Abstract

Based on case studies and qualitative interviews conducted with 40 stakeholders in five SMEs, or so called Anatolian tigers, in Turkey, this article has explored what collective spirituality and Turkish Islamic business ethics entail and how they shape organizational values using diverse stakeholder perspectives. The study has revealed six emergent discourses around collective spirituality and Islamic business ethics: Flying with both wings; striving to transcend egos; being devoted to each other; treating people as whole persons; upholding an ethics of compassion; and leaving a legacy for future generations. These discourses are organized around three themes of collective spirituality, respectively: Transcendence, connectedness, and virtuousness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There is not just one correct way of implementing business ethics according to Islam. Islam today has many different interpretations and adaptations based on cultural context. Yavuz (2004) argues that there are seven diverse ethno-cultural zones of Islam (Arab, Persian, South Asian, Malay–Indonesian, African, Diaspora, Turkish) each of which interprets Islam based on its own national culture, socio-political environment, historical legacy, and economic conditions. According to Yavuz (2004), there is a constant fertilization and flow of ideas, practices, discourses, and skills across these zones, as well as between these zones and the Western contexts and cultures. This paper responds to the call for understanding Islamic business ethics in diverse cultural and geo-political contexts. In particular, it focuses on the interpretation of Islam in Turkey, and analyzes the discourses of collective spirituality and Islamic ethics in the Anatolian Muslim context. This paper attempts to demonstrate how ethical principles that govern daily organizational life and business practices of Anatolian tigers in Turkey are colored and shaped by values and narratives of Turkish Islam.

Turkey is a unique secular and democratic country whose population is Muslim. Turkey is a country where elements from Islam and elements from Western culture—extracted over the centuries from Europeans, Persians, Arabs, Byzantines and Russians—live hand in hand. Anatolia has been homeland to 26 different civilizations and it is a center of exchange and dialog among different civilizations, nations, faiths, and cultures. We suggest that Turkish interpretations of Islamic ethics in organizations can enrich the discussions of Islamic business ethics in relation to globalization and development. The newly emerging small and medium scale enterprises (SMEs), so-called “Anatolian tigers” in Turkey provide a distinct understanding of Islamic ethics, collective spirituality, and prosperity. The founders and entrepreneurs in Anatolian tigers see Islam as the religion of trade and business, as they see no contradiction between profit and morality. Through forming discourses of collective spirituality and Islamic ethics, they bridge the gap between the Islamic world and the West and in doing so, challenge some of the myths and misconceptions about Islamic business and ways of doing business in Muslim countries.

A Contextual Perspective on the Rise of Anatolian Tigers

The newly rising Islamic bourgeoisie has recently become more visible and powerful in their lifestyles and demand for social change in Turkey. With the rising power of conservative media channels and newspapers (e.g., STV, Zaman), Islamic banks (e.g., Bank Asya, Albaraka Türk, Kuveyt Türk), holdings (e.g., Ülker, Boydak, BİM, İhlas), NGOs (e.g., Deniz Feneri, Kimse Yok Mu?), and trade associations (e.g., TUSKON, İŞHAD), Turkish religious conservative class is in demand of more rights, democracy, freedom, education, progress, technology, modernization, and globalization. One of the important markers of these demands is the search for more modern, Westernized, and luxurious forms of consumption (Sehlikoglu 2013). The emergent forms of Islamic consumerism are manifested in a dynamic synthesis bridging local Islamic values and global capitalist values. Colorful examples are visible in the new forms and trends of Islamic lifestyles that have rapidly emerged in Turkey; including conservative fashion magazines (Ala), Muslim haute couture (Armine, Akel), veiled fashion shows (Tekbir), “tesettür hotels” (Şah Inn, Caprice), “haşema” (Islamic swimwear), and Islamic luxury yacht tours (Henderson 2010; Sehlikoglu 2013). In this context of dynamic social change, Turkish Muslim bourgeoisie is gaining significance and power in the international realm not only in terms of their numbers and demands as customers with purchasing power, but also in terms of their synthesis of Islamic and modern lifestyles (Al-Mutawa 2013; Jafari and Süerdem 2012; Lewis 2010). In particular, we have been witnessing how modernity-enhancing pursuits such as luxurious consumption, arts, haute cuisine, and sports have become popular activities among the younger generation of Islamic family businesses or Anatolian tigers (Sandikci and Ger 2007; Gökariksel and McLarney 2010).

The basis of these social changes is the dramatic increase in the economic power of Anatolian tigers which have also been referred to as “Islamic capital” or “green capital” (Demir et al. 2004; Hoşgör 2011). With liberalization and internationalization of the Turkish economy during the Özal period in 1980s, Anatolian tigers emerged as a group of successful SMEs especially in Anatolian cities where majority of the population lives in accordance with Islamic traditions (Özcan and Çokgezen 2003). Anatolian tigers have rapidly improved their business practices, learned modern technology, used advanced production methods, created impressive organizational structures, and exported to international markets (Turgut 2007; Özcan 2005). Achieving remarkable economic success and development, most of these SMEs have demonstrated that Islam and the spirit of business are not contradictory. The economic success of Anatolian tigers has created a social milieu in Anatolia where modernity and Islam coexist comfortably (ESI 2005). With the rise of Islamic capital in Anatolia, the Anatolian tigers have started to operate on the basis of free-market ideology (Keyman and Koyuncu 2006; Demir et al. 2004); creating their own economic models; and establishing voluntary business associations such as MÜSİAD (Independent Businessman and Industrialists Association), TUSKON (Turkish Confederation of Businessmen and Industrialists), and İŞHAD (Business Life Cooperation Association). These associations enthusiastically promote the links between Islam and free-market capitalism. Social factors such as friendship, social networks, and honor are the main driving forces of maintaining and improving small businesses in Anatolia. In this regard, these associations have provided platforms in which social and economic networks are formed and maintained (Cokgezen 2000). They have also incorporated Weberian principles of rational, technical knowledge, and expertise into doing business; demonstrating a viable link between Islamic business ethics and western capitalism (Keyman and Koyuncu 2006). These associations have also played an important role in the construction of strong societal demands for the formation of a democratic Turkey; pressuring state institutions to transform themselves into being effective, accountable, and transparent (Keyman and Koyuncu 2006). Their visions and strategies have created alternative models of Turkish Islamic modernity where Islam is not anti-modern, nor a critique of capital; instead, it is positioned as a guiding framework for morally and culturally loaded modernization (Keyman and Koyuncu 2006; Uygur 2009). Accepting Islam as a pathway that both complements and balances modernity, Anatolian tigers have produced harmonious co-existence between Islamic identity and free-market ideology.

