Abstract

Because previous scholars have offered few comprehensive models to understand the benefits of corporate social responsibility image in terms of customer behaviour, the authors of this paper propose a hierarchy of effects model to study how customer perceptions of the social responsibility of companies influence customer affective and conative responses in a service context. The authors test a structural equation model using information collected directly from 1,124 customers of banking services in Spain. The findings demonstrate that corporate social responsibility image influences customer identification with the company, the emotions evoked by the company and satisfaction positively. Identification also influences the emotions generated by the service performance and customer satisfaction determines loyalty behaviour. The findings have significant implications for service managers because they demonstrate that there are two paths to explain the satisfaction and loyalty of service customers. The first path is composed of the beliefs and emotions generated by the company at the institutional level. The second path is composed of the thoughts, attitudes, emotions and feelings generated by the company’s services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Customer loyalty is a key goal for companies, especially when facing a tough economic situation such as the current global recession (Pérez et al. 2013a). In this context, customers are the most limited resource for companies and their loyalty directly affects their profits (Edvardsson et al. 2000). Along this line, scholars have demonstrated that building an appealing corporate image enables companies to enhance customer loyalty through repurchase and recommendation behaviour (Dick and Basu 1994; Chaudhuri and Holbrook 2001). Corporate image is a multidimensional construct that refers to the perceptions a group of stakeholders has of a company (Fombrun 1996). Scholars frequently divide its dimensions into corporate ability (CA) and corporate social responsibility (CSR) image (Brown and Dacin 1997). CA image refers to the perceptions of a company’s expertise and skills in producing and delivering product and service offerings, whereas CSR image refers to the perception and knowledge of a company’s activities and status relating to its societal and stakeholder obligations (He and Li 2011).

When it comes to understanding how these two dimensions of corporate image influence loyalty, scholars have traditionally devoted greater attention to analysing the effects of CA image on customer behaviour because these perceptions seem to have a closer connection with corporate profits and effective performances than CSR (Coelho and Henseler 2012). However, companies are under increasing pressure to enhance their social initiatives because CSR is a moral and ethical standard for contemporary society and because it has implications for customer behaviour and corporate performance (He and Li 2011). Thus, there is an important gap in literature that leaves practitioners with little guidance on how best to develop effective management and marketing strategies that correctly address CSR.

Furthermore, emotions and consumption affection are also central feelings in customer behaviour that however, scholars have not deeply studied in research analysing the role of CSR image. Researchers have mostly analysed the direct effect of CSR image on loyalty dimensions such as, for example, repurchase intentions (Berens et al. 2007; Bravo et al. 2009). However, the strategic importance of affective concepts (e.g. customer–company identification, emotions or satisfaction) as fundamental variables in relationship marketing perspectives makes their study an essential step forward in the knowledge of customers and their ways of acting.

Taking into account the arguments presented, in this paper the authors try to go into the study of CSR image and its relation to loyalty in depth. Following the proposals of the hierarchy of effects model (Lavidge 1961), the authors propose that the relationship between CSR image and customer loyalty is indirect and mediated by four affective variables: (1) customer–company identification, (2) customer emotions evoked by the company at the institutional level, (3) customer emotions evoked by the service performance and (4) satisfaction. Thus, the goals of the paper are twofold. First, the authors aim to provide readers with further knowledge on the role that CSR image plays in the construction of customer loyalty. The study of CSR image in customer behaviour is a line of research that is clearly underdeveloped if compared to the study of CA perceptions (Coelho and Henseler 2012). Secondly, the authors aim to identify the mediating role of four affective variables in the CSR image—loyalty link. In this regard, the four affective concepts proposed in this paper have been extensively analysed in relation to customer behaviour in many industries (San Martín 2005). However, their study in relation to CSR image is still in an initial phase and even some of the concepts have not been included in CSR models yet (e.g. emotions).

Based on these ideas, the originality of this paper lays in the study of new affective variables in the research of the consequences of CSR image in customer behaviour. These new affective variables are (1) customer emotions evoked by the company at the institutional level and (2) customer emotions evoked by the service performance. At the same time, the authors provide a comprehensive model to understand the benefits of CSR image for service companies, which extends previous findings in academic literature. The few previous scholars who have analysed the effects of CSR image in service customer behaviour have traditionally tested partial models that have mostly studied the direct link between CSR image and loyalty, while they have overlooked the mediating role of affection (García de los Salmones et al. 2005; Bravo et al. 2009).

The authors structure the remaining of the paper as follows. The paper starts with the presentation of the theoretical proposals of the hierarchy of effects model and the development of the conceptual framework of the research. The method section includes the description of the sample and the measurement scales. Thereafter, the authors discuss the results of the study. The final section of the paper covers the managerial implications, limitations of the study and future lines of research.

Conceptual Background

The Hierarchy of Effects Model

The authors build the conceptual framework of this paper on the principles of the hierarchy of effects model (Lavidge 1961). This approach considers that customers do not change instantaneously from disinterested people to convinced buyers. Instead, customers approach purchases through a multi-stage process, of which the purchase itself is the final step (Madrigal 2001). Lavidge (1961) divides the stages of customer behaviour into (1) the cognitive dimension, which refers to customer thoughts and beliefs, (2) the affective dimension, referring to the realm of emotions and (3) the conative dimension, referring to customer behavioural intentions and actions.

Companies communicate their CSR initiatives primarily through what Lavidge (1961) calls 'image advertising', which especially focus on the steps of generating attitudes and feelings rather than directly accessing the stage of conative behaviour. In this cognitive–affective–conative sequence, CSR image is a set of beliefs that determine corporate image. In turn, they determine affective responses from customers because of the cognitive effort to assess the company in relation to the cost of being its customer. Finally, these affective responses affect customer conative or behavioural outcomes, such as recommendation and repurchase behaviours.

