue

To ensure the robustness of the results against key informant issues, we sent the survey only to the heads of the respective subsidiaries and asked them to report both the number of years they had held their current position and the intensity of their involvement in social issues at their subsidiaries (Kumar et al. 1993). The average respondents’ (mean) tenure in their current position was 8.2 years; their average involvement scored 5.4 (with a range from 2 to 7 on the Likert-type scale), demonstrating adequate knowledge of respondents on all aspects. To mitigate social desirability bias, we applied the other-based questioning technique (Armacost et al. 1991), asking subsidiary heads to answer the survey questions with regard to their country subsidiary as a whole. We also guaranteed anonymity to all respondents.

Control Variables

To ensure the robustness of the structural model and consistency of our findings across a range of different settings, we introduced four additional control variables. First, we controlled for industry because the level of commitment to CSR may differ from industry to industry, either because the nature of operations in some industries is particularly sensitive to CSR issues or because public awareness of certain industries is greater as a result of increased media coverage (González-Benito and González-Benito 2006; Kolk et al. 2001). Second, we controlled for MNE subsidiaries’ people orientation in organizational culture, measured by adapting existing scales from O’Reilly et al. (1991), Chatman and Jehn (1994), and Carter and Jennings (2004), as a proxy of MNE local managers’ intrinsic motivation to help local people by defining their firms’ strategic commitment to local CSR (Carter and Jennings 2004). Third, we controlled for social pressure from government, applying existing scales from Reimann et al. (2012), because emerging economy governments have recently begun to attach greater importance to CSR as part of their country development programs and to assign MNEs integral roles in those programs. Fourth, we controlled for social pressure from middle management, also applying existing scales from Reimann et al. (2012) who found that middle management influences CSR practices in emerging economies.

Results

We applied structural equation modeling using the AMOS software to test our hypotheses. We assessed the measurement model of the constructs using confirmatory factor analysis. Following Byrne (2001), we identified items to be eliminated using the modification indexes as provided by AMOS. We excluded some construct items from further analyses to improve goodness of fit of the structural model (see Appendix 1). Finally, each of the remaining scale items had a factor loading of at least 0.40, and all factor loadings were highly significant (p < 0.0001), suggesting that convergent validity exists for the indicators (Gerbing and Anderson 1988). Table 4 provides the correlations among the constructs.

We used the Chi square/degrees of freedom ratio (χ 2/df), Bentler’s (1989) comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), the adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) to assess the fit of the structural model (Dion 2008). The resulting values (χ 2/df ratio: 0.949; CFI: 1.000; TLI: 1.002; GFI: 0.984; AGFI: 0.956; and RMSEA: 0.000) indicated a satisfactory fit (Bagozzi and Yi 1988; Hu and Bentler 1999).

To empirically assess the moderation effect of MNE subsidiary size and MNE experience in the host country on the relationship between administrative distance and MNEs’ strategic commitment to CSR (H4, H5), we applied the method of interaction moderation (Baron and Kenny 1986). Here, we computed the interaction term between the two respective antecedent constructs (standardized values of administrative distance multiplied by standardized values of MNE subsidiary size for H4; standardized values of administrative distance multiplied by standardized values of MNE experience in host country for H5) and added this term as a additional independent variables (antecedent) to our structural equation model (Edwards and Lambert 2007).

The results from the hypothesis testing appear in Fig. 1; the solid lines represent a significant relationship (p < 0.05) between the constructs, and the dashed lines indicate the lack of a statistically significant relationship. H1 and H2 were statistically supported; H3, H4 and H5 were not supported.

Discussion and Summary

First, and as expected, we found that administrative distance between MNEs’ home and emerging economy host countries is negatively associated with their strategic commitment to CSR in emerging economies (H1). This finding ties in with institutional theorists who argue that MNEs often use administrative cross-country differences for their own benefits (Christmann and Taylor 2006) and with scholars who attest to MNEs’ isomorphic adaptation to local incumbent firms’ conduct (Deephouse 1996; DiMaggio and Powell 1983; Kostova and Zaheer 1999; Meyer and Rowan 1977). Furthermore, the observed negative link between administrative distance and MNE subsidiaries’ strategic commitment to CSR extends previous findings of Campbell et al. (2012) in two ways: first, from the developed country context to the context of emerging economies and, second, to a broader definition of CSR commitment. That is, we show that despite MNEs’ need to embrace CSR in an effort to transform their emerging economy stakeholder relationships from conflicted or neutral to cooperative (Bartlett et al. 2007), MNEs may face hindrances in committing to CSR in emerging economies because of the significant challenges and LOF they encounter when operating in an emerging economy.