Managers and entrepreneurs operating in Anatolian tigers seem to be easily navigating across the worlds of global commerce and Islamic business ethics. How do they bridge local and global values in their everyday practices and business strategies? This paper aims to uncover the collective spirituality principles and ethical discourses that make such navigation and synthesis possible.

Collective Spirituality and Business Ethics

More than 70 definitions of spirituality have been introduced since 1990s and most describe it as an individual level phenomenon; focusing on the inner life, idiosyncratic experiences, and feelings of the individual, but neglect its interpersonal and relational aspects. A notable exception is by Mitroff and Denton (1999) who defined spirituality as the basic feeling of being connected with self, others, and the universe. Similarly, Liu and Robertson (2011) conceptualized spirituality by three distinct dimensions: interconnection with human beings, interconnection with nature and all living things, and interconnection with a higher power. Milliman et al. (2003) have proposed three dimensions of linkages between workplace spirituality and employee work attitudes and behaviors; (a) individual level, sense of purpose and meaning in work, (b) group level, including having a sense of community and belonging, (c) organization level, referring to the fit and alignment between individual organizational values and mission. Past research, however, does not go far in illuminating collective spiritual values and the possible interpersonal and systemic properties of spirituality in organizations. Given that spirituality at work is also about thriving in and belonging to a community, the interpersonal and collective dimensions of spirituality at work are very critical; unfortunately not well addressed in spirituality literature. Accordingly, there is a need for a deeper understanding of collective spirituality at work. Moreover, most past research has been conducted in the context of western countries. All in all, very little empirical research has studied the collective nature of spirituality and how it shapes Islamic business ethics principles and discourses. This paper is a step toward filling that void.

This research defines spirituality as the journey to find a holistic and profound understanding of the existential self and its relationship with the universe or with the transcendent. This definition emphasizes three themes which are directly gleaned from the data: (a) transcendence, (b) connectedness, and (c) virtuousness. Transcendence denotes rising above ego traps or short-term interests in the pursuit of greater good and collective well-being in the long run. Connectedness encompasses an organizational climate characterized by trust, friendship, genuineness, belonging, and interpersonal sensitivity. Virtuousness represents upholding and practicing ethical values and leaving a good legacy for the future.

The objectives of this study are to investigate discourses of collective spirituality and Islamic ethics in Anatolian tigers and to contribute to cross-knowledge transfer between Eastern and Western countries through advancing a new conceptual frame of business bridging local Islamic ethics and global capitalism.

Methodology

This research is based on a case study of five Anatolian tigers in Turkey and utilizes a triangulation of several qualitative research methods: Open ended interviews, participant observation, and documental analysis. Issues probed in each organization are listed in the Appendix 1. Theoretical sampling was used to select these SMEs across a variety of sectors. All these SMEs are known (and reported in media) to be implementing or incorporating or accommodating spirituality successfully and innovatively in their work contexts. We have sought diversity in terms of organizational size, age, and sectors. We also sought for variance in organizational contexts and spirituality practices, while still being able to locate common patterns across a variety of organizational settings (Miles and Huberman 1994).

Two of the SMEs are members of MÜSİAD and they are moderately religious (the founders have religious identities and motives); however, all these SMEs claim to be open to religious diversity and tolerant of individual differences at work. The other three SMEs are members of TUSKON and İŞHAD, and they share affinity and ties with the “hizmet” (service) movement or “Gulen Movement”; the most influential Islamic identity community in Turkey founded by the Muslim thinker Fethullah Gulen (Bilici 2006; Gulay 2007; Yavuz 2013). Gulen Movement advances a modern and moderate interpretation of Islam through science, education, interfaith dialog, and commerce (Pandya and Gallagher 2012; Yavuz 2013). Many Turkish SMEs or Anatolian tigers that export and operate globally provide financial support for this movement; particularly, for its educational activities across 700 schools worldwide (Hendrick 2012). Three of the SMEs in our sample provide financial support for schools in Africa and in Central Asia. These SMEs portray secular images but they accommodate or incorporate spiritual values in their organizational contexts.

These five organizations are among the best performing and admired in Turkey. They are known for the quality of life, positive climate, and social, spiritual, and emotional support they provide to their employees. They are also admired because of their ethical and responsible business practices (indexed in the list of most admired Turkish organizations). It is important to note that the sample, although diverse, may not be representative of all organizations in Turkey which implement spirituality at work. The sample has a positive bias in specifying “positive outliers” that are known for improving the quality of life for their stakeholders with a focus on ensuring their spiritual well-being. It is hoped that these organizations will provide a good initial basis for inquiring innovative forms of spirituality practices in organizations.