The hierarchy of effects model has been generally applied to the study of customer responses to advertising (Lavidge 1961), in which the role of company–CSR fit, motivational attribution and corporate credibility are important issues to evaluate (Rifon et al. 2004; Becker-Olsen et al. 2006; Bigné et al. 2012; Robinson et al. 2012). For example, Bigné et al. (2012) demonstrate that the search for social causes that are functionally related to the company is the most direct route towards effective advertising in terms of CSR image, as it does not require the activation of the antecedents of CSR image (motivational attribution and credibility) by customers. Furthermore, these scholars demonstrate that, along with the functional fit, the symbolic fit (or coherence) between the company and the sponsored cause is a key element for achieving affective advertising. Similar results are obtained by Rifon et al. (2004) and Becker-Olsen et al. (2006) who demonstrate the value of a company’s involvement in sponsoring CSR initiatives that are perceived by customers as (1) consistent with core business activities and products (company–CSR fit), (2) altruistic in nature (motivational attribution) and (3) credible (corporate credibility). Along this line, Robinson et al. (2012) also demonstrate that customer choice in the CSR context is helpful as long as it increases customers’ perception of their personal role in helping the cause. Specifically, allowing customers to select the cause in a CSR campaign is more likely to enhance the perceived personal role and thus, purchase intentions (1) for those customers who are high (vs. low) in collectivism and (2) when the company and causes have low (vs. high) fit.

Nonetheless, all these papers present two common limitations in terms of the generalizability of their results. First, in all the cases, the scholars have designed research methods based on laboratory experiments, so the perceptions of customers in a real market context are not evaluated. In a lab experiment, the effectiveness of corporate CSR advertising, company–CSR fit, motivational attribution and corporate credibility might be biased because customers are being presented with different advertisements where the CSR message might be over stressed. Secondly, previous scholars have limited their analyses of CSR image to cause-related marketing (CrM) and sponsorship contexts (Rifon et al. 2004; Becker-Olsen et al. 2006; Bigné et al. 2012; Robinson et al. 2012). Nevertheless, CSR in a service industry (such as the banking industry that is analysed in this paper) includes a wide array of initiatives that go far beyond CrM and sponsorship. Recent literature points to the adequacy of stakeholder theory to understand the structural dimension of CSR image in a service industry (Pérez and Rodríguez del Bosque 2012). For example, Sarro et al. (2007) consider that the CSR initiatives of banking companies cover their corporate commitment to diverse stakeholders such as shareholders, customers, governments, suppliers and the local community. Pérez and Rodríguez del Bosque (2012) also demonstrate that this structure reflects how companies are managing and communicating their CSR initiatives. The most salient stakeholders identified in the banking industry are shareholders, customers, employees and the community (Pérez et al. 2013b). CSR initiatives move from information transparency to profit maximization, environmental protection or family conciliation, among other responsibilities (Pérez et al. 2013b).

In order to overcome these limitations, the authors of the present paper aim to apply the hierarchy of effects ideas to a real consumption context where the antecedents of CSR perceptions (company–CSR fit, motivational attribution and corporate credibility) are not controlled, and the results are expanded far from a one-dimensional perspective of CSR image (CrM or sponsorship). In this research, CSR is defined as a global concept, including issues such as those proposed in the stakeholder theory (Freeman 1984). In doing so, the authors follow the ideas of the latest works developed in the context of customer responses to CSR image, which do not take into consideration corporate advertising to evaluate the positive effects of CSR in service industries (García de los Salmones et al. 2009; McDonald and Lai 2011; Pérez et al. 2013a). In this paper, the real customer perceptions of CSR are being collected. Thus, if the statistical test carried out in this research confirm the hypotheses that are proposed in this paper, an additional contribution of the study will be the validation of the hierarchy of effects model regardless of the message content or communication tools used by companies.

Along this line, previous scholars analysing the direct effect of CSR image on customer loyalty in real service industries have obtained mixed findings (McDonald and Lai 2011). However, the authors observe that when scholars introduce mediating affective variables in the study (e.g. customer–company identification, satisfaction), CSR image always has an impact on customer loyalty (García de los Salmones et al., 2009; Pérez et al. 2013a). Thus, it seems that the hierarchy of effects model is more appropriate to understand the effects of CSR image on customer responses in the service industry than the study of direct connections between the cognitive and behavioural phases of the hierarchy of effects model (Beatty and Kahle 1988; Madrigal 2001). As explained by Currás et al. (2009), this might be so due to the inherent complexity of the CSR image construct. Also because of the relatively high degree of perceived risk associated with services, the competitive advantages resulting from pursuing CSR may not be as direct as the positive reactions of customers to other corporate associations such as service quality or relational benefits, among others (Hsu 2012).

Conceptual Model

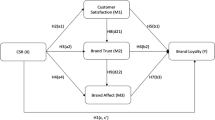

Most frequently, scholars consider three positive outcomes of CSR image in the service industry. These outcomes are: customer–company identification (García de los Salmones et al. 2009; Marín et al. 2009; Pérez et al. 2013a), satisfaction (Bravo et al. 2009; García de los Salmones et al. 2009; Matute et al. 2011; Pérez et al. 2013a) and loyalty (Bravo et al. 2009; McDonald and Lai 2011). In this paper, the authors propose a comprehensive conceptual model (Fig. 1) that following the hierarchy of effects philosophy, integrates the relationships among all these concepts. The authors also include two additional variables that the scholars have not applied to the study of the effects of CSR image yet: the emotions experienced by customers when evaluating a company and the service provided. The originality of the proposal lies in two facts. First, this is one of the few integrative models for the study of customer responses to CSR image in the service industry (García de los Salmones et al. 2009; He and Li 2011; Pérez et al. 2013a). Previous scholars have either concentrated on tangible products (Brown and Dacin 1997; Sen and Bhattacharya 2001) or they have only provided partial frameworks where few of these variables are combined and explained integratively (Berens et al. 2007; Bravo et al. 2009). Secondly, the authors include the study of customer emotions, a variable that scholars have never applied to the study of the effects of CSR image so far. Nonetheless, scholars demonstrate that among all the concepts that influence customer behaviour, emotions are immediate and closely related to the cognitive stimuli that influence affection (Bagozzi et al. 1999), and as so its inclusion in the conceptual model proposed in this paper is justified.

Figure 1 represents the conceptual model of the paper. A justification of the relationships among all the concepts is included next.

According to the hierarchy of effects model, the affective stage of customer behaviour begins with the evocation of feelings based on the perception of the company (Lavidge 1961). In this regard, customer–company identification refers to a psychological state of connection or proximity between a customer and a company that derives from the identification of a substantial overlap between the customer’s perception of their personal identity and their perception of the identity of the company (Lichtenstein et al. 2004). According to the social identity and the self-categorization theories (Tajfel and Turner 1979), customers classify themselves into a multitude of social categories to which they feel a sense of belonging through self-definition. To the extent that customers view the characteristics of a company as consistent with the norms, values and definitions that reflect their self-concepts, this perceived overlap would enhance their self-esteem and increase their customer–company identification (Scott and Lane 2000).