Second, we confirmed a positive relationship between MNE subsidiary size and MNE subsidiaries’ strategic commitment to CSR in emerging economies (H2). In doing so, we extend previous findings from a developed country context to the context of emerging economies, arguing that larger and more visible organizations face more scrutiny from local constituents to engage in CSR than smaller organizations (González-Benito and González-Benito 2006; Meznar and Nigh 1995) and that larger organizations have a greater ability to apply slack resources to the definition of their commitment to CSR (Bowen 1999; Brammer and Millington 2006; Udayasankar 2007).

Third, we did not find support for the expected positive relationship between MNE experience in the host country and commitment to CSR (H3). Also, we found no moderating effects of MNE subsidiary size (H4) and MNE experience in the host country (H5) on the link between administrative distance and commitment to CSR.

Summarizing, our study offers several useful insights for scholars and practitioners. We find that firms tend to commit less to CSR in their subsidiaries the higher home–host country administrative distance is. This relationship appears to be stable, regardless of firm size and experience in the host country. While we are careful to interpret these findings, they provide some indication that firms purposefully decide to commit less to CSR in distant environments, and that this decision is not changed much over time. For managers, it is important to be aware that competitors might act according to this pattern, since it might present threats (if competitors manage to achieve cost advantages through these strategies), as well as opportunities when a firm can manage to differentiate itself by committing more strongly to CSR against the trend. Scholars have pointed to advantages that such above-average CSR commitment can bring (Golicic and Smith 2013), particularly with regard to improving stakeholder relationships (Bartlett et al. 2007; Gifford and Kestler 2008; Reimann et al. 2012). Further, we find very clearly that large firms place higher emphasis on CSR in their emerging economy subsidiaries than smaller firms. This raises several important questions regarding both the reasons for this difference, and for potential outcomes. Do smaller firms commit less to CSR because they are under higher economic pressure and have less resources available (Perrini et al. 2007), or do they feel they can afford to commit less because they are “under the radar” of public scrutiny (González-Benito and González-Benito 2006)? Regarding outcomes, is it that commitment to CSR pays out less for smaller firms than for large firms, or would managers of smaller firms be well advised to pay more attention to this topic? In any case, managers of smaller firms might want to review their level of CSR commitment, and look for opportunities for their firms to differentiate by creating value for employees and communities with the resources available.

Limitations and Further Research

Several limitations to this study could represent worthwhile avenues for further research. First, we focus our investigation on the context of Western firms’ operations in emerging economies. A particularly noteworthy expansion of this empirical scope would be to compare our findings with contexts in which emerging economy firms operate in other emerging economies. While general living conditions in such context are often relatively similar between home and host country, administrative distance can still be substantial.

Second, future studies could expand the measurement scope of MNEs’ strategic commitment to CSR that we applied herein—for example, by including aspects targeted at environmental goods (Aguilera-Caracuel et al. 2012) or on CSR in the broader supply chain (Pagell and Shevchenko 2013; Thornton et al. 2013)—and thereby apply a more holistic proxy for MNEs’ strategic commitment to CSR in emerging economies.

Third, we focused on administrative distance as one aspect of cross-country distance to keep the theoretical discussion to a manageable level. Further research might complement this perspective by taking into account additional measures of distance. A starting point in this regard is the work of Berry et al. (2010), which outlines nine dimensions of cross-national distance: economic, financial, political, administrative, cultural, demographic, knowledge, connectedness, and geographic aspects.

Fourth, following Shenkar’s (2012) call not only to examine effects from country-level distance but also to investigate potential mechanisms that help firms overcome the negative effects of distance, we encourage CSR research to examine additional firm-level variables (other than MNE subsidiary size) and their wider effects on helping MNEs overcome LOF while enhancing local legitimacy in distant environments.