Data Collection

First, participatory observation was used for an in-depth understanding of the organizational climate. Researchers partook in naturalistic inquiry to study real-world situations in each organization as they naturally unfold; non-manipulative; and no controlling. By immersion in the research setting, researchers tried to understand the spiritual and ethical perspectives of participants and of the organizational context which shapes and flourishes these perspectives. Second, a variety of documents, primary and secondary sources, were gathered in each organization for documental analysis, including vision and mission statements, strategic reports, HR policies, web site information, meeting agendas, and billboards. Third, open-ended interviews were conducted with employees and managers. In each organization, eight interviews were conducted to get a range of perspectives on spirituality: (a) CEO or founder, (b) a top manager or a high-level executive; (c) one manager (or a middle-level manager), (d) HR director, (e) two employees (e.g., a service representative, administrative assistant, or blue-collar worker), (f) two external stakeholders (e.g., customer, partner, or consultant). Participants were recruited using personal contacts as this has been the most effective and proven method in Turkey to build trust. The resulting sample included 40 stakeholders in five organizations in Turkey. Interviews, lasting about 45–60 min each, were conducted face-to-face, in Turkish, using the protocols shown in the Appendix 2.

Data Analysis

First, thematic analysis (Miles and Huberman 1994) was used to examine interview data. Transcribed interviews were read and first level codes were assigned by two researchers independently to represent participants’ descriptions of their perceptions. These first level codes were then grouped into themes (i.e., discourses). Then the data were reviewed for content fit with the identified themes. The discourses were reworked until all three researchers reached agreement and all coded data fit into the identified themes.

Then all the qualitative materials and data were reviewed using constant comparison method (Glaser and Strauss 1967), producing the following blocks: (1) Memos that capture similarities and differences in people’s perspectives and views of Islamic ethics and collective spirituality; (2) A catalog of the kinds of organizational values, norms, and approaches regarding collective spirituality and Islamic business ethics; (3) A set of memos that capture the richness, texture, and interaction of (a) views on collective spirituality, (b) views on Islamic business ethics, (c) how individuals synthesize local Islamic principles with global oriented business practices.

Grounded theory approach (Glaser and Strauss 1967) was used on material related to themes and views on collective spirituality, shared values, and Islamic business ethics. The authors went over the interview transcripts to extract data on how managers and employees think about their organizations, dominant organizational values, organizational culture, and what their personal conceptions of collective spirituality are. Then they looked for patterns across different discourses of collective spirituality and related organizational dynamics.

The grounded research approach guided the data collection and analysis in this study, that is, the concepts and framework presented below did emerge from the data itself, rather than being derived from prior theory. Nonetheless, the three themes uncovered from the data bear resemblance to three concepts in organizational research; transcendence (Abdallah et al. 2011; Bateman and Porath 2003; Collins 2010; Long and Mills 2010); connectedness (Izak 2012; Pavlovich and Corner 2009) and high-quality connections (Dutton 2003; Dutton and Heaphy 2003); and virtuousness (Comer 2008; Park and Peterson 2003; Provis 2010).

Findings

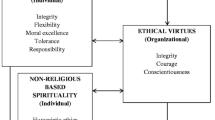

We found six overarching discourses that represent implicit notions the stakeholders seem to hold about collective spirituality and how it is nurtured, coordinated, and developed in their organization. Collective spirituality seems to be intrinsically related to transcending dilemmas and ego traps to achieve full balance and reflexivity (transcendence). In addition, it reflects a shared sense of interconnectedness and a collective search for high-quality connections and rapport (connectedness). Furthermore, collective spirituality is linked with acting virtuously and compassionately at work as well as leaving a positive legacy (virtuousness). These three overarching themes arising from six discourses embody the collective spirituality in organizations and capture the most critical interpersonal principles of Islamic business ethics that Anatolian tigers adopt. They also represent the central characteristics of a transcendent, connected, and virtuous organization that strive to improve the spiritual well-being of its stakeholders (see Figs. 1, 2).

Transcendence

Transcendence represents rising above ego traps or short-term interests in the pursuit of greater good and collective well-being in the long run. Respondents consistently mentioned an organizational culture where self-questioning, balance, wisdom, and reflection are valued and cherished. The underlying spiritual principles of transcendence are simple: First, everyone in the organization strives to balance the mind and the heart. Second, everyone in the organization strives to transcend their egos. These make up the first and the second discourses regarding collective spirituality and Islamic business ethics in the context of Anatolian tigers, as described below:

Discourse 1: We Aim to Fly with Both Wings

The first emergent discourse, shared by 25 respondents, was about building and sustaining the delicate balance between this world and the other world, the mind and the heart, the science and the religion, and so on:

In this organization, we try to build a balance between our hearts and our minds, as well as this world and the hereafter. As the Prophet, peace be upon him, has said, “Live for your afterlife as if you were to die tomorrow, and live for this life as if you were to live forever…” We try to act as mentors to each other as all of us are prone to mistakes. We also try to keep an open mind and heart to benefit from the feedback and suggestions of our friends. As a result, we share a collective wisdom.

Participants believed that they are accountable to God, and their success in the hereafter depends on their performance in this life on earth, adding a new dimension to the valuation of things and deeds in this life. Belief in the hereafter shaped all their actions and perspective in life. However, they also embraced worldly dynamism, pragmatism, and prosperity. Essentially, they aimed to follow moderation -“Sirat al-Mustaqim” (the right path, balanced/middle way). According to this perspective, a balance in human endeavors is necessary to ensure social well-being and continued development of human potential. Therefore, participants interpreted Islam as “the middle way” of balance—between materialism and spiritualism, between rationalism and mysticism, between worldliness and asceticism, between this world and the next. They blended Islam-based spiritual values with the fruits of modernity (through global capitalism) while insisting upon a balance in their words and deeds:

When you combine positive sciences and technology with spiritual values and ethics, you will be able to design more integral and balanced solutions for organizational problems. You have to fly with both wings. Managers who blindly focus on short term profits or results are like birds trying to fly with their one wing – they will miss the big picture and eventually fail.