Along this line, CSR image has a direct and positive effect on the identification of the customer with their company (García de los Salmones et al. 2009; Marín et al. 2009; Pérez et al. 2013a). In this regard, scholars consider that customer–company identification is one of the most influential variables in the decision-making process of service customers, especially because it helps to explain the importance of CSR image to generate customer loyalty towards companies (Pérez et al. 2013a). CSR image acts as a transceiver of a differentiated system of values, and it supports the appeal of corporate identities (Turban and Greening 1997). Customers will only identify with those companies whose identity looks attractive to them; because they perceive them close to theirs and they share common values and principles (Scott and Lane 2000). Accordingly, CSR image strengthens customers’ feelings of identification towards companies and induce them to develop a sense of connection with them (García de los Salmones et al. 2009; Matute et al. 2011). Based on these ideas, the authors propose the first research hypothesis of the paper:

H1

CSR image directly and positively influences customer–company identification.

Furthermore, scholars define emotions as a form of affection involving visceral responses that are associated with a specific referent, and result in action (Chaudhuri and Holbrook 2001). Emotions have a largely intensive valence (positive or negative) accompanied by expressive manifestations and derived from cognitive stimulus (Frijda 1986). Practitioners have traditionally neglected the emotional and affective component of their companies, focusing on their rational and functional constituents. Nonetheless, in this paper, the authors propose that customers may experience emotions when dealing with their service companies because brands and products have become sources of experiences and as so all touch points with customers are key in the management of the relationships with them.

Following the line of investigation initiated by Brown and Dacin (1997), the authors also propose to identify two major sources of customer emotions: the company itself and its services. Specifically, Brown and Dacin (1997), based on the propositions of classical brand theories, argue that corporate image can have different effects on customers’ evaluation of the company, on the one hand, and its products/services, as another important concept in the cognitive structure of the customer. In their empirical study, these scholars show that while assessments of the company and its products/services are closely related, customers arrive at their evaluation through different processes, assimilating information on CSR and corporate ability in different ways. Along this line, Brown (1998) also clearly differentiates between customer responses to the company and its products/services as a direct result of different corporate images, including CSR. Various authors, such as Sen and Bhattacharya (2001), have supported this dichotomy. Therefore, it is logical to assume that affective responses to companies and services may be different. Accordingly, it is necessary to analyse the specific role that CSR image plays in the formation of each of these types of emotions and their potential consequences on the customer’s subsequent responses.

Concerning the theories that analyse the role of emotions in customer behaviour, first the authors of the paper resort to the cognitive theory (Tsal 1985) to propose that CSR image positively influences customer emotions evoked by the company under scrutiny. The cognitive theory suggests that customer emotions do not arouse unless there is a previous cognitive evaluation, albeit unconscious or irrational, of the potential source of emotions (Frijda 1986). In addition, although customer emotions have not been analysed in the context of CSR image so far, their relevance is justified by the results of previous scholars analysing the role of CSR image in the formation of customer company and product responses (Brown and Dacin 1997; Sen and Bhattacharya 2001). In this regard, scholars have demonstrated that CSR image does not directly influence the intentions of customers to repurchase products. On the contrary, they are more suitable to provide a general context through which customers subjectively assess companies by means of their affective responses (Brown and Dacin 1997). Sen and Bhattacharya (2001) argue that positive evaluations of companies derive from CSR image because they trigger emotional reactions in the customer’s mind. Based on these ideas, the authors propose that:

H2

CSR image directly and positively influences the emotions evoked by the company.

The authors also propose that CSR image influences the emotions evoked by the performance of the service provided by companies. In this regard, scholars have demonstrated that customers do not buy services exclusively for their functionality. They also buy them based on their symbolic meanings, and their attitude towards the brand (Levy 1999). As a result, scholars are increasingly interested in understanding the nature of the emotional side of services and their contribution to customer’s decision making and responses to marketing variables (Westbrook 1987). Mano and Oliver (1993) develop an empirical model that connects the classic aspects of service evaluation (utilitarian and hedonic judgement) and the emotions that the service evokes (pleasantness and arousal) to determine overall customer satisfaction. The results show that the assessment of utilitarian and hedonic attributes determines the emotions aroused by the service that ultimately are those that strongly determine customer satisfaction. Along this line, Brown and Dacin (1997) propose that there is a clear relationship between CSR image and service evaluation, mediated by the customer’s overall assessment of the company. Berens et al. (2005) propose a more direct relationship between CSR and service evaluation, suggesting that CSR image influences the customer’s attitude towards a service. Finally, García de los Salmones et al. (2005) argue that although it is true that the role of CSR may be indirect in the tangible product market, CSR has a much clearer and decisive role in the service market. Thus, scholars understand CSR as a part of the social image of the service (Sureshchandar et al. 2002) that helps the company to convey trust and determines the customer’s evaluation of the service. According to these ideas, a new research hypothesis is proposed:

H3

CSR image directly and positively influences the emotions evoked by the service.

Several studies have also emphasised the importance of an attractive corporate identity and its similarity to the customer’s identity in shaping customer’s attitudes and choices (Bhattacharya and Sen 2003). Eagly and Chaiken (1993) suggest that emotions link to each other through cognitive structures, so that the affection that a concept awakens in the person’s mind transfers to another through the connections that the customer establishes between them. Regarding the study of customer–company identification, customers may tend to experience positive feelings towards those issues consistent with distinctive aspects of their own identity, leading them to support companies that display similar identities (Ashforth and Mael 1989). Thus, there is affection transference, and this identification positively influences the customer’s feelings about the company (Madrigal 2001). Similarly, Freud (1985 in Carr 2001) believes that to interpret a customer’s emotional response to any stimulus, scholars may understand that emotions link closely to the development of the individual’s identity. Thus, personal identity not only becomes the main source of emotion but also helps to explain its strength, intensity and robustness (Carr 2001). Customers form their personal identity mainly from their process of identifying with other elements of the environment laden with emotional content. According to Carr (2001), scholars should understand customer–company identification as the first expression of an emotional bond with the company. Thus, a new research hypothesis reads as follows:

H4

Customer–company identification directly and positively influences the emotions evoked by the company.