Notes

Euclidean distance formula:

$$AD_{\rm c} = \sum\limits_{i = 1}^{n}\; [I_{\rm c} - I_{\rm g})^{2}/V_{\rm I}]/n,$$where AD c is the administrative distance between country c and Germany, n is the number of indicators for a particular measure (six for AD c), I c refers to institutional indicator (I) for country c, I g refers to institutional indicator (I) for Germany (g), and V I is the variance of indicator I.

This sample resulted from the same data collection effort that is the basis for Reimann et al. (2012).

References

Aguilera, R. V., Rupp, D. E., Williams, C. A., & Ganapathi, J. (2007). Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 836–863.

Aguilera-Caracuel, J., Hurtado-Torres, N. E., & Aragón-Correa, J. A. (2012). Does international experience help firms to be green? A knowledge-based view of how international experience and organisational learning influence proactive environmental strategies. International Business Review, 21, 847–861.

Aragón-Correa, J. A. (1998). Strategic proactivity and firm approach to the natural environment. Academy of Management Journal, 41(5), 556–567.

Armacost, R. L., Hosseini, J. C., Morris, S. A., & Rehbein, K. A. (1991). An empirical comparison of direct questioning, scenario, and randomized response methods for obtaining sensitive business information. Decision Sciences, 22, 1073–1090.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16, 74–95.

Banerjee, S. B., Iyer, E. S., & Kashyap, R. K. (2003). Corporate environmentalism: Antecedents and influence of industry type. Journal of Marketing, 67(2), 106–122.

Barkema, H. G., & Vermeulen, F. (1997). What cultural differences are detrimental for international joint ventures? Journal of International Business Studies, 28, 846–864.

Baron, R. B., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The Moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Bartlett, C. A., Ghoshal, S., & Beamish, P. W. (2007). Transnational management: Text, cases, and readings in cross-border management (5th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Bentler, P. M. (1989). EQS structural equations program manual. Los Angeles, CA: BMDP Statistical Software.

Berry, H., Guillén, M. F., & Zhou, N. (2010). An institutional approach to cross-national distance. Journal of International Business Studies, 41, 1460–1480.

Boswell, W. R., & Boudreau, J. W. (2001). How leading companies create, measure and achieve strategic results through ‘line of sight’. Management Decision, 39(10), 851–859.

Bowen, F. E. (1999). Does organizational slack stimulate the implementation of environmental initiatives? In D. Wood & D. Windsor (Eds.), Proceedings of the Tenth Annual Meeting of the International Association of Business and Society (pp. 234–244). Paris: IABS proceedings.

Boyacigiller, N. (1990). The role of expatriates in the management of interdependence, complexity and risk in multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies, 21, 357–381.

Brammer, S., & Millington, A. (2006). Firm size, organizational visibility and corporate philanthropy: An empirical analysis. Business Ethics: A European Review, 15(1), 6–18.

Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Campbell, J. T., Eden, L., & Miller, S. R. (2012). Multinationals and corporate social responsibility in host countries: Does distance matter? Journal of International Business Studies, 43, 84–106.

Carter, C. R., & Jennings, M. M. (2004). The role of purchasing in corporate social responsibility: A structural equation analysis. Journal of Business Logistics, 25, 145–186.

Chatman, J. A., & Jehn, K. A. (1994). Assessing the relationship between industry charachteristics and organizational culture: How different can you be? Academy of Management Journal, 37, 522–553.

Christmann, P., & Taylor, G. (2001). Globalization and the environment: Determinants of firm self-regulation in China. Journal of International Business Studies, 32, 439–458.

Christmann, P., & Taylor, G. (2006). Firm self-regulation through international certifiable standards: Determinants of symbolic versus substantive implementation. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(6), 863–878.

Davis, P. S., Desai, A. B., & Francis, J. D. (2000). Mode of international entry: An isomorphism perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 31(2), 239–258.

Deephouse, D. (1996). Does isomorphism legitimate? Academy of Management Journal, 39, 1024–1039.

Delios, A., & Beamish, P. W. (1999). Ownership strategy of Japanese firms: Transactional, institutional, and experience influences. Strategic Management Journal, 20, 915–933.

Delios, A., & Beamish, P. W. (2001). Survival and profitability: The roles of experience and intangible assets in foreign subsidiary performance. Academy of Management Journal, 44, 1028–1038.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48, 47–160.