One manager summarized this philosophy in these words: “Being prepared both for this world and the next” (“hem dünyalık, hem ahiretlik”). However, many participants complained how difficult it was to preserve that balance. Some managers narrated how conservative business people have forgotten about their religious ideals of frugality and modesty as they began indulging in worldly desires, luxury, and money. One entrepreneur stated that “former mullahs have now literally become contractors” (“eski mücahitler müteaahit oldu”). Another respondent lamented how they missed the days when the organization had just been established and they had had to endure poverty and hardships, but nevertheless they “were feeling happier and more peaceful.” He was shedding tears during the interview when he referred to “the good old times” (“hey gidi günler”) as he cited words from the 1991 sermon of Fethullah Gülen at Hisar Mosque (Gulen 1991; referenced with the link of the video as shared by this respondent). In line with the symbolism of this elegy, the struggle for spiritual transcendence was a recurrent theme, which brings us to the second discourse.

Discourse 2: We Strive to Transcend Our Egos

The second discourse was about the shared value of transcending the egos and relentlessly questioning the self. 21 participants mentioned that they were exercising self-restraint and self-discipline by constantly being alert for the “ego traps,” including “complacency,” “selfishness,” “arrogance,” “false pride,” and “egoism.” A striking observation was that the aggregation and sharing of these individual values translated into a collective sense of reflexivity and wisdom:

Our golden principle: Be a judge to yourself and be an advocate for people around you. This may sound like a simple principle; but it is hard to implement it in the hot pace of business. It takes enormous discipline and courage to resist your ego traps…

This discourse summarized the Sufi principle of encountering, discovering, and disciplining the self (“nefs”) within the self through control of lower desires and passions. Some participants described this as the bigger struggle (“jihad al-akbar”); whereas others talked about reaching toward becoming “zero” (see Karakas 2008 for zero-centered spirituality). The shared principle aimed at fostering a spirit of service (“hizmet”) and sacrifice (“diğergamlık”) across the organization:

When everyone moves away from being self-centered to becoming more people-centered or community-centered, the workplace transcends to a cozy site of support and friendships. People here do not expect any returns or gifts in response to their own efforts and service, because being part of this community is a gift in itself.

Considering tremendous accomplishments the Anatolian tigers have enjoyed on international scale, managers and entrepreneurs emphasized the need to forget about triumphs in order to retain modesty and keep trying hard:

If I would describe the organizational culture of this company, I would say it is a culture of benevolence and transcendence. Everyone must constantly strive and search for the best of their own—more tolerant, considerate, sincere, and compassionate… The moment you stop learning and abandon humility, you are dead.

Transcendence seems to be inherently related to the urge to develop a culture of belonging and compassion, which brings us to the dynamic of connectedness.

Connectedness

Connectedness represents collective thriving and flourishing through high-quality interpersonal relationships and encompasses an organizational climate characterized by trust, friendship, genuineness, belonging, and interpersonal sensitivity. Respondents talked about exchanging genuine conversations, having fond memories, celebrating birthdays, sharing laughter, and enjoying the company of one another in a friendly atmosphere. The basis of connectedness is two interrelated discourses on collective spirituality: First, everyone in the organization feels connected and devoted to each other. Second, everyone in the organization treats each other as a whole person with a mind, heart, and soul.

Discourse 3: We are Devoted to Each Other

The third discourse embodies the sense of dedication that organizational members feel toward one another and toward the organization. 26 respondents stressed the significance of high-quality relationships among people in the organization. These relationships go far beyond the formal roles and titles in the organization; and they seem to be driven by mutual affection and connections that are deeply spiritual. One participant mentioned “spiritual networks of prayer” where friends pray for each other mentioning their names and good wishes for them. There is a spiritual ecosystem in the organization that gives room to deep and sincere relationships among people:

What characterizes organizational culture here is that employees have a special bonding with one another at work. Employees feel responsibility and show genuine concern for customers. Our customers are impressed by our sense of empathy and problem solving. This sense of dedication sets us apart from the competition.

We have observed that managers in Anatolian tigers deeply valued their workers and employees; treating them as family members. Some respondents described this principle as being brothers and sisters (“uhuvvet”) or showing compassion for everyone at work (“şefkat”):

We are a closely knit community. We care about people and relationships in this organization. We have learned about, sincerity, friendship, love and generosity here.

It can be said that Anatolian tigers have adopted a soft and inclusive interpretation of Islam; thereby created a sense of community and inspired a sense of belonging in employees. This is very much in line with the Turkish Sufi understanding of Islam which has largely been shaped by the compassion of Rumi, the grace of Ahi Evran, the love of Yunus Emre, the wisdom of Ahmet Yesevi, and the moderation of Hacı Bektaş Veli; who were leading Sufi Muslim dervishes embodying universal humanistic values of Anatolia for centuries. Some respondents mentioned these names as role models who have inspired them. We have observed that leaders of Anatolian tigers acted consistently with values of love, hope, kindness, and nurturing. This has helped to break down the walls of hierarchy and has created a love-based culture instead of a fear-based one:

I would say the quality of conversations make this workplace admirable. You can engage in conversations with your co-workers that are meaningful, courageous, and inspiring. You can share a laugh or exchange candid opinions with your managers without feeling embarrassed or overwhelmed.

Anatolian tigers have been able to forge dense networks of friendship and sincerity that make flow of business ideas and ethical practices possible; linking local Islamic values and global capitalism. These structures have been built on the legacy of the “Ahi” system, which was the 13th century Anatolian artisan guild institution designed on the principles of equitable distribution of income, solidarity among people, progress through artisanship and trade, generosity toward community, professional ethics, and peaceful way of life (Uyar 2012). The Ahi system reminds the concept of industrial districts or clusters in which cultural values, local communities, business systems, and social institutions reinforce each other, create social capital, and trigger virtuous economic circles. The basis of these systems underlies the value placed on the communities and the people living in those communities, which brings us to the next discourse.