According to Bhattacharya and Sen (2003), because the act of consumption is the primary relationship between customers and the company, identification represents a personal commitment manifested through a continuous customer preference for the company’s services. Therefore, the authors expect that a customer who identifies with a company also experience more positive emotions when evaluating the company’s services. This would be a way to support their decision to become a customer of the company. Additionally, the emotions evoked by a company may extend to its entire suite of services because corporate image allows the customer to infer their characteristics when they do not fully known their attributes or when there is a dominance of the corporate brand on the product brand (García de los Salmones 2002). Thus, the internal aspects that enable customers to experience emotions with regard to a company also allow them to experience similar feelings about its offerings. If scholars define the relationship between the customer and the company primarily through the act of consumption, its services will be able to evoke emotions, which will partly be conditioned by the customer–company relationship. Based on these ideas, the authors propose that:

H5

Customer–company identification directly and positively influences the emotions evoked by the service.

It is also known that the service sector is highly uncertain for customers because their characteristics prevent them from having complete information on which to base their purchase decisions (García de los Salmones 2002). In these cases, customers tend to make inferences from corporate image to form an opinion of the service (García de los Salmones 2002). For example, the reputation of a company is a good indicator of its capabilities and facilitates economic transactions within an uncertain environment (Vendelo 1998). Moreover, the credibility and clarity of a brand indicate the position of the service, which can increase its perceived quality and reduce information costs and the risk perceived by the customer (García de los Salmones 2002). Furthermore, the transfer of the company’s image to the service also occurs when there is a dominance of the corporate brand on the service brand. García de los Salmones (2002) postulates that when the name of the company is the most noticeable between the two attributes, there is a maximum effect of the interaction between service image and corporate image, and the purchase choice depends more on the overall evaluation of the company (Low and Lamb 2000).

In both cases, multiple studies have shown that corporate image may positively affect customers’ judgments and responses to services (Belch and Belch 1987; Brown and Dacin 1997). Brown (1998), for example, suggests that the association of a service with a company always produces a transfer of affection from the company to the service through the halo effect or an adjustment process. Maathuis et al. (1998) believe that when the consistency of the service with the company’s overall catalogue is high, corporate value easily transfers to the service. When the fit is low, corporate image has less effect on service preference. However, even in this case, corporate credibility determines the credibility of its offerings. Ind (1998) suggests that a good fit between corporate brand and product is desirable because a good corporate image is fundamental to building the service’s credibility. Thus, a company that uses a 'single brand' strategy, as it is usually the case for services, should convey a wealth of corporate information to the customer with a view towards adding positive associations to the brand strategy, ultimately improving the possibility of extending these associations to its services. Based on these ideas, the authors propose that:

H6

The emotions evoked by the company directly and positively influence the emotions evoked by the service.

Satisfaction is also a key variable for service customers, which mediates the impact of corporate images on customer loyalty behaviours (Bravo et al. 2009; Matute et al. 2011). In this context, scholars define satisfaction as the attitude of the customer towards a company because of the cognitive effort to assess the service received in relation to its costs.

Based on the findings of previous scholars, the authors identify three streams of research to link CSR image to satisfaction (Luo and Bhattacharya 2006; Hsu 2012; Pérez et al. 2013a). First, the equity theory (Oliver 1999) argues that customers can be potentially other types of stakeholders who care not only for the economic value of consumption but also for the overall standing of a company, including the fairness of its CSR initiatives towards different stakeholder groups. When this is the case, customers are likely to be more satisfied if the company is socially responsible (Luo and Bhattacharya 2006). In addition to this, even when customers are not part of other stakeholder groups, CSR image demonstrates corporate equity and fairness towards customers, leading to higher satisfaction. Second, CSR image increases the perceived utility and value of a company, which in turn enhances customer satisfaction. In this regard, perceived value can take both economic and non-economic forms and as so CSR image can add extra benefits/utilities to customers and increase their satisfaction (He and Li 2011). Finally, scholars have demonstrated that CSR image can be a major determinant to perceived attractiveness of a company’s identity, which in turn enhances the strength of customer–company identification (Marín et al. 2009). Along this line, scholars have demonstrated that highly identified customers are more likely to be satisfied with their services providers in such a way that even a direct connection between CSR image and satisfaction might exist (He and Li 2011). Based on these ideas, the authors propose that:

H7

CSR image directly and positively influences customer satisfaction.

One research venue resulting from the application of the cognitive-affective approach has traditionally maintained that satisfaction is another emotional state, theoretically indistinguishable from emotion (Watson and Tellegen 1985). However, arguing against this opinion, Oliver (1997) suggests that the placement of satisfaction in customer behaviour models has a high variability, while its possible connection to other emotions is inconsistent and appears casual. Therefore, the author argues that emotions are a component of experience that contributes, along with cognitive judgments, to customer satisfaction. From this perspective, satisfaction is a customer response to a set of cognitive and emotional antecedents rather than an emotion itself (San Martín 2005). Along this line, several studies have indicated the importance of emotions as direct determinants of customer satisfaction (Bigné and Andreu 2004). In this regard, the affective approach to forming satisfaction primarily supports the distinction between emotion and satisfaction, and defines the latter as the result of the process of evaluating the emotions experienced over the duration of the relationship with the company (da Silva and Alwi 2006; Bravo et al. 2009). These emotions leave affective traces in customers’ memory, which they include in their value judgments (Szymanski and Henard 2001). Subsequently, positive or negative emotions directly affect satisfaction ratings, ultimately prompting more specific behaviours such as complaints or word-of-mouth (Bigné and Andreu 2004; da Silva and Alwi 2006).

The necessity of including the emotions satisfaction relationship in the study also stems from the analysis of multiple studies that show the important role of emotions as mediators of the relationship between cognitive judgments, CSR image in this research, and customer satisfaction (Wirtz and Bateson 1999; da Silva and Alwi 2006). In this regard, da Silva and Alwi (2006), one of the closest studies to the proposal of this paper, shows that the emotional aspects evoked by a brand, also called corporate branding value, mediate the effect of the brand’s functional aspects on customer loyalty. Thus, a new hypothesis reads as follows:

H8

The emotions evoked by the company directly and positively influence customer satisfaction.