Dion, P. A. (2008). Interpreting structural equation modeling results: A reply to Martin and Cullen. Journal of Business Ethics, 83, 365–368.

Donaldson, L. (2001). The contingency theory of organizations. London: Sage Publications.

Dow Jones Indexes. (2010). Dow Jones total stock market indexes. New York: CME Group Index Services LLC.

Eden, L. and Miller, S. R. (2004). Distance matters: Liability of foreignness, institutional distance and ownership strategy. Bush School working paper no. 404. Texas A&M University, College Station, TX.

Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 1–22.

Ehrgott, M., Reimann, F., Kaufmann, L., & Carter, C. R. (2011). Social sustainability in selecting emerging economy suppliers. Journal of Business Ethics, 98, 99–119.

Elsayed, K. (2006). Reexamining the expected effect of available resources and firm size on firm environmental orientation: An empirical study of UK firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 65, 297–308.

Galbreath, J. (2010). Drivers of corporate social responsibility: The role of formal strategic planning and firm culture. British Journal of Management, 21, 511–525.

Gardberg, N. A., & Fombrun, C. J. (2006). Corporate citizenship: Creating intangible assets across institutional environments. Academy of Management Review, 31, 329–346.

Gaur, A. S., Delios, A., & Singh, K. (2007). Institutional environments, staffing strategies, and subsidiary performance. Journal of Management, 33(4), 611–636.

Gaur, A. S., Kumar, V., & Singh, D. (2014). Institutions, resources, and internationalization of emerging economy firms. Journal of World Business, 49, 12–20.

Gaur, A. S., & Lu, J. W. (2007). Ownership strategies and survival of foreign subsidiaries: Impacts of institutional distance and experience. Journal of Management, 33(1), 84–109.

Gerbing, D. W., & Anderson, J. C. (1988). An updated paradigm for scale development incorporating unidimensionality and its assessment. Journal of Marketing Research, 25, 186–192.

Ghemawat, P. (2001). Distance still matters: The hard reality of global expansion. Harvard Business Review, 79(8), 137–147.

Gifford, B., & Kestler, A. (2008). Toward a theory of local legitimacy by MNEs in developing nations: Newmont mining and health sustainable development in Peru. Journal of International Management, 14, 340–352.

Golicic, S. L., & Smith, C. D. (2013). A meta-analysis of environmentally sustainable supply chain management practices and firm performance. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 49(2), 78–95.

Gong, Y. (2003). Subsidiary staffing in multinational enterprises: Agency, resources, and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 46, 728–739.

González-Benito, J., & González-Benito, Ó. (2006). A review of determinant factors of environmental proactivity. Business Strategy and the Environment, 15, 87–102.

Hart, S. L., & Milstein, M. B. (2003). Creating sustainable value. Academy of Management Executive, 17(2), 56–67.

Harzing, A.-W. (2001). Who’s in charge? An empirical study of executive staffing practices in foreign subsidiaries. Human Resource Management, 40, 139–158.

Henisz, W. J., & Williamson, O. E. (1999). Corporate economic organization—Within and between countries. Business and Politics, 1(3), 261–277.

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Hymer, S. (1976). The international operations of national firms: A study of direct investment. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

Jarzabkowski, P. (2005). Strategy as practice: An activity based approach. London: Sage.

Johnson, R. D., & Greening, D. W. (1999). The effects of corporate governance and institutional ownership types on corporate social performance. Academy of Management Journal, 42(5), 564–576.

Judge, J. W. Q., & Douglas, T. J. (1998). Performance implications of incorporating natural environmental issues into strategic planning process: An empirical assessment. Journal of Management Studies, 35(2), 241–262.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2006). Governance matters: Aggregate and individual governance indicators for 1996–2005. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 4012, Washington, DC.

Kogut, B., & Singh, H. (1988). The effect of national culture on the choice of entry mode. Journal of International Business Studies, 19(3), 411–432.

Kolk, A., Walhain, S., & Van de Wateringen, S. (2001). Environmental reporting by the Fortune Global 250: Exploring the influence of nationality and sector. Business Strategy and the Environment, 10, 15–28.