Discourse 4: We do not View Humans as Resources; we Touch their Hearts and Lives

The fourth discourse underlines the importance of reaching out to every person and treating everyone as a respected individual. This involves regarding employees as whole persons and allowing room for their spirituality and creativity. Three of the organizations have been explicitly rejecting the term “human resources” and use terms “talent,” “people,” “community,” or “human potential”. One manager stated “A core value in this organization is treating employees, volunteers, partners, and clients as whole persons—with hearts, minds, and souls.” Another respondent narrated how they avoided contractual relationships and tried to build lifetime relationships with employees:

We think every interaction is an opportunity to empathize with and help the other person. As a manager, my duty is to make sure I can serve people here and contribute to their lives. One day, if they think ‘Mehmet made a difference in my life’, or ‘I learned something from him’ then I have fulfilled my mission.

This discourse created an organizational vision based on the primacy of well-being of people over organizational efficiency. We observed that managers truly listened to their team members during meetings and built a safe place where everyone could express their ideas without fear. Dominant leadership style was horizontal servant leadership, which emphasized empowering, delegation, and cooperation. Although this seemed to result in high morale, job satisfaction and loyalty, at times it also seemed to hamper efficiency by making the workplace vulnerable to slacking and shirking.

Virtuousness

Virtuousness represents upholding and practicing ethical values and leaving a good legacy for the future. Virtues are concerned with answering the question of how to live a good life and how to be a good person. Respondents mentioned the significant role of virtues in creating compassionate and humane work environments. Virtues also provide organizational members with an opportunity to ask themselves how their decisions impact the lives of other people and how they can leave a positive legacy. Virtuousness is infused into the fabric of social life in the organization through a pattern of values and routines that increase benevolent tendencies of organizational actors. It can be stated that the social architecture of the organization creates the context for virtuous acts by affirming and enabling them; easing their occurrence. Virtuousness is supported by the following discourses: First, everyone in the organization lives and behaves according the golden rule. Second, everyone in the organization strives to leave a virtuous legacy for future generations.

Discourse 5: We Uphold an Ethics of Compassion and we Obey the Golden Rule

The fifth discourse denotes the core virtuous principle of treating others as you want to be treated. 30 participants have mentioned going the extra mile for co-workers, treating people with kindness and compassion, placing the self in the shoes of another person, and applying the golden rule in all of interactions with organizational stakeholders. These principles have been stressed in all of the five organizations and they seem to be a significant part of the organizational culture:

We need compassion as much as water and air. We try to foster high quality relationships and bonds of compassion among us. We do this through positive actions and interactions in the social fabric of this organization.

The Golden Rule is simple but very precious. Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. This sums up our code of conduct here.

Some participant managers emphasized how Sufi teachings led them to justice, kindness, and charity to their employees. They could establish the sacredness of everyday business life through demonstrating an ethics of compassion—even in the face of challenges. Some other managers commented on how the teachings of Prophets Mohammed, Moses, and Jesus have enabled them to leave their egocentrism and to become humble and gentle toward others. Some managers mentioned humility, integrity, service, and modesty as essential components of good leadership. It was observed that managers at Anatolian tigers were more concerned about serving people’s needs than exercising privilege, power, and control. Another respondent confirmed the significance of this discourse as follows:

It is a pity that Islam is reduced to some rituals and rules and it is divorced from the ethical aspects of our lives. If you violate the rightful due (kul hakkı) of another person, you have to ask blessing from that person. If you break the heart of a person, or if you lie to sell your product, no matter how you pray five times a day or go to Hajj, Allah will not be pleased with you. Period.

Discourse 6: We Leave a Virtuous Legacy for Future Generations

The last discourse is about making a positive impact in the world and leaving a good legacy for future generations. 18 participants have discussed impact and legacy as a spiritual value shared across the organization. Often, participants have talked about legacy with a sense of idealism conveyed through powerful stories and metaphors. Implicit in this discourse is a call for integrative and long-term thinking:

We have suffered too long from myopic visions in this organization and felt the need for a holistic change. We have changed our performance measures and incorporated a set of new measures in order to balance profits with a long term vision. These measures include social responsibility, community impact, contribution to well-being, and designing integral solutions.

This workplace is characterized by a shared passion to make a positive difference. Even if we are in hard times, we invest for a better future for our community. We feel almost as if we are building a future civilization with passion, inspiration, hope and faith. In a way, we want to be pieces of soil for roses to flourish.

One of the founders commented that the best way to pray is to establish a successful business, open a factory, and provide jobs for people. Another manager brought up how Islam stressed the virtues of hard work, self-sufficiency, entrepreneurship, charity, and community service, and the Prophet himself was a trader; quoting a hadith saying nine-tenths of one’s earnings and fate is in commerce. Leaders of Anatolian tigers repeatedly mentioned how they believed in the power of investing in the education of the next generation and leaving a virtuous legacy built on honest work, charity, and generosity. Strikingly, the success and legacy of Anatolian tigers are explained through theories of Protestant work ethics and Calvinism in the extant literature (Bilefsky 2006; ESI 2005; Hoşgör 2011; Judson 2005; Kosebalan 2007).