Scholars suggest that the emotions experienced during a service provision leave affective traces in memory that the customer retrieves later when valuing their satisfaction (Szymanski and Henard 2001). Mano and Oliver (1993) suggest that there are strong interconnections between the satisfaction with a service and the emotions experienced in its use. Therefore, there is a certain overlap in the processes underlying consumer emotion and satisfaction (Westbrook 1987). In Oliver’s (1997) view, positive emotions are both an antecedent of and a necessary condition for satisfaction. Hunt (1977) argues that satisfaction derives from the affective processing of the customer experience.

In addition, the authors also highlight the empirical results found by Mano and Oliver (1993), Westbrook (1987) and Westbrook and Oliver (1991). For example, Westbrook (1987) confirms that emotions, both positive and negative, underlie customer satisfaction derived from contact with a service, and that their influence extends to complaints and word-of-mouth communication among customers. Westbrook and Oliver (1991) extend these results to more complex emotional experiences such as hostility (negative emotion), pleasant surprise (positive emotion) and interest (positive or negative emotion). Similarly, Oliver (1997) considers emotions as components of consumption, which results from both irrational emotions, as well as cognitive appraisals. Moreover, this affect coexists alongside various cognitive judgments to produce satisfaction. Other studies that confirm these hypotheses include those of Price et al. (1995) and Wirtz and Bateson (1999). Thus, the authors propose the following hypothesis:

H9

The emotions evoked by the service directly and positively influence customer satisfaction.

Finally, the authors include an extensively accepted relationship to complete the hierarchy of effects model described in this paper. Specifically, a direct and positive link between customer satisfaction and customer loyalty is proposed. This hypothesis has been extensively confirmed in the context of CSR image in the service industry (García de los Salmones et al. 2009; Bravo et al. 2009; Matute et al. 2011; Pérez et al. 2013a). Thus, the last hypothesis reads as follows:

H10

Customer satisfaction directly and positively influences loyalty.

Methodology

For the testing of the hypotheses, the authors conducted a quantitative study based on the personal surveys on customers of banks in Spain. Customers filled up the surveys in in-depth interviews. Customers only had to evaluate their main banking company. Thus, the authors gathered the information for different banks and as so, they can generalize the results of this research to the universe of banks in the country. After the collection and processing of information, 1,124 valid surveys remained (response rate = 93.7 %).

Sample Profile

The authors used a non-probabilistic sampling procedure to design the research sample. With the purpose of guaranteeing a more accurate representation of the data, they used a multi-stage sampling by quotas based on customer gender and age. The sample was 48.67 % male and 51.33 % female, which was comparable to the population in the country (50.97 % male and 49.03 % female). Regarding age, 46.54 % were young customers (under 35) (50.14 % in the national population), while 53.46 % were mature customers who were 35 years of age or older (49.86 % in the national population). The sample was slightly more educated than the population (36.57 vs. 13.55 % of customers with college degrees, respectively).

Measurement Scales

The authors evaluated CSR image by adopting the reflective stakeholder-based scale proposed by Pérez et al. (2013b). Twenty-two items were included in the scale and gathered in five dimensions: customers, shareholders, employees, community and a general dimension concerning legal and ethical issues, which included corporate responsibilities towards a broad array of stakeholders. Pérez et al. (2013b) provide a detailed explanation of the development of the scale. The authors measured customer–company identification by means of a six-item scale based on the paper of Bergami and Bagozzi (2000). To measure customer emotions (derived from the institutional evaluation of the company and the evaluation of the service), the authors applied two four-item scales adapted from the bipolar perspective of Holbrook (1981). The authors conceived satisfaction as the evaluative judgment (cognitive, affective or mixed) made by a customer through various stages of the relationship with their banking company. They developed a four-item scale based on Oliver (1999). Finally, the authors also measured customer loyalty following the proposal of Oliver (1999) and using a two-item scale (Table 1).

Results

To test the research hypotheses, the authors test a Structural Equation Model (SEM) with Maximum Likelihood Robust estimation including all the variables previously described in the paper. First, the authors perform a first-order Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to evaluate the reliability and validity of the measurement scales. Once they validate the measurement model, they test the conceptual model.

Table 2 presents the results of the first-order CFA. The results confirm that the Satorra–Bentler Chi square is significant (S–Bχ 2 = 1,869.84, P < 0.01), which may indicate a poor fit of the model to the collected data. However, this result may be due to the large sample size in the study, which potentially affects the Satorra–Bentler Chi square test. Consequently, the authors complement this indicator with an analysis of the Comparative Fit Indexes. In all the cases, these measures exceed the minimum recommended value of 0.90, thus confirming the goodness of fit of the measurement model (NFI = 0.91; NNFI = 0.92; CFI = 0.93; IFI = 0.93). The authors evaluate the reliability of the measurement scales by means of the Cronbach’s alpha (α), the Composite Reliability (CR) and the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) Index. In all the cases, these indicators are over the recommended values of 0.7, 0.7 and 0.5, respectively. The convergent validity of the scales is also contrasted, since the t statistic reveals that all the items are significant to a confidence level of 95 %, and their standardized lambda coefficients are higher than 0.5. In order to test the discriminant validity of the measurement scales, the authors use the procedure suggested by Fornell and Larcker (1981). The results also verify the discriminant validity of the model because, when compared in pairs, the AVE estimates of the variables under scrutiny exceed the squared correlation between the variables.

Table 3 presents the results of the SEM estimation by the robust method. Once again, the results confirm that the Satorra-Bentler Chi square is significant (S–Bχ 2 = 2,059.69, P < 0.01) but the Comparative Fit Indexes exceed the minimum recommended value of 0.90 (NFI = 0.90; NNFI = 0.91; CFI = 0.92; IFI = 0.92). These results support the goodness of fit of the SEM. As far as the relationships among variables is concerned, the analysis indicates that there is a significant and positive relationship between CSR image and (1) the emotions evoked by the company (β = 0.07, P < 0.05); (2) customer–company identification (β = 0.53, P < 0.05) and (3) satisfaction (β = 0.42, P < 0.05). Thus, the results support the Hypotheses H1, H2 and H7. Nonetheless, the relationship between CSR image and the emotions evoked by the service is not significant (β = 0.00, P > 0.05) and this finding does not support the hypothesis H3. The results also indicate that there is a significant and positive relationship between customer–company identification and (1) the emotions evoked by the company (β = 0.67, P < 0.05) and (2) the emotions evoked by the service (β = 0.07, P < 0.05) and as so the hypotheses H4 and H5 are supported. There is also a significant relationship between the emotions evoked by the company and the service (β = 0.83, P < 0.05). Thus, this result supports the hypothesis H7. Customer satisfaction is also directly and positively influenced by (1) the emotions evoked by the company (β = 0.49, P < 0.05) and (2) the emotions evoked by the service (β = 0.27, P < 0.05). Thus, the findings support the hypotheses H8 and H9. Finally, the results demonstrate that loyalty behaviour is directly and positively influenced by customer satisfaction (β = 0.82, P < 0.05) and as so the hypothesis H10 is supported.