Korten, D. C. (1995). When corporations rule the world. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Kostova, T., & Zaheer, S. (1999). Organizational legitimacy under conditions of complexity: The case of the multinational enterprise. Academy of Management Review, 24, 64–81.

Kumar, N., Stern, L. W., & Anderson, J. C. (1993). Conducting interorganizational research using key informants. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 1633–1651.

Lambert, D. M., & Harrington, T. C. (1990). Measuring nonresponse bias in customer service mail surveys. Journal of Business Logistics, 11, 5–25.

Lavie, D., & Miller, S. R. (2008). Alliance portfolio internationalization and firm performance. Organization Science, 19(4), 623–646.

Lee, M.-D. P. (2011). Configuration of external influences: The combined effects of institutions and stakeholders on corporate social responsibility strategies. Journal of Business Ethics, 102, 281–298.

Liesch, P. W., & Knight, G. A. (1999). Information internalisation and hurdle rates in SME internationalisation. Journal of International Business Studies, 30(2), 383–394.

Luo, Y., & Peng, M. W. (1999). Learning to compete in a transition economy: Experience, environment, and performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 30, 269–296.

Marrewijk, M., Wuisman, I., De Cleyn, W., Timmers, J., Panapanaan, V., & Linnanen, L. (2004). A phase-wise development approach to business excellence: Towards an innovative, stakeholder-oriented assessment tool for organizational excellence and CSR. Journal of Business Ethics, 55, 83–98.

Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalised organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340–363.

Mezias, J. M. (2002). Identifying liabilities of foreignness and strategies to minimize their effects: The case of labor lawsuit judgments in the United States. Strategic Management Journal, 23, 229–244.

Meznar, M. B., & Nigh, D. (1995). Buffer or bridge? Environmental and organizational determinants of public affairs activities in American firms. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 975–996.

Miller, S. R., & Eden, L. (2006). Local density and foreign subsidiary performance. Academy of Management Journal, 49(2), 341–355.

Mishra, S., & Modi, S. B. (2013). Positive and negative corporate social responsibility, financial leverage, and idiosyncratic risk. Journal of Business Ethics, 117, 431–448.

Munilla, L., & Miles, M. P. (2005). The corporate social responsibility continuum as a component of stakeholder theory. Business and Society Review, 110(4), 371–387.

Noda, T., & Bauer, J. L. (1996). Strategy making as iterated processes of resource allocation. Strategic Management Journal, 17, 159–192.

O’Reilly, C. A., Chatman, J., & Caldwell, D. F. (1991). People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person-organization fit. Academy of Management Journal, 34, 487–516.

Pagell, M., & Shevchenko, A. (2013). Why research in sustainable supply chain management should have no future. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 50(1), 44–55.

Peng, M. W. (2003). Institutional transitions and strategic choices. Academy of Management Review, 28(2), 275–296.

Peng, G. Z., & Beamish, P. W. (2014). MNC subsidiary size and expatriate control: Resource-dependence and learning perspectives. Journal of World Business, 49, 51–62.

Peng, M. W., Wang, D. Y., & Jiang, Y. (2008). An institution-based view of international business strategy: A focus on emerging economies. Journal of International Business Studies, 39, 920–936.

Perrini, F., Russo, A., & Tencati, A. (2007). Investigating stakeholder theory and social capital: CSR in large firms and SMEs. Journal of Business Ethics, 74, 285–300.

Pirsch, J., Gupta, S., & Grau, S. L. (2007). A framework for understanding corporate social responsibility programs as a continuum: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Ethics, 70, 125–140.

Reimann, F., Ehrgott, M., Kaufmann, L., & Carter, C. (2012). Local stakeholders and local legitimacy: MNEs’ social strategies in emerging economies. Journal of International Management, 18, 1–17.

Riaz, S., Rowe, W. G., & Beamish, P. W. (2014). Expatriate-deployment levels and subsidiary growth: A temporal analysis. Journal of World Business, 49, 1–11.

Russo, A., & Perrini, F. (2010). Investigating stakeholder theory and social capital: CSR in large firms and SMEs. Journal of Business Ethics, 91, 207–221.

Salomon, R., & Wu, Z. (2012). Institutional distance and local isomorphism strategy. Journal of International Business Studies, 43, 343–367.

Sen, S., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2001). Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. Journal of Marketing Research, 38, 225–244.