Discussion

Based on case studies and qualitative interviews conducted with 40 stakeholders in five SMEs in Turkey, this article explored what collective spirituality and Islamic business ethics entails in cultural context of Turkey. The study revealed three themes, transcendence, connectedness, and virtuousness in organizations through six discourses around collective spirituality and Islamic business ethics: Flying with both wings, striving to transcend egos, being devoted to each other, treating people as whole persons and touching their hearts and lives, upholding an ethics of compassion and obeying the golden rule, and leaving a legacy for future generations. When taken together, these discourses illustrated the collective sensemaking and social construction of how transcendence, connectedness, and virtuousness were nurtured across the organization.

The uncovered spiritual and ethical discourses reflect the Turkish cultural context and Anatolian spiritual traditions. The fact that collective spirituality has been perceived positively by participants can be analyzed in the light of Anatolian Sufism. Sufism is a lifelong Islamic discipline which builds up the character and inner life of a person by purifying the heart spiritually and investing it with virtues. It is also known as the mystical philosophy of Islam that focuses on diminishing the ego through multiple ways including regulating physical needs. The ultimate aim is to reach the pure love of God that is believed to be the ultimate satisfaction. Although Turkey is a secular country, Sufism has infused organizational climates and personal lives for centuries and most people feel comfortable with the idea of spiritual wisdom offering guidance to people and organizations. The guidance of Anatolian dervishes (Sufis) and Muslim saints (such as Rumi) has shaped and influenced the Anatolian intellectual and spiritual milieu (i.e., the spiritual context of Turkey) for more than seven centuries. This spiritual guidance stresses care and compassion as organizing principles of collective life; and the results can be interpreted as a reflection of the Sufi approach to organizational life. However, given that organizational research has found more similarities than differences regarding spiritual values in Protestant British, Catholic Irish, and Muslim Turkish contexts (Arslan 2001), these findings may prove very useful in exploring discourses of spirituality in other cultural or religious contexts as well. Therefore, despite the obvious limitations of generalizability inherent in qualitative research, the findings of this study can be at least partially useful or applicable in other cultural and spiritual contexts. This study has focused on the human aspects of the organizational experience that is shared across different religious contexts; yet grounded in the local values of Anatolian tigers and Turkish Islamic ethical principles.

There is no universal model of Islamic ethics or a single best way to incorporate spirituality into work; since there are multiple ways of interpreting Islamic perspectives on business, economics, gender, justice, and development. Yavuz (2004) argues that globalization has created two competing visions of Islam, one “ghetto Islam” characterized by deprivation and radicalism, and one “liberal and market-friendly Islam” characterized by neo-liberal and democratic aspirations. Given the scale and success of Anatolian tigers in using the market system and harmonizing modern management practices with spiritual organizational values, the Turkish interpretations of Islam clearly fall into the latter category. It is important to note that three of the SMEs in our sample also benefited significantly from the global network, opportunities, and resources of the Gulen movement, which is well-known for its expertise in the utilization of international market forces and networks.

Limitations and Challenges

This research has limitations. Firstly, the sample is not representative of all organizations in Turkey which implement spirituality at work. The sample has a positive bias in specifying “positive outliers” that are known for improving the quality of life for their stakeholders with a focus on ensuring their spiritual well-being. It is hoped that these organizations will provide a good initial basis for inquiring innovative forms of spirituality practices in organizations. Secondly, the findings of this research are exploratory and subject to inherent challenges of qualitative research in terms of generalizable results, validity, and wider implications. Finally, we have not addressed the challenges of incorporating spirituality in organizations. There may be legitimate resistance (academic as well as practical) to the concept of collective spirituality in some organizations, which is well addressed in the literature.

Implications for Practice

The overarching implication suggested by findings is that the real power of discourses around collective spirituality lies in their capacity to unleash the transcendent, the connected, and the virtuous self in each organizational member. The study suggests that organizations and leaders may drive positive change in human systems if they respect and nourish the inner lives of employees and enable them to express their best selves as whole persons. A significant implication for managers is the value of using spirituality discourses to initiate and foster positive change across the human system. These spirituality discourses involve all organizational actors and allow them to be agents of self-expression, passion, and compassion. They capture the attention and imagination of employees who have big dreams and ideals. If managers can tap into these dreams and ideals, everyone will benefit from expressing, nurturing, and realizing these dreams. The role of managers is to observe, mentor, fascinate, inspire, engage, and facilitate employees toward positive change.

Another contribution of this paper has been in introducing three organizational pathways or dynamics toward positive change:

Through transcendence, organizations can reach greater balance in the midst of seemingly clashing goals to advance positive organizational change. This study has described how rising above ego traps or short-term interests in the pursuit of greater good contributes to positive change. As an organization moves along transcendence, signs of wisdom and generativity are observed in the words spoken and in the behaviors exhibited.

Through connectedness, organizations can build a positive climate characterized by trust, vitality, and rapport. Such a climate will then enable members to unleash their positive energy and strive toward their goals. As an organization becomes more connected; signs of caring, passion, and compassion become visible in the fabric of everyday life. There is a sense of mutual caring and an overall pattern of resilience, vibrancy, and engagement. As interpersonal sensitivity is woven into the daily rituals and interactions, organizational members feel more supported in their change initiatives and actions.

Through virtuousness, organizations can embody whole-system values which enable the human spirit to grow and flourish; such as truth, justice, courage, humility, or forgiveness. Virtues can facilitate emergent processes that are life generating and nourishing for organizational members; thereby lead to positive change across the system. As an organization moves along virtuousness; acts of benevolence shape everyday behaviors of organizational members and virtues become the signature quality of the organization.