Because the hierarchy of effects model presented in this paper proposes that the effect of the CSR image on customer loyalty is indirect and mediated by identification, emotions and satisfaction, the authors also calculate the indirect and total effects among the variables in the study. For this purpose, the authors apply the procedure previously used by Currás et al. (2009) and Herrero and San Martín (2012). The results of this analysis are presented in Table 4. The results demonstrate that the CSR image has a large and positive effect also on customer loyalty (β TE = 0.58), even though the effect is indirect and mediated by customer–company identification, the emotions evoked by the company, the emotions evoked by the service performance and satisfaction. The largest impact of CSR image is on customer satisfaction (β TE = 0.72), while it has the lowest effect on the emotions evoked by the service performance (β TE = 0.38) and the company at the institutional level (β TE = 0.42). In this regard, the mediating effects of customer–company identification and emotions make of the CSR image the most relevant variable when determining customer satisfaction with their banking providers, ahead of the emotions evoked by the company (β TE = 0.71), customer–company identification (β TE = 0.50) and the emotions evoked by the service performance (β TE = 0.27). It is also observed that when planning their loyalty behaviour, customer especially resort to their satisfaction feelings (β TE = 0.82), but that the CSR image of their banking providers is gaining attention and it is the second most important factor when deciding their recommendation and repurchase behaviours.

Conclusions, Managerial Implications, Limitations and Future Lines of Research

The results presented in this paper confirm the validity of the hierarchy of effects model to understand the effects of CSR image on customer loyalty. Specifically, the cognitive associations concerning CSR directly influence some affective responses of customers such as their identification with the company, emotions at the institutional level and satisfaction. They also affect customer emotions derived from the service performance indirectly by increasing corporate emotions and the identification of customers with the company. Subsequently, this positive affect determines the behavioural loyalty of customers. These results contribute to literature by complementing and completing the studies carried out previously in the service industry (Bravo et al. 2009; García de los Salmones et al. 2009; Marín et al. 2009; Matute et al. 2011; McDonald and Lai 2011). In this regard, thus far scholars had not provided practitioners with comprehensive models to understand the links among CSR image, affective and behavioural customer reactions.

The most relevant conclusion of the paper involves two possible ways for companies to generate customer satisfaction and loyalty. The first path is composed of the beliefs and emotions generated by the company at the institutional level. The second path is composed of the thoughts, attitudes, emotions and feelings generated by the company’s services. The results demonstrate that CSR image has positive direct effects on the generation of emotions at the institutional level. However, its direct effect on the emotions evoked by the service performance is null. Nonetheless, the emotions based on the service are decisive in determining customer satisfaction, so the aspects most closely linked to the banking service itself will also be essential to understand the process of building satisfaction and behavioural loyalty in a service context. These results are in line with previous studies, such as Brown and Dacin’s (1997) and Sen and Bhattacharya’s (2001) papers, which point to CSR image as a strategic concept that is more suitable for generating an overall evaluation of companies than arousing direct positive perceptions of service performances. Thereafter, this CSR image contributes to satisfaction and customer loyalty. This global context also helps to improve the evaluation of a company’s services, as confirmed by the significant influence of the emotions generated by the company in the evocation of emotions associated with the service, which are associated with a more renowned company that generates positive affect on the part of the customer.

The results also demonstrate how customer–company identification plays a key role in explaining the benefits of CSR image for companies. In this regard, it is observed that, even though the direct effect of CSR image is relatively low when arousing corporate emotions and insignificant for the generation of emotions derived from the service performance, the indirect effects mediated by customer–company identifications are notably higher. Nonetheless, it is again observed that both CSR image and customer–company identification are more effective for the generation of positive feelings at the institutional level, while this global context translates customer affect to the perception of service performances (Brown and Dacin 1997).

The findings concerning the low direct impact of CSR image on customer emotions contradict previous ideas presented in the academic literature, where several scholars argue that customer emotions are one of the immediate responses of customers when evaluating a cognitive stimulus such as CSR image (Bagozzi et al. 1999). The authors believe that this result is directly linked to the research context where their study has been implemented. Specifically, scholars such as Wirtz et al. (2000) have suggested that banking services cannot be considered exciting enough to trigger intense customer emotions. Emotions are frequently more evident in leisure industries such as hospitality or entertainment, among others (Wirtz et al. 2000). Furthermore, the latest crisis context of the banking industry has resulted in a loss of customer confidence in the financial system (and companies operating in it) and an increase in their social conscience, which takes them to demand better tools for the evaluation of corporate practices (KPMG 2011). In this context, it is logical that customers resort to previous experiences and verifiable facts when taking decisions such as the purchase of new services or the recommendation of banking companies. Accordingly, they would resort to their emotions less directly and they would prefer to base their decisions on additional affective variables such as their identification with service companies.

Along this line, a third relevant finding reveals that CSR image has the largest total effect on customer satisfaction. Furthermore, the direct effect of CSR image on satisfaction is greater than the indirect effect mediated by customer–company identification and emotions. These results contradict the findings of previous studies that have found no direct connection between CSR image and customer satisfaction (García de los Salmones et al. 2009; Bravo et al. 2009; Pérez et al. 2013a). The authors explain these results by resorting to the CSR definition used in this paper. CSR image includes dimensions of great importance to the customer, as all corporate obligations towards customers themselves—customer service, honesty, availability of information or satisfaction measures to improve service quality, among others—or all legal and ethical corporate requirements (Pérez and Rodríguez del Bosque 2012). It is, therefore, logical that those companies that can achieve a good image in these dimensions are a source of satisfaction for the customer.