Shenkar, O. (2012). Cultural distance revisited: Towards a more rigorous conceptualization and measurement of cultural differences. Journal of International Business Studies, 43(1), 1–11.

Strike, V. M., Gao, J., & Bansal, P. (2006). Being good while being bad: Social responsibility and the international diversification of US firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 37, 850–862.

Suchman, M. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review, 20, 571–610.

Thornton, L. M., Brik, A. B., Autry, C. W., & Gligor, D. M. (2013). Does socially responsible supplier selection pay off for customer firms? A cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 49(3), 66–89.

Udayasankar, K. (2007). Corporate social responsibility and firm size. Journal of Business Ethics, 83, 167–175.

Vernon, R. (1998). In the hurricane’s eye: The troubled prospects of multinational enterprises. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Walter, I. (1982). Environmentally induced industrial relocation to developing countries. In S. J. Rubin & T. R. Grahamm (Eds.), Environment and trade. Allanheld: Osmun Publishers.

Xu, D., Pan, Y., & Beamish, P. W. (2004). The effect of regulative and normative distances on MNE ownership and expatriate strategies. Management International Review, 44(3), 285–307.

Xu, D., & Shenkar, O. (2002). Institutional distance and the multinational enterprise. Academy of Management Review, 27(4), 608–618.

Yang, X., & Rivers, C. (2009). Antecedents of CSR practices in MNCs’ subsidiaries: A stakeholder and institutional perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 86, 155–169.

Yiu, D., & Makino, S. (2002). The choice between joint venture and wholly owned subsidiary: An institutional perspective. Organizational Science, 13(6), 667–683.

Zaheer, S. (1995). Overcoming the liability of foreignness. Academy of Management Journal, 38(2), 341–363.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1: Questionnaire Scale Items

Appendix 1: Questionnaire Scale Items

MNE subsidiary’s strategic commitment to CSR |

In my country, our company |

…has defined measurable targets regarding social performance. (0.81) |

…puts social soundness in the center of its corporate branding. (0.83) |

…makes social sustainability an integral part of our business strategy. (0.93) |

…places a lot of top management attention on social issues. (0.88) |

Composite reliability: 0.886; coefficient α: 0.88; average variance extracted: 0.661 |

Eliminated items (reason for elimination): |

…positions itself as a leader regarding social innovations. (high internal correlation) |

Social pressure from government |

Government regulation in this country |

…currently sets strict social standards for my company. (0.83) |

…is likely to increase pressure if my industry does not improve socially by itself. (0.89) |

…actively pushes for social improvement in my industry. (0.91) |

…is expected to increase pressure regarding social efforts within the next 3 years. (0.85) |

Composite reliability: 0.89; coefficient α: 0.89; average variance extracted: 0.68 |

Eliminated items (reason for elimination): |

…is lobbied by activist groups to increase social standards for my industry. (high internal correlation) |

Social pressure from middle management |

The middle managers in our company |

…have started projects to enhance our company’s social performance. (0.84) |

…want our company to make a positive social contribution to the local community. (0.88) |

…speak up if they feel our company can improve socially. (0.85) |

Composite reliability: 0.82; coefficient α: 0.82; average variance extracted: 0.60 |

Eliminated items (reason for elimination): |

…show initiative to advance social causes. (high internal correlation) |

…show a personal sense of obligation toward social conduct. (high internal correlation) |

MNE subsidiary’s people orientation in organizational culture |

Organizational culture in your subsidiary |

Our company’s organizational culture is strongly characterized by |

…being people oriented. (0.76) |

…fairness. (0.88) |

…being supportive. (0.88) |

…the desire to be a good corporate citizen. (0.70) |

Composite reliability: 0.82; coefficient α: 0.81; average variance extracted: 0.53 |

Fit indices for overall measurement model: χ 2/df = 1.742; CFI = 0.965; GFI = 0.919; AGFI = 0.884; TLI = 0.956; RMSEA = 0.059 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reimann, F., Rauer, J. & Kaufmann, L. MNE Subsidiaries’ Strategic Commitment to CSR in Emerging Economies: The Role of Administrative Distance, Subsidiary Size, and Experience in the Host Country. J Bus Ethics 132, 845–857 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2334-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2334-1