Conclusion

This study has responded to the call of Metcalfe and Syed (2014) to challenge assumptions of a homogeneous Islamic philosophy and/or a universal ethos of Islamic ethics imagined to be incompatible with Western values and ethics. We have suggested that Anatolian tigers have formulated collective ethical and spiritual discourses grounded in Turkish Islam that is quite compatible with global capitalism, neo-liberalism, international trade, and Protestant work ethics. Operating in the asset-rich and well-integrated Turkish economy, Anatolian tigers have developed business ethics principles aimed at fostering economic growth, productive investment, risk-taking, learning, and entrepreneurship. The discourses uncovered in this study successfully bridge the resurgence of Islamic identities and neoliberal capitalism in Turkey. These findings suggest that Islamic business ethics should not be interpreted as a coherent universal entity, but as a diverse set of culturally embedded, socially constructed, and locally produced values and discourses that bring together realms that are usually set apart, such as “modern” vs. “traditional,” “secular” vs. “religious,“ “individualist” vs. “collectivist,” or “developed world” vs. “developing world.” In that sense, discourses of Islamic business ethics can be regarded as diverse and dynamic as the socio-cultural or geo-political contexts they are shaped by. This paper calls for a critical and contextual perspective to understand the emergence of new forms of collective organizing that bridge neoliberal capitalism, spiritual principles, and Islamic lifestyles. In particular, the paper underlines distinctive features of discursive practices that Turkish SMEs or Anatolian tigers employ when they moderate and balance belief in the hereafter and spiritual values on the one hand, and worldly dynamism, pragmatism, and prosperity on the other hand. Given that globalization has put issues of human rights, ethics, justice, identity, and democracy in the spotlight, the collective spirituality discourses used by Anatolian tigers can contribute to the global debates on Islamic stances and perspectives on employment relations (Syed and Ali 2010), stakeholder issues (Beekun and Badawi 2005), corporate social responsibility (Williams and Zinkin 2010), and labor rights (Duran and Yildirim 2005). In that sense, Anatolian tigers have already created powerful resources and discourses to blend economic, social, and spiritual progress; assisting cross-knowledge transfer between Eastern and Western countries on designing organizational climates of care, compassion, and spirituality. By highlighting the importance of the spiritual dimension at work woven into the day-to-day beliefs and practices of managers in Anatolian tigers, we account for the construction of Turkish interpretations of Islamic business ethics. In doing so, we emphasize a future agenda of further research that is sensitive to the complexities of diverse and fluid understandings of Islamic business ethics in diverse geo-political or socio-cultural contexts.

References

Abdallah, C., Denis, J., & Langley, A. (2011). Having your cake and eating it too: Discourses of transcendence and their role in organizational change dynamics. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 24(3), 333–348.

Al-Mutawa, F. S. (2013). Consumer-generated representations: Muslim women recreating western luxury fashion brand meaning through consumption. Psychology & Marketing, 30(3), 236–246.

Arslan, M. (2001). The work ethic values of protestant British, Catholic Irish and muslim Turkish managers. Journal of Business Ethics, 31, 321–339.

Bateman, C. L., & Porath, T. (2003). Transcendent behaviors at work. In K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Beekun, R., & Badawi, J. (2005). Balancing ethical responsibility among multiple organization stakeholders: The Islamic perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 60, 131–145.

Bilefsky, D., (2006, August 27). Turks knock on Europe’s door with evidence that Islam and capitalism can coexist. New York Times.

Bilici, M. (2006). The Fethullah Gülen movement and its politics of representation in Turkey. The Muslim World, 96(1), 1–20.

Cokgezen, M. (2000). New fragmentation and new cooperation in the Turkish bourgeoisie. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 18, 525–544.

Collins, D. (2010). Designing ethical organizations for spiritual growth and superior performance: An organization systems approach. Journal of Management, Spirituality, and Religion, 7(2), 95–117.

Comer, P. D. (2008). Workplace spirituality and business ethics: Insights from an Eastern spiritual tradition. Journal of Business Ethics, 85, 377–389.

Demir, O., Acar, M., & Toprak, M. (2004). Anatolian tigers or Islamic capital: Prospects and challenges. Middle Eastern Studies, 40(6), 166–188.

Duran, B., & Yildirim, E. (2005). Islamism, trade unionism and civil society: The case of Hak-Is labour confederation in Turkey. Middle Eastern Studies, 41(2), 227–247.

Dutton, J. E. (2003). Energize your workplace: How to create and sustain high quality connections at work. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Dutton, J. E., & Heaphy, E. D. (2003). The power of high quality connections. In K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline (pp. 263–278). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

ESI. (2005). ‘Islamic calvinists. Change and conservatism in Central Anatolia. Istanbul, Brussels, Berlin: European stability initiative’. http://www.esiweb.org/pdf/esi_document_id_69.pdf.

Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company.

Gökariksel, B., & McLarney, E. (2010). Muslim women, consumer capitalism, and the Islamic culture industry. Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies, 6(3), 1–18.

Gulay, E. N. (2007). The Gülen phenomenon: A neo-sufi challenge to Turkey’s rival elite? Critique: Critical Middle Eastern Studies, 16(1), 37–61.

Gulen, F. (1991). ‘Those were the days (Hey gidi günler)’, Sermon at Hisar Mosque, Izmir. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sMnEa1lQXxE.

Henderson, J. C. (2010). Sharia-compliant hotels. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 10(3), 246–254.

Hendrick, J. (2012). Islam, ambiguity, and social change in Turkey: The organizational practices of the Fethullah Gulen Movement’, in the Second ISA Forum of Sociology, Isaconf, August 1–4, 2012.

Hoşgör, E. (2011). Islamic capital/Anatolian tigers: Past and present. Middle Eastern Studies, 47(2), 343–360.

Izak, M. (2012). Spiritual episteme: Sensemaking in the framework of organizational spirituality. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 25(1), 24–47.

Jafari, A., & Süerdem, A. (2012). An analysis of material consumption culture in the Muslim world. Marketing Theory, 12(1), 61–79.

Judson, D. (2005, September 30). Islamic calvinism’ a paradoxical engine for change in conservative Central Anatolia. Turkish Daily News.