The results presented in the paper have important managerial implications for banking and service companies. First, these results demonstrate the vital importance of CSR in the current business environment and the need for companies to include this concept in their management strategies and policies. The findings demonstrate that CSR is a key strategic tool, given its essential role in building customer satisfaction and loyalty. On the other hand, companies should try to combine the management of CSR issues with the efficient management of products and services, as these variables are a second major route for generating satisfaction, recommendations and repurchase behaviour.

Nonetheless, this study has some limitations that future scholars have to address. Specifically, the authors have not addressed possible differences in the CSR expectations among customers. Thus, it is not possible to determine whether different types of CSR image dimensions could have impacts on customer loyalty that are more positive than the others are. Previous scholars have revealed that some CSR dimensions (e.g. customer-centric CSR issues) are more important for customers than others (McDonald and Lai 2011). According to this idea, future scholars may want to analyse the role of each of the CSR dimensions on customer affective and conative responses independently. In addition, the authors also recommend that researchers propose models that combine CSR and CA images to understand customer behaviour better. In this paper, the authors have demonstrated that customers form their satisfaction and loyalty behaviour through a twofold process that includes information about the company, on the one hand, and its services, on the other. Thus, it is conceivable that the study of the effect of CSR image combined with CA image can contribute to a better understanding of the formation of satisfaction and customer loyalty. Brown and Dacin (1997) initiated this line of research and subsequent scholars have pursued it. Nonetheless, their studies provide partial or contradictory results (Sen and Bhattacharya 2001; García de los Salmones et al. 2005). Some of the variables that the authors propose for further study include functional and aesthetic attributes of products (Mano and Oliver 1993), service quality (García de los Salmones et al. 2005), product sophistication (Brown and Dacin 1997), product evaluation (Brown and Dacin 1997) and information quality (Sen and Bhattacharya 2001).

References

Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. The Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20–39.

Bagozzi, R. P., Gopinath, M., & Nyer, P. U. (1999). The role of emotions in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27(2), 184–206.

Beatty, S. E., & Kahle, L. R. (1988). Alternative hierarchies of the attitude–behavior relationship: The impact of brand commitment and habit. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(2), 1–10.

Becker-Olsen, K. L., Cudmore, B. A., & Hill, R. P. (2006). The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research, 59, 46–53.

Belch, G. E., & Belch, M. A. (1987). The application of an expectancy value operationalization of function theory to examine attitudes of boycotters and nonboycotters of a consumer product. Advances in Consumer Research, 14(1), 232–237.

Berens, G., van Riel, C. B. M., & van Bruggen, G. H. (2005). Corporate associations and consumer product responses: The moderating role of corporate brand dominance. Journal of Marketing, 69(3), 35–48.

Berens, G., van Riel, C. B. M., & van Rekom, J. (2007). The CSR-quality trade-off: When can corporate social responsibility and corporate ability compensate each other? Journal of Business Ethics, 74, 233–252.

Bergami, M., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2000). Self-categorization, affective commitment and group self-esteem as distinct aspects of social identity in the organization. British Journal of Social Psychology, 39, 555–577.

Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2003). Consumer–company identification: A framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. Journal of Marketing, 67(2), 76–88.

Bigné, E., & Andreu, L. (2004). Modelo cognitivo-afectivo de la satisfacción en servicios de ocio and turismo. Cuadernos de Economía and Dirección de la Empresa, 21, 89–120.

Bigné, E., Currás, R., & Aldás, J. (2012). Dual nature of cause-brand fit. Influence on corporate social responsibility consumer perception. European Journal of Marketing, 46(3/4), 575–594.

Bravo, R., Montaner, T., & Pina, J. M. (2009). The role of bank image for customers versus non-customers. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 27(4), 315–334.

Brown, T. J. (1998). Corporate associations in marketing: Antecedents and consequences. Corporate Reputation Review, 1(3), 215–233.

Brown, T. J., & Dacin, P. A. (1997). The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. Journal of Marketing, 61(1), 68–84.

Carr, A. (2001). Understanding emotion and emotionality in a process of change. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 14(5), 421–434.

Chaudhuri, A., & Holbrook, M. B. (2001). The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing, 65, 81–93.

Coelho, P. S., & Henseler, J. (2012). Creating customer loyalty through service customization. European Journal of Marketing, 46(3), 331–356.

Currás, R., Bigné, E., & Alvarado, A. (2009). The role of self-definitional principles in consumer identification with a socially responsible company. Journal of Business Ethics, 89, 547–564.

da Silva, R. V., & Alwi, S. F. S. (2006). Cognitive, affective attributes and conative, behavioural responses in retail corporate branding. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 15(5), 293–305.

Dick, A. S., & Basu, K. (1994). Customer loyalty: Toward an integrated conceptual framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 22(2), 99–113.

Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace & Jovanovich.

Edvardsson, B., Johnson, M. D., Gustafsson, A., & Strandvik, T. (2000). The effects of satisfaction and loyalty on profits and growth: Products versus services. Total Quality Management, 11(7), 917–927.

Fombrun, C. (1996). Reputation. Realizing value from the corporate image. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Boston: Pittman.

Frijda, N. H. (1986). The emotions. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

García de los Salmones, M. M. (2002). La imagen de empresa como factor determinante en la elección de operador: Identidad and posicionamiento de las empresas de comunicaciones móviles. Doctoral Thesis, Universidad de Cantabria.

García de los Salmones, M. M., Herrero, Á., & Rodríguez del Bosque, I. (2005). Influence of corporate social responsibility on loyalty and valuation of services. Journal of Business Ethics, 61(4), 369–385.

García de los Salmones, M. M., Pérez, A., & Rodríguez del Bosque, I. (2009). The social role of financial companies as a determinant of consumer behaviour. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 27(6), 467–485.

He, H., & Li, Y. (2011). CSR and service brand: The mediating effect of brand identification and moderating effect of service quality. Journal of Business Ethics, 100, 673–688.

Herrero, Á., & San Martín, H. (2012). Developing and testing a global model to explain the adoption of websites by users in rural tourism accommodations. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(4), 1178–1186.

Holbrook, M. B. (1981). Integrating compositional and decompositional analyses to represent the intervening role of perceptions in evaluative judgments. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 13–28.

Hsu, K. (2012). The advertising effects of corporate social responsibility on corporate reputation and brand equity: Evidence from the life insurance industry in Taiwan. Journal of Business Ethics, 109, 189–201.

Hunt, H. K. (1977). CS/D—overview and future research directions. In H. K. Hunt (Ed.), Conceptualization and measurement of consumer satisfaction and dissatisfaction. Cambridge, MA: Marketing Science Institute.

Ind, N. (1998). The company and the product: The relevance of corporate associations. Corporate Reputation Review, 2(1), 88–92.

KPMG. (2011). KPMG international survey of corporate responsibility reporting 2011. Available on-line http://www.kpmg.com.

Lavidge, R. J. (1961). A model for predictive measurements of advertising effectiveness. Journal of Marketing, 25(6), 59–62.

Levy, S. J. (1999). Imagery and symbolism (1973). In D. W. Rook (Ed.), Brands, consumers, symbols & research: Sidney J. Levy on marketing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Lichtenstein, D. R., Drumwright, M. E., & Braig, B. M. (2004). The effect of corporate social responsibility on customer donations to corporate-supported nonprofits. Journal of Marketing, 68(4), 16–32.

Low, G. S., & Lamb, C. W, Jr. (2000). The measurement and dimensionality of brand associations. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 9(6), 350–368.

Luo, X., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2006). Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. Journal of Marketing, 70(4), 1–18.

Maathuis, O. J. M., van Riel, C. B. M., & van Bruggen, G. H. (1998). Using the corporate brand to communicate identity: The value of organizational associations. II International conference on corporate reputation, identity and competitiveness.

Madrigal, R. (2001). Social identity effects in a belief–attitude–intentions hierarchy: Implications for corporate sponsorship. Psychology & Marketing, 18(2), 145–165.

Mano, H., & Oliver, R. L. (1993). Assessing the dimensionality and structure of the consumption experience: Evaluation, feeling, and satisfaction. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(3), 451–466.

Marín, L., Ruiz, S., & Rubio, R. (2009). The role of identity salience in the effects of corporate social responsibility on consumer behaviour. Journal of Business Ethics, 84, 65–78.

Matute, J., Bravo, R., & Pina, J. M. (2011). The influence of corporate social responsibility and price fairness on customer behaviour: Evidence from the financial sector. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 18, 317–331.

McDonald, L. M., & Lai, C. H. (2011). Impact of corporate social responsibility initiatives on Taiwanese banking customers. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 29(1), 50–63.

Oliver, R. L. (1997). Satisfaction: A behavioral perspective on the consumer. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Oliver, R. L. (1999). Whence consumer loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 63, 33–44.

Pérez, A., & Rodríguez del Bosque, I. (2012). Corporate Social Responsibility image in a financial crisis context: The case of the Spanish financial industry. Universia Business Review, 33(first quarter), 14–29.

Pérez, A., García de los Salmones, M. M., & Rodríguez del Bosque, I. (2013a). The effect of corporate associations on consumer behaviour. European Journal of Marketing, 47(1/2), 218–238.

Pérez, A., Martínez, R. P., & Rodríguez del Bosque, I. (2013b). The development of a stakeholder-based scale for measuring corporate social responsibility in the banking industry. Service Business, 7(3), 459–481.

Price, L. L., Arnould, E. J., & Tierney, P. (1995). Going to extremes: Managing service encounters and assessing provider performance. Journal of Marketing, 59(2), 83–97.

Rifon, N. J., Choi, S. M., Trimble, C. S., & Li, H. (2004). Congruence effects in sponsorship: The mediating role of sponsor credibility and consumer attributions of sponsor motive. Journal of Advertising, 33, 29–42.

Robinson, S. R., Irmak, C., & Jayachandran, S. (2012). Choice of cause in cause-related marketing. Journal of Marketing, 76(4), 126–139.

San Martín, H. (2005). Estudio de la imagen de destino turístico and el proceso global de satisfacción: Adopción de un enfoque integrador. Doctoral Thesis, Universidad de Cantabria.

Sarro, M. M., Cuesta, P., & Penelas, A. (2007). La responsabilidad social corporativa (RSC): Una orientación emergente en la gestion de las entidades bancarias españolas. In J. C. Ayala (Ed.), Conocimiento, innovación y emprendedores: Camino al futuro. Logroño: Universidad de La Rioja.

Scott, S. G., & Lane, V. R. (2000). A stakeholder approach to organizational identity. The Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 43–62.

Sen, S., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2001). Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2), 225–243.

Sureshchandar, G. S., Rajendran, C., & Anantharaman, R. N. (2002). Determinants of customer-perceived service quality: A confirmatory factor analysis approach. Journal of Services Marketing, 16(1), 9–34.

Szymanski, D. M., & Henard, D. H. (2001). Customer satisfaction: A meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 29(1), 16–35.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations. Monterrey, CA: Brooks-Cole.

Tsal, Y. (1985). On the relationship between cognitive and affective processes: A critique of Zajonc and Markus. Journal of Consumer Research, 12(3), 358–362.

Turban, D. B., & Greening, D. W. (1997). Corporate social performance and organizational attractiveness to prospective employees. Academy of Marketing Journal, 40(3), 658–672.

Vendelo, M. T. (1998). Narrating corporate reputation. International Studies of Management & Organization, 28(3), 120–137.

Watson, D., & Tellegen, A. (1985). Toward a consensual structure of mood. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 219–235.

Westbrook, R. A. (1987). Product/consumption-based affective responses and postpurchase processes. Journal of Marketing Research, 24(3), 258–270.

Westbrook, R. A., & Oliver, R. L. (1991). The dimensionality of consumption emotion patterns and consumer satisfaction. Journal of Consumer Research, 18(1), 84–91.

Wirtz, J., & Bateson, J. E. G. (1999). Consumer satisfaction with services: Integrating the environment perspective in services marketing into the traditional disconfirmation paradigm. Journal of Business Research, 44(1), 55–66.

Wirtz, J., Mattila, A. S., & Tan, R. L. P. (2000). The moderating role of target-arousal on the impact of affect on satisfaction—An examination in the context of service enterprises. Journal of Retailing, 76(3), 347–365.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pérez, A., Rodríguez del Bosque, I. An Integrative Framework to Understand How CSR Affects Customer Loyalty through Identification, Emotions and Satisfaction. J Bus Ethics 129, 571–584 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2177-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2177-9