Karakas, F. (2008). Reflections on zero and zero-centered spirituality in organizations. Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal Incorporating Journal of Global Competitiveness, 18(4), 367–377.

Keyman, E. F., & Koyuncu, B. (2006). Globalization, alternative modernities and the political economy of Turkey. Review of International Political Economy, 12(1), 105–128.

Kosebalan, H. (2007). The rise of Anatolian cities and the failure of the modernization paradigm. Middle East Critique, 16(3), 229–240.

Lewis, R. (2010). Marketing Muslim lifestyle: A new media genre. Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies, 6(3), 58–90.

Liu, C. H., & Robertson, P. J. (2011). Spirituality in the workplace: Theory and measurement. Journal of Management Inquiry, 20, 35–50.

Long, B. S., & Mills, J. H. (2010). Workplace spirituality, contested meaning, and the culture of organization: A critical sensemaking account. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 23(3), 325–341.

Metcalfe, B. D., & Syed, J. (2014). Globalization, development and Islamic business ethics: Call for papers for a special issue of Journal of Business Ethics. Journal of Business Ethics.

Miles, M., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Milliman, J., Czaplewski, A. J., & Ferguson, J. (2003). Workplace spirituality and employee work attitudes: An exploratory empirical assessment. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 16(4), 426–447.

Mitroff, I. I., & Denton, E. A. (1999). A spiritual audit of corporate America: A hard look at spirituality, religion, and values in the workplace. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Özcan, Z. (2005). Akla ve paraya ihtiyacı olmayan sehir. Aksiyon, 64–75.

Özcan, G. B., & Çokgezen, M. (2003). Limits to alternative forms of capitalization: The case of anatolian holding companies. World Development, 31(12), 2061–2084.

Pandya, S., & Gallagher, N. (2012). The Gülen Hizmet movement and its transnational activities: Case studies of altruistic activism in contemporary Islam. Boca Raton: Brown Walker Press.

Park, N., & Peterson, C. M. (2003). Virtues and organizations. In K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline (pp. 33–47). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Pavlovich, K., & Corner, P. D. (2009). Spiritual organizations and connectedness: The living nature experience. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 6(3), 209–229.

Provis, C. (2010). Virtuous decision making for business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 91(2), 3–16.

Sandikci, O., & Ger, G. (2007). Constructing and representing the Islamic consumer in Turkey. Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body & Culture, 11(2–3), 189–210.

Sehlikoglu, S. (2013). Modern, feminine and Islamic: Female customers of “veiled” hotels in Turkey’, Working paper.

Syed, J., & Ali, A. (2010). Principles of employment relations in Islam: A normative view. Employee Relations, 32(5), 454–469.

Turgut, P., (2007, April 22). Anatolian tigers. Financial Times.

Uyar, H. (2012). The effects of akhism principles on today’s business life: A case in the Western Mediterranean region. In 3rd International Symposium on Sustainable Development, May 31–June 01 2012, Sarajevo.

Uygur, S. (2009). The Islamic Work Ethic and the Emergence of Turkish SME Owner-Managers, Journal of Business Ethics, 88(1), 211–225.

Williams, G., & Zinkin, J. (2010). Islam and CSR: A study of the compatibility between the tenets of Islam and the UN Global Compact. Journal of Business Ethics, 91(4), 519–533.

Yavuz, M. H. (2004). Is there a Turkish Islam? The emergence of convergence and consensus. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 24(2), 213–232.

Yavuz, M. H. (2013). Toward an Islamic enlightenment: The Gülen Movement. New York: Oxford University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Issues Probed: Themes of Collective Spirituality

-

1.

Analytical Memo on General Organizational Context

-

Organizational mission, vision and objectives, strategic directions

-

Organizational culture, values and how they are related to spirituality

-

Organizational spiritual climate for employees

-

Spirituality and spiritual values of organizational founders/leaders and how these affect the organization

-

2.

Analytical Memo on Collective Spirituality

-

Meanings attached to collective spirituality

-

Discourses on collective spirituality

-

Ways of incorporating spirituality: Innovation and best practices

-

Organizational guidelines/policies/attitudes related to employees’ spiritual needs

-

3.

Narratives Section: Narratives of spirituality

-

Experiences/stories/perceptions of collective spirituality

-

Emotions, symbols, metaphors, and language used to describe collective spirituality

-

Reflective Memo A: A focus on interpersonal aspects of narratives

Characteristics of interpersonal relationships

Sense of belonging? Sense of community? Interconnectedness?

-

Reflective Memo B: A focus on the organizational level

What are characteristics of work contexts where positive relationships and spirituality are nurtured and flourished?

Guiding values

-

Emergent frameworks: Discourses of collective spirituality

Appendix 2

Interview Protocol

Interviewee General Information

-

Age, sex, demographics; job and position

-

Years and experiences in the organization, career trajectory

Individual Perceptions of Spirituality

-

Probe into personal meanings of spirituality, attitudes toward spirituality

Spirituality Narratives

-

Participants asked to provide stories/narratives of a time when they experienced or witnessed spirituality at work. Collective aspects of narratives probed.

Perceptions of Collective Spirituality

-

What gives life to this organization? What gives meaning to work in this organization?

-

Fit between individual and organizational spiritual values

Perceptions of Organizational Values and Ethics

-

What are the overarching values and principles that guide people in this organization?

-

What are the organizing principles for nourishing spiritual well-being?

-

What are shared ethical and spiritual values in this organization?

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Karakas, F., Sarigollu, E. & Kavas, M. Discourses of Collective Spirituality and Turkish Islamic Ethics: An Inquiry into Transcendence, Connectedness, and Virtuousness in Anatolian Tigers. J Bus Ethics 129, 811–822 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2135-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2135